October 2023

DRAFT

State of Maine Housing

Production Needs Study

Homes to support Mainers and Maine businesses,

now and in the future.

1

Contents

Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................... 2

Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................... 3

Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 3

Approach ................................................................................................................................................... 4

Key Findings .............................................................................................................................................. 6

Measuring Housing Need .......................................................................................................................... 8

Setting Production Goals ........................................................................................................................ 11

Study Approach ..................................................................................................................................... 12

Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 12

Background Research and Existing Studies ............................................................................................. 13

Determining Geographic Boundaries ...................................................................................................... 14

What is happening in Maine’s housing market now? .............................................................. 16

Overview ................................................................................................................................................. 16

Demand-Side Drivers of Housing Need .................................................................................................. 16

Supply-Side Drivers of Housing Need ..................................................................................................... 23

Housing Availability and Affordability ..................................................................................................... 33

How many homes does Maine need today? ................................................................................ 40

Historic Underproduction ....................................................................................................................... 40

Income Distribution ................................................................................................................................ 46

Historic Underproduction Geographic Distribution ................................................................................ 49

How many homes will Maine need to accommodate future population growth? ........ 52

Overview ................................................................................................................................................. 52

Accommodating Population Growth ...................................................................................................... 53

Future Need Geographic Allocation........................................................................................................ 55

Total Need ............................................................................................................................................... 56

Next Steps and Implementation ..................................................................................................... 58

Appendix…………………………………………………………………………………………………………..……………………………….59

2

Acknowledgements

The State of Maine Housing Production Needs Study is the result of a joint effort between MaineHousing,

the Governor’s Office of Policy Innovation & Future (GOPIF), the Maine Department of Economic and

Community Development (DECD), and a broad group of stakeholders. We thank the following individuals

and organizations for their invaluable contributions to conceptualizing, informing, refining, and otherwise

offering direct input to this Study. This Study was prepared by HR&A Advisors.

Steering Committee:

Benjamin Averill, DECD

Hilary Gove, DECD

Erik Jorgensen, MaineHousing

Greg Payne, GOPIF

Technical Working Group:

Sophia Campbell, HR&A Advisors

Kate Dufour, Maine Municipal Association

Erin Fenton, Department of Labor

Suzanne Guild, Maine Association of Realtors

Phillip Kash, HR&A Advisors

Matthew Marks, Associated General Contractors

of Maine

Mark McInerney, Department of Labor

Matthew Panfil, Greater Portland Council of

Governments

Amanda Rector, Maine State Economist

Arjun Sarma, HR&A Advisors

Additional Contributors:

Daniel Brennan, MaineHousing

Ryan Fecteau, GOPIF

Laura Fortman, Department of Labor

Frank O’Hara

Hannah Pingree, GOPIF

Bath Housing

Island Housing Trust

Island Institute

Jewish Community Alliance of Southern Maine

Catholic Charities Maine

Maine Department of Health and Human

Services

Maine Immigrant and Refugee Services

Maine Immigrants’ Rights Coalition

WishRock Housing Group

Laura Semeraro, HR&A Advisors

Christiana Whitcomb, HR&A Advisors

3

Executive Summary

Introduction

In response to a national housing crisis accelerated by the Covid-19 pandemic, policy makers are

increasingly asking, how many and what kind of homes are needed to meet the needs of our constituents and

improve affordability? The scale and nature of housing challenges varies significantly across regions and

places but is driven by a primary underlying cause: housing production dropped precipitously after the

Great Recession, leading to a nationwide undersupply of homes, especially at low and moderate income

price points.

1

These trends were exacerbated by the pandemic through materials and labor shortages

just as some places—Maine in particular—experienced a sudden influx of residents due to an increase in

remote workers seeking a higher quality of life and an increase in international immigration. What was

once primarily a problem for coastal cities has become a national one; almost every county in America

now has significant rates of renter cost burden, among other housing challenges (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Percentage of Cost Burdened Renters by County

Source: American Community Survey 5-Year 2021

While Maine has historically had a relatively affordable homeownership market, this changed in the years

leading up to the pandemic and has worsened since 2020.

2

Maine is also faced with an aging housing

stock, leading more of the state’s existing homes to sit vacant in need of reinvestment. These trends have

led to a range of housing challenges for Mainers, including reduced housing quality, limited options to

age in place, increased homelessness, and rising housing costs. All these issues are important to study

further. However, at the most basic level, aligning housing production with population and economic

growth is the foundation of a healthy housing market that offers quality homes at a price affordable to

1

Betancourt, Gardner and Palim. (2022). Housing Insights: The U.S. Housing Shortage from a Local Perspective.

Fannie Mae. https://www.fanniemae.com/media/45106/display

2

MaineHousing Affordability Index. (2023). MaineHousing. https://mainehousing.org/data-research/housing-

data/housing-affordability-indexes

> 45.8%

36.2%

< 27.0%

4

residents. The first step is to understand how many homes are needed to support broad

affordability and availability, which lays the foundation to adopt policies to create those homes.

Addressing housing supply challenges in Maine will require a comprehensive approach that considers

both the local regulatory changes needed to increase housing supply through new construction and the

funding needed to reinvest in Maine’s aging homes and create new homes that are affordable to those

with lower incomes, including seniors on fixed incomes, households waiting for federal work

authorization, and others. Further, strategies to overcome other barriers, such as the capacity of the

development and construction industry in Maine and environmental challenges, will all be necessary as

part of a comprehensive approach to increase supply.

3

While this will require both local and state-wide

strategies, the historic hyper-local response to what is ultimately a regional problem has been one of the

primary barriers in Maine and nationwide to building enough homes.

In recognition of this, the State of Maine has taken the lead on a strategy to build new homes and

reinvest in existing homes state-wide through the passage of LD 2003 and over $280,000,000 in

affordable housing production funding since 2019. LD 2003 requires municipalities to permit a wider

range of housing types and commits State financial and technical assistance for municipalities to support

local and regional production targets, including through measuring regional housing production needs.

LD 2003 recognizes that a data-informed approach to measuring regional and statewide housing

production needs is key to a broader state-wide planning effort to increase housing production.

This Study is a key step in this process, and it aims to answer the question, how many homes are

needed in Maine now and in the future to support Mainers to have access to the homes they need,

in a location that promotes economic opportunity, and at a price that ensures a high quality of

life? This Study is focused on measuring that need in alignment with the State’s specific demographic and

economic conditions as well as goals to ensure that Maine can sustain and grow its economy over time.

This Study measures “homes” as housing units in any building type, including single family, attached

housing and multifamily housing. Building and reinvesting in a diverse range of housing types to meet

different household needs and price points will be crucial to meeting Maine’s housing supply needs.

This Study, conducted by HR&A Advisors, was overseen by a Steering Committee representing

MaineHousing, the Governor’s Office of Policy Innovation and the Future (GOPIF), and the Department of

Economic and Community Development (DECD), together the “Study Team”, which met regularly to

coordinate research planning, data collection, and priority areas of analysis.

The Study Team also solicited feedback from a Technical Working Group composed of representatives

from the Department of Labor (DOL), the Maine State Economist, the Greater Portland Council of

Governments, the Maine Association of Realtors, the Maine Municipal Association, and other experts.

Approach

Maine has a set of broad policy priorities that inform this Study’s approach to measuring how many

homes need to be built or reinvested in. The first is to have enough homes overall to accommodate

the existing demand for homes. When there is an insufficient supply of homes, competition for the

limited number of homes available drives up prices to levels that are unaffordable to many existing

3

Sturtevant and Curtis. (2023). Availability of Workforce Housing in Maine. University of Maine.

https://usm.maine.edu/shaw-innovation-fellows/wp-content/uploads/sites/406/2023/05/Workforce-Housing-in-

Maine_Sturtevant-Curtis_Shaw-Innovation-Fellowship-8-May-2023-1.pdf.

5

Mainers. A healthy housing market—one that has enough homes to accommodate existing demand

across income groups—has a portion of homes that are vacant and available at any given time

4

. These

available homes allow households to move about the state as they change jobs, move out of homes to

start their own family, or otherwise need to relocate because of changes in their life. Right now, there are

portions of the state where there are simply no homes available for a household to move into.

The second policy priority is to have enough homes affordable, available and in the right locations to

support the workforce necessary to sustain and grow Maine's economy. The State’s Economic

Development Strategy focuses on the need for a workforce to support Maine’s long-standing industries

and to foster growth and innovation in new areas. To achieve these goals, Maine’s economy requires

workers to fill open positions as an increasing number of Mainers reach retirement and room for new

workers to fill positions created as local businesses and the economy grow. Without enough homes for

workers filling open job positions, businesses will continue to struggle and at times fail—harming the

prosperity of all Mainers.

