CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU | OCTOBER 2023

The Consumer Credit Card

Market

2 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU – CONSUMER CREDIT CARD MARKET REPORT

Table of contents

Table of contents ..............................................................................................................2

Executive summary ..........................................................................................................4

1. Introduction ................................................................................................................8

1.1 Report mandate ......................................................................................... 8

1.2 Data sources ............................................................................................. 10

1.3 Definitions.................................................................................................12

2. Market dynamics......................................................................................................15

2.1 Cardholders...............................................................................................15

2.2 Issuers ...................................................................................................... 18

2.3 Co-brand partners ................................................................................... 25

2.4 Networks .................................................................................................. 27

2.5 Debt collectors ......................................................................................... 28

3. Use of credit .............................................................................................................31

3.1 Purchase volume .......................................................................................31

3.2 Debt levels ................................................................................................ 33

3.3 Repayment ............................................................................................... 36

3.4 Non-payment ........................................................................................... 45

4. Cost of credit ............................................................................................................48

4.1 Total cost of credit ...................................................................................49

4.2 Interest ..................................................................................................... 52

4.3 Fees........................................................................................................... 62

4.4 Net cost of credit ......................................................................................68

3 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU – CONSUMER CREDIT CARD MARKET REPORT

4.5 Rewards earned .......................................................................................69

4.6 Persistent debt ..........................................................................................71

5. Availability of credit ................................................................................................74

5.1 New accounts ........................................................................................... 74

5.2 Existing accounts ..................................................................................... 87

6. Practices of credit card issuers ............................................................................98

6.1 Rewards....................................................................................................98

6.2 Installment plans ................................................................................... 106

6.3 Balance transfers .................................................................................... 115

6.4 Cash advances ......................................................................................... 119

6.5 Over-limit transactions.......................................................................... 124

6.6 Dispute resolution ..................................................................................125

6.7 Account servicing ................................................................................... 129

6.8 Debt collection ........................................................................................ 141

7. Innovation ...............................................................................................................159

7.1 Innovations discussed above ................................................................. 159

7.2 Additional developments....................................................................... 165

7.3 Credit card competitors ..........................................................................172

4 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU – CONSUMER CREDIT CARD MARKET REPORT

Executive summary

This study represents the CFPB’s sixth biennial report on the state of the consumer credit card

market and continues the approach of the CFPB’s previous reports. The CFPB revisits similar

baseline indicators to track key market developments and consumer risks as well as the

adequacy of consumer protections. Throughout this report, we continue to examine trends by

card type and credit score tier, but further segment consumers with the highest scores into two

new groups, prime plus (720 to 799) and superprime (800 and above). In a new section, this

report examines the market dynamics, concentration, and profitability of the credit card

industry in detail, complementing other regulators’ examination of the safety and soundness of

card issuers. We explore new topics that have become more important as the market continues

to evolve. For example, the current report explores the prevalence and cost of installment plan

features and the dollar value of credit card rewards. Additionally, we discuss issuer practices

related to dispute resolution, minimum payments, and servicemember rate reductions.

• Use of credit: Credit card debt at the end of 2022 surpassed $1 trillion for the first time

in our data, but total outstandings remain below pre-pandemic levels when adjusted for

inflation. Spending grew to new highs of $846 billion in the fourth quarter of 2022. At

the same time, total payments rose, and cardholders paid significantly more of their

monthly balances with a greater share of accounts entirely paid off each month.

Delinquency and charge-off rates in 2022 were at lower levels than 2019 but increasing,

presumably rising with the expiration of COVID-19 related financial relief.

• Overall market size and structure: Nearly 4,000 issuers, together with dozens of

co-brand merchant partners and four major networks, provide cards to over 190 million

consumers. The top ten credit card issuers still represent over four-fifths of consumer

credit card loans, but the next 20 biggest issuers’ market share has grown since 2016.

• Competition and profitability: For companies involved in credit card issuance,

servicing, and debt collection, the industry remains profitable. Issuers’ profitability fell in

2020 but spiked in 2021 and remained at or above 2019-levels in 2022 with an average

return on assets of six percent for general purpose cards and two percent on private label

portfolios. Point-of-sale; Buy Now, Pay Later (BNPL); and fintech personal loans as well

as “pay-by-bank” options increasingly compete with traditional credit cards for purchase

volume and balances.

• Cost of credit: By some measures, credit cards have never been this expensive, as

issuers charged more than $130 billion in interest and fees in 2022 alone. By the end of

2022, interest and fees as an annualized percentage of balances, or the total cost of

5 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU – CONSUMER CREDIT CARD MARKET REPORT

credit, was almost 18 percent on general purpose cards and over 21 percent on private

label accounts. Many cardholders with subprime scores are now paying 30 to 40 cents in

interest and fees per dollar borrowed each year. Federal Reserve rate increases triggered

upward repricing on most general purpose cards, and issuers continue to price well

above the prime rate, with an average annual percentage rate (APR) margin of 15.4

percentage points. Fee volume now exceeds pre-pandemic levels. Annual fees grew in

2021 and 2022, while late fees returned to 2019 levels at $14.5 billion as did the

cardholder cost of balance transfers and cash advances.

• Rewards: The dollar value of rewards earned by general purpose cardholders exceeded

$40 billion for mass market issuers in 2022. Transacting accounts, or those where the

cardholder pays the full statement balance each month, are increasingly benefitting from

credit card use. But, when a consumer revolves a balance on their credit card, the cost of

interest and fees almost always exceeds the value of rewards the consumer may have

earned. Cardholders’ rewards redemptions have increased, but consumers still forfeit

hundreds of millions of dollars in rewards value each year.

• New features and products: Installment plan features which permit cardholders to

convert a credit card purchase to a lower-cost, fixed-rate loan comprise a small but

growing segment of the market designed to compete with BNPL. These issuer plans often

offer lower finance charges than on revolving debt, but consumers may struggle to make

higher monthly payments. “Credit card-as-a-service” platforms from fintechs to

traditional banks have streamlined co-brand partnerships to improve user experience

and offer novel rewards with smaller retailers. Some issuers are now approving

consumers with only soft inquires on consumers’ credit reports; others are underwriting

consumers without credit scores using new datasets and modeling techniques outside

the traditional credit reporting system. Issuers are providing cardholders with more

flexible repayment terms and new payment options, including through a growing

number of digital wallets.

• Persistent debt: With the average minimum payment due increasing to over $100 on

revolving general purpose accounts in 2022, more users are incurring late fees and

facing higher costs on growing debt. We find one in ten general purpose accounts are

charged more in interest and fees than they pay toward the principal each year,

indicating a pattern of persistent indebtedness that could become increasingly difficult

for some consumers to escape. Public relief programs in 2020 and 2021 enabled some

consumers to pay down credit card balances, but the number of cardholders facing

persistent debt has begun to climb.

6 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU – CONSUMER CREDIT CARD MARKET REPORT

• Availability of credit: Most measures of credit card availability grew in 2021 and

2022 after a sharp decrease in access during 2020. Application volume for general

purpose credit cards reached a new peak in 2022, as issuers increased acquisition efforts

and consumer demand grew. For retail cards, in contrast, application volume fell from

2020 to 2022. Approval rates more than rebounded for all card types. The recent upticks

in marketing, applications, and approvals led to significant growth in credit card

originations in 2021 with even more activity in 2022. Consumers with below-prime

scores opened more than 80 million new credit card accounts in 2021 and 2022

combined compared to 63 million over the two year period from 2019 through 2020.

Total credit line across all consumer credit cards increased to over $5 trillion in 2022 but

remained below 2017 levels in real terms. After declining in 2020, issuers initiated credit

line increases more frequently in 2021 and 2022 than they did prior to the pandemic but

decreased lines or closed accounts at rates similar to those seen over the past decade.

• Disputes: Credit card disputes spiked with pandemic-related cancellations and supply

chain issues in mid-2020, declined in 2021, but then rose in 2022 as spending grew.

Disputed transaction volume for mass market issuers was up 50 percent from 2019 levels

to almost $10 billion in 2022, and chargebacks increased more than 80 percent from

$3.2 billion to $5.9 billion.

• Account servicing: Cardholders increasingly use and service their cards through

digital portals, including those accessed via mobile devices. Three in four general

purpose accountholders are now enrolled in issuers’ mobile apps, and adoption is

increasing, notably for those under 65. The use of automatic payments has likewise

continued to climb. New artificial intelligence (AI)/machine learning (ML) technologies

are changing how providers service accounts, but concerns regarding the use and sharing

of consumer data remain significant, particularly among older cardholders.

• Debt collection: Compared to prior surveys, the use of email in collections continued

to increase in 2022, with consumers opening about one-third of messages. Issuers

seemed to leverage the text messaging (or SMS) channel significantly more in 2022 than

in prior years with a relatively low opt-out rate at 1.3 percent. New enrollments in loss

mitigation programs and total inventory in those programs declined. Post-charge-off

settlements fell significantly from their previous peaks during the pandemic. All issuers

who sold debt reported deleting the charged-off tradelines from credit reports upon sale,

potentially resulting in an incomplete view of consumers’ debt burden, likelihood of

default, and history in the credit reporting system.

Throughout this report, we highlight potential areas of concern in the consumer credit card

market. Given rising balances and credit costs, more cardholders may struggle to pay their

7 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU – CONSUMER CREDIT CARD MARKET REPORT

credit card bill on time, especially with amounts past-due, overlimit, or under an installment

plan added to the minimum payment due. As such, the CFPB will continue to monitor

assessments of late fees, reliance upon penalty repricing, and debt collection practices, alongside

the disclosure of minimum payments in accordance with CARD Act requirements. Issuers’

margins are increasing as they price APRs further above the prime rate, potentially signaling a

lack of price competition. Instead, companies offer more generous rewards and sign-up bonuses

to win new accounts, largely benefitting those with higher scores who pay their balances in full

each month. The CFPB will explore ways to promote comparison shopping on purchase APRs—a

major cost of credit cards that is often unknown to consumers prior to card issuance. We will

also monitor changes in rewards value if issuers look to cut costs in response to lower revenue.

We encourage new entrants—both bank and non-bank—to work on providing consumers with

more transparency, better experiences, and greater access to credit, so long as they comply with

existing consumer finance laws.

8 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU – CONSUMER CREDIT CARD MARKET REPORT

1. Introduction

In 2009, Congress passed the Credit Card Accountability Responsibility and Disclosure Act of

2009 (CARD Act or Act).

1

The Act made substantial changes to the credit card market. The

CARD Act mandated new disclosures and underwriting standards, curbed certain fees, and

restricted interest rate increases on existing balances.

Among the CARD Act’s many provisions was a requirement that the Board of Governors of the

Federal Reserve System (Federal Reserve Board) report every two years on the state of the

consumer credit card market. With the passage of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and

Consumer Protection Act (Dodd-Frank Act) in 2010, that requirement transferred to the

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) alongside broader responsibility for

administering most of the CARD Act’s provisions.

2

This is the sixth report published pursuant to

that obligation, building on prior reports published by the CFPB in 2013, 2015, 2017, 2019, and

2021.

