Oregon’s Health Care

Workforce Needs

Assessment 2023

February 2023

Tao Li, MD, PhD

Jeff Luck, MBA, PhD

Veronica Irvin, PhD, MPH

Collin Peterson, MAT, ATC

Alexandra Kaiser, BS

Prepared for:

Oregon Health Authority

Oregon Health Policy Board

1

Table of Contents

Executive Summary............................................................................................................ 2

Findings and Recommendations .................................................................................... 2

Conclusions ..................................................................................................................... 4

Background ......................................................................................................................... 5

Investments in Workforce Development......................................................................... 8

Workforce Resiliency .................................................................................................... 17

Health Care Workforce Trends ........................................................................................ 25

Health Care Workforce Reporting Program Data ........................................................ 25

Areas of Unmet Health Care Need ............................................................................... 32

Impacts of COVID-19 ....................................................................................................... 35

Impacts of COVID-19 on Health Care Visits ................................................................ 35

Impacts of COVID-19 on the Health Care Workforce .................................................. 38

Telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic ..................................................................... 43

The Health Care Workforce Going Forward .................................................................... 51

Traditional Health Workers ........................................................................................... 51

Health Care Interpreters ............................................................................................... 59

Nursing Workforce ........................................................................................................ 63

Primary Care Providers ................................................................................................. 71

Behavioral Health Providers ......................................................................................... 78

Oral Health Providers .................................................................................................... 85

Long-Term Care Workforce .......................................................................................... 92

Public Health Workforce ............................................................................................... 97

Conclusions/Recommendations .................................................................................... 104

Conclusion ................................................................................................................... 106

Acknowledgments .......................................................................................................... 108

List of Abbreviations ....................................................................................................... 110

2

Executive Summary

2023 Oregon Health Care Workforce Needs Assessment

Note—The full report may be found at: https://www.oregon.gov/oha/HPA/HP-

HCW/Documents/2023-Oregon-Health-Care-Workforce-Needs-Assessment.pdf

This biennial Health Care Workforce Needs Assessment informs Oregon’s efforts

to ensure culturally and linguistically responsive care for all.

House Bill 3261 (2017) directs the Oregon Health Policy Board (OHPB) and Oregon

Health Authority (OHA) to produce a biennial assessment of the health care workforce

needed to meet the needs of patients and communities throughout Oregon by February

1 of each odd-numbered year. Oregon’s goal of eliminating health inequities requires

the preparation, recruitment, and retention of a diverse workforce that can deliver

culturally and linguistically responsive health care. This is the fourth such report, which

provides insights into workforce needs in communities across Oregon as well as

general guidance on how to expand and diversify the health care workforce, including

distributing health care provider incentives.

Findings and Recommendations

The report synthesizes policy recommendations across all segments of Oregon’s health

care workforce, based on its review of health care workforce development investments,

workforce resiliency, trends and COVID-19 impacts, and specific workforces requiring

attention. The findings point to some priority recommendations that are provided below.

Improve the diversity of health care providers

Oregon must have a more diverse workforce to achieve the strategic goal of

eliminating health inequities. Key recommendations include:

• Increase investments in training, recruiting, and retaining health care workers

who can provide culturally and linguistically responsive care

• Reduce barriers to entry and advancement for people of color in the workforce

Improve the supply and distribution of the health care workforce

The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated Oregon’s shortage of many types of health

care providers, especially in rural areas. Key recommendations include:

• Continue to fund financial incentives to increase opportunities for training and

education, such as those in the Health Care Provider Incentive Program

• Invest in workforce training through the public workforce system and allied health

educational partners

3

• Address other factors that influence workforce recruitment and retention—

especially in rural areas—such as housing cost and supply, economic

opportunities for partners/spouses, and quality of K-12 education

Enhance the resiliency and well-being of the health care workforce

Health care worker burnout exacerbates workforce shortages, quality of care,

health inequities, and health disparities. Addressing workforce wellness and

resiliency is essential and will require collective action to be effective. Key

recommendations include:

• Coordinate collective actions from public and private stakeholders, as well as

community partners, to cultivate a health system that supports health care

workers, including action to create trauma-informed, anti-racist workplaces

• Invest in assessment and research to inform evidence-based and practice-based

strategies to optimize health care workforce well-being

Expand training/education and career pathways for many segments of

the health care workforce

Expanding training is especially urgent for segments of Oregon’s workforce

where shortages are most acute, such as behavioral health and long-term care.

Education and clinical training opportunities should be expanded for all types of

health care providers. Key recommendations include:

• Ensure adequate numbers of faculty and clinical training placements for nurses

and other licensed professionals

• Establish and fund clear pathways for positions that do not have defined career

ladders based on licensure, including parallel training and work, with a

progression to increased pay and responsibility based on training and experience

Expand use of care delivery models that improve patient access and

promote workforce retention

Although Oregon has been a leader in transforming its health care delivery

system, innovative care models can be expanded to improve patients’ access to

care, promote culturally and linguistically appropriate care, and increase

workforce satisfaction. Key recommendations include:

• Expand telehealth, coupled with health care interpreters, to improve access to

culturally specific or linguistically appropriate services

• Continue to invest in the integration of physical, behavioral, and oral health

care delivery

4

Increase health care systems’ use of community-based health care

providers

Traditional health workers—including peer wellness specialists—and health care

interpreters come from and/or share common lived experiences with their local

communities. OHA should continue to reduce barriers to recruit and retain this

workforce. A key recommendation is:

• Find ways to increase compensation for many health professionals, in particular

traditional health workers—including peer wellness specialists—and health care

interpreters who are underpaid and are underrepresented in certain regions of

the state and among persons of color relative to Oregon’s population

Improve data collection to promote evidence-informed strategies and

diversify the health care workforce

Data collection must be improved to help improve the understanding of

challenges to the workforce. Key recommendations include:

• Ensure that standardized REALD (race, ethnicity, language, and disability) and

SOGI (sexual orientation and gender identity) data are collected for all Oregon

providers and patients

• Expand data collection to include more provider types that incorporate

community-defined evidence practices and improve consistency of data

collection over time

Conclusions

Workforce shortages and lack of diversity in many areas of the health care workforce

are a national problem experienced in Oregon, stemming from historic underinvestment,

current economic and social forces, and systemic racism. There are barriers to entry

and advancement for people of color in the health care workforce, and to receiving

culturally and linguistically responsive care for people experiencing health inequities. In

order to stabilize, expand, and diversify Oregon’s health care workforce so that it can

deliver culturally responsive, effective health care services to all:

• Some professions need increased compensation to attract new individuals and

increase retention

• Many professions with unclear career pathways need better, focused paths for

increasing skills, pay, and impact

• All professions need more support around resiliency and well-being

All the report’s recommendations warrant action by government and non-governmental

entities to ensure Oregon has the workforce it needs to deliver on the commitments of

optimal health for everyone and the elimination of health inequities.

5

Background

Why a Health Care Workforce Needs Assessment?

Oregon has long been working to transform its health care system to achieve health

equity, expand access to care, improve population health outcomes, and ensure a

financially sustainable and high-quality health care system. Thus, it is critical that

Oregon has the workforce needed to effectively deliver high-value care to patients

across the state.

House Bill 3261, passed in 2017, directs the Oregon Health Policy Board (OHPB) to

assess the health care workforce needed to meet the needs of patients and

communities throughout Oregon. The assessment must consider:

1. The workforce needed to address health disparities among medically

underserved populations in Oregon

2. The workforce needs that result from continued expansion of health insurance

coverage in Oregon

3. The need for health care providers in rural communities

The needs assessment informs the disposition of the Health Care Provider Incentive

Fund to improve the diversity and capacity of Oregon’s health care workforce.