With these two goals in mind, this Study calculates both the number of additional homes needed

currently to remedy Historic Underproduction and, by 2030, the Future Need to meet these policy

priorities. In recognition of Maine’s regional economies, Historic Underproduction and Future Need are

calculated for three economic regions: the Coastal Region, comprising Cumberland, Hancock, Knox,

Lincoln, Sagadahoc, Waldo, and York Counties, the Northeastern Region, comprising Aroostook,

Penobscot, and Washington Counties; and the Central Western Region, comprising Androscoggin,

Franklin, Kennebec, Oxford, Piscataquis, and Somerset Counties.

Other studies have quantified the need for homes in Maine, particularly for affordable rental homes. For

example, the National Low Income Housing Coalition (NLIHC) has estimated a shortage of 22,300

affordable and available rental homes for households making at or below 50% of Area Median Income

(AMI) and mostly for extremely low income households. While the State of Maine Housing Production

Needs Study considers housing need at the lowest income levels, the primary focus is on measuring

overall production needs for both renters and homeowners across the income spectrum in Maine,

incorporating the demand for seasonal homes, the need for additional workers, and the recent influx of

higher income households to Maine, all of which significantly impact the availability and price of homes in

Maine. Different approaches can be used together to understand different elements of housing need in

the state.

This Study does not, however, detail the specific physical typologies of homes needed to support different

populations including the elderly, asylum-seekers and refugees, those experiencing homelessness, and

different household types more broadly. It is important for the State and municipalities to take into

account local population needs and make regulatory and funding decisions accordingly, including by

reducing regulatory barriers to building the types of homes that households need and securing funding

for homes that can support populations with the highest need. Local planning should consider how

different housing types, including single family, attached and multifamily rental and for-sale homes, can

support availability at the price points needed while also considering local context.

Ultimately, setting production targets is a process that will need to account for regional variation in

demographic trends, economic development needs, and existing constraints on housing development.

4

Vacant and available homes do not include vacant homes that are not currently available for full-time

residence, whether due to disrepair, seasonal use, foreclosure, or other factors.

6

This Study provides analysis to help guide that process (Figure 2). As local planning follows, local

adjustments to these targets should be balanced with the likely impact on the availability and affordability

of homes for existing Mainers and the economic health of the state. These production targets will also

need to be monitored over time as economic and demographic conditions change and as municipalities

take steps to meet these targets. For more information about the Study approach, see page 12.

Figure 2: Setting Housing Production & Reinvestment Targets

Key Findings

While trends vary across the state, homes are becoming less affordable and harder to find in

Maine. There are demand-side drivers, including sudden in-migration and declining labor force

participation amongst Maine’s aging population, and supply-side drivers, including low housing

production and an aging housing stock, that are broadly driving these trends.

Demand-Side Drivers

Recent demand-side drivers, including sudden in-migration during the height of the Covid-19 pandemic

and a declining labor force from aging households, are impacting the number of homes Maine needs.

Maine experienced increased in-migration from out of state in recent years, concentrated in York and

Cumberland Counties but distributed across the state. These in-migrants have higher incomes on average

than existing Mainers and are able to pay more for homes. Maine has also experienced a surge in

households seeking asylum, who generally have very low incomes in the short-term as they await federal

work authorization.

At the same time, Maine’s population is aging, resulting in a declining labor force. This impacts both the

kinds of homes needed to accommodate a retiring population and homes needed to enable employers to

attract more workers to the state to fill open job positions. Over the past decade, Mainers 55 and over

have grown as a share of the population, and labor force participation among this group has significantly

declined since 2017 as the group gets closer to retirement age. As a result, overall labor force

State of Maine Housing

Production Needs Study

7

participation has not recovered post-pandemic as older workers retire, even as labor force participation

amongst younger groups has remained steady.

In order to fill the job vacancies created by increased retirement, Maine will need to bring in

workers from out-of-state, who will in turn require additional homes to live in.

5

Maine currently

has a very high share of unfilled job positions, with many parts of the state having more vacancies than

available workers. Many of these jobs skew somewhat lower income, reflecting a growing mismatch

between what many new workers could afford and the price of Maine’s available homes.

Supply-Side Drivers

These demand-side drivers are exacerbated by supply-side challenges, namely Maine’s aging housing

stock and low housing production over the past decade.

As the housing stock ages, the share of homes that are unavailable to be occupied due to poor condition

has increased. As these homes deteriorate over time, the inventory of homes can gradually decline

through demolition. There is limited data to quantify the annual loss of homes through demolition or

disrepair, however, individual towns and localities may have the information or begin to gather the

information through demolition permits to track the loss of homes over time. Ultimately, this data will

need to inform local production and reinvestment targets.

Maine has also had low housing production relative to job growth across all regions, but particularly

in the Coastal Region, which is a key measure of housing supply issues. Both the Central Western and

Northeastern regions have seen total housing inventory decline slightly since 2016. The state has also

seen a decline in rental homes across all regions, which runs counter to the trend in almost every other

housing market in America and is likely exacerbating Maine’s workforce challenges, as workers in entry-

level and lower wage positions often require rental housing options.

Finally, the consistently high demand for seasonal homes means that Maine has historically

required a higher number of homes relative to the number of year-round residents and available

jobs than states with lower seasonal demand.

Availability and Affordability

As a result of low production, reduced rental housing and an aging housing stock, the availability of

homes is declining and prices are increasing, making it very difficult to access and afford homes and fill

job openings in some parts of the state. Not all vacant homes in a housing market are available, as some

vacant homes might be reserved as a seasonal home, in foreclosure, in disrepair or otherwise unavailable

to the market for occupancy. True “availability” of the housing stock is defined as the vacant units that are

ready and available for a household to move into. In a healthy housing market, typically about 5% of

homes are vacant and available for use at any given time—allowing for housing choice flexibility and

5

Maine’s 2020 – 2029 Economic Development Strategy also aims to increase the labor force participation rate

of groups with historically lower participation, such as women and people with disabilities. However, the plan

acknowledges that in order to support Maine’s economic growth, additional workers will also have to come

from out of state.

Maine Economic Development Strategy 2020-2029: A Focus on Talent and Innovation. (2019). Maine

Department of Economic and Community Development.

https://www.maine.gov/decd/sites/maine.gov.decd/files/inline-files/DECD_120919_sm.pdf

8

movement. Across Maine, the share of homes vacant and available has fallen to an average of 2.3%

statewide.

Homeownership in Maine is becoming increasingly unaffordable. Under a standard definition set by

the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), homes are considered affordable if the

rent or cost of ownership

6

is less than 30% of household income. Until recently, the cost of purchasing a

home in Maine was such that a household earning the median income could afford the mortgage on the

median home value. In recent years, however, the demand- and supply-side drivers described above, in

addition to macroeconomic trends such as rising interest rates, have caused a significant divergence

between the income needed to purchase a home in Maine and the actual median income of Mainers;

households now need to make over $100,000 annually to afford the median home price As a result,

buying a home in Maine now is not affordable for the majority of Mainers.

Renters in Maine are also facing affordability and availability challenges. Maine has seen a decline in

renter-occupied units across the state since 2016, and the majority of renter households below 60% of

Area Median Income (AMI)

7

in Maine were cost burdened (paying over 30% of household income in rent)

in 2021, with the highest rates of cost burden in the Coastal Region. Although renter cost burden rates

remained relatively consistent from 2016-2021 (the most recently available data), rents and homes prices

increased significantly in 2022 and 2023 and exceeded wage increases, which has likely increased cost

burden rates since 2021.

Measuring Housing Need

To address these needs and meet the State’s policy priorities, Maine needs approximately 38,500

homes to remedy historic underproduction and will need an additional 37,900 to 45,800 homes to

meet expected population growth and household change by 2030 (Table 1). Maine can meet this goal

both through the production of new homes and reinvestment in existing homes that are vacant or

unavailable due to disrepair or foreclosure.

