a

e

o

l

o

h

g

c

i

c

r

a

A

l

r

R

o

e

f

s

r

e

e

a

t

r

n

c

e

h

C

T

o

h

i

e

n

U

o

t

n

n

i

v

A

e

n

r

s

a

i

S

t

y

a

t

o

f

s

T

e

x

a

Intensive Pedestrian Survey of

Maverick Creek Greenway Trail System,

San Antonio, Bexar County, Texas

by

Antonia L. Figueroa

REDACTED

Texas Antiquities Permit No. 8583

Principal Investigator

Paul Shawn Marceaux

Prepared for:

Bain Medina Bain, Inc.

7073 San Pedro Avenue

San Antonio, Texas 78216

Preserving Cultural Resources

Prepared by:

Center for Archaeological Research

The University of Texas at San Antonio

One UTSA Circle

San Antonio, Texas 78249

Archaeological Report, No. 470

© 2019

Intensive Pedestrian Survey of

Maverick Creek Greenway Trail System,

San Antonio, Bexar County, Texas

by

Antonia L. Figueroa

REDACTED

Texas Antiquities Permit No. 8583

Principal Investigator

Paul Shawn Marceaux

Prepared for:

Bain Medina Bain, Inc.

7073 San Pedro Avenue

San Antonio, Texas 78216

Prepared by:

Center for Archaeological Research

The University of Texas at San Antonio

One UTSA Circle

San Antonio, Texas 78249

Archaeological Report, No. 470

©2019

iii

Intensive Pedestrian Survey of Maverick Creek Greenway Trail System, San Antonio, Bexar County, Texas

Abstract:

The University of Texas at San Antonio (UTSA) Center for Archaeological Research (CAR), in response to a request from

Bain Medina Bain, Inc., conducted an intensive pedestrian survey of the proposed Maverick Creek Greenway Trail System, in

northwest San Antonio, Bexar County, Texas. The work was completed on October 4, 12, and December 21, 2018. The Area of

Potential Effect (APE) consisted of a 1-km (0.6-mile) proposed trail that ran parallel to Babcock Road along Maverick Creek

and Huesta Creek. The proposed trail begins at Bamberger Park and Huesta Creek (off old Babcock Road) and continues north

to the intersection of UTSA Boulevard and Babcock Road. The Maverick Creek trail segment is on City of San Antonio-owned

property and the project includes public funding. Therefore, the project falls under the review authority of the City of San

under the Texas Antiquities Code with Texas Antiquities Permit No. 8583. Paul Shawn Marceaux served as the Principal

Investigator, and Antonia L. Figueroa served as Project Archaeologist.

During the archaeological investigations, 23 shovel tests were excavated, and one site (41BX2263) was documented. Site

of a light scatter of late nineteenth- to early twentieth-century material found in two shovel tests. CAR recommends site

41BX2263 is not eligible for State Antiquities Landmark designation or listing on the National Register of Historic Places.

CAR recommends no further archaeological work and that construction of this section of the Maverick Creek Greenway Trail

proceed as it will not impact any previous or new archaeological sites or features. However, in the event that construction

iv

Abstract

This page intentionally left blank.

v

Intensive Pedestrian Survey of Maverick Creek Greenway Trail System, San Antonio, Bexar County, Texas

Table of Contents:

Abstract ........................................................................................................................................................................................iii

List of Figures.............................................................................................................................................................................vii

List of Tables................................................................................................................................................................................ ix

Acknowledgements...................................................................................................................................................................... xi

: Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................. 1 Chapter 1

Area of Potential Effect .............................................................................................................................................................. 1

Report Organization ................................................................................................................................................................... 1

Chapter 2: Project Setting ............................................................................................................................................................. 5

Environmental Setting ................................................................................................................................................................ 5

Culture History ........................................................................................................................................................................... 6

Protohistoric (ca. 1528-1700)................................................................................................................................................... 6

Spanish Colonial Period in San Antonio (ca. 1700-1800) ....................................................................................................... 7

Early Texas (1800-1836) ......................................................................................................................................................... 7

Republic of Texas (1836-1845) ................................................................................................................................................ 7

State of Texas (1845-1900) ...................................................................................................................................................... 7

Previously Recorded Sites.......................................................................................................................................................... 8

Chapter 3: Field and Laboratory Methods .................................................................................................................................. 11

Field Methods........................................................................................................................................................................... 11

Laboratory Methods ................................................................................................................................................................. 11

Chapter 4: Results of the Field Investigations ............................................................................................................................ 13

Pedestrian Survey and Shovel Testing...................................................................................................................................... 15

Site 41BX2263 ......................................................................................................................................................................... 16

Chapter 5: Summary and Recommendations.............................................................................................................................. 21

References Cited ......................................................................................................................................................................... 23

vi

Table of Contents

This page intentionally left blank.

vii

Intensive Pedestrian Survey of Maverick Creek Greenway Trail System, San Antonio, Bexar County, Texas

List of Figures:

Figure 1-1. Location of the APE with satellite imagery and proposed amenities: A) amphitheater; B) playground;

C) trail connections; and D) parking lot .................................................................................................................................. 2

Figure 1-2. The APE depicted on an ESRI topographic map ....................................................................................................... 3

Figure 2-1. Maverick Creek near the intersection of Hausman Road and Babcock Road, facing north...................................... 5

Figure 2-2. Huesta Creek crossing the southern portion of the APE, facing east ......................................................................... 6

Figure 2-3. Previously recorded archaeological sites within 1 km (0.6 mile) of the APE............................................................ 9

Figure 4-1. Aerial map of APE with shovel tests ........................................................................................................................ 13

Figure 4-2. Existing trail that crosses west under Babcock Road............................................................................................... 14

