K E Y P O I N T S

The Philippines has one of the

highest teenage pregnancy

rates among the ASEAN

member states.

More than 500 adolescents are

becoming pregnant and giving

birth every day.

Childbearing in adolescence

carries increased risks for poor

health outcomes for both

mother and child, and lower

educational attainment and

employability, causing economic

losses to the country.

Comprehensive sexuality

education alongside better

access to services for the

adolescent is the key to ending

teenage pregnancy.

POLICY BRIEF

January 2020

Eliminating Teenage

Pregnancy in the Philippines

# irls ot

G N M

oms:

#

The Philippines’ population will reach 108.8 million in 2020, according to the

Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) estimate. More than 53 million are below

25 years of age, including 10.3 million adolescent girls (10-19 years old).

Countries with a “demographic window of opportunity” and large shares of

young people, such as the Philippines, have an opportunity to accelerate

development if strategic investments are made. This is a phenomenon known

as the “demographic dividend” which is discussed in Chapter 13 of the

Philippines Development Plan 2017-2022.

This is exactly how countries like Japan achieved economic growth – by reaping

a demographic dividend by investing in health, education, and employability of

young people. Looking back in the 1970s, the Philippines, Thailand, and

Republic of Korea (South Korea) shared almost a similar population – South

Korea 32 million, Thailand 37 million, and the Philippines 36 million. 50 years

later in 2020, South Korea’s population has increased by 59% to 51 million,

Thailand by 189% to 70 million, and the Philippines by 304% to 109 million.

The ranking of GNI per capita of these countries is the opposite to the

population growth, with South Korea the highest at 30,600 USD, Thailand at

6,610 USD and the Philippines at 3,830 USD, according to the World Bank.

2

3

4

5

1

A Threat to the Economic Growth of the Country

One of the most pressing issues that the Filipino youth are facing today is

teenage pregnancy. A UNFPA-commissioned study in 2016 revealed that those

adolescents in the Philippines who have begun childbearing before the age of

18 are less likely to complete secondary education compared to the

adolescents who have not begun childbearing. The non-completion of

secondary education impacts employment opportunities in the future and total

life earnings of families. The net estimated effect of early childbearing due to

lost opportunities and foregone earnings can be as high as 33 Billion pesos

annual losses for the country.

In the Nairobi Summit in November 2019 that marked the 25th anniversary of

the landmark International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD),

the Government of the Philippines expressed a strong pledge to recommit the

country to the 1994 ICPD Programme of Action that promotes sexual and

reproductive health (SRH), reproductive rights, gender equality, and

empowerment of adolescents and youth. Without ensuring full and equal

access to sexual reproductive health and reproductive rights for all Filipinos

including the adolescent and youth, young Filipinos will not be able to fulfill

their full potential and the country will risk missing a demographic dividend.

