As a Matter of Fact:

The National

Charter School

Study III 2023

LAST UPDATED 6/19/2023

As a Matter of Fact:

The National Charter

School Study III 2023

Executive Summary

Authors

Margaret E. Raymond, Ph.D.

James L. Woodworth, Ph.D., Lead Analyst- 31 State Study

Won Fy Lee, Ph.D., Lead Analyst- CMO Study

Sally Bachofer, Ed.M.

Contributors

Meghan E. Cotter Mazzola, M.S.

William D. Snow

Tzvetelina Sabkova, M.A.

Executive Summary Volume 1

Charter School Performance

in 31 States

Volume 2

Charter Management

Organizations 2023

Volume 3

Summary of Findings,

Conclusions and Implications

As a Matter of Fact: The National Charter School Study III 2023 1

© 2023 CREDO

Center for Research on Education Outcomes

Stanford University

Stanford, CA

https://credo.stanford.edu

CREDO, the Center for Research on Education Outcomes at Stanford University, aims to improve empirical

evidence about education reform and student performance at the primary and secondary levels. CREDO

at Stanford University supports education organizations and policy makers in using reliable research and

program evaluation to assess the performance of education initiatives. CREDO’s valuable insight helps

educators and policy makers strengthen their focus on the results of innovative programs, curricula, policies,

and accountability practices.

Acknowledgments

CREDO gratefully acknowledges the support of the state education agencies that contributed their data to

this partnership. Our data access partnerships form the foundation of CREDO’s work, without which studies

like this would be impossible. We strive daily to justify the condence placed in us.

The research presented here uses condential data from state departments of education. The views

expressed herein do not necessarily represent the positions or policies of the organizations noted above.

No ocial endorsement of any product, commodity, service or enterprise mentioned in this publication is

intended or should be inferred. In addition:

> The research presented here utilizes SLDS Data from the Idaho State Board of Education (SBOE) and the

Idaho State Department of Education. Any research errors are the sole responsibility of the author(s).

> This research result used data structured and maintained by the MERI-Michigan Education Data Center

(MEDC). MEDC data is modied for analysis purposes using rules governed by MEDC and is not identical

to data collected and maintained by the Michigan Department of Education (MDE) and/or Michigan’s

Center for Educational Performance and Information (CEPI). Results, information and opinions solely

represent the analysis, information and opinions of the author(s) and are not endorsed by, or reect the

views or positions of, grantors, MDE and CEPI or any employee thereof.

> Data for this report was provided by the Missouri Department of Elementary and Secondary Education.

> The conclusions of this research do not necessarily reect the opinions or ocial position of the Texas

Education Agency, the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board, or the State of Texas.

The analysis and conclusions contained herein are exclusively those of the authors and are not endorsed by

any of CREDO’s supporting organizations, their governing boards, or the state governments, state education

departments or school districts that participated in this study. All errors are attributable to the authors.

CREDO also acknowledges the Walton Family Foundation and The City Fund for supporting this research.

Executive Summary Volume 1

Charter School Performance

in 31 States

Volume 2

Charter Management

Organizations 2023

Volume 3

Summary of Findings,

Conclusions and Implications

As a Matter of Fact: The National Charter School Study III 2023Executive Summary | Last Updated 6/19/2023 32

Project Description

As a Matter of Fact: The National Charter School Study III 2023 (NCSSIII) is the third national study by CREDO

evaluating the academic progress of students enrolled in charter schools in the United States. The current

report presents ndings from 2014 to 2019, which yields four periods of year-to-year student growth as

measured by state achievement tests. It includes data from 29 states plus Washington, D.C., and New

York City, which for convenience we report as 31 states. In addition, because we have used a common

methodology across the three studies, we can combine results into trends to support insights of the

performance of students enrolled in charter schools over the past 15 years.

To organize the extensive body of this current research eort, CREDO separated the analysis into two parts

and produced two reports: (1) Charter School Performance in 31 States (CSP31) and (2) Charter Management

Organization 2023 (CMO23). CSP31 examines the performance of the full set of charter school students

and schools, while CMO23 analyzes the dierence in academic growth between students attending charter

schools associated with charter management organizations (CMOs) and those attending stand-alone

charterschools (SCS).

1

We present this combined Executive Summary for both reports as well as common

Summary of Findings, Conclusions and Implications to ensure we present the fullest picture of performance

in charterschools.

Our work deliberately focuses on a specic outcome: the annual progress that students make over an

academic year. In this report, we look at students in charter schools compared to the experience they

would have had in the traditional public schools (TPS) they would otherwise have attended. One notable

limitation of this approach is that we have limited line of sight “under the hood” and into the role that

localized environmental, regulatory and organizational factors play on individual school performance. Our

contribution to the K-12 education research and practice landscape is to test fundamental questions of the

eectiveness of charter schools and highlight outcomes and trends rooted in academic progress.

A study of the academic impacts of charter schools on their students is timely. Insights about the educational

eectiveness of schools, school operators, K-12 academic programs and education policy are valuable

today more than ever. The 2022 results from the National Assessment of Educational Progress removed any

ambiguity about student learning after the COVID-19 pandemic. As a country, student academic performance

has regressed by two decades in math and fallen steeply in reading, with the most severe performance

declines found among minority, poverty and special needs populations that were already struggling before

the pandemic. The need for evidence-backed approaches to sustained academic success for students

transcends demographic, economic and political divides. As school and district leaders, policy makers,

teachers, families and philanthropists build and implement plans to address pandemic-accelerated declines

in student learning, they need analysis of school and system achievement presented here to guide and

support their eorts.

1 The CMO study does not include Idaho, Maryland, and Ohio.

Contents

Table of Figures ................................................................................ 2

Project Description ............................................................................. 3

Methodology ................................................................................... 4

Summary of Findings ............................................................................ 5

Do All Students Benet? ......................................................................... 6

Where Is Positive Academic Growth Happening? .................................................... 6

What Can We Learn from CMOs? ................................................................. 8

Variations in Charter School Performance ......................................................... 8

Charter School Growth and Achievement ......................................................... 10

Exceptional Performance in Charter Schools ...................................................... 11

Evidence of Improvement over Time ............................................................. 12

Conclusions ................................................................................... 12

Implications ................................................................................... 16

Table of Figures

Figure 1: Annual Academic Growth of Charter School Students, Reading and Math ...................... 5

Figure 2: Annual Academic Growth of Charter School Students

by Charter School Type, Reading and Math ......................................................... 7

Figure 3: Academic Growth of Charter Schools Compared to Their Local TPS, Reading ................... 9

Figure 4: Academic Growth of Charter Schools Compared to Their Local TPS, Math ..................... 9

Figure 5: Academic Growth and Achievement 2015 to 2018, Reading .................................10

Figure 6: Academic Growth and Achievement 2015 to 2018, Math .................................... 11

Figure 7: Annual Academic Growth of Charter School Students across Three National Studies ........... 12

Executive Summary Volume 1

Charter School Performance

in 31 States

Volume 2

Charter Management

Organizations 2023

Volume 3

Summary of Findings,

Conclusions and Implications

As a Matter of Fact: The National Charter School Study III 2023Executive Summary | Last Updated 6/19/2023 54

Summary of Findings

Looking at year-to-year academic progress from 2015 to 2019, the typical charter school student in our

national sample had reading and math gains that outpaced their peers in the traditional public

schools (TPS) they otherwise would have attended. We report these dierences as marginal days of

additional (or fewer) days of learning on a learning benchmark of 180 days of learning each school year for

matched TPS students. In math, charter school students, on average, advanced their learning by an additional

six days in a year’s time, and in reading added 16 days of learning.

Figure 1: Annual Academic Growth of Charter School Students, Reading and Math

** Signicant at p ≤ 0.01

Figure above originally appears as Figure 1.7 in CSP31.

These average eects are across all students, all schools, for all time periods. There is considerable variation

around these averages and this variation forms the foundation for additional analyses and ndings in our

two papers.

This growth represents accelerated learning gains for tens of thousands of students across the country. Each

student and each school is a proof point that shows that it is possible to change the trajectory of learning

for students at scale, and it is possible to dramatically accelerate growth for students who have traditionally

been underserved by traditional school systems.

Methodology

This research depends on data-sharing partnership agreements with state education agencies. One common

requirement across all agreements is that the processing, analysis and security of the student-level data must

meet the Federal Education Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) requirements. This study complies with FERPA

regulations as interpreted by each state providing data.

Using both student and school level data, our resulting data set included 81 percent of tested public school

students in the United States, making it one of the largest data sets of student-level observations created

to date. We used this information to create a matched student data set with over 6,500,000 student-level

observations from over 1,853,000 charter students and a matched comparison group.

To create rigorous tests of our research questions, we need to compare charter school students’ experience

with an alternative, in this case the learning that occurs in nearby TPS. We match each charter student whose

records appear in the data with records of traditional public school students with identical traits and aligned

prior test scores who enrolled in schools that the charter student would have attended if not at their charter

school. This approach, the Virtual Control Record protocol, creates a “virtual twin” to a charter school student.