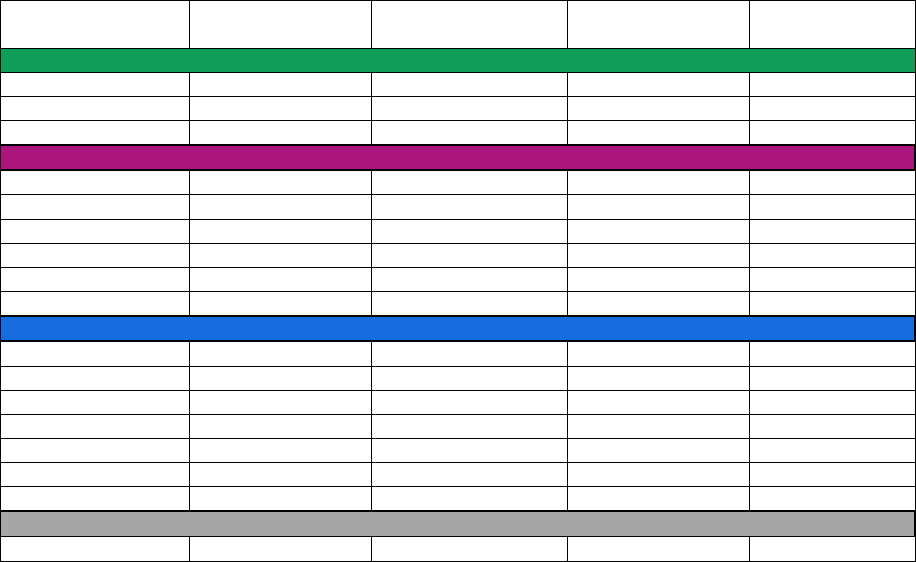

Table 1: Historic Underproduction and Future Need by Region

Region

Historic

Underproduction

Future Need

(2021 – 2030)

Total

Coastal 21,200 24,200 – 28,000 45,400 – 49,200

Central Western

13,000 9,700 - 11,700 22,700 – 24,700

Northeastern 4,300 4,000 - 6,100 8,300 – 10,400

Maine 38,500 37,900 - 45,800 76,400 – 84,300

Historic Underproduction: The Study Team defines historic underproduction as the deficit of available

homes for the existing population (the availability deficit) plus the deficit of homes for workers needed to

6

Includes mortgage, property taxes, and insurance.

7

See Appendix Page 5 for explanation of Area Median Income calculations.

9

increase the workforce to support Maine’s existing economy (the jobs : homes deficit)

8

. For more

information about how the Study Team measured historic underproduction in Maine, see page 40.

Future Need: The Study Team defines future need as the number of homes needed to support Maine’s

projected population and household change by 2030, while accounting for Maine’s high demand for

seasonal homes. For more information about how the Study Team measured future need in Maine, see

page 52.

To put this need in context, Maine’s total housing inventory in 2021 was about 737,800 homes. Increasing

the number of homes to meet historic underproduction alone (38,500 additional homes) would constitute

about a 5% increase in total homes across the state. To meet both current and future need by 2030,

Maine would need to add 8,500 to 9,300 homes each year (Table 2). Currently, about 4,800 homes are

permitted per year in Maine, and meeting this annual need would require a 77% to 94% increase in the

number of permits (with geographic variation). It is important to note that annual building permits are not

an exact measure of housing production, as not all permitted homes are built. The necessary increase in

housing production may be larger than current permitting suggests and will vary based on the annual

loss of homes in different regions.

Table 2: Annualized Production Needs Compared to Annual Building Permits by Region

Total Annual

Production

Need

5-year

average (2016

- 2021)

% Change in

Permits

Net Change in

permits

Coastal 5,100 – 5,500 3,400 50% - 62%

1,700 – 2,100

Central Western 2,500 – 2,700 1,000 150% - 170%

1,500 – 1,700

Northeastern 900 – 1,100 400 128% - 175% 510 - 700

Maine 8,500 – 9,300 4,800 77% - 94% 3,700 – 4,500

The number of additional homes needed varies across Maine’s regions. Much of it is concentrated in the

Coastal and Central Western Regions, which together need 34,200 homes to make up for historic

underproduction, and another up to 39,700 homes to meet future need. The Northeastern Region, by

contrast, needs about 4,300 additional homes to make up for historic underproduction and meet the

economic needs of the region and another 4,000 to 6,100 homes to meet future need by 2030.

Even in places where overall population is aging and declining, there is still need for housing production

and reinvestment; in fact, household formation can increase in these circumstances (children of an aging

population move into their own homes and some existing households split up). For example, while

Aroostook, Piscataquis and Somerset Counties are all projected to see a modest total population decline

by 2030, all of those counties will still see a net gain in households in that time period as well as a housing

stock that continues to age, requiring additional homes and reinvestment. Further, as these regions face

a declining workforce, new homes at affordable price points will be essential to attracting workers to the

region and ensuring that existing younger households can stay.

8

The “availability deficit” measures the additional homes needed to create a healthy level of availability in the

housing market, with “true availability” representing homes that are vacant and available to live in (defined as

For Sale and For Rent in the American Community Survey).

10

Income Distribution

In addition to the number of homes that Maine needs to sustain and grow its economy, it is important to

measure the price of homes needed to ensure that households hoping to work or age in place in Maine

can afford them. The Study Team created a sample income distribution by allocating the availability

deficit based on the income distribution of existing households (Table 3) and the jobs : homes deficit on

the expected household income distribution of wages from open job listings (Table 4).

Table 3: Allocation of Availability Deficit Based on Existing Household Income Distribution

9

Household Income Coastal Central Western Northeastern

Regional Totals 9,400 4,900 2,300

Less than 20K 1,100 780 420

20K - 35K 1,000 760 380

35K - 50K 1,000 730 320

50K - 75K 1,700 880 410

75K- 100K 1,400 650 290

100K - 150K 1,700 690 290

150K+ 1,500 410 190

Table 4: Allocation of Jobs : Homes Deficit Based on Estimated Household Wages of Open Job

Listings

10

Household Income Coastal Central Western Northeastern

Regional Totals 11,900 8,100 2,000

Less than 20K 70 50 10

20K - 35K 660 360 170

35K - 50K 1,230 640 210

50K - 75K 2,000 1,400 410

75K- 100K 2,300 1,600 380

100K - 150K 3,200 2,300 470

150K+ 2,500 1,700 350

9

Income Distributions are allocated based on regional numbers and rounded to the tens for counts in the

hundreds, and hundreds for counts over a thousand. Due to rounding, numbers may not sum exactly to

regional or state numbers.

11

It is important to note that low- and moderate-income households are more constrained in their choices

and more likely to pay more than they can afford for a home. Because of that, policy makers should

emphasize strategies to increase affordable housing production for low- and moderate-income

households in addition to strategies to increase the supply of homes more broadly. At the local level, this

may include weighting the income distribution of needed homes more heavily towards low- and very low-

income populations to account for this need.

Geographic Distribution

Across regions, individual jurisdictions are contributing more or less to housing demand based on

job growth, demographic and migration trends, and other factors, including the existing inventory of

available housing and the share of seasonal homes.

To measure local contributions to housing demand, the Study Team weighted the allocation of regional

need to the county level by both population share and job share of each county. Weighting allocation by

population and jobs helps ensure that housing to address the State’s historic underproduction is being

added in places where jobs are, both to support households in living close to where they work and also to

ensure that towns and cities that are growing economically are also accommodating the population

needed to support that growth. This avoids issues of decreasing affordability when housing is not

provided where job growth exists, and unnecessary development in areas where there may not be as

significant job or population growth.

There are many alternative ways to allocate housing to more granular geographies across Maine, many of

which would incorporate unique criteria specific to certain areas of the State.

Setting Production Targets

Meeting this housing need will require Maine to set housing production and reinvestment targets that

address both historic underproduction and disinvestment and account for future need. The next step in

the process will be to set housing production and reinvestment targets at the local level and to consider

the different housing typologies that can support housing production across the income spectrum. To

move from the regional level to the local level will involve consideration of local obstacles such as

available infrastructure, development capacity and other factors. It will also involve dialogue among

communities about where and how to accommodate growth and target reinvestment within the region.

Ultimately, creating enough homes in Maine is foundational to the wellbeing of all Mainers and can only

be achieved if the State and federal government, municipalities and the private sector work together on

an ongoing basis. This will require evaluating important metrics, such as availability rate, housing

production, cost burden, job availability, housing loss and others over time and adjusting housing

production and reinvestment targets to adapt to changing conditions.

In order for stakeholders to monitor these changing conditions and track progress towards local housing

production targets, the State will be providing an online data dashboard of baseline housing conditions at

the state, county, and municipal level that will be updated on a periodic basis. Moving forward, improved

collection of both building permitting and demolition data, as well as continuous tracking of vacancy

trends, will also be critical for monitoring new development. For more information on evaluation and

implementation, see page 58.