Figure 4-3. The northern end of the APE at UTSA Boulevard and Babcock Road, facing south .............................................. 14

Figure 4-4. Shovel Test 8, terminated at 18 cmbs (7.08 in.) due to asphalt................................................................................ 16

Figure 4-5. Site 41BX2263 on an ESRI topographic map.......................................................................................................... 17

Figure 4-6. Shovel Test 3, facing north....................................................................................................................................... 18

Figure 4-7. Maverick Creek and culvert west of ST 3, facing west ........................................................................................... 19

Figure 4-8. CAR crewmember excavating ST 17, facing south ................................................................................................. 19

viii

List of Figures

This page intentionally left blank.

ix

Intensive Pedestrian Survey of Maverick Creek Greenway Trail System, San Antonio, Bexar County, Texas

List of Tables:

Table 2-1. Previously Recorded Sites within 1 km (0.6 mile) of the APE.................................................................................... 8

Table 4-1. Shovel Test Results .................................................................................................................................................... 15

Table 4-2. Artifacts Recovered from 41BX2263 ........................................................................................................................ 18

x

List of Tables

This page intentionally left blank.

xi

Intensive Pedestrian Survey of Maverick Creek Greenway Trail System, San Antonio, Bexar County, Texas

Acknowledgements:

This project would not have been completed if not for the support of several individuals and agencies. Thank you to Casey

Thank you to Bain Medina Bain, Inc., the client, for providing us the opportunity to work on this project. Also, thank you to

Jason Perez. Dr. Jessica Nowlin provided mapping and imaging support. Dr. Kelly Harris edited this report, and Dr. Paul Shawn

Marceaux served as Principal Investigator. Finally, a special thanks to Dr. Raymond Mauldin for his comments and suggestions

xii

Acknowledgements

This page intentionally left blank.

1

Intensive Pedestrian Survey of Maverick Creek Greenway Trail System, San Antonio, Bexar County, Texas

Chapter 1: Introduction

An intensive pedestrian survey and shovel testing along the

proposed trail alignment for the Maverick Creek Greenway

Trail System was performed on October 4, 12, and December

21, 2018, by The University of Texas at San Antonio (UTSA)

Center for Archaeological Research (CAR). The Maverick

Creek Greenway Trail System is located in northwest San

Antonio, Bexar County, Texas (Figure 1-1). The work was

in response to a request from Bain Medina Bain, Inc. The

project was completed under the guidance of the City of

The project fell under the Texas Antiquities Code and was

performed under Texas Antiquities Permit No. 8583. The

Principal Investigator was Paul Shawn Marceaux, and

Antonia L. Figueroa served as the Project Archaeologist.

The goal of the survey and shovel testing was to identify and

document all prehistoric and/or historic archaeological sites

that may be impacted by the proposed trail. To accomplish

the goal, CAR completed a combination of background

research, pedestrian survey, and shovel testing across the Area

of Potential Effect (APE). CAR staff excavated 23 shovel

tests, and one site (41BX2263) was documented. However,

further work was not recommended, and CAR recommends

the proposed trail can be completed as planned.

Area of Potential Effect

The APE consisted of approximately 1 kilometer (km; 0.6

mile) of proposed trails along Maverick Creek and proposed

amenities that include an amphitheater, playground, trail

connections, and parking lot (Figure 1-1). The trail will run

north to south along Maverick Creek from the UTSA campus

(near the intersection of Babcock Road and UTSA Boulevard)

to Bamberger Park. The easement of the proposed trail and

amenities is 9-meters (m; 30-ft.) wide and is depicted on the

ESRI topographic map in Figure 1-2.

Report Organization

The remainder of the report consists of four additional

chapters. Following this introduction, Chapter 2 reviews

the project setting, which includes the physical environs of

the APE and previous archaeology conducted within 1 km

the project are presented in Chapter 3. Chapter 4 documents

the results of the pedestrian survey and shovel tests, while

Chapter 5 provides a summary and recommendation based

Chapter 1: Introduction

2

Figure 1-1. Location of the APE with satellite imagery and proposed amenities: A) amphitheater; B) playground; C) trail

connections; and D) parking lot.

3

Intensive Pedestrian Survey of Maverick Creek Greenway Trail System, San Antonio, Bexar County, Texas

Figure 1-2. The APE depicted on an ESRI topographic map.

Chapter 1: Introduction

4

This page intentionally left blank.

5

Intensive Pedestrian Survey of Maverick Creek Greenway Trail System, San Antonio, Bexar County, Texas

Chapter 2: Project Setting

This chapter presents a brief description of the project

area’s physical environment, including soils, climate,

and vegetation. It provides a brief description of previous

archaeological investigations conducted within 1 km (0.6

mile) of the APE.

Environmental Setting

The San Antonio region is described as a moderate,

subtropical, humid climate with generally cool winters and

hot summers (Norwine 1995; Taylor et al. 1991). The average

high temperature reported for San Antonio in 2017 was 69.6°

F, and the average low was 45.5° F (U.S. Climate Data 2018).

The soil types that are present in the APE consist of Sunev

loam (VaB), Anhalt clay (Ca), Tinn and Frio soils (Tf),

and Lewisville silty clay (LvB). Terrain setting, slope, and

Sunev soils are characterized by deep, well-drained soils that

occur in alluvium settings. The Anhlat soils are described as

moderately deep and well drained. This soil series occurs

on hillslopes, toe slopes, and base slope landforms. Tinn

and Frio soils are moderately well-drained soils that occur

series are silty clay soils that are deep and well drained

(NRCS 2018).

