COVID: Family Law and Real Property Law Issues

Employment Law’s Legislation Evolution

A High Flying Judge Discusses Judicial Demeanor

Lawyer Well-being in a Pandemic

e General Practice Issue

VOL. 69/NO. 1 • June 2020

VIRGINIA LAWYER REGISTER

Virginia Lawyer

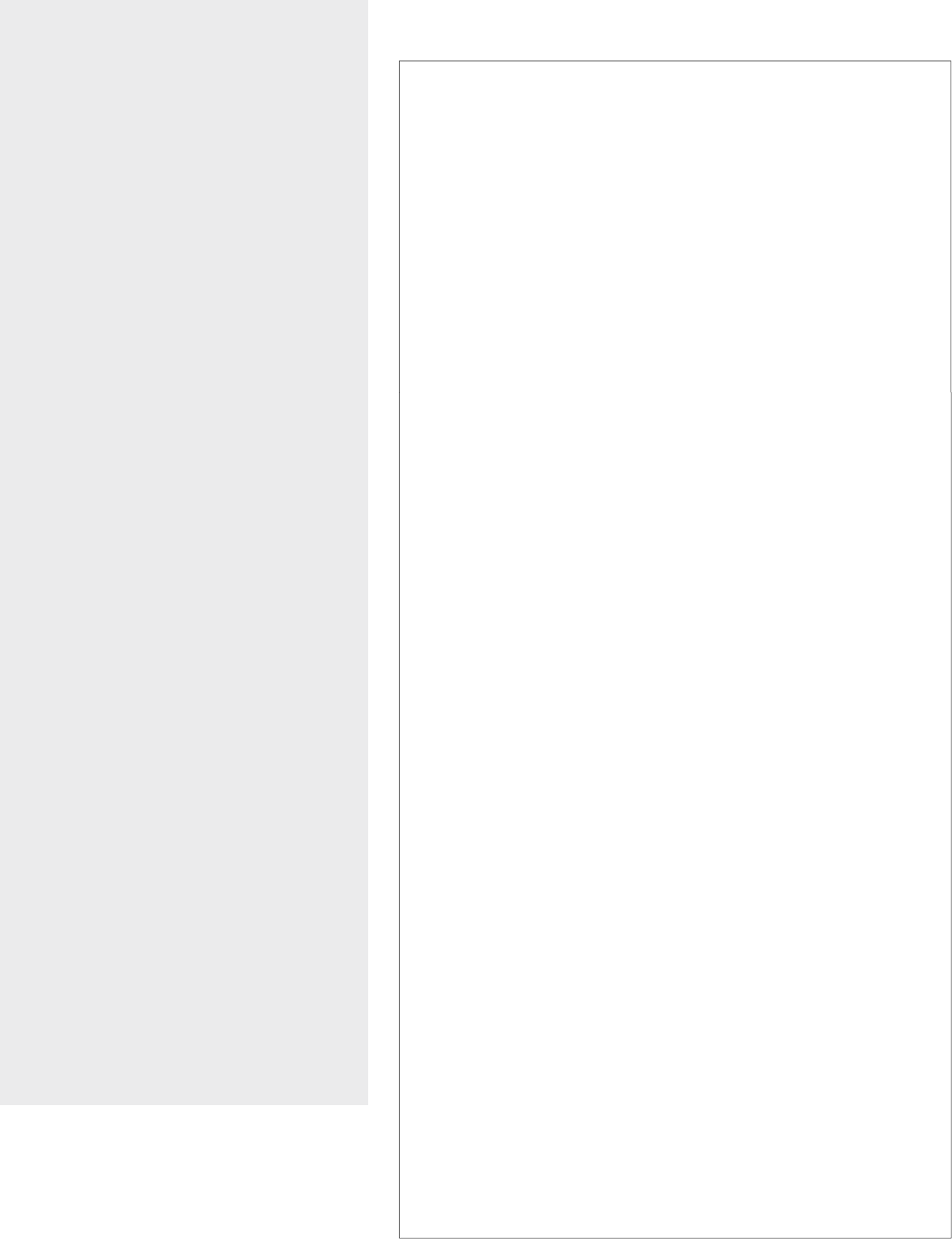

Meet 2020–21 VSB President Brian L. Buniva

The Ofcial Publication of the Virginia State Bar

Virginia Lawyer

The Ofcial Publication of the Virginia State Bar

June 2020

Volume 69/Number 1

Features

VIRGINIA LAWYER REGISTER

55 Disciplinary Summaries

56 Disciplinary Proceedings

57 Notices: A Roundup of News from vsb.org

58 Clients Protection Fund Reimburses $30,659 to Clients

6 Forum

59 Professional Notices

61 Classied Ads

61 Advertiser’s Index

Noteworthy

VSB NEWS

38 Highlights of the June 9,

2020, Virginia State Bar

Executive Committee

Meeting

38 Dues Statements Mailed:

What’s New is Year?

39 Jay B. Myerson will

be VSB President for

2021–22

40 Bar Welcomes New

Council Members and

Conference Leadership

42 Of Cats, Dogs, and

Defense Attorneys:

e Indigent Criminal

Defense Seminar Goes

Virtual

43 2020 Edition of Senior

Virginians Handbook

Available

44 In Memoriam

45 Awards

Cover: VSB President Brian Buniva with his wife, Barbara Cochrane Buniva, and their families. Photo by Deirdre Norman. Post production by Sky Noir Photography.

Departments

10 President’s Message

12 Executive Director’s Message

14 Ethics Counsel’s Message

50 Law Libraries

51 Technology and the Future Practice

of Law

52 Risk Management

62 e Last Word

Columns

15 General Practice: COVID-19 Impacts our Clients, Committees, and Us

by Christopher C. Johnson

16 Family Law: From Mayhem to Mindfulness In (Almost) Post-Pandemic

Virginia

by Bretta Z. Lewis

18 Practice Points: ree Tips for Responding to a Subpoena Duces Tecum

by Lindsay Reimschussel

20 2020 Legislative Session Heralds a Sea Change in Virginia

Employment Law

by Jason Zuckerman and Dallas Hammer

24 Virginia Real Estate in the Time of COVID

by Benjamin D. Leigh

26 Behaving Judiciously: e Importance of

Judicial Demeanor

by the Honorable Steven C. Frucci

30 Taking the Law into Your Own Hands: Private Criminal Complaints in

Virginia

by Henry H. Perritt, Jr.

GENERAL PRACTICE

34 A ank You Note to All Virginia Lawyers

by Margaret Hannapel Ogden

35 A Lawyer’s Story of Recovery: First Step to Full Circle

by Asha Pandya

37 e Lawyers’ Lighthouse: e Growth of VJLAP

by Tim Carroll

WELLNESS

8 First You Have to Make the Team, en You Get to Change

the Game

by Deirdre Norman

2020–21 VSB PRESIDENT BRIAN L. BUNIVA

VIRGINIA LAWYER | June 2020 | Vol. 69

4

www.vsb.org

Virginia State Bar Sta Directory

Frequently requested bar contact

information is available online at

www.vsb.org/site/about/bar-sta.

www.vsb.org

Editor:

Deirdre Norman

Creative Director:

Caryn B. Persinger

Assistant Editor:

Kaylin Bowen

Advertising: LLM Publications

Grandt Manseld

VIRGINIA LAWYER (USPS 660-120, ISSN 0899-9473)

is published six times a year by the Virginia State Bar,

1111 East Main Street, Suite 700, Richmond, Virginia

23219-0026; Telephone: (804) 775-0500. Subscription

Rates: $18.00 per year for non-members. is material

is presented with the understanding that the publisher

and the authors do not render any legal, accounting,

or other professional service. It is intended for use by

attorneys licensed to practice law in Virginia. Because of

the rapidly changing nature of the law, information

contained in this publication may become outdated. As

a result, an attorney using this material must always

research original sources of authority and update

information to ensure accuracy when dealing with

a specic client’s legal matters. In no event will the

authors, the reviewers, or the publisher be liable for

any direct, indirect, or consequential damages resulting

from the use of this material. e views expressed herein

are not necessarily those of the Virginia State Bar. e

inclusion of an advertisement herein does not include

an endorsement by the Virginia State Bar of the goods

or services of the advertiser, unless explicitly stated

otherwise. Periodical postage paid at Richmond,

Virginia, and other oces.