12

Study Approach

Introduction

There are many different policy makers, planners, organizations, and researchers who are already

working to understand housing needs in Maine, deliver programs and services, and plan for current and

future housing needs. This Study involved extensive engagement with state and regional experts and

stakeholders to inform its approach and methodologies.

This Study, conducted by HR&A Advisors, was overseen by a Steering Committee representing

MaineHousing, the Governor’s Office of Policy Innovation and the Future (GOPIF), and the Department of

Economic and Community Development (DECD), together the “Study Team”, which met regularly to

coordinate research planning, data collection, and priority areas of analysis.

The Study Team also solicited feedback from a Technical Working Group composed of representatives

from the Department of Labor (DOL), the Maine State Economist, the Greater Portland Council of

Governments, the Maine Association of Realtors, the Maine Municipal Association, and other technical

experts. Members of the Working Group provided ongoing input on data sources, analytical

approaches—including consistency with existing methodologies used by State agencies—preliminary

findings, and methodology development for measuring housing production and reinvestment needs.

In addition, the Study Team conducted a series of interviews regarding the housing needs of special

populations and the role of housing in supporting economic development across the state with

organizations including:

• Maine Immigrants’ Rights Coalition

• Jewish Community Alliance of Southern Maine

• Catholic Charities Maine

• Maine Immigrant and Refugee Services

• Island Institute

• Island Housing Trust

• Bath Housing

• WishRock Housing Group

Interviewees described a broad range of opportunities and challenges in Maine’s housing market.

Emergent themes included the need for housing to support Maine’s aging population while welcoming

new households to help support Maine’s economy; concerns about the impact of Maine’s seasonal

housing and short-term rentals on the available year-round stock; the challenges of providing homes for

the growing number of asylum seeker and refugee populations, and the difficulties faced by employers in

filling open job positions without available workforce housing.

Crucially, these discussions highlighted key State economic development goals that informed the Study

Team’s methodology to measure housing production and reinvestment needs—namely, to encourage

and enable communities to plan for housing to support a high quality of life for all Mainers while

also supporting economic stability and growth in the state.

13

Background Research and Existing Studies

The Study Team conducted a review of existing studies and plans to understand previous research on

housing challenges and opportunities in Maine. The National Low Income Housing Coalition (NLIHC) has

estimated a shortage of over 22,000 rental homes, however this shortage is specifically for low-income

renters, suggesting the overall number for all income groups is much higher.

A recent study by researchers at the University of Southern Maine found that Maine is short 20,000 –

25,000 homes for existing extremely low-income Maine residents, as well as 10,000 – 20,000 homes that

are necessary to attract enough workers to fill open job positions.

11

In total, the study estimates Maine

has a shortage of 30,000 – 40,000 new homes currently.

When considering broader housing needs beyond housing supply, housing studies at the municipal

level

12

echo common themes, including:

• Lack of homes necessary to accommodate an aging population while creating homeownership

opportunities for younger households.

• Aging housing stock in need of repair and reinvestment.

• Lack of affordable housing for low and middle-income households, exacerbated by undersupply

of homes, and (anecdotally) increased housing demand from out-of-state in-movers.

• Difficulty filling open job positions due to limited housing availability.

• Housing located far from jobs and transit, resulting in long commutes and high household travel

costs.

• Concerns about a rise in seasonal housing and short-term rentals putting pressure on the

housing stock within certain tourism-heavy communities.

This Study intersects with these issues in certain areas, including by measuring the number of homes

needed to support healthy availability in the housing market overall and a healthy job market. This Study

builds on previous work by considering the regional need for homes across the income spectrum as well

as the need to meet demand for seasonal homes and homes for recent higher income in-migrants, both

of which significantly impact the availability and price point of homes for low and moderate-income

residents. This Study does not, however, detail the specific physical typologies of homes needed to

support different populations including the elderly, asylum-seekers and refugees, those experiencing

homelessness, and different household types more broadly. It is important for the State and

municipalities to take into account local population needs and make regulatory and funding decisions

accordingly, including by reducing regulatory barriers to building the types of homes that households

11

Sturtevant and Curtis. (2023). Availability of Workforce Housing in Maine. University of Maine.

https://usm.maine.edu/shaw-innovation-fellows/wp-content/uploads/sites/406/2023/05/Workforce-Housing-in-

Maine_Sturtevant-Curtis_Shaw-Innovation-Fellowship-8-May-2023-1.pdf.

12

Crane Associates and EPR. (2022). City of South Portland Housing Needs Assessment and Strategy.

https://go.boarddocs.com/me/sport/Board.nsf/files/CF9GZQ46438A/$file/Att.%201%20-

%20Final%20Housing%20Report_05.20.2022.pdf.

Edwards, Keith. (2021). Augusta housing study shows changes needed to address lack of affordable housing.

Kennebec Journal. https://www.centralmaine.com/2021/02/15/augusta-housing-study-shows-changes-needed-

to-address-lack-of-affordable-housing/.

Camoin Associates and The Musson Group. (2018). Housing Needs Analysis and Assessment: Mount Desert

Island, ME. Island Housing Trust.

https://static1.squarespace.com/static/569fba9076d99cc6c04e5005/t/5cc204b16f3d150001a80f8a/1556219104

894/IHT-Housing-Study-2018.pdf.

14

need and securing funding for homes that can support populations with the highest need. Local planning

and studies should consider how different housing types, including single family, attached and

multifamily rental and for-sale homes can support availability at the price points needed while also

considering local context.

The Study Team reviewed housing production studies across the country to compare how different

methodologies can be used to accommodate important local economic and housing market trends in

Maine. In California, regional goals incorporate population, vacancy rates, overcrowding, cost burden, and

replacement rates, and are allocated to the municipal level by regional councils of governments (COGs).

Similarly, Oregon sets regional targets incorporating projected need, historic underproduction, and

homes for people experiencing homelessness based on population and vacancy rates. Massachusetts,

rather than using regional metrics, sets a goal of 10% affordable housing for each municipality. For more

information on national production goal methodologies, see Appendix Page 3.

Determining Geographic Boundaries

Given the alignment between State economic development goals and housing needs, the Study Team

strove to align the geographic boundaries of this study with Maine’s economic geographies. Maine’s

housing and labor markets are unusually regional— Maine has the longest median 1-way commute in

miles in the United States, with the median commuter traveling close to 10 miles each way.

13

As a result,

this Study uses regional geographies when measuring housing need in Maine relative to jobs but also

points to the need for new homes that can support Mainers to live closer to their jobs.

In recognition of this, the Study Team selected the Department of Labor’s three Workforce Investment

Regions as the highest geographic level for the Study (Figure 3).

14

Figure 3: Maine Workforce Investment Regions and Counties

13

Commutes Across America: Where Are the Longest Trips to Work? (2018). Streetlight Data.

https://www.streetlightdata.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Commutes-Across-America_180201.pdf

14

In order to align the Workforce Investment Region boundaries with Census data used to study current

housing needs in Maine, the Study Team reallocated Hancock and Piscataquis Counties from the Northeastern

Region to the Coastal and Central Western Regions, respectively.

15

The Coastal Region, consisting of Cumberland, Hancock, Knox, Lincoln, Sagadahoc, Waldo, and York

Counties and encompassing the greater Portland area, is the most heavily populated of the three regions

and is currently home to 55% of the state’s jobs in 2023

15

. The Central Western region consists of

Androscoggin, Franklin, Kennebec, Oxford, Piscataquis, and Somerset Counties, and is home to the cities

of Augusta, Lewiston and Auburn. The Northeastern region is the smallest and most rural of the three

regions, consisting of Aroostook, Penobscot, and Washington Counties. For a detailed list of towns,

counties and cities in each region, see Appendix Page 1.

15

Defined as total employment (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2023) added to total open job listings (Job Openings

and Labor Turnover Survey, 2023).

16

What is happening in Maine’s housing market now?

Overview

Before measuring housing production needs, the Study Team explored existing conditions and trends in

Maine’s housing market to understand key demographic, economic and housing inventory dynamics that

influence housing need. These conditions and trends, summarized below, highlight Maine’s unique

economic, demographic and housing market conditions, all of which inform both the need for more

homes in Maine and the opportunity for homes to better support economic development in the state.

Adequate housing supply to meet demand is the foundation of affordability in any housing market,

including Maine’s diverse regional housing markets (Figure 4). As such, it is important to understand both

housing supply and housing demand trends to ensure that enough homes are created and preserved in

Maine that are the type and price that households need. This study explores both demand-side drivers of

housing need (demographic and economic change) and supply-side drivers (housing age, type, prices and

production) to arrive at housing production and reinvestment needs. While trends vary across the state,

recent demand-side trends, including sudden in-migration and declining labor force participation, are

exacerbated by Maine’s aging housing stock and low overall housing production over the past decade. As

a result, the availability of homes is declining and prices are increasing, making it very difficult to access

and afford homes in some parts of the state.

