Rethinking

Property Tax Incentives

for Business

Policy Focus Report • Lincoln Institute of Land Policy

Daphne a. Kenyon, aDam h. LangLey, anD Bethany p. paquin

Rethinking Property Tax Incentives for Business

Daphne A. Kenyon, Adam H. Langley, and Bethany P. Paquin

Policy Focus Report Series

The policy focus report series is published by the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy to address

timely public policy issues relating to land use, land markets, and property taxation. Each report

is designed to bridge the gap between theory and practice by combining research ndings, case

studies, and contributions from scholars in a variety of academic disciplines and from profes-

sional practitioners, local ofcials, and citizens in diverse communities.

About This Report

State and local governments across the United States use several types of property tax

incentives for business, including property tax abatement programs, rm-specic property tax

incentives, tax increment nancing, enterprise zones, and industrial development bonds com-

bined with property tax exemptions. The escalating use of property tax incentives over the last

50 years has resulted in local governments spending billions of dollars with little evidence of

economic benets.

This report provides an overview of use of property tax incentives for business and offers

several recommendations. State and local governments should consider forgoing these often

wasteful incentive programs in favor of other, more cost-effective policies, such as customized

job training, labor market intermediaries, and the provision of business services. If ending

property tax incentives is not feasible, state governments should consider a range of policy

options, such as placing limits on their use, requiring approval by all affected governments,

improving transparency and accountability, and ending state reimbursement for local property

taxes forgone because of incentives. Local governments can avoid some of the pitfalls of busi-

ness property tax incentives by setting objective criteria for the types of projects eligible for

incentives, targeting incentives to mobile rms that export goods or services out of the region,

limiting total spending on incentives, opening the process for decision making on incentives,

and forging regional cooperative agreements.

Copyright © 2012 by Lincoln Institute of Land Policy

All rights reserved.

113 Brattle Street

Cambridge, MA 02138-3400 USA

Phone: 617-661-3016 or 800-526-3873

Fax: 617-661-7235 or 800-526-3944

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.lincolninst.edu

ISBN 978-1-55844-233-7

Policy Focus Report/Code PF030

Kenyon, LangLey & Paquin � Rethinking PRoPeRty tax incentives 1

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Contents

2 Executive Summary

4 Chapter 1: Overview of Property

Tax Incentives for Business

5 Increased Use of Property

Tax Incentives

7 Economic Development Goals

10 Obstacles to Achieving Development

Goals

12 Pitfalls with Discretionary Property

Tax Incentives

13 Chapter 2: Property Taxes on Business

13 Why Businesses Pay Property Taxes

15 Policies Affecting the Property Tax

Burden on Business

19 Effective Tax Rates on Business

Property

21 Summary

22 Chapter 3: The Impact of Property

Taxes on Firm Location Decisions

22 The Site Location Process

23 The Effect of Input Cost Differences

24 Economic Theory

26 Empirical Evidence

29 Summary

30 Chapter 4: Types of Property Tax

Incentives for Business

30 Property Tax Abatement Programs

33 Firm-Specic Property Tax Incentives

34 Tax Increment Financing

38 Enterprise Zones

41 Industrial Development Bonds

Combined with Property Tax

Exemption

44 Widespread Use of Incentives

44 Summary

45 Chapter 5: Tools for Assessing

the Effectiveness of Property

Tax Incentives

46 Transparency

46 Impact of Incentives on Firm

Location Decisions

49 Benet-Cost Framework for

Evaluating Incentives

51 Economic and Fiscal Impact

Analyses

51 Summary

52 Chapter 6: Policies to Reduce

Reliance on Property Tax Incentives

52 Reduction of Interlocal Competition

53 Tax Reform

55 Nontax Alternatives

57 Summary

58 Chapter 7: Findings and

Recommendations

59 Alternatives to Incentives

59 State Options for Reforming

Tax Incentives

60 Local Options for Reforming

Tax Incentives

62 References

66 Appendix Tables

74 Appendix Notes

75 Acknowledgments

76 About the Authors

76 About the Lincoln Institute

of Land Policy

2 Policy focus RePoRt � LincoLn institute of Land PoLicy

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Executive Summary

1 percent of total costs for the U.S. manu-

facturing sector. Second, tax breaks are

sometimes given to businesses that would

have chosen the same location even without

the incentives. When this happens, property

tax incentives merely deplete the tax base

without promoting economic development.

Third, widespread use of incentives within

a metropolitan area reduces their effective-

ness, because when firms can obtain similar

tax breaks in most jurisdictions, incentives

are less likely to affect business location

decisions.

This report reviews five types of property

tax incentives and examines their character-

istics, costs, and effectiveness.

T

he use of property tax incentives

for business by local governments

throughout the United States has

escalated over the last 50 years.

While there is little evidence that these

tax incentives are an effective instrument

to promote economic development, they

cost state and local governments $5 to

$10 billion each year in forgone revenue.

Three major obstacles can impede the

success of property tax incentives as an eco-

nomic development tool. First, incentives

are unlikely to have a significant impact

on a firm’s profitability since property taxes

are a small part of the total costs for most

businesses—averaging much less than

Kenyon, LangLey & Paquin � Rethinking PRoPeRty tax incentives 3

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

• Thebestevidenceonpropertytaxabate-

ment programs indicates they are effective

initially for the first jurisdictions that use such

incentives, but once they proliferate across a

metropolitan area they no longer promote

economic growth.

• Evidenceontheimpactof taxincrement

finance on economic activity is more mixed,

but this mechanism may be overused and

finance less beneficial projects when one local

government is able to divert revenue from

another local government without its approv-

al, such as a city diverting a school district’s

revenue.

• Enterprisezones,whichtypicallyinclude

property tax incentives as part of a larger

incentive package and are usually targeted

to distressed areas, have limited effectiveness.

• Verylittleinformationisavailableregarding

either firm-specific property tax incentives or

property tax exemptions in connection with

issuance of industrial development bonds.

Despite a generally poor record in promoting

economic development, incentives can be help-

ful in some cases. When these incentives attract

new businesses to a jurisdiction they can in-

crease income or employment, expand the tax

base,andrevitalizedistressedurbanareas.Ina

best case scenario, attracting a large facility can

increase worker productivity and draw related

firms to the area, creating a positive feedback

loop. This report offers recommendations to

improve the odds of achieving these economic

development goals.

Alternatives to tax incentives should be

considered by policy makers seeking more cost-

effectiveapproaches,suchascustomizedjob

training, labor market intermediaries, and busi-

ness support services. State and local govern-

ments also can pursue a policy of broad-based

taxes with low tax rates or adopt split-rate prop-

erty taxation with lower taxes on buildings than

land.

State policy makers are in a good position

to increase the effectiveness of property tax in-

centives since they control how local govern-

ments use them. For example, states can restrict

the use of incentives to certain geographic areas

or certain types of facilities; publish information

on the use of property tax incentives; conduct

studies on their effectiveness; and reduce de-

structive local tax competition by not reimburs-

ing local governments for revenue they forgo

when they award property tax incentives.

Local government officials can make

wiser use of property tax incentives for business

and avoid such incentives when their costs ex-

ceed their benefits. Localities should set clear

criteria for the types of projects eligible for in-

centives; limit tax breaks to mobile facilities that

export goods or services out of the region; in-

volve tax administrators and other stakeholders

in decisions to grant incentives; cooperate on

economic development with other jurisdictions

in the area; and be clear from the outset that

not all businesses that ask for an incentive will

receive one.

4 Policy focus RePoRt � LincoLn institute of Land PoLicy

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

CHAPTER 1

Overview of Property Tax Incentives

for Business

T

he United States is emerging from

the worst economic downturn since

the Great Depression. The country

must create jobs to tackle a major

unemployment problem, while also address-

ing significant fiscal challenges at all levels

of government. Many local governments

have attempted to deal with these dual

challenges by using property tax incentives

for business, hoping they can spur economic

development and expand their tax base.

But whether tax breaks can achieve

these goals or not is an open question at best.

Some leaders believe that incentives can

be an effective tie-breaker that governments

can use to tip business location decisions

in their favor. For example, the vice president

of marketing for the Chattanooga Area

Chamber of Commerce argues:

Businesses look at a lot of factors in

deciding where to locate. But if they think

they can get the labor, transportation,

and their other needs in more than one

community, then they are going to look

at the incentives to decide where to go.