There are two waterways within the APE. Maverick Creek

runs parallel to the proposed trail, while Huesta Creek

crosses the southern portion of the APE (Figures 2-1 and

2-2). Both creeks are part of the Leon Creek watershed. Leon

Creek runs north to south through the west-central portion of

the county, ultimately draining into the Medina River south

of San Antonio. Huesta Creek, a secondary branch of Leon

Creek, runs close to where the proposed trail intersects with

the existing Bamberger Park Hike and Bike Trail.

Three plant communities are represented in the 1-km (0.6-

mile) stretch of the APE and include dense woodlands,

tallgrass savannah, and short grass/tree community (NRCS

2018). The dense woodland community has a closed

canopy and is dominated by hardwoods like pecan (Carya

illinoinensis) and oak (Quercus) species. The lack of grasses

in the dense woodland plant community is due to the shade

provided by the canopy. The tallgrass savannah plant

community has a 10 percent canopy cover and is dominated

Figure 2-1. Maverick Creek near the intersection of Hausman Road and Babcock Road, facing north.

6

Chapter 2: Project Setting

Figure 2-2. Huesta Creek crossing the southern portion of the APE, facing east.

by little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), big bluestem

(Andropogon gerardii) and Indian grasses (Sorghastrum

nutans). The shortgrass/tree community has a hardwood

over story of 15-30 percent that is predominantly mesquite

(Prosopis). The typical grasses in the shortgrass/tree

community include sideoats grama (Bouteloua curtipendula)

and plains lovegrass (Eragrostis intermedia; NRCS 2018).

Culture History

This section summarizes the culture history for the region.

The one site recorded during the project dated to the historic

period, while no prehistoric resources were recorded or

observed. Therefore, a detailed discussion of the prehistory

of the region will not be provided. The discussion begins with

the Protohistoric period and concludes with the twentieth

century. The reader may consult Collins (2004) for a detailed

summary of the prehistory of Central Texas that begins

during the Paleo-Indian period (11,500-8800 BP) and ends

with the Late Prehistoric (1200-350 BP). Furthermore, the

culture history periods that are discussed below were adapted

from previous CAR reports (Figueroa and Mauldin 2005;

Fox et. al 1997; Thompson and Figueroa 2005).

Protohistoric (ca. 1528-1700)

It has been stated by some scholars (Wade 2003) that the

Protohistoric Period may coincide with the end of the Late

Prehistoric period (Collins 2004). The Protohistoric period

begins with the Early Spanish explorations in Texas (ca.

7

Intensive Pedestrian Survey of Maverick Creek Greenway Trail System, San Antonio, Bexar County, Texas

1528) and terminates with the establishment of a strong

Spanish presence in the region during the late 1600s and early

1700s. During this period, there is sporadic contact between

the native groups in the region and European explorers. The

Spanish arrived in present-day San Antonio during the late

1600s when General Alfonso de Leon visited the area. There

are few Protohistoric period sites that have been documented

in South Texas (e.g., Hall et al. 1986; Inman et al. 1998;

Mauldin et al. 2004).

Spanish Colonial Period in San Antonio

(ca. 1700-1800)

The establishment of Spanish presidios in the region

was prompted by threats from the French in the region

(Moorhead 1991:27). In 1690, the Spanish founded Mission

San Francisco de los Tejas, near present day Nacogdoches,

along with Santismo Nombre de Maria, on the banks of the

Neches River. The missions did not survive very long, and

Rio Grande River, with the founding of Mission San Juan

Bautista (Weddle 1968).

In 1718, the the Presidio San Antonio de Béxar and Mission

San Antonio de Valero were established near the headwaters

of San Pedro Creek, by Don Martín del Alarcón, the governor

of Coahuila and the San Antonio region (Chipman 1992:14;

Hoffman, translator 1937). The goal of the San Antonio de

Bexar presidio and the occupying soldiers was to protect the

surrounding lands and inhabitants. Moreover, San Antonio

served as a way station, along the Spanish Camino Real,

that was located between present day Mexico and East Texas

(McGraw et al. 1991). Marqués de San Miguel de Aguayo

replaced Alarcón as the governor and captain general of

Coahuila and Texas (Buerkle 1976:52) in 1719. In his new

position, Aguayo led an expedition into Texas with the aim

of re-establishing a Spanish presence to the region that began

with eight month stay in East Texas. (Buerkle 1976:52).

By 1720, Mission San José y San Miguel de Aguayo,

Nuestra Señora de la Purisima Concepción de los Hasinai,

San Francisco de Espada and San Juan Capistrano were

established along the San Antonio River. The establishment

occurred in 1731, and it became home to Canary Islanders

(Habig 1968).

There was a major shift between colonial powers in the

region with the on-set of the Seven Year War (1756-1763). It

was at this time East Texas missions and settlements began

to dissolve, as populations began to relocate to San Antonio

(Habig 1968). By 1790, the San Antonio missions began to

decline and Manuel Silva, under the College of Zacatecas,

recommended that Mission San Antonio de Valero be

secularized. There was a shortage of clergy to service the

missions, as well as there was a lack of indigenous workers

to maintain their associated farmlands (Cox 2005). After

1794, the associated lands were transferred to the remaining

Mission Indians and other individuals who lived in the area

(Habig 1968).

Early Texas (1800-1836)

Dangers to the inhabitants of the San Antonio region, in the

form of Indian raids and cattle smuggling became concern as

the area continued to be under Spanish control. This problem

prompted the arrival of the Compania Volante de San Carlos

del Alamo de Parras from Coahuila, in 1803 (Tarin 2010).

