Evaluation Paper 18/1: An

evaluation of our guaranteed

asset protection insurance

intervention

July 2018

EP 18/1: An evaluation of our guaranteed asset protection insurance intervention

We welcome views on this Evaluation Paper.

You can send them to us by email at evalu[email protected] or in writing to:

Economic and Financial Analysis Department, Strategy & Competition Division, Financial

Conduct Authority, 12 Endeavour Square, London, E20 1JN.

Authors

Jennifer Brauner, Lawrence Charles, Jasjit Sansoye and Lachlan Vass.

The authors work in the Economic and Financial Analysis Department at the FCA.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Sumit Agarwal for his academic peer review, advice, and guidance. We

would like to thank PwC Research for conducting the consumer survey.

All our publications are available to download from www.fca.org.uk. If you would like to

receive this paper in an alternative format, please call 020 7066 9644 or email

publications_graphics @fca.org.uk or write to Editorial and Digital team, Financial

Conduct Authority, 12 Endeavour Square, London, E20 1JN.

FCA Evaluation Papers

EP 18/1: An evaluation of our guaranteed asset protection insurance intervention

Executive summary 1

1 Why we are evaluating our guaranteed asset protection insurance

intervention 6

2 Our evaluation approach 10

3 Results: Market context analysis 17

4 Results: Sales analysis 22

5 Results: Price analysis 30

6 Results: Consumer survey findings 38

7 Results: Overall effects 49

8 Lessons learned 55

Contents

EP 18/1: An evaluation of our guaranteed asset protection insurance intervention

1

Evaluating the impact of our add-on guaranteed asset protection

(GAP) insurance market intervention

Evaluations inform our decision-making

Evaluation is part of our Mission’s decision-making framework. Testing the effectiveness

of our remedies helps us make better decisions.

In April 2018, we published Discussion Paper 18/3 on our proposed framework for post-

intervention impact evaluations. This is one of the ways we assess the impact of our

interventions. Post-intervention impact evaluations differ from other approaches as they

focus on quantifying the impact of our intervention.

1

In our 2018/19 Business Plan and the proposed evaluation framework, we said that we

would conduct 3 pilot evaluations to measure the impact of past interventions in a way

that controls for factors that may have influenced the market.

An evaluation of our September 2015 add-on

2

GAP insurance intervention is part of this

pilot.

What is GAP insurance?

GAP insurance is predominantly sold as an add-on when someone buys a vehicle. It

provides cover for a financial shortfall that can happen when:

• a customer’s vehicle is written off or stolen

• the motor insurance pay-out does not pay back its original value at purchase or the

remaining finance value (if the vehicle was bought on finance)

Our 2014 market study highlighted concerns about add-on GAP

insurance

In July 2014, we published the final report from our general insurance add-on products

market study. The study found consumer harm in the add-on GAP insurance market.

It

estimated total consumer overpayment for add-on GAP insurance of around £76 million

to £121 million a year (out of an estimated market size of £152 million).

We found that:

• vehicle sellers enjoyed a strong point-of-sale competitive advantage, meaning that

there was little or no pressure on sellers to lower the price

• a lack of information, including about alternative providers, prevented consumers

from being able to compare products

• many consumers did not know that they could buy GAP insurance separately

(‘standalone’) elsewhere, often at a lower price

1

The proposed framework sets out how we intend to use ex post impact evaluation (EPIEs), or post-

intervention impact evaluations, to assess the impact our interventions have had on consumers, firms and

markets. Evaluations feed back into our decision-making and how best to use our diagnostic and remedy tools.

2

Consumers can buy GAP insurance when buying a vehicle (add-on) or separately (standalone).

Executive summary

EP 18/1: An evaluation of our guaranteed asset protection insurance intervention

2

• as with other add-on products, consumers’ focus on the main product (in this case,

the vehicle) led to many buying add-on GAP insurance when they may not have

wanted and/or needed it

We introduced measures to deal with these concerns

To address this, we intervened in 2015 by:

• making it mandatory for vehicle sellers to provide sufficient information to consumers

• requiring a pause in the sale (‘deferred opt-in’), meaning that vehicle sellers can start

the sales process but cannot conclude the GAP insurance sale for 2 clear days

We believed that having both time and information would enable consumers to decide

whether they need GAP insurance, and to shop around if they do.

We expected:

• improved competition between add-on and standalone sellers

• better consumer outcomes during the purchasing process, including:

– an overall decrease in add-on GAP insurance sales, given our concern about

consumers buying, potentially, unsuitable add-on products

– more consumers shopping around and buying GAP insurance from standalone

providers

Evaluation relies on a range of evidence

Our evaluation follows the post-intervention impact evaluation framework’s high-level

approach and focusses on quantifying the impact of our intervention. We do this with

reference to our pre-intervention expectations, which are based on the cost benefit

analysis (CBA) in the GAP insurance Consultation Paper (CP14/29).

3

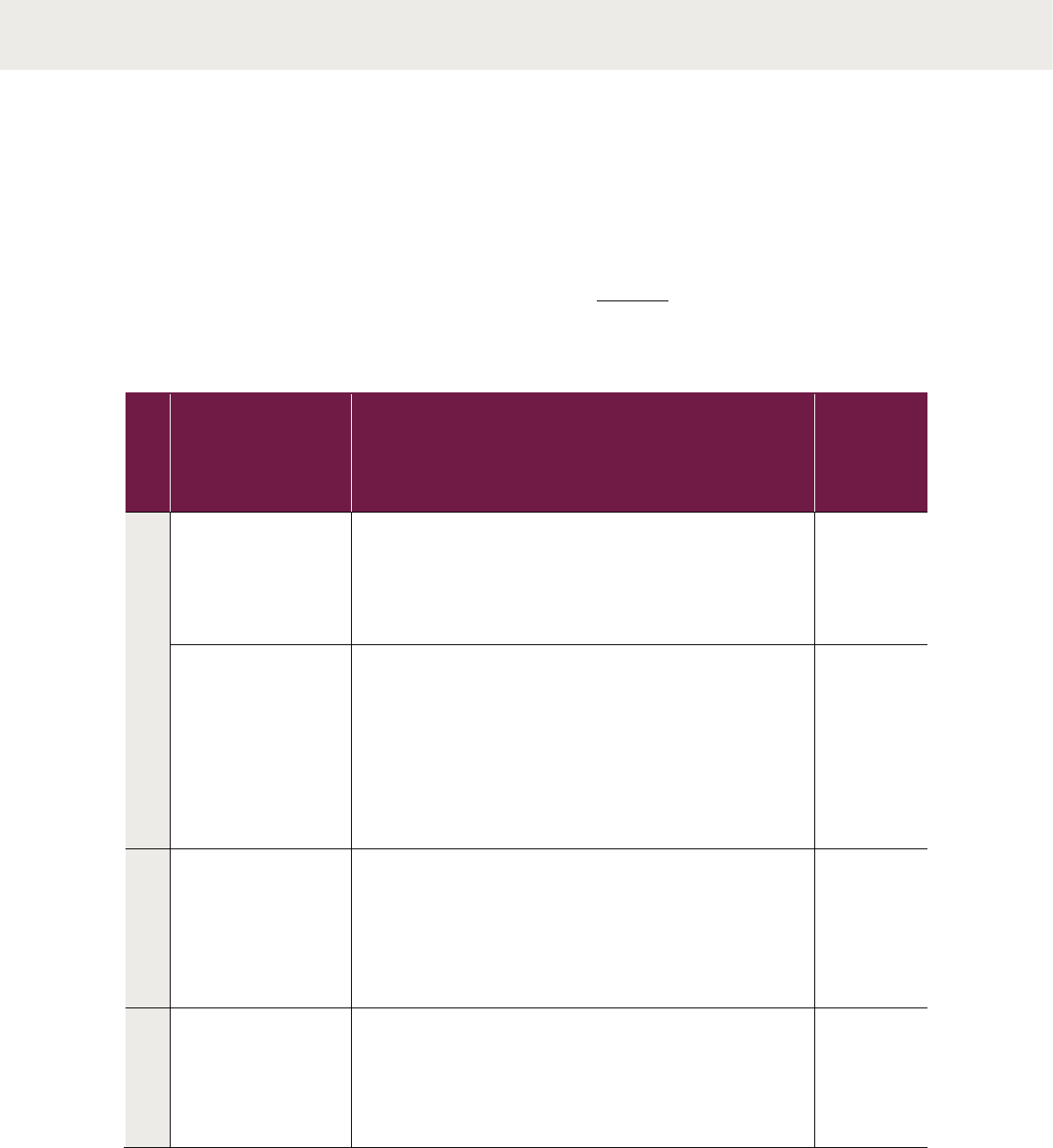

Figure 1 summarises our evaluation approach. We use a mix of transaction-level data,

consumer survey insights, other publicly available data, and insight from firms and trade

bodies to evaluate the impact of our intervention. To understand these data, we conduct

descriptive statistical and econometric analysis.

4

3

A post-intervention impact evaluation does not consider all aspects of the intervention or re-run a CBA.

For example, compliance costs are not a central focus of our analysis, though we do present some high-level

figures as provided to us by the National Franchised Dealers Association (NFDA).

4

We do this to diagnose the relationship between: a data series of interest (eg sales volumes); and a

range of factors that affect these data series at the same time. This approach helps us to isolate, given a level of

statistical confidence, the underlying correlation between many variables and the one of interest.

EP 18/1: An evaluation of our guaranteed asset protection insurance intervention

3

Figure 1: Our evaluation approach

Source: FCA

Our intervention has had a positive impact, but less than we

expected before intervening

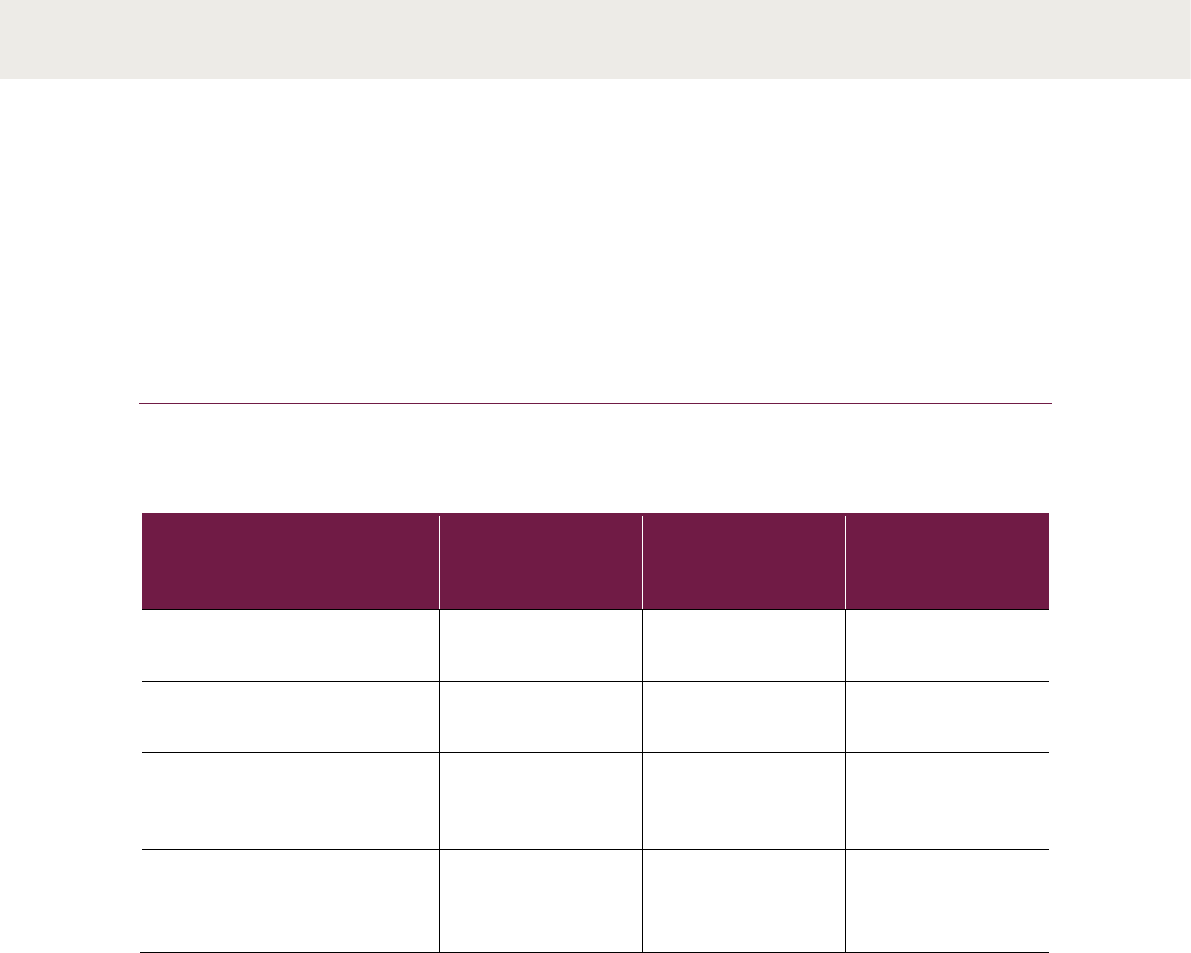

Overall, we find that our GAP insurance intervention has had a positive impact. We

summarise our main findings in Figure 2.

After our intervention, consumers are more engaged decision-makers and shopping

around has more than doubled. Add-on GAP insurance sales are 16% to 23% lower than

they would have been without our intervention. Some of the reduction in add-on sales is

accounted for by higher standalone sales, which have increased from 6% to 8% of all

GAP insurance sales. The evidence suggests that some consumers decide, on reflection,

not to go ahead with the purchase.

EP 18/1: An evaluation of our guaranteed asset protection insurance intervention

4

Figure 2: Our main results

Source: FCA

Our intervention has helped to reduce considerable harm in the market. We estimate that

there are around £26 million to £28 million of ongoing consumer benefits a year after our

intervention. This exceeds firms’ total costs of implementing our intervention, including a

one-off cost of £5 million to £8 million and an ongoing cost of £1 million a year.

Our intervention has achieved its objectives, although not by as much as we expected.

Due to our intervention, we expected that:

• add-on sales would be up to 32.5% lower

• the share of sales of standalone would increase to up to 40%

• add-on prices would be up to 17% lower, with the price differential between add-on

and standalone narrowing

In particular, the impact on the standalone’s share of total sales and on add-on prices

has been much less pronounced than we expected.

Our findings are consistent with recent academic literature on demand-side interventions.

The literature indicates that although well-designed demand-side remedies can be

effective, their impacts tend to be modest. That said, even modest impacts can represent

significant gains for consumers.

EP 18/1: An evaluation of our guaranteed asset protection insurance intervention

5

Lessons learned

We view evaluations as an opportunity to learn from previous interventions and to feed

any insights into our current and future work.

The main lessons we learned from this evaluation are:

• This intervention had a far greater impact on sales than prices:

– In the case of sold products (goods or services a consumer was unaware of before

the seller introduced them) with a point-of-sale advantage, we are likely to reduce

total purchases, rather than diverting consumers to the non-point-of-sale market,

if we try to break the point-of-sale advantage

– Add-on sellers play an important role in introducing the product to buyers, so the

standalone market might be smaller in their absence

• Pre-intervention expectations should be based on a range of evidence. Our consumer

survey overstated the impact of the intervention on switching to the standalone

market, and underestimated the number of consumers who would make a more

considered purchase given the information and time to do so. This evaluation will

help to provide useful evidence when thinking about similar future interventions.

EP 18/1: An evaluation of our guaranteed asset protection insurance intervention

6

This section provides an overview of the intervention that we evaluate in this report. We

also set out the report’s scope and structure.

What is guaranteed asset protection (GAP) insurance?

GAP insurance is predominantly sold as an add-on when someone buys a vehicle. It

provides cover for a financial shortfall that can happen when:

• a customer’s vehicle is written off or stolen

• the motor insurance pay-out does not pay back its original value at purchase or the

remaining finance value (if the vehicle is bought on finance)

Figure 1.1 gives an example of how this might work.

Figure 1.1: How GAP insurance works

Source: FCA

GAP insurance is available for new, used, leased, business-owned and privately-bought

vehicles. Consumers can buy GAP insurance in connection with buying the vehicle (an

add-on buy) or separately (a standalone buy).

1 Why we are evaluating our

guaranteed asset protection

insurance intervention

EP 18/1: An evaluation of our guaranteed asset protection insurance intervention

7

Our concerns about add-on GAP insurance

In July 2014, we published our general insurance add-on products market study final

report, examining how selling general insurance products as an add-on to a primary

product affects competition.

The study found significant consumer harm in the add-on GAP insurance market.

We

concluded that consumers received poor value for money from this product.

We found that:

• on average, only £10 in every £100 paid in add-on GAP insurance premiums was paid

out in claims (ie an average ‘claims ratio’ of 10%, which was much lower than other

general insurance products

5

) between 2008-2012

6

,

• of the 5 add-on products considered, GAP insurance accounted for over half of the

estimated overpayment of add-on premiums

7

• consumers often bought add-on GAP insurance without having previously thought

about the product or shopped around for alternatives

8

We set out the following reasons for these findings:

• vehicle sellers enjoyed a strong point-of-sale competitive advantage, meaning that

there was little or no pressure on them to lower the price

• a lack of information, including about alternative providers, prevented consumers

from being able to compare products

• many consumers did not know that they could buy GAP insurance separately (as a

standalone), often at a significantly lower price, elsewhere

• similar to other add-on products, consumers’ focus on the main product (in this case,

the vehicle) led to many buying add-on GAP insurance when they may not have

wanted and/or needed it, with the add-on mechanism weakening consumers’

decision-making and engagement

9

We introduced measures to deal with these concerns

In 2015, we proposed 2 measures for add-on GAP insurance sellers to address the

identified harm:

1. Providing written information on GAP insurance (‘prescribed information’). This means

that add-on GAP insurance sellers (also known as distributors) must provide

information to potential buyers. This should encourage consumers to shop around,

including by advising them that they can buy the product elsewhere.

5

We used a conservative estimate of a competitive baseline using other general insurance products of

30% to 50% for a claims ratio. This was based on the 2012 average claims ratio for general insurance products

of 64%. Guaranteed Asset Protection insurance: a competition remedy, CP14/29, page 5

6

General insurance add-ons: Provisional findings of market study and proposed remedies, MS14/1, Table

5.1

7

£76 million to £121 million a year of the estimated total overpayment across five add-on insurance

products – travel, personal accident, home emergency, GAP, and gadget – of £108 million to £216 million a year).

GAP insurance was c.30% of the estimated add-on market size of the five products considered. General insurance

add-ons: Provisional findings of market study and proposed remedies, MS14/1, Table 6.1

8

General insurance add-ons: Provisional findings of market study and proposed remedies, MS14/1, page

56

9

General Insurance add-ons: Final report – confirmed findings of the market study, MS14/1

EP 18/1: An evaluation of our guaranteed asset protection insurance intervention

8

2. A pause in the sale (‘deferred opt-in’). This means that add-on GAP insurance sellers

can start the sales process but cannot conclude the GAP insurance sale for a set

amount of time (2 clear days)

10

. This gives consumers time to consider whether they

need the product at all and to shop around if they do.

These measures came into force on 1 September 2015. We believed that these tools

(time and information) would enable consumers to better assess whether they needed

GAP insurance and to shop around if they did.

As a result of our intervention, we expected:

• improved competition between add-on and standalone sellers of GAP insurance, with

standalone sales increasing relative to add-on sales

• better consumer outcomes, namely better-informed and more active decision-making

during the purchasing process

Assessing the impact of our GAP insurance intervention

As stated in our Mission, evaluation is a critical part of getting our interventions right.

Finding out what impact past interventions have had helps develop a strong evidence

base to guide our decisions.

11

These decisions can include which issues to prioritise and

how best to intervene to tackle harm.

We published a proposed framework outlining the way we measure the causal impact of

our interventions in April 2018. The framework explains:

• why we do post-intervention impact evaluations

12

• how we choose specific interventions to study

• how we ensure that our evaluations are robust, impartial, and, therefore, credible

This report follows the proposed approach to post-intervention impact evaluations, and is

one of three pilot evaluations. We chose it, in part, because the deferred opt-in element

was a novel measure to address the harm found in the FCA’s first market study.

The aim of this work is to understand:

1. the impact of the 2 measures

2. whether the intervention met its objectives

3. whether our pre-intervention cost benefit analysis (CBA) was able to accurately

capture the scale of the intervention’s impact

We focus on the main expected changes after our intervention. As set out in the

proposed evaluation framework, we do not re-run our pre-intervention CBA.

10

Consumers can make contact with the vehicle seller to complete the GAP insurance sale the day after it

is introduced.

11

We note that: i) FSMA requires us to have regard to the FCA exercising its functions as transparently as

possible when making policy; and ii) the principles for regulators under Legislative and Regulatory Reform Act

refer to regulators being both transparent and accountable.

12

We refer to post-intervention impact evaluations, or ex post impact evaluations, as ‘evaluations’ in this

report.

EP 18/1: An evaluation of our guaranteed asset protection insurance intervention

9

Report structure

We structure this report as follows:

• Section 2 sets out an economic framework for this evaluation

• Section 3 summarises the market context

• Sections 4 and 5 show what has happened to GAP insurance sales and prices,

respectively, before and after our intervention (with further details of the analysis set

out in the Technical Annex)

• Section 6 looks at possible explanations behind our findings through a consumer

survey (with further details of the analysis set out in Annex 2 and Annex 3)

• Section 7 comments on how overall outcomes have changed in the market after our

intervention

• Section 8 concludes with the main lessons that we have learned from this evaluation

EP 18/1: An evaluation of our guaranteed asset protection insurance intervention

10

This section sets out how we evaluate our GAP insurance intervention, including:

• how we expected our intervention to work

• the available evidence on compliance

• the pre-intervention expectations we tested to see how well our intervention has

worked

• the methods and data that we used to test these pre-intervention expectations

How we expect our intervention to work

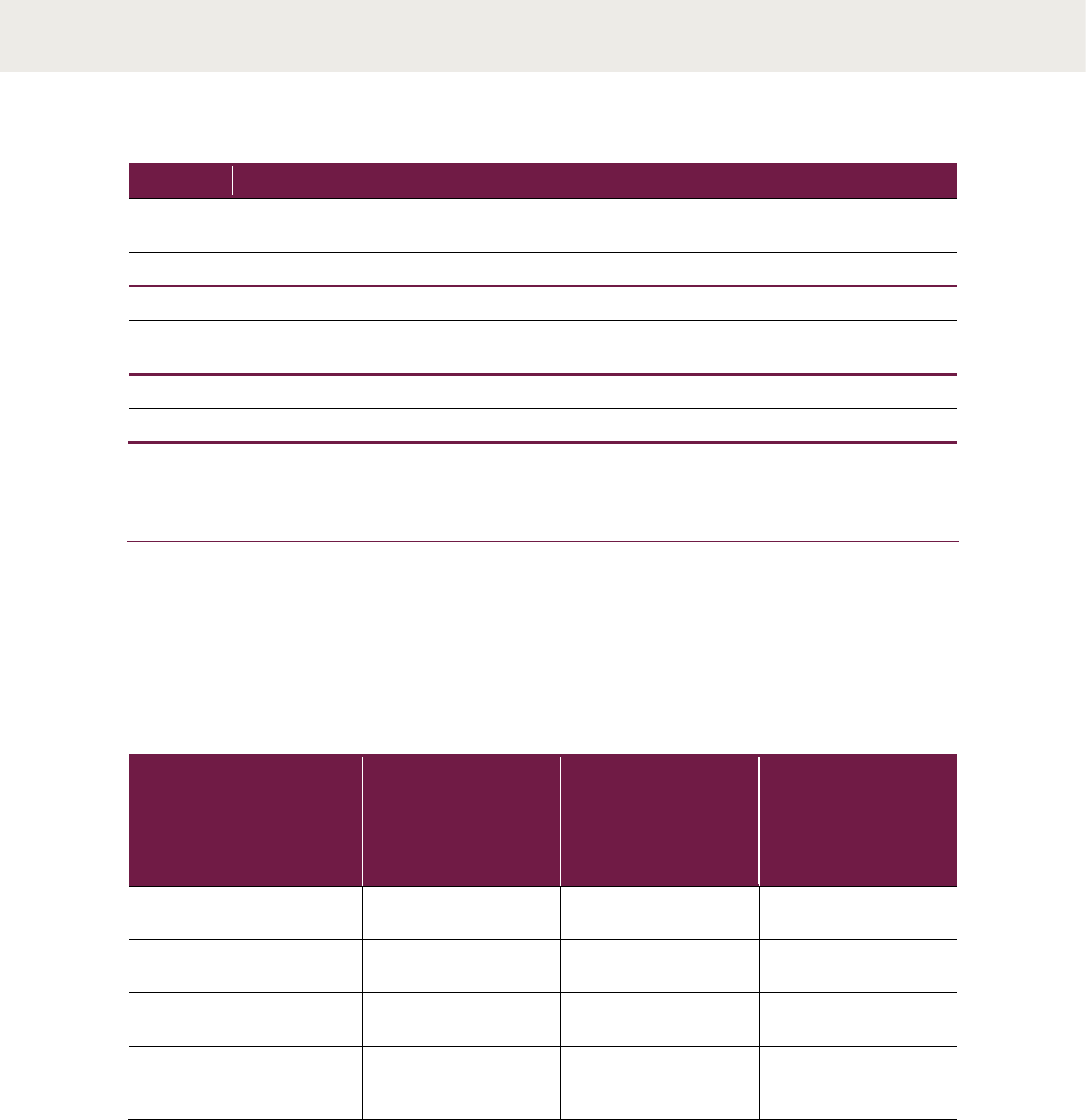

Figure 2.1 below sets out a causal chain of our GAP insurance intervention. A causal

chain, pathway, or logic model in this context describes the way that an intervention

addresses the identified market failure and reduces harm, leading to costs and benefits.

It does this by linking the intended intermediate and final outcomes with the intervention

inputs, activities, processes, and theoretical assumptions.

Figure 2.1 shows how our 2 measures achieve the intervention’s intended objectives.

2 Our evaluation approach

EP 18/1: An evaluation of our guaranteed asset protection insurance intervention

11

Figure 2.1: Causal chain of our 2015 GAP insurance intervention

Source: FCA

We have developed the evaluation approach, set out in this section, with reference to

Figure 2.1.

Evidence suggests that firms have implemented the measures

The first stage in Figure 2.1 is to consider the evidence on how far firms have broadly

complied with our intervention (process evaluation).

Evidence on compliance is important for supporting the causality in our analysis. But we

need to be careful how we interpret any lack of evidence or widespread non-compliance:

EP 18/1: An evaluation of our guaranteed asset protection insurance intervention

12

1. No knowledge about compliance: If we had no information on compliance and our

intervention appeared to have had no impact, it might be that nobody complied with

our intervention. Our conclusion about the intervention’s efficacy would then be based

on an incomplete evidence base and could be wrong.

2. Evidence of widespread non-compliance: Our estimates may understate

13

the

intervention’s potential impact, which could have been greater if more firms had

complied.

Our focus has been on establishing an evidence base on compliance so we can conclude

whether there is widespread non-compliance. We do not need to know whether there is

100% compliance to draw valid conclusions.

For the GAP insurance measures, we have considered a range of evidence, including:

• transaction-level data from firms, capturing dates to understand the deferred opt-in

measure’s implementation

• consumer survey insights, capturing both measures (see Section 6)

• existing work and knowledge within the FCA’s Supervision division

• informal engagement with firms and trade associations

Based on the available evidence, there does not appear to be widespread non-compliance

with our intervention. We are confident that our findings are not influenced, at least to a

material extent, by a lack of compliance.

We test our intervention against our expectations

To see how well our intervention has worked, we begin by testing outcomes against our

pre-intervention expectations (see Table 2.1). These are based on Figure 2.1.

But this analysis would not isolate the impact of the intervention. This is because we

need to assess how well our intervention has worked relative to what would have

happened without it. This is our counterfactual. For many reasons, it can be hard to

identify a counterfactual so we highlight these instances throughout the report. In these

cases, we provide reasons why we cannot establish a counterfactual, and an analysis of

how the market has changed over time (ie a non-causal analysis).

Having considered the effects above, we assess the benefits of our intervention and

compare them to the costs.

There are many other ways to measure the impact of an intervention beyond expressing

the costs and benefits in monetary terms. We base the pre-intervention expectations in

Table 2.1 on a series of measurable metrics, such as sales volumes, prices, and

consumers’ survey responses.

These metrics are helpful in assessing our intervention’s impact. But they should be

considered with this market in mind. If, for example, consumers are shopping around

more after our intervention, then this is likely to be a positive development. This does

not mean that, to its extreme, we think that all consumers should shop around in this

market (or any market). Throughout the report, we present our view of what has

13

It could overstate the intervention’s impact if the analytical approach did not control for other market-

wide changes that may have influenced, for example, add-on GAP insurance sales. We use econometric

techniques to isolate the impact of the intervention from other changes. Hence, we do not consider that this is a

likely outcome.

EP 18/1: An evaluation of our guaranteed asset protection insurance intervention

13

happened to these metrics. We do this to show whether observed changes after our

intervention are, in our view, positive or negative outcomes.

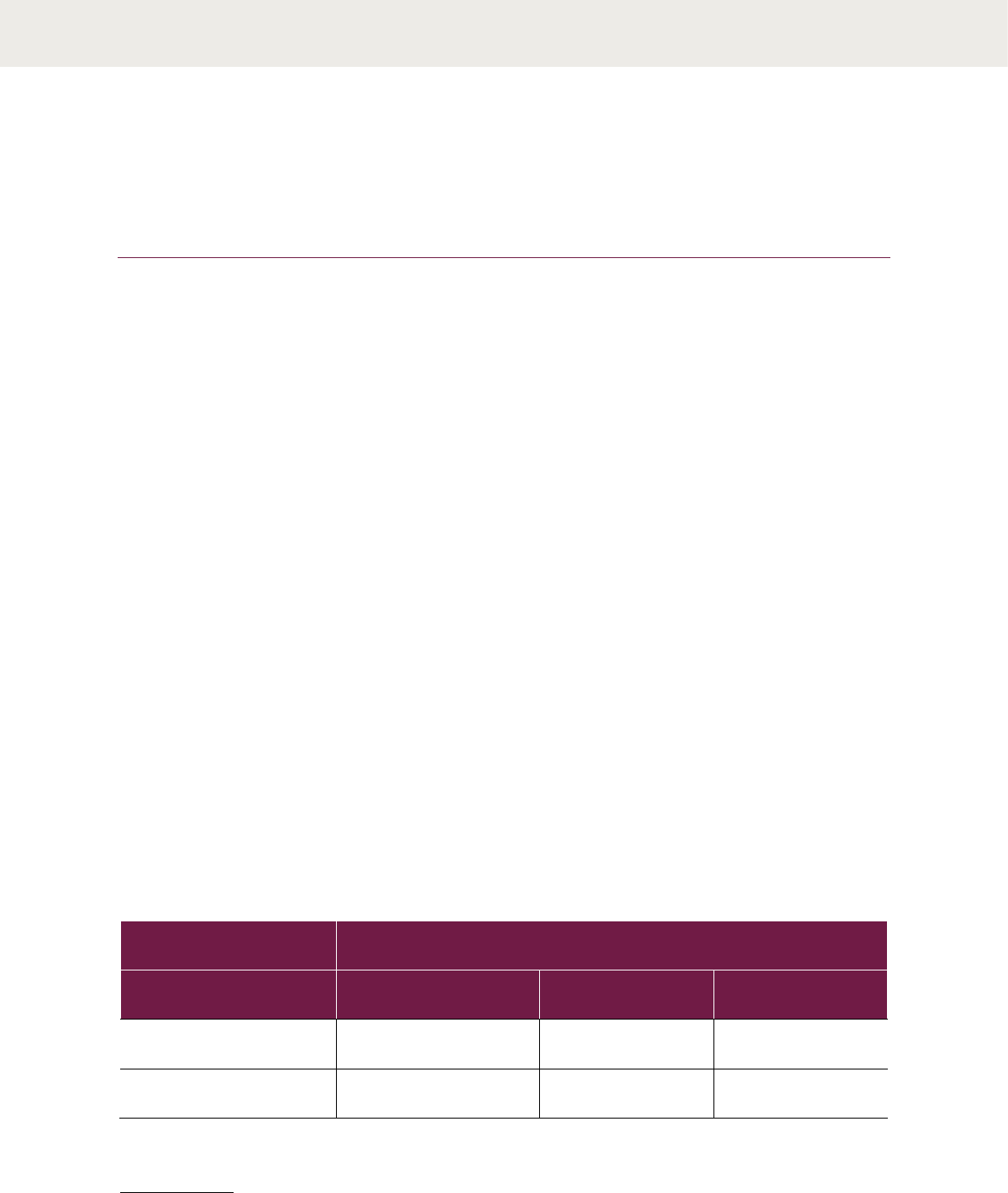

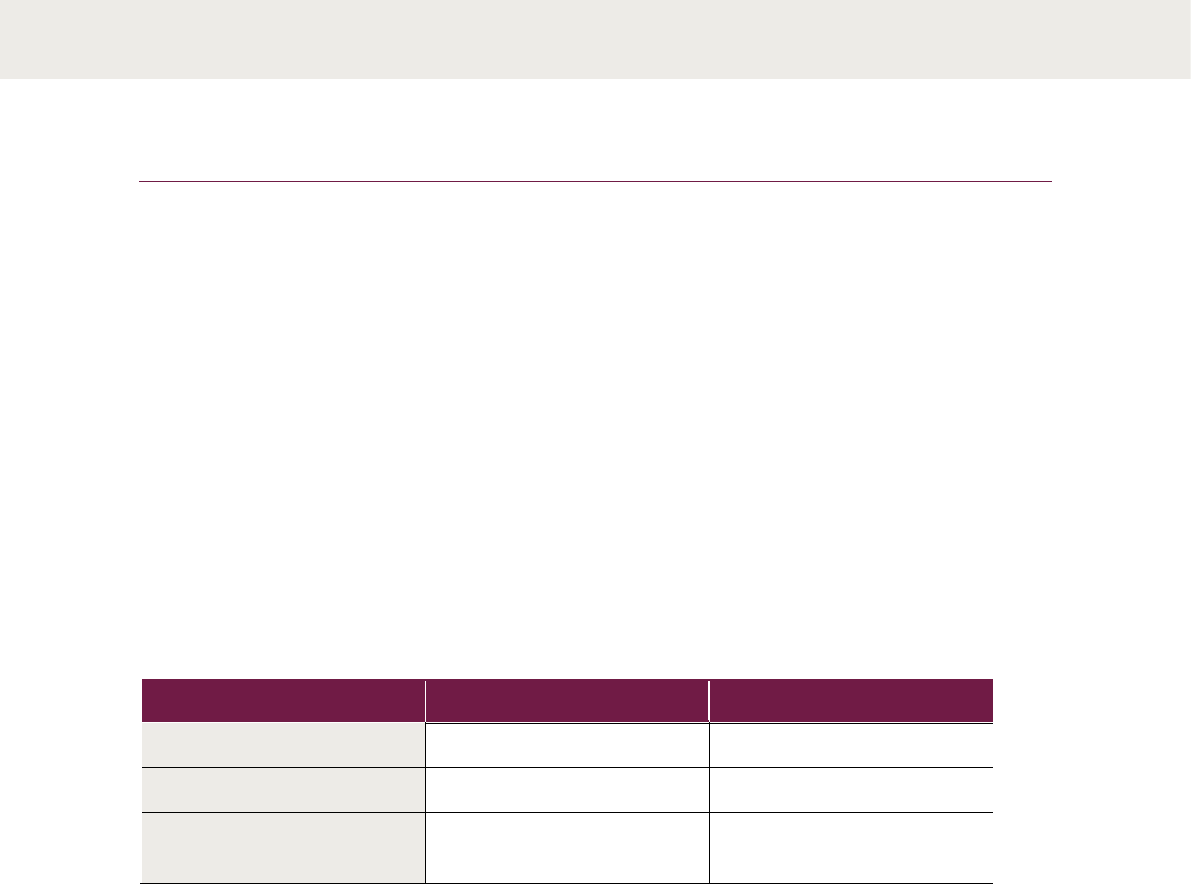

Table 2.1 sets out these pre-intervention expectations. Each row in Table 2.1 sets out:

• a question that, when answered, will help understand the extent to which our

intervention has worked

• our pre-intervention expectation, as informed by the CBA

• where, in this report, we present findings from our analysis to address the question

Table 2.1: Questions to answer and pre-intervention expectations to test

#

Question to

answer

Pre-intervention expectation

Report

section

where we

present

findings

1

Has the share of

add-on GAP

insurance sales to

total GAP insurance

sales decreased?

For a given number of GAP insurance sales (which was

based on the total number of car sales), the share of

add-on GAP insurance sales to total GAP insurance

sales falls.

This means that the share of standalone GAP insurance

sales increases.

4

2

Has the share of

add-on GAP

insurance sales to

car sales decreased?

Our pre-intervention CBA assumed, implicitly, that car

sales would remain constant.

Our intervention reduces add-on GAP insurance sales

(all other things being equal).

It does this in two ways:

• some people choose not to buy the product

• some people switch to standalone GAP insurance

14

Hence, the share of add-on GAP insurance sales to car

sales falls.

4

3

What has happened

to add-on and

standalone GAP

insurance prices?

The price of add-on GAP insurance either:

• does not change, or

• falls

15

because of lower demand after our

intervention, partly due to increased competition

from the standalone market

16

We set no pre-intervention expectation about the price

of standalone GAP insurance. Hence, it stays the same.

5

4

What has happened

to the average

17

GAP

insurance market

price?

This depends on what has happened to:

• the share of sales between add-on and standalone

GAP insurance

• prices in the individual segments

Based on pre-intervention expectations 1-3, the

average market price falls.

5

14

There were 600,000 add-on GAP insurance sales a year in our pre-intervention CBA. We estimated that:

i) 10% (60,000) sales would be lost due to add-on consumers no longer buying GAP insurance at all; and ii)

22.5% (135,000) add-on sales would move to the standalone market (under the ‘no price change’ scenario).

Hence, we estimated that 32.5% of add-on GAP insurance sales would no longer take place owing to our

intervention.

15

Our pre-intervention CBA set out two scenarios for add-on GAP insurance prices: i) no price change; and

ii) a fall in price of 16.7%.

16

Even if there are factors such as adverse selection that might lead to, on average, riskier purchasers

buying the product following our intervention.

17

In this report, we use the mean as our average measure unless we state otherwise.

EP 18/1: An evaluation of our guaranteed asset protection insurance intervention

14

5

What has happened

to consumers’

likelihood of

shopping around?

More people shop around (our pre-intervention CBA

estimated this at around 25% of add-on GAP insurance

consumers).

As a result, more people buy the cheaper standalone

GAP insurance.

6

6

What has happened

to consumer

engagement and

awareness of GAP

insurance after our

intervention?

Consumers are more aware of the product and engage

more with the purchasing process than they did

before.

18

6

7

What has happened

to consumer

understanding of the

add-on GAP

insurance product?

This was not explicit in the pre-intervention CBA. But it

is a matter of interest for the post-intervention analysis.

Add-on GAP insurance consumers understand the

product better than before. Product understanding no

longer differs materially between add-on and

standalone GAP insurance consumers.

6

8

What has happened

to consumer surplus

after our

intervention?

Consumer surplus

19

increases after our intervention,

relative to a ‘no intervention’ scenario.

In the pre-intervention CBA, we estimated this to be in

the region of £31 million to £54 million a year.

7

9

What has happened

to the average add-

on GAP insurance

claims ratio?

This was not explicit in the pre-intervention CBA. But it

is a matter of interest for the post-intervention analysis.

The add-on GAP insurance claims ratio increases.

This assumes that, all other things being equal, add-on

GAP insurance prices have fallen.

7

10

What were the costs

of complying with

the intervention?

Our pre-intervention CBA estimated the one-off

compliance costs to be between £2 million and £5

million. This was revised upwards after consultation to

fall between £5 million and £20 million, with minimal

ongoing compliance costs.

One-off compliance costs are in line with this revised

figure. Ongoing compliance costs are minimal.

7

Source: FCA

We use various methods and data to test these pre-intervention

expectations

The rest of this section sets out the different methods and data used to test the pre-

intervention expectations in Table 2.1.

Table 2.2 summarises the analytical methods we used for each pre-intervention

expectation (ticks indicate method used). We also use qualitative insights from

stakeholder (eg firms, trade bodies) engagement across most of the pre-intervention

expectations. This helps us understand the impact of our intervention from firms’

perspective and provides a valuable sense-check of our data analysis.

18

In our pre-intervention CBA, we considered that around 30% of add-on GAP insurance consumers who

did not shop around pre-intervention would do so post-intervention (based on their answers to a consumer

survey).

19

Consumer surplus is an economic measure of consumer benefit. It is the difference between the highest

price that a consumer is willing to pay and the price set by a firm for a good or service.

EP 18/1: An evaluation of our guaranteed asset protection insurance intervention

15

Table 2.2: How we address each pre-intervention expectation

Pre-

intervention

expectation

#

a) Descriptive

statistics

b) Econometric

analysis of firms’

data

c) Consumer survey

insights

1

✔

✔

2

✔

✔

3

✔

✔

4

✔

✔

5

✔

6

✔

7

✔

8

✔

9

✔

10

✔

Source: FCA

We explain these methods in further detail below.

a) Descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics provide context on what has happened in the market. They set out

overall trends and changes after our intervention. We can, therefore, see whether our

intervention is associated with changes in the market.

We collected GAP insurance transaction-level data from 41 firms (underwriters

20

and

distributors

21

) operating in the GAP insurance market.

22

These data covered the period

between September 2013 and August 2017 (ie two years either side of the intervention

date).

We also requested data on complete wheel protection (CWP) from firms selling

23

GAP

insurance. CWP is an add-on product that covers tyre and alloy wheel repair costs. We

did this to help build our counterfactual.

Our Technical Annex sets out further details about the data that we collected from firms

and how we have used them.

We summarise these data using summary statistics, charts, and tables throughout the

report. When doing this, we present any currency-based data (eg prices, economic

variables such as income) following an adjustment for inflation (ie in real terms).

24

20

Underwriters take on the insurance risk and meet the obligations of paying out if a consumer makes a

successful GAP insurance claim.

21

Distributors provide GAP insurance either directly to consumers (ie standalone) or to the final retail seller

(eg a vehicle dealership).

22

We did not request data from vehicle dealers, but we know which dealers sold GAP insurance in our

data. The Technical Annex outlines our approach in further detail.

23

Firms distributing or underwriting CWP policies.

24

When diagnosing how changes in price levels affect the consumption of a product or service, it is common

practice to strip out the effects of general inflation and express price changes in ‘real terms’. That is, changes in

EP 18/1: An evaluation of our guaranteed asset protection insurance intervention

16

b) Econometric analysis of firms’ data

Econometric analysis helps us diagnose whether there is evidence that our intervention

has led to changes in the market.

We use a specific type of regression model to help identify our intervention’s causal

impact on sales and prices. A difference-in-difference (‘DiD’) model compares how trends

in outcomes change between ‘treated’ (ie affected by an intervention) and ‘untreated’ (ie

unaffected by an intervention) groups over a period relevant to the intervention.

Unobserved factors might affect the outcome. But, if they do not affect trends in the

outcome, then the trends for both groups in the absence of a policy will be the same. It

is a well-known, often-used econometric approach when evaluating policy

interventions.

25

We use CWP as our untreated product to compare to add-on GAP insurance, which is the

treated product. CWP was not affected by our intervention (see further explanation in the

Technical Annex).

c) Insights from consumer surveys

The results from consumer surveys help us to understand why we see the outcomes from

the analytical approaches set out in a) and b).

We build on answers to GAP insurance-specific questions in our 2017 Financial Lives

Survey by presenting findings from a consumer survey that we commissioned as part of

this evaluation. The survey focused on consumers’ experience of our intervention and the

extent to which it affected behaviours and outcomes in line with the intervention’s

objectives.

PwC Research conducted the survey of 1,000 consumers in February 2018. Details of the

survey are summarised in Section 6 and presented in full in Annex 2.

prices over and above the general effects of inflation. We present these figures in April 2018 prices, unless stated

otherwise. By doing this, the data may appear to be different to other publications. The difference is due our real

terms adjustment.

25

‘Untreated’ is also called ‘control’. Examples of DiD approaches include: Ashenfelter & Card, 1985, Using

the Longitudinal Structure of Earnings to Estimate the Effect of Training Programs; Meyer, Viscusi & Durbin, 1990,

Workers' Compensation and Injury Duration: Evidence from a Natural Experiment; and Card, 1994, Minimum

Wages and Employment: A Case Study of the Fast-Food Industry in New Jersey and Pennsylvania.

EP 18/1: An evaluation of our guaranteed asset protection insurance intervention

17

Section summary

Our analysis shows that the various factors that might influence GAP insurance sales –

household disposable income, access to finance and new vehicle sales – have all moved

in such a way that we would expect GAP insurance demand to have increased. Access to

finance is most likely to have had the most significant impact on demand.

This section sets out the wider context to the GAP insurance market. We provide an

overview of the market’s demand drivers, describe the recent trends of these drivers,

and discuss what impact they are likely to have had on GAP insurance demand.

The main drivers of GAP insurance demand

Vehicle ownership is the main demand driver for GAP insurance. In turn, vehicle

purchases depend upon consumers’ ability to afford a vehicle, due to their disposable

income and access to finance among other things.

Household disposable income and access to finance

Figure 3.1 shows that median disposable household income increased over the period

before and after our intervention. This was a total increase of around 12% from 2013 to

2017 (£25,700 to £28,600). This might lead to a rise in demand for vehicles

26

, as

consumers have more money to afford them.

26

Assuming vehicle prices have not increased by proportionately more than incomes.

3 Results: Market context analysis

EP 18/1: An evaluation of our guaranteed asset protection insurance intervention

18

Figure 3.1: Median real household disposable income

Source: Office for National Statistics (ONS) data, FCA analysis

The new car

27

finance market has more than doubled during the past 7 years. The value

of point-of-sale new car finance increased from £7.8 billion in 2010 to £19.1 billion in

2017 (Figure 3.2). Over the same period, the number of new cars bought using point-of-

sale finance almost doubled from 517,000 to 990,000 a year. Many firms thought that

increasing access to car finance has significantly increased car sales and GAP insurance

sales in recent years.

27

Throughout the report, we focus our analysis, where possible, on vehicle sales. We do this because GAP

insurance can be purchased on a range of vehicle types, not just cars. However, finance data are only available

on car sales. We therefore analyse financing against car sales. We note that vehicle and car sales trends track

extremely closely.

0

5,000

10,000

15,000

20,000

25,000

30,000

35,000

2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017

Median real equivalised disposable income (£, 2018 prices)

EP 18/1: An evaluation of our guaranteed asset protection insurance intervention

19

Figure 3.2: New point-of-sale finance by product

Source: ONS data, Finance & Leasing Association data, FCA analysis

Note: PCP refers to personal contract purchase; HP refers to hire purchase.

Vehicle sales have increased since our intervention

Figure 3.3 shows that new vehicles sales grew, on average, by around 5% a year

between 2010 and 2016, and fell by nearly 6% between 2016 and 2017.

Figure 3.3: Yearly new vehicle sales

Source: Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA) data, FCA analysis

0

200,000

400,000

600,000

800,000

1,000,000

1,200,000

0

5,000

10,000

15,000

20,000

25,000

2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017

Number of new cars financed (yearly)

New finance value for new car sales (£m, 2018 prices)

PCP (LHS) HP (LHS) Leasing (LHS) Personal loans (LHS) New cars financed (RHS)

0

500,000

1,000,000

1,500,000

2,000,000

2,500,000

3,000,000

3,500,000

4,000,000

Jan-10 Jul-10 Jan-11 Jul-11 Jan-12 Jul-12 Jan-13 Jul-13 Jan-14 Jul-14 Jan-15 Jul-15 Jan-16 Jul-16 Jan-17 Jul-17

New vehicle sales over preceding 12 months

Period of interest

EP 18/1: An evaluation of our guaranteed asset protection insurance intervention

20

Consumers’ ability and willingness to pay for GAP insurance

Figure 3.1 and Figure 3.2, respectively, show that:

• disposable household income has increased

• consumers’ ability to buy a vehicle (and, by implication, GAP insurance at point-of-

sale) on finance has increased significantly

These factors together increase consumers’ ability to afford and need to buy GAP

insurance. Higher income may, however, reduce GAP insurance demand through an

increased ability to self-insure. That said, given the relatively small income increase, we

expect that this impact is limited. We do not expect that it is large enough to outweigh

any GAP insurance demand increases caused by consumers having more income.

Table 3.1 sets out factors affecting consumers’ willingness to pay for GAP insurance.

Table 3.1: Consumers' willingness to pay for GAP insurance

Factors affecting

consumers’

willingness to pay

Available evidence and likely impact on GAP insurance sales

through impact on consumers’ willingness to pay

The likelihood of

the vehicle being

written off or stolen

We have no evidence to suggest that this has changed in recent years.

Whether the vehicle

is new/high value

and the vehicle’s

depreciation

28

rate

New vehicles, typically, face the fastest depreciation rates. The

depreciation rate slows as the vehicle ages. So, GAP insurance is most

valuable to those buying new vehicles. Figure 3.3 shows that new vehicle

sales have increased in recent times (though it slowed in 2017).

Hence, we expect consumers’ willingness to pay for GAP insurance to

have increased overall.

The amount and

form of financing

taken

Figure 3.2 shows that:

• buying vehicles on finance has increased significantly in recent years

• the growth has been driven, almost entirely, by personal contract

purchase (PCP) agreements

29

PCPs are typically designed to minimise consumers’ vehicle loan

repayments during the term of the loan agreement. This leaves a ‘balloon

payment’ at the agreement’s end (ie a large sum of money owed on a

consumer’s finance agreement when new vehicles depreciate the fastest).

As such, we expect PCP’s high share of finance to increase consumers’

benefits from holding GAP insurance further, and, therefore, increase

their willingness to pay for it.

Consumers’

aversion to risk

30

We have no evidence to suggest that this has changed in recent years.

Source: FCA analysis

28

Depreciation captures the vehicle’s loss in value due to general ageing and ‘wear and tear’. It is the

difference between a vehicle’s value when it is bought and when it is sold.

29

PCP is a form of finance where, at the end of an agreed term, the consumer has the option to buy the

car at a predetermined value or return it.

30

This is a function of loss aversion. This is when people strongly prefer to avoid losses than receive gains

because of hard-wired emotions (fear of losses). The degree of loss aversion varies across people and situations.

It can lead to distorted attitudes to risk (eg to avoid risk from the fear of loss, consumers may pay for ‘peace of

mind’, even if the negative outcome has a very low probability).

EP 18/1: An evaluation of our guaranteed asset protection insurance intervention

21

GAP insurance demand drivers indicate that total sales would

likely have increased without our intervention

Table 3.2 summarises the changes to the market-level demand drivers (direct and

indirect) of GAP insurance.

We expect that these factors would have increased consumers’ demand for GAP

insurance without our intervention. We expect that this would have raised total GAP

insurance sales and/or prices over the evaluation period.

This informs our wider analysis of our intervention’s impact. We could, potentially,

misinterpret its true impact if we do not control for these underlying market changes (in

particular, the significant increase in consumers’ access to finance and the type of finance

that they are using). This is why we use econometric analysis to complement other

methods (as set out in Section 2).

Table 3.2: Changes to the demand drivers for GAP insurance

Demand driver

Impact on demand

Household disposable income

✓

Marginal increase

Access to finance

✓✓

Significant increase

New vehicle sales

✓

Marginal increase

Source: FCA analysis

EP 18/1: An evaluation of our guaranteed asset protection insurance intervention

22

Section summary

Add-on GAP insurance sales are 16% to 23% lower because of our intervention.

Competition between add-on and standalone GAP insurance markets, as measured by

standalone’s share of total sales, has improved, albeit only marginally.

This section summarises our analysis of how GAP insurance sales (total, add-on and

standalone) have changed after our intervention. First, we set out our pre-intervention

expectations for GAP insurance sales. Next, we present evidence on how total, add-on

and standalone GAP insurance sales trends have changed after our intervention. We

conclude with our analysis of what would have happened to add-on GAP insurance sales

had we not intervened.

We expected total GAP insurance sales to increase

Table 2.1 gives an overview of our pre-intervention expectations. Table 4.1 sets out

further details of our sales-based pre-intervention expectations.

Table 4.1: Our pre-intervention expectations for GAP insurance sales

Metric

Pre-intervention expectation

Total GAP insurance sales

Increase by between 12.5% (no add-on price change scenario) to

35% (add-on price fall scenario).

Add-on GAP insurance

sales

Fall by 32.5% (no add-on price change scenario). This is the sum

of:

• 22.5% of sales moving to the standalone GAP insurance market

• 10% of sales lost (ie consumers no longer buy GAP insurance)

Fall by 10% in the add-on price fall scenario.

Add-on GAP insurance

sales share of total GAP

insurance sales

Make up 60% (no add-on price change scenario) to 67% (add-on

price fall scenario) of the total GAP insurance market.

Standalone GAP

insurance sales share of

total GAP insurance sales

Make up 33% (add-on price fall scenario) to 40% (no add-on price

change scenario) of the total GAP insurance market.

Source: CP14/29

4 Results: Sales analysis

EP 18/1: An evaluation of our guaranteed asset protection insurance intervention

23

Total GAP insurance sales after our intervention

Figure 4.1 shows that total GAP insurance sales have been relatively constant after our

intervention.

31

Total GAP insurance sales fell from just under 1.1 million a year

32

before

our intervention to just over 1.0 million a year

33

after our intervention. This is a fall of

around 4%. Total GAP insurance sales returned to just under 1.1 million a year in the 12

months leading up to August 2017.

Figure 4.1: Monthly total GAP insurance sales

Source: FCA analysis of firms’ GAP insurance transaction data

Total GAP insurance sales as a percentage of vehicle sales

Figure 4.2 shows the monthly total GAP insurance penetration rate (ie GAP insurance

sales as a percentage of total new vehicle sales).

34

After our intervention, the GAP

insurance penetration rate (total and add-on) appears to dip noticeably in the months

when new vehicle registration plates are released (March and September). Given what

we know about vehicle sales (Figure 3.3), it looks like GAP insurance sales, in these

months, have been unable to keep up.

Table 4.2 summarises the monthly movements by taking the average across 12-month

intervals before and after our intervention.

31

GAP insurance sales display seasonal sales patterns. Sales spike in March and September in line with

new vehicle sales. This spike occurs in the months that the latest number plate variations are released.

32

Total of GAP insurance sales in the 12 months before our intervention.

33

Total of GAP insurance sales in the 12 months after our intervention.

34

The penetration rate measures the proportion of total GAP insurance sales (both for new and used vehicle

sales) relative to the number of total new vehicle registrations. Used vehicle sales data were not available for the

full period (September 2013 to August 2017). The trends in the chart were similar to those for new car sales

only, which, on average, made up 81% of all new vehicle registrations over the period.

0

20,000

40,000

60,000

80,000

100,000

120,000

140,000

160,000

180,000

Sep-13 Dec-13 Mar-14 Jun-14 Sep-14 Dec-14 Mar-15 Jun-15 Sep-15 Dec-15 Mar-16 Jun-16 Sep-16 Dec-16 Mar-17 Jun-17

Monthly total GAP insurance sales

Total GAP insurance sales

EP 18/1: An evaluation of our guaranteed asset protection insurance intervention

24

Based on Table 4.2, we see that:

• The total GAP insurance penetration rate fell after our intervention. This was due to a

small fall in total GAP insurance sales, as well as higher car sales (Figure 4.2). It has

recovered subsequently. This has happened due to a small increase in total GAP

insurance sales, as well as a slight drop in vehicle sales.

• The add-on GAP insurance penetration rate, similarly, fell after intervention. Although

it has recovered since then, it has not returned to its pre-intervention level.

The lower add-on GAP insurance penetration rate is consistent with our expectation in

Table 2.1.

Figure 4.2: Seasonally-adjusted monthly total and add-on GAP insurance sales

penetration rate

35

Source: FCA analysis of firms’ GAP insurance transaction data and DVLA vehicle registration data

Table 4.2: Average GAP insurance penetration rates

GAP

insurance

market

12 months before

intervention

(September 2014 –

August 2015)

12 months after

intervention

(September 2015 –

August 2016)

12 months to August

2017

(September 2016 –

August 2017)

Total

38%

35%

37%

Add-on

36%

32%

34%

Source: FCA analysis of firms’ GAP insurance transaction data and DVLA vehicle registration data

35

We adjust the monthly data to remove sales’ seasonality (eg the sales spikes in March and September).

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

Sep-13 Dec-13 Mar-14 Jun-14 Sep-14 Dec-14 Mar-15 Jun-15 Sep-15 Dec-15 Mar-16 Jun-16 Sep-16 Dec-16 Mar-17 Jun-17

GAP insurance penetration rate (deseasonalised)

Total GAP insurance penetration rate for new vehicles Add-on GAP insurance penetration rate for new vehicles

EP 18/1: An evaluation of our guaranteed asset protection insurance intervention

25

Standalone GAP insurance sales after our intervention

Although total GAP insurance sales have been constant, the trends in add-on and

standalone GAP insurance sales have differed after our intervention.

Figure 4.3 shows monthly add-on and standalone GAP insurance sales figures. Table 4.3

presents the annual data before and after our intervention.

Table 4.3 highlights that post-intervention add-on GAP insurance sales are similar to

those pre-intervention. Add-on GAP insurance sales fell, initially, by around 6%. They

have recovered to be 2% lower than before our intervention. Our analysis and

discussions with firms suggest that this is not due to our intervention causing firms not to

offer add-on GAP insurance. Figure 4.3 shows that add-on GAP insurance sales display

the same monthly fluctuations across the pre- and post-intervention periods, with spikes

in March and September.

Standalone GAP insurance sales have increased significantly after our intervention,

starting from a relatively low base. Hence, the percentage changes in Table 4.3 are

relatively large. Figure 4.3 shows that standalone GAP insurance sales have developed a

seasonal sales pattern similar to add-on GAP insurance sales after our intervention.

There was no clear seasonality for standalone GAP insurance sales before our

intervention.

Figure 4.3: Monthly standalone and add-on GAP insurance sales

Source: FCA analysis of GAP insurance transaction data provided by firms

0

2,000

4,000

6,000

8,000

10,000

12,000

14,000

0

20,000

40,000

60,000

80,000

100,000

120,000

140,000

160,000

Sep-13 Mar-14 Sep-14 Mar-15 Sep-15 Mar-16 Sep-16 Mar-17

Monthly standalone GAP insurance sales

Monthly add

-on GAP insurance sales

Add-on GAP insurance sales (LHS) Standalone GAP insurance sales (RHS)

EP 18/1: An evaluation of our guaranteed asset protection insurance intervention

26

Table 4.3: GAP insurance sales volumes

GAP

insurance

market

12 months before

intervention

(September 2014 –

August 2015)

12 months after

intervention

(September 2015 –

August 2016)

12 months to August

2017

(September 2016 –

August 2017)

Add-on

1,012,000

946,000

(-6%)

996,000

(-2%)

Standalone

61,000

85,000

(39%)

96,000

(57%)

Source: FCA analysis of GAP insurance transaction data provided by firms

Note: Figures rounded to the nearest thousand; percentage changes are relative to the pre-

intervention sales figures.

Figure 4.4 shows the split of half-yearly total GAP insurance sales between add-on and

standalone sellers. It shows that standalone’s share of total sales has increased from

around 6% in the 2 years before our intervention to around 9% in the 2 years after.

Higher standalone GAP insurance sales (absolute and as a percentage of total GAP

insurance sales) explain the difference in total and add-on GAP insurance penetration

rates in Figure 4.2.

Figure 4.4: Half-yearly shares of standalone and add-on GAP insurance sales as

a proportion of total GAP insurance sales

Source: FCA analysis of GAP insurance transaction data provided by firms

95%

94%

94%

94%

92%

91%

91%

91%

5%

6%

6%

6%

8%

9%

9%

9%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

H1 2013/14 H2 2013/14 H1 2014/15 H2 2014/15 H1 2015/16 H2 2015/16 H1 2016/17 H2 2016/17

Market share of total GAP insurance sales

Add-on GAP insurance sales Standalone GAP insurance sales

EP 18/1: An evaluation of our guaranteed asset protection insurance intervention

27

Our intervention’s impact on add-on sales

We use econometric analysis to estimate our intervention’s causal

impact

Econometric analysis isolates our intervention’s impact from other factors

36

that may

have also influenced add-on GAP insurance sales. Full details of our analysis are available

in the Technical Annex. Our analysis shows that sales of add-on GAP insurance and CWP

followed similar trends before our intervention. We use this to assume that add-on GAP

insurance sales would have followed a similar trend to CWP sales had we not intervened.

The intervention’s impact is the difference between our estimate of what would have

happened had we not intervened and what actually happened.

Add-on GAP insurance sales are 16% to 23% lower than they would

have been without our intervention

Table 4.4 summarises the results of our econometric analysis. We estimate that add-on

GAP insurance sales are between 16% and 23% lower due to our intervention.

37

Our pre-

intervention expectation was that, all other things being equal, add-on GAP insurance

sales would fall by between 10% and 32.5%.

Table 4.4: Our intervention’s estimated impact on add-on GAP insurance sales

38

Estimate

Estimated impact on add-on

GAP insurance sales

Pre-intervention estimated

impact on add-on GAP

insurance sales

Lower bound estimate

-16%

-10% to -32.5%

Central estimate

-19%

Upper bound estimate

-23%

Source: FCA analysis of transaction data provided by firms; CP14/29

The results also indicate that, all else being equal, the add-on share of total GAP

insurance sales would have been higher had we not intervened. We are unable to

estimate by how much because some of these add-on GAP insurance sales could have

been:

• substituted to the standalone GAP insurance market

• lost altogether (ie consumers choose not to buy GAP insurance)

We do not know the precise split between these two groups.

Consumer switching to the standalone market

Table 4.3 suggests that the substitution effect from add-on to standalone GAP insurance

sales has been small.

36

These factors may be observable (eg changes in car sales) or unobservable (eg consumer risk

preferences or dealers’ commercial incentives).

37

The econometric analysis estimates a statistically significant point estimate of a 19% reduction in add-

on GAP insurance sales relative to the comparator product CWP. The range quoted is the 95% confidence interval

around this point estimate.

38

See Technical Annex for details of how we test our econometric analysis. Overall, these checks indicate

that the size and direction of our intervention’s estimated impact are stable and statistically robust.

EP 18/1: An evaluation of our guaranteed asset protection insurance intervention

28

Even if all the increase in standalone GAP insurance sales is due to substitution alone,

this would account for only 8% to 13% of the estimated fall in add-on GAP insurance

sales. This is much lower than the fall in add-on GAP insurance sales that we estimated

would move to the standalone market as part of our pre-intervention CBA (ie 70%, which

is 22.5% divided by 32.5% in Table 4.1).

Our range of 8% to 13% is likely to be the upper threshold. This is because some

standalone GAP insurance sales may have been to consumers new to the market (ie

consumers that did not move over from the add-on GAP insurance market).

Add-on GAP insurance sales that did not happen due to our intervention

The results indicate that our intervention had a notable effect on add-on GAP insurance

sales. This appears to be due to consumers not buying GAP insurance at all, rather than,

as we had expected, buying standalone GAP insurance instead. Figure 4.2 shows that the

GAP insurance sales penetration rate dipped in the months where vehicle sales are

normally highest. This also suggests that our intervention may have reduced GAP

insurance sales that might otherwise have happened.

The analysis does not capture which of the intervention’s policy measures had the

greater relative impact (see Section 6).

We estimate that add-on GAP insurance sales are 16% to 23% lower due to our

intervention. This causal impact is likely to have affected the following consumer groups:

1. Consumers for whom buying GAP insurance is an unsuitable product choice: our

intervention has caused these people not to buy add-on GAP insurance

2. Consumers for whom buying add-on GAP insurance is an unsuitable purchase, but

buying standalone GAP insurance is a more appropriate choice: our intervention, it

appears, caused only a relatively small number of these people to buy standalone

GAP insurance

3. Consumers for whom buying add-on GAP insurance is an appropriate product

purchase: we felt, before intervening, that there were very few of these people in the

market. But, our intervention may have caused this group of people not to buy

something that they valued correctly. Although it might appear that add-on GAP

insurance is never a suitable purchase (eg because it can be bought elsewhere for a

much cheaper price), it might be appropriate for consumers who value:

– convenience

– not searching for a standalone policy

– the peace of mind in knowing that they are covered

– being able to buy GAP insurance in person (rather than on the phone or online)

The largest positive impact of our intervention happens if the causal impact is

predominantly among the first consumer group. In contrast, the most negative impact of

our intervention occurs if the causal impact is among the third consumer group. We do

not know precisely how our estimated causal impact is distributed across the 3 consumer

groups.

However, our market study’s findings, and our basis for intervening in the first place,

lead us to think that our impact has been, predominantly, among the first 2 consumer

groups. Before intervening, we thought that many consumers who bought this product

EP 18/1: An evaluation of our guaranteed asset protection insurance intervention

29

did not need it. For example, we found that 59% of people who bought add-on GAP

insurance had not considered buying it before the day of purchase. That is not to say that

all these consumers did not value the product and/or truly needed it. But we believed

that many were buying a product that they did not need.

As a result, we consider that our causal impact on sales is, overall, a positive outcome of

our intervention.

Summary of GAP insurance sales analysis

We summarise the findings of our GAP insurance sales analysis in Table 4.5.

Table 4.5: Summary results from our analysis of GAP insurance sales

Outcome

Pre-intervention

expectation

Observed outcome

after our

intervention

Estimated causal

impact of our

intervention

Percentage change to total

GAP insurance sales

+12.5% to +35%

-4%

N/A

Percentage change to add-

on GAP insurance sales

-10% to -32.5%

-2% to -6%

-16% to -23%

Add-on GAP insurance sales

as a share of all GAP

insurance sales

60% to 67%

92%

(94% before

intervention)

N/A

Standalone GAP insurance

sales as a share of all GAP

insurance sales

33% to 40%

8%

(6% before

intervention)

N/A

Source: FCA

EP 18/1: An evaluation of our guaranteed asset protection insurance intervention

30

Section summary

Average add-on GAP insurance prices have continued to increase after our intervention,

although they would have been even higher without it.

Average standalone GAP insurance prices fell by 5% after our intervention.

The price difference between average add-on and standalone GAP insurance prices,

therefore, has increased after our intervention.

This section summarises our analysis of how GAP insurance prices

39

(total, add-on and

standalone) have changed after our intervention. First, we do so by setting out details of

our pre-intervention expectations for GAP insurance prices. Next, we present evidence on

how total, add-on and standalone GAP insurance price trends have changed after our

intervention. We conclude with our analysis of what would have happened to add-on GAP

insurance prices had we not intervened.

Before intervening, we expected lower average GAP insurance

prices if add-on prices fell

Table 2.1 gives an overview of our pre-intervention expectations. Table 5.1 shows sets

out details of our pre-intervention expectations for GAP insurance prices.

Table 5.1: Our pre-intervention expectations for average GAP insurance prices

Metric

Pre-intervention expectation

Average add-on GAP insurance prices

Scenario 1: No price change

Scenario 2: Price falls by 17%

Average standalone GAP insurance prices

No price change

Source: FCA CP14/29

Average overall GAP insurance retail prices show little change

after our intervention

Based on the analysis in Section 3 and the rationale set out at the beginning of

Section 4, we expect GAP insurance prices to be higher after our intervention. The

increase in disposable income and access to finance suggest that, all else being equal,

consumers would be willing to pay more for GAP insurance. We expect that this would

lead to higher average GAP insurance prices.

39

We focus on the final price charged to the consumer (including tax), which we call the ‘retail price’.

5 Results: Price analysis

EP 18/1: An evaluation of our guaranteed asset protection insurance intervention

31

Figure 5.1 shows that the average GAP insurance price has increased by a small amount,

in real terms, after our intervention. The average price remained almost unchanged

between the 12 months before and after our intervention. It decreased from £363 to

£362 in real terms.

40

The average price then increased to £367 for the 12 months ending

August 2017 (also in real terms).

To understand why this might have happened, the rest of this section considers what has

happened to average prices in the add-on and standalone markets, and other factors that

might influence GAP insurance prices.

Figure 5.1: Monthly market average GAP insurance retail price

Source: FCA analysis of GAP insurance transaction data provided by firms

Add-on and standalone prices show diverging trends

Section 3 suggests that there has been a large impact on add-on, rather than

standalone, GAP insurance prices. This is because consumers are buying more vehicles

on finance, thereby reducing consumers’ financial constraints at the point of buying the

vehicle. This, in turn, might have increased consumers’ ability to pay for add-on GAP

insurance. As such, we also look at average price changes between the different markets

(ie add-on and standalone).

Figure 5.2 shows the monthly average add-on and standalone GAP insurance price. Table

5.2 summarises the monthly movements by taking the average across 12-month

intervals before and after our intervention.

40

All 12-month prices are weighted averages. We calculate this as the average price for each month

multiplied by the number of policies sold in that month, which is then divided by the total number of policies sold

in the 12-month period.

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

350

400

450

500

Sep-13 Dec-13 Mar-14 Jun-14 Sep-14 Dec-14 Mar-15 Jun-15 Sep-15 Dec-15 Mar-16 Jun-16 Sep-16 Dec-16 Mar-17 Jun-17

Market average GAP insurance retail price (£, 2018 prices)

EP 18/1: An evaluation of our guaranteed asset protection insurance intervention

32

The data highlight that average add-on and standalone GAP insurance prices diverged

after our intervention. This has happened to such an extent that the average add-on GAP

insurance price is, now, almost two and a half times the average standalone GAP

insurance price. The average standalone GAP insurance price fell despite Insurance

Premium Tax (IPT) rates increasing for standalone sellers over the period.

41

These average price changes are contrary to our pre-intervention expectations (Table 2.1

and Table 5.1). We consider why this has happened in the rest of this section.

Figure 5.2: Monthly average GAP insurance retail price by market segment

Source: FCA analysis of GAP insurance transaction data provided by firms

41

Standalone GAP insurance sellers face the standard rate of IPT. This increased from 6% to 9.5% on

1 November 2015, then to 10% on 1 October 2016, and, finally, to 12% on 1 June 2017. Add-on GAP insurance

sellers also face the lower rate of IPT when the GAP insurance product is directly and solely related to a finance

contract. For other types of GAP insurance, add-on sellers face the higher rate of IPT, which has been 20% since

4 January 2011. IPT is expressed as an additional percentage to the retail selling price (excluding tax). See

HMRC’s guidance.

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

350

400

450

Sep-13 Dec-13 Mar-14 Jun-14 Sep-14 Dec-14 Mar-15 Jun-15 Sep-15 Dec-15 Mar-16 Jun-16 Sep-16 Dec-16 Mar-17 Jun-17

GAP insurance average retail price (£, 2018 prices)

Add-on average retail price Standalone average retail price

EP 18/1: An evaluation of our guaranteed asset protection insurance intervention

33

Table 5.2: Average GAP insurance price (segment and price difference), 2018

prices

42

Metric

12 months before

intervention

(September 2014 –

August 2015)

12 months after

intervention

(September 2015 –

August 2016,

% change to pre-

intervention figure)

12 months to August

2017

(September 2016 –

August 2017,

% change to pre-

intervention figure)

Add-on

£375

£379

(+1%)

£387

(+3%)

Standalone

£186

£176

(-5%)

£162

(-13%)

Add-on and

standalone price

difference

£189

£202

(+7%)

£225

(+19%)

Source: FCA analysis of GAP insurance transaction data provided by firms

Changes to policy coverage

One possible reason behind the different add-on and standalone GAP insurance average

price trends could be changes in the policy coverage offered, and sold, by firms.

We see changes in policy coverage in our data that could explain part of what we see.

Table 5.3 presents changes in average policy coverage in the 12 months before and after

our intervention.

43

However, these changes do not appear large enough to explain the

full extent of the price changes in Figure 5.2.

Table 5.3: Changes in average policy coverage by market segment (12 months

before and after our intervention)

Coverage factor

Change

44

for add-on GAP

insurance

Change for standalone GAP

insurance

Policy duration

+0.3 months

-0.7 months

Value of car insured

(real terms)

+1.9%

+5.8%

Proportion of policies

covering financed cars

-1.6 percentage points

-8.3 percentage points

Source: FCA analysis of GAP insurance transaction data provided by firms

We do not find that other costs are contributing to the divergence in add-on and

standalone GAP insurance prices after our intervention:

• It does not appear that add-on GAP insurance prices are higher because of ongoing

compliance costs (Section 7)

42

Figures are rounded to the nearest currency unit. Any differences are due to calculations that are not

based on the rounded figures presented here. Percentage changes in brackets are rounded and relative to the

figures before intervention.

43

See Technical Annex for charts illustrating the change in these factors over time.

44

Change is calculated as the difference between the averages of the relevant factors over the 12 months

following our intervention and the 12 months prior to our intervention.

EP 18/1: An evaluation of our guaranteed asset protection insurance intervention

34

• Our intervention may have, indirectly, lowered the average cost of selling standalone

GAP insurance. For example, fixed costs (such as IT and customer support) are now

spread across a larger number of policies, given higher standalone GAP insurance

sales, after our intervention. However, this effect is likely to have been small.

Changes in underlying risk

GAP insurance is a risk-based product. This means that the riskiness of those being

insured influences part of the cost of providing GAP insurance. A possible explanation of

post-intervention add-on and standalone prices could be changes to the riskiness of the

people buying these GAP insurance products.

For example, we might expect that consumers who no longer buy add-on GAP insurance

(Section 4) may have a lower need for GAP insurance. This might be because, for

example, they are less risky than other consumers. As such, the remaining add-on GAP

insurance buyers would be riskier on average. This could lead insurers to raise prices to

cover the increased perceived risk among the remaining add-on GAP insurance buyers.

This is consistent with what we see in firms’ data. Add-on GAP insurance underwriter

prices

45

increased by 12% in the 12 months after our intervention, when compared to the

12 months beforehand. Underwriter prices for standalone GAP insurance fell by 9% over

the same period.

We expect that some of this is a result of policy coverage changes (Table 5.3). However,

even when we control for policy coverage changes, we still see a small increase (1.4%)

in add-on GAP insurance prices and a small decrease (0.4%) in standalone GAP

insurance prices. Our analysis of consumers’ probability to claim (see Section 7) also

confirms this higher riskiness among remaining add-on GAP insurance buyers.

How add-on GAP insurance prices are split

Another factor that may affect the average GAP insurance retail price is the margin that

the seller charges above their costs. This is a function of the value taken by the various

parts of the distribution chain, and the underlying cost of insuring the expected risk.

Figure 5.3 shows the different elements that form the average add-on GAP insurance

retail price.

45

We use underwriter prices as a proxy for the risk-based cost of providing the insurance. From discussions

with firms, we understand that the GAP insurance underwriting market is relatively competitive.

EP 18/1: An evaluation of our guaranteed asset protection insurance intervention

35

Figure 5.3: Proportion of the average add-on GAP insurance retail price received

by each part of the distribution chain

Source: FCA analysis of GAP insurance transaction data provided by firms

Note: Due to our data collection, the quarters are: Q1 – September-November; Q2 – December-

February; Q3 – March-May; and Q4 – June-August.

Figure 5.3 shows that add-on GAP insurance sellers keep a similar proportion of the final

retail price before (58% in the 12 months before our intervention) and after our

intervention (56% in the 12 months after our intervention).

This suggests that add-on GAP insurance sellers still hold a strong position in the

distribution chain and can pass on supplier costs to consumers whilst maintaining their

margin.

Our intervention’s impact on add-on prices

We take the same econometric approach as in Section 4 to estimate our intervention’s

impact on add-on GAP insurance prices.

46

We compare price trends of add-on GAP

insurance and CWP for which the price trends are broadly common before the

intervention.

47

The intervention’s average price impact is the difference between our estimate of what

would have happened had we not intervened and what actually happened.

Table 5.4 summarises the results of our econometric analysis. We estimate that average

add-on GAP insurance prices are between 2% and 3% lower than they would have been

46

See Technical Annex for supporting further details, assumptions, and evidence, including a chart on pre-

intervention price trends for add-on GAP insurance and CWP.

47

Section 4 set out why our estimates might over- or underestimate the true impact of our intervention.

The same logic applies to our price analysis.

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

Q1,

2013/14

Q2,

2013/14

Q3,

2013/14

Q4,

2013/14

Q1,

2014/15

Q2,

2014/15

Q3,

2014/15

Q4,

2014/15

Q1,

2015/16

Q2,

2015/16

Q3,

2015/16

Q4,

2015/16

Q1,

2016/17

Q2,

2016/17

Q3,

2016/17

Q4

2016/17

Average proportion of retail price received from add

-on GAP insura ce sales

Tax Underwriter Intermediary Retailer

EP 18/1: An evaluation of our guaranteed asset protection insurance intervention

36

had we not intervened.

48