The following sections explore these trends in greater detail and illustrate how these trends impact

Maine’s housing supply needs.

Figure 4: Supply and Demand of Homes

In a healthy housing market, housing demand, the number of households by income level, size, and type, is

equivalent to housing supply, the number of suitable homes for households, with some additional availability

(vacancy). When housing demand exceeds housing supply, more homes are needed to ensure availability and

affordability.

Demand-Side Drivers of Housing Need

Overall population and population growth determines how many people presently need homes and

how many people will need homes in the future. The type and size of households, in combination with

population growth, determines how many homes and what types of homes are needed to accommodate

the population and their household needs. Finally, household income determines how much money

households can put towards housing costs each month, impacting the needed price point of homes.

Each of these local factors is influenced by both regional and national trends, and changes in any of these

elements will impact the amount, type and price point of homes needed in a housing market. Maine has

experienced recent demand-side shocks, including the following:

17

• Sudden in-migration during and after the Covid-19 pandemic, generally from higher income

households (in-migrants had an average household income of $88,000 compared to $78,000 of

existing residents.

16

• A surge in asylum-seekers, who generally have very low incomes in the short term.

• A declining labor force as the State’s population ages, impacting both the kinds of homes

needed to accommodate the population and employers’ ability to fill open job positions.

Population Change

Historically, Maine has experienced modest overall population growth, with a 10.5% increase in

population from 1990 to 2021. This growth has lagged other northeastern states; New Hampshire grew

by 23.7% and Vermont by 14% in this time period (Figure 5).

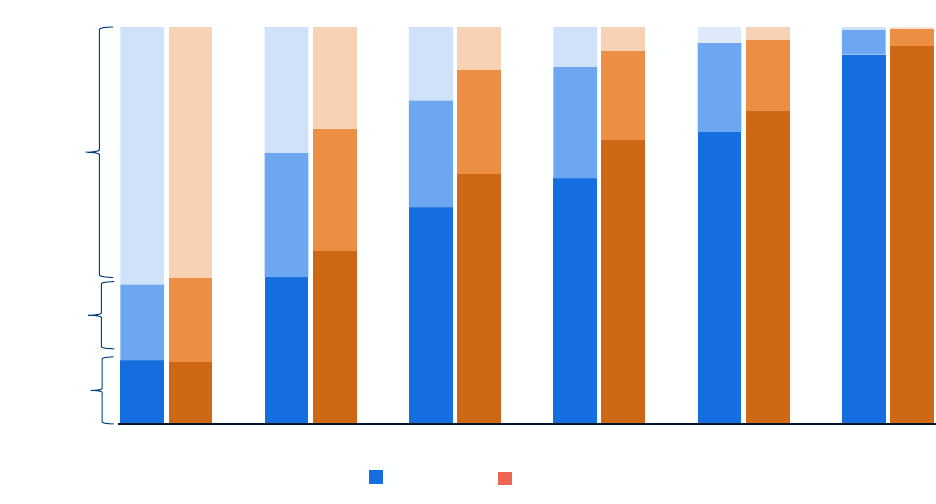

Figure 5: Comparative State Population Growth, 1990 – 2021

Source: Decennial Census 1990 – 2021

While the State has grown overall, population change has varied across the state. The Coastal Region,

where most of the state’s population is concentrated, has grown by 22.2% since 1990. Much of the

Coastal Region’s growth has been driven by Cumberland and York Counties, which each grew by nearly

7% from 2010 to 2021 alone. By contrast, the Central Western Region only grew by 4.6% and the

Northeastern Region declined by -6.8% in that time period (Figure 6).

16

Maine’s average household income of $78,000 is higher than the median household income of $63,200, which is

used as a reference point throughout the rest of this report.

1,230,000

1,270,000

1,330,000

1,360,000

1,110,000

1,235,786

1,316,470

1,370,000

560,000

608,827

625,741

640,000

0.0M

0.2M

0.4M

0.6M

0.8M

1.0M

1.2M

1.4M

1.6M

1990 2000 2010 2021

Maine

New Hampshire

Vermont

18

Figure 6: Population Growth by Region, 1990 – 2021

Source: Decennial Census 1990 – 2021

Income Distribution

Maine’s households are somewhat lower income than its neighboring states, with a median household

income of $63,200 relative to New Hampshire’s median income of $83,400 and Vermont’s median income

of $69,000. 58% of households earn less than $75,000, slightly more than the 54% of households earning

under $75,000 in the United States as a whole.

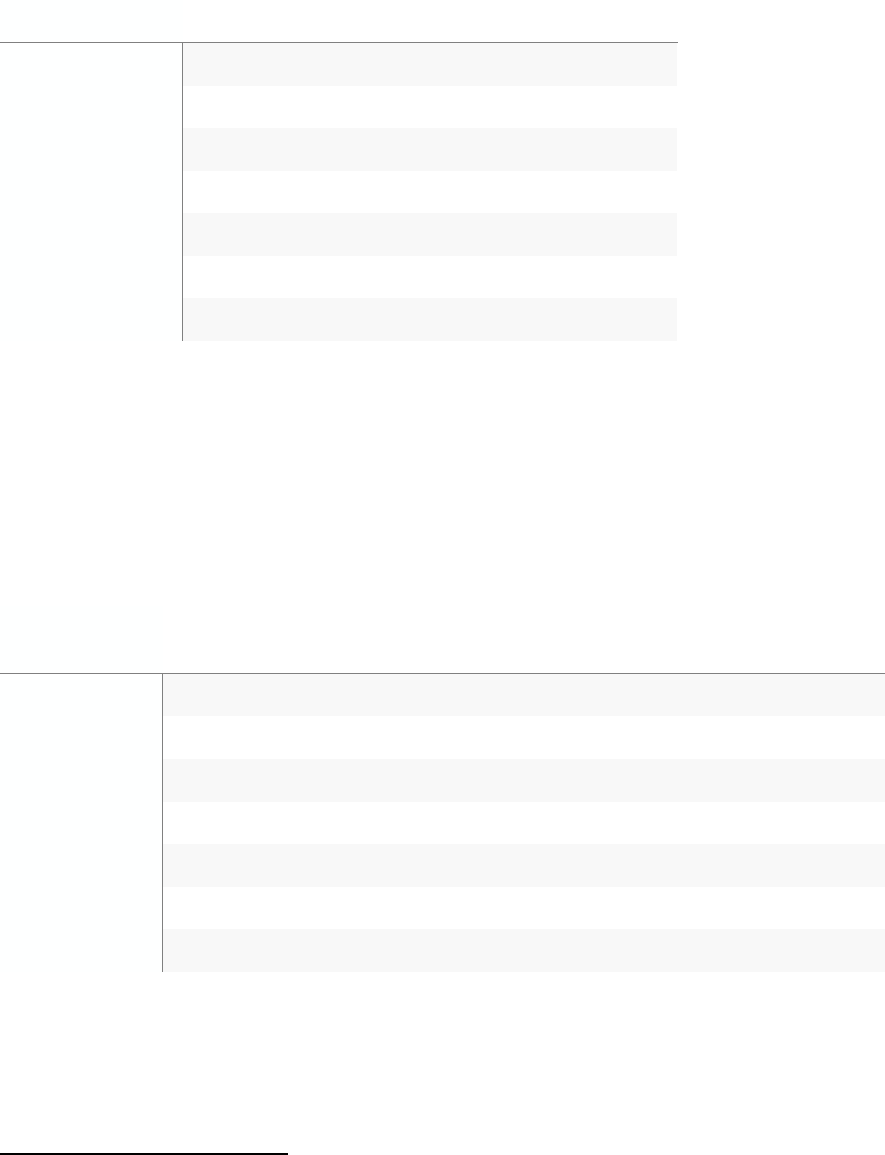

Income distribution varies by region, however, with higher incomes in the Coastal Region in particular.

16% of households in the Coastal Region earn more than $150,000, relative to 8% in the Central Western

and Northeastern Region. The Northeastern Region has the lowest incomes, with almost 50% of

households earning less than $50,000 annually (Figure 7).