POSTMASTER:

Send address changes to

VIRGINIA LAWYER

MEMBERSHIP DEPARTMENT

1111 E MAIN ST STE 700

RICHMOND VA 23219-0026

Virginia Lawyer

The Ofcial Publication of the Virginia State Bar

2020–21 OFFICERS

Brian L. Buniva, President

Jay B. Myerson, President-elect

Marni E. Byrum, Immediate Past President

Karen A. Gould, Executive Director and

Chief Operating Ocer

EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE

Brian L. Buniva, President

Jay B. Myerson, President-elect

Marni E. Byrum, Immediate Past President

Eugene M. Elliott, Roanoke

Stephanie E. Grana, Richmond

Chidi I. James, Fairfax

Eva N. Juncker, Falls Church

William M. Moet, Abingdon

Eric M. Page, Richmond

CONFERENCE CHAIRS AND PRESIDENT

Conference of Local and Specialty Bar

Associations – Susan N. G. Rager, Coles Point

Diversity – Sheila M. Costin, Alexandria

Senior Lawyers – Margaret A. Nelson,

Lynchburg

Young Lawyers – Melissa Y. York, Richmond

COUNCIL

1st Circuit

Damian J. (D.J.) Hansen, Chesapeake

2nd Circuit

Ryan G. Ferguson, Virginia Beach

Jerey B. Sodoma, Virginia Beach

Bretta Z. Lewis, Virginia Beach

3rd Circuit

Meredith B. Travers, Portsmouth

4th Circuit

Ann B. Brogan, Norfolk

Gary A. Bryant, Norfolk

Neil S. Lowenstein, Norfolk

5th Circuit

omas G. Shaia, Suolk

6th Circuit

J. Daniel Vinson, Emporia

7th Circuit

Benjamin M. Mason, Newport News

8th Circuit

Marqueta N. Tyson, Hampton

9th Circuit

Susan B. Tarley, Williamsburg

10th Circuit

E. M. Wright Jr., Buckingham

11th Circuit

Shaun R. Huband, Petersburg

12th Circuit

P. George Eliades II, Chester

13th Circuit

Dabney J. Carr IV, Richmond

Leah A. Darron, Richmond

Eric M. Page, Richmond

Cullen D. Seltzer, Richmond

Sushella Varky, Richmond

Neil S. Talegaonkar, Richmond

Henry I. Willett III, Richmond

14th Circuit

Craig B. Davis, Richmond

Stephanie E. Grana, Richmond

Marissa D. Mitchell, Henrico

15th Circuit

Allen F. Bareford, Fredericksburg

16th Circuit

R. Lee Livingston, Charlottesville

Palma E. Pustilnik, Charlottesville

17th Circuit

Adam D. Elfenbein, Arlington

Jennifer S. Golden, Arlington

Gregory T. Hunter, Arlington

Joshua D. Katcher, Arlington

William H. Miller, Arlington

18th Circuit

Barbara S. Anderson, Alexandria

Stacey Rose Harris, Alexandria

John K. Zwerling, Alexandria

19th Circuit

Susan M. Butler, Fairfax

Brian C. Drummond, Fairfax

David J. Gogal, Fairfax

Sandra L. Havrilak, Fairfax

Chidi I. James, Fairfax

Douglas R. Kay, Tysons Corner

Daniel B. Krisky, Fairfax

Christie A. Leary, Fairfax

David L. Marks, Fairfax

Nathan J. Olson, Fairfax

Luis A. Perez, Falls Church

Susan M. Pesner, Tysons Corner

Wayne G. Travell, Tysons

Michael M. York, Reston

20th Circuit

R. Penn Bain, Leesburg

Susan F. Pierce, Warrenton

21st Circuit

G. Andy Hall, Martinsville

22nd Circuit

Eric H. Ferguson, Rocky Mount

23rd Circuit

Eugene M. Elliott Jr., Roanoke

K. Brett Marston, Roanoke

24th Circuit

Eugene N. Butler, Lynchburg

25th Circuit

William T. Wilson, Covington

26th Circuit

Nancy M. Reed, Luray

27th Circuit

R. Cord Hall, Christiansburg

28th Circuit

William M. Moet, Abingdon

29th Circuit

D. Greg Baker, Clintwood

30th Circuit

Greg D. Edwards, Jonesville

31st Circuit

Maryse C. Allen, Prince William

MEMBERS AT LARGE

Denise W. Bland, Eastville

Atiqua Hashem, Richmond

Eva N. Juncker, Falls Church

B. Alan McGraw, Tazewell

Lenard T. Myers, Jr., Norfolk

Lonnie D. Nunley, III, Richmond

Patricia E. Smith, Abingdon

Lisa A. Wilson, Arlington

Vac ancy

Virginia State Bar

VIRGINIA LAWYER | April 2020 | Vol. 68

6

www.vsb.org

Forum

In response to “How to Succeed

as In-House Counsel” by Kelly C.

Scanlon:

Ms. Scanlon’s advice for in-house coun-

sel is spot-on. Although unspoken in

her article, each of those tips for success

is part of a larger theme: Strategy.

is theme is most clearly reect-

ed in her statement that “[i]n-house

lawyers are . . . one part of a much

bigger whole.” Just as in-house counsel

must understand their role in assisting

organizational strategy, they must view

their own legal duties through a strate-

gic lens. For the in-house practitioner,

mere tactics won’t suce, because each

piece of advice, each training delivered

(or not), each memorandum, and yes,

each settlement, creates organizational

precedent that will shape the behaviors

of each unit. ose behaviors either

contribute to or mitigate the aggregate

risk to the organization.

It takes time and eort to lay the

groundwork for this long-term ap-

proach but doing so can lend extra

credibility to in-house counsel’s advice,

even when unpopular. As organizations

make dicult choices to weather, and

recover from, the economic impact of

COVID-19, strategic guidance of in-

house counsel will be vital.

James omas Koebel

Associate General Counsel, University

of North Carolina Wilmington

Jest Is For All by Arnie Glick

Letters

Send your letter to the editor to:

Virginia State Bar

Virginia Lawyer Magazine

1111 E Main St., Suite 700

Richmond, VA 23219-0026

Letters published in Virginia Lawyer

may be edited for length and clarity

and are subject to guidelines

available at www.vsb.org/site/

publications/valawyer/.

Got an Ethics Question?

e VSB Ethics Hotline is a condential consultation service for Virginia lawyers.

Questions can be submitted to the hotline by calling (804) 775-0564 or by clicking on

the “Email Your Ethics Question” link on the Ethics Questions and Opinions web page

at www.vsb.org/site/regulation/ethics/.

VIRGINIA LAWYER | June 2020 | Vol. 69

8

www.vsb.org

2020–21 VSB President

“I expect to be great. I expect to do

what hasn’t been done. I expect to

provoke change.”

— Deion Sanders

IN FOOTBALL, THE CORNERBACK

is oen described as the most athletic

player on the eld: they must be fast,

tough, able to read and react to what’s

happening in a split second. Yet, they

are rarely famous. With the exception

of Deion Sanders, these versatile defen-

sive players don’t get the attention that

quarterbacks and wide receivers receive.

Ironically, the new Virginia State Bar

President, Brian L. Buniva, of Richmond,

not only played cornerback for three of

his four years at Georgetown University,

but he was inducted into his new role

as president of the 50,000 member VSB

with zero fanfare: a small gathering in

the Supreme Court of Virginia court-

room instead of the traditional banquet

for 300 people at the Annual Meeting in

Virginia Beach. His induction celebra-

tion was a casualty, like so many things,

of the COVID-19 pandemic that has

gripped the country since mid-March.

Of his missed celebration Buniva

said graciously, “I feel more disappoint-

ment for my predecessor, Marni Byrum,

than myself. Marni deserves the fanfare

and appreciation of her colleagues for

her many years of service to our profes-

sion, including this last year as the 81st

President of the VSB.”

But back to football: Buniva, who

is sturdy, yet hardly football player size,

was so small as a child that he stued

his pockets with bar bell weights to

make the 80 lb. cut o for his rst foot-

ball team, placing him on the eld with

players up to 130 lbs. He started o

determined, and from that inglorious

beginning, Buniva went on to play for

his undefeated high school football team

in Tenay, New Jersey, which won the

state football championship of 1967.

As a result of his eorts, Buniva was

inducted into the Tenay High School

Athletic Hall of Fame in 2019, following

in the footsteps of his father, Edo “Bull”

Buniva, who was inducted posthumously

nearly 30 years earlier.

Both sets of Buniva’s grandparents

arrived in America through Ellis Island,

his mother’s family from Ireland and his

father’s from Italy. His story has some of

the hallmarks of many immigrant fam-

ilies: his grandparents came here in the

1900s seeking a better life, and Buniva is

the rst member of his nuclear family to

graduate from college and then become a

lawyer. Today, his son Nathan, Nathan’s

wife Sylvia O’Brien Buniva, and Buniva’s

stepdaughter-in-law, Amanda Weaver,

all have law degrees. He is equally proud

of his daughter, Emily Buniva Edelson,

a doctor of psychology at Children’s

Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), and

his son-in-law, Jonathan Edelson, a pedi-

atric cardiologist on the pediatric heart

transplant team at CHOP.

