RAPID RE-HOUSING FOR HOMELESS FAMILIES

DEMONSTRATION PROGRAMS EVALUATION REPORT

RAPID RE-HOUSING FOR HOMELESS

FAMILIES DEMONSTRATION

PROGRAMS EVALUATION REPORT

PART I: HOW THEY WORKED—

PROCESS EVALUATION

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development | Office of Policy Development and ResearchU.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development | Office of Policy Development and Research

Visit PD&R’s website

huduser.gov

to find this report and others sponsored by HUD’s Office of Policy Development and Research (PD&R). Other services of

HUD USER, PD&R’s research information service, include listservs, special interest reports, bimonthly publications (best

practices, significant studies from other sources), access to public use databases, and a hotline (800-245-2691) for help

accessing the information you need.

RAPID RE-HOUSING FOR HOMELESS

FAMILIES DEMONSTRATION

PROGRAMS EVALUATION REPORT

PART I: HOW THEY WORKED—

PROCESS EVALUATION

Prepared for

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development

Office of Policy Development and Research

Prepared by

Martha R. Burt

Carol Wilkins

Brooke Spellman

Tracy D’Alanno

Matt White

Meghan Henry

Natalie Matthews

Abt Associates Inc.

April 2016

ii

RAPID RE-HOUSING FOR HOMELESS FAMILIES DEMONSTRATION PROGRAMS EVALUATION REPORT

Acknowledgments

Martha R. Burt led the design and implementation of the process evaluation, with signicant

support from the other site interviewers: Carol Wilkins, Brooke Spellman, Tracy D’Alanno, Matt

White, Meghan Henry, and Natalie Matthews. These seven individuals also collaborated on the

report, with key input from Dennis Culhane, the Principal Investigator for the study, and Jill

Khadduri, the Abt Project Quality Advisor. Reviewers at the U.S. Department of Housing and

Urban Development provided invaluable feedback on the rst draft of this report.

The authors especially thank the Rapid Re-housing for Homeless Families Demonstration

grantees, including staff members and community leaders who participated in the phone surveys

and onsite visits.

iii

PART I: HOW THEY WORKED—PROCESS EVALUATION

Foreword

In 2009, the U.S. Department of Housing and

Urban Development (HUD) awarded funding

to 23 communities to implement a demonstra-

tion program to expand a promising new inter-

vention for addressing homelessness among

families. The Rapid Re-housing for Homeless Fam-

ilies Demonstration (RRHD) program awarded

the rst set of federal funds intended to support

the expansion of this new model of homeless

assistance nationwide. Rapid re-housing is

designed to enable households to exit shelter

quickly by assisting them in nding a housing

unit in the community and subsequently pro-

viding them with a short-term housing subsidy

(not to exceed 18 months) along with a modest

package of housing-related services designed

to stabilize the household in anticipation of the

conclusion of rental assistance.

HUD’s evaluation of the RRHD program

sought to understand the variations among

rapid re-housing programs established in

the demonstration communities and also the

outcomes of the families served through the

program. Key observations include—

• Grantees varied greatly in all aspects of pro-

gram implementation, including (1) structure

and length of the housing subsidy, (2) breadth

of the package of supportive services offered,

(3) intensity of case management, and

(4) target population.

• Families had a low likelihood of returning to

emergency shelter within the study period—

a review of Homelessness Management

Information System, or HMIS, data found

that only 10 percent of households served

experienced at least one episode of homeless-

ness within 12 months of program exit.

• Families were highly mobile following the

end of program participation—76 percent of

households moved at least once within the

12-month period following their exit from

the RRHD program.

From the perspective of the homeless assistance

system, which has the role of reducing the

number of households that experience home-

lessness, this outcome is excellent. That said,

the high rate of mobility raises some concerns,

as does the nding that family income showed

little or no increase, and very few families

exited the program with any type of subsidized

housing assistance. These ndings suggest that

the short-term assistance offered may be just

that, and that some families who continue to

struggle with severe poverty may nd them-

selves again in housing crisis before too long.

From a homelessness prevention perspective,

this nding is vexing.

Since the time that this demonstration was ini-

tiated in 2009, communities have moved swift-

ly to implement rapid re-housing programs

and to rene the model to meet the needs of the

homeless households presenting for assistance

iv

RAPID RE-HOUSING FOR HOMELESS FAMILIES DEMONSTRATION PROGRAMS EVALUATION REPORT

and also the conditions of the local housing

market. Considerable attention has also been

paid to how communities measure the success

of their rapid re-housing programs: Should the

goal of the intervention be housing stability or

avoidance of a return to shelter? Should rapid

re-housing be considered an intervention with

long-term or short-term goals? The evidence

generated through this research effort does not

denitively answer these questions, but rather

it adds to the collection of ndings that is help-

ing to shape what we know about how rapid

re-housing programs are implemented and

to considerations for the proper role of rapid

re-housing programs in a communitywide

response to homelessness.

Katherine M. O’Regan

Assistant Secretary for Policy Development &

Research

Department of Housing and Urban Development

v

PART I: HOW THEY WORKED—PROCESS EVALUATION

Contents

Executive Summary

...................................................................................................................................... ix

How Do RRHD Programs Fit Into Their Communities? ...................................................................... ix

How Do RRHD Programs Identify Appropriate Participants? .............................................................. x

What Housing and Services Do the RRHD Programs Deliver? .........................................................xiii

Conclusions ................................................................................................................................................ xiv

Chapter 1: Introduction

................................................................................................................................. 1

Background ...........................................................................................................................................................1

The Rapid Re-housing for Homeless Families Demonstration .....................................................................2

RRHD Design Requirements .......................................................................................................................5

The RRHD Communities .............................................................................................................................5

This Study .............................................................................................................................................................7

Research Questions .......................................................................................................................................8

Process Evaluation Data Collection ............................................................................................................9

Organization of This Report ........................................................................................................................ 9

Chapter 2: Rapid Re-housing for Homeless Families Demonstration Programs in the

Community Context

...................................................................................................................................... 11

CoC Involvement in Agency Selection ............................................................................................................ 12

Community Planning Context and History Providing Rapid Re-housing ............................................... 14

Rapid Re-housing Before the RRHD Grant .............................................................................................15

RRHD, HPRP, and How They Relate in RRHD Communities .................................................................... 17

Philosophical Approach to the RRHD ............................................................................................................ 18

What Is Rapid? ............................................................................................................................................. 19

Chapter Summary .............................................................................................................................................19

vi

RAPID RE-HOUSING FOR HOMELESS FAMILIES DEMONSTRATION PROGRAMS EVALUATION REPORT

Chapter 3: System Entry for Families

..................................................................................................... 21

How Do RRHD Communities Structure Family Intake? ............................................................................. 21

Centralized Intake—How Can We Tell? ..................................................................................................22

Primary Intake Models—Centralized or Decentralized .......................................................................22

RRHD Structures Answering the First Question—What Is Best for This Family? ...................................22

RRHD Programs Answering the Second Question—Should We Take This Family? ..............................24

Chapter Summary .............................................................................................................................................26

Chapter 4: Screening and Selection Criteria

........................................................................................ 27

The Assessment Process....................................................................................................................................27

Basic Threshold Eligibility Criteria ..........................................................................................................27

When Are Assessments Completed, and How Are Results Used? ...................................................... 28

What Characteristics Will Get Families Screened Out of Most RRHD Programs?...........................29

Additional Screening Criteria, Tools, and Procedures ..........................................................................30

How Standardized Are the Assessment Tools? ............................................................................................. 30

How Selective Are RRHD Programs When Screening Families for Eligibility? ...............................32

What Domains Do RRHD Programs Consider When Screening, and How Are They Scored? .....33

What Family Characteristics Lead To Being Accepted Into or Screened Out of RRHD? ................. 38

Rationale for More Selective Screening Criteria and Procedures ........................................................ 39

How Have RRHD Programs Changed Their Screening and Selection Criteria? ..............................40

Chapter Summary .............................................................................................................................................41

Chapter 5: Housing Assistance and Supportive Services Offered by Rapid Re-housing

for Homeless Families Demonstration Programs

............................................................................... 43

Housing ...............................................................................................................................................................43

Length of Rental Assistance ......................................................................................................................43

What Families Hear at Enrollment ...........................................................................................................45

Level of Rent Subsidy .................................................................................................................................47

Time to Housing Placement ....................................................................................................................... 48

Supportive Services ...........................................................................................................................................48

Housing Search Assistance ........................................................................................................................49

Case Management .......................................................................................................................................50

Employment .................................................................................................................................................52

Linking to Benets and Community Services ........................................................................................ 52

Chapter Summary .............................................................................................................................................53

vii

PART I: HOW THEY WORKED—PROCESS EVALUATION

Chapter 6: Conclusion

.................................................................................................................................. 55