6

7

8

15F North Tower, Rockwell BusinessCenter

Sheridan, Sheridan cor. United Sts., Highway

Hills, Mandaluyong City,

Philipines 1550

www.philippines.unfpa.org

UNITED NATIONS POPULATION FUND

Ensuring rights and choices for all

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

@UNFPAph

(632) 7902 9900

Policy Brief

2

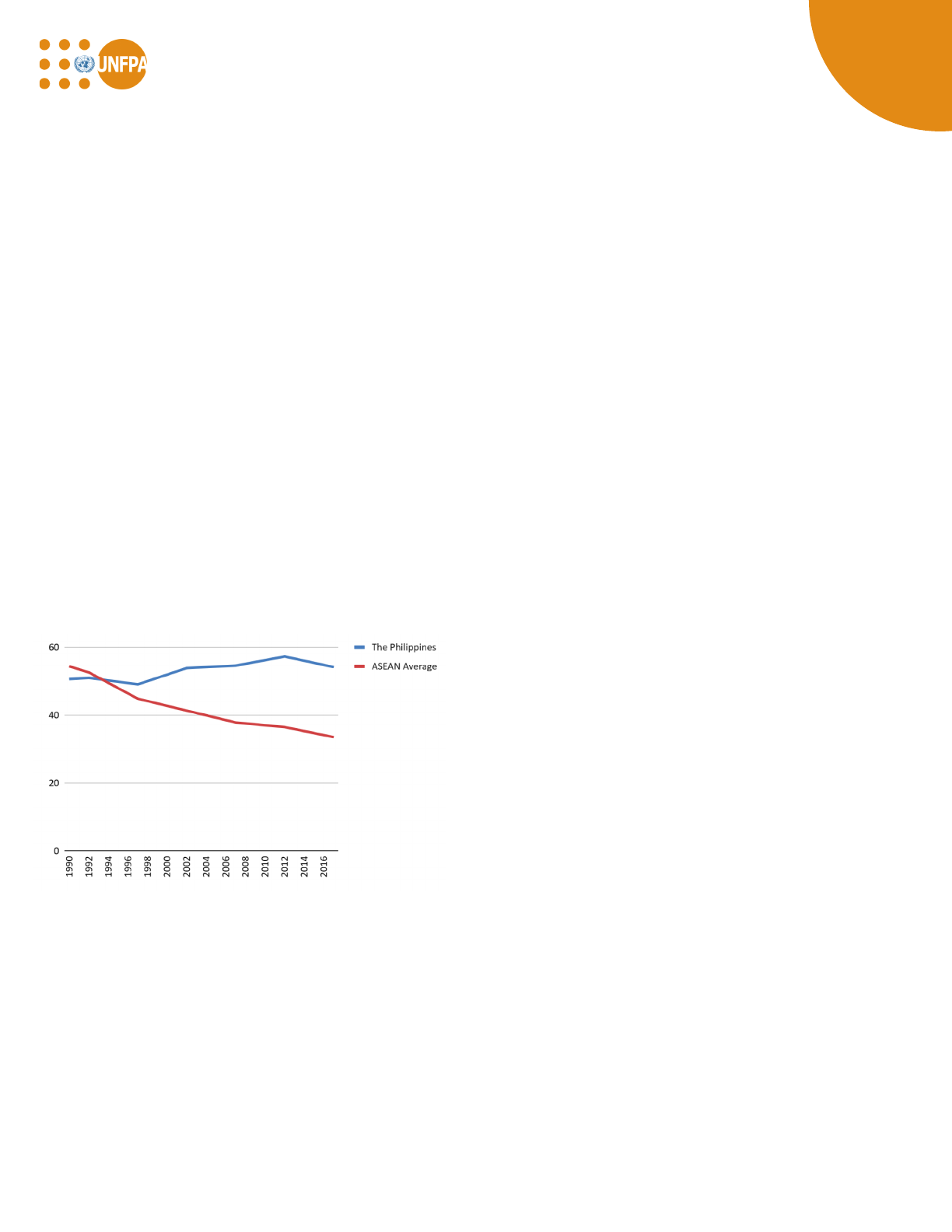

Figure 1. Adolescent Birth Rate

per 1,000 live birth in women aged 15-19 years old

Adopted from the World Bank data. Retrieved from:

(http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.ADO.TFRT)

The teenage pregnancy rate in the Philippines was 10%

in 2008, down to 9% in 2017. Live births by teenage

mothers (aged 10-19) in 2016 totalled 203,085, which

slightly decreased to 196,478 in 2017 and 183,000 in

2018. Still, the Philippines has one of the highest

adolescent birth rates among the ASEAN Member States.

Recent World Bank data shows that the Philippines has

47 births annually per 1,000 women aged 15-19, higher

than the average adolescent birth rates of 44 globally

and 33.5 in the ASEAN region [cf. Lao PDR (76), Cambodia

(57), Indonesia (48) and Thailand (43)]. This entails that

more than 500 Filipino adolescent girls are getting

pregnant and giving birth every day. UNFPA echoes the

sense of urgency demonstrated by NEDA and POPCOM,

which recently described the still alarmingly high teenage

pregnancy rate in the country as a “national emergency”.

Teenage Pregnancy in the Philippines

9

10

11

12

It is also crucial to note that out of live births within the

15-19 age group, which comprised 11.4% of all live

births, only 3% is fathered by men of the same age group

(PSA-CRSV, 2017). This data suggests that teenage

pregnancies among girls among the 15-19 years old may

be a result of coercion and unequal power relations

between girls and older men. The 2015 Baseline Study

on Violence Against Children also reinforced this and

further highlighted that verbal insistence and emotional

blackmail are the usual forms of sexual coercion in

dating relationships.

