Jürgen Georg Backhaus

Editor

Handbook of the History

of Economic Thought

Insights on the Founders

of Modern Economics

Editor

Prof. Dr. Jürgen Georg Backhaus

University of Erfurt

Krupp Chair in Public Finance and Fiscal Sociology

Nordhäuser Str. 63

99089 Erfurt Thüringen

Germany

ISBN 978-1-4419-8335-0 e-ISBN 978-1-4419-8336-7

DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-8336-7

Springer New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London

Library of Congress Control Number: 2011934677

© Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2012

All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written

permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York,

NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in

connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software,

or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden.

The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they

are not identifi ed as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are

subject to proprietary rights.

Printed on acid-free paper

Springer is part of Springer Science+Business Media (www.springer.com)

Preface

Avant Propos

A further reason for studying the history of economic thought was provided by

Pareto in the lead article of the “Giornale di Economisti” of 1918 (Volume 28; pages

1–18) under the title “Experimental Economics”.

1

In as much as economic theories

also have an extrinsic value, that is, they lead people to act as informed by the

theory, such as in economic policy or public fi nance, the theory becomes a subject

for economic investigation itself. The distinction between the intrinsic aspect and

the extrinsic aspect of a theory is crucial for this argument. The intrinsic aspect of a

theory refers to its logical consistence and, as such, has no further repercussions. As

far as the intrinsic aspects are concerned, theoretical knowledge is actually cumula-

tive. On the other hand, the extrinsic aspect of an economic theory will become a

“derivation” (in Pareto’s terminology) in that it serves as the rationalization of

human activity. In Pareto’s sociology, human action is determined by residues,

innate traits that determine human behaviour, and derivations. Derivations are more

or less logical theories or world views that guide people’s behaviour. To the extent

that economic theory can also guide human behaviour, economic theory becomes a

social fact or construct that is itself subject to economic analysis. As we experiment

with different economic theories to guide economic policy in general and fi scal

policy in particular, the history of economic thought can actually be practised as

experimental economics in documenting the impact different economic theories

have on economic behaviour. Of course, this experimental kind of history of

economic thought becomes the more relevant the more similar the situations are in

which different economic theories are applied.

1

The following account is based on Michael McLure, The Paretian School and Italian Fiscal

Sociology. London, Palgrave 2007.

Contents

1 Introduction ............................................................................................ 1

Jürgen G. Backhaus

2 The Tradition of Economic Thought in the Mediterranean

World from the Ancient Classical Times Through the Hellenistic

Times Until the Byzantine Times and Arab-Islamic World ................ 7

Christos P. Baloglou

3 Mercantilism ........................................................................................... 93

Helge Peukert

4 The Cameralists: Fertile Sources for a New Science

of Public Finance .................................................................................... 123

Richard E. Wagner

5 The Physiocrats ...................................................................................... 137

Lluis Argemí d’Abadal

6 Adam Smith: Theory and Policy .......................................................... 161

Andrew S. Skinner

7 Life and Work of David Ricardo (1772–1823) ..................................... 173

Arnold Heertje

8 John Stuart Mill’s Road to Leviathan:

Early Life and Infl uences ...................................................................... 179

Michael R. Montgomery

9 John Stuart Mill’s Road to Leviathan II:

The Principles of Political Economy..................................................... 205

Michael R. Montgomery

10 Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832) ............................................................... 279

Christos P. Baloglou

viii Contents

11 Johann Heinrich von Thünen: A Founder

of Modern Economics ............................................................................ 299

Hans Frambach

12 The Legacy of Karl Marx ...................................................................... 323

Helge Peukert

13 Friedrich List’s Striving for Economic Integration

and Development .................................................................................... 351

Karl-Heinz Schmidt

14 The Entwickelung According to Gossen .............................................. 369

Jan van Daal

15 Gustav Schmoller as a Scientist of Political Economy ........................ 389

Reginald Hansen

16 The Empirical and Inductivist Economics

of Professor Menger ............................................................................... 415

Karl Milford

17 Antoine Augustin Cournot .................................................................... 437

Christos P. Baloglou

18 Léon Walras: What Cutes Know and What They

Should Know .......................................................................................... 465

J.A. Hans Maks and Jan van Daal

19 Alfred Marshall ...................................................................................... 495

Earl Beach

20 Knut Wicksell and Contemporary Political Economy ....................... 513

Richard E. Wagner

21 Werner Sombart ..................................................................................... 527

Helge Peukert

22 The Scientifi c Contributions of Heinrich von Stackelberg ................. 565

Peter R. Senn

23 Joseph Alois Schumpeter: The Economist of Rhetoric ...................... 581

Yuichi Shionoya

24 Against Rigid Rules – Keynes’s View on Monetary Policy

and Economic Theory ............................................................................ 605

Elke Muchlinski

25 Keynes’s “Long Struggle of Escape” .................................................... 625

Royall Brandis

ix

Contents

26 John Maynard Keynes and the Theory

of the Monetary Economy ..................................................................... 641

Hans-Joachim Stadermann and Otto Steiger

27 James Steuart and the Theory of the Monetary Economy ................ 667

Hans-Joachim Stadermann and Otto Steiger

28 Friedrich August Hayek (1899–1992) ................................................... 689

Gerrit Meijer

Index ................................................................................................................ 713

Contributors

Jürgen G. Backhaus University of Erfurt, Nordhäuser Street 63 99089,

Erfurt, Germany

Christos P. Baloglou Hellenic Telecommunications Organization, S.A.

