United States Office of Prevention, Pesticides EPA 742-R-98-009

Environmental Protection and Toxic Substances December 1998

Agency (7409)

Environmental Labeling

Issues, Policies, and

Practices Worldwide

Recycled/Recyclable • Printed with Vegetable Based Inks on Recycled Paper (20% Postconsumer)

Environmental Labeling

Issues, Policies, and Practices Worldwide

December 1998

prepared for:

Pollution Prevention Division

Office of Pollution, Prevention and Toxics

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

(7409)

401 M Street, SW

Washington, DC 20460

(202) 260-4000

EPA Contract No. 68-W6-0021

Table of Contents

i

Table of Contents

Environmental Labeling: Scope of this Report ............................... xii

1. Introduction ............................................................1

2. Environmental Labeling: The US Perspective ..................................5

2.1. Background ......................................................5

2.2. Environmental Labeling in the US .....................................6

3. Definition of Environmental Labeling ........................................9

3.1. Positive Labeling Programs .........................................11

Seal-of-Approval .................................................11

Single-attribute Certification Programs ................................11

3.2. Negative Labeling Programs ........................................12

Hazard/Warning Labels ............................................12

3.3. Neutral Labeling Programs .........................................13

Information Disclosure Programs ....................................13

Report Cards ....................................................13

4. Overview of Labeling Programs Worldwide ..................................15

4.1. Introduction .....................................................15

4.2. Fundamental Information ...........................................15

Program Type ....................................................16

Participation ....................................................18

Label Type ......................................................19

Administration ...................................................21

Financing .......................................................22

Year Founded ....................................................22

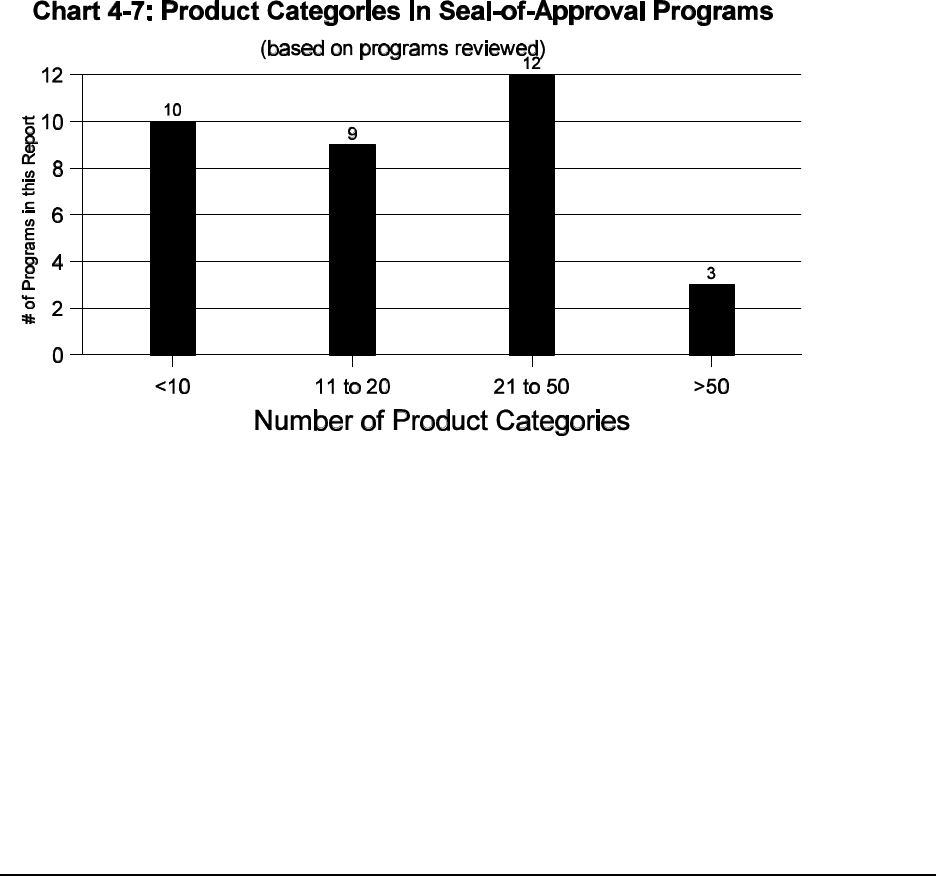

Product Categories ...............................................24

Number of Awards ................................................25

4.3. Geographic Representation .........................................26

4.4. Program Methodology .............................................35

Program Goals ...................................................35

Program Methodologies ............................................36

Stakeholder Involvement ...........................................38

4.5. Program Breadth .................................................39

Use of Non-Environmental Attributes .................................39

Use in Procurement ...............................................40

Use Beyond Retail ................................................42

Other Programs/Activities ..........................................44

4.6. Changes to Environmental Labeling Programs ..........................45

Table of Contents

ii

4.7. Coordination Efforts Among Programs ................................46

4.8. Trade Issues .....................................................48

5. Forces Affecting Environmental Labeling Programs ............................51

5.1. Public/Societal Interests ............................................52

5.2. Consumer Interest ................................................54

5.3. Retailer’s Interests ................................................55

5.4. Producer’s Interests ...............................................55

5.5. Operating Costs and Profit ..........................................56

5.6. Standardization of Environmental Labeling Programs ....................57

5.7. Procurement Programs .............................................57

6. Recent Trends and Future Outlook .........................................59

6.1. The Proliferation and Globalization of Environmental Labeling Programs ....60

6.2. Standardization ..................................................62

6.3. Wedge Issues ....................................................64

Program Goals ...................................................64

Limitations to Standardization .......................................65

6.4. Future Outlook ...................................................66

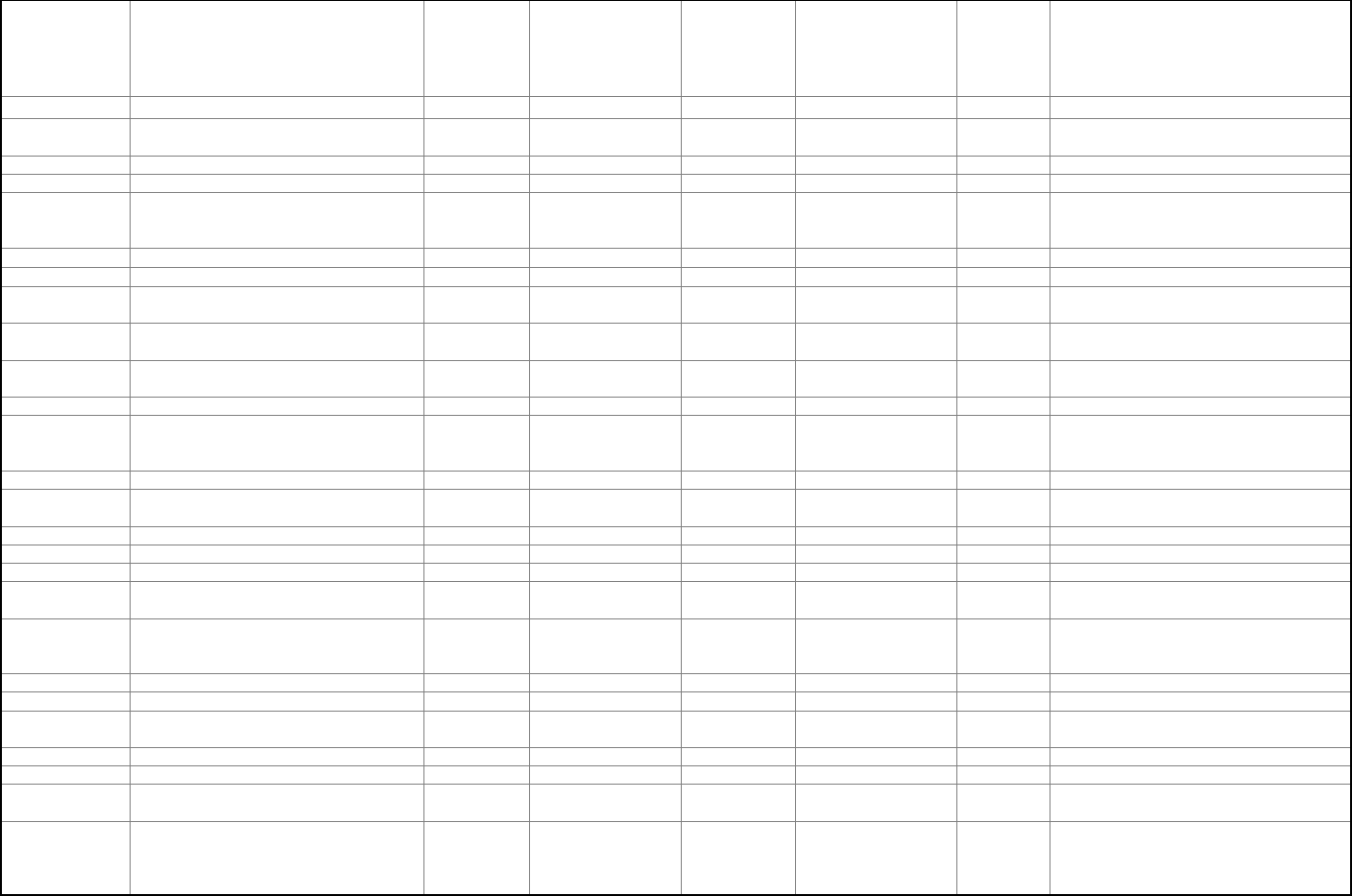

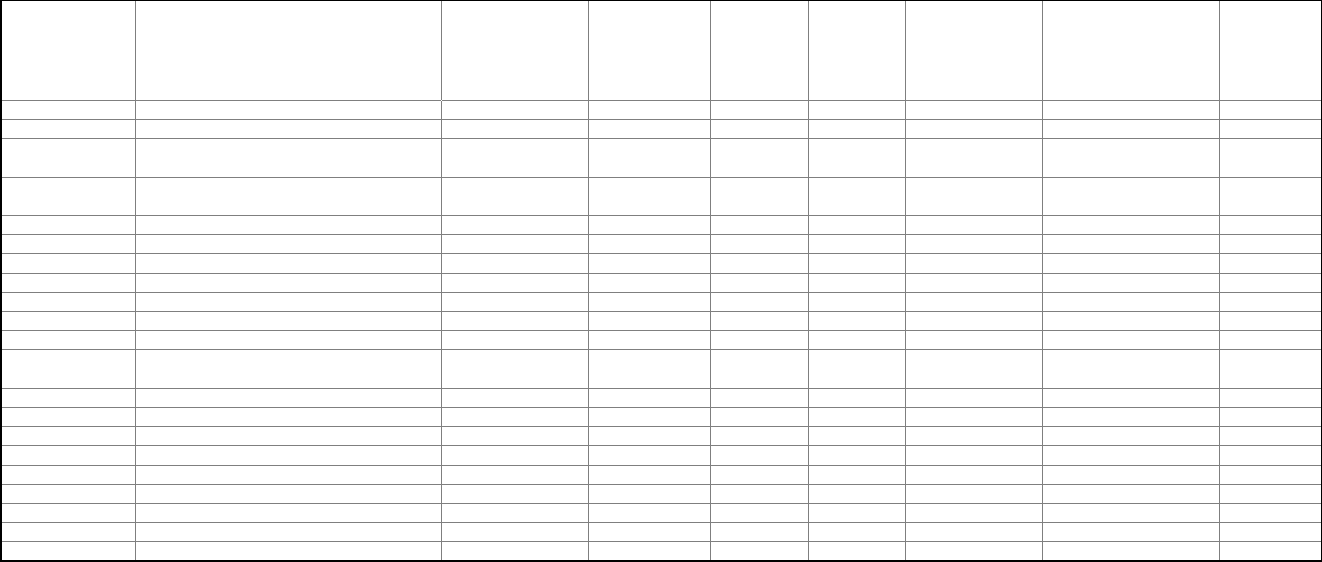

Appendix A: Overview Table of Environmental Labeling Programs

Covered in This Report ................................................... A-1

Appendix B: Summaries of Environmental Labeling Programs

Covered in This Report

List of Environmental Labeling Programs Covered in This Report .................... B-i

Austrian Eco-label ...........................................................B-1

Introduction ..........................................................B-1

Recent Developments ..................................................B-1

Program Summary .....................................................B-1

Program Methodology ..................................................B-2

Other Information .....................................................B-3

References ...........................................................B-3

Product Categories .....................................................B-3

Table of Contents

iii

Canada's Environmental Choice

m

Program: the Ecologo

m

...........................B-5

Introduction ..........................................................B-5

Recent Developments ..................................................B-5

Program Summary .....................................................B-5

Program Methodology ..................................................B-6

Other Information .....................................................B-7

References ...........................................................B-8