Buniva considered attending the

United States Military Academy at

West Point, where his family oen took

Sunday drives, and quickly adopted as

his own the West Point motto: “Duty,

Honor, Country.” His poor eyesight

prevented that, and he landed at

Georgetown where he not only played

football, but became interested in the

politics that infuse Washington, D.C.

Aer a few years working in the

political arena, Buniva made his way to

Richmond and eventually attended the

University of Richmond Law School.

He said he chose the law because, “I

knew I wanted to be of service and

at the end of my life, to know that it

mattered that I had spent time on this

earth. Ultimately, I decided upon a

life in the law which has allowed me to

advance the West Point ideals of Duty

(Commitment to Principle); Honor

(Integrity); and Country (with Justice

for All).”

Buniva chose environmental law,

largely because of the environmental

movement that came of age in the 1970s

and 1980s with the passage of numer-

ous federal and state laws designed to

protect and preserve the environment.

His rst position as a lawyer was in

the Virginia government, serving as

Assistant Attorney General assigned to

the Health and Environmental Sections

in the Attorney General’s Oce. He later

transitioned to private practice, but has

remained focused on environmental and

First You Have to Make the Team, en You Get to

Change the Game

by Deirdre Norman

Vol. 69 | June 2020 | VIRGINIA LAWYER

9

www.vsb.org

2020–21 VSB President

land use issues for the span of his 40+

year legal career.

Buniva’s bar service is not surpris-

ing, in light of his commitment to duty,

and over the years he has volunteered

extensively for the Virginia State Bar, the

American Bar Association, the Virginia

Bar Association, and the Richmond

Bar Association, eventually chairing

the VSB, VBA, and RBA sections of

Administrative and Environmental Law.

He was one of the earliest volunteers

for Lawyers Helping Lawyers (now the

Judges and Lawyers Assistance Program)

and chaired the Central Virginia com-

mittee. He has also been elected to VSB

Council, serving from 2007 to 2013 and

again from 2015 to the present.

In his free time, Buniva unwinds

by boating on the James River, mak-

ing homemade ravioli, and by spoiling

the nine grandchildren who call him

“Papi.” In 2015, Buniva married his wife,

Barbara Cochrane Buniva, aer propos-

ing to her on the Jumbotron at Fenway

Park in Boston. Today, they enjoy a

Buniva continued on page 11

1: Brian as a child on his rst football team in New Jersey.

2: Brian asking his wife, Barbara Cochrane, to marry him

on the jumbotron at Fenway Park.

3: Aboard his boat,

Never Look Back

, with one of his

grandchildren.

4: The Bunivas at their 2015 wedding.

5: With nine grandchildren, Brian Buniva knows how to

hold a baby.

1

2

3 4

5

VIRGINIA LAWYER | June 2020 | Vol. 69

10

www.vsb.org

President’s Message

by Brian L. Buniva

I ,

my rst as the 82nd President of the

Virginia State Bar, on Good Friday,

two days aer Passover, and two weeks

before the beginning of Ramadan.

ese three major observances of the

Christian, Jewish, and Muslim faiths

all have in common the belief that we

are here on this earth to be of service

to our individual communities and to

the world. Our noble profession shares

these values. Indeed, the preamble

to our Virginia Rules of Professional

Conduct states in relevant part:

As a public citizen, a lawyer

should seek improvement of the

law, the administration of justice

and the quality of service rendered

by the legal profession. . . . A law-

yer should be mindful of decien-

cies in the administration of justice

and of the fact that the poor, and

sometimes persons who are not

poor, cannot aord adequate legal

assistance, and should therefore

devote professional time and civic

inuence in their behalf. A lawyer

should aid the legal profession

in pursuing these objectives and

should help the bar regulate itself

in the public interest.

How do we lawyers meet the aspira-

tional goals of our profession?

By the time this column is pub-

lished we will either still be under the

Governor’s Executive Orders to com-

bat the spread of the Covid-19 virus,

or we will have begun to emerge from

such restrictions in our pre-pandemic

routines. We will emerge painfully

aware of what we have lost. Many of

us have suered economic loss, loss of

social interactions, loss of family activ-

ities, loss of professional opportunities,

loss of the VSB Annual Meeting, and

most sadly some of us have lost one

or more loved ones to this pandemic

scourge.

But as Virginia Supreme Court

Justice Mims recently wrote in the May

26th edition of the Richmond Times

Dispatch, we might not just ponder

what the Covid-19 pandemic has taken

from us, but perhaps more importantly

we might reect on what the pandemic

has given to us?

My answer is that the pandemic

has given me the gi of time. Time to

enable me to focus on what is truly

important in my life as an individual

and as a lawyer. It has given me the

time to reect upon the life and loss of

my mother, a probable victim of this

pandemic. It has given me the oppor-

tunity to reect upon and cherish my

wife, and the ability to simply hug fam-

ily and friends. But the pandemic has

also given me the unique opportunity

to reect upon priorities and reorder

what is important and what is less

important as I embark on this year as

VSB President.

We all know that the mission

of the VSB is to protect the public,

regulate the legal profession, assist in

improving the legal profession and the

judicial system, and to advance access

to legal services. e Bar is blessed with

an impressive cadre of sta and self-

less volunteers focusing on all four of

these missions, but if we can rally the

members of the Bar around the goal

of advancing access to legal services

for the poor and Virginians of modest

means, we will indeed have used the

gi of time and reection wisely. e

predominant theme and focus of my

year as president will be to do just that.

Shortly you will receive your VSB

dues statement for Bar year 2020 to

2021. Included with your statement

will be a form asking you to voluntarily

report the number of pro bono hours

and/or nancial contributions you

have made consistent with Rule 6.1 of

the Rules of Professional Conduct. Rule

6.1 establishes the aspirational goal that

every lawyer should render at least two

percent per year of the lawyer’s profes-

sional time to pro bono legal services.

By voluntarily reporting your service

you will provide the bar with the infor-

mation necessary to measure our col-

lective performance in achieving this

aspirational goal and provide informa-

tion to the Supreme Court’s Access to

Justice Commission in support of its

work promoting equal access to justice

for all Virginians.

Last year, the rst year the vol-

untary reporting rule was in eect,

13.5% of the active members of the

VSB reported nearly 369,000 hours

of pro bono service and nearly $1

million in nancial contributions

to legal aid societies throughout our

Commonwealth. I believe that these

numbers at a minimum can be doubled

by the end of my term in June 2021.

Please support this eort and complete

the voluntary report. Please aspire

to achieve the goals of Rule 6.1. And

nally, please use your position as law-

yers and community leaders to assist

those less fortunate among us in clos-

ing the justice gap and receiving their

rightful opportunity for equal access to

justice.

God bless all of you for your service.

Compassionate Service in a Time of

Human Suering

Vol. 69 | June 2020 | VIRGINIA LAWYER

11

www.vsb.org

large, blended family, spending their

free time at their beach house in Corolla,

North Carolina, and travelling together.

Raised as a Catholic, Buniva

has been an active member of the

Midlothian Friends Meeting of the

Religious Society of Friends (Quakers)

for nearly 30 years. ough a relatively

small religious group, the Quakers are

known for their activism, their opposi-

tion to war, and their dedicated ght to

end slavery, starting as early as the late

1600s. Susan B. Anthony, who devoted

her life to ghting for women’s rights

was a Quaker, as was President Herbert

Hoover, who earned global acclaim

for the “Hoover Lunch” program that

sent food and supplies to war ravaged

Europe aer World War I, prior to his

presidency.

ough he oen has a twinkle in

his eye when at VSB meetings, aer

a childhood spent in the rigors of

Catholic school, Buniva comes prepared

to buckle down and be serious as the

2020–21 VSB president. His objectives

are broad and begin with narrowing

the justice gap. He said he will focus his

year as president on:

• encouraging a substantial increase

in the number of pro bono and

low bono hours volunteered by

our colleagues;

• partnering with the Supreme

Court’s Access to Justice

Commission to improve access to

the courts;

• being a voice for the independence

of the judiciary; and

• being of service to local bar asso-

ciations, lawyers, and the public

throughout the Commonwealth.

ough the goals are challenging, and

the obstacles obvious, there is little doubt

Buniva has the mind for the game. From

the 75 lb. weakling who forced his way

onto the local peewee football team, to

the cornerback at Georgetown, to the

rst member of his family to graduate

from college and then law school, to

environmental advocate, to president

of the Virginia State Bar: Buniva has

proven over and over again that if you

want to change the game, the rst step is

getting on the team. q

Buniva continued from page 9

Brian L. Buniva

B. L. Buniva Strategic Advisor, PLLC

Virginia State Bar:

Executive Committee

Bar Council

Administrative Law Section

Environmental Law Section

Budget and Finance

Better Annual Meeting Committee

Bench-Bar Relations

Nominating Committee

Study Committee on the Future of Law Practice

ABA Delegate

President-Elect, Virginia State Bar 2019–2020

Other Bar Admissions and Activities:

Supreme Court of Virginia

United States Court of Appeals for the

Fourth Circuit

United States District Court for the Western and

Eastern Districts of Virginia

United States Supreme Court

Lawyers Helping Lawyers (now Virginia Judges

and Lawyers Assistance Program)

Midlothian Friends Meeting

Boys to Men Mentoring Network

Ten Thousand Villages Fair Trade Store

Former President of Maggie Walker Governors

School Athletic Boosters Club.