Messenias 14 & Gr. Lamprakis, 143 42 Nea Philadelphia, S.A. Athens, Greece

Earl Beach Charles Beach, Department of Economics , John Deutsch Institute ,

Kingston , ON, Canada

Royall Brandis University of Illinois at Urbana, Champaign , IL , USA

Lluis Argemí d’Abadal University of Barcelona , Diagonal, 690 ,

08034, Barcelona , Spain

Jan van Daal Triangle, University of Lyon-2 ,

Lyon , France

Hans Frambach Department of Economics , Schumpeter School of Business &

Economics, University of Wuppertal , Gaußstraße 20, 42097 Wuppertal , Germany

Reginald Hansen Luxemburger Stra b e 426, 50937 Cologne , Germany

Arnold Heertje Laegieskampweg 17, 1412 ER , Naarden , The Netherlands

J.A. Hans Maks Euroregional Centre of Economics (Eurocom) ,

Maastricht University , Maastricht , The Netherlands

xii Contributors

Gerrit Meijer Department of Economics, Maastricht University , Larixlaan 3,

1231 BL Loosdrecht , The Netherlands

Karl Milford Department of Economics , University of Vienna,

Vienna , Austria

Michael R. Montgomery , PhD School of Economics, University of Maine ,

5774 Stevens Hall, Orono , ME 04469, USA

Elke Muchlinski Institute of Economic Policy and Economic History ,

Freie Universität Berlin , Boltzmannstraße 20, 14195 Berlin , Germany

Helge Peukert Faculty of the Sciences of the State/Economics,

Law and Social Science, Nordhäuser Str. 63, 99089 Erfurt, Germany

Karl-Heinz Schmidt Department of Economics , University Paderborn ,

Warburger Street. 100, 33098 Paderborn , Germany

Peter R. Senn 1121 Hinman Avenue, Evanston , IL 60202, USA

Yuichi Shionoya Hitotsubashi University, Kunitachi,

Tokyo 186-8601, Japan ,

Andrew S. Skinner Adam Smith Professor Emeritus in the University

of Glasgow’s Department of Political Economy, Glen House, Cardross ,

Dunbartonshire G82 5ES , UK

Hans-Joachim Stadermann Berlin School of Economics and Law ,

Hochschule für Wirtschaft und Recht Berlin, Badensche Straße 50–51,

10825 Berlin , Germany

Otto Steiger Institut für Konjunktur- und Strukturforschung (IKSF) ,

FB 7 – Wirtschaftswissenschaften, Universität Bremen, Postfach 33 04 40,

28334 Bremen , Germany

Richard E. Wagner Department of Economics , George Mason University ,

Fairfax , VA 22030, USA

1

JG B kh ( d) HdbkfhHi fE iTh h

History of Economic Thought, what for? Joseph Schumpeter has noted: “Older

authors and older views acquire … an importance … [when] the methods of the

economic research worker are undergoing a revolutionary change.”

1

In a time of

economic crisis, a refl ection of the roots of economic theory and methods prevents

us from following the wrong path. Leland Yeager has outlined the responsibility of

the historian of economic thought as follows:

“It is probably more true of economics than of the natural sciences that earlier

discoveries are in danger of being forgotten; maintaining a cumulative growth of

knowledge is more diffi cult. In the natural sciences, discoveries get embodied not

only into further advances in pure knowledge but also into technology, many of whose

users have a profi t and loss incentive to get things straight. The practitioners of eco-

nomic technology are largely politicians and political appointees with rather different

incentives. In economics, consequently, we need scholars who specialize in keeping

us aware and able to recognize earlier contributions – and earlier fallacies – when

they surface as supposedly new ideas. By exerting a needed discipline, specialists in

the history of thought can contribute to the cumulative character of economics.”

2

The Austrian process of time-consuming roundabout production, where the

results get better over time, is hopefully true with respect to this book. The book

grew out of lectures started on behalf of the graduate students at Maastricht

University,

3

where I taught until the fall of the year 2000. The work has an encyclopedic

J. G. Backhaus (*)

University of Erfurt , Faculty of the Sciences of State , Nordhäuser Street 63 99089 ,

Erfurt , Germany

e-mail: [email protected]

Chapter 1

Introduction

Jürgen G. Backhaus

1

Joseph A. Schumpeter, “Some Questions of Principle,” unpublished introduction to his History of

Economic Analysis , 1948/1949, p. 4 (I owe this reference to Professor Loring Allen, who found

this manuscript in Schumpeter’s estate at Harvard University.).

2

Leland Yeager ( 1981 ) , “Clark Warburton 1896–1979.” History of Political Economy 13 (2),

pp. 279–284, p. 283.

3

dr. Peter Berends, still of Maastricht University, was my trusted partner in this.

2 J.G. Backhaus

character which is why we completed the lectures at Erfurt University, where I have

been since then.

In principle, there are at least four ways to answer the question “History of

Economic Thought – what for?” One may fi rst speculate about possible uses and

purposes of the history of economic thought as revealed in the practice of teaching

the subject matter; employ methods of literary interpretation in surveying earlier

attempts along similar lines in order to amicably urge others to follow the guidelines

of a program thus derived. This is the approach characteristic of the largest part of

the substantial body of literature discussing the purposes of doctrinal history.

Second, we can consult the published record and determine what difference the

use of historical analysis makes in published research. This will yield but a distorted

picture. In many European universities, the emphasis on publishing research is

much slighter than in their North American counterparts. Scholars like the late Piero

Sraffa often command respect primarily for their contributions to the oral tradition.

While the oral tradition has always remained important,

4

publishing research has

become more important in European academe over the last few years, but was

almost accidental before.

5

Third, one could analyze survey data. While the problems associated with this

method are generally recognized, this often proves to be the only feasible method.

Fourth, an analysis of the course titles of the history of economic thought classes

taught will reveal a great deal about their contents. While in America, course titles

tend to be standardized and are unlikely to vary with the instructor who happens to

teach the course, this is most likely not so in the German, Austrian, and Swiss uni-

versity. The curriculum guidelines tend to be more general, and each chair is gener-

ally responsible for the development of an area of research and instruction in a

particular subdiscipline of economics. Hence, the course titles (and contents) are the

work of the professor who offers the course and who tries to announce precisely

what the course is going to be about.

The literature analysis revealed the following purposes commonly claimed for

the history of economic thought instruction.

6

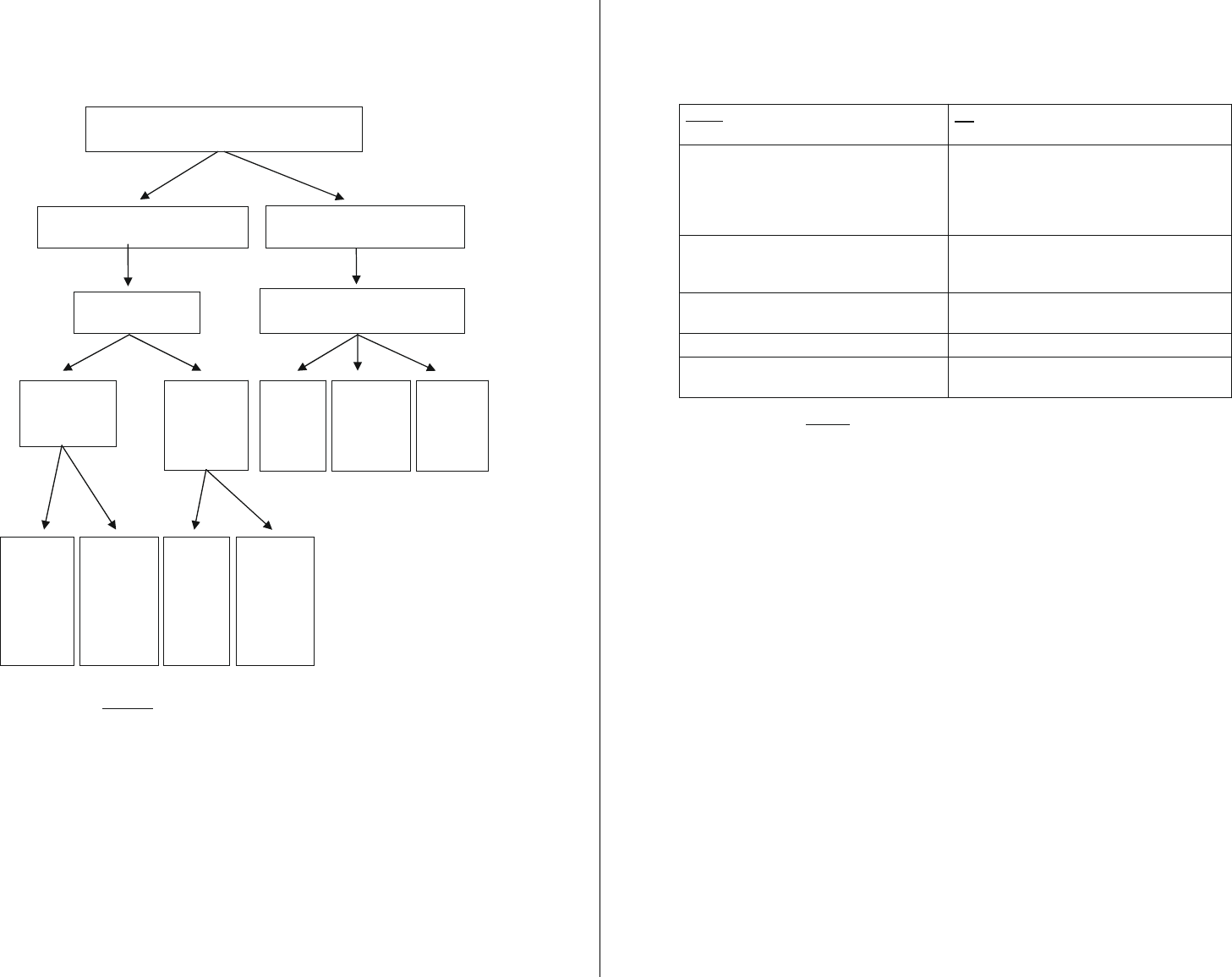

Table 1.1 lists purposes, an exemplary

bibliographical source, and a category to which the purpose has been assigned in

order to make the empirical task more manageable.

It should be obvious that this list of purposes, as long as it is, cannot possibly be

said to be fully complete. There may be as many different purposes as there are

4

Compare, e.g., Wilhelm Röpke’s discussion in: “Trends in German Business Cycle Policy,”

Economic Journal , vol. XLIII, no. 171, (

1933 ) , pp. 427–441.

5

The notion of “publish or perish” is still not descriptive of life in most European universities.

Publication may often be prompted by a particular festive occasion, as when a colleague is to be

honored with a Festschrift .

6

These results (slightly updated) are based on and excerpted from Jürgen Backhaus,

“Theoriegeschichte – wozu?: Eine theoretische und empirische Untersuchung.” Studien zur

Entwicklung der ökonomischen Theorie III, H. Scherf, ed. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot 1983

(Schriften des Vereins für Socialpolitik, N.V. 115 III). Compare also Jürgen Backhaus (

1986 ) :

“History of Economic Thought – What For? Empirical Observations from German Universities,”

The History of Economics Society Bulletin , VII/2, pp. 60–66.

3

1 Introduction

historians of economic thought, and likely even more, since some resourceful writers

such as Schumpeter (

1954 ) managed to give several good reasons, without adhering

to any one of them, while pursuing still different purposes. In order to reduce this

complexity, in our empirical study

7

groups or categories of purposes have been

formed, which in turn we tried to identify by appropriately grouping the course

titles. The result of this effort is shown in the following table. It shows how many

courses could be attributed to each category of purpose. In interpreting this result,

one should note that in general only advanced students will be enrolled in courses

studying special problems or subdisciplines of economics (Table

1.2 ).

It is probably not an overstatement to say that historians of economic thought

have many different purposes in mind when they teach the subject.