13

14

Childbearing in adolescence carries increased risks for

poor health outcomes for both mother and child; and

the younger the adolescent, the greater the risks.

Pregnancy during adolescence is associated with a

higher risk of health problems like anemia, sexually

transmitted infections (STIs), postpartum hemorrhage,

and poor mental health outcomes such as depression,

and even suicide. Adolescents who become pregnant at

an early age have associated risk factors such as having

greater age differences with their partners, which may

put them at greater risk of domestic violence, as well as

acquiring HIV and other STIs.

Poorer Health Outcomes Related to

Teenage Pregnancies

Vulnerabilities of Filipino Adolescents

Closely-spaced pregnancies. Adolescents in the

Philippines are also at risk for multiple and frequent

pregnancies. The following factors contribute to shorter

birth intervals and multiple pregnancies in adolescence:

1) lower educational attainment and economic status; 2)

poor access to contraception exacerbated by legal

barriers to access modern contraception; 3) challenges in

the implementation of comprehensive sexuality

education (see below); and 4) limited service delivery

points providing adolescent and youth-friendly sexuality

and reproductive health services.

Contributory risk behaviors. Adolescent mothers are

more exposed to domestic violence. Global data shows

women who experience intimate partner violence have a

16% greater chance of having a low birth-weight baby,

and are more than twice as likely to experience

depression – all factors that can negatively impact the

child’s development.

15

16

17

18

19

Barriers to Accessing Comprehensive Care

Discordance in legal provisions (legal age for consent for

services such as contraception is older than the age of

consent to have sex) puts developmentally capable,

sexually active young people who often do not want to

disclose sexual activity to parents at risk by requiring

them to obtain parental consent to access SRH services.

20

Policy Brief

Socio-cultural norms reinforcing stigma and

discrimination, as well as lack of availability,

affordability, and accessibility of adolescent-

friendly health services also pose greater

health risks for youth and adolescents, by

preventing these young people from accessing

comprehensive and quality health services

they need.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

3

21,22

Comprehensive Sexuality Education

The 2012 RPRH Act includes a provision that

mandates the Department of Education to

implement age and development-appropriate

Comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE) in

formal and non-formal education settings. The

long delay in the adoption and integration of

CSE in the K-12 Curriculum is a significant

missed opportunity to provide young people

with non-judgmental and scientifically accurate

and age-appropriate SRH information that

would curb the knowledge gap and provide life

skills needed to make informed decisions

related to risk behaviors with consequences to

their health.

23

24

Recommendations

All levels of the government have the

responsibility to ensure that adolescent and

youth populations enjoy the highest attainable

standard of health and access to quality health

services including SRH. Adolescents and youth

deserve to enjoy the full extent of their rights

and the ‘triple dividend’ of improving their

health now, their lives in the future, and the

next generation by investing in their health.

There are examples of countries within Asia

and the Pacific, which are enacting laws and

policies that among others, seek to recognize

the evolving capacities of youth, facilitate

access to sexuality and reproductive health

information and services, protect against

discrimination and stigma, and recognize

privacy rights.

Increasing adolescent and youth resilience

and protection. Contrary to popular belief,

there is no evidence that shows sexuality

education programs lead to early sexual debut

or increased sexual activity. CSE is the

cornerstone of improving the SRH of young

people. In order to make healthy, responsible

decisions, young people need accurate

information about puberty, reproduction,

relationships, sexuality, the consequences of

unsafe sex, and how to avoid HIV, STIs, and

unintended pregnancy. They also need the

skills and confidence to be able to deal with

peer pressure and negotiate safe and

consensual relationships. CSE programs that

address the above situations have been

proven not only to have a positive impact on

knowledge and attitudes, but also to

contribute to safer sexual practices (such as

delaying sexual debut, reducing the number of

partners, and increasing condom and

contraceptive use). Moreover, CSE can also

reduce the negative consequences of unsafe

sex.