(Chattanooga Times Free Press 2010)

Yet many economists and policy analysts

who have studied tax incentives argue that

Kenyon, LangLey & Paquin � Rethinking PRoPeRty tax incentives 5

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Figure 1.1

Increasing Use of Property Tax Incentives

they are often given to firms that would

have chosen the same location regardless of

tax breaks, in which case they are a costly

tool with no significant effect on economic

development.

Tax incentives have the potential to

achieve a variety of economic development

goals, but overuse and poorly designed pro-

grams can leave localities with smaller tax

bases and no improvement in their local

economies. The dramatic growth in their

use over the past 30 to 40 years and the long-

term fiscal challenges facing many state and

local governments suggest that policy makers

need to rethink how they are using incentives.

This report offers recommendations for

howtoincreasetheoddsof realizingdevel-

opment goals with property tax incentives

whileminimizingthecommonpitfalls.

INCREASED USE OF

PROPERTY TAX INCENTIVES

Like many other economic development

tools, the use of property tax incentives has

grown dramatically in recent decades, with

the most rapid growth occurring in the

1970s and 1980s (figure 1.1). There are

several reasons for this growth. At the root

is the increased mobility of business over

recent decades. Transportation and com-

munications costs have declined dramati-

cally, supply chain management has im-

proved, and previously closed economies

have opened up in Asia and other areas.

As a result, firms are more sensitive to costs

that vary by location, such as labor and taxes,

and increased competition means that busi-

nesses ignoring these cost differences may

risk bankruptcy (Davidson 2012). With

greater mobility, the potential for incentives

to alter firm location decisions has grown.

Competition to attract a smaller number

of industrial facilities has placed pressure

on state and local government officials to use

all the tools at their disposal, including prop-

erty tax incentives. Figure 1.2 shows that

over the past three decades, the value of U.S.

manufacturing output has been stagnant,

growing only 4 percent since its 1978 peak

compared to 89 percent growth for the econ-

omy as a whole. Manufacturing employment

has declined 41 percent over this period.

15

8

1

31

24

22

33

38

37

35

40

42

37

49

0

10

20

30

40

50

Property Tax Abatements Tax Increment Financing Enterprise Zones

Number of States Allowing Incentives

’64

’79 ’91 ’05 ’10

’70 ’80 ’90

’00 ’10 ’81

’85 ’90

’10

Note: Property tax abatements are stand-alone programs that are not part of broader economic development programs.

Sources: Appendix Tables A.1, A.2, and A.3; Kerth and Baxandall (2011); U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development

(1991); Wassmer (2009, 223–224).

6 Policy focus RePoRt � LincoLn institute of Land PoLicy

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Central cities have borne the negative

effects of these economic changes most

heavily, which has led some states to adopt

enterprisezones,taxincrementnancing,

and other types of geographically targeted

incentives meant to help distressed areas.

Among the 100 largest cities in 1960, 44

had lower populations by 2010, which is

particularly striking since over this period

the U.S. population grew 72 percent and

many central cities annexed large amounts

of land (Gibson 1998; U.S. Census Bureau

2012).Incontrast,thepercentageof Amer-

icans living in the suburbs grew steadily

from 15 percent in 1940 to 45 percent in

1980, and reached 50 percent in 2000

(Hobbs and Stoops 2002).

Tax incentives are politically appealing

to local officials. Because their cost is less

transparent and they are not subject to an-

nual appropriations, tax expenditures can

be more attractive than direct expenditures

on economic development, even if the effect

on tax rates and the ability to fund other

services is similar. Policy makers also may

Figure 1.2

Activity in the U.S. Manufacturing Sector, 1950–2010

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (2006; 2011).

10

12

14

16

18

20

22

600

800

1,000

1,200

1,400

1,600

1,800

2,000

1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010

Employment (millions)

Real Value Added ($2010, billions)

Value Added Employment

argue that they are not really forgoing tax

revenues because without the incentives the

firm would have located elsewhere and thus

paid no taxes to the jurisdiction. However,

this is not always the case (box 1.1). Since

attracting large facilities is a highly visible

sign of success, local officials may face

considerable pressure to offer incentives.

A self-perpetuating cycle can also drive

up the use of tax incentives over time. Their

use in one locality puts pressure on neighbor-

ing jurisdictions to offer incentives as well.

Localities may feel they have no choice but

to offer incentives if tax breaks are actively

used in surrounding jurisdictions; instead

of using incentives to gain an advantage to

attract firms, they are used just to remain

on a level playing field with their neighbors.

Some evidence also indicates that once

a municipality starts using property tax in-

centives it is unlikely to stop offering them

(Sands and Reese 2012). Offering tax breaks

to one firm makes it more likely that other

firms considering locating or expanding in

that jurisdiction will also lobby for incen-

Kenyon, LangLey & Paquin � Rethinking PRoPeRty tax incentives 7

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

tives. This self-perpetuating cycle means

that tax incentives can move from being the

exception to the norm, and will be expected

by all firms rather than serve as a targeted

tax break.

ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

GOALS

Local governments use property tax incen-

tives to pursue a variety of economic devel-

opment goals. Policy makers must set clear

goals, think hard about the methods by

which tax incentives can help achieve those

goals, and consider obstacles that could

prevent success (table 1.1).

Increase Income or Employment

Business facilities that export goods or ser-

vices to national or international markets

provide an important economic base for a

local government or metropolitan area.

These facilities include manufacturing

plants, corporate headquarters, R&D cen-

ters, warehouses, back-office support, and

services for people living outside the region,

such as finance and insurance.

Such firms increase an area’s aggregate

income in direct and indirect ways. The

Box 1.1

Do Tax Incentives Really Tip Firm Location Decisions?

P

erhaps the greatest dilemma for policy makers considering in-

centives is the limited information about the true importance of

property taxes in an individual rm’s location decision. Firms consider

dozens of factors during site selection, but government ofcials rarely

know which factors are most important. They may feel compelled to

offer tax incentives since it is one of the few location factors they

can inuence directly.

Policy makers may think that tax cuts and incentive offers are decisive,

but this assumption is often wrong. When businesses lobby for tax

breaks, they have a clear motive to exaggerate the importance of in-

centives, because otherwise they are unlikely to receive any breaks.

In fact, evidence shows that in some cases businesses negotiate

for tax incentives after they have already chosen a location (Fisher

2007, 65).

TaBle 1.1

Property Tax Incentives and Economic Development Goals

Goal Goal May be Reached if Incentives: Goal May Not be Reached if Incentives:

Increase

Income or

Employment

• Attractfacilitiesthatexportgoodsorservicesout

of the area

• Promoteindustryclustersthatincrease

productivity in the area

• Havelittleimpactbecausepropertytaxesaccountfor

a small share of total business costs

• Createjobsthatlargelygotoin-migrantsorcommuters

• Createjobsthatarelow-wageorpart-time

• Requiregovernmenttoeffectively“pickwinners”

Improve

Fiscal Health

• Obtainpartialpropertytaxesfromrmsthatwould

have located elsewhere without tax breaks

• Attractsupplierspayingfulltaxesbyprovidingtax

breaks for anchor rms

• Obtainothertaxesorfeesfromthermthat

offset forgone property taxes

• Aregiventormsthatwouldchoosethesame

location even without tax breaks

• Aregiventofacilitiesthatrequirecostlyinfrastructure

investments by the jurisdiction

• Extendforalongertimeperiodthanthelifespan

of recipient plants

Promote

Urban

Revitalization

• Redirectbusinessinvestmentwithinametroarea

to distressed areas

• Offsetlowerbusinesscostsinwealthierareas

• Havelittleimpactonrelativetaxburdensdue

to widespread use of tax breaks

• Areutilizedaggressivelybywealthyareas

• Requireverylargetaxbreaksperjobcreated

to attract investment to distressed areas

firm spends money directly on its payroll,

inputs from local suppliers, and services

from local businesses. The indirect effects

occur when these workers and companies

then spend a large share of their incomes

on locally provided goods and services, and

those firms and their workers in turn spend

this money at other local establishments.

This chain of events is often measured by

8 Policy focus RePoRt � LincoLn institute of Land PoLicy

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

a multiplier, which is the ratio of the total

increase in income, employment, or output

across the local economy divided by the

initial direct increase (Morgan 2010).

Using tax incentives to attract these types

of facilities may increase a locality’s per capita

income and employment rate, although the

latter effect is less likely given the high rate

of U.S. labor mobility. Conversely, provid-

ing tax incentives for retail establishments,

housing developments, and other businesses

serving the local population is extremely

unlikely to increase income or employment.

