Counterpoint Global Insights

Turn and Face the Strange

Overcoming Barriers to Change in Sports and Investing

CONSILIENT OBSERVER | September 8, 2021

Introduction

A reasonable presumption is that organizations want to succeed in

their purpose. The measure of success is different across fields

and often has absolute and relative metrics. Professional sports

franchises strive to field teams that win and are profitable.

1

Investment management organizations seek to generate excess

returns for their investors while fostering a healthy business.

2

One of the challenges in attaining and maintaining organizational

success is that conditions change. Some changes are external,

such as the rules for a league or economic conditions for a

company. Others are internal, such as personnel or the quality of a

strategy. As a result, organizations have to learn and adapt. Those

that do may thrive and those that don’t risk becoming obsolete.

Organizational learning and adaptation allow leaders to make

better decisions. Philosophers discuss two sources of error in

decision making.

3

One is the result of limited knowledge. For

example, the medical community may not have developed a drug

to cure a specific disease or a surgical procedure to treat a patient.

The second source of error is the failure to implement what is

already known. For instance, there are more than 20,000 deaths

from medical error in U.S. hospitals each year.

4

Checklists are one

way to make sure that what is known is faithfully applied.

5

Employees for sports organizations include the playing team

(players, coaches, and scouts) and the business side (marketing,

communications, and operations). The organization then seeks to

implement a system, through strategies and supporting tactics, in

an effort to win. Great players are critical to success. Teams can

acquire players through the amateur draft, by trading for them, or

via free agency. The goal is to have a good fit between the skills of

the players and the system. Great organizations develop a

framework for decision making that serves the goal of winning.

Investment firms are similar to sports teams in many ways.

6

AUTHORS

Michael J. Mauboussin

michael.mauboussi[email protected]om

Dan Callahan, CFA

dan.callahan1@morganstanley.com

© 2023 Morgan Stanley. All rights reserved.

5980321 Exp. 09/30/2024

2

Player evaluation and skill building are essential to the success of any sports organization. The ability to apply

analytics to talent evaluation varies based on factors such as whether the action is discrete or has interaction,

whether the sport itself has continuous play or stops and starts, the length of the season, and the sample size

of scoring opportunities.

7

That noted, there is evidence that player evaluation remains inefficient as the result of

analytical limitations and cognitive biases.

8

Sports teams attempt to maximize their outcomes in the face of resource constraints. These include payroll

maximums and minimums, luxury taxes, and the willingness of owners to spend money. In some sports,

superstars play an outsized role in success. In others, the weakest players contribute more to wins and losses.

9

In superstar sports, such as the National Basketball Association (NBA), the top 3 players, 20 percent of the

roster, can earn two-thirds or more of the total payroll. In the National Football League (NFL), quarterbacks are

the top 10, and 13 of the top 15, paid players.

10

Building a roster is a lot like building a portfolio. Teams would like to sign players with a value higher than their

price. Concentrating the payroll on a few players is akin to having an undiversified portfolio, with higher risk and

higher potential reward. Managers must dynamically assess the constituents because their prices and value

change all of the time. And elements such as turnover and time horizon are vital contributors to results.

The first question to ask in any organization is: what contributes to winning? Managers should seek to answer

this analytically, which will lead to certain types of players, strategies, and tactics. For many teams, the response

to this question creates an inevitable tension between what organizations have always done and potential new

ways of doing things. As one player development professional summarized it, “Your number one tool . . . is not

playing experience, it is a growth mindset that allows you to be curious and take advantage of all of the

information that is readily available.”

11

Success requires evolution because the world changes.

In 2020, Richard Thaler, a professor of economics at the University of Chicago and the 2017 recipient of the

Nobel Prize in Economics, gave a talk at the MIT Sloan Sports Analytics Conference titled “The Sports Learning

Curve: Why Teams are Slow to Learn and Adapt.” He reviewed a number of strategies that have been shown

to be effective analytically but that teams have been slow to adopt. Examples include reducing the rate of bunts

and base stealing in Major League Baseball (MLB), increasing the rate of 3-point shots in the NBA, and going

for it on fourth down in the NFL.

12

Peak performance is important because this is big business. The average MLB (MLB) franchise is worth $1.9

billion, the average NBA franchise $2.2 billion, and the average NFL franchise $3.5 billion.

13

And winning is a

factor that contributes to franchise value.

14

You need not know anything about sports to appreciate the point that there was useful knowledge that took a

long time to implement. In some cases, the knowledge has yet to be applied. This report examines the barriers

to change. We use sports, and the NBA in particular, as the prime example but then apply the lessons to

investment management. These impediments to change afflict all organizations to some degree.

© 2023 Morgan Stanley. All rights reserved.

5980321 Exp. 09/30/2024

3

Innovation: When Three > Two

In the 1979/80 season, the NBA introduced a line behind which a player would score three points, rather than

two, for a made shot.

15

The line is 23.75 feet from the basket, except in the corners, where it is 22 feet away in

order to accommodate the court’s 50-foot width.

The shot was a novelty. Larry Bird, one of the NBA’s all-time greatest players, said, “It’s strange when you think

back. I can’t remember even practicing the shot, unless it was for the [annual 3-point shooting] contest. I really

didn’t take that many, compared to today.”

16

If Bird wasn’t working on the shot, neither were many others of the era. As a result, fewer than three percent of

all field goal attempts were from 3-point range in the five seasons following the shot’s introduction. Exhibit 1

shows the evolution of 3-point shooting over time. There is a kink from the 1994/95 through 1996/97 seasons

because the NBA briefly shortened the overall distance of the line. The intrepid players who did shoot from that

range in the early days made only a little more than 25 percent of them, for an expected value per shot of 0.76.

2-point attempts succeeded close to half of the time for an expected value of 0.99. Today, even the teams with

the worst 3-point shooting percentage make more than one-third of their long-range shots.

Exhibit 1: Percent of Field Goal Attempts That Were 3-Pointers, 1979/80–2020/21

Source: Sports Reference LLC, " NBA League Averages-Per Game," Basketball-Reference.com-Pro Basketball Statistics

and History, www.basketball-reference.com, August 2021.

Over time, the combination of skill identification and practice made it clear that 3-point shots could have an

attractive expected value. Players improved their shooting percentage from that range, and 3-pointers finally

had a higher expected value than 2-pointers about a dozen years after the initiation of the line (see exhibit 2).

This is the point at which it became clear that 3-point shots were an opportunity.

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

1979/80

1980/81

1981/82

1982/83

1983/84

1984/85

1985/86

1986/87

1987/88

1988/89

1989/90

1990/91

1991/92

1992/93

1993/94

1994/95

1995/96

1996/97

1997/98

1998/99

1999/00

2000/01

2001/02

2002/03

2003/04

2004/05

2005/06

2006/07

2007/08

2008/09

2009/10

2010/11

2011/12

2012/13

2013/14

2014/15

2015/16

2016/17

2017/18

2018/19

2019/20

2020/21

Percent of Total Field Goal Attempts

© 2023 Morgan Stanley. All rights reserved.

5980321 Exp. 09/30/2024

4

Exhibit 2: The Value of 2- and 3-Pointers, 1979/80–2020/21

Source: Sports Reference LLC, " NBA League Averages-Per Game," Basketball-Reference.com-Pro Basketball Statistics

and History, www.basketball-reference.com, August 2021.

Kirk Goldsberry, a basketball writer who also teaches at the University of Texas, has done extensive and visually

powerful work on the evolution of shooting in the NBA. He shows that the story is more subtle than three is better

than two.

Very simplistically, you can classify 2-point shots as close or mid-range. Close shots are within or near the

restricted area, which is a four-foot arc underneath the basket. Mid-range shots are essentially those that are

neither close nor 3-pointers.

Close shots have an expected value in excess of 1.2 because they are often dunks or layups that the players

make a high percentage of the time. Mid-range shots have an expected value of 0.85-0.90 in the middle of the

lane, an area from the free throw line to the baseline and 16 feet wide. But mid-range shots from 8 to 21 feet

have an expected value of less than 0.85.

17

3-point shots have an expected value of about 1.1 overall with a slightly higher value in the corners, which are

closer to the basket. Exhibit 2 shows that the expected value of 3-pointers was 14 percent higher than 2-pointers

in the 2003/04 season. The natural way to arbitrage that expected value differential is to take more 3-point shots

and fewer mid-range 2-point shots.