It came as a great surprise when we learned that the extent of instruction in

the history of economic thought of post WWII German universities is impressive

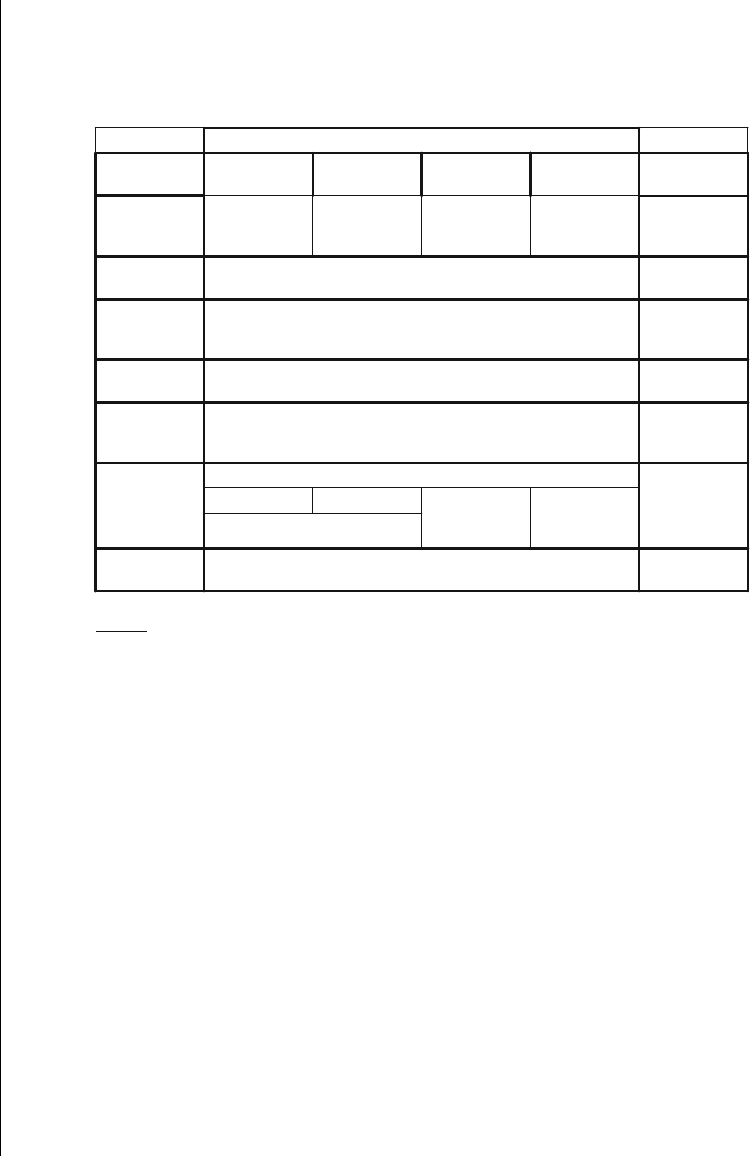

Table 1.1 Purposes

To learn

The intellectual heritage and a critical posture in

dealing with texts

Samuels ( 1974 ) Introductory course

Principles of economics Breit and Ransom

(

1982 )

Principles

From the classical works that have withstood the

test of time

Stigler (

1969 ) Advanced

undergraduate

From the masters Walker (

1983 ) Advanced

Economics as a history of economists Recktenwald (

1965 ) Introduction

To receive new insights for current research Schumpeter (

1954 ) Graduate research

To understand the “fi liation of ideas,” what succeeds,

and how, and why

Schumpeter (

1954 ) Graduate research

Guidance when the science undergoes revolutionary

change

Schumpeter (

1948 /

1949)

Graduate research

Epistemological argument Schumpeter (

1954 ) Research

Study of the competition of ideas Stigler and Friedland

(

1979 )

Research

Over time

Across cultures

Between schools

Concerning cyclical developments Neumark (

1975 ) Research

With respect to different factor markets Perlman and

McCann (

2000 )

Research

Preserving the stock of economic knowledge Yeager (

1981 ) Research

7

Compare Backhaus, op. cit. , ( 1983 ) . The purposes for offering courses in the history of economic

thought at German, several Swiss and Austrian Universities have empirically been identifi ed for

the post WWII period until March 1980. Such a long time span was possible by making our survey

comparable to an earlier study undertaken before the university reforms in 1960. Compare Bruno

Schultz (

1960 ) , “Die Geschichte der Volkswirtschaftslehre im Lehrbetrieb deutscher Universitäten

und einiges zur Problematik.” In: Otto Stammer, Karl C. Thalheim (eds.), Festgabe für Friedrich

Bülow zum 70. Geburtstag . Duncker & Humblot, pp. 343–362.

4 J.G. Backhaus

and largely underestimated. Of the 54 universities surveyed, 27 offer instruction

in the history of economics, while 13 do not. It is likely that of the remaining

quarter, or 14 universities, more are involved in instruction in the subject than

that are not.

These data even correct the earlier study by Schultz (

1960 ) . The reason for the

differences is straightforward. Schulz had only consulted the university bulletins,

while we had co-operated with each university on a case-by-case basis and therefore

had received information not contained in the bulletins. This method yielded a sub-

stantial correspondence which proved helpful in assigning the courses to categories.

The correspondence revealed more information about the purposes of the lectures

than can be mentioned in this introduction.

It is interesting to note some cultural differences

8

between our survey results and

Anglo-American fi ndings. Apart from the obvious differences in the organization of

courses, which turn on the chair system, cultural differences show up most point-

edly when the course emphasis is on major fi gures in the history of economic

thought. Table

1.3 shows a ranking of economists most often mentioned in course

Table 1.3 Ranking of economists

In German course titles In Anglo-American journals

Marx Smith

Schumpeter Keynes

List Ricardo

Smith Malthus

Keynes Marshall

Müller Walras

Fichte, Petty, Ricardo Knight, Veblen

Fisher

Schumpeter, Cournot, Quesnay

Wicksell, J. B. Clark

Pareto

Table 1.2 Purposes and course titles

Category Number of courses

General 191

Periods in the history of thought 72

The history of thought of subdisciplines 57

Focus on particular economists 31

Special problems 17

Other 8

8

Werner W. Pommerehne, Friedrich Schneider, Guy Gilbert and Bruno S. Frey ( 1984 ) , “Concordia

discors: Or: What do economists think?” Theory and Decision 16.3, pp. 251–308. This cultural

difference also shows up in the difference between the German and the English edition of

Recktenwald’s collection of biographical essays of major economists.

5

1 Introduction

titles and, for purposes of comparison, a ranking drawn from a publications analysis

undertaken by Stigler and Friedland (

1979 ) and de Marchi and Lodewijks ( 1983 ).

In the period under consideration, the fi rst place in German course titles takes

Marx.

9

He does not fi gure in de Marchi and Lodewijk’s ( 1983 ) study, since they

consider Marx and Marxism as a subject area. If the numbers attributed to this sub-

ject area were attributed to the man, he would rank fi rst in the American sample, too.

Rudolph (

1984 ) , in the preface to his important study on Rodbertus,

10

lists the fol-

lowing reasons that justify research in the history of thought from a Marxist point of

view: (1) to counter attempts at falsifying the historical record, undertaken by the

enemies of progress (p. 7); (2) to uncover, preserve, and continue the progressive

elements in our intellectual heritage (p. 7); (3) to make a contribution to the proto-

history of sources and elements which Marx and Engels used for their revolutionary

doctrine of scientifi c socialism (p. 9); and (4) Marxist social theory has reached a

level of modernity and differentiation which requires new studies using refi ned

methods of historical research (p. 11), for instance, the use of “the high art of cita-

tion” in which “Marx was a master.” (p. 13)

As I have mentioned earlier, this study cannot be duplicated for the United States.

However, it is readily apparent that research in the history of economic thought is

undertaken by American and European scholars alike for reasons other than l’art

pour l’art . This shows up when we look at the combination of research areas most

often noted by historians of economic thought according to the AEA Handbook

(1981). If the marginal products of research in the history of thought were invariant

with the variation of secondary research areas, a stochastic distribution should be

expected. Our count, however, is shown in Table

1.4 .

Again, this result is only indicative of some interesting patterns along which

historical research of economics proceeds. The selection of authors made in this

book is complete as far as the Anglo-American approach is concerned, but adds the

continental European perspective.

9

East German universities were excluded from the survey.

10

Rudolph, Günther (1984), “ Karl Rodbertus (1805–1875) und die Grundrententheorie: Politische

Ökonomie aus dem deutschen Vormärz. ” Berlin: Akademie (Akademie der Wissenschaften der

DDR – Schriften des Zentralinstitutes für Wirtschaftswissenschaften Nr. 21).

Table 1.4 Rankings of second research area

General economic theory 131

Economic history 45

Economic systems 33

General economics 31

Domestic monetary theory, etc. 13

Economic growth, etc. 10

Industrial organization, etc. 9

Economic education 6

Domestic fi scal policy, public fi nance 6

Not available 6

6 J.G. Backhaus

References

Backhaus J (1983) “Theoriegeschichte – wozu? Eine theoretische und empirische Untersuchung.”

Studien zur Entwicklung der ökonomischen Theorie III, H. Scherf, ed. Berlin: Duncker &

Humblot (Schriften des Vereins für Socialpolitik, N.V. 115 III)

Backhaus J (1986) History of economic thought – what for? Empirical observations from German

Universities. Hist Econ Soc Bull VII/2:60–66

Breit W, Ransom R (1982) The academic scribblers. The Dryden Press, Chicago

de Marchi N and Lodewijks J (1983) HOPE and the Journal Literature in the History of Economic

Thought. Hist Polit Econ 15(3):321–343

Neumark F (1975) Zyklen in der Geschichte ökonomischer Ideen. Kyklos 29(2):257–258

Perlman M, McCann C (2000) The pillars of economic understanding: factors and markets. The

University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor

Pommerehne WW, Schneider F, Gilbert G, Frey BS (1984) Concordia discors or: what do econo-

mists think? Theory Decis 16(3):251–308

Recktenwald HC (1965) Lebensbilder großer Nationalökonomen. Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Köln

Röpke W (1933) Trends in German business cycle policy. Econ J XLIII/171:427–441

Rudolph G (1984) Karl Rodbertus (1805–1875) und die Grundrententheorie: Politische Ökonomie

aus dem deutschen Vormärz. Akademie, Berlin (Akademie der Wissenschaften der DDR –

Schriften des Zentralinstitutes für Wirtschaftswissenschaften Nr. 21)

Samuels W (1974) History of economic thought as intellectual history. Hist Polit Econ

6:305–322

Schultz B (1960) Die Geschichte der Volkswirtschaftslehre im Lehrbetrieb deutscher Universitäten

und einiges zur Problematik. In: Stammer O, Thalheim KC (eds) Festgabe für Friedrich Bülow

zum 70. Duncker & Humblot, Geburtstag, pp 343–362

Schumpeter JA (1948/1949) Some questions of principle. Unpublished introduction to his History

of Economic Analysis

Schumpeter JA (1954) History of economic analysis. Oxford University Press, New York

Stigler G (1969) Does economics have a useful past? Hist Polit Econ 1(2):217–230

Stigler G (1979) Does economics have a useful past? Hist Polit Econ 1(2):217–230

Stigler G, Friedland C (1979) The pattern of citation practices in economics. Hist Polit Econ

II(1):1–20

Walker D (1983) Biography and the study of the history of economic thought. Res Hist Econ

Thought Methodol 1:41–59

Yeager L (1981) Clark Warburton 1896–1979. Hist Polit Econ 13(2):279–284

7

JG B kh ( d) HdbkfhHi fE iTh h

C. P. Baloglou (*)

Hellenic Telecommunications Organization,

S.A. Messenias 14 & Gr. Lamprakis , 143 42 Nea Philadelphia , Athens , Greece

e-mail: [email protected]

Chapter 2

The Tradition of Economic Thought

in the Mediterranean World from the Ancient

Classical Times Through the Hellenistic

Times Until the Byzantine Times

and Arab-Islamic World

Christos P. Baloglou

Cicero

Xenophon

8 C.P. Baloglou

Introduction

Since modern economics is generally considered to have begun with the publication

of Adam Smith’s An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations in

1776 , a survey and investigation of pre-Smithian economic thought requires some

justifi cation. Such an effort must offer both historical and methodological support

for its contribution to the study of the history of modern economics.

Most of the histories of economics that give attention to the pre-Smithian

background ignore the economic thought of Hellenistic and Byzantine Times, as

well as Islamic economic ideas, although the Mediterranean crucible was the parent

of the Renaissance, while Muslim learning in the Spanish universities was a major

source of light for non-Mediterranean Europe. Another motivation, and a bit more

fundamental, has to do with the “gap” in the evolution of economic thought alleged

by Joseph Schumpeter (1883–1950) in his classic, History of Economic Analysis

(1954): “The Eastern Empire survived the Western for another 1,000 years, kept

going by the most interesting and most successful bureaucracy the world has ever

seen. Many of the men who shaped policies in the offi ces of the Byzantine emperors

were of the intellectual cream of their times. They dealt with a host of legal, monetary,

commercial, agrarian and fi scal problems. We cannot help feeling that they must

have philosophized about them. If they did, however, the results have been lost.

Aristotle

Socrates

9

2 The Tradition of Economic Thought in the Mediterranean World…

No piece of reasoning that would have to be mentioned here has been preserved.

So far as our subject is concerned we may safely leap over 500 years to the

epoch of St. Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274), whose Summa Theologica is in the

history of thought what the southwestern spire of the Cathedral of Chartres is in

the history of architecture.”

1

Schumpeter classifi ed several pre-Latin-European

scholastic centuries as “blank,” suggesting that nothing of relevance to economics,

or for that matter to any other intellectual endeavor, was said or written anywhere

else. Such a claim of “discontinuity” is patently untenable. A substantial body of

contemporary social thought, including economics, is traceable to Hellenistic, Arab-

Islamic, and Byzantine “giants.”

Our purpose of this essay is to explore and present the continuity of the economic

thought in the Mediterranean World from the Classical Times until the Byzantine

and Arab-Islamic world. In order to facilitate the reader’s appreciation and compre-

hension of this long period, the essay will open with an introductory section describ-

ing the signifi cance of the Greek economic thought compared to the ideas of the

other people lived in Mediterranean era. Following upon this general introduction,

the essay deals with the economic thought and writings of the Classical Period in

Greece (see section “The Classical Greek Economic Thought”).

The economic thought during the Hellenistic period (323–31 bc ) has not been

studied extensively. Histories of economic thought, when they refer to ancient

thought, usually pass directly from Aristotle or his immediate successors to

medieval economic Aristotelianism. It would seem that ancient economic thought,

having reached its zenith in Aristotle’s Politics , disappeared, only to reappear as a

catalyst for the refl ections of medieval commentators. However, we show that sev-

eral Hellenistic schools do refer to economic problems (see section “Economic

Thought in Hellenistic Times”).

