Proposition 47 in Riverside

and San Bernardino Counties

The Number of Individuals With Four or More

Convictions Increased, as Did Theft Convictions

Among the Same Group

July

REPORT

For questions regarding the contents of this report, please contact our Communications Office at ..

This report is also available online at www.auditor.ca.gov | Alternative format reports available upon request | Permission is granted to reproduce reports

Capitol Mall, Suite | Sacramento | CA |

CALIFORNIA STATE AUDITOR

.. | TTY ..

...

For complaints of state employee misconduct,

contact us through the Whistleblower Hotline:

Don’t want to miss any of our reports? Subscribe to our email list at

auditor.ca.gov

621 Capitol Mall, Suite 1200 | Sacramento, CA 95814 | 916.445.0255 | 916.327.0019 fax | www.auditor.ca.gov

Mike Tilden Chief Deputy

Grant Parks State Auditor

July ,

2023‑107

e Governor of California

President pro Tempore of the Senate

Speaker of the Assembly

State Capitol

Sacramento, California

Dear Governor and Legislative Leaders:

As directed by the Joint Legislative Audit Committee, my office conducted an audit of the

effects of Proposition in San Bernardino and Riverside counties. Our assessment focused

on a selection of three law enforcement agencies from the two counties and a review of

twostatisticallyvalid samples of individuals convicted of offenses that were later reclassified by

Proposition offenses—one from and one from . Our statistical analyses were limited

to the jurisdictions of these three law enforcement agencies.

We reviewed three indicators—public calls for service, law enforcement response times, and

arrests—to assess the impact that Proposition had on San Bernardino and Riverside counties.

We did not identify any conclusive trends in calls for service or response times. However, we

found that all three agencies arrested fewer individuals for Proposition offenses—between

percent and percent fewer—in the period following the implementation of the proposition.

An analysis of our samples indicates that rates of recidivism—conviction of a new felony or

misdemeanor committed within three years of a previous conviction—in the two counties

generally decreased after the implementation of Proposition . However, the number of

individualswho were convicted four or more times increased by percentage points. In addition,

theft convictions among those who reoffended four or more times increased by percentage

points after the implementation of Proposition . e law enforcement agencies we reviewed

asserted that reduced sentences are driving the increase in individuals committing multiple

offenses in general and multiple theft offenses in particular.

We also found that Proposition is likely fulfilling one of its intended purposes by contributing

toreducing the length of incarceration for those who have committed certain nonviolent crimes.

An analysis of our samples shows that the average sentence length for Proposition offenses

decreased by more than percent after the proposition’s implementation. We recommend

that the Legislature consider the adoption of either or both of the following policy mechanisms:

appropriating additional funds for services that eliminate the root causes of recidivism or

increasing penalties for individuals who are convicted of four or more repeat offenses.

Respectfully submitted,

GRANT PARKS

California State Auditor

Selected Abbreviations Used in This Report

ACLU American Civil Liberties Union

BSCC Board of State and Community Corrections

CAD computer-aided dispatch

CDCR California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation

CDI California Department of Insurance

DOJ Department of Justice

Riverside DA Riverside County District Attorney’s Office

RMS record management system

iv CALIFORNIA STATE AUDITOR

July 2024

|

Report 2023-107

Contents

Summary 1

Introduction 3

Audit Results

The Law Enforcement Data We Reviewed Do Not Clearly

DemonstrateWhetherProposition 47 Significantly Affected

ThreeCrimeIndicators 9

Following the Implementation of Proposition 47, the Numberof

IndividualsWhoReoffended With Four or More Convictions

IncreasedattheThree Law Enforcement Agencies We Reviewed 15

Our Review Indicates That Proposition 47 Has Achieved Some

ofItsIntendedPurposes 19

California Has Several Options for Addressing the Increases in

MultipleReoffenses and Theft 21

Recommendations 22

Other Areas Reviewed 23

Appendix A

Volume of Service Calls for Alleged Proposition 47 Offenses

by Crime Category 25

Appendix B

Number of Arrest Charges at Each Law Enforcement Agency for

AllegedProposition 47 Offenses by Crime Category 27

Appendix C

Recidivism Methodology 29

Appendix D

Scope and Methodology 31

Response to the Audit

Riverside Sheriff 33

California State Auditor’s Comments on the Response

From Riverside Sheriff 37

vCALIFORNIA STATE AUDITOR

Report 2023-107

|

July 2024

Blank page inserted for reproduction purposes only.

vi CALIFORNIA STATE AUDITOR

July 2024

|

Report 2023-107

SUMMARY

Key Findings and Recommendations

In California voters approved the Safe Neighborhoods and Schools Act

(Proposition) to ensure that the State would focus its prison spending on

violent and serious offenses; to maximize alternatives other than incarceration

for nonviolent crime;and to create savings that the State could invest in victim

services, prevention and support programs, and mental health and drug treatment.

To achieve these goals, Proposition reclassified certain theft, burglary, forgery,

and drug possession offenses (referred to in this report as Proposition offenses),

from potential felonies to misdemeanors. e Joint Legislative Audit Committee

(AuditCommittee) requested the California State Auditor to conduct an audit

of the effects of Proposition in SanBernardino and Riverside counties. e

audit, as requested, was limited in scope to the two counties, and the results of

our analysis should not be projected statewide. To address our audit objectives,

we reviewed a selection of three law enforcement agencies from SanBernardino

and Riverside counties and reviewed two statistically valid samples of individuals

convicted of offenses that were later reclassified by Proposition—one from

and one from .

Our review found the following:

• We reviewed three indicators—public calls for service, law enforcement

response times, and arrests—to assess the impact that Proposition had on

SanBernardino and Riverside counties. For the three law enforcement agencies we

reviewed, we did not identify any conclusive trends in calls for service or response

times either before or after the implementation of Proposition. However, we

found that all three agencies arrested fewer individuals for Proposition offenses

in the period following the implementation of the proposition. Specifically, our

analysis of data from the three law enforcement agencies found that following the

implementation of the proposition, arrests for Proposition offenses declined

between and percent, and arrests for all other offenses declined between

and percent depending on the agency.

• An analysis of two sample groups of individuals, one group convicted in

(prior to Proposition ) and another group in (after Proposition ),

indicates that rates of recidivism—conviction of a new felony or misdemeanor

committed within three years of a previous conviction—inthe two counties

generally decreased slightly after the implementation of Proposition. We refer to

recidivism throughout the report as reoffense. However, the number of individuals

who were convicted four or more times increased by percentage points. In

addition, theft convictions among those who reoffended four or more times

increased by percentage points after the implementation of Proposition. e

law enforcement agencies we reviewed asserted that reduced sentences are driving

the increase in individuals committing multiple offenses in general and multiple

theft offenses in particular.

1CALIFORNIA STATE AUDITOR

Report 2023-107

|

July 2024

• Proposition is likely fulfilling one of its intended purposes by contributing

to reducing the length of incarceration for certain nonviolent crimes. An

analysis of our two sample groups shows that the average sentence length for

Proposition offenses decreased by more than percent after the proposition’s

implementation. In addition, according to stakeholder groups advocating for

reforms to the criminal justice system, programs funded by Proposition savings

have decreased recidivism, homelessness, and unemployment among participants.

erefore, we recommend that the Legislature consider the adoption of either

or both of the following policy mechanisms: appropriating additional funds for

services that eliminate the root causes of recidivism and/or increasing penalties for

individuals who are convicted of four or more repeat offenses.

Agency Comments

Because we did not make recommendations to the three law enforcement agencies

we reviewed, we did not expect to receive written responses from them; however,

we did receive a response from the Riverside County Sheriff’s Office. It disagreed

with and mischaracterized some of our findings and conclusions. We excluded the

SanBernardino County Sheriff’s Department—the county’s largest law enforcement

agency—from our audit because the department experienced a ransomware attack in

the spring of that rendered much of its data unavailable.

2 CALIFORNIA STATE AUDITOR

July 2024

|

Report 2023-107

INTRODUCTION

Background

In California voters approved the Safe

Neighborhoods and Schools Act (Proposition) to

ensure that the State would focus its prison spending

on violent and serious offenses; to maximize the use of

alternatives other than prison for nonserious, nonviolent

crime; and to invest the savings realized as a result of the

proposition into victim services, prevention and support

programs in K– schools, and mental health and drug

treatment. e text box describes the main provisions of

Proposition.

Proposition47’s Reclassification of Offenses

Proposition reclassified certain theft, burglary, forgery

and drug possession offenses, which we refer to as

Proposition offenses, from felonies and wobblers—

a term commonly used to describe a crime that can

be charged as either a felony or a misdemeanor–to

misdemeanors. Felonies are crimes that are punishable

by death, imprisonment in state prison, or imprisonment

in a county jail for more than a year. Misdemeanors are

all other crimes except infractions.

1

epenalties for

misdemeanors are generally imprisonment in county

jail, fines, or both. Asentence of imprisonment for

misdemeanors is generally no more than months in

county jail but can sometimes be up to a year.

Before Proposition, individuals who committed

offenses that were later reclassified by Proposition

could receive felony punishments for those offenses.

Such individuals now generally receive misdemeanor

punishments. roughout this report, we separate

Proposition offenses into four categories: burglary,

theft, drug possession, and forgery.

2

We categorized

burglary and theft separately for the reasons we describe

in the text box. Figure provides examples of offenses

that Proposition reclassified.

1

Prosecutors and courts can choose to designate certain criminal offenses,

such as willfully violating promises to appear in court, disturbing the peace,

or driving without a valid license, as infractions. An infraction is not punishable

byimprisonment.

2

State law divides theft into two degrees: grand and petty. Grand theft can incur

more severe punishment than petty theft.

Proposition 47 Made Three Major Changes

1. It reclassified certain nonviolent offenses as misdemeanors

instead of felonies or wobblers (a term commonly used to

describe a crime that can be charged as either a felony or a

misdemeanor). These reclassified offenses include certain

types of theft and drug possession unless the defendant

has prior convictions for certain violent or serious crimes.

2. It authorized courts to resentence with misdemeanors those

individuals who were serving felony sentences for certain

nonviolent offenses. For these individuals, Proposition 47

required a thorough review of criminal history and a risk

assessment to ensure that these individuals did not pose a

risk to public safety. Proposition47 also authorized courts

to resentence individuals who had already served a felony

sentence for a Proposition 47 offense to designate that

offense as amisdemeanor.

3. It created the Safe Neighborhoods and Schools Fund

that allocates funds saved from the implementation

of Proposition 47 to mental health and substance

abuse treatment programs, support programs aimed

at improving outcomes for public school students, and

recovery services for crime victims.

Source: State law.

The Definition of Burglary

Versus the Definition of Theft

Burglary is generally defined as:

• Any person who enters certain enclosures such as a

house or commercial establishment with the intent to

commit theft or certain other offenses, such as arson or

assault with a deadly weapon, is guilty of burglary.

Prior to Proposition 47, burglary included:

• Entering a commercial establishment with the intent

to commit theft of property whose value does not

exceed$950.

Proposition 47 defined this type of burglary as shoplifting

and established it as a new misdemeanor crime.

Because shoplifting as it became defined is not a type of

burglary, and is similar to theft, we classify shoplifting as

theft in our Proposition 47 analysis. All other burglary crimes

remained categorized as burglary.

Source: State law.

3CALIFORNIA STATE AUDITOR

Report 2023-107

|

July 2024

Figure 1

Examples of Offenses That Proposition 47 Reclassified

Burglary

e

Forgery

Possession

Jonathon Doe $$$

Category

*

Offense Example

Pre-Proposition 47

Classification

Post-Proposition 47

Classification

Theft of property

worth $950 or less

from a store or shop.

Felony or

misdemeanor

burglary

Grand theft of

personal property

worth $950 or less.

Felony or

misdemeanor

theft

Misdemeanor

shoplifting

(which we

categorize as

theft for purposes

of our audit)

Misdemeanor

petty theft

Signing the name of

another individual

on a check worth

$950 or less with the

intent to defraud.

Felony or

misdemeanor

Misdemeanor

Possession of certain

controlled substances

for personal use

without a valid

prescription.

Felony or

misdemeanor

Misdemeanor

Source: State law.

Note: The figure provides examples of reclassified offenses, not a complete list of all reclassified offenses. In addition, if an

individual who has previously been convicted of certain severe crimes, such as murder, commits a Proposition 47 offense,

that new offense may still be charged as a felony.

* Refer to the text box on page 3 titled The Definition of Burglary Versus the Definition of Theft for an explanation of why we

separate the two types of offenses.

4 CALIFORNIA STATE AUDITOR

July 2024

|

Report 2023-107

The Safe Neighborhoods and Schools Fund

In addition to reclassifying certain crimes, Proposition created the Safe Neighborhoods

and Schools Fund. is fund contains the savings that accrue to the State from the

implementation of Proposition.

3

e California state controller disburses percent of

the fund to the California Board of State and Community Corrections (BSCC), percent

to the California Department of Education, and percent to the Victim Compensation

and Government Claims Board. e Department of Finance calculated that from fiscal

years – through –, the State saved an average of million per year

from the implementation of Proposition for transfer to the Safe Neighborhoods and

Schools Fund. All three of the agencies have reported using these funds to facilitate grant

programs; the grants are meant to help fund services, such as the management of trauma

recovery centers and the provision of mental health resources to people in the criminal

justice systemand survivors of violent crime.

Criminal Justice Processes Following the Implementation of Proposition47

State law allows a peace officer (officer) to arrest and hold an individual suspected of

a felony if the officer has probable cause. In contrast, officers generally must release

individuals arrested for misdemeanors after citing—writing a notice for them to appear

in court—or booking them. us, before the implementation of Proposition, a law

enforcement agency could choose to hold individuals suspected of Proposition

offenses after booking—fingerprinting and photographing a person to record an

arrest—because these offenses could be charged as felonies. Consequently, since the

implementation of Proposition, officers have generally been required to release

individuals suspected solely of committing Proposition offenses. However, the

officers can hold such individuals if a separate statutory reason exists to do so. For

example, a statute enacted in authorizes officers to hold individuals who have been

arrested or convicted of theft from a store in the previous six months or when there is

probable cause to believe individuals are guilty of organized retail theft.

4

Changes to State Law Have Reduced Pressures on California’s Prison and Jail Systems

Proposition is one of several changes to state law that have contributed to a reduction

in California’s incarcerated population. In the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that

California’s prison overcrowding violated the constitutional rights of incarcerated

individuals and required remedial action. Since that time, California voters have passed

several propositions that have contributed to reductions to incarcerated populations,

as the text box shows. For example, during fiscal year –, the California

Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation(CDCR) released over , individuals

who received resentencing from a court and were required to be released under

Proposition’sprovisions.

3

The director of Finance is responsible for calculating these savings and bases that calculation on the amount saved from

reduced prison use.

4

Organized retail theft became a criminal offense effective January , , several years after Proposition

wasimplemented.

5CALIFORNIA STATE AUDITOR

Report 2023-107

|

July 2024

In addition, to address overcrowding, state

prisons and some county jails have at times had to

release incarcerated individuals who committed

nonviolent offenses. For example, since the s,

Riverside County has operated under a federal

court order that requires the county to release

individuals from its jails or refuse to accept

individuals who have been recently arrested

whenever all the beds in its jail system are filled,

and allows the county to start refusing to accept

individuals once any jail or specific housing unit

has reached percent of its capacity. Riverside

County and other large counties in California have

released incarcerated individuals because of a lack

of bed capacity. Moreover, in April during

the COVID- pandemic, the Judicial Council

of California established emergency rules that

included setting bail for misdemeanor and felony

offenses at , with some exceptions. However, the

Judicial Council of California rescinded these rules

inJune .

Since the numbers of individuals in state

prisons and county jails have declined. We reviewed

data from the CDCR and the BSCC to analyze

changes in thepopulations of state prisons and

county jails from through . e factors discussed above and in the text box

likely contributed to a percent decline in the state prison population and a percent

decline in county jail populations, as Figure illustrates.

Our Review of Law Enforcement Agencies in Riverside and SanBernardino Counties

e Joint Legislative Audit Committee (Audit Committee) requested that we review

aselection of law enforcement agencies in SanBernardino and Riverside counties.

Weinitially selected two sheriff’s departments and two police departments based on

the number of sworn officers they employed. However, we removed the SanBernardino

County Sheriff’s Department—the county’s largest law enforcement agency—from

our selection during the course of the audit because the department experienced a

ransomware attack in the spring of that rendered much of its data unavailable. As

of May , the SanBernardino County Sheriff’s Department still did not have access

to some of the data that it lost because of this attack. We evaluated the data potentially

available at the statewide and local law enforcement level and found that local law

enforcement data contained additional information not captured in the statewide data.

erefore, we analyzed data from the three local law enforcement agencies we selected

for review. e audit was limited to the three law enforcement agencies in two counties,

and the results of our analysis should not be projected statewide. Table shows the

number of sworn officers employed by the remaining three law enforcement agencies

andthe populations of the communities they serve.

Other Propositions Contributed to

Reductions in the Number of Individuals

IncarceratedinCalifornia

• Proposition 36 (2012): Removed certain increases in

punishment from prison sentences for certain individuals

subject to the State’s existing three‑strikes law. It also

allowed certain individuals serving life sentences to apply

for reduced sentences.

• Proposition 57 (2016): Expanded eligibility for parole

consideration; increased the State’s authority to award

early release due to good behavior and rehabilitative or

educational achievements; and mandated that judges,

instead of prosecutors, determine whether youth should

be transferred from juvenile court to criminal court for

certain offenses.

• Proposition 64 (2016): Legalized specified personal use

and cultivation of marijuana for adults 21 years of age or

older, reduced criminal penalties for specified marijuana‑

related offenses for adults and youth, and authorized

resentencing or dismissal and sealing of eligible

marijuana‑related convictions.

Source: State law.

6 CALIFORNIA STATE AUDITOR

July 2024

|

Report 2023-107

Figure 2

State Prison and County Jail Populations Have Declined From January 2011 Through September 2023

COVID-19 pandemic

2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023*

0

20,000

40,000

60,000

80,000

100,000

120,000

140,000

160,000

Total prison in-custody

population as of December 31

in the given year

16%

36%

Total average daily

population for county jails

Source: CDCR; BSCC.

Note: The sharp decline in prison and jail populations from 2019 to 2020 coincided with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and relatedefforts,

such as reducing the number of individuals in prisons and jails.

* Jail Profile Survey for 2023 data consists of data from January 2023 through September 2023.

Table 1

Riverside and San Bernardino County Law Enforcement Agencies We Reviewed

SWORN

OFFICERS

AS OF

JULY2022

JURISDICTION

POPULATION

*

NEAREST

THOUSAND

OFFICERTO

RESIDENT

RATIO

Riverside County Sheriff’s Office

†

2,802 Riverside County 2,418,000 1:863

Riverside Police Department 349 City of Riverside 315,000 1:903

San Bernardino Police Department 253 City of San Bernardino 222,000 1:877

Source: U.S. Census, the Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training, and Riverside County Sheriff’s Office.

* Population amounts are from the 2020 decennial census.

†

According to a chief deputy at Riverside County Sheriff’s Office, sworn officers can include officers of various job designations, such as peace

officers, deputy coroners, and court deputies. The chief deputy further explained that as of May 2024, the office has 2,910 officers, of whom

1,680 are peace officers.

7CALIFORNIA STATE AUDITOR

Report 2023-107

|

July 2024

Blank page inserted for reproduction purposes only.

8 CALIFORNIA STATE AUDITOR

July 2024

|

Report 2023-107

AUDIT RESULTS

The Law Enforcement Data We Reviewed Do Not Clearly Demonstrate Whether

Proposition47 Significantly Affected Three Crime Indicators

To assess the impact of the implementation of Proposition on SanBernardino and

Riverside counties, we reviewed three indicators: calls for service, response times,

and arrests, as Figure shows. We did not identify any conclusive trends in calls for

service or response times across the law enforcement agencies that demonstrate that

the implementation of Proposition had a significant impact on these indicators.

However, we found that all three agencies arrested fewer individuals for Proposition

offenses in the period following the implementation of the proposition.

Figure 3

Proposition 47 Offenses Generally Followed Overall Trends When Compared to All Other

Offenses but Showed Steeper Changes for Certain Indicators

Police

Calls for Service

Trends in the volume

of service calls for

Proposition 47 offenses

generally aligned

with trends for other

service calls.

Response Times

The law enforcement

agencies’ response times

have increased for all

offenses, including those

related to Proposition 47.

Arrests

Arrests for all offenses

decreased, but arrests for

Proposition 47 offenses

decreased more after the

implementation of

Proposition 47.

Source: Analysis of computer-aided dispatch system and record management system data from Riverside County Sheriff’s

Office, Riverside Police Department, and SanBernardinoPolice Department.

Trends in the Volume of Service Calls for Proposition 47 Offenses Have Generally Aligned

With Trends for Other Service Calls

e three law enforcement agencies use computer-aided dispatch (CAD) systems

toreceive and log calls for service. ese calls include those that the public makes to

or to nonemergency lines for alleged criminal activities. We have included some

examples of calls for service in the textbox. In addition, the CAD systems log certain

other incidents, such as when an officer observes a crime in progress and reports

it from the field. We compared and analyzed the three agencies’ CAD-reported

activity, which we refer to as calls for service, for Proposition offenses and other

9CALIFORNIA STATE AUDITOR

Report 2023-107

|

July 2024

incidents from to for the Riverside Police

Department (RiversidePolice) and the Riverside

County Sheriff’s Office (Riverside Sheriff) and from

to for SanBernardino Police Department

(SanBernardino Police).

5

Calls for service for Proposition offenses—

including burglary, drug possession, forgery, and

theft—totaled about percent of all calls for service

at the three law enforcement agencies during the

periods we reviewed. However, theother trends

we identified differed amongthe three agencies, as

Figure shows. For example, calls for service for both call types decreased slightly at

Riverside Sheriff from to . Meanwhile, Riverside Police experienced increases

in both Proposition-related service calls and other service calls from to .

SanBernardino Police experienced an overall decrease incalls for service for both

call types from through ; however, there was a steeper percentage drop in

Proposition-related service calls compared to other service calls. Appendix A shows

the total number of Proposition-related service calls for each of four categories:

burglary, drug possession, forgery, and theft.

It is unclear from the data what effect, if any, Proposition has had on calls for

service. e three law enforcement agencies stated that the calls for service might not

reflect the actual number of Proposition offenses occurring because the community

may be underreporting those offenses. For example, a captain at SanBernardino

Police, a lieutenant at Riverside Police, and a deputy at Riverside Sheriff asserted that

businesses are less likely to call the police to report thefts because even when they do

so, the same individuals often return the next day to reoffend. Nevertheless, all three

acknowledged that their perspective was largely based on anecdotal evidence and did

not provide evidence to substantiate that it was occurring. We contacted the California

Retailer’s Association to determine whether it compiles information on theft from

its members. However, the association informed us it did not have any data on how

frequently retailers reported thefts to law enforcement.

The Law Enforcement Agencies’ Response Times Have Increased for All Offenses, Including

Those Related to Proposition 47

e three law enforcement agencies’ response times generally increased after the

implementation of Proposition. e CAD system for each law enforcement agency

logs the time it receives a call and the time that a responding officer arrives at the scene

of the alleged incident. When we analyzed the three agencies’ average response times

from to , we found that they increased for all service calls, including those for

Proposition offenses, as Figure shows. It is unclear from the data what effect, if any,

Proposition has had on response times because of other contributingfactors, such as

law enforcement agency staffing levels and the number of calls for service.

5

San Bernardino Police’s CAD data are only complete dating back to .

Examples of Service Calls

• A welfare check

• A hit‑and‑run

• A robbery

Source: Riverside Police, Riverside Sheriff, and San Bernardino

Police CAD systems.

10 CALIFORNIA STATE AUDITOR

July 2024

|

Report 2023-107

Figure 4

Calls for Service Trends Varied Across the Law Enforcement Agencies

2011 20122009 2010 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

Number of Calls for ServiceNumber of Calls for ServiceNumber of Calls for Service

0

100,000

200,000

300,000

400,000

500,000

600,000

700,000

800,000

900,000

1,000,000

0

50,000

100,000

150,000

200,000

250,000

300,000

0

50,000

100,000

150,000

200,000

250,000

300,000

350,000

400,000

Riverside Sheriff

Riverside Police

San Bernardino Police

*

4%

35%

15%

16%

5%

4%

Since 2014

2%

4%

Since 2014

Since 2014

Since 2014

6%

7%

50%

30%

Since 2014

Since 2014

2011 20122009 2010 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

2011 20122009 2010 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

Non-Proposition 47-Related Calls for Service

Proposition 47-Related Calls for Service

Source: Analysis of Riverside Sheriff, Riverside Police, and San Bernardino Police CAD systems.

Note: We calculated the percentage change in total calls for service before and after 2014.

* San Bernardino Police’s CAD data are only complete dating back to 2012.

11CALIFORNIA STATE AUDITOR

Report 2023-107

|

July 2024

Figure 5

Law Enforcement Agency Response Times Generally Increased for All Crimes Since 2009

Riverside Police

San Bernardino Police

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

0

50

100

150

200

250

Average Number of MinutesAverage Number of MinutesAverage Number of Minutes

*

Non-Proposition 47-Related Response Times

Proposition 47-Related Response Times

53%

43%

0%

84%

32%

18%

6%

43%

56%

39%

50%

50%

Since 2014

Since 2014

Since 2014

Since 2014

Since 2014

Since 2014

Riverside Sheriff

2011 20122009 2010 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

2011 20122009 2010 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

2011 20122009 2010 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

Source: Analysis of Riverside Sheriff, Riverside Police, and San Bernardino Police CAD systems.

Note: We calculated the percentage change in average response times before and after 2014.

* San Bernardino Police’s CAD data are only complete dating back to 2012.

12 CALIFORNIA STATE AUDITOR

July 2024

|

Report 2023-107

Riverside Police and SanBernardino Police explained that the increases in response

times were the result of reductions in staffing levels. For example, Riverside Police cited

challenges related to the recruitment and retention of officers. Research published in

by the Public Policy Institute of California shows that from to , Riverside

and SanBernardino counties had decreases in patrol officers per , residents

of percent and percent, respectively, which appears to corroborate the agencies’

assertions.

6

In addition, as Figure shows, the number of calls for service increased

at Riverside Police and generally remained stable at Riverside Sheriff at the same time

as the decrease in staffing, which may have affected the timeliness of their response.

Riverside Sheriff explained that response time results for its department could be skewed

by reclassifying crimes after a deputy arrives on the scene. Riverside Sheriff uses a

tieredpriority system to rank calls for service, with more serious crimes receiving highest

priority and lower-level crimes receiving lower priority. A deputy may respond to a call

for a higher-level crime, but then determine that a less serious crime took place and

reclassify the call after investigating. Nevertheless, response times generally increased

for both Proposition and non-Proposition related service calls and the explanation

given by Riverside Sheriff would not seem to affect the trends we identified.

The Number of Arrests for Proposition 47 Offenses Has Declined

e law enforcement agencies use a record management system (RMS) to document

arrests for criminal offenses. We analyzed their RMS data to determine their number

of arrests, which include citations and bookings, for Proposition offenses and

non-Proposition offenses from to for Riverside Police and Riverside

Sheriff and from to for SanBernardino Police.

7

We found that arrests for

Proposition offenses declined at all three agencies from through following

the implementation of Proposition, as Figure shows. For example, in

Riverside Sheriff made , arrests for Proposition offenses, while in it made

,arrests for Proposition offenses, a decline of percent. However, prior to the

implementation of Proposition, arrests for Proposition offenses slightly increased

for Riverside Police and SanBernardino Police. For Riverside Sheriff, the largest agency,

arrests for Proposition offenses had decreased prior to the implementation of

Proposition. Appendix B shows the percentage change in arrest charges at the three

agencies for each Proposition offense category.

ese decreases align with California Department of Justice (DOJ) reported trends in

total arrests statewide and in Riverside and SanBernardino counties over the same

period. Specifically, from through , Riverside and SanBernardino counties had

a decrease in all arrests of percent and percent respectively, and statewide levels

also fell by percent. Although we found a decrease in arrests that coincides with the

implementation of Proposition, our analysis does not provide a definite causative

explanation for the decrease. In the Public Policy Institute of California reported

that arrest trends can be affected by factors such as economic conditions, demographics,

crime rates, and the implementation of Proposition, among others.

6

Magnus Lofstrom, Brandon Martin, Andrew Skelton, “California’s Notable Declines in Law Enforcement Staffing,” February, .

7

San Bernardino Police’s RMS data are only complete dating back to .

13CALIFORNIA STATE AUDITOR

Report 2023-107

|

July 2024

Figure 6

Law Enforcement Agency Arrests for Proposition 47 Offenses Decreased Since the Implementation

ofProposition 47

Number of ArrestsNumber of ArrestsNumber of Arrests

0

10,000

20,000

30,000

40,000

50,000

60,000

70,000

80,000

0

1,000

2,000

3,000

4,000

5,000

6,000

7,000

8,000

9,000

0

1,000

2,000

3,000

4,000

5,000

6,000

7,000

8,000

9,000

10,000

11,000

12,000

Riverside Sheriff

49%

59%

50%

30%

14%

4%

1%

Riverside Police

San Bernardino Police

*

Since 2014

21%

Since 2014

Since 2014

15%

Since 2014

67%

60%

Since 2014

29%

Since 2014

2011 20122009 2010 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

2011 20122009 2010 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

2011 20122009 2010 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

Non-Proposition 47-Related Arrests

Proposition 47-Related Arrests

Source: Analysis of Riverside Sheriff, Riverside Police, and San Bernardino Police RMS data.

Note: We calculated the percentage change in total arrests before and after 2014.

* San Bernardino Police’s RMS data are only complete dating back to 2012.

14 CALIFORNIA STATE AUDITOR

July 2024

|

Report 2023-107

According to the agencies, there were likely a number of causes for the decline in

arrests for Proposition offenses. For example, a lieutenant with Riverside Police

explained that businesses now often report crimes days or weeks after they occur,

usually online. ese delays can hinder officers’ ability to make an arrest. e

assistant chief at SanBernardino Police provided a similar explanation. He also

explained that many retail businesses report online after the fact for insurance

purposes only. In addition to issues surrounding online reporting, the assistant

chief for the SanBernardino Police stated that generally, law enforcement agencies

dedicate available resources to consequential crimes that affect the community

and that the implementation of Proposition had a cooling effect on agencies’

devotion of scarce resources to Proposition offenses. A deputy with Riverside

Sheriff explained that calls for property crimes generally lack the evidence needed to

conduct a thorough investigation, and that contributes to less arrests.

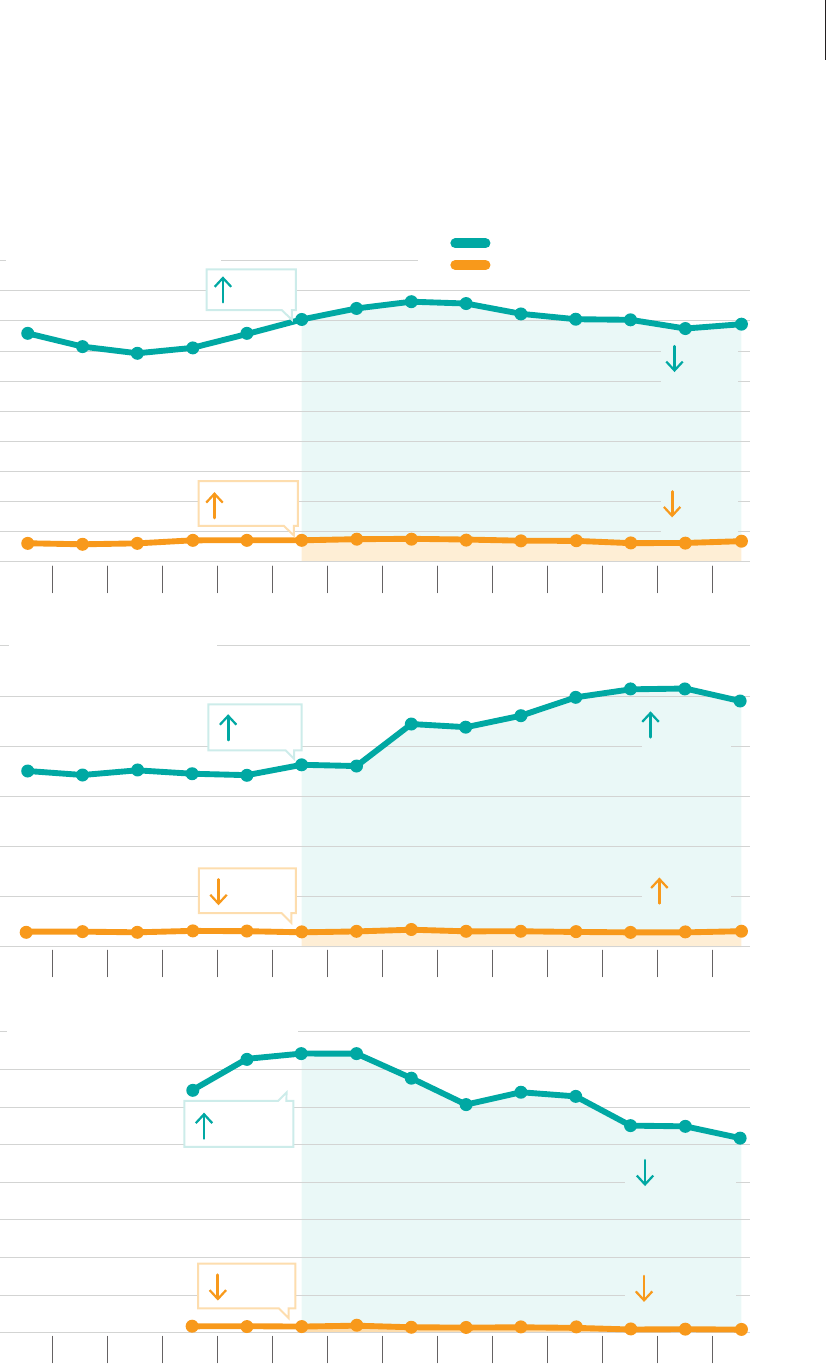

Following the Implementation of Proposition47, the Number of Individuals Who

Reoffended With Four or More Convictions Increased at the Three Law Enforcement

Agencies We Reviewed

When we reviewed publicly available case histories and court records for a statistical

sample of individuals convicted of a Proposition offense in and at the three

law enforcement agencies we reviewed, we found that overall rates of recidivism—

conviction of a new felony or misdemeanor committed within threeyears of a previous

conviction—declined slightly, as Figure shows. We refer to recidivism throughout

the report as reoffense. is decline generally aligns with CDCR’s measure of statewide

recidivism for its - group of percent and its – group of percent.

However, among those who reoffended in our sample at the three law enforcement

agencies we reviewed, our analysis found that there were more individuals with four or

more convictions, an increase of percentage points, following the implementation

of Proposition. Moreover, among this group of individuals, the frequency of theft

convictions increased after the implementation of Proposition.

The Number of Individuals Who Reoffended With Four or More Convictions Increased at the

Three Law Enforcement Agencies We Reviewed After the Implementation of Proposition 47

BSCC defines recidivism as conviction for a

new felony or misdemeanor committed within

three years of release for a previous criminal

conviction, as the text box describes. To

assess the rates of reoffense before and after

Proposition took effect, we reviewed court

records and publicly available case histories of

individuals convicted of Proposition offenses

at the three law enforcement agencies we

reviewed before and after its implementation.

Wethen consulted with a statistician to interpret

the results of our analysis.

Definition of Recidivism

Recidivism: Conviction for a new felony or misdemeanor

committed within three years of release from custody

orcommitted within three years of placement on

supervision for a previous criminal conviction.

This definition excludes cases dropped or dismissed,

noncriminal traffic offenses, and violations of supervision

(parole, probation, mandatory supervision, etc.).

Source: BSCC.

15CALIFORNIA STATE AUDITOR

Report 2023-107

|

July 2024

Figure 7

Although Overall Reoffense Rates Decreased at the Three Law Enforcement Agencies We Reviewed, the

Number of Individuals Who Reoffended With Four or More Convictions Increased

Individuals with

+ Convictions

31%

Individuals with

+ Convictions

43%

2011

Group

201

Group

Percentage

Point Change

The percentage of individuals

with four or more convictions

who reoffended increased

after Proposition 47.

Reoffense

60%

Reoffense

55%

The overall rate of

reoffense for individuals

convicted of Proposition 47

offenses decreased slightly

after Proposition 47.

Rate of Theft

Convictions

Rate of Theft

Convictions

The frequency of theft

convictions among those

with four or more convictions

increased after Proposition 47.

5%

12%

14%

25%25% 39%39%

Source: DOJ; analysis of Riverside Superior Court and San Bernardino Superior Court public documents and court records.

Note: Refer to Appendix C for a description of the methodology used to select our two sample groups of individuals convicted of

offenses that were later reclassified by Proposition 47 in 2011 and another group in 2016.

We compared a group of randomly selected individuals arrested by one of the three

law enforcement agencies we selected for review and subsequently convicted of a

Proposition offense in Riverside and SanBernardino counties in , before

the implementation of Proposition, to a group of randomly selected individuals

who were convictedof a Proposition offense in , after the proposition’s

implementation. Using public records from the respective county courts, we

determined whether the individuals in each group reoffended within three years of

their first conviction for a Proposition offense and, if so, how many subsequent

convictions they had within that period. We included non-Proposition offenses

when determining subsequent convictions. For example, someone who was convicted

of a Proposition offense involving drug possession might have reoffended with

16 CALIFORNIA STATE AUDITOR

July 2024

|

Report 2023-107

a conviction for a non-Proposition offense, such as driving under the influence or

battery. Overall, we analyzed the criminal records of individuals over a three-year

period. We describe the methodology we used for this analysis in detail in Appendix C.

e overall rates of reoffense in our samples before and after the implementation

of Proposition declined from percent to percent.

8

However, the number of

individuals in our sample with four or more convictions who reoffended increased, as

Table shows.

9

ese results suggest that although individuals who were convicted of

Proposition offenses generally reoffended less frequently in the later sample, a subset

of this group committed more offenses. Although we identified a significant difference

of percentage points between the two groups among individuals with four or more

convictions, we only identified slight variations— percentage points or less—among

individuals in the two groups with less than four convictions. If we project these sample

results to the population of the three law enforcement agencies’ jurisdictions, we estimate

that about more individuals may have reoffended with four or more convictions after

the implementation of Proposition than did so before its implementation.

10

Table 2

The Overall Rate of Reoffenses Decreased, but the Percentage of Those Who Reoffended With Four or

More Convictions Increased

Overall Reoense Rate

GROUP SAMPLE SIZE

NUMBER OF

INDIVIDUALS WHO

REOFFENDED

PERCENTAGE OF

INDIVIDUALS WHO

REOFFENDED

PERCENTAGE

POINT

CHANGE

2011 sample (pre-Proposition 47) 107* 64 60%

5% ↓

2016 sample (post-Proposition 47) 114 63 55%

Individuals Who Reoended With Four or More Convictions

GROUP

NUMBER OF

INDIVIDUALS

IN SAMPLE

WHO

REOFFENDED

NUMBER OF

INDIVIDUALS IN

SAMPLE WITH

FOUR OR MORE

CONVICTIONS

PERCENTAGE OF

INDIVIDUALS WHO

REOFFENDED WITH

FOUR OR MORE

CONVICTIONS

PERCENTAGE

POINT

CHANGE

2011 group (pre-Proposition 47) 64 20 31%

12% ↑

2016 group (post-Proposition 47) 63 27 43%

Source: Analysis of court records and publicly available case histories from San Bernardino and Riverside County.

* The sample size for this group was 113, but Riverside Superior Court attested it destroyed the records for six individuals in our

sample pursuant to record retention law.

8

Our results for the overall rates of reoffense were not found to be statistically significant.

9

Our results for those with four or more convictions were determined to be statistically significant at an percent confidence

level. However, studies by the U.S. Department of Justice Bureau of Justice Statistics use a percent confidence level for

determining significance. For more information regarding statistical significance, refer to Appendix C.

10

For our cohort, the lower limit is and the upper limit is , with a best estimate of . For our cohort, the lower

limit is and the upper limit is ,, with a best estimate of .

17CALIFORNIA STATE AUDITOR

Report 2023-107

|

July 2024

In an effort to substantiate our recidivism analysis, we analyzed Riverside Sheriff’s

RMS to determine how many individuals it arrested four or more times in each year

during the audit period. We found that the average number of individuals it arrested

four or more times for Proposition offenses in a year more than doubled following

the implementation of Proposition, from before Proposition to after

Proposition. Although not all arrests lead to a conviction, these data support our

recidivism analysis finding that a subset of individuals were convicted ofcommitting

more offenses after the implementation of Proposition.

The Frequency of Theft Convictions at the Three Law Enforcement Agencies We Reviewed

Increased After the Implementation of Proposition 47, Particularly for Those Who Reoffended

With Four or More Convictions

e frequency of theft convictions and—more specifically—of theft convictions

among those who reoffended with four or more convictions increased at the three

law enforcement agencies we reviewed after the implementation of Proposition.

eft convictions in our sample were percentage points higher than theft

convictions in our sample. More significantly, theft convictions among

the subset of individuals who reoffended with four or more convictions rose by

percentage points. is increase was higher than the increases for any other

Proposition offense categories, as Table shows.

11

For example, we identified an

individual in our sample who was convicted for seven theft-related offenses after the

implementation of Proposition. is individual was convicted three times within

three months and then four more times within the next three years. All of these were

misdemeanor convictions.

e law enforcement agencies asserted that the reduced consequences for

Proposition offenses may have caused the increase in the frequency of theft cases

in our samples. For example, before Proposition, petty theft could be punished as

a felony if a person had three prior theft convictions; however, after Proposition,

petty theft with a prior theft conviction is a misdemeanor except in very limited

circumstances. A deputy with Riverside Sheriff and an assistant chief with

SanBernardino Police stated that they believe Proposition created an incentive

for individuals to commit multiple offenses by reducing the consequences for repeat

offenses. To assess whether the data indicated a decrease in sentencing length, we

analyzed the average sentence length for individuals in our sample groups convicted

of a Proposition offense, which we discuss in the next section.

11

Our results were determined to be statistically significant at an percent confidence level. However, studies by the

U.S.Department of Justice Bureau of Justice Statistics use a percent confidence level for determining significance.

Formore information regarding statistical significance, refer to Appendix C.

18 CALIFORNIA STATE AUDITOR

July 2024

|

Report 2023-107

Table 3

Theft Convictions for Individuals Who Reoffended With Four or More Convictions Increased

MoreThan Convictions in Other Proposition 47 Categories

Frequency of Proposition 47 Convictions for ose With Four or More Convictions

OFFENSE 2011 GROUP PERCENTAGE* 2016 GROUP PERCENTAGE

PERCENTAGE POINT

CHANGE

Theft

25% 39% 14% ↑

Drug possession

60 51 9% ↓

Burglary

15 6 9% ↓

Forgery

0 4 4% ↑

Source: Analysis of court records and publicly available case histories from San Bernardino and Riverside counties.

Note: Our recidivism analysis captured all convictions an individual had, as we explained in the previous section. However,

the results above exclude non-Proposition 47 convictions.

* For our 2011 sample group, convictions for what is now known as shoplifting may fall into either our Theft or Burglary

category. Prior to Proposition 47, the theft of property worth $950 or less from a commercial establishment could be

charged as a felony. After the passage of Proposition 47, this crime became misdemeanor shoplifting. Also, after the

passage of Proposition 47, individuals previously convicted of the theft of property worth $950 or less could petition to

have their felony sentences retroactively converted to misdemeanors. This led to instances of shoplifting appearing for

individuals in our 2011 sample group which we then included in our Theft category, even though the shoplifting penal

code did not exist before 2014. If an individual from the 2011 sample group did not receive a change in sentence to

misdemeanor shoplifting, their felony burglary conviction would still be captured under our Burglary category.

Our Review Indicates That Proposition47 Has Achieved Some of Its Intended Purposes

When we analyzed court records to determine the average sentence length for

Proposition offenses in our sample population, we found that the length of

sentences had decreased at the three law enforcement agencies we reviewed after the

implementation of Proposition, in line with the law’s intended purpose. Specifically,

following the law’s implementation, the average sentences individuals in our samples

received for Proposition offenses decreased by more than percent. is drop was

likely the result of reductions in sentences for theft and drug possession offenses, as

Table shows. Proposition reclassified certain theft and drug possession offenses from

felonies or wobblers to misdemeanors, the latter of which calls for shorter jailsentences.

12

e Riverside County District Attorney’s Office (Riverside DA) agreed that Proposition

has definitely achieved its intended goal of reducing prison sentences for Proposition

offenses. Nevertheless, the Riverside DA attested that it believes there have been

several unintended negative consequences, including an increase in organized retail

theft offenses. We discuss arrests for organized retail theft later in this report.

13

12

The average length of time served was days in jail for our group. Of the records we reviewed for Proposition

offenses in which an individual was sentenced to jail time, the main reasons individuals did not spend the full sentenced

time in jail included court orders to alleviate overcrowding, work release programs, and good behavior credits. However,

Proposition did not amend or alter these reasons.

13

Organized retail theft became a criminal offense effective January , , several years after Proposition was implemented.

19CALIFORNIA STATE AUDITOR

Report 2023-107

|

July 2024

Table 4

The Average Sentence Length for a Proposition 47 Conviction Decreased After Its Implementation

Sentencing for Proposition 47 Oenses

AVERAGE NUMBER OF DAYS SENTENCED

GROUP

ALL PROPOSITION 47

CONVICTIONS

THEFT CONVICTIONS

DRUG POSSESSION

CONVICTIONS

FORGERY

CONVICTIONS

BURGLARY

CONVICTIONS

2011 Sample

(pre-Proposition 47)

349 days 335 days 429 days 90 days 268 days

2016 Sample

(post-Proposition 47)

199 days 207 days 96 days 90 days 603 days

Percentage change 43% ↓ 38% ↓ 78% ↓ 0% 125% ↑

Source: Analysis of court records and publicly available case histories from San Bernardino and Riverside counties.

Organizations that advocate for reforms to the criminal justice system also provided

their perspective on Proposition’s effects. When we spoke to entities such as the

American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California (ACLU SoCal), the Ella Baker

Center for Human Rights, Californians for Safety and Justice, and Legal Services

for Prisoners with Children, they cited studies that have shown the positive effects

Proposition has had on California. For example, the BSCC performed a statewide

evaluation of its Proposition grant program and found that recidivism among

participants enrolled in services funded by the savings associated with Proposition

was lower than other reported statewide recidivism estimates.

14

Specifically,

participants had a percent rate of recidivism after enrolling in a grant program,

while statewide recidivism estimates were between and percent.

15

is BSCC

study also found a percent decrease in homelessness and a percent decrease in

unemployment among participants who received the Proposition-funded services

and identified housing or employment as goals of their participation. In another

example, the National Institute of Justice gave a Promising rating to the policy reform

enacted by Proposition, which implies that the policy reform is achieving its

intended outcomes.

16

Given these and other studies, the organizations to which we spoke largely support

efforts to increase the State’s investment in programs that identify and address

the factors that may cause individuals to commit Proposition offenses. ese

factors include unmet community needs, such as access to housing, employment,

and programs to address mental health concerns. ACLU SoCal staff explained that

14

BSCC, “Proposition Cohort II: Statewide Evaluation,” February , <https://www.bscc.ca.gov/wp-content/

uploads///H--Proposition--Cohort--Final-Evaluation-Report-FINAL-.pdf>, accessed on April , .

15

The BSCC study indicated that the statewide recidivism rates may not be equitable recidivism timeframe

comparisongroups.

16

National Institute of Justice, “Program Profile: The Impact of California’s Proposition (The Reduced Penalties for Some

Crimes Initiative) on Recidivism,” November , <https://crimesolutions.ojp.gov/ratedprograms/->, accessed on

April , .

20 CALIFORNIA STATE AUDITOR

July 2024

|

Report 2023-107

they believe opportunities to address these community needs have been historically

underfunded in Riverside and SanBernardino counties and constitute some of the

underlying causes of why individuals may commit Proposition offenses.

In addition, the organizations expressed concerns that enhancing sentencing for

Proposition offenses would have negative consequences. For example, they

asserted that this step could remove funding for programs that have been effective

at addressing unmet community needs, as we describe above. Legal Services

forPrisoners with Children also emphasized that efforts to enhance sentencing for

Proposition offenses could actually lead to an increase in recidivism rates because

the collateral consequences associated with individuals receiving felony convictions—

including substantial barriers to accessing housing, employment, and education—

could negatively reinforce the underlying causes of why people commit crimes.

California Has Several Options for Addressing the Increases in Multiple Reoffenses

andTheft

As we previously explain, our analysis identified an increase among those who

reoffended with four or more convictions after the implementation of Proposition

at the three law enforcement agencies we reviewed. We also found an increase in

the frequency of theft convictions, particularly for individuals with four or more

convictions. To address the issues that we observed, the Legislature may want to

consider changes to the laws impacted by Proposition.

During the – legislative session, state legislators introduced multiple pieces of

legislation related to Proposition offenses. One option these bills have proposed

is increasing penalties for individuals convicted of multiple Proposition offenses.

We provide an example of some code sections that could be considered for such a

legislative change in Table . A second option the bills identify is expanding theft

diversion programs that allow individuals to enter treatment programs in lieu of

receiving jail sentences.

Proposition can be amended by a two-thirds vote of the members of each house

of the Legislature and signature by the Governor but only if the amendments are

consistent with, and further the intent of, the proposition. Alternatively, the Legislature

could also enact a proposal to amend Proposition; however, the proposed

amendment would not become effective until submitted to and approved by the

voters. is alternative process is required if the amendment is not consistent with

or does not further the intent of the proposition. Further, the people may introduce

ballot initiatives that amend or repeal Proposition. For example, ballot initiative

-A is qualified for the statewide November general election. If the voters

adopt it, this initiative would, among other things, make a third conviction for petty

theft and shoplifting a potential felony.

Our audit was limited to the three law enforcement agencies in two counties, and

the results of our analysis are not intended to be projected statewide. Although our

analysis showed an increase in the frequency of theft convictions among those who

reoffended with four or more convictions after the implementation of Proposition,

21CALIFORNIA STATE AUDITOR

Report 2023-107

|

July 2024

our analysis shows a correlation, but does not provide an explanation for the cause

of this increase. Nevertheless, we also considered interviews with law enforcement

agencies and other stakeholder groups, along with the external studies we discussed

previously, to ultimately inform the policy options listed below for the Legislature

toconsider.

Table 5

Examples of Laws That Could Be Amended to Allow Felony Charges if an Individual Has Multiple

Theft Convictions

CRIMINAL ACT CRIME TYPE

PC 459.5 — Shoplifting under $950

Theft

PC 490.2 — Theft under $950

PC 488 — Theft of money, labor, or property under $950

PC 496 — Receiving or buying stolen property under $950

Source: State law.

Note: This table provides offenses in the penal code that could be amended. It is not an exhaustive list of all offenses

affected by Proposition 47.

Recommendations

If the Legislature decides that it wants to take action to reduce the likelihood that

individuals with multiple convictions will continue to engage in theft, the Legislature

could consider the adoption of either or both of the following policy mechanisms:

• Appropriating funds for programs and services to address what it determines to

be the root causes of recidivism. In particular, it may want to identify and provide

funding to the types of programs and services that recent studies have identified as

effective in reducing recidivism.

• Either by enacting legislation that is consistent with and furthers the intent

ofProposition, or by enacting a proposal for approval by the voters that would

amend Proposition, to allow more severe punishment for those convicted

multiple times of theft, likely by identifying such offenses as potential felonies

instead of automatically classifying them as misdemeanors.

22 CALIFORNIA STATE AUDITOR

July 2024

|

Report 2023-107

Other Areas Reviewed

The Law Enforcement Agencies We Reviewed Did Not Make Significant Changes to

Their Policies as a Result of the COVID-19 Pandemic

e Audit Committee requested that we identify public safety policy changes in

SanBernardino and Riverside counties that resulted from the COVID- pandemic

and that we determine whether those policy changes affected the level of criminal

activity. We found that the three law enforcement agencies generally did not make any

policy or procedural changes to their normal operations as a result of the pandemic,

other than requiring notices for COVID- exposures. According to the agencies,

the pandemic did not result in any formally documented changes to department

policies and enforcement procedures except for some logistical changes to reduce

potential exposure to the virus. us, we did not identify substantive policy changes

at the three agencies that affected criminal activity in Riverside and SanBernardino

counties. Nevertheless, as we discuss in the Introduction, statewide bail rules

implemented during the pandemic may have affected incarceration levels.

Organized Retail Theft From 2019 to 2022

Over the past six years, the Legislature has

passed several pieces of legislation to combat

organized retail theft, an offense that became

effective in , several years after the

implementation of Proposition in . We

summarize some of the key components of

this legislation in the text box. Data from the

selected law enforcement agencies show that

of the nearly , arrests they made from

to , included arrest charges with

penal code provisions for organized retail theft.

According to officers at SanBernardino Police

and Riverside Sheriff, one explanation for the

seemingly small number of arrests for organized

retail theft is that officers may arrest individuals

who have allegedly committed organized retail

theft offenses under penal code sections that

are not specifically labeled as “organized retail

theft.” Riverside DA offered that a reason there

are relatively few arrests for organized retail theft

could be related to underreporting of theft-related

crimes. Riverside Sheriff also explained that the

California Highway Patrol received state funding

to address organized retail theft. erefore, the

arrest figures from the three law enforcement

agencies may not represent the total number of

organized retail theft arrests made in Riverside

and SanBernardino counties. However, this

Key Components of Recent Legislation to

Address Organized Retail Theft

• Defined organized retail theft to include the commission

of acts in concert with one or more persons to steal,

receive, purchase, or knowingly possess merchandise

taken from a merchant’s premises or online marketplace.

• Enables the prosecution of individuals who commit acts

of organized retail theft. Prosecutors can consider the

aggregated value of stolen merchandise over a 12‑month

period when charging an individual with organized

retailtheft.

• Extended the jurisdiction, and altered the subsequent

prosecution, of a criminal action for theft to include the

county where an offense involving the theft or receipt of

the stolen merchandise occurred, the county in which

the merchandise was recovered, or the county where any

act was done by the defendant in instigating, procuring,

promoting, or aiding in the commission of a theft offense.

• Enabled officers to hold a person following a misdemeanor

arrest if the officers have probable cause to believe the

person is guilty of committing organized retail theft.

• Mandated the California Highway Patrol to convene

a regional property crimes task force to assist local

law enforcement in counties with elevated levels of

propertycrime.

Source: State law.

23CALIFORNIA STATE AUDITOR

Report 2023-107

|

July 2024

was an audit specifically of Proposition’s effects in the two counties and the

penal code provisions for organized retail theft we analyzed were enacted years

after the implementation of Proposition. Ultimately, as we note on page , our

analysis found the frequency of theft convictions and—more specifically—of theft

convictions among those who reoffended with four or more convictions increased

after the implementation of Proposition, and we provide recommendations to the

Legislature to address thisissue.

We conducted this performance audit in accordance with generally accepted

government auditing standards and under the authority vested in the California

State Auditor by Government Code section et seq. ose standards require that

we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide

a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions, based on the audit objectives.

Webelieve that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings

and conclusions, based on our audit objectives.

Respectfully submitted,

GRANT PARKS

California State Auditor

July ,

Staff:

Nicholas Kolitsos, CPA, Audit Principal

Aaron Fellner, Senior Auditor

Eduardo Moncada

Kaleb Knoblauch

Myra Farooqi

Ashley Yan

Data Analytics: R. Wade Fry, MPA

Shauna M. Pellman, MPPA, CIA

Sarah Rachael Black, MBA, CISA

Legal Counsel: Joe Porche

24 CALIFORNIA STATE AUDITOR

July 2024

|

Report 2023-107

Appendix A

VOLUME OF SERVICE CALLS FOR ALLEGED PROPOSITION 47 OFFENSES

BY CRIME CATEGORY

Table A shows the volume of alleged Proposition -related service calls made

to each of the three law enforcement agencies we selected for review. e table

separates the calls by the categories of the alleged offenses: burglary, drug

possession, forgery, and theft.

Table A

Volume of Alleged Proposition 47-Related Service Calls by Crime Category

2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

Riverside Police

Burglary 5,884 6,066 5,681 5,828 5,613 4,475 5,031 5,723 5,077 4,881 4,585 4,881 5,118 4,937

Drug possession 549 419 433 458 519 467 207 225 178 207 287 143 111 88

Forgery 306 296 277 359 228 281 257 271 307 306 335 206 125 171

Theft 8,454 8,346 8,069 9,237 9,217 9,237 9,838 10,824 9,886 10,093 9,609 9,182 9,028 10,341

Riverside Sheri

Burglary 11,020 10,216 11,107 12,952 11, 294 10,285 9,166 8,334 8,523 7,567 7,302 6,011 5,940 6,037

Drug possession 9,289 9,000 8,898 10,088 11,439 11,6 47 9,888 10,132 9,353 8,992 9,988 9,385 8,770 8,876

Forgery 7,811 7,350 6,897 8,544 9,228 10,275 10,405 10,608 9,881 8,869 8,879 7, 861 8,941 10,346

Theft 32,948 31,059 33,809 39,194 39,339 38,690 45,126 46,775 45,675 44,119 42,878 38,240 38,412 42,619

San Bernardino Police

*

Burglary 1,562 1,493 1,236 1,712 1,298 1,447 1,662 1,169 537 324 335

Drug possession 7 5 2 2 2 1 4 0 0 0 0

Forgery 638 429 480 566 438 408 425 421 137 147 102

Theft 6,215 6,665 6,388 7,004 5,434 4,878 5,044 4,772 3,520 4,084 3,635

Source: Analysis of Riverside Police, Riverside Sheriff, and San Bernardino Police CAD systems.

* San Bernardino Police’s CAD data are only complete dating back to 2012.

25CALIFORNIA STATE AUDITOR

Report 2023-107

|

July 2024

Blank page inserted for reproduction purposes only.

26 CALIFORNIA STATE AUDITOR

July 2024

|

Report 2023-107

Appendix B

NUMBER OF ARREST CHARGES AT EACH LAW ENFORCEMENT AGENCY FOR

ALLEGED PROPOSITION 47 OFFENSES BY CRIME CATEGORY

Table B shows the number of arrest charges for alleged Proposition offenses at the three

law enforcement agencies we selected for review. e table separates the arrest charges by

category. An individual might be arrested on multiple charges. e decreases in arrests,

which we discuss in the Audit Results, correspond with the decreases in arrest charges,

but because multiple arrest charges may be combined in a single arrest, the table will not

reconcile to Figure .

Table B

Number of Arrest Charges at Each Law Enforcement Agency for Alleged Proposition 47 Offenses by Crime Category

2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

PERCENT

CHANGE

THROUGH

2014

2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

PERCENT

CHANGE

FROM 2014

THROUGH

2022

OVERALL

PERCENT

CHANGE

Riverside Police

Burglary 542 500 497 648 657 618

↑ 14%

200 213 194 129 169 167 136 163

↓ 74% ↓ 70%

Drug

possession

1,346 1,306 1,018 1,163 1,381 1,557

↑ 16%

945 1,152 928 1,070 1,169 999 867 537

↓ 66% ↓ 60%

Forgery 144 104 115 108 98 110

↓ 24%

74 51 74 70 36 23 28 8

↓ 93% ↓ 94%

Theft 2,097 1,866 1,700 1,784 1,766 1,936

↓ 8%

1,894 1,843 1,543 1,240 1,182 813 624 600

↓ 69% ↓ 71%

Riverside Sheri

Burglary 2,536 2,211 1,992 2,124 1,862 1,632

↓ 36%

663 600 614 560 488 498 419 610

↓ 63% ↓ 76%

Drug

possession

4,832 4,390 4,041 4,046 4,923 4,719

↓ 2%

2,778 2,976 2,626 2,581 3,142 3,080 3,384 3,757

↓ 20% ↓ 22%

Forgery 393 308 287 229 274 210

↓ 47%

196 185 177 126 130 82 84 119

↓ 43% ↓ 70%

Theft 4,801 4,179 3,909 4,022 3,915 3,840

↓ 20%

4,262 3,671 3,013 2,790 2,597 1,994 1,910 2,986

↓ 22% ↓ 38%

San Bernardino Police

*

Burglary 297 409 340

↑ 14%

269 210 180 178 183 163 123 125

↓ 63% ↓ 58%

Drug

possession

462 498 604

↑ 31%

205 316 383 498 424 390 315 294

↓ 51% ↓ 36%

Forgery 56 39 43

↓ 23%

16 19 22 15 15 4 7 3

↓ 93% ↓ 95%

Theft 1,116 1,050 1,047

↓ 6%

721 634 610 614 530 419 406 367

↓ 65% ↓ 67%

Source: Analysis of Riverside Police, Riverside Sheriff, and San Bernardino Police RMS data.

* San Bernardino Police’s RMS data are only complete dating back to 2012.

27CALIFORNIA STATE AUDITOR

Report 2023-107

|

July 2024

Blank page inserted for reproduction purposes only.

28 CALIFORNIA STATE AUDITOR

July 2024

|

Report 2023-107

Appendix C

RECIDIVISM METHODOLOGY

e Audit Committee directed us to assess the rates of recidivism in SanBernardino

and Riverside counties for individuals following their convictions for Proposition

offenses before and after the proposition took effect. We consulted with a statistician

to use data from the DOJ to select statistically valid sample for two cohorts—one in

and one in —across the three law enforcement agencies. is allowed us to

project to the population of individuals convicted of a Proposition offense for the

jurisdictions of the three law enforcement agencies in the two counties.

Our samples consisted of total offenders divided into the two cohorts, as FigureC

describes. To measure reoffense rates before the implementation of Proposition

in November , we randomly selected from the three law enforcement agencies a

proportional sample of individuals who were convicted of a Proposition offense

in .

17

To measure reoffense rates after the implementation of Proposition and

to allow the changes to law some time to take effect, we also randomly selected from

the three law enforcement agencies a proportional sample of individuals who were

convicted of a Proposition offense in . e availability of data affected the size

of our samples. In some cases, the smaller sample sizes had minimal impact on the

precision of the results.

We developed our analysis based on the BSCC’s definition of recidivism: a conviction

of a new felony or misdemeanor committed within three years of release from

custody or within three years of placement on supervision for a previous criminal

conviction. According to this definition, “a new felony or misdemeanor” excludes

cases dropped or dismissed; noncriminal traffic offenses, regardless of guilt;

new jail admissions; and violations of supervision (parole, probation, mandatory

supervision, or other terms of release). We reviewed publicly available case histories

and court records provided by Riverside and SanBernardino county superior

courts to determine whether individuals in the samples were convicted of offenses

within three years of their first conviction. Additionally, we reviewed DOJ records