Shadow Troop Handbook

-A doctrinal approach to the employment of the RQ7-B Shadow Tactical Unmanned Aircraft

System (TUAS) in the Armed Reconnaissance Squadron (ARS)

-Adapted from Army UAS Operations FM 3-04.155

DESTRUCTION NOTICE: Destroy by any method that will prevent disclosure of contents or

reconstruction of the document.

Combat Aviation Brigade, 1

st

Infantry Division

2011

i

Shadow Troop Handbook

Contents

Page

Forward ....................................................................................................................... iii

Chapter 1 MISSIONS AND ORGANIZATION.......................................................................... 1-1

Section I - Overview.................................................................................................. 1-1

Fundamentals........................................................................................................ 1-1

Full Spectrum Operations...................................................................................... 1-2

Section II - RQ-7B Shadow Troop.............................................................................. 1-2

Organization……...................................................................................................... 1-2

Section III – Duties and Responsibilities.................................................................... 1-4

Additional Considerations ..................................................................................... 1-6

Chapter 2 COMMAND, CONTROL, AND COMMUNCATION.................................................. 2-1

Section I – Command………........................................................................................ 2-1

Division Areas of Operation................................................................................... 2-2

Section II – Control…................................................................................................. 2-3

Levels of Interoperability....................................................................................... 2-4

Mission Planning…................................................................................................. 2-7

UAS Request Procedures…....................................................................................2-11

Airspace Control….................................................................................................2-13

Section III - Communication…..................................................................................2-14

Chapter 3 EMPLOYMENT.................................................................................................... 3-1

Section I – Missions……………………............................................................................. 3-1

Overview.................................................................................................................3-1

Teaming of Manned and Unmanned Aircraft......................................................... 3-1

Reconnaissance Operations...................................................................................3-2

Security Operations................................................................................................ 3-5

Attack......................................................................................................................3-5

Section II – Employment Considerations...................................................................3-6

Shadow Product Distribution..................................................................................3-6

Laser Designator..................................................................................................... 3-7

Payloads..................................................................................................................3-9

Targeting...............................................................................................................3-11

Battle Damage Assessment................................................................................. 3-13

Section III – Ground Unit and Aviation Coordination..............................................3-14

Ground Maneuver Unit Support.......................................................................... 3-14

Positive Location and Target Identification..........................................................3-15

ii

Fratricide..............................................................................................................3-15

Section IV – Command and Control Support..........................................................3-16

The Aerial Layer................................................................................................... 3-16

Section V – Homeland Security...............................................................................3-18

Chapter 4 SUSTAINMENT.................................................................................................... 4-1

Section I - Logistics.................................................................................................... 4-1

Section II - Maintenance............................................................................................4-2

Contractor Logistical Support................................................................................. 4-5

Appendix A REFERENCE LISTING.............................................................................................A-1

iii

FORWARD

In an age where the changes in equipment are starting to outrun the changes in doctrine, this manual was

created to provide a centralized starting point for doctrinal and Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTP)

research for the Full Spectrum Armed Reconnaissance Squadron (ARS) and Shadow Troop Commanders. We

took the informative Army UAS Operations Manual and revised it to fit the needs of the Shadow Troop key

leadership. Mostly, we used this manual as a means to fuse our lessons learned into the future development of

the Shadow Troop operations.

The troop creating this manual, Falcon Troop, 1-6 Cavalry, was created by the 1

st

Infantry Division Commander

and Combat Aviation Brigade (CAB) Commander to provide an aviation standardization program to the division’s

Unmanned Aerial Systems (UAS). Falcon Troop trained up at Fort Riley, working with the division’s Shadow

platoons and Kansas State University’s UAS program. They deployed to OIF and maintained an Aircrew Training

Program (ATP) command relationship with four separate Shadow platoons from 3

rd

ID, 10

th

MTN, 25

th

ID, and 1

st

ID. Additionally, they established a Scan-Eagle tactical UAS program in USD-C, manning the program with

Soldiers of all Military Occupational Specialties (MOS) from across the CAB. Their work resulted in a 67%

reduction in aviation accidents and incidents and an increase in cross-training between manned and unmanned

aviation.

This manual was tailored towards the key leadership in the Full Spectrum ARS. With the audience as the primary

staff, commanders, and senior leadership, this manual does not reinvent the wheel for any doctrine already

implemented at the OH-58D Squadron level. We took much of our information from FM 3-04.155 Army

Unmanned Operations Manual, which provides a wealth of information for a general Unmanned Aerial System

leader. With this manual, we deleted information that was not needed for the Shadow TUAS key leadership and

infused our lessons learned. In many instances, I either replaced the wording to address a specific point or

simply replaced the section. My intent was not to delete key information, but to focus the most relevant

information for a future Shadow Troop commander.

In a standard military field manual, the ability to portray lessons learned and successful Tactics, Techniques, and

Procedures becomes difficult. I addressed this problem by maintaining, as close as possible, a military manual

approach, but created text boxes to portray our lessons learned. This manual is meant to be a working

document and will continue to grow and change with the dawn of a new reconnaissance era. On the back page I

have placed a disc loaded with key information which is normally given to UAS leadership in courses at Fort

Huachuca, AZ.

As scout pilots, our sights will no longer slow our aircraft to sub-100 knots airspeeds and four kilometers viewing

capability. Our sight will be autonomously searching at times, and at other times will be in our direct control

extending our engagement distance to the limits of the hellfire. This concept of the Shadow being an extension

of the scout pilot’s system is the first concept that needs to be internalized by the modern-day air cavalrymen.

They should know the limits of the Shadow like they know the limits of their current Mast Mounted Sight. This

iv

manual does not discuss the specific limitations of the Shadow aerial vehicle, but rather emphasizes the doctrine

that will need the OH-58D Air Mission Commander’s expertise on both types of aircraft in his combined team.

Finally, the last page of this manual has a disc containing multiple publications, TTP briefs, and school-house

briefs. This is our additional attempt at pushing lessons learned out to the field. Falcon Troop managed to build

and implement an emergency re-trans capability for 2-1 Advise and Assist Brigade’s (AAB) operational area

during Operation Iraqi Freedom. We were also successful at building TTPs for hasty remote Hellfire

engagements between the Shadow TUAS and manned platforms. These tactics exercised other processes,

including laser designation operations, communications relay, and airspace coordination. Also on this disc, I put

a copy of this manual, the Shadow Troop Handbook. My intent is for you to take this manual, update it, re-print

at your local Defense Logistics Agency print shop, and pass on to the next Shadow Troop. It is a small step now,

but by the time the third or fourth Combat Aviation Brigades receive their Full Spectrum Shadow Troops, I hope

the lessons learned will be spilling over on the pages of this manual.

WILLIAM L. KOCH

CPT, AV

Commanding

1 - 1

Chapter 1

Missions and Organization

The RQ-7B Shadow Tactical Unmanned Aerial System (TUAS) fielded organically in the Attack Reconnaissance Squadron

(ARS) is organized and equipped to provide a combat enabler to the Combat Aviation Brigade.

UAS significantly increase situational awareness (SA) and the ability to decisively influence current and future

operations when employed as a tactical reconnaissance, surveillance, and target acquisition (RSTA) platform. UAS

provide near real time (NRT) battlefield information, precision engagement, and increased C2 capability to

prosecute the fight and shape the battlefield for future operations. UAS capabilities are maximized when employed

as part of an integrated and synchronized effort.

FM 3-04.155 Army Unmanned Aerial Systems Operations

When properly employed, the Shadow TUAS will serve the ARS Commander as an extension to the scout-attack

manned platforms, an autonomous, continuous-coverage asset, and a search-and-designate platform.

.

SECTION 1 - OVERVIEW .

FUNDAMENTALS

1-1. The Shadow TUAS extends the ARS Commander’s ability to support the full spectrum of conflict through

reconnaissance, security, aerial surveillance, communications relay, and laser designation.