3

1.1 Report mandate

As mandated by the CARD Act, this report represents the CFPB’s sixth biennial review, “within

the limits of its existing resources available for reporting purposes, of the consumer credit card

1

The Act superseded a number of earlier regulations that had been finalized, but had not yet become effective, by the

Office of Thrift Supervision (OTS), the National Credit Union Administration (NCUA), and the Board of Governors

of the Federal Reserve System. Those earlier rules were announced in December of 2008 and published in the

Federal Register the following month. See 74 FR 5244 (Jan. 29, 2009); 74 FR 5498 (Jan. 29, 2009). The rules were

withdrawn in light of the CARD Act. See 75 FR 7657, 75 FR 7925 (Feb. 22, 2010).

2

15 U.S.C. § 1616(a) (2012).

3

See CFPB, Card Act Report (Oct. 1, 2013) (2013 Report), http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201309_cfpb_card-

act-report.pdf; CFPB, The Consumer Credit Card Market (Dec. 2015) (2015 Report),

http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201512_cfpb_report-the-consumer-credit-card-market.pdf; CFPB, The

Consumer Credit Card Market (Dec. 2017) (2017 Report),

https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_consumer-credit-card-market-report_2017.pdf; CFPB, The

Consumer Credit Card Market (Aug. 2019) (2019 Report),

https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_consumer-credit-card-market-report_2019.pdf; CFPB, The

Consumer Credit Card Market (Sep. 2021) (2021 Report),

https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_consumer-credit-card-market-report_2021.pdf. The CFPB

also held a conference in 2011 on developments in the credit card market. See Press Release, CFPB, CFPB Launches

Public Inquiry on the Impact of the Card Act (Dec. 19, 2012), https://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-

us/newsroom/consumer-financial-protection-bureau-l aunches-public-inquiry-on-the-impact-of-the-card-act.

9 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU – CONSUMER CREDIT CARD MARKET REPORT

market.”

4

As was true in the CFPB’s previous reports, it addresses the following topics explicitly

enumerated by Congress for inclusion in this review:

1. the terms of credit card agreements and the practices of credit card issuers;

2. the effectiveness of disclosure of terms, fees, and other expenses of credit card plans;

3. the adequacy of protections against unfair or deceptive acts or practices relating to credit

card plans; and

4. whether or not, and to what extent, the implementation of this Act and the amendments

made by this Act have affected:

a. the cost and availability of credit, particularly with respect to non-prime

borrowers;

b. the safety and soundness of credit card issuers;

c. the use of risk-based pricing; or

d. credit card product innovation.

5

The CARD Act also requires the CFPB to “solicit comment from consumers, credit card issuers,

and other interested parties” in connection with its review.

6

As in past years, the CFPB has done

so through a Request for Information (RFI) published in the Federal Register, and we discuss

specific evidence or arguments provided by commenters throughout the report.

7

4

Reference in this report to any specific commercial product, service, firm, or corporation name is for the information

and convenience of the public and does not constitute endorsement or recommendation by the CFPB. The CFPB

notes that many players in the credit card industry are also entities with which the CFPB has one or more

institutional relationships, such as a research partnership or membership on a CFPB-convened body.

5

15 U.S.C. § 1616(a) (2012). While this report presents information which may be relevant to assessments of safety

and soundness issues relating to credit card issuers, the CFPB does not produce any further analysis on this subject

in this report. The prudential regulators (e.g., the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, the Board of Governors

of the Federal Reserve System, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and the National Credit Union

Administration) have the primary responsibility for monitoring the safety and soundness of financial institutions.

6

15 U.S.C. § 1616(b) (2012).

7

Request for Information Regarding Consumer Credit Card Market, 88 FR 5313 (Jan. 27, 2023).

10 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU – CONSUMER CREDIT CARD MARKET REPORT

1.2 Data sources

This report leverages several data sources, including:

1. The CFPB’s Consumer Credit Panel (CCP): a comprehensive, national 1-in-48

longitudinal sample of de-identified credit records maintained by one of the three

nationwide consumer reporting agencies. These data contain no personal identifiers,

such as name, address, or Social Security number;

8

2. The Federal Reserve Board’s “Y-14M” (Y-14) Data Collection: monthly portfolio- and

account-level data from bank holding companies that have total consolidated assets of

$100 billion or more.

9

The de-identified account-level data received by the CFPB cover

the period from the middle of 2012 through the present and accounted for just under 70

percent of outstanding balances on consumer credit cards as of year-end 2022;

10

3. Data provided in response to two distinct sets of filing orders:

a. Mass Market Issuer (MMI) Data: summary data requested from a group of major

credit card companies covering topics included in neither the CCP nor Y-14, such

as applications, approvals, rewards, disputes, account servicing, debt collection,

and other issuer practices;

b. Specialized Issuer Data: summary data requested from a diverse group of issuers

that in places supplement the Y-14 to allow for a broader or more detailed

perspective into credit card usage and cost for specific facets of the market.

8

Other CFPB products, such as Consumer Credit Trends reports, rely on these data.

9

See Bd. of Governors. of the Fed. Rsrv. Sys., Reporting Forms FR Y-14M,

https://www.federalreserve.gov/apps/reportingforms/Report/Index/FR_Y-14M (last accessed Jan. 11, 2023) for

more information on the Y-14M collection. Information in the Y-14 data do not include any personal identifiers.

Additionally, accounts associated with the same consumer are not linked across issuers. The Y-14 does not include

transaction-level data. In addition, this study reports only aggregate measures and reveals no information about any

specific issuer. These data replace loan-level credit card data collections the CFPB previously collected. The CFPB no

longer requires or oversees the collection of any loan-level credit card data on an ongoing basis.

10

The Federal Reserve Board has expanded the fields it collects from bank holding companies over time and has

changed the asset threshold for submission from $50 billion to $100 billion since the collection began; therefore,

some results reported below do not extend all the way back to 2012. Additionally, these data are periodically revised

retroactively, and are therefore not fully static. These issuers represent a large portion of the market but are not

necessarily representative of the portion of the market not covered by the data the CFPB receives. The remainder of

the market, representing a substantial number of consumer credit cards, are outside the scope of the Y-14 data used

by the CFPB because, among other reasons, they are issued by banks owned by bank holding companies with assets

of less than $100 billion, or are issued by non-banks, such as credit unions. Results reported from Y-14 data

throughout this report should be interpreted accordingly.

11 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU – CONSUMER CREDIT CARD MARKET REPORT

Where these data supplement Y-14 data, those data are collectively called “Y-

14+;”

11

4. The CFPB’s Quarterly Credit Card Agreement Database: a quarterly collection of most

credit card agreements available to consumers as submitted by issuers with 10,000 or

more accounts as of the last business day of the calendar quarter;

12

5. RFI Comments: 2,936 comments in response to a Federal Register notice addressing all

aspects of the review described in Section 1.1 above. 2,728 were submitted as part of a

consumer campaign that wrote, “I support the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s

work reviewing the work of Credit Card companies and reining in abusive practices. I’ve

had my own bad experiences, and I’m grateful that the CFPB is fighting for me.” 208

were not submitted as part of that campaign. Of the substantive, credit-card related

comments that were either not part of the campaign or went beyond the campaign’s

language, 369 were submitted by individual consumers, nine by consumer advocacy

organizations, eight by trade groups, five by credit unions, one by a government

organization, one by an academic, one by a debt collection agency, one by a fintech, and

two in an “other” category;

6. The CFPB’s Consumer Complaint Database: a compilation of complaints on credit cards

that consumers have submitted to the CFPB’s Office of Consumer Response;

13

and

7. Third-Party Sources: commercially available or public sources that focus on the credit

card industry, including mail volume monitoring reports, industry analyst reports,

Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) filings, studies and data produced by other

regulators, academic scholarship, and the press. When adjusting data to account for

11

The Y-14 data cover a large but not representative portion of the credit card market. The Y-14+ data cover a larger

and more representative portion of the credit card market, but the remaining uncovered portion is still substantial,

and the Y-14+ data should similarly not be considered representative of that uncovered portion.

12

12 CFR 1026.58(c)(5). The database contains most credit card agreements as of quarter’s end from the third quarter

of 2011 to the fourth quarter of 2014, and from the first quarter of 2016 to present. After the fourth quarter of 2014,

the CFPB temporarily suspended collection of agreements for one year while the CFPB developed a more

streamlined and automated electronic submission system. Submission and publication resumed in the first quarter

of 2016. 80 FR 21153 (Apr. 17, 2015); 12 CFR 1026.58(g). Agreements in the second quarter of 2019 are incomplete

due to technical submission issues at the CFPB, and agreements in 2020 and 2021 may include omissions due to the

CFPB’s previous COVID-19 regulatory flexibility statement, see CFPB, Statement on Supervisory and Enforcement

Practices Regarding Bureau Information Collections for Credit Card and Prepaid Account Issuers (Mar. 26, 2020),

https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_data-collection-statement_covid-19_2020-03.pdf.

13

CFPB, Consumer Complaint Database, https://www.consumerfinance.gov/data-research/consumer-comp laints/

(last accessed June 27. 2023).

12 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU – CONSUMER CREDIT CARD MARKET REPORT

inflation, we use the Consumer Price Index (CPI) for all urban consumers from the

Bureau of Labor Statistics.

14

The limitations inherent to the CFPB’s methodology in this report are substantially similar to

those inherent in the CFPB’s previous reports on the credit card market.

15

All results reported

from data throughout this report aggregate results from multiple industry participants. Each

source has particular limitations, as not all data rely upon consistent definitions or cover the

same periods, products, or phenomena. Additionally, the available data generally do not allow

for definitive identification of causal relationships. Accordingly, correlations presented

throughout this report do not necessarily indicate causation.

1.3 Definitions

This subsection defines certain additional terms used frequently throughout this report. This is

not exhaustive of all remaining defined terms in this report; for example, other defined terms

more particular to certain sections or subsections of this report are introduced in those sections

or subsections.

Throughout this report, the CFPB refers to consumer credit scores. Lenders typically determine

consumers’ credit eligibility and pricing using credits scores based on data from major national

consumer reporting agencies alongside other data sources. When reporting results by credit

scores in this report, scores are generally grouped into six tiers: superprime (800 or greater),

prime plus (720 to 799), prime (660 to 719), near-prime (620 to 659), subprime (580 to 619),

and deep subprime (579 or less).

16

Previous reports only used five tiers as they did not break out

the prime plus category. Using six tiers better captures differences in cost, use, and availability

for the almost two-thirds of cardholders with scores greater than 720. Where historical data are

used or in places with limited coverage of cardholders with scores below 620, fewer than six

credit score tiers may be represented.

Data relied upon in this report include widely used, commercially available credit scores, but as

issuers use different credit scores,

17

a given account’s “credit score tier” may differ from bank to

14

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers, https://www.bls.gov/cpi/ (last

accessed June 27, 2023).

15

See, e.g., 2015 Report, at 27.

16

See Section 2.1 for the distribution of cardholders by credit score tier.

17

It is also typical for lenders to supplement commercially-available scores with proprietary models to assess an

account’s creditworthiness.