269,000

253,000

259,000

250,000

371,000

373,000

388,000 388,000

588,000

649,000

681,000

718,000

0

100,000

200,000

300,000

400,000

500,000

600,000

700,000

800,000

1990 2000 2010 2021

Coastal

Central Western

Northeastern

19

Figure 7: Income Distribution by Region, 2021

Source: American Community Survey 5-Year 2021

Recent In-Migration

Recently, significant in-migration has quickly increased the demand for homes in Maine. This is

particularly concentrated in York and Cumberland Counties, which respectively received 1,200 and 2,000

in-migrant households in 2020 alone (a little under 2% of their baseline total households). On average, the

recent in-migrant households have somewhat higher incomes than existing households, with an average

income of $88,000 compared to a median income of $63,200 for existing households

17

. This has

increased demand for housing across the income spectrum, but particularly at higher price points (Figure

8).

17

IRS data only provides average income of in-migrants, rather than median income, preventing direct

comparison to Maine’s median income. The average income of Maine’s existing residents is $78,000.

11%

16%

18%

11%

15%

17%

11%

15%

14%

18%

18%

18%

15%

13%

13%

18%

14%

13%

16%

8%

8%

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

Coastal Central Western Northeastern

<20K 20K - 35K 35K - 50K 50K - 75K 75K-100K 100K-150K 150K+

20

Figure 8: In-Migration Versus Baseline Population by County, 2020

Source: Internal Revenue Service 2021, American Community Survey 5-Year 2021

Bubble Size = Baseline Population

Demand at the lowest income levels is also being impacted by a recent uptick in households seeking

asylum, who generally need short-term housing support. Since 2018, the number of individual notice-to-

appear cases filed annually in Maine (a proxy for the total number of asylum seekers arriving in Maine)

has risen from under 400 to nearly 3,400 as of August 2023 (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Total Individual Notice-To-Appear Cases Filed, 2001 - 2023

Source: TRAC New Proceedings Filed in Immigration Court; Notice to Appear Deportation Cases 2001 – 2023

0.0%

0.5%

1.0%

1.5%

2.0%

2.5%

0 500 1,000 1,500 2,000 2,500

Net Out of State In

-Migrant Households as Share

of Baseline Total Households

Total Out of State Net In-Migrant Households

York

Cumberland

Penobscot

Kennebec

143

86

97

161

159

173

117

87

231

1,205

749

561

2,010

3,356

0

500

1,000

1,500

2,000

2,500

3,000

3,500

4,000

2001 2006 2011 2016 2021

$88K

Average income

of in-migrants

$78K

Average income of

existing households

21

Facing short-term restrictions on employment by the Federal Government, households seeking asylum

often rely on Maine’s General Assistance Program to find housing in the private market or utilize

subsidized housing, which is difficult and costly to build quickly. Locations where housing is more

affordable may be far from public transportation, a particular barrier for households without access to a

car, and far from the support of existing refugee and asylum seeker communities. In addition, a high

proportion of larger households arriving—data from the Office of Maine Refugee Services (OMRS)

suggests that asylum seekers have an average household size of 4 people compared to 2.6 in the state on

average—can make it difficult to find affordable homes that allow families to stay together.

Labor Force Participation

Maine has an aging population, which also means an aging labor force. Since 2011, Mainers 65 and over

have grown from 16% to 21% of the population. This is significantly higher than in the United States

overall (16%) and higher than all neighboring states, including Vermont (20%), New Hampshire (18%) and

Massachusetts (17%). Until recently, Maine had significantly higher labor force participation amongst 55 –

64 year-olds relative to the United States as a whole, peaking at 73% in 2017. The decline of this labor

force participation rate, which accelerated during the Covid-19 pandemic and does not track with national

trends for this age group, is already impacting the health of Maine’s economy as businesses find it

increasingly challenging to fill open job positions (Figure 10).

Figure 10: Ages 55 - 64 Labor Force Participation, Maine vs. United States, 2003 - 2022

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics Local Area Unemployment Statistics 2003 – 2022

The decline in labor force participation amongst older Mainers suggests pandemic-driven early

retirements, while labor force participation amongst younger groups has remained relatively consistent

(Figure 11). As a result, Maine’s overall labor force participation has not recovered to pre-pandemic levels,

in contrast with the national labor force participation rate, which has largely recovered.

62%

63%

64%

65%

64% 64% 64%

65% 65% 65% 65%

63%

68%

65%

66%

64%

69%

68%

73%

68%

67%

63%

40%

45%

50%

55%

60%

65%

70%

75%

80%

85%

90%

2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013 2015 2017 2019 2021

Maine

United States

22

Figure 11: Maine Labor Force Participation by Age, 2003 – 2022

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics Local Area Unemployment Statistics 2003 – 2022

Note: No data in 2019 for All Ages and 65 Years and Over.

This decline in labor force participation for older adults, as well as Maine’s aging population more

broadly, has contributed to a need for additional households to support Maine’s existing economy.

As of May 2023, Maine had 46,000 unfilled job positions, just over half of which are estimated to be

located in the Coastal region

18

.

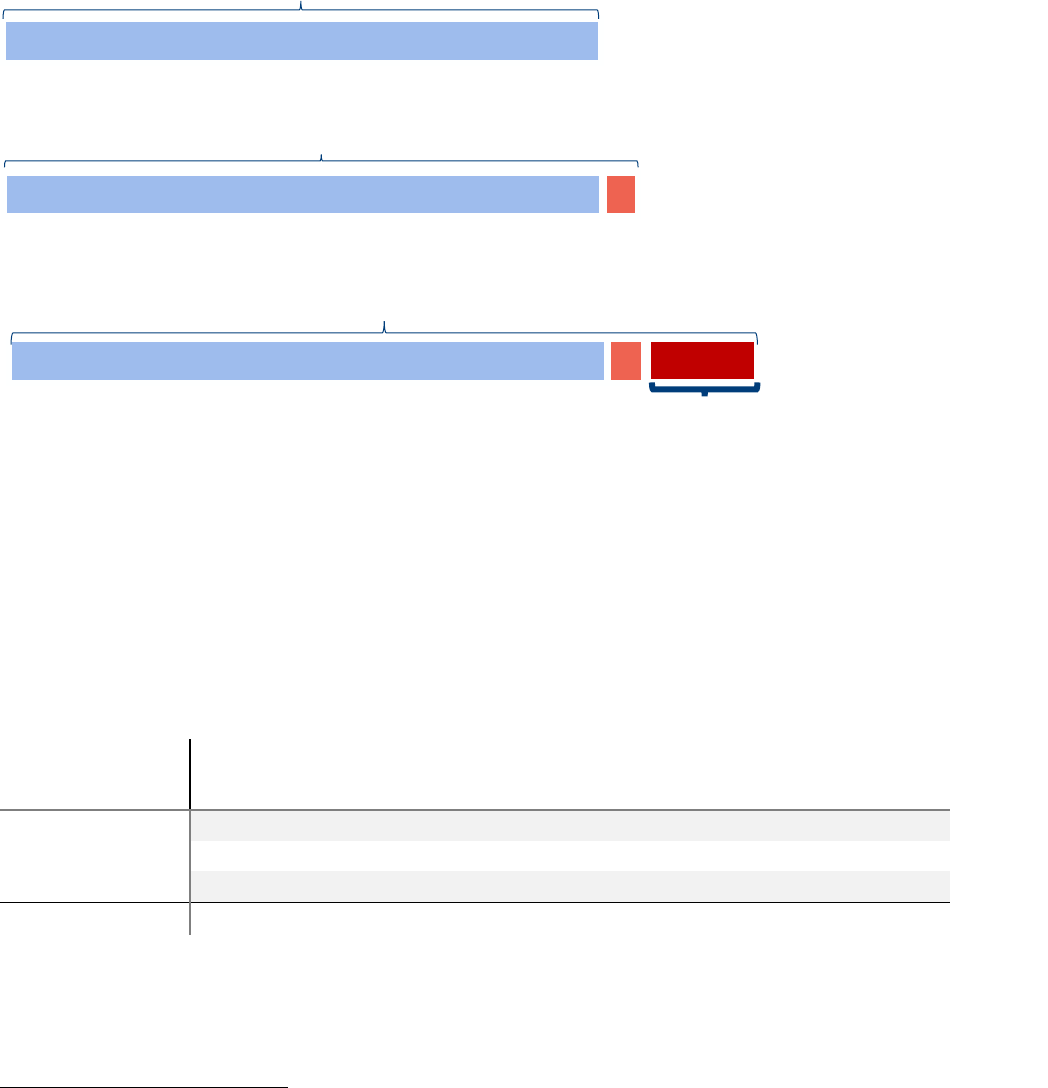

Unfilled job listings skew toward lower paying positions. In the Northeastern and Coastal regions, over

50% of job listings pay less than $50,000 annually (Figure 12). This suggests that in-migrants, who are

generally higher income, are not necessarily filling these positions at high rates as they move to the state.