Exhibit 3 shows that is precisely what happened. A quarter century ago, about 40 percent of shots were mid-

range 2-pointers and 10 percent were 3-pointers. Today, those totals have nearly flipped. As a result, the gap in

expected value between 3-pointers and 2-pointers is now less than four percent.

Daryl Morey, president of basketball operations for the Philadelphia 76ers and a leader in basketball analytics,

“estimated that, at its inception, the strategy of taking more 3s at the expense of mid-range jumpers resulted in

approximately 12 more wins a year, roughly equivalent to spending $30 million more a year on star players.”

18

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

1.0

1.1

1.2

1979/80

1980/81

1981/82

1982/83

1983/84

1984/85

1985/86

1986/87

1987/88

1988/89

1989/90

1990/91

1991/92

1992/93

1993/94

1994/95

1995/96

1996/97

1997/98

1998/99

1999/00

2000/01

2001/02

2002/03

2003/04

2004/05

2005/06

2006/07

2007/08

2008/09

2009/10

2010/11

2011/12

2012/13

2013/14

2014/15

2015/16

2016/17

2017/18

2018/19

2019/20

2020/21

Average Points Per Attempt

3-Pointers

2-Pointers

3-Pointers

2-Pointers

© 2023 Morgan Stanley. All rights reserved.

5980321 Exp. 09/30/2024

5

Exhibit 3: Mid-Range and 3-Point Shot Attempts, 1996/97–2020/21

Source: www.nba.com/stats.

To bring the point home, Goldsberry’s analysis by shot distance shows that a 21-foot shot has an expected value

of less than 0.80 while shots a foot longer in the corner, and 2.75 feet longer everywhere else, are worth about

40 percent more. Note that the 3-point shot has been around for 40 years, but it has been fully embraced only

in the last decade or so. Exhibit 4 shows how the top 200 shot locations has changed from the 2001/02 season

to the 2019/20 season. What used to be a potential source of edge has now become the ante to play the game

competitively.

Exhibit 4: Top 200 Shot Locations in the NBA, 2001/02 versus 2019/20

Source: Kirk Goldsberry.

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

1996/97

1997/98

1998/99

1999/00

2000/01

2001/02

2002/03

2003/04

2004/05

2005/06

2006/07

2007/08

2008/09

2009/10

2010/11

2011/12

2012/13

2013/14

2014/15

2015/16

2016/17

2017/18

2018/19

2019/20

2020/21

Percentage of Total Field Goal Attempts

3-Pointers

Mid-Range

3-Pointers

Mid-Range

© 2023 Morgan Stanley. All rights reserved.

5980321 Exp. 09/30/2024

6

The inefficiency associated with the 3-point shot has now been largely competed away. But it turns out there

may be new frontiers in basketball where analysis suggests an approach that is different than the conventional

wisdom. One illustration is the strategy and tactics of offensive rebounding. An offensive rebound is when a

team gains possession of the ball after it misses a shot, which extends the possession and resets the shot clock

to 14 seconds.

Offensive rebounds are obviously good. But if a coach instructs most of the players to try to secure an offensive

rebound and they fail, the team becomes vulnerable as it transitions from offense to defense because it has

fewer players back to defend. The dogma among coaches is that most players should not pursue offensive

rebounds. One coach’s message to his perimeter players was, “We don't care if you get an offensive rebound

in your entire life.”

19

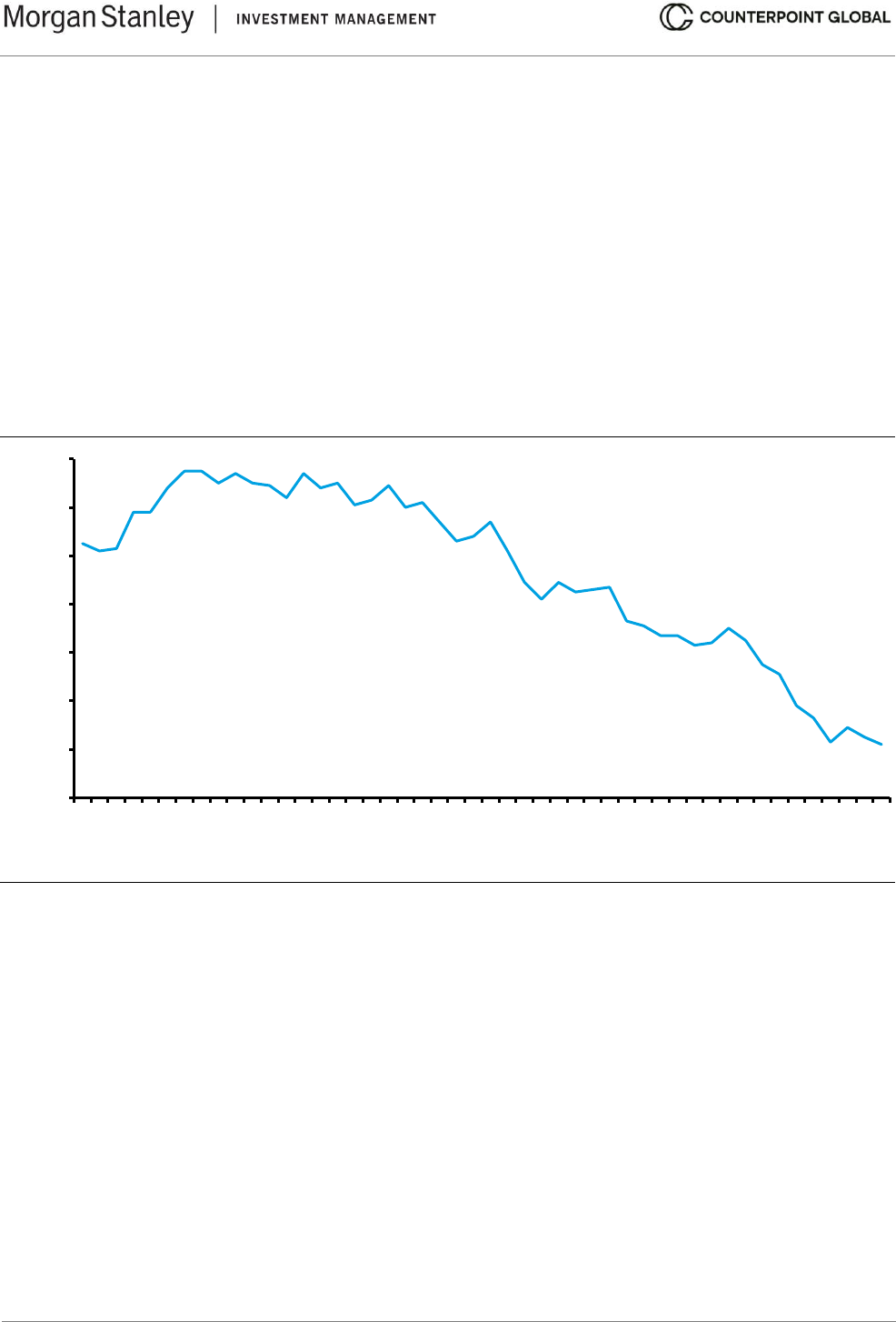

Exhibit 5 shows a steady decline in the percentage of rebounds secured by the offense.

Exhibit 5: Offensive Rebound Percentage, 1973/74–2020/21

Source: Sports Reference LLC, " NBA League Averages-Per Game," Basketball-Reference.com-Pro Basketball Statistics

and History, www.basketball-reference.com, August 2021.

Research that relies on tracking data that have been available only relatively recently shows that more

aggressive offensive rebounding may create an edge.

20

After making some tactical adjustments, sending more

players to rebound can create a benefit on offense that is greater than its cost on defense. If this proves to be

true, it will provide another test of organizational change.

20

22

24

26

28

30

32

34

1973/74

1974/75

1975/76

1976/77

1977/78

1978/79

1979/80

1980/81

1981/82

1982/83

1983/84

1984/85

1985/86

1986/87

1987/88

1988/89

1989/90

1990/91

1991/92

1992/93

1993/94

1994/95

1995/96

1996/97

1997/98

1998/99

1999/00

2000/01

2001/02

2002/03

2003/04

2004/05

2005/06

2006/07

2007/08

2008/09

2009/10

2010/11

2011/12

2012/13

2013/14

2014/15

2015/16

2016/17

2017/18

2018/19

2019/20

2020/21

Offensive Rebound Percentage

© 2023 Morgan Stanley. All rights reserved.

5980321 Exp. 09/30/2024

7

What Impedes Change?

It is important to acknowledge that most teams in professional sports have made substantial strides in the right

direction.

21

This includes both player evaluation and on-field strategy. But there remains a lot of room to improve

decision making. Here are some of the impediments to better decisions:

1. Loss aversion. Loss aversion is the idea that we suffer losses more than equal gains. As a result, we

tend to avoid situations where we can be potentially wrong. This is especially relevant when the decision

runs against conventional wisdom.

The decisions that contribute to the ups and downs of professional sports teams are subject to intense

scrutiny by fans and the media. Most teams are under enormous pressure, especially those that are

expected to win. General managers (GMs) and coaches are exposed to the wrath of outsiders when they

make a personnel or on-field decision that has a poor outcome. As a result, it is often easier to be

conventional than unconventional, even if being different from the crowd is likely to increase the chance

of winning.

Paul DePodesta, a protagonist in the book Moneyball and now the chief strategy officer for the Cleveland

Browns of the NFL, says that owners indicate that “we want this disciplined approach to what we’re doing.

But then when it comes time to making that hard decision, they say, ‘I don’t want any part of this.’”

He compares the decision-making process, with its inevitable successes and failures, to riding on a big

and terrifying roller coaster. He discusses the ideal owner: “I need someone who’s going to want to get on

the roller coaster with me knowing that it's not always going to be fun. There are going to be parts of the

roller coaster that are going to be scary, that are going to be uncomfortable, but hopefully at the end of

the ride when we get off, you’re going to want to say, let’s do that again.”

22

Successful long-term decision makers, including investors, are familiar with the ups and downs that come

with a successful long-term record. John Maynard Keynes, an economist, wrote this about long-term

investors: “For it is in the essence of his behaviour that he should be eccentric, unconventional and rash

in the eyes of average opinion. If he is successful, that will only confirm the general belief in his rashness;

and if in the short run he is unsuccessful, which is very likely, he will not receive much mercy. Worldly

wisdom teaches that it is better for reputation to fail conventionally than to succeed unconventionally.”

23

We posit that teams and organizations are willing to experiment with new approaches when they have

been very unsuccessful or highly successful (see exhibit 6). Loss aversion is less of an issue following a

stretch of failure because there is little room to get worse. Consistent with this is the notion that underdogs

should try new and unusual strategies in order to increase variance when they compete with a stronger

team that is the favorite to win.

24

© 2023 Morgan Stanley. All rights reserved.

5980321 Exp. 09/30/2024

8

Exhibit 6: The Pattern of Experimentation

Source: Counterpoint Global. For illustrative purposes only.

Winning teams are also freer to experiment because they have accumulated goodwill with the fans, media,

and owners that provides cover for greater risk-taking. Take the example of Bill Belichick, the head coach

of the New England Patriots and one of the winningest coaches in NFL history. Belichick has been able

to pursue the proper strategies on the field without worrying about career risk because his success has

provided him with job security. He was more conventional when he was the head coach of the mediocre

Cleveland Browns, where he won just 45 percent of his games.

25

2. Status quo bias. Classic economic theory suggests that decision makers identify their possible options

and select the one with the highest value. However, research shows that people have a bias in favor of

the status quo, continuing to do what they are doing, even when better alternatives exist.

26

This is as true

for organizations as it is for individuals.

A related point is decision makers often favor inaction to action. This is called omission bias. In

experiments, subjects preferred doing nothing over doing something even when doing nothing was

associated with change.

This bias toward inaction relates to loss aversion. Change can lead to gains or

losses and decision makers prefer to do nothing because the potential losses loom larger than the gains.

Decision makers and onlookers tend to treat the outcomes of inaction as neutral and regard the outcomes

of action as positive if they are perceived to be better than inaction and negative if they are worse than

the counterfactual associated with doing nothing.

27

One of the psychological challenges with innovation, especially in sports, is that prior teams that have

been successful have not used the new techniques. Morey points out that coaching is like a guild, with

perceived wisdom passed from one generation to the next. This also shapes player training. Trying new

approaches, even if supported analytically, goes against past success, conventional wisdom, and what

the players have been taught to do.

28

The endowment effect describes the tendency to value what you have higher than something equivalent

that you do not have. This is a problem if a team is trying to get the most value from players based on the

Recent Success

Experimentation

© 2023 Morgan Stanley. All rights reserved.

5980321 Exp. 09/30/2024

9

team’s payroll. One analysis of the NFL showed that teams overvalued players on the roster when they

extended their contracts or resigned them relative to when they acquired free agents (albeit both had

negative expected value).

29

In economics, a sunk cost is one that has been incurred and is unrecoverable. Proper decision making

ignores sunk costs and focuses on the future. But teams struggle to do that. For example, NBA teams

tend to play their high-round draft picks more than they should and keep them on the roster longer than

their results warrant.

30

The best teams keep a steady eye on the price and value of their portfolio of players.

Of course, the challenge is that price is largely set and value is probabilistic.

3. Sample size. One of the biggest impediments to change is that many tactics that are supported by

analytics don’t work all the time. The key idea is that when drawing a sample from a population of

outcomes, there is large variation in small sample sizes and small variation in large sample sizes.

31

As a

result, even when something is correct to do on average, small sample sizes can have outcomes far from

average, sowing doubt for believers and nonbelievers alike.

Exhibit 2, which shows that 3-point shots have a higher expected value than 2-point shots, is based on

the success rate of roughly 1.4 million 3-point attempts and 6.5 million 2-point tries. The results can vary

a lot from the averages over any stretch of a game, for a complete game, or even for a series. For instance,

Steph Curry, one of the greatest shooters in the history of the NBA, made 13 of his 17 3-point attempts in

a game in 2016 and 0 of his 11 attempts in a game a year later. Combine those games and you get close

to his career 3-point shooting percentage of 43.3 percent.

Regression toward the mean is a statistical concept that says that outcomes far from the average are

followed by outcomes with an expected value closer to the average. It is a very tricky concept that has

confused even prominent academics.

32

Teams can make poor decisions when they see outliers and fail

to consider a sufficient sample of outcomes.

One example is firing a coach. Typically, teams fire their coach after a poor stretch of performance.

Sometimes those sackings are the result of poor coaching and other times they reflect bad luck.

33

Regression toward the mean tells us that in cases where the firing is because of poor luck, the team will

do better after the change independent of the coaching decision. An analysis of the four major sports in

the U.S. shows that teams improve after a coaching change.

34

One of the most important lessons for decision making is that when both skill and luck contribute to the

outcome, you should assess the quality of the decision based on the process by which it was made rather

than on the outcome. This may seem counterintuitive, especially in the world of professional sports where

winning is the unambiguous objective.

But a focus on process is essential for at least two reasons. The first is practical: over the long run, a good

process leads to good outcomes. The key insight is that sometimes an organization can make the correct

strategic or tactical decision but have an outcome that is unsatisfactory as the result of bad luck. This

happens in a world of uncertainty, where the desired outcome occurs only some percentage of the time.

In these cases, the organization must have the fortitude to stick with the decision-making framework.

Avoiding outcome bias is the second reason that process is so important. Outcome bias occurs when we

assess the quality of the decision based on the outcome rather than the process. It is problematic because

good decisions can lead to bad outcomes and bad decisions can lead to good outcomes. When you focus

© 2023 Morgan Stanley. All rights reserved.

5980321 Exp. 09/30/2024

10

exclusively on outcomes in a world where luck and skill operate, you fail the framework and risk losing the

discipline that a robust decision-making process offers.

Outcome bias brings us back to sample size. A good process and a bad outcome are painful for any

individual event. But it is important to remember that the decision provided the best expected outcome. If

you have done everything you can to make a good decision, it is best to adopt an attitude of equanimity

about the short-term outcome.

A discussion of sample size naturally leads to the issue of time horizon.

The Importance of Time Horizon

Elliott Jaques was an academic and consultant who studied managerial organization.

35

One of his observations

is that there are different time spans for members of an organization. He called the goal and timing of completing

a task “what by when,” and he observed that some employees operate on a short time scale and others on a

long one. Incentives can become misaligned when time spans conflict.

One rough way to think about time span is tenure with an organization. Exhibit 7 shows the average and median

number of seasons with a team for players, coaches, general managers, and owners in the NBA from the

1976/77 through the 2019/20 season. Players are with a team for just under 2 seasons on average, coaches

2.5, general managers nearly 5, and owners for about 11. The results are similar for other sports.

36

Recognizing

that all participants have an imperative to win, you would expect that players and coaches have a shorter time

horizon than general managers and owners.

Exhibit 7: Average Number of Seasons with an NBA Team

Players

Coaches

General Managers

Owners

Average

1.9

2.5

4.9

10.9

Median

1.4

2.0

3.5

7.5

Source: FiveThirtyEight; RealGM.

Note: Includes non-active players, coaches, GMs, and owners, 1976-77 to 2019-2020.

The experience of the New York Jets, an NFL franchise, during the 2020 season is an example of potential

incentive misalignment based on time span. In the NFL, as with other leagues, the teams with the worst records

are eligible to make among the earliest selections in the following year’s amateur draft. Further, Trevor

Lawrence, a coveted quarterback at Clemson University, was projected to be the first pick in the 2021 draft.

Analysis shows that the quarterback is the most important member of an NFL franchise, followed by the head

coach, general manager, and owner.

37

The Jets had lost the first 13 of their 16 scheduled games and losing their final 3 would have given them the top

pick, allowing them to select Lawrence. From the point of view of the organization it would make sense to go

winless and draft a player with the potential to put the franchise in a position to win for a long time. On the other

hand, players and coaches are taught to compete and win each week, and the stigma of a winless season is

strong. The Jets won 2 of their last 3 games and hence did not get the top draft pick. This is a case where

conflicting time spans is clear.

Players are the main determinant of success in any sport. The distribution of player longevity in professional

leagues is heavily skewed. Most players have very short careers and a handful have long careers, which makes

© 2023 Morgan Stanley. All rights reserved.

5980321 Exp. 09/30/2024

11

measures such as average or median tenure misleading. For example, 3 percent of NBA players have a career

length of less than 12 total minutes of playing time.

38

It stands to reason that the vast majority of players focus

on the here and now.

Coaches have more longevity than players. Coaches matter to success, albeit their impact varies a great deal

by sport.

39

They implement an organization’s framework for winning, make in-game decisions, and manage

player personalities. The nature of the game has a large effect on how important coaches are. In the NBA, for

instance, player talent tends to be more important than the style of play over time. At one point, the Houston

Rockets evaluated the effectiveness of their set of offensive plays and found that “R,” which stood for random,

was one of the best.

40

In some sports, most prominently baseball and basketball, responsibility for the organizational framework has

shifted over time from the coach to the front office, which is informed by analytics. This means that coaches

have less discretion to stray from what is shown to contribute to wins. Examples include the rise in 3-point

shooting in the NBA and the placement of defensive players on the baseball field in order to limit the offensive

potential of an opponent.

In other sports, including American football and hockey, the coaches continue to be the prime decision makers

and the analytics are less prominent. NFL coaches are important in part because they tell every player where to

start on every play. In particular, the link between the head coach and starting quarterback is significant. But

change is likely in these sports as better data, including the tracking of player movement, become available. For

instance, the National Hockey League (NHL) did not implement “Puck and Player Tracking” technology until

2020.

The job of a general manager is to assemble a team that can compete for a championship. The job is challenging

for a number of reasons. Athletes tend to follow an aging curve, with the performance improving until a peak

age and then declining after that.

41

Further, younger players who have yet to demonstrate their worth tend to

make less money than older ones who are more established. Ideally, the GM builds a roster of young, relatively

inexpensive, and improving players.

This can be a painful process because the likely performance of veterans is easier to project than untested

rookies. Fans also know and love the successful veterans. Long-term success requires the ability to project

player performance, which is a classic exercise in decision making under uncertainty.

One way to rebuild a franchise is to get rid of expensive, aging veterans and bring in cheap, young players. This

commonly leads to temporarily poor results that in turn provide higher picks in the amateur draft. Teams seeking

to rebuild must often trade poor results in the short term in order to build a winning franchise in the long term.

This is where time horizon conflicts can be acute. Owners, players, coaches, and fans naturally want a team

that wins now. Building a team is a process that takes time, and performance almost always has to deteriorate

before it can improve. Some teams attempt to buy some time with their fans by signaling that they intend to

rebuild.

42

In other cases, the ownership struggles to survive the process.

43

Time horizon is also a function of where a franchise is in its life cycle. For example, a team that is in a position

to compete for a championship may add relatively expensive and short-term players to close any skill gaps.

Success as a GM requires smarts and alignment. Smarts captures the ability to assimilate a lot of information

and to make proper decisions within the framework to provide the best chance of long-term success. Indeed,

© 2023 Morgan Stanley. All rights reserved.

5980321 Exp. 09/30/2024

12

more educated GMs tend to be more successful than less educated ones.

44

Investing in players is similar to

investing in companies in that the range of potential outcomes can be wide.

Alignment indicates that the whole organization buys into a philosophy and framework. Research shows that

match quality, which measures fit between abilities and the nature of the work, is crucial.

45

One important

dimension of alignment is the decision-making process. To tie this to the literature on diversity, the goal is to

have high cognitive diversity, which reflects lots of different points of view, and low values diversity, which

indicates a unity of purpose.

46

Audits of decisions should focus on how they were made rather than solely on

how they turned out.

Owners should have the longest time horizon in theory. But many are not impervious to impetuous decision

making. Individuals who have earned enough money to buy a sports franchise have been very successful in one

domain and understandably have the sense that their decision-making skills will carry over to another domain.

Further, owners are very visible in the community and therefore feel pressure from the media and fans.

Organizational alignment starts at the top. Great owners bring in talented front office employees who develop

and execute a framework to win. This can take time and patience and does not come without ups and downs.

Those with experience in investing, and hence skill in decision making under uncertainty, have become more

prominent in team ownership.

What Sports Teams Can Do to Learn Faster (and Change)

The recommendations for becoming a better learning organization are the opposite of the impediments to

change. Here are some ideas:

• Align behind what wins. This has analytical and organizational components. Professional sports leagues

are highly competitive, so it is essential to analyze ways to gain an advantage that are within the control

of management, coaches, and players. The lag in adopting practices that contribute to winning prompted

this discussion. Proper alignment includes a commitment to lead, rather than lag, in initiatives that

contribute to wins.

• Explain the why. Effective communicators, which include front office executives, coaches, and teachers

of any kind, go beyond saying what to do and explain why something works. This is especially important

when strategies or tactics are inconsistent with the conventional wisdom. An additional hurdle is that some

practices require sufficient sample sizes to prove their worth. One method to communicate the value of a

strategy is to use visualization to show larger sample sizes. Shot charts such as the one in exhibit 4 and

spray charts that show a hitter’s pattern when putting a ball into play illustrate this concept.

• Refine talent assessment. This concept has two elements. First is to identify the handful of skills a player

must master to be an effective member of the team. Bill Walsh, a head coach for the champion San

Francisco 49ers and a member of the NFL Hall of Fame, suggested this was a source of advantage. He

said, “We have five or six skills or techniques that we want each of our players to be able to use in carrying

out his assignment, where our opponents usually will have only one or two.” Second is the degree to which

those skills can be taught and developed. Walsh continued, “Being prepared starts with identifying the

essential skills our team needs to compete effectively. The next step is to create a format to teach those

skills.”

47

These two steps of assessment are valuable for identifying new players and evaluating those

currently on the team.

© 2023 Morgan Stanley. All rights reserved.

5980321 Exp. 09/30/2024

13

• Focus on process and feedback. It is important to emphasize the method used to make decisions in

fields where a wide range of outcomes can occur. The quality of the outcomes is sometimes separate

from the quality of the decisions as the result of skill, luck, and error. But over the long term, good decisions

lead to good outcomes and a good decision-making process will beat a bad one.

Part of the auditing process is keeping track of how the organization made decisions and gathering

feedback. Teams in all sports create a list of players they would like to draft in order from most to least

attractive. Drafting is the most cost-effective way to build a team but is inherently tricky because it entails

projecting the performance of a young athlete. Further, much has been made of the tension between

traditional scouts, who rely more on the eye and gut feelings, and analytics types, who crunch the

numbers. Comparing past projections with actual outcomes provides essential feedback that can help

improve the process.

48

• Take advantage of differing time horizons. Building a team is similar to building an investment portfolio.

Portfolio managers try to buy businesses for less than they are worth. Likewise, GMs try to acquire players

who will perform well for the salary they are paid. Teams that are keen to perform well in the short term

sometimes overpay for projected performance. This happens most often at the two extremes of the player

life cycle: during the draft and with seasoned veterans.

The draft is the best way to create surplus value, defined as the value of a player’s performance minus

their compensation. Higher draft picks are on average better players than lower draft picks, but they also

get paid more. In the early 1990s, Mike McCoy, a partial owner and executive at the Dallas Cowboys,

developed a chart to estimate trade values for draft picks. For example, the number 1 pick has a value of

3,000, the 7

th

pick 1,500, and the 40

th

pick 500. Despite its lack of empirical grounding, the chart has been

widely used in the league and it explains actual trades well.

49

Richard Thaler and Cade Massey, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania who studies judgment

under uncertainty, analyzed the NFL draft using surplus value. They found that the chart is inaccurate and

that the surplus value of the first pick in the second round (33

rd

pick overall) is higher than the first pick. In

fact, average surplus value in the second round exceeds that in the first round because the performance

value declines at a rate slower than compensation.

They also calculated the probability that a player is better than the next player drafted at the same position.

For example, what are the odds that a wide receiver selected with the 6

th

pick is better than the wide

receiver chosen with the 10

th

pick? The answer is 52 percent, essentially a coin toss. In other words, it is

really hard to identify talent. Add rules of thumb about the perceived value of draft picks across time, such

as a third-round pick this year is equivalent to a second-round pick next year, and it’s easy to see how

teams can add value by focusing more intently on surplus value.

The Cleveland Browns are a recent example of a team that focused on the draft to build value. They were

able to create substantial draft capital through trades of picks and players, prudent management, and

some seasons with poor winning percentages. A value for each of their draft picks can be estimated using

the Draft Value Chart developed by Chase Stuart, an analyst who owns the website Football Perspective.

Stuart’s chart is more accurate than McCoy’s.

The Browns accrued 13.25 percent of the total draft capital from 2017–2018. To put that in context, the

average annual draft capital per team is 3.125 percent (100 percent ÷ 32 teams), which means the average

© 2023 Morgan Stanley. All rights reserved.

5980321 Exp. 09/30/2024

14

draft capital for 2 seasons is 6.25 percent (2 ✕ 3.125). The additional 7.0 percentage points of draft capital

(13.25 – 6.25) the Browns accumulated was equivalent to more than two extra drafts (7.0 ÷ 3.125 = 2.2).

The Jacksonville Jaguars and the Miami Dolphins appear to have followed this approach in recent years.

Each team has accumulated the equivalent of 1.6 extra drafts over the past two years (see exhibit 8).

Exhibit 8: Total Excess Draft Capital Accrued by Three NFL Teams in Recent Years

Source: Sports Reference LLC, “NFL and AFL Draft History,” Pro-Football-Reference.com-Pro Football Statistics and

History, www.pro-football-reference.com, August 2021.

Overpaying for projected performance also happens with established veterans. One intuitive means to

boost organizational performance is to add a superstar. This is a hard way to add value in any

organization.

50

In sports it is difficult because veterans are often on the downside of their performance

curves and command a high salary. Short-term deals can make sense, but long-term contracts commonly

have negative surplus value for the team.

Albert Pujols is a baseball player who played for the St. Louis Cardinals during his peak years and will

almost certainly be elected to the Hall of Fame. Following the 2011 season, he was 31 years old and

signed a 10-year, $240 million deal with the Los Angeles Angels. Exhibit 9 shows that the value he

contributed was about $40 million during that time, creating a roughly $200 million deficit in surplus value.

While Pujols may have added to the Angels in other ways, it is clear that his price exceeded his value.

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Cleveland Browns,

2017–2018

Jacksonville Jaguars,

2020–21

Miami Dolphins,

2020–21

Total Excess Draft Capital (Percent)

Average Draft Capital Per Year

© 2023 Morgan Stanley. All rights reserved.

5980321 Exp. 09/30/2024

15

Exhibit 9: Value minus Salary for Albert Pujols, 2011–2021

Source: FanGraphs.com.

• Don’t read the newspaper. This is a generic admonishment against paying too much attention to the

media and fans, groups that tend to amplify outcomes relative to a decision-making framework. In domains

with uncertainty, good decisions precede poor results an uncomfortable percentage of the time. Poor

decisions might also pay off. Focus on what you can control, make decisions that give the team the best

chance to win, and attempt to handle triumphs and setbacks with equanimity. As John Wooden, the

legendary coach of UCLA basketball, said, “All of life is peaks and valleys. Don’t let the peaks get too high

and the valleys too low.”

51

-45

-40

-35

-30

-25

-20

-15

-10

-5

0

5

10

15

20

2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021

Value Minus Salary ($Million)

Contract with Angels

Value: $38 million

Salary: $240 million

Final season

with Cardinals

© 2023 Morgan Stanley. All rights reserved.

5980321 Exp. 09/30/2024

16

What Investment Management Organizations Can Do to Learn Faster

This report focused on what contributes to wins in sports and the barriers to change that make teams slow to

adopt those strategies. But the concepts apply to all organizations where the results of decisions occur with

some probability. Here are some observations about what investment management organizations can do to

learn and adapt:

• Think about sources of edge in the investment process. Investment management is a very competitive

field, so it is useful to start by identifying potential inefficiencies and developing a process to take

advantage of them. Inefficiencies can be assigned to broad categories, but there are often costs

associated with capturing the opportunities they present.

52

Note that strategies can have different

cadences. Renaissance Technologies, which seeks small gains on frequent trades, and Berkshire

Hathaway, which looks for large profits on a relatively small number of investments, have been successful

over time.

Identifying edge is crucial both because it provides a basis for active management, and the sources of

edge can change over time. Similar to sports teams, sources of edge explain why a process is likely to

work in the long term.

• Organizational alignment. This has a couple of elements. The first is to align the activities within the

organization to the perceived source of edge. The goal is to make all activities within the firm congruent

with the espoused method to succeed.

53

Part of this initiative is to put into place methods to allow the

investment team to remain focused on the process.

The second is the client base. There is a lot of short-term noise in investment results, which means that

even skillful managers have realized extended periods of underperformance relative to a benchmark.

Having clients who understand the process and are willing to ride out the inevitable drawdowns is crucial

to executing on a strategy. Research suggests that hiring managers based solely on recent past

performance can be a challenge.

54

• Take a long-term view. Systematic and discretionary strategies have earned similar returns over time.

55

But both approaches, no matter the turnover of the securities in the portfolio, require a long-term

orientation. The reason is that the ratio of signal to noise is very low in the short run and reveals itself only

over the long run.

56

Even a differentiated and effective strategy requires patience.

There is research that supports this point. For example, active share, a measure of how different a portfolio

is relative to its benchmark, has been increasing since the financial crisis (see exhibit 10). Funds that

combine high active share and low turnover deliver excess returns on average.

57

Further, the holdings of

funds that trade frequently tend to generate excess returns in the short run, but the holdings of funds with

low turnover add value only over longer time horizons.

58

© 2023 Morgan Stanley. All rights reserved.

5980321 Exp. 09/30/2024

17

Exhibit 10: Breakdown of Active Share for Mutual Funds, 1990–2015

Source: Antti Petajisto, see www.petajisto.net/data.html; Martijn Cremers, “Active Share and the Three Pillars of Active

Management: Skill, Conviction and Opportunity,” Financial Analysts Journal, Vol. 73, No. 2, Second Quarter 2017, 61-79;

Counterpoint Global.

Most of us learn to associate effort with results. In investing, effort is better described as thinking than as

acting. This is true for individuals and institutions. Similar to many other activities in life, investing can be

described as “hours of boredom punctuated by moments of terror.” Limited activity for long-term investors

tends to be the best course. At times, the market presents opportunities for action. But on balance, doing

less can leave an investor with more.

• Spend a lot of time on people. Professional sports and investment management are similar in that both

include a group of people coming together to perform at a high level in a very competitive domain. Sports

teams attempt to construct a roster with the requisite skills for success in the face of constraints.

Investment management organizations do much the same. Success generally requires congruence

between process and people. Therefore, an understanding of the skills necessary to compete effectively

is crucial. Developing a thoughtful inventory of skills allows for effective hiring and performance evaluation.

• Strive to learn constantly. In sports, the boundaries and rules are generally stable. The objective is to

maximize performance given the constraints of the system. In investing, the landscape continuously

changes. This includes the evolution of businesses, the nature of investment management, and the profile

of investors. As a result, successful investors have little choice but to learn. This means being willing to

ask naïve questions and to be mindful of the pitfalls of status quo bias. In investment management, reading

is probably the best way to acquire knowledge. As Charlie Munger, vice chairman of Berkshire Hathaway,

has said, “I don’t think you can get to be a really good investor over a broad range without doing a massive

amount of reading.”

59

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

1990

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

Percentage of Assets

60-70%

70-80%

80-90%

90-100%

<60%

Active Share Range

© 2023 Morgan Stanley. All rights reserved.

5980321 Exp. 09/30/2024

18

Conclusion

Successful organizations seek to learn and adapt over time in order to enable quality decisions. Good long-term

results require developing strategies and tactics that add value and having an ability to execute them. An

effective decision-making framework combines both elements.

One of the main lessons from this discussion is that organizations can be slow to adopt certain approaches even

when analysis reveals that they add value. Reasons for this include the fact that losses often feel worse than

comparable gains and the inclination to maintain the status quo. But perhaps the biggest factor is that in any

field where a good decision leads to a good outcome only some percentage of the time, those who make the

right decisions may suffer poor outcomes in the short run and hence look wrong.

This limited link between decisions and outcomes plants doubt in two ways. The first is the decision maker must

question whether his or her process does add value. The second is that naysayers can point at short-term failure

as evidence of the futility of the strategy. Overcoming these hurdles is psychologically challenging. The best way

to do so is to have organizational alignment behind a commitment to improvement, learning, transparency, and

accountability.

We offer special thanks to our summer intern, Kevin Villafranca, who is a student at Georgetown University.

Kevin made a substantial contribution to this piece, in particular with gathering and analyzing data for the NBA.

We appreciate your contribution, Kevin.

Please see Important Disclosures on pages 22-24

© 2023 Morgan Stanley. All rights reserved.

5980321 Exp. 09/30/2024

19

Endnotes:

1

For a good discussion of the motives of professional sports leaders, see George Foster, Norm O’Reilly, and

Antonio Dávila, Sports Business Management: Decision Making Around the Globe, Second Edition (New York:

Routledge, 2021), 159-162.

2

Charles D. Ellis, “Will Business Success Spoil the Investment Management Profession?” Journal of Portfolio

Management, Vol. 27, No. 3, Spring 2001, 11-15.

3

Samuel Gorovitz and Alasdair MacIntyre, “Toward a Theory of Medical Fallibility,” Journal of Medicine and

Philosophy: A Forum for Bioethics and Philosophy of Medicine, Vol. 1, No.1, January 1976, 51-71.

4

Benjamin A. Rodwin, Victor P. Bilan, Naseema B. Merchant, Catherine G. Steffens, Alyssa A. Grimshaw, Lori

A. Bastian, and Craig G. Gunderson, “Rate of Preventable Mortality in Hospitalized Patients: A Systematic

Review and Meta-analysis,” Journal of General Internal Medicine, Vol. 35, No. 7, July 2020, 2099-2106.

5

Atul Gawande, The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2009).

6

For example, investment firms have investors and the business side. Money managers also have a system of

strategies and tactics that seeks to generate excess returns. Talent is very important. Firms can hire investors

out of school (draft) or hire them from other firms (free agency). Successful firms have congruence between

their investment process, people, and objectives.

7

George Foster, Norm O’Reilly, and Zachary Naidu, “Playing-Side Analytics in Team Sports: Multiple Directions,

Opportunities, and Challenges,” Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, No. 3, July 2021.

8

Kathryn Johnston and Joseph Baker, “Waste Reduction Strategies: Factors Affecting Talent Wastage and the

Efficacy of Talent Selection in Sport,” Frontiers in Psychology, Vol. 10, January 2020.

9

This distinction is commonly referred to as strong link and weak link sports. See Chris Anderson and David

Sally, The Numbers Game: Why Everything You Know About Soccer Is Wrong (New York: Penguin Books,

2013), 197-222. They identify soccer as a weak link game. This framework is based on Michael Kremer, “The

O-Ring Theory of Economic Development,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 108, No. 3, August 1993, 551-

575.

10

Jeremy Cluff, “NFL's Highest Paid Players in 2021: Quarterbacks Dominate Ranking of NFL Players by

Salary,” Arizona Republic, March 29, 2021.

11

Ben Lindbergh and Travis Sawchik, The MVP Machine: How Baseball’s New Nonconformists Are Using Data

to Build Better Players (New York: Basic Books, 2019), 178.

12

Richard Thaler, “The Sports Learning Curve: Why Teams are Slow to Learn and Adapt,” Presentation at the

MIT Sloan Sports Analytics Conference, March 6, 2020. See www.sloansportsconference.com/event/the-sports-

learning-curve-why-teams-are-slow-to-learn-and-adapt; Mike Band, "Introducing the Next Gen Stats Decision

Guide: A new analytics tool for fourth down, two-point conversions,” Next Gen Stats, September 7, 2021. See

www.nfl.com/news/introducing-the-next-gen-stats-decision-guide-a-new-analytics-tool-for-fourth-do.

13

Mike Ozanian “World’s Most Valuable Sports Teams 2021,” Forbes, May 7, 2021. See www.forbes.com/sites/

mikeozanian/2021/05/07/worlds-most-valuable-sports-teams-2021/?sh=1bc23f6c3e9e and Mike Ozanian, “The

NFL’s Most Valuable Teams 2021: Average Team Value Soars To $3.5 Billion As League Shrugs Off Pandemic

Year,” Forbes, August 5, 2021.

See www.forbes.com/sites/mikeozanian/2021/08/05/the-nfls-most-valuable-teams-2021-average-team-value-

soars-to-35-billion-as-league-shrugs-off-pandemic-year/?sh=4068c612654e.

14

Donald L. Alexander and William Kern, “The Economic Determinants of Professional Sports Franchise

Values,” Journal of Sports Economics, Vol. 5, No. 1, February 2004, 51-66.

15

The 3-point shot was introduced the same year as Larry Bird and Earvin “Magic” Johnson started in the NBA.

Per www.basketball-reference.com, Bird averaged 1.9, and Johnson 1.2, 3-point attempts per game during their

careers. Steph Curry, one of the league’s best players today, has averaged nearly 11 three-point attempts per

game over the last five seasons.

16

Shaun Powell, “Doubt, disdain marked most NBA teams' first forays into 3-point land,” NBA.com, February 21,

2017.

17

Kirk Goldsberry, Sprawlball: A Visual Tour of the New Era in the NBA (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt,

2019).

© 2023 Morgan Stanley. All rights reserved.

5980321 Exp. 09/30/2024

20

18

Joshua Schwartzstein and Deepak Malhorta, “Rocket Science,” Harvard Business School Case Study N2-

921-043, January 20, 2021.

19

Zach Lowe, “Why are Teams Bored with Boards?” ESPN.com, January 5, 2016.

20

For example, see Eric Nehm, “Bucks’ Aggressive New Approach to Crashing the Offensive Glass is Paying

Off,” The Athletic, January 21, 2021; Todd Whitehead, “More Lessons from NBA Rebound Tracking,” Nylon

Calculus: FanSided, January 28, 2020; and Michael Lynch, “Crash the Glass: Making a Case for Offensive

Rebounding,” FastModel Sports, April 18, 2019.

21

For instance, Mark Broadie, a professor of finance at Columbia Business School and a leader in golf analytics,

notes that professional players are going for the green more often in 2 shots on par-5 holes, a strategy that the

analysis of the data supports. Twenty years ago, pundits expected players to lay up to their favorite distance

and criticized the players who seemed to be too aggressive. Nearly all players now go for the green in two shots,

except for when individual circumstances warrant a different approach.

22

Pat McManamon, “Paul DePodesta: Criticism of Browns’ New Ways ‘Part of the Fun,’” ESPN.com, March 16,

2016.

23

John Maynard Keynes, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money (New York: Harcourt, Brace

and Company, 1936), 138.

24

Michael J. Mauboussin, The Success Equation: Untangling Skill and Luck in Business, Sports, and Investing

(Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review Press, 2012), 178-185.

25

Tobias J. Moskowitz and L. Jon Wertheim, Scorecasting: The Hidden Influences Behind How Sports Are

Played and Games Are Won (New York: Crown Archetype, 2011), 47-51. Michael Lombardi, a media analyst

and former American football executive, recently discussed the pressure NFL head coaches feel: “They know

they have two or three years to succeed at the job, so everything is based on situational values, not sustainable

values. So they make every decision based on situations, not on how I can sustain something. Cause the owners

are so willing to make changes so rapidly.” See “Episode 012: The Other Side of the Ball with Michael Lombardi,”

The Decision Education Podcast, August 25, 2021.

26

William Samuelson and Richard Zeckhauser, “Status Quo Bias in Decision Making,” Journal of Risk and

Uncertainty, Vol. 1, No. 1, March 1988, 7-59.

27

Ilana Ritov and Jonathan Baron, “Status-Quo and Omission Biases,” Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, Vol. 5,

No. 1, September 1992, 49-61.

28

Schwartzstein and Malhorta, “Rocket Science.”

29

Steven Ruiz, “Proof That Signing NFL Free Agents is More Cost-Effective than Keeping Homegrown Players,”

USA Today, March 15, 2019.

30

Barry M. Staw and Ha Hoang, “Sunk Costs in the NBA: Why Draft Order Affects Playing Time and Survival in

Professional Basketball,” Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 40, No. 3, September 1995, 474-494.

31

Howard Wainer, “The Most Dangerous Equation,” American Scientist, May-June 2007, 249-256.

32

Stephen M. Stigler, “Regression Towards the Mean, Historically Considered,” Statistical Methods in Medical

Research, Vol. 6, No. 2, April 1997, 103-114.

33

Raphael Flepp and Egon Franck, The Performance Effects of Wise and Unwise Managerial Dismissal,”

Economic Inquiry, Vol. 59, No. 1, January 2021, 186-198. For a discussion on threshold effects and firing

decisions, see Lars J. Lefgren, Brennan Platt, Joseph Price, Samuel Higbee, “Outcome Based Accountability:

Theory and Evidence,” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, Vol. 160, April 2019, 121-137.

34

Jon Bois, “Should You Fire Your Coach Midseason? A Statistical Breakdown,” SB Nation, April 10, 2012.

35

Elliott Jaques, Requisite Organization: A Total System for Effective Managerial Organization and Managerial

Leadership for the 21

st

Century (Fleming Island, FL: Cason Hall & Co, 2006).

36

Foster, O’Reilly, and Dávila, Sports Business Management, 175-176.

37

Boris Groysberg, Evan M.S. Hecht, and Abhijit Naik, “Who’s the Most Important Member of an NFL

Franchise?” Harvard Business Review, April 25, 2019.

38

Alexander M. Petersen, Woo-Sung Jung, Jae-Suk Yang, and H. Eugene Stanley, “Quantitative and Empirical

Demonstration of the Matthew Effect in a Study of Career Longevity,” PNAS, Vol. 108, No. 1, January 4, 2011,

18-23.

39

Christopher R. Berry and Anthony Fowler, “How Much Do Coaches Matter?” MIT Sloan Sports Analytics

Conference No. 12549, March 2019.

© 2023 Morgan Stanley. All rights reserved.

5980321 Exp. 09/30/2024

21

40

Schwartzstein and Malhorta, “Rocket Science.”

41

There is a large literature on this topic. For example, see Nemanja Vaci, Dijana Cocić, Bartosz Gula, and

Merim Bilalić, “Large Data and Bayesian Modeling—Aging Curves of NBA players,” Behavior Research

Methods, Vol. 51, No. 4, August 2019, 1544-1564.

42

Examples include the Chicago Blackhawks (October 2020) and the New York Rangers (February 2018) in the

NHL.

43

See www.espn.com/pdf/2016/0406/nba_hinkie_redact.pdf.

44

Matthew Juravich, Steven Salaga, and Kathy Babiak, “Upper Echelons in Professional Sport: The Impact of

NBA General Managers on Team Performance,” Journal of Sport Management, Vol. 31, No. 5, September 2017,

466-479.

45

Thomas L. P. R. Peeters, Steven Salaga, and Matthew Juravich, “Matching and Winning? The Impact of Upper

and Middle Managers on Firm Performance in Major League Baseball,” Management Science, Vol. 66, No, 6,

June 2020, 2735-2751.

46

Karen A. Jehn, Gregory B. Northcraft, and Margaret A. Neale, “Why Differences Make a Difference: A Field

Study of Diversity, Conflict, and Performance in Workgroups,” Administrative Quarterly, Vol. 44, No 4, December

1999, 741-763.

47

Richard Rapaport, “To Build a Winning Team: An Interview with Head Coach Bill Walsh,” Harvard Business

Review, Vol. 71, No. 1, January-February 1993, 111-120.

48

Brayden Gerrard, “Measuring Success in The NBA Draft: Find the Best (and Worst) Drafting Teams Over the

Last Ten Years, towardsdatascience.com, July 23, 2020.

49

Cade Massey and Richard H. Thaler, “The Loser’s Curse: Decision Making and Market Efficiency in the

National Football League Draft,” Management Science, Vol. 59, No. 7, July 2013, 1479-1495. Of the chart, Cade

Massey and Zach Drapkin write: “It is the default option and a coordination device. It turns out a coordination

device is vital, given that there are 32 teams, ambiguously valued assets, time pressure, public deals, and

professional reputations. These factors create the perfect recipe for adherence to a norm, any norm. As McCoy

said in 2006, ‘A standard list price protects you. Nobody gets skinned.’” See Cade Massey and Zach Drapkin,

“The Fortune Teller’s Trade Chart,” pff.com, April 28, 2021.

50

Boris Groysberg, Chasing Stars: The Myth of Talent and the Portability of Performance (Princeton, NJ:

Princeton University Press, 2010).

51

Beth Harris, “Sports Legends Scully, Wooden Share Stage at Charity Event,” Associated Press, June 15,

2008.

52

Michael J. Mauboussin, “Who Is on the Other Side?” BlueMountain Investment Research, February 12, 2019,

53

Michael J. Mauboussin, Dan Callahan, and Darius Majd, “Form Follows Function: Organizational Structure

and Investment Results,” Credit Suisse Global Financial Strategies, July 8, 2016.

54

Bradford Cornell, Jason Hsu, and David Nanigian, “Does Past Performance Matter

in Investment Manager Selection?” Journal of Portfolio Management, Vol. 43, No. 4, Summer 2017, 33-43.

55

Campbell R. Harvey, Sandy Rattray, Andrew Sinclair, and Otto Van Hemert, “Man vs. Machine: Comparing

Discretionary and Systematic Hedge Fund Performance,” Journal of Portfolio Management, Vol. 43, No. 4,

Summer 2017, 55-69.

56

Andrei Shleifer and Robert W. Vishny, “The Limits of Arbitrage,” Journal of Finance, Vol. 52, No. 1, March

1997, 35-55.

57

Martijn Cremers and Ankur Pareek, “Patient Capital Outperformance: The Investment Skill of High Active

Share Managers Who Trade Infrequently,” Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 122, No. 2, November 2016,

288-306.

58

Jules van Binsbergen, Jungsuk Han, Hongxun Ruan, and Ran Xing, “A Horizon-Based Decomposition of

Mutual Fund Value Added Using Transactions,” SSRN Working Paper, March 3, 2021.

59

Janet Lowe, Damn Right: Behind the Scenes with Berkshire Hathaway Billionaire Charlie Munger (New York:

John Wiley & Sons, 2000), 231.

© 2023 Morgan Stanley. All rights reserved.

5980321 Exp. 09/30/2024

22

IMPORTANT INFORMATION

The views and opinions and/or analysis expressed are those of the author as of the date of preparation of this

material and are subject to change at any time due to market or economic conditions and may not necessarily

come to pass. Furthermore, the views will not be updated or otherwise revised to reflect information that

subsequently becomes available or circumstances existing, or changes occurring, after the date of publication.

The views expressed do not reflect the opinions of all investment personnel at Morgan Stanley Investment

Management (MSIM) and its subsidiaries and affiliates (collectively “the Firm”), and may not be reflected in all

the strategies and products that the Firm offers.

Forecasts and/or estimates provided herein are subject to change and may not actually come to pass.