How Do RRHD Programs Fit Within Their Communities? .................................................................55

How Does the Intake and Assessment for Rapid Re-housing Work? .................................................. 55

Who Is Served, and Who Is Not? ..............................................................................................................56

What Housing and Services Do the RRHD Programs Deliver? ...........................................................56

Future Plans .................................................................................................................................................57

Implications for Future Rapid Re-housing Program Development ..................................................... 57

References ...............................................................................................................................59

Appendix A: Rapid Re-housing for Homeless Families Demonstration Program

Case Studies

.................................................................................................................................................... 61

Anchorage, Alaska: Beyond Shelter Services ................................................................................................. 61

Austin/Travis County, Texas: The Passages Rapid Re-housing Initiative .................................................63

Boston, Massachusetts: Home Advantage Collaborative .............................................................................65

Cincinnati/Hamilton County, Ohio: Family Shelter Partnership Rapid Re-housing ..............................67

Columbus/Franklin County, Ohio: Jobs to Housing ....................................................................................69

Contra Costa County, California: Contra Costa Rapid Re-housing ...........................................................71

Dayton/Kettering/Montgomery Counties, Ohio: Rapid Re-housing Program ........................................ 73

Denver Metro, Colorado: Project Home Again ..............................................................................................75

District of Columbia: Rapid Re-housing Initiative ........................................................................................77

Kalamazoo/Portage, Michigan: Housing Resources, Inc., Rapid Re-housing Pilot .................................79

Lancaster, Pennsylvania: Lancaster County Rapid Re-housing for Families ............................................81

Madison, Wisconsin: Second Chance RRHD Program ................................................................................83

Montgomery County, Maryland: Montgomery County Rapid Re-housing Program .............................85

New Orleans/Jefferson Parish, Louisiana: Rapid Re-housing for Families ..............................................87

Ohio Balance of State: Ohio Balance of State Rapid Re-housing Grant Program ..................................... 89

Orlando, Florida: Housing Now ......................................................................................................................91

Overland Park/Shawnee/Johnson County, Kansas: Housing for Homeless ............................................93

Phoenix/Mesa/Maricopa County, Arizona: Next Step Housing ................................................................95

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Community Human Services Rapid Re-housing for Families .....................97

Portland/Gresham/Multnomah County, Oregon: Opening Doors ...........................................................99

San Francisco, California: Housing Access Project .....................................................................................101

Trenton/Mercer County, New Jersey: Housing NOW ................................................................................103

Washington Balance of State: Northwest Rapid Re-housing Partnership ...............................................105

Appendix B: Arizona Family Self-Sufficiency Matrix

....................................................................... 107

Appendix C: Family Vignettes

.................................................................................................................. 111

viii

RAPID RE-HOUSING FOR HOMELESS FAMILIES DEMONSTRATION PROGRAMS EVALUATION REPORT

ix

PART I: HOW THEY WORKED—PROCESS EVALUATION

Executive

Summary

Rapid re-housing is a homeless assistance

strategy that provides homeless families with

immediate, temporary assistance to help them

return to permanent housing and to promote

their housing and economic stability. This ap-

proach has been growing in popularity for 10

years. In 2007, in response to the growing em-

phasis on rapid re-housing, the U.S. Congress

appropriated $23.75 million for the Rapid Re-

housing for Homeless Families Demonstration

(RRHD) program. As part of its 2008 competi-

tive application for McKinney-Vento Homeless

Assistance Act funding, the U.S. Department

of Housing and Urban Development (HUD)

awarded RRHD grants to 23 communities to

serve homeless families with moderate barriers

to housing.

Along with appropriating the RRHD funding,

Congress mandated an evaluation of RRHD

activities and their effect on families. This report

describes the ndings of that evaluation’s rst

phase, a process evaluation examining how

programs were designed and how they are being

implemented. The ndings were distilled from

information gained during site visits or intensive

phone interviews with all 23 RRHD grantees

conducted between February and May 2011.

1

Results are organized to answer the following

research questions established by HUD.

How Do RRHD Programs Fit Into Their

Communities?

HUD expected communities to design their

RRHD programs to complement other available

resources and reect community conditions.

RRHD programs fullled this expectation in

numerous ways.

• Each successful RRHD application evolved

through an analytic process within local Con -

tinuums of Care (CoCs), which were involved

either as RRHD grantees themselves or as

the entity that selected grantees from among

possible agencies.

• CoCs chose agencies to become RRHD grant-

ees that had signicant experience working

with homeless families, often through previous

rapid re-housing programs. Twelve RRHD

agencies and their communities had rapid re-

housing programs in place before applying

for RRHD grants, two others had programs

that closely resembled rapid re-housing, and

several had committed themselves to rapid

re-housing philosophically and were actively

seeking funding sources when the RRHD pro -

gram was announced. The existence of rapid

re-housing before RRHD informed each com -

munity’s program design.

• Community context strongly inuenced

RRHD program design and client selection.

1 This process evaluation report is accompanied by a report on the

results of an outcomes evaluation examining whether receipt of RRHD

services helped families increase their housing and income stability by

the end of formal assistance and by 12 months after assistance ends.

x

RAPID RE-HOUSING FOR HOMELESS FAMILIES DEMONSTRATION PROGRAMS EVALUATION REPORT

• Communities that had alternative interven-

tions available for families tended to be highly

focused on the families they enrolled in RRHD,

because they had the resources to send fam -

ilies to other programs more appropriate

to their circumstances, needs, and barriers.

Communities with fewer or no other options

tended to accept families with a broader

need prole into their RRHD program if the

program had sufcient capacity.

• Communities that had both RRHD and a dif-

ferent rapid re-housing option that included

coverage for education and training sent

families to the latter if a member of the fam-

ily wanted to enroll or was already enrolled

in a course of study that would enhance the

family’s progress toward self-sufciency.

• Communities with very high housing costs

tended to target families with minimal rather

than moderate barriers, reasoning that only

families with strong skills and solid work

histories would be able to reach self-sufciency

in the period of time that the RRHD program

could help them with rental assistance. Grant -

ees in communities with a more mixed hous-

ing picture were more exible, with the most

inclusive programs accepting about 80 percent

of families coming through emergency shelter

into their RRHD programs.

Implication: Rapid re-housing programs should

be designed to reect the local context, including

the availability and focus of existing homeless

prevention and assistance programs, local hous -

ing costs, and other homeless system goals and

strategies.

How Do RRHD Programs Identify

Appropriate Participants?

This research question has two components:

(1) “How do families learn about and approach

an RRHD program, and (2) How are families

selected to receive services from the RRHD

program?”

System Entry for Families

Prospective RRHD families learn about the pro -

gram in numerous ways, including being referred

by emergency shelter providers, hearing about

it from friends, or calling 2-1-1 or another cen -

tralized information and referral service. How-

ever families hear about the program, RRHD

communities are generally divided into two

groups, depending on whether the communities

have a centralized system of intake and referral

among homeless programs or operate in decen-

tralized structure.

1. Centralized intake structures provide a single

point of entry into the homeless system that is

organized to answer, “Of the several services

available, what mix of housing and service

assistance is best for this family?” Approxi-

mately one-third of the RRHD sites have

tightly organized central intake structures,

and four others have a modied form of

central intake.

Communities with centralized intake gener-

ally place a range of resources at the disposal

of the intake agency. The agency’s job is to

learn enough about a family to determine

what it needs and to decide which of the

program and resource types available best

suits the family’s needs. If the answer is

rapid re-housing, the family is offered rapid

re-housing; otherwise, the family is referred

elsewhere.

In communities with centralized intake,

the screening and much of the assessment

process occur immediately upon entry to the

homeless system and tend to be intensive

and deliberately tied to making enrollment

determinations across multiple housing and

service options. The options usually include

diversion from shelter (that is, homelessness

prevention) and shelter or other homeless

assistance programs.

2. Noncentralized intake structures rely on in-

dividual programs to screen families and, at

intake, each answers, “Should we accept this

xi

PART I: HOW THEY WORKED—PROCESS EVALUATION

family into our rapid re-housing program?”

Eleven communities use a noncentralized

system where a family approaches the RRHD

provider agency directly and the agency

makes a decision about whether it thinks the

family is right for its program. In these com-

munities, screening generally occurs after a

family enters shelter (that is, diversion is not

an option for most families). Once a family

has entered shelter, shelter caseworkers make

decisions about where to refer families, often

without thorough knowledge of the program

availability and eligibility criteria and certainly

without control over the outcome of the

referral.

Implication: Based on information gathered

for this evaluation, a decentralized approach

seems to be less efcient and possibly less

effective than a centralized model, unless it is

strongly coordinated across intake points.