The Roman writers do belong in the tradition of the European intellectual life.

Economic premises and content of Roman law evolved into the commercial law of

the Middle Ages and matured into the Law Merchant adopted into the Common

Law system of England on a case-by-case basis, primarily under the aegis of Lord

Mansfi eld, Chief Justice of the Court of King’s Bench, 1756–1788 (see section

“The Roman Heritage”).

2

The economic ideas of the Roman philosophers, and particularly of Plato and

Aristotle against usury and wealth, infl uenced the Christian Fathers of the East, who

belong to the Mediterranean tradition. Their aim is broadly to refl ect upon the

first- and second-generation Church literature to provide assistance in dealing

with the new and baffl ing range of problems with which the Church of their day

was confronted. Of considerable importance among the issues which the Fathers

faced was the problem of the unequal distribution of wealth and similar related

economic issues.

3

They refl ected heavily in their works the ideas of the classical

Greek philosophers.

1

Schumpeter ( 1954 [1994], pp. 73–74).

2

Lowry ( 1973, 1987b , p. 5).

3

Karayiannis and Drakopoulos-Dodd ( 1998 , p. 164).

10 C.P. Baloglou

Another central issue of the Byzantine History was that the scholars did get

occupy of the social and economic problems of the State. The ideology of these

scholars remained constantly in the patterns of the “Kaiserreden” (speeches to

Emperors), which were written systematically in the fourteenth and fi fteenth

century (see section “The Byzantine Economic Thought: An Overview”).

4

While the infl uence of Islamic science and mathematics on European develop-

ments has been widely accepted, there has been a grudging resistance to investigate

cultural infl uences; the troubadour and “courtly love” tradition is a case in point. We

tend to forget that the court of Frederick II in the “Two Sicilies” in the twelfth cen-

tury held open house for Muslim, Christian, and Jewish scholars. Also, there was

the sustained Spanish bridge between North Africa and Europe that maintained cul-

tural interaction through the Middle Ages when many scholastic doctors read

Arabic.

5

The main characteristic of the Islamic economic thought is that the Greek

and Iranian heritages fi gure most prominently in its literary tradition (see section

“Arab-Islamic Economic Thought”).

The Classical Greek Economic Thought

About 5,000 years ago, the Mediterranean region became the cradle of a number of

civilizations. Egypt, Mesopotamia, Syria, and Persia fi gure in the history books as

creative incubators of our cultural heritage. Their palace and temple complexes

were of an unparalleled grandeur and arouse our awe even today. Their civilizations

had relatively developed economies, with surplus production effi ciently mobilized

and redistributed for the administrative and religious establishment. Their scribal

schools produced a great number of manuals with detailed instructions for the run-

ning of the complex system. But, in their compact worldview, there was no space for

an autonomous body of political thought and still less for one of economic thought.

6

Classical Greece made a quantum leap in the humanization of arts and philosophy.

Its rationalism came as a challenge to the mythical worldview and to the religious

legends and liturgies. Aristotle states that very precisely and appropriately by the

following sentence: “ o i Έ l l h n e V d i a t o f e ύ g e i n t h n ά g n o i a n e f i l o s ό f h s a n

[…] d i a t o e i d έ n a i t o e p ί s t a s q a i e d ί w k o n k a i o u c

r ή s e ώ V t i n o V έ n e k a ”

( Metaphysics A 983 b11).

The Greek rhetoricians and scholars were also the fi rst to write extensively on

problems of practical philosophy like ethics, politics, and economics. This is proved

4

van Dieten ( 1979 , pp. 5–6, not. 16).

5

Lowry ( 1996 , pp. 707–708).

6

Baeck (1997, p. 146). It is evident that we meet descriptions of economic life and matters in

Zoroaster’s law-book and in the Codex Hammurabi. Cf. Kautz (

1860 , pp. 90–91). In the Talmudic

tradition, the ethical aspect of the labor has been praised. Cf. Ohrenstein and Gordon (

1991 ,

pp. 275–287). For an overview of the economic ideas of the population round the Mediterranean,

see Spengler (

1980 , pp. 16–38) and Baloglou and Peukert ( 1996 , pp. 19–21).

11

2 The Tradition of Economic Thought in the Mediterranean World…

by the works entitled “On wealth (peri ploutou)” and “On household economics (peri

oikonomias).” In the post-Socratic demarcation of disciplines, ethics was the study of

personal and interindividual behavior; politics was the discourse on the ordering of

the public sphere; and the term oikonomia referred to the material organization of the

household and of the estate, and to supplementary discourses on the fi nancial affairs

of the city-state (polis-state) administration. Greek economic thought formed an

integral but subordinated part of the two major disciplines, ethics and politics. The

discourse of the organization of the Oikos and the economic ordering of the polis was

not conceived to be an independent analytical sphere of thought.

7

Homo Oeconomicus: Oikonomia as an Art Effi ciency

The word “Oikonomia” comes from “Oikos” and “nemein.” The root of the verb

“ n έ m e i n (nemein)” is nem ( n e m -) and the verb “nemein” which very frequently appears

in Homer means “to deal out, to dispense.” From the same root derive the words n o m ή,

n o m e ύ V (a fl ock by the herdman), and n έ m e s i V (retribution, i.e., the distribution of

what is due). This interpretation comes from Homer’s description of the Cyclops, who

were herdmen ( n o m e ί V ) ( H omer, Odyssey , ix, 105–115). According to J.J. Rousseau

(1712–1778), the second word means decreeing of rules legislation: “The word econ-

omy comes from o ί k o V , house, and from n ό m o V , law, and denotes ordinarily nothing

but the wise and legitimate government of the house for the common benefi t of the

whole family. The meaning of the term has later been extended to the government of

the great family which is the state.”

8

This term means Household Management – the

ordering, administration, and care of domestic affairs within a household; husbandry

which implies thrift, orderly arrangement, and frugality, and is, in a word, “economi-

cal.” Here, in the primary sense of the root, oikonomos ( o i k o n ό m o V ) means house

manager, housekeeper, or house steward; oikonomein ( o i k o n o m e i n ) means “to man-

age a household” or “do household duties,” and oikonomia ( o i k o n o m ί a ) refers to the

task or art or science of household management.

9

According to Aristotle, the second

word has the meaning of arrangement, and consequently, their harmonization for their

better result (Aristotle, Politics I 10, 1258 a21–26).