The local population can only support so

many of these businesses, and expansion

by one firm will likely displace sales for

competitors.

Inaddition,attractingalargefacility

may increase the productivity of other firms

in the area and the wages of their workers.

Aninitialclusterof rmsspecializedinone

industry can create a positive feedback loop:

workers with industry-specific skills will

move to the area, which will increase the

number of other similar firms in the area,

and in turn the concentration of firms

supplying inputs. Meanwhile, the sharing

of knowledge among workers and firms

will increase productivity and the rate of

innovation, leading to increased wages for

workers in the industry, which will draw more

skilled employees, firms, and suppliers.

Greenstone, Hornbeck, and Moretti

(2010) provide evidence of how attracting

one large facility can generate these types

of productivity spillovers, sometimes known

as agglomeration economies. For 47 large

manufacturing plant openings, the authors

compare economic trends for the “winner”

county and one or two “loser” counties that

were runner-ups. Before the plant openings,

winning and losing counties had similar

trends in productivity and other economic

variables. Five years after the opening, pro-

ductivity at existing plants in the winning

counties had grown 12 percent more than

Kenyon, LangLey & Paquin � Rethinking PRoPeRty tax incentives 9

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

in the losing counties, and wage growth was

also significantly higher. Although this study

did not have data on incentive offers, if they

had played a decisive role in attracting large

plants then these spillover effects on produc-

tivity and wages could justify the cost of

the incentives.

Improve Fiscal Health

A common goal for individual municipalities

and counties using property tax incentives

is to improve fiscal health, which occurs if

revenue growth attributable to incentives

exceeds growth in public service costs

related to the business expansion.

If thermtrulywouldnothavechosen

the locality without the incentive, then local

officials can conclude that some property

tax revenue is better than none. This con-

clusion makes sense if the firm pays partial

property taxes on the facility, or if the firm

will pay full taxes in the future once a time-

limitedincentiveexpires.Intheory,ajuris-

dictioncanmaximizerevenuebynegotiating

taxes down to the level at which the firm

just slightly prefers that location to alterna-

tive sites, and maintain its fiscal health by

lowering taxes to the point at which they

equal the cost of providing public services

to the firm (Glaeser 2001).

Offering incentives for one firm could

also boost tax revenues if that facility attracts

other suppliers who would pay full taxes,

or if it increases the property tax base in

other ways. Greenstone and Moretti (2004)

found that attracting a large facility increased

property values in winning counties by 6.6

to 10.2 percent relative to runner-up coun-

ties over the course of six years.

Other taxes or fees paid by a firm could

also offset revenue losses from property tax

incentives.Inparticular,whileincentivizing

retail facilities may be unnecessary if they

are tied to specific sites with high market

exposure, attracting large retail stores can

substantially increase sales tax revenues for

the locality, which is especially important

in states with property tax limits.

However, for counties, municipalities,

and towns combined, property taxes raise

about 2.5 times more revenue than sales

taxes.In2007,propertytaxesaccounted

for 36.9 percent of own-source revenues

for these local governments, while sales

taxes accounted for 14.3 percent. Sales taxes

exceeded property taxes in only ten states

(State and Local Government Finance

Data Query System 2012).

Promote Urban Revitalization

Redirecting business investment within a

metropolitan region to areas with high un-

employment or declining populations is a

justifiable policy goal. Areas with declining

populationstendtohaveunderutilizedin-

frastructure, so business investment in these

areas is less likely to require costly new in-

frastructure to provide services for a new

facility than areas with growing populations.

Inaddition,thesocialbenetsfromnew

jobs may be greater in these areas, because

a larger proportion of people without jobs

has been involuntarily unemployed for

long periods of time (Bartik 2005); workers

with prolonged periods of unemployment

suffer from an erosion of job skills that

hurts long-term earnings (Bartik 2010);

and inner-city residents may have difficulty

obtaining jobs in wealthier suburbs due

to limited knowledge about opportunities,

difficulties commuting, or discrimination

(Anderson and Wassmer 2000).

As described in chapter 3, property tax

incentives are much more likely to sway a

firm’s choice of a specific site within a given

metropolitan area than to alter its broader

choicebetweendifferentregions.If incen-

tives are offered primarily in poorer areas

and center cities, they can help offset the

fact that the costs of business may be higher

10 Policy focus RePoRt � LincoLn institute of Land PoLicy

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

in these areas for a variety of reasons, in-

cluding higher property taxes, lower quality

public services, higher crime or land prices,

andtheneedtoredevelopbrownelds.In-

centives can be considered a compensating

differential to make these areas more com-

petitive with suburban areas that would

otherwise be more profitable locations for

many new facilities.

OBSTACLES TO ACHIEVING

DEVELOPMENT GOALS

Achieving these economic development

goals with property tax incentives depends

on a wide range of factors and is far from

guaranteed (box 1.2). Three general obsta-

cles apply to all three goals: property taxes

are a small part of total costs for most firms;

tax breaks are sometimes given to businesses

that would have chosen the same location

even without incentives; and widespread

use of incentives reduces their effectiveness.

Specific obstacles relate to the goal of

increasing income or employment with tax

incentives. First, most new jobs created by

business investment will go to in-migrants

or commuters instead of existing residents,

because people move to areas with strong

economic growth. For example, an analysis

of 18 studies by Bartik (1993) found that

between 60 and 90 percent of jobs created

by employment programs go to in-migrants

or unintended beneficiaries, while a study

byBlanchardandKatz(1992)suggeststhat

in the long run all newly created jobs will

be taken by in-migrants.

Incomegrowthorpovertyreduction

may be more realistic goals than increasing

the employment rate, but these benefits

depend on the characteristics of new jobs,

such as the wage level and percent of full-

time workers. Relying on selective incen-

tives to improve the economy requires local

governments to pick winners by strategic-

ally offering incentives and identifying key

firms and local sectors that can sustain

competitiveness.

Achieving the goal of improved fiscal

health by offering tax incentives also depends

on several factors. Most important is the cost

of new infrastructure and expanded public

services, which depends on the current use

of existing infrastructure. Because of these

costs, projects that require new infrastructure

are unlikely to improve fiscal health in the

shortrun(AltshulerandGómez-Ibáñez

1993)

Another issue is that expecting a firm to

pay full taxes in the future once an incentive

has expired is often unrealistic. Based on

several studies, Fisher (2007) has estimated

that the median manufacturing plant is

open for approximately 8 to10 years. Since

the duration for property tax abatements

exceeds 10 years in about two-thirds of pro-

grams (Dalehite, Mikesell, and Zorn 2005),

a majority of facilities may have closed

Kenyon, LangLey & Paquin � Rethinking PRoPeRty tax incentives 11

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Box 1.2

A Cautionary Tale in Michigan

I

n 2009, the State of Michigan offered

over 35 business tax incentive pro-

grams (Anderson, Rosaen, and Doe 2009).

The most expansive of these is the In-

dustrial Facilities Property Tax Abatement

program (Act 198). Crafted in 1974, Act

198 provides geographically targeted

property tax abatements for the creation,

expansion, renovation, or addition of in-

dustrial property (Sands and Reese

2012; CRC 2007). Practically any local

government may establish an industrial

development or plant rehabilitation dis-

trict. Once a district is established, any

qualifying business wishing to develop

within the district can apply for an ex-

emption certicate subject to local and

state approval and conditional upon job

retention and creation. Instead of pay-

ing property taxes, certied businesses pay a substitute

tax equal to 50 percent of the property tax for new facilities

and equal to the property tax on the unimproved value of

renovations or rehabilitations (Mikesell and Dalehite 2002;

Signicant Features of the Property Tax 2012).

Sands and Reese (2012) report that between 1974 and

2005 the program abated $77.4 billion in real and person-

al property, with an average of 600 exemption certicates is-

sued each year since 1980. The cost to local governments

in lost revenue between 1990 and 2005 was roughly $84

per person per year. In 2008, industrial property abated

by this program accounted for 20.5 percent of the total

industrial tax base (Anderson, Bolema, and Rosaen 2010).

Despite their widespread use, the impact of the Act 198

abatements is unclear. Over the 1990–2005 period, busi-

nesses receiving abatements reported they would create

234,000 new manufacturing jobs and retain 728,000

manufacturing jobs that otherwise would have been lost.