13 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU – CONSUMER CREDIT CARD MARKET REPORT

bank. Different credit score models, while fundamentally similar, may include or exclude

different information or weight data differently when predicting a consumer’s relative likelihood

of default. Credit scores in the CCP and Y-14 are updated regularly. Unless noted otherwise,

accounts and consumers are classified into tiers based on their credit scores at that point in

time; therefore, the number of observations in a tier change over time. The CFPB believes that

different credit scoring methodologies, over the time periods and set of market participants

examined in this report, are sufficiently consistent to remain informative and useful to report

aggregate results and changes over time by credit scores.

18

Outstandings, or the nominal amount owed by consumers on a specific date, is one method for

measuring consumer credit card indebtedness. A second method entails measuring balances, or

the amount owed by consumers at the end of their billing cycle, within a given month. This

report uses the term “debt” to refer to both of these amounts interchangeably.

The flexibility in use and repayment of credit cards leads to two types of credit card debt.

Consumer credit card debt includes both “revolving” debt—the amount owed on accounts for

which a positive cycle beginning balance was not paid in full by the statement due date—and

“transacting” debt—the amount owed on accounts for which the non-zero, non-negative balance

was paid in full by the statement due date. Most credit cards provide a grace period where, if a

cardholder does not carry a balance, they will not accrue interest prior to the due date.

Therefore, revolving debt typically bears interest starting from the date of purchase while

transacting debt under a grace period does not. Cardholders at any given point can be classified

as a “revolver” or a “transactor” based on whether they pay their statement in full each month.

Throughout this report, we refer to different, and at times overlapping, types of credit cards

when describing the market:

• “General purpose” cards are those that transact over a network accepted by a wide

variety of merchants;

• “Private label” cards can only be used at one merchant or a small group of related

merchants and lack network branding;

19

18

See 2021 Report, supra note 3, at 20.

19

Private label cards generally transact over a private network maintained by the issuer to which the merchant is

granted access. Some cards can transact over both a private label network and a general purpose network. For

example, a consumer may be issued a card that features a merchant’s brand as well as a general purpose network

brand. When used at the merchant, the transaction may be routed over the issuer’s private network, but at other

merchants the transaction is routed over the general purpose network. For the purposes of this report, those cards

are considered to be general purpose credit cards except where explicitly noted otherwise.

14 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU – CONSUMER CREDIT CARD MARKET REPORT

• “Co-brand” cards are a subset of general purpose cards that include both the badge of a

network and branding of a specific merchant such as a retailer, airline, or hotel chain;

and

• “Retail” cards are a combined category of both private label cards and some general

purpose, co-brand cards managed by a business unit that specializes in credit cards

offered in partnership with specific merchants. Retail cards do not include network-

branded cards that carry hotel or airline branding, even if those cards are managed by a

business unit that specializes in retail credit cards. In some sections, data related to co-

brand cards managed by a retail unit are not included in general purpose totals, as noted.

15 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU – CONSUMER CREDIT CARD MARKET REPORT

2. Market dynamics

This new section of the report describes players in the consumer credit card market. This report

generally focuses on the state of the consumer credit card market through the lens of

cardholders; therefore, this section first establishes the number of consumers with at least one

credit card. Then, it addresses issuers as the provider of credit and primary point of contact for

consumers by detailing the breadth and concentration of the market for credit card issuance, as

well as issuer profitability. By examining portfolio-level revenue and expenses, we establish a

foundation on which to analyze credit card market competition and innovation moving forward.

However, issuers are not the only companies in the credit card payments ecosystem. As such,

this chapter also describes the role of merchant partners in offering co-brand credit cards and

concludes with an overview of card networks and the credit card debt collection industry.

2.1 Cardholders

The CFPB estimates that 190.6 million of the 258.3 million adults in the United States (74

percent) had a credit card account in their name as of the end of 2021.

20

Around 90 million

consumers hold only a general purpose credit card, 10 million hold only a private label card, and

90 million have at least one of each. The share of consumers with credit cards differs by credit

score and age over time.

20

This estimate is according to coverage of credit records present in the CCP sample, though it does not include

authorized users, who are individuals designated by the primary accountholder to use the same credit account. For

the number of adults in the United States, we rely upon data from the 2020 census. See United States Census

Bureau, U.S. Adult Population Grew Faster Than Nation’s Total Population From 2010 to 2020 (Aug. 2021),

https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/08/united-states-adult-population-grew-faster-than-nations-total-

population-from-2010-to-2020.html. A recent report from the Federal Reserve finds 82 percent of consumers report

having at least one credit card. See Federal Reserve Board, Report on the Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households

in 2022, at 44 (May 2023), https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/2022-report-economic-well-being-

us-households-202305.pdf. Throughout this report, some statistics are about three percent different compared to

what is reported in the 2021 Report, due to revisions to the data and methodology.

16 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU – CONSUMER CREDIT CARD MARKET REPORT

TABLE 1: CONSUMERS BY CARDHOLDING BEHAVIOR, YEAR-END 2021 (CCP)