The epic “Works and Days” seems to have been built around the central issue of

economic thought: the fundamental fact of human need ( Works and Days , 42ff). It

follows the implications of that primordial fact into all its ramifi cations in the life of

a Greek peasant. The problem, Hesiod teaches his brother, is to be solved not by

means that nowadays would be labeled as “political” by force and fraud, bribery,

and willful appropriation, but by incessant work in fair competition, by moderation,

honesty and knowledge of how and when to do the things required in the course of

seasons ( Works and Days , 107–108), how to adjust wants to the resources available

7

Baeck (1994, pp. 47–49).

8

Rousseau ( 1755 , pp. 337–349 [1977, p. 22]).

9

Reumann ( 1979 , p. 571).

12 C.P. Baloglou

( Works and Days , 231–237), and above all, how to shape attitudes and actions of

all men (and the more diffi cult problem: women) in order that a viable, enduring

pattern of peaceful social life may be established which assigns to every part its

place in a well-ordered whole. It is worth noting, too, that the famous verse ( Works

and Days , 405) “First of all, get an Oikos, and a woman and an oxforthe plough,”

which crystallizes the deeper sense of the term “oikonomia” in its original primal

meaning, will be repeated and quoted by Aristotle ( Politics I 2, 1252 b11–13) and

the author of the work “Oeconomica” (A II, 1343 a18). Righteously then, according

to our point of view, Hesiod is acknowledged as the founder of the so-called

“Hausväterliteratur,”

10

the literature which studies the householding, the housekeep-

ing, and extends until the Roman agricultural economists.

11

Phokylides of Milet, in the second half of the sixth century bc , is the fi rst to men-

tion economists. In an elegant poem, he compares women to animals: to dogs, bees,

wild pigs, and to long-named mares, to which different characteristics are assigned.

Naturally, the bee is the best housekeeper and the poet prays that his friend can lead

such a woman to a happy marriage.

12

In the same manner, Semonides of Amorgos

(ca. 600 bc ) presents in his elegant poem entitled “Jambus of Women”

13

several

types of women who come from different animals. The best type of woman is only

those who come from the bee.

14

He will emphasize the good behavior of a woman,

because she contributes on the welfare of the Oikos.

15

From Pittakos of Lesbos, one of the Seven Wise Men, comes the word of the

“unfufi llable lust for profi t” (DK 10 Fr. 3e 13); also here is found the earliest usage

of the word oikonomia for “household education” (DK 10 Fr. 3e 13, verse 19), a

passage, which has not been well studied,

16

as far as we know. We need to consider

that the previous verses belong to a testimonium and not to a fragment of a particu-

lar work of Pittacus.

From the other presocratic philosophers, Democritus, who was “the most multi-

faceted and learned” philosopher before Aristotle ( Diog. Laert. I 16), wrote a book

on agriculture as the Roman agricultural economists Varro ( De re rustica I 1, 8) and

Columella ( De re rustica , praef. 32 III, 12, 5) tell us. Columella quotes him as say-

ing that “those who wall in their gardens are unwise, because a fl imsy wall will not

survive the wind and rain, while a stone will cost more to build than the wall itself

is worth” (Columella, De re rustica XI 3, 2). This is at least an early sign of the

weighing of (objective) utility and costs.

10

Brunner ( 1968 , pp. 103–127).

11

Brunner ( 1949, 1952 ) .

12

Diehl ( 1949 , Fasc. 1, Fr. 2, Vv. 1–2, 6–7). Cf. Descat ( 1988 , p. 105).

13

Diehl ( 1949 , Fasc. 3, Fr. 7). Cf. Kakridis ( 1962 , p. 3–10).

14

Diehl ( 1949 , Fasc. 3, Fr. 7, Vv. 84–87, 90–91).

15

Diehl ( 1949 , Fasc. 3, Fr. 6). This idea borrows Semonides from Hesiod, Works and Days , Vv.

102–103.

16

For exceptions, see Schefold ( 1992, 1997 , p. 131), Maniatis and Baloglou ( 1994 , pp. 23–24), and

Baloglou (

1995 ) .

13

2 The Tradition of Economic Thought in the Mediterranean World…

The words we have of Democritus, directly with respect to the household, show

that while he held to the general understanding of the household maintenance, he

advocated a posture of greater freedom in role fulfi llment than Plato.

17

Even a brief

look into the fragments on politics and ethics

18

show that – in comparison with

Plato’s position – he held to a creed of democracy (DK 68 B 251) and liberal thinking

(DK 68 B 248). He also refers to the job of the rich in democratic politics, to

contribute spontaneously to the good of the community. He emphasized the necessity

of education for the right use of wealth (DK 68 B 172). The family is to lead by

example (DK 68 B 208). In general, there is more to be achieved through “encour-

agement and conceiving words” than through “law and force.” He felt that force

leads to the concealment of wrong-doing (DK 68 B 181).

Democritus

19

seems to be the fi rst philosopher who gives an extensive description

of the appearing of labor, in the form as collection, transportation, and storing of

fruits.

20

To these two simultaneous achievements, the storing of wild fruit and plant

food and taking shelter in caves in winter, to the starting point in brief in economy

and ecology, are attributed the beginning of History, although its introduction into the

life of primitive people was gradual, as they learned from “experience.”

The idea of house management is common enough that it can be referred to again

and again in a variety of ways in Greek literature. Lysias, the orator of the later fi fth

century bc , can praise the wife of one of his clients for having been at the start of

their marriage a model housewife: “At fi rst, O men of Athens, she was best of all

women; for she was both a clever household manager (oikonomos) and a good,

thrifty woman, arranging all things precisely” (Lysias, On the Murder of Eratosthenes , 7).

Targic and comic poets give some insight into the daily life and tasks of household

managers-wives, or slaves employed in such a capacity.

21

The Socratic Evidence

The use of the term “oikonomia” by Socrates verifi es that in the circle of his disciples

there were discussions around managing affairs of the Oikos. This proves the work

entitled Peri Nikes Oikonomikos given by Diogenes Laertius (VI 15) in the biography

of Antisthenes. It is the fi rst work with this title in the Greek literature.

Antisthenes (ca. 450–370) was preoccupied with the problem of managing of

house-property, as it is pointed out by the titles of the works On Faith ( peri pisteos )

17

Schefold ( 1997 , p. 106).

18

Vlastos ( 1945 , pp. 578–592).

19

For a more detailed analysis of Democritus’ economic ideas, see Karayiannis ( 1988 ) and

Baloglou (

1990 ) .

20

Despotopoulos ( 1991 , pp. 31–51, 1997 , pp. 53–56).