Education:

Georgetown University, A.B. Government

The American University, Graduate Studies

in Public Administration

University of Richmond, T.C. Williams School

of Law, (Highest Grade in Criminal Law,

Constitutional Law and Advanced

Constitutional Law)

Family:

Brian is married to Barbara Cochrane and has two

adult children, three adult stepchildren, and nine

(with one on the way) grandchildren.

Left: Brian making homemade ravioli, a skill learned from

his Italian aunt. Right: Brian Buniva in his earlier days as

an environmental lawyer.

VIRGINIA LAWYER | June 2020 | Vol. 69

12

www.vsb.org

Executive Director’s Message

by Karen A. Gould

L- have

been uprooted by the disruptions

caused by the coronavirus pandemic,

and innovation has occurred. One of

our immediate focuses in mid-March

was cancellation of meetings and

events through May. In early April,

the decision was made to cancel the

Annual Meeting set for June 17–20,

2020, in Virginia Beach. is was the

rst time the Annual Meeting has been

canceled since World War II in 1945.

Many other VSB events have been

canceled, including most meetings and

events through August and some in

the fall. Please check the VSB website

for an up-to-date status of an event or

meeting.

At the request of the VSB, the

Supreme Court of Virginia entered

orders extending the dues compli-

ance period from July 31, 2020, to

September 30, 2020. As a public health

precaution, the VSB oce is closed

to the public. Please be advised if you

intend to mail or deliver renewals/

payments to the Virginia State Bar,

deliveries are only accepted from the

following services:USPS, UPS, Fed Ex,

DHL, and Richmond Express. Please

use a trackable express delivery method

if you are sending your renewals/pay-

ments close to the September 30 dead-

line. All renewals must be received by

4:45 p.m. September 30, 2020.

e Supreme Court of Virginia

has also extended the MCLE compli-

ance period until December 31, 2020.

On May 1, 2020, the Supreme

Court of Virginia approved amend-

ments to Part 6, Section IV, Paragraph

3 of the Rules of Court regarding the

organization and government of the

Virginia State Bar. Most notably,

these Rule changes: (1) impose an

email address of record requirement

for all members; (2) create separate

membership classes for retired and

disabled members (with corollary

changes to Paragraph 13-23.K.); (3)

remove the requirement for active

members to be “engaged in the

practice of law;” (4) revise some pro-

cedures for electing dierent mem-

bership classes; and (5) update the

Rule’s language to eliminate ambig-

uous terminology. ese rule changes

were eective June 30, 2020 and were

implemented as part of the 2020–2021

dues renewal.

On the gubernatorial front,

Governor Ralph Northam proposed

and the General Assembly passed at

its Special Session on April 22, 2020,

an amendment to the Freedom of

Information Act to allow public bodies

to meet electronically during the time

of a declared emergency “when it is

impracticable or unsafe to assemble

a quorum in a single location.” is

FOIA amendment will not help lawyers

and law rms in private settings, but

it will certainly assist the lawyers who

serve on VSB committees and boards,

so long as the declaration of an emer-

gency continues.

e Leroy R. Hassell Sr. Indigent

Criminal Defense Live Webinar, pre-

viously done as a live presentation in

Richmond and simulcast to two other

locations, was successfully telecast to

over 1,000 Virginia lawyers on May 1,

2020. e program was a huge success

for several reasons: (1) the vendor,

Yorktel Information Technology &

Service, was facile in switching from a

televised simulcast program to a tele-

cast program in a matter of weeks; (2)

well-regarded speakers from across the

country, who had canceled because

of the coronavirus, were able to give

their presentations safely via this new

modality); and (3) the changes saved

$77,596.

Because of the cancellation of

the usual Admission and Orientation

Ceremony at the Richmond

Convention Ceremony, the Supreme

Court of Virginia conducted its June

swearing-in ceremony of new law-

yers through videoconferencing.

Approximately 200 lawyers were sworn

in by Chief Justice Donald Lemons.

e VSB was unable to give

President Marni E. Byrum a celebra-

tory send-o at the end of her year

as president at the Annual Meeting,

unlike other presidents. e Virginia

State Bar and its 50,000 members owe

her a huge debt of gratitude for the

leadership she has shown this year as

president. As stated in the resolution

honoring her service, Byrum’s leader-

ship as president of the Virginia State

Bar was exemplied by her unwavering

commitment to improving the profes-

sion, to protecting and informing the

public, to service to the VSB’s members

and its committees, and by supporting

the Virginia State Bar sta.

Be sure and read the article

about incoming VSB President Brian

Buniva in this magazine, as well as

his rst column. He would normally

have been sworn in at the President’s

Banquet at the Annual Meeting, but

it was canceled due to the pandemic.

Instead, Buniva was sworn in by Justice

William C. Mims on June 30, 2020, at

the Supreme Court of Virginia.

I hope you, your families, and

your colleagues are healthy and doing

well. As always, I can be reached at

Coronavirus Brings Change to VSB

“Every adversity, every failure and every heartache carries with it the seed of an

equivalent or a greater benet.”

— Napoleon Hill

Vol. 69 | June 2020 | VIRGINIA LAWYER

13

www.vsb.org

Condential help for substance abuse problems and

mental health issues.

For more information, visit https://vjlap.org

or call our toll free number 24/7: 1-877-545-4682

Lawyers Helping Lawyers is now

Virginia Judges and Lawyers Assistance Program

Fastcase is one of the planet’s most

innovative legal research services,

see what you’ve been missing with data

visualization tools.

start your journey

LEARN MORE AT

www.fastcase.com

AI San d b ox

Legal Data Analysi s

Fu l l Court Press

Expert Treat i s e s

Nex tChapter

Bank r u p tcy Petiti o n s + Filing

Docke t Alar m

Pl e a dings + Analytics

Law St r e e t Media

Legal News

Fa s t c a s e

Legal Research

WORLD

DIFFERENCE

A

OF

You’ve Got Mail!

Or you might, if your email address is up to date with

the Virginia State Bar.

Please make sure you are getting our monthly VSB

News and annual compliance messages by adding

[email protected], [email protected], and MCLE@

vsb.org to your email contacts.

And as always: Keep all of your information current

by logging on at www.vsb.org.

NEW: You can opt out of receiving Virginia Lawyer by

mail if you prefer to read it online.

VIRGINIA LAWYER | June 2020 | Vol. 69

14

www.vsb.org

Ethics Counsel

by James M. McCauley

I HBO e Sopranos,

mobster Tony Soprano got ugly with

his estranged wife, Carmela, hold-

ing a consultation with every high-

enddivorce lawyer in northern New

Jersey so that the lawyers would be

conicted in representing her. While

the Soprano story is ction, in LEO

1794, the Ethics Committee was asked

to address an insidious practice called

“blocking” in which one spouse, pre-

paring to divorce the other spouse,

consults successively with several law-

yers in a geographical area not to hire

them, but to rather disqualify the law-

yer from representing the other spouse.

When a prospective client and a

lawyer communicate about possible

representation, there is a “reasonable

expectation of condentiality” even if

no attorney-client relationship ensues.

e lawyer faces disqualication if

hired by a person adverse to the pro-

spective client in the same matter,

i.e., a divorce case. LEO 1546 (1993);

LEO 1642 (1995); Gay v. Luihn Food

Systems, Inc., 5 Cir. CL00121, 54 Va.

Cir. 468, 2001 Va. Cir. LEXIS 24, at

*7 (Va. Cir. Ct. Feb. 7, 2001); Joslyn v.

Joslyn, 23 Cir. CH03596 (December 5,

2003).