For research purposes, the virtual twin diers from the charter student only in the school attended.

This study approach mirrors the one used in the 2009 and 2013 studies. The only change to the method was

to rematch the charter school students to a new set of TPS students each year.

2

The data collected for this

study consisted of student-level demographics, school enrollment and achievement test scores in reading/

English language arts (ELA) and math To assure accurate estimates of charter school impacts, we use

statistical methods to control for dierences in student demographics and eligibility for categorical program

support such as free or reduced-price lunch eligibility and special education. In this way, we have created the

analysis so that dierences in the academic growth between the two groups are a function of which schools

they attended.

In these 2023 studies, we present our ndings about learning outcomes measured in days of learning. The

measure uses a benchmark of learning: the average student in TPS will obtain a year’s learning in a year’s

time. Computationally, the benchmark student attends school for 180 days in a year and advances their

learning by 180 days. If another student makes more (or less) progress in the same period of time, we present

that as additional (or fewer) days of learning.

2 This change meets the new standards of the What Works Clearinghouse at the National Center for Education Evaluation.

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

18

MathReading

16**

6**

Days of Learning

Executive Summary Volume 1

Charter School Performance

in 31 States

Volume 2

Charter Management

Organizations 2023

Volume 3

Summary of Findings,

Conclusions and Implications

As a Matter of Fact: The National Charter School Study III 2023Executive Summary | Last Updated 6/19/2023 76

but 10 days less growth in math than their TPS peers. These results are strongly hampered by the

performance of virtual charter schools; despite having only six percent of charter school students

enrolled, their impact on student progress of 58 fewer days of learning in reading and 124 fewer days in

math has damaging consequences for students and exerts a outsized drag on overall national results.

> Grade conguration – charter schools serving elementary, middle, and high school students had

statistically positive growth in both reading and math. Results for multilevel charter schools were

negative in math and similar to the TPS comparison groups in reading. Seeing growth in all grade

spans helps us understand that trends in the national aggregate performance are not concentrated in

particular grades.

> Continuous Enrollment – charter students overcome an initial learning dip associated with a school

change, and by their fourth year in their charter school, they show 45 days stronger growth in reading

than their TPS peers and 39 additional days of learning per year in math. The longer a student stays

enrolled in a charter school, the better the student’s academic outcomes are.

> School Management – students who attend a charter school that is part of a charter management

organization (CMO) experience signicantly accelerated growth compared to students enrolled in stand-

alone charter schools (SCS). Even so, CMO schools and SCS provide stronger learning than TPS in reading,

and CMOs do so in math. CMO-aliated students advanced by 27 additional days in reading and 23

more days in math over TPS, both of which are statistically signicant. Stand-alone charter schools still

grew signicantly more than TPS in reading by 10 additional days of learning, but were no dierent in

math. Given that SCS serve two-thirds of all students enrolled in charter schools, soft math performance

in these schools taints the otherwise decisive results in other parts of the study.

Figure 2: Annual Academic Growth of Charter School Students by Charter School Type, Reading and Math

Figure above originally appears as Figure 2.4 in CMO23.

Do All Students Benet?

When we probe these results to determine if all students benet, we nd positive results are not only present

in the aggregate, but also across student race/ethnicity groups:

> Black and Hispanic students in charter schools advance more than their TPS peers by large margins in

both math and reading.

> Multiracial, Native American, and White students in charter schools show equivalent progress to

their TPS peers in reading, but had weaker growth than their TPS peers in math.

> Asian students in charter schools showed similar growth to their TPS peers.

When we examined academic growth for special populations of students, we found that, compared with their

TPS peers:

> Charter school students in poverty had stronger growth

> English-language learner students attending charter schools had stronger growth

> Students receiving special education services had signicantly weaker growth in both math and

reading on average, though CMO-aliated students with Special Education needs have learning on par

with their TPS Special Education peers.

In the past, a common claim asserted that positive academic results in charter schools arise from advantages

that their students bring to their schooling. In some cases the claim focused on students having more

motivated parents. Another version suggests targeting behavior on the part of the school results in a student

body that is better prepared academically, a practice commonly referred to as “cherry picking” or “cream

skimming”. If true, the students in charter schools would show higher academic achievement at the point of

enrollment. In multiple analyses, we do not see signicant evidence of an undue advantage to charter schools.

In fact, we nd the opposite is true: charter schools enroll students who are disproportionately lower achieving

than the students in their former TPS.

Where Is Positive Academic Growth Happening?

Deeper into our analysis, we examine where student learning gains are occurring, and nd that positive and

strong eects exist in charter schools that vary widely by location and conguration.

> States – 18 states in the NCSS3 study produced signicantly stronger growth for students enrolled in

their charter schools when compared with their TPS peers; in 12 states, growth was similar to TPS peers.

Students attending charter schools had weaker reading growth than their TPS peers in only one state,

Oregon. In 12 states, charter school students had signicantly stronger growth in math than their peers

in TPS. In 16 states, math growth was similar between charter students and their TPS peers. Only three

states showed weaker growth for charter students compared to their peers.

> Locale – compared to their TPS peers, urban charter school students had 29 additional days of growth

per year in reading and 28 additional days of growth in math, both of which were signicant. Suburban

charter school students also had stronger growth in reading (+14 days) and in math (+3 days). Rural

students enrolled in charter schools had the equivalent of ve additional days of learning in reading,

10**

-3

27**

23**

Days of Learning

SCS CMO

-5

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

MathReading

Executive Summary Volume 1

Charter School Performance

in 31 States

Volume 2

Charter Management

Organizations 2023

Volume 3

Summary of Findings,

Conclusions and Implications

As a Matter of Fact: The National Charter School Study III 2023Executive Summary | Last Updated 6/19/2023 98