1-2. The UAS supports the full spectrum capability through augmenting all warfighting functions:

a. Movement and Maneuver: Provides the full depth of the reconnaissance and security missions in order to aid

the ground commander in movement of friendly forces and provide the ground forces with freedom to maneuver.

b. Intelligence: The Shadow Troop provides Near Real Time (NRT) intelligence, surveillance, and

reconnaissance (ISR) and extends the capability through flexible RSTA platforms as an organic asset to the ARS

and CAB commanders. They greatly improve the situational awareness of the ARS and aid in employing the Scout

Weapons Team (SWT) in high threat environments.

c. Fires: Coupling the Communication Relay Package (CRP) with the Laser-Designating (LD) payload, the

Shadow aids in all levels of the Decide, Detect, Deliver, and Asses cycle.

d. Protection: Through continuous reconnaissance, the Shadow Troop can significantly increase the force

protection in and around secure operational bases.

e. Sustainment: The Shadow provides reconnaissance and security along supply routes and logistics support

areas. Using the CRP, the Shadow can talk directly to the convoy commander for immediate reaction.

f. Command and Control: The Shadow greatly increases the ARS commander’s ability to control the fight. The

CRP package extends radio transmission ranges to 240 kilometers. With proper TTPs, the Shadow can serve as an

emergency re-transmitting capability to isolated personnel.

1 - 2

FULL SPECTRUM OPERATIONS

1-3. The Shadow Troop aids the ARS and CAB commanders through the full spectrum of operations from stable peace

to general war:

a. Peacetime Military Engagement: The Shadow Troop provides counterdrug activities, recovery operations,

security assistance, and multinational training events and exercises.

b. Limited Intervention: Provides search for evacuation operations, security for strike and raid operations,

foreign humanitarian assistance (search of survivors during disaster relief), and searching for weapons of mass

destruction.

c. Peace operations: Provides peacekeeping through surveillance and security for peace enforcement operations.

d. Irregular Warfare: Assists in tracking enemy personnel while combating terrorism and unconventional

warfare.

e. Major Combat Operations: Provides the capability to extend the communication of friendly units, emergency

retransmitting capability to isolated personnel, target acquisition, and laser designation.

SECTION II – RQ-7B SHADOW AERIAL RECONNAISSANCE TROOP .

ORGANIZATION

1-4. The Shadow Troop will be organic to the Attack Reconnaissance Squadron employed at the Squadron, Aviation

Brigade, or Infantry Division level. Additionally, the Shadow Troop commander should maintain an Aircrew Training

Program commander relationship with the IBCT Shadow platoons.

1-5. The Troop leadership will be comprised of Aviation Officers from across the ARS. This Troop should be

considered as a second command, in order to ensure the subject matter expertise for employing the OH-58D in

conjunction with the Shadow UAV. Further, the Shadow Troop commander is the officer responsible for maintaining a

strong relationship between the manned and unmanned assets.

1-6. Similar to an aerial reconnaissance troop of OH-58Ds, the Shadow Troop will be comprised of two aerial

reconnaissance Shadow platoons, and a headquarters section which includes an exploitation cell. Each platoon will be

comprised of a flight operations section and a maintenance section.

1-7. The aerial reconnaissance platoon consists of—

• Flight operations section.

• Maintenance section.

• Four UA.

• Four OSRVTs.

• Two vehicle-mounted OSGCS.

• Two ground data terminals (GDTs).

• Two personnel/equipment transport vehicles with one equipment trailer.

1 - 3

• Two tactical automated landing systems (TALSs).

• One vehicle-mounted air vehicle transport (AVT) with launcher trailer.

• One vehicle-mounted mobile maintenance facility (MMF) with maintenance trailer.

• One portable ground data terminal (PGDT).

• One portable ground control station (PGCS).

1-8. The Shadow platoons will move the Technical Inspectors and Certified Field Support Representatives into the

Aviation Unit Maintenance Troop to prevent conflict of interest and maintain aviation standards of maintenance. The

Troop’s breakdown should mirror the chart below:

Figure 1-1. Suggested MTOE

LESSONS FROM THE FIELD

We manned our Safety and Standardization program with OH-58D senior aviators. After

being separated from aviation brigades since the birth of the Shadow UAS, the Shadow

technical personnel have never received aviation specific training. They taught the

Shadow maintainers and operators very detailed aviation specific information which

resulted in a 67% reduction in accidents.

Programs that needed specific attention in the platoons we worked with are below:

Standardization:

Flight Records maintenance

Airspace management and understanding

Radio communication and crew coordination

No-notice and evaluation program

Safety:

FOD prevention program

Trust in the Emergency Procedures

Quality Control and Maintenance records procedures

1-9. The Squadron should also consider manning an exploitation cell within the headquarters section of the Shadow

Troop. The benefits of the exploitation cell will be discussed throughout this manual.

1-10. The Troop will be fielded with four Ground Control Stations (GCSs) which will allow the ability to provide two

GCSs for launch and recovery and two GCSs in forward locations where they best support the operational mission.

1 - 4

SECTION III – DUTIES AND RESPONSIBILITIES .

1-11. The duties and responsibilities of the personnel inside of the Shadow Troop will mirror those positions in the peer

OH-58D Kiowa Aeroscout Troops. The following is a list of duties and responsibilities to expect in the Shadow Troop.

COMPANY LEADERSHIP

1-12. The company commander, first sergeant, platoon leaders, and platoon sergeants are responsible for the integration,

training and development, and line maintenance of the UAS organization. Their principal concern is integration of the

unit into the combined arms fight. Company leadership should be proficient in UAS and OH-58D Scout Weapons Team

(SWT) employment and have an in-depth knowledge of enemy forces and how they fight. Company leadership is

responsible for—

• Aircraft and system maintenance, ensuring availability to meet the supported commander’s intent.

• Training leaders and evaluating crews and individuals. Assessing training according to the commander’s task list

(CTL).

• The unit safety program.

• Assigning individuals to perform specific duties required for safe flight operations not designated in the modified

table of organization and equipment.

• Maintaining familiarity with all aspects of UAS.

• Assisting in management and enforcement of the Army’s Shadow TUAS standardization program throughout the

Infantry Division.

1-13. As an extension of company leadership, additional responsibilities for the operation of UAS are detailed below.

STANDARDIZATION OFFICER

1-14. The standardization officer (SO) works directly for the commander and assists the platoon leader in developing and

implementing the unit aircrew training program (ATP). He assists in crew selection and normally performs as a member

of the company operations planning cell. The SO provides quality control for the ATP through the commander’s

standardization program (refer to training circular [TC] 1-600 and TC 1-611). He is also a principal advisor to the

subordinate unit instructor operators (IOs). The SO is tasked to provide expertise on unit, individual, crew, and collective

training to the commander. He also—

• Serves as a member of the ARS standardization committee.

• Advises the commander on development of the CTL.

• Monitors unit standardization and ATP.

• Maintains unit individual aircrew training folders (IATFs).

• Monitors unit no-notice programs.

• Assists the master gunner in development and execution of realistic company gunnery tables.

• Develops company situational training exercises (STXs).

• Attends training meetings.

INSTRUCTOR OPERATOR

1-15. The IO is responsible for assisting the platoon leader in properly training combat-ready crews. He provides quality

control for the ATP via the commander’s standardization program. Although the IO works directly for the platoon

leader, he receives guidance and delegated tasks from the company SO. This ensures training is standardized throughout

the company. The IO—

• Conducts no-notice evaluations.

• Assists the company SO in maintaining IATF.

• Assists in development of company STX.

• Assists in development and execution of company gunnery tables.

• Assists the company SO in development of the CTL.

1 - 5

UNIT TRAINER

1-16. The unit trainer (UT) is an operator designated to instruct in areas of specialized training (TC 1-600). He assists the

IO/SO in unit training programs and the achievement of established training goals.

SAFETY OFFICER

1-17. The safety officer, military occupational specialty (MOS) 150UB, assists the commander in developing and

implementing all unit safety programs. Commanders rely on their safety officers to monitor all safety aspects of the unit

and provide feedback and advice to the commander. He serves as the commander’s advisor on risk management. The

safety officer is the commander’s primary trainer for annual safety training requirements and composite risk

management, including—

• Safety meetings (quarterly and monthly).

• Individual risk assessment.

• Crew risk assessment and mitigation.

• L/R site surveys.

• Class III/V and assembly area site surveys.

• Convoy risk assessment and safety briefs.