In Joslyn, the wife sought to dis-

qualify the husband’s lawyer because

she had an initial interview with that

lawyer but chose to hire a dierent

lawyer before the divorce proceedings

commenced. e husband’s lawyer

argued no attorney-client relationship

had ensued aer the initial consulta-

tion and the wife acknowledged that in

a signed writing before the consult. e

court disqualied the husband’s coun-

sel nding that the written acknowl-

edgment was insucient as it did not

waive the prospective client’s expecta-

tion of condentiality nor did the wife

consent to the lawyer representing the

adverse spouse.

Lawyers have avoided disquali-

cation caused by initial consults by,

among other things, charging a hey

consultation fee, and other measures

such as:

1) Running a conicts check before the

initial consultation;

2) Warning the potential client not to

provide condential information at

that point;

3) Asking whether the potential client

has met with other attorneys;

4) Sending a “non-engagement” letter

if declining the representation; and

5) Anticipating a motion to disqualify

should the opposing party become

a client.

In 2002, the ABA adopted Model

Rule 1.18 to address duties owed to

and conicts created by prospective

clients. Virginia adopted a nearly iden-

tical rule, but not until June 21, 2011.

Before the adoption of Rule 1.18, the

Rules of Professional Conduct did not

address the duties owed to prospective

clients. However, legal ethics opinions

addressed these issues, either treating

the prospective client as analogous to a

former client or holding that the duty

of condentiality applied even if there

was never an attorney-client relation-

ship. In family law cases, the prospec-

tive client typically would not waive

the conict and the consulted lawyer

would be disqualied, even when only

limited information was imparted

during the initial consult.

MR 1.18 and Va. Rule 1.18 are

nearly identical. New guidance from

ABA Formal Opinion 492 (June 9.

2020), is particularly helpful and

important:

1. A “prospective client” is one who

consults or discusses with a lawyer

the possibility of forming an attor-

ney-client relationship.

2. Not every communication a person

interested in obtaining legal services

has with a lawyer makes that person

a prospective client. Formal Op. 492

at 2. See also Comment [2] to Va.

Rule 1.18 (A person who commu-

nicates information unilaterally to

a lawyer, without any reasonable

expectation that the lawyer is willing

to discuss the possibility of forming

a client-lawyer relationship, is not a

“prospective client.”) and LEO 1842

(2008) (lawyer has no duty of con-

dentiality to person who unilaterally

transmits unsolicited information in

voice mail or email).

3. A person who communicates with a

lawyer to disqualify that lawyer is not

a “prospective client.” Bernacki v.

Bernacki, 1 N.Y.S.3d 761, 764 (Sup.

Ct. 2015) (husband in a divorce sent

an email to his wife titled “Attorneys

Which [sic] Whom I Have Sought

Legal Advice” and then listed “twelve

of the most experienced matrimonial

attorneys in the county,” each of

whom the husband asserted “would

conict themselves out” or be sub-

ject to disqualication); Restatement

(3d) of the Law Governing Lawyers

§15 cmt. c (“a tribunal may con-

sider whether the prospective client

disclosed condential information

to the lawyer for the purpose of pre-

venting the lawyer or the lawyer’s

Rule 1.18: You Didn’t Hire Me But Your

Adversary Just Did!

Ethics continued on page 53

GENERAL PRACTICE | Vol. 69 | June 2020 | VIRGINIA LAWYER

15

www.vsb.org

From this time last year, the General Practice

Section of the Virginia State Bar was on track

to have one of its best years in recent times

leading up to the COVID-19 pandemic. e

section successfully put on a fantastic CLE

called “A Day in General Practice,” which was

held October 16, 2019, at the University of

Richmond. e section was set to co-sponsor a

CLE at the Annual Meeting in Virginia Beach

prior to its cancellation. e current state

of the section is that there are a total of 839

section members, which is broken down as

follows: 726 Active/Associate, 97 Judicial, and

16 Other (includes corporate counsel, judicial

retired).

As with many other areas of practice,

general practitioners have felt varying eects

fromthe COVID-19 pandemic, and it is our

hope that we as a board, a section, and a state-

wide bar can be of assistance to those strug-

gling through these hard times. One of the

greatest joys I have felt in the general practice

of law is the ability to provide assistance to

those of all walks of life during dicult times.

is is certainly a dicult time, and

we have seen lawyers stepping up, oen for

no monetary compensation, to help people

with issues ranging from potential evic-

tions to navigating the potential benets of

the CARES Act and other similar stimulus

related programs.

On behalf of the General Practice Section

Board of Governors, I wish everyone the very

best of health and continued security and

prosperity as we move into the second half of

2020. Despite all of the jokes about lawyers,

when times get tough, it is our profession

that is relied on by so many to get them

through. Given the caliber of lawyers we have

in Virginia, as practitioners and as people in

general, I am condent we will overcome this

most recent challenge.

Christopher C. Johnson is a partner in the law rm

ofJohnson&JohnsonAttorneys at Law, P.C., in

Hanover County. A graduate of Virginia Tech and the

Charleston School of Law, Johnson has been a lifelong

resident of Hanover County. He is chair of the VSB

General Practice Section, an active member of his local

community, and president of the Hanover County Bar

Association.

General Practice:

COVID-19 Impacts our Clients,

Committees, and Us

by Christopher C. Johnson

VIRGINIA LAWYER | June 2020 | Vol. 69 | GENERAL PRACTICE

16

www.vsb.org

T COVID- “” with

respect to family law is akin to calling what

happened on the Titanic “a vacation mishap.”

Although not all Virginia lawyers practice

family law, it seems that all of us are, directly

or indirectly, impacted by divorce. Whether it

is your loved one, a neighbor, friend, or your-

self, every person who has been privy to the

turmoil caused by divorce turns to someone

for advice.

Lawyers and mental health profession-

als are the obvious sources for guidance,

and sometimes the line between legal advice

and counseling is blurry (hence the tra-

ditional title “Attorney and Counsellor at

Law). Unfortunately, all Virginia attorneys,

including those who practice family law, are

currently facing a massive breakdown of the

typical way we assist clients due to court clo-

sures and other pandemic response measures.

Although we always aspire to advance our cli-

ents’ interests swily and eciently, this goal

seems all but impossible since the pandemic

closures and restrictions have been enacted.

ere is no way to provide solid advice to cli-

ents without adding the caveat, “Nobody really

knows what is going to happen … I mean,

literally, nobody.” is is new turf for even the

most seasoned professionals and is unprece-

dented in the Commonwealth’s court system.

Ethical rules forbid us from guaranteeing

outcomes to clients, however, in pre-COVID

Virginia, we could at least tell clients when

and where to appear for hearings and advise

them of the possible outcomes. Now, we have

no idea what matters will proceed, what the

timetable will be, or what format to expect.

We have no way to ease our clients’ fears

about their nancial futures or make any reli-

able assessment about the long-term ramica-

tions of the litigation. With each order, each

edict, and each publication from the Executive

and Judicial branches, interpretations of which

seem to dier in each jurisdiction and judi-

cial district, the waters become increasingly

murky.

In the family law realm, not only is uncer-

tainty frustrating and disconcerting, but it can

also be emotionally devastating and, in some

cases, dangerous. Mental health professionals

are concerned about the “layering” eect of

the lack of closure on families. Dr. Robert

Archer, a leading national expert in forensic

psychology and adolescent development,

emphasizes that “Stress is viewed by psychol-

ogists as a cumulative experience,” and that

“e pandemic is making additional demands

on the coping resources of family members.”

e pandemic has multiplied already

existing issues including domestic violence

Family Law: From Mayhem to Mindfulness In

(Almost) Post-Pandemic Virginia

by Bretta Z. Lewis

GENERAL PRACTICE | Vol. 69 | June 2020 | VIRGINIA LAWYER

17

www.vsb.org

FAMILY LAW

and substance abuse, during a time when in-person services

are oen suspended. e pressure cooker created by social iso-

lation, nancial strain, and unprecedented unemployment is

taking an insurmountable toll on families. Some husbands and

wives feel that there is no choice but to separate. is requires

them to divide the remaining resources, including dividing time

with oen stressed-out children.

As responsible, compassionate practitioners, Virginia fam-

ily law attorneys can help. Aer serving as a Guardian Ad Litem

since 2005, I believe that we must rst protect the most vulner-

able participants, the children. We have to nd a way to reach

into the whirlpool and pull them out before they drown in their

parents’ stress. We also need to give our adult clients as much

guidance as possible in solving their problems without waiting

for the overwhelmed courts to provide answers.