Product Categories .....................................................B-9

China's Ecolabeling Program ..................................................B-13

Introduction .........................................................B-13

Program Summary ....................................................B-13

Program Methodology .................................................B-14

References ..........................................................B-15

Product Categories ....................................................B-15

Croatia’s Environmental Label ................................................B-17

Introduction .........................................................B-17

Program Summary ...................................................B-17

References ..........................................................B-18

Product Categories ....................................................B-18

The Czech Ecolabel .........................................................B-21

Introduction .........................................................B-21

Program Summary ....................................................B-21

Program Methodology .................................................B-21

Other Information ....................................................B-22

References ..........................................................B-22

Product Categories ....................................................B-22

The Nordic Council’s Nordic Swan Label ........................................B-23

Introduction .........................................................B-23

Recent Developments .................................................B-23

Program Summary ....................................................B-24

Program Methodology .................................................B-26

Other Information ....................................................B-27

References ..........................................................B-27

Product Categories ....................................................B-28

Table of Contents

iv

European Union Eco-label Programme ..........................................B-31

Introduction .........................................................B-31

Recent Developments .................................................B-31

Program Summary ....................................................B-33

Program Methodology .................................................B-34

Other Information ....................................................B-37

References ..........................................................B-38

Product Categories ....................................................B-39

France’s NF-environnement Mark ..............................................B-41

Introduction .........................................................B-41

Recent Developments .................................................B-41

Program Summary ....................................................B-42

Program Methodology .................................................B-43

Other information .....................................................B-44

References ..........................................................B-44

Product Categories ....................................................B-45

Germany's Blue Angel .......................................................B-47

Introduction .........................................................B-47

Recent Developments .................................................B-47

Program Summary ....................................................B-48

Program Methodology .................................................B-49

Other Information ....................................................B-50

References ..........................................................B-50

Product Categories ....................................................B-51

Germany’s Green Dot Program ................................................B-55

Introduction .........................................................B-55

Recent Developments .................................................B-55

Program Summary ....................................................B-55

Program Methodology .................................................B-56

Other Information ....................................................B-57

References ..........................................................B-57

India’s Ecomark ............................................................B-59

Introduction .........................................................B-59

Recent Developments .................................................B-59

Program Summary ....................................................B-60

Program Methodology .................................................B-60

Other Information ....................................................B-61

References ..........................................................B-63

Product Categories ....................................................B-64

Table of Contents

v

Japan's Ecomark ............................................................B-65

Introduction .........................................................B-65

Recent Developments .................................................B-65

Program Summary ....................................................B-66

Program Methodology .................................................B-66

Other Information ....................................................B-67

References ..........................................................B-67

Product Categories ....................................................B-68

South Korea’s Eco-mark .....................................................B-71

Introduction .........................................................B-71

Recent Developments .................................................B-71

Program Summary ....................................................B-71

Program Methodology .................................................B-72

References ..........................................................B-72

Product Categories ....................................................B-72

Malaysia’s Product Certification Program ........................................B-75

