THE CASE FOR FAIR

HOUSING

THE CASE FOR FAIR HOUSING

2017 Fair Housing Trends Report

THE CASE FOR FAIR HOUSING

Acknowledgments

The National Fair Housing Alliance would like to thank the U.S. Department of Housing and

Urban Development, the U.S. Department of Justice, Fair Housing Assistance Program agencies,

and private, nonprot fair housing organizations for providing the critical data included in this

report. The charts in this report were created by the National Fair Housing Alliance staff using

the data provided. National Fair Housing Alliance staff would also like to thank the American-

Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee (ADC) for providing data and insight into housing-related

hate complaints reported through their networks.

About the National Fair Housing Alliance

Founded in 1988 and headquartered in Washington, DC, the National Fair Housing Alliance

(NFHA) is the only national organization dedicated solely to ending discrimination in housing.

NFHA is the voice of fair housing and works to eliminate housing discrimination and to ensure

equal housing opportunity for all people through leadership, education and outreach, membership

services, public policy initiatives, community development initiatives, advocacy, and enforcement.

NFHA is a consortium of more than 220 private, nonprot fair housing organizations, state and

local civil rights agencies, and individuals from throughout the United States. NFHA recognizes

the importance of home as a component of the American Dream and aids in the creation of

diverse, barrier-free communities throughout the nation.

2

2017 FAIR HOUSING TRENDS REPORT

PROLOGUE

If there is one key thing to be learned from this report, it is that we did not

get here by accident. By “here,” we mean a nation segregated largely along

racial and ethnic lines, with opportunities in abundance in some communities

and severely or wholly lacking in others. Children do not go to lower quality

schools by choice or eat unhealthy food because that is what they like. Children

go to different quality schools and eat different quality food because that is

what is available to them. Segregated communities do not exist by accident.

Disparities in opportunity do not exist by accident.

This is the story of segregation in the United States. We need to know the story

and learn from the story, and do something meaningful to change the arc of the

story. The story goes back hundreds of years and its chapters are headlines

about governmental policies, industry practices, and individual discrimination.

The word racism is not written on any page, but it can be read between the

lines. It’s a story of racially-restrictive real estate covenants, toxic red lines on

mortgage lending maps, blockbusting and racial steering by real estate agents,

redlining by homeowners insurance companies, exclusionary zoning by local

communities, and community opposition to affordable housing. It goes back to

land grants and housing opportunities for White persons that were deliberately

and structurally denied to Black people, and it comes forward to the millions of

instances of housing discrimination perpetuated today and the deliberate acts

of institutions and communities to prevent people of color from living in their

neighborhoods. Segregated communities do not exist by accident. Disparities

in opportunity do not exist by accident.

And that means we can do something about it.

We have a tool, an incredible tool: The Fair Housing Act. The Fair Housing Act

was passed to honor the legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Dr. King had a

powerful vision of what our nation could look like. . . what our nation could be.

The Fair Housing Act could get us there. And we would all be better off for it.

This is The Case for Fair Housing.

73

THE CASE FOR FAIR HOUSING

3

6

12

14

14

16

25

26

29

40

41

42

43

45

45

46

48

50

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Prologue

Executive Summary

The Case for Funding Fair Housing

Section I. The Policies and Practices that Created and

Sustain Residential Segregation

The Foundation of Residential Segregation

Government Policies that Shaped Segregation

Discrimination in the Provision of Homeowners Insurance

Discrimination and Segregation on the Basis of Disability

The Engines of Residential SegregationToday

Section II. Segregation Today and Why it Matters

Educational Attainment

Health and Well-Being

Access to Transportation

Policing and Criminal Justice

The Racial Wealth Gap: Employment, Homeownership and

Wealth Building

The Benets of Diversity

Section III. The Infrastructure to Combat Housing

Discrimination and Dismantle Residential Segregation

The Role of Private Organizations in Fair Housing Enforcement

2017 FAIR HOUSING TRENDS REPORT

Testing: A Powerful Tool for Fair Housing Enforcement

Investigations

HUD, DOJ, and the CFPB in Combating Housing

Discrimination

Section IV. Overview of Housing Discrimination

Reported in 2016

National Data by Basis of Discrimination

Housing Discrimination Complaint Data by Transaction Type

Complaint Data Reported by HUD and FHAP Agencies

Complaint Data Reported by DOJ

Section V. Fair Housing Case Highlights and Featured

Issues from 2016

2016 Case Highlights

Featured Issues in Fair Housing

Addressing Fair Housing Issues Online: The Shared Economy

and Social Media

Fighting Hate with Fair Housing Laws

Dismantling Segregation by Afrmatively Furthering Fair

Housing

Section VI. Recommendations

51

65

76

79

81

83

86

88

88

93

94

95

98

101

THE CASE FOR FAIR

HOUSING

We live in a society that is racially and economically divided. In fact, the U.S ranks lowest when

compared to other well-to-do countries when it comes to data on poverty, employment, income

and wealth inequality, education, health inequality, and residential segregation.

1

The inequalities of

today were centuries in the making– resulting from government policy, housing industry practices,

individual acts of discrimination, and local zoning and land use barriers. Current policies and

practices reinforce and perpetuate segregation and inequality. We simply cannot prosper as a

nation with this level of inequality and division. Housing lies at the very center of this phenomenon.

What we do about access to housing opportunity and the dismantling of segregation affects the

entire fabric of our nation. The achievement of fair housing and dismantling of segregation are

essential to creating access to opportunity for everyone. In this 2017 Fair Housing Trends

Report, we make The Case for Fair Housing.

Every major metropolitan area in the United States is heavily segregated by race and ethnicity,

but we did not come to this deeply divided state by accident (Section I). Decades of government

policymaking and rampant housing discrimination shaped the segregated neighborhoods that

we see today. Many of these government policies originated in the 1930s and 1940s. The

most notable among them related to discrimination in public housing, the Home Owners Loan

Corporation (HOLC), and the Federal Housing Administration (FHA). In tandem with these

government policies were systemic practices in the private housing market, including racially

restrictive covenants, discrimination by the real estate industry, and redlining by lending and

homeowners insurance corporations.

Contemporary versions of the same practices continue to this day. Racial and ethnic disparities

in access to credit, the compounding effects of the subprime lending and foreclosure crisis,

and modern practices of discrimination, racial steering, and redlining have perpetuated racial

segregation. As a result, in today’s America, approximately half of all Black persons and 40 percent

of all Latinos live in neighborhoods without a White presence. The average White person lives

in a neighborhood that is nearly 80 percent White. Persons with disabilities are also often

segregated or prevented from living in their community of choice, both because a great deal of

housing is inaccessible and because they experience high levels of discrimination.

Where one lives determines one’s access to an array of opportunities and dictates many life

outcomes around education, employment, health, and wealth (Section II). Widespread residential

1 Grusky, David and Clifton B. Parker, “Stanford report shows that U.S. performs poorly on poverty and inequality mea-

sures.” Stanford News, February 2, 2016. Available online at: http://news.stanford.edu/2016/02/02/poverty-report-grusky-020216/.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

6

2017 FAIR HOUSING TRENDS REPORT

THE CASE FOR FAIR

HOUSING

segregation has gone hand in hand with mechanisms to limit opportunity and home ownership

in neighborhoods of color, leading to signicant gaps in racial and ethnic wealth and achievement.

These mechanisms include lack of access to quality credit, lack of investment, absence of jobs

or transportation to jobs, insufcient fresh food and quality health care, and inadequate public

institutions, schools, and services. This is not only harmful for those living in neighborhoods of

color: Ensuring that every neighborhood is a place of opportunity is fundamental to America’s

success in a world that is increasingly interconnected with a global economy that is highly

competitive.

