healthy through habit:

Interventionsforinitiating

& maintaining health

behavior change

Wendy Wood & David T. Neal

abstract

Interventions to change health behaviors have had

limited success to date at establishing enduring healthy

lifestyle habits. Despite successfully increasing people’s

knowledge and favorable intentions to adopt healthy

behaviors, interventions typically induce only short-

term behavior changes. Thus, most weight loss is

temporary, and stepped-up exercise regimens soon

fade. Few health behavior change interventions have

been successful in the longer term. In this article,

we unpack the behavioral science of health-habit

interventions. We outline habit-forming approaches

to promote the repetition of healthy behaviors, along

with habit-breaking approaches to disrupt unhealthy

patterns. We show that this two-pronged approach—

breaking existing unhealthy habits while simultaneously

promoting and establishing healthful ones—is best for

long-term beneficial results. Through specific examples,

we identify multiple intervention components for health

policymakers to use as a framework to bring about

lasting behavioral public health benefits.

re view

a publication of the behavioral science & policy association 71

Healthy through habit:

Interventionsforinitiating &

maintaining health behavior change

Wendy Wood & David T. Neal

abstract. Interventions to change health behaviors have had limited

success to date at establishing enduring healthy lifestyle habits. Despite

successfully increasing people’s knowledge and favorable intentions to

adopt healthy behaviors, interventions typically induce only short-term

behavior changes. Thus, most weight loss is temporary, and stepped-up

exercise regimens soon fade. Few health behavior change interventions

have been successful in the longer term. In this article, we unpack the

behavioral science of health-habit interventions. We outline habit-forming

approaches to promote the repetition of healthy behaviors, along with

habit-breaking approaches to disrupt unhealthy patterns. We show that

this two-pronged approach—breaking existing unhealthy habits while

simultaneously promoting and establishing healthful ones—is best for long-

term beneficial results. Through specific examples, we identify multiple

intervention components for health policymakers to use as a framework to

bring about lasting behavioral public health benefits.

I

n 1991, the National Cancer Institute and industry

partners rolled out a nationwide educational public

health

*******

campaign—the 5 A Day for Better Health

Program—to boost consumption of fruits and vege-

tables. The campaign was remarkably successful in

changing people’s knowledge about what they should

eat: Initially, only 7% of the U.S. population understood

that they should eat at least five servings of fruit and

vegetables per day, whereas by 1997, fully 20% were

Wood, W., & Neal, D. T. (2016). Healthy through habit: Interventions for

initiating & maintaining health behavior change. Behavioral Science &

Policy, 2(1), pp. 71–83.

aware of this recommendation.

1

Unfortunately, actual

fruit and vegetable consumption remained flat. During

the years 1988 to 1994, 11% of U.S. adults met this target

amount of fruit and vegetable consumption, and the

percentage did not shift during 1995–2002.

2

Another

national campaign launched in 2007, called Fruit &

Veggies—More Matters, also failed to move the fruit and

vegetable consumption needle.

3

These failures are not surprising. A body of research

shows that many public health campaigns do success-

fully educate and motivate people, especially in the

short run. However, when push comes to shove, they

often fail at changing actual behaviors and long-term

review

72 behavioral science & policy | volume 2 issue 1 2016

health habits, such as the consumption of optimal

amounts of fruit and vegetables.

4,5

Not all behavior change interventions fail to change

behavior. Often, some behavior change happens, but it

does not maintain over time.

6

To show how this works,

we depicted the results of some of the highest quality

health interventions to date in Figure 1. These studies

all appeared in top scientific journals, used exemplary

methods, and conscientiously assessed long-term

success rates.

7–10

It is easy to see that most participants

in these interventions got healthier in the short term (as

shown by the initially increasing lines). They lost weight,

exercised more, and gave up smoking. However, once

the intervention ended, old patterns reemerged, and

the new, healthy behaviors clearly waned over time (as

shown by the eventually decreasing lines). The overall

trajectory of behavior change can be described as a

triangular relapse pattern.

It is tempting to believe that the failures in main-

taining healthy behaviors depicted in Figure 1 are

D: Mean number of minutes per week of moderate to vigorous physical

exercise during computer-delivered interventions or health program

controls at 6 months of treatment, 12 months of treatment, and 6 months

after end of treatment (Ns = 70 control and 75 computerized treatment at

baseline; N = 61 computerized treatment at 18 months). Data are from

“Exercise Advice by Humans Versus Computers: Maintenance Eects at 18

Months,” by A. C. King, E. B. Hekler, C. M. Castro, M. P. Buman, B. H. Marcus

,

R. H. Friedman, and M. A. Napolitano, 2014, Health Psychology, 33, p. 195,

Figure 1. Copyright 2014 by the American Psychological Association.

Figure 1. The triangular relapse pattern in health behavior change over time

Start

A. Intervention of financial incentives for weight loss B. Intervention of payment for gym visits

C. Intervention of smoking information

and financial incentives to quit

D. Intervention via computer

to encourage physical activity

In these triangular relapse patterns, an initial spike in healthful behaviors during the intervention is followed by a decline following

intervention back toward baseline. Panels A–D show four examples of behavior change interventions following this pattern for

(A) weight loss, (B) gym visits, (C) quitting smoking, and (D) exercise. Mos = months; MVP = moderate to vigorous physical activity.

A: Mean pounds lost following a 4-month intervention of financial incentives

for weight loss and after 3 months of no treatment (N = 57). Data are from

“Financial Incentive–Based Approaches for Weight Loss: A Randomized

Trial,” by K. G. Volpp, L. K. John, A. B. Troxel, L. Norton, J. Fassbender, and

G. Loewenstein, 2008, Journal of the American Medical Association, 300,

p. 2635. Copyright 2008 by the American Medical Association.

B: Mean gym visits per week prior to study (weeks -16 to -2), during 5

intervention weeks of payment for attending, and during 15 no-treatment

weeks (weeks 6–21, N = 99). Data are from “Incentives to Exercise,” by G.

Charness and U. Gneezy, 2009

, Econometrica, 77, p. 921, Figure 2b.

Copyright 2009 by Wiley.

C: Percentage of participants who quit smoking (biochemically verified) at 3

or 6 months and at 15 or 18 months following intervention of information

about smoking cessation programs paired with financial incentives (N =

878). Data are from “A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Financial Incentives

for Smoking Cessation,” by K. G. Volpp, A. B. Troxel, M. V. Pauly, H. A. Glick,

A. Puig, D. A. Asch, . . . J. Audrain-McGovern, 2009, New England Journal

of Medicine, 360, p. 703, Table 2. Copyright 2009 by the Massachusetts

Medical Society.

15

10

5

0

Mean number of pounds lost

End of 4 months’

treatment

7 months

2.5

2

1.5

1

0.5

Mean number gym visits/week

Prior to

intervention

5-week

intervention

Post

intervention

Deposit contract plus lottery

No treatment control

Payment

No payment control

Intervention

25

20

15

10

5

0

Percent sample quit

Quit at 3

or 6 mos

Quit at 15

or 18 mos

190

155

115

75

Mean minutes of MVP/week

Baseline12 mos of

treatment

6 mos

follow-up

Information plus financial incentive

Information only

Computerized physical activity prompts

Control

6 mos of

treatment

a publication of the behavioral science & policy association 73

simply due to people’s limited willpower. Surely many

people struggle to inhibit the short-term gratifications

of fast food and the lure of excessive TV watching and

do not make the eort to stick to a balanced diet and

regular exercise. However, relapse is not inevitable if

behavior change interventions form healthy habits. In

fact, research shows that people who consistently act in

healthy ways in daily life do so out of habit. With heathy

diet and exercise habits, they do not need to struggle

with internal urges to act in unhealthy ways.

11,12

Another

insight comes from the success of policy changes

and health interventions in the last few decades that

drastically reduced smoking rates in the United States.

Antismoking campaigns have many components,

13

but

the most successful parts targeted cigarette purchase

and smoking habits as opposed to people’s willpower

and self-control. In this article, we use these insights

as a framework to construct interventions that break

unhealthy habits and encourage the adoption of bene-

ficial ones.

Both breaking and creating habits are central to

behavior change. Habits play a significant role in

people’s failure to adopt and stick with what is best

for their health. Eating habits are especially striking.

Research has shown that people habitually consume

food that they neither want nor even like.

14

For example,

movie theater patrons with strong popcorn-eating

habits consumed just as much stale, week-old popcorn

as they did fresh popcorn, despite reporting that they

hated the stale food.

15

Fortunately, just as bad habits impede behavior

change, good habits can promote it. As noted above,

good habits ensure that people continue to act in

healthy ways without constant struggle. For example,

chocolate lovers who had formed a habit to eat carrots

continued to make the healthy carrot choice even when

chocolate became available.

16

Habits represent context–response associations

in memory that develop as people repeat behav-

iors in daily life. For example, after repeatedly eating

hamburgers and pizza for dinner, a person is likely to

find that dinnertime cues such as driving home from

work and watching the evening news automatically acti-

vate thoughts of these foods and not vegetables.

17

From a habit perspective, behavior change interven-

tions are likely to fail unless they account for the ways in

which people form healthy habits and break unhealthy

ones. Although the research literature on behavior

change oers sophisticated understanding of many

intervention features (for example, oering appropriate

incentives, tailoring messages to specific subsets of the

target audience, tracking nonintrusive outcomes such as

credit card charges), little attention has been paid to the

importance of habits in maintaining lifestyle choices.

In the first part of this article, we explain how inter-

ventions create healthy habits. Essentially, healthy habit

creation involves repeated performance of rewarding

actions in stable contexts. The second part of the article

addresses how interventions can break unhealthy habits

by neutralizing the cues that automatically trigger these

responses. Our set of habit-based interventions thus

augments existing tools to promote automated perfor-

mance of desired over undesired responses. Among

existing tools, people are most likely to make a good

choice when decisions are structured to make that

choice easy,

18,19

when other people are making the same

choice,

20,21

and after forming if-then plans.

22,23

Finally,

we explain how habit-based interventions can be incor-

porated into health policies.

Promoting the Formation of New Habits

The three central components of habit formation are

(a)behavioral repetition, (b) associated context cues,

and (c) rewards (see Table 1).

Behavior change interventions form habits by getting

people to act in consistent ways that can be repeated

frequently with little thought. Habits develop gradually

through experience, as people repeat a rewarded action

in a stable place, time, or other context. Through repe-

tition, the context becomes a sort of shorthand cue for

what behavior will be rewarded in that context. People’s

habits essentially recreate what has worked for them in

the past. In this way, habits lock people into a cycle of

automatic repetition.

Once a habit has formed, it tends to guide behavior

even when people might have intended to do some-

thing else.

24

Essentially, habits come to guide behavior

instead of intentions. Early in habit formation, people

might intentionally decide how to respond to achieve

Existing habits are a significant impediment to

people adopting and sticking with healthy behavior

74 behavioral science & policy | volume 2 issue 1 2016

a certain outcome. However, once a habit gains

strength, people tend to habitually respond, for better

or worse.

25

According to a study in the British Journal

of Health Psychology, eating habits were stronger

determinants of food choices than intentions or even

sensitivity to food temptations.

26

When habits are

healthy, outsourcing behavioral control to the environ-

ment in this way is beneficial. People keep on track by

responding habitually when distractions, stress, and dips

in willpower impede decision-making.

27

However, when

habits are unhealthy, the automatic or environmental

control of behavior impedes health and can create a

self-control dilemma.

Next, we expand on the central components of habit

formation and later address unhealthy habits.

The Three Central Habit-Forming Interventions

Behavior Repetition

Habit formation interventions create opportunities

for and encourage frequent repetition of specific

responses, but there is no single formula for success. In

one study, participants chose a new health behavior to

perform once a day in the same context (for example,

eating fruit after dinner).

28

For some behaviors and

some people, only 18 days of repetition were required

for the behavior to become suciently automatic to be

performed without thinking. For other behaviors and

participants, however, over 200 days of repetition were

needed. Another study published in Health Psychology

29

found that people required 5 to 6 weeks of regular gym

workouts to establish new exercise habits.

30

Interventions may encourage repetition by visu-

ally depicting the physical act of repeating the desired

behavior—think of the famous Nike advertisements

advising, “Just Do It,” while showing famous athletes

and others engaged in vigorous exercise. Interven-

tions in schools and other controlled environments

could direct physical practice of the new habit by, for

example, conducting hand-washing drills in bath-

rooms instead of merely teaching hygiene benefits and

setting performance goals.

31

Hospitals and restaurants

can similarly benefit from employees rehearsing best

sanitationpractices.

Longer interventions with frequent repetitions (vs.

shorter interventions, with fewer repetitions) tend to be

most successful because they are most likely to lead

to the formation of strong habits. Such a pattern could

explain the greater success of long-duration weight loss

interventions.

5

Intervention length also might explain

one of the most successful behavioral interventions:

Opower’s multiyear energy conservation programs.

32

These multicomponent interventions, involving smart

meters and feedback about power use, have proved

especially successful at limiting energy use, presumably

because the extended intervention allowed consumers

to form energy-saving habits.

Context Matters: Cues Trigger Habit Formation

Successful habit learning depends not only on repeti-

tion but also on the presence of stable context cues.

Context cues can include times of day, locations, prior

actions in a sequence, or even the presence of other

people (see Table 1). Illustrating the importance of stable

cues, almost 90% of regular exercisers in one study had

a location or time cue to exercise, and exercising was

more automatic for those who were cued by a partic-

ular location, such as running on the beach.

33

Other

research shows that older adults are more compliant

with their drug regimens when pill taking is done in a

particular context in their home (for example, in the

bathroom) or integrated into a daily activity routine.

34

Implementation plans. Intervention programs to

form healthy habits can promote stable habit cues in

Table 1. Three main components of habit

formation interventions and examples

of implementation in practice

Principle Examples in practice

Frequent

repetition

• School hand-washing interventions that

involve practicing actual washing behavior

in the restroom

Recurring

contexts and

associated

context cues

• Public health campaigns linking changing

smoke detector batteries to the start and

end of daylight savings time

• Medical compliance communications

that piggyback medications onto existing

habits such as mealtime

Intermittent

rewards

• Free public transit days scheduled

randomly

• Coupons and discounts for fresh fruits and

vegetables provided on an intermittent or

random basis

a publication of the behavioral science & policy association 75

several ways. People can be encouraged to create plans,

or implementation intentions, to perform a behavior in a

given context (for example, “I will floss in the bathroom

after brushing my teeth”).

18

Forming implementation plans increases the likeli-

hood that people will carry out their intentions.

35

Accord-

ingly, these plans promote performance only for people

who already intend to perform the healthy behavior (for

example, people who want to floss more regularly),

36

and the ecacy of the intervention fades if their inten-

tions change. Even so, implementation intentions may

be a useful stepping stone on the path to creating habits

because, as people act repeatedly on such intentions in

a stable context, behavior may gradually become less

dependent on intentions and gel into habits.

Piggybacking. Intervention programs also create cues

by piggybacking, or tying a new healthy behavior to an

existing habit. The habitual response can then serve as

a cue to trigger performance of the new behavior. For

example, dental-flossing habits were established most

successfully when people practiced flossing immedi-

ately after they brushed their teeth, rather than before.

37

The large number of habits in people’s daily lives

provides many opportunities to connect a new behavior

to an existing habit.

38

Successful examples include

public information campaigns that link the replacement

of smoke alarm batteries to another periodic activity—

changing the clock for daylight savings; and medical

compliance is boosted when a prescribed health prac-

tice (for example, taking pills) is paired with a daily habit

(for example, eating a meal, going to bed).

39

Rewards Promote Habit Formation

People tend to repeat behaviors that produce positive

consequences or reduce negative ones (see Table 1).

Positive consequences include the intrinsic payo of a

behavior, for instance, the taste of a sweet dessert or the

feeling of accomplishment that comes from eectively

meeting health goals.

40

Positive consequences also

include extrinsic rewards, such as monetary incentives

or others’ approval. Avoiding negative consequences

is illustrated by contingency contracts, such as when

people agree to pay money for every swear word they

utter or experience other negative consequences for

failing to meet a goal.

41

Habits form most readily when specific behaviors are

rewarded. Especially during the initial stages of habit

formation, specific incentives can increase people’s

motivation to do things they might typically avoid,

such as exercising or giving up ice cream. In this sense,

rewards can oset the loss of enjoyable activities in

order to start a healthful behavior.

Other rewards are less successful at habit formation

because they are too broad to promote specific habits.

Overly general rewards include symbolic trophies,

prizes that recognize strong performance, or temporal

landmarks such as birthdays or the kicko of a new

calendar year. Only rewards that promote the repetition

of specific actions contribute to habit formation.

Many decades of laboratory research have shown

what kinds of rewards are most likely to motivate

habits. Surprisingly, habits form best when rewards are

powerful enough to motivate behavior but are uncertain

in the sense that they do not always occur.

42

Uncertain

rewards powerfully motivate repetition and habit forma-

tion. In learning theory terminology, such rewards are

given on random-interval schedules.

Slot machines are a good example of uncertain

rewards. People keep paying money into the machines

because sometimes they win, sometimes they don’t.

This reward system is so powerful that slot machines are

sometimes described as the crack cocaine of gambling.

E-mail and social networking sites have similar eects:

people keep checking on them because sometimes they

are rewarded with interesting communications, but other

times they get only junk. The key is that rewards are

received probabilistically, meaning not for every behavior.

To date, few health interventions have used uncer-

tain rewards.

43

Instead, most health interventions oer

consistent, predicable rewards, such as payments

received each time program participants go to the gym.

Such rewards eectively drive short-term behavior

changes, but they do not establish habits. When the

rewards stop, people usually quit the behavior.

6

In part,

people quit because predictable rewards can signal

that a behavior is dicult, undesirable, and not worth

performing without the reward.

44

Behavior change interventions should give rewards

in the way a slot machine does—at uncertain intervals

Uncertain rewards are most eective

76 behavioral science & policy | volume 2 issue 1 2016

but often enough to suciently motivate people to

perform the target healthy behavior. For example,

discounts on fresh fruits and vegetables at grocery

stores can be provided intermittently to encourage

habitual produce purchases. The structure and routines

of school and work environments are particularly well

suited to providing uncertain rewards. School policies,

especially in elementary schools, could be structured

to provide occasional monitoring and reinforcements

for healthy behaviors such as hand washing after using

the restroom or fruit and vegetable consumption during

school lunches.

The Three Main Habit-Change Interventions

Work Best in Combination.

Only a few health interventions with the general popu-

lation have incorporated all three components of habit

formation: response repetition, stable cues, and uncer-

tain rewards. Yet, the few existing habit-based inter-

ventions that have bundled two or all three of these

components have yielded promising results for weight

loss

45

and consumption of healthy food in families.

46

In one study, for example, overweight participants

were instructed to (a) develop predictable and sustain-

able weight loss routines, (b) modify their home envi-

ronments to increase cues to eat healthy foods and

engage in exercise, and (c) have immediate positive

rewards for weight-loss behaviors.

47

Participants also

were instructed on how to disrupt existing habits by

removing cues that triggered them along with making

unhealthy behaviors less reinforcing (for example,

increasing the preparation time and eort for unhealthy

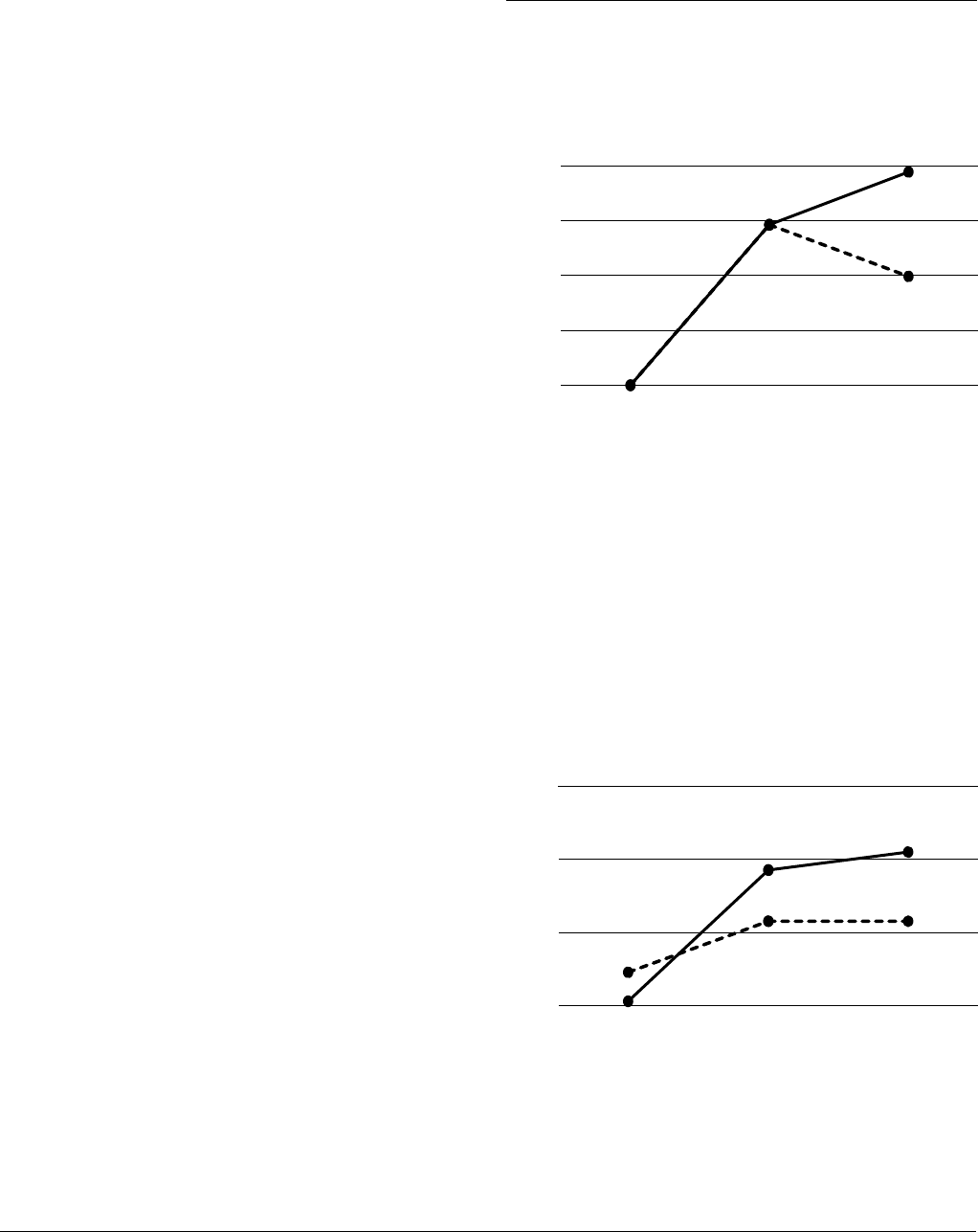

snacks). As depicted in Figure 2A, participants under-

going this multifaceted habit formation and disruption

treatment continued to lose weight during several

months following the end of the intervention, whereas

participants using a more standard weight-loss program

relapsed over time.