Introduction .........................................................B-75

Program Summary ....................................................B-75

Program Methodology .................................................B-76

Other Information .................................................B-76

References ..........................................................B-77

Product Categories ....................................................B-77

Netherland’s Stichting Milieukeur ..............................................B-79

Introduction .........................................................B-79

Recent Developments .................................................B-79

Program Summary ....................................................B-79

Program Methodology .................................................B-80

Other Information ....................................................B-81

References ..........................................................B-81

Product Categories ....................................................B-81

New Zealand’s Environmental Choice ..........................................B-85

Introduction .........................................................B-85

Recent Changes ......................................................B-85

Program Summary ....................................................B-85

Program Methodology .................................................B-86

Other Information ....................................................B-87

References ..........................................................B-87

Product Categories ....................................................B-87

Table of Contents

vi

Singapore’s GreenLabel ......................................................B-89

Introduction .........................................................B-89

Recent Developments .................................................B-89

Program Summary ....................................................B-89

Program Methodology .................................................B-91

Other Information ....................................................B-91

References ..........................................................B-92

Product Categories ....................................................B-92

Spain’s AENOR - Medio Ambiente ............................................B-95

Introduction .........................................................B-95

Recent Developments .................................................B-95

Program Summary ....................................................B-95

Program Methodology .................................................B-96

Other Information ....................................................B-96

References ..........................................................B-96

Product Categories ....................................................B-96

Sweden’s Good Environmental Choice ..........................................B-99

Introduction .........................................................B-99

Program Summary ....................................................B-99

Program Methodology ................................................B-100

Other Information ...................................................B-100

References .........................................................B-100

Taiwan’s Green Mark Program ...............................................B-101

Introduction ........................................................B-101

Recent Developments ................................................B-101

Program Summary ..................................................B-102

Program Methodology ................................................B-104

Other Information ...................................................B-104

References .........................................................B-105

Product Categories ...................................................B-105

Thailand’s Green Label Scheme ..............................................B-107

Introduction ........................................................B-107

Recent Developments ................................................B-107

Program Summary ...................................................B-107

Program Methodology ................................................B-108

Other Information ...................................................B-108

References .........................................................B-108

Product Categories ...................................................B-109

Table of Contents

vii

US PROGRAMS

Rechargeable Battery Labeling ...............................................B-111

Introduction ........................................................B-111

Program Summary ...................................................B-111

Program Methodology ................................................B-112

Other Information ...................................................B-113

References .........................................................B-113

Product Categories ...................................................B-113

The Chlorine Free Products Association (CFPA) .................................B-115

Introduction ........................................................B-115

Program Summary ...................................................B-115

Program Methodology ................................................B-116

Other Information ...................................................B-116

References .........................................................B-116

Product Categories ...................................................B-116

US Environmental Protection Agency’s Consumer Labeling Initiative ................B-119

The Rainforest Alliance - ECO-O.K. Certification Program .........................B-121

Introduction ........................................................B-121

Program Summary ...................................................B-121

Program Methodology ................................................B-121

Other Information ...................................................B-123

References .........................................................B-123

HVS Eco Services' Ecotel

®

Certification ........................................B-125

Introduction ........................................................B-125

Program Summary ...................................................B-125

Program Methodology ................................................B-127

References .........................................................B-127

Product Categories ...................................................B-128

The Energy Guide: Household Appliance Energy Efficiency Labeling ................B-129

Introduction ........................................................B-129

Program Summary ...................................................B-129

Program Methodology ................................................B-131

References .........................................................B-131

Product Categories ...................................................B-132

Table of Contents

viii

US EPA Energy Star Programs ...............................................B-133

Introduction ........................................................B-133

Recent Developments ................................................B-133

Program Summaries ..................................................B-133

Program Methodology ................................................B-137

References .........................................................B-137

Product Categories ...................................................B-138

Fuel Economy Information Program ...........................................B-139

References .........................................................B-140

Pesticide Labeling under the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act .......B-141

Introduction ........................................................B-141

Program Summary ...................................................B-141

Enforcement ........................................................B-150

References .........................................................B-150

Green Seal ...............................................................B-153

Introduction ........................................................B-153

Recent Developments ................................................B-153

Program Summary ...................................................B-153

Program Methodology ...............................................B-154

Other Information ...................................................B-155

References .........................................................B-156

Product Categories ...................................................B-157

EPA'S Ozone Depleting Substance (ODS) Warning Label ..........................B-161

Introduction ........................................................B-161

Recent Developments ................................................B-161

Program Summary ...................................................B-161

References .........................................................B-163

California Proposition 65 ....................................................B-165

Introduction ........................................................B-165

Recent Developments ................................................B-165

Program Summary ...................................................B-166

Program Methodology ................................................B-167

References .........................................................B-167

Table of Contents

ix

Scientific Certification Systems’ Environmental Claims Certification Program .........B-169

Introduction ........................................................B-169

Recent Developments ................................................B-169

Program Summary ...................................................B-169

Program Methodology ................................................B-170

Other Information ...................................................B-170

References .........................................................B-170

Product Categories ...................................................B-171

Scientific Certification Systems’ Certified Eco-profile Labeling System ...............B-173

Introduction ........................................................B-173

Recent Developments ................................................B-173

Program Summary ...................................................B-174

Program Methodology ................................................B-175

Other Information ...................................................B-176

References .........................................................B-177

Product Categories ...................................................B-178

Scientific Certification Systems’ Forest Conservation Program ......................B-179

Introduction ........................................................B-179

Recent Developments ................................................B-179

Program Summary ..................................................B-180

Program Methodology ................................................B-181

Other Information ...................................................B-182

References .........................................................B-182

Product Categories ...................................................B-183

Scientific Certification Systems’ Nutriclean Food Safety Management Program .........B-185

Introduction ........................................................B-185

Recent Developments ................................................B-185

Program Summary ..................................................B-186

Program Methodology ................................................B-187

Other Information ...................................................B-187

References .........................................................B-187

Product Categories ...................................................B-188

Product Labeling under the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) ...................B-189

Introduction ........................................................B-189

Program Summary ...................................................B-189

Examples of TSCA Labels .............................................B-190

References .........................................................B-192

Table of Contents

x

Vermont Household Hazardous Product Shelf Labeling Program ...................B-193

Introduction ........................................................B-193

Recent Developments ................................................B-193

Program Summary ..................................................B-194

Program Methodology ................................................B-195

References .........................................................B-195

Product Categories ...................................................B-195

Water Alliances for Voluntary Efficiency (WAVE) ...............................B-197

Introduction ........................................................B-197

Program Summary ...................................................B-197

Program Methodology ................................................B-199

References .........................................................B-199

Product Categories ...................................................B-199

Buying Guides ............................................................B-201

Greening the Government: A Guide to Implementing

Executive Order 12873 .........................................B-201

References .........................................................B-201

The Green Pages ....................................................B-201

References .........................................................B-202

US EPA National Volatile Organic Compound Emission Standards

for Architectural Coatings .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . B-203

Introduction ........................................................B-203

Program Summary ..................................................B-203

Program Methodology ................................................B-205

References .........................................................B-205

Product Categories ...................................................B-205

Programs Under Development ................................................B-207

Brazilian Association for Standardization’s “ABNT - Qualidade Ambiental” .....B-207