• UA accident and incident investigations in accordance with (IAW) Army regulation (AR) 385-40.

UNMANNED AIRCRAFT SYSTEM OPERATIONS TECHNICIAN

1-18. The UAS operations technician (MOS 150U) analyzes UAS mission requirements and determines necessary

payloads. The operations technician maintains detailed knowledge of airspace requirements to plan missions. MOS 150U

applies to all UAS warrant officers regardless of aircraft training/qualifications. Additional duties/responsibilities

include—

• Integrating UAS into collection plans.

• Conducting detailed analysis of UAS information for integration into all-source intelligence products.

• Analyzing information to cue other collection assets.

• Coordinating dynamic retasking of UAS.

• Coordinating dissemination of UAS products.

• Coordinating UAS airspace and frequency requirements.

• Developing, implementing, and supervising the UAS standardization, maintenance, and safety programs.

• Establishing and maintaining an ATP.

• Conducting tactical mission planning and air-to-ground integration.

• Acting as a liaison at all command levels for UAS missions.

MISSION COMMANDER

1-19. The MC is a leadership position and not a crew duty assignment. MC responsibilities include, but are not limited

to,—

• Mission planning, briefing, and execution.

• Ensuring all ground and flight operations are safely conducted.

• Coordinating airspace and frequency deconfliction.

• Coordination with the crew and all supported units.

1-20. The MC must be prepared to make critical decisions throughout mission planning, briefing, and execution. The

MC must possess a thorough understanding of UAS operations, capabilities, and the process in which a mission is

executed while coordinating with unit, battalion, brigade and division staffs. The MC must also know the ground tactical

plan and possible mission contingencies.

UNMANNED AIRCRAFT OPERATOR

1 - 6

1-21. The unmanned aircraft operator is responsible for the safe operation of the UA. He must be tactically and

technically proficient in the unit mission essential task list. The unmanned aircraft operator pre-flights, launches,

recovers, post-flights, and performs operator-level maintenance actions on the UAS. He is responsible for both the UA

and sensor. The unmanned aircraft operator controls and/or monitors the actual flight of the UA from a GCS, PGCS, or

similar device. This is normally done through the use of a monitor and not by direct visual contact with the UA.

MISSION PAYLOAD OPERATOR

1-22. The mission Payload Operator (PO) is responsible for the operation of the payload to include weapons and sensors.

The POs employing weapons systems will be qualified and current according to U.S. Army directives.

CREW CHIEF

1-23. The crew chief is a ground crewmember who is required to perform duties essential to the flight operations of a

UAS. The crew chief is responsible for coordinating the actions of all ground crewmembers in the manner directed by

the commander of the aircraft.

LESSONS FROM THE FIELD

Currently fielded Shadow platoons have conflict of interest in the manning of Technical

Inspectors (TIs) in the line platoons. After fielding to the Aviation Brigade, we would

suggest keeping all TIs in the Aviation Unit Maintenance (AVUM) QC section. As

Infantry Brigades deploy, the TIs can work out who goes with which IBCT and maintain

their rating schemes with the AVUM. This will greatly alleviate the current existing

conflict of interest.

EXPLOITATION CELL

1-24. The exploitation cell should consist of two imagery analysts for immediate exploitation of imagery. This team

would provide the following benefits:

• Timely effort of Analyzing, Assessing, Disseminating, Planning, Preparing, Collecting, and Producing products to

supplement the war-fighter.

• Ability to collect, record, and store intelligence to prevent contamination and ensure strict chain of custody from

point of capture.

• Provide crucial information related to mission requirements and Soldier safety through imagery and video analysis.

ADDITIONAL CONSIDERATIONS

1-25. Additional Considerations: The following should be considered in building the Shadow Troop manning package:

a. Aviation Integration and Officer Professional Development: The Platoon Leaders approved for a Shadow

platoon are Chief Warrant Officer Three (CW3) officers. The unit should consider placing the CW3s in the Troop

Standardization and Safety positions and fielding the Platoon Leader positions to OH-58D Lieutenants and junior

Captains. This will aid in growing mature officers with a strong awareness of UAS operations, as well as further

integrate the aviation mentality into the Shadow program.

c. Aircrew Training Program (ATP) Relationship: The Troop leadership maintains a standardization and

safety relationship with all Shadow platoons in the Division. The Shadow Troop commander is the ATP

Commander for all Shadow operators in the division. The Troop Safety and Standardization officers will help

maintain the Aviation Safety program and individual flight records for all Shadow operators. They will conduct

flight record and safety inspections as well as mentor the Shadow platoon leadership.

2 - 1

Chapter 2

Command, Control, and Communication

Efficient command and control of an organic ARS Shadow Troop will rely heavily on knowledge of the Shadow’s full

capability and the ability for the Shadow operator to communicate directly with commanders at all levels. As an extension to

the OH-58D, the Shadow will aid in clearing enemy territory prior to reconnaissance and security missions only if the

manned aviation assets can communicate directly with the UAS operator. Additionally, the commander must set a clear

priority for the UAS effort and ensure command, control, and communication of the UAS supports their effort.

UAS on the battlefield are significant combat multipliers that enhance our situational awareness, improve combat

effectiveness, and save Soldiers lives.

GEN Richard H. Cody

Vice Chief of Staff of the Army, July 2008

The UAS extends the sensor to shooter link and provides NRT battlefield information. This chapter pulls heavily from FM

3-04.155 Army UAS Operations. Minor changes were made to specifically address the Shadow UAS employed in the ARS

squadron.

SECTION I – COMMAND .

2-1. The commander provides his staff with a clear intent for employing all available UAS, to include:

• Priority of support.

• Weapons release authority.

• Dynamic re-tasking criteria.

• Priority of UA access to OSRVT-equipped units.

• C2 support priorities.

COMBAT AVIATION BRIGADE

2-2. The CAB commander is the division commander’s senior advisor for employment of aviation assets. The CAB

commander and staff are the primary integrators of manned and unmanned aviation operations. They provide expertise,

technical knowledge, and aviation experience integrating aviation operations into the division commander’s scheme of

maneuver. The CAB plans and executes UAS operations in coordination with the division staff, Fires Brigade, BFSB,

and BCT.

2-3. Recent operations have led to the consolidation of IBCT TUAS platoons under CAB C2. This task organization has

resulted in increased efficiencies in mission support, maintenance, and safety. A clear understanding of mission support

and tasking authority for IBCT TUAS consolidated under the CAB must be achieved to enable effective UAS operations.

This consolidation will be a minimum of ATP relationship between the Shadow Troop commander and the IBCT

Shadows.

ATTACK RECONNAISSANCE SQUADRON

2-4. The ARS commander is the subject matter expert and the brigade commander’s senior advisor for the employment

of the Shadow TUAS. They provide expertise and technical knowledge in the employment of the RQ-7B Shadow

TUAS. The ARS plans and executes mixed SWT/Shadow teams and autonomous Shadow reconnaissance missions in

coordination with the aviation brigade to support the Ground Force Commander’s scheme of maneuver. This will be a

2 - 2

combination of direct support missions, general support missions, and organically tailored reconnaissance

missions.

LESSONS FROM THE FIELD

We maintained a Scan-Eagle program that conducted missions directly for the Division

Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR) team. When not specifically

employed or when target decks were completed early, we organically chose targets for

observation and reconnaissance. The key take away from this program: the operator is

the primary observer and needs to maintain the reconnaissance mind-set throughout the

entire mission set, regardless of mission origin.

DIVISION AREA OF OPERATIONS

2-5. A large division area of operation, complex terrain operations, and a noncontiguous environment place greater

demands on organic RSTA/ISR assets. UAS employment in this environment requires careful synchronization. All

activities must be orchestrated and fused at the division current operations integration cell (COIC) to maximize UAS

capabilities.

ONE SYSTEM GROUND CONTROL STATION POSITIONING

2-6. OSGCS positioning is critical to successful employment of UAS. The OSGCS provides the technical means to

receive UA sensor data. The unmanned aircraft operator, PO, and MC assigned to the OSGCS provide tactical and

technical expertise to facilitate UAS operations. The CAB commander advises the division commander on placement of

this critical UAS component to maximize its effectiveness. The CAB, BFSB, Fires brigade, and BCT conduct disparate

missions simultaneously across the division area of operation, with different TTP, focus, and skill sets required. This

requires integration of overall aviation operations at division-level to avoid redundancy of effort. An additional

consideration is the Shadow platoons in the IBCT BSTBs and the OSGCSs that remain in their control. With a cohesive

ATP relationship built between the IBCT Shadow platoons and the ARS Shadow Troop, direct support missions to the

IBCT in an extended range environment can be controlled by the IBCT Shadow operators, POs, and MCs.

Single-Site Operations

2-7. In single-site operations, the entire UAS unit is co-located. Single-site operations allow for easier unit command,

control, communication, and logistics. Coordination with the supported unit may be more difficult due to distance from

and communications with the supported unit. In addition, single-site operations emit a greater electronic and physical

signature.

Split-Site Operations

2-8. In split-site operations, the UAS element is typically split into two distinct sites: the mission planning control site

(MPCS) and the L/R site. The MPCS is normally located at the supported unit’s main or tactical CP location. The L/R

site is normally located in more secure area, positioned to best support operations.

2-9. The IBCT Shadow platoons should also consider consolidating launch-recovery with the ARS Shadow Troop in

order to receive the additional benefits of the ARSs large logistical footprint. The IBCT Shadow platoons can focus

directly on the MPCS with forward-staged GCSs.

LESSONS FROM THE FIELD

In Camp Taji, Iraq, a single launch and recovery site was developed to launch four

Shadow TUAS platoons during the surge in Baghdad. The platoons were able to share

assets which resulted in significant increases in the amount coverage, playtime for the

ground commander, and surge capabilities. We suggest even considering consolidating

with the IBCT Shadows to allow these capabilities to the entire division.

2 - 3

Mission Planning and Control Site

2-10. The MPCS consists of the OSGCS, OSGCS personnel, and supporting equipment. The MPCS receives the tasking,

plans the mission, takes control of the Shadow UA after launch for mission execution, and reports information. The

MPCS releases control of the UA for recovery.

Launch and Recovery Site

2-11. The L/R site consists of UA, L/R systems, OSGCS, maintenance equipment, GSE, and supporting personnel. The

L/R site receives the mission from the MPCS, then prepares and launches the UA. After the UA has reached a

predetermined altitude, the OSGCS operator at the MPCS assumes control of the Shadow UA. For recovery of the UA,

this process is reversed. When selecting the L/R site, units should consider—

• Distance and LOS to possible target areas.

• Adequate space for system L/R or engineer support.

• Sufficient obstacle clearance to conduct takeoffs and landings.

• Avoiding areas with high population densities, multiple high power lines, and high concentrations of

communications equipment and transmitters, as these may interfere with UA control.

• Proximity to the MPCS to support effective communications and UAS control.

• Site selection incorporating operations security considerations to reduce the possibility of detection and destruction

by enemy forces.

• Impact of local manned aircraft operations.

• Positioning of GSE to accommodate network and power cables while considering noise abatement and security.

2-12. One primary limitation of the IBCT Shadow platoons is the MTOE of only one launcher system. Consolidating

IBCT Shadow platoons within the Shadow Troop footprint allows platoons to share low-density pieces of equipment as

well as manning to cover 24-hour operations.

LESSONS FROM THE FIELD

Facilities planning: A detailed effort is required to ―download‖ all of the electronics

equipment to a more suitable Ground Control Station environment. Therefore, most

facilities tailor specifically to keeping the GCS operating as built. Generally, this means

backing up a HMMWV up to a building that houses the mission coordinator and

exploitation cell. This keeps the team centrally located and in constant communication

with one another, but precludes the requirement to download all of the equipment.

SECTION II – CONTROL .

2-13. Control of forces and functions helps commanders and staff compute requirements, allocate means, and integrate

efforts. Control permits commanders to acquire and apply means to accomplish their intent and develop specific

instructions from general guidance.

2-14. The critical aspect of TUAS control is the requirement for ARS battle staff officers and NCOs to integrate TUAS

with maneuver and/or intelligence efforts for both current and future operations. Communications between the battle

staff and TUAS MC must be open and frequent, particularly during dynamic retasking and weapons employment.

2-15. To support tactical RSTA operations in NRT, information must flow rapidly between UAS and the supported unit.

Locating an OSGCS near the CP, or employing an OSRVT at the point of decision, facilitates this rapid information

flow. For example, OSGCS information distributed to the all source analysis system (ASAS) remote workstation meets

the intelligence analyst’s requirements for immediate battlefield intelligence and transmission of data for long-term

analysis and exploitation. The advanced field artillery tactical data system (AFATDS) operator may use this information

for immediate target engagement or future target development. The OSRVT supports decision making at the point of

decision, and facilitates coordination between the OSRVT operator and CP to ensure synchronized operations.

SHADOW TUAS CONTROL METHOD

2 - 4

DIRECT UNMANNED AIRCRAFT CONTROL

2-16. Direct UA control involves an OSGCS controlling a UA with a LOS downlink to the UAS LOS limit (figure 2-1).

The limit for the Shadow UAS is 120 km. The UAS OSGCS conducts all operations; from take-off, through mission

execution, to landing; or receives the UA from another OSGCS responsible for L/R of the UA.

Figure 2-1. Direct unmanned aircraft control

AERIAL DATA RELAY

2-16. Aerial data relay does not apply to the Shadow UAS.

SATELLITE UPLINK CONTROL OF UNMANNED AIRCRAFT

2-17. Satellite uplink control does not apply to the Shadow UAS.

LEVELS OF INTEROPERABILITY

2-18. Levels of interoperability (LOIs) define how UAS interface with supported units during operations. Familiarity and

application of LOIs, during mission planning, prepare units to integrate UAS into future operations. Army units interact

with the UAS using one of the LOI. Current hardware/software constraints preclude the ability to fully utilize all levels.

The AH-64D upgrade (Block III) is scheduled to provide LOI 4 capability. OSRVT currently provides units with LOI 2

capability; LOI 3-5 are not currently available for the Shadow TUAS.

2 - 5

LEVEL 1

2-19. LOI 1(figure 2-4, page 2-6) is the receipt and display of UAS derived imagery or data without direct interaction

with the UA. Imagery and data is received through established communications channels, most often from the OSGCS

controlling the UA. LOI 1 requires OSGCS connectivity with the global broadcast system (GBS), digital video

broadcasting-return channel via satellite FMV, common ground station, ABCS, or other similar systems.

• In figure 2-4 the troops in contact (TIC) cannot receive video from UAS.

• The OSGCS receives video or SAR/GMTI imagery. The information is then distributed to the CP through a network

for further distribution, development, and exploitation.

• UA data passes from one CP to another for increased SA.

Figure 2-4. Level of interoperability-1

2 - 6

LEVEL 2

2-20. LOI 2 (figure 2-5, page 2-8) is the receipt and display of imagery and data received directly from the UA to the

supported element. The Shadow’s CRP enables the supported unit to communicate sensor movement and adjustment

requirements to the OSGCS operator during operations. LOI 2 requires that a system (OSGCS or OSRVT) directly

receive video or other data from the UA for use by the support unit. At a minimum, LOI 2 operations require a UA-

specific data link and compatible LOS antenna to receive imagery and telemetry directly from the UA.

• TIC, with an OSRVT, can receive video imagery from UAS. Shadow CRP enables direct coordination between TIC

and OSGCS operators.

• The OSGCS receives video or SAR/GMTI imagery. The information is then distributed to CP through a network for

further development/exploitation.

• The adjacent CP receives video from UAS through the OSRVT and/or network for increased SA.

Figure 2-5. Level of interoperability-2

LEVEL 3-5

2-21. The Shadow UAS does not currently support LOI 3, 4, or 5 (for more information on these levels see TM 3-04.155

Army UAS Operations).

2 - 7

MISSION PLANNING

2-22. UAS mission planning is the same as manned aviation. However, the mission planning for the UAS pure teams

begins in the S2 Intelligence Shop on the Squadron Staff before going to the S3 Operations section. Following Squadron

staff planning, the mission is pushed to the Troop for continued planning.

MISSION

2-23. UAS capabilities and limitations determine which system (Shadow or OH-58D) is used for mission

accomplishment. The supported unit, division G-3/COIC, or ARS S3/S2 section provides mission requirements to the

Shadow Troop. Providing only target lists or ―target decks‖ to sequence UAS operations does not provide the supporting

unit the necessary amount of information required to integrate UAS effectively. Essential mission planning information

for Shadow operations is listed below. Adequate pre-planning, synchronization, and coordination of UAS operations

reduces the amount of no-notice, unplanned, dynamic retaskings and results in more effective utilization of the UAS with

greater endurance of the UA. Preplanned UAS operations should be included in the ATO/ACO cycle.

2-24. The UAS mission order includes—

• UAS unit AO.

• Mission statement/commander’s intent.

• Mission time window.

• Task organization.

• Reconnaissance objective.

• PIR/intelligence requirements.

• NAI/tactical areas of interest (TAIs).

• Routes.

• Fire support coordinating measures (FSCMs)/ACMs.

• Communications and logistics support.

• Restricted operations area (ROA)/restricted operations zone (ROZ).

• Altitudes.

• Weapons release authority.

• Laser codes.

ENEMY

2-25. UAS will operate in close proximity to heavily defended areas. They will be subject to hostile air defenses that may

include full range of anti-aircraft systems (conventional small arms, automatic antiaircraft weapons, man-portable air

defense [AD], and crew-served systems) using radar, optics, and electro-optics for detection, tracking, and engagement.

The threat includes launcher-mounted surface-to-air missiles; air-to-air weapons launched by fixed-wing (FW) aircraft,

helicopters, and counter-UAS UA; anti-radiation missiles; and directed energy weapons. Long-range acquisition systems

provide early warning and cueing for shorter-range kill systems. UAS may be subjected to offensive EW, computer

network attacks, computer network exploitation, and signal intelligence exploitation.

TERRAIN AND WEATHER

2-26. Both natural and man-made features limit sensor effectiveness and C2. Flat terrain eases LOS issues; while

mountainous terrain may reduce UA range.

2-27. AR 95-23 and unit standing operating procedures (SOPs) set minimum weather conditions stated as ceiling and

visibility, for UAS operations. Weather conditions must be at or above these minimums while the aircraft is flying and

over the entire mission area in which they are operating, unless the appropriate approval authority waives or approves

deviation due to criticality of a specific combat operation.

2-28. Weather effects on UA platforms include take-off and landing limitations, en route considerations, and weather

impact within the proposed mission area. Additional consideration must be given to the impact weather will have on the

planned sensor operations. Commands anticipating UAS support for wartime contingencies or exercises must research

the AO for data on meteorological trends. This information provides a method for anticipating UAS coverage.

Temperature, Precipitation, and Winds

2 - 8

2-29. Temperature, precipitation, and winds reduce the operating parameters of the Shadow; however, icing conditions

present a major dilemma. When the Shadow is operating in temperatures within five degrees Celsius of freezing and in

visible moisture, ice develops on the wings and fuselage, increasing drag and weight. When the operator notes the first

effects of icing, he will maneuver the UA out of the icing environment.

2-30. The Shadow can operate in light rain (.2 inches/hour). Depending on mission payload, light rain may degrade the

quality of Shadow imagery. Precipitation does not drastically degrade operations at an OSGCS; however, protection of

portable systems exposed to the elements may be required. Commanders must closely monitor the L/R site to confirm

runways/landing areas are suitable for Shadow operations. Other considerations include—

• Crosswinds in excess Shadow limitations create dangerous conditions for takeoff and landing.

• High winds at operating altitudes may create dangerous flying conditions.

Fog and Low Clouds

2-31. Fog and low cloud ceilings reduce the effectiveness of visual mission payloads. The IR camera image is degraded

by thin obscurations (dust and light fog), but cannot penetrate heavy fog or clouds. To collect needed exploitable

imagery, the Shadow must fly lower, increasing potential for detection and exposure to enemy AD systems. In addition,

fog at the L/R site reduces visual cues necessary to execute a safe landing. This could impact the Shadow’s ability to

respond to mission requirements if an alternate landing site is not available.

LESSONS FROM THE FIELD

Many of the limitations that deal with moisture apply most noticeably to take off. At the

same time every evening, the humidity in the air caused us to cancel our launches. By

adjusting our take-off slightly earlier, we were able to take-off and fly the entire mission

while still remaining within aircraft limits.

Lightning and Thunderstorms

2-32. The presence of lightning and thunderstorms at the L/R site or within the flight area pose significant risks to both

the operators and the Shadow. Wind, heavy precipitation, icing, and lightning within thunderstorms significantly reduce

the combat effectiveness of UAS. The Shadow should not be intentionally flown into thunderstorms.

TROOPS AND SUPPORT AVAILABLE

2-33. As with all aviation assets, early and detailed Shadow employment planning is critical to mission success. Cross-

echelon integration of all UAS supporting tactical operations maximizes the effectiveness of this limited asset.

TIME AVAILABLE

2-34. Time considerations are critical when planning for longer range Shadow missions, such as—

• Positioning L/R site to reduce en route times.

• Early planning for OSGCS positioning.

CIVIL CONSIDERATIONS

2-35. Tactical-level civil considerations focus on the immediate impact of civilians on current operations; however, they

also consider larger, long-term diplomatic, economic, and information issues. Civilian air traffic may become a central

consideration of planning.

KEY PLANNING PARTICIPANTS

2-36. UAS mission planning requires multi-echelon participation. Key planners include—

• G-3/Operations staff officer (S-3). Integrates overall division and brigade-level UAS assets to meet the

commander’s scheme of maneuver.

• G-2/Intelligence staff officer (S-2). Develops and coordinates PIR. Integrates intelligence requirements with the G-

3/S-3 to ensure maximized UAS employment.

• CAB commander and staff. Serves as the division commander’s UAS subject matter expert (SME).

• ARS commander and staff. Serves as the brigade commander’s UAS SME. Conducts UAS Mission planning for

division and organic missions.

2 - 9

• Shadow Troop commander and platoon leader. Conducts UAS mission planning and provides tactical and

technical input to commanders at all echelons.

• Shadow MC/technician. Provides technical and tactical UAS expertise, and conducts troop leading procedures

(TLP) and missions.

• ADAM/BAE cell. Plans, coordinates, and executes brigade airspace requirements.

• AC2 cell. Plans, coordinates, and executes division airspace requirements.

BRIGADE AND BELOW TASKING AND PLANNING

2-37. For most operations, the Shadow unit will integrate with a higher command echelon. The CAB S-3 synchronizes

aviation operations into the scheme of maneuver. The Shadow Troop will frequently team with manned systems during

ground maneuver and fire support (FS) operations. UAS mission planners must be familiar with operations across the

brigade AO to effectively anticipate mission requirements.

2-38. The S-2, in conjunction with the S-3, develops NAI/TAI to focus collection efforts. UAS’ inherent range and

endurance expands the brigade’s footprint for targeting and early warning.

SHADOW TROOP PLANNING PROCESS

2-39. The company commander receives valid requirements from the supported unit, usually in the form of a warning

order (WARNO) or operation order (OPORD). He begins initial planning according to TLP (table 2-2).

