USC Information Sciences Institute

Networks shape behavior and perceptions

USC Information Sciences Institute

Networks shape behavior and perceptions

1. Networks shape behavior: form the substrate for social

interactions and information flow.

2. Your friends are a small subset of the population.

3. Friends are not a random sample of the population.

4. This distorts your perceptions. (A rare trait can appear

very popular)

USC Information Sciences Institute

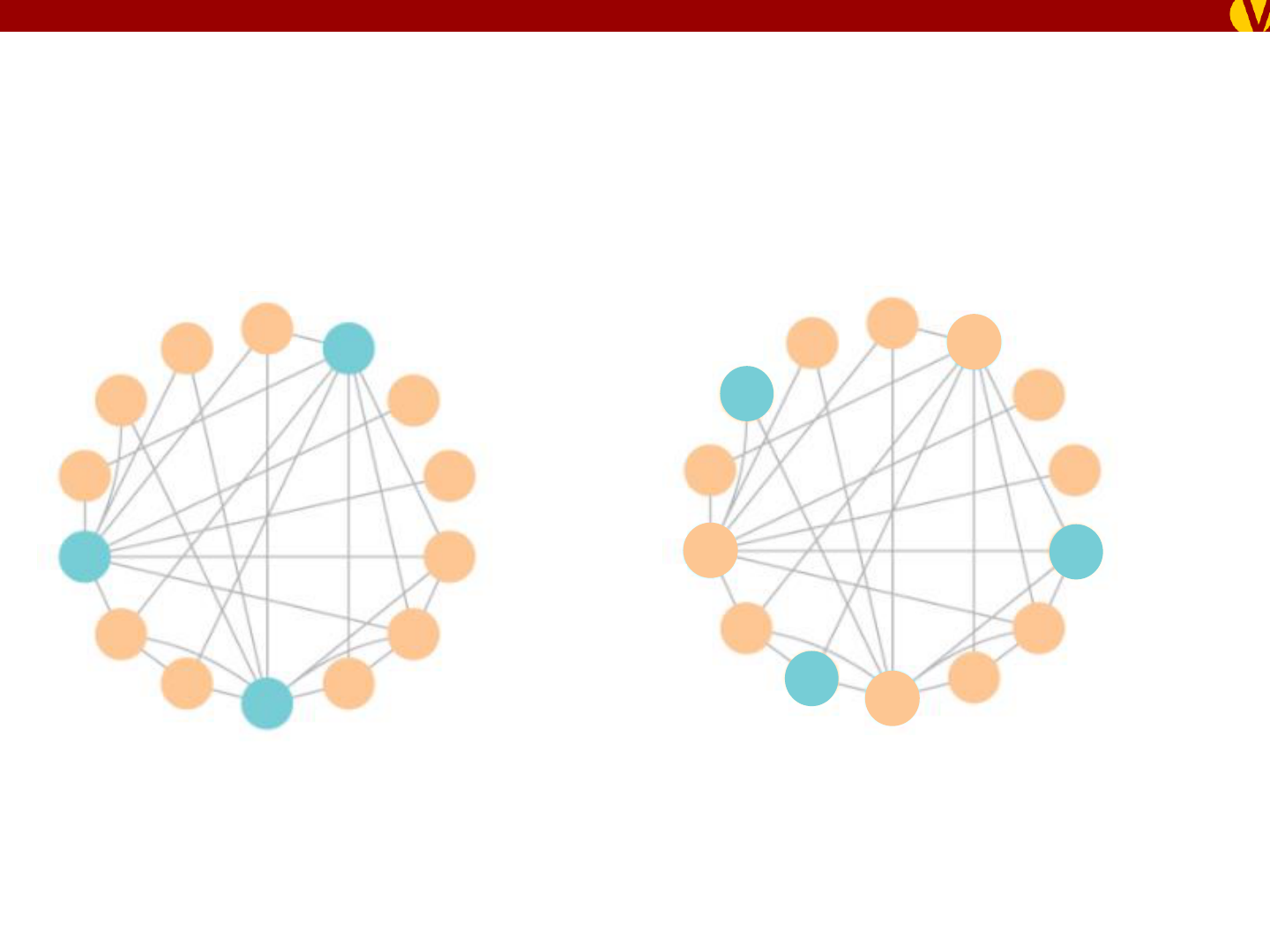

What color is more popular?