Introduction ..................................................B-207

Program Summary ............................................B-207

Program Methodology ..........................................B-209

Other Information .............................................B-209

References ...................................................B-209

Product Categories .............................................B-209

Small Spark-Ignited Engine Environmental Labeling Program ................B-210

References ...................................................B-210

Electric Utility ......................................................B-210

References ...................................................B-211

Table of Contents

xi

Indonesian Environmental Labeling .....................................B-211

Introduction ..................................................B-211

References ...................................................B-212

Germany’s Type III Eco-report Card .....................................B-213

References ...................................................B-213

Hong Kong Ecolabeling Scheme ........................................B-213

References ...................................................B-214

Select Bibliography on Environmental Labeling ................... Bibliography-1

Table of Contents

xii

Table of Figures, Tables, and Charts

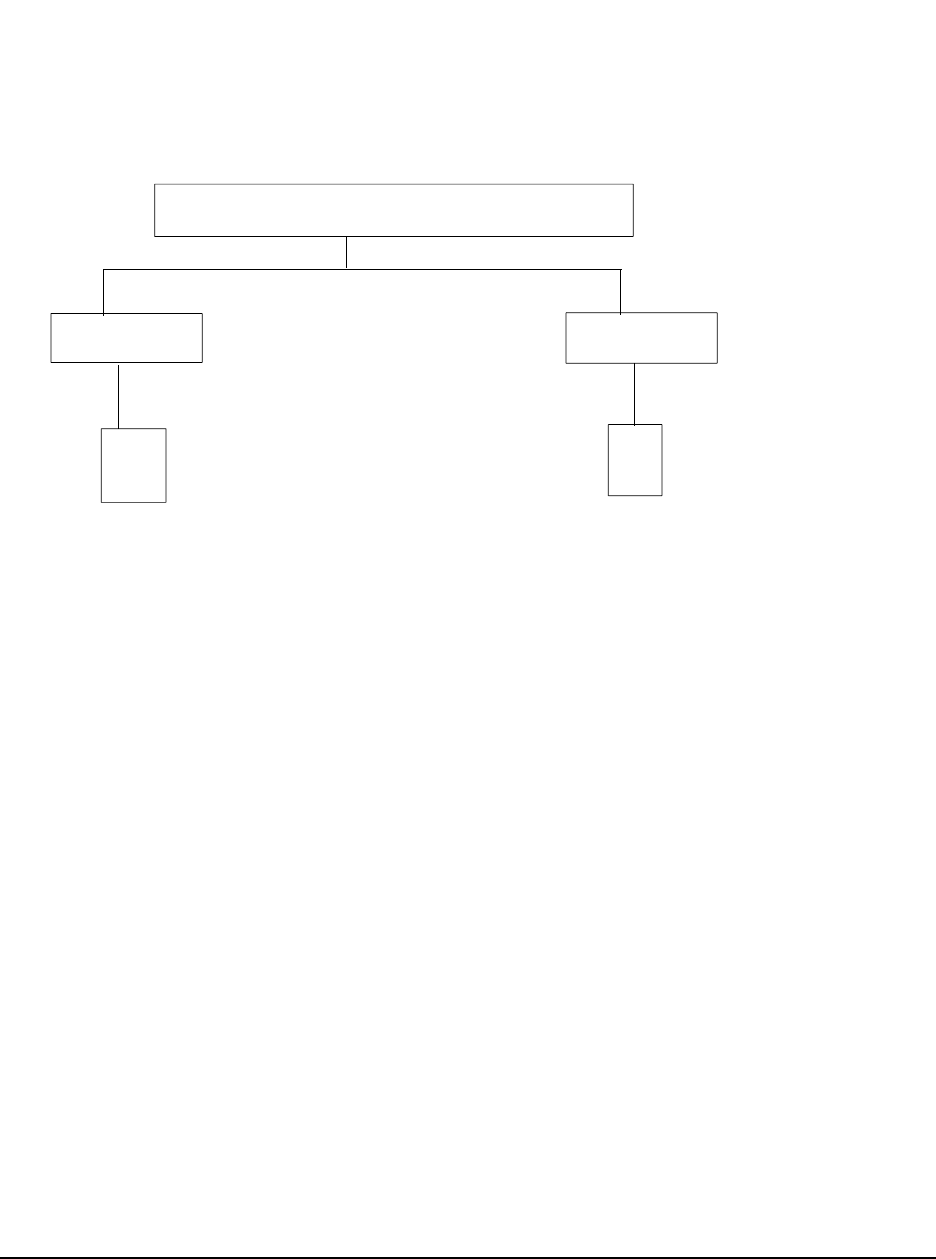

Figure 1: Classification of Environmental Labeling ................................. xv

Chart 1-1: Flow of Information from Manufacturers to Consumers .......................2

Chart 3-1: Classification of Environmental Labeling .................................10

Chart 4-1: Program Type .......................................................17

Chart 4-2: Participation in Labeling Programs ......................................18

Table 4-1: Participation by Program and Label Type .................................20

Chart 4-3: Programs by Label Type ...............................................20

Chart 4-4: Programs by Organization Type .........................................21

Chart 4-5: Programs by Financing Source ..........................................22

Chart 4-6: Number of Programs Founded by Year (<1997) ............................23

Chart 4-7: Product Categories in Seal-of-Approval Programs ..........................24

Chart 4-8: Number of Awards in Seal-of-Approval Programs ..........................25

Figure 2: Positive and Neutral Third Party Ecolabeling Programs Worldwide ..............27

Figure 3: Positive and Neutral Third Party Ecolabeling Programs in Europe ...............29

Figure 4: Positive and Neutral Third Party Ecolabeling Programs in Pacific Rim .......... .31

Figure 5: Positive and Neutral Third Party Ecolabeling Programs in

North and South America ................................................33

Table 4-2: Missions/Goals Given for Programs Covered in This Report ..................36

Chart 4-9: Programs by Methodology .............................................37

Chart 4-10: Programs by Stakeholder Involvement ...................................38

Chart 4-11: Programs that use Non-environmental Attributes ..........................40

Chart 4-12: Programs used in Procurement .........................................42

Chart 4-13: Use on Retail/Non-retail Products ......................................43

Chart 4-14: Programs With Other Activities ........................................44

Chart 4-15: Programs with Foreign-based Licenses ..................................46

Chart 4-16: Programs that Indicate Working with Other Countries ......................47

Chart 4-17: Programs that Participate in ISO .......................................48

Chart 4-18: Programs that Report Trade Conflicts ...................................50

Table 1: Toxicity Category Definition ..........................................B-144

Table 2: Hazard to Humans and Domestic Animal Precautionary Statements ...........B-146

Table 3: Acute Oral Toxicity Study

*

...........................................B-146

Table 4: Acute Dermal Toxicity Study .........................................B-147

Table 5: Acute Inhalation Toxicity Study .......................................B-147

Table 6: Primary Eye Irritation Study ..........................................B-148

Table 7: Primary Skin Irritation Study ..........................................B-148

Table 8: Dermal Sensitization Study ...........................................B-148

Table 9: Physical or Chemical Hazard Precautionary Statements ....................B-149

1

Verification refers to an evaluation process or determination that products or services meet specified

criteria or claims.