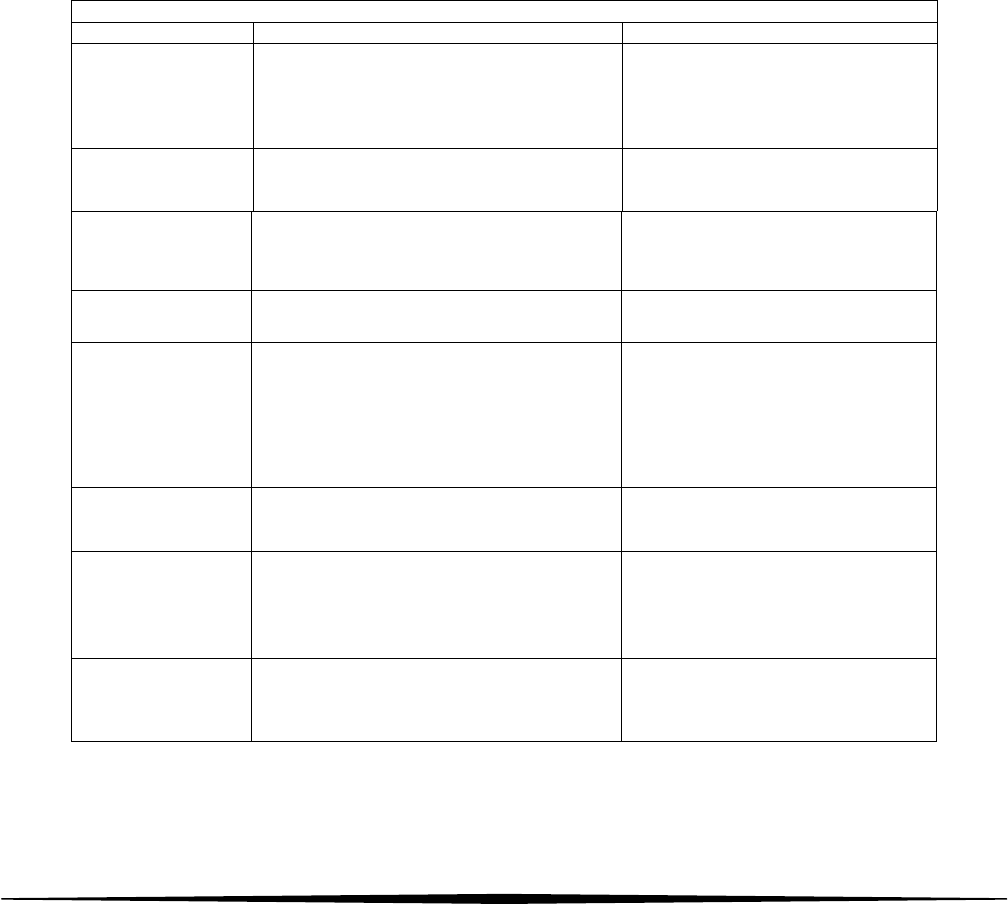

Tasking Management Responsibilities Matrix

Troop Commander

Mission Coordinator

Receive and

Analyze the

Mission

Receive WARNO or OPORD. Analyze the

mission. Determine payload requirement.

Determine crew availability and fighter

management. Determine aircraft

availability.

N/A

Issue the WARNO

Issue DA Form 5484, Mission/Schedule

Brief. Request ACMs, as necessary.

Submit schedule for ATO, as necessary.

N/A

Make a Tentative

Plan

Macro-plan mission (transit flight time for

split-site or split-base, set-up time for

communication relay mission).

N/A

Initiate Movement

Issue fragmentary order (FRAGO) to MC.

Initiate preflight of aircraft.

Conduct

Reconnaissance

(Receive and

Analyze the

Mission Revisited)

Receive and validate NAI/TAI of the ISR

plan. Attend targeting workgroup, as

necessary. Attend combined arms brief, as

necessary. Attend supported unit OPORD,

as necessary.

Receive validated NAI/TAI of the

ISR plan. Receive operational

graphics, as necessary. Download

ATO and ACO (weekly master,

daily, and changes), as necessary.

Review notices to airman

(NOTAMs), as necessary.

Complete the Plan

Develop prioritized target list. Develop

operations schedule. Direct mission

planning.

Complete mission planning.

Issue the Order

Brief MC and crew. Assign risk assessment

value (RAV).

Conduct air mission brief.

Supervise and

Refine

Update mission tasking status. Coordinate

changes with supported

unit(s)/agency(ies). Verify mission

objectives are accomplished.

Update system tasking status.

Conduct direct coordination with

supported unit.

2-40. NAI/TAI List. The list is compiled by the exploitation cell with the aid of the Shadow operators. The components

include—

• Name.

2 - 10

• Physical description to aid in acquisition.

• Location in eight-digit military grid reference system (MGRS).

• Mission statement.

• Desired endstate/effect.

• Reporting instructions.

LESSONS FROM THE FIELD

The Shadow can be employed autonomously or employed as part of a Manned-

Unmanned Reconnaissance Team (MURT). When employed autonomously, the

missions should be fully integrated into the S2 section for mission planning and control.

This is the most common current TTP as a result of limited integration of the Shadow

into the OH-58D teams. We suggest the Shadows that are employed entirely as a

member of a MURT should be fully integrated into the S3 section with standard S2

briefings before the mission. The MURT Shadow operators will prepare for the mission

the same as the OH-58D pilots.

FLIGHT PREPARATION

2-41. The MC receives a mission briefing and FRAGO from the commander or platoon leader, and prepares a tactical

flight plan. The MC builds a flight plan around mission requirements and coordinates airspace through the ADAM/BAE

cell or other AC2 organization.

POST MISSION ACTIONS

2-42. Accurate BDA is a key factor in determining mission success. BDA assessment focuses on target effects,

intelligence gathered, and what was/was not successful during the mission.

2-43. An after-action review (AAR) enables units to identify for themselves what happened, why it happened, and how

to sustain strengths and improve on weaknesses. The AAR—

• Reviews the mission as briefed.

• Determines what happened.

• Identifies actions to sustain and improve.

• Determines what should be done differently.

SUSTAINED OPERATIONS (FIGHTER MANAGEMENT)

2-44. AR 95-23 and local policy establish limits on crew duty days. The commander establishes an SOP governing

fighter management.

LESSONS FROM THE FIELD

The Shadow operators will fall under the CAB fighter management policy. The fighter

management is a program tailored specifically to preventing accidents due to chronic and

acute fatigue for aviation operations. We also suggest that heavy consideration should be

made to applying this same fighter management policy to the IBCT Shadow platoons as

a means of prolonging combat power and decreasing the mission downtime due to human

error.

RULES OF ENGAGEMENT

2-45. Rules of engagement (ROE) specify circumstances and limitations under which forces initiate and/or continue

combat engagement with other forces encountered. U.S. forces comply with command established ROE. Many factors

influence ROE; including national command policy, mission, operational environment, commander’s intent, and

international agreements regulating conduct. ROE recognize the inherent right of unit and individual self-defense.

Properly developed ROE are clear, situation dependent, reviewed for legal sufficiency, and included in training.

2-46. The Shadow Troop commander ensures that the IBCT Shadow Platoons receive the ROE training from the ARS.

The ROE training should be incorporated into the academic standardization training.

2 - 11

SUPPORTING FIRES

2-47. The supported unit frequently has access to indirect fires from a coordinated fires network. These complementary

fires may facilitate movement to the objective area through joint suppression of enemy air defenses, engage targets

bypassed by UA, or provide indirect fires on the objective. Knowing what and when FS is available are important

considerations during UAS mission planning and engagement area development. Efforts to coordinate joint fires for

actions on the objective could be critical toward success for interdiction operations. With the application of a laser

rangefinder/designator (LRF/D) on UAS mission equipment packages, coordination of supporting fires will become a

routine part of UAS pre-mission planning.

ADDITIONAL UNMANNED AIRCRAFT CONSIDERATIONS

ALTITUDE

2-49. Assignment of the UA operating altitude should balance the need for adequate sensor resolution, detection

avoidance, threat avoidance, and aircraft de-confliction. During winter months, the humidity and freezing level play a

large factor in choosing higher altitudes. Typically, the Shadow UAS looks for an altitude between 3,500’ and 7,000’ to

balance noise reduction, sensor resolution, and aircraft de-confliction.

AIRSPEED

2-50. UAS planners must consider the impact of UAS low airspeeds. Low airspeeds result in increased loiter time, but

limit the commander’s flexibility to dynamically re-task the system across long distances. The Shadow can increase

speed to 100 KIAS in order to reach a target area in shorter time, but caution must be used in regards to decreased station

time and increased engine temperatures.

UNMANNED AIRCRAFT SYSTEM SURVIVABILITY

2-51. TUAS internal combustion propulsion systems create a distinctive noise signature. TUAS operating at mission

altitude may be detected from the ground. Mission planners must consider this aural signature when deciding which

UAS conducts a mission.

2-52. TUAS create a limited visual signature when operating at mission altitude. They have a relatively small IR

signature, making them less vulnerable to surface-to-air and air-to-air defense systems engagement. They are susceptible

to radar-guided anti-aircraft artillery, man-portable systems, and small-arms fire. Their vulnerability is decreased by

tactics that recognize these limitations (loitering for short periods over a particular location).

PRECISION TARGETING

2-53. The Shadow POP-300 L/D provides 10-digit UTM grid coordinates for use by the ground commander. The L/D

also provides coded-laser energy for remote Hellfire engagements fired from other aircraft.

ONE SYSTEM REMOTE VIDEO TERMINAL

2-54. OSRVT is a small, portable receiver and display system integrating live video and telemetry data from an array of

UAS (MQ-1C, Shadow, Predator, Raven, Pioneer, and Hunter) and manned aircraft using Lightning Pod. The Shadow

video feed to the OSRVT includes embedded geo-location information. This data provides map-referenced icons and

symbology to the user. The OSRVT receives only LOS feed from the UA. It does not receive SAR/GMTI imagery.

Projected OSRVT fielding includes units at all echelons, from corps to company level. The OSRVT provides targeting

information directly to the unit’s organic and direct support heavy weapons, as well as supporting artillery and close air

support (CAS) assets. Current OSRVT capabilities are limited to video downlink from the supporting UA. Planned

improvements to OSRVT include software upgrades that support LOI 1 through LOI 3.

2-55. Future OSRVT capability will provide supported units with the ability to directly control the UA sensor. The

Shadow communications relay package provides a direct link between the supported unit and the OSGCS operator

significantly improving ―sensor to shooter‖ response time.

UNMANNED AIRCRAFT SYSTEM REQUEST PROCEDURES

PREPLANNED

2 - 12

2-56. Pre-planned requests are received prior to the new ATO execution cycle. UAS support should be requested in the

same manner as manned aviation (figure 2-10). TUAS support appears on the ATO/ACO. Unfilled UAS requests are

forwarded to the next echelon for consideration and tasking. Airspace coordination parallels the request process to ensure

a comprehensive air picture. After the ATO is published (typically 12 hours prior to its execution), UAS requests are

processed as immediate requests.

Figure 2-10. Pre-planned request procedures

IMMEDIATE

2-57. Typically, immediate requests are submitted outside the normal ATO cycle. Immediate requests are expedited

through multiple-use internet relay chat, email, telephone, or radio, as required. The G-3 forwards unfilled requests if

organic assets are not available.

DYNAMIC RETASKING

2-58. Dynamic retaskings divert a UA from an existing mission to a new target. Dynamic retasking requires a rapid

decision based on previously published criteria. Clearly defined priorities must be published to facilitate effective

coordination of an emerging tactical situation (TIC or high pay-off target [HPT]). The re-tasking authority will be the

same as a re-tasking for an SWT in the ARS. Depending on the operation, the ARS Battle Staff Officer will request

immediate re-tasking for Shadow TUAS through the Brigade and supported units based on pre-briefed criteria. Upon

completion of dynamic retasking, the UA resumes the preplanned mission. The minimum information required to begin

dynamic re-task planning includes—

• Priority of use.

• Call sign.

• Routing.

2 - 13

• ACMs.

• Required altitude.

• Weapons considerations.

IMMEDIATE CRP REQUEST

2-59. Units can push the Shadow internal frequency and communicate directly to the Shadow operator for use of the

communications relay package. The limiting factor is the loaded frequency list. The Harris radios have no method of

changing channel in flight. Therefore, all Battalion TOC frequencies should be loaded on a common mission set. Units

will have the ability at any time to relay through the Shadow’s Harris radios back to their battalion headquarters.

Mission Change Contingency Planning

2-60. Mission change after launch is possible with TUAS, due to their long duration flight characteristics and the nature

of RSTA operations. UAS planners and supported units should prepare by creating contingency plans and ensuring

appropriate airspace, mission, and operational coordination is considered. Contingency planning may be necessary due

to:

• Changes in the AO or dynamics of the operation.

• Changes to commander’s scheme of maneuver or timeline.

• L/R area or mission-area weather.

• Airspace deconfliction.

2-61. A mission change during flight requires the UAS MC to validate the request/requirement based on:

• Asset availability and capability (remaining station time and/or on-board munitions).

• Time sensitive/criticality (En route time).

• Impact on current mission (Current mission priority).

• Airspace coordination/deconfliction.

• C2 support available.

2-62. The Shadow Troop briefs the supported commander/staff on the mission and considerations, and then presents a

tentative plan detailing the change.

AIRSPACE CONTROL

2-63. Airspace deconfliction is a major consideration during any UAS operation. Airspace control prevents mutual

interference for all users of the airspace; facilitates AD identification; and accommodates the safe flow of all air traffic.

Airspace control increases combat effectiveness by promoting safe, efficient, and flexible use of airspace with a

minimum of restraint placed on friendly airspace users. Airspace control includes coordinating, integrating, and

regulating airspace through positive and procedural controls to increase effectiveness at all levels of war. UAS pose a

significant challenge due to their small size, agility, and increasing density, as well as their limited ability to detect, see,

and avoid other aircraft. Detailed airspace C2 considerations are addressed in appendix B of FM 3-04.155.

2-64. Basic techniques for deconflicting UAS operations are—

• Altitude separation.

• Geographical separation, typically by keeping the UA to one side of a feature such as a road or river.

• Time separation or moving the UA out of the objective area before aircraft or ordnance arrives.

• A ROZ or track that confines the UA to a specific region of the airspace.

• Separation through the use of a common grid reference system (CGRS) and key pads.

• Kill boxes.

2-65. The number of UAS in the operational environment will grow each year. Planned airspace for UAS must be

included in the ACO, and UAS requirements should be part of the theater airspace control plan. All UAS missions must

be coordinated with the appropriate C2 agency prior to launch, ensuring effective integration and deconfliction with

other airspace users. UAS missions should be coordinated with the Airspace Control Authority (ACA), area air defense

commander, and joint force air component commander (JFACC) to separate UA safely from manned aircraft and to

prevent engagement by friendly AD systems.

2-66. Some UAS are equipped with a CRP that enables direct communication between the UAS operator and the

controlling airspace agency. For UAS not equipped with this direct communication capability, procedural ACMs are a

2 - 14

critical planning consideration. UAS missions; changes in L/R site locations; UA altitudes; operating areas;

identification, friend, or foe (IFF) squawks; and check-in frequencies are reflected in the daily ATO, ACO, or special

instructions (SPINS) and disseminated to appropriate aviation and ground units.

2-67. Planners monitor current UAS airspace requirements to anticipate future airspace requirements based on the

emerging tactical situation. Changes in allocation of CAS, artillery, Army aviation, and the dynamic retasking of UAS

will cause conflicts in airspace use. To address these changes, the supported unit should have a periodic AC2 meeting

with all key personnel involved (BAE, S-3, fire support coordinator, air liaison officer) to address these issues.

LESSONS FROM THE FIELD

The differences between types of control may allow much more freedom to the Shadow

operators in a combat environment. Generally, they stay under positive control above the

coordinating altitude. However, a MURT may be able to maintain positive control of all

three aircraft (two OH-58Ds and one Shadow) while maintaining one set of radio

transmissions to flight following. Additionally, the Shadow would be able to descend

below the coordinating altitude for better target acquisition in this scenario.

SECTION III – COMMUNICATION .

2-68. Fundamental to combat operations is combat information reporting and exploiting. This information and the

opportunities it presents are of interest to other maneuver units and higher headquarters staffs. Combat information

reporting requires wide and rapid dissemination. Battalion elements frequently operate over long distances, wide fronts,

and extended depths from their controlling headquarters. The Army communication system consists of three layers;

terrestrial, aerial, and space-based systems.

2-69. The terrestrial layer includes the effects of terrain and environment. When LOS is interrupted between individual

systems and units, terrestrial relays are used. Terrestrial relays are limited in their application due to their pre-planning

requirements, immobility, need for physical security, and inability to be rapidly shifted in dynamic situations. In

addition, these relays are LOS systems, and are limited in complex terrain and at extended distances. There are

operational situations in which additional terrestrial relays are at increased risk, especially well forward in the area of

operations. As unit areas of operation increase, the terrestrial layer becomes increasingly fragmented and both

connectivity and capacity suffer.