USC Information Sciences Institute

What color is more popular?

Nodes think yellow is

more Blue is not

especially popular

Most nodes think blue is

popular

USC Information Sciences Institute

Local vs global views

K. Schaul, “A quick puzzle to tell whether you know

what people are thinking”, Wonkblog, Washington

Post

https://www.washingtonpost.com /graphics/business/wonkblog/ma

jority-illusion/

USC Information Sciences Institute

Networks distort local information

• Networks can systematically bias individual

perceptions of what is common among peers

• Example: College students overestimate peers’ alcohol use

Source: Most Students Do PartySafe@Cal

How many alcoholic drinks are consumed at a party

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

None 1-2

drinks

3-4

drinks

5-6

drinks

7+

drinks

Myself

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

None 1-2

drinks

3-4

drinks

5-6

drinks

7+

drinks

My Friends

USC Information Sciences Institute

Outline

Friendship paradox

• The many friendship paradoxes in networks

• Origins of paradoxes: a network science view

Perception bias

• Friendship paradox in directed networks

• … biases perceptions of popularity

• Twitter case study: Some hashtags appear more

popular than they are

Polling

• Estimate global popularity with perception bias

• … with a limited budget

USC Information Sciences Institute

Lots of paradoxes!

Friendship paradox

You friends have more friends than

you do, on average [Feld, 1991]

USC Information Sciences Institute

Lots of paradoxes!

Friendship paradox

You friends have more friends than

you do, on average [Feld, 1991]

Generalized friendship paradox

You friends are more X than you are,

on average [Hodas et al., 2013, Eom

& Jo, 2014]

USC Information Sciences Institute

Lots of paradoxes!

Strong friendship paradox

Most of your friends have more friends

than you do [Kooti et al., 2014]

Friendship paradox

You friends have more friends than

you do, on average [Feld, 1991]

Generalized friendship paradox

You friends are more X than you are,

on average [Hodas et al., 2013, Eom

& Jo, 2014]

USC Information Sciences Institute

Lots of paradoxes!

Strong friendship paradox

Most of your friends have more friends

than you do [Kooti et al., 2014]

Generalized strong friendship

Most of your friends are more X than

you are [Kooti et al, 2014]

Majority illusion

Most of your friends have a trait, even

when it is rare. [Lerman et al, 2016]

Friendship paradox

You friends have more friends than

you do, on average [Feld, 1991]

Generalized friendship paradox

You friends are more X than you are,

on average [Hodas et al., 2013, Eom

& Jo, 2014]

USC Information Sciences Institute

How common is strong friendship paradox?

Network

Type

Nodes

Probability of

paradox

LiveJournal

Social

3,997,962

84

Twitter

Social

780,000

98

Skitter

Internet

1,696,415

89

Google

Hyperlink

875,713

77

ProsperLoan

Social Finance

89,269

88

ArXiv

Citation

34,546

79

WordNet

Semantic

146,005

75

Very common… almost everyone observes that most of their

friends are more popular

USC Information Sciences Institute

Twitter Digg

0

50

100

%

u

s

e

rs

mean median

Twitter Digg

0

50

100

%

u

s

e

rs

But wait, there is more

Twitter Digg

0

50

100

%

u

s

e

rs

mean median

[Kooti, et al (2014) “Network Weirdness: Exploring the origins of network paradoxes” in ICWSM]

Activity

You post less than

most of your

friends

Diversity

You see less diverse

content than

most of your

friends

Virality

You see less viral

content than

most of your

friends

USC Information Sciences Institute

Why?