With creative, empathetic representation, parties can avoid

the stress of waiting and preparing for trial. Forward-thinking

family lawyers can use new methods to change the norms in

resolving conicts and focus our energy into providing solu-

tions in a revolutionary way. In short, we can become helpers.

is article seeks to shed some light for Virginia lawyers,

both from a place of ideology and practicality. Family lawyers

are facing some tricky questions that are as of yet, unanswer-

able.

(1) How can parents who are separating, divorcing, or already

divorced eectively co-parent and deal with delays, litigation

and indenite continuances?

(2) How can parents eectively implement “distance learning”

and support educational development when they are sepa-

rated, divorced and at odds with the other parent?

(3) How do we best manage child support cases when the

courts are overwhelmed, and parties are facing unemploy-

ment, furloughs, or other loss of income stability?

Generally, for all of these unknowns, it seems that keeping

parties out of court and nding an amicable, exible solution

that can be implemented immediately may be the best practice.

Below are some insights gained in discussions with experts who

deal regularly with families in crisis:

(1) Custody, Visitation and Co-parenting: Parents in the

process of separation and divorce may be feeling hopeless

because pending matters have been continued, nances are

uncertain, they are reeling from the long, stressful litigation

process, and/or because health concerns are exacerbating the

situation. Families may be experiencing new ris in previously

quasi-functional family dynamics due to suocating mandatory

togetherness, while families already in crisis may nd that the

pandemic has created an unbearable tension.

Statistics from crisis hotlines indicate that substance abuse

and domestic violence are escalating as anxiety and frustrations

are fueled by isolation and despair. In some cases, one parent

may be refusing to communicate or cooperate with the other

and the courts are not able to respond quickly. ere are, how-

ever, methods available to assist families to move toward a solu-

tion, even without court intervention.

Instead of waiting for a trial in a divorce or custody case,

attorneys should hold settlement conferences on a exible

schedule, accommodating childcare and other contributing

stressors. Using platforms such as Zoom, WebEx, Microso

Teams, and Google Meetings, responsible and compassionate

attorneys and the Guardian Ad Litem, working together, can

assist parents to move past emotion and encourage them to nd

practical ways to preserve precious resources and protect their

children. Agreements incorporated into court orders can pro-

vide closure without the stress of making litigants recount all of

their interpersonal dierences in open court and having rulings

imposed aer a long day of angry testimony. I have already par-

ticipated in several remote settlement conferences with oppos-

ing counsel, parties, and, in some cases, the Guardian Ad Litem

appearing by telephone or video. Even in seemingly impossible

cases involving adultery, protective orders, and domestic

violence allegations, the matters have settled. Literal sighs

of relief echoed among all involved knowing that the matters

would simply be removed from the docket by submission of

agreed orders rather than playing the waiting game and endur-

ing several more months of litigation.

If the matter is too complex or controversial for a simple

settlement conference, or if the attorneys reach an impasse,

mediation is an excellent option for accessing neutral assistance

without the stress of a trial. e Hon. Winship Tower (ret.), an

experienced mediator specializing in complex divorces, prac-

ticed family law before joining the Virginia Beach Juvenile and

Domestic Bench in 2000. Judge Tower reports a high level of

success with remote mediation noting that she has concluded

multiple remote mediations and enthusiastically recommends

the process.

“It has proven to be a exible, viable alternative to resolving

family law matters creatively and constructively,” Judge Tower

added. “Clients have expressed relief and gratitude for the

opportunity to bring certainty and closure.”

Once families put litigation behind them, they can begin

the work of healing and restoring their children’s security

and condence, which also requires a new approach. Archer

reminds us that even though parents have dierences, it is

critical to nd common ground, particularly now, stating, “It is

already apparent that combining the eects of COVID-19 and

domestic litigation…can have debilitating eects on the mental

health” of family members. Archer urges parents to “maintain

positive and close relationships with their children,” adding,

“the quality of the parent – child relationship is the single best

predictor of the child’s emotional development.”

When parents struggle to communicate about parenting

issues, it may be wise for them to consider remote mental

health services. Due to the pandemic, many insurance providers

are waiving copayments and authorizing insurance payments

for “telehealth” or video therapy. Remote family or co-parent-

ing sessions may be easier than traditional sessions for post-di-

vorce couples who nd it dicult to be in the same room.

Having professional guidance during sensitive conversations

Family Law continued on page 23

VIRGINIA LAWYER | June 2020 | Vol. 69 | GENERAL PRACTICE

18

www.vsb.org

Y who is not a party

to a lawsuit, but suddenly receives a subpoena

demanding the production of thousands of

documents on a tight timeframe. Your client

wants to either delay production or substan-

tially limit the documents it must hunt down

and produce.

Below are some practice pointers to

keep in mind when advising your client and

responding to a subpoena.

Check for subpoena validity

ird parties are only legally required to pro-

duce documents when production requests

are accompanied by a valid subpoena.

1

Issuing a valid subpoena can be surprisingly

complicated, and many attorneys and the

vendors they hire fail to follow the necessary

steps. Even if you know you’ll eventually pro-

duce documents, it can be helpful to use sub-

poena validity as a negotiating tool. Here are

some common mistakes in attorney-issued

subpoenas:

e subpoena is from a state court and was

not properly domesticated

A state court’s jurisdiction does not extend

into another state, and subpoenas are not

enforceable across state lines. Many attor-

neys fail to take the necessary, simple steps to

domesticate their state court subpoenas before

serving them across state lines. If the subpoena

was issued by a court in State A and served in

State B, it’s generally not valid.

Moreover, a non-party’s “minimum con-

tacts” are not automatically sucient to grant

subpoena power to state courts even when

service was eected within the same state.

For example, parties to a Virginia state court

lawsuit served a subpoena on Yelp’s regis-

tered agent in Virginia. Yelp had no physical

presence in Virginia and the documents were

in California. e Supreme Court of Virginia

refused to enforce the subpoena, nding

that merely registering to do business in the

state and designating a registered agent was

not enough to give Virginia courts subpoena

power when Yelp was not a party to the law-

suit.

2

e subpoena seeks pre-hearing discovery in

an arbitration

Most arbitration is subject to the Federal

Arbitration Act (“FAA”). e FAA permits

arbitrators to issue a summons for third par-

ties to “appear before” the arbitrator and bring

Practice Points: Three Tips for Responding to a

Subpoena Duces Tecum

by Lindsay Reimschussel

GENERAL PRACTICE | Vol. 69 | June 2020 | VIRGINIA LAWYER

19

www.vsb.org

PRACTICE POINTS

documents “which may be deemed material as evidence in the

case.”

3

e majority view is that an arbitrator can only summon

documents to be brought to a hearing, and cannot compel

pre-hearing discovery from third parties.

4

Only one circuit has

denitively stated that arbitrators can compel third parties to

produce documents prior to the hearing.

5

e subpoena fails to check all the boxes.

Most states have a statute setting out the required elements of

an attorney-issued subpoena. Many attorneys and the vendors

they engage oen fail to include all of them. For example, many

states also require the requesting party to notify the other par-

ties before issuing a subpoena.

6

We’ve also seen cases where an

attorney signs paperwork authorizing a vendor to issue a sub-

poena, but the vendor fails to sign or date the actual subpoena.

For arbitration-related summons, the FAA states that the sum-

mons must come from the arbitrator,

7

but many attorneys try

to issue arbitration-related summons themselves.

Check for deadlines and procedures to preserve

objections

You also need to ensure you haven’t waived your ability to seek

court relief by failing to le or serve timely objections.

If the subpoena is federal, the non-party has the earlier of

the date of compliance or 14 days to serve objections on the

requesting party.

8

If the subpoena was validly domesticated

under the Uniform Interstate Depositions and Discovery Act

(“UIDDA”),

9

the discovery rules of the state where the sub-

poena is domesticated normally apply.

10

But state court proce-

dures vary widely. For example, Maryland requires objections

to be led with the court.

11

Virginia, on the other hand, requires

objections to be served on the requesting party.

12

Similarly,

check the corresponding state statutes for deadlines to ensure

you haven’t waived your objections.

Negotiate, negotiate, negotiate

You can start negotiating while also preserving your objec-

tions. Even while exchanging formal objections and responses,

it is oen helpful to engage in informal discussions with the

requesting counsel.

Parties to lawsuits generally would prefer to avoid both-

ering the court with motions to compel and other discovery

disputes, and courts are hesitant to impose undue burdens,

especially on non-parties. Another potential negotiating tool

is that some states require the requesting party to pay the

non-party’s reasonably incurred costs of production, which can

include time spent locating documents as well as photocopying

costs.

13

When faced with the costs of retrieving and producing

thousands of documents, a requesting party may be willing to

reduce the scope of the request.

In my experience, you can almost always negotiate the scope of

a subpoena to something that is more manageable before pro-

ceeding to costly motions practice.