Yet the number of jobs reported is not the same as the

number of jobs actually attributable to the abatements,

because the promised jobs do not always materialize and

many that do would have been created even without the

abatements. In fact, in some industries the number of jobs

reportedly created or retained through abatements actually

exceeds the total number of all jobs in those industries.

More generally, Michigan lost a slightly higher percentage

of manufacturing jobs than the country as a whole over

the time period. Although manufacturing job losses may

have been even greater in the absence of abatements, the

abatements were not effective in preventing substantial

job losses (Sands and Reese 2012).

Evidence shows the abatements have not effectively tar-

geted incentives to distressed areas or central cities. Among

communities that awarded abatements between 1998

and 2000, distressed areas were no more likely to award

them than ourishing communities, but spent more per

job retained or created than wealthier areas. Furthermore,

suburbs award abatements at a higher rate per capita than

central cities. The suburbs report more jobs per capita as

a result of incentives and had higher investment per capita.

Abatements may promote sprawl to the extent that new

investment spurred by the abatements is more likely to

occur outside of central cities (Reese and Sands 2006).

12 Policy focus RePoRt � LincoLn institute of Land PoLicy

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

before they ever paid the full tax rate. For

these reasons, some studies have found that

greater reliance on property tax incentives

increases fiscal stress for local governments

(Mullen 1990).

Finally,promotingurbanrevitalization

with property tax incentives depends on

theirgreaterutilizationindistressedareas

than wealthier communities; if both types

of areas use incentives aggressively, then

relative tax burdens may change little. How-

ever, in practice, economic development in-

centives do not appear to be notably more

common in low-income areas (Peters and

Fisher 2004). There is also evidence that

tax incentives are more cost effective in areas

with high incomes and low unemployment,

and thus their use could actually widen

economic disparities between high- and

low-income areas (Goss and Phillips 2001;

Sands and Reese 2012). While the social

benefits of creating jobs with tax incentives

may be greater in areas with high unemploy-

ment, the costs could be even greater if

it takes substantially larger tax breaks to

induce business investment in these areas.

PITFALLS WITH

DISCRETIONARY PROPERTY

TAX INCENTIVES

Discretionary tax incentives, which are dis-

tinct from as-of-right incentives given to all

firms meeting certain criteria, have other

pitfalls. Selective use of incentives raises

majorconcernsabouthorizontalequityand

the distribution of taxes, because granting

tax breaks to some mobile businesses likely

means that long-standing local businesses

or homeowners will pay more. This type

of system is likely to be viewed as unfair

by many taxpayers.

Decisions to grant discretionary tax

incentives are sometimes not transparent

or are made in ad hoc ways without clear

economic justification. This process may

be unduly influenced by political consider-

ations, with incentives granted to well-

connected firms or campaign contributors.

For example, Felix and Hines (2010) found

that communities in states with more cor-

rupt political cultures were more likely

to offer incentives.

A related concern is that politicians may

grant incentives regardless of the economic

rationale. Politicians can grant incentives

and claim that they played an instrumental

role in attracting a new facility to the com-

munity, even if a firm may have located

there without incentives. Wolman and

Spitzley(1996)ndevidenceof thistype

of credit-claiming among elected officials.

Conversely, if politicians decide not to

offer incentives, they could be blamed if

the firm chooses to locate elsewhere. A final

consideration is that negotiation over tax

incentives significantly increases the cost

of property tax administration for the local

government.Itisalsoeconomicallyinef-

cient for firms to spend time and money

lobbying for tax breaks instead of focus-

ing on improving their business.

Kenyon, LangLey & Paquin � Rethinking PRoPeRty tax incentives 13

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

CHAPTER 2

Property Taxes on Business

B

usiness property includes nonresi-

dential, income-producing prop-

erty such as commercial, industrial,

farm, mineral, railroad, or public

utility properties (Cornia 1995). This report

focuses primarily on commercial and indus-

trial property.

WHY BUSINESSES PAY

PROPERTY TAXES

Inordertoputpropertytaxincentivesinthe

proper context, it is important to consider

the reasons for requiring businesses to pay

property taxes.

To fund services received. State and

local governments provide a wide array of

services that benefit business activity, in-

cluding a small proportion that directly and

solely benefit businesses, such as economic

development support. Other types of state

and local government expenditures, such

as on the court system, transportation, and

public safety, provide critical benefits for

bothbusinessesandhouseholds.Education

is the single largest expenditure of state and

local government. Although education pro-

vides direct benefits to individuals, it also

benefits businesses by increasing the pro-

ductivity of their employees.

Oakland and Testa (1996) examine several

rationales for state and local taxation of busi-

ness, concluding that the primary basis for

14 Policy focus RePoRt � LincoLn institute of Land PoLicy

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

taxing businesses is to recover the cost of

government services provided to them. The

authors further argue that taxing businesses

in accordance with benefits provided is

both fair and efficient.

To generate revenue for local gov-

ernments. Although popular discussion of

property taxes tends to focus on those paid

by homeowners, the assessed value of busi-

ness property is an important part of the

taxbase.In1986,themostrecentyearthat

the U.S. Census collected data on assessed

property values, 39 percent of the property

tax base could be attributed to businesses.

This included commercial properties (16

percent), industrial properties (6 percent),

farms (7 percent), and personal property

(10 percent). The latter can be classified as

business property since most states no longer

tax household personal property. Residential

property accounted for 55 percent of the

tax base, split between single-family houses

(48 percent) and multifamily properties

(7percent).Vacantlotsaccountedforthe

remaining 6 percent (U.S. Department

of Commerce 1989).

More recent data can be obtained

at the state level, but not all states report

assessed values by property type, and the

states that do report may not divide the

property tax base into the same categories.

Thirty-one states report some division of

their property tax base by property type

(table 2.1). For these states on average,

nearly 60 percent of the property tax base

was residential, 22 percent was commer-

cial and/or industrial, and 19 percent was

categorizedas“other,”whichincluded

various types, such as personal property

and vacant land.

Revenue from business property taxes

also constitutes a substantial proportion of

all property tax revenue collected. Accord-

ing to Phillips et al. (2011), in FY2009 busi-

nesses contributed $247 billion in property

TaBle 2.1

Property Tax Base by Property Type in 31 States, 2009

State Residential

Commercial

and/or Industrial Other

U.S. Average 59.8% 21.6% 18.6%

Alaska 59.7 22.4 17.9

Colorado 46.2 25.7 28.1

Delaware 71.0 29.0 0.0

District of Columbia 58.4 40.9 0.7

Florida 74.2 17.1 8.8

Hawaii 68.6 24.8 6.7

Idaho 69.7 22.7 7.5

Illinois 65.0 32.5 2.5

Indiana 49.3 29.0 21.7

Iowa 44.5 30.2 25.3

Kansas 51.9 25.8 22.3

Kentucky 65.8 24.3 9.9

Maryland 80.2 18.0 1.8

Massachusetts 83.0 14.5 2.5

Michigan 69.4 20.1 10.5

Minnesota 66.9 13.3 19.8

Missouri 53.7 21.4 24.9

Montana 47.1 13.6 39.3

New Hampshire 79.6 16.3 4.1

New Jersey 62.5 15.2 22.3

North Carolina 65.0 15.8 19.2

North Dakota 43.3 23.3 33.5

Ohio 69.3 20.8 10.0

Oregon 52.5 19.0 28.5

South Dakota 39.2 24.1 36.6

Tennessee 55.5 27.1 17.4

Texas 52.3 20.3 27.4

Utah 47.2 19.4 33.4

Vermont 60.9 16.5 22.6

Washington 75.4 16.6 8.0

Wisconsin 72.1 20.3 7.6

Wyoming 15.2 10.5 74.3

Notes: The other 19 states do not report divisions of their tax base into classes for residential

andcommercialand/orindustrialproperties.States’denitionsof“other”propertyvarywidely.

Source: Signicant Features of the Property Tax (2012).

Kenyon, LangLey & Paquin � Rethinking PRoPeRty tax incentives 15

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

tax revenue to state and local governments,

constituting 58 percent of all property taxes

raised and 40 percent of all state and local

taxes paid by business (figure 2.1). These

estimates include multifamily housing,

although many other researchers would

not include it as business property. Business

property taxes have been quite stable over

the past two decades, although they did

jumpsignicantlyin2009and2010.It

is likely that business properties will help

shore up total property tax revenues in

coming years, as the dramatic fall in hous-

ing values weighs down residential tax

payments.