Scope of Report

xiii

Environmental Labeling: Scope of this Report

Labeling programs can be classified according to a number of program characteristics, as

illustrated on the following figure (Figure 1). The most important is whether the program relies

on first-party or third-party verification

1

. The former is performed by marketers on their own

behalf to promote the positive environmental attributes of their products. Programs relying on

first-party verification are not addressed in this report. Third-party verification is carried out by

an independent source that awards labels to products based on certain environmental criteria or

standards. Environmental labeling programs can also be characterized as positive, negative, or

neutral. Positive labeling programs typically certify that labeled products possess one or more

environmentally preferable attributes. Negative labeling warns consumers about the harmful or

hazardous ingredients contained in the labeled products. Neutral labeling programs simply

summarize environmental information about products that can be interpreted by consumers as

part of their purchasing decisions. Third-party environmental labeling programs can be further

classified as either mandatory or voluntary. Mandatory programs include hazard or warning

labels, and information disclosure labels. Voluntary labels are typically positive or neutral, and

are further classified as either report cards, seal-of-approval, or single-attribute certification

programs.

The US programs covered in this report include mandatory government programs, voluntary seal-

of-approval programs, single-attribute programs, hazard warning programs, and information

disclosure programs. Due to the scope of this report, not every labeling program that may be in

existence today is covered (e.g., food is not covered), and the report should not be seen as a

comprehensive study of all labeling programs worldwide. The report presents a snapshot of the

major environmental labeling programs in existence during the research phase for which

information was available.

xv

Figure 1: Classification of Environmental Labeling

Environmental Labeling

First-Party

Environmental Labeling Programs

Third-Party

Environmental Labeling Programs

Corporate-RelatedProduct-Related Mandatory Voluntary

Cause-Related

Marketing

(e.g., “Proceeds

donated to...”)

Claims

(e.g., Recyclable)

Promotion of

Corporate Env.

Activity or

Performance

Cause-Related

Marketing

(e.g., Company

supports WWF)

Hazard or

Warning

(e.g., Pesticides,

Prop. 65)

Environmental

Certification

Programs

Information

Disclosure

(e.g., EPA fuel

economy label)

On Products

or Shelf labels

In Ads

Seal of

Approval

Report

Card

Single

Attribute

Certification

2

This report builds on the Status Report on the Use of Environmental Labels Worldwide (EPA Document

#742-R-9-93-001) by updating findings and documenting changes.

3

Gaining more prominence in the past few years is the environmental certification of certain service

industries such as hotels. Issues such as water conservation and energy efficiency are among the environmental

attributes most frequently evaluated. For ease of presentation, the term “products” will be used throughout the

Introduction

1

Environmental Labeling Issues, Policies, and Practices Worldwide

1. Introduction

This research is part of the EPA’s overall effort to educate and inform product users about the

environmental attributes and consequences of products they purchase. It documents the state of

environmental labeling worldwide and provides a basis for anticipating trends.

2

This report

focuses on environmental labeling efforts aimed specifically at retail consumers; however, many

of the labeling activities and programs covered have non-retail applications. The findings are

expected to educate and inform those who may be directly affected (e.g., environmental policy

makers, product manufacturers, organizations/governments making large purchases of consumer

products) or indirectly affected (e.g., trade officials) by environmental labeling programs on the

operation and development of environmental labeling programs. This report should also advance

the debate about the utility of environmental labeling programs.

The term “environmental labeling” covers a broad range of activities from business-to-business

transfers of product-specific environmental information to environmental labeling in retail

markets. Labels, as well as other labeling program activities, serve a variety of purposes and

target a number of different audiences.

At one end of the spectrum, business-to-business environmental labeling includes activities such

as the provision of Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDSs), product stewardship programs, hazard

communication programs, and product manifests. All of these activities are meant either to

provide industrial customers and workers with information on the health, safety, and

environmental effects of the products they purchase or to encourage them to use these products in

ways that minimize their eventual impact on human health and the environment. At the other

end of the spectrum, environmental labeling programs have been established worldwide to help

consumers evaluate the environmental attributes of the products and services they are considering

buying. In this case, the term “consumer” is not limited to private citizens but includes

governments and large institutions seeking to incorporate environmental considerations into their

procurement processes.

One goal of such programs, typically, is to promote environmental improvement by encouraging

consumers to choose products and services considered to be environmentally preferable.

3

report to refer to products and services.

Introduction

2

Related information dissemination activities include, but are not limited to, the Environmental

Protection Agency’s (EPA) Consumer Labeling Initiative (CLI), the Environmentally Preferable

Procurement (EPP) Program and other numerous product labeling programs, the International

Organization for Standardization’s (ISO) efforts to develop standardized environmental labeling

criteria, and the Federal Trade Commission’s (FTC) guidelines for making environmental claims.

Additionally, there are information disclosure activities among U.S. state programs. For

example, the state of California’s Proposition 65 program mandates that information on a set of

listed toxics be disclosed on product labels. Similarly, Vermont’s Household Hazardous

Products Shelf Labeling Program requires retailers to place a label on store shelves that stock

household products containing hazardous materials. These types of programs do not lead to

product labeling per se, but provide consumers with added information about the products they

purchase.

Information concerning the health and environmental effects of products and product constituents

is currently available through a number of pathways, of which labeling is just one. Much of this

information is already generated by manufacturers and is available at various stages of product

manufacture. For some but not all products, environmental information may be passed on to

retail customers (see Chart 1-1).

Manufacture

and Distribution

Point of

Purchase

Use Disposal

Raw

Materials

Environmental

Information

Finished

products

Used

products

Manufacturers/

retailers

Consumers

Reprocessing

For example, the Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSHA) requires manufacturers to

generate an MSDS that includes a description of the product’s physical and chemical properties,

as well as its health, fire, and explosion hazards. MSDSs must be provided to workers, industrial

customers (e.g.., formulators and distributors) and Local Emergency Planning Committees.

Introduction

3

Warning information is required by the US Department of Transportation (DOT) during

interstate transport of hazardous materials such as explosives, flammables, radioactive materials,

and pathogens. Many of the chemical manufacturing, formulating, and distributing sectors have

adopted the tenets of product stewardship. Companies practicing product stewardship take a

“cradle-to-grave” approach to their products by encouraging the safe use and disposal of their

products after they have been sold to industrial customers. Product stewardship can take the

form of voluntary services offered to customers in the form of brochures, training videos, and site

audits, as well as mandatory requirements that determine whether or not the company will sell or

ship to a specific company. The Chemical Manufacturers Association’s Responsible Care

Program is one example of a product stewardship program. These information dissemination

activities serve different purposes and typically, neither reach the general public, nor are

organized into a format that would be readily understandable by consumers. With the current

increase in consumer right-to-know initiatives, particularly in the US, and interest in its uses as a

soft policy tool, the demand for environmental labeling has been increasing.

The type of information presented on labels varies widely, depending on issues specific to the

product and whether labeling is mandatory or voluntary. For example, products subject to the

Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA) requirements must carry labels that

list the active ingredients in the product, first aid statements, environmental, physical and

chemical hazards, directions for use, and instructions for storage and disposal. Other products

may carry voluntary labels specific only to environmental attributes such as the percent of post-

consumer recycled content of the product or its packaging. Note that these examples all describe

characteristics of the product during use or disposal: some labels may also present information

about the manufacture of the product. For example, categories like resource consumption,

energy use, pollutant releases to the environment, and workplace and ecosystem effects may be

addressed.

Environmental labels provide an opportunity to inform consumers about product characteristics

that may not be readily apparent. For example, it may be unsuitable to pour unused cleaning

product down the drain, due to the product’s potential aquatic toxicity. Additionally, labels allow

consumers to make comparisons among products. Armed with this information, consumers have

the ability to reduce the environmental impacts of their daily activities by purchasing

environmentally preferable products and minimizing their consequences during use and disposal.

Labels help consumers vote their preferences in the marketplace and therefore potentially shift

the market toward products that minimize environmental impacts. Label information helps

consumers to use safely and properly recycle or dispose of both products and packaging.