Credit score

tier

General

purpose

card(s) only

Private label

card(s) only

At least one

of each

No credit

card

Superprime 21.7M 0.5M 26.0M 0.1M

Prime plus 36.0M 3.8M 32.4M 6.9M

Prime 12.7M 1.7M 17.1M 6.8M

Near-prime 6.8M 1.2M 7.8M 1.7M

Subprime 5.3M 1.2M 4.0M 2.1M

Deep subprime 6.2M 1.5M 3.0M 7.1M

Thin or stale

score file

21

1.4M 0.1M 0.1M 33.4M

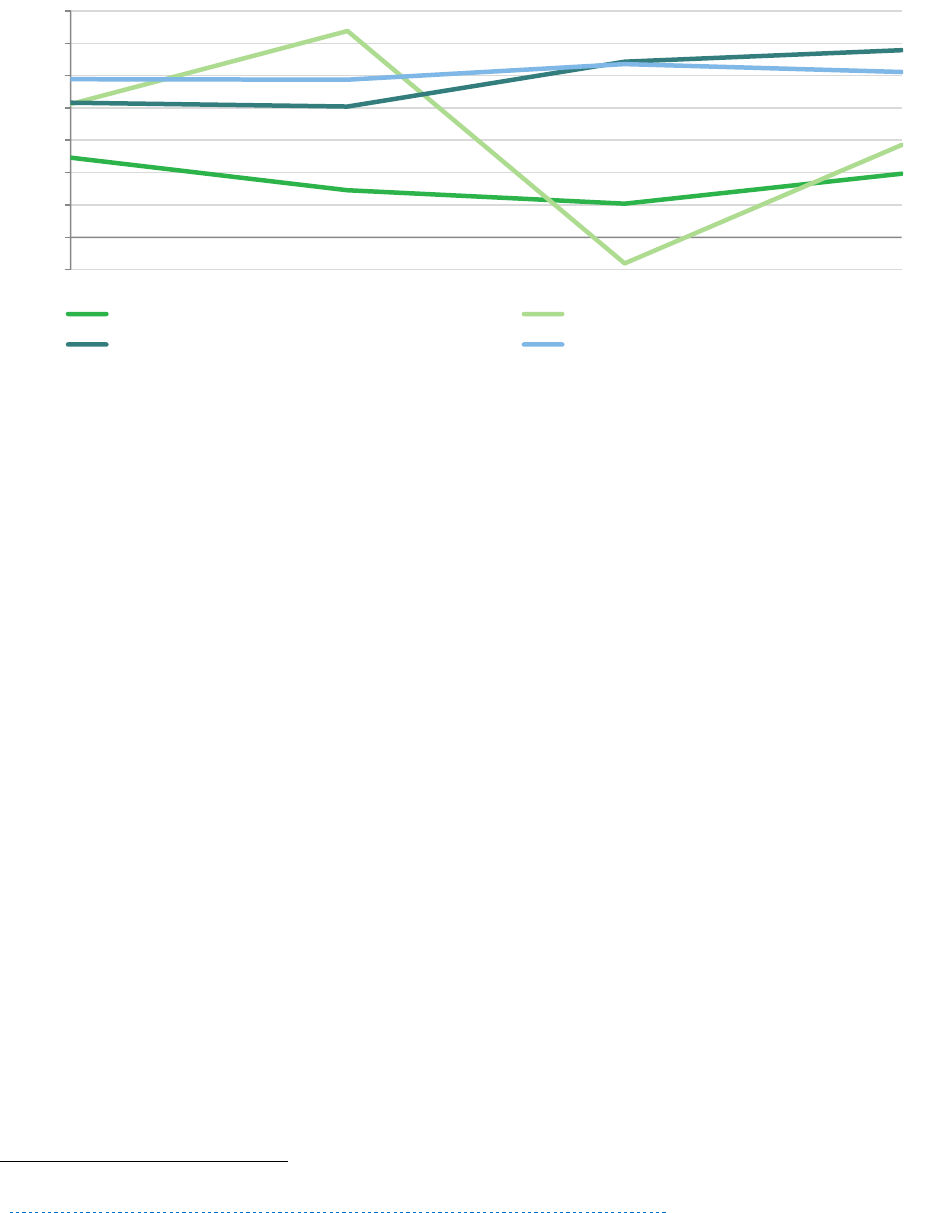

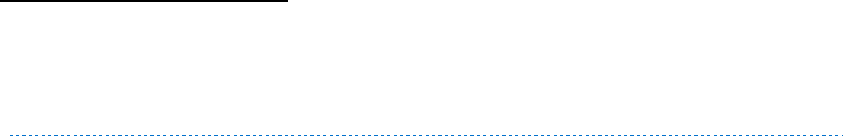

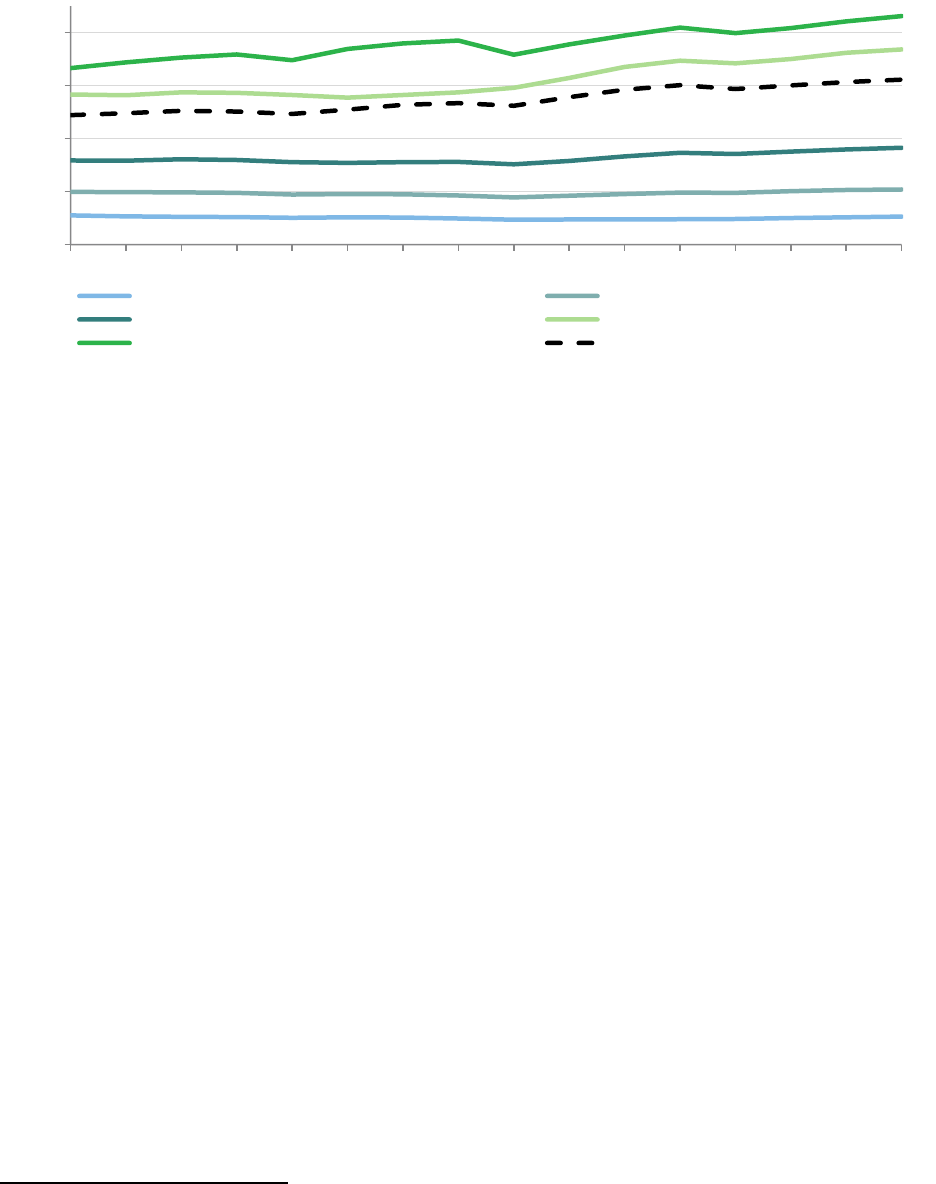

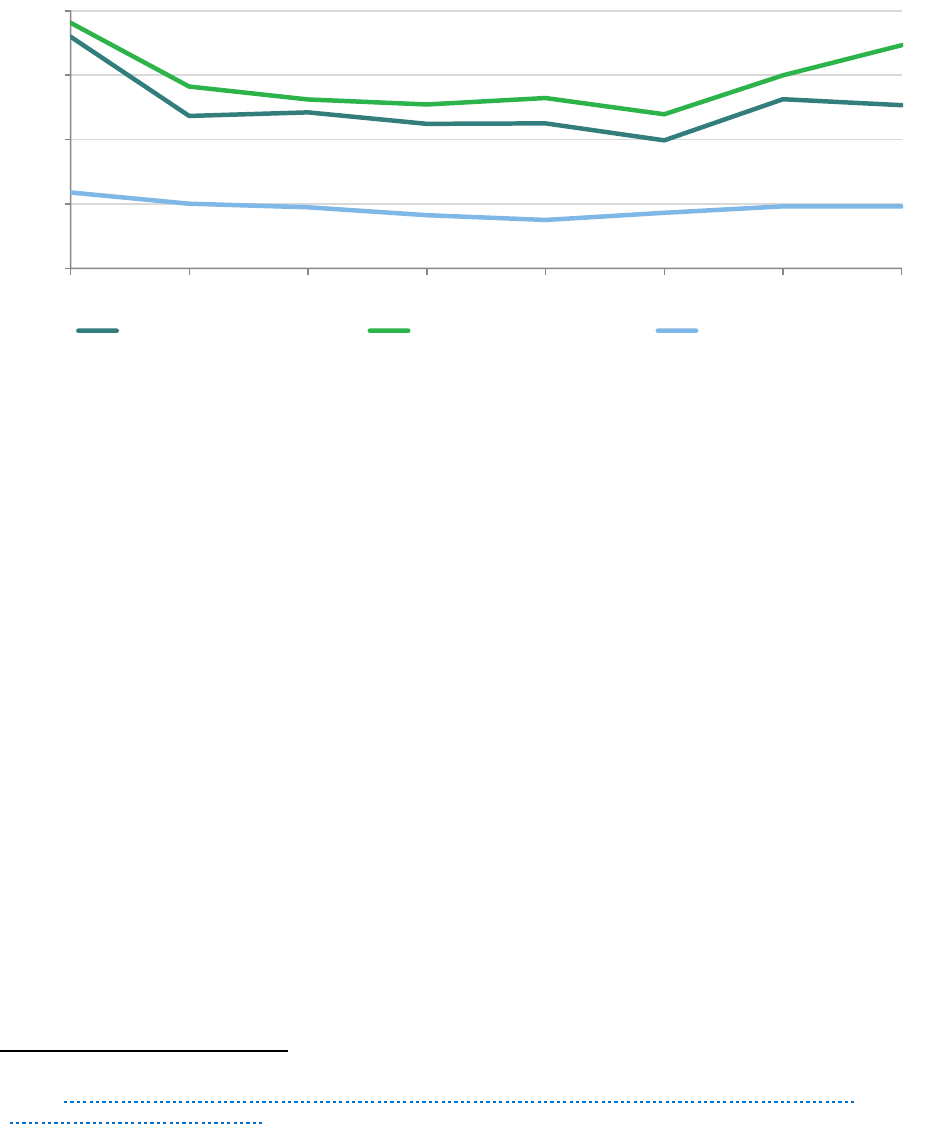

As shown in Figure 1, the share of consumers with below-prime credit scores who have at least

one credit card rebounded as the nation emerged from the pandemic. Across time, a larger share

of consumers with near-prime credit scores has credit cards than those with subprime, who in

turn are more likely to have a credit card than consumers with deep subprime credit scores.

However, as of year-end 2022, cardholding by adults with deep subprime credit scores was at its

highest level since at least 2013. All three below-prime score groups saw dips in credit card

ownership in 2020 and early 2021, but it swiftly rebounded up to or above pre-pandemic levels

in late 2021 and 2022.

21

This measure may include fragmented files.

17 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU – CONSUMER CREDIT CARD MARKET REPORT

FIGURE 1: QUARTERLY SHARE OF BELOW-PRIME CONSUMERS WITH AT LEAST ONE CREDIT CARD

(CCP)

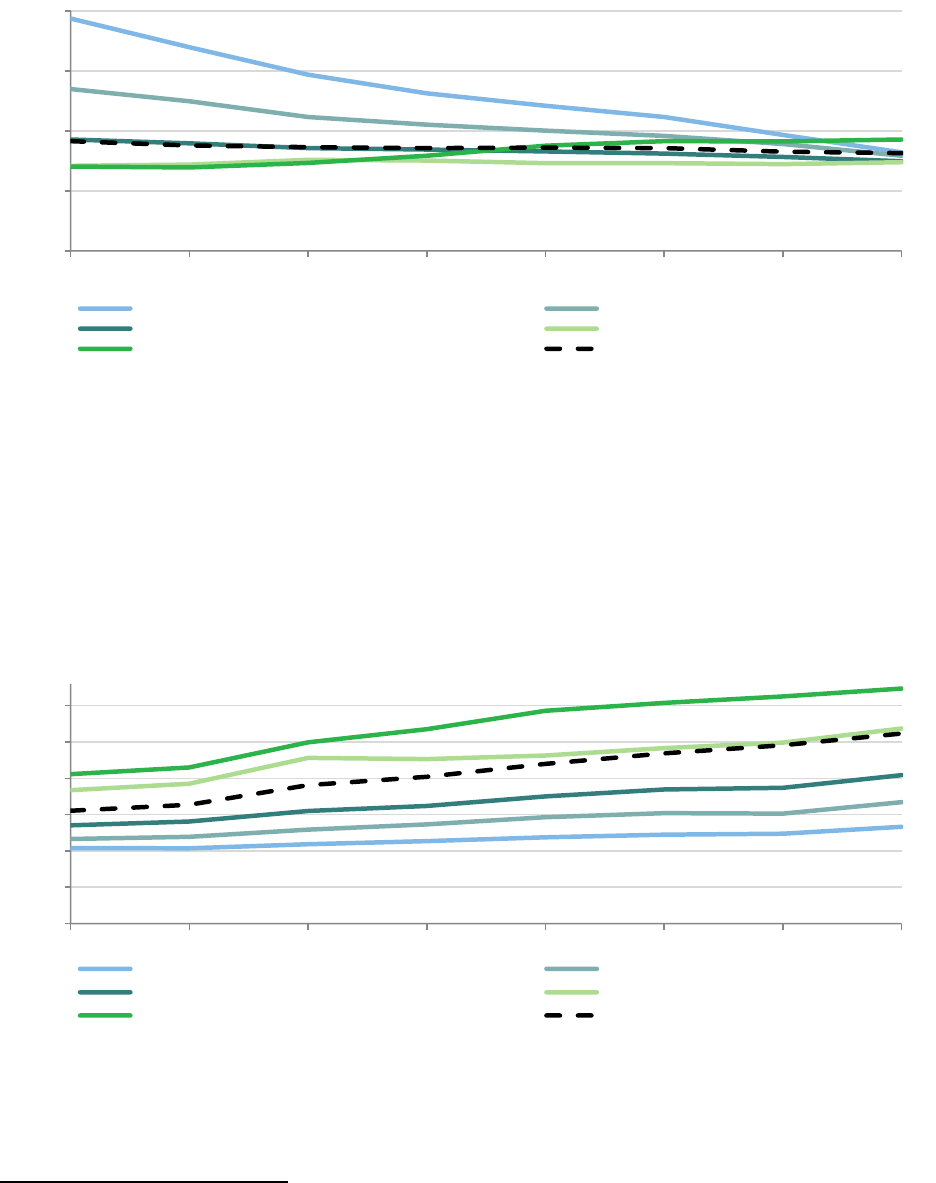

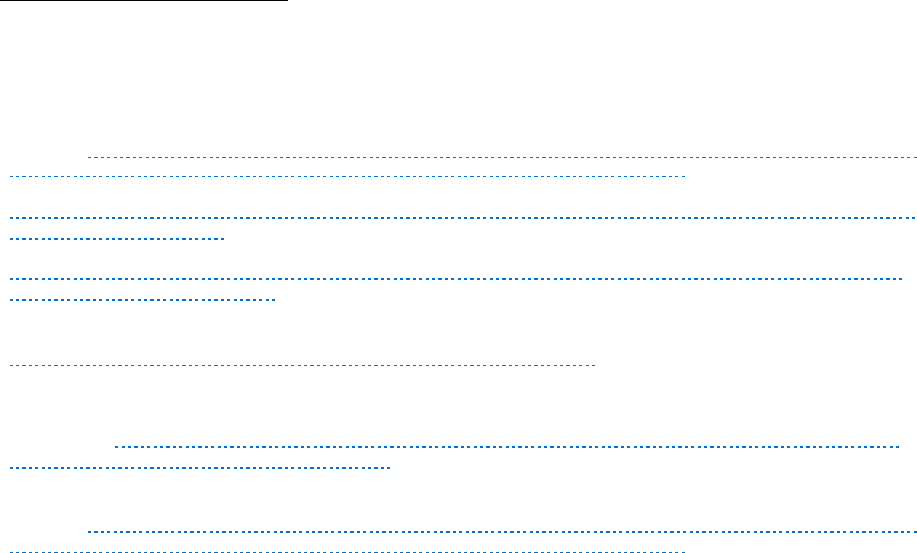

Older consumers are consistently more likely to carry a credit card, but the share of younger

consumers with a credit card has trended slightly up over the last 10 years.

22

From 2013 to

2022, on average, 88 percent of consumers over 65 had at least one credit card. In 2013 and

2014, only 56 percent of consumers aged under 25, and 76 percent of consumers aged 25 to 64

had a card. By the end of 2022, these shares had grown to 64 percent for consumers under 25

and 82 percent for consumers in the middle age range.

23

22

A consumer advocacy group wrote that older Americans face unique challenges with credit card use and access:

“Older Americans are more likely than their younger counterparts to be unable to pay or make only a partial

payment on their credit cards. Therefore, the Bureau must pay special attention to policing the use of unfair,

deceptive, or abusive practices in the credit marketplace to harm consumers within this age group. Similarly, the

CFPB must work to ensure there are responsible credit options for older consumers." See AARP comment at 3.

23

One consumer and a credit union wrote that cards should be more accessible to young people, see Mindy Cole and

Randolph-Brooks Federal Credit Union comments, but more commentors were concerned that getting a credit card,

and subsequently accumulating credit card debt, was too easy for younger borrowers, see New York City Department

of Consumer and Worker Protection at 4, Deonet Wolfe, JoEllen Rudolph, and Nancy Petranto comments.

83%

84%

84%

84%

84%

84%

84%

83%

83%

84%

62%

63%

65%

67%

67%

69%

70%

67%

68%

68%

25%

27%

30%

32%

34%

36%

37%

32%

37%

42%

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

Near-prime Subprime Deep subprime

18 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU – CONSUMER CREDIT CARD MARKET REPORT

FIGURE 2: QUARTERLY SHARE OF SCORED CONSUMERS WITH AT LEAST ONE CREDIT CARD, BY AGE

(CCP)

2.2 Issuers

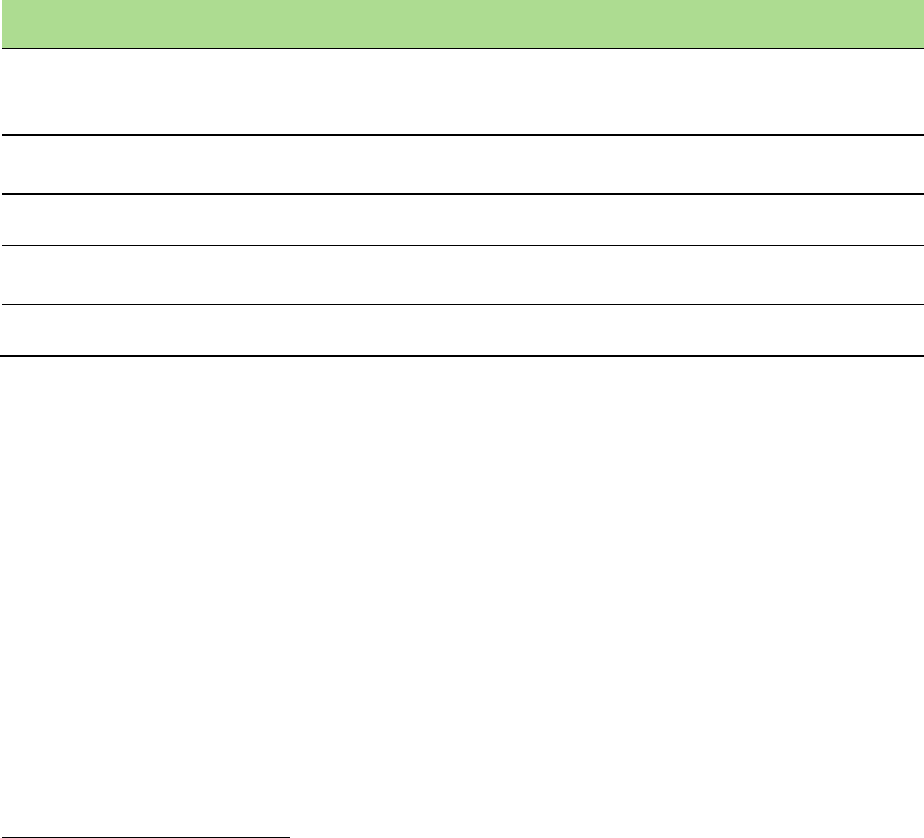

2.2.1 Concentration

About 4,000 financial institutions offer credit cards, yet a handful of issuers represent an

overwhelming majority of credit card debt.

24

The top 10 issuers by average credit card

outstandings represented 83 percent of credit card loans in 2022, continuing a decline from 87

percent in 2016.

25

The next 20 issuers by reported credit card debt accounted for 12 percent, an

increase of four percentage points over the past six years. 3,800 smaller banks and credit unions

account for the remaining five to six percent of the market. No single issuer outside the top 15

represented more than one percent of total credit card loans in regulatory filings.

24

One commentor wrote a letter arguing that the current credit card market is highly concentrated and features high

interest rates, excess returns for credit card issuers, and regular antitrust suits, see Tristan Campbell comment.

Another individual wrote that credit cards are uniquely competitive compared to other financial services, see Nick

Meyer comment.

25

Although concentration appears to have declined in recent years, fewer banks now issue credit cards and the top

banks represent a larger share of the market than twenty years ago. In 1994, about 6,000 depository institutions

issued credit cards and the top 10 largest credit card issuers held about 57 percent of loans. See GAO, U.S. Credit

Card Industry: Competitive Developments Need to Be Closely Monitored (Apr. 28, 1994),

https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GAOREPORTS-GGD-94-23/html/GAOREPORTS-GGD-94-23.htm.

56%

59%

61%

62%

63%

63%

62%

60%

63%

64%

76%

77%

78%

79%

79%

80%

80%

80%

81%

82%

89%

89%

89%

89%

88%

88%

88%

88%

88%

88%

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

Under 25 25 to 64 Over 65

19 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU – CONSUMER CREDIT CARD MARKET REPORT

FIGURE 3: ANNUAL MARKET SHARE BY AVERAGE CREDIT CARD LOANS (REGULATORY FILINGS)

26

As has been true for the past decade, credit unions represent less than one-tenth of total

outstandings, but their share of loans has grown from 6.6 percent of outstandings in 2016 to 7.3

percent in 2022.

27

Some consumers may increasingly choose to open cards at credit unions as

the Federal Credit Union Act limits APRs to a maximum of 18 percent.

28

Evidence also suggests

that smaller issuers may charge lower fees than the top banks.

29

The market for private label credit cards is more concentrated than that of the overall consumer

credit card market with fewer players representing more of the market. The top six issuers in the

private label credit card market represented 95 percent of private label outstandings in 2022.

30

26

For banks, we use data from the regulatory Reports of Condition and Income (Call Reports) on “Average Credit

Card Loans to Individuals (Include Credit Card and Related Plans).” This excludes small banks under a certain asset

threshold not required to report these data. For bank holding companies, we use “Average Consumer Loans: Credit

Cards” from holding company regulatory financials. For Credit Unions, we use “Average Unsecured Credit Card

Loans” from credit union regulatory financial statements.

27

This share includes three credit unions in the top 30 largest credit card issuers. Credit union commentors and their

trade associations wrote about the challenges they face competing with banks while serving their members. See

Credit Union National Association, NAFCU, Randolph-Brooks Federal Credit Union, CrossState Credit Union

Association, and First Service Credit Union comments.

28

See National Credit Union Administration, Permissible Loan Interest Rate Ceiling Extended (Mar. 2023),

https://ncua.gov/regulation-supervision/letters-credit-unions-other-guidance/permissible-loan-interest-rate-

ceiling-extended-

2#:~:text=The%20Federal%20Credit%20Union%20Act%20generally%20limits%20federal%20credit%20unions,int

erest%20rate%20ceiling%20on%20loans..

29

See Joanna Cohen, Lucas Nathe, László Sándor, Margaret Seikel, and Wei Zhang, Credit card late fees (Late Fee

Report), CFPB, at 15 (Mar. 2022), https://www.consumerfinance.gov/data-research/research-reports/credit-card-

late-fees/.

30

The Nilson Report, No. 1226.

87.0%

84.7%

84.4%

84.2%

83.4%

83.1%

82.9%

7.6%

9.9%

10.3%

10.4%

11.1%

11.3%

11.6%

5.4%

5.4%

5.4%

5.4%

5.5%

5.6%

5.5%

2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021

2022

0%

15%

30%

45%

60%

75%

90%

Top 10 issuers Next 20 issuers All other issuers

20 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU – CONSUMER CREDIT CARD MARKET REPORT

Notably, the use of private label cards has been declining, potentially due to increased

competition from other products.

31

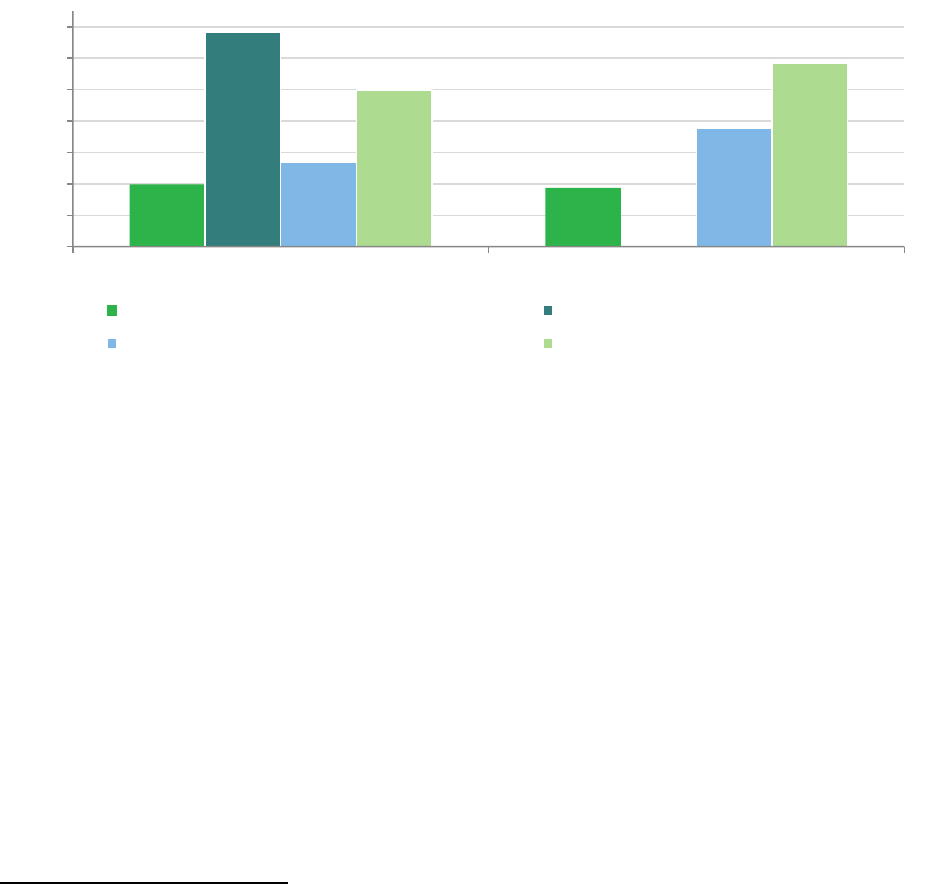

2.2.2 Profitability

Credit card issuers’ profitability is relevant to consumers, as the revenue and expenses of credit

card companies drive the cost and value of the product. The returns associated with credit card

operations consistently exceed earnings for other bank activities.