The soldiers occupied the abandoned Mission San Antonio

de Valero, giving the landmark its current designation as the

Alamo (see Cox 2005). Disgruntlement with the Spanish

independence began with the Hidalgo revolt of 1810. After

Mexico gained its independence from Spain in 1821, a new

constitution was created with Texas and Coahuila merging

as one state. However, San Antonio de Béxar remained a

separate department (Fox et al. 1997).

Spain struggled to regain control of Mexico and Texas. In

1833, Stephen F. Austin asked San Antonio to provide

February of 1836, the Mexican army arrived in San Antonio.

Texan troops taking position in the Alamo were assaulted

defeated and caught at the Battle of San Jacinto later that year

Republic of Texas (1836-1845)

Sam Houston, was inaugurated in 1836. The Texas Congress

set the boundaries for the newly formed republic as the Rio

Grande in the south and Louisiana eastern boundary (Nance

2004). At this time San Antonio’s population increased due to

was elected in 1837. However, Mexico refused to recognize

Texas as independent and political tensions continued up

Mexico. (Fox et al. 1997).

State of Texas (1845-1900)

The Texas State Constitution was approved by the U.S

Congress in 1845, and Texas was admitted as a state. This act,

8

Chapter 2: Project Setting

along with the lack of agreement on boundary lines, prompted

the war between the U.S. and Mexico. As a result, General

Zachary Taylor and his troops advanced to the Rio Grande in

May of 1846, an area of land that the Mexican government

viewed as its own, and war was declared. After a series of

battles, the U.S. military occupied Mexico City in August of

1848 established the Rio Grande as a boundary, and it gave

the United States additional territories in return for monetary

compensation. The U.S. troops retreated Mexico in June of

that same year (Bauer 1974; Wallace 1965).

Not soon after this war between Mexico and the United

States, Texas, a new state to the Union, had to grapple with its

position on slavery. During the Civil War, Texas did not suffer

as much economically as the rest of the Union, but there was

a shortage of commodities in San Antonio. More importantly,

Texans fought on both sides of the war contributing to the

civil strife that effected the rest of the Union. Finally, in June

of 1865, Confederate generals serving in the Texas region

surrendered signaling the end of the Civil War (Campbell

2010; Fox et al. 1997).

During the late nineteenth century, an economic boom

occurred in San Antonio with the arrival of the Galveston,

Harrisburg, and San Antonio Railroad. The railroad helped

introduce new to the area that gave support to new merchant

and saloon businesses (Fox et al. 1997). At the beginning

of the twentieth century, the population of San Antonio was

just over 53,000 (Fox et al. 1997). While San Antonio proper

continued to grow during the nineteenth and early twentieth

centuries, most farmsteads and ranches were established on

the outskirts of Bexar County (Fox et al. 1997; Thompson

and Figueroa 2005). Germans began to migrate to the Texas

region between 1844 and 1847, and it was at this time that

Castroville became the heart of the Alsatian colony. Many

German settlers choose the San Antonio area due to better

consisted of German immigrants (Jordan 1977).

There has been archaeological evidence of a historic

farmsteads and ranching complexes in the area surrounding

the APE. For instance, a German farmstead (41BX1600)

dating to the nineteenth century was recorded adjacent

to French Creek, which is 1.6 km (1 mile) from the APE

(Thompson and Figueroa 2005). Evidence of a twentieth-

century ranching complex has also been documented off

Huesta Creek that is only 0.5 km (0.3 mile) from the APE

(Galindo 2000).

Previously Recorded Sites

There are six previously recorded sites within 1 km (0.6

mile) of the APE (Table 2-1; Figure 2-3). Two of the sites

(41BX41 and 41BX1811) are open camp sites. Four of the

sites are lithic scatters, while only one of the previously

recorded sites is historic and was documented by Galindo

(2000) as part of the Hausman Road Improvements project.

This information was obtained from the Texas Site Atlas

(THC 2018) and cultural resource management reports.

Geo-Marine conducted investigations along Leon Creek in

2007, which included a revisit of the open campsite 41BX41

2018). Texas A&M documented two of the sites (41BX1419

and 41BX1420) during investigations conducted on UTSA

property (Clabuagh 2000). SWCA (Houk and Skoglund

2002) conducted work again on the UTSA campus in 2002

and revisited three of the sites (41BX440, 41BX1420,

and 41BX1419) documented by Texas A&M. None of

the previously recorded sites are eligible for listing in the

National Register of Historic Places nor are any of the sites

designated as State Archaeological Landmarks.

Table 2-1. Previously Recorded Sites within 1 km (0.6 mile) of the APE

Site Site Type/Time Period Reference

41BX41 open camp site Osburn 2008; THC 2018

41BX440 lithic scatter/unknown prehistoric Houk and Skoglund 2002; THC 2018

41BX1419 lithic scatter/unknown prehistoric Clabaugh 2000; Houk and Skoglund 2002

41BX1420 lithic scatter/unknown prehistoric Clabaugh 2000; Houk and Skoglund 2002

41BX1811 open camp site THC 2018

41BX1810 unknown prehistoric Dowling et al. 2010

41BX1858 ranching complex/historic Galindo 2000

9

Intensive Pedestrian Survey of Maverick Creek Greenway Trail System, San Antonio, Bexar County, Texas

Redacted Image

Figure 2-3. Previously recorded archaeological sites within 1 km (0.6 mile) of the APE.

10

Chapter 2: Project Setting

This page intentionally left blank.