This is the fourth report Oregon Health Authority (OHA) has published in accordance

with House Bill 3261. (The legislation required an initial needs assessment report in

2018 and then biennial reports starting in 2019.) As stated in previous reports, it is not

feasible to determine the exact numbers of additional health care workers needed, or

the ideal ratios of health care providers required in each Oregon community to serve the

population’s health care needs. However, these reports can provide insights into the

workforce needs in communities across Oregon, identify needed provider types, and

provide general guidance for distributing health care provider incentives.

Current Context: Health Equity

OHA set an ambitious 10-year strategic goal of eliminating health inequities in the state.

Going forward, an increased focus on equity is needed to ensure that all people in

Oregon can reach their full health potential and well-being. The Health Care Workforce

Committee of the OHPB developed the Health Equity Framework to guide its efforts to

center equity in discussions and decision-making. It is grounded in the Health Equity

Definition adopted by OHPB (Figure 1.1), and OHA’s commitment to anti-racism.

6

Figure 1.1. OHA/OHPB Health Equity definition, updated October 2020

The Healthier Together Oregon: 2020–2024 State Health Improvement Plan, launched

in September 2020, focuses on the following vision:

Oregon will be a place where health and well-being are achieved across the

lifespan for people of all races, ethnicities, disabilities, genders, sexual

orientations, socioeconomic status, nationalities, and geographic locations.

The goals of the State Health Improvement Plan include:

• Implement standards for workforce development that address bias and improve

delivery of equitable, trauma-informed, and culturally and linguistically responsive

services

• Create a behavioral health workforce that is culturally and linguistically reflective

of the communities served

• Ensure cultural responsiveness among health care providers through increased

training and collaboration with Traditional Health Workers

• Require sexual orientation and gender identity training for all health and social

service providers

• Support alternative health care delivery models in rural areas

This focus on equity must include the training, recruitment, and retention of a diverse

workforce that can deliver culturally and linguistically appropriate care. The Oregon

Primary Care Office (PCO) “administers health care workforce recruitment and retention

programs that target federal and state resources to improve care delivery in

communities experiencing inequities, and coordinates with other organizations to

maximize collective impact statewide.”

Oregon will have established a health system that creates health equity when all

people can reach their full health potential and well-being and are not disadvantaged

by their race, ethnicity, language, disability, age, gender, gender identity, sexual

orientation, social class, intersections among these communities or identities, or

other socially determined circumstances.

Achieving health equity requires the ongoing collaboration of all regions and sectors

of the state, including tribal governments to address:

• The equitable distribution or redistributing of resources and power; and

• Recognizing, reconciling, and rectifying historical and contemporary

injustices.

7

Development of the Framework was informed by community input, which included

recommendations to increase the diversity of the health care workforce, and to make

the workplace more welcoming for diverse providers in the areas of:

• Pipeline and career pathways development

• Education, training, and credentialing

• Recruitment, hiring, and retention

• Compensation

• Culturally responsive services and practices environments

• Structure of health care provider incentives

Input from the community engagement was used to develop a set of questions to help

guide discussion and decisions to ensure that Oregon’s health care workforce

development efforts advance opportunities for communities experiencing inequities

(Figure 1.2). The Committee will use these questions in its work moving forward to

reimagine the necessary changes to infuse equity into workforce development policies

and programs that meet OHA’s 10-year goal to eliminate health inequities.

Figure 1.2. Health Care Workforce Committee guiding questions for Equity

Framework

How do Oregon’s health care workforce development efforts advance

opportunities for communities experiencing health inequities?

1. Who are the racial/ethnic communities and communities that are experiencing

health inequities? What is the potential impact of the resource allocation to these

communities?

2. Do the PCO programs ignore or worsen existing health inequities or produce

unintended consequences? What is the impact of intentionally recognizing the

health inequity and making investments to improve it?

3. How have we intentionally involved community representatives affected by the

resource allocation? How do we validate our assessment in questions 1 and 2?

How do we align and leverage public and private resources to maximize impact?

4. How should we modify or enhance strategies to ensure recipient and community

needs are met?

5. How are we collecting REALD and SOGI data (race/ethnicity, language, and

disability and sexual orientation and gender identity data) in PCO awards and

matching recipient demographics with communities served?

6. How are we resourcing and/or influencing system partners to ensure programs

optimize equity?

8

Current Context: COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in significant changes to the health care system

and workforce needs. The disruption from the COVID-19 pandemic, and the response

and recovery, provide an opportunity for further health care transformation going

forward. This report analyzes trends from data collected before and during the COVID-

19 pandemic and then describes impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on Oregon’s

health care workforce.

Investments in Workforce Development

Oregon Workforce Investments

In addition to national efforts, Oregon has made concerted efforts to invest in the

expansion, retention, and diversity of the health care workforce using multiple

strategies. Several programs have been introduced to achieve these goals across a

variety of health care professions.

Health Care Provider Incentive Program

In 2017, the passage of House Bill 3261 established the Health Care Provider Incentive

program (HCPIP) and the Health Care Provider Incentive Fund with the intent of

building health care workforce capacity in rural and medically underserved parts of

Oregon and pooling existing incentive programs into one flexible program. Table 2.1

details the allocation for each incentive for the current biennium. Implementation is

directed by the Oregon Health Policy Board (OHPB) and administered by Oregon

Health Authority (OHA) in collaboration with the Oregon Office of Rural Health. Since

the publication of the last report, additional flexibility for awardees to practice via

telehealth has been approved, significant funding has been made available to the

behavioral health workforce, and there has been an increased focus on how incentives

can better address inequities. HCPIP collected race, ethnicity, and language data for

several incentives using the federal Office of Management and Budget race and

ethnicity categories.

Additionally, two other incentive programs separate from HCPIP are reviewed: Healthy

Oregon Workforce Training Opportunity Grant Program and Rural Medical Practitioner

Tax Credit Program

9

Table 2.1. Incentive Allocation for the 2021-2023 Biennium.

Source: Health Care Provider Incentive Program: Allocation Request, 2022, Oregon Health Authority

*$3 million carried over from the previous biennium

Primary Care Loan Forgiveness

Loan Forgiveness is an incentive for students to receive funding during their education

in exchange for a future service obligation in an underserved rural community that

qualifies as a Health Professional Shortage Area and serves the same percentage of

Medicaid and Medicare patients that exist in the county in which the clinic is located.

Students may receive a loan equal to the cost of their post-graduate training for each

year they choose to practice in a qualified Health Professional Shortage Area for up to

three years. Eligible providers include certain specialties of Physicians, Physician

Assistants, Dentists, Pharmacists, and Nurse Practitioners.

Over the past 5 annual award cycles, 51 students have been awarded $2.6 million

through the Loan Forgiveness incentive. Table 2.2 details the programs and the

average amount of funding received from 2018 to 2022. The number of students who

have applied for the Loan Forgiveness incentive has exceeded the awards that can be

made with available funds.

Incentive

2019-2021 expenditure

2021-2023 allocation

Loan repayment to

primary care, oral health,

and behavioral health

clinicians

$6.5 million

$8.7 million*

Loan forgiveness for

primary care clinicians in

training

$1.0 million

$1.5 million

Rural medical malpractice

insurance subsidies

$2.9 million

$4.0 million

Scholars for a Healthy

Oregon Initiative (SHOI) at

OHSU

$5.0 million

$5.0 million

“SHOI-like” scholarships

at non-OHSU education

institutions

$0.7 million

$2.0 million

Administrative costs

$1.1 million

$1.3 million

Totals

$17.3 million

$22.5 million

10

Table 2.2. Primary Care Loan Forgiveness awards, 2018-2022

School and Discipline

Average Award Amount Per Recipient

OHSU

School of Medicine / MD

$76,383

Physician Assistant / PA

$42,700

School of Nursing / DNP

$32,600

School of Dentistry / DMD

$52,200

School of Pharmacy / PharmD

$35,200

Subtotal

$51,043

Pacific University

Physician Assistant / PA

$35,000*

School of Pharmacy / PharmD

$35,200*

Subtotal

$42,065

Western University COMP-NW

Osteopathic Medicine / DO

$89,371

Overall Average

$52,255

*These numbers have been provided as medians rather than averages to prevent backward calculation to small

numbers.

Source: Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Health Care Provider Incentive Programs in Oregon, 2023, Oregon Health

Authority

Loan Repayment Program

The Loan Repayment Program was designed to help support underserved communities

in the recruitment and retention of health care providers. Providers receive funds to

repay student loan debt based on the balance owed upon joining the Loan Repayment

Program and must be practicing at a qualifying site. Qualifying sites must be in a Health

Professional Shortage Area, serve at a minimum the same percentage of Medicaid and

Medicare patients that exist in the county in which the clinic is located, and been

approved by the Oregon Office of Rural Health. Eligible providers include a range of

health care professionals across primary care, dental, and behavioral health.

From 2018 to 2022, the Loan Repayment Program has allocated more than $16.7

million in loan repayment to 295 clinicians in Oregon including dentists (DDS/DMD),

dental hygienists, physicians (MD/DO), physician assistants, naturopathic doctors,

nurse practitioners, pharmacists, licensed social workers, and several different

behavioral health providers. HCPIP transitioned behavioral health loan repayment in

11

April 2022 to the new incentives available for behavioral health workforce incentives.

(See the Behavioral Health Providers section).

Figure 2.3 shows the distribution of loan repayment recipients across Oregon. A third of

loan repayment recipients have language skills in addition to English, about the same

as the previous report. Over 34% of incentive recipients identified as a person of color

or from Tribal communities, a notable increase from the 27% in the previous evaluation.

In a survey of awardees, over 90% reported satisfaction with the loan repayment

program, highlighting the mental and financial relief it brings as well as the opportunity

to work with underserved populations:

“It has freed me up to do what I love - helping underserved populations with my dental

skills and not drown in student loan debt.” – Oral Health Professional, Urban

“It has made it easier for me to focus on serving the underserved rural populations

without having to worry about my loan repayments.” – Primary Care Professional, Rural

12

Figure 2.3. Loan Repayment Program recipients across Oregon, 2018-2022

Source: Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Health Care Provider Incentive Programs in Oregon, 2023, Oregon Health

Authority

Rural Medical Insurance Subsidy

OHA provides subsidies for provider malpractice insurance premiums for physicians

and nurse practitioners serving in rural areas of Oregon that they would otherwise pay

in full. Reimbursement varies by specialty with providers in obstetric care receiving the

highest reimbursement at 80% of the cost. Family or general practice providers that

offer obstetrical services can receive 60% reimbursement. Providers in anesthesiology,

family practice, general practice, general surgery, geriatrics, internal medicine,

pediatrics, and pulmonary medicine can receive 40% reimbursement. Providers of other

practices not previously listed can receive up to 15% reimbursement. In 2021, 516

recipients received an insurance subsidy. Table 2.4 shows the number of participants

the previous 4 years.

13

Table 2.4. Rural Medical Insurance Subsidy Program Participants

Year

Number of Participants

2018

628

2019

546

2020

491

2021

516

Source: Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Health Care Provider Incentive Programs in Oregon, 2023, Oregon Health

Authority

Scholarships and Scholars for a Healthy Oregon Initiative (SHOI)

SHOI provides full tuition for Oregon Health & Science University (OSHU) students that

agree to practice as a health care provider in a rural or underserved community in

Oregon upon graduation using the Health Care Provider Incentive Fund. “SHOI-like”

programs were later established in the 2019-2021 biennium as a part of the Health Care

Provider Incentive Program at other Oregon universities. Table 2.5 shows the average

amount awarded for “SHOI-like” scholarships. Eligible providers include doctors,

dentists, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners. SHOI awardees must agree to

practice in an underserved Oregon community for a minimum of one year longer than

the total years SHOI funding was received. SHOI awardees can practice at a Federally

Qualified Health Center, a correctional facility, a community mental health clinic, urban

non-profit facility seeing at least 50% Medicaid patients in a health professional

shortage area, rural hospitals or clinics, rural Veterans Affairs facilities, and rural tribal

clinics.

Table 2.5. SHOI-like programs and average awards, 2019-2022

Program

Profession

Average

Award

National University of Natural Medicine

Naturopathic Doctor

$63,785

Pacific University School of Physician

Assistant Studies

Physician Assistant

$75,000

Western University – College of

Osteopathic Medicine of the Pacific

Northwest

Doctor of

Osteopathic Medicine

$117,600

Overall

$84,107

Source: Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Health Care Provider Incentive Programs in Oregon, 2023, Oregon Health

Authority

14

Funding for SHOI is $5 million for the 2021-2023 biennium. Since HCPIP’s inception,

close to $7 million has been distributed to 55 OHSU students in SHOI scholarships from

2019 to 2021. Over one-third of recipients are nurse practitioner students, 25% are

dental students, 24% are physician assistant students, and 15% are medical doctor

students.

Healthy Oregon Workforce Training Opportunity Grant Program (HOWTO)

The Healthy Oregon Workforce Training Opportunity (HOWTO) Grant Program seeks to

expand health professional training within the state to address shortages and expand

the diversity of the health care workforce. Under the direction of the OHPB, the HOWTO

Grant Program supports locally developed health care workforce programs using

innovative, community-based initiatives. Examples of recent HOWTO grantees include

a Peer Wellness Specialist training program in Portland and workplace learning

programs aimed at providing medical, dental, and behavioral workers to the Latino/a/x

Community in Medford; 345 new workers have been trained across a variety of health

care disciplines. Funding for the HOWTO Grant Program has increased over the years

from $8.4 million in the 2017-2019 biennium to $10.6 million in the 2021-2023 biennium.

Rural Medical Practitioner Tax Credit Program

Rural practitioner tax credits are also available to providers for practicing in areas that

meet the requirements of a designated rural area and whose individual adjusted gross

income does not exceed $300,000. Certified registered nurse anesthetists, dentists,

doctors of medicine (MD), doctors of osteopathic medicine (DO), nurse practitioners,

optometrists, physician assistants, and podiatrists are eligible for participation. Tax

credit amounts are tiered based on distance from city centers with a population of more

than 40,000 people. Providers at practices 10-20 miles away from an urban center

receive $3,000, 20-50 miles away receive $4,000, and 50+ miles away receive $5,000.

A separate rural tax credit is also offered to emergency medical services providers who

serve in rural areas. Table 2.6 shows the number of recipients of the rural medical tax

credit over the previous 4 years.

Table 2.6. Participants in the Rural Medical Tax Credit Program

Year

Number of Participants

2018

2,347 participants

2019

2,265 participants

2020

2,215 participants

2021

1,892 participants

Source: Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Health Care Provider Incentive Programs in Oregon, 2023, Oregon Health

Authority

15

Other Oregon Workforce Investment Programs

Behavioral Health Investment

There are several investments to address behavioral health workforce shortages and

improve diversity in Oregon. House Bill 2949 (2021) and subsequently House Bill 4071

(2022) created the Behavioral Health Workforce Initiative (BHWi) and allocated $80

million to provide incentives to increase the recruitment and retention of providers in the

behavioral health care workforce with a focus on equity and priority populations. House

Bill 4004 (2022) further requires OHA to distribute $132 million in grants to agencies to

be used to increase wages and other compensation for behavioral health practitioners.

There are additional investments at the national and state level to increase

compensation and provide incentives for behavioral health workers. Refer to the

Behavioral Health Providers section for more details.

Public Health Investments

Funding for Public Health Modernization from the Oregon Legislature has increased

from $5 million in 2017 to $30 million in 2021. OHA has requested $286 million for the

2023-2025 biennium for Public Health Modernization which will include workforce

development and retention strategies. OHA Public Health Division has also applied for a

$32 million CDC public health infrastructure grant, with some funding focused on

workforce development. OHA has also contracted out for work such as with universities

to train students to perform activities like case investigation, contact training, data entry

and quality assurance, and vaccine outreach. Refer to the Public Health Workforce

section for more details.

Future Ready Oregon

Future Ready Oregon is a $200 million investment package established under Senate

Bill 1545 (2022) aimed at supporting the education and training of Oregonians in need

of family-wage careers. The Higher Education Coordinating Commission primarily

oversees administering funds and has established different grants to support

recruitment, retention, and career advancement opportunities especially in

manufacturing, technology, and health care industry sectors for historically underserved

communities. As of September 19, 2022, the Higher Education Coordinating

Commission had received 146 applications and is in the process of evaluation for the

Future Ready Oregon Workforce Ready Grants. Seventy-six percent of the applications

were from the health care sector. $9.8 million is to be distributed through the first round

of grant applications.

Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) 30-30-30 Plan

Oregon Health & Science University’s 30-30-30 plan was developed to address health

care workforce shortages and health care inequities that have worsened during the

16

COVID-19 pandemic and have disproportionately affected underserved communities.

OHSU 30-30-30 goal is to increase graduates from OHSU health care programs by

30% and increase student diversity within these programs by 30% by 2030. Under

House Bill 5202, the Oregon Legislature invested $45 million in OHSU 30-30-30. $20

million will be allocated to OHSU to expand current class sizes for health care

professional programs and increase diversity through existing learner programs like

Oregon Consortium of Nursing Education, Area Health Education Centers,

HealthESteps, Wy’east, and OnTrack OHSU!. Another $25 million will go towards the

OHSU Opportunity Fund to provide tuition assistance, loan repayment, and other

student resources to help with recruitment and retainment of more diverse student

bodies at OHSU. Through philanthropy, the OHSU Foundation will seek to match this

investment in its OHSU Opportunity Fund.

National Workforce Investments

National Health Services Corps Program

The National Health Services Corps program is a federal program administered by the

Health Resources and Services Administration. Students and health care providers can

receive scholarships and loan repayments for providing services in federally designated

Health Professional Shortage Areas. Student recipients of National Health Services

Corps scholarships must serve a minimum of 2 years at an approved site within an

Health Professional Shortage Area and be enrolled in an accredited program for

physicians, dentists, nurse practitioners, nurse midwives, or physician assistants. The

National Health Services Corps Loan Repayment Program offers several different loan

repayment opportunities for a variety of health care providers. Recipients can receive

anywhere between $25,000 to $100,000 in loan repayment funds depending on the

health care discipline and amount of service commitment years. Primary care providers,

dental providers, and behavioral health providers working at an approved site in a

Health Professional Shortage Area are eligible for loan repayment. The Health

Resources and Services Administration also provides grant funding to states to conduct

their own loan repayment programs based on state needs. Oregon has received over

$1.4 million in State Loan Repayment Program funds over the last 3 years.

Physician Visa Waiver Program

The Physician Visa Waiver Program (also called the J-1 Visa Waiver Program) is a

federal program that allows international medical students that completed residencies or

fellowships in the United States to stay in the country to practice medicine in an Health

Professional Shortage Area or other medically underserved area. OHA’s Primary Care

Office coordinates the program in Oregon and has state-specific requirements that a

minimum of 40% of all patient visits must be Medicaid, Medicare, and low-income

uninsured patients. The Primary Care Office gives preference to applicants who work as

17

primary care providers, work in rural areas, work in federally qualified health centers,

and work in a facility with a high Health Professional Shortage Area score. Ninety

percent of the physicians participating in the Oregon Physician Waiver Program who

started work three or more years ago completed their contractual obligations in Oregon.

Eighty-eight percent remained with their employer upon completion of their service

contract. All 30 positions were filled for 2022; typically, the program uses all available

slots each program year.

Workforce Resiliency

The Importance of Workforce Resiliency

Work stress refers to “the harmful physical and emotional effects when job requirements

do not match workers’ resources or needs”. It can lead to poor mental and physical

health and cause burnout. A range of socio-cultural and organizational factors can also

contribute to health care workforce burnout. The health care workforce is faced with a

high risk of work stress and burnout due to challenging working conditions such as

excessive workloads, long hours and unpredictable schedules, intense emotions, and

administrative burdens. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health

(NIOSH) found that health care workers are faced with stigma when seeking care for

mental health concerns or substance use disorders.

Burnout has been exacerbated by extreme mental and physical fatigue, isolation, and

moral and traumatic distress and injury during the COVID-19 pandemic. The health care

workforce experienced increased workload in the face of short staffing and shortages in

personal protective equipment (PPE). They experienced anxiety and fear of working

conditions with ongoing risk for hazardous exposures. The health care workforce also

experienced intensely stressful and emotional situations in caring for patients, many of

whom died. According to NIOSH, some health care workers reported symptoms

consistent with post-traumatic stress disorder related to the pandemic, and some

reported residual symptoms due to personal infection with COVID-19.

A recent survey of about 2,500 physicians found a dramatic increase in physician

burnout during the pandemic. Over 60% of physicians reported manifestations of

burnout in 2021 compared with 38% in 2020. Physician satisfaction with work-life

integration declined from 46% in 2020 to 30% in 2021.

18

In Oregon, data from the Larry Green Center survey of primary care showed that as of

November 2021, 39.3% of respondents reported their mental stress/exhaustion at an

all-time high. Over 70% of Oregon respondents reported that mental stress/exhaustion

in their practices at an all-time high, compared to around 60% at national level.

The Oregon Center for Nursing (OCN) recently conducted a statewide survey of well-

being and resiliency among nurses (Figure 3.1). Among more than 5,000 respondents,

83% of nurses reported stress, with the highest reports in long-term care, home

health/hospice, and hospital settings. Eighty percent of respondents felt frustration, and

over 60% reported anxiety, exhaustion, burnout, and being overwhelmed and

undervalued. Top work stressors included “heavy or increased workload,” “uncertainty

about when things will settle down,” and “burnout.” A national study surveyed more than

50,000 registered nurses and found that more than 30% of nurses who left their job

reported burnout as a reason. Nurses who worked more than 40 hours per week were

more likely to report burnout as a reason they left their job.

19

Figure 3.1. Nurses’ well-being survey by the Oregon Center for Nursing

Source: Oregon Center for Nursing. RN Well-Being Mental Health Survey, April 2020.

Governmental public health has also assessed state and local health worker burnout

since COVID-19. The public health workforce has operated under strained resources

even before the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic brought long work hours,

20

increased scrutiny from local elected officials and the public, and in some cases, threats

of violence against public health professionals and their families. Misinformation and

opposition to local public health guidance has led many to discredit public health

officials. These working conditions have led to job-related mental health impacts and an

exodus from the field for public health professionals. In Oregon, almost half of local

health administration roles experienced turnover. Turnover in administration and those

in supervisory roles may mean that remaining staff may have not been well-supported.