The purpose of this report is to provide an overview and analysis of environmental labeling

programs worldwide. Chapter 2 provides an overview of environmental labeling from the

perspective of the United States. The chapter sets out some important background issues,

history, and definitions, all of which are critical to understanding the development of

environmental labeling to date, as well the future outlook for US programs. Chapter 3 describes

Introduction

4

the types of environmental labeling programs, including specific definitions of program types.

Chapter 4 presents an overview of environmental labeling programs worldwide. Topics covered

include program breadth, methodology, recent changes, and coordination with other programs.

Summary statistics are also provided. In Chapter 5, the forces affecting environmental labeling

programs, such as public/societal interests, consumer interests, retailer’s interests, producer’s

interests, operating costs/profits, standardization, and procurement programs are discussed.

Chapter 6 discusses recent program changes and possible future trends. Finally, Appendix A

summarizes the labeling programs covered in this report, and Appendix B provides detailed

program summaries. The findings and summaries contained herein are based on a number of

efforts that provide complementary research, including EPA's direct experience with

environmental labeling and labeling programs, EPA's involvement in related governmental

initiatives, literature reviews and investigations into labeling and program administration, and

EPA's coordination with domestic and international programs.

4

“G-7" consists of Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, USA, and the UK.

Environmental Labeling: The US Perspective

5

2. Environmental Labeling: The US Perspective

2.1. Background

In all of the seven major industrialized nations (the “G7"), continual efforts have been made to

compile environmental performance information specific to a wide range of products and

services.

4

Such information is disseminated to consumers through hundreds of labeling

programs, both governmental and non-governmental. These programs are implemented at

various points throughout the manufacturing process, from raw material extraction to use and

disposal. It is important to note that environmental labeling has practical implications in the

marketplace, where goods and services compete for consumers, as well as public policy

implications for governments, which are typically charged with the protection of environmental

quality -- a “common good” owned collectively by society. Labeling in the US is no longer

separable from labeling activities in foreign countries, such as ecolabeling programs, nor from

international activities, such as the International Organization for Standardization (ISO)14000

standard-setting process. Thus, the scope of this report focuses on US programs, yet includes

active foreign “ecolabeling” programs.

In simple terms, environmental labeling is defined as making relevant environmental information

available to the appropriate consumers. Environmental labeling is the practice of labeling

products based on a wide range of environmental considerations (e.g., hazard warnings, certified

marketing claims, and information disclosure labels). Labeling contributes to the

decision-making process inherent in product selection, purchasing, use and disposal, or

retirement. Yet unlike most regulations that affect the behavior or actions of a limited number of

entities (e.g., facilities or companies), labeling is designed to influence all consumers. In this

context, the definition of “consumers” encompasses all individuals and organizations making

purchase decisions regarding products and services, ranging from procurement officers of

governments and corporations to individual retail consumers. Environmental labeling often also

affects manufacturers and marketers as they design and formulate products that must compete

based on quality, price, availability and, to varying degrees, environmental attributes.

Current initiatives to harmonize programs worldwide and to establish labeling standards

recognize the diversity among the many types of environmental labels and the many programs

now active. Some programs highlight just a single attribute of a product, such as the recycled

fiber content of paper; others examine multiple attributes. Some programs, such as those

developing automobile fuel economy labels, are neutral (i.e., they make no comparisons among

similar products), while other programs attempt to identify environmentally preferable products

for the consumer. Some, such as the US Environmental Protection Agency's (EPA's) pesticide

labeling program, establish mandatory requirements (typically issued by the government as part

Environmental Labeling: The US Perspective

6

of statutory requirements), whereas other programs are operated by independent third parties and

are typically voluntary. Another form of labeling includes self-declarations made by

manufacturers. While many programs target the retail consumer, programs such as EPA's

Environmentally Preferable Products (EPP) program target institutional decision-makers, e.g.,

federal procurement officials.

Each of these labeling and program characteristics is closely related to the underlying

methodologies used to evaluate the products' environmental attributes. The most comprehensive

methodologies examine a product's entire life cycle, from material extraction, through

production, to use and disposal. Whereas there is no single established standard, life cycle

approaches are the most commonly used by labeling programs. Life-cycle approaches are usually

adopted due to the difficulty of selecting a small set of attributes to represent what are in fact

complex site-specific environmental consequences. Some programs, however, such as the US

Energy Star program, assess products on a life-cycle approach but look primarily at a single

characteristic of whether products meet energy-efficiency criteria.

Whereas much debate exists surrounding what constitutes an optimal program, and what

information and format are most useful to those making purchase decisions, all such efforts

contribute to the generation and dissemination of environmental information in the marketplace.

Furthermore, the increased amount of information regarding environmental attributes and

performance affects manufacturers upstream by pressuring them to take environmental attributes

into consideration when designing or manufacturing their products. Overall, the combined effect

is greater availability and use of such information in the US and in other marketplaces throughout

the world.

2.2. Environmental Labeling in the US

Much of the current research on environmental labeling programs focuses on the emerging third-

party environmental labeling programs. (Third-party labeling programs use an independent

source for their verification process.) Most of these programs are designed to either identify

environmentally superior products or to inventory the products' environmental impact or burden

categories (so that consumers can make such determinations themselves). While such programs

exist in the US and many foreign markets, they do not and cannot represent the full spectrum of

environmental labeling. In the US, such programs are relatively new compared to third-party

environmental labeling programs in other countries, which are typically run by governments.

Furthermore, there are tremendous differences among the missions of US programs. The

existing US government programs often exist to implement specific requirements of statutes or

regulations. For example, to be effective, hazard/warning labels typically are mandatory, and

usually only governmental authorities have the power to impose such requirements on all

products in the marketplace.

5

All of these efforts involve research efforts, some of which resulted in published reports, such as the

Status Report on the Use of Environmental Labels Worldwide, The Use of Life Cycle Assessment in Environmental

Labeling, and Determinants of Effectiveness for Environmental Certification and Labeling Program.

Environmental Labeling: The US Perspective

7

From a domestic perspective, environmental labeling in the US encompasses over 20 programs.

In addition to the governmental warning labeling programs mentioned above, there are also:

< federal government programs dealing with disseminating relative performance

information, such as the Energy Guide;

< governmental and private programs establishing performance or attribute standards and

collecting information for decision-makers, although not necessarily involved in point-of-

purchase labeling;

< private third-party programs, issuing both neutral and positive labels;

< environmental marketing claims made by manufacturers and marketers with guidance

issued by the Federal Trade Commission; and

< federal, state, and local hazard warning programs.

Taken collectively, the labeling activities and coverage (re: product categories) of these programs

play a substantive role in the US marketplace. The fact that US labeling is dispersed among

many different programs requires greater attention to coordination, particularly during bilateral or

multilateral harmonization and negotiations.

Since the creation of the Pesticide Labeling Program in 1947, EPA and its prior organizational

entities have been involved in product evaluation and the administration of an environmental

labeling program. Today, EPA is involved in 13 such programs, ranging from warning labels

under the Toxic Substances and Control Act to the development of standards, used in the

Agency's own Green Buildings and Energy Star programs and life cycle research for selected

products and processes. (A full list of these programs is presented in Chapter 4.) EPA is also

involved in other governmental programs, such as the Energy Guide for appliances, which is

administered jointly with the Department of Energy.

5

Finally, EPA has contact in some form

with almost all environmental labeling programs, both foreign and domestic. Such contact

ranges from intermittent briefings and discussions, to exchanges of technical information used in

developing standards to joint participation in International Organization for Standardization

(ISO) activities.

Environmental labeling in the US marketplace is both active and wide-ranging. Consequently,

the model of a single centralized labeling program does not fit the US experience, nor is it

warranted, given the number of longstanding programs in existence and lack of a (federal)

mandate to consolidate such activities. Summary information and the interrelationships among

environmental labeling programs, both US and foreign, are examined in detail in the following

chapters.