Screening, Assessment, and Family Selection

Into RRHD Programs

All RRHD programs had to work with the eligi -

bility criteria HUD set for the RRHD program,

which were that families must (1) include at

least one child; (2) be literally homeless; (3) have

at least one moderate barrier to housing; and

(4) be able to independently sustain themselves,

with or without a subsidy, after a short period

of time. The rst two criteria are relatively clear;

RRHD programs differ substantially, however,

in what they consider a moderate barrier and

what they perceive it will take to be able to sus-

tain one’s family independently.

• HUD dened moderate barriers, but RRHD

programs varied in how they interpreted and

applied the denitions. For example, some

programs rated “having a low-paying or part-

time job” as a moderate barrier, while for

others, only “long-term unemployment” would

have been considered a moderate barrier.

• In addition to differences in interpreting

different barriers, programs varied greatly

in how many barriers they considered in

making the decision to accept a family into

the program. Some focused only on informa-

tion related to the major areas in which they

expected to make a difference with housing

access or stability, of which housing, employ-

ment, and income were the top three. Other

programs included as many as 18 or 20 do -

mains in their consideration of a family’s

appropriateness for their services and gave

equal consideration to housing, employment,

mental health, public benet use, and involve -

ment in community activities such as the

Parent Teacher Association.

• Programs focused strictly on housing-related

domains tended to accept families with higher

barriers, in part because they did not penalize

families for barriers that would not directly

affect housing placement and in part because

they had developed targeted strategies to

mitigate signicant barriers to re-housing.

• The eligibility criterion that families must

have the ability to sustain themselves after

assistance was also interpreted differently.

Despite HUD’s explicit inclusion of the re-

ceipt of a rent subsidy as one way to be able

to sustain oneself in housing, several RRHD

programs thought of sustainability only in

the sense of what a family could do for itself.

In some communities, this interpretation

reected the scarcity of available subsidies,

but even in communities with available sub-

sidies, some programs screened out families

who they deemed unlikely to be able to pay

their full rent unassisted after program com-

pletion.

• Differences among RRHD programs often

reect different philosophies about rapid

re-housing and the characteristics of families

who should be served by these programs, the

range of other housing and service options

within the local community, the cost of hous -

ing relative to the length of assistance offered,

and the feasibility of families becoming eco -

nomically self-sufcient within that timeframe.

xii

RAPID RE-HOUSING FOR HOMELESS FAMILIES DEMONSTRATION PROGRAMS EVALUATION REPORT

• Some programs use highly selective criteria,

based on beliefs that only those families with

high levels of self-sufciency and few barriers

will be able to maintain permanent housing

with time-limited assistance and that other

families will benet from other types of as-

sistance in shelters, transitional housing

programs, or longer-term interventions—

whether or not the local housing and home-

less assistance system has the capacity to

offer enough assistance to respond to those

needs. In some cases, programs that use

highly selective criteria were unable to nd

enough homeless families who qualify to

participate in the program.

• Other programs have adapted their selection

criteria as they have gained experience with

the rapid re-housing model, using more se-

lective criteria when offering only short-term

rental assistance. These programs balance

their criteria for short-term assistance with

much less selective, more exible criteria

when they can offer more months of housing

assistance combined with services to address

more substantial housing barriers. In some

cases, they may be able to offer access to

permanent affordable housing or long-term

rental assistance from other sources as a

safety net for families who need more help.

• Three family vignettes were used to reect

selectivity among the 23 RRHD programs.

The families in these vignettes varied in the

number and types of barriers to housing they

had. Research staff judged that 10 programs

would accept all three families, 8 programs

would accept one or two of the vignette fam -

ilies, and 5 programs would reject at least

two and probably all three families.

• Many programs’ enrollment policies demon-

strated a belief in the interrelationship of family

barriers and the length of rapid re-housing

assistance. The longer the term of assistance

they offered, the more likely they were to

accept families with more barriers. Programs

that had elected to apply only for short-term

assistance felt they could not in good con-

science accept multiple-barrier families, because

they believed the families would fail unless

they had more time to resolve their issues.

Implication: No simple recommendations of

best practices are likely to emerge from the

array of assessment tools and procedures used

by RRHD programs. An important nding is

that the same tool can be used in many differ-

ent ways, with quite different consequences

for families requesting services. Selection of a

specic tool and decisions about how to use it

must be considered separately. Communities or

agencies will need to consider their resources,

housing and employment market conditions,

alternative interventions available, program size

and length of intervention, and intake structures

before selecting a tool and crafting a strategy

for use.

How Rapid Is Rapid Re-housing?

Some RRHD programs aimed to move people

from shelter into housing in fewer than 30

days. These programs tended to have been

created with the belief that shelters are bad for

families, that rapid should be rapid, and that

families could only begin to stabilize after they

moved back into housing. Other programs

did not even consider families for re-housing

resources until they had been in shelter for

4 months or more, operating from the belief

that families needed time in shelter to catch

their breath, recover from the immediate crisis

that precipitated their homelessness, and get

their act together. Further, rapidity and family

barrier levels did not vary in tandem in RRHD

programs. Some programs took families with

considerable barriers and moved them out of

shelter within 30 days, others only accepted

families with minimal barriers and considered

4 months in shelter reasonable, and still others

fell in between these extremes.

xiii

PART I: HOW THEY WORKED—PROCESS EVALUATION

What Housing and Services Do the

RRHD Programs Deliver?

RRHD programs provide temporary rental sub -

sidies paired with case management, housing

search assistance, direct supportive services,

and linkages to community-based services. The

23 RRHD programs vary in the length of rent

assistance they provide to families, the amount

of the subsidies, and the types of support ser -

vices a family receives. The package of assistance

offered by programs directly reects their deci-

sions about whom to serve and vice versa.

Length and Level of Rental Assistance

The goal of the RRHD is to re-house families in

permanent housing (subsidized or unsubsidized)

that they can sustain on their own after they

cease to receive the program’s rental assistance.

Communities could apply for funding to provide

short-term housing assistance (3 to 6 months),

long-term housing assistance (12 to 15 months),

or both, based on expected family need. Five

CoCs offer short-term rental assistance, and

13 CoCs offer long-term rental assistance. The

remaining 5 CoCs offer both, determining the

length of assistance awarded to each family dur -

ing the assessment. Some programs offering

short-term assistance indicated that it has been

difcult to nd families with moderate barriers

that could successfully sustain housing within

6 months. Most communities (16) told partici-

pants the length of assistance they would receive

upon enrollment. Seven programs used an

“incremental approach,” where a family was

guaranteed a rst increment of rental assistance

(usually 3 months), followed by some regular

recertication or progress review. Most often,

the length of the rental assistance is based on

the progress made on self-sufciency plans and

compliance with program requirements.

RRHD programs had some exibility in how

they provided rental assistance to families. The

level of subsidy provided generally fell into

three categories: a at dollar amount, a pro-

portion of income monitored on a monthly or

quarterly basis, and a graduated rent subsidy

that decreases over the duration of the assistance

(and whereby the family is responsible for rent

contributions that increase over time and the

family is expected to pay the entire rent at the

end of the program). Most programs made ad -

justments or exceptions to requirements for the

tenant portion of rent if the family was working

to pay outstanding debts or had an unexpected

crisis.

Supportive Services

RRHD programs provide a variety of supportive

services. All programs provide some type of

housing search assistance or placement assist-

ance to link families with housing units that will

be affordable to them at the conclusion of the

program. Some programs were passive in the

provision of these services, pointing families to

newspaper or online advertisements or provid -

ing a list of postings or landlords that the families

could contact. Other programs offered more

direct assistance, driving clients to available

units or to meet with landlords. Many RRHD

programs operate out of agencies that have

established relationships with a large pool of

landlords in the community willing to rent to

program participants. Five programs have a

housing specialist on staff who works directly

with families to help them nd a unit and set

up the lease. Three programs offer housing in

master-leased units or on their own property,

simplifying the upfront housing placement pro -

cess for RRHD but often requiring the family to

move at the end of the program.

All RRHD programs provide case management

to families and require families to work with a

case manager at enrollment to set up housing

and self-sufciency plans, identify service needs,

and set a family budget. Progress toward these

plans generally is evaluated on a weekly or

monthly basis but sometimes may be reviewed

only quarterly at recertication. These meetings

may be conducted by phone, in the ofce, or

in the home, though most RRHD programs re-

quire at least monthly inperson visits. In most

xiv

RAPID RE-HOUSING FOR HOMELESS FAMILIES DEMONSTRATION PROGRAMS EVALUATION REPORT

cases, RRHD programs offer case management

after the conclusion of the program, and six

RRHD programs identied a formal followup

process to check on families 6 or 12 months

after program exit.