2 1

Sophocles, Electra 190; Aischylos, Agamemnon 155; Alexis, Crateuas or the Medicine Man 1.20,

in Kock

1880–1888 , vol. 2, F. 335; An unknown comic poet in Kock 1880–1888 , vol. 3, F. 430.

Cf. also Horn (

1985 , pp. 51–58).

14 C.P. Baloglou

and On the Superintendant ( peri tou epitropou ) (Diog. Laert. VI 15). It has been

supported

22

that he infl uenced Xenophon in writing his “Oeconomicus.”

By analyzing the proper economic actions, activities, pursuits, and responsibilities

of the head of the Oikos, Xenophon developed interesting ideas “framed in terms of

the individual decision-maker.”

23

Xenophon uses as an example of good organiza-

tion, management, administration, and control that exercised by the queen-bee. He

mentions that the leader of the Oikos (kyrios) must organize and control the work

done by his douloi and laborers and then distribute among them a part of the product

as the queen bee does ( Oeconomicus VII 32–34). He sets forth the Socratic idea that

if you can fi nd the man with a ruling soul, the archic man, you had better put him in

control and trust his wisdom rather than the counsels of many.

After dealing with the content and scope of “oikonomia,” Xenophon empha-

sized that every social agent acts as an entrepreneur-manager or as an administra-

tor of the Oikos and is interested in the preservation and augmentation of the

possessions of his Oikos: “the business of a good oikonomos (kalos kagathos) is

to manage his own estate well” ( Oeconomicus I 2). The master, however, may as

the Xenophontic Socrates observes, entrust another man with the business of

managing his Oikos. This seems to introduce another way of being an “Oikonomos,”

but one thoroughly familiar to an Athenian of that epoch, for Critoboulos instantly

agrees “Yes of course; and he would get a good salary if, after taking on an estate

(ousia), by showing a balance (periousia)” ( Oeconomicus I 4).

24

Evidently, this

delegated function has a narrower scope than that of the householder-master (des-

potes). It is related to payments and receipts and seems akin to moneymaking, for

success is measured by the attainment of a “surplus” (periousia). This does not

necessarily imply a capitalistic style of economic organization, but it shows how

fl uid the boundary between farming in sustenance and for profi t had become and

it talks of chrematistics and economy,

25

as if they were neighbors rather than

opposites – in contrast to Aristotle from whom the two modes of economic life are

divided by a chasm.

It would have been a serious omission not to mention that the worship of God

by members of “Oikos” is a part of “oikonomia” ( Oeconomicus V 19, 20). That

particular characteristic of the Ancient Greek Oikos distinguishes is from the

modern one.

Many examples can be cited of the Greeks’ concern for the effi cient management

of both material and human resources. Xenophon’s Banquet is an anecdotal account

2 2

Vogel ( 1895 , p. 38), Hodermann ( 1896 , p. 11; 1899 , ch. 1), Roscalla ( 1990 , pp. 207–216),

and Baloglou and Peukert (

1996 , pp. 49–53).

23

Lowry ( 1987a , p. 147).

24

Karayiannis ( 1992 , p. 77) and Houmanidis ( 1993 , p. 87).

25

As Lowry ( 1987c , p. 12) comments: “The Greek art of oikonomia, a formal, administrative art

directed toward the minimization of costs and the maximization of returns, had as its prime aim the

effi cient management of resources for the achievement of desired objectives. It was an administra-

tive, not a market approach, to economic phenomena.” See also Lowry (

1998 , p. 79).

15

2 The Tradition of Economic Thought in the Mediterranean World…

of the “good conversation” associated with the leisurely eating and drinking and

subsequent entertainment that accompanied the formal dinner. But Socrates’

remarks to the Syracusan impresario who provided the dancing girls and acrobats

for the entertainment were not about their skill or grace, but about the “economics”

of entertainment. “I am considering,” he said, “how it might be possible for this lad

of yours and this maid to exert as little effort as may be, and at the same time give

us the greatest amount of pleasure in watching them-this being your purpose, I am

sure” ( Banquet VII 1–5).

In his effort to interpret the term “oikonomia,” Xenophon describes extensively

the three kinds of relationships between the members of the Oikos:

1. The relationship between husband and wife: gamike ( Oeconomicus VII 3, 5, 7,

8, 22–23, 36).

2. The relationship between father/mother and children: teknopoietike ( Oeconomicus

VII 21, 24).

3. The relationship between the head of household (kyrios) and domestic slaves

(douloi) ( Cyropaedia B II 26; Oeconomicus XIII 11–12; XXI 9; IV 9).

The description of the occupations in the Oikos and the relations between its members

states precisely the content of the term “oikonomia.” Xenophon will infl uence

Aristotle, and the latter will analyze the meaning of the term “oikonomia.”

The Oikos in the Aristoteleian Tradition

The objective of politics is to specify the rhythm of common political life in such a

frame that would enable the man who lives in Politeia to enjoy happiness (eudaimo-

nia) respective to his nature. Politics is projected against the other assisting “sci-

ences, arts,” such as strategike, oikonomike, and rhetorike (Aristotle, Nicomachean

Ethics I 2, 1094 a25–94 b7). This happens because man is an inadequate part of the

political whole and is unable to sustain his existence and achieve his perfection.

Aristotle believes that the political community ontologically has absolute priority

over any person or social formation: “Thus also the polis is prior in nature to the

Oikos and to each of us individually. For the whole must necessarily be prior to the

part” ( Politics I 2, 1253 a19–21). According to the ancient political thought, as

Aristotle expresses it, man is primarily a “political animal (zoon politikon)” ( Politics

I 2, 1253 a3–4; Nicomachean Ethics I 7, 1097 b11; 9, 1169 b18–19).

Apart from this dimension, man as a member of a “politeia which is called the

life of a statesman (politicos), a man who is occupied in public affairs” (Plutarch,

Moralia 826D), he has another dimension as a member of the Oikos. That is why

the Stageirite calls him “economic animal”: “For man is not only a political but also

a house-holding animal (oikonomikon zoon), and does not, like the other animals,

couple occasionally and with any chance female or male, but man is in a special way

not a solitary but a gregarious animal, associating with the persons with whom he

has a natural kinship” (Aristotle, Eudemeian Ethics VIII 10, 1242 a22–26).

16 C.P. Baloglou

This characterization introduced by Aristotle has not been mentioned by the most

authors

26

; it is, however, of primal importance for the understanding of the parts of

the Oikos.

Aristotle recognizes the three relationships in the Oikos:

1. Master and doulos-oiketes