To add progressivity to the state-

local tax system. For those concerned

with state and local government use of

regressive taxes, such as reliance on the

general sales tax, levying property taxes on

businesses can be a way to add a progres-

sive element to the total state-local tax sys-

tem. The property tax, particularly the part

of the property tax levied on businesses, is

often conceived as a tax on capital. Owner-

ship of capital is proportionately greater

for higher-income households, so any tax

on capital places a higher tax burden

on high-income households than on

low- and moderate-income households.

POLICIES AFFECTING THE

PROPERTY TAX BURDEN ON

BUSINESS

Property tax incentives for business can

only be understood fully within the context

of other major policies affecting the prop-

erty tax burden on business.

State Constitutions

Although they vary enormously and have

evolved over time, state constitutions together

with case law set the framework that guides

legislative action regarding business property

taxes. The most important constitutional

provisions are the uniformity clauses includ-

ed in 39 state constitutions, which require

property taxation at a uniform rate within

a jurisdiction, although they are subject to

important qualifications that vary by state

(Coe 2009).

One example of a uniformity clause is

Alabama’s constitutional requirement that

“all taxable property shall be forever taxed

Figure 2.1

Property Taxes on Business, Fiscal Years 1990–2010

Sources: Cline et al. (2011); State & Local Government Finance Data Query System (2012); U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (2011).

20

30

40

50

60

1.50

1.75

2.00

2.25

2.50

1990 1995 2000 2005 2010

Percent of Total Taxes (lines)

Percent of Private Sector Output (bars)

Percent of Total Property Taxes

Percent of Total State/Local Business Taxes

Percent of

Private Sector

Ouput

16 Policy focus RePoRt � LincoLn institute of Land PoLicy

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

atthesamerate”(ArtXI,sec.217(b)).

Arizona’sconstitutionalrequirementthat

“all taxes shall be uniform upon the same

class of property” provides an important

clue to the practical application of most

suchclauses(Art.IX,sec.1).

Although these clauses ostensibly require

all property to be taxed at a uniform rate,

in reality most allow differential taxation

between different classes of property at the

same time that they require uniform taxa-

tion within a given class. But even that re-

quirement is subject to the exceptions that

arise from property tax exemptions, which

areallowedinmoststates.Itisimportantto

realizethatcourts“areinclinedtogivestate

legislatures extensive leeway in their power

to tax, as long as it does not violate any

explicit provision of the state constitution”

(Coe 2009, 131).

State constitutions also commonly

address the issue of exemptions, but they

range from strictly limiting the state legis-

lature’s discretion in granting exemptions

(e.g.,Arizona),toallowingthelegislature

broadlatitude,asinIdaho,whoseconstitu-

tion states, “the legislature may allow such

exemptions from taxation from time to time

asseemnecessaryandjust”(Art.VII,sec.5)

(Coe 2009, 150–151). The Florida consti-

tution addresses the issue of property tax

exemptions for the purposes of economic

development: “Any county or municipality

may . . . grant community and economic

development ad valorem tax exemptions to

new businesses and expansions of existing

businesses.”(Art.VII,sec.3(c)).

A recent legal case challenging tax

incentives for business went all the way

to the U.S. Supreme Court (box 2.1).

Classification or Split Roll

Classification or split roll taxation is a policy,

either constitutional or statutory, that applies

different effective tax rates to different classes

Box 2.1

Cuno Supreme Court Case

I

n 1998 the City of Toledo, Ohio and two local school

districts offered DaimlerChrysler, Inc., a $280 million

tax incentive package to expand operations within the

city. The company estimated that the $1.2 billion devel-

opment of a new Jeep manufacturing facility would cre-

ate thousands of new jobs. The tax incentive package

included a 10-year, 100 percent property tax exemption

and a state franchise tax credit (DaimlerChrysler Corp

v. Cuno [2006]).

Led by Toledo resident Charlotte Cuno, a group of nine

Ohio taxpayers and some area businesses led a law-

suit against DaimlerChrysler, the State of Ohio, and the

City of Toledo charging that the tax incentive package

violated the U.S. Commerce Clause and the Ohio Equal

Protection Clause (Carty 2006). The case was led in

state court, but DaimlerChrysler moved the case to

federal court where the U.S. District Court ruled that

the incentives violated neither the U.S. nor Ohio clause

and dismissed the case (Lunder 2005).

On appeal, in 2005 the U.S. Court of Appeals for the

Sixth Circuit afrmed the U.S. District Court’s ruling

upholding the property tax exemption, but reversed its

ruling on the franchise tax credit, maintaining that the

credit ran afoul of the U.S. Commerce Clause. In March

2006, the U.S. Supreme Court reviewed the lower court

decisions and dismissed the case, ruling that the plain-

tiffs had no standing to challenge the credit for the

state franchise tax.

Summing up the unanimous ruling, Supreme Court Chief

JusticeJohnRobertswrote,“Indeedbecausestate

budgets frequently contain an array of tax and spending

provisions, any number of which may be challenged on

a variety of bases, affording state taxpayers standing to

press such challenges simply because their tax burden

gives them an interest in the state treasury would inter-

pose the federal courts as virtually continuing monitors

of the wisdom and soundness of state scal adminis-

tration, contrary to the more modest role Article III

envisionsforthefederalcourts”(DaimlerChrysler

Corp v. Cuno [2006]).

Kenyon, LangLey & Paquin � Rethinking PRoPeRty tax incentives 17

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

of property.Effectivetaxratesarecomputed

by dividing total tax liability by total prop-

erty value. Comparison of effective instead

of statutory tax rates is particularly impor-

tant when comparing one jurisdiction that

assesses property at market value with an-

other jurisdiction that assesses property at

some fraction of market value. For example,

a jurisdiction can levy an effective property

tax rate of 1 percent either by assessing

property at 100 percent of market value and

employing a statutory tax rate of 1 percent,

or by assessing property at 50 percent of mar-

ket value and employing a 2 percent tax rate.

States that employ classification typically

use it to apply higher tax rates to commer-

cial, industrial, and other business property

than to residential property. Classification

can be accomplished in two ways: statutory

tax rates can vary by class, or the ratio of

assessed value to market value can vary by

class. As an example of the latter, Alabama

applies a uniform statutory tax rate to all

types of property, but assesses utility prop-

erty at 30 percent of market value; commer-

cial and industrial property at 20 percent;

and residential property at 10 percent (Sig-

nifcant Features of the Property Tax 2012).

Twenty-six states plus the District of

Columbia employ some form of property

tax classification and California policy mak-

ers have been considering adopting a split-

roll property tax in order to increase property

taxes on businesses relative to residential

property (Lee and Wheaton 2010; Sheffrin

2009). Many state constitutions address the

issue of classification. Some, like Florida’s,

prohibit classification, but others give the

state great leeway in creating a classification

system. Some place limits on classification,

18 Policy focus RePoRt � LincoLn institute of Land PoLicy

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

such as the Massachusetts constitution,

which limits the number of permissible

classes to four (Coe 2009).

Certain states, including Connecticut,

Illinois,Massachusetts,NewYorkand

RhodeIsland,allowlocalgovernments

some discretion in adopting or adjusting

property tax classification. Others, such as

Colorado, have adopted a system termed

“dynamic classification” in which effective

tax rates for each property class are changed

over time in order to maintain a specific re-

lationship between the share of the property

tax paid by residential properties and other

properties (Bell and Brunori 2011).

Assessment Practices

Although classification systems are generally

used to impose greater effective tax rates on

business than residential properties, a state

can accomplish the same thing as a de facto

rather than a de jure policy. Some states

even had long-standing policies of assessing

business properties at a greater proportion

of market value than residential properties

before enacting legislation establishing clas-

sification systems to codify such practice.

Another way in which business properties

can be systematically taxed differently from

residential property is by using a different

appraisal methodology. Of the three stan-

dard methods—sales, income, and cost—

the sales method is most often used for resi-

dential properties and least often for business

properties. Although each methodology

should in theory lead to the same valuation,

in practice they may differ. One concern is

that the cost method might systematically

undervalue properties, which would tend

to lead assessors who employ that method

to undervalue business properties relative

to residential properties (Cornia 1995).

Personal Property Taxes

Inconsideringpropertytaxesonbusiness,

it is important to include personal property

as well as real property, which consists of

land, improvements to land, and buildings.

Personal property includes machinery and

equipment, inventories, and fixtures such as

furniture or office equipment, and is typically

taxed only when owned by a business. Per-

sonalpropertyischaracterizedbyitsmobil-

ity, whereas real property is immovable (Almy,

Dornfest,andKenyon2008).Inpartbecause

of this greater relative mobility, the case for

taxing business personal property is weaker

than that for taxing business real property.

For example, a business could easily move

inventories from a high-tax to a low-tax

jurisdictioninordertominimizetaxliability.

Over time, personal property has become

a smaller part of the U.S. property tax base,

as most household personal property and

later some business personal property was

removed from the tax base. Personal prop-

erty as a share of the local property tax

Kenyon, LangLey & Paquin � Rethinking PRoPeRty tax incentives 19

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

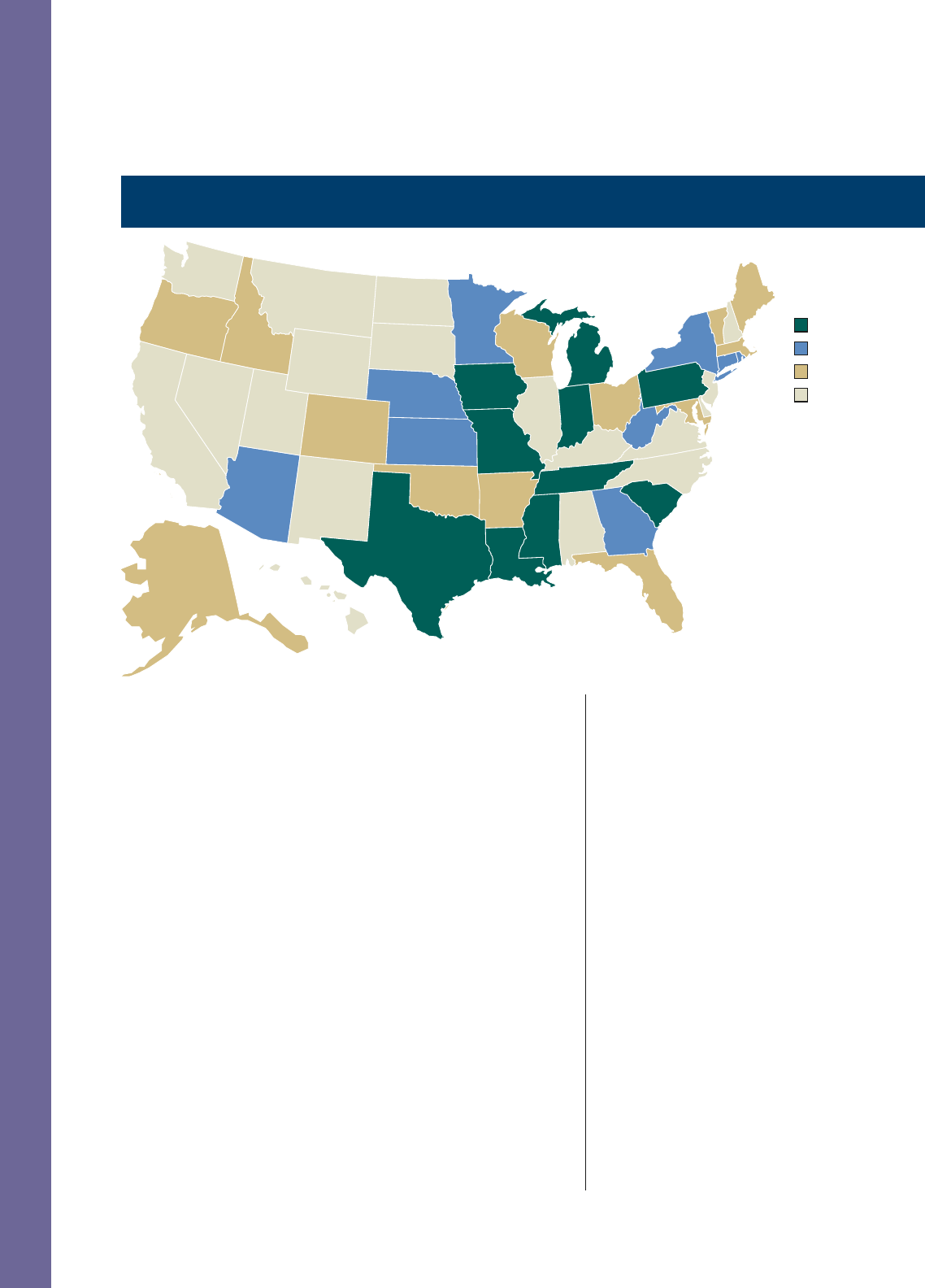

Figure 2.2

Effective Property Tax Rates for Urban Commercial Property ($1 million value), 2010

base was 17 percent in 1956, 13 percent

in 1971, and 10 percent in 1986 (Mikesell

1995).In1961,fourstatesexemptedper-

sonal property from taxation; by 2011,

12 states had exempted personal property

(Mikesell1995;Thompson/ReutersRIA

2012).Inthepast12years,8statesreduced

their reliance on personal property taxes,

including raising exemption levels and

eliminating personal property taxes on

inventories (Drenkard 2012).

Ohio and Michigan recently reduced

taxation of business personal property as

part of their tax reform initiatives. Ohio

adopted a new commercial activity tax,

exempted new tangible personal property

from taxation, and enacted a five-year

phase-out of taxes on existing personal

property. Michigan replaced its Single

Business Tax with a new business tax struc-

ture at the same time that it significantly

reduced personal property taxes for both

commercial and industrial taxpayers

(NeubigandCline2008).

EFFECTIVE TAX RATES ON

BUSINESS PROPERTY

The most comprehensive measure of

effective tax rates is the one calculated for

the largest city in each state by the Minnesota

Taxpayers Association (MTA), which esti-

mates effective tax rates for commercial,

industrial, and homestead properties (Min-

nesota Taxpayers Association 2011). The

MTA takes a number of factors into account,

such as differences in assessment practices;

exemptions, credits, or refunds that apply

to a majority of taxpayers; tax rates for all

state and local governments that serve a

city; and tax classification when it is used.

Figure 2.2 shows that effective property

tax rates for urban commercial properties

2.50% to 4.01%

1.96% to 2.49%

1.40% to 1.95%

0.65% to 1.39%

Rate for Largest

City in Each State

Note: In most cases property

tax structures are uniform across

states, with the exception of

Illinois and New York. This map

illustrates the effective tax rate

for Aurora, Illinois (2.39%). The

rate for Chicago is 1.79%

Source: Minnesota Taxpayers

Association (2011, 21).

20 Policy focus RePoRt � LincoLn institute of Land PoLicy

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2.00% to 3.15%

1.50% to 1.99%

1.20% to 1.49%

0.44% to 1.19%

Rate for Largest

City in Each State

Figure 2.3

Effective Property Tax Rates for Urban Industrial Property (50% Personal Property, $1 million value), 2010

with a $1 million market value range be-

tween 0.7 percent in Cheyenne, Wyoming,

and 4 percent for Detroit, Michigan. These

rates are highest in the Midwest and Middle

Atlantic states and lowest in the West. They

vary for many reasons, including reliance

on other local revenue sources (e.g., sales

tax and user fees), property values, and the

level of local government spending.

Because some states tax personal prop-

erty and others do not, estimates of effective

tax rates for industrial property depend on

the proportion of the total property value

that is personal property. Figure 2.3 shows

effective tax rates for urban industrial prop-

erty valued at $1 million, assuming that half

of thevalueispersonalproperty.Effective

tax rates for industrial property are some-

what lower than for commercial property,

ranging from 0.4 percent in Wilmington,

Delaware, to 3.2 percent in Columbia,

South Carolina. These rates are highest

in the Midwest and South and lowest

in the West.

Inthemajorityof citiestheeffective

tax rates for commercial properties exceed

those for homesteads. Figure 2.4 shows the

ratio of commercial to homestead effective

property tax rates for the largest city in each

of 25states.Effectivetaxratesoncommer-

cial properties exceed rates on homestead

properties in 20 of them. A few cities, such

asBaltimore,Maryland,andVirginiaBeach,

Virginia,haveahighertaxonhomestead

properties than on commercial properties.

The MTA has tracked the ratio of effec-

tive tax rates of commercial versus home-

stead property since 1998, when that ratio

was 1.76, indicating that on average across

the country commercial properties were

taxed about 76 percent higher than home-

stead properties. That ratio declined until

2002, then rose through 2008, and has

declinedslightlysincethen.In2010the

Note: In most cases property

tax structures are uniform

across states with the exception

of Illinois and New York. This

map illustrates the effective tax

rate for Aurora, Illinois (1.44%).

The rate for Chicago is 1.18%.

Source: Minnesota Taxpayers

Association (2011, 23).

Kenyon, LangLey & Paquin � Rethinking PRoPeRty tax incentives 21

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Figure 2.4

Ratio of Commercial to Homestead Effective Property

Tax Rates, 2010

Notes: Figure shows the largest city in the 25 most populous states, with the

exception of Illinois and New York, which show the second largest city. The U.S.

average is for the largest city in each state, with New York City excluded.

Source: Minnesota Taxpayers Association (2011, 14).

ratio was 1.72 (Minnesota Taxpayers

Association 2011).

Whether or not effective tax rates for

industrial properties exceed those for home-

steads depends on the split of industrial

property between personal and real prop-

erty.In2010,thenationwideaverageof

effective property tax rates on median value

homes across the United States was 1.34

percent. This fell short of the 1.43 percent

effective tax rate for urban industrial prop-

erty valued at $1 million, assuming that 50

percent of the total property value was per-

sonal property. However, it would exceed

the 1.3 percent rate if personal property

was assumed to account for 60 percent of

total property value (Minnesota Taxpayers

Association 2011).

Itisimportanttonotethateffectivetax

rates measure the initial incidence of prop-

erty taxes, but other studies explore final

incidence, a more complicated concept that

takes into account the fact that the ultimate

burden of taxation always falls on persons.

That is, depending upon factors such as

whether a business serves a local or national

market, the final incidence of business taxes

will fall on business owners, workers, or

consumers.

SUMMARY

Requiring businesses to pay property taxes

is based on three rationales: businesses ben-

efit from local government services; business

property tax payments are an important

revenue source for local governments; and

business property tax payments add a pro-

gressive element to the state-local tax sys-

tem. This chapter surveyed policies other

than property tax incentives for business

that serve to either increase the property

tax burden on business (e.g., classification

or split-roll systems) or decrease the burden

(e.g., phasing out personal property taxes).

Effectivetaxratesoncommercialand

industrial property vary enormously across

the United States for a variety of reasons.

Inthelargestcityinmoststatestheeffective

tax rates on commercial property exceed

those for homeowners, but in some states

the reverse is true.

0 1 2

VA: Virginia Beach

MD: Baltimore

NC: Charlotte

NJ: Newark

WA: Seattle

CA: Los Angeles

WI: Milwaukee

IL: Aurora

TX: Houston

MI: Detroit

OH: Columbus

GA: Atlanta

FL: Jacksonville

PA: Philadelphia

TN: Memphis

U.S. Average

NY: Buffalo

MO: Kansas City

AL: Birmingham

LA: New Orleans

MN: Minneapolis

AZ: Phoenix

IN: Indianapolis

SC: Columbia

CO: Denver

MA: Boston

3

Higher tax rates on

commercial properties

Equal tax rates

Higher tax rates on

homestead properties

22 Policy focus RePoRt � LincoLn institute of Land PoLicy

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

CHAPTER 3

The Impact of Property Taxes

on Firm Location Decisions

T

he site location process used by

many businesses, as well as eco-

nomic theory and empirical studies,

suggests that the impact of proper-

ty taxes on firm location decisions depends

on the type of facility and the geographic

area under consideration.

THE SITE LOCATION PROCESS

With over 36,000 jurisdictions in the United

States and a much larger number of poten-

tial sites, firms could not possibly evaluate

all sites across the many location criteria

that are typically considered in such deci-

sions.Instead,thesitelocationprocessnor-

mally occurs in several stages during which

firms systematically narrow the geographic

area under consideration and compare

with increasing detail the competing

locations. The importance of property

tax differentials in firm location decisions

varies with the stage of site selection.

A two-stage process is one way to think

about site selection, in which a firm first

chooses a metropolitan area and then a

specific site within that region. Property

taxes are relatively unimportant in choosing

a metropolitan area since tax differences

have a much smaller impact on profits than

differences in costs for labor, transportation,

energy, and rent or occupancy. However,

since effective property tax rates can vary

significantly within a metropolitan area,

differences in property taxes can be a

deciding factor when selecting a single site

within an area. At this stage, state taxes

Kenyon, LangLey & Paquin � Rethinking PRoPeRty tax incentives 23

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

and regulations as well as energy costs are

often constant; labor cost differences are

small because of the ease of intrametropoli-

tan commuting; and there is little variation

in proximity to suppliers or consumers.

Ady (1997) describes a more detailed

three-stage process for facility location,

developed by Fantus Consulting, which

isnowusedwidelybysiteselectors.Inthe

first stage, the search is narrowed to a broad

region, several states, or several counties

based primarily on wage differentials, trans-

portation variables (for manufacturing), and

project-specific essentials such as access to

port facilities, right-to-work laws, or prox-

imity to an engineering school. Taxes will

be considered, but only at a high level to

eliminate clearly uncompetitive states.

Inthesecondstage,3to5communities

will be chosen out of a list of as few as 15

to 20 or as many as 50 to 100. The focus is

on modeling operating costs for the specific

project in each community. According to a

database of firms using Deloitte & Touche/

Fantus Consulting for site selection during

1992–1997, Ady (1997) reports that total

operating costs for a typical manufacturing

facility can be estimated with the following

weights for five categories of input costs:

labor (36 percent), transportation (35), utili-

ties (17), occupancy (8), and taxes (4). Again,

taxes are relatively unimportant at this stage

because they account for a small part of

geographically variable costs.

But in the third stage, when choosing a

specific site, firms examine actual properties

that can meet their needs, and then all taxes

and incentives are compared in detail and

the quality of public services is measured

carefully. As Ady (1997, 80) says, “The only

case where taxes alone could sway a loca-

tion decision is a company relocation in a

relatively autonomous geographic area,

such as a city or metropolitan area.”

THE EFFECT OF INPUT

COST DIFFERENCES

The importance of differences in each cost

factor will depend on each factor’s share

of total costs for the firm and the extent of

variation across states, regions, or jurisdic-

tions. Large variations will have little effect

on firm location decisions if a cost factor

accounts for a small share of total costs, while

factors accounting for a large share will be

unimportant if there is little variation across

competing regions.

When a manufacturing firm chooses

a region in which to locate its facility, its

decision is typically driven by proximity to

suppliers and consumers (and the transpor-

tation costs to reach them) and the wages,

skills, and availability of local workers. That

is because three-quarters of costs for the

average manufacturing firm are inputs pur-

chased from suppliers, with labor account-

ingformostof theremainingcosts.Infact,

figure 3.1 shows that the manufacturing

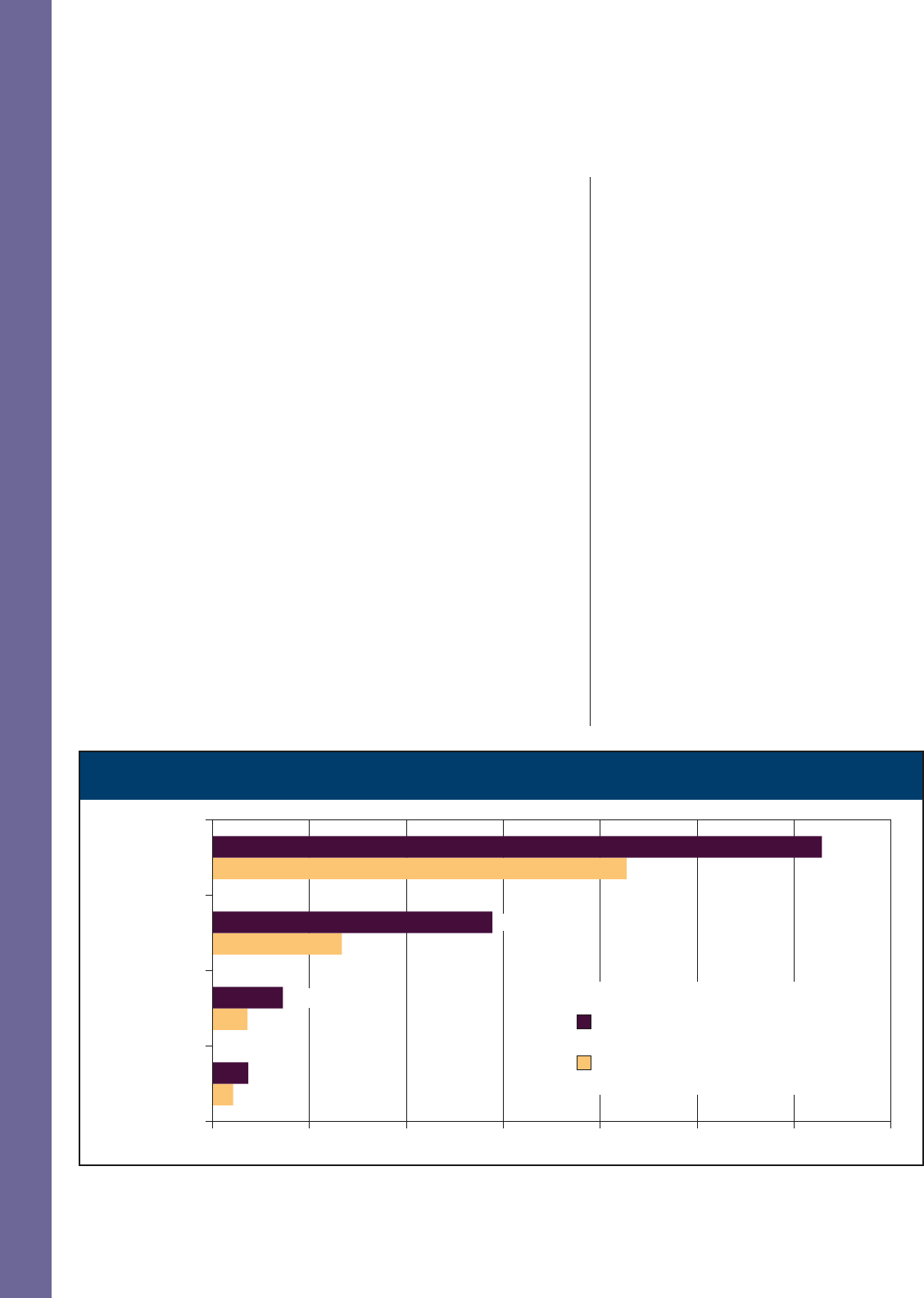

Figure 3.1

Input Costs as a Share of Total Costs for the Manufacturing

Sector, 2004–2009

Note: See Appendix Notes for an explanation of the calculations.

Sources: Phillips et al. (2011); U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (2011).

21.8%

2.7%

0.8%

0.3%

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

Labor Energy State/Local

Taxes

Property

Taxes

24 Policy focus RePoRt � LincoLn institute of Land PoLicy

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Figure 3.2

Impact of Relocation to Different States on Total Costs for an Average Manufacturing Facility

Note: See Appendix Notes for an explanation of the calculations.

Sources: Moody’s Analytics, Inc. (2011); Phillips et al. (2011); U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (2011); U.S. Energy Information Administration (2011).

sector spends nearly 75 times more on

labor (21.8 percent) than on property taxes

(0.3 percent).

Eventhoughtaxesvarymoreacross

states than do labor costs, differences in

labor costs are still much more likely to

drive firm relocations. Figure 3.2 estimates

the effect on an average manufacturing

facility of relocating from a high-cost state

to a low-cost state, using actual data on

state input costs and the share of total costs

for each input. Moving from the state with

the fifth highest state-local taxes to the state

with the fifth lowest will reduce business

costs by 0.4 percent on average whereas

moving from the state with the fifth high-

est labor costs to the fifth lowest will save

almost 9 times as much (3.1 percent).

The importance of taxes is much greater

when a firm chooses a specific site within a

metropolitan area. At this stage, differences

in the cost of labor, energy, state taxes,

and transportation are normally small, but

property taxes often vary more across indi-

vidual jurisdictions within a given region

than they do across states. For example,

among 103 Massachusetts municipalities

in the Boston metropolitan area that have

notzonedoutindustry,effectiveproperty

tax rates on industrial properties ranged

from 1.13 percent in the municipality with

the tenth lowest rates to 2.82 percent in the

municipality with the tenth highest rates.

This means that a firm’s total operating

costs could be reduced by 0.5 percent by

locating in the low-tax municipality instead

of thehigh-taxone(seeAppendixNotes

for calculations).

ECONOMIC THEORY

Differences in effective property tax rates

on new investment will affect a jurisdiction’s

ability to attract mobile capital investment

in direct and indirect ways. Above-average

property taxes on business will directly

reduce business investment, because higher

property taxes decrease the rate of return

oninvestment.Accordingtothe“NewView”

0.1%

0.2%

0.7%

2.1%

0.2%

3.1%

0.0% 0.5% 1.0% 1.5% 2.0% 2.5% 3.0% 3.5%

Property Taxes

State/Local Taxes

Energy

Labor

1.4%

0.4%

Change in Total Costs from Moving:

From: State with 5th highest costs for input

To: State with 5th lowest costs for input

From: State with 12th highest costs for input

To: State with 12th lowest costs for input

Kenyon, LangLey & Paquin � Rethinking PRoPeRty tax incentives 25

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

of thepropertytaxrstputforthbyMiesz-

kowski (1972), the average business property

tax rate constitutes a profits tax that reduces

the rate of return on business property na-

tionally. Property taxes above the national

average will reduce business activity, land

prices, wages, and the employment rate.

However, higher property taxes are often

associated with higher-quality public services

forbusinessandwillbecapitalizedinto

lower land values. These indirect effects will

tend to increase business investment. Higher-

quality police and fire protection, highways,

infrastructure, utilities, and education all

affect firm location decisions (Ady 1997).

Public services affect firm costs and produc-

tivity, such as the impact of police protection

on insurance rates and the impact of edu-

cation on labor productivity.

If propertytaxdifferentialswerecom-

pletely offset by differences in the quality of

public services, then property taxes would

be benefit taxes and have no effect on

firm location decisions. Oates and Schwab

(1991) have argued that under perfect com-

petition all local government taxes would

be benefit taxes, because jurisdictions would

bid against each other to attract mobile

businesses up to the point where the cost

of providing public services to a firm would

exactly equal the amount it pays in taxes.

Inthiscase,thelevelof publicservices

provided would be economically efficient,

although there would be no scope for

redistribution at the local level.

Some research has cast doubt on the

property tax being a benefit tax for business.

According to Oakland and Testa (1998), in

1995 businesses paid twice as much in state

and local taxes as the cost of public services

they received. However, these estimates de-

pend on assumptions about how the benefits

of public goods are shared between house-

holds and business. For example, if 25 per-

cent of public education spending is count-

ed as a benefit for business, then the esti-

mated ratio of taxes-to-benefits drops

from 2.06 to 1.31.

Inaddition,propertytaxesarecapital-

izedintolandvalues—thatis,forotherwise

identical properties with similar location

advantages and public services, the one with

higher property taxes will have a lower land

value,whichequalizestotalexpensesover

the life of the property. However, Yinger

et al. (1988) found that property tax differ-

entialsarenotfullycapitalizedintoprop-

erty values.

Thus despite some caveats, the balance

of evidence supports the basic intuition that

firm location decisions are responsive to

differences in property taxes. However, the

net effect of a property tax cut on business

26 Policy focus RePoRt � LincoLn institute of Land PoLicy

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

investment in a jurisdiction is much smal-

ler than the direct effect, and depends on

whether the tax cut is financed by reducing

public services for business and the extent

that land values increase in response to

a tax cut.

Inaddition,whilelowerpropertytaxes

should increase business investment, the

effect on employment is less clear, because

lower property taxes reduce the cost of

machinery and equipment relative to labor.

Job growth induced by greater business

investment (i.e., scale effect) could be out-

weighed by job losses due to substituting

machinery for labor (i.e., substitution effect).

Finally, the effect of property taxes on the

location decision for a specific facility can

be significantly different from the average

effect for all firms.

EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE

There are three common approaches

for estimating the effect of taxes on local

economies: surveys, regression analysis,

and representative firm models. Surveys

ask business decision makers about the role

of taxes and incentives in their facility loca-

tion decisions. While surveys can be influen-

tial, they are unreliable since those surveyed

have an incentive to exaggerate the effect of

taxes and incentives on their decisions as a

way to lobby for preferred policies. Regres-

sion analysis and representative firm models

are more reliable because they look at a

firm’s actual decisions and take into account

many of the other local factors that affect

profitability to determine the true impor-

tance of taxes and incentives.

An examination of studies done between

1990 and 2011 suggests that the best litera-