Strong friendship paradox

Most of your friends have more friends

than you do [Kooti et al., 2014]

Generalized strong friendship

Most of your friends are more X than

you are [Kooti et al, 2014]

Majority illusion

Most of your friends have a trait, even

when it is rare. [Lerman et al, 2016]

Friendship paradox

You friends have more friends than

you do, on average [Feld, 1991]

Generalized friendship paradox

You friends are more X than you are,

on average [Hodas et al., 2013, Eom

& Jo, 2014]

USC Information Sciences Institute

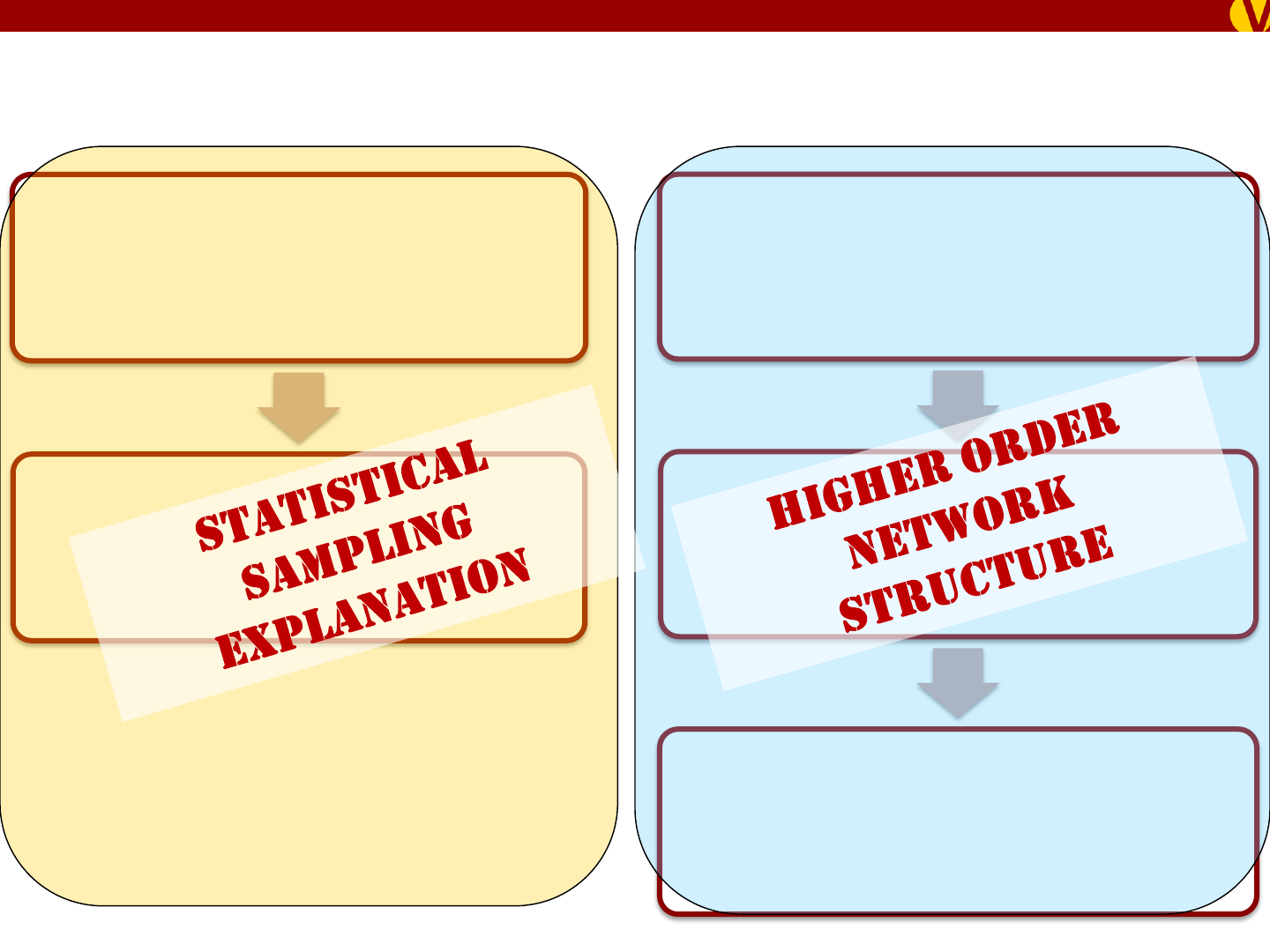

Different explanations

Strong friendship paradox

Most of your friends have more friends

than you do [Kooti et al., 2014]

Generalized strong friendship

Most of your friends are more X than

you are [Kooti et al, 2014]

Majority illusion

Most of your friends have a trait, even

when it is rare. [Lerman et al, 2016]

Friendship paradox

You friends have more friends than

you do, on average [Feld, 1991]

Generalized friendship paradox

You friends are more X than you are,

on average [Hodas et al., 2013, Eom

& Jo, 2014]

USC Information Sciences Institute

Friendship paradox as a byproduct of sampling

from a heterogeneous distribution

10

0

10

2

10

4

10

−6

10

−4

10

−2

10

0

# posted tweets (log binned)

P

D

F

your value x

your friends’ values

x

1

, …, x

k

x

USC Information Sciences Institute

Friendship paradox as a byproduct of sampling

from a heterogeneous distribution

10

0

10

2

10

4

10

−6

10

−4

10

−2

10

0

# posted tweets (log binned)

P

D

F

your value x

your friends’ values

x

1

, …, x

k

Sample mean grows with k

x

USC Information Sciences Institute

USC Information Sciences Institute

Strong friendship paradox is a network effect

• To explain strong friendship paradox, need to account

for network structure

• Building blocks of network structure

• dK series framework represents network structure as the joint degree distribution of

subgraphs of up to d nodes

P. Mahadevan, D. Krioukov et. al., ACM SIGCOMM Comp. Comm. Rev. 36 135–

146 (2006)

• Node degree distribution

First-order structure (1K)

• Pair degree distribution

Second-order structure (2K)

• Triplet degree distribution

Third-order structure (3K)

USC Information Sciences Institute

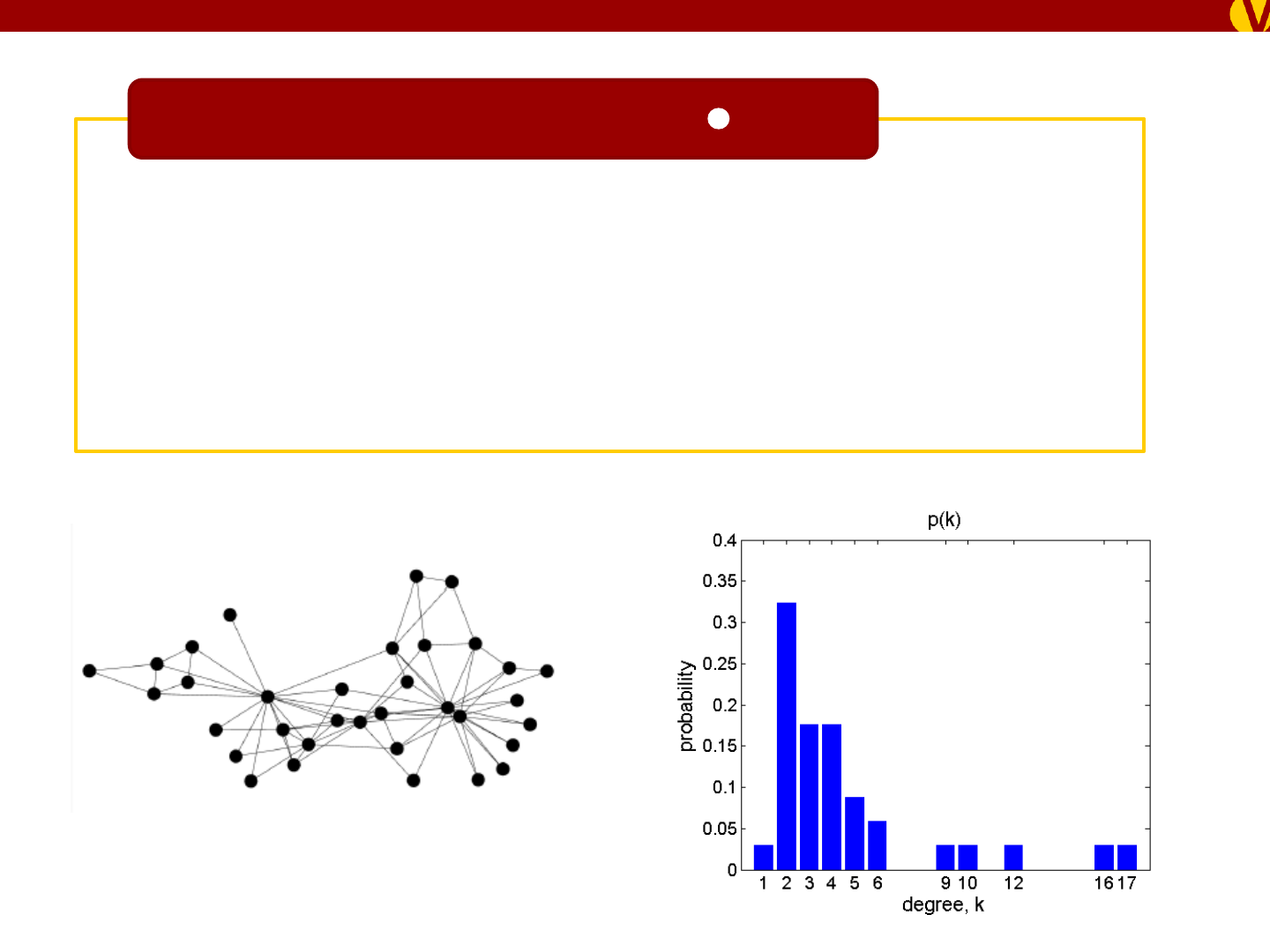

• Node degree distribution p(k)

• Probability that a randomly selected node has

degree k.

• Any heterogeneous degree distribution (variance >

0) will lead to a (weak) friendship paradox

First-order (1K) structure

USC Information Sciences Institute

• Neighbor degree distribution q(k)~kp(k)

• Probability that a randomly selected neighbor

has degree k.

• Any heterogeneous degree distribution (variance >

0) will lead to a (weak) friendship paradox

First-order (1K) structure

USC Information Sciences Institute

Digg social network

USC Information Sciences Institute

disassortative assortative

• … Nodes do not link at random

• Joint degree distribution of connected pairs of

nodes e(k,k’)

• Probability that a randomly selected edge links

nodes with degrees k and k’.

• Degree assortativity r

2k

• MEJ Newman, Assortative Mixing in Networks, Phys Rev Lett 89

208701 (2002)

Second-order (2K) structure

USC Information Sciences Institute

negative

neighbor assortativity

original network

• … nodes do not link to random neighbors

• Neighbor assortativity: neighbors tend to have

similar (or dissimilar) degrees, r

3k

• Networks can have the same 1K and 2K structure but

different 3K structure

• Wu, Percus & Lerman, Neighbor Degree Assortativity in Networks, in

preparation

Third-order (3K) structure

positive

neighbor assortativity

USC Information Sciences Institute

Real-world networks have third-order structure

Degree correlations among node’s neighbors in real-world

networks are often large

USC Information Sciences Institute

Third-order structure enhances paradoxes

Neighbors’ degrees are

not correlated*

Neighbors’ degrees are

correlated*

*same 1K and 2K structure

USC Information Sciences Institute

Third-order structure enhances paradoxes

Neighbors’ degrees are

not correlated*

Neighbors’ degrees are

correlated*

*same 1K and 2K structure

USC Information Sciences Institute

84%

89%

77%

88%

79%

75%

Fraction of degree-k nodes experiencing the paradox

in real-world networks • ;

predictions of the 2K model · · · and the 3K model —.

[Wu et al (2017) “Neighbor-neighbor correlations explain measurement bias in networks”

Scientific Reports 7]

USC Information Sciences Institute

From friendship paradox to “majority Illusion”

Nodes have a binary trait: active/not, yellow/blue,

heavy drinker/teetotaler, …

Blue does not appear

common

Many think that blue is

common

[Lerman, Wu & Yan (2016) The “Majority Illusion” in Social Networks, in Plos One.]

USC Information Sciences Institute

Network structure amplifies majority illusion

More nodes will think that blue is very

common when:

• Higher degree nodes are more likely to be

blue: degree-trait (k-x) correlation

• High degree nodes link to low degree nodes:

degree disassorativity (r

2k

<0)

• Neighbors tend to have similar degree:

neighbor assortativity (r

3k

>0)

[Lerman, Wu & Yan (2016) The “Majority Illusion” in Social Networks, in Plos One.]

USC Information Sciences Institute

Network structure amplifies majority illusion

[Lerman, Wu & Yan (2016) The “Majority Illusion” in Social Networks, in Plos One.]

Fraction of nodes experiencing the majority illusion in a

synthetic network with 0.5% active nodes;

USC Information Sciences Institute

Friendship paradox in directed networks

user

friends

followers

in-degree

out-degree

USC Information Sciences Institute

Friendship paradox in directed networks

user

friends

followers

friends-of-friends

followers-of-followers

friends-of-

followers

followers-

of-friends

USC Information Sciences Institute

Probability a node experiences a paradox

friends have more followers followers have more friends

followers have more followers friends have more friends

USC Information Sciences Institute

Local perception bias

• Popularity of a (binary) attribute: probability a random

node v has value f(v)

• Local perception of node v about popularity of an

attribute f is the fraction of her friends with attribute

• Local perception bias: nodes perceive the attribute f to

more popular than it actually is

USC Information Sciences Institute

Global popularity vs local perception on Twitter

Twitter data

• Time period

• Summer 2014

• Network

• 5K users + tweets

• Their 600K friends + tweets

• Hashtags

• 18M hashtags

• Focus on 1K most popular

hashtags, used by >1K

people

Compare perceived popularity

of hashtags to their actual

popularity

USC Information Sciences Institute

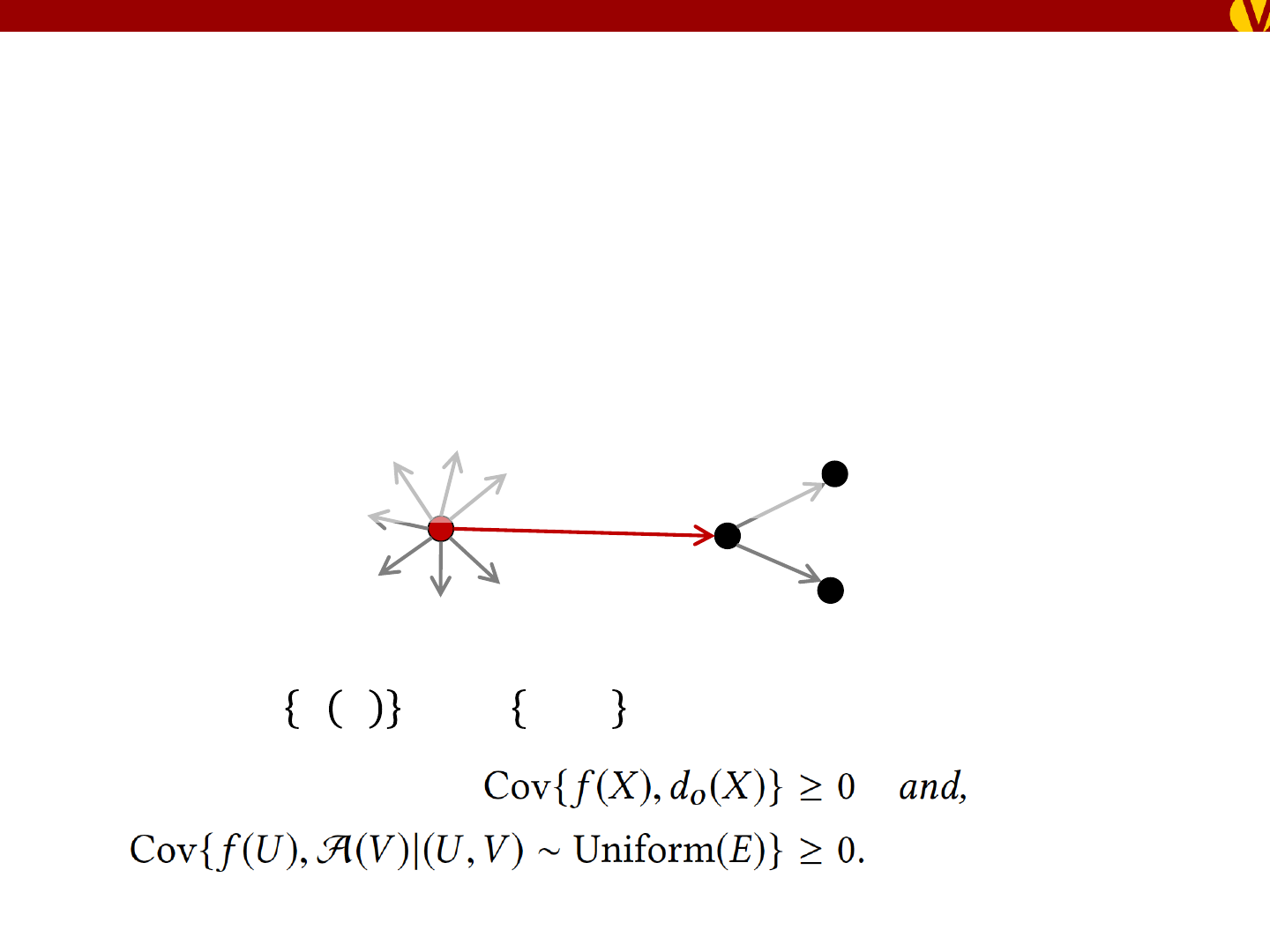

Conditions for local perception bias

Local bias exists if:

• Higher out-degree (high influence) tend to have the attribute.

• Lower in-degree nodes (high attention) tend to follow nodes with

attribute.

Theorem: ( ) if

U

V

high

influence

high

attention

USC Information Sciences Institute

Polling

USC Information Sciences Institute

What is the right question to ask in a poll?

Estimate the true prevalence of an attribute through polls

• Estimate the fraction of liberals vs conservatives, heavy

drinkers vs teetotalers, people who used a hashtag vs not, …

• …with limited budged b

Polling:

1. Intent Polling (IP): [b random nodes] Will you vote for X?

2. Node Perception Polling (NPP): [b random nodes] What

fraction of your friends will vote for X?

3. Follower Perception Polling (FPP): [b random followers]

What fraction of your friends will vote for X?

• aggregates perceptions of more people

USC Information Sciences Institute

Bias & variance of FPP

• Bias of the polling estimate (error) T

• Variance is bounded by

l

2

, second largest eigenvalue

of the symmetrized adjacency matrix of the network

• Mean squared error of the polling estimate T:

USC Information Sciences Institute

FPP polling algorithm is more efficient

When used to estimate the true popularity of Twitter hashtags, FPP

has lower variance and MSE.

For a given budget, i.e., number of nodes sampled, it outperforms

other polling methods on many hashtags.

USC Information Sciences Institute

To summarize

• Network structure can systematically bias local

perceptions

• Making a rare attribute appear far more common than it is,

under some conditions

• Open questions: What is the impact of network bias on

• Collective dynamics in networks, e.g., contagious outbreaks

• Network control and intervention

• Psychological well-being

• Your friends are happier that you are (Bollen et al. 2016)

• Your co-authors are more prestigious than you are (Eom & Jo 2014)

• Social comparison theory

USC Information Sciences Institute

THANK YOU!

Sponsors

NSF: CIF-1217605

ARO: W911NF-16-1-0306

Questions?