Most programs provide support services in

addition to housing search and case manage-

ment. Several RRHD programs provide some

employment assistance either through job and

career development, coordinating and linking

with Temporary Assistance for Needy Families

and workforce development agencies, or the

direct provision of employment assistance of-

fered by the agency. Linkages with mainstream

benets were a requirement of the grant, and

all RRHD providers had arrangements with

mainstream agencies to some extent. Some com -

munities had formal arrangements, established

through memoranda of understanding, to help

streamline benet application procedures; a few

programs actually out-stationed staff in ofces

within the county human services department.

For others, case managers had established rela-

tionships to help facilitate benet application

procedures.

Conclusions

RRHD is, rst and foremost, a demonstration

program. Congress provided and HUD allocated

resources to learn what communities would do

if they had funding for rapid re-housing. The

process component of this evaluation provides

evidence of what communities did (the outcome

component of the evaluation, which looked at

whether the RRHD interventions made a diffe r-

ence for families). What conclusions can we

draw from our observations of how RRHD

programs were designed and how they have

been implemented?

First, it is clear that community context affects

each aspect of program design and implementa -

tion. The research team observed a great variety

of RRHD program designs, family selection

criteria, and services and supports across RRHD

communities and this report seeks to articulate

the ways that community context shaped each

RRHD program.

Second, the culture and past experiences of the

agencies administering RRHD affect program

design. Agencies accustomed to having families in

shelter for 4 to 6 months, while the caseworkers

assist families with various issues, continue to

do so for most families, even when they have

funding intended to help move families out of

shelter quickly. For these programs, rapid often

meant that families could leave shelter in a few

months instead of staying much longer. Agencies

expecting families to move out quickly design

their RRHD programs with those expectations

intact and often move families out of shelter in

less than a month. Further, agencies holding

the attitude that “we have not seen a family

we cannot work with” operate different RRHD

programs than those of agencies that look for

substantial demonstrations of family motivation

before they accept a household into their program.

Many different program designs are possible

within the rapid re-housing framework; we

have seen that the designs all “work,” to some

degree, in the sense that they can be implemented

and they serve homeless families. The varieties

of program offerings, coupled with the extreme

range of families and family barriers considered

acceptable by different RRHD programs, pro-

vide us some strong contrasts to work with when

we look at family outcomes during the next

phase of this evaluation. The critical questions

we will be addressing in the outcomes phase

include: “Do the RRHD families with greater bar -

riers do as well as those with fewer barriers?” And,

if the answer to this rst question is yes, then—

“What is it about their RRHD programs (and possibly

also their communities) that helps them work through

their barriers and reach a situation of housing

stability?”

1

PART I: HOW THEY WORKED—PROCESS EVALUATION

CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION

Chapter 1

Introduction

Rapid re-housing for homeless families is both

a philosophy and a homeless assistance inter-

vention designed to quickly move homeless

families from literal homelessness back into

permanent housing. From a philosophical per-

spective, rapid re-housing tries to minimize the

time that families spend homeless, premised

on the belief that time in shelter harms families

and children and that most families do not

need a long period of preparation before they

can succeed in housing. Rapid re-housing inter-

ventions generally offer families a package of

temporary assistance that may include housing

placement search assistance, one-time nancial

assistance to offset move-in costs, case manage-

ment, housing stabilization services, ongoing

nancial assistance to bridge the gap between

family income and housing cost, and other

supportive services or linkages to community

resources to help families develop the capacity

to keep their housing in the future. The rapid

re-housing model is usually thought of as most

appropriate for families with moderate barriers

to getting and keeping housing, such as barri-

ers that are mostly economic in nature and of

relatively recent origin. This report examines

the 23 programs funded by the U.S. Depart-

ment of Urban Development (HUD) as part

of a national Rapid Re-housing for Homeless

Families Demonstration (RRHD) program. This

component of the research effort was intended

to identify essential dimensions of rapid re-

housing programs and the community contexts

that affect program design and operations.

Lessons learned are expected to guide develop-

ment of similar programs in the future.

This chapter briey describes the history of the

rapid re-housing program model, the RRHD

initiative, the programs funded by it, and the

RRHD evaluation and research questions.

Background

Rapid re-housing for homeless families has a

history going back more than a decade but has

only recently come into greater prominence as

a best practice. Two communities—Columbus/

Franklin County, Ohio, and Hennepin County,

Minnesota—are known as the pioneers of rapid

re-housing for families. Hennepin County be-

gan shifting to a rapid re-housing approach in

2000 and 2001; Columbus used the approach

even earlier but had a gap of some years be -

cause of funding changes. In both communities,

rapid re-housing is part of a larger, carefully

articulated strategy built on the premise that

extended shelter stays do not, by denition,

end homelessness (that is, the families are still

in shelter, homeless) and that shelter stays of

any length (but especially long ones) are not

good for children.

2

Also, for communities that

pay for shelter with public funds, long shelter

stays are costly and do not demonstrably

reduce homelessness.

Several aspects of these pioneering Continuum

of Care (CoC) homeless assistance networks

contribute to their ability to prevent families

from losing their housing and to move families

quickly out of shelter if homelessness cannot

be prevented, as seen in the following specic

aspects:

3

• Strategists in both communities considered

it essential that the same system coordinate

families’ access to prevention, emergency

2 The evidence that homelessness specifically harms children is weak;

homeless and poor housed children do not differ on most dimensions

that research has measured (chapter 5 in Dennis, Locke, and Khad-

durhi, 2007). The evidence that extreme poverty harms children is

strong, however, and homeless children are extremely poor, as are the

housed children with whom they are compared in most recent studies.

Children in families served by emergency shelters have been observed

showing signs of great stress; program staff work to help the children

they can—those in their care. Rapid re-housing is a way to reduce time

in shelter to a minimum, thus removing at least the stress of homeless-

ness from parents and children. Supportive services offered during the

transition to housing and for several months after families regain hous-

ing are designed to help families with budgeting and organizational

skills that could lead to improved employment and earnings opportuni-

ties, parenting, and other issues that could help stabilize their lives and

reduce some of the stresses associated with extreme poverty.

3 See Burt, Pearson, and Montgomery (2005) and appendix A for an

entire description of Hennepin County’s prevention–rapid exit system.

2

RAPID RE-HOUSING FOR HOMELESS FAMILIES DEMONSTRATION PROGRAMS EVALUATION REPORT

CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION

shelter, and some transitional housing

services. This level of coordination ideally

would include all transitional housing and

other services, but neither community has

yet achieved this level of control.

• Families receive assistance in relation to their

level of need; a comprehensive assessment

process following initial screening determines

whether the family will receive help to remain

in housing or an offer of emergency shelter.

The latter in all cases leads to programs work -

ing with the family to help it move out of

shelter within a few weeks. Families assessed

as needing more long-term solutions to their

housing situation, such as permanent sup-

portive housing, are referred to relevant

programs if they are available.

• A collaborative network of nonprot agencies

provides the actual prevention and rapid exit

services. Emergency shelter and rapid re-

housing efforts are separated; shelter provid-

ers supply shelter, while contracts with other

agencies hand over the responsibility for and

provide the families resources to help them

leave the shelter.

The credibility of rapid re-housing for families

was rst demonstrated through local data.

An essential component of the two CoCs that

pioneered rapid re-housing has been custom-

designed data systems that link all prevention

and rapid exit agencies to grant providers access

to real-time family service histories dating back

10 to 15 years. Not only do these data systems

provide staff working with families the infor-

mation they need, they also provide system

administrators with data that can document the

effectiveness of prevention and rapid re-housing

interventions. At the local level, this documen-

tation has led to continued and sometimes

expanded funding for the approach.

Other evidence suggests that housing availability,

subsidies, and resources are the factors that best

predict how long families will stay in shelter.

4

Personal characteristics such as age, race, edu-

cation, employment, health, and mental health

do not have this predictive power. If housing

is relatively inexpensive or short or long term,

or permanent rent subsidies are available and

communities are organized to link families and

landlords, families leave shelter faster than if

housing is expensive, no landlord linkages exist,

and the subsidy waitlists are years long. These

ndings support the value of providing families

with upfront move-in costs and a few months

of rental assistance to keep their stay in shelter

short. Dissemination of evidence about rapid

re-housing has catapulted this approach into

the national spotlight.

The Rapid Re-housing for Homeless

Families Demonstration

In 2007, the U.S. Congress appropriated $23.75

million to fund the RRHD program to support

pilot rapid re-housing programs in communi-

ties throughout the country. Funds were also

included to evaluate the programs and deter-

mine their impact.

HUD sought proposals for demonstration pro -

grams through the 2008 application process for

McKinney-Vento Act funds. To be eligible for

funding, applicants had to demonstrate that

they had a central intake process in place within

the community to identify and screen all home -

less families and that a standardized tool would

be used to systematically assess families for

ap propriateness for the RRHD program as com -

pared with other community interventions.