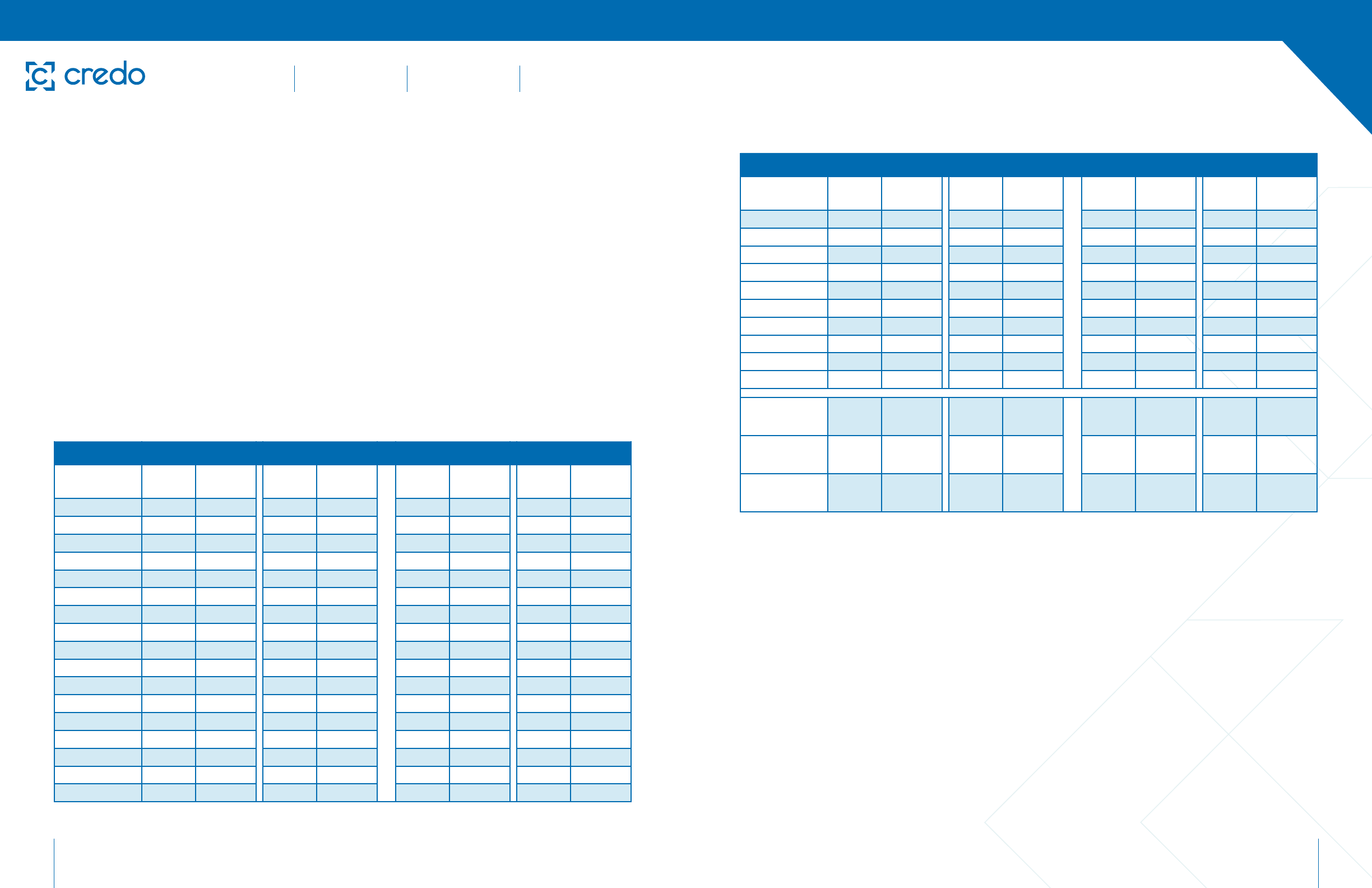

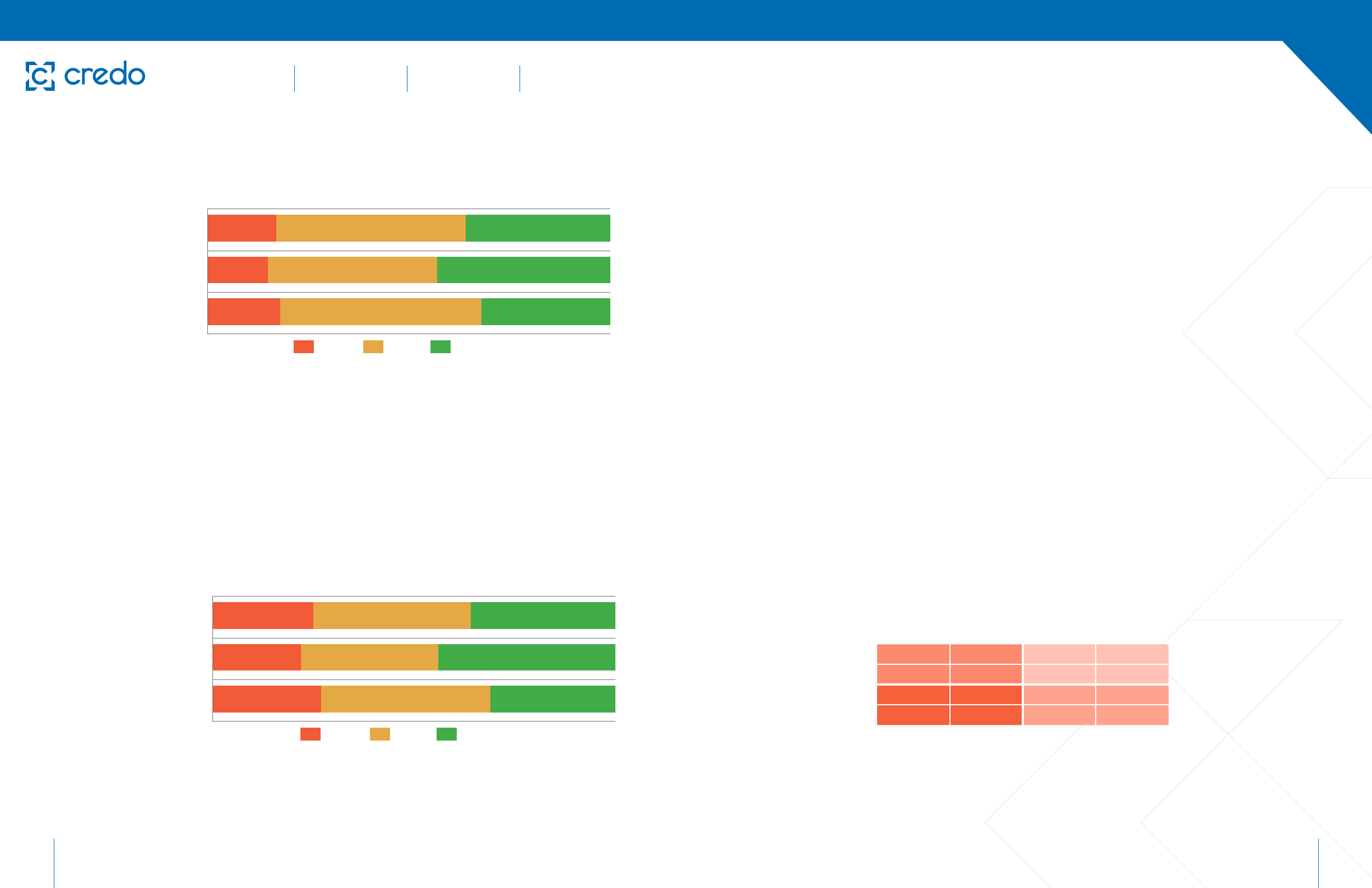

Figure 3: Academic Growth of Charter Schools Compared to Their Local TPS, Reading

Figure above draws from Figure 1.22 in CSP31, and Figure 36 in CMO23.

In math, more charter schools have weaker results than they do in reading, as presented in the gure below.

As the share of charter schools with growth greater than their TPS peers is comparable with the same

growth in reading across all categories, the driver of the overall weaker performance in math is the greater

percentage of charter schools (all, CMO-aliated and stand-alone charter schools) that perform worse than

their TPS peers. Stand-alone charter schools have the largest share of schools with lower growth in math in

comparison to their local TPS.

Figure 4: Academic Growth of Charter Schools Compared to Their Local TPS, Math

Figure above draws from Figure 1.22 in CSP31, and Figure 37 in CMO23.

These encouraging results require a note of caution. Since the reference point in these comparisons is the

growth that equivalent students in the local TPS realize, this comparison does not reveal if the dierence

is modest or large, nor does it indicate where in the range of absolute achievement the dierence occurs.

Positive dierences at the lowest levels of achievement may not be sucient to move students ahead fast

enough to reach long-term outcomes such as academic prociency or post-secondary readiness. Similarly,

a charter school may post growth results that are considered outsized for any school but still lag behind

What Can We Learn from CMOs?

Comprising one-quarter of the schools, but serving 37 percent of students in our national data set, Charter

Management Organizations (CMOs) are producing much of the learning gains we observed for charter school

students.

As with our national top-line results, we nd robust results for CMOs when we grouped their students by

race/ethnicity, special populations, where the CMOs are located, grade spans of the schools in the network

and how long a student enrolls in the school. As with all schools, there is a range of performance for CMOs,

and we share their student impacts in Appendix A.

Our analysis uncovered additional ways that CMOs are returning more positive, and often gap-busting,

results:

> New CMOs and new schools in existing CMOs open with strong results, in both cases delivering

stronger average gains for their students than their local TPS. The student gains in new CMOs are not as

strong initially as their older CMO peers. New schools started by mature CMOs deliver positive gains in

their early years that were none the less smaller than the older CMO schools.

> Size or age of a CMO does not relate to their quality, which means some CMOs are growing poorly

performing networks of schools.

> Clustering of CMOs’ schools within a single state returns signicantly more days of learning for their

students than in CMOs that operate schools in more than one state.

> CMOs that took on “turn-around” schools, absorbing those schools into their portfolios, positively

impacted results for students who remained enrolled in the turn-around school. In addition, the balance

of the CMO portfolio did not experience a downturn in student learning.

> The Charter School Growth Fund serves as a case study of charter school growth accelerators. CMOs

that the Growth Fund chooses to support have dramatically larger pre-funding learning gains than other

CMOs. The schools that existed at the time of selection remain strong. New CMO schools also open with

dramatically larger learning gains in both subjects judged against their TPS comparisons.

> Excellence at Scale puts dozens of CMOs at the forefront of eorts to provide education that is both

equitable and eective in moving student achievement to give their students full preparation for their

next steps.

Variations in Charter School Performance

In our reports, we analyze school-level performance, in addition to student-level performance, continuing to

report on growth as the outcome variable. Not every charter school provides quality academic programming

or an eective learning environment for students. Across all charter schools in our study, 36 percent have

greater growth, 47 percent have equivalent growth and 17 percent have lower growth relative to their local

TPS. CMO-aliated charter schools display stronger performance, with 43 percent having greater growth,

42 percent having equivalent growth, and 15 percent having lower growth in comparison to their local TPS.

Stand-alone charter schools have slightly more moderate results.