Information regarding expected market returns and market outlooks is based on the research, analysis and

opinions of the authors or the investment team. These conclusions are speculative in nature, may not come to

pass and are not intended to predict the future performance of any specific strategy or product the Firm offers.

Future results may differ significantly depending on factors such as changes in securities or financial markets or

general economic conditions.

Past performance is no guarantee of future results. This material has been prepared on the basis of publicly

available information, internally developed data and other third-party sources believed to be reliable. However,

no assurances are provided regarding the reliability of such information and the Firm has not sought to

independently verify information taken from public and third-party sources. The views expressed in the books

and articles referenced in this whitepaper are not necessarily endorsed by the Firm.

This material is a general communications which is not impartial and has been prepared solely for information

and educational purposes and does not constitute an offer or a recommendation to buy or sell any particular

security or to adopt any specific investment strategy. The material contained herein has not been based on a

consideration of any individual client circumstances and is not investment advice, nor should it be construed in

any way as tax, accounting, legal or regulatory advice. To that end, investors should seek independent legal

and financial advice, including advice as to tax consequences, before making any investment decision.

Charts and graphs provided herein are for illustrative purposes only. Any securities referenced herein are solely

for illustrative purposes only and should not be construed as a recommendation for investment.

This material is not a product of Morgan Stanley’s Research Department and should not be regarded as a

research material or a recommendation.

The Firm has not authorised financial intermediaries to use and to distribute this material, unless such use and

distribution is made in accordance with applicable law and regulation. Additionally, financial intermediaries are

required to satisfy themselves that the information in this material is appropriate for any person to whom they

provide this material in view of that person’s circumstances and purpose. The Firm shall not be liable for, and

accepts no liability for, the use or misuse of this material by any such financial intermediary.

The whole or any part of this work may not be directly or indirectly reproduced, copied, modified, used to create

a derivative work, performed, displayed, published, posted, licensed, framed, distributed or transmitted or any

of its contents disclosed to third parties without MSIM’s express written consent. This work may not be linked to

unless such hyperlink is for personal and non-commercial use. All information contained herein is proprietary

and is protected under copyright and other applicable law.

Eaton Vance is part of Morgan Stanley Investment Management. Morgan Stanley Investment Management is

the asset management division of Morgan Stanley.

This material may be translated into other languages. Where such a translation is made this English version

remains definitive. If there are any discrepancies between the English version and any version of this material

in another language, the English version shall prevail.

© 2023 Morgan Stanley. All rights reserved.

5980321 Exp. 09/30/2024

23

DISTRIBUTION

This communication is only intended for and will only be distributed to persons resident in jurisdictions

where such distribution or availability would not be contrary to local laws or regulations.

MSIM, the asset management division of Morgan Stanley (NYSE: MS), and its affiliates have

arrangements in place to market each other’s products and services. Each MSIM affiliate is regulated

as appropriate in the jurisdiction it operates. MSIM’s affiliates are: Eaton Vance Management

(International) Limited, Eaton Vance Advisers International Ltd, Calvert Research and Management,

Eaton Vance Management, Parametric Portfolio Associates LLC, and Atlanta Capital Management LLC.

This material has been issued by any one or more of the following entities:

EMEA

This material is for Professional Clients/Accredited Investors only.

In the EU, MSIM and Eaton Vance materials are issued by MSIM Fund Management (Ireland) Limited (“FMIL”).

FMIL is regulated by the Central Bank of Ireland and is incorporated in Ireland as a private company limited by

shares with company registration number 616661 and has its registered address at 24-26 City Quay, Dublin 2,

DO2 NY19, Ireland.

Outside the EU, MSIM materials are issued by Morgan Stanley Investment Management Limited (MSIM Ltd) is

authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. Registered in England. Registered No. 1981121.

Registered Office: 25 Cabot Square, Canary Wharf, London E14 4QA.

In Switzerland, MSIM materials are issued by Morgan Stanley & Co. International plc, London (Zurich Branch)

Authorised and regulated by the Eidgenössische Finanzmarktaufsicht ("FINMA"). Registered Office:

Beethovenstrasse 33, 8002 Zurich, Switzerland.

Outside the US and EU, Eaton Vance materials are issued by Eaton Vance Management (International) Limited

(“EVMI”) 125 Old Broad Street, London, EC2N 1AR, UK, which is authorised and regulated in the United

Kingdom by the Financial Conduct Authority.

Italy: MSIM FMIL (Milan Branch), (Sede Secondaria di Milano) Palazzo Serbelloni Corso Venezia, 16 20121

Milano, Italy. The Netherlands: MSIM FMIL (Amsterdam Branch), Rembrandt Tower, 11th Floor Amstelplein 1

1096HA, Netherlands. France: MSIM FMIL (Paris Branch), 61 rue de Monceau 75008 Paris, France. Spain:

MSIM FMIL (Madrid Branch), Calle Serrano 55, 28006, Madrid, Spain. Germany: MSIM FMIL Frankfurt Branch,

Große Gallusstraße 18, 60312 Frankfurt am Main, Germany (Gattung: Zweigniederlassung (FDI) gem. § 53b

KWG). Denmark: MSIM FMIL (Copenhagen Branch), Gorrissen Federspiel, Axel Towers, Axeltorv2, 1609

Copenhagen V, Denmark.

MIDDLE EAST

Dubai: MSIM Ltd (Representative Office, Unit Precinct 3-7th Floor-Unit 701 and 702, Level 7, Gate Precinct

Building 3, Dubai International Financial Centre, Dubai, 506501, United Arab Emirates. Telephone: +97 (0)14

709 7158).

This document is distributed in the Dubai International Financial Centre by Morgan Stanley Investment

Management Limited (Representative Office), an entity regulated by the Dubai Financial Services Authority

(“DFSA”). It is intended for use by professional clients and market counterparties only. This document is not

intended for distribution to retail clients, and retail clients should not act upon the information contained in this

document.

U.S.

NOT FDIC INSURED | OFFER NO BANK GUARANTEE | MAY LOSE VALUE | NOT INSURED BY ANY

FEDERAL GOVERNMENT AGENCY | NOT A DEPOSIT

© 2023 Morgan Stanley. All rights reserved.

5980321 Exp. 09/30/2024

24

ASIA PACIFIC

Hong Kong: This material is disseminated by Morgan Stanley Asia Limited for use in Hong Kong and shall only

be made available to “professional investors” as defined under the Securities and Futures Ordinance of Hong

Kong (Cap 571). The contents of this material have not been reviewed nor approved by any regulatory authority

including the Securities and Futures Commission in Hong Kong. Accordingly, save where an exemption is

available under the relevant law, this material shall not be issued, circulated, distributed, directed at, or made

available to, the public in Hong Kong. Singapore: This material is disseminated by Morgan Stanley Investment

Management Company and should not be considered to be the subject of an invitation for subscription or

purchase, whether directly or indirectly, to the public or any member of the public in Singapore other than (i) to

an institutional investor under section 304 of the Securities and Futures Act, Chapter 289 of Singapore (“SFA”);

(ii) to a “relevant person” (which includes an accredited investor) pursuant to section 305 of the SFA, and such

distribution is in accordance with the conditions specified in section 305 of the SFA; or (iii) otherwise pursuant

to, and in accordance with the conditions of, any other applicable provision of the SFA. This publication has not

been reviewed by the Monetary Authority of Singapore. In cases where you are dealing with a representative

of [insert name of Notified Foreign Entity (FYI - link to the NFE Here], and where such representative is acting

on behalf of [insert name of Notified Foreign Entity], please note that such representative is not subject to

regulatory requirements issued by the Monetary Authority of Singapore nor is under the supervision of the

Monetary Authority of Singapore. For any issues which may arise in your dealing with such representative,

please approach the Singapore-based contact person who has been established as your local contact person.

Australia: This material is provided by Morgan Stanley Investment Management (Australia) Pty Ltd ABN

22122040037, AFSL No. 314182 and its affiliates and does not constitute an offer of interests. Morgan Stanley

Investment Management (Australia) Pty Limited arranges for MSIM affiliates to provide financial services to

Australian wholesale clients. Interests will only be offered in circumstances under which no disclosure is required

under the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (the “Corporations Act”). Any offer of interests will not purport to be an

offer of interests in circumstances under which disclosure is required under the Corporations Act and will only

be made to persons who qualify as a “wholesale client” (as defined in the Corporations Act). This material will

not be lodged with the Australian Securities and Investments Commission.

Japan