It also creates a large and growing mismatch between the home price that workers can afford and the

price of available homes.

18

HR&A analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey, 2023.

83%

81%

85%

82%

81%

63%

73%

63%

13%

20%

19%

67%

65%

58%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

2003 2009 2015 2021

20 - 34 Years 35 - 54 Years 55 - 64 Years 65 Years and Over All Ages

23

Figure 12: Job Listing Wages by Region, 2022 - 2023

Source: Lightcast 2023

There has been a dramatic uptick in the “Unclassified” category, which includes new employer accounts

from out of state that have not yet been processed by the State Department of Labor in their Quarterly

Census of Employment and Wages. This may be a reference to the increase in remote workers, but

further study is needed to understand the increase in remote work in Maine and the impact on wages.

The result of these economic and demographic trends is that the ability to pay for higher-priced

homes is increasing for some segments of the population while others struggle to afford costs in

an increasingly constrained market. Existing residents who are not actively part of the workforce or

who have low or moderate wages (particularly those earning less than 80% of AMI) are competing in the

same housing market. The Coastal Region is particularly impacted by this increased demand by higher

wage households, but this region has also seen an influx of households seeking asylum who are in need

of much lower cost housing options. Without adequate increased housing supply to meet this rising

demand at different price points, Mainers are seeing reduced availability and affordability across all

regions, as described in further detail below.

Supply-Side Drivers of Housing Need

Housing supply is influenced by the total number of homes in a market, the types of homes (may

include multifamily at varying densities, single-family homes, mobile homes, or other non-traditional

home types (boats, etc.), the tenure of homes available (homes can be either owned or rented), the

price point (can be influenced by available subsidy programs, overall supply of homes and by what

tenure or type, and be impacted by demand and the availability (whether the home is vacant and

available for a user to occupy by renting or purchasing).

Maine’s existing housing supply is composed primarily of single-family homes that are owned, which is

also the primary type of housing that has been added to the market. However, over the last decade,

Maine’s housing production has lagged job growth. Furthermore, the inventory of homes that

need reinvestment is increasing, which is reducing the overall availability of homes.

5%

18%

28%

19%

19%

9%

1%

5%

13%

20%

30%

24%

6%

1%

4%

28%

23%

29%

8%

4%

3%

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

30%

35%

<20K 20K - 35K 35K - 50K 50K - 75K 75K-100K 100K-150K 150K+

Coastal Central Western Northeastern

24

Tenure and Typology

Owner-occupied homes represented 73% of all Maine’s homes in 2021, a high share relative to the

housing stock of the United States as a whole, which was 65% owner-occupied in 2021. Of those owner-

occupied homes, close to 87% were single-family homes (on par with the United States owner-occupied

stock, which is 89% single-family) (Figure 13). Notably, mobile homes, an affordable homeownership

option, made up 9% of the owner-occupied stock.

There is greater diversity in Maine’s renter-occupied housing stock, with low-density 2-9 unit buildings

providing about 20% of the rental options in the state, and 10 – 49 unit buildings providing about 10% of

rental options. The rental stock has a high representation of single-family homes, however, with single-

family homes making up 61% of rental homes, close to twice the single-family share of the United States

rental stock (33%). This is likely due to the overall character of Maine’s housing inventory, local zoning

regulations and the rural nature of much of the state.

Figure 13: Occupied Units by Typology and Tenure in Maine, 2021

Source: American Community Survey 5-Year 2021

Subsidized Housing

Federal, State and local subsidy can be used to provide direct assistance to households or to reduce the

cost to build or operate homes. Although income eligibility for subsidized housing varies by program,

these subsidies are typically available to households making up to 80% of Area Median Income. The most

prominent funding source for affordable housing is the federal Low-Income Housing Tax Credit, provided

to developers of affordable rental housing

19

, which ultimately reduces the total rent that occupants pay to

better align with what they can afford. Public housing, another common type of affordable housing, is

typically owned and managed by the local housing authority. Housing vouchers, a form of direct subsidy to

tenants, provides rental assistance that allows households to rent on the private market at a price point they

can afford (or, in some cases, specific project-based units).

In 2021, Maine had approximately 28,000 subsidized rental homes with income restrictions ensuring

affordability to households making less than 60% of AMI. These homes make up 21% of the rental

19

The Low-Income Housing Tax Credit program gives State and local agencies an annual budget to issue tax

credits to support construction or preservation of affordable housing.

87%

61%

3%

18% 10% 4%

9%

3%4%

Owner-Occupied

Renter-Occupied

Single Family 2-9 Units 10-49 Units 50+ Units Mobile Home Other

25

housing stock, a substantial share (Figure 14). Maine has continued to add affordable housing: just over

7,500 of these subsidized, income-restricted units have been added since 2010 (Figure 15).

A further 71,850 units were affordable to households making less than 60% of AMI without rent

restrictions, often referred to as “Naturally Occurring Affordable Housing (NOAH).” These units made up

54% of Maine’s rental stock in 2021.

Figure 14: Rental Housing by Affordability and Rent Restricted Status, 2021

Source: American Community Survey 5-Year, Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS) 2021, National Housing

Preservation Database 2021

21%

54%

24%

Rent Restricted, Affordable at Less Than 60% AMI Unrestricted, Affordable at Less Than 60% AMI

Unrestricted, Affordable at 60 - 100% AMI Unrestricted, Affordable at Greater Than 100% AMI

26

Figure 15: Rent Restricted Units in Maine by Earliest Subsidy Date, 2021

Source: National Housing Preservation Database 2021

Housing Production

Overall housing production has lagged job growth over the past decade—particularly in the

Coastal region. All regions have gained significantly more jobs than housing units, with total housing

inventory remaining essentially constant since 2016, with a slight decline in the Northeastern Region

(Figure 16, Table 5). Job growth has been primarily concentrated in the Coastal Region, and while housing

inventory there has grown modestly, the region has seen only 21,300 homes built relative to an increase

of 39,334 jobs over the past decade (Table 5). The Northeastern region in particular has had modest job

growth. However both the Northeastern Region and Central Western regions have availability rates of

close to 2%, suggesting that limited housing supply may be impeding the ability of new workers to move

to these regions to fill open positions.

Figure 16: Total Housing Inventory by Region, 2010 - 2021

Source: American Community Survey 5-Year 2021

8,000

5,200

2,600

4,600

7,500

0

1,000

2,000

3,000

4,000

5,000

6,000

7,000

8,000

9,000

Pre-1980 1980 - 1989 1990 - 1999 2000 - 2009 Post-2010

367K

212K

135K

376K

214K

137K

389K

214K

135K

0K

50K

100K

150K

200K

250K

300K

350K

400K

450K

Coastal Central Western Northeastern

2010 2016 2021

27

Table 5: Net New Units versus Change in Employment and Job Listings

New / Lost Units

2010 -2021

New / Lost Jobs

(2010 - 2022)

Change in Job

Listings (2010 –

2022/23)

Availability Rate

Coastal +21,304 +39,334 +13,144 2.1%

Central Western +2,389 +5,791 +9,408 2.2%

Northeastern (181) +725 +2,583 3.0%

Source: American Community Survey 5-Year 2021, Bureau of Labor Statistics State Current Employment

Statistics 2010, 2023 allocated using QCEW, Lightcast job listings 2010 , 2023

Notably, the state has experienced an overall decline in rental homes, with the greatest gross and

percentage loss in the Coastal region of 3,000, or a 4% loss (Figure 17). This may be exacerbating labor

force challenges for low and moderate wage jobs, which typically do not pay enough for workers to afford

most homeownership options and thus rely heavily on rental housing.

Figure 17: Renter Occupied Units by Region, 2016 - 2021

Source: American Community Survey 5-Year 2021

Moderate and low-density rental homes (single-family and 2-9 unit homes) in particular have

declined in stock since 2016, with Maine seeing a loss of 4,800 single family homes (a 14% decline)

29,600

44,400

78,000

152,000

31,200

44,900

81,000

157,100

Northeastern

Central Western

Coastal

Maine

2016 2021

-1%

(500) Units

-5%

(1,600) Units

-4%

(3,000) Units

-3%

(5,100) Units

28

and 4,100 low-density (2-9 unit) homes (a 5% decline). These losses are concentrated among homes

affordable to households earning 60 – 80% of AMI, which since 2016 have declined by over 3,500 single-

family homes (a 33% decline) and almost 1,400 low-density homes (a 9% decline), although modest

growth in higher density rental housing for low- and moderate-income renter households may have

eased some cost pressures for renters.