25

26,27

28

29

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Item 1

12.5%

Item

12.5

Item

12.5

Item 4

12.5%

Item 5

12.5%

Item 6

12.5%

Item 7

12.5%

Item 8

12.5%

Policy Brief

4

increased

Resilience &

Protection

Parental

skills

for

adolescent

& youth

Adolescent

& Youth

Friendly

services

Social Protection

Mechanism

inter-agency

coordination &

collaboration

better

fertility

rates

management

use of media &

communications

Managing fertility rates, improving education and

employment opportunities of young people to reap the

demographic dividend. In many countries,

postponement of the first birth has contributed greatly

to overall fertility reduction. In order not to miss the the

current “demographic window of opportunity,” it is

imperative for the Philippines to institute better health

reforms to manage the total fertility, alongside reforms

to improve employment opportunities for young people.

More effective and scaled-up community mobilization

interventions will be required to discourage early

marriage and teenage pregnancy.

Enhancing social protection mechanisms. More public

investment needs to be made to mitigate teenage

pregnancy, in addition to prevention. Those adolescents

who have already become parents need to be provided

with access to quality social welfare services (e.g.

postpartum family planning support for teenage parents

to space pregnancy and delay the next birth) and case

management interventions, particularly when any one of

the young parents is assessed to be himself or herself a

child in need of special protection. To adequately

address the SRH needs of adolescents, health care must

be affordable and accessible to all young people.

Improving access to adolescent and youth-friendly

services, including contraceptives. Adolescent and

youth-friendly services provide privacy in a welcoming

and respectful environment. These services can be

provided in facilities by those trained to appropriately

respond to the needs of the adolescent and youth in a

non-discriminatory, helping and confidential manner.

Section 7 of the 2012 RPRH Act states that minors in the

Philippines require written parental consent to access

family planning services including contraceptives. The

only exception is for minors who have already given birth

or experienced a miscarriage. Age of consent laws to

access sexual and reproductive health services can

discourage adolescents to fully exercise their sexual and

reproductive rights.

UNFPA promotes universal access to sexual and

reproductive health and rights which includes access to

health information and services for adolescents to help

facilitate informed choices. With or without parental

consent, adolescents should be able to access

appropriate RH services and information, ensuring that

Figure 2. Recommendations to Reduce Teenage Pregnancy

data,

statistics,

evidence

Rights &

Well-being

of Adolescents

30

31

32

it is informed, confidential, and private. This is further

emphasized in the Convention on the Rights of the Child

General Comments 20, which underscores the evolving

capacity of the child to make decisions on matters

relating to their education, health, sexuality, family life,

and judicial and administrative proceedings" (para. 23).

The Convention emphasizes that all adolescents have the

right to have access to confidential medical counselling

and advice without the consent of a parent or guardian,

irrespective of age, if they so wish (para. 39).

Strengthening parental skills for adolescents and youth.

Parents and families also play an important role as

health educators and are an important influence on

young people’s attitudes and behaviors, as well as on

their overall health and well-being. Even when

adolescents and youth want to discuss sexuality and

reproductive health issues with their parents, they tend

to be unable to provide necessary information in an

effective manner due to socio-cultural taboos and their

own lack of knowledge, and therefore the parents need

to be supported as well. Studies have suggested that

adolescent girls’ connectedness to parents, particularly

their mothers, and a family environment that supports

gender equality contribute to delayed first sex among

girls.

33

34

35

36

Strengthening inter-agency coordination and

collaboration, both horizontally and vertically. No single

agency can design and deliver on adolescents’ unique

health and development needs across all settings. A

comprehensive Adolescent Health and Development

Program (AHDP) with strong inter-agency coordination

and collaboration is needed wherein each agency

involved clearly understands its own role and assumes

accountability for achieving the results assigned under

the program. In light of the introduction of Universal

Health Care too, it will be critical to ensure that

enhanced provision of information and services for

adolescents and youth as directed by national laws and

policies are adequately implemented in Local

Government Units with sufficient allocation of budget

and human resources. Surveys like the Young Adult

Fertility and Sexuality Survey (YAFSS) provide valuable

data which informs the creation and implementation of

relevant adolescent SRH services and programs.

Continuing this survey at regular intervals will inform

better planning and monitoring, and thereby improve

service delivery for adolescents and youth .