Endnotes

1 See, e.g., F.R.C.P. 34(c); Virginia Supreme Court Rule 4:9A; Texas Rule of

Civil Procedure 205.1.

2 Yelp, Inc. v. Hadeed Carpet Cleaning, Inc., 770 S.E.2d 440, 446 (2015)

(“Because the underlying concepts of personal jurisdiction and subpoena

power are not the same, the question of whether Yelp would be subject to

personal jurisdiction by Virginia courts as a party defendant is irrelevant.”).

e Virginia Supreme Court explicitly distinguished Yelp’s situation from

one where a foreign corporation has a physical presence in Virginia. Id. at

n. 17 (“[O]ur holding does not mean that a Virginia court could not com-

pel in-state discovery from a non-party foreign corporation that maintains

an oce in Virginia.”).

3 9 U.S.C. § 7.

4 CVS Health Corp. v. Vividus, LLC, 878 F.3d 703, 706 (9th Cir. 2017) (not-

ing that its decision was in agreement with the Second, ird, and Fourth

Circuits). See also Managed Care Advisory Grp., LLC v. CIGNA Healthcare,

Inc., 939 F.3d 1145, 1159-60 (11th Cir. 2019) (adopting the majority

approach).

5 Sec. Life Ins. Co. of Am. v. Duncanson & Holt (in Re Sec. Life Ins. Co. of

Am.), 228 F.3d 865, 870-71 (8th Cir. 2000) (“[I]mplicit in an arbitration

panel’s power to subpoena relevant documents for production at a hearing

is the power to order the production of relevant documents for review

by a party prior to the hearing.”). In the Fourth Circuit, the arbitrator

lacks power to compel pre-hearing discovery from non-parties, but the

district court can compel pre-hearing discovery “upon a showing of ‘spe-

cial needor hardship.’” Deiulemar Compagnia di Navigazione S.P.A. v.

M/V Allegra, 198 F.3d 473, 479 (4th Cir. 1999). e Sixth Circuit has not

denitively stated a position on the issue. See, e.g., Westlake Vinyls, Inc. v.

Lamorak Ins. Co., No. 3:18-MC-00012-JHM-LLK, 2018 U.S. Dist. LEXIS

220196, at *14 (W.D. Ky. 2018) (discussing Sixth Circuit precedent).

6 See, e.g., Delaware Chancery Court Rule 45(b) (“Prior notice of any com-

manded production of documents, electronically stored information, and

tangible things or inspection of premises before trial shall be served on

each party . . . .”).

7 9 U.S.C. § 7.

8 FRCP 45.

9 e UIDDA permits parties from out of state to easily domesticate non-

party subpoenas. Aer receiving the correct paperwork under the UIDDA,

the state court where the non-party is located will issue a subpoena that

is binding on the resident non-party. A current list of all states who have

ratied the UIDDA is available on the website for the Uniform Law

Commission at https://www.uniformlaws.org/committees/communi-

ty-home?CommunityKey=181202a2-172d-46a1-8dcc-cdb495621d35.

10 See, Model UIDDA § 5, Comment (“[T]he discovery procedure must be

the same as it would be if the case had originally been led in the discovery

state.”).

11 Maryland Rule of Civil Procedure 510.1(g).

12 Virginia Code § 16.1-265; Virginia Supreme Court Rule 4:9A(c).

13 See, e.g., Fl. Statute 92.153(2)(a) (“In any proceeding, a disinterested wit-

ness shall be paid for any costs the witness reasonably incurs either directly

or indirectly in producing, searching for, reproducing, or transporting doc-

uments pursuant to a summons . . . .”).

Lindsay Reimschussel is an attorney at Zobrist Law Group, PLLC, where

her practice focuses on business and commercial dispute resolution.

Reimschussel regularly assists a Fortune 500 company with responses to

third-party subpoenas.

VIRGINIA LAWYER | June 2020 | Vol. 69 | GENERAL PRACTICE

20

www.vsb.org

T signicantly

transformed workers’ rights, producing more

than 50 employment-related bills that became

eective July 1. Some bills make minor adjust-

ments, while others are signicant, including

strong protections to remedy wage the and

inequality, combat discrimination, and pro-

hibit whistleblower retaliation. is article

summarizes the new worker protections and

the implications for employees, employers,

and the Commonwealth.

1

Private Right of Action for Wage e and

Extensive Changes to Other Wage Laws

Prior to 2020, Virginia wage law lacked any

private right of action for wage the, and in

contrast to Maryland and Washington, D.C.,

employers were subject only to the federal

minimum wage. Nearly a dozen bills amend

Virginia’s wage law by establishing a mini-

mum wage, creating a private right of action

for wage the, expanding the authority of the

Department of Labor and Industry (DOLI) to

remedy wage the, and prohibiting retaliation

against employees who disclose wage the and

other violations of the wage laws.

Virginia’s minimum wage will increase

from the federal minimum to $9.50 per hour,

eective May 1, 2021.

2

It will increase gradu-

ally to $15 an hour by January 2026, though

the legislature will have to reenact the provi-

sion by July 1, 2024 for the full increase to take

eect.

3

And eective July 1, 2020, piece-rate

and domestic workers must be paid the mini-

mum wage, ending existing exceptions.

4

As of July 1, 2020, employees will have

a statutory cause of action to recover unpaid

wages.

5

And employees will be able to bring

wage the claims jointly or as a collective

action.

6

Employees need not exhaust adminis-

trative remedies before ling suit.

7

A prevail-

ing wage the plainti can recover any owed

wages, liquidated damages in an amount equal

to the wages owed, prejudgment interest at

an annual rate of 8% from when the wages

were due, and reasonable attorneys’ fees and

costs.

8

Where an employer has knowingly

withheld wages, a prevailing employee can

recover treble damages.

9

e statute denes

“knowingly” as having “actual knowledge

of the information … act[ing] in deliberate

ignorance of the truth or falsity of the infor-

mation, or … act[ing] in reckless disregard of

the truth or falsity of the information” – there

is no requirement to prove specic intent to

defraud.

10

2020 Legislative Session Heralds a Sea Change

in Virginia Employment Law

by Jason Zuckerman and Dallas Hammer

GENERAL PRACTICE | Vol. 69 | June 2020 | VIRGINIA LAWYER

21

www.vsb.org

EMPLOYMENT LAW

Previously, Virginia’s DOLI could investigate wage the

only when an employee led a complaint.

11

But now DOLI can

conduct a broader investigation of an employer’s wage practices

where it develops information in the course of an investigation

indicating that the employer has failed to pay wages to other

employees.

12

As lower-income workers disproportionately experience

wage the, protection against retaliation is especially vital. As of

July 1, 2020, Virginia employers are prohibited from retaliating

against any employee for ling a complaint or commencing or

testifying in a wage the proceeding.

13

Retaliation complaints

will be led with DOLI, and the commissioner may institute

proceedings on behalf of the employee for reinstatement, recov-

ery of lost wages, and liquidated damages in the amount of the

lost wages.

14

e amendments to Virginia’s wage laws also prohibit

retaliation against employees for asking about or discussing

compensation or for reporting a violation of the provision.

15

A

violation will subject an employer to a civil penalty of $100, and

DOLI is authorized to obtain injunctive relief.

16

Virginia Values Act and Other Legislation Combatting

Discrimination

e Virginia Values Act

17

amends the Virginia Human Rights

Act (HRA)

18

by adding sexual orientation and gender iden-

tity as protected classes.

19

Virginia now joins 20 states and

Washington, D.C., in going a step further than Title VII and

explicitly prohibiting employment discrimination based on

sexual orientation and gender identity.

20

e Values Act also

expands employer coverage, the range of actionable personnel

actions, and the remedies available under the law.

Previously, the HRA covered employers with more than

ve and fewer than 15 employees. Now, for most unlawful dis-

crimination claims the HRA covers employers with 15 or more

employees, and for most unlawful termination claims it covers

employers with more than ve employees.

21

Employers are

also prohibited from retaliating against employees for oppos-

ing an unlawful employment practice or for ling a charge or

otherwise participating in an investigation of discrimination.

22

Further, employees now have a private right of action under the

HRA to challenge any unlawful, discriminatory employment

practice.

23

Prior to these amendments, the HRA provided a pri-

vate cause of action only for unlawful termination.

e Values Act expands the remedies available under the

HRA. Formerly, a prevailing plaintiff under the HRA could

receive only up to 12 months of backpay and attorneys’ fees

not to exceed 25% of the backpay award. Now, a prevailing

employee may receive uncapped economic and compensa-

tory damages, punitive damages of up to $350,000,

24

and

reasonable attorneys’ fees and costs.