READING

BetterSameWorse

STAND-ALONE CHARTERS

CMO CHARTER SCHOOLS

ALL CHARTER SCHOOLS 17% 47% 36%

15% 42% 43%

18% 50% 32%

MATH

BetterSameWorse

STAND-ALONE CHARTERS

CMO CHARTER SCHOOLS

ALL CHARTER SCHOOLS 25% 39% 36%

22% 34% 44%

27% 42% 31%

Executive Summary Volume 1

Charter School Performance

in 31 States

Volume 2

Charter Management

Organizations 2023

Volume 3

Summary of Findings,

Conclusions and Implications

As a Matter of Fact: The National Charter School Study III 2023Executive Summary | Last Updated 6/19/2023 1110

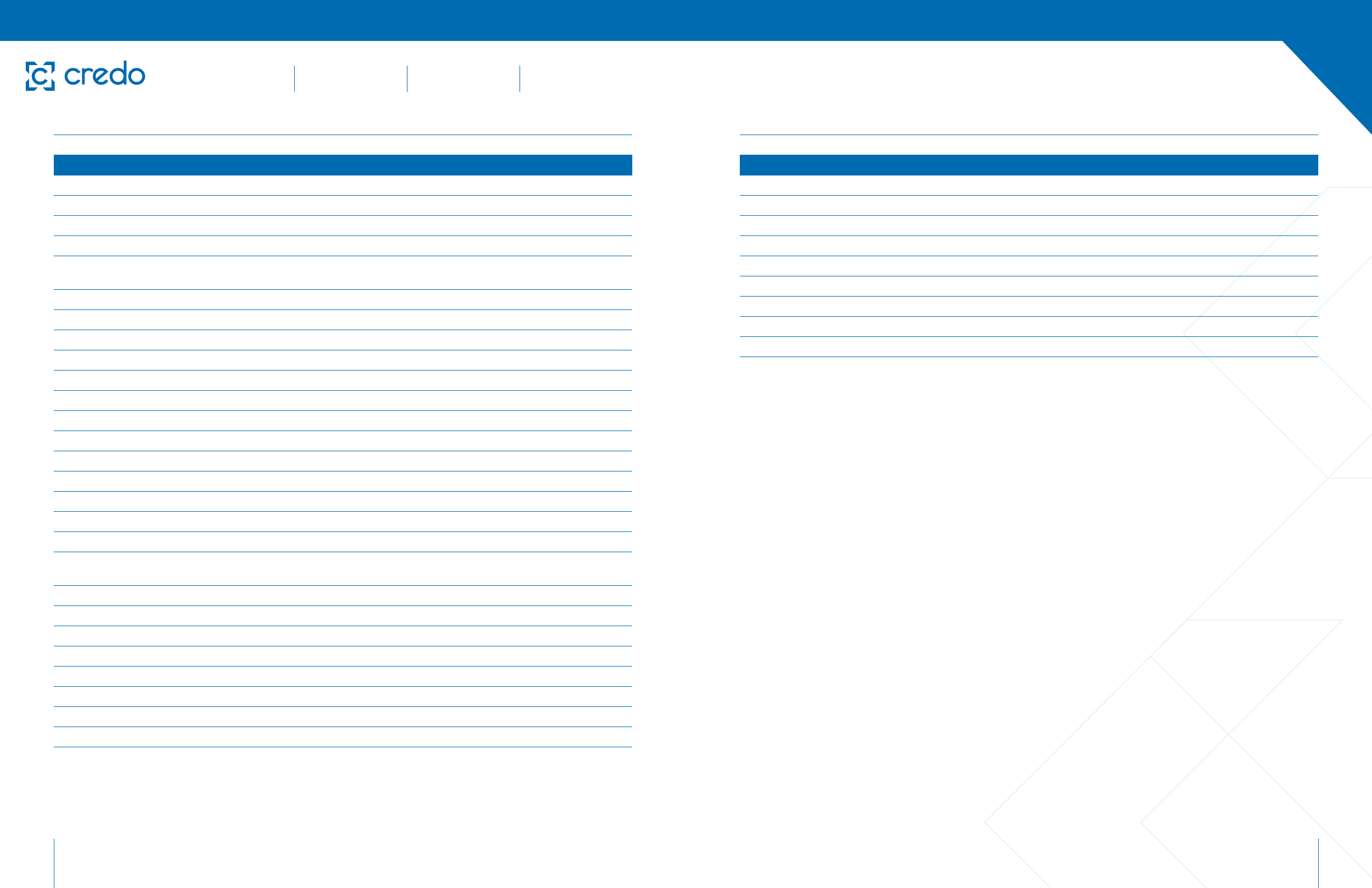

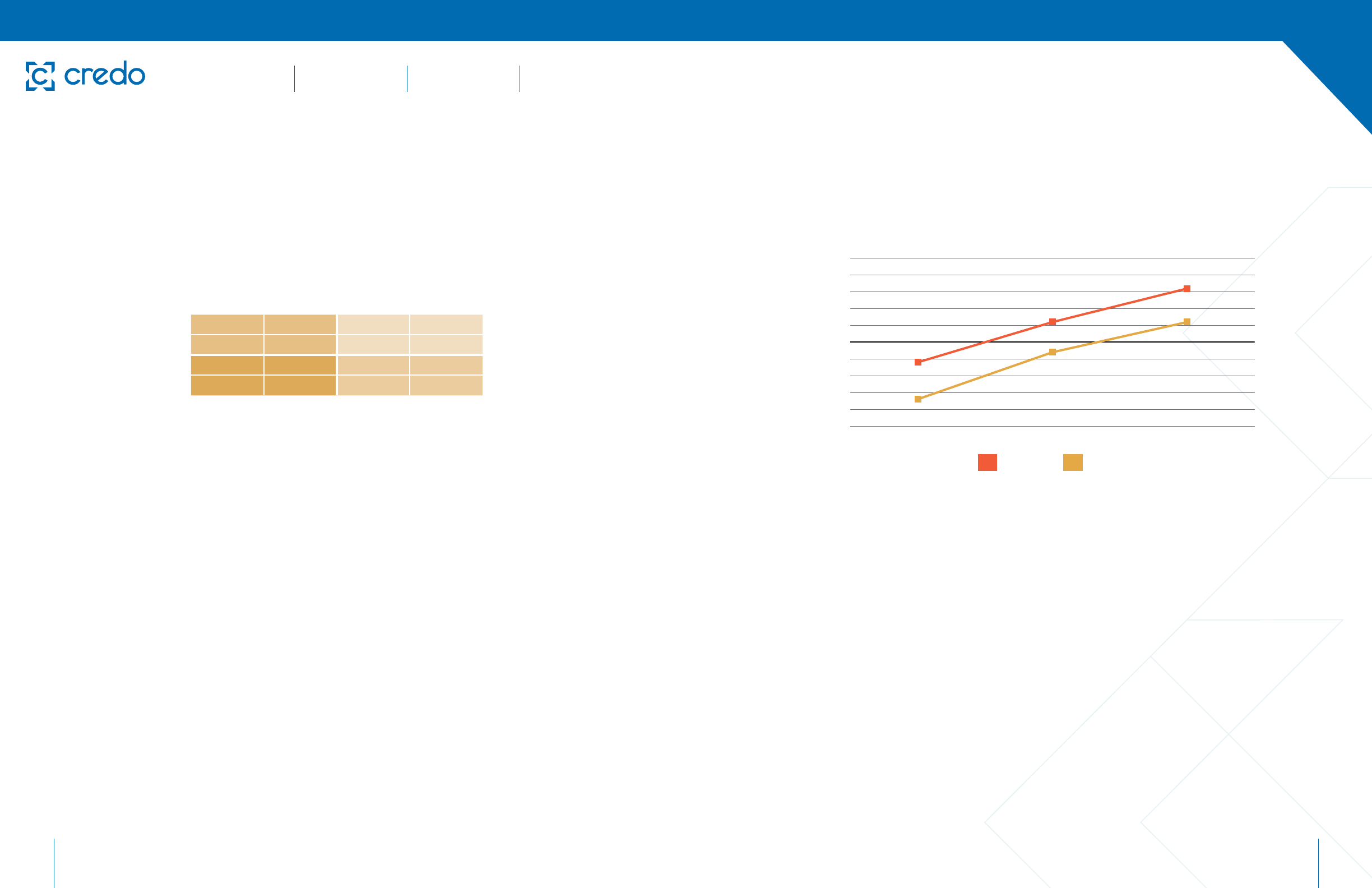

Schools that have average student

achievement above the state average

(above the 50th percentile) are presented

in the top half of the gure. In reading,

43 percent of all schools have average

performance in the upper half in their

respective states, with a majority

of those high achievement schools

also having stronger growth than

their local TPS. Zeroing in on the low-

growth/low-achievement quadrant,

207 schools (4.1 percent) in our study

have lower academic growth than their

local alternatives and have student

achievement that is below the 30th percentile of state achievement at the end of the school year.

Figure 6: Academic Growth and Achievement 2015 to 2018, Math

Low Growth,

High Achievement

High Growth,

High Achievement

Growth (in Days of Learning)

-87 0 87

0.2% 2.0% 4.9% 3.8%

70th Percentile

50th Percentile

30th Percentile

1.0% 8.6% 12.0% 7.5%

4.9% 14.3% 13.8% 6.2%

7.1% 7.5% 5.3% 1.3%

Low Growth,

Low Achievement

High Growth,

Low Achievement

Figure above originally appears as Figure 1.26 in CSP31.

In math, above average achievement exists in 40 percent of charter schools, while 60 percent of schools

have achievement that is lower than their state averages. Twenty-eight percent of schools in the data set are

high-growth/high-achievement schools, returning great gains for their students. Zeroing in again on the low-

growth/low-achievement quadrant, 348 schools (7.1 percent) have lower academic growth than their local

alternatives and have student achievement that is below the 30th percentile of state achievement at the end

of the school year.

The number of schools in the low-growth/low-achievement quadrant, though smaller in reading than in math,

remains a key concern.

the community schools in achievement. Simultaneous consideration of student academic growth and

achievement is the only way to get the complete picture of charter school performance.

Charter School Growth and Achievement

Student academic growth measures how much students advance their learning in a year’s time, and student

achievement measures the stock of their knowledge at the end of the year. We believe it is critical to examine

both growth and achievement in order to understand how well schools prepare students for next steps in

school and life. We map each school’s average growth and average achievement against the the growth of

matched TPS students and average state performance. Examining both measurements for all schools in our

national data set during the most recent growth period, we present ndings in four basic categories of school

performance:

> High Growth—High Achievement: schools that exceed the growth of their local options and whose

students are above the state average in overall achievement

> High Growth—Low Achievement: schools that exceed the growth of their local options but with overall

student achievement below the

state average

> Low Growth—High Achievement:

schools whose students exceed the

state average on achievement but

do not advance as much yearly as

their comparisons

> Low Growth—Low Achievement:

schools with lower academic

growth than their local alternatives

and whose students’ achievement

is lower than the state average at

the end of a school year.

Figure 5: Academic Growth and Achievement 2015 to 2018, Reading

Low Growth,

High Achievement

High Growth,

High Achievement

Growth (in Days of Learning)

-87 0 87

0.1% 1.5% 5.8% 2.8%

70th Percentile

50th Percentile

30th Percentile

0.7% 9.1% 17.0% 6.1%

3.1% 12.3% 17.6% 6.4%

4.1% 6.8% 5.8% 1.1%

Low Growth,

Low Achievement

High Growth,

Low Achievement

Figure above originally appears as Figure 1.25 in CSP31.

NOTE TO READERS:

The thumbnail table below presents the total

proportion of students in each major quadrant in

Figure5. These values appear on the study website as a

layer of the chart—the user can see the quadrant totals

and then drill down to see the inner-quadrant values.

11.4 31.7

26.3 30.9

NOTE TO READERS:

The thumbnail table below presents the total

proportion of students in each major quadrant in Figure

6. These values appear on the study website as a layer

of the chart—the user can see the quadrant totals and

then drill down to see the inner-quadrant values.

11.8 28.2

33.8 26.4

Executive Summary Volume 1

Charter School Performance

in 31 States

Volume 2

Charter Management

Organizations 2023

Volume 3

Summary of Findings,

Conclusions and Implications

As a Matter of Fact: The National Charter School Study III 2023Executive Summary | Last Updated 6/19/2023 1312

1. In both reading and math, charter schools provide students with stronger learning compared with the

learning in the traditional public schools that are otherwise available to them.

Across the broad range of charter schools, the evidence suggests that they are a robust education option

under many conditions. Whether stand-alone or networked, charter schools operate by law mainly on

their own, making decisions they expect will serve their students well. According to our latest ndings, the

autonomy given to them usually yields positive results. The majority of charter schools provide better year-

to-year outcomes for students compared to their traditional public-school options. Most of these schools

perform better to such a degree that the dierence is statistically signicant.

The results stand up to deeper investigation. Charter schools produce superior student gains despite

enrolling a more challenging student population than their adjacent TPS. They move Black and Hispanic

students and students in poverty ahead in their learning faster than if they enrolled in their local TPS. They

are more successful than the local public school alternatives across most grade spans and community

settings. These results show that charter schools use their exibility to be responsive to the local needs of

their communities.

These ndings generalize into lessons for policy leaders, educators, and funders. Knowing that the average student

in the average charter school can outperform their TPS peers raises important questions about the priority placed

on student outcomes in education decisions in many communities.

2. Some charter schools provide less student learning than their local district schools, although a larger

proportion delivers better learning outcomes. The latter group includes over 1,000 charter schools

managing stang and resources to deliver superior academic results that eliminate the learning gap

across student groups.

Vital lessons also come from the distribution of school performance around the average. Over the past 30

years, small, large, urban, rural, networked or stand-alone charter schools, autonomous and independent of

each other, have arrived at their own solutions for giving their students stronger learning experiences. The

discretion that charter schools enjoy does not guarantee that each school or every charter network realizes

strong student outcomes. Our study illuminated the range of learning across schools.

Despite declining shares, there remain a concerning number of charter schools with weaker student

outcomes. While lower-performing schools make up a larger share of stand-alone charter schools, CMOs and

networks also have a substantial share that produces low gains for their students. This study has profound

implications for charter schools and charter networks that do not support student learning. Charter boards

and authorizers are the accountability side of the charter school equation. They evaluate school performance

and, if necessary, dictate remedies. As our analysis shows, disturbing numbers of charter schools and

networks have low learning levels. There are brick-and-mortar, online, networked, and stand-alone charter

schools with sub-par results.

The number of school closures we observed in the years of this study was small compared to the counts of

schools with the lowest student growth and academic achievement. Since primary and secondary education

is essential to the social contract, providing a foundation for future opportunities, the claim of “choice” cannot

justify derailing students’ preparation. Especially in the post-COVID era, the need for charter boards and

authorizers to address under-performance in their schools has never been more critical.

Exceptional Performance in Charter Schools

Perhaps the most revealing nding of our study is that more than 1,000 schools have eliminated learning

disparities for their students and moved their achievement ahead of their respective state’s average

performance. We refer to these schools as “gap-busting” charter schools. They provide strong empirical

proof that high-quality, high-equality education is possible anywhere. More critically, we found that dozens

of CMOs have created these results across their portfolios, demonstrating the ability to scale equitable

education that can change lives.

Evidence of Improvement over Time

Findings from this study take on even more weight when considered in the historical context of the 15 years

of CREDO studies on student academic progress in charter schools. Between the 2009 and 2023 studies,

against a backdrop of at performance for the nation as a whole, the trend of learning gains for students

enrolled in charter schools is both large and positive.

Figure 7: Annual Academic Growth of Charter School Students across Three National Studies

** Signicant at p ≤ 0.01

Figure above originally appears as Figure 1.8 in CSP31.

Conclusions

The outcomes of these studies are largely positive and support several conclusions about the current

landscape of charter schools across America. Perhaps more importantly, the opportunity to position these

ndings in the larger body of research leads to a number of implications about the fundamental policies and

practices of charter schooling at a more global level.

-6**

-17**

Days of Learning

-25

-20

-15

-10

-5

0

5

10

15

20

25

3rd Study2nd Study1st Study

-3

6**

6**

16**

MathReading

Executive Summary Volume 1

Charter School Performance

in 31 States

Volume 2

Charter Management

Organizations 2023

Volume 3

Summary of Findings,

Conclusions and Implications

As a Matter of Fact: The National Charter School Study III 2023Executive Summary | Last Updated 6/19/2023 1514

or portfolio size, we see high- and low-impact CMOs and networks. This further supports earlier CREDO

research that showed that CMOs only replicate the quality they already have. The implications of replicating

schools with weak results is clear. The big upside is the ability of dozens of CMOs to scale their gap-busting

performance. Additionally, CMOs that concentrate their operations within a single state have stronger gains

than multistate CMOs, though both groups do well by their students.

Programs of external funding and support to CMOs to grow their networks, represented here by the Charter

School Growth Fund, focus on some of the stronger CMOs and networks in our study. After high-performing

CMOs receive endorsement, the learning of students in those CMO schools rises in reading but holds steady

in math.

The majority of new CMO schools are no better or worse than the parent organization has already produced, so

decisions to approve applications by CMOs to open new schools must consider the contributions to student learning

of schools in the existing portfolio.

CMO growth accelerators help augment board and authorizer reviews through their extensive selection process; the

growth of their grant-receiving CMOs maintains the strong student learning that led to their selection. The expansion

of these high-quality schools and networks benets more students and communities.

4. Charter schools and networks improve over time, as do the systems that oversee them.

Insights about improvement in schools and networks stem from this study and CREDO’s prior multistate

studies.

In the years of this study, student growth in charter schools was the strongest observed in any of CREDO’s

multistate studies. Added to the results from the previous two studies, a strong trend of improvement

becomes clear. We see substantial increases in student learning in CMOs in both tested subjects and in

reading for stand-alone charter schools. Even the nding of no dierence in math learning in stand-alone

charter schools vis a vis TPS, a decline from the 2017 study results, still marks an improvement from the

statistically signicant negative results in the rst CMO vs. stand-alone comparisons in 2013.

A better understanding of the improvement in the sector comes from two dierent ndings. The rst is

that the largest share of improvement comes from existing charter schools. Compared to the National

Assessment of Education Progress (NAEP) trend, evidence of schools getting better over time is welcome

news.

Second, new schools opened with stronger results than at any time in the past. Growth in the number of

CMOs since the last study plays a role. Many stand-alone charter schools also pushed their results upward.

Strengthening authorizer standards and practices, a drive that took root in the 2010s, also sets a higher bar

that resulted in better schools opening.

Finding ways to improve student academic outcomes is an ambition shared by policy and community leaders,

educators, funders and parents. Charter school results show that change for the better is possible in the larger

education system. The key to improvement lies outside any particular school or network model, though many are

worthy of emulation. It is simply not possible to drive single solutions through the diverse landscape that is U.S.

public education. Lessons from the charter school experience and results may be helpful in charting a future course

in public education.

Closure is not the sole remedy. As we learned from our special investigation, the “takeover“ of

underperforming schools by strong CMOs led to improved student learning for the students who remained

enrolled before and after the transfer. The gains did not adversely aect student academic progress in the

rest of the CMOs’ schools. This policy tool may have broader utility than previously realized.

At the high end of the performance range, good news exists in the growing share of schools outpacing

learning in their local TPS. In both subjects and for both CMO and stand-alone schools, larger shares are

“better than” and a smaller share is “weaker than” compared to earlier work.

The real surprise of the study is the number of charter schools that have achieved educational equity for

their students: we call them “gap-busting” schools. Ensuring equivalent yearly growth across student groups

has two critical consequences. First, ensuring minority and poverty students learn on par with or better

than their White peers interrupts or reduces the achievement gap. It happens regularly in a large swath of

charter schools. More critically, there is strong evidence that these gap-busting schools can be scaled. Added

to the traditional district schools that achieve similar results, this is the life-transforming education that so

many students need. Second, these schools deliver hundreds of independent proof points that learning gaps

between student groups are not structural or inevitable; better results are possible.

Charter schools function as a portfolio, and their varied impacts on student learning are expected. Charter

school boards and authorizers are responsible for ensuring students perform well. Evidence shows that the

charter school enterprise benets students, and its positive outliers (e.g., gap busters) can pressure the rest

of the system.

The near-term implication for charter school boards and authorizers is two-pronged. Addressing chronic and/or

severe underperformance is necessary and imperative in the current education climate. Identifying high-impact

exemplars for probationary charter schools to study and emulate is possible. Transfer of sub-par schools to higher-

performing operators could be part of a larger incentive for growth and replication. At the same time, authorizers

might consider longer charter terms for charter schools that consistently demonstrate outstanding student learning

success.

Education leaders and policy makers need to understand that in eorts to improve, some failure is inevitable. Any

subsequent failure to address the poor performance compounds the damage. It also blocks constructive learning for

the future. Strong examples of authorizing exist and should be emulated.

Leadership and responsibility demand embracing practices and policies that lead to better results for students, not

maintaining the status quo.

3. The larger scale of Charter Management Organizations does not guarantee high performance—but on

balance, it helps.

When taken as a whole, schools managed by Charter Management Organizations and charter networks bring

a greater learning benet to students compared to stand-alone charter schools. Despite the dierences, both

groups of charter schools have had larger student success than traditional public schools with respect to

reading. We note, however, that math gains in stand-alone charter schools were equivalent to TPS learning.

Our analysis highlights attributes of higher-performing CMOs and networks that could be useful in future

discussions. Size or age of the CMO does not relate to student learning: at every increment of CMO age

Executive Summary Volume 1

Charter School Performance

in 31 States

Volume 2

Charter Management

Organizations 2023

Volume 3

Summary of Findings,

Conclusions and Implications

As a Matter of Fact: The National Charter School Study III 2023Executive Summary | Last Updated 6/19/2023 1716

Poorly performing charter schools are often ignored. A number of these schools were observed during this

study window. There is data to assess policy leaders and authorizers to hold them accountable for protecting

children’s futures. As tough as closing schools is, the disservice of not closing poorly performing schools has

large and lingering ripple eects.

Our results show that the framework of charter schools helps current students and strengthens public

education overall. We contend these incentives have broader applicability in public schools and see signs

of their spread. Collaborations between charter schools and local district schools have grown over time.

Some states, including Kentucky and Maine, have adopted policies to give educators freedom in adjusting

instruction and boosting performance. However, uptake is slow.

In the year 2023, the importance of strong academic achievement among America’s students has never

been greater. The students hit hardest by school closures during the coronavirus pandemic are precisely

those whom this research illuminates as being able to benet the most from charter schools. In this study

thousands of charter schools have proved that we can do better for our students. The current number of

students beneting from these schools is 3.7 million, but the number could drastically increase if more

schools agreed to the same arrangement. Whether it be termed “charter school” or something else, the

deduction from this data is that when both sides of the equation—exibility and accountability—are working

together for more schools, more students’ academic results will improve.

References

Boast, L., Cliord, B., & Doyle, D. (2020). Learning in real time: How charter schools served students during

COVID-19 closures. National Alliance for Public Charter Schools. Retrieved from https://www.publiccharters.

org/our-work/publications/how-charter-schools-served-students-during-covid-19-closures

Childs, J., Grooms, A., & Mozley, M. P. (2022). Hidden in (virtual) plain sight: A charter district’s focus on

attendance during COVID-19. Education and Urban Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/00131245211065414

CREDO. (2022). Charter Schools’ Response to the Pandemic in California, New York and Washington State.

The Center for Research on Education Outcomes. https://credo.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/

Charter-School-COVID-Final.pdf

Henderson, M. B., Peterson, P. E., Houston, D., & West, M. R. (2021). What American families experienced

when COVID-19 closed their schools. Education Next, 21(1), 22-31.

Mumma, K. S., & West, M. R. (2018). Charter School Authorizing in California. Technical Report. Getting Down

to Facts II. Policy Analysis for California Education, PACE.

NACSA. (2016). State of Charter Authorizing 2016. Retrieved April 24, 2023 from https://qualitycharters.org/

wp-content/uploads/2018/07/State-of-Charter-School-Authorizing-2016-Findings.pdf

Implications

The charter school policy framework sets the conditions for charter schools’ growing positive outcomes. It

is the fundamental common denominator in every case, and its role is powerful.

The framework oers a divergent approach from the conventional strategy for public schools. The “exibility

for accountability” construct is not just a catchphrase. It is a distinctly dierent mode of operation. The

“loose-tight” parameters of the framework create incentives to which schools and networks respond. The

incentives nd positive support in this study’s ndings and the broader trends. While our study design cannot

make causal claims (because randomly assigning schools to the traditional or charter school approach has yet

to happen), it can deliver a plausible argument of the value of the policy based on available evidence.

On the “loose” side of the approach, the framework establishes a policy of possibility where educators,

leaders and boards of directors have the discretion to build and deliver curriculum and instruction that meets

high standards for learning and is responsive to local needs.

According to this study, there are a lot of positive possibilities. The process has led to many successful schools

nationwide, often with meaningful innovations. The diversity of schools illuminates an important feature of

the framework: success is attainable via many paths. Over time, many have sought and gained permission to

expand and then shown the ability to create strong student learning at scale.

Students in these schools, especially minority students and those in poverty, make larger advances than in

local public schools. Beyond the benets for their students, successful charter schools deliver critical proof

points of ways to improve outcomes for students. In the current regulatory climate, it is dicult to imagine

how similar eorts could become conventional among traditional public schools.

Beyond exibility in school design, school teams have the leeway to tinker with their operations. The results

show that existing charter schools have improved over time. The proportion of charter schools with superior

results is on the rise. The share that lags behind the local TPS alternatives is also shrinking. This means

schools and networks use their discretion and autonomy to foster a standing capacity to adapt over time.

3

Accordingly, the framework also aims to be “tight” at key points as schools open and mature. Authorizers

are expected to behave as governors of quality. They set the bar to receive initial permission to operate,

which exerts quality and safety controls at the outset. Others have documented stronger standards among

authorizers in the review and approval of new applications (Mumma & West, 2018). The ndings of stronger

new schools in this study compared to earlier results attest to the eort and to the CMO replications and new

charter schools that meet the higher bar.

Authorizing is a delicate job that requires resources, expertise and substantial political acumen and courage.

There is growing attention to authorizers adopting rigorous standards and practices and using a variety of

performance data to evaluate schools that apply for renewal (NACSA, 2016).

3 We saw that capacity in stark terms when we examined how charter schools in three states responded to the COVID-instigated school closure orders (CREDO,

2022). Rapid transformation into remote instructional mode; acquisition and distribution of food, technology, or internet access; and strengthening of personal

supports were widespread. Return to in-person instruction in the fall of 2020 was nearly universal. These points rest admittedly on smaller bases of qualitative

evidence, but they provide human dimensions to the point that the present quantitative analysis illuminates nationally. See also: Boast et al. (2020); Henderson

et al. (2021); Childs et al. (2022).

As a Matter of Fact:

The National

Charter School

Study III 2023

As a Matter of Fact:

The National Charter

School Study III 2023

Volume 1

Charter School

Performance in 31 States

Authors

Margaret E. Raymond, Ph.D.

James L. Woodworth, Ph.D., Lead Analyst- 31 State Study

Won Fy Lee, Ph.D., Lead Analyst- CMO Study

Sally Bachofer, Ed.M.

Contributors

Meghan E. Cotter Mazzola, M.S.

William D. Snow

Tzvetelina Sabkova, M.A.