RRHD programs were supposed to be designed

to serve families identied as having at least

one moderate barrier to housing, based on the

assumption that families with low barriers to

housing would not need the RRHD assistance

to regain housing and that those with signicant

barriers would need more assistance than could

be provided through the RRHD program.

RRHD program eligibility requirements are

described more fully in the following section.

4 See Weinreb, Rog, and Henderson (2010) for a recent analysis and

summary of past research, which is consistent with these findings.

3

PART I: HOW THEY WORKED—PROCESS EVALUATION

CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION

Applicants could ask for support to provide

short-term rental assistance of 3 to 6 months,

medium-term rental assistance of 12 to 15 months,

or both levels if they planned to serve families

with different intensities of moderate barriers to

housing. Supportive services eligible under the

program were limited to housing placement, case

management, legal assistance, literacy training,

job training, mental-health services, childcare

services, and substance-abuse services. To aug-

ment these supports, agencies running RRHD

programs could partner with other agencies or

leverage other funding sources to supplement

and round out the services offered to families

through RRHD.

HUD received 212 applications, totaling $122

million in requests, from the more than 400

CoCs eligible to submit as part of the annual

competitive request for HUD funding for home -

less programs. Programs were removed from

the competition before scoring if the applicant

(1) submitted more than one RRHD application;

(2) failed the initial eligibility review through

failure to attach an appropriate assessment

tool, proposing to serve ineligible households

(for example, those without dependent children

or households not coming from streets or shelter),

or otherwise not meeting basic RRHD criteria;

(3) submitted a program without a leasing bud -

get; or (4) failed to pass the Supportive Housing

Program grant review threshold.

Agencies in 23 CoCs were awarded the 3-year

RRHD grants; however, well before HUD

nished executing the grant agreements, rapid

re-housing became part of newly elected Presi -

dent Obama’s American Recovery and Revital -

ization Act through its Homelessness Preven-

tion and Rapid Re-Housing Program (HPRP)

(P.L. 111-5, February 2009). HPRP sent $1.5 bil -

lion to hundreds of state and local jurisdictions—

three to four times more funding than any of

these jurisdictions had ever had for either home -

lessness prevention or rapid re-housing. The

rapid re-housing idea might not have been

mature, but HPRP put it squarely on the nation’s

agenda. Each community that won an RRHD

grant also received HPRP funding, and most

devoted some of these new resources to rapid

re-housing. In this changed environment, RRHD

communities had not only the rapid re-housing

funds that came with their new grant but also

HPRP funds for a similar purpose. Each pro-

gram had its own regulations, however, and

the administrative challenges were signicant.

Key program features of the RRHD program

and the HPRP are summarized in exhibit 1.1.

Further complicating matters, HPRP, and the

infusion of resources it provided, would end by

September 2012 because of statutory expenditure

deadlines. By contrast, the RRHD program may

continue as part of a community’s homeless

assistance system if the grantee elects to renew

the funding.

5

Thus, although communities had

to ramp up quickly to design systems to deliver

both HPRP and RRHD, now RRHD sites must

determine how to continue to operate their

programs in a changing environment.

5 RRHD grants were not originally intended to be renewable because

they were appropriated as a demonstration program; however, in the

2009 appropriation, language was provided to clarify that they are

renewable under the annual CoC competition.