11

Intensive Pedestrian Survey of Maverick Creek Greenway Trail System, San Antonio, Bexar County, Texas

Chapter 3: Field and Laboratory Methods

Field Methods

To identify and document prehistoric and historic sites CAR

archaeologists completed a 100 percent pedestrian survey of

the approximately 1-km (0.6-mile) proposed trail corridor and

its associated amenities. In addition to the pedestrian survey,

23 shovel tests were excavated in order to locate and document

subsurface cultural deposits. Shovel tests were approximately

30 cm (11.8 in.) in diameter and excavated to depths of 60

cm (23.6 in.) below the ground surface. Shovel tests were

excavated in arbitrary 10-cm (3.9-in.) levels, and all soil

matrixes were screened through one-quarter inch hardware

cloth. The excavator recorded the results of the shovel tests

on a standardized form. For each 10-cm (3.9-in.) level, a

description of the soils and documentation of any recovered

cultural material was recorded. At the conclusion of shovel

test location was plotted with a GPS Trimble Unit. The CAR

staff collected all artifacts recovered from shovel tests.

For the purposes of this survey, an archaeological site was

15-m (49 ft.) radius (ca. 706.9 m

2

); or (2) a single cultural

feature, such as a hearth, observed on the surface or exposed

in a shovel test; or (3) a positive shovel test containing at least

three artifacts within a given 10-cm (3.9-in.) level; or (4) a

(5) two positive shovel tests located within 30 m (98.4 ft.) of

each other.

Laboratory Methods

All cultural materials and records obtained and/or generated

during the project were prepared in accordance with federal

regulation 36 CFR part 79 and THC requirements for State

Held-in-Trust collections. Artifacts processed in the CAR

laboratory were washed, air-dried, and stored in 4-mm,

zip-locking, archival-quality bags. Acid-free labels were

placed in all artifact bags. Each laser-printed label contains

provenience information and a corresponding lot number.

Field forms were printed on acid-free paper and completed

were placed in labeled archival folders. Digital photographs

were printed on acid-free paper and placed in archival-quality

page protectors. All records generated during the project were

prepared in accordance with federal regulations 36 CFR Part

79 and THC requirements for State Held-in-Trust collections.

be permanently stored at the CAR curation facility.

12

Chapter 3: Field and Laboratory Methods

This page intentionally left blank.

13

Intensive Pedestrian Survey of Maverick Creek Greenway Trail System, San Antonio, Bexar County, Texas

Chapter 4: Results of the Field Investigations

On October 4, 12, and December 21, 2018, the CAR trail. Figure 4-2 shows the existing trail that runs east to

conducted a pedestrian survey of the APE that included the west under Babcock Road. Shovel tests were placed every

excavation of 23 shovel tests (STs; Figure 4-1). CAR staff 100 m (328 ft.) until the northern extent of the APE was

began the shovel testing and pedestrian survey at the south reached at the corner of UTSA Boulevard and Babcock

end of the APE, where the proposed trail meets an existing Road (Figure 4-3).

Redacted Image

Figure 4-1. Aerial map of APE with shovel tests.