Executive Summary Volume 1

Charter School Performance

in 31 States

Volume 2

Charter Management

Organizations 2023

Volume 3

Summary of Findings,

Conclusions and Implications

As a Matter of Fact: The National Charter School Study III 2023 21

© 2023 CREDO

Center for Research on Education Outcomes

Stanford University

Stanford, CA

https://credo.stanford.edu

CREDO, the Center for Research on Education Outcomes at Stanford University, was established to improve

empirical evidence about education reform and student performance at the primary and secondary levels.

CREDO at Stanford University supports education organizations and policy makers in using reliable research

and program evaluation to assess the performance of education initiatives. CREDO’s valuable insight helps

educators and policy makers to strengthen their focus on the results of innovative programs, curricula, policies

and accountability practices.

Acknowledgments

CREDO gratefully acknowledges the support of the state education agencies that contributed their data to this

partnership. Our data access partnerships form the foundation of CREDO’s work, without which studies like

this would be impossible. We strive daily to justify the condence placed in us.

The research presented here uses condential data from state departments of education. The views expressed

herein do not necessarily represent the positions or policies of the organizations noted above. No ocial

endorsement of any product, commodity, service or enterprise mentioned in this publication is intended or

should be inferred. In addition:

> The research presented here utilizes SLDS Data from the Idaho State Board of Education (SBOE) and the

Idaho State Department of Education. Any research errors are the sole responsibility of the author(s).

> This research result used data structured and maintained by the MERI-Michigan Education Data Center

(MEDC). MEDC data is modied for analysis purposes using rules governed by MEDC and is not identical

to data collected and maintained by the Michigan Department of Education (MDE) and/or Michigan’s

Center for Educational Performance and Information (CEPI). Results, information and opinions solely

represent the analysis, information and opinions of the author(s) and are not endorsed by, or reect the

views or positions of, grantors, MDE and CEPI or any employee thereof.

> Data for this report was provided by the Missouri Department of Elementary and Secondary Education.

> The conclusions of this research do not necessarily reect the opinions or ocial position of the Texas

Education Agency, the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board, or the State of Texas.

The analysis and conclusions contained herein are exclusively those of the authors and are not endorsed by

any of CREDO’s supporting organizations, their governing boards, or the state governments, state education

departments or school districts that participated in this study. All errors are attributable to the authors.

CREDO also acknowledges the support of the Walton Family Foundation and The City Fund for supporting

this research.

Executive Summary Volume 1

Charter School Performance

in 31 States

Volume 2

Charter Management

Organizations 2023

Volume 3

Summary of Findings,

Conclusions and Implications

As a Matter of Fact: The National Charter School Study III 2023Volume 1: Charter School Performance in 31 States 2322

1.5 School-Level Impacts ....................................................................... 61

School-Level Academic Growth .............................................................. 61

School-Level Academic Growth by State ......................................................63

1.6 Charter School Academic Growth and Achievement .............................................65

1.7 Gap-Closing Charter Schools .................................................................69

Table of Figures

Figure 1.1: CREDO Virtual Control Record (VCR) Methodology ........................................ 32

Figure 1.2: Average Achievement of All Charter Students by State, Math 2017 ..........................38

Figure 1.3: Average Academic Growth of Charter Students by State, Math 2017 ........................40

Figure 1.4: Percent of Charter School Student Enrollment by Location ................................43

Figure 1.5: Percent of Charter Schools by Grade Level ..............................................44

Figure 1.6: Annual Academic Growth of Charter School Students, Reading and Math ...................45

Figure 1.7: Annual Academic Growth of Charter School Students across Three National Studies. . . . . . . . . . 46

Figure 1.8: Annual Academic Growth in Previously Studied Schools Compared to Current Schools. . . . . . . . 47

Figure 1.9: RECAP: Average Academic Growth for Charter School Students

by Charter School Type, Reading and Math .................................................... 48

Figure 1.10: State Level Average Charter School Student Academic Growth, Reading ....................49

Figure 1.11: State Level Average Charter School Student Academic Growth, Math ......................50

Figure 1.12: Average Reading Growth of Charter School Students by State, 2013 vs 2023 ................ 51

Figure 1.13: Average Math Growth of Charter School Students by State, 2013 vs 2023 ................... 51

Figure 1.14: Days of Learning for Charter School and TPS Students by Race/Ethnicity, Reading and Math ..53

Figure 1.15: Annual Academic Growth for Charter School Students in Special Populations ............... 55

Figure 1.16: Annual Academic Growth for Charter School Students with Compound Designations ........56

Figure 1.17: Annual Academic Growth of Charter School Students by Grade Level ...................... 57

Figure 1.18: Annual Academic Growth for Charter School Students by School Mode, Reading and Math ...58

Figure 1.19: Annual Academic Growth for Charter School Students by Years of Enrollment .............. 59

Figure 1.20: Charter School Student Academic Growth by School Location, Reading and Math ........... 61

Figure 1.21: Academic Growth of Charter Schools Compared to Their Local TPS, Math and Reading ......62

Figure 1.22: Academic Growth of Charter Schools Compared to Their

Local TPS across Studies, Reading and Math ..................................................63

Figure 1.23: Average Academic Growth in Charter Schools versus. Their Local TPS by State: Reading .....64

Figure 1.24: Average Academic Growth in Charter Schools versus. Their Local TPS by State: Math ........64

Figure 1.25: Academic Growth and Achievement, Reading ...........................................66

Figure 1.26: Academic Growth and Achievement, Math .............................................67

Contents

Table of Figures ...............................................................................23

Table of Tables ................................................................................24

1.1 Introduction ...............................................................................25

A Brief Primer on Charter Schools in the United States .........................................26

The Structure of the National Charter School Study III Report ...................................26

Aggregate Charter Student Academic Progress .............................................26

Academic Progress for Student Groups in Charter Schools ...................................27

Student Academic Progress in Dierent School Settings .....................................27

The Role of Charter Management Organizations in Student Academic Progress .................28

1.2 Methods and Data ..........................................................................28

Methodology ..............................................................................28

Consolidating Student Data from Multiple States ..............................................30

Selection of Comparison Observations .......................................................31

Student Match Rates .......................................................................33

School Match Rates ........................................................................33

Fair Analysis of Impacts on Student Academic Progress .........................................33

Basic Analytic Models ......................................................................34

How We Present the Results ................................................................34

1.3 Descriptive Statistics .......................................................................35

Student Characteristics .....................................................................35

Race/Ethnicity Composition of Matched Charter Students ......................................36

Other Student Characteristics ...............................................................37

Perceptions of Charter School Student Advantage ............................................. 41

School Characteristics ......................................................................43

School Location. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43

School Level/ Grade Span ................................................................44

1.4 Analytic Findings ...........................................................................45

Academic Growth of Charter School Students .................................................45

RECAP: Academic Growth of Charter School Students by Type of School ..........................48

Charter School Student Academic Growth by State .............................................49

Changes in Charter School Student Academic Growth by State ..................................50

Dierences in Academic Growth by Charter School Student Characteristics ....................... 52

Dierences by Race/Ethnicity ...............................................................52

Academic Growth for Charter School Students in Special Populations .........................54

Student Annual Academic Growth by Charter School Grade Level .............................56

Annual Academic Growth of Online Charter School Students ....................................58

Academic Growth by Continuous Enrollment in Charter School .................................. 59

Charter School Student Academic Growth by Location of their School ............................60

Executive Summary Volume 1

Charter School Performance

in 31 States

Volume 2

Charter Management

Organizations 2023

Volume 3

Summary of Findings,

Conclusions and Implications

As a Matter of Fact: The National Charter School Study III 2023Volume 1: Charter School Performance in 31 States 2524

1.1 Introduction

The year 1992—the year that City Academy Charter School opened in St. Paul, Minnesota—was over 30 years

ago. The fundamental bargain of public charter schools—“exibility for accountability”—took root in the

school’s rst charter and in the more than 7,800 public charter schools that came after. With over 3.7 million

students currently enrolled in charter schools in 43 states and the District of Columbia, charter schools

represent the largest experiment in public school innovation in the nation’s history.

The current study is the third multistate study of charter school eectiveness—the rst was released in 2009

and the second in 2013. It adds to a large slate of charter school research

1

released by CREDO in 2006. This

study covers the education experience of 2,080,913 unique students enrolled in charter schools in 31 states

from 2014-15 to 2018-19. As our work in this area uses the same peer-reviewed research design and analytic

approaches, the results across studies provide the basis for examining charter school performance trends

since 2006.

CREDO’s work joins a body of research on the subject (Booker et al., 2009; Mead et al., 2015). Our unique

contribution lies in the scope of the eort: CREDO uses longitudinal student-level information derived from

state administrative data from 29 states plus the District of Columbia and New York City.

2

In our research,

we include 94 percent of the nation’s charter school students in tested grades. We use a detailed matching

method to ensure that our analytic comparisons to students in district schools are as precise as the data

allows. Consequently, our ndings carry strong levels of reliability and validity.