Robust data and statistics, and more updated evidence

to inform policies and programs for adolescents. Sound

policy formulation, effective implementation, monitoring

and coordination hinge on the availability of quality

data. More regular undertaking of the above-mentioned

Young Adult Fertility and Sexuality Survey (to be

renamed as Adolescent Health and Development Survey)

is crucial, as discussed earlier.

Maximizing use of media and communications for

health promotion. Today’s young people are growing in

a rapidly changing society. Urbanization and

globalization have increased access to internet, social

media and new information technologies that become

platforms for interaction and knowledge sharing

especially among young people. As UNFPA’s 2017 report

indicated, as children grow older, their internet usage

increases. This provides an opportunity to implement

programs directed at young people to harness the

potential of these online platforms as avenues to

promote positive self-image, responsible sexuality and

help-seeking behavior.ome

Policy Brief

5

Ultimately, UNFPA promotes the rights and well-being

of all adolescents. UNFPA supports the government in

introducing legislation and interventions that recognize

the rights of adolescents to take increasing responsibility

for decisions affecting their lives and express views on all

matters of concern to them. All laws, policies, and

programs that aim to prevent teen pregnancy should not

in any way, either directly or indirectly, disadvantage,

stigmatize, or penalize adolescents for factual

consensual and non-exploitative sexual activity.

The United Nations Population Fund welcomes the

promulgation of national laws and policies for the

prevention and mitigation of teenage pregnancies, as

it likewise ensures alignment of national programs with

the Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and

Adolescents’ Health which seeks to end preventable

deaths, ensure health and well-being and expand

enabling environments.

Furthermore, the enactment of national policies on

teenage pregnancy will contribute to the attainment of:

the Sustainable Development Goals, Ambisyon Natin

2040, Philippine Development Plan, Philippine Health

Agenda, Philippine Youth Development Plan, National

Plan of Action for Children and the Philippine Plan of

Action to End Violence Against Children.

UNFPA supports the core commitments of the 2019

Declaration on Addressing the Education, Health and

Development Issues of Early Pregnancy in the Philippines

during the Kapit Kamay Teen Summit organized by DepEd,

DOH, and NEDA in August 2019.

A whole-of-government approach is required to actualise

the commitments of Kapit Kamay to ensure that all young

Filipinos and Filipinas are empowered to make informed

and responsible decisions.

CALL TO ACTION

38

37

Policy Brief

Philippines Statistic Authority. Updated Population Projections Based on the Results of 2015 POPCEN. Retrieved from:

https://psa.gov.ph/content/updated-population-projections-based-results-2015-popcen. October 2019.

Mapa, D., UNFPA, Harvesting the Demographic Dividend Fast: Necessary for Ambisyon Natin (2040). 2015

Weeks, John R. Population: An Introduction to Concepts and Issues: Cengage Learning. 2020

World Bank Group. World Total Population. Retrieved from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL 2019

World Bank Group. GNI per capita, PPP (current international $). Retrieved from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GNP.PCAP.PP.CD.

2019

United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). Longitudinal Cohort Study on the Filipino Child Baseline Data. 2016.

Herrin, A. Education, Earnings and Health Effects of Teenage Pregnancy in the Philippines. Retrieved from:

https://philippines.unfpa.org/en/publications/education-earnings-and-health-effects-teenage-pregnancy-philippines. 2016

National Economic and Development Authority. Retrieved from: http://www.neda.gov.ph/philippine-statement-of-commitment-during-the-

nairobi-summit-on-international-conference-on-population-and-development-icpd/. 2019

Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA). National Demographic and Health Survey 2017. Retrieved from:

https://psa.gov.ph/sites/default/files/PHILIPPINE%20NATIONAL%20DEMOGRAPHIC%20AND%20HEALTH%20SURVEY%202017_new.pdf

Philippine Statistics Authority. 2016, 2017 and 2018 Civil Registry and Vital Statistics.

World Bank Group. Adolescent fertility rate (births per 1,000 women ages 15-19). Retrieved from:

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.ADO.TFRT. 2019

POPCOM. “POPCOM calls for prevention of repeat teenage pregnancy”. The Philippine Information Agency news. Retrieved from

https://pia.gov.ph/news/articles/1029554. 1 November 2019.

Philippine Statistics Authority. 2017 Civil Registry and Vital Statistics.

Council for the Welfare of Children, & UNICEF Philippines. Executive Summary of National Baseline Study on Violence against Children:

Philippines. Retrieved from: https://www.unicef.org/philippines/media/491/file. 2016.

WHO Media Centre. Adolescent Pregnancy Fact Sheet. Retrieved from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs364/en. Updated

September 2014.

Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health.Retrieved from:

http://www.searo.who.int/entity/child_adolescent/topics/adolescent_health/adolescent_sexual_reproductive/en.

Christofides, N.J., Jewkes, R.K., Dunkle, K.L., Nduna, M., Shai, N.J. and Sterk, C. Early adolescent pregnancy increases risk of incident HIV

infection in the Eastern Cape, South Africa: a longitudinal study. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 17: 18585.

doi:10.7448/IAS.17.1.18585. 2014

Philippines Statistic Authority (PSA) and ICF. Philippines National Demographic and Health Survey 2017. Quezon City, Philippines and

Rockville, Maryland, USA: PSA and ICF. 2018

UNICEF, Child Protection Network and CWC Systematic Literature Review on Drivers of Violence. 2015

Melgar, J. L. D., Melgar, A. R., Festin, M. P. R., Hoopes, A. J., & Chandra-Mouli, V. Assessment of country policies affecting reproductive health

for adolescents in the Philippines. Reproductive Health, 15(1), 205. 2018

UNESCO Young People and the Law in Asia and the Pacific: A Review of Laws and Policies Affecting Young People’s Access to Sexual and

Reproductive Health and HIV services. 2013.

UNESCO, UNAIDS, UNFPA, UNICEF, UN WOMEN, & WHO.International technical guidance on sexuality education: An evidence-informed

approach (2nd revised ed.). Retrieved from: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000260770. 2018

Melgar, J. L. D., Melgar, A. R., Festin, M. P. R., Hoopes, A. J., & Chandra-Mouli, V. Assessment of country policies affecting reproductive health

for adolescents in the Philippines. Reproductive Health, 15(1), 205. 2018

Ibid

UNESCO Young People and the Law in Asia and the Pacific: A Review of Laws and Policies Affecting Young People’s Access to Sexual and

Reproductive Health and HIV services. 2013.Department of Health and Commission on Population. 3rd Annual Report on the

Implementation of the Responsible Parenthood and Reproductive Health Act of 2012. April 2017

ibid

Demographic Research and Development Foundation, Inc and UP Population Institute. Young Adult Fertility and Sexuality Study (YASS)

2013. 2016

ibid

ibid

United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). Girlhood, Not Motherhood: Preventing Adolescent Pregnancy. New York. 2017.

Department of Health and Commission on Population. 3rd Annual Report on the Implementation of the Responsible Parenthood and

Reproductive Health Act of 2012. April 2017

UNFPA. Adolescent pregnancy. Retrieved from: https://www.unfpa.org/adolescent-pregnancy. Last update: 19 May 2017.

UNFPA. State of the World Population 2019. Retrieved from: https://philippines.unfpa.org/en/publications/state-world-population-2019-2.

April 2019

United Nations. Joint General Comment No. 4 (2017) of the Committee on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members

of Their Families and No. 23 (2017) of the Committee on the Rights of the Child on State obligations regarding the human rights of children

in the context of international migration in countries of origin, transit, destination and return. Retrieved from: https://documents-dds-

ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G17/343/65/PDF/G1734365.pdf?OpenElement. 2017

Ibid

United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) and Center for Health Solutions and Innovations (CHSI): Sex at the Dinner Table: Are Filipino

Parents Ready to Talk with their Teens about Sex? 2016

UNFPA. The Longitudinal Cohort Study of the Filipino Child. Wave 2 Final Survey Report. 2017

Kapit Kamay: Empowering The Youth To Make Informed Choices. The 2019 Declaration on Addressing the Education, Health and

Development Issues of Early Pregnancy. PICC, Pasay City, Philippines. 2019

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

R E F E R E N C E S

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -