The content on this webpage was developed by NIH SEED based on its collective experience working with the NIH innovator

community. This information has been developed, for informational purposes, to address questions frequently asked by NIH

awardees, and represents the experiences of the subject matter experts who contributed to its development.

Regulatory Knowledge Guide for Therapeutic Devices

NIH SEED Innovator Support Team, MITRE

Updated December 2023

Introduction

Navigating the regulatory path for bringing a new medical device to market can be a challenge for

individuals and businesses alike. This guide aims to help individuals and small businesses as they

perform medical device research prior to the official application process. Understanding the

regulatory path while conducting research, designing prototypes, developing testing protocols, and so

on will help facilitate the medical device application process.

Within the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the Center for Devices and Radiological Health

(CDRH) is responsible for ensuring the safety and effectiveness of medical devices.

A medical device is defined as any instrument, machine, contrivance, implant, in vitro reagent

that’s intended to treat, cure, prevent, mitigate, or diagnose disease in humans.

Medical devices range from simple instruments such as tongue depressors, to complex systems such

as robotic surgical suites, to implanted mechanical joints. The definition of a medical device (and the

authority of CDRH) also includes in vitro diagnostic (IVD) tests, and Software as a Medical Device

(SaMD). However, this guide’s content does not apply to those technologies.

1

1

The IVD and Digital Health guides provide more specific resources for IVD and SaMD products. Note

that some devices related to blood collection and processing are regulated by the Center for Biologics

Evaluation and Research rather than CDRH.

Based on the definition above, the key question is whether your research focuses on development of a

regulated medical device product. CDRH provides many examples of medical devices categorized by

purpose/specialty on its website. FDA regulates over 6000 existing types of medical devices.

If your research is for a regulated medical device, you will need to familiarize yourself with the

regulatory requirements before bringing your device to market. In this guide, CDRH policies and

processes for medical device research and Market Authorization are outlined, along with other

relevant tips at various stages of product development.

In addition, there is a NIH Small Business Education and Entrepreneurial Development (SEED)

regulatory case study (listed below) that provides more in-depth discussion and examples on managing

the multiple tasks related to moving new innovations through the regulatory process.

Link to Medical Device Regulatory Case Study #1 on an Acoustic Imaging AI

2

Toolkit

Please use the Word navigation panel to jump to sections that are relevant to your needs. Bolded

terms within the text are defined in the Glossary.

If you have additional questions or want to connect with someone to discuss your specific situation,

the NIH Office of Extramural Research (OER) Small Business Education and Entrepreneurial

Development (SEED) team recommends you contact the SEED Innovator Support Team.

After reading this Regulatory Knowledge Guide, you will have a better understanding of these important aspects

of medical device product development.

• The regulatory approval strategy may impact early-stage prototypes and the kinds of testing you

conduct.

• Pre-submission meetings with CDRH are a valuable resource—request them early and prepare well.

• Ensure you have a clear understanding of the regulatory requirements of your clinical studies.

• Before applying to FDA, you will determine the appropriate pathway—510(k), Premarket Approval, and

De Novo—for clearance and approval.

• There are additional compliance obligations after FDA market authorization of your device.

Table of Contents

Introduction............................................................................................................................. 1

List of Figures........................................................................................................................... 4

1 Requirements in Medical Device Design and Development..................................................... 5

1.1 Medical Device Oversight and Exceptions.............................................................................. 5

1.2 Prototype Design and Development ..................................................................................... 6

2 Feasibility Testing and Regulatory Considerations .................................................................. 7

2.1 Bench Testing ................................................................................................................... 7

2.2 Certified Lab Testing .......................................................................................................... 8

2.3 Side-By-Side Comparison Testing ......................................................................................... 8

2.4 Animal Testing .................................................................................................................. 9

2.5 Human Testing ................................................................................................................ 10

2.6 Usability Testing .............................................................................................................. 10

3 Conducting Human and Clinical Studies ............................................................................... 11

3.1 Investigational Device Exemptions ..................................................................................... 12

3.2 Early Feasibility Studies (EFS)............................................................................................. 13

3.3 Data Requirements .......................................................................................................... 13

3.4 Intended Use Populations ................................................................................................. 14

4 Meeting with CDRH ............................................................................................................. 14

4.1 Pre-Submission Meeting ................................................................................................... 15

4.2 Regulation, Product Code, and/or Predicate Device .............................................................. 16

4.3 Intended Use and Indications for Use Statements................................................................. 17

4.4 Test Plans and Preliminary Results ..................................................................................... 18

4.5 Breakthrough Device Designation ...................................................................................... 18

5 Choosing a Formal Pathway for Clearance and Approval ...................................................... 19

5.1 Regulatory Precedents ..................................................................................................... 21

5.2 Industry Partners and Regulatory Affairs Consultants ............................................................ 22

5.3 Safety and Efficacy or Substantial Equivalence ..................................................................... 22

6 Ensuring Manufacturing Practices Oversight ........................................................................ 23

6.1 Quality Management Systems ........................................................................................... 23

6.2 Quality System Regulation ................................................................................................ 24

6.3 International Standards .................................................................................................... 25

7 Modifying a Device after Market Authorization .................................................................... 25

7.1 Evidence from Outside the U.S........................................................................................... 25

7.2 Minor Changes to a Device................................................................................................ 26

7.3 Substantive Changes to a Device ........................................................................................ 26

7.3.1 Benefit-Risk Ratio ............................................................................................................................................ 27

7.3.2 New Intended Use ........................................................................................................................................... 28

7.3.3 New Clinical Trial ............................................................................................................................................. 28

7.3.4 Real-World Evidence from Routine Clinical Care .......................................................................................... 29

8 Additional Resources ........................................................................................................... 29

List of Figures

Figure 1. Defining device concept ................................................................................................. 6

Figure 2. Planning for final/confirmatory testing ............................................................................. 7

Figure 3. Planning for human testing ........................................................................................... 11

Figure 4. Preparing to meet with FDA .......................................................................................... 15

Figure 5. Preparing for Market Authorization ............................................................................... 20

Figure 6. Establishing quality manufacturing processes .................................................................. 23

Figure 7. Making modifications to a device already on the market ................................................... 27

1 Requirements in Medical Device Design and

Development

Congratulations! You’ve taken a germ of an idea, done your research, and

are now starting to design or build your prototype medical device. You

know that medical devices are regulated by FDA. But when does the

regulatory process start? The answer depends on several factors. Whether

your device takes form on paper, in simulation, or as a prototype, different versions of a medical

device may have different regulatory pathways.

To be clear, all medical devices are regulated by FDA. However, if a piece of the technology of a

medical device can be sold as a component to another device, the single component does not need

regulatory approval, but the medical device does. It’s important to note that if the new component is

used to service or remanufacture the existing product, you should still consider contacting FDA to

determine whether regulations may apply. Additionally, if you are acting as a component

manufacturer, you may be required to register and list your device with the Center for Devices and

Radiological Health (CDRH).