4

RAPID RE-HOUSING FOR HOMELESS FAMILIES DEMONSTRATION PROGRAMS EVALUATION REPORT

CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION

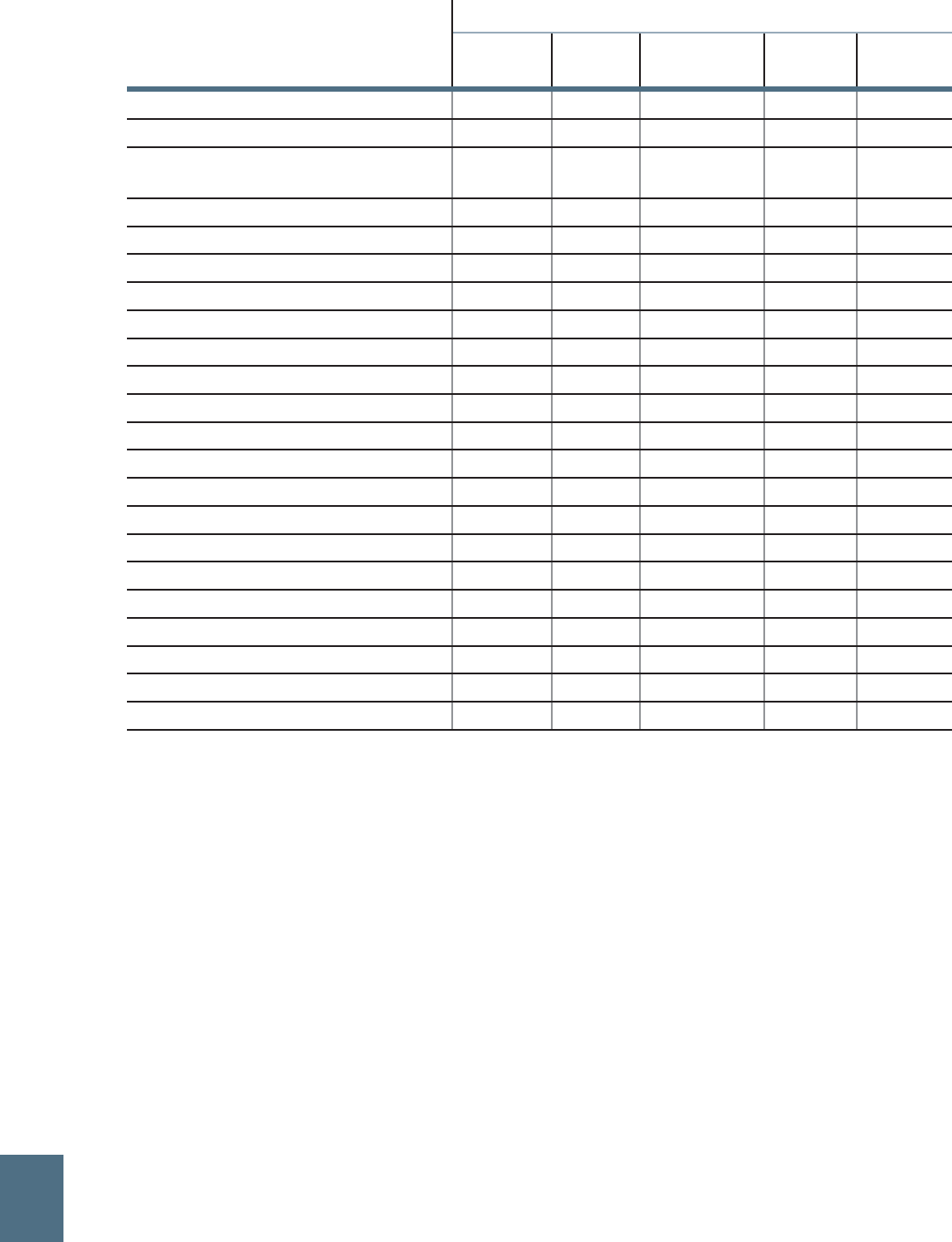

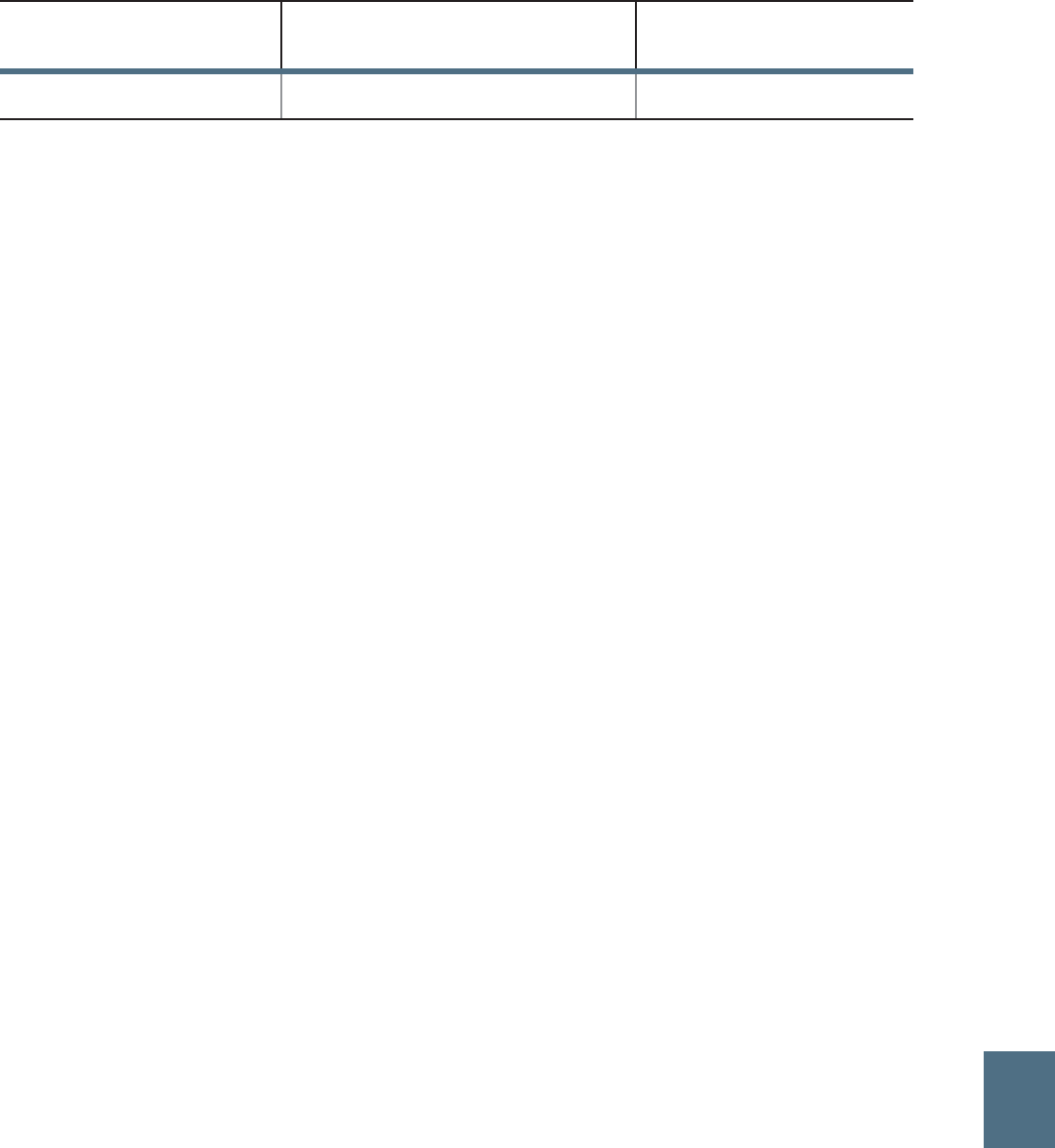

Exhibit 1.1: Key Program Features of the RRHD Program and the HPRP

Key Features RRHD Program HPRP

Eligible participants Homeless families with children who

have been living on the streets or in

shelter for at least 7 days and have

at least one moderate barrier to

housing.

Homeless individuals or families who

meet the homeless definition. (Preven-

tion assistance can also be funded from

HPRP.)

Eligible housing activities Financial assistance:

• Short-term rental assistance of

3 to 6 months.

• Medium-term rental assistance of

12 to 15 months.

• Both levels, to serve two levels of

families with moderate barriers to

housing.

Financial assistance:

• Rental assistance, up to 18 months,

including arrears.

• Security and utility deposits.

• Moving cost assistance.

• Motel and hotel vouchers.

Eligible service activities Supportive services:

• Housing placement.

• Case management.

• Legal assistance.

• Literacy training.

• Job training.

• Mental health services.

• Childcare services.

• Substance abuse services.

Housing relocation and stabilization

services:

• Housing search and placement.

• Outreach and engagement.

• Case management.

• Legal services.

• Credit repair.

Recertification requirements Grantees can commit to providing as-

sistance for a 3- to 6-month period or

for 12 to 15 months. SHP regulations

require an annual rent calculation.

Participants must be recertified for as-

sistance every 3 months, and assistance

can only be guaranteed in these 3-month

increments.

System design requirements Community must have central

intake or coordinated intake system

whereby all homeless families in

the community can be systemati-

cally screened for assistance using a

standardized tool.

None specified by the HPRP Notice, al-

though grantees had to amend their con-

solidated plans to specify the estimated

amount that would be used for prevention

versus rapid re-housing.

Period available 3-year renewable grants, beginning

as early as August 2009.

Nonrenewable grants, beginning July

2009. 60% of funds had to be expended

by September 30, 2011, and all funds by

September 30, 2012.

HPRP = Homelessness Prevention and Rapid Re-Housing Program. RRHD = Rapid Re-housing for Homeless Families

Demonstration.

5

PART I: HOW THEY WORKED—PROCESS EVALUATION

CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION

RRHD Design Requirements

In the announcement of RRHD funding avail-

ability, HUD identied specic criteria against

which the Department would judge proposals.

These criteria were based on the most cur-

rent evidence pertaining to specic program

elements that seemed to be important to the

functioning of the few examples of successful

rapid re-housing approaches that existed when

the announcement was written. These criteria

included specications detailing which families

could be served and certain structural charac-

teristics of CoCs in which the RRHD program

would be located.

Eligibility

To be eligible for RRHD programs, families had

to have been homeless for at least 7 days, using

HUD’s denition of homelessness. In practice,

this requirement means that they must be stay-

ing in an emergency shelter or be sleeping in

a place not meant for habitation, such as a car,

unconverted garage, abandoned building, or a

similar venue. Families were also supposed to

have at least one moderate barrier to housing

stability, which the grant announcement listed as

temporary nancial strain, inadequate employ -

ment, inadequate childcare, a head of household

with low-level education or low command of

English, legal problems, health diagnosis, history

of substance abuse (without active use), poor

rental history, and poor credit history.

Community Structures and Practices

HUD also described several structures and prac -

tices that characterized the pioneering rapid

re-housing communities and that it wanted to

see in communities that received RRHD grants.

One such structure was a central or uniform

intake process through which homeless and at-

risk families would be screened, assessed, and

offered participation in one or more programs

that t their needs. An important practice that

HUD wanted to see was communitywide use of

a common screening and assessment tool that

would provide the information needed to allo-

cate housing and supportive service resources

to families in the array and intensity needed to

help them. HUD permitted communities to

structure their RRHD program around different

lengths of housing provision and other assistance,

specifying that they had to choose short-term

(3 to 6 months) assistance, long-term (12 to 15

months) assistance, or both levels. Recognizing

that landlords are a vital part of the commun-

ity without whose active cooperation rapid

re-housing programs cannot work, HUD also

placed a high priority on the existence of strong

associations between the agencies proposed

as RRHD providers and local landlords, rang-

ing from long-term personal relationships to

formal websites maintaining up-to-date lists of

available apartments and landlords willing to

accept homeless families.

The RRHD Communities

The RRHD Notice of Funding Availability

specied core design features and basic require -

ments for the RRHD programs but also gave

applicants the latitude to design their RRHD

proposals to meet their local needs and the con -

text of their local system and partners. Some

grants embraced the principles in the Notice,

and others adapted them. As a result, the 23

RRHD programs vary considerably. These vari-

ations enable HUD to learn about how rapid

re-housing efforts function in different environ-

ments; however, the differences between pro-

grams and their communities will make it more

challenging to draw clear conclusions about

the impact of rapid re-housing in later phases

of this evaluation. Throughout this report, we

document the various ways in which RRHD

grantees implemented the demonstration, and

we attempt to categorize common features and

differences across the 23 sites.