Health worker burnout can have many negative consequences. A study estimated the

national cost for burnout-related turnover at $17 billion for physicians and $14 billion for

nurses annually. In 2022, the U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on Building a Thriving

Health Workforce suggested that “health worker burnout harms all of us,” as “the health

worker burnout crisis will make it harder for patients to get care when they need it,

cause health costs to rise, hinder our ability to prepare for the next public health

emergency, and worsen health disparities.” It also highlighted groups of health workers

whose health and well-being have been disproportionately impacted before and during

the pandemic, including health workers of color, immigrant health workers, female

health workers, low wage health workers, health workers in rural communities, and

health workers in tribal communities.

Programs to Improve Workforce Resiliency

In 2017, the National Academy of Medicine launched the Action Collaborative on

Clinician Well-Being and Resilience, a network of more than 200 organizations

committed to reversing trends in clinician burnout. The goals of this collaborative include

raising the visibility of clinician anxiety, burnout, depression, stress, and suicide;

improving baseline understanding of challenges to clinician well-being, and advancing

evidence-based, multidisciplinary solutions to improve patient care by caring for the

caregiver.

In October 2022, the National Academy of Medicine Clinician Well-Being Collaborative

published a National Plan for Health Workforce Well-Being. The National Plan calls on

multiple actors – including health care and public health leaders, government, payers,

industry, educators, and leaders in other sectors - to “cultivate a health system to

support care providers and optimize their well-being.” To better support the health

workforce and the health of all communities, the National Plan highlighted seven

priorities, including:

• Create and sustain positive work and learning environments and culture.

• Invest in measurement, assessment, strategies, and research.

• Support mental health and reduce stigma.

• Address compliance, regulatory, and policy barriers for daily work.

21

• Engage effective technology tools.

• Institutionalize well-being as a long-term value.

• Recruit and retain a diverse and inclusive health workforce.

As the National Plan pointed out, these priorities are urgent and complex, as “no single

actor or sector can move the needle on its own.” It needs collective action by everyone

—from health workers to the public to multi-sectoral leaders— to strengthen health

workforce well-being.

The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on Building a Thriving Health Workforce in 2022

called for collaboration from a variety of public and private stakeholders, including

federal, state, and local government and health care organizations, health insurers,

technology companies, training programs, and accrediting bodies, to tackle health care

worker burnout (Figure 3.2). Actions called for include:

• Protecting the health, safety, and well-being of all health workers

• Eliminating punitive policies for seeking mental health and substance use care

• Reducing administrative and other workplace burdens to help health workers

make time for what matters

• Transforming organizational cultures to prioritize health worker well-being and

show all health workers that they are valued

• Recognizing social connection and community as a core value of the health care

system

• Investing in public health and public health workforce.

22

Figure 3.2. Solutions to health worker burnout, from the U.S. Surgeon General’s

Advisory on Building a Thriving Health Workforce

Source: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on Building a Thriving Health Workforce.

In 2021, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), through the Health

Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), allocated $103 million from the

American Rescue Plan to be spent over a three-year period to reduce burnout and to

promote mental health among the health workforce. Funding will be provided to health

care organizations to promote resilience and mental health among health professional

workforce, and for educational institutions and other appropriate entities training those

23

early in their health careers to promote resiliency within the workforce. Awards will also

be made to provide tailored training and technical assistance to HRSA's workforce

resiliency programs. In Oregon, Northeast Oregon Network and Legacy Emanuel

Hospital & Health Center both received over $2 million HRSA awards to support health

workforce resiliency.

The passage of the Dr. Lorna Breen Health Care Provider Protection Act (HR 1667) in

2022 established grants and requires activities to support the mental and behavioral

health of health workers. For example, it establishes grants for training health

professions students, residents, or health care professionals in evidence-informed

strategies to reduce and prevent suicide, burnout, mental health conditions, and

substance use disorders. The legislation also establishes a national evidence-based

education and awareness campaign targeting health care professionals to encourage

them to seek support and treatment for mental and behavioral health concerns.

The Oregon Wellness Program provides wellness support for physicians, nurses, and

other health care professionals in Oregon. The program promotes health care

professionals’ well-being through free counseling, education, and research. In 2021, the

OCN launched the RN Well-Being Project to aid workplaces in developing interventions

that nurses feel are necessary to improve their mental and emotional well-being. OCN

compiles resources to help nurses access care and build resilience. It is also working on

innovative solutions for employers to make systematic culture change to best support

their nurses.

The Oregon Health Authority (OHA) is taking the following steps to support behavioral

health providers (see the Behavioral Health Providers section):

• Childcare for workers: OHA provided $8 million to hundreds of licensed

behavioral health providers for childcare stipends. The stipends went directly to

staff, improved supervision, and working environment improvements.

• Retention and hiring bonuses: OHA provided $15 million to provide retention

and hiring bonuses of up to $2,000. The bonuses went to more than 7,000

workers serving clients directly in residential settings.

• Residential emergency staffing needs: OHA provided staff support to both

children’s and adults’ licensed behavioral health facilities to offset the impact of

COVID-19 on the workforce.

• Vacancy payments and rate increases: Vacancy payments are Medicaid-

reimbursed and are allowed for empty beds when the reason for the bed

vacancy is due to the pandemic. OHA has provided more than $30 million

vacancy payments to residential providers impacted by the pandemic and

helped provide stable income. OHA also implemented a temporary 10% rate

24

increase for residential behavioral health providers during COVID-19. Almost

$13 million has been paid directly to providers and to CCOs for providers.

• Reducing administrative burdens: OHA reduced administrative burdens on

behavioral health programs, pausing more than 40 reporting requirements.

25

Health Care Workforce Trends

Health Care Workforce Reporting Program Data

Methodology

Oregon was one of the first states in the country to legislatively mandate reporting by

health care professionals. Oregon Health Authority’s Health Care Workforce Reporting

Program was created in 2009 with the passage of House Bill 2009, which required

Oregon Health Authority (OHA) to collaborate with seven health profession licensing

boards to collect health care workforce data during their license renewal processes.

During the 2015 Oregon Legislative session, Senate Bill 230 added ten more health

licensing boards to this data collection program. Oregon’s 17 licensing boards

participating in this data collection are outlined in Table 4.1, with the 40 occupations that

they license. The data collected on these providers include information submitted to the

licensing boards and data from the Health Care Workforce Survey. This data is used to

understand Oregon’s health care workforce, inform public and private educational and

workforce investments, and provide data to inform policy recommendations for state

agencies and the Legislative Assembly regarding Oregon’s health care workforce.

Table 4.1. Oregon Health Care Licensing Boards

Licensing Board

Licenses

Oregon Medical Board

Doctor of Medicine (MD), Doctor of Osteopathy

(DO), Doctor of Podiatry (DPM), Licensed

Acupuncturist, Physician Assistant (PA)

Oregon Board of Dentistry

Dentist (DMD/DDS), Registered Dental Hygienist

(RDH)

Oregon Board of Optometry

Optometrists (OD)

Oregon Board of Naturopathic Medicine

Naturopathic Physician (ND)

Oregon State Board of Nursing

Registered Nurse (RN), Nurse Practitioner (NP),

Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetist (CRNA),

Clinical Nurse Specialist (CNS), Licensed

Practical Nurse (LPN), Certified Nursing Assistant

(CNA)

Oregon Board of Chiropractic Examiners

Chiropractic Examiners (DC),

Chiropractic Assistants (CA)

Oregon Occupational Therapy Licensing

Board

Occupational Therapist (OT),

Occupational Therapy Assistant (OTA)

Oregon Board of Physical Therapy

Physical Therapist (PT),

Physical Therapist Assistant (PTA)

Oregon Board of Massage Therapists

Licensed Massage Therapist (LMT)

26

Licensing Board

Licenses

Respiratory Therapist and

Polysomnographic Technologist

Licensing Board

Polysomnographic Technologists (LPSGT),

Respiratory Therapists (LRCP)

Oregon Board of Licensed Dieticians

Licensed Dietitian (LD)

Oregon Board of Psychology

Psychologist (PSY)

Oregon Board of Licensed Clinical Social

Workers

Licensed Clinical Social Worker (LCSW),

Clinical Social Worker Associate (CSWA)

Oregon Board of Licensed Professional

Counselors and Therapists

Licensed Marriage and Family Therapist (LMFT),

Licensed Professional Counselor (LPC)

Oregon Board of Pharmacy

Pharmacists (RPH),

Certified Pharmacy Technician (CPhT)

Oregon Board of Medical Imaging

Nuclear Medicine Technologist (NMT), MRI

Technologist (MRI), Radiation Therapist (RDT),

Radiographer (RDG), Sonographer (SNG),

Limited Permit X-ray Machine Operator (LXMO)

Oregon Board of Examiners for Speech-

Language Pathology and Audiology

Audiologist (AUD), Speech-Language

Pathologists (SLP), Speech-Language

Pathologists Assistants (SLPA)

Source: OHA Office of Health Analytics, Oregon’s Health Care Workforce Reporting Program

Findings

In total, there were nearly 192,000 licensed health care professionals in this reporting

program dataset as of January 2022. The direct patient care FTE by occupation and

year from 2016-2022 is shown in Figure 4.2, along with the annual average percent

change in that time period. Noteworthy average annual increases were observed for

counselors and therapists (13.5%), clinical social work associates (9.4%), nurse

practitioners (8.1%), physician assistants (8.1%), and licensed dietitians (7.8%).

27

Figure 4.2. Average annual percent change in direct patient care FTE varies by

occupation.

Source: OHA Office of Health Analytics, 2022 Oregon’s Licensed Health Care Workforce Supply.

Table 4.3 shows primary care provider FTE changes by occupation over years. Primary

care physician FTE decreased in 2022 compared to 2020, as did naturopathic

physicians. At the same time, nurse practitioners and physician assistants FTE

increased. Overall, there is a 2% increase in primary care provider FTE from 2020 to

2022.

28

Table 4.3 Primary care provider FTE changes by occupation

Occupation

2020

2022

Change

Physicians

4,716

4,638

- 1.7 %

Nurse practitioners

1,020

1,241

21.7%

Physician assistants

685

694

1.3%

Naturopathic Physicians

220

206

- 6.4%

TOTAL

6,641

6,779

2.1%

Source: OHA Office of Health Analytics, 2022 Oregon’s Licensed Health Care Workforce Supply.

Figure 4.4 shows health care professionals’ plans to increase hours, reduce hours, or

leave the workforce in 2021 and 2022. Clinical nurse specialists (7.8 %) and certified

pharmacy technicians (6.5%) had the highest rates of plan to leave the Oregon

workforce. Those who intended to increase practice hours at the highest rates were

licensed massage therapists (14.7%) and occupational therapy assistants (12.5 %). See

The Health Care Workforce Going Forward section for more detail on provider specialty

groups.

30

Starting in 2021, the Health Care Workforce Reporting Program’s survey of providers

began using the REALD tool. REALD outlines how to collect data on race, ethnicity,

language, and disability with more granularity. The tool can be used to more accurately

identify inequities and subpopulations that may benefit from focused interventions, and

help address unique inequities that occur at the intersections of race, ethnicity,

language, and disability.

The gender and race/ethnicity breakdown for health care provider compared with

Oregon’s general population is shown in Table 4.5. Female providers are

overrepresented in most professions, though men tend to be overrepresented in fields

requiring more years of formal training, such as physicians and dentists. Latino/a/x

providers are underrepresented in most health care professions. See The Health Care

Workforce Going Forward section for more detail on provider specialty groups.

32

As shown in Figure 4.6, Spanish is the most common language spoken other than

English among licensed providers (about 10%). The next most common languages

spoken are Chinese (including Mandarin and Cantonese), Tagalog, Vietnamese,

French, and Russian. Less than 1% of the licensed health care providers are native

speakers or have advanced proficiency in each of those languages. Thus, many

patients who speak a language other than English need the assistance of a Health Care

Interpreter (see the Health Care Interpreters section).

Figure 4.6. Top Languages Spoken by the Workforce: Workforce Stratified by

Proficiency, Compared to Oregon Population

Source: OHA Office of Health Analytics, Oregon’s Health Care Workforce Reporting Program

Areas of Unmet Health Care Need

Methodology

The Oregon Office of Rural Health at Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU)

produces a report annually on Oregon Areas of Unmet Health Care Need, presenting

community-level data on access to care and health care workforce capacity. Nine

measures of access to primary physical, behavioral, and oral health care are included in

the report:

• Travel time to nearest Patient-Centered Primary Care Home

• Primary care capacity (percent of primary care visits able to be met)

33

• Dentist FTE per 1,000 population

• Licensed behavioral health provider FTE per 1,000 population

• Percent of population between 138% and 200% of the federal poverty level

• Inadequate prenatal care rate per 1,000 births

• Preventable hospitalizations per 1,000 population

• Emergency department non-traumatic dental visits per 1,000 population

• Emergency department mental health/substance abuse visits per 1,000

population

A composite score of unmet need is calculated from these measures, ranging from 0 to

90, with lower numbers indicating greater unmet need. Scores are calculated for each of

the 128 primary care service areas in the state. The Office of Rural Health defines

primary care service areas using zip code data, with at least 800 people in each service

area. Generally, service areas are defined considering topography, social and political

boundaries, and travel patterns, and health resources are located within 30 minutes

travel time in any given service area. For 2022, the unmet health care need scores by

service area ranged from 18 (worst) to 79 (best), with a statewide average of 49. (Figure

5.1). It is important to note that the Areas of Unmet Health Care Needs report does not

fully assess unmet health care needs by race/ethnicity in different parts of the state.

Equitable health care access is dependent on the diversity and language abilities of

providers, and the intersectionality of urban/rural geography and race/ethnicity is an

important consideration.

34

Figure 5.1. Unmet Health Care Needs Scores by Service Area

Source: The Oregon Office of Rural Health. The Oregon Area of Unmet Health Care Need report.

Table 5.2 shows scores for unmet need for 2022 by geographic area: urban, rural, and

frontier. Rural areas are defined as geographic areas that are ten or more miles from

the centroid of a population center of 40,000 people or more. Counties with six or fewer

people per square mile are defined as frontier. On average, rural and frontier areas

have more unmet health care need than urban areas in Oregon. See The Health Care

Workforce Going Forward section for more detail on provider specialty groups.

Table 5.2. Average Unmet Health Care Need Score by Geographic Area

Unmet Health Care Need Score

Lower numbers indicate more unmet need

Statewide-Oregon

49.4

Urban

62.1

Rural (not frontier)

45.9

Frontier

48.9

Source: The Oregon Office of Rural Health. The Oregon Area of Unmet Health Care Need report.

35

Impacts of COVID-19

Impacts of COVID-19 on Health Care Visits

Early in the pandemic, planning and preparing for the care of an unknown number of

anticipated COVID-19 patients consumed health care resources. Other initial impacts

on the health care system included a statewide ban on elective surgeries, people

choosing not to go to clinics in person because of concerns about being exposed to the

Coronavirus, and health care facilities changing operating practices (including

temporary closures). The impacts of COVID-19 on reduced health care visits were

greatest during the first months of the pandemic. The Larry Green Center, in partnership

with the Primary Care Collaborative, began conducting a weekly nationwide survey in

mid-March 2020 about the impacts of COVID-19 on primary care, and Oregon-specific

responses are available through the Oregon Rural Practice-based Research Network.

Data from the Larry Green Center showed that in April 2020, about 90% of respondents

in Oregon reported high or severe impacts of COVID-19 on their practice, and almost all

respondents indicated that their practice experienced a decline in patient volume.

As shown in Figure 6.1, by early April 2020, the number of outpatient visits nationally

decreased by more than half, according to an analysis of national data published by the

Commonwealth Fund. By October 2020 outpatient visits had returned to baseline levels.

Due to a COVID-19 surge during the last two months of 2020, outpatient visit volume

remained lower than the levels during winter months in prior years.

36

Figure 6.1. Outpatient visit trends in 2020

Change in U.S. Outpatient Visits Compared with Baseline Week of March 1, 2020

Source: Ateev Mehrotra et al., The Impact of COVID-19 on Outpatient Visits in 2020: Visits Remained Stable, Despite

a Late Surge in Cases (Commonwealth Fund, Feb. 2021).

Data on hospitalizations in Oregon also showed sharp reductions in April 2020 (as

shown in Figure 6.2). Hospital inpatient discharges were down 34% in April 2020

compared with January 2020. In March 2022, there were about 26,700 inpatient

discharges statewide, which was close to the number in March 2021 and about 5%

higher compared with March 2020.

37

Figure 6.2. Inpatient discharges trend in Oregon, January 2020 - March 2022

Source: Oregon Health Authority Hospital Reporting Program (2022). Hospital Financial & Utilization Dashboard.

As shown in Figure 6.3, the reduction in hospital outpatient surgery visits was even

greater, with April 2020 being 76% lower than January 2020. With the third upsurge of

COVID-19 cases in the fall of 2020, hospitals were operating at closer to full capacity. In

March 2022, there were about 18,800 outpatient surgeries statewide, which was slightly

lower than March 2021 but was 54% higher compared with March 2020.

Figure 6.3. Outpatient surgeries trend in Oregon, January 2020 - March 2022

Source: Oregon Health Authority Hospital Reporting Program (2022). Hospital Financial & Utilization Dashboard.

Note: Outpatient surgeries include surgeries performed at the hospital that do not require an inpatient admission.

The 2021 Survey of Dental Practice by the American Dental Association showed that

due to the pandemic in early 2020, hours worked declined by about 17% and net

38

incomes declined by about 18% for general practitioners compared to 2019. Dental

specialists’ hours worked declined by about 12% and net incomes declined by about

7%. The COVID-19 Economic Impact on Dental Practices survey showed that as of

December 2021, about 47% of practices in Oregon were open but had lower patient

volume than usual.

Impacts of COVID-19 on the Health Care Workforce

The COVID-19 pandemic has had direct impacts on the health care workforce.

According to the Oregon Health Authority’s (OHA) COVID-19 Report, there had been

about 9,500 reported cases of COVID-19 among health care workers in 2020 and 9,900

cases in 2021. The pandemic exacerbated health care workforce burnout to an alarming

level (see the Workforce Resiliency section). The reductions in health care visits and

revenues also led to layoffs. The impacts of COVID-19 on reduced health care

employment were greatest during the first months of the pandemic.

States took a variety of actions to address health care workforce needs, including

recruiting additional health workers from within and out-of-state, modifying licensing

requirements to quickly build workforce capacity, and shifting existing staff to areas of

greater need. The state of Oregon paid for temporary staff when there were workforce

shortages in hospitals and long-term care facilities. Health care facilities greatly

increased their use of temporary staffing agencies, and the costs for temporary staff

increased dramatically. Rural communities that had long-standing problems of health

care workforce shortages were faced with exacerbating challenges during the

pandemic.

Current employment estimates from the Oregon Employment Department show a rapid

reversal of pandemic recession job losses. Within the health care sector, employment

trends varied (see Figure 7.1). Employment in ambulatory health care had bigger

declines in spring 2020, but also has had a stronger growth since then. The number of

people employed in ambulatory health care declined 17% from February to April 2020

but had rebounded to pre-pandemic levels by August 2020. Employment in ambulatory

health care in August 2022 increased by 5% compared to August 2021 and is 3%

higher than February 2020. There were slower but steadier declines in employment by

hospitals and nursing and residential care facilities. As of August 2022, the number of

people employed in hospitals and in nursing and residential care facilities were still

about 4% and 6% lower, respectively, compared to February 2020.

39

Figure 7.1. Employment trends varied within health care, January 2020 - August

2022

Source: Oregon Employment Department, Current Employment Statistics. (February 2020=100)

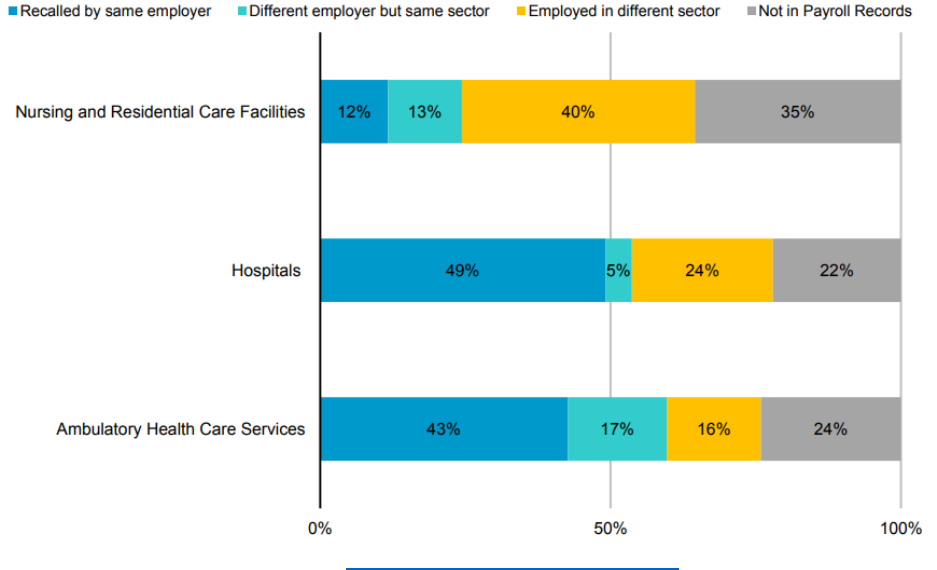

The lower employment in nursing and residential care facilities can be partly explained

by the re-employment trends reported by the Oregon Employment Department. It shows

that workers laid off from nursing and residential care facilities were far more likely to

switch sectors compared to other health care workers (Figure 7.2). Only about 25% of

former nursing and residential care workers still worked in the same sector as of winter

2022, as opposed to 54% of workers laid off from hospitals and more than 60% of

workers laid off from ambulatory care services.

75

80

85

90

95

100

105

Jan-2020

Feb

Mar

Apr

May

Jun

Jul

Aug

Sep

Oct

Nov

Dec

Jan-2021

Feb

Mar

Apr

May

Jun

Jul

Aug

Sep

Oct

Nov

Dec

Jan-2022

Feb

Mar

Apr

May

Jun

Jul

Aug

Ambulatory health care services Hospitals Nursing and residential care facilities

40

Figure 7.2. Re-employment patterns of health care workers with pandemic

unemployment claims in Oregon

Source: Oregon Employment Department, Health Care Workforce Trends in Oregon.