14

Chapter 4: Results of the Field Investigations

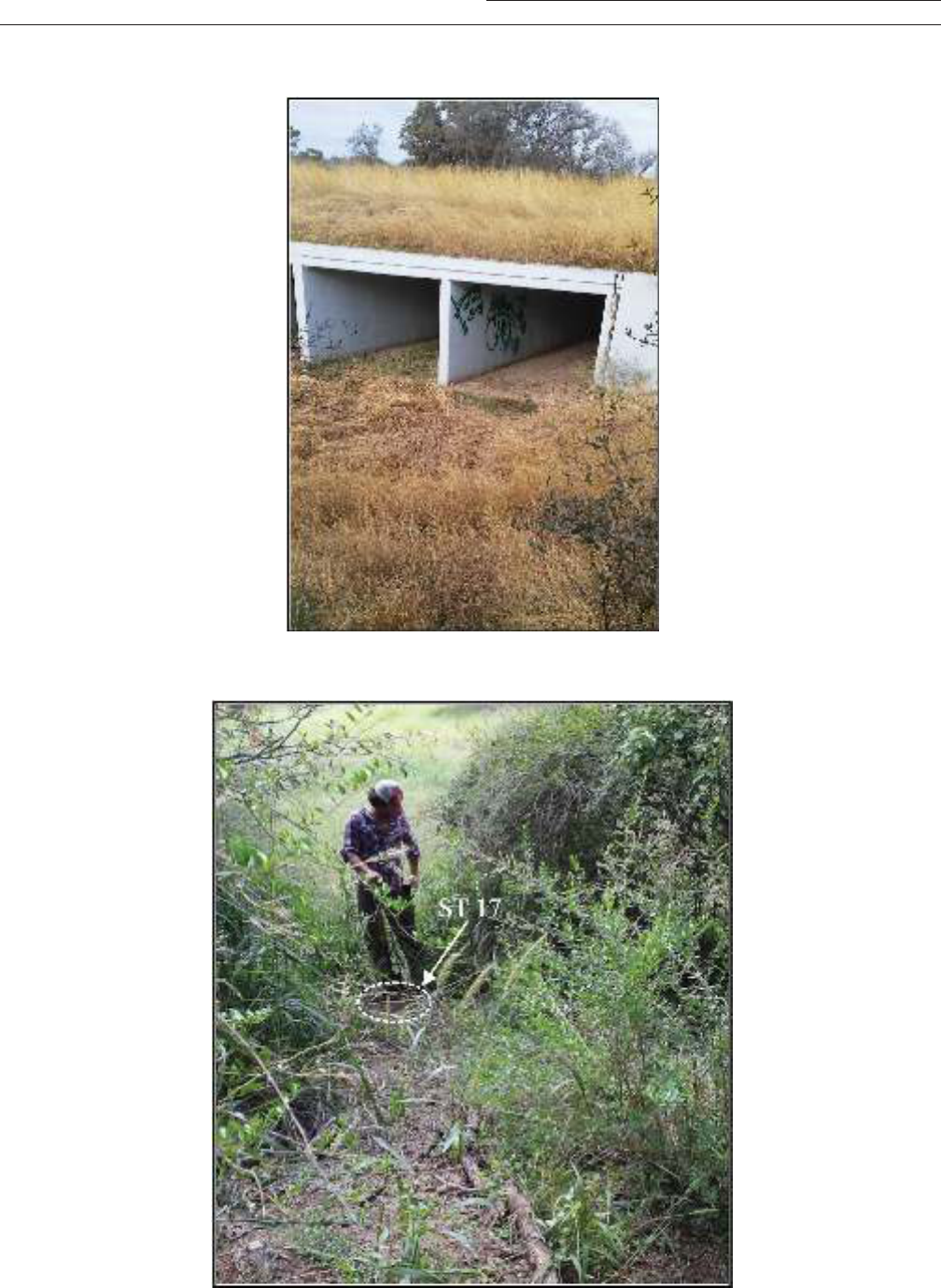

Figure 4-2. Existing trail that crosses west

under Babcock Road.

Figure 4-3. The northern end of the APE at UTSA

Boulevard and Babcock Road, facing south.

15

Intensive Pedestrian Survey of Maverick Creek Greenway Trail System, San Antonio, Bexar County, Texas

Pedestrian Survey and Shovel Testing

excavated along a portion of the proposed trail that would

Table 4-1 displays the results of each shovel test. The northern

connect to an existing trail. Shovel Test 12 terminated prior

extent of the APE and the various utilities at the corner of

to reaching 60 cmbs (23 in.) due to creek gravels, as this part

UTSA Boulevard and Babcock Road are shown in Figure 4-3.

of the APE crossed Maverick Creek (Figure 4-5). Soils in the

Due to the disturbance in the northern portion of the APE, a

APE ranged from a brown (10YR 4/3) clay loam (with high

shovel test was not placed in this area. Only 15 of the shovel

gravel content of 70 percent or more) that was associated with

tests terminated at 60 cm below the surface (cmbs; 23 in.).

shallow soils and found near the creek to a dark grayish brown

The remaining STs were terminated at a more shallow depth

(10YR 3/2) clay associated with deeper soils. Only two (STs

3 and 18) of the 23 shovel tests were positive, and the two

4-4 shows ST 8, which was terminated at 18 cmbs (7.08 in.)