32

While banks with a credit

card business may also engage in other banking activities, this section is focused solely on the

revenue, expenses, and profitability of banks’ domestic consumer card portfolios. In this report,

we use Return on Assets (ROA) to evaluate the profitability of credit card portfolios. ROA is

equal to net income related to credit card activities divided by average credit card receivables.

Individual expense and revenue line items are expressed as a percentage of average receivables

to provide insight into how efficiently the industry manages expenses and converts balances into

revenue.

33

Although certain revenues and expenses, such as those related to interchange and

rewards, fluctuate based on purchase volume rather than outstandings, we present line items

relative to receivables for comparison purposes. The CFPB has not assessed issuer profitability

in this manner in previous iterations of this report but has examined this topic in other

publications.

34

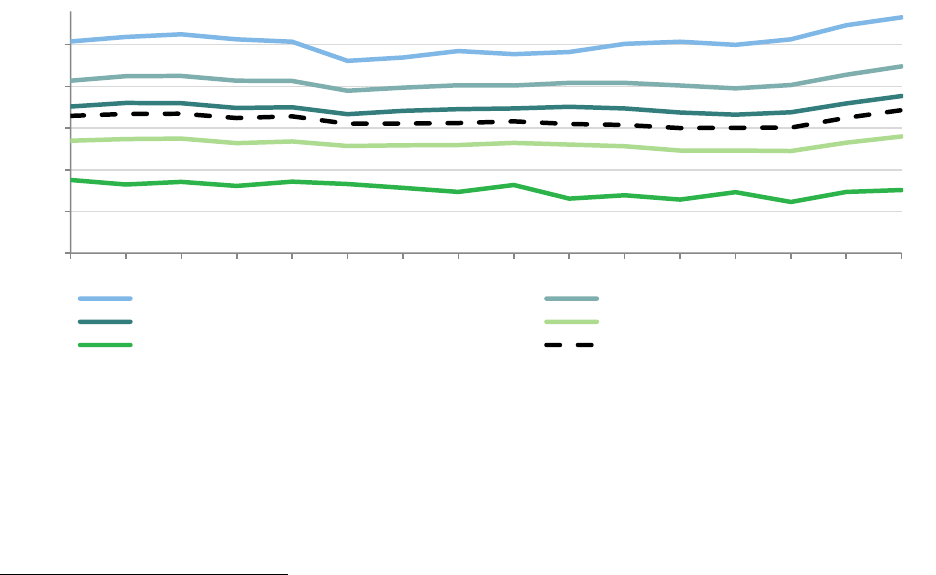

The average ROA on credit card lending activities for banks in the Y-14+ was 5.9 percent on

general purpose portfolios and 2.1 percent on private label portfolios in 2022.

35

While these

rates are similar to that observed in 2019, ROA experienced a decrease in 2020 and then a spike

31

For further discussion on debt and purchase volume by card type, see Section 3. For further discussion of

competitors, see Section 7.

32

See Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Report to the Congress on the Profitability of Credit Card

Operations of Depository Institutions (Jul. 2021),

https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/ccprofit2021.pdf

33

Although certain revenues and expenses, such as those related to interchange, fluctuate based on purchase volume

rather than outstandings, we present line items relative to receivables for comparison purposes.

34

Margaret Seikel, Examining the factors driving high credit card interest rates, CFPB (Aug 12, 2022),

https://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/bl og/examining-the-factors-driving-high-credit-card-interest-rates/.

35

This estimate is according to coverage of consumer credit card portfolios for the card issuers in the Y-14+ dataset. A

recent report from the Federal Reserve found an average ROA for the eight largest credit card banks of 4.71 percent

in 2022. See Bd. of Governors of Fed. Rsrv. Sys., Profitability of Credit Card Operations of Depository Institutions

(July 2023). A paper using the Y-14 and different groupings of portfolios found a quarterly ROA typically between 1

and 2 percent. See Robert Adams et al., Credit Card Profitability, Bd. of Governors for the Fed. Rsrv. Sys.,

(published Sept. 9, 2022, updated Apr. 20, 2023), https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/credit-

card-profitability-20220909.html. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) estimated ROA was 3.7

percent for credit card banks in 2022. See FDIC, Quarterly Banking Profile, at 12 (2023),

https://www.fdic.gov/analysis/quarterly-banking-profile/qbp/2023mar/.

21 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU – CONSUMER CREDIT CARD MARKET REPORT

the next year, largely explained by changes in loan loss provision expense.

36

The ROA on general

purpose portfolios exceeded that of private label cards for each year in our data.

FIGURE 4: ANNUAL AVERAGE RETURN ON ASSETS (Y-14+)

Net interest income is the primary driver of card issuer profitability for both general purpose

and private label cards, comprising 10.3 and 9.2 percent of receivables in 2022, respectively.

Figure 5 displays the major components of ROA as shares of credit card receivables: net interest

income, net non-interest income, and loan loss provision expense. For both portfolios, net

interest income positively affects profits, while net non-interest income and loan loss provision

expense each have a net negative impact on profits.

FIGURE 5: ANNUAL AVERAGE RETURN ON ASSETS, 2022 (Y-14+)

36

Many consumers submitted comments expressing frustration over credit card companies’ high levels of profit. See

Comment Letters submitted by Chelsea Yorkshire, Thomas Dunn, Kathi Thonet, Maureen Knutson, Diane Swann,

and Natalia Vann.

4.5%

2.3%

9.6%

5.9%

2.4%

-0.1%

5.4%

2.1%

2019 2020 2021 2022

0%

2%

4%

6%

8%

10%

General Purpose Private Label

22 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU – CONSUMER CREDIT CARD MARKET REPORT

REVENUE

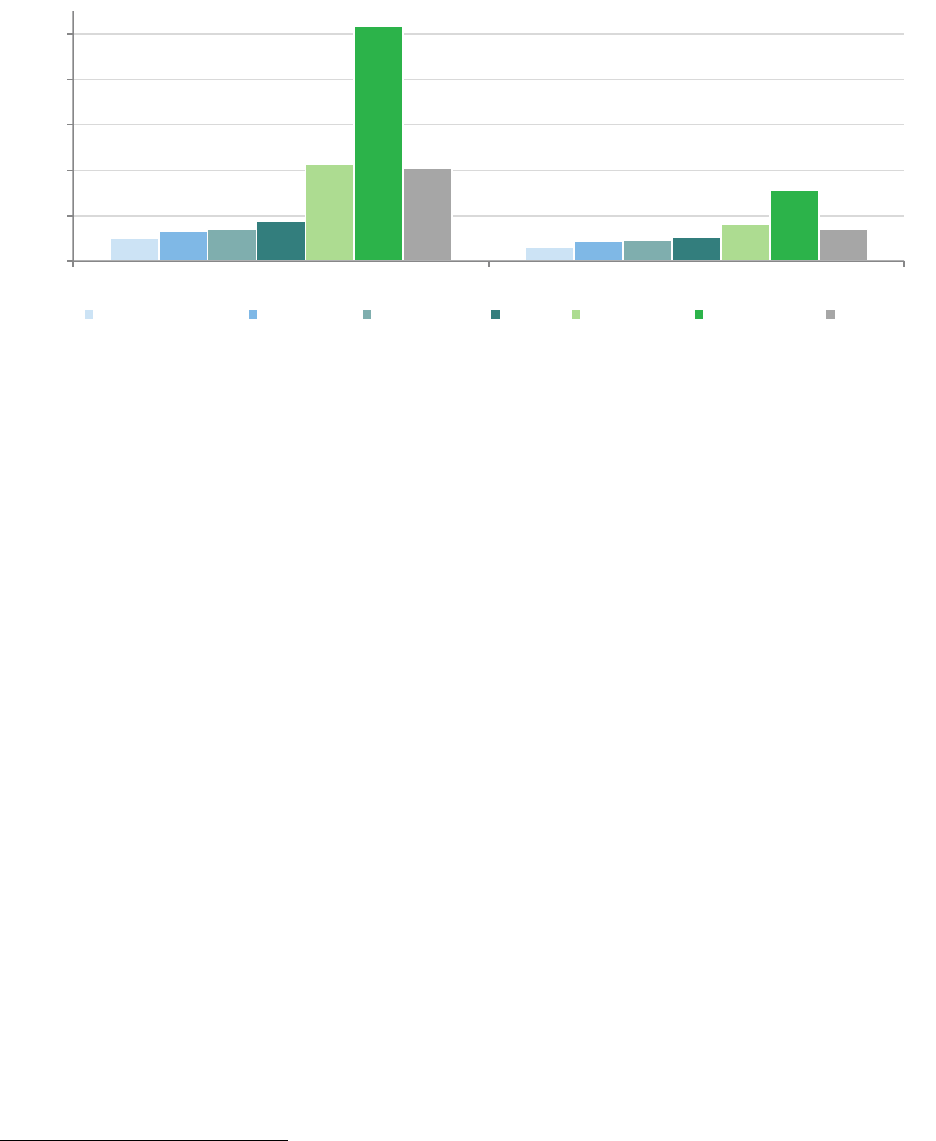

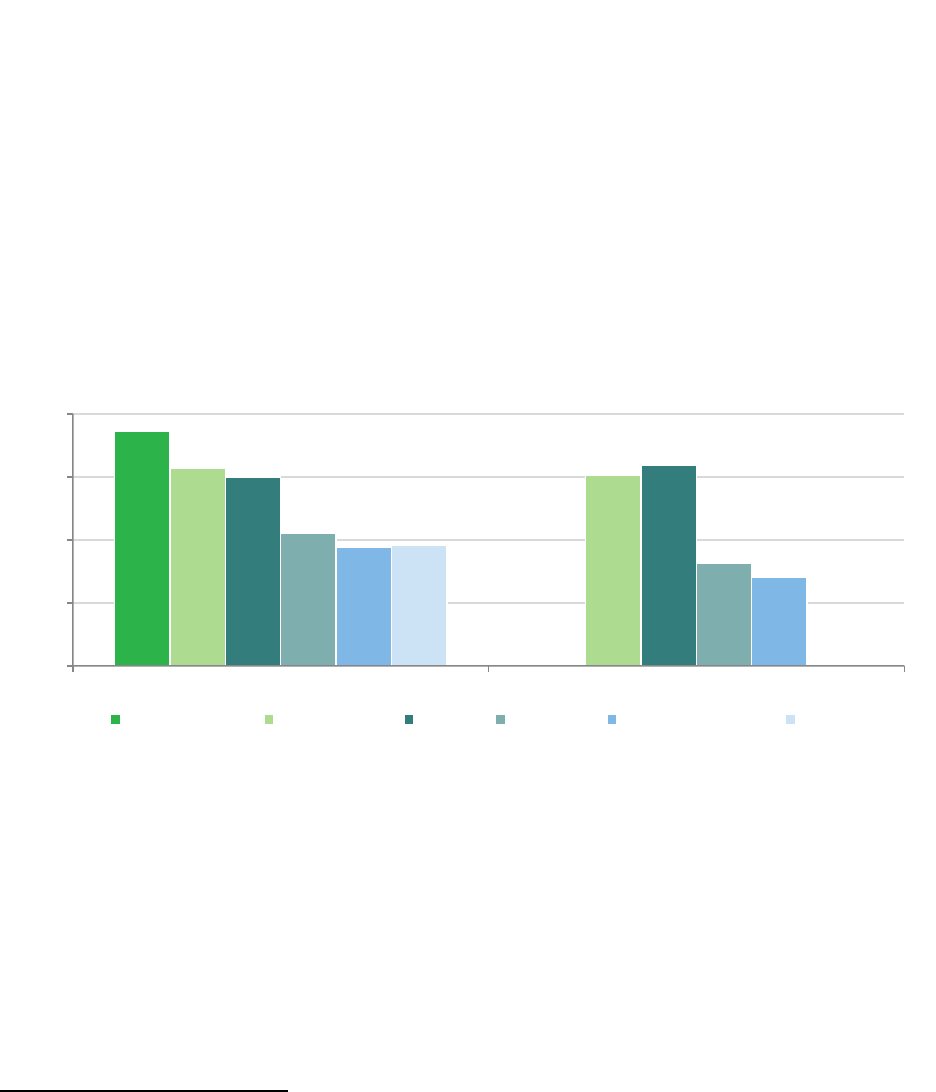

Interest income is the primary revenue source for the card portfolios of major banks.