6

Verification refers to the process by which an assessment and/or verification determines that products and

services meet specified criteria or claims.

7

Attributes refer to certain unique characteristics of the product.

Definition of Environmental Labeling

9

3. Definition of Environmental Labeling

Labeling programs can be classified according to a number of program characteristics (see Chart

3-1). One of the most important is whether or not the program relies on first-party or third-party

verification.

6

The former is performed by marketers on their own behalf to promote the positive

environmental attributes of their products.

7

Programs relying on first-party verification are not

addressed in this report. Third-party verification is carried out by an independent source that

awards labels to products based on certain environmental criteria or standards. Environmental

labeling programs can also be characterized as positive, negative, or neutral. Positive labeling

programs typically certify that labeled products possess one or more environmentally preferable

attributes. Negative labeling warns consumers about the harmful or hazardous ingredients

contained in the labeled products. Neutral labeling programs simply summarize environmental

information about products that can be interpreted by consumers as part of their purchasing

decisions. Third-party environmental labeling programs can be further classified as either

mandatory or voluntary. Mandatory programs include hazard or warning labels, and information

disclosure labels. Voluntary labels are typically positive or neutral, and are further classified as

either report cards, seal-of-approval, or single-attribute certification programs. A classification

of each type of positive, negative, and neutral labeling program is presented on the following

page.

10

Chart 3-1: Classification of Environmental Labeling

Environmental Labeling

First-Party

Environmental Labeling Programs

Third-Party

Environmental Labeling Programs

Corporate-RelatedProduct-Related Mandatory Voluntary

Cause-Related

Marketing

(e.g., “Proceeds

donated to...”)

Claims

(e.g., Recyclable)

Promotion of

Corporate Env.

Activity or

Performance

Cause-Related

Marketing

(e.g., Company

supports WWF)

Hazard or

Warning

(e.g., Pesticides,

Prop. 65)

Environmental

Certification

Programs

Information

Disclosure

(e.g., EPA fuel

economy label)

On Products

or Shelf labels

In Ads

Seal of

Approval

Report

Card

Single

Attribute

Certification

Definition of Environmental Labeling

11

3.1. Positive Labeling Programs

Third-party verification programs are typically voluntary in nature and identify positive or

neutral environmental aspects of a product. Labeling programs focusing on the positive

attributes of a product are divided into two types: seal-of-approval (the most common) and

single-attribute certification programs. They are described below.

Seal-of-Approval Programs

Seal-of-approval programs award or license the use of a logo to products that the program judges

to be less environmentally harmful than comparable products, based on a specific set of award

criteria. The operation of each such program differs slightly, but in general they follow a three-

step process: product category definition, development of award criteria, and product evaluation.

First, product categories are chosen. These categories can generally be suggested by either

manufacturers or program officials. Once a product category has been decided upon, criteria are

set for receiving a label within that category.

These criteria are usually based on some form of life-cycle consideration, (not necessarily a full

life-cycle analysis (LCA)). There is usually a public review of program decisions. After criteria

are set, applications are received, candidate products are evaluated, and awards are granted. In

general, criteria are reviewed about every three years, and contracts have to be renewed. The

review process is designed to provide for a continuous tightening of award criteria, such that only

a small percentage of products will qualify for the label, thus providing an incentive for all other

product manufacturers to improve the environmental attributes of their products. It is a complex

task requiring the consideration of many factors, including environmental policy goals, consumer

awareness of environmental issues, trade positioning, effects on imports and exports, and

economic effects on domestic industry. Well-known seal-of-approval programs include

Germany’s Blue Angel, Canada’s Eco-logo, and the US’s Green Seal.

Seal-of-approval programs tend to have similar administrative structures. In a typical program,

the government’s environmental agency is involved to some extent. In some situations a

government agency administers the program; in others they simply provide informal advice or

funding. The bulk of the responsibility rests with a central decision-making board typically

composed of academics and scientists, business and trade representatives, consumer groups,

environmental groups, and government representatives. Technical expertise is provided by the

government, standards-setting organizations, consultants, expert panels, and/or ad hoc task forces

established to work on specific product categories.

Single-attribute Certification Programs

Single-attribute certification programs certify that claims made for a single-attribute of a product

meet a specified definition. Such programs define specific terms such as “recycled” or

“biodegradable” and accept applications from marketers for verification that their product

attribute meet the program definition. If the programs verify that the product attributes meets

their definitions, the program awards the use of the logo to the marketer. The primary single

Definition of Environmental Labeling

12

certification program in the US is the Scientific Certification System’s (SCS) Single Claim

Attribute Certification. Alternatively, programs can set definitions of claims and manufacturers

must meet these requirements. This is the case with the US Energy Star program, which sets

stringent energy-efficient standards that products must meet before being awarded the “Energy

Star.”

3.2. Negative Labeling Programs

Hazard/Warning Labels

Hazard or warning labels are mandatory labels that appear on certain products containing

potentially harmful or hazardous ingredients. The purpose of such labels is to point out the

negative characteristics of the product clearly and encourage the safe use of potentially hazardous

products. Hazard or warning labels are typically mandatory programs that are initiated by a

third-party (e.g., a government agency), which require that information be disclosed to consumers

for health and safety reasons. Alternatively, manufacturers may voluntarily provide

hazard/warning information on their products for liability purposes.

Well known hazard/warning labels in the US include pesticide labeling under FIFRA, which

provides important warnings and advice for users; the Surgeon General’s warnings on cigarettes;

and the skull and crossbones label on poisons. Warning labels specific to health hazards include

the State of California’s Proposition 65 (see Program Summary Appendix for greater detail),

which requires chemicals known to cause cancer or developmental or reproductive toxicity to be

listed by the governor. Warnings must also be provided by businesses for a number of specific

reasons, which include intentional exposure of individuals to these listed chemicals at significant

levels.

Proponents of such disclosure warning labels claim that manufacturers will remove the offending

chemicals rather than suffer the market setbacks (e.g., adverse publicity and loss of market share)

that a hazard/warning label might cause. They argue that this approach provides a stronger

incentive to reformulate products (to avoid hazardous ingredients) than would a voluntary

environmental certification program. If true, the results/benefits of such an approach would be

more certain to cause marketplace shifts.

Definition of Environmental Labeling

13

3.3. Neutral Labeling Programs

Information Disclosure Programs

Unlike hazard/warning labels, which identify negative attributes, information disclosure

programs are neutral. That is, the label contains summary facts that can then be used by

consumers in making their purchasing decisions. One important requirement of information

disclosure programs is that information needs to be simplified and comparable across products.

Since the facts disclosed are not always positive selling features and may not otherwise be

reported by marketers, information disclosure programs are usually mandatory. Unlike

hazard/warning labels, which usually are mandated for health and safety reasons, information

disclosure labels are developed because the program believes that consumers have the “right to

know” about the product.

Perhaps the best known information disclosure label is the US Food and Drug Administration’s

(FDA) nutrition label. The food label must appear on most processed food sold in the US;

labeling of unprocessed fruits and vegetables is voluntary. Examples of environmental

information disclosure labels include the automobile Fuel Economy Information Program and the

Energy Guide program. The Fuel Economy Information Program is an EPA/Department of

Energy (DOE) initiative; the Energy Guide is an EPA initiative. The automobile Fuel Economy

Information Program requires that a label listing the mileage rating be affixed to all new cars and

trucks sold. Begun as a voluntary program in 1973, it soon became mandatory for auto makers to

report the mileage rating of new vehicles. The Energy Guide program requires that a label

disclosing energy consumption per year or an energy efficiency rating be affixed to certain

household appliances, such as refrigerators, refrigerator-freezers, freezers, water heaters, clothes

washers, dishwashers, furnaces, room air conditioners, central air conditioners, and heat pumps.