Vacant Housing Stock

Facing limited housing production relative to demand, some of Maine’s growing housing demand

is being absorbed by vacant housing stock. All regions have seen a decrease in vacant for-rent and

vacant for-sale housing stock, meaning that there are increasingly limited available housing options for

both renters and homebuyers (Figure 18). This scarcity increases competition for available homes and

helps drive up prices. Simultaneously, Maine’s inventory of homes that are unavailable due to other

conditions including foreclosure, repairs and family reasons, has increased by nearly 5,000 statewide

since 2011, further reducing the available housing stock.

20

Figure 18: Vacant Housing in Maine, 2011 - 2021

Source: American Community Survey 5-Year, Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS) 2021

Much of this need for repair and reinvestment is likely driven by Maine’s aging housing stock. Maine’s

homes are older on average than the rest of the country, with homes built before 1960 making up around

35% of the housing stock in all regions, relative to 27% in the United States as a whole (Figure 19). This

aging is particularly acute in the Central Western and Northeastern regions, where close to 60% of homes

in 2021 were built before 1980.

20

American Community Survey detailed vacancy breakdowns, including the share of Other Vacant housing in

need of repair, are unavailable historically, limiting this study’s ability to directly assess changes in need for

repair over time.

12,900

2,200

9,500

2,000

210

22,800

8,600

2,000

5,000

2,700

220

27,700

0

5,000

10,000

15,000

20,000

25,000

30,000

For Rent Rented, Not

Occupied

For Sale Only Sold, Not

Occupied

For Migrant

Workers

Other Vacant

2011 2016 2021

• Foreclosure

• Personal/Reasons

• Legal Proceedings

• Preparing to rent/sell

• Held for storage

• Needs repairs

• Currently being repaired

• Extended absence

• Abandoned/possibly

condemned

29

Figure 19: Age of Housing Stock by Region, 2021

Source: American Community Survey 5-Year 2021

Both Maine’s aging stock and increasing share of homes unavailable due to foreclosure, repairs and other

reasons suggest that declining housing quality is a significant factor in Maine’s housing availability

challenges. However, data directly assessing housing quality in Maine is scarce, and further study will be

needed to more accurately measure the extent of repair and reinvestment needed in Maine’s housing

stock.

Seasonal Homes and Short-Term Rentals

Maine’s tourism and seasonal economy has also shaped its available housing supply. Maine has always

had a high share of seasonal homes, representing 16% of Maine’s total housing stock in 2021. The

proportion of seasonal homes statewide has remained generally level, with a slight decrease from

124,500 homes in 2016 to 120,600 homes in 2021 (Figure 20). 85% of seasonal homes were concentrated

in the Coastal and Central Western Regions, where seasonal housing makes up close to a fifth of the

housing stock (Figure 21). In the Coastal Region, the share of seasonal housing remained consistent from

2000 – 2021 (Figure 22).

The consistently high demand for seasonal homes means that Maine has historically required a

higher number of homes relative to the number of year-round residents and available jobs than

states with lower seasonal demand.

8%

6%

5%

5%

14%

14%

11%

12%

14%

13%

12%

12%

13%

15%

14%

13%

25%

19%

23%

23%

27%

34%

36%

35%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

United States Coastal Region Central Western Region Northeastern Region

Built 2010 Onwards Built 2000 to 2010 Built 1990 to 2000

Build 1980 to 1990 Built 1960 to 1980 Build 1960 or Earlier

30

Figure 20: Seasonal Homes Over Time by Region, 2000 - 2021

Source: Decennial Census 1990 – 2021

Figure 21: Seasonal Housing as Share of Total Homes by Region, 2021

Source: American Community Survey 5-Year 2021

52,800

33,300

15,400

61,200

36,700

16,400

64,700

40,900

18,900

64,100

38,700

17,800

-

10,000

20,000

30,000

40,000

50,000

60,000

70,000

Coastal Central Western Northeastern

2000 2010 2016 2021

17%

18%

13%

83%

82%

87%

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

Coastal Central Western Northeastern

64,100 Homes

17,800 Homes

38,700 Homes

31

Figure 22: Seasonal Housing As Share of Total Homes Over Time in the Coastal Region, 2021

Source: American Community Survey 5-Year 2000, 2010, 2016, 2021.

The rise of online short-term rental platforms has raised some concerns in Maine about the extent to

which available homes are being converted to short-term rentals. Using AirDNA, a platform tracking

Airbnb and Vrbo rentals across the state, the Study Team found that Maine had 23,859 short-term rental

properties with at least one reservation between April 2022 and 2023, largely concentrated in the Coastal

region (16,904), followed by the Central Western region (5,014) and Northeastern region (1,941), about

20% of seasonal homes overall.

21

While short-term rentals make up an increasing share of seasonal homes, they are not always directly

comparable to homes that might otherwise be available to year-round residents looking for housing

because of type, size, location and price point, or because the owners occupy them for part of the year.

Many of these properties would not viably serve as year-round housing at all— 9% of the AirDNA

inventory is hotels and hostels, B&Bs, and “unique” listings (e.g., tents, treehouses, caves, etc.) (Figure 23).

Of the total AirDNA inventory, the Study Team identified 57% percent that are directly relevant to the

supply of year-round homes—defined as an entire single family or multifamily unit, available more than 3

months out of the year.

21

Note that the count of overall seasonal homes will likely incorporate most full-time short-term rentals, and

may exclude short-term rentals that are used as a primary residence most of the year.

16.1%

16.5%

17.2%

16.5%

84%

84%

83%

83%

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

2000 2010 2016 2021

32

Figure 23: Short-Term Rentals by Typology, April 2022 - 2023

Source: AirDNA 2023. All properties with at least one reservation in the past year.

Further, not all short-term rentals would be available at a price point affordable to the median renter if

offered on the private market, whether due to size, location, or high-end design. Excluding luxury rentals

and rentals with more than 3 bedrooms from the data, the Study Team found that about 33% of the

short-term rental stock is reasonably comparable to naturally occurring affordable housing (NOAH) on

the market based on size and quality. In each region, the total number of current short-term rentals that

meet this criteria range from just 0.6% to 1.4% of the total housing supply (Figure 24).

Figure 24: Short-Term Rental Inventory by Region, 2021

Source: AirDNA 2021

71%

20%

4%

3%

House/villa Apt/Condo/Loft Unique B&B Hotel/Hostel

1,773

856

7,644

1,569

3,940

1,672

825

5,320

0

2,000

4,000

6,000

8,000

10,000

12,000

14,000

16,000

18,000

Central Western Northeastern Coastal

Hotel rooms and other non-viable homes Luxury and >3 Bedroom Rental

Comparable to NOAH Homes

1.37% of Regional

Housing Supply

0.61% of Regional

Housing Supply

0.78% of Regional

Housing Supply

33

Concentration of short-term rentals is notably varied across the state, however, and conversion to short-

term rental units may be putting more significant pressure on housing markets in areas with a high

concentration of seasonal homes and heavy tourist demand, or in locations where this is a small number

of homes overall. In Hancock County, for example, active short term rental inventory made up close to

10% of the total housing stock, and those that might otherwise be comparable to NOAH housing

22

made

up about 3% of the total stock. In Lincoln and Franklin Counties, short-term rentals made up just over 6%

of the total housing stock, and those comparable to NOAH housing made up 2.5% and 1.76% of the total

stock, respectively. For breakdown of short-term rental inventory by county, see Appendix Page 6.

Housing Availability and Affordability

The demand-side and supply-side trends described impact both affordability and availability in Maine’s

housing market, making it difficult for Mainers to find available housing that they can afford, especially in

the Coastal region. Improving this will require aligning housing supply with the amount, type and location

of homes needed by Maine’s existing and future households.

Rental Affordability

Median rent for a 2-bedroom unit, utilities included, has historically been unaffordable in Maine, meaning

that the median rent across the state exceeded the rent affordable to the median renter (under a

standard definition set by HUD, rent is considered “affordable” when it does not exceed 30% of monthly

income) (Figure 25). Between 2016 and 2021, Maine saw a significant uptick in median rents, along with

rising median incomes, a trend that has occurred nationally.

Figure 25: Rental Affordability in Maine, 2000 - 2020

Source: MaineHousing Rental Affordability Index

22

Luxury units and large homes with over 3 bedrooms removed.

$737

$825

$857

$847

$834

$810

$826

$850

$965

$976

$658

$675

$696

$720

$746

$729

$746

$754

$770