Diego Chaves-González

Natalia Delgado

A Winding Path to Integration

Venezuelan Migrants’ Regularization

and Labor Market Prospects

A Winding Path to Integration

Venezuelan Migrants’ Regularization

and Labor Market Prospects

Diego Chaves-González

Natalia Delgado

October 2023

LATIN AMERICA AND CARIBBEAN INITIATIVE

Contents

Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................................ 1

1 Introduction ...............................................................................................................................................3

2 Regular and Irregular Migrants and Their Economic Integration ....................6

A. Formal and Informal Economies .......................................................................................................................7

B. Dierent Routes to Irregular Status .................................................................................................................9

C. Regularization Mechanisms .............................................................................................................................. 10

3 Venezuelans’ Regularization and Labor Market Integration

in Colombia ..............................................................................................................................................

16

4 Venezuelans’ Regularization and Labor Market Integration

in Other Quito Process Countries ...........................................................................................

25

5 Final Remarks and Recommendations .............................................................................. 34

About the Authors ........................................................................................................................................ 38

Acknowledgments ....................................................................................................................................... 39

MPI and IOM | PB MPI and IOM | 1

A WINDING PATH TO INTEGRATION A WINDING PATH TO INTEGRATION

Executive Summary

The scale of displacement from the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela since 2015, with more than 6 million

Venezuelan refugees and migrants moving to other countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, has

challenged governments across the region to rethink how they manage movement across their borders

and the integration of immigrants within them. With many Venezuelans expressing the intention to stay

permanently in their new countries of residence, those countries have used various policy tools to grant

newcomers access to basic services and to support their integration into local communities.

Most notable among these are the registration and regularization mechanisms used to register Venezuelans

who have entered a country and provide them with regular status. Governments in Latin America and the

Caribbean have opted to regularize large segments of this population for a combination of economic, social,

and security-related reasons. When well-planned and properly executed, these tools have opened pathways

that allow Venezuelans to access basic services and formal labor market opportunities and promoted their

long-term integration and socioeconomic inclusion. Yet despite these eorts, many Venezuelans still lack a

regular immigration status, shutting them out of services and integration opportunities and pushing them

into the informal market and often vulnerable living conditions.

As recognition has grown that Venezuelan migration will not be a short-term phenomenon, governments

in the region are increasingly acknowledging that eectively supporting newcomers and the communities

in which they settle requires a long-term, whole-of-government, and multistakeholder approach that links

migrant integration to broader development strategies.

Bringing this longer-term perspective into regularization

policies and tackling barriers to integration will be important

parts of this shift. To do so, countries will need to critically

assess their institutions and policies for governing migration

and integration, and ensure that stakeholders ranging from

the private sector and civil society to dierent levels of

government can coalesce around shared goals.

An important rst step is understanding how registration and regularization mechanisms have aected

Venezuelans’ economic integration to date. Measuring their direct implications is challenging, given the

wide range of factors that inuence integration and uneven data across the region. This study compiles the

evidence available on the links between providing regular status and the economic benets for migrants

and for receiving countries. Colombia—which has received the most Venezuelans and operated the region’s

largest and most-studied regularization mechanism—oers an important case study. The Colombian

experience is then compared to ndings from the other Latin American and Caribbean countries that make

up the Quito Process, which has named Venezuelans’ socioeconomic integration as a top priority. The report

uses that evidence to identify observations that may be generalizable across most countries in the region

and those that are unique to a specic country or subregion.

An important rst step is

understanding how registration

and regularization mechanisms

have aected Venezuelans’

economic integration to date.

MPI and IOM | 2 MPI and IOM | 3

A WINDING PATH TO INTEGRATION A WINDING PATH TO INTEGRATION

This study’s comprehensive mapping suggests the following factors have been critical to how regularization

mechanisms are shaping migrants’ labor market opportunities:

► The scale and ongoing nature of Venezuelan migration. While many countries have introduced

regularization measures, Venezuelan migration continues across the region and has often outpaced

Quito Process Member States’ capacity to grant regular status. Thus, even as notable numbers of

Venezuelans have been able to regularize their status, many remain irregular.

► Temporary versus permanent regular status. The most generous regularization mechanisms in the

region have granted Venezuelans a pathway to permanent residence, in addition to permission to

work and access public services. Other temporary regularization mechanisms, by contrast, generally

do not lead to longer-term residency permits and thus entail a greater degree of uncertainty for both

Venezuelan workers and employers who may be wary of hiring someone who may not remain in the

country or legally employable for long. Still, many Venezuelan irregular migrants have established

strong labor market and social ties in their host countries and are working in steady, if informal, jobs.

► Venezuelans’ relatively high levels of human capital. Venezuelans, especially those who arrived in

earlier periods and have stayed in their host countries for longer, tend to have high levels of education.

Their skills represent a signicant human capital asset that could contribute to receiving-country

economic and development goals, if Venezuelans can access jobs in their elds and career-building

opportunities. To date, migrants’ salaries are generally lower than those of the native population. After

regularization, however, there is some evidence of an increased dierentiation among Venezuelan

workers, with a stronger correlation between human capital characteristics and income level.

► The prevalence of labor informality. Venezuelan migrants are more likely to be employed informally

compared to most countries’ nationals, even as many of these countries have high overall rates of

labor informality. In this context, regularization might help migrants nd work with better labor

conditions, but it does not necessarily mean they will enter the formal sector.

► The existence and enforcement of labor regulations. In some cases, complex labor laws that make

it more costly to formally hire workers may disincentivize employers and migrants (even if they have

regular status) from moving toward a formal employment arrangement. The manner in which labor

regulations and rules against hiring irregular migrants are (or are not) enforced also plays a role in

whether regularization leads to formal work, and to migrants fullling related obligations such as

paying taxes and contributing to social security systems.

With these considerations in mind, the study presents recommendations that could help Latin American

and Caribbean countries follow through on their commitments to reduce Venezuelans’ socioeconomic

vulnerability and maximize this population’s contributions to the economies of their host countries.

► Strengthening registry mechanisms and better leveraging the data they collect. There are

numerous ways in which migrants can fall into irregular status, and policymakers should consider the

administrative distinctions—the “demography” of irregular migration—when designing regularization

mechanisms. It is equally fundamental to ensure that registry mechanisms produce timely and

relevant data for operational, analytical, and policy purposes. Improving these data systems,

MPI and IOM | 2 MPI and IOM | 3

A WINDING PATH TO INTEGRATION A WINDING PATH TO INTEGRATION

including through partnerships with external entities to support data analysis, is critical to enhancing

government regularization and integration policies in the long term.

► Reinforcing the links between regularization and employment. Most current regularization

programs oer status that is explicitly temporary, lasting for a year or two. However, creating permits

with a longer duration (and that allow migrants to work, where that is not already the case) and a

pathway to permanent residence could form the foundation for a longer-term strategy focused on

how regularization can support both migrant integration and host-country development goals.

► Increasing dialogue between government and the private sector. Private-sector actors play an

important role in migrants’ labor market integration, but their involvement in integration policy

conversations is often limited. Governments could seek to more fully engage them and tap their

expertise for initiatives that aim to better match migrants’ skills and employer needs, increase migrant

participation in the formal sector, and raise awareness of rules around hiring migrants and of migrant

workers’ rights.

► Supporting Venezuelan migrants’ economic mobility. While Venezuelans have relatively high

levels of human capital, many have been unable to apply their skills in the countries where they have

settled. Opportunities to develop or strengthen technical skills and streamlined systems to recognize

credentials earned abroad could help more newcomers nd work in their elds and potentially help

close the native-migrant earnings gap.

► Building on opportunities for regional exchanges of ideas and support. The Quito Process

has helped countries coordinate their responses to Venezuelan migration, and it could be further

leveraged to exchange best practices and provide support as countries rene their regularization

measures.

1 Regional Inter-Agency Coordination Platform for Refugees and Migrants from Venezuelan (R4V), “Venezuelan Refugees and

Migrants in the Region” (fact sheet, August 2023).

As Latin American and Caribbean countries move away from short-term emergency responses and look to

long-term integration, there are real opportunities to link regularization mechanisms with eorts to meet

labor demands. These policy tools can help countries design regularization programs that reect evolving

migration trends, connect these with tangible economic benets for migrants and the communities in

which they live, and support broader strategies to address complex development challenges in the region.

1 Introduction

As of August 2023, 7.7 million Venezuelans had left their home country, with 6.5 million moving to other

countries within Latin America and the Caribbean. More than one-third of all displaced Venezuelans were

thought to be in Colombia (2.9 million), followed by 1.5 million in Peru and roughly half a million each

in Brazil, Ecuador, and Chile. The rest of the region hosts an estimated 700,000 Venezuelan migrants and

refugees.

1

The scale of this displacement crisis, which began around 2015, has challenged Latin American and

Caribbean countries to nd better ways to manage increased movement across their borders. In this,

MPI and IOM | 4 MPI and IOM | 5

A WINDING PATH TO INTEGRATION A WINDING PATH TO INTEGRATION

registration and regularization mechanisms

2

have become key policy tools. Most countries in the region

have sought to regularize Venezuelans’ status in one (or more) of the following ways: using existing

regional mobility and residence agreements; adapting visa systems to allow displaced Venezuelans to apply

more easily for existing residency visas; or creating ad hoc regularization programs, either specically for

Venezuelans or for a broader population of migrants with irregular status. Finally, a few countries (such as

Brazil, Costa Rica, and Mexico) have used their asylum systems to grant Venezuelans temporary status, and

some (such as Costa Rica

3

) have introduced forms of complementary protection.

Importantly, the Venezuelan migrant population—both across and within individual receiving countries—is

far from monolithic. Displaced Venezuelans vary in terms of their economic background, level of education,

professional training and skills, age, social networks, and date of entry. Each of these characteristics aects

the extent of Venezuelans’ labor market integration. Registration is a rst, necessary step that can enable

receiving-country authorities to understand the characteristics of newcomers within their territory and

provide a sound statistical basis for regularization and integration policy planning.

4

Some countries,

such as Colombia

5

and Ecuador,

6

have used their

registration exercise to collect such vital information.

However, interviews with members of civil society and

representatives of UN agencies suggest that although

registration initiatives have been an essential milestone

for regularization processes, countries could still make

better use of the information gathered as they design

integration policies, tailoring them to the dierent

needs of registered migrants.

7

Regularization mechanisms usually come with the promise of economic and labor market benets for both

the receiving society and the newcomers involved. In general, regularized migrants are incorporated into

the formal economy and, thus, increase contributions to tax and social security systems. Regularization

can also potentially increase immigrant workers’ productivity by allowing them to have their skills and

qualications recognized, to seek out positions that let them apply these skills and for which they will be

paid fairly, and to access training and education—all things that can contribute to a country’s medium-

and long-term development goals. However, there is no guarantee that regularization on its own will

produce these benets. If the skills of regularized Venezuelans are not identied in the registration phase,

do not match formal labor market needs, or if Venezuelan workers and/or receiving-country employers

have insucient incentives to engage with one another in the formal sector, large numbers of migrant

2 Registration mechanisms aim to collect and update information about migrants to inform policy design and to identify those

migrants who may wish to access temporary protection measures. Regularization mechanisms, meanwhile, allow migrants to

apply for a regular immigration status and, if they fulll requirements set by the country’s government, to receive permission

to stay for a certain period of time and engage in specied activities, such as accessing education, receiving health care, and

pursuing formal employment.

3 Government of Costa Rica, “Categoría Especial Temporal de Protección Complementaria,” updated July 13, 2022.

4 Ginetta Gueli, Regional Knowledge Management Strategy and Action Plan 2022–2027 of IOM in South America (Buenos Aires:

International Organization for Migration, 2022).

5 Migración Colombia, “RUMV,” accessed November 7, 2022.

6 Government of Ecuador, Ministry of Government, “Registro Migratorio de Ciudadanos Venezolanos en Ecuador,” accessed

November 7, 2022.

7 Authors’ interviews with representatives of civil-society organizations working across the region and UN agencies, August 2022.

Regularization mechanisms usually

come with the promise of economic

and labor market benets for

both the receiving society and the

newcomers involved.

MPI and IOM | 4 MPI and IOM | 5

A WINDING PATH TO INTEGRATION A WINDING PATH TO INTEGRATION

workers may remain unemployed or in the informal sector, slowing their inclusion. This is a particularly

relevant concern in the many Latin American and Caribbean countries with society-wide high rates of labor

informality and unemployment.

Little research has been done to date on how providing regular status to Venezuelan migrants aects their

economic prospects in Latin American and Caribbean countries. This report looks specically at Venezuelans

in countries that are Member States of the Quito Process (see Box 1) to gather evidence on the potential

impacts of regularization mechanisms on migrants’ access to socioeconomic opportunities. While some

other studies have examined this issue in certain countries, this report brings together information and data

from across all Quito Process countries where sucient evidence exists on the eects of migrants’ regular

status on their economic outcomes.

The report uses a mix of sources to explore this topic, including a review of existing data and research

as well as unique insights gathered from policy and regional experts, migrants, integration-focused

organizations, and private-sector stakeholders through 18 interviews and 3 focus groups conducted

between July and December 2022. It analyses whether registration and regularization mechanisms have

successfully increased Venezuelans’ participation in the formal sector, reduced their rates of informality, and

allowed them to become more integrated and productive in their receiving countries. The report also draws

out observations that may be generalizable across Quito Process Member States and identies those that

are unique to a specic country or context.

BOX 1

What Is the Quito Process, and How Does It Support Migrants’ Socioeconomic Integration?

The Quito Process is an intergovernmental initiative established in Latin America and the Caribbean in

2018 to coordinate responses to the Venezuelan migration crisis through nonbinding commitments and

technical assistance. The Quito Declaration on Human Mobility of Venezuelan Citizens in the Region,

signed September 2018, urges governments to reinforce reception policies for Venezuelans; coordinate

eorts through international organizations; ght discrimination, intolerance, and xenophobia; strengthen

regulation mechanisms to promote and respect the rights of migrants; amongst other things. As of mid-

2023, the Member States of the Quito Process are: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, the

Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Guyana, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, and Uruguay.

The socioeconomic integration of Venezuelan migrants is one of the Member States’ priorities, as evidenced

by their joint declarations following the fourth technical meeting in Buenos Aires in 2019. This focus can

also be seen in the 2021 Regional Socioeconomic Integration Strategy, which describes registration and

regularization as a central axis of the socioeconomic integration of migrants.

Sources: Quito Process, “What We Do?,” accessed October 11, 2022; Quito Process, “Declaración de Quito sobre Movilidad Humana

de ciudadanos venezolanos en la Región,” September 4, 2018; Quito Process, “Joint Statement by the Fourth International Technical

Meeting on Human Mobility of Venezuelan Nationals” (statement, Buenos Aires, July 22, 2019); Quito Process, Regional Inter-Agency

Coordination Platform for Refugees and Migrants from Venezuela (R4V), International Labor Organization (ILO), and United Nations

Development Program (UNDP), Migration from Venezuela: Opportunities for Latin America and the Caribbean. Regional Socio-Economic

Integration Strategy (Geneva: ILO and UNDP, 2021); Quito Process, “Socio-Economic Insertion,” accessed June 26, 2023.

MPI and IOM | 6 MPI and IOM | 7

A WINDING PATH TO INTEGRATION A WINDING PATH TO INTEGRATION

This study should be seen as a preliminary step toward understanding the relationship between registering

migrants, providing them a regular status, and their economic outcomes in societies that generally

have high levels of informal work, which does not generally require legal documentation. Since there

are signicant information gaps in this research area, it is dicult to draw rm conclusions about the

relationship; this report attempts to provide an overview of what the available evidence suggests. The nal

section of this report sketches a roadmap of recommendations for Quito Process countries as they continue

to rene how they register Venezuelan migrants, design and implement mechanisms to grant them regular

status, and foster their integration.

To inform these recommendations, Section 3 of this report examines the case of Colombia’s Special

Stay Permit (PEP) and Temporary Statute of Protection for Venezuelan Migrants (TSPV)—the largest and

most studied regularization eort in the region, and one that can be seen as a strategic decision by the

Colombian government that supporting Venezuelans’ integration would serve the country’s medium- and

long-term development goals.

8

The TSPV was administrated at a relatively low cost and led to the approval

of nearly 1,181,000 Temporary Protection Permits (PPT) within the rst year.

9

Section 4 of this report then

explores evidence from regularization mechanisms launched by other Quito Process Member States,

comparing and contrasting them to the Colombian experience. Together, this analysis oers a window into

what has and has not worked in the region to date, and where opportunities for future policy improvements

lie.

2 Regular and Irregular Migrants and eir Economic

Integration

Assessing how registration and regularization mechanisms aect migrants’ labor market integration, and

what the costs and benets are, requires consideration of the labor dynamics in each country. Overall,

Venezuelan migrants bring substantial economic benets to receiving countries in their capacity as workers,

especially when regularized. For example, their labor can bring down the cost of goods and services for

consumers and make companies (and sometimes entire sectors) more competitive.

10

Evidence in the region

also suggests Venezuelan migration has expanded the general economic activity from which taxes and

public contributions are drawn.

11

8 Authors’ interview with a representative of the Colombian Border Manager’s Oce, August 2022.

9 Jordan Flores, “Casi el 16 % de los migrantes venezolanos en Colombia aún no recoge su Permiso de Protección Temporal,” El

Diario, May 25, 2022.

10 Fedesarrollo and ACRIP, Informe Mensual del Mercado Laboral (Bogotá: Fedesarrollo and ACRIP, 2018).

11 World Bank, Migración desde Venezuela a Colombia: Impactos y Estrategia de Respuesta en el Corto y Mediano Plazo (Bogotá: World

Bank, 2018); World Bank, An Opportunity for All: Venezuelan Migrants and Refugees and Peru’s Development (Lima: World Bank, 2019);

World Bank, Retos y oportunidades de la migración venezolana en Ecuador (Quito: World Bank, 2020).

MPI and IOM | 6 MPI and IOM | 7

A WINDING PATH TO INTEGRATION A WINDING PATH TO INTEGRATION

However, the economic benets linked to regularization tend to be stronger in receiving countries where

migration and labor regulations not only exist on paper but are also enforced in practice. In most Quito

Process Member States, there is a high level of regulation surrounding formally hiring employees, but

some countries do not rigorously enforce these employment laws. Where regulations are strict but poorly

enforced, employers have few incentives to invest the extra time and money in formally hiring their

employees, and native-born and immigrant workers alike

may nd it easier to secure work informally. Although

informally hired workers tend to be paid less, the

Venezuelan migrants and representatives of integration-

focused organizations who participated in this study’s

focus groups

12

described how informal work is often

seen as a win-win situation for employers and migrant

employees. One participant explained that, since they

are unlikely to be detected by authorities, “there are

economic gains on both sides because paying for social

security [as is required in formal employment] means less money in the pocket of everyone.” In such cases,

the benets of regularization for migrants and of migrant workers for receiving-country economies are less

straightforward and often harder to quantify.

Consequently, across Quito Process Member States, factors such as the size of a country’s informal economy,

how migrants fall into irregularity, and how the country is implementing regularization mechanisms are

all relevant when analyzing the potential benets of regularization. Balancing these three considerations

is crucial for the sustainability of regularization processes as well as their success in promoting formal

employment among migrants.

A. Formal and Informal Economies

Broadly, the “informal economy” refers to all economic activities that, in law or in practice, are not

(suciently) regulated.

13

The prevalence of informal employment varies across Latin American and

Caribbean countries. As such, providing migrants with a regular status may do more in some national

contexts than others in terms of helping them access formal employment and opportunities to earn a better

income.

Analysis of survey-based studies and national data suggest that the informal economy accounts for, on

average, an estimated 33.9 percent

14

of GDP in Quito Process Member States. However, the share is far

larger—between 42 and 52 percent of GDP—in Peru, Paraguay, and Panama (see Table 1).

12 Participant comments during Migration Policy Institute (MPI) online focus groups with Venezuelan migrants and integration-

focused organizations in Colombia, Peru, and Ecuador, August 18 and 22, 2022.

13 See International Labor Organization (ILO), “Informal Economy,” accessed February 6, 2023.

14 This regional gure was calculated using the national data in Table 1.

The economic benets linked to

regularization tend to be stronger

in receiving countries where

migration and labor regulations

not only exist on paper but are

also enforced in practice.

MPI and IOM | 8 MPI and IOM | 9

A WINDING PATH TO INTEGRATION A WINDING PATH TO INTEGRATION

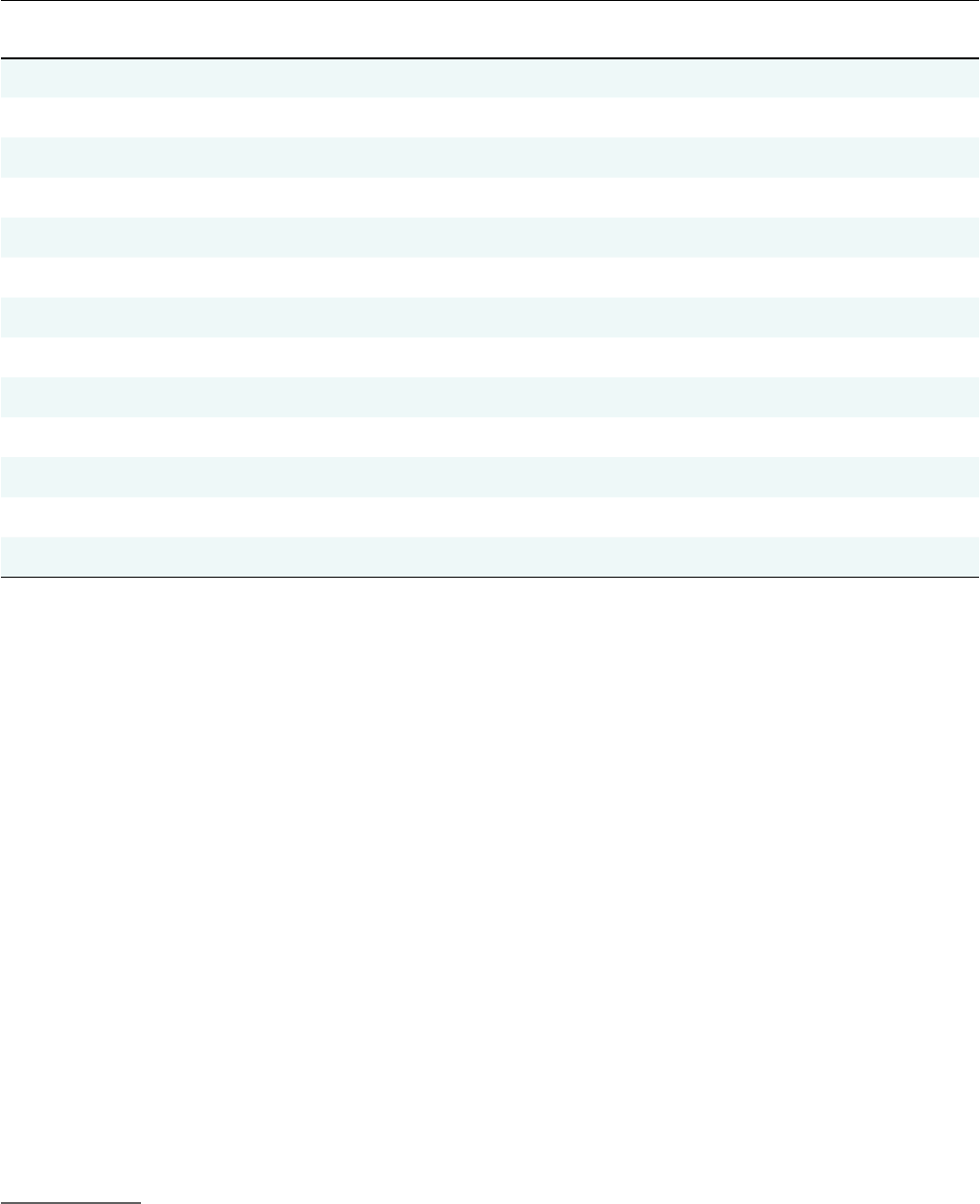

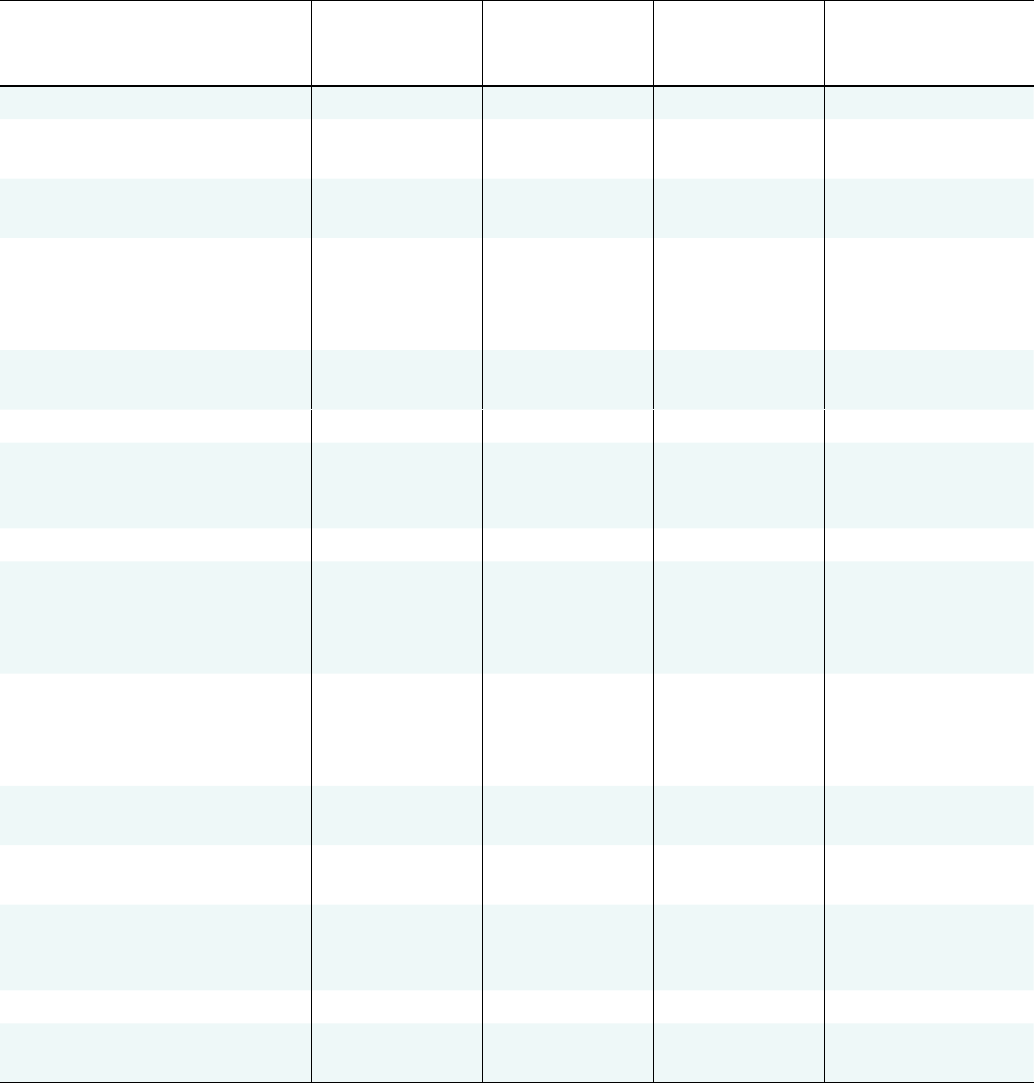

TABLE 1

GDP and the Formal and Informal Economies in Quito Process Member States, 2022

Country GDP (billions of

U.S. dollars)

Informal % of

Employment

Formal % of

Employment

Informal Economy

as a % of GDP

Argentina 630.7 37.4% 62.6% 27.3%

Brazil 1890.0 38.9% 61.1% 33.2%

Chile 310.9 34.5% 65.5% 19.3%

Colombia 342.9 58.2% 41.8% 33.3%

Costa Rica 68.5 43.9% 56.1% 26.6%

Dominican Republic 112.4 52.1% 47.9% 33.9%

Ecuador 115.5 53.4% 46.6% 37.2%

Guyana* 14.8 48.5–52.9% 51.5–47.1% 29.1%

Mexico 1420.0 54.9% 45.1% 29.2%

Panama 71.1 48.2% 51.8% 51.6%

Paraguay 41.9 63.5% 36.5% 46.5%

Peru 239.3 76.1% 23.9% 42.2%

Uruguay 71.2 20.0% 80.0% 31.7%

* Informal employment data are from 2022 and were obtained from ocial government sources. The only exception is Guyana, for

which this table shows a 2021 gure that was in the last bulletin published on the Guyanese government’s website.

Sources: World Economics, “Informal Economy Size,” accessed February 10, 2023; International Monetary Fund (IMF), “World Economic

Outlook (October 2022) - GDP, Current Prices” (dataset, October 2022); Argentine National Institute of Statistics and Census (INDEC),

Mercado de trabajo. Tasas e indicadores socioeconómicos (EPH): Tercer trimestre de 2022 (Buenos Aires: INDEC, 2022); Brazilian Institute of

Geography and Statistics (IBGE), Indicadores IBGE: Trimestre Móvel set. - nov. 2022 (Rio de Janeiro: IBGE, 2023); Chilean National Statistics

Institute (INE), “Boletín Estadístico: Informalidad Laboral” (bulletin, February 2, 2023); Colombian National Administrative Department

of Statistics (DANE), “Ocupación informal: Trimestre móvil septiembre - noviembre 2022” (technical bulletin, Bogotá, January 16, 2023);

Costa Rican National Institute of Statistics and Census (INEC), “Encuesta Continua de Empleo - Indicadores generales de la condición

de actividad según país de nacimiento - IV Trimestre 2022” (dataset, 2022); Guyanese Bureau of Statistics, Guyana Labour Force Survey

November 2021 (Georgetown: Bureau of Statistics, 2021); Central Bank of the Dominican Republic, “Boletín trimestral del mercado

laboral: julio-septiembre 2022” (bulletin, 2022); Ecuadorian National Institute of Statistics and Censuses (INEC), “Encuesta nacional de

empleo, desempleo y subempleo (ENEMDU): indicadores laborales diciembre 2022” (technical bulletin, January 24, 2023); Mexican

National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI), “Indicadores de ocupación y empleo: Diciembre 2022” (press release, January

26, 2023); Panamanian National Institute of Statistics and Census (INEC), “Situación de la población ocupada, ” updated April 2022;

Paraguayan National Statistics Institute (INE), “Boletín trimestral de empleo – 3er trimestre 2022” (bulletin, November 2022); Peruvian

National Institute of Statistics and Informatics (INEI), “Comportamiento de los indicadores de mercado laboral a nivel nacional: julio-

agosto-septiembre 2022” (technical brief, November 2022); Uruguayan National Statistics Institute (INE), “Encuesta Continua de

Hogares – No Registro y Subempleo” (dataset, 2022).

The relatively small size of the informal economy in Chile, for example, likely translates to greater economic

benets from regularization than is the case in many other Quito Process Member States. The country has

a comparatively low rate of informal employment, and its rigorous enforcement of rules against hiring

irregular migrants makes it particularly dicult for Venezuelans without regular status to nd formal

employment.

15

For years, Chile did not have a migrant regularization mechanism, and the mechanism

implemented in 2021 excluded migrants who did not arrive in the country through authorized entry

15 LuicyPedroza, Pau Palop-García, and Young Chang,Migration Policies inChile 2017-2019(Hamburg, Germany: GIGA, 2022).

MPI and IOM | 8 MPI and IOM | 9

A WINDING PATH TO INTEGRATION A WINDING PATH TO INTEGRATION

points. The combination of a relatively small informal economy and strong labor practices suggests that

regularization could present important economic benets for those who qualify, but also that those who do

not qualify are likely to face heightened economic precarity.

Migrants in countries such as Peru

16

and Ecuador

17

seem much more likely to nd work in the informal

sector, due to the larger size of those countries’ informal economies. Complex labor laws in Andean

countries that require high social security contributions raise the costs of formal employment in these

countries, incentivizing employers and workers (native-born and immigrant alike) to instead make informal

arrangements.

18

This is particularly true in the many countries in the region that have limited capacity to

enforce rules around labor formality.

19

Because of the large size of the informal economy in most Quito Process Member States, both irregular and

regular migrants often work informally (as do many native-born workers). Therefore, when Member States

consider implementing regularization mechanisms, it is important that policymakers understand how

immigrants interact with the economy and how gaining regular status and the right to work may or may not

change that. Regularization may still yield other benets (in terms of service access and social cohesion, for

example) but alone may not be enough to connect migrants with the formal economy.

B. Dierent Routes to Irregular Status

A signicant portion of the Venezuelan migrant population in Latin America and the Caribbean consists of

individuals with an irregular immigration status. However, dierent circumstances can lead individuals to

irregular status, and this can ultimately aect the extent to which migrants can access benets and whether

they are eligible for regularization programs.

For example, a Venezuelan migrant who

entered a country through an unauthorized

border crossing and one who entered the

same country with a visa or permit but

overstayed it may have dierent levels of

access to assistance and regularization

options.

While Southern Cone countries can expect the overwhelming majority of their irregular Venezuelan

migrants to have overstayed permits, Andean countries that share long, porous borders experience frequent

16 In the case of Peru, the absence of labor contracts is widespread among employed refugees and migrants. Only 19.2 percent of

employed workers have some type of contract. However, this represents an increase of 7.7 percent compared to the rate recorded

by the Survey of the Venezuelan Population Living in the Country (ENPOVE) survey in 2018 (11.5 percent). See Peruvian National

Institute of Statistics and Informatics (INEI), Condiciones de Vida de la Población Venezolana que reside en el Perú (Lima: INEI Peru,

2022); R4V, GTRM Perú -Análisis conjunto de necesidades para el RMRP 2022 (Lima: R4V, 2022).

17 In June 2022, the informality rate was 50.6 percent, according to the National Survey of Employment, Unemployment, and

Underemployment (Enemdu) for the second trimester of 2022. See Ecuadorian National Institute of Statistics and Census

(INEC), Encuesta Nacional de Empleo, Desempleo y Subempleo - ENEMDU (Quito: INEC Ecuador, 2022); R4V, Evaluación conjunta de

necesidades: Informe de resultados de Ecuador-mayo 2022 (Quito: R4V, 2022).

18 Center for Social and Labor Studies (CESLA) and National Businessmen’s Association of Colombia (ANDI), Nuevas políticas de

empleo para la región andina (Bogotá: CESLA and ANDI, 2021).

19 ILO, Panorama Laboral 2021: América Latina y El Caribe (Lima: ILO, 2021).

Dierent circumstances can lead individuals

to irregular status, and this can ultimately

aect the extent to which migrants can

access benets and whether they are eligible

for regularization programs.

MPI and IOM | 10 MPI and IOM | 11

A WINDING PATH TO INTEGRATION A WINDING PATH TO INTEGRATION

irregular border crossings. In Central America and Mexico, irregular border crossings are also common; many

Venezuelans cannot access a visa, and the number of Venezuelan nationals traveling northward through

Central America via land routes has increased in recent years. In 2022, for example, more than 150,000

Venezuelan nationals entered Panama by irregularly crossing the Darién Gap, with the intention of reaching

the United States.

20

These trends in how Venezuelans become irregular migrants should guide policymakers as they design and

implement regularization measures, and help them set realistic expectations regarding the impact of these

mechanisms.

C. Regularization Mechanisms

Countries in Latin America and the Caribbean have almost all made responding to Venezuelan migration

a high priority on their policy agendas. However, the ways in which they have done so have varied. Some

countries (such as Uruguay and Argentina) have relied on established legal frameworks to facilitate

Venezuelans’ access to regular status, while others (such as Colombia, Chile, Ecuador, Peru, and Brazil) have

created specic mechanisms to regularize Venezuelan migrants.

21

And some countries have used a mix of

policy tools (including existing temporary and permanent visas, mobility and residence agreements, special

regularization campaigns, and in some cases, asylum procedures) to grant Venezuelans status.

22

Estimates of the share of Venezuelans who have regular status vary greatly across data sources, both at the

regional and country level. One such estimate, published by the Migration Policy Institute in early 2023,

found that at least half and as many as three-fourths of displaced Venezuelans across the top 15 receiving

countries in Latin America and the Caribbean had obtained some type of regular status.

23

The wide variation

in data on this topic has made it dicult to achieve a comprehensive, up-to-date understanding of the

situation that would support more eective policy design and implementation. Ongoing eorts to improve

data collection and coordination are thus critical.

Even with this varied data landscape, one thing is clear: the regularized share of Venezuelans varies

considerably from country to country. This reects dierences in what paths to regular status exist,

how widely accessible they are, and the nature of the status they grant. Most of these regularization

mechanisms have oered temporary status, meaning Venezuelans must renew it periodically to avoid

falling into irregular status. Most also do not provide a path to permanent residence. This has emerged as a

fundamental limitation as it has become increasingly clear that many Venezuelans are likely to stay in their

20 Government of Panama, Migración Panama, “Irregulares en tránsito por Darién por país 2022” (data table, 2022).

21 Luciana Gandini, Victoria Prieto Rosas, and Fernando Lozano-Ascencio, “Nuevas movilidades en América Latina: la migración

venezolana en contextos de crisis y las respuestas en la región,” Cuadernos Geográcos 59, no. 3 (July 21, 2020): 103–21.

22 In this section, “regularization” refers to the provision of all kinds of regular migration status. Although asylum is one such route to

regular status, other mechanisms have played a larger role in facilitating Venezuelans’ access to regular status in most countries

in the region. As such, this section largely focuses on other regularization measures. For information about eorts to strengthen

Quito Process Member States’ asylum systems, see Quito Process, “Asilo,” accessed May 10, 2023.

23 Luciana Gandini and Andrew Selee, Betting on Legality: Latin American and Caribbean Responses to the Venezuelan Displacement

Crisis (Washington, DC: MPI, 2023).

MPI and IOM | 10 MPI and IOM | 11

A WINDING PATH TO INTEGRATION A WINDING PATH TO INTEGRATION

host countries.

24

Without a way to apply for a longer-

term or permanent status, hundreds of thousands of

Venezuelans risk sliding back to irregularity and losing

access to basic services and formal employment. This

state of play can also lead to bubbling frustration in

host communities. Other countries (such as Ecuador

25

,

Argentina,

26

Uruguay,

27

and Brazil

28

) allow migrants

to apply for permanent residence, generally after rst

holding a temporary residence permit.

The criteria Venezuelans must meet to be eligible to regularize also vary from country to country and

program to program (see Table 2 for an overview). In a few cases, countries have linked regularization

initiatives to applicants’ employment. For example, Colombia’s Special Permit to Stay for the Promotion of

Formalization (PEPFF) required Venezuelan applicants to be employed and provide proof of a formal job

oer. Meanwhile, Costa Rica’s Special Category of Temporary Workers (CETTSA) set eligibility criteria based

on migrants’ labor sector, rather than their nationality or other characteristics.

29

This process gave migrants

who entered the country between January 2016 and January 2020 and who worked in the agricultural,

agro-export, or agro-industrial sectors a chance to regularize their migration status. When regularization

initiatives oer status only to migrants who can demonstrate their participation in the formal economy,

governments can argue to their constituents that only “productive” or “needed” migrants are being allowed

to stay.

30

However, in places with large informal economies and relatively limited formal employment

opportunities, such mechanisms likely do little to disincentivize migrants from seeking informal work and

employers from hiring them.

Many regularization programs for Venezuelans set a cuto date, allowing only those who entered the

country before a particular date to qualify. This type of requirement generally aims to prevent the

regularization mechanism from becoming a “pull factor,” encouraging further migrants to travel to the

country with the explicit intention of regularizing. Colombia’s TSPV, for example, required Venezuelan

24 Diego Chaves-González, Jordi Amaral, and María Jesús Mora, Socioeconomic Integration of Venezuelan Migrants and Refugees:

The Cases of Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru (Washington, DC, and Panama City: MPI and International Organization for

Migration, 2021).

25 Government of Ecuador, Executive Decree 436 2022 (June 2022).

26 Decree no. 616/2010 regulates the Permanent Mercosur Residency pathway in Argentina for nationals of Mercosur and associated

states, including Venezuelans. See Government of Argentina, “Radicaciones Mercosur - Residencia Permanente,” accessed May 10,

2023.

27 Visa Mercosur allows nationals of Mercosur and associated states, including Venezuelans, to apply for permanent residence in

Uruguay. See Venezolanos en Uruguay, “Residencia permanente Mercosur en Uruguay,” updated September 6, 2020.

28 Interministerial Decree n. 9/2018 regulated the authorization of residence permits to migrants in Brazilian territory and nationals in

a border country, including Venezuelans. Interministerial Decree n. 15/2018 suspended some requirements that applicants present

certain identication documents and accepted self-declaratory statements from Venezuelans. See Government of Brazil, Portaria

Interministerial N

o

9 (March 14, 2018); Government of Brazil, Portaria Interministerial Nº 15 (August 27, 2018).

29 Cristobal Ramón, Ariel G. Ruiz Soto, María Jesús Mora, and Ana Martín Gil, Temporary Worker Programs in Canada, Mexico, and Costa

Rica: Promising Pathways for Managing Central American Migration? (Washington, DC: MPI, 2022).

30 For a discussion of these dynamics, see Demetrios G. Papademetriou, Kevin O’Neil, and Maia Jachimowicz, Observations on

Regularization and the Labor Market Performance of Unauthorized and Regularized Immigrants (Hamburg: HWWA Migration

Research Group, 2004), 9.

Without a way to apply for a longer-

term or permanent status, hundreds

of thousands of Venezuelans risk

sliding back to irregularity and

losing access to basic services and

formal employment.

MPI and IOM | 12 MPI and IOM | 13

A WINDING PATH TO INTEGRATION A WINDING PATH TO INTEGRATION

irregular migrants to show proof of residency in the country before January 31, 2021.

31

Countries such as

Ecuador

32

and Chile

33

have similarly established entry date requirements for migrants seeking to regularize

their status.

Migrants who entered a country with documentation but have since fallen out of regular status are more

likely to have established employment and social networks, increasing their potential productivity and

other post-regularization integration prospects. In part for this reason, some regularization mechanisms

require applicants to prove that they entered the country regularly. However, since most Venezuelans have

ed their country without a passport or other legal documents, many have been unable to enter another

country legally. As a result, such requirements often exclude the vast majority of the Venezuelans who

might otherwise seek to regularize their status.

Apart from creating large-scale regularization mechanisms, countries such as Mexico and the Dominican

Republic have awarded regular status to some Venezuelans based on marriage or other family relationships.

One study of regularization programs in Central America, Mexico, and the Dominican Republic, published

by the International Organization for Migration (IOM), found that having family ties was one of the

most common criteria for regularization processes in the studied countries.

34

This type of regularization

mechanism often operates on a “rolling” basis (rather than within a limited time period), which can help

avoid sharp spikes in demand for application processing and mean governments do not need to announce

(to a potentially skeptical public) their creation of a separate, large-scale regularization measure.

Some countries have sought to regularize Venezuelans who may need some sort of humanitarian protection

but who do not necessarily qualify for refugee status.

35

For instance, Mexico has an Ordinary Migratory

Regularization Mechanism for Humanitarian Reasons, available to people who have petitioned for political

asylum or refugee status, did not receive it, but who nonetheless demonstrate a need for humanitarian

assistance.

36

Brazil, Costa Rica, and Paraguay also have regulations granting status for humanitarian

purposes. Paraguay, for example, granted one-year temporary residency (with the possibility to renew

twice) to Venezuelans due to their vulnerable situation.

37

31 Grupo Interagencial sobre Flujos Migratorios Mixtos (GIFMM) and R4V, “Preguntas y respuestas: Estatuto temporal de protección

para venezolanos” (information sheet, 2021).

32 The Exceptional Temporary Residence Visa (VIRTE) prioritized those Venezuelan migrants who entered the country through

authorized entry points.

33 Chilean Ministry of Interior and Public Security, Ley de Migración y Extranjería, Ley 21325 (April 20, 2021).

34 International Organization for Migration (IOM), Regional Study: Migratory Regularization Programmes and Processes (San Jose: IOM,

2021).

35 The denition of a refugee is “someone who is unable or unwilling to return to their country of origin owing to a well-founded

fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion.” See

UN General Assembly, “Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees,” July 28, 1951. Both Mexico and Brazil have implemented

the Cartagena Declaration’s more expansive criteria for who qualies as a refugee when considering Venezuelans’ asylum cases.

This denition includes “persons who have ed their country because their lives, safety, or freedom have been threatened by

generalized violence, foreign aggression, internal conicts, massive violation of human rights or other circumstances which have

seriously disturbed public order.” See “Cartagena Declaration on Refugees,” Conclusion III, No. 3, November 22, 1984.

36 IOM, Regional Study: Migratory Regularization Programmes and Processes.

37 Paraguayan General Directorate of Migration, Resolución D.G.M. N° 062 (February 1, 2019); Government of Paraguay, Ley de

Migraciones, Ley N° 978/96 (November 8, 1996).

MPI and IOM | 12 MPI and IOM | 13

A WINDING PATH TO INTEGRATION A WINDING PATH TO INTEGRATION

Several countries (such as Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Paraguay, and Peru) have designed mass

regularization mechanisms specically targeting Venezuelans, while other regularization initiatives are open

to migrants of several nationalities. Chile, for instance, established a special visa for Venezuelans known

as the Democratic Responsibility Visa.

38

Peru

39

expanded its regularization process to migrants of other

nationalities, and Ecuador

40

has announced it will similarly extend its regularization mechanism to migrants

of other nationalities in a later phase of the process. Finally, Costa Rica provides legal pathways for migrants

from selected nationalities, including Nicaraguans, Panamanians, and Venezuelans.

Importantly, as noted above, regularization

mechanisms vary in terms of the length of the

status they grant and the rights they convey

to migrants during their stay. Regularization

mechanisms that grant a pathway to

permanent residence and work permits,

as is the case in Colombia, are the most

generous and provide the most support for

migrants’ longer-term integration and related

development goals. Other countries, such as Brazil and Ecuador, initially oer short-term permits but allow

migrants to access long-term residency after their regularization permit expires. In other cases, programs

only grant regular status for a matter of months or years, and there is little or no chance of transitioning

to a more permanent status. Peru’s Temporary Permit of Permanence Card (CPP), for example, only grants

temporary authorization for two years. This can result in migrants falling in and out of regular status, as most

migrants stay even after their temporary status has expired.

The region’s widespread adoption of short-term regularization measures has often resulted in bureaucratic

backlogs for governments, as well as increased obstacles for migrants’ long-term integration. As evidence

suggests that migrants become more productive the longer they spend in a country or in a particular

job, requiring migrants to leave—or allowing them to fall into irregular status—cuts into the potential

economic benets that regularization can oer.

41

At the same time, there is evidence that Venezuelans who

were not regularized at all were pushed further to informal or sometimes illegal activities.

42

Such ndings

suggest that if maximizing migrants’ labor market performance and contributions is a core policy goal, it

is important to design regularization measures in a way that makes them accessible to a broad slice of the

target population and that connects them up to longer-term residence opportunities.

43

38 María José Veiga, Revisión de los marcos normativos de Argentina, Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia, Chile, Perú y Uruguay: contexto del

pacto mundial para una migración segura, ordenada y regular (Buenos Aires: IOM, 2021).

39 United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), “Nuevo CPP: Permiso Temporal de Permanencia,” accessed October 11,

2022.

40 Government of Ecuador, “Pregunta Frecuentes” (information sheet, 2022).

41 Papademetriou, O’Neil, and Jachimowicz, Observations on Regularization, 11–12.

42 World Bank, Migración desde Venezuela a Colombia; World Bank, An Opportunity for All; World Bank, Retos y oportunidades.

43 Soledad Álvarez Velasco, Manuel Bayón Jiménez, Francisco Hurtado Caicedo, and Lucía Pérez Martínez, Viviendo al límite: migrantes

irregularizados en Ecuador (Quito: Colectivo de Geografía Crítica de Ecuador, GIZ and Red Clamor, 2021).

Regularization mechanisms that grant

a pathway to permanent residence and

work permits, as is the case in Colombia,

are the most generous and provide the

most support for migrants’ longer-term

integration and related development goals.

MPI and IOM | 14 MPI and IOM | 15

A WINDING PATH TO INTEGRATION A WINDING PATH TO INTEGRATION

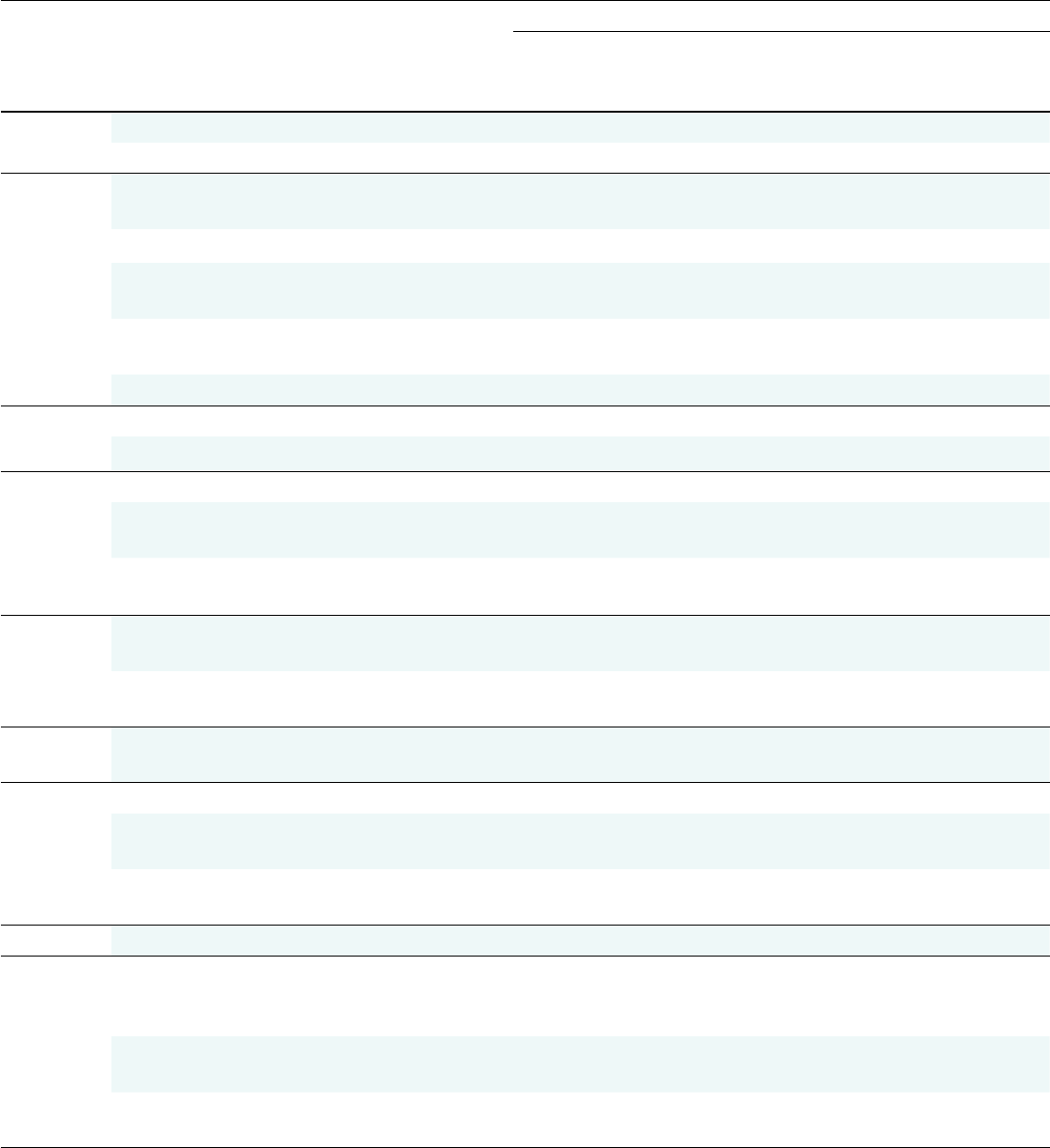

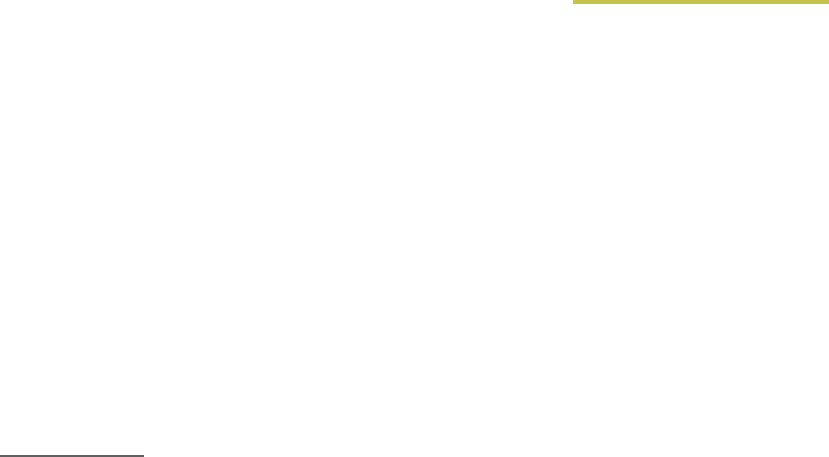

TABLE 2

Past and Present Regularization Mechanisms in Quito Process Member States

Country Regularization Mechanism

Year

Enacted

Requirements

Proof of

Formal

Employment

Entry

before

Cuto Date

Regular

Entry

Family

Ties

Applicant

Nationality

Argentina Temporary Mercosur Residency 2010 No No Yes No Yes

Permanent Mercosur Residency 2010 No No Yes Yes* Yes

Brazil** Normative Resolution CNIg No.

126/2017

2017 No No No No No

Decree No. 9.199/2017 2017 No No No No No

Interministerial Ordinance No.

9/2018

2018 No No No No Yes

Interministerial Ordinance No.

670/2022

2022 No Yes No No Yes

Ordinance No. 28/2022 2022 No Yes No No No

Chile Migratory Regularization Process 2018 No No No No No

Migratory Regularization Process 2021 No Yes Yes No No

Colombia Special Permit to Stay (PEP) 2020 No Yes Yes No Yes

Special Permit to Stay for the

Promotion of Formalization (PEPFF)

2020 Yes No No No Yes

Temporary Statute of Protection for

Venezuelan Migrants (TSPV)

2021 No Yes No No Yes

Costa

Rica**

Special Temporary Complementary

Protection Category

2020 No Yes No No Yes

Special Category for Temporary

Workers (CETTSA)

2020 Yes Yes No Yes No

Dominican

Republic

Resolution 00119-2021 2021 No Yes Yes No Yes

Ecuador Visa UNASUR 2017 No No Yes No Yes

Visa of Exception for Humanitarian

Reasons (VERHU)

2019 No Yes Yes No Yes

Exceptional Temporary Residence

Visa (VIRTE)

2022 No Yes Yes No Yes

Guyana Registration certicates 2019 No No Yes No No

Mexico** Regularization for Having an

Expired Document or Carrying out

Unauthorized Activities

2011 No No Yes No No

Regularization for Humanitarian

Reasons

2011 No No No No No

Regularization by Family

Relationship

2011 No No No Yes No

MPI and IOM | 14 MPI and IOM | 15

A WINDING PATH TO INTEGRATION A WINDING PATH TO INTEGRATION

Panama Executive Decree No. 235 2021 No No No Yes Yes

Paraguay Temporary Residence 2008 No No Yes No Yes

Peru Temporary Residence Permit (PTP) 2017 No Yes Yes No Yes

Special Resident Migratory Status 2018 No No Yes No Yes

Temporary Permit of Permanence

Card (CPP)

2020 No Yes No No No

Humanitarian Migratory Status 2021 No Yes No No Yes

Uruguay Visa Mercosur (Temporary or

permanent)

2014 No No Yes No Yes

* When applying through a relative, based on their status.

** In these three countries (Brazil, Mexico, and to a lesser extent, Costa Rica), asylum systems have been widely utilized to provide regular status and

protection to many Venezuelans. Among these countries, Brazil and Mexico have reported exceptionally high recognition rates. This is due to their

decision to apply the Cartagena Declaration’s broader denition of who is a refugee when processing asylum requests from Venezuelan nationals.

Sources: For Argentina, Ministry of the Interior, “Tramitar residencia temporaria -radicaciones Mercosur,” accessed May 10, 2023; Ministry of the

Interior, “Radicaciones Mercosur - Residencia Permanente,” accessed May 10, 2023. For Brazil, Government of Brazil, Resolução Normativa CNIg

N

o

126 (March 3, 2017); Government of Brazil, Portaria Interministerial N

o

9 (March 14, 2018); Government of Brazil, Resolução Normativa N

o

29

(October 29, 2019); Government of Brazil, Portaria Interministerial N

o

670 (April 1, 2022); Government of Brazil, Portaria N

o

28 (March 11, 2022). For

Chile, Government of Chile, “Proceso de regularización de migrantes se inició en todo Chile,” updated April 23, 2018; Chile Atiende, “Regularización

Migratoria 2021” (information sheet, November 4, 2021); Ministry of Foreign Aairs of Chile, “Visa de responsabilidad democrática continúa apoyando

a miles de venezolanos y venezolanas,” accessed October 6, 2022. For Colombia, Migración Colombia, Resolución 2359 de 2020 (September 29, 2020);

Migración Colombia, Resolución 289 de 2020 (January 30, 2020); Centro de Estudios Regulatorios, “MinRelaciones Exteriores, Decreto 216 de 2021,”

accessed May 10, 2023; Government of Colombia, “Migrantes venezolanos podrán tramitar su permiso especial de permanencia (PEP) de manera

gratuita,” updated January 31, 2020; Grupo Interagencial sobre Flujos Migratorios Mixtos (GIFMM) and R4V, “Preguntas y respuestas: Estatuto temporal

de protección para venezolanos” (information sheet, 2021); Ministry of Labor, “Permiso especial de permanencia para el fomento de la formalización-

PEPFF,” accessed October 4, 2022. For Costa Rica, Lexology, “Costa Rica: Régimen excepcional para la regularización migratoria de trabajadores del

sector agropecuario, agroexportador o agroindustrial,” accessed July 19, 2023; Diego Chaves-González and María Jesús Mora, The State of Costa Rican

Migration and Immigrant Integration Policy (Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute, 2021); Government of Costa Rica, Decreto N° 42406-MAG-

MGP (June 23, 2022). For the Dominican Republic, Government of the Dominican Republic, Resolución 00119-2021 (January 19, 2019). For Ecuador,

Government of Ecuador, “Emisión de visa temporal Unasur” (information sheet, 2017); Government of Ecuador, “Manual de proceso para el usuario

de consulado virtual - proceso de aplicación de visas de excepción por razones humanitarias” (information sheet, 2019); Venezuela en Ecuador,

“Preguntas Frecuentes,” accessed May 10, 2013. For Guyana, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), “Guyana es pionera en el uso

de tecnología de avanzada para ayudar a los venezolanos,” accessed October 13, 2022. For Mexico, National Institute of Migration, “Regularización

por tener documento vencido o realizar actividades no autorizadas,” accessed May 10, 2023; Info Digna, “¿Sabías que puedes regularizar tu situación

migratoria en México?,” updated May 2022; Government of Mexico, “Regularization for Humanitarian Reasons” (information sheet, November 8, 2012);

Government of Mexico, “Regularization by Family Relationship” (Information sheet, November 8, 2012). For Panama, Government of Panama, Decreto

Ejecutivo No. 235 (September 15, 2021); Chen Lee & Asociados, “Regularización migratoria en Panamá,” accessed October 13, 2022. For Paraguay, Ley

Nº 3565 / Aprueba El Acuerdo Sobre Residencia Para Nacionales De Los Estados Partes Del Mercosur (July 17, 2013); Government of Paraguay, “Radicación

temporaria para venezolanos,” accessed October 12, 2022. For Peru, Government of Peru, Decreto Supremo N°002-2017-IN (January 3, 2017);

Government of Peru, Resolución de Superintendencia N° 043 (January 30, 2018); UNHCR, “Nuevo CPP: Permiso Temporal de Permanencia,” accessed

October 11, 2022; Government of Peru, Resolución Ministerial (June 16, 2021). For Uruguay, Venezolanos en Uruguay, “Residencia permanente

Mercosur en Uruguay,” updated September 6, 2021.

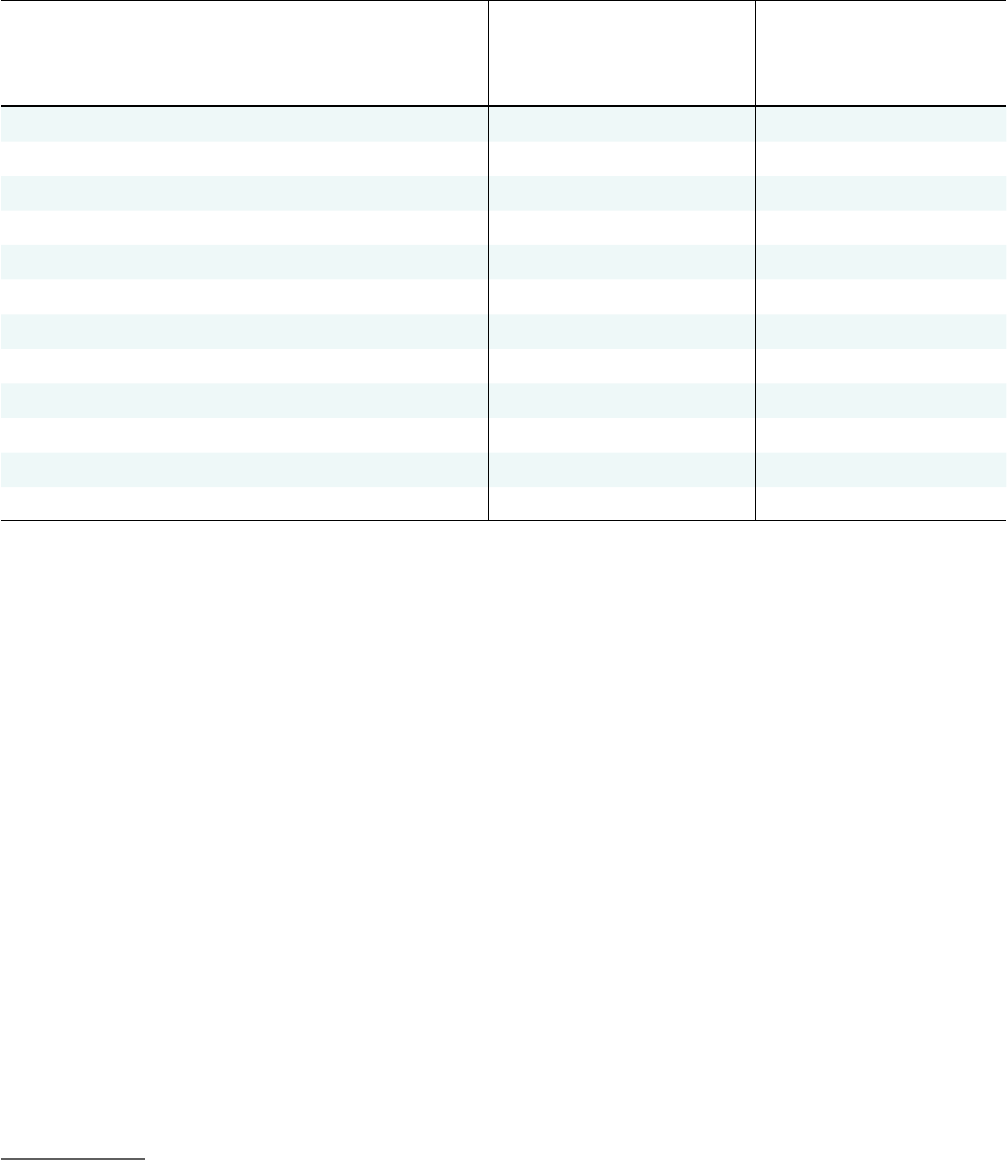

TABLE 2 (cont.)

Past and Present Regularization Mechanisms in Quito Process Member States

Country Regularization Mechanism

Year

Enacted

Requirements

Proof of

Formal

Employment

Entry

before

Cuto Date

Regular

Entry

Family

Ties

Applicant

Nationality

MPI and IOM | 16 MPI and IOM | 17

A WINDING PATH TO INTEGRATION A WINDING PATH TO INTEGRATION

3 Venezuelans’ Regularization and Labor Market

Integration in Colombia

Colombia’s most recent regularization initiative, known as the Temporary Statute of Protection for

Venezuelan Migrants (TSPV), was launched in 2021. It oers status that lasts for ten years and has been

widely praised for its comprehensive, long-term strategy to fully integrate an estimated 2.4 million

Venezuelan migrants in Colombia.

44

As such, the initiative is the largest and most-studied regularization

mechanism among those created by Quito Process Member States.

The TSPV applies to Venezuelans in several migratory situations. First, it extends the status of migrants who

had already regularized through the Special Permit to Stay (PEP). It also grants regular status to migrants in

the process of applying for a visa. Migrants with irregular status who can prove that they entered Colombia

before January 31, 2021, can also apply for TSPV. Lastly, any Venezuelan who entered the country regularly

before May 28, 2023, is eligible to apply.

45

In addition to promoting regularization, the decree that

created TSPV (Decree 216 of 2021) had the stated aim of

promoting employers’ hiring of Venezuelans to reduce

their high levels of informality compared to the local

population.

46

While 46.8 percent of labor in Colombia

overall was informal in 2021,

47

the rate of informality for

Venezuelans was much higher, between 71.9

48

and 89.6

percent.

49

This particular component of the TSPV followed previous attempts to tackle labor informality through a

specic work permit called the Special Permit to Stay for the Promotion of Formalization (PEPFF). The aim

was to provide companies with the tools to formally hire Venezuelans by enabling them to request this

permit from the Colombian Ministry of Labor.

The TSPV stipulates that, to work formally in Colombia, Venezuelans must be regularized and meet the same

professional requirements as Colombian nationals. Any title a Venezuelan migrant obtained abroad needs to

undergo a process of validation, and the worker must receive all the relevant provisional permits or licenses,

registration, professional cards, or proof of experience from the responsible professional associations or

authorities. Correspondingly, employers have a list of obligations they must follow when hiring Venezuelans.

44 As of August 2023, a total of 2,484,241 Venezuelans had been registered, but only 1,805,786 had received the permit. See

Migración Colombia, “ETPV,” accessed September 8, 2023.

45 Government of Colombia, “Abecé del Estatuto Temporal de Protección para migrantes venezolanos” (information sheet, March 5,

2021).

46 Government of Colombia, Decreto 216 (March 1, 2021).

47 Colombian National Administrative Department of Statistics (DANE), “Medición de empleo informal y seguridad social: trimestre

octubre - diciembre 2021” (technical bulletin, 2022).

48 Colombian National Planning Department (DNP), Informe nacional de caracterización de población migrante de Venezuela (Bogotá:

DNP, 2022).

49 R4V, “Mercado Laboral de los refugiados y migrantes provenientes de Venezuela,” accessed May 10, 2023. The authors used

Information on that site that is based on DANE, “Boletín Técnico Gran Encueta Nacional Integrada de Hogares” (survey data,

October 2021). These data measure social security coverage.

While 46.8 percent of labor in

Colombia overall was informal in

2021, the rate of informality for

Venezuelans was much higher,

between 71.9 and 89.6 percent.

MPI and IOM | 16 MPI and IOM | 17

A WINDING PATH TO INTEGRATION A WINDING PATH TO INTEGRATION

One such requirement is that employers must register foreign workers in a platform created by the Ministry

of Labor, called the Single Registry of Foreign Workers in Colombia (RUTEC). This online registration system

informs the ministry of the location and economic sector in which hired foreigners are working, with the

purpose of enabling the ministry to supervise their working conditions. Similarly, Migración Colombia has

developed the Report of Foreigners Information System (SIRE) to promote compliance with national labor

regulations.

Much of the ocial government information about Venezuelan migrants in Colombia comes from three

institutions observing the integration process of regularized migrants: the National Planning Department

(DNP)’s National Migration Observatory,

50

the National Administrative Department of Statistics (DANE),

51

and Migración Colombia. Each has collected data characterizing the migrant population in order to build

understanding of migrants’ living conditions and help design better, more evidence-informed policies.

Although these institutions do not have indicators that track migrants’ labor market experiences at dierent

points of the migration and integration process, their datasets do oer an overview of a population

about which it is notoriously dicult to collect reliable information. For instance, Migración Colombia’s

Characterization Survey 2021–22 collected various types of information about TSPV holders, but it did

not ask certain questions that would have shed light on how their integration was progressing (e.g., what

specic sectors they were working in). Thus, while the survey oers valuable insights into the skills these

migrants bring to the Colombian economy, the data cannot be used to gauge whether they have been able

to nd jobs that make use of those skills.

This section of the report examines these and other sources of data on both the regularized and

unregularized population, as well as on Venezuelan workers in general.

52

Based on analysis of the available

evidence on Colombia’s PEP and TSPV regularization programs, it highlights key ndings about the

programs’ impacts on the labor market outcomes of Venezuelans.

Finding 1: Venezuelans who have lived in the country for ve years or longer have a higher

employment rate than more recent arrivals, but informality among migrant workers remains

widespread.

Venezuelan migrants have generally reported lower rates of formal employment than the overall Colombian

population. However, unemployment rates for migrants in Colombia (the majority of whom are Venezuelan)

dropped in 2021 and 2022, a similar trend to that of the local population.

53

50 This is a tool of the national government to organize, analyze, and socialize information about Venezuelan migration with a

territorial approach. It is used for making decisions about and designing adequate responses to migrant needs for assistance and

integration support. See DNP, “Observatorio de migración desde Venezuela - OMV,” accessed October 6, 2022.

51 It is important to note that the analysis and data provided by DANE incorporate Colombian returnees, in addition to Venezuelan

migrants, within their gures and indicators.

52 Konrad Adenauer Stiftung (KAS) and Fundación Ideas para la Paz (FIP), Entendiendo La Mirada Empresarial Frente al Fenómeno

Migratorio En Colombia (Bogotá: KAS and FIP, 2021); ILO, IOM, and UNHCR, Estudio de mercado laboral con foco en la población

refugiada y migrante venezolana y colombianos retornados en las ciudades de Riohacha, Bucaramanga, Cali, Cúcuta, Bogotá,

Barranquilla y Medellín (Bogotá: ILO, IOM, and UNHCR, 2022); Ana María Ibáñez et al., Salir de la sombra: cómo un programa de

regularización mejoró la vida de los migrantes venezolanos en Colombia (Bogotá: Inter-American Development Bank, 2022).

53 DANE, Mercado Laboral. Principales Resultados (Bogotá: DANE, 2022).

MPI and IOM | 18 MPI and IOM | 19

A WINDING PATH TO INTEGRATION A WINDING PATH TO INTEGRATION

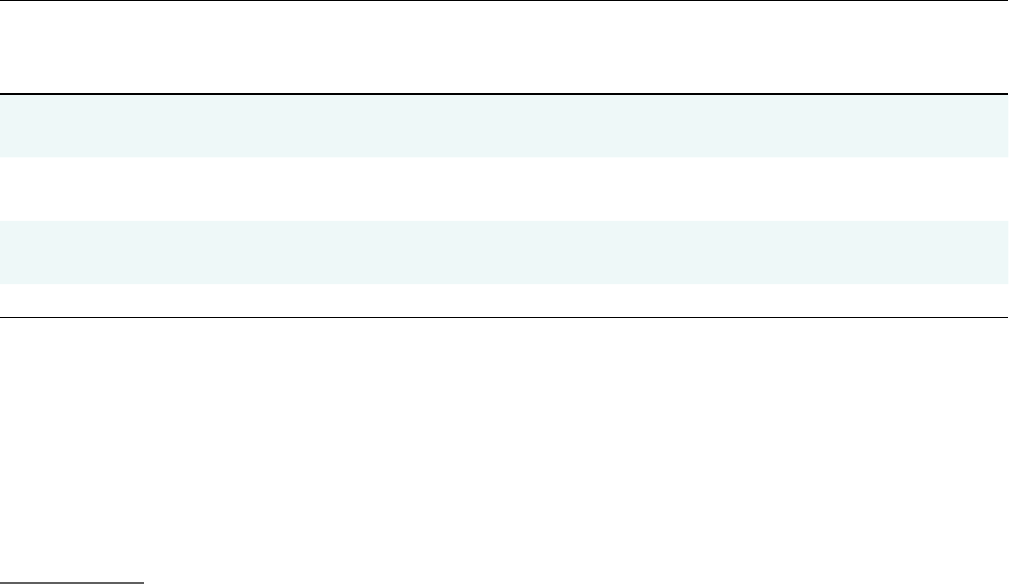

Data suggest that Venezuelans’ employment prospects are closely tied to how long they have been in the

country. The unemployment rate for migrants who arrived at least ve years ago is very similar to the rate

for Colombians, but unemployment is much higher among Venezuelans who arrived in the country less

than a year ago (see Table 3).

According to migrants and employers who participated in this study’s focus groups and interviews,

54

this

could be partly due to the fact that migrants who have lived in Colombia for longer are more likely to have

beneted from one of the regularization permits, which facilitated access to work.

55

Moreover, having spent

a longer time in the country has allowed them to establish support networks that can open up employment

opportunities. Some focus group participants also suggested that the economic recovery after the initial

pandemic-induced shock could have contributed to the increase in employment rates in 2021 and 2022.

TABLE 3

Unemployment Rates for Nationals vs. Immigrants in Colombia, 2021–22

Year

Nationals’

Unemployment Rate

Migrants

Years in Colombia Unemployment Rate

2021 11.1%

Less than 1 25.8%

More than 5 13.7%

2022 10.3%

Less than 1 19.8%

More than 5 11.2%

Sources: DANE, Mercado Laboral. Principales Resultados (Bogotá: DANE, 2022); DANE, “Principales indicadores del mercado laboral

diciembre de 2021” (technical bulletin, January 31, 2022).

With the TSPV, Colombia has also managed to register a signicant number of Venezuelan migrants with

social services such as the General Social Security Health System (SGSSS) and skills certication processes.

Data from June 2019 indicate that most Venezuelans registered with SGSSS were aliated with the

contributory system, under which individuals with nancial capacity or employers directly pay, while 36

percent were able to access subsidized health care due to their nancial vulnerability. Interestingly, by 2022,

many more migrants had been registered, and 68 percent were aliated with the subsidized system.

56

This

suggests that many migrants in Colombia work in informal, precarious situations. Thus, while regularization

eorts may be opening some opportunities (e.g., to access public services), they are not necessarily leading

to direct access to better jobs in the formal sector. And since the country has taken expansive steps to

regularize Venezuelan migrants,

57

those who remain irregular or are still waiting for their regularization IDs

to be issued may nd fewer assistance measures targeted to them (e.g., support nding a job or certifying

their labor competencies).

54 Participant comments during an MPI online focus group with Venezuelan migrants in Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru, August 22,

2022; authors’ interviews with private-sector representatives, July and September 2022.

55 Participant comments during MPI focus groups with Venezuelan migrants, employers, and civil society, December 2022.

56 DNP, “Personas venezolanas con documento PEP y PPT aliadas al Sistema General de Seguridad Social en Salud (SGSSS) –

Aliados totales por cada mes del año” (dataset, 2022).

57 Authors’ interview with a representative of the Colombian Border Manager’s Oce, August 2022.

MPI and IOM | 18 MPI and IOM | 19

A WINDING PATH TO INTEGRATION A WINDING PATH TO INTEGRATION

Finding 2: Venezuelans’ salaries vary widely, and they oen receive fewer labor benets in

comparison to their Colombian counterparts.

There are notable gaps in the labor conditions for and benets received by Colombia’s native-born and

migrant workers. Venezuelans in Colombia, for example, are more likely than Colombians to have a verbal

contract with their employer (rather than a formalized, written one), pay less in pension contributions,

and receive less income for the same jobs.

58

Moreover, Venezuelans work many more hours on average

than other workers in the country, likely resulting in lower hourly pay rates compared to their Colombian

counterparts.

However, there are signicant dierences in Venezuelans’ earnings depending on how long they have lived

in Colombia (see Table 4). The average income of Venezuelans who have been in the country for more than

ve years is higher than that of other workers (most of whom are Colombian, though the data also include

a small number of other migrants). Their income is also considerably higher than that of Venezuelans who

have been in the country for less time. A 2022 study from the Colombian research organization Dejusticia

estimated that Venezuelans who have lived in Colombia for more than ve years earn around USD 540 per

month; Venezuelans who have resided in Colombia for between one and ve years earn approximately USD

213; and those who have lived in the country for less than a year earn around USD 153.

59

TABLE 4

Labor Conditions and Income for Workers in Colombia, by Nativity and Length of Residence, 2022

Persons

not Born in

Venezuela*

Venezuelans in

Colombia for 5+

Years

Venezuelans in

Colombia for 1–5

Years

Venezuelans in

Colombia for Less

than 1 Year

% of Workers with Verbal

Contracts

35% 52% 81% 91%

% of Workers Contributing to

Pension Fund

40% 29% 10% 1%

% of Workers with a

Severance Payment

60% 37% 21% 11%

Average Income USD 313 USD 540 USD 213 USD 153

* The vast majority of non-Venezuelans in the data presented here are Colombian, though a very small minority are immigrants from

other countries. Still, these data can be used broadly to compare trends for Venezuelan vs. Colombian workers.

Note: The authors converted income gures from Colombian pesos to U.S. dollars, using the ocial exchange rate on July 31, 2021

(USD 1.00 = COP 4300.3).

Sources: Cristina Escobar Correa, Diego Escallón Arango, and Laura Cifuentes Rosales, Análisis de la garantía de derechos a La educación,

salud e inclusión laboral de la población migrante de Venezuela en Colombia (Bogotá: Danish Refugee Council, 2021); Lucía Ramírez

Bolívar, Lina Arroyave Velásquez, and Jessica Corredor Villamil, Ser migrante y trabajar en Colombia: ¿Cómo va la inclusión laboral de las

personas provenientes de Venezuela? (Bogotá: Dejusticia, 2022).

58 Cristina Escobar Correa, Diego Escallón Arango, and Laura Cifuentes Rosales, Análisis de la garantía de derechos a La educación,

salud e inclusión laboral de la población migrante de Venezuela en Colombia (Bogotá: Danish Refugee Council, 2021).

59 Lucía Ramírez Bolívar, Lina Arroyave Velásquez, and Jessica Corredor Villamil, Ser migrante y trabajar en Colombia: ¿Cómo va la

inclusión laboral de las personas provenientes de Venezuela? (Bogotá: Dejusticia, 2022).

MPI and IOM | 20 MPI and IOM | 21

A WINDING PATH TO INTEGRATION A WINDING PATH TO INTEGRATION

It is likely that multiple factors contribute to these income dierences among Venezuelans. Firstly, as

Venezuelans stay in the country longer and develop deeper roots, they tend to earn more. Additionally,

evidence suggests that Venezuelans who arrived in Colombia more than ve years ago had higher levels

of education than more recent newcomers, likely helping many to nd employment in professional

occupations before migration levels began to increase sharply.

60

However, the rise in Venezuelan workers’

wages over time also coincided with Colombia’s various eorts to regularize the migratory status of

Venezuelans, suggesting that regularization could play a role in increasing pay. One notable example is

the PEP RAMV (Special Permanence Permit for Venezuelan Migrants) that was implemented in 2018 to

regularize approximately half a million Venezuelan irregular migrants. A study conducted by the Inter-

American Development Bank in 2022 revealed that PEP RAMV holders had a monthly income ranging

from 1 percent to 31 percent higher than that of irregular migrants, highlighting the positive impact of

regularization on their economic well-being.

61

Finding 3: Venezuelans represent an important human capital asset for Colombia, and one

that regularization could help the country more fully leverage.

Venezuelans in Colombia are a highly educated population, even though more recent arrivals have a lower

average education level than Venezuelan migrants who arrived before them. In 2016, almost 45 percent of