37

Figure 6

shows that, for general purpose card issuers, the next largest line item is interchange income,

38

whereas, for private label, it is fee income.

39

Although general purpose card portfolios are less

reliant on fees than private label portfolios, fee income as a proportion of receivables is

significant for both, representing 1.5 percent and 3.9 percent of managed receivables in 2022 for

general purpose and private label cards, respectively. Interchange income has increased from six

percent of general purpose receivables in 2019 to eight percent in 2022, but it has not changed

significantly as a share of purchase volume (1.8 percent). Interchange revenue has grown

proportionally with spending and has grown faster than receivables. For private label portfolios,

multiple issuers reported negative values for “other non-interest income.”

40

While the specific

reason for negative other income varies by issuer, this phenomenon can generally be explained

by accounting adjustments, such as divesting from assets over time, which impact the reported

income but not necessarily the cash flow in and out of the company.

FIGURE 6: ANNUAL REVENUE LINE ITEMS AS A SHARE OF RECEIVABLES, 2022 (Y-14+)

37

Credit card issuers generally segment revenue into interest income and non-interest income. Interest income

includes all interest charges accrued and billed on credit card receivables while non-interest income is comprised of

revenue from interchange, penalty fees, transaction fees, and any other income associated with card operations.

38

Interchange income is fees received by the issuer from card associations, part of the merchant discount rate.

39

Private label portfolios have nearly zero interchange income because private label cards operate in a closed loop

system (i.e., are only accepted at the merchant associated with the card), so merchants and networks are generally

not required to pay interchange fees to networks on transactions.

40

Y-14 data dictionary defines other non-interest income as revenue “including annual fees, debt

suspension/cancellation product fees, etc., associated with card operations.”

12.3%

11.1%

7.9%

0.2%

1.5%

3.9%

0.6%

-1.6%

General Purpose Private Label

-2%

0%

2%

4%

6%

8%

10%

12%

Interest Income Interchange Income Fee Income Other Income

23 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU – CONSUMER CREDIT CARD MARKET REPORT

Interest income as a share of annualized receivables declined in 2021 due to the decline in

outstanding balances but returned in 2022 alongside the rebound in debt. Declines in 2021 were

more than offset by an increase in interchange revenue, as purchase volume grew in 2021 and

2022. Figure 7 shows that, despite a decline in 2020, interest income remained the primary

revenue source for combined general purpose and private label card portfolios of Y-14+ banks

from 2019 to 2022, followed by interchange income and then fees.

FIGURE 7: ANNUAL REVENUE LINE ITEMS AS A SHARE OF RECEIVABLES (Y-14+)

EXPENSE

Costs associated with rewards and interchange represented issuers’ largest expense category in

2022, exceeding all other non-interest expenses reported in the data.

41

Interchange and rewards

expense has grown over time (Figure 8), as purchase volume has increased and competition in

rewards has escalated.

42

Interest expense moved with changes in the federal funds rate,

decreasing in 2020 and 2021 then increasing in 2022. Overall, the cost of operating a card

portfolio ranged from 10 to 13 percent of managed receivables over the four years studied,

before considering loan loss provisions.

41

The CFPB does not have full insight into what a bank chooses not to report as card-related expenses, but other

operational or marketing budgets may be allocated in other parts of the balance sheet not represented here.

42

Interchange expense represents the fees issuers pay to networks, typically as a flat rate and/or percentage of

purchase volume. Interchange and rewards expense are combined in this section because issuers typically use

interchange revenue to cover the cost of both interchange expense and rewards expense. See Sections 4.5 and 6.1 and

on rewards for more information.

12.7%

11.9%

11.3%

12.1%

5.1%

4.9%

6.6%

6.8%

1.8%

1.6%

1.7%

1.8%

0.2%

0.3%

0.4%

0.3%

2019 2020 2021 2022

0%

2%

4%

6%

8%

10%

12%

14%

Interest Interchange Fees Other income

24 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU – CONSUMER CREDIT CARD MARKET REPORT

FIGURE 8: ANNUAL EXPENSE LINE ITEMS AS A SHARE OF RECEIVABLES (Y-14+)

Loan loss provision expense, reflecting the estimated losses associated with an issuer’s credit

card portfolio, fluctuated in 2020 and 2021 given two concurrent phenomena. First was the

implementation of current expected credit losses (CECL) methodology, an accounting standard

for estimating allowances for credit losses. Before 2020, banks could report credit loss reserves

based on incurred costs, which regulators say often resulted in an underestimation of potential

credit losses.

43

CECL added the requirement that banks incorporate forward-looking

information in determining their estimated provision for credit losses, as well as provisioning

for expected losses over the lifetime of accounts beginning on the date of origination. Second, at

the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, issuers increased loan loss provisions in preparation

for an economic downturn. When a widespread recession did not materialize, issuers responded

by rapidly releasing some of their loss provisions. These changes in loan loss provision expense

explain most of the variation in ROA seen in Figure 4.

Expenses differ materially between general purpose and private label card portfolios, as private

label card issuers do not typically fund rewards via interchange income. General purpose card

issuers often spend a significant portion of the interchange revenue they receive on rewards to

cardholders: interchange income less interchange and rewards expenses results in a net

interchange rate of 1.1 percent of average receivables (or 0.3 percent of annual purchase

volume). Therefore, while issuer rewards costs have gone up in recent years, general purpose

card issuers typically earn more in interchange than they spend in the form of rewards they

provide to consumers, irrespective of any additional borrowing and accrued interest the

43

See Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, Current Expected Credit Losses (Apr. 2023),

https://www.occ.treas.gov/news-issuances/bulletins/2023/bulletin-2023-11.html.

2.5%

1.5%

1.0%

2.0%

4.1%

6.4%

-0.8%

2.9%

4.2%

4.0%

5.4%

5.8%

4.9%

4.9%

5.4%

5.1%

2019

2020 2021

2022

-1%

0%

1%

2%

3%

4%

5%

6%

7%

Interest expense Loan loss provision expense

Interchange and rewards expense Other expense

25 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU – CONSUMER CREDIT CARD MARKET REPORT

additional spending may spur. Both general purpose and private label card issuers incur similar

interest expense at roughly 2 percent of receivables.

FIGURE 9: ANNUAL EXPENSE LINE ITEMS AS A SHARE OF RECEIVABLES, 2022 (Y-14+)

2.3 Co-brand partners

Hundreds of millions of U.S. consumers are enrolled in loyalty programs at large merchants,

and almost 74 million of those consumers also accrue rewards at those companies by using co-

branded credit cards.

44

These jointly branded cards are offered, in partnership, by banks issuing

the credit cards; a payment network that processes transactions; and a merchant offering points,

miles, or other rewards to customers. These credit cards are common, with more than one in

three general purpose cards being co-branded in 2021.

45

Responsibilities in each partnership depend on the contract between the financial institution

and its partner. Typically, the partner assists with marketing and account acquisition and the

issuer extends credit and services accounts. Since merchant partners provide issuers access to

an existing base of consumers, who can generate millions of dollars in interchange and interest

44

Major merchants and consumer brands partner with credit card issuers to offer their customers merchant-branded

credit cards. Two types of partnerships include 1) co-branded (or co-brands) that are general purpose credit cards

and transact on a network and 2) private label, which primarily operate with a single retailer. Non-retail

partnerships typically exist between airlines, hotels, or other travel-based businesses and an issuer. For example, an

issuer may offer both co-brand general purpose and private label credit cards in partnership with a major home

improvement chain as part of their retail business. The same company may then partner with a large airline to

provide general purpose cards that feature the partner’s logo and earn rewards in the airline’s miles, separate from

that retail unit.

45

See Packaged Facts, Co-Branded Credit Cards in the U.S., 8

th

Edition (July 2021).

2.0%

1.9%

6.8%

0.0%

2.7%

3.8%

5.0%

5.9%

General Purpose

Private Label

0%

1%

2%

3%

4%

5%

6%

7%

Interest expense Interchange and rewards expense

Loan loss provision expense Other expense

26 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU – CONSUMER CREDIT CARD MARKET REPORT

revenue for the card issuer, these partnerships can be quite lucrative.

46

Winning or renewing a

contract may involve multiple issuers responding to a merchant’s Request for Proposal (RFP)

where banks will compete on offering the best terms for the partner.

47

To compete successfully,

an issuer may offer richer payments to the merchant, which may be funded through higher

interest and fees or lower rewards for consumers.

Payments to partners for rewards like points, miles, or other discounts represent the vast

majority of payments from issuers to merchants in co-brand relationships at 1.53 percent of

purchase volume associated with these large co-brand portfolios. Payments pursuant to revenue

sharing agreements then follow at 0.33 percent. Lastly, payments for the acquisition of new

cards represent 0.14 percent of spending on all co-brand cards.

48

Other payments from an issuer

to a partner include merchant rebates associated with interchange costs; benefits that a bank

funds and then a partner fulfills like baggage fees, companion passes, and free nights;

contractual funds obligated to operational costs like marketing and staffing; and bonuses based

on milestones in card growth. A co-brand partner might pay an issuing bank for reasons like the

provision of promotional-financing or loan repayment. However, these payments from partners

to issuers are limited and represented less than 0.10 percent of co-brand purchase volume in

2022. Both payments to and from issuers have remained fairly stable as a share of purchase

volume since at least 2019. Net of payments from merchants, issuers paid partners an average of

$279 per open account in 2022. For their top co-brand partnerships, major banks made total

net payments to merchant partners in excess of $28 billion in 2022, a 34 percent increase from

2019 levels.