You are responsible for the safety and effectiveness of your device. As a device

manufacturer, you will need Market Authorization from FDA before you can

legally sell your product.

Resource:

NIH SEED: FDA CDRH Registration ad Listing Requirements

1.1 Medical Device Oversight and Exceptions

As noted in the introduction, FDA’s CDRH is responsible for ensuring the safety and effectiveness of

medical devices marketed in the U.S. While that covers most devices, there are two categories of

medical device research that fall outside of FDA authority. They include:

• Basic physiological research or off-label use, without intent to market

• Devices that fall under CDRH “enforcement discretion”

In the first case, the main principle is that FDA does not regulate the practice of medicine. FDA

regulates the commerce of medical products. If you are working with healthcare professionals on

preliminary exploratory research for strictly scientific or medical purposes, then FDA oversight applies

only if the research poses significant risk to humans.

In the second case, CDRH can exercise what is called “enforcement discretion”—meaning FDA does not

intend to enforce regulatory requirements for specific types of devices. Examples include convenience

kits and some mobile medical apps that meet the definition of a marketed medical device. However,

for these products CDRH has determined the devices do not currently require oversight because they

pose lower risk to the public. Device researchers should be able to provide evidence, based on

precedent and/or interaction with CDRH, that their technology is under enforcement discretion—

otherwise you should assume it is a regulated medical device.

Figure 1. Defining device concept

1.2 Prototype Design and Development

As you work through the specifics of your design, you may experiment with different design options and

components. In some cases, you may need to design and build multiple prototypes before you finalize the

design of your device.

A final device design (design lock) fully defines all components of your device and is referred to as a device

master record, which is essentially a “recipe” for manufacturing your device. The device master record is

supported by documentation in the design files (part of your Quality Management System; see Section 6.1).

Generating a device master record begins by documenting design validation during early development. It

describes all the components needed to manufacture and test the device. Another important set of documents

you will develop are your design controls—a formal and documented methodology of your product

development activities.

As the constructed device begins to take shape, you should also consider the metrics for safety and effectiveness

that are required for initial clinical use and marketing approval.

Once your design is finalized, you need to build and test your prototype to provide evidence of its safe and

effective use. A prototype of the device is required before most feasibility testing can begin. At this point, you

should investigate potential regulatory pathways based on the intended use of your device.

Resources:

FDA: CDRH Design Controls Overview

FDA: Device Development Process

NIH SEED: Navigating FDA: Device (and Diagnostic) Development Requirements

2 Feasibility Testing and Regulatory Considerations

Throughout the medical device development process, you need to conduct

several different types of testing. Some are required for the regulatory

process and some are optional. For example, if the technology you are using

is very early in its development, you may be actively conducting research

simply to prove whether the idea is feasible. This is called feasibility testing.

This aspect of the process does not generally fall under FDA oversight. However, confirmatory

testing—validation that the device functions as intended—is required and is a critical part of any

regulatory plan.

Feasibility testing can include:

• Bench testing

• Certified lab testing

• Side-by-side comparative testing

• Animal testing

• Human testing

• Usability testing

After demonstrating the feasibility of your approach, you should create a new plan to confirm/validate

the performance of your device. It is helpful to think of confirmatory testing as a separate step entirely

from the research that supported the proof of concept feasibility.

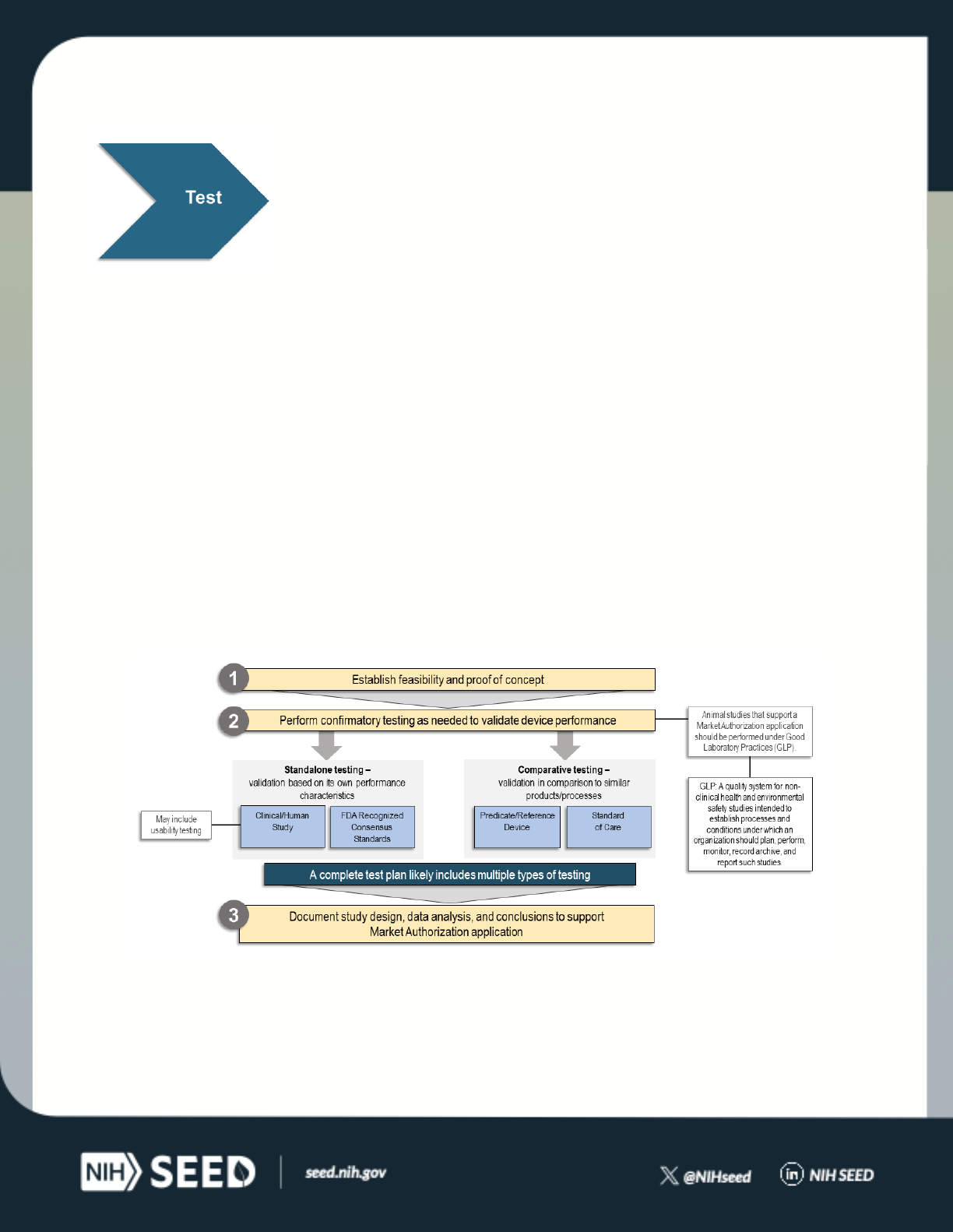

Figure 2. Planning for final/confirmatory testing

2.1 Bench Testing

Bench testing is testing of the device, or sub-components, to validate their performance without use of

humans or animals. For example, you may propose to perform mechanical or electrical analysis of the

device hardware. Evaluation of the device that involves simulation or processing of retrospective data

can also be considered bench testing.

Bench testing is extremely valuable in the development/research phase of innovative technology.

However, it is unlikely that feasibility bench testing will directly translate into tests reviewed by CDRH.

You should use bench testing to settle on an initial concept or prototype, and then begin to develop a

confirmatory device evaluation strategy that accounts for relevant clinical conditions.

Use bench testing to settle on an initial concept or prototype.

Non-clinical and non-animal testing is a critical part of early-stage research for medical devices. Bench

testing can certainly be used in later-stage confirmatory validation of the technology as well.

2.2 Certified Lab Testing

There are internationally recognized standards for many components of a given device. Some devices

may not have any applicable standards, while others may have dozens.

Standards that are recognized by FDA provide sufficient test methods to demonstrate safety and

efficacy of the technology within the context of that standard. If the new technology does not meet

the standards, you will need to provide a justification to FDA why that does not raise new regulatory

questions.

Some of these standards include tests that are readily performed by certified test labs. You will need to

document conformance to standards and include any test lab reports in the premarket application.

Since standards are not free, consider whether to purchase the standards and perform the tests in-

house or to outsource the standardized validation to a certified test lab.

Resource:

FDA: CDRH’s Recognized Consensus Standards Database

2.3 Side-By-Side Comparison Testing

If you have access to an existing predicate device, you can perform confirmatory testing by comparing

your device to the predicate device directly. This mainly pertains to Class II devices and the 510(k)

pathway.

Showing your device is the same or better in all capacities as your predicate is

one way to demonstrate substantial equivalence.

Using this method to demonstrate substantial equivalence is often cheaper and more direct than

creating a new body of evidence.

If the predicate device is available to you (whether it is already accessible or is straightforward to

acquire), the validation of your technology can include a direct comparison to the existing predicate.

For example, if you are developing a wearable over-the-counter electrocardiograph, you can compare

the measurements from your technology to the measurements from an existing wearable monitor.

The head-to-head comparison may not be sufficient validation on its own but it can provide a strong

argument for substantial equivalence.

Furthermore, if the head-to-head comparison is to your own technology as a predicate, then the

Special 510(k) program may be an option (providing a more streamlined review process). If this is your

first Special 510(k), it is a good idea to first reach out to CDRH to clarify that the path is open to you:

this often involves discussion of the test methods and clarification as to whether they are “well

established.”

On the other hand, the existing technology may be too expensive or otherwise too burdensome for an

individual to acquire. In these cases, a side-by-side comparison is not required. Instead, a written

discussion of similarities and differences can be included in your Market Authorization application, and

an independent clinical or non-clinical validation can be performed.

Resources:

NIH SEED: Mapping Your Way Through the FDA's 510(k)

FDA: Guidance on the Special 510(k) Program

2.4 Animal Testing

Animal testing of device feasibility is a useful option to inform device design and future studies. Animal

models can be leveraged to test the device functionality (such as performance measurements) or the

device safety (such as biocompatibility). The study rationale, assurances, objectives, schedule,

equipment, metrics, and tests should all be documented and included in the final report to CDRH.

If you are developing an animal model to better understand the feasibility and function of your device

prototype, then your methods may not need to strictly conform to all good laboratory practices (GLP).

However, animal test results that are later used in a Market Authorization application are expected to

conform to GLP (see Section 3.3).

CDRH has prepared a draft guidance document regarding GLP and premarket device submissions.

Because the guidance is a draft (not final), it should not be referenced in a regulatory submission.

However, it can provide helpful insight into current and future FDA considerations.

Even if animal feasibility testing is not completed or reviewed by FDA at this stage of the process, you

may still want to look ahead to potential animal testing requirements for future applications.

Resources:

FDA: Applicability of Good Laboratory Practice in Premarket Device Submissions: Questions &

Answers

NIH: General Animal Research Policies

2.5 Human Testing

As with all human testing, the first step should be to consult with your Institutional Review Board

(IRB). IRB responsibilities include reviewing the qualifications of investigators, the adequacy of

research sites, and the determination of whether an Investigational Device Exemption is needed.

If the feasibility study is found to present risks to the human subjects, you will need to consult with

CDRH (see Section 3.2 on the Early Feasibility Studies program). However, human testing to develop

an understanding of feasibility does not always require FDA oversight—particularly if the testing has

low risk and/or focuses on the usability of the device. For example, studies that can safely leverage

data from healthy volunteers can typically be run with IRB approval.

Section 3 provides more detailed information on human testing requirements and considerations.

Resource:

FDA: Guidance for IRBs, Clinical Investigators, and Sponsors IRB Responsibilities for Reviewing the

Qualifications of Investigators, Adequacy of Research Sites, and the Determination of Whether an

IND/IDE Is Needed

2.6 Usability Testing

CDRH has guidelines on human factors testing and usability, and how these forms of validation can be

incorporated in a premarket application.

Usability testing can be an important part of feasibility testing simply because a

medical device that is hard to use is less likely to be used correctly and may not

be used at all.

Feedback on the form, function, and interface of the device to ensure it is effective and convenient for

users is a critical component of usability testing. The usability test may or may not be on human

subjects, but it does focus on feedback from the human user(s) of the device. Information for user

testing can inform, for example, the instructions for use, screen displays/interfaces, form and function,

or packaging.

Usability testing can sometimes be implicitly addressed by the innovators’ research and feasibility

studies. Depending on the device type, it may be worth considering a formal investigation of device

usability. While usability testing is not always required by FDA, it is a good business practice that can

indirectly inform and improve your regulatory discussions.

Resource:

FDA: Applying Human Factors and Usability Engineering to Medical Devices

3 Conducting Human and Clinical Studies

Unlike drug development, which generally involves a regimented three-

phase clinical trial process, medical devices may or may not require human

testing. When they do, it is most important to coordinate with your local IRB

to evaluate the safety and ethics of the human testing. If the risk is high and

a significant amount of clinical evidence is required, you may need to submit a study proposal (still

referred to as a clinical trial) to FDA before conducting the study. This proposal to FDA CDRH is called

an Investigational Device Exemption (IDE).

The first line of protection for human subjects comes from the IRB overseeing the research. The IRB

oversees the health and well-being of human subjects, and the ethics of the research involved. If any

human testing will be done, then an IRB should have reviewed and approved the study protocol. After

review, the IRB may determine that the study needs to be referred to FDA for additional oversight

(such as an IDE).

Figure 3. Planning for human testing

Resources:

FDA: Clinical Trial Guidance

FDA: IRB Responsibilities for Reviewing the Qualifications of Investigators, Adequacy of Research Sites

3.1 Investigational Device Exemptions

Not all human testing requires an IDE. Whether it does or does not depends on the risks involved with

the testing plan. The IRB should have the experience needed to determine whether a CDRH study risk

determination is needed. Based on the technology and intended use of the technology, along with the

details of the proposed investigation, CDRH determines if the study poses significant risk (SR) or non-

significant risk (NSR). If an IRB has determined a study is NSR, then you do not need to confirm this

with FDA to proceed with your research plan.

Not all human testing of medical devices requires an IDE. If an IRB is uncertain

whether a proposed clinical trial is significant risk or non-significant risk, you

will need to request a study risk determination from CDRH.

If the IRB suggests a clinical trial is SR, and this is confirmed by FDA, then an IDE will be required

before human testing can begin. To request an IDE, you will need to present your study plans (size,

methods, and success criteria) to CDRH, along with your risk mitigation strategy.

The NIH has a list of policies and information regarding IRBs and multi-site human testing.

Furthermore, the Regulatory Guidance for Academic Research of Drugs and Devices (ReGARDD) group,

funded in part by NIH Clinical and Translational Science Awards, has produced an info page and a study

risk determination video. If you are uncertain about your device’s risk level, you can review the FDA

resources below to determine whether your product falls into those categories.

IRB responsibilities include reviewing the qualifications of investigators, the adequacy of research sites,

and the determination of whether an IDE is needed—as described by CDRH criteria. In most cases, the

IRB will be instrumental in guiding you toward submitting an IDE (and/or pre-IDE risk determination

meeting).

Devices that would require an IDE but are for humanitarian use—meaning they are intended to

benefit patients (treatment/diagnosis) with diseases or conditions that affect not more than 8,000

individuals in the U.S.—can submit a Humanitarian Device Exemption (HDE) application. If you are

proposing to investigate and/or market your device via an HDE application, your first step is to request

a Humanitarian Use Designation from CDRH.

Resources:

FDA: Significant Risk and Nonsignificant Risk Medical Device Studies

FDA: IDE Application

FDA: IDE Definitions and Acronyms

FDA: Humanitarian Use Device (HUD) Designations

FDA: Case Study: Regulatory Pathways for Pediatric Medical Devices

FDA: IRB Responsibilities for Reviewing the Qualifications of Investigators, Adequacy of Research Sites

FDA: Webinar Humanitarian Use Device Program Interview

NIH: Single IRB for Multi-Site or Cooperative Research

Article: Study Risk Determinations from FDA

ReGARDD: Study Risk Determinations from FDA

ReGARDD: Risk Determination video

3.2 Early Feasibility Studies (EFS)

FDA recognizes that for some higher-risk devices, human testing is needed even to determine

feasibility of an idea. For such scenarios, it created EFS which are a type of IDE, for situations where all

information typically required for an IDE may not yet be known. This should be pursued only after

consulting with the IRB. Furthermore, a pre-IDE meeting with CDRH is highly recommended.

Before proposing an EFS, you should have as complete a picture of your device as possible. Examples

of devices that may consider an EFS are those that must be proven and optimized for use in the

human body, such as new cardiac surgical guides and tools. If possible, you should rely on bench or

animal tests for the prototype and its components.

You should also consider whether the device has a sufficiently mature technology to apply for a

traditional IDE rather than an EFS (which as noted above is a specific type of IDE). The knowledge

gained during an EFS is expected to inform the design of the final device as well as the design of a

larger (IDE) clinical trial.

Resources:

FDA: Introduction to the Early Feasibility Studies Program

FDA: EFS FAQ’s

NIH SEED: Investigational Device Exemption Applications and Pre-Submissions

3.3 Data Requirements

The amount of data needed to support a device application varies, based on the device and based on

the application. Some devices may require a large statistically powered clinical trial, for example

enrolling 100 patients or more, which should be planned after confirmatory testing. Other lower-risk

devices may use human confirmatory testing on an adequately small number of healthy volunteers to

demonstrate certain capability and performance. Some devices do not require human testing at all.

Likewise, the amount of data needed to apply for a market authorization application is substantially

larger than the amount needed to apply to FDA to simply request a meeting. These regulatory

processes are further described in Sections 4 and 5.

Human testing should be performed under supervision of an IRB. While IDEs are generally used for

large clinical trials, some devices may require an IDE for confirmatory testing as well. An IDE allows

you to distribute some number of devices for investigational use in clinical practice. It is important to

remember that not all human testing requires an IDE—only testing that poses significant risk. Often

the IRB will advise whether an IDE is required (based on experience with the device type and risk

level). If uncertainty remains, you can reach out to the relevant CDRH review office. It may answer

(non-bindingly) via email, or CDRH may suggest a pre-IDE meeting.

3.4 Intended Use Populations

While not required for training/developmental data, final testing/confirmatory data will need to

represent the entire intended population that will use the device. For example, if the device is

intended for all adults, but was tested only on student volunteers, questions about its general

performance could be raised. This is especially important in the development of artificial intelligence

and machine learning (AI/ML) algorithms which are primarily derived from large sets of data. See the

NIH SaMD & AI/ML Regulatory Workshop for more information.

Be prepared to discuss the generalizability of your testing/confirmatory dataset. You may also need to

reach out to clinical collaborators to gain access to a data set that captures the entire range of their

intended use population.

Final validation data should represent the intended use population. For medical devices that rely on

software systems and electronic patient data, you should be prepared to discuss the merits of your

data with FDA. In addition to the quantitative validation of the device performance, these are a few

important questions you should prepare for.

• What sub-populations are included/excluded?

• Do the results generalize?

• How is this information communicated to the consumer/customer?

4 Meeting with CDRH

You can meet with CDRH at multiple points during your device

development. You should consider when the time is right to request a pre-

submission meeting and recognize you can request multiple pre-

submission meetings to help guide critical activities in your device

development program. Some common topics for pre-submission meetings include preparing a device-

related submission to FDA, clinical study protocol design, data challenges, or confirming your

regulatory approach.

Figure 4. Preparing to meet with FDA

Resource:

NIH SEED: Strategies for Communicating Effectively in Writing with CDRH

4.1 Pre-Submission Meeting

CDRH’s pre-submission program and pre-submission meetings give you the chance to get feedback

and guidance from FDA before submitting an IDE or marketing application (such as a 510(k)). It is highly

recommended you meet with CDRH at least once before applying for Market Authorization.

To get the most out of a pre-submission meeting, you should:

• Bring a short list of questions (five or fewer)

• Include a description of the device and a clear, concise intended use statement

• Provide a summary of any previous discussions with regulators

• Summarize product development to date

It is up to you to drive the topics covered in your pre-submission meeting. Part of doing that is asking

the right questions and providing enough information for FDA to respond. For example, “Considering

the intended use and device description included above, does FDA agree that K123456 is a suitable

predicate?” is a better question than “What is a suitable predicate?”

Depending on the maturity of the technology and the level of experience you have with CDRH, you

may have a long list of questions you wish to clarify before seeking Market Authorization. However, a

pre-submission meeting (if your request is granted) will yield only one 60-minute meeting and a

written response on three to six specific questions. Therefore, it is advisable to focus on one primary

topic, such as a clinical testing plan or the identification of a predicate. Your goal is to have the most

complete possible discussion on one topic in that one-hour meeting. There is no hard limit to the

number of pre-submission meetings a company can request, so each meeting can address a unique

topic.

Pre-submission meetings with CDRH are a valuable resource. These are one-

hour meetings—it’s best to be prepared and focus your questions on one

primary topic.

You will receive the written response from CDRH in advance of the meeting, allowing the in-person

time to focus on areas where FDA does not agree with your plan. It is up to you to structure the

meeting in a way that is most beneficial to moving forward in the regulatory process. For example, the

FDA team will quietly sit and listen to a 60-minute sales pitch, but a five-minute description of the

device and 55-minute discussion of clinical testing plans would be much more constructive.

Resources:

FDA: Requests for Feedback and Meetings for Medical Device Submissions: The Q-Submission Program

FDA: Seeking Early Feedback from FDA Case Study

NIH SEED: 510(k) Pre-Submission Meetings

NIH SEED: De Novo Pre-Submission Meetings

4.2 Regulation, Product Code, and/or Predicate Device

Prior to requesting a pre-submission meeting with CDRH, you should research your device type, class,

and applicable regulations. If the technology is first-of-its-kind and there is no product code for it, there

are likely codes for similar technologies. It is beneficial to include those in pre-submission meeting

materials with discussion of how your device is both similar and different.

Among the most useful resources for identifying a predicate and/or learning about the regulatory

pathways of other existing similar devices are the CDRH databases for device classification, 510(k),

Premarket Approval (PMA), and De Novo. By searching these databases, you can access summaries of

previous device reviews, including an overview of the content that those devices presented during

their own FDA authorization. If you have regulatory questions that might be resolved by researching

recent CDRH activity for similar technologies, then these databases are a great starting point for you to

learn more.

Resources:

FDA: Device Classification Database

FDA: 510(k) Database

FDA: PMA Database

FDA: De Novo Database

4.3 Intended Use and Indications for Use Statements

Another important component of your pre-submission materials are your intended use and indications

for use (IFU) statements.

• The intended use of a device is a primary factor in CDRH’s evaluation of the risk potential for a device

and can impact the level of data FDA requires during a marketing review cycle. An intended use

statement is a general description of what the device will be used for—it covers all use cases. The

intended use will be part of determining the classification of the device. An example of an intended use

statement might be “this device is used for ablation of tissue in gynecology.”

• An IFU statement describes the specific use cases and contexts for the device. It is a subtle difference

that is commonly misinterpreted. An example of an IFU statement for the same device might be “this

device is used for endometrial ablation with ultrasound guidance.” The IFU statements of cleared

devices are publicly available; you can review IFUs for technologies similar to yours.

Intended use—what the device does

Indications for use—the context and specific use cases for the device

(who/where/when/how)

FDA recently finalized its intended use rule amending FDA’s regulations that describe “the types of

evidence relevant to determining whether a product is intended for use as a drug or device under the

Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act), the Public Health Service Act (PHS Act), and FDA's

implementing regulations, including whether a medical product that is approved, cleared, granted

marketing authorization, or exempted from premarket notification is intended for a new use.”

The final rule also addresses manufacturers’ liability and how FDA views off-label use and misbranding

violations—essentially, the agency can use any source of evidence (e.g., data, labeling, clinical use,

real-world evidence) or information in determination of a product’s intended use. However, isolated

instances of unapproved or off-label use are not sufficient, on their own, to describe a product’s

intended use.

For 510(k) submissions, every device will have a clear IFU statement included in its own section of the

510(k) summary. These submissions are publicly available, and you should review the IFU statement of

other similar technologies as you develop your own.

You will not find the intended use specifically listed in the 510(k) summary, though it may be implicitly

included in the IFU statement and/or device description. The intended use of the device is stated in the

corresponding device regulation. For example, the intended use of an ultrasound imaging system is

defined in 21 CFR 892.1550. If a new device/system proposed a different intended use than described

in that regulation, then it would be considered a different device by CDRH.

Resource:

FDA: Regulations Regarding “Intended Uses”

4.4 Test Plans and Preliminary Results

To provide enough information for CDRH to respond to questions and hold a fruitful discussion during

a pre-submission meeting, you should include a description of the methods and studies you will use to

demonstrate the functionality of your device. Note that FDA will not review or comment on the

adequacy of data/results themselves. For example, they would not answer questions such as “Does

FDA find our results to be sufficient?” (This type of question is addressed only during review of a formal

application for Market Authorization or IDE.) However, CDRH can provide extensive comments on

whether the data development or study plan/proposal includes and accounts for relevant non-clinical

and clinical factors.

A common pitfall in pre-submission meetings is to over-include the results of completed tests. CDRH is

not able to comment on the adequacy of the results during a pre-submission meeting. However, if

detailed descriptions of the methods are provided, then FDA can comment on whether the test plan is

sufficient.

Another common pitfall is to introduce new information during the meeting. After submitting your pre-

submission meeting request and corresponding documentation, you will wait for about two months

while FDA reviews the material. It’s possible your approach could change/evolve over the course of

those months, but during the meeting it is important to focus only on the material that FDA has seen in

the pre-submission materials. CDRH will not be able to comment on new material or new plans you

may want to propose during the meeting.

4.5 Medical Device Development Tool Program

FDA established the Medical Device Development Tool (MDDT) program as a way for FDA to qualify

tools that medical device manufactures can choose to use in the development and evaluation of their

devices. This program aims to standardize the “measuring stick” that is used to evaluate certain types

of medical devices.

The program has three categories of MDDTs:

• Biomarker Test (BT) is a test or instrument used to detect or measure a biomarker. Unlike qualified

biomarkers used in drug development, MDDTs also include the mechanism by which the biomarker is

captured and/or evaluated.

• Non-Clinical Assessment Model (NAM) is a non-clinical test model or method that measures or predicts

parameters of interest to evaluate the device safety, effectiveness, or device performance.

• Clinical Outcome Assessment (COA) describes or reflects how a person feels, functions, or survives and

can be reported by a healthcare provider, a patient, a non-clinical observer or through performance of

an activity or task.

Using existing MDDTs may relieve some additional questions that FDA might have had during review

since they would be familiar with and have confidence in the assessment outputs shown in support of

a marketing application.

Using existing MDDTs may proactively address questions FDA would typically include in their review, as

FDA is familiar with and has confidence in the outcomes of MDDTs when appropriately used.

As a company developing an innovative product, you may find that one of your measures may be

beneficial for the development of other medical devices. If so, you can submit your technology for

qualification as an MDDT. FDA acknowledgement of your product as a useful standard can lead to

increased customer confidence in your product and may be a source of revenue.

Though the MDDT program outlines three key categories, CDRH will consider new MDDTs in other

categories. For example, a digital health technology may not fit one of these categories but may still be

considered for the MDDT program - such as a developer using wearable sensors that can be deployed

in clinical trials.

4.6 Breakthrough Device Designation

With the goal of providing patients and healthcare providers with timely access to medical devices that

have the potential to provide more effective treatment or diagnostic options for seriously ill patients,

CDRH established the Breakthrough Devices Program. Breakthrough device developers benefit from

accelerated interactions with the review team, leading to faster identification (and hopefully

resolution) of FDA’s concerns during the premarket review process. Additionally, this program enables

FDA to prioritize the review of marketing submissions (e.g., PMA, 510(k), De Novo) with Breakthrough

Device Designations (BDDs). The program is available for devices that provide for more effective

treatment or diagnosis of life-threatening or irreversibly debilitating diseases or conditions.

To obtain a BDD, you submit a data package as a Q-submission called a Breakthrough Device

Designation Request. The goal is to demonstrate that your device meets FDA’s pre-defined criteria.

Note that even if the design of the device clearly satisfies the criteria, CDRH may decline the request if

data demonstrating the device’s ability to achieve its proposed performance characteristics are not

included.

Resources:

NIH SEED: Breakthrough Device Designation Requests

FDA: Breakthrough Devices Program

FDA: Requests for Feedback and Meetings for Medical Device Submissions: The Q-Submission Program

5 Choosing a Formal Pathway for Clearance and Approval

As you begin to compile your device’s premarket application, you will need

to choose which CDRH regulatory path—510(k), PMA, or De Novo—is the

most appropriate for your device. Each path has a specific set of materials

that are required with your market application.

The correct regulatory path for your device is determined largely by its device classification. Class I

medical devices pose little to no risk to the user and typically do not require premarket authorization

from CDRH. Class II devices are considered to pose moderate risk to users. Class III devices are

considered to pose the highest risk to users (e.g., implantable devices) and are subsequently subject to

the most rigor during the approval process.

Existing medical devices are already classified and can be found on the associated online database.

First-of-their-kind devices are automatically considered Class III (high risk), unless the De Novo pathway

is granted (see below).

Figure 5. Preparing for Market Authorization

510(k): The content of a 510(k) application is outlined on FDA’s website. The key focus is on substantial

equivalence comparison—which should be in a clear and comprehensive format. It should identify all

relevant similarities to and differences from to the predicate device including (but not limited to):

intended use, indications for use, target population, context/setting of use, design/functionality,

performance, materials, and standards met. Another important part of a 510(k) application is the

510(k) summary. The 510(k) summary is an overview of how substantial equivalence was

demonstrated and determined. The summary will be publicly available after the device is successfully

cleared. All 510(k) summaries include specifically required content. The 510(k) pathway typically

applies to Class II devices.

PMA: The content of a PMA application is also outlined on FDA’s website. A PMA application involves

many volumes of materials to be submitted to FDA. The volumes include (but are not limited to) device

description and intended use, non-clinical and clinical studies, case report forms, manufacturing

methods, and labeling. With all materials in place, the key to the review is determination of safety and

efficacy of the device based on the clinical investigations performed by the innovator. A successfully

completed PMA also includes a publicly available summary, called the Summary of Safety and

Effectiveness Data. The PMA pathway is mainly applicable to Class III medical devices.

De Novo: The content of a De Novo application is described in Attachment 2 of FDA’s guidance

document on the De Novo process. If you are proposing to submit a De Novo application, it is critical

you engage with CDRH via a pre-submission meeting(s). The focus of the De Novo pre-submission

meeting is on the classification of the new technology directly to Class II. To do this, you will work with

CDRH to create Special Controls, which are requirements to which all future devices must adhere to

when using your new technology as a predicate. As with the 510(k) and PMA pathways, there is a

publicly available De Novo Decision Summary. The Reclassification Order includes the Special Controls,

and the decision summary highlights how risks are mitigated.

Resources:

FDA: Choosing the Right Regulatory Pathway Case Study

FDA: Content of a 510(k)

FDA: 510(k) Submissions Case Study

NIH SEED: 510(k) Documentation and Application

NIH SEED: Mapping Your Way Through FDA’s 510(k)

FDA: Acceptance and Filing Reviews for Premarket Approval Applications

FDA: PMA Submissions Case Study

FDA: PMA Decision Summary

FDA: De Novo Classification Process

FDA: De Novo Submissions Case Study

FDA: De Novo Decision Summary

NIH SEED: Navigating FDA: Device (and Diagnostic) Development Requirements

5.1 Regulatory Precedents

Before filing a Market Authorization application, it is important to understand the existing regulatory

landscape for similar devices (particularly when submitting a 510(k)). This information is used to

discuss similarities and differences between your new device and the existing, on-market device(s) and

helps identify the appropriate regulatory path for your new device. This research should be done

before meeting with CDRH (to enable a useful discussion) and is accomplished by reading publicly

accessible decision summaries.

Among the most useful resources for identifying a predicate and/or learning about the regulatory

pathways of other existing similar devices are these four CDRH databases:

• Device classification This list includes all medical devices with their associated classifications, product

codes, FDA premarket review organizations, and other regulatory information

• 510(k) database

• PMA database

• De Novo database

These databases contain summaries of previous device reviews, including an overview of the content

those device developers presented to CDRH. They are a great starting point to learn more about

common regulatory requirements for your new device.

5.2 Industry Partners and Regulatory Affairs Consultants

Though FDA and NIH provide many resources for you to navigate the regulatory process, it is still a

complex and time-consuming task. Most medical device companies (even mature ones) have less than

10 employees and therefore frequently use external support to submit information to FDA. Industry

partners may include a larger medical device company, or a company with a similar product on the

market. You may want to consider working with regulatory affairs consultants that specialize in

specific product areas.

Regulatory consultants can provide tools for effective study design,

communication, and labeling, as well as creation and submission of meeting

and marketing authorization application paperwork.

Although very early interactions with CDRH can be conducted by experienced innovators without

external expertise, many small companies find the experience of consultants to be worthwhile . They

can provide tools for effective study design, communication, and labeling, as well as creation and

submission of meeting and marketing authorization application paperwork.

If you are not working with a specific partner or consultant, you may want to reach out to a local

incubator, accelerator, or small business development center to help identify appropriate expertise.

Your local entrepreneurial community may offer specific recommendations. It may also be helpful to

look up clearances of other devices to see which regulatory consultant submitted them. If you are part

of an academic team, your university may have a regulatory affairs master’s program that may be able

to help or advise.

Resources:

NIH: NHLBI Small Biz Hangout video: Finding the Right Regulatory Consultant

NIH SEED: Guidance on Selecting a Regulatory Consultant

5.3 Safety and Efficacy or Substantial Equivalence

The test plan (and its results/conclusions) is one of the most substantial parts of your medical device

application to CDRH. The data you gather will be used to support your statements about what your

device can do, and how it performs. Some studies involve clinical data, and others do not, but nearly all

innovative medical devices require proof of their function to be gathered and presented to FDA.

If your studies are complete and demonstrate definitively that the device is suitable for market

authorization, the next step is to prepare your FDA application. If this is your first application, it is

highly recommended to engage CDRH in a pre-submission meeting.

It is up to you to develop, execute, and evaluate your device evaluation plan before presenting it to

FDA. CDRH is willing to provide feedback on study designs, and to comment whether the study could

be sufficient to support a market authorization application. The most common way to do that is

through the pre-submission program (see Section 4.1).

6 Ensuring Manufacturing Practices Oversight

The primary regulatory concern with respect to manufacturing is the

presence of a quality management system (QMS). After a device is on the

market, the manufacturer may be inspected by FDA at any time, and the

manufacturing processes will be a large focus of that inspection. Note that

even manufacturers of Class I devices (which are typically exempt from premarket FDA review) must

register, list, and implement quality manufacturing processes.

Figure 6. Establishing quality manufacturing processes

The quality system regulation requires specific processes and corresponding documentation. When

the manufacturing facility is inspected, FDA will be looking directly for these QMS components.

The primary regulatory concern with respect to manufacturing is the presence of

a complete and enforced QMS.

Resources:

NIH SEED: Quality Management Systems Webinar

FDA: Quality System Evaluations of Good Manufacturing Practices

FDA: Quality System Regulation Title 21 CFR 820

FDA: Quality System Information for Certain Premarket Application Reviews

6.1 Quality Management Systems

A QMS formalizes the documents, processes, procedures, and responsibilities for achieving quality

policies and objectives. A QMS is needed to coordinate and direct an organization’s activities to comply

with regulatory requirements and to meet customers’ expectations. The International Organization for

Standardization (ISO) 9001 standard is an example of a QMS used internationally for standardizing

business performance.

Aside from the requirements of the quality system, there are many benefits to implementing an

effective QMS. These include:

• Greater efficiency

• More consistency

• Increased understanding of customer needs

• Improved risk management

• Better communication

As with your market authorization applications, it is a good practice to hire external consultation (or to

bring on expertise internally) to establish your post-market QMS.

Resources:

ASQ: Learn about Quality Using an ASQ Database of Quality Resources

Article: What Is a Quality Management System?

NIH SEED: Quality Management Systems for Medical Devices

6.2 Quality System Regulation

The minimum QMS expectation is for your device to meet the current good manufacturing practice

(cGMP) requirements mandated by CDRH and listed in the quality system regulation. cGMP regulation

also includes design controls covered in the Safe Medical Devices Act. During annual inspections, FDA

will review QMS documentation for each of the criteria in the quality system regulation.

The quality system regulation specifies certain processes related to design and manufacturing to which

medical device manufacturers must adhere if their products are sold in the U.S. Many companies (even

small ones) have appointed a specialist to manage device quality, and part of that role is ensuring

requirements of the quality system regulation are met. This regulation shows the type of controls the

quality manager will be responsible for putting in place such as: design, purchasing, traceability,

production, acceptance criteria, corrective and preventive actions (CAPA), packaging, handling,

training, and documentation.

The CAPA are very important for most manufacturers and FDA investigators. The CAPA process

investigates and solves problems, identifies causes, and takes action to prevent any recurrence of the

problem. FDA understands that problems occur, so to ensure the ongoing quality of the device,

manufacturers are required to maintain a complete record of the problems and their corresponding

solutions.

Another important part of the quality system regulation is the device master record and device history

record. The device master record specifies all components of the current device design and

manufacturing process. The device history record specifies the history of all changes (major and minor)

to the device over time. When you make a change to your device that does not require a new FDA

submission, the change must still be reflected in your records. During future inspections, FDA will

review all device changes and ensure that the decision to submit or not submit a new Market

Authorization application is valid.

You should learn as much as possible about requirements for your manufacturing practices before your

device enters the marketplace.

6.3 International Standards

Companies planning on seeking FDA approval and introducing their medical device into international

trade must also consider the International Organization for Standards (ISO) 9001 criteria as part of

their QMS planning. The design and manufacturing of medical devices is specifically covered in ISO

13485:2016 and is expected to be incorporated by FDA into the quality system regulation.

If you extend your business to outside the U.S., it may be helpful to work with a regulatory consultant

to understand the QMS requirements (in addition to other premarket considerations) for the different

countries where you will market your device.

If you are implementing a broader international QMS, you should maintain documentation specific to

the quality system regulation for your FDA inspections.

7 Modifying a Device after Market Authorization

This section focuses on devices that have already obtained regulatory

clearance or approval. If your device is currently marketed in the U.S., you

should consider whether iterative changes to your device are significant

enough to require a new market authorization submission. The following

sections focus on considerations that may be applicable to medical devices that involve changes to the

intended use, risk level, clinical utility, or underlying technology of existing devices.

Changing the intended use, clinical utility, or underlying technology of your

medical device may require submitting a new marketing authorization to CDRH.

7.1 Evidence from Outside the U.S.

You should consider evidence of device performance collected elsewhere in the world to help support

a U.S. FDA premarket application—for example, test results based on international standards.

However, if performance data is gathered exclusively outside the U.S., it may not be sufficient to

support a U.S. market authorization request.

If you are exclusively seeking regulatory approval in the U.S., you should also be aware that export of

your device will be limited to countries that recognize FDA’s authority.

If your device is already on the market outside the U.S., you may already be familiar with the FDA

import and export requirements.

The main consideration, as outlined above, is whether international data can be utilized to support

your FDA application. Two of the most important considerations regarding medical device imports and

exports are gathering of international clinical data under good clinical practices (international quality

standards), and that the data is representative of the intended use population.

Note that for devices marketed in other parts of the world, different countries have different

regulatory requirements. Examples are the Medical Device Directive of the European Union (which

grants the CE Mark), the Pharmaceuticals & Medical Devices Agency of Japan, and the Therapeutic

Goods Administration of Australia.

Resources:

FDA: Importing Medical Devices and Radiation-Emitting Electronic Products into the U.S.

FDA: PMA Import/Export

7.2 Minor Changes to a Device

If you are making a change to the form or function of a device that does not change the intended use

or risk level of the technology, you may have an opportunity for a more straightforward regulatory

path. For very minor changes, such as bug fixes, a new submission to FDA may not be necessary at all

but the changes must be documented in the quality management system (see Section 6).

If you are submitting a new 510(k), with your own device as the predicate, you might consider if the

Special 510(k) program is applicable. If no new data is needed to evaluate the change—or if any new

data can be summarized by well-established methods—then this faster turnaround version of a 510(k)

submission is applicable. If this is your first Special 510(k), you should contact CDRH to clarify if the

Special 510(k) path is appropriate for the change you are proposing. This determination is usually

based on an evaluation of the test methods and whether they are “well established.”

Resource:

FDA: Guidance on Special 510(k) Program

7.3 Substantive Changes to a Device

Significant changes to a device must be researched and documented, and typically require a new

Market Authorization submission to FDA.

Figure 7. Making modifications to a device already on the market

7.3.1 Benefit-Risk Ratio

Some changes to a device create new risk and thus may impact the risk classification for a device. For

example, dental bone grafting material can be a Class II (medium-risk) device when it does not contain

a biologic component. If the material is changed to include a biologic, then it is Class III (high-risk)

device due to increased complexity and more potential for adverse events.

In most cases, the expectation is that new benefits will outweigh new risks. FDA has issued a guidance

for benefit-risk decisions related to new/high-risk devices. The guidance includes worksheets to help

evaluate risks quantitatively.

Other useful tools for evaluating benefits versus risks include the De Novo database and PMA

database. For each granted De Novo and each approved PMA, FDA posts a publicly accessible decision

summary, or summary of safety and effectiveness. These summaries typically include insight into the

FDA evaluation of benefits and risks, with each identified risk including a mitigation strategy. The

expectation is not for a device to have no risks, but instead for its risks to be identified and controlled

to the extent possible.

Resources:

FDA: Factors to Consider When Making Benefit-Risk Determinations in Medical Device Premarket

Approval and De Novo Classifications

FDA: Risk and Risk Mitigation Case Study

7.3.2 New Intended Use

If you are developing a currently marketed device, you might be exploring a new use case for the

technology. This can happen even if the underlying technology is completely unchanged. For example,

an existing device may be used to ease breathing during seasonal allergies, but you may also be testing

it for use in sleep apnea cases.

If you are proposing a new intended use, you will likely need to submit an

entirely new FDA submission.

With respect to the innovator’s device that is currently on the market, a new intended use could be:

• Different from their device currently on the market

• Different from all other devices currently on the market

For the prior, you should seek a new predicate device, if you wish to utilize the 510(k) pathway. For the

latter and otherwise, you would need to prepare a PMA. In either case, it is a best practice to discuss

the new intended use during a pre-submission meeting with FDA.

If the new intended use is to benefit patients (treatment/diagnosis) with diseases or conditions that

affect not more than 8,000 individuals in the U.S., you may be eligible to submit an HDE application if

you meet the requirements for HUD designation.

Resources:

FDA: Getting a Humanitarian Use Device to Market

FDA: Humanitarian Use Device (HUD) Designations

FDA: HUD Program Webinar

NIH SEED: Humanitarian Device Exemption Article

7.3.3 New Clinical Trial

Some device studies rely on clinical data. When you propose major changes or supplements to these

devices, a new clinical trial may need to be designed and conducted.

As mentioned previously, an IDE from FDA often precedes a new clinical trial. Pre-IDE meetings with

FDA can be especially helpful for innovators who have never been official investigators of a clinical trial

before, or if the proposed trial protocols may be unfamiliar to FDA.

You should have clearly specified next steps for your regulatory plan upon completion of the clinical

trial. Allowance of an IDE from FDA does not necessarily mean FDA agrees the trial is sufficient to

support a marketing application.

Resources:

NIH: ClinicalTrials.gov

NIH: ClinicalTrials.gov Registration and Reporting

7.3.4 Real-World Evidence from Routine Clinical Care

Some devices on the market involve extensive collection of data as part of routine clinical care. One

such example is a continuous glucose monitor, which provides the patient with trends and statistics on

their blood sugar. For currently marketed devices with a large pool of existing clinical data, that data

can be used as evidence to support a new design or use for a medical device. FDA calls this type of

supporting information real-world evidence (RWE), and it is a useful mechanism for reducing the

scope and/or need for a traditional clinical trial.

FDA is eager to accept data from existing/ongoing sources, rather than requiring a controlled clinical

trial. However, FDA will still require statistical and clinical factors to be directly addressed in the

application. If RWE is sufficient, that will be accepted; if not, then data from a clinical study may be

required to augment the RWE.

Data is powerful and increasingly available—whether from health records,

wearables, academic articles, or billing/claims. If you find RWE that applies to a

new use of your device, talk to FDA.

FDA CDRH has issued guidance on the use of RWE to support marketing applications. Data is powerful

and increasingly available—whether from health records, wearables, academic articles, or

billing/claims. If you have not mentioned RWE, it is worth discussing with FDA if there are external data

sources that could be leveraged in your application submission.

Resources:

FDA: Guidance on Using Real-World Evidence to Support Regulatory Decision-Making for Medical

Devices

FDA: Webinar on Using RWE to Support Regulatory Decision-Making for Medical Devices

FDA: Framework for FDA’s Real-World Evidence Program

8 Additional Resources

FDA created a series of fictional case studies for the National Medical Device Curriculum. These case

studies are designed to help academic institutions and science and technology innovators understand

FDA’s medical device regulatory processes.

• Choosing the Right Regulatory Pathway for Medical Devices

• Freedom from Unacceptable Risk

• PMA Approval of Medical Devices

• 510(k) Medical Device Submissions

• Regulatory Pathway for a Humanitarian Device Exemption

• Using De Novo Pathway for Low to Moderate Risk Devices

• Seeking Early Feedback from FDA through the Pre-Submission Program

• Investigational Device Exemption Process

National Institutes of Health Small Business Resources:

NIH Small Biz Hangouts video: Finding the Right Regulatory Consultant

NIH Small Biz Hangouts video: Conquering the (Regulatory) Basics and Navigating the FDA Website

NIH SEED: CDRH Small Business Support – The Division of Industry and Consumer Education (DICE)

NIH SEED: Guidance and Considerations for Selecting a Regulatory Consultant

NIH SEED: Medical Device Regulatory Case Study #1