Exhibit 1.2 presents some basic information

about the 23 RRHD communities. Grants ranged

from $78,300 to $2 million. The earliest date an

RRHD grant was executed was August 31, 2009,

and the earliest month in which a program

6

RAPID RE-HOUSING FOR HOMELESS FAMILIES DEMONSTRATION PROGRAMS EVALUATION REPORT

CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION

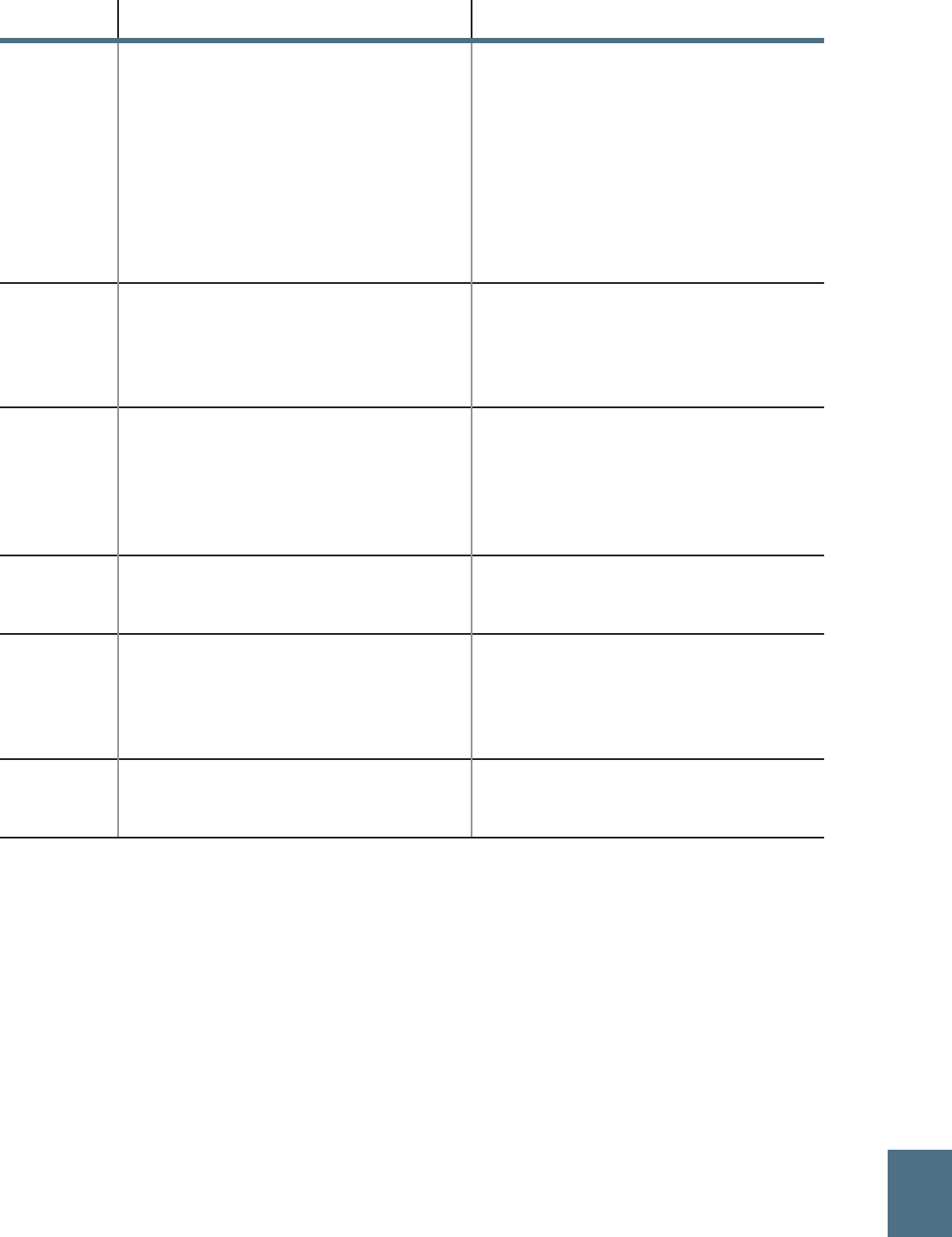

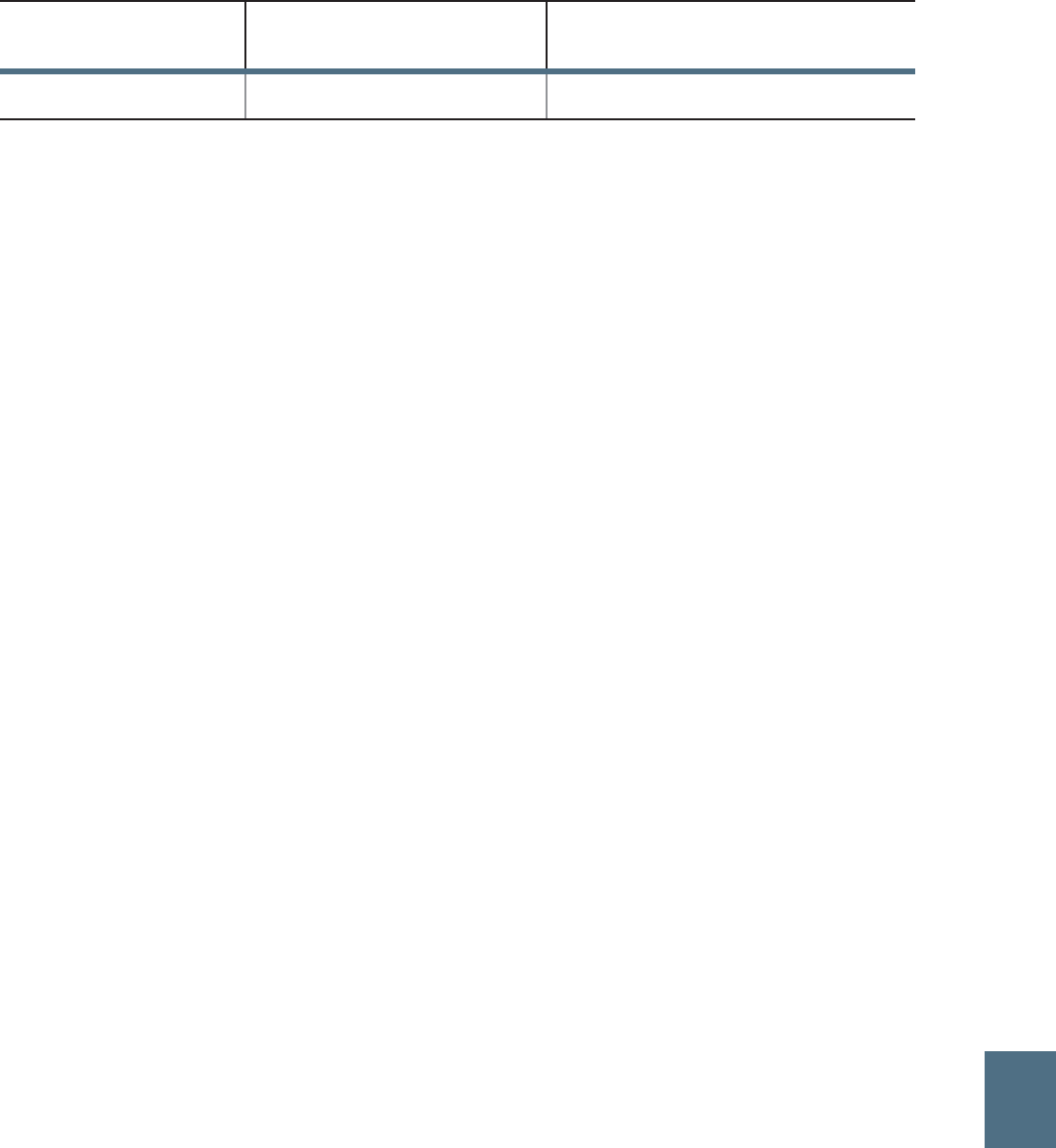

Exhibit 1.2: RRHD Program Information

Demonstration

CoC Programs

CoC

Number

Grant

Amount

Grant

Execution

Date

Month

of First

Enrollment

Length of

Assistance

Planned

Point-

in-Time

Capacity

# Exited

by 4/11

Anchorage, AK AK-500 $193,485 11/4/2009 01/2010 Short 20 11

Austin, TX TX-503 $795,540 01/20/2010 02/2010 Long 25 2

Boston, MA MA-500 $1,896,587 11/9/2009 01/2010 Long 24 6

Cincinnati, OH OH-500 $1,678,310 12/22/2009 02/2010 Long 60 11

Columbus, OH OH-503 $844,634 01/22/2010 03/2010 Short 40 28

Contra Costa County,

CA

CA-505 $510,971 07/2010 10/2010 Long 12 0

Dayton, OH OH-505 $784,700 01/15/2010 03/2010 Long 36 5

Denver, CO CO-503 $1,578,753 10/28/2009 02/2010 Short (6 mo.) 35 29

District of Columbia DC-500 $1,866,274 12/1/2009 03/2010 Long 17 0

Kalamazoo/Portage,

MI

MI-507 $232,318 10/8/2009 10/2009 Both 20–21 12

Lancaster, PA PA-510 $528,341 02/5/2010 03/2010 Short 24 1

Madison, WI WI-503 $ 247, 280 12/4/2009 12/2009 Long 6 6

Montgomery County,

MD

MD-601 $541,738 10/15/2009 04/2010 Long 7 2

New Orleans, LA LA-503 $2,000,000 06/2010 08/2010 Short 60 9

Ohio BOS OH-507 $1,999,881 12/10/2009 01/2010 Both 358 16

Orlando, FL F L- 5 0 7 $1,171,934 05/19/2010 05/2010 Long 64 4

Overland Park, KS KS-505 $78,300 09/1/2010 09/2010 Long 6 0

Phoenix, AZ AZ-502 $1,981,371 05/1/2010 05/2010 Both

(6–9 mo. target)

80 9

Pittsburgh, PA PA-600 $839,501 02/5/2010 03/2010 Both 20 6

Portland, OR OR-501 $1,085,075 08/31/2009 10/2009 Long 40 1

San Francisco, CA CA-501 $2,000,000 05/2010 07/2010 Both 33 0

Trenton, NJ NJ-514 $387,220 12/28/2009 02/2010 Long 9

a

0

Washington BOS WA-501 $656,639 10/6/2009 01/2010 Long 50 19

BOS = Balance of State. CoC = Continuum of Care. RRHD = Rapid Re-housing for Homeless Families Demonstration.

a

These 9 slots are combined with about 40 slots supported by other rapid re-housing resources, and all are treated

identically.

enrolled a family was October 2009.

6

The latest

date for execution was September 2010, and the

latest month a program enrolled its rst family

was October 2010. Five programs offer only

short-term rental assistance, 13 programs offer

only long-term rental assistance, and 5 programs

offer both. Programs range in the number of

families they can serve at one time from 6 to

358 and in the number of families they expect

to serve during the entire 3 years of their grant

from 18 to 1,000.

6 One program enrolled a few families directly after it learned it had been

awarded a grant in August 2009, but then it stopped enrollment until

the grant was actually executed.

7

PART I: HOW THEY WORKED—PROCESS EVALUATION

CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION

As of the end of March 2011, the RRHD program

had served a total of 815 families. Of these

fam ilies, 235 had been served with assistance

intended to be short term (3 to 6 months), and

580 families had been served with assistance

intended to be long term (12 to 15 months).

As of April 2011, 25 percent of families (207

families) had exited the program. Five RRHD

programs had not yet exited any families by

this date. More than one-half (54 percent) of the

families who exited had received short-term as-

sistance. In some cases, the exits were unplan-

ned or sooner than planned, because the RRHD

program was not a good t for families’ needs.

In other cases, families had participated in

RRHD programs for the entire period offered

and had formally exited as planned. Several

RRHD programs that offered both short- and

long-term assistance noted that families origin -

ally earmarked for short-term assistance required

help for longer than anticipated to achieve

housing stability, so fewer families had exited

by April 2011 than were expected. More statis-

tics on actual program usage will be provided

in the outcomes evaluation.

This Study

The RRHD grant programs are part of a nation-

wide evaluation to assess what types of impact

the programs have on the families they serve.

In October 2009, HUD awarded Abt Associates

Inc. (Abt) a contract to conduct a two-stage

evaluation. This report presents the results of

the rst stage, which has focused on learning

how each RRHD program operates, which fam -

ilies it serves, what housing and service options

it offers to families, how it ts into its community,

how it works with prevention and other rapid

re-housing programs in the community—if

they exist—and how the community is thinking

about the future. This stage of the evaluation

offers the rst opportunity to understand rapid

re-housing program design and functioning in

communities across the country that vary in

size and complexity, housing and employment

environment, and community organization and

generosity. The results of this implementation/

process part of the evaluation may help guide

communities, and HUD, as they decide how to

use the resources made available by the Home -

less Emergency Assistance and Rapid Transition

to Housing Act (P.L. 111-22), passed in May 2009,

that identies rapid re-housing as an eligible

activity under both the new McKinney-Vento

Emergency Solutions Grant and the CoC Program.

The second phase of this study focuses on the

outcomes of RRHD participation for families.

To conduct the outcomes study, the research

team interviewed families by phone 12 months

after the rental assistance they received through

RRHD ended. Interviews gathered information

about family experiences during and after their

RRHD participation. Analysis of the data col -

lected was used to assess “the efcacy of the

assessment process and the housing/service

intervention related to how successfully house -

holds are able to independently sustain housing

after receiving short-term leasing assistance,”

as HUD stated in the notice of RRHD program

funding availability. The information collected

through these interviews will provide the rst

systematic view of what rapid re-housing pro-

grams do for families and what effects those

actions have on housing stability that goes

beyond a simple determination that they did

or did not return to shelter within 12 months.

7

This report does not attempt to discuss family

outcomes, as a relatively small number of fami-

lies had exited as of the time we conducted in-

terviews with RRHD programs. Also, the early

exits may disproportionately represent families

who had exited unsuccessfully, because those

who were successfully engaged in RRHD pro-

grams would still be enrolled in programs.

7 RRHD programs started serving families between October 2009 and

August 2010. Depending on the program and sometimes on the family,

programs offer from 3 to 15 months of rental assistance. Followup

interviews of study families began in late 2011, and findings of the

outcomes evaluation are available in the report: Rapid Re-housing for

Homeless Families Demonstration Programs: Outcomes Evaluation

Report.

8

RAPID RE-HOUSING FOR HOMELESS FAMILIES DEMONSTRATION PROGRAMS EVALUATION REPORT

CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION

Research Questions

The process component of this evaluation

provides an important opportunity to examine

how 23 communities structure and deliver their

RRHD programs. Research questions for the

process component cluster into the following

four groupings.

How Do RRHD Programs Fit Into Their

Communities?

1. How isolated or well integrated are the RRHD

programs within their community service

networks? Is the RRHD program limited to

one shelter, available to guests of all family

shelters, something in between, or something

entirely different? How is referral structured?

2. How did the community decide on the size,

structure, and characteristics of its RRHD

program and who would run the program?

What factors affected the decisions and the

ultimate shape of the program? What previ-

ous experience did the community have with

anything like RRHD?

How Do the RRHD Programs Identify

Appropriate Participants?

3. What does the intake process look like? Is

there a central intake process? Is assessment

for RRHD part of general shelter intake for

families, or is it a separate step? Who does it?

How do families get to it? Where and when

does it happen?

4. How is assessment done? Who does it? What

tool is used? How has it worked? Has the way

it is used, or the tool itself, been modied

since RRHD began? Why, and in what ways?

Who Is Served and Who Is Not?

5. What families do RRHD programs serve?

What families are rejected? What families

never get a chance to be assessed? Why?

6. How is a family’s eligibility determined? What

criteria are used? How exibly or rigidly are

criteria applied? What proportion of assessed

families is ultimately referred to the RRHD?

What proportion to less intensive services?

What proportion to more intensive services?

7. How much does the availability of other

rapid re-housing programs in the com-

munity inuence which families an RRHD

program will serve?

What Housing and Services Do the RRHD

Programs Deliver?

8. What do RRHD programs offer in terms of

housing and services to families who enter

the program?

9. How does the service process work? What

determines how long a family’s rental assist -

ance lasts or how much it is? What supportive

services are offered with the housing assis-

tance? How is the decision made that enough

services have been provided? How is the

decision made that the original term of hous-

ing subsidy is enough and that the family is

now on its own? What factors would result

in extension of benets?

Answers to these questions are vital to the

overall evaluation for several reasons:

• First, they will help us understand whether

different RRHD programs are serving different

types of families and offering different types

of interventions, indicating not only how

RRHD programs work but also showing how

they differ from place to place. If we are to

interpret program outcomes derived from

surveys of participating families, we need to

understand these differences and incorporate

them into analyses, including how families

are selected, what the families receive, and

how the programs are structured.

• Second, to develop meaningful recommenda-

tions about how and when RRHD programs

should be implemented, we need to know

about the variety of RRHD approaches, which

ones are most easily mounted, which ones

might be best suited for different community

circumstances, and the factors that can limit

the effectiveness of these approaches.

9

PART I: HOW THEY WORKED—PROCESS EVALUATION

CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION

• Finally, the information gleaned from early

phases of the process evaluation will help

shape the strategies to be used for gathering

outcome data from participating programs.

Process Evaluation Data Collection

To obtain the data needed to answer these re-

search questions, Abt’s research team gathered

information from all 23 RRHD communities be-

tween February 2011 and May 2011. Members

of the research team conducted in-person site

visits with 12 RRHD programs and telephone

surveys with the remaining 11 programs. Deci-

sions about which programs to visit and which

to call depended largely on the availability and

location of research team members but also

on the size of the programs. Key stakeholders

interviewed included representatives of the

agency that received the RRHD grant (the

grantee), representatives of any programs to

which the grant recipient allocated some grant

resources to serve program families (subgrant-

ees), and CoC member(s) involved in planning

for the program. Caseworkers in each program

who do the actual work with participating

families were always interviewed. Often the

telephone survey was conducted during the

course of more than one call with one or more

types of respondents just described; site visits

were regularly completed during the course of

1 entire day.

The research team members used a common dis -

cussion guide for all contacts with RRHD pro-

grams, writing a case report after completing

conversations with program representatives

that summarized what they learned in a struc-

tured format. These reports were organized

around the central issues of the process evalu-

ation and provide the information organized

and summarized in this report’s remaining

chapters. The evidence to answer the research

questions was discussed during a 2-day meeting

of all research team members, including the

Principal Investigator Dennis Culhane; Project

Quality Advisor, Jill Khadduri; and HUD

Government Technical Representative, Elizabeth

Rudd. These discussions helped to structure