25

Additional legislation amends the HRA to strengthen and

expand rights and remedies for employees who are pregnant or

postpartum.

26

Whereas employees alleging discrimination on

other bases must still exhaust administrative remedies through

the Division of Human Rights before suing in court,

27

an

employee alleging discrimination or refusal to accommodate on

the basis of pregnancy, childbirth, or related conditions may le

directly in court.

28

Further, the HRA now requires employers to

provide reasonable accommodations for pregnant or postpar-

tum employees.

29

ese provisions apply to employers with ve

or more employees for all claims, making employer coverage

for pregnancy and related discrimination broader than that for

other causes of action under the HRA.

30

Under the pregnancy accommodation provision, rea-

sonable accommodation includes a modied work schedule,

assistance with heavy liing, provision of a private location

other than a bathroom for expression of breastmilk, and leave

to recover from childbirth.

31

A covered employer is required

to provide reasonable accommodation unless they can prove

that the accommodation would cause an undue hardship.

32

e employer providing or being required to provide simi-

lar accommodation to other employees creates a rebuttable

presumption against hardship.

33

Aer an employee requests

accommodation, the parties should engage in an interactive

process to determine if the request is reasonable, and if not, to

pursue other options.

34

Other legislation strengthens the prohibition against race

discrimination by covering traits historically associated with

race, including hair texture, type, and protective styles such as

braids, locks, and twists.

35

New Legislation Prohibiting Whistleblower Retaliation

Prior to 2020, Virginia recognized a very narrow public policy

exception to employment-at-will. Eective July 1, 2020, how-

ever, whistleblowers in Virginia will have robust protection

against retaliation. Protected conduct includes reporting in

good faith a violation of law to a supervisor, governmental

body, or law enforcement ocial; refusing to engage in a crim-

inal act that would subject the employee to criminal liability;

refusing an employer’s order to perform an unlawful act; or

providing information to or testifying before any enforcement

body or ocial conducting an investigation, hearing, or inquiry

into any alleged violation of law by the employer.

36

e statute

does not protect employees disclosing data protected by law or

legal privilege, making statements or disclosures that are false

or made in reckless disregard of the truth, or making disclo-

sures that would violate the law or deprive another or others of

condential communications as guaranteed by law.

37

A retaliation claim can be brought within one year of the

retaliatory action,

38

and a prevailing whistleblower can secure

an injunction to stop a continuing violation, reinstatement,

compensation including lost wages and benets plus interest,

and attorneys’ fees and costs.

39

Implications of e New Virginia Employment Laws

ese new employment laws represent a sea change for work-

ers’ rights in Virginia, and employers will act at their peril when

they discriminate or retaliate against employees. Additional

implications include:

VIRGINIA LAWYER | June 2020 | Vol. 69 | GENERAL PRACTICE

22

www.vsb.org

EMPLOYMENT LAW

• e Values Act will likely foster more diverse and tol-

erant workplaces, which could make Virginia business

more protable and competitive as it seeks to attract busi-

nesses and workers that will thrive in the digital age. e

benets of diversity in the workplace include increased

innovation and employee engagement, lower turnover,

and superior decision-making.

• A robust whistleblower protection law will encourage

employees to report unlawful conduct internally, thereby

beneting employers by giving them an opportunity to

investigate and rectify misconduct.

• As Virginia civil procedure respects the important right

to a jury trial by making it dicult to obtain summary

judgment,

40

there will likely be a mass migration of

employment litigation from federal court to Virginia

circuit court. More employment cases will go to trial, and

jury verdicts could encourage employers to comply with

these laws. In addition, employment litigation will likely

become a much larger portion of circuit court dockets.

• Employers will need to take steps to comply with these

new laws and mitigate against the risk of employees

bringing claims. For example, employers should consider

training managers and supervisors about discrimination

and retaliation. In addition, employers should update

their policies prohibiting discrimination and retaliation.

Some employment law practitioners have criticized

Virginia’s new employment laws as rendering the

Commonwealth the “new California,” a state known for

its strong employment and consumer protection laws.

California also has the world’s h largest economy, surpass-

ing the United Kingdom, and is a worldwide hub of innova-

tion, attracting top engineers from around the world to create

products and services that have fundamentally changed how

we communicate and transact business. Strong employment

legislation should not be viewed as a burden, and instead could

hasten Virginia becoming the “Silicon Valley of the East.”

e authors thank Katherine Krems, an associate at Zuckerman

Law, for her contributions to the article. q

Endnotes

1 At the time of writing, these bills have not yet been entered into the state

code. Code sections as cited are subject to change. All sections cited for

new provisions are where the bills as written list them, but there is some

overlap and disagreement that the code commission will reconcile.

2 See Va. Code § 40.1-28.10(B); H.B. 395/S.B. 7, Gen. Assemb., 2020

Reconvened Sess. (Va. 2020) (amended bills reenrolled Apr. 22, 2020).

ough originally set for January 1, 2021, the legislature delayed the

rst increase at Gov. Ralph Northam’s suggestion to support businesses

in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. See Press Release, Oce of the

Governor, Governor Northam Hails General Assembly Session at

Propels Virginia Forward (Apr. 22, 2020), https://www.governor.virginia

.gov/newsroom/all-releases/2020/april/headline-856287-en.html (“I am

grateful that lawmakers supported my proposals to help ease the impacts of

the COVID-19 pandemic on Virginians, on our economy, and on our state

budget.”).

3 Va. Code §§ 40.1-28.10(F), (3); H.B. 395/S.B. 7.

4 Va. Code § 40.1-28.9(A); S.B. 78, Gen. Assemb., 2020 Reg. Sess. (Va. 2020);

S.B. 804, Gen. Assemb., 2020 Reg. Sess. (Va. 2020).

5 Va. Code § 40.1-29(J); H.B. 123/S.B. 838, Gen. Assemb., 2020 Reg. Sess.

(Va. 2020).

6 Id.

7 Id.

8 Id.

9 Id.

10 Va. Code § 40.1-29 (K); H.B. 123/S.B. 838.

11 Va. Code § 40.1-29 (F).

12 Id. at § 40.1-29.1; H.B. 336/S.B. 49, Gen. Assemb., 2020 Reg. Sess. (Va.

2020).

13 Va. Code § 40.1-33.1(A); H.B. 337/S.B. 48, Gen. Assemb., 2020 Reg. Sess.

(Va. 2020).

14 Va. Code § 40.1-33.1(B); H.B. 337/S.B. 48.

15 Va. Code § 40.1-28.7:7(A); H.B. 622, Gen. Assemb., 2020 Reg. Sess. (Va.

2020). is code section may change, as H.B. 330/S.B. 480 as written add a

separate, unrelated stipulation to the same section.

16 Va. Code §§ 40.1-28.7:7(B), (C); H.B. 622.

17 S.B. 868, Gen. Assemb., 2020 Reg. Sess. (Va. 2020).

18 Va. Code §§ 2.2-3900 et. seq.

19 Id. at §§ 2.2-3901(B), (C); 2.2-3905(B)(1)(a); S.B. 868.

20 See 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2.

21 Va. Code § 2.2-3905(A); S.B. 868. Coverage for unlawful termination based

on age remains unchanged, with the HRA covering employers with more

than ve and fewer than 20 employees. Id.

22 Va. Code § 2.2-3905(7); S.B. 868.

23 Va. Code § 2.2-3908(A); S.B. 868.

Jason Zuckerman is a principal at Zuckerman Law, where he focuses

on representing workers in employment-related disputes, includ-

ing whistleblower retaliation and rewards claims. During the Obama

Administration, he served as senior legal advisor to the special counsel

at theU.S. Oce of Special Counsel, the agency charged withprotecting

whistleblowers in the federal government. In 2012, the secretary of labor

appointed Zuckerman to OSHA’s Whistleblower Protection Advisory

Committee. He is a graduate of the University of Virginia School of Law.

Dallas Hammer is a principal at Zuckerman Law, where he represents

employees in whistleblower, discrimination, and other employment-related

litigation. Hammer leads the rm’s cybersecurity whistleblower practice and

has represented whistleblowers at several of the largest technology compa-

nies. He has written extensively about whistleblowing related to cybersecu-

rity and data privacy. Hammer is a graduate of the Georgetown University

Law Center.

GENERAL PRACTICE | Vol. 69 | June 2020 | VIRGINIA LAWYER

23

www.vsb.org

may lead to greater success in resolving disputes over parenting

issues such as when it is safe to resume socializing or travel,

whether to alter summer visitation, or how to deal with cancel-

lations or lack of childcare. It seems apparent that the Courts

will not be addressing these micro-disputes for quite some time,