Figure 7.3 shows the number of monthly online health care job postings from January

2019 to September 2022 analyzed by the Oregon Employment Department. In May

2020, the number of monthly postings was about one-third lower than pre-pandemic

levels, and the number of job postings began to rebound by July 2020. There were

16,947 online health care job postings in September 2022, compared to 15,480 (a 9%

increase) in September 2021, 8,440 (a 100% increase) in September 2020, and 9,115

(an 86% increase) in September 2019. The changes in Help Wanted online postings

varied by region. Comparing September 2022 to September 2019, Clackamas and East

Cascades had more than a 110% increase in job postings, and Southwestern had only

a 21% increase.

41

Figure 7.3. Monthly online health care job postings in Oregon, January 2019 -

September 2022

Source: The Conference Board Help Wanted OnLine

TM

(HWOL), analysis by the Oregon Employment Department.

A September 2022 report on health care workforce trends in Oregon showed difficulty

filling health care vacancies, as health care occupations represented nearly 10% of job

vacancies in Oregon. About 70% of “difficult-to-fill” positions are full-time positions,

compared to 92% of “not-difficult-to-fill” positions. Education beyond high school is

required for 53% of “difficult-to-fill” positions and for 92% of “not-difficult-to-fill” positions.

A few employers in health care also reported that vaccination mandates made it harder

to fill positions, particularly in rural areas.

As many health care workers left the sector during the pandemic, hospitals competed

for contract workers to fill vacancies. A recent hospital workforce report showed that

contract labor as a percentage of total hours increased from 1% before the pandemic to

5% as of March 2022, while the contract labor as a percentage of total labor expenses

increased from 2% to 11%. Hospital labor expenses increased by more than 30% from

pre-pandemic levels. Compared to other regions, the West had the largest percentage

of using contract labor (6% of total paid hours) and the highest labor expenses (a

median of about $7,500 per adjusted discharge) as of March 2022.

4,000

6,000

8,000

10,000

12,000

14,000

16,000

18,000

20,000

Jan

2019

May

2019

Sept

2019

Jan

2020

May

2020

Sept

2020

Jan

2021

May

2021

Sept

2021

Jan

2022

May

2022

Sept

2022

42

The demand for travel nurses substantially increased as hospitalizations surged during

COVID-19 outbreaks. As COVID-19 hospitalization rates stabilized and hospitals’

financial challenges increased, demand for travel nurses dropped substantially in early

2022. There have also been state and federal moves toward regulations for staffing

agencies and limiting their pay rates. In Oregon, Senate Bill 1549 (2022) directs the

Oregon Health Authority to submit “A policy proposal and recommendations to establish

a process to determine annual rates that a temporary staffing agency may charge to or

receive from an entity that engages the temporary staffing agency.” This report will be

released by December 31, 2022.

The public health workforce was increased during the COVID-19 pandemic and many of

their current employees were redirected to focus on the pandemic. Nationally, nearly

three in four public health employees (72%) participated in the response to the COVID-

19 pandemic in some way. As of August 2021, Oregon’s local public health authority

workforce was made up of 1,143.9 FTEs for non-COVID roles. Between March 2020

and August 2021, FTE of local public health authority workforce increased 67% by

adding 761 FTE for the COVID-19 response for a total workforce of 1,905 FTE.

In summary, the COVID-19 pandemic continues to impact the health care system and

health care workforce. The workforce shortages, in addition to the omicron surge and

rising inflation, exacerbated hospitals’ financial challenges in early 2022. The financial

strains led to layoffs in the health care workforce and reduction of services in some

hospitals. Meanwhile, a study by the American Medical Association found that 2020 was

the first year in which less than 50% of patient care physicians worked in a private

practice. A report from the Physicians Advocacy Institute/Avalere Health found that

4,800 physician practices were acquired by hospitals and 31,300 were acquired by

corporate entities between January 2019 and January 2022. These findings suggest the

COVID-19 pandemic may lead to long-term changes in physician practice

arrangements, as physician group consolidations and shifts toward larger practices

have accelerated.

43

Telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic

Telehealth is a collection of means or methods for enhancing health care, public health,

and health education delivery and support using telecommunications technologies.

Telehealth includes:

• Live audio and/or video conference between patient and clinician (e.g., by

telephone or Internet)

• Store and forward (e.g., specialist reviewing x-rays at a remote location)

• Telementoring or teleconsultation between clinicians. (e.g., clinician getting

advice from an offsite specialist to support care of a patient, using technology

such as video conference)

• Remote patient monitoring (e.g., devices that monitor blood glucose levels at

home and transmit to a physician)

• Mobile health (e.g., use of mobile applications to track health information)

Telehealth played a crucial role in maintaining access to health care at the beginning of

the COVID-19 pandemic due to limitations on in-person visits; telehealth utilization

remains much higher now compared to the period before the pandemic. In the longer

term, telehealth can potentially magnify the impact of Oregon’s limited and unevenly

distributed health care workforce by allowing patients to access clinicians and other

resources outside their home city or region.

Benefits and Potential Shortcomings of Telehealth

Telehealth can be very beneficial in health care shortage areas where patients have

difficulty finding providers close to their location, as in many rural areas of Oregon.

Patients who need services in a language other than spoken English can also benefit

from telehealth if a local in-person interpreter is not available for their visit. Telehealth

can also enhance access for patients who have transportation barriers, limited access

to childcare, or difficulty getting time off work. From a provider perspective, the

California Telehealth Resource Center notes that telehealth may improve workforce

retention by allowing more clinicians to work from home or on flexible schedules.

Patients appear to be mostly satisfied with using telehealth. McKinsey found that more

than half of surveyed patients were more satisfied with telehealth than in-person, and

that four in ten expected to keep using telehealth after the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, physicians generally found telehealth less convenient for themselves and

expected telehealth utilization to decline in the future; physicians also fear that future

telehealth reimbursement will be lower than for in-person care. This suggests a

fundamental disconnect between patient preferences and physician perceptions and

preferences, which could lead to future underuse of telehealth.

44

Telehealth holds the potential either to mitigate or to worsen health inequities. The

National Association of Insurance Commissioners explain that on one hand, telehealth

may improve access for patients from disadvantaged populations, who

disproportionately face transportation challenges and live in neighborhoods with fewer

specialty clinicians. On the other hand, racial/ethnic minority, low-income, rural, or

uninsured patients are also more likely to face technological or privacy barriers to

telehealth. Patients with limited English proficiency may also not benefit from telehealth

if interpreters are unavailable or patients have difficulty hearing them.

Technological and other barriers can limit access to telehealth services. Many patients

in rural regions or low-income households lack the broadband internet access that

enables video telehealth. The Oregon Statewide Broadband Assessment and Best

Practices Study found that one in four Oregonians lived in areas that did not have high-

speed broadband Internet access in 2020. Video telehealth also requires a camera,

video display, and digital literacy, which many older or low-income patients may not

have. Lack of privacy can also prevent patients form using telehealth for sensitive

discussions. Finally, visits that require a physical examination or procedure cannot be

conducted via telehealth.

Policy Context for Telehealth

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, telehealth utilization was growing rapidly, but

accounted for only 0.1% of all medical claim lines according to FAIR Health. Payers

often restricted coverage of telehealth, including lower reimbursement rates for

telehealth versus in-person visits. Federal regulations limited the communication