An interesting hybrid of the information disclosure label is the battery labeling program. This

program, administered by the EPA Office of Solid Waste, requires that a label appear on certain

batteries and rechargeable consumer products, stating the chemical name (nickel-cadmium or

lead) and the phrase "BATTERY MUST BE RECYCLED OR DISPOSED OF PROPERLY."

While this type of labeling is mandatory and presents neutral information (the chemical name), it

also notifies users/consumers of their legal obligation to dispose of the product properly.

Report Cards

The report card label, one type of information disclosure label, uses a standardized format to

categorize and quantify various impacts/burdens that a product has on the environment. Specific

and consistent information (for example, pounds of air emissions) is presented on the label,

allowing a comparison across categories. By providing the consumer with standardized detailed

information and little interpretation, the report card allows consumers to make judgments based

on their particular environmental concerns.

In the US, Scientific Certification Systems (SCS) has prepared an eco-profile that can be applied

Definition of Environmental Labeling

14

to any product category. These eco-profiles are based on a life-cycle assessment (LCA), which is

the first step in the more comprehensive Life Cycle Stressor Effects Assessment (LCSEA). The

SCS eco-profile evaluation is a multi-step process involving the identification and quantification

of inputs and outputs for every stage of a product’s life cycle including raw materials extraction,

material processing, manufacturing, distribution, use, and disposal. Based on the assessment,

three claims of achievement may be certified:

< certified environmental state-of-the-art,

< certified environmental improvements, and

< certified environmental advantages.

Overview of Labeling Programs Worldwide

15

4. Overview of Labeling Programs Worldwide

4.1. Introduction

This chapter provides an overview of a variety of different types of labeling programs in the US,

and primarily voluntary, seal-of-approval, programs in other countries. The majority of the

overseas programs covered in this report are government- or quasi-government-run programs.

Typically, there is one such national (voluntary) labeling program in each country. In contrast,

the US, lacking such a national labeling program, has a variety of different types of programs in

operation. The US programs covered in this report include mandatory government programs,

voluntary seal-of-approval programs, single-attribute programs, hazard warnings programs, and

information disclosure programs. Charts are provided throughout this chapter to illustrate the

discussion; often, these charts are used to show the difference between the programs in the US

and the rest of the world.

Due to the scope of this report, not every labeling program that may be in existence today is

covered (e.g., food is not covered), and the report should not be seen as a comprehensive study of

all labeling programs worldwide. The report presents a “snapshot” of the major environmental

labeling programs in existence during the research phase and for which information was

available. Unless otherwise noted, the charts in this section include all programs surveyed as

part of this report.

Section 4.2 provides some fundamental information about labeling programs, such as label and

program type, how programs are administered and financed, and changes to programs over the

years. Section 4.3 includes several maps that show the geographic distribution of the labeling

programs covered in this report. Section 4.4 provides an overview of the reasons environmental

labeling programs are initiated, as well as the methodologies used by each program to establish

product categories and award criteria. A discussion of the ways in which environmental labeling

is being used today, either for procurement purposes or in trade, is given in Section 4.5. Section

4.6 provides a brief discussion of the changes that have occurred in labeling programs. Finally,

Section 4.7 describes the efforts countries are making to coordinate their environmental labeling

programs with each other.

4.2. Fundamental Information

This section helps to define the basics of existing environmental labeling programs by

summarizing information and characteristics fundamental to each environmental labeling

program. Characteristics discussed include program and label type, program administration,

financing, and age, as well as number or range of product categories and awards. It should be

noted that certain program characteristics are frequently linked. For example, programs

identifying negative product attributes are, by necessity, mandatory. Furthermore, mandatory

Overview of Labeling Programs Worldwide

16

programs are typically administered by governments, since environmental regulations may

provide them with the authority to require mandatory labeling. In the case of the State of

California’s Proposition 65, considered to be a hazard warning program, businesses that

knowingly expose individuals to any of a list of chemicals are required to provide a warning of

such exposure. Most seal-of-approval programs, however, are third-party and voluntary. As

their name implies, such programs award labels for (relative) positive environmental attributes.

For a listing of the programs covered in this report, refer to the overview table in Appendix A.

For detailed summaries of the programs contacted and included in this report, refer to the reports

in Appendix B.

Program Type

The programs reviewed issue one of three kinds of labels: positive, negative, or neutral. Most of

the programs discussed in this report award positive labels indicating to the consumer that the

environmental attributes of the labeled product in some way outperforms the environmental

attributes of other similar products. Certification of the positive environmental attributes of a

product provides manufacturers with an incentive to apply for an environmental label in the

hopes of capturing more market share and improving corporate goodwill.

Negative labels, on the other hand, are typically required by law and are used to present the

hazards associated with use and disposal of the product. For example, Vermont’s Household

Hazardous Product Shelf Labeling Program requires all retailers stocking household products

containing hazardous constituents to identify those products via a shelf label. Given that most

regulations establish guidance only, mandatory labeling programs require a statement of fact, and

do not necessarily result in a comparable labeling format or information across products. In

addition, differing requirements across jurisdictions for mandates that are not updated to reflect

the current state of the economy can result in clutter on the label and/or higher labeling costs for

marketers.

Neutral labels, such as the US Energy Guide, simply report summary facts about the product and

allow consumers to make their own judgments based on their particular concerns. Such labels

can also provide information for manufacturers and others who may use the information for

internal use (e.g., benchmarking studies). The container’s size, however, may dictate how much

neutral label information can be included.

Overview of Labeling Programs Worldwide

17

As shown in the following chart, there is an fairly even split in the number of positive, negative,

and neutral US programs covered in this report. As mentioned above, however, the majority of

other countries’ programs covered in this report are positive programs, reflecting the fact that

most of these are seal-of-approval programs (see Chart 4-1).

Chart 4-1: Program Type

(based on programs reviewed)

Program

Positive NeutralNegative

US

9

Outside

US

31

US

5

Outside

US

0

US

7

Outside

US

2

Overview of Labeling Programs Worldwide

18

Participation

Participation in labeling programs can be either mandatory or voluntary. This report includes

voluntary programs worldwide and mandatory and voluntary programs in the US; due to the

scope of this report, not every existing program was surveyed. Of the programs surveyed, most

are voluntary (this is exclusively so for the programs outside the US). US programs covered in

this report are fairly evenly split between mandatory and voluntary programs (see Chart 4-2).

Chart 4-2: Participation in Labeling Programs

(based on programs reviewed)

Participation

Mandatory Voluntary

US

8

Outside

US

0

US

12

Outside

US

31

With voluntary programs, manufacturers choose to participate in a program and typically submit

an application for a specific product to be labeled. To encourage manufacturers to participate,

emphasis is placed on the positive attributes of a product. Because these programs are propelled

by their market influence, manufacturers apply for a label when it increases their product’s

marketability as well as their competitive edge.

Mandatory programs, on the other hand, can require the identification of negative product

characteristics, and are typically one element of a regulatory approach to consumer and

environmental protection. For example, the US battery labeling requirements mandate that

rechargeable cadmium and/or lead batteries carry labels that inform users of the contents of the

batteries and indicate that batteries must be recycled and/or properly disposed. Whether or not a

program is mandatory or voluntary will influence the extent and type of information about

environmental attributes on labels in the marketplace. Typically, mandatory programs result in

more comprehensive dissemination of information in the marketplace, since all similar products

are required to carry a label.

Overview of Labeling Programs Worldwide

19

Label Type

The types of labels awarded by programs fall into the following categories: seal-of-approval,

single-attribute, hazard warning, information disclosure, and report card. Most programs