Fortunately, there is an infrastructure in place to help us pursue the promise of equal access to

opportunity for all. The Fair Housing Act lies at the center of this structure (see Section III for

more information about the Fair Housing Act). Private fair housing organizations and several

government agencies and programs make up the framework that tackles housing inequality. These

organizations, and private fair housing agencies in particular, do tremendous work in educating

consumers and the industry about their rights and responsibilities; assisting individuals and

families who are victims of housing discrimination; and addressing systemic barriers to housing

opportunity that perpetuate segregation. These organizations process signicant numbers of

complaints, but the number of complaints represents only the tip of the iceberg that is the

incidence of housing discrimination. Thousands of cases have been brought to secure the rights

of individuals and to eliminate policies and practices that deny housing opportunity.

Despite this work, however, the rates of housing discrimination and segregation that occur in our

nation today signify that we need a stronger, better-funded, more effective system for addressing

discrimination and segregation.

Every year, the National Fair Housing Alliance (NFHA) compiles data from a comprehensive set

of fair housing organizations and government agencies to provide a snapshot of what housing

discrimination looks like today (Section IV). Some of the highlights from the 2016 data include

the following data points:

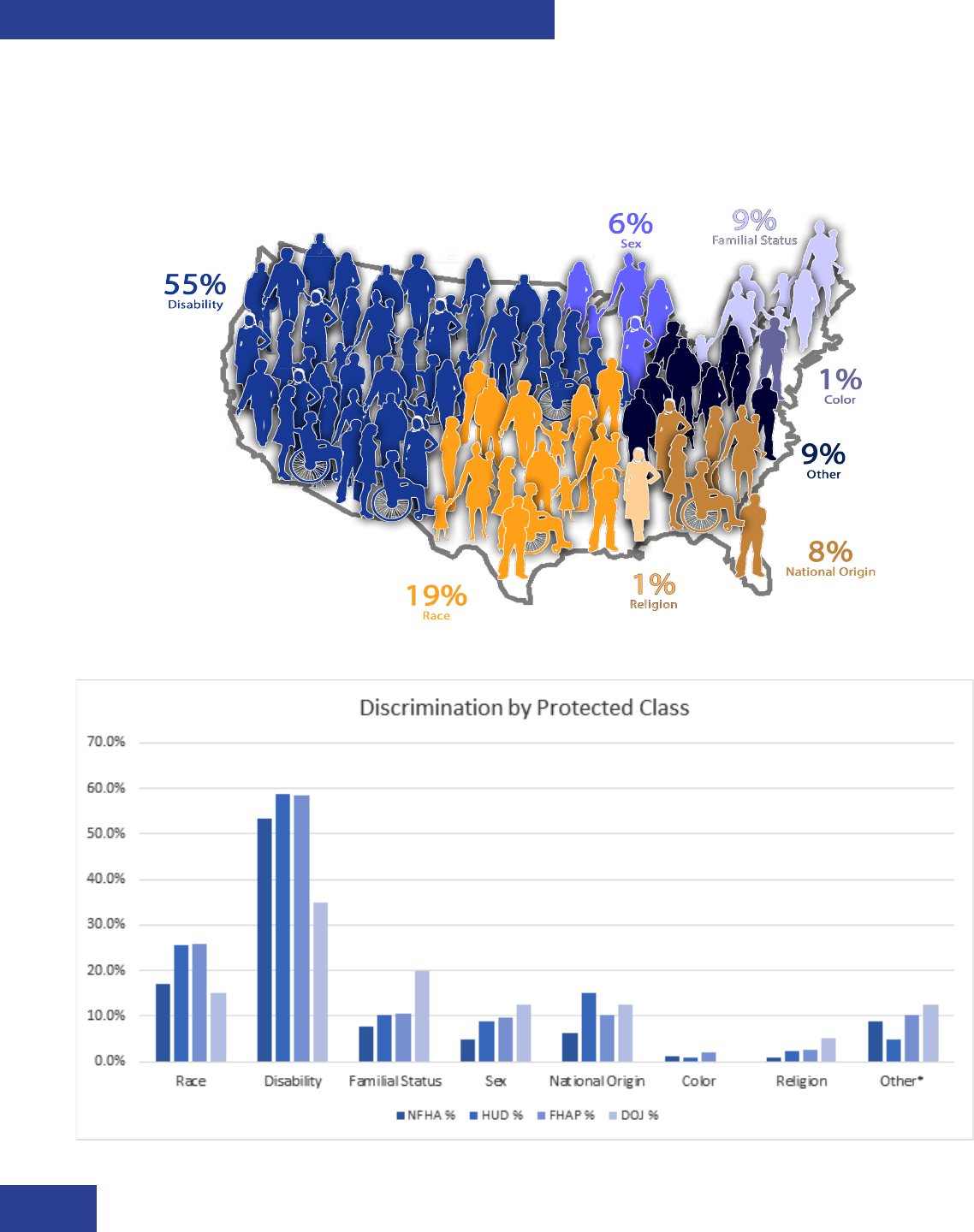

• There were 28,181 reported complaints of housing discrimination in 2016. Of these, private

fair housing organizations were responsible for addressing 70 percent, the lion’s share of all

housing discrimination complaints nationwide.

• 55 percent of these complaints involved discrimination on the basis of disability, followed by

19.6 percent based on racial discrimination, and 8.5 percent based on discrimination against

families with kids.

• 91.5 percent of all acts of housing discrimination reported in 2016 occurred during rental

transactions.

There were also a number of notable fair housing cases in 2016 that highlight the persistence

and variability of housing discrimination in this nation (Section V). These include the following

7

THE CASE FOR FAIR HOUSING

THE CASE FOR FAIR

HOUSING

allegations:

• widespread sexual harassment by

a housing authority’s employees;

• racially restrictive bylaws of a

homeowners’ association;

• a University’s practice of

denying its students’ reasonable

accommodation requests;

• discriminatory targeting of

lending services away from Black

mortgage applicants;

• denial of mobile home rentals to

Black applicants;

• discriminatory identication

requirements of prospective

renters from foreign countries;

• denial of an affordable housing

zoning application in response to

discriminatory opposition;

• discriminatory concentration of

affordable housing;

• refusal to rent to people with

mental disabilities;

• discriminatory targeting

of predatory loans against

borrowers renancing their

mortgages;

• an insurance policy limiting

coverage for landlords that rent

to Section 8 tenants;

• a city’s practice of administering

housing programs that are

not accessible to people with

disabilities;

• failure to design and construct

accessible multifamily housing;

and

• discriminatory maintenance and

marketing of bank-owned, post-

foreclosure properties.

A few key issues were additionally

2017 FAIR HOUSING TRENDS REPORT

THE CASE FOR FAIR

HOUSING

important in 2016. The rst, brought to light by recent actions by Facebook and Airbnb, involves

fair housing rights in the context of social media platforms and in the shared economy. The

second addresses the need to apply fair housing laws in counteracting the recent surge in hate

crimes, harassment, and housing-related hate activity. And third, the rst round of cities and

jurisdictions required to implement HUD’s new Afrmatively Furthering Fair Housing rule took

their initial steps in 2016, and we are in the process of learning how these requirements will help

us fulll our promise as a nation to dismantle residential segregation and promote opportunity

in all neighborhoods.

There are a number of ways we can better tackle housing discrimination, address segregation,

and work toward a more inclusive society (Section VI). Among these are the following

recommendations:

• Congressandthefederal government mustsignicantlyincreasethe levelof

funding for private fair housing organizations, HUD, and public enforcement

agencies at the state and local level to launch a large sustained effort to support

existing and create additional fair housing organizations, foster systemic approaches to

eliminating segregation, and address governmental and institutional barriers at local levels.

• The philanthropic and corporate community must provide meaningful and

substantive support for fair housing as part of a holistic approach to achieving lasting

change.

• Createan independent FairHousingAgencyor reform HUD’s Ofce of Fair

Housing and Equal Opportunity. A strong, independent fair housing agency could

more effectively address discrimination and segregation throughout the United States. In

the absence of such an organization, HUD should be restructured so that the Ofce of Fair

Housing and Equal Opportunity plays a more meaningful role and functions effectively in its

many important responsibilities.