A very dierent habit formation intervention used

an electronic monitoring device to promote weight

loss among overweight adolescents.

48

This interven-

tion targeted a specific behavior: the amount and

speed of eating. Cues to eating were standardized by

having participants undergo monitoring by a device

while eating dinner at a table. The device delivered

feedback about success and failure in hitting predeter-

mined goals. As shown in Figure 2B, after 12 months,

Figure 2. Interventions specifically targeting

habits can create enduring behavior change

over tim

e

Baseline

A. Multifaceted habit formation and disruption

weight loss program vs. standard weight loss program

B. Electronic monitoring device to promote control

of eating vs. standard weight loss program

In behavior change in

terventions that target habit formation

and

change, more enduring behavior change is possible.

F

igure A: Mean pounds lost after 3 months (mos) of habit-based or

standa

rd weight loss interventions (N = 59 at baseline, N = 35 at 6 months).

Th

e habit-based intervention emphasized (a) developing and maintaining

heal

thy habits and disrupting unhealthy habits, (b) creating a personal food

an

d exercise environment that increased exposure to healthy eating and

ph

ysical activity and encouraged automatic responding to goal-related

cu

es, and (c) facilitating weight loss motivation. The standard weight loss

pr

ogram involved examining attitudes toward food, body, and weight, such

as

improving body acceptance and understanding social stereotypes. Data

ar

e from “A Randomized Trial Comparing Two Approaches to Weight Loss:

Di

erences in Weight Loss Maintenance,” by R. A. Carels, J. M. Burmeister,

A.

M. Koball, M. W. Oehlhof, N. Hinman, M. LeRoy, . . . A. Gumble, 2014,

Journal

of Health Psychology, 19, p. 304, Figure 2. Copyright 2014 by Sage.

F

igure B: Mean children’s age- and sex-adjusted body mass index (BMI)

af

ter a yearlong intervention using a monitoring device to reduce the

amount

and speed of eating, plus a 6-month follow-up (N = 106 at baseline

an

d 12 months, N = 87 at the 18-month assessment). Data are from

“T

reatment of Childhood Obesity by Retraining Eating Behaviour:

Randomise

d Controlled Trial,” by A. L. Ford, C. Bergh, P. Södersten, M. A.

Sabi

n, S. Hollinghurst, L. P. Hunt, and J. P. Shield, 2010, British Medical

Journal

, 340, Article b5388, Table 2. Copyright 2010 by BMJ.

20

15

10

5

0

Mean pounds lost

3 months 6 months

Habit change program

Control program

Baseline

2.7

2.9

3.1

3.3

Mean BMI, sex and weight adjusted

End of 12 mos

intervention

6 mos after

intervention

Eating training

Standard treatment

a publication of the behavioral science & policy association 77

monitored participants not only ate smaller meals than

participants in a control group did, but they had lost

significant amounts of weight and kept it o 6 months

after the intervention ended.

Breaking Unhealthy Habits

Because habits are represented in memory in a relatively

separate manner from goals and conscious intentions,

existing habits do not readily change when people

adopt new goals. Thus, recognizing the health value of

five servings of fruits and vegetables per day does not,

by itself, remove the cues that trigger consumption of

other less healthful foods. Similarly, incentive programs

to break habits will not necessarily alter the memory

trace underlying the behavior. Familiar contexts and

routines still will bring unhealthy habits to mind, leaving

people at risk of lapsing into old patterns.

49

Even after

new habits have been formed, the existing memory

traces are not necessarily replaced but instead remain

dormant and can be reactivated relatively easily with a

memory cue.

50

Changing unhealthy habits, much like forming

healthy ones, requires an understanding of the

psychology behind habits. Specifically, ridding oneself

of unhealthy habits requires neutralizing the context

cues that automatically trigger habit performance.

The Three Main Habit-Breaking Interventions

Health interventions can incorporate three strategies to

reduce the impact of existing bad cues: (a) cue disrup-

tion, (b) environmental reengineering, and (c) vigilant

monitoring or inhibition (see Table 2). Experiments

show that habit performance is readily disrupted when

contexts have shifted.

50,51

Cue Disruption

Interventions can take advantage of naturally occur-

ring life events—such as moving to a new house,

beginning a new job, or having a child—that reduce or

eliminate exposure to the familiar cues that automat-

ically trigger habit performance (see Table 2). People

are most successful at changing their behavior in daily

life when they capitalize on such life events. In a study

in which people reported their attempts to change

some unwanted behavior, moving to a new location

was mentioned in 36% of successful behavior change

attempts but only in 13% of unsuccessful ones.

52

In

addition, 13% of successful changers indicated that,

to support the change, they altered the environment

where a prior habit was performed, whereas none of the

unsuccessful ones mentioned this.

Habit discontinuity interventions capitalize on this

window of opportunity in which people are no longer

exposed to cues that trigger old habits.

53

For example,

an intervention that provided a free transit pass to car

commuters increased the use of transit only among

those who changed their residence or workplace in the

prior 3 months.

54

Apparently, the move from a familiar

environment disrupted cues to driving a car, enabling

participants to act on the incentive to use transit instead

of falling back on their car-driving habit. Another

study showed that students’ TV-watching habits were

disrupted when they transferred to a new university, but

only if cues specific to this behavior changed, such as

their new residence no longer having a screen in the

living room.

55

Without the old cue to trigger their TV

habits, students only watched TV at the new university if

they intended to.

Many dierent health interventions can be applied

during the window of opportunity provided by life tran-

sitions. For example, new residents could be messaged,

via text or mailers, with incentives to perform healthy

behaviors related to their recent move. These could

include reminders of the public transit options in the

new neighborhood, notices that registration is open

for community fitness classes, and invitations to local

farmers’ markets. Similarly, new employees could be

informed about workplace-related health options

such as employer-sponsored health classes. Also,

reduced insurance rates could be oered if employees

quit smoking or adopt other healthy behaviors. First-

time parents could be engaged by interventions that

encourage the preparation of healthy meals when

cooking at home or that promote enrollment in child-

and-parent exercise classes.

Environmental Reengineering

The impact of unhealthy habit cues also can be reduced

by altering performance environments, or the place

where the unhealthy habit regularly occurs (see Table

2). Although environmental reengineering often involves

cue disruption (as described above), it additionally

78 behavioral science & policy | volume 2 issue 1 2016

introduces new or altered environmental features to

support the healthy behavior. The basic psychological

process involves adding behavioral friction to unhealthy

options and reducing behavioral friction for healthy

ones to lubricate their adoption.

Adding friction. Large-scale social policies can intro-

duce friction into an environment, making it harder for

people to perform unhealthy habits. Smoking bans in

English pubs, for instance, made it more dicult for

people with strong smoking habits to light up while

drinking.

56

Having to leave the pub to smoke creates

friction, so smoking bans have generally increased

quit rates.

57

Bans on visible retail displays of cigarettes

also add friction by forcing potential purchasers to

remember to request cigarettes.

58

Such bans are espe-

cially likely to reduce impulsive tobacco purchases

59

by

removing environmental smoking cues.

60

Another way of adding friction to unhealthy options

is being tested in several cities in Switzerland. Policy-

makers are providing citizens with free electric bikes or

free ride-share schemes, but only after they hand over

their car keys for a few weeks. The idea is to add fric-

tion to existing car-use habits.

61

If successful, blocking

the automatic response of car driving will encourage

the use of other forms of transit that, in turn, may

becomehabitual.

Reducing friction. A variety of existing policies

successfully alter physical environments to promote

frictionless accessibility to healthy behaviors over

unhealthy ones. These include the availability of recre-

ational facilities, opportunities to walk and cycle, and

accessibility of stores selling fresh foods. The eective-

ness of such friction-easing interventions is clear: U.S.

residents with access to parks closer to home engage in

more leisure-time physical activity and have lower rates

of obesity.

62

Also, a bike-share program instituted in

London increased exercise rates.

63

Furthermore, in U.S.

metropolitan areas, fruit and vegetable consumption

was greater and obesity rates were lower among people

living closer to a supermarket with fresh foods.

64

The broad success of environmental reengineering

policies and changes to the physical environment makes

these prime strategies for large-scale habit change.

Nonetheless, these initiatives require political and citizen

support for healthy policies, tax codes, and zoning. We

suspect that such support will increase in the future,

given increasing recognition of lifestyle eects on

health.

65

To illustrate this potential, we note that building

Table 2. Three main components of habit-breaking interventions

and examples of implementation in practice

Principle Examples in practice

Cue disruption • Target recent movers with public transit price reductions

• Target new employees with health and wellness programs

• Reduce salience of cues to unhealthy choices; increase salience of healthy choices

(forexample, redesign cafeterias to show healthy items first)

Environmental reengineering Add friction to unhealthy behaviors

• Banning smoking in public places

• Banning visual reminders of cigarettes at point of purchase

• Changing building design regulations to increase prominence of stairways

• Explaining through public health communications how to alter personal environments to

reduce the salience of unhealthy foods

Remove friction from healthy behaviors

• Starting bike-share programs

• Bundling healthy food items in fast food menu selections (for example, apple slices as default

side item)

• Adding a fast check-out line in cafeterias for those purchasing healthy items only

Vigilant monitoring • Food labeling regulations that require visual cues on packaging to show serving sizes

• GPS technology triggers in smartphones and wearable devices that deliver nudges to adopt

healthful behaviors (for example, based on time to and location of fast food restaurants,

sending “don’t go” alerts or “order this not that” messaging)

a publication of the behavioral science & policy association 79

codes could make healthy options the default choice

by applying friction to elevator use so that stairways are

readily accessible and elevators less apparent. In addi-

tion, to add friction to unhealthy food choices and to

automate healthy ones, restaurants could provide food

bundles (for example, value meals) with healthy default

options (for example, apple slices instead of French

fries), and manufacturers could switch to packaging

formats that do not minimize apparent food quantity but

enable people to accurately assess the amount they are

eating.

66

To simplify consumer understanding of healthy

choices, restaurants and food companies could be rated

for health performance, much as they currently are

forsanitation.

67

Finally, on a more immediate, personal level, behavior

change interventions can provide individuals with the

knowledge and ability to reengineer their own personal

environments. The potential benefits of change in

microenvironments have been demonstrated clearly

with respect to healthy eating: People with a lower body

mass index were likely to have fruit available on their

kitchen counters, whereas those weighing more were

likely to have candy, sugary cereal, and nondiet soft

drinks.

68

And demonstrating that food choice is based in

part on high visibility, studies that have directly manipu-

lated the visibility and convenience of foods reveal that

people tend to consume easily accessible, frictionless

options rather than inaccessible, high-friction choices.

69

Another approach to reduce the friction to healthy

choices is allowing people to preorder food, enabling

them to make healthier choices outside of the influence

of the evocative smells and visual temptations of school

or work cafeterias.

70

In summary, it is sound policy to

empower individuals to reengineer their immediate

environments to increase access to contexts promoting

healthy behaviors and avoid contexts of unhealthy ones.

Vigilant Monitoring

Inhibition of habits through vigilant monitoring is a final

habit-breaking strategy that increases awareness of the

cues that trigger unhealthy habits and provides oppor-

tunities to inhibit them (see Table 2). Unlike cue disrup-

tion and environmental reengineering, which focus

primarily on harnessing automatic processes, vigilant

monitoring combines conscious thoughts of control

with automatic processes. This works as a sort of cogni-

tive override process.

Vigilant monitoring is the strategy that people are

most likely to use to control unwanted habits in daily

life.

71

By thinking, “Don’t do it,” and monitoring carefully

for slipups, participants in several studies were more

eective at curbing bad habits such as eating junk food,

smoking, and drinking too much than when they used

other strategies (for example, distracting themselves).

These researchers subsequently brought this strategy

into the lab to study it under controlled conditions using

a word-pair task. Vigilant monitoring proved to control

habits by heightening inhibitory cognitive control

processes at critical times when bad habits were most

likely—that is, by helping people combat their automatic

responses before they happened.

Vigilance may be most eective when paired with

strategies that also make healthy options cognitively

accessible, so the desired action is salient in contexts

in which people have an unhealthy habit. Thus, after

people formed implementation intentions to eat apples

or another healthy snack in a context in which they

typically ate unhealthy ones like candy bars, the healthy

behavior automatically came to mind when that context

was encountered in the future.

23

Facilitating vigilant monitoring for individuals.

Because vigilant inhibition is eortful to sustain, it could

be facilitated by GPS technology in smartphones and

wearable devices that enable reminders or nudges, to

be delivered on the basis of physical proximity to loca-

tions linked with unwanted habits (for example, fast

food restaurants). Given that these sensor devices can

detect daily activities such as eating and watching TV,

72

they could potentially deliver response-timed elec-

tronic prompts at just the right time to inhibit acting on

unhealthy habits.

In policy applications, vigilant monitoring of

unwanted behaviors can be adapted into interventions

through reminders to control unwanted habits. These

could be conveyed indirectly with simple changes to

product packaging, such as pictures illustrating the

amount of a single-serving portion on a bag of Oreos.

Or serving cues could be embedded within the food

itself, perhaps by inserting a dierent-colored cookie

at a certain point in the package to trigger a “stop here”

response.

73

More directly, point-of-choice prompts

involving signs or other reminders of desired actions

might be used in situations where people usually

respond in other ways. For example, signs to promote

stair climbing over elevator and escalator use in public

80 behavioral science & policy | volume 2 issue 1 2016

settings have shown modest but consistent success.

74

Because such reminders may become less eective

over time, except among people who perform the

behavior suciently often so that it becomes habitual,

75

it may be necessary to diversify such visual cues over

time to help retrigger vigilance.

Framework for Policymakers

Habit-based interventions are tailored to the mecha-

nisms of action, ensuring that the patterning of behavior

is optimal to create healthy habits and impede unhealthy

ones. The principles and tactics outlined here can be

applied at varying levels of scale, with some best suited

to individual self-change, others to community health

interventions, and still others to state and national poli-

cies. So, which of the ideas we have discussed in this

article scale best for public policy?

For Habit Formation

Public policy regulations can eectively make healthy

responses salient (for example, funding bike paths and

bike-share programs) and tie desired behaviors to stable

contexts (for example, public health communications

that link reminders to change smoke detector batteries

to the start and end of daylight savings time, medical

compliance communications that piggyback medication

intake onto an existing habit). At its core, habit forma-

tion is promoted through the various public policies

that incentivize repeated healthy responses in stable

contexts (for example, free public transit days; Supple-

mental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits limited to

the purchase of high nutrition, low-energy-dense foods

such as spinach and carrots).

For Habit Disruption

Policymakers can initiate legislation to reduce the pres-

ence of unhealthy habit cues (for example, funding the

reengineering of school cafeterias) and can also harness

context disruption (for example, free public transit

programs for recent movers). The success of anti-

smoking campaigns provides a model for how this can

work. Among the many dierent policies used to control

tobacco, the most successful were the ones that added

friction to smoking, such as increasing tobacco prices,

instituting smoking bans in public places, and removing

tobacco and advertising from point-of-purchase

displays.

9

As would be anticipated given the habitual,

addictive nature of smoking, warning labels on packets

have limited impact,

65

and mass media campaigns have

generally only been eective in conjunction with the

more friction-inducing interventions listed above.

76,77

Traditional policy tools such as tax breaks are a

generally useful tool for health behavior change. Linking

tax breaks for health insurers to policyholders’ health

habits can create incentives for companies and other

large institutions to apply habit-change principles in

more localized ways. Tax policies can also drive habit

change by adding friction to unhealthy consumer

choices (for example, taxes on sugared soft drinks,

tobacco, and fast food).

For many everyday health challenges, people are

likely to benefit from both forming healthy habits and

disrupting unhealthy ones. Thus, multicomponent

interventions that include distinct elements designed

to break existing habits and support the initiation

and maintenance of new ones will be needed. For

example, an intervention to increase fruit and vegetable

consumption among students in a school cafeteria

could simultaneously reengineer the choice environ-

ment to disrupt their existing habits to eat processed

snacks (for example, by moving such snacks to the

back of displays and fruit to the front) and to form new

habits (for example, by providing discounts to incen-

tivize the selection and consumption of healthful foods,

or express checkout lanes for people making healthy

purchases). However, habit disruption is, of course,

irrelevant in shifting, changing environments and for

people who do not have a history of acting in a given

domain or circumstance. Thus, habit interruptions have

more limited use than the broadly applicable habit

formationprinciples.

Conclusion

Strategies that accelerate habit formation and promote

maintenance are especially important for health inter-

ventions, given that many benefits of healthy behaviors

are not evident immediately but instead accrue gradually

with repetition. Thus, interventions that are successful

at promoting short spurts of exercise or a sporadi-

cally healthful diet will provide little protection against

the risks of lifestyle diseases associated with inactivity

and overeating. The habit-based strategies outlined in

a publication of the behavioral science & policy association 81

this article provide policymakers and behavior change

specialists with important insights into the mecha-

nisms by which people can create sustainable healthy

lifestyles.

author aliation

Wood, Dornsife Department of Psychology and Marshall

School of Business, University of Southern California;

Neal, Catalyst Behavioral Sciences and Center for

Advanced Hindsight, Duke University. Corresponding

author’s e-mail: wendy[email protected]

author note

Preparation of this article was supported by a grant to

Wendy Wood from the John Templeton Foundation.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the

authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the

John Templeton Foundation. The authors thank Hei

Yeung Lam and Drew Kogon for their help with the

references.

References

1. Stables, G. J., Subar, A. F., Patterson, B. H., Dodd, K.,

Heimendinger, J., Van Duyn, M. A. S., & Nebeling, L. (2002).

Changes in vegetable and fruit consumption and awareness

among US adults: Results of the 1991 and 1997 5 A Day for

Better Health Program surveys. Journal of the American

Dietetic Association, 102, 809–817. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

S0002-8223(02)90181-1

2. Casagrande, S. S., Wang, Y., Anderson, C., & Gary, T. L. (2007).

Have Americans increased their fruit and vegetable intake?

The trends between 1988 and 2002. American Journal of

Preventive Medicine, 32, 257–263. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.

amepre.2006.12.002

3. Moore, L. V., & Thompson, F. E. (2015, July 10). Adults meeting

fruit and vegetable intake recommendations—United States,

2013. Morbity and Mortality Weekly Report, 64, 709–713.

http://www.cdc.gov/MMWR/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6426a1.

htm

4. Vandelanotte, C., Spathonis, K. M., Eakin, E. G., & Owen, N.

(2007). Website-delivered physical activity interventions:

A review of the literature. American Journal of Preventive

Medicine, 33, 54–64. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.

amepre.2007.02.041

5. Fjeldsoe, B., Neuhaus, M., Winkler, E., & Eakin, E. (2011).

Systematic review of maintenance of behavior change

following physical activity and dietary interventions. Health

Psychology, 30, 99–109. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0021974

6. Mantzari, E., Vogt, F., Shemilt, I., Wei, Y., Higgins, J. P., &

Marteau, T. M. (2015). Personal financial incentives for

changing habitual health-related behaviors: A systematic

review and meta-analysis. Preventive Medicine, 75, 75-85.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.03.001

7. Volpp, K. G., John, L. K., Troxel, A. B., Norton, L., Fassbender,

J., & Loewenstein, G. (2008). Financial incentive–based

approaches for weight loss: A randomized trial. Journal of the

American Medical Association, 300, 2631–2637. http://dx.doi.

org/10.1001/jama.2008.804

8. Charness, G., & Gneezy, U. (2009). Incentives to exercise.

Econometrica, 77, 909–931. http://dx.doi.org/10.3982/

ECTA7416

9. Volpp, K. G., Troxel, A. B., Pauly, M. V., Glick, H. A., Puig, A.,

Asch, D. A., . . . Audrain-McGovern, J. (2009). A randomized,

controlled trial of financial incentives for smoking cessation.

New England Journal of Medicine, 360, 699–709. http://dx.doi.

org/10.1056/NEJMsa0806819

10. King, A. C., Hekler, E. B., Castro, C. M., Buman, M. P., Marcus,

B. H., Friedman, R. H., & Napolitano, M. A. (2014). Exercise

advice by humans versus computers: Maintenance eects

at 18 months. Health Psychology, 33, 192–196. http://dx.doi.

org/10.1037/a0030646

11. Adriaanse, M. A., Kroese, F. M., Gillebaart, M., & De Ridder,

D. T. (2014). Eortless inhibition: Habit mediates the relation

between self-control and unhealthy snack consumption.

Frontiers in Psychology, 5, Article 444. http://dx.doi.

org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00444

12. Galla, B. M., & Duckworth, A. L. (2015). More than resisting

temptation: Beneficial habits mediate the relationship

between self-control and positive life outcomes. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 109, 508–525. http://dx.doi.

org/10.1037/pspp0000026

13. Wilson, L. M., Tang, E. A., Chander, G., Hutton, H. E., Odelola, O.

A., Elf, J. L., . . . Apelberg, B. J. (2012). Impact of tobacco control

interventions on smoking initiation, cessation, and prevalence: A

systematic review. Journal of Environmental and Public Health,

2012, Article 961724. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2012/961724

14. Tricomi, E., Balleine, B. W., & O’Doherty, J. P. (2009). A specific

role for posterior dorsolateral striatum in human habit learning.

European Journal of Neuroscience, 29, 2225–2232. http://

dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06796.x

15. Neal, D. T., Wood, W., Wu, M., & Kurlander, D. (2011). The

pull of the past: When do habits persist despite conflict with

motives? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37, 1428–

1437. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0146167211419863

16. Lin, P.-Y., Wood, W., & Monterosso, J. (2016). Healthy eating

habits protect against temptations. Appetite, 103, 432–440.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2015.11.011

17. Neal, D. T., Wood, W., Labrecque, J. S., & Lally, P. (2012). How

do habits guide behavior? Perceived and actual triggers of

habits in daily life. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology,

48, 492–498. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2011.10.011

18. Thaler, R. H., Sunstein, C. R., & Balz, J. P. (2012). Choice

architecture. In E. Shafir (Ed.), The behavioral foundations

of public policy (pp. 428–439). Princeton, NJ: Princeton

University Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2536504

19. Johnson, E. J., Shu, S. B., Dellaert, B. G. C., Fox, C., Goldstein,

D. G., Häubl, G., . . . Weber, E. U. (2012). Beyond nudges: Tools

of a choice architecture. Marketing Letters, 23, 487–504.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11002-012-9186-1

20. Sherif, M. (1936). The psychology of social norms. Oxford,

England: Harper.

21. Salmon, S. J., Fennis, B. M., de Ridder, D. T., Adriaanse, M. A.,

& de Vet, E. (2014). Health on impulse: When low self-control

promotes healthy food choices. Health Psychology, 33,

103–109. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0031785

22. Gollwitzer, P. M. (1999). Implementation intentions: Strong

eects of simple plans. American Psychologist, 54, 493–503.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.54.7.493

23. Adriaanse, M. A., Gollwitzer, P. M., de Ridder, D. T. D., de

Wit, J. B. F., & Kroese, F. M. (2011). Breaking habits with

implementation intentions: A test of underlying processes.

Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37, 502–513. http://

dx.doi.org/10.1177/0146167211399102

82 behavioral science & policy | volume 2 issue 1 2016

24. Wood, W., & Rünger, D. (2016). The psychology of habit.

Annual Review of Psychology, 67, 289–314. http://dx.doi.

org/10.1146/annurev-psych-122414-033417

25. Ji, M. F., & Wood, W. (2007). Purchase and consumption

habits: Not necessarily what you intend. Journal of Consumer

Psychology, 17, 261–276. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

S1057-7408(07)70037-2

26. Verhoeven, A. A. C., Adriaanse, M. A., Evers, C., & de Ridder,

D. T. D. (2012). The power of habits: Unhealthy snacking

behaviour is primarily predicted by habit strength. British

Journal of Health Psychology, 17, 758–770. http://dx.doi.

org/10.1111/j.2044-8287.2012.02070.x

27. Neal, D. T., Wood, W., & Drolet, A. (2013). How do people

adhere to goals when willpower is low? The profits (and

pitfalls) of strong habits. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 104, 959–975. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0032626

28. Lally, P., van Jaarsveld, C. H. M., Potts, H. W. W., & Wardle, J.

(2010). How are habits formed: Modelling habit formation in

the real world. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40,

998–1009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.674

29. Armitage, C. J. (2005). Can the theory of planned

behavior predict the maintenance of physical activity?

Health Psychology, 24, 235–245. http://dx.doi.

org/10.1037/0278-6133.24.3.235

30. Kaushal, N., & Rhodes, R. E. (2015). Exercise habit formation

in new gym members: A longitudinal study. Journal of

Behavioral Medicine, 38, 652–663. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/

s10865-015-9640-7

31. Neal, D. T., Vujcic, J., Hernandez, O., & Wood, W. (2015).

Creating hand-washing habits: Six principles for creating

disruptive and sticky behavior change for hand washing with

soap. Unpublished manuscript, Catalyst Behavioral Science,

Miami, FL.

32. Allcott, H., & Rogers, T. (2014). The short-run and long-run

eects of behavioral interventions: Experimental evidence

from energy conservation. American Economic Review, 104,

3003–3037. http://dx.doi.org/10.1257/aer.104.10.3003

33. Tappe, K., Tarves, E., Oltarzewski, J., & Frum, D. (2013). Habit

formation among regular exercisers at fitness centers: An

exploratory study. Journal of Physical Activity & Health, 10,

607–613.

34. Brooks, T. L., Leventhal, H., Wolf, M. S., O’Conor, R.,

Morillo, J., Martynenko, M., Wisnivesky, J. P., & Federman,

A. D. (2014). Strategies used by older adults with asthma for

adherence toinhaled corticosteroids. Journal of General

Internal Medicine, 29, 1506–1512. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/

s11606-014-2940-8

35. Rogers, T., Milkman, K. L., John, L. K., & Norton, M. I. (2015).

Beyond good intentions: Prompting people to make plans

improves follow-through on important tasks. Behavioral

Science & Policy, 1(2), 33–41.

36. Orbell, S., & Verplanken, B. (2010). The automatic component

of habit in health behavior: Habit as cue-contingent

automaticity. Health Psychology, 29, 374–383. http://dx.doi.

org/10.1037/a0019596

37. Judah, G., Gardner, B., & Aunger, R. (2013). Forming a flossing

habit: An exploratory study of the psychological determinants

of habit formation. British Journal of Health Psychology, 18,

338–353. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8287.2012.02086.x

38. Labrecque, J. S., Wood, W., Neal, D. T., & Harrington, N.

(2016). Habit slips: When consumers unintentionally resist

new products. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science.

Advance online publication. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/

s11747-016-0482-9

39. Phillips, A. L., Leventhal, H., & Leventhal, E. A. (2013). Assessing

theoretical predictors of long-term medication adherence:

Patients’ treatment-related beliefs, experiential feedback and

habit development. Psychology & Health, 28, 1135–1151.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2013.793798

40. Lally, P., & Gardner, B. (2013). Promoting habit formation.

Health Psychology Review, 7(Suppl. 1), S137–S158. http://

dx.doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2011.603640

41. Fishbach, A., & Trope, Y. (2005). The substitutability of

external control and self-control. Journal of Experimental

Social Psychology, 41, 256–270. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.

jesp.2004.07.002

42. DeRusso, A. L., Fan, D., Gupta, J., Shelest, O., Costa, R. M., &

Yin, H. H. (2010). Instrumental uncertainty as a determinant of

behavior under interval schedules of reinforcement. Frontiers

in Integrative Neuroscience, 4, Article 17. http://dx.doi.

org/10.3389/fnint.2010.00017

43. Burns, R. J., Donovan, A. S., Ackermann, R. T., Finch, E. A.,

Rothman, A. J., & Jeery, R. W. (2012). A theoretically grounded

systematic review of material incentives for weight loss:

Implications for interventions. Annals of Behavioral Medicine,

44, 375–388. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12160-012-9403-4

44. Gneezy, U., Meier, S., & Rey-Biel, P. (2011). When and why

incentives (don’t) work to modify behavior. The Journal of

Economic Perspectives, 25, 191–209. http://dx.doi.org/10.1257/

jep.25.4.191

45. Lally, P., Chipperfield, A., & Wardle, J. (2008). Healthy habits:

Ecacy of simple advice on weight control based on a

habit-formation model. International Journal of Obesity, 32,

700–707. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0803771

46. Gardner, B., Sheals, K., Wardle, J., & McGowan, L. (2014).

Putting habit into practice, and practice into habit: A process

evaluation and exploration of the acceptability of a habit-based

dietary behaviour change intervention. International Journal of

Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 11, Article 135. http://

dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12966-014-0135-7

47. Carels, R. A., Burmeister, J. M., Koball, A. M., Oehlhof, M. W.,

Hinman, N., LeRoy, M., . . . Gumble, A. (2014). A randomized

trial comparing two approaches to weight loss: Dierences in

weight loss maintenance. Journal of Health Psychology, 19,

296–311. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1359105312470156

48. Ford, A. L., Bergh, C., Södersten, P., Sabin, M. A., Hollinghurst,

S., Hunt, L. P., & Shield, J. P. (2010). Treatment of childhood

obesity by retraining eating behaviour: Randomised controlled

trial. British Medical Journal, 340, Article b5388. http://dx.doi.

org/10.1136/bmj.b5388

49. Walker, I., Thomas, G. O., & Verplanken, B. (2015). Old habits

die hard: Travel habit formation and decay during an oce

relocation. Environment Behavior, 47, 1089–1106. http://dx.doi.

org/10.1177/0013916514549619

50. Bouton, M. E., Todd, T. P., Vurbic, D., & Winterbauer, N. E.

(2011). Renewal after the extinction of free operant behavior.

Learning & Behavior, 39, 57–67. http://dx.doi.org/10.3758/

s13420-011-0018-6

51. Thrailkill, E. A., & Bouton, M. E. (2015). Extinction of chained

instrumental behaviors: Eects of procurement extinction on

consumption responding. Journal of Experimental Psychology:

Animal Learning and Cognition, 41, 232–246. http://dx.doi.

org/10.1037/xan0000064

52. Heatherton, T. F., & Nichols, P. A. (1994). Personal accounts

of successful versus failed attempts at life change. Personality

and Social Psychology Bulletin, 20, 664–675. http://dx.doi.

org/10.1177/0146167294206005

53. Verplanken, B., Walker, I., Davis, A., & Jurasek, M. (2008).

Context change and travel mode choice: Combining the

habit discontinuity and self-activation hypotheses. Journal

of Environmental Psychology, 28, 121–127. http://dx.doi.

org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2007.10.005

54. Thøgersen, J. (2012). The importance of timing for breaking

commuters’ car driving habits. Collegium: Studies Across

a publication of the behavioral science & policy association 83

Disciplines in the Humanities and Social Sciences, 12,

130–140. Retrieved from https://helda.helsinki.fi/bitstream/

handle/10138/34227/12_08_thogersen.pdf?sequence=1

55. Wood, W., Tam, L., & Witt, M. G. (2005). Changing circumstances,

disrupting habits. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,

88, 918–933. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.88.6.918

56. Orbell, S., & Verplanken, B. (2010). The automatic component

of habit in health behavior: Habit as cue-contingent

automaticity. Health Psychology, 29, 374–383. http://dx.doi.

org/10.1037/a0019596

57. Lemmens, V., Oenema, A., Knut, I. K., & Brug, J. (2008).

Eectiveness of smoking cessation interventions among

adults: A systematic review of reviews. European Journal of

Cancer Prevention, 17, 535–544. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/

CEJ.0b013e3282f75e48

58. Wakefield, M., Germain, D., & Henriksen, L. (2008).

The eect of retail cigarette pack displays on impulse

purchase. Addiction, 103, 322–328. http://dx.doi.

org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02062.x

59. Robertson, L., McGee, R., Marsh, L., & Hoek, J. (2014). A

systematic review on the impact of point-of-sale tobacco

promotion on smoking. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 17, 2–17.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntu168

60. Kirchner, T. R., Cantrell, J., Anesetti-Rothermel, A., Ganz, O.,

Vallone, D. M., & Abrams, D. B. (2013). Geospatial exposure

to point-of-sale tobacco: Real-time craving and smoking-

cessation outcomes. American Journal of Preventive Medicine,

45, 379–385. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2013.05.016

61. Lourenço, J. S., Ciriolo, E., Almeida, S. R., & Troussard, X.

(2016). Behavioural insights applied to policy: European

Report 2016 (Report No. EUR 27726 EN). http://dx.doi.

org/10.2760/903938

62. Roubal, A. M., Jovaag, A., Park, H., & Gennuso, K. P. (2015).

Development of a nationally representative built environment

measure of access to exercise opportunities. Preventing

Chronic Disease, 12, Article 140378. http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/

pcd12.140378

63. Woodcock, J., Tainio, M., Cheshire, J., O’Brien, O., &

Goodman, A. (2014). Health eects of the London bicycle

sharing system: Health impact modelling study. British Medical

Journal, 348, Article g425. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g425

64. Michimi, A., & Wimberly, M. C. (2010). Associations of

supermarket accessibility with obesity and fruit and vegetable

consumption in the conterminous United States. International

Journal of Health Geographics, 9, Article 49. http://dx.doi.

org/10.1186/1476-072X-9-49

65. Kohl, H. W., Craig, C. L., Lambert, E. V., Inoue, S., Alkandari, J.

R., Leetongin, G., . . . Lancet Physical Activity Series Working

Group. (2012). The pandemic of physical inactivity: Global

action for public health. The Lancet, 380, 294–305. http://

dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60898-8

66. Krishna, A. (2006). Interaction of senses: The eect of vision

versus touch on the elongation bias. Journal of Consumer

Research, 32, 557–566.

67. Cohen, D., Bhatia, R., Story, M. T., Wootan, M., Economos,

C. D., Van Horn, L., . . . Williams, J. D. (2013). Performance

standards for restaurants: A new approach to addressing the

obesity epidemic. Retrieved from http://www.rand.org/pubs/

conf_proceedings/CF313.html

68. Wansink, B., Hanks, A. S., & Kaipainen, K. (2015). Slim by

design: Kitchen counter correlates of obesity. Health Education

& Behavior. Advance online publication. http://dx.doi.

org/10.1177/1090198115610571

69. Rozin, P., Scott, S., Dingley, M., Urbanek, J. K., Jiang, H., &

Kaltenbach, M. (2011). Nudge to nobesity I: Minor changes in

accessibility decrease food intake. Judgment and Decision

Making, 6, 323–332.

70. Hanks, A. S., Just, D. R., & Wansink, B. (2013). Preordering

school lunch encourages better food choices by children.

JAMA Pediatrics, 167, 673–674. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/

jamapediatrics.2013.82

71. Quinn, J. M., Pascoe, A., Wood, W., & Neal, D. T. (2010).

Can’t control yourself? Monitor those bad habits. Personality

and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36, 499–511. http://dx.doi.

org/10.1177/0146167209360665

72. Chen, G., Ding, X., Huang, K., Ye, X., & Zhang, C. (2015,

February). Changing health behaviors through social

and physical context awareness. Paper presented at the

International Conference on Computing, Networking, and

Communications, Anaheim, CA.

73. Geier, A., Wansink, B., & Rozin, P. (2012). Red potato chips:

Segmentation cues substantially decrease food intake. Health

Psychology, 31, 398–401.

74. Soler, R. E., Leeks, K. D., Buchanan, L. R., Brownson, R. C.,

Heath, G. W., Hopkins, D. H., & Task Force on Community

Preventive Services. (2010). Point-of-decision prompts to

increase stair use. American Journal of Preventive Medicine,

38(2, Suppl.), S292–S300. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.

amepre.2009.10.028

75. Tobias, R. (2009). Changing behavior by memory aids:

Asocialpsychological model of prospective memory

and habitdevelopment tested with dynamic field data.

Psychological Review, 116, 408–438. http://dx.doi.org/

10.1037/a0015512

76. Bala, M., Strzeszynski, L., & Cahill, K. (2008). Mass media

interventions for smoking cessation in adults. Cochrane

Database of Systematic Reviews, 2013(6), Article CD004704.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004704.pub3

77. Levy, D. T., Chaloupka, F., & Gitchell, J. (2004). The eects of

tobacco control policies on smoking rates: A tobacco control

scorecard. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice,

10, 338–353.