A study of the academic impacts of charter schools on their students is timely. Insights about the educational

eectiveness of schools, school operators, K-12 academic programs and education policy are valuable

today more than ever. The 2022 results from the National Assessment of Educational Progress removed any

ambiguity about student learning after the COVID-19 pandemic. As a country, student academic performance

has regressed by two decades in math and fallen steeply in reading, with the most severe performance

declines found among minority, poverty and special needs populations that were already struggling before

the pandemic. The need for evidence-backed approaches to sustained academic success for students

transcends demographic, economic and political divides. As school and district leaders, policy makers,

teachers, families, and philanthropists build and implement plans to address pandemic-accelerated declines

in student learning, they need the analysis of school and system achievement presented here to guide and

support their eorts.

1 Center for Research on Education Outcomes, http://credo.stanford.edu.

2 We refer to these 31 jurisdictions as “states” to maintain consistency with previous studies. New York City data is not included in New York results. The two

groups are mutually exclusive for this study.

Table of Tables

Table 1.1: States Participating in Each CREDO National Charter School Study (NCSS) ....................29

Table 1.2: Match Rates by Race/Ethnic Group ......................................................33

Table 1.3 Demographic Comparison of Students in TPS, Feeders,

and Charter Schools (Brick-and-Mortar and Virtual) in 31 States, 2017–18 .........................35

Table 1.4: Race/Ethnic Proportions for All versus Matched Students ..................................36

Table 1.5: Special Population Proportions for All versus Matched Students ............................37

Table 1.6: Achievement Decile Distribution of Charter Enrollees by State 2017, Math .................... 39

Table 1.7: Percentage Dierences between Entering Charter Students

and Feeder School Students by Decile of Achievement .........................................42

Table 1.8: Charter School Student Academic Growth by Grade Level

across Studies, Reading and Math ...........................................................57

Table 1.9: Charter School Student Academic Growth by Years of Charter

Enrollment across Studies, Reading and Math .................................................60

Table 1.10: Charter Schools with No Learning Gaps and High Achievement ............................69

Executive Summary Volume 1

Charter School Performance

in 31 States

Volume 2

Charter Management

Organizations 2023

Volume 3

Summary of Findings,

Conclusions and Implications

As a Matter of Fact: The National Charter School Study III 2023Volume 1: Charter School Performance in 31 States 2726

The current results are larger than what we reported in the second national study, which were larger than the

rst national study. The three studies taken together produce a solid positive trend over the 15 school years

between 2004 and 2019. Notably, the upward trend was due to existing charter schools improving over time,

not an inux of higher-performing new schools.

Academic Progress for Student Groups in Charter Schools

The second set of ndings addresses how consistent the results are for all students. We again report these

dierences as marginal days of additional (or fewer) days of learning on a benchmark of 180 days of learning

in a single school year. We found important dierences in the amount of learning for dierent groupings of

students enrolled in charter schools in our study.

Consistent with our earlier studies, we found signicant variations in charter student learning when we exam-

ined results for students in dierent racial/ethnic groups. In math performance, Asian/Pacic Islander students

in charter schools realized more than a year of academic progress in a school year. In contrast, Black, Hispanic,

White and Native American students have academic gains that fall short of a year’s progress in a year. In

reading performance, Asian/Pacic Islander students made gains well above the benchmark 180 days of

learning, while White and Hispanic students were closer to the benchmark of one year of growth in a year.

Black and Native American students fell considerably short of the 180 days of learning mark.

Despite overall low growth, Black and Hispanic students in charter schools fared better when compared with

the learning gains of their TPS peers. White, Native American and multiracial students had smaller learning

gains than their TPS comparisons.

Charter school students in poverty and their TPS counterparts fell short of the learning of their non-poverty

peers. Despite this, charter students in poverty had stronger growth, equal to 17 additional days of learning in

math and 23 additional days of learning in reading, than their TPS peers in poverty. Likewise, English-language

learner (ELL) students who attended charter schools also had stronger growth in math (eight days) and reading

(six days) than their TPS peers but were still left considerably behind non-ELL students. Students receiving

special education services had signicantly weaker growth in both math and reading than their TPS peers.

Specically, they grew 14 fewer days in math and 13 fewer in reading.

Student Academic Progress in Dierent School Settings

As the conversation about public education focuses on schools as units of analysis, the third set of conclusions

refers to the eects of charter school students’ learning when dierent school characteristics are considered.

Across the sample of 6,802 charter schools in math, 36 percent had overall learning gains that were statistically

signicantly larger than the local TPS alternatives. One quarter posted statistically signicantly smaller results,

and 39 percent had gains equivalent to their local peer schools. In reading, the results were stronger: 36

percent had statistically signicantly larger learning results, 47 percent posted gains on par with their TPS

peers, and 17 percent had statistically signicantly smaller results. At both ends of performance, these results

improve on earlier results from the last national study—a greater share of charter schools is stronger than the

local option and a smaller percentage is worse.

A Brief Primer on Charter Schools in the United States

Enabling legislation allows charter school founders and operators to design and tailor organizational

structures, stang and instructional approaches to provide their students with an alternative to local district

schools. They pursue dierent missions such as STEAM, college prep, social justice or new technologies.

They can be small or large; they can operate as single schools or in school networks. Some charter schools

outsource some or all of their operations to outside vendors. Some charter schools mirror traditional public

school (TPS) grade level or grade band congurations, and others serve students K-12 in one school. Some

charter schools own and operate their facilities, and some are tenants of local school districts or rent space

from commercial landlords.

Charter schools operate under governing boards separate from local district school boards. Following the “ex-

ibility for accountability” construct, in exchange for discretion in school design and operation, charter schools

must undergo periodic accountability reviews to remain open and in good standing. These accountability

reviews weigh the schools’ operational and scal health and student academic performance.

Thirty-seven states allow multiple schools to be held and operated under a common management structure

known as charter networks or charter management organizations (CMOs). This option has increased the

number of available charter school seats, yet it raises questions of scalability and quality. This study examines

these questions and the performance of charter schools and charter networks against the legislative and

regulatory incentives in place.

The Structure of the National Charter School Study III Report

We report four sets of ndings, summarized below. The rst three are included in this volume, Charter School

Performance in 31 States (CSP31). The fourth is presented in Volume 2, Charter Management Organizations 2023

(CMO23).

Aggregate Charter Student Academic Progress

The rst set of ndings focuses on student performance in all charter schools included in the study. Looking

at year-to-year academic progress from 2015 to 2019, tested students enrolled in all charter schools in the

31 states had reading and math gains that outpaced their peers in the TPS that charter school students

otherwise would have attended. We report these dierences as marginal days of additional (or fewer) days

of learning on a learning benchmark of 180 days each school year. In math, charter school students, on aver-

age, were found to advance their learning by an additional six days in a year. For reading, on average, their

learning added 16 days of learning.

In the past, a common claim asserted that positive academic results in charter schools arise from advantages

that their students bring to their schooling. In some cases the claim focused on students having more motivat-

ed parents. Another version suggests targeting behavior on the part of the school results in a student body

that is better prepared academically, a practice commonly referred to as “cherry picking” or “cream skimming.”

If true, the students in charter schools would show higher academic achievement at the point of enrollment.

In multiple analyses, we do not see signicant evidence of an undue advantage to charter schools. In fact, we

nd the opposite is true: charter schools enroll students who are disproportionately lower achieving than

the students in their former TPS.

Executive Summary Volume 1

Charter School Performance

in 31 States

Volume 2

Charter Management

Organizations 2023

Volume 3

Summary of Findings,

Conclusions and Implications

As a Matter of Fact: The National Charter School Study III 2023Volume 1: Charter School Performance in 31 States 2928

Table 1.1: States Participating in Each CREDO National Charter School Study (NCSS)

NCSS I - 2009 NCSS II-2013 NCSS III-2023

First School Year of Data 2000-01 2006-07 2014-15

Last School Year of Data 2007-08 2010-11 2018-19

States Included in Each Study

Arkansas Arkansas Arkansas

Arizona Arizona Arizona

California California California

Colorado (Denver) Colorado Colorado

District of Columbia District of Columbia District of Columbia

Florida Florida Florida

Georgia Georgia

Idaho

Illinois (Chicago) Illinois Illinois

Indiana Indiana

Louisiana Louisiana Louisiana

Massachusetts Massachusetts Massachusetts

Maryland

Michigan Michigan

Minnesota Minnesota Minnesota

Missouri Missouri Missouri

Nevada Nevada

New Jersey

New Mexico New Mexico New Mexico

New York New York

New York City New York City

North Carolina North Carolina North Carolina

Ohio Ohio Ohio

Oregon Oregon

Pennsylvania Pennsylvania

Rhode Island Rhode Island

South Carolina

Tennessee Tennessee

Texas Texas Texas

Utah Utah

Washington

Wisconsin

The performance of charter schools in dierent types of communities continues in earlier patterns. As seen in

earlier national studies, students in urban charter schools outpace their TPS peers and post larger gains than

their charter school peers in suburban, town or rural settings.

The academic performance of students enrolled in virtual charter schools compares poorly to the 180-day

learning standard in TPS and the performance of students enrolled in brick-and-mortar charter schools.