• Strengthen the Fair Housing Initiatives Program to support qualied, full-service

nonprot fair housing centers that provide the bulk of fair housing education and enforcement

services to our nation. This includes funding the program at a minimum level of $52 million.

• Effectively implement the Afrmatively Furthering Fair Housing Rule and

hold grantees accountable to break down barriers to opportunity and ensure that all

communities are inclusive and that individuals have access to the opportunities they need

to ourish.

• Improve equal access to credit so that individuals and communities previously denied

quality credit at a fair price may have fair access to good credit that supports home ownership,

small businesses, and economic growth.

9

THE CASE FOR FAIR HOUSING

• Reestablish the President’s Fair Housing Council to establish a multidisciplinary

approach well suited to addressing the policies and systems that have a discriminatory impact,

perpetuating entrenched patterns of metropolitan segregation.

The Fair Housing Act was designed to achieve two goals: to eliminate housing discrimination and

to take signicant action to overcome historic segregation and achieve inclusive and integrated

communities. But as Senator Edward Brooke, co-author of the Fair Housing Act, stated in a

2003 speech, “The law is meaningless unless you’re able to enforce that law. It starts at the top.

The President of the U.S., the Attorney General of the U.S., and the Secretary of HUD have a

constitutional obligation to enforce fair housing law.”

2

Indeed, our elected leadership has the

obligation to work toward making racially, ethnically, and economically integrated neighborhoods

a reality, and we as citizens have an obligation to demand that change through policymaking and

strong enforcement.

Achieving a more equitable society represents a signicant challenge, but it is attainable. As Justice

Kennedy stated in the 2015 Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs v. The Inclusive

Communities Project Supreme Court opinion: “Much progress remains to be made in our nation’s

continuing struggle against racial isolation. In striving to achieve our ‘historic commitment to

creating an integrated society,’ we must remain wary of policies that reduce homeowners to

nothing more than their race.” He then concludes by saying: “The court acknowledges the Fair

Housing Act’s role in moving the nation toward a more integrated society.”

3

Though challenges continue to be placed in our way, it is possible for our nation to move toward

a society that is integrated and inclusive, and in which everyone has equal access to opportunity.

It begins with fair housing.

2 Senator Edward Brooke, Remarks at the National Fair Housing Alliance National Conference, June 30, 2003.

3 Decision available online at: https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/14pdf/13-1371_m64o.pdf.

Note: In this report, we focus largely on segregation on the basis of race (Black/White). Discrimination and segregation

on the basis of race is foundational to the discussion of inequities in this nation and the urban neighborhood construct.

We are also well aware of discrimination against and segregation of Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Peoples, and others

and the ramications of this behavior on current practices and strategies for dismantling segregation and addressing

discrimination against persons in all protected classes. This report focuses largely, however, on Black/White segregation.

Note on language in this report: As a civil rights organization, we are aware that there is not universal agreement

on the appropriate race or ethnicity label for the diverse populations in the United States or even on whether or not

particular labels should be capitalized. We intend in all cases to be inclusive, rather than exclusive, and in no case to

diminish the signicance of the viewpoint of any person or to injure a person or group through our terminology. For

purposes of this report, we have utilized the following language (except in cases where a particular resource, reference,

case or quotation may use alternate terminology): Black, Latino, Asian American, and White. In prior publications, we

THE CASE FOR FAIR HOUSING

10

2017 FAIR HOUSING TRENDS REPORT

11

have utilized the term “African American,” but there are some who argue that this term is exclusive and we intend to be as inclusive as

possible. We are also aware than many persons prefer the term “Hispanic.” We intend in this report to include those who prefer “Hispanic”

in the term “Latino” and intend no disrespect. We refer to “neighborhoods of color” or specify the predominant race(s) of a neighborhood,

rather than utilizing the term “minority.” We also use the term “disability,” rather than “handicap” (the term used in the Fair Housing Act”).

THE CASE FOR FAIR

HOUSING

The importance of increased funding and support of fair housing education and enforcement

is far too important to place in the recommendations section at the end of this report. Fair

housing and the creation of inclusive, diverse communities are the underpinnings of opportunity,

economic and business success, community harmony, and the very fabric of a successful nation.

Yet fair housing education and enforcement programs, both public and private, are not a national

priority and are severely underfunded. They are not just underfunded by millions of dollars. They

are underfunded by hundreds of millions of dollars, perhaps billions. Why is that?

Part of the problem is that many of those who regard themselves as unaffected by inequities do

not care that there are inequities. Some may believe they are insulated from inequities because

of their wealth, race, religion, family status, or lack of a disability. But all communities do better—

all people do better—when others do better. Increased opportunity for all does not mean

decreased opportunities for others.

Part of the problem is that many prospective funders of fair housing are hesitant to support fair

housing initiatives because they have the misconception that the work being done is somehow

in conict with their mission or corporate agenda, when nothing could be further from the

truth. If a corporation supports the efforts of a local fair housing organization to enforce the law

against discriminatory real estate companies or lending institutions, the corporation’s employees,

customers, and communities all benet. Funders need to understand the benets of fair housing

to the other work they do, the communities they serve, their employees and customers, and their

bottom line.

Part of the problem is that the fair housing advocacy community is modest in scale, due to lack

of resources and lack of understanding by the public and decision-makers about the critical role

housing discrimination plays in the inequities of our entire society. This lack of funding keeps

the knowledge level about the importance of fair housing low, which further prevents us from

obtaining the substantial funding required to address this critical component of a prosperous,

productive, and harmonious nation.

Perhaps the biggest problem is that the discrimination/segregation problem is so big and the

consequences so enormous that it can seem as though progress is impossible. As long as we

believe that, meaningful progress will be difcult, but it’s not impossible. Organizations like NFHA

have made tremendous advancements in reducing discrimination and segregation, but have not had

access to consistent and sufcient funding to maintain advancements or build momentum when

important milestones are achieved. This dynamic needs to change in a dramatic and meaningful

way.

THE CASE FOR FUNDING FAIR HOUSING

THE CASE FOR FAIR HOUSING

12

2017 FAIR HOUSING TRENDS REPORT

Congress and the federal government

must signicantly increase the level

of funding for private fair housing

organizations, HUD, and public

enforcement agencies at the state

and local level. States and localities

should provide funding for fair housing as

well. There must be a large sustained effort

to support existing and create additional

fair housing organizations, foster systemic

approaches to eliminating segregation, and

address governmental and institutional

barriers at local levels. This has to include

funds for creating a sufcient pool of

workers, sustained training, education

and outreach, systemic investigations,

cooperation with industry, advocacy for

better laws and regulations, etc. This has

to include funds to educate people about

their fair housing rights and responsibilities and

the importance of fair housing to every person in this nation.

The philanthropic and corporate community must provide meaningful and

substantive support for fair housing. These organizations must understand that achieving

meaningful and lasting change requires a holistic approach. Every foundation that supports

education, health, employment, access to credit, etc. should also be supporting fair housing. Every

corporation that donates to community development, public service, job training, and other

revitalization strategies should also be supporting fair housing. Housing opportunity affects

all those things supported by foundations and corporations: education, health, employment,

transportation, quality food and environment, public services…everything. Tackling these

problems cannot be done piecemeal, and they cannot be ameliorated without addressing the

key fair housing issues that helped create these problems in the rst place. Instead of seeing

the problem of segregation as intractable, it should be seen as foundational. You can pour all

the money in the world into inequities in all these other areas, but if you do not address the

segregation and discrimination that are the foundation of these inequities, it will be difcult to

make any meaningful progress.

Money is never the entire answer to any problem. But if one had to identify a single program to

support that would have the greatest positive impact on the health and welfare of this nation, it

would be fair housing.

13

THE CASE FOR FAIR

HOUSING

“

“

Congress and the

federal government

mustsignicantly

increase the level of

funding for private fair

housing organizations,

HUD, and public

enforcement agencies

at the state and local

level.

THE CASE FOR FAIR HOUSING

Segregation did not happen by accident. In

this chapter, we provide an overview of some

of the policies and practices that created and

perpetuate the existence of segregation in

the United States. Segregation is not by itself,

perhaps, inherently bad, although it chafes at

the very principles on which our nation was

founded. But segregation does not exist in a

void. It has been accompanied by actions that

have turned many neighborhoods of color

into neighborhoods without access to quality

credit or investments, good schools, healthy

food, safe streets, a healthy environment,

affordable and reliable transportation, good

jobs, and the other opportunities people need

to ourish. Making all of our neighborhoods

places of opportunity is fundamental to

America’s success in a world that is increasingly

interconnected and in a global economy that is

highly competitive. In order to do so, we must

understand how we got here so we can more

effectively implement quality solutions.

Although we have made progress over the years, we live in a country that is heavily segregated. This

segregation has an impact on each of us individually and on our nation as a whole. Many people assume

that the segregated neighborhoods that exist in virtually all American cities result from the aggregated

choices of many individuals, each choosing to live near people who “look like them.” A review of our

history, however, shows other forces at work: For more than a century, achieving and maintaining

segregated neighborhoods was inherent in the practices of lending institutions, real estate agents, and

neighborhood associations. At the same time, residential segregation was also the explicit policy of the

government at the federal, state, and local levels.

The Foundation of Residential Segregation

To fully understand the segregation that exists in our neighborhoods today, we have to look back to

SECTION I. THE POLICIES AND PRACTICES THAT

CREATED AND SUSTAIN RESIDENTIAL SEGREGATION

14

In this Section...

We cover:

• How a combination of government

policymaking and systemic practices

in the private market shaped the

segregated neighborhoods we see

today.

• Discrimination against and segregation

of people with disabilities

• How contemporary versions of

the same practices continue today,

including modern-day redlining,

steering, the existance of a dual credit

market, and the compoudning effects

of subprime, predatory lending and

foreclosure crisis.

2017 FAIR HOUSING TRENDS REPORT

the Colonial Era, when headrights (land grants) were given to new settlers.

4

Created with the

establishment of Jamestown, Virginia, and eventually expanded throughout the early colonies, new

arrivers, willing to work hard, received free land to establish homes and farms. In much the same

way, Land Grants were issued to veterans serving in the American Revolutionary War as payment

and compensation for service. Later, the homestead grant system was enacted under President

Abraham Lincoln to award land to pioneers willing to build homes, farms, and other businesses

in newly established states and territories. The Homestead Act encouraged westward migration

and provided settlers with 160 acres of land each to use for their own enterprises. Once the

homesteaders fullled their obligations, the land and the wealth that came with it belonged to

them. By 1900, the U.S. had issued 80 million acres of land to people establishing new residencies;

5

ultimately, 270 million acres were given to U.S. citizens.

6

Headrights, Land Grants, and Homestead

Grants enabled millions of people

7

to obtain homeownership status and amass land and wealth for

themselves and their families. However, these laws primarily beneted Whites. People of color,

and in particular Black people, could not take advantage of these programs.

Headrights were given to slave owners for each slave the petitioner imported into the U.S., receiving

50 acres of land for every imported slave, until the system was changed. Homestead grants were

issued to a head of household who was “a citizen of the United States.”

8

Of course, Blacks did not

wholly obtain citizenship status until the 14th Amendment was passed in 1868.

9

But discrimination

against people of color in the Homestead program was prolic, and Congress was compelled

during the Reconstruction Era to include language in an amendment to the Homestead Act that

made it illegal to make a distinction “on account of race or color”

10

in the issuance of homesteads.

According to housing scholar and historian Douglas Massey, there was a short time after the Civil

War when “it seemed that Blacks might actually assume their place as full citizens of the United

States.”

11

But by the time the Reconstruction Era came to a close in 1877, the tone of the nation,

particularly at the federal level, changed dramatically. All of the Black members of Congress were

kicked out. The nation’s initial attempt to “reconstruct” the South and create a nation where

people of color could continually gain equal access to opportunities was stopped cold. Jim Crow

laws were passed throughout the country, with many of these laws used to create segregated

residential communities, create opportunities for Whites, or prevent people of color from gaining

access to the same benets.

4 See, for example, the First Charter of Virginia, which granted 50 miles of land to certain colonists arriving at the Virginia Colony in 1609. Avail-

able at: http://avalon.law.yale.edu.

5 https://www.loc.gov/rr/program/bib/ourdocs/Homestead.html.

6 The government gave away 270 million acres of land or 10% of the country’s total land area. The overwhelming majority of this land was given

to White citizens. http://www.pbs.org/race/000_About/002_04-background-03-02.htm.

7 Over 1.6 million Homestead grants were granted by the United States government. See https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/home-

stead-act.

8 37th Congress, Session II, Chapter 75, 1862. See Homestead Act, available at https://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=llsl&leName=012/

llsl012.db&recNum=423.

9 The Civil Rights Act of 1866 did confer citizenship status to Black persons; however, there was a great deal of controversy about whether or

not Congress had the authority to grant citizenship to people in his manner. When the 14th Amendment was ratied in 1868, that sealed the

matter. The bestowment of citizenship status for Black Americans was now a part of the Constitution.

10 See Revised Statutes of the Homestead Act, Section 2302, 424 available at https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/ pt?id=hvd.32044103137394;view=1

up;seq=444.

11 Douglas S. Massey, “Origins of Economic Disparities: The Historical Role of Housing Segregation,” in James H. Carr and Nandinee K. Kutty,

eds., Segregation: The Rising Costs for America (New York: Routledge, 2008), pp. 39-80, p. 40.

15

THE CASE FOR FAIR HOUSING

Racist attitudes became more prevalent and their manifestations, including violence and

destruction of property (often with dynamite), became increasingly harmful. Increasingly more

common during the 1920s and thereafter, White elected ofcials, developers, lenders and residents

established discriminatory housing and zoning policies and practices designed to insulate “their”

neighborhoods from Black residents. Various “neighborhood improvement associations” worked

to win zoning restrictions that would fall hardest on Black households, threatened to boycott real

estate agents who were willing to work with Black homebuyers, and sought to increase property

values so they would only be within the reach of White buyers. Contracts, known as “restrictive

covenants,” were drawn up among residents of a neighborhood so that White residents were

legally prohibited from selling or renting to prospective Black residents and other people of color.

12

Government Policies that Shaped Segregation

As these practices were ongoing, government agencies followed a similar trajectory. This history

set the stage for many of the government policies that were put in place in the 1930s and 40s,

between the Great Depression and the immediate aftermath of World War II. Most notable among

these were policies related to public housing, the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC), and

the Federal Housing Administration (FHA). While these New Deal programs delivered great

benets to many White Americans, they did just the opposite for people of color.

Public Housing

Public housing in the United States has its roots in the New Deal and evolved through and beyond

the post-World War II era. The debate over public housing invoked questions of what to do about

low-income, inner-city neighborhoods that were seen by some as slums, whether and how the

government should provide for the housing needs of its citizens, and whether government action

in this arena would compete with the private sector. Embedded in the debate over all of these

issues was the question of race and whether or not government policy should address racial

segregation.

The United States Housing Act of 1937 established a federal public housing authority to provide

nancial assistance to local public housing agencies to develop, acquire, and manage public housing

projects. The law also required that one unit of slum housing be demolished for every public

housing unit built.

13

Under the administration of Harold Ickes, the program had a rule that public

housing could not alter the racial characteristics of the neighborhood in which it was located.

14

Against

a backdrop of policies and practices that created segregated communities, this meant that public

housing was also segregated. Only a modest number of units were developed under this program,

and it was not until after World War II that Congressional attention returned to the issue of public

12 See NFHA’s 2008 Trends Report for more on this topic.

13 von Hoffman, Alexander, “A Study in Contradictions: The Origins and Legacy of the Housing Act of 1949.” Housing Policy Debate, Volume 11,

Issue 2. Fannie Mae Foundation, 2000.

14 Richard Rothstein, “The Making of Ferguson,” The American Prospect, Fall, 2014, available at http://prospect.org/article/making-ferguson-how-

decades-hostile-policy-created-powder-keg.

16

2017 FAIR HOUSING TRENDS REPORT

housing, in the Housing Act of 1949. That legislation authorized loans and subsidies for 135,000

low-rent units per year, up to a total of 810,000.

15

During the debate over the bill, opponents proposed a “poison pill” amendment requiring that

public housing be integrated. They knew that Southern Democrats, who otherwise supported

public housing, would not support the bill if it contained this provision. As described by Richard

Rothstein, “Liberals had to choose either segregated public housing or none at all. Illinois Senator

Paul Douglas argued, ‘I am ready to appeal to history and to time that it is in the best interests of

the Negro race that we carry through the [segregated] housing program as planned, rather than

put in the bill an amendment which will inevitably defeat it.’”

16

In the end, the Housing Act of 1949 did not address the question of segregation in public housing.

That was left to local ofcials. As a result, “. . . public housing programs were segregated by law in

the south and nearly always segregated in the rest of the country in deference to local prejudice,

with housing projects for Blacks usually adjoining segregated neighborhoods or built on marginal

land near waterfronts, highways, industrial sites, or railroad tracks. As one historian noted, ‘The

most distinguishing feature of post-World War II ghetto expansion is that it was carried out with

government sanction and support.’”

17

Home Owners Loan Corporation

The Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) was established in 1933, in the wake of the Great

Depression, with the mission of stabilizing the housing market and protecting homeownership.

At that time, the country was experiencing unprecedented rates of foreclosure. Between 1933

and 1935, the HOLC renanced more than 1 million mortgages–one in ten mortgages on owner-

occupied, non-farm residences in the country–to the tune of $3 billion.

18

One of the great contributions of the HOLC was the creation of the low down payment, long-

term, xed-rate, fully-amortizing mortgage. Although the 30 year, xed-rate loan is the most

common type of mortgage in the U.S. housing market today, before the HOLC mortgages had very

short terms (ve to ten years) and were non-amortizing, so that at the end of the ve- to ten-year

period, borrowers needed to take out a new loan to pay off the remaining principal balance. The

HOLC’s innovative mortgage product eliminated much of the volatility of the mortgage market

and made mortgages (and therefore homeownership) less risky for borrowers.

Because it played such a signicant role in the mortgage market, the HOLC was very concerned

15 The Housing Act of 1949 authorized $1 billion for loans and $500 million in grants to help cities acquire, assemble and redevelop slums and

blighted property for either public or private redevelopment. For more details, see von Hoffman, op.cit. and Abrams, op. cit.

16 Rothstein, op cit.

17 “The Future of Fair Housing: Report of the National Commission on Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity,” December, 2008. Available at

http://www.civilrights.org/publications/reports/fairhousing/historical.html#_ednref36.

18 Kenneth T. Jackson, “Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States,” New York, Oxford University Press, 1985, p. 196.

17

THE CASE FOR FAIR HOUSING

about understanding and assessing the factors that might contribute to mortgage risk, including

the risk that properties would decline in value. Such declines would mean that, if the borrower

defaulted, the home could not be sold at a high enough price to pay off the remaining loan

balance. Therefore, the HOLC undertook a survey to assess risk in cities all across the country–

virtually all of those with populations of 40,000 persons or greater. Through this undertaking, the

HOLC standardized and formalized the appraisal process. Its methodology was not new; rather, it

codied the typical private sector practices of the time, which reected a view of neighborhood

dynamics and their impact on property values that was blatantly discriminatory against Black

people, immigrants from certain countries, and some religious groups.

19

That view held that the

presence of these people contributed to neighborhood deterioration and the decline in property

values, and that clear lines of racial and social demarcation were necessary to protect property

values in the most desirable areas.

The HOLC appraisal methodology divided neighborhoods into four categories: Best, Still Desirable,

Denitely Declining, and Hazardous, or A, B, C and D. On the so-called Residential Security maps

on which its survey results were recorded, these were color-coded green, blue, yellow, and red,

respectively. Neighborhoods could be coded red, or “hazardous,” for a number of reasons, one

of which was the presence of Blacks or other “inharmonious” racial or social groups. This is the

origin of the term “redlining.” To view an example of one of these maps, see page 22.

The HOLC itself made loans in all types of neighborhoods, including some in those neighborhoods

coded yellow and red on the residential security maps. It had enormous inuence over the

practices of private lenders, however, and those lenders were more risk-averse. These institutions

used the HOLC’s neighborhood classication system to severely constrict the ow of mortgages

to neighborhoods with the lowest ratings. Further, its methodology inuenced another federal

housing agency, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA). Thus, the HOLC set the stage for

widespread disinvestment in communities of color and the denial of mortgage credit to the

residents of those communities. This, in turn, severely constrained the housing choices available

to Blacks and other people of color. As noted by Douglas S. Massey and Nancy A. Denton in

their book, American Apartheid, “[The HOLC] lent the power, prestige and support of the federal

government to the systematic practice of racial discrimination in housing.”

20

We know that Latinos are largely segregated from White, non-Hispanic neighborhoods. However,

historical housing discrimination specically against Latinos is not well documented. This may be

due in part to the fact that experience varied signicantly depending on geographic region and

because of the variety of races and national origins that are considered Hispanic or Latino. A

range of discriminatory policies and practices did exist and actively separated Latinos from White

residential communities. In the Los Angeles region, for example, the 1939 HOLC categorization

of neighborhoods characterized Mexicans in one neighborhood as “the right mix of social class,

19 The most extensive set of HOLC maps available, many accompanied by the descriptions that explain the classication assigned to each neigh-

borhood, can be found on the website “Mapping Inequality,” at https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/#loc=4/36.71/-96.93&opacity=0.8.

20 Douglas S. Massey and Nancy A. Denton, “American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass,” Harvard University Press,

Cambridge, MA, 1993. p. 53.

18

2017 FAIR HOUSING TRENDS REPORT

occupation, and skin color to ‘climb the ladder

of whiteness.’” This neighborhood received a

“C” rating. On the other hand, in the nearby

San Gabriel Valley Wash neighborhood, one

assessor referred to the neighborhood

as full of “dark skinned babies” and “peon

Mexicans.” It comes as no surprise that the

neighborhood was assigned a “D” rating –

hazardous.

21

Federal Housing Administration

The Federal Housing Administration was

established by the National Housing Act of

1934,

22

one year after the HOLC. FHA was intended to help stabilize the mortgage market, facilitate

safe and sound mortgage lending on reasonable terms, and alleviate the unemployment which

still plagued the nation in the post-Depression years, particularly in the construction industry.

23

Unemployment was high and the nation was experiencing a severe housing shortage, and FHA was

designed to help address both problems. It did this by insuring loans for both the construction

and the sale of new homes, thereby putting people to work in the construction trades and creating

new units to help meet housing demand. FHA built on the mortgage model developed by the

HOLC, adding minimum construction standards and low down payment requirements. Previously,

most mortgages required down payments of 30 percent or more, but FHA lowered the down

payment requirement to 10 percent, a much more manageable amount for working families. This

safer, more sustainable mortgage product resulted in signicantly lower default and foreclosure

rates, and thereby led to lower interest rates. The combination of a modest down payment

and lower interest rates made homeownership possible for many American families of modest

means. In fact, FHA loans were so accessible and affordable that it was often cheaper for families

to purchase new homes with loans insured by FHA than to rent existing homes of comparable

size. Families for whom homeownership had been previously out of reach were now able to build

wealth through the equity in their homes and nd a path to the middle class.

FHA support for builders spurred the construction of suburban tract developments all across

the country. Perhaps the most famous of these is Levittown, on New York’s Long Island, where

builders William and Alfred Levitt constructed 17,400 modestly-priced homes on what had been

4,000 acres of potato elds near the Town of Hempstead. The modest homes that families bought

21 Reft, Ryan, “Segregation in the City of Angels: A 1939 Map of Housing Inequality in L.A.” KCET Television, January 19, 2017. Available online at:

https://www.kcet.org/shows/lost-la/segregation-in-the-city-of-angels-a-1939-map-of-housing-inequality-in-la.

22 Pub.L. 84–345, 48 Stat. 847.

23 Douglas S. Massey and Nancy A. Denton, “American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass,” Harvard University Press,

Cambridge, MA, 1993. p. 53.

“

“

[The HOLC] lent the

power, prestige and

support of the federal

government to the

systematic practice of

racial discrimination in

housing.

19

THE CASE FOR FAIR HOUSING

for prices in the $8,000-10,000 range in the 1940s

24

now sell in the $400,000 price range.

25

In

other words, the families in Levittown for whom FHA loans made homeownership possible have

had the chance to amass signicant wealth through the home equity they built up. Unfortunately,

in accordance with FHA policy, all of those families were White.

Through its affordable mortgage product and its support for widespread suburban subdivisions,

FHA had an enormous impact on the development of American cities and suburbs and on the

homeownership rate in this country. FHA adopted the HOLC’s approach to the housing market,

including its residential security maps, appraisal methodology, and belief that the presence of Black

residents and other “undesirable” racial or social groups had a negative impact on neighborhood

stability and property values. These principles were enshrined in the FHA Underwriting Manual,

which stated, “If a neighborhood is to retain stability, it is necessary that the properties continue

to be occupied by the same social and racial classes.”

26

The manual advocated the use of deed

restrictions, both with respect to the types of structures built and the people who could occupy

them: “Sec. 228. Deed restrictions are apt to prove more effective than a zoning ordinance in

providing protection from adverse inuences. Where the same deed restrictions apply over a

broad area and where these restrictions relate to types of structures, use to which improvements

may be put, and racial occupancy, a favorable condition is apt to exist.”

27

(Emphasis added) In Sec.

284, the manual notes that recorded deed restrictions are the most effective and should include,

among other things, “(g) Prohibition of the occupancy of properties except by the race for which

they are intended.”

28

(Emphasis added) These provisions ensured that virtually no FHA-insured

loans were made to Black borrowers or other borrowers of color, and very few loans were made

in urban neighborhoods. Since most lenders followed FHA guidelines, this policy effectively cut

off mainstream mortgage credit in communities of color.

FHA had an equally devastating impact through its support of the construction of suburban

subdivisions. Builders seeking FHA insurance for construction loans were required to agree that

they would not sell any of those homes to Black buyers.

29

Further, FHA provided model restrictive

covenants for those builders to include in the deeds to the homes they built. According to the

housing advocate and scholar Charles Abrams, “the FHA framed the very restrictive covenants

which developers could and did use. All they had to do was copy the Federal form and ll in

the race or religion to be banned.”

30

Abrams characterized the role of the FHA this way, “the

Federal Housing Administration (FHA) moved forward to become the main bulwark of the racial

restrictive covenant. By insuring or refusing to insure mortgages in an area, its administrators

24 Jackson, p. 234-236.

25 Rothstein, Richard, “The Racial Achievement Gap, Segregated Schools, and Segregated Neighborhoods – A Constitutional Insult,” Economic

Policy Institute, November 12, 2014. Available online at: http://www.epi.org/publication/the-racial-achievement-gap-segregated-schools-and-

segregated-neighborhoods-a-constitutional-insult/.

26 Federal Housing Administration Underwriting Manual, 1938, cited in Abrams, Charles, “The Segregation Threat in Housing,” in Straus, Nathan,

“Two-Thirds of a Nation: A Housing Program,” Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1952.

27 1938 FHA Underwriting Manual, available at http://www.urbanoasis.org/projects/fha/FHAUnderwritingManualPtII.html#301.

28 Ibid.

29 Rothstein, op. cit.

30 Abrams, op. cit. p. 220.

20

2017 FAIR HOUSING TRENDS REPORT

became the sentinels of racial purity of the American neighborhood and the paladins of a new

American caste system.”

31

FHA facilitated White families’ moves to the suburbs and access to

homeownership, while at the same time preventing access and mobility for families of color. The

Veterans’ Administration, which provided mortgages with no down payments and low interest

rates to nearly 5 million veterans returning from World War II,

32

adopted the same policies,

providing White veterans entry to the middle class but barring access by most Black veterans and

other veterans of color.

These New Deal-era policies, in combination with declining housing construction costs, quickly

led to vast White suburbanization and the abandonment of urban centers. Urban centers

increasingly grew to be predominantly Black communities. During the 1950s and 1960s, federal

“redevelopment” and “urban renewal” programs were used to eliminate “urban blight” by razing

neighborhoods and Black-owned businesses. Many homeowners were relocated just blocks away

in neighborhoods Whites had abandoned, and low-income Black families were relocated to newly

constructed public housing that was pushed into the middle of the Black community, thereby

impeding encroachment of Black families into White areas.

33

The cumulative impact of HOLC and FHA coding policies, as well as other government policies, was

to limit housing choice for Blacks and other people of color, forcing them into highly segregated

neighborhoods. There, they often paid inated prices for poorly maintained housing and had

limited access to good schools, good jobs, affordable and reliable transportation, and many other

factors that characterize neighborhoods of opportunity.

This widespread segregation persisted over the following decades, and conditions in many

segregated communities deteriorated, due to lack of credit and investment, overcrowding, provision

of poor public services, etc. In the 1960s, with the rise of the Civil Rights Movement, residents

began to express their frustration and dissatisfaction in very public ways. In the summer of 1967,

racial uprisings occurred in more than 150 cities. Some of these were small demonstrations, but

others were riots much like those that broke out in Ferguson, Missouri, and Baltimore, Maryland,

in 2015. In a number of cases, the local police were unable to restore order and the National

Guard was called in. These uprisings forced the nation to confront the realities of life for people

living in segregated communities and the harm that segregation caused to those residents and the

nation as a whole.

In response to the riots, President Johnson established a commission to investigate what happened,

why it happened, and how it might be prevented from happening again. The Kerner Commission

(named after its chairman, Illinois governor Otto Kerner) visited a number of the cities where

demonstrations had occurred, spoke with many people who had been affected, and delved into

the historical policies and practices that created segregation. The Commission concluded that,

31 Ibid., p. 219.

32 Katznelson, Ira, “When Afrmative Action was White: An Untold History of Racial Inequality in Twentieth-Century America,” W.W. Norton &

Company, New York. 2005.

33 Massey, op. cit, P. 56.

21

MAP 3. From 2006

MAP 4. From 2015

#

MAP 1. From 1940

MAP 2. From 2005

Source: Ohio State University University Libraries, “Redlining Maps”. Available online at: http://guides.osu.edu/

maps-geospatial-data/maps/redlining/

Source: Coulton, Claudia and Kathy Hexter, “Facing the Foreclosure Crisis in Greater Cleveland: What happened

and how communities are responding.” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, June 2010, available at http://cua6.ur-

ban.csuohio.edu/publications/center/center_for_community_planning_and_development/Foreclosure_Report.pdf

Source: http://www.kirwaninstitute.osu.edu/reports/2008/09_2008_OpportunityMappingOverviewReport.pdf

Source: National Fair Housing Alliance, 2015

Map 1. This map of metropolitan Cleveland, Ohio, was created in the

1930s for the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC), a New Deal-

era federal agency whose mission was to stabilize the housing market by

renancing defaulted mortgages. Between 1933 and 1935, it renanced

more than 1 million loans that were in default and in danger of foreclosure.

In some 250 cities across the country, local real estate industry members

used the HOLC’s methodology to rate neighborhoods as either Best,

Still Desirable, Denitely Declining, or Hazardous. These neighborhoods

were coded in green, blue, yellow, and red, respectively, on the HOLC’s

Residential Security maps. Neighborhoods whose residents were Black,

immigrants from various Eastern European or other countries, and/or

working class were rated as hazardous and coded in red. This is the

origin of the term “redlining.” The HOLC’s ratings and ideology formed

the foundation for the work of its successor agency, the Federal Housing

Administration (FHA), which adopted formal policies against insuring

loans to Black borrowers, in Black neighborhoods, or to developers who

would not agree to prohibit the sale of homes in their developments

to Black households. FHA policies, in turn, inuenced the practices of

private lenders, who also denied credit to these borrowers and in these

neighborhoods.

Map 2. The negative consequences of these government policies from

the New Deal are still being felt. As Map 2 illustrates, Black households

are still heavily concentrated in areas that were redlined on the HOLC

maps. Those neighborhoods lack many of the opportunities that

their residents desire in terms of economic opportunity and mobility,

educational opportunity and neighborhood quality.

Map 3. Those same neighborhoods were ooded with subprime loans in

the years leading up to the economic crash and experienced extremely

high rates of foreclosure. Black homeowners in Cleveland were between

2-4 times more likely to face foreclosure than their White counterparts.

Map 4. Even in post-foreclosure crisis, Cleveland’s Black neighborhoods

continue to suffer from the negative effects of housing discrimination.

A multi-city investigation into bank-owned foreclosure maintenance and

marketing found signicant racial disparities in the City of Cleveland.

Data from 2015, for example, shows that bank-owned properties in

communities of color were 6.6 times more likely to have trash or debris

on the premises as compared to those properties in predominantly White

neighborhoods. This neglect by banks in Cleveland’s Black neighborhoods

lowers property values and strips neighborhoods of wealth, continuing a

long pattern of harmful, discriminatory treatment that leaves people of

color with fewer opportunities and poorer life outcomes.

These ndings are illustrated in Map 4, with communities of color shaded

in gray and REO properties ranked by their maintenance. The red dots

indicate properties that were in extremely poor condition; the orange

dots indicate properties that were in poor condition; and the green dots

indicate properties that were in good condition.

CLEVELAND, OHIO

Source: http://www.kirwaninstitute.osu.edu/reports/2008/09_2008_OpportunityMappingOverviewReport.pdf

Source: National Fair Housing Alliance, 2015

THE CASE FOR FAIR HOUSING

THE CASE FOR FAIR

HOUSING

“Our Nation is moving toward two separate societies, one black, one white – separate and

unequal.”

34

It further found that, “Segregation and poverty have created in the racial ghetto a

destructive environment totally unknown to most white Americans. What white Americans have

never fully understood – but what the Negro can never forget – is that white society is deeply

implicated in the ghetto. White institutions created it, white institutions maintain it, and white

society condones it.”

35

The Kerner Commission made a number of recommendations to prevent further uprisings and

redress the underlying conditions that gave rise to them. Among these were the enactment

of a law to prohibit racial discrimination in housing, signicant expansion of federal support

for affordable rental housing, and redirection of federal housing programs to provide housing

choices for families of color in communities from which they had previously been barred. The

rst and last of these recommendations were embodied in the federal Fair Housing Act, passed

by Congress and signed by President Johnson on April 11, 1968, one week after the assassination

of the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. In the intervening years, there has been notable

progress in enforcing the basic nondiscrimination provisions of the Fair Housing Act, although

much more could be done to ensure effective enforcement of these protections. However, there

has been little progress over the past half-century in fullling the Act’s mandate to afrmatively

further fair housing (“AFFH” – discussed in more detail later in this report). Federal housing and

community development programs often fail to expand access for persons in protected classes

to neighborhoods of opportunity. Thus, the mandate that was intended to overcome the harms

caused by segregation and to expand housing choice still has not been fullled.

The Role of Real Estate Agents and Industry

A central player in the establishment and perpetuation of segregated cities was the real estate

industry. Many local real estate boards worked to establish restrictive covenants, while an early

incarnation of the national real estate association adopted an article in its code of ethics which

held that “a Realtor should never be instrumental in introducing into a neighborhood…members

of any race or nationality…whose presence will clearly be detrimental to property values in

that neighborhood.”

36

In a more nancially lucrative tack, many real estate agents engaged in

“blockbusting” and “panic peddling,” practices designed to scare White homeowners out of a

neighborhood with rumors and actions suggesting that the neighborhood was ripe for “racial

turnover.” The agents would then buy properties cheaply from Whites and sell them for higher

prices to incoming Blacks.

Similar policies were employed in the insurance industry, as homeowners insurance companies

adopted policies that resulted in either the outright denial of insurance in Black neighborhoods

or the availability of policies that provided only inadequate protection at excessive cost to

34 Report of the U.S. National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (Kerner Commission), p. 1.

35 Ibid.

36 Massey, Douglas S. “Origins of Economic Disparities: The Historical Role of Housing Segregation,” in James H. Carr and Nandinee K. Kutty,

eds., Segregation: The Rising Costs for America (New York: Routledge, 2008), p. 56.

24

2017 FAIR HOUSING TRENDS REPORT

THE CASE FOR FAIR

HOUSING

consumers. Given the prevalence of race-based standards in appraisals, insurance, and government

mortgage lending programs, it comes as no surprise that private banking and savings institutions

also refused to offer mortgage loans in communities of color and integrated communities.

Discrimination in the Provision of Homeowners Insurance

A companion culprit to the discriminatory actions of government and the real estate and lending

industries is the role of homeowners insurance companies. Throughout much of the twentieth

century, homeowners insurance providers maintained policies and practices that denied or limited

quality and affordable coverage on homes in Black and Latino communities. Since homeowners

insurance is required in order to qualify for a mortgage loan, these policies had a signicant impact

on homeownership for people of color. These unwarranted and discriminatory practices of

homeowners insurance providers included:

• Denying or limiting coverage on homes over a certain age;

• Denying coverage on homes under a certain minimum value; and

• The restriction of guaranteed replacement cost coverage on homes because of the difference

in market value and replacement cost.

Insurance companies argued that if they insured someone for the cost to rebuild a home and that

cost signicantly exceeded the market value of the home, it would represent a “moral hazard,”

incentivizing persons to burn down their homes. There was never any risk-based research or even

anecdotal evidence to support such a contention, and this policy had a signicant adverse effect

on communities of color as discrimination in real estate and lending markets worked in concert

to decrease the value of homes in Black and Latino neighborhoods. All these guidelines had a

tremendous effect on the ability of homeowners in middle and working class neighborhoods that

were Black, Latino or integrated to obtain quality insurance at an affordable price. That, in turn,

affected the ability to purchase homes, as homeowners insurance is required by mortgage lending

institutions.

Starting in the early 1990s, fair housing organizations at the national and local level conducted

matched pair testing and investigations of numerous major insurance companies. These investigations

documented use of the policies outlined above throughout the industry as well as differential

treatment of consumers based on their race or national origin. They also identied the improper

use of subjective criteria such as “pride of ownership” and “good housekeeping.” The investigations

documented that insurance companies had few, if any, agencies located in communities of color and

that marketing plans were designed to exclude communities of color. The testing revealed that the

agent representatives of the insurance companies tested failed to return phone calls, did not follow

through on providing quotes for insurance coverage, or offered inferior coverage at higher prices

and with fewer options for Black and Latino customers. These policies and practices served to

reinforce the redlining by lending institutions and limited the services and opportunities available

in these communities.

25

THE CASE FOR FAIR HOUSING

Based on these investigations, a number of discrimination complaints were led with the

Department of Housing and Urban Development or in federal court. The complaints alleged

that the policies outlined above had a discriminatory effect on Black and Latino neighborhoods

in metropolitan areas throughout the United States. No company was able to justify risk-

based usage of these guidelines, and many companies throughout the industry have eliminated

these guidelines and replaced any risk-based concerns with objective criteria, such as age and

condition of the roof and systems within the home. Companies also abandoned any explicitly

race- or geographically-based marketing plans. Fair housing organizations in the following cities

were involved in investigations of and cases against homeowners insurance providers: Toledo,

Cincinnati, and Akron (OH); Richmond (VA); Syracuse (NY); Atlanta (GA); Chicago (IL); Milwaukee

(WI); Memphis (TN); Hartford (CT); Los Angeles and Orange County (CA); Louisville (KY); and

Washington (DC).

The National Fair Housing Alliance and partner fair housing organizations brought the rst

cases against Allstate, Nationwide, and State Farm. State Farm, the nation’s largest insurance

provider, entered into a HUD conciliation agreement in 1996. Allstate settled shortly thereafter.

Settlements continued throughout the 1990s into the early 2000s. State Farm and Nationwide

have become strong supporters of fair housing principles and engage in company-wide efforts

to both assess their policies and practices to ensure compliance with fair housing laws and to

assess compliance by their agents on the ground. Additional companies against which cases

were brought include: Aetna, Allstate, American Family, Farmers, Liberty Mutual, Prudential, and

Travelers.

It should be noted that there has been no documentation of “moral hazard”-type arson since

companies eliminated the restrictions related to differences between the replacement cost and

market value of a property.

In the past few years, additional discrimination cases have been led against insurance companies

that do not write insurance on multifamily apartment complexes if they accept Housing Choice

Voucher holders. This practice has a discriminatory effect on persons of color, families with

children, and people with disabilities.

Discrimination and Segregation on the Basis of Disability

While this report is focused largely on segregation on the basis of color and ethnicity, we would

be remiss if we did not provide information about discrimination against and segregation of

persons with disabilities. Persons with disabilities represent nineteen percent of the population

in the United States or almost 57 million people, according to the 2010 Census.

37

Until the

passage of the Fair Housing Amendments Act in 1988 and the Americans With Disabilities Act in

1990, as well as the Supreme Court decision in Olmstead v. L.C. and E.W. in 1999, many persons

37 Americans With Disabilities, 2010, available at https://www.census.gov/prod/2012pubs/p70-131.pdf.

2

26

2017 FAIR HOUSING TRENDS REPORT

THE CASE FOR FAIR

HOUSING

with disabilities lived in segregated, and often institutional, settings and did not have access to

many communities or to public facilities and services. Since then, people with disabilities have

increasingly had access to or have been integrated into neighborhoods, employment, public

services, and other key components of life; however, discrimination and lack of accessibility

continue to limit the housing choice and opportunities of those with disabilities.

In the early 2000s, housing discrimination complaints on the basis of disability became the

greatest percentage of all complaints led in the U.S. Since then, disability complaints have

made up the largest percentage of housing discrimination complaints received by both public

and private fair housing enforcement organizations. There are many reasons for this: HUD

has provided signicant funding focused on educating persons with disabilities about their fair

housing rights; persons with disabilities represent a signicant part of the population as noted

above and this population is increasing as the baby boom generation ages; there is a signicant

amount of discrimination based on disability; and discrimination on the basis of disability is, for

the most part, easier to detect than other types of discrimination. Many apartment owners

make overt discriminatory comments or refuse outright to make reasonable accommodations

or modications for people with disabilities, as required under the Fair Housing Act. Despite

signicant investment in training and guidance for architects, builders, and developers, large

numbers of multifamily properties continue to be constructed that do not meet the design

and construction requirements under the Fair Housing Act that serve to make more housing

opportunities accessible to persons with disabilities.

Examples of accessibility barriers include the absence of curb cuts and handicap accessible parking

spaces with adjacent access aisles, inaccessible kitchens and bathrooms, narrow door widths and

passageways, insurmountable thresholds and inaccessible switches, outlets and environmental

controls within units and throughout common use areas. Some builders have steps down to a

living room or up to a bedroom. Failure to provide accessible housing or to grant requests for

reasonable modications and accommodations prevents persons with disabilities from having

access to all communities and the opportunities those communities provide.

Many private fair housing organizations and the Department of Justice have brought legal action

against developers and owners of properties that did not meet the requirements of the Fair

Housing Act. NFHA has brought several cases (some of which are currently ongoing), including

two key cases that affected a signicant number of properties and represent the issues that

prevent persons with disabilities from obtaining access to all communities.

Ovation Development Corporation – Las Vegas, NV

On August 7, 2007, NFHA led a housing discrimination lawsuit against Ovation Development

Corporation, a builder and property manager of multifamily rental apartments in the Las Vegas

area, and several of its afliated entities. In the lawsuit, NFHA alleged that Ovation discriminated

against people with disabilities by improperly building units that failed to comply with federal

accessibility standards in their design and construction. The lawsuit was led in the United

27

THE CASE FOR FAIR HOUSING

District Court for the District of Nevada.

The lawsuit was based on an investigation of 11 apartment complexes located in Las Vegas and

Henderson, Nevada. Together, the 11 complexes comprised 1,518 ground oor units and 368

buildings. All 11 properties failed to meet the accessibility requirements of the Fair Housing Act.

In addition, many of the properties also had violations of the accessibility requirements of the

Americans with Disabilities Act.

In 2001 and 2005, the U.S. Department of Justice led two suits against Pacic Properties

and Development Corporation, whose principal is the founder of Ovation. The suit alleged

inaccessible features at four multi-family housing complexes built by Pacic Properties. In

settlement, the founder of Ovation, in his capacity as an ofcer of Pacic Properties, was placed

under a continuing order of the court that prohibited him from participating in the design and/

or building of covered multifamily housing without the accessible features mandated by the Fair

Housing Act.

A.G. Spanos Companies – Stockton, CA

On June 21, 2007, NFHA and four of its members led a housing discrimination lawsuit against A.G.

Spanos Companies, a builder and developer of multifamily housing and commercial properties

in at least 16 states. The lawsuit alleged that Spanos failed to comply with federal accessibility

standards in the design and construction of its properties. NFHA and its members—Fair

Housing of Marin, Fair Housing Napa Valley, Metro Fair Housing Services, and the Fair Housing

Continuum—investigated 35 apartment complexes in California, Arizona, Nevada, Texas, Kansas,

Georgia, and Florida. All of these complexes failed to meet the accessibility requirements of the

Fair Housing Act and the Americans with Disabilities Act. These 35 properties, totaling more than

10,000 individual apartment dwelling units, represent only a sample of the at least 82 Spanos

properties in existence at that time that were covered by the federal Fair Housing Act.

In 2010, NFHA and its partners announced a landmark agreement with the A.G. Spanos Companies

to increase housing accessibility for people with disabilities. Under the agreement, Spanos agreed

to retrot properties in Arizona, California, Colorado, Georgia, Florida, Kansas, Missouri, Nevada,

New York, North Carolina, and Texas at an estimated cost of $7.4 million.

The agreement initiated a productive partnership between the Spanos Companies, NFHA, and its

member fair housing agencies to make apartments accessible to individuals who use wheelchairs

and people with limited mobility. It covered 123 properties built since March 1991. The agreement

also established a $4.2 million national fund to provide grants to people with disabilities across

the country. The Spanos Companies became a partner and supporter of NFHA and its member

organizations.

We must continue our efforts to ensure that persons with disabilities are not denied housing

opportunities based on overt discrimination and the failure to construct accessible housing.

2

28

2017 FAIR HOUSING TRENDS REPORT

THE CASE FOR FAIR

HOUSING

The Engines of Residential Segregation Today

Regrettably, the engines of housing segregation are not mere relics of U.S. history. The housing

market continues to operate in powerful and evolving ways that reinforce entrenched patterns

of segregation and inequity. The recent foreclosure crisis, which peaked from 2005-2009, served

to signicantly deepen the U.S. wealth gap along racial lines, erasing incremental advances made