46

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many airlines and hotels relied on the issuers of their co-brand credit cards for

loans and revenue through the sales of points and miles. See e.g. Leslie Josephs and Amelia Lucas, Delta use

frequent-flyer program to back $6.5 billion in debt, CNBC (Sep. 2020), https://www.cnbc.com/2020/09/14/delta-

launches-6point5-billion-debt-deal-backed-by-its-frequent-fl yer-program.html; and Leslie Josephs, Airlines’

frequent flyer programs prove a lifeline even as travelers stay home in pandemic, CNBC (Oct. 2020),

https://www.cnbc.com/2020/10/14/airlines-frequent-flyer-programs-prove-a-lifeline-even-as-travelers-stay-home-

in-pandemic.html.

47

See e.g. Hugh Son, Amazon renews Prime credit card tie-up with JPMorgan Chase after flirting with American

Express, CNBC (Mar. 31, 2022), https://www.cnbc.com/2022/03/31/amazon-prime-amazon-renews-prime-credit-

card-pact-with-jp morgan-after-flirting-with-american-express.html.

48

The findings in this section were gathered through data provided by several mass market issuers on 33 of their top

co-brand card partnerships by 2022 card purchase volume.

27 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU – CONSUMER CREDIT CARD MARKET REPORT

FIGURE 10: PAYMENTS TO MAJOR CO-BRAND PARTNERS AS A SHARE OF PURCHASE VOLUME, 2022

(MMI)

2.4 Networks

Networks connect merchants and credit card issuers by maintaining the flow of funds and

information, often called “the rails,” through which credit card transactions are authorized and

settled. The vast majority of general purpose credit cards in the United States run on the Visa or

Mastercard networks, representing about 85 percent of accounts in 2021.

49

Most of the

remainder are issued on the American Express and Discover networks.

50

These four firms have

remained the dominant card networks for decades.

51

Visa and Mastercard function solely as a network and operate under an “open loop” or “four-

party” model in which each transaction facilitated by the network involves the cardholder,

issuer, merchant, and acquirer (a financial institution that enables a merchant to accept credit

card payments). When a merchant accepts Visa or Mastercard credit cards, they enter into a

contract with an acquirer for payment processing services. The acquirer stands between the

merchant and the network, routing the transaction from the merchant to the network for

49

The Nilson Report, No. 1235.

50

These firms are both issuers and networks; however, at times, other banks issue cards on their networks.

51

In 1950, Diners Club established the first general purpose charge card by first developing relationships with local

restaurants. In the following decade, Bank of America started BankAmericard (which later became independent and

was renamed Visa) and American Express launched its network; in the 1960s, a group of banks began the Interbank

Card Association (later Mastercard). Discover started as a subsidiary of Sears in the 1980s, but became an

independent company in 2007, acquiring Diners Club in 2008.

28 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU – CONSUMER CREDIT CARD MARKET REPORT

authorization, and routing the payment to the merchant.

52

The agreement between the

merchant and acquirer specifies the level of fees for processing transactions, also known as the

merchant discount rate.

53

Transactions on the American Express and Discover networks run on a “closed loop” system

with three parties: the cardholder, the merchant, and one company that both issues the card and

acts as the network. In most cases, American Express and Discover act as the network, issuer,

and acquirer, and they negotiate directly with merchants for the fees assessed on transactions.

54

Importantly, networks set the level of fees—interchange—that make up the majority of the

merchant discount rate. Networks set an interchange schedule which varies based on the type of

transaction, the size of the retailer, and the type of credit card used. Issuing banks receive the

majority of interchange revenue. However, card networks also receive a fee in exchange for

facilitating the transaction using their payment network, oftentimes for including services such

as fraud detection. Overall, networks report consistent net margins near 50 percent.

55

2.5 Debt collectors

Debt collection affects millions of consumers, including many cardholders who face difficulty

repaying their credit card debts. As of the first quarter of 2022, nearly one-quarter of all

consumers’ credit reports (23.5 percent) had at least one collection tradeline.

56

Medical debt

made up over half those tradelines in third-party collections, as shown in Figure 11. In contrast,

only 13 percent of debt collection tradelines on consumer credit reports were for banking or

financial debts (including credit cards). In 2022, 287 unique furnishers reported banking and

52

The U.S. acquirer market has seen high levels of consolidation in the past few years, and the handful of major

players represent the vast majority of market share as a percentage of both payment volume and transactions. See

The Nilson Report, No. 1218.

53

Most of the merchant discount fee is interchange paid from the acquirer to an issuer through a network, but the

acquiring institution retains the balance of the merchant discount fee. If a merchant becomes bankrupt or otherwise

cannot fulfill the promise of goods, the acquirer assumes the risk; likewise, acquirers play a large role in resolving

disputes and chargebacks.

54

For exceptions, see The U.S. Government Accountability Office, Credit Cards – Rising Interchange Fees Have

Increased Costs for Merchants, but Options for Reducing Fees Pose Challenges, (Nov. 2009),

https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-10-45.pdf, at 9.

55

See The Economist, Can the Visa-Mastercard duopoly be broken?, (Aug. 2022),

https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2022/08/17/can-the-visa-mastercard-duopoly-be-broken.

56

CFPB, Market Snapshot: An Update on Third-Party Debt Collections Tradelines Reporting, (Feb. 2023),

https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_market-snapshot-third-party-debt-collections-tradelines-

reporting_2023-02.pdf.

29 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU – CONSUMER CREDIT CARD MARKET REPORT

financial debt collection tradelines, including credit card collections tradelines. The top four

furnishers of banking and financial collections tradelines reported 82 percent of these

tradelines.

57

However, a credit card in collections sometimes may not appear on consumer

credit reports as a debt collection tradeline. In one survey, 44 percent of consumers with debts

in collection reported having at least one credit card debt in collections.

58

FIGURE 11: DISTRIBUTION OF ORIGINAL CREDITOR TYPE AMONG THIRD-PARTY COLLECTIONS

TRADELINES, 2022 (CCP)

59

Over the past four years, debt collection industry revenue has grown. It rose from $12.7 billion

in 2019 to $18.2 billion in 2020,

60

even with Federal and state measures restricting collections

actions during the COVID-19 pandemic, such as a federal eviction moratorium and state laws

restricting call frequencies, litigation, and garnishments. In 2021 and 2022, debt collection

industry revenue continued its upward trend, reaching $20.3 billion in 2022, as agencies

benefitted from consumers paying down existing balances.

61

A significant majority of the industry’s revenue is generated by firms contracting with creditors

and debt buyers to collect their debts on a contingency fee basis. In contingency collections, the

collector receives a share of the amount collected as a commission. A significant source of

industry revenue comes from debt buyers, who purchase accounts (usually contained in

portfolios) from the original creditor or other debt buyers and then generally seek to collect on

57

Id.

58

CFPB, Consumer Experiences with Debt Collections: Findings from the CFPB’s Survey of Consumer Views on

Debt, (Jan. 2017), https://www.consumerfinance.gov/data-research/research-reports/consumer-experiences-debt-

collection-findings-cfpbs-survey-consumer-views-d eb t/.

59

Market Snapshot, supra note 56.

60

See Tina Fine, Debt Collection Agencies in the US, IBISWorld (Jan. 2023).

61

Id.

57% 13% 11% 8% 4% 4%

3%

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100%

Medical Banking and financial Telecommunications Retail Other Utilities Rental or leasing

30 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU – CONSUMER CREDIT CARD MARKET REPORT

the debt, either by themselves or through third-party debt collectors. Most credit card debt

collections tradelines are reported by debt buyers, and as of 2022, debt buyers furnished 17

percent of total third-party collections tradelines.

62

This share has increased by almost 50

percent since 2018. In contrast, collectors that collect on behalf of creditors reported 38 percent

fewer collections tradelines over this period.

63

Total employment by debt collectors has recently increased, even as the credit card debt

collection market has grown more concentrated. After years of decline, employment in the third-

party debt collection industry rose from 130,000 in 2019 to roughly 138,000 U.S. workers in

2022.

64

However, the industry continues to consolidate, with the number of debt collection

enterprises declining by 28 percent and the number of debt collection establishments declining

by 26 percent from 2014 to 2022.

65

Major issuers surveyed reported using 30 unique third-party

debt collection agencies in 2022, down significantly from 55 unique agencies in 2020.

66

The

number of debt buyers utilized by these issuers decreased slightly to 15 unique buyers in 2022

from 17 unique buyers in 2020.

62

CCP.

63

Id.

64

See Debt Collection Agencies in the US, supra note 60.

65

Id.

66

MMI.

31 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU – CONSUMER CREDIT CARD MARKET REPORT

3. Use of credit

This chapter reviews several measures of consumers’ use and repayment of credit cards. First,

this section describes the size of the market by spending and debt levels. In terms of purchase

volume and nominal debt levels, the credit card market has never been so large. By other

indicators such as inflation-adjusted total balances and average debt per cardholder, the market

has just returned to highs last seen in late 2019. Second, this section looks at repayment through

total payments, payment rates, and revolving behavior. Last, this section reports on non-

payment by examining delinquency and charge-off rates. Many of these indicators point toward

consumers’ increased ability to make larger and more timely payments on their outstanding

credit card balances in 2020 and 2021. While measures like revolving and delinquency rates

increased in 2022, they remained below pre-pandemic norms.

3.1 Purchase volume

Credit card purchases reached new highs following a pullback during the first year of the

COVID-19 pandemic. Total purchase volume for Y-14+ issuers in 2022 was $3.2 trillion, a 48

percent increase from 2020 levels. Purchase volume exceeded its pre-pandemic level starting in

the second quarter of 2021 and continued to grow following a seasonal pattern, even after

adjusting for inflation, as shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1: QUARTERLY PURCHASE VOLUME, NOMINAL AND INFLATION-ADJUSTED (Y-14+)

Most of the increase in spending was on general purpose card accounts, as private label card

purchases remained relatively low. General purpose card purchase volume for issuers in the

CFPB’s sample increased to $3 trillion in 2022, 50 percent higher than in 2020. In contrast,

private label card spending is much lower at $180 billion in 2022 and has remained relatively

$440B

$484B

$530B

$578B

$614B

$597B

$763B

$846B

$554B

$597B

$641B

$686B

$712B

$683B

$812B

2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

$0

$200B

$400B

$600B

$800B

Purchase volume (nominal) Purchase volume (real)

32 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU – CONSUMER CREDIT CARD MARKET REPORT

flat since at least 2015, such that private label card spending represents a declining share of

overall card purchase volume.

FIGURE 2: QUARTERLY PURCHASE VOLUME (Y-14+)

Consumers with higher credit scores generally spend more on their cards. Average general

purpose purchase volume per account ranged from about $1,100 annually for cardholders with

deep subprime scores to $10,700 and $12,600 for cardholders with prime plus and superprime

scores, respectively. Private label purchase volumes followed a similar trend, with the exception

of superprime cardholders, who spent less on such cards than cardholders with scores between

660 and 800.

FIGURE 3: ANNUAL AVERAGE PURCHASE VOLUME PER ACCOUNT, 2022 (Y-14+)

$397B

$440B

$487B

$532B

$568B

$554B

$714B

$796B

$43B

$44B

$44B

$46B

$45B

$43B

$49B

$50B

2015 2016

2017 2018

2019 2020 2021 2022

$0

$200B

$400B

$600B

$800B

General purpose Private label

$1,109

$325

$2,051

$680

$3,338

$1,019

$5,910

$1,360

$10,697

$1,652