Table 4-1. Shovel Test Results

ST Depth (cmbs) Results Reason for Termination

1 10 negative heavy gravels/bedrock

2 39 negative

3 30 positive bedrock

4 60 negative N/A

5 9 negative

6 40 negative bedrock

7 60 negative N/A

8 18 negative

9 60 negative N/A

10 60 negative N/A

11 60 negative N/A

12 40 negative gravels/bedrock

13 60 negative N/A

14 60 negative N/A

15 60 negative N/A

16 60 negative N/A

17 60 negative N/A

18 60 positive N/A

19 60 negative N/A

20 15 negative gravels/bedrock

21 60 negative N/A

22 60 negative N/A

23 60 negative N/A

16

Chapter 4: Results of the Field Investigations

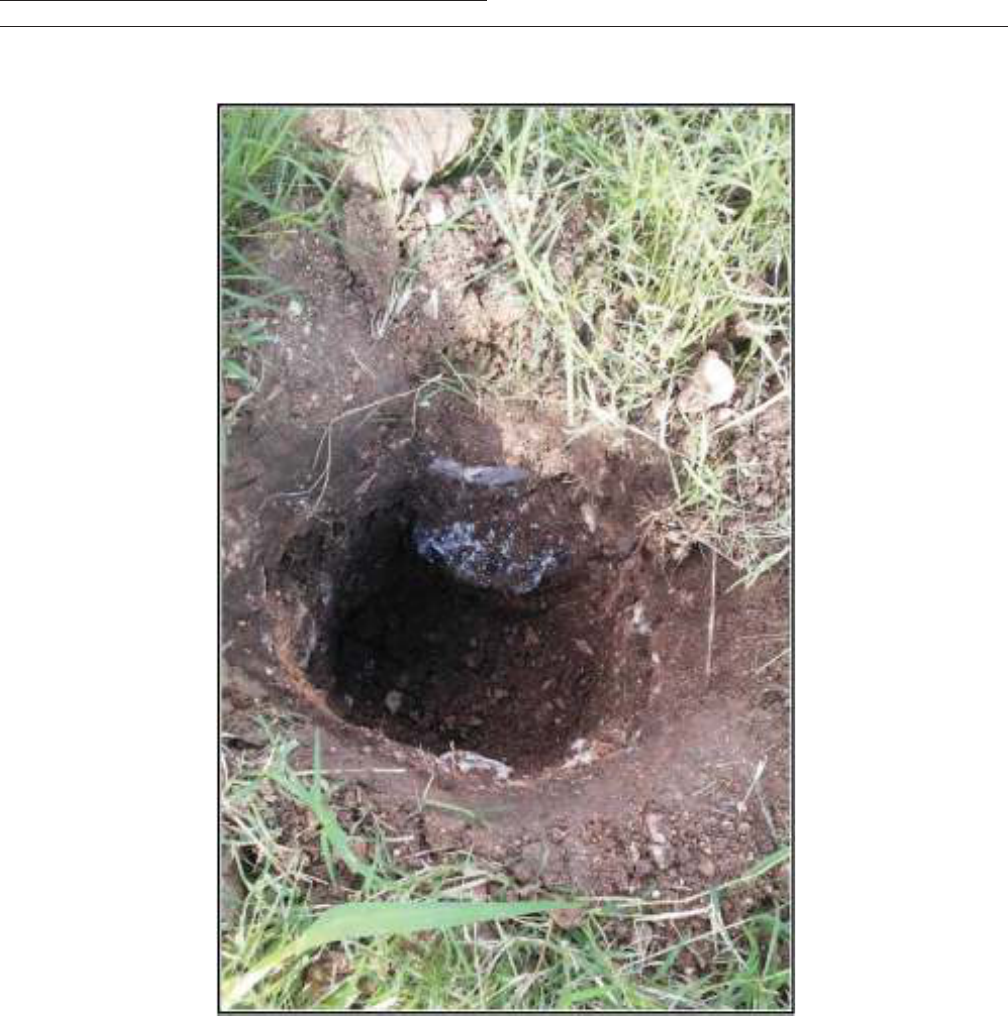

Figure 4-4. Shovel Test 8, terminated at 18 cmbs (7.08 in.) due to asphalt.

Site 41BX2263

Two shovel tests (STs 3 and 18) were positive for cultural

material and designated as site 41BX2263 (Figure 4-5).

Shovel Test 3 contained ceramic (n=2) and glass (n=3), and

all three items were recovered in Level 1 (Figure 4-6). The

ceramics consisted of two undecorated white earthenware

window glass (Table 4-2). Three additional shovel tests (STs

17, 18, and 19) were excavated to delineate the horizontal

extent of the cultural material. Excavating a shovel test

west of ST 3 was not feasible as there was a drop off into

a culvert off that connect to Huesta Creek (Figure 4-7).

Shovel Test 18 was excavated east of ST 3 and was positive

with one piece of undecorated porcelain in Level 4. Shovel

Test 17 was excavated on a slope, south of the ST 3, and

was negative for cultural material (Figure 4-8). Shovel Test

19, accidently dug slightly outside the APE, was excavated

northeast of ST 17 and was also negative for cultural material

(Figure 4-7). All of the material dated to the early 1900s

(Miller 1991; White 1978). A 1953 USGS topographic map

(Helotes, Texas, N2930-W9837.5/7.5) of the project area

did not indicate any structures in the area where the cultural

material was recorded. Due to the low number of artifacts

and lack of structural evidence in the area it was determined

that the cultural material was possibly refuse deposited in

recommended for the site.

17

Intensive Pedestrian Survey of Maverick Creek Greenway Trail System, San Antonio, Bexar County, Texas

Redacted Image

Figure 4-5. Site 41BX2263 on an ESRI topographic map.

18

Chapter 4: Results of the Field Investigations

Figure 4-6. Shovel Test 3, facing north.

Table 4-2. Artifacts Recovered from 41BX2263

ST Level Depth (cmbs) Cultural Material Description Count

3 1 0-10 ceramic undecorated white earthenware rim 2

3 1 0-10 glass aqua 1

3 1 0-10 glass clear 2

18 4 30-40 ceramic undecorated porcelain 1

19

Intensive Pedestrian Survey of Maverick Creek Greenway Trail System, San Antonio, Bexar County, Texas

Figure 4-7. Maverick Creek and culvert west of

ST 3, facing west.

Figure 4-8. CAR crewmember excavating ST 17, facing south.

20

Chapter 4: Results of the Field Investigations

This page intentionally left blank.

21

Intensive Pedestrian Survey of Maverick Creek Greenway Trail System, San Antonio, Bexar County, Texas

Chapter 5: Summary and Recommendations

On October 4, 12, and December 21, 2018, CAR

archaeologists performed an intensive pedestrian survey and

shovel testing in advance of the proposed Maverick Creek

Greenway Trail System located in northwest San Antonio,

Bexar County, Texas. The proposed trail alignment began at

Babcock Road and UTSA Boulevard, just west of Maverick

Creek, and headed south to an existing trail just north of

Bamberger Park and Huesta Creek. A total of 23 shovel tests

were excavated along the 1-km (0.6-mile) long proposed trail

alignment, and one new site (41BX2263) was documented.

Twenty-one shovel tests were negative for cultural material. A

newly documented site 41BX2263 consisted of two positive

shovel tests (STs 3 and 18) containing historic material

(ceramics and glass). Due to the low number of artifacts and

lack of structural evidence in the area, it was determined

the cultural material was possibly refuse deposited in the

of the APE was revealed, between the documented site and

material. CAR recommends site 41BX2263 is not eligible

for State Antiquities Landmark designation or listing on

the National Register of Historic Places. Further work was

not recommended for the site, and CAR recommends the

proposed Maverick Creek Greenway Trail System proceed

as planned.

22

Chapter 5: Summary and Recommendations

This page intentionally left blank.

23

Intensive Pedestrian Survey of Maverick Creek Greenway Trail System, San Antonio, Bexar County, Texas

References Cited:

Bauer, J.

1974 The Mexican War, 1846-1848. Macmillan, New York.

Buerkle, R.C.

1976 The Continuing Military Presence. In San Antonio in the 18th Century, pp. 42-72. San Antonio Bicentennial Heritage Committee.

Campbell, R.B.

2010 Antebellum Texas The Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Electronic document, http://

www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/npa01, accessed April 25, 2019.

Chipman, D.E.

1992 Spanish Texas, 1519-1821. University of Texas Press, Austin.

Clabaugh, P.A.

2000 An Archaeological Survey of Two Proposed Parking Lots along Maverick Creek, West Campus, University of Texas at

San Antonio. Center for Ecological Archaeology. Texas A&M University, College Station.

Collins, M.B.

2004 Archeology in Central Texas. In Prehistory of Texas, edited by T.K. Perttula, pp. 101-126. Texas A&M University Press.

College Station.

Cox, I.W.

2005 Appendix D. History of the “Priest’s House” on Military Plaza. In Test Excavations and Monitoring at 41BX1598: A

Multicomponent Historic Site in Bexar County, Texas, by A.L. Figueroa and R.P. Mauldin, pp. 125-130. Archaeological

Report, No. 360. Center for Archaeological Research, The University of Texas at San Antonio.

Dowling, J.D., M.D. Freeman, and M. Thornton

2010 Archaeological Survey of the Leon Creek Greenway Segment II of the Linear Creekway Program, San Antonio, Bexar

County, Texas. ACI Consulting, Austin.

Figueroa, A.L., and R.P. Mauldin

2005 Test Excavations and Monitoring at 41B1598: A Multicomponent Historic Site. Archaeological Report, No. 360. The

Center for Archaeological Research, The University of Texas at San Antonio.

Fox, A.A., M. Renner, and R.J. Hard

1997 Archaeology at the Alamodome: Investigations of a San Antonio Neighborhood in Transition. Artifacts and Special Studies.

Archaeological Survey Report, No. 238. Center for Archaelogical Research, The University of Texas at San Antonio.

Galindo, M.

2000 Hausman Road Phase I Improvement Project LC-9. SWCA Environmental Consultants, Austin.

Habig, M.A.

1968 The Alamo Chain of Missions. A History of San Antonio’s Five Old Missions. Franciscan Herald Press, Chicago.

Hall, G.D., T.R. Hester, and S.L. Black

1986 The Prehistoric Sites at Choke Canyon Reservoir, Southern Texas: Results of the Phase II Archaeological Investigations.

Choke Canyon Series, No. 10. Center for Archaeological Research, The University of Texas at San Antonio.

24

References Cited

Hoffman, F. L. (translator)

1937 Diary of the Alarcón Expedition into Texas, 1718-1719. Quivira Society Publications 5:39.

Houk, B.A., and T. Skoglund

2002 A Cultural Resource Survey of the University of Texas at San Antonio’s Main Campus, Bexar County, Texas. Cultural

Resource Report No. 02-323. SWCA Environmental Consultants, Austin.

Inman, B.J., T.C. Hill, Jr., and T.R. Hester

1998 Archaeological Investigations at the Tortugas Flat Site, 41ZV155, Southern Texas. Bulletin of Texas Archeological

Society 69:11-33.

Jordan, T.G

1977 German Element in Texas: An Overview. Rice University Studies 63(3).

Mauldin, R.P., B.K. Moses, R.D. Greaves, S.A. Tomka, J.P. Dering, and J.D. Weston

2004 Archaeological Survey and Testing of Selected Prehistoric Sites along FM 48, Zavala County, Texas. Archaeological

Studies Program, Report No. 67, Environmental Affairs Division, Texas Department of Transportation, Austin.

McGraw, A.J., J.W. Clark, Jr., and E.A. Robbins

1991 A Texas Legacy: The Old San Antonio Road and the Caminos Reales. Texas State Department of Highways and Public

Transporation, Austin.

Miller, G.L.

Historical Archaeology 25:1-23.

Moorhead, M.L.

1991 The Presidio: Bastion of the Spanish Borderlands. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman.

Nance, J.M.

2004 Republic of Texas. The Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Electronic document, https://

tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/mzr02, accessed April 26, 2014.

Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS)

2018 Web Soil Survey. United States Department of Agriculture. Electronic document, http://websoilsurvey.nrcs.usda.gov/

app/WebSoilSurvey.aspx, accessed October 22, 2018.

Norwine, J.

1995 The Changing Climate of South Texas: Patterns and Trends. In The Changing Climate of Texas: Predictability and

Implications for the Future, edited, J. Norwine, J.R. Giardino, G.R. North, and J.B. Valdes, pp.138-155. Texas A&M

University, College Station.

Osburn, T.L.

2008 Cultural Resources Overview of the Leon Creek Watershed, Bexar County, Texas. Miscellaneous Reports of Investigations

No. 402. Geo-Marine Incorporated, Plano.

Tarin, R.G.

2010 Second Flying Company of San Carlos De Parras. The Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association.

Electronic document, http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/qhs01, accessed April 25, 2019.

Taylor, F.B., R.B. Hailey, and D.L. Richmond

1991 Soil Survey of Bexar County. Soil Conservation Service. United States Department of Agriculture, Washington D.C.

25

Intensive Pedestrian Survey of Maverick Creek Greenway Trail System, San Antonio, Bexar County, Texas

Texas Historical Commission (THC)

2018 Texas Archaeological Sites Atlas. Electronic document, http://nueces.thc.state.tx.us/view-archsite-form/, accessed

October 2018.

Thompson, J.L., and A.L. Figueroa

2005 Archaeological Survey and Archival Research of the Naegelin Tract (41BX1600) in San Antonio, Bexar County, Texas.

Archaeological Survey Report, No. 354. Center for Archaeological Research, The University of Texas at San Antonio.

U.S. Climate Data

2018 Climate San Antonio-Texas. Monthly. Electronic document, https://www.usclimatedata.com/climate/san-antonio/texas/

united-states/ustx1200, accessed November 2018.

Wade, M.

2003 The Native Americans of the Texas Edward’s Plateau, 1582-1799. 1st ed. Texas Archaeology and Ethnohistory Series.

University of Texas Press, Austin.

Wallace, E.

1965 Texas in Turmoil: The Saga of Texas, 1849-1875. Steck-Vaughn, Austin.

Weddle, R.S.

1968 San Juan Bautista: Gateway to Spanish Texas. The University of Texas Press, Austin.

White, J.R.

1978 Bottle Nomenclature: A Glossary of Landmark Terminology for the Archaeologist. Historical Archaeology 12:58-67.