2-70. The aerial layer is intended to be very responsive and can reduce the workload otherwise placed on the other

layers. On-station or on-call aerial relays provide the commander tremendous flexibility to respond to the tactical

situation. Aerial relays can transcend LOS challenges except in the most complex terrain. Even then, aerial relays

provide enhanced connectivity over other options. Weather and enemy air defenses can limit aerial relay capability, and

complicate flight safety and AC2.

2-71. The Shadow Troop plays an integral role in supporting the aerial communication at the tactical level. While other

assets manage the complex operational and strategic communication through space-based communication, the Shadow

has the ability to provide platoon and company level operations the ability to support communications over increased

distances. Through the standard Shadow request procedures, units have the ability to augment their terrestrial

communication network with aerial capabilities for limited duration during key operations.

LESSONS FROM THE FIELD

We maintained the communications relay net during any mission, regardless of routine

ISR target decks conducted over mIRC or specific ground liaison missions. We did this

to force the Shadow operators more practice in radio communications, as well as to

provide a consistent emergency communications relay network in the event of isolated

personnel.

COMMUNICATION INTEGRATION

2-72. OSGCS receive, process, and prepare imagery information from UA conducting operations. Dissemination of the

sensor data and other payloads relies on a variety of systems. The specific dissemination method for UAS sensor data is

2 - 15

contingent upon the UAS being employed, supported unit capabilities, and other theater considerations. For example, the

flow of UAS data may be significantly limited due to network constraints during initial entry operations when compared

to the networks in a mature theater. Additionally, the wide spread introduction of OSRVT will increase the availability of

UAS sensor data across the force. Although voice communications systems are handy for quick coordination, the secret

internet protocol router network has proven to be the system of choice for passing mission requests, targets, and mission

summaries. OSGCS use local area network (LAN) cable for internal ground communications and SINCGARS, and

mobile subscriber equipment (MSE) for external communications on the battlefield.

Decisions regarding methods used to pass mission payload data should reflect the quality required, distances, availability

and priority of communication assets, and capabilities and locations of transmitter and receiver systems. The options may

include—

• Microwave.

• OSRVT (must remain within UA distance parameters).

• T-1 line.

• Secret internet protocol router/non-secure internet protocol router LAN lines (high band width).

• Cable from second UAS control station.

• SATCOM (GBS).

STANDARDIZED COMMUNICATION

2-73. Clear, standardized communications procedures are critical to mission success and safety of ground forces

operating in the vicinity of UAS operations. Table 2-3 lists terms that help standardize communication with the OSGCS

operators.

LESSONS FROM THE FIELD

Standardized communication is a point of friction in the Shadow community, which

results from lack of voice communication with the ground assets or manned aviation to

date. As mentioned, to combat this, we maintained the communications relay throughout

the breadth of their mission. In addition, our standardization officer worked with the

operators to practice standard communications and ―target talk-on‖s. Beyond this, we

suggest the integration of the Shadow operators fully into aviator academics to continue

the unit specific communications standards.

Table 2-3.

Terminology Term

Meaning

Zoom (in/out)

Change the sensor’s field of view (FOV).

Switch polarity

Change the IR camera from white hot to black hot or vice versa.

Capture

The object of interest has been located and is being tracked.

Terms to change the sensor orientation, leave the UA flight path unchanged

Pan (left/right/up/down)

Move the sensor as indicated relative to the current image.

Slew (to position)

Move the sensor to the indicated position.

Reverse (to object)

Reverse the panning direction to an object previously seen.

Monitor (object)

Keep the indicated object in the sensor’s FOV.

Terms to change the UA flight path, leave the sensor unchanged

Move (to location)

Reposition the UA to the indicated location.

Terms to change both the UA flight path and the sensor

Look (at location)

Reposition the UA and sensor as necessary to provide coverage of the

indicated location.

Track (object)

Reposition the UA and sensor as necessary to keep the indicated object in the

sensor’s FOV.

FREQUENCY MANAGEMENT

2-74. UAS employment requires frequency management and coordination specific to the AO. TUAS operations are

susceptible to interference from military and civilian communications systems. Terrestrial microwave systems using high

energy directional antennas (MSE and tropospheric systems employed by Army and Marine units) may cause significant

frequency interference problems and should be avoided.

2-75. Requesting frequencies through the division staff will assist in proper frequency management.

2 - 16

IMPROVISED EXPLOSIVE DEVICE JAMMERS

2-76. IED jammers are designed to interfere with radio devices commonly used to detonate IED. Certain IED jammers

may interfere with the UAS uplink. These jammers can be tuned to deconflict with UAS frequencies. The following are

guidelines for UAS operations in an IED jamming environment:

• See the signal officer regarding active IED jammers in the AO.

• Do not fly within a 300 meter radius or over a known IED jammer.

• Ask unit frequency managers (S-6) for assistance in reporting IED jammers that interfere with the UAS.

DATA LINK INTERFERENCE AND JAMMING

2-77. UAS data links are susceptible to both interference and jamming. Interference can occur when two or more UAS

are operating in close proximity on the same frequency (one unit may inadvertently control another unit’s UA if

operating on or near the same frequency).

2-78. High power transmitters or jammers in a UAS data link frequency range can jam the data link and cause lost link

with the UA. Frequency managers can eliminate these problems by providing a sufficient buffer between frequencies and

appropriate distances between terminals.

UNMANNED AIRCRAFT LOST LINK

2-79. Improper planning, overlapping OSGCS or GCS coverage, or poor frequency management can result in a UA

experiencing lost link with the controlling station. This mode causes the UA to follow a preplanned route at a

programmed altitude and proceed to a lost link point where control may be established or the UA returns to its home

base.

2-80. The UA ―lost link‖ flight plan defines the route the UA will travel if communications are lost between the UA and

controlling OSGCS.

RADIO LINKS AND NETS

2-81. The unit operates and transmits or receives information on the following external nets:

• Brigade/battalion intelligence net. Used primarily to share threat and friendly information. All routine and

recurring reports are transmitted on this net.

• Brigade/battalion command net. Used to pass C2 information from one commander to another.

• Administrative and logistics net. Used to exchange logistical information and unit status reports, as required.

• Company command net. Used to pass C2 information and critical reports within the company.

TACTICAL COMMON DATA LINK

2-82. The TCDL is a lightweight, low-cost common data link designed to be jam resistant and provide a high-bandwidth

(10.71 megabits-per-second [Mbps] and above) pipe for transmitting sensor data from UA to their associated ground

terminals.

2-83. TCDL will support air-to-surface transmission of radar, imagery, video, and other sensor information at data rates

of up to 274 Mbps at ranges of up to 200 kilometers. The programmable features of the TCDL design will enable

maximum flexibility in the data, while still allowing the system to interface with legacy systems already in use by

Department of Defense (DOD).

COMMUNICATION RELAY

2-84. A large battlefield area typically strains communications systems overextended by lost LOS, lack of nodes,

jamming, or inadequate range due to friendly force dispersion. The TUAS’ CRP helps maintain communications

between commanders and subordinate units by providing an aerial capability to extend communications.

3 - 1

Chapter 3

Employment

The teaming of an OH-58D scout helicopter with an RQ-7B Shadow TUAS in the Attack Reconnaissance Squadron is the

next level of scout reconnaissance operations. Historically, the OH-58D was fielded with a ―Mast Mounted Sight‖ in order to

clear enemy territory without fully unmasking the aircraft. With the use of the Shadow TUAS, the OH-58D pilot can remain

one or more terrain features from the enemy territory prior to bounding forward.

The Shadow will effectively replace the Mast Mounted Sight on the legacy scout helicopter. The OH-58F teamed

with an RQ-7B Shadow TUAS will be the most lethal combination of aero-scout capabilities to date.

SECTION I – MISSIONS .

OVERVIEW

3-1. The Shadow TUAS is employed as a tactical RSTA platform supporting the ARS commander’s scheme of

maneuver and intelligence requirements. TUAS missions are reconnaissance, surveillance, security, attack (close combat

and interdiction attack [IA]), and C2 support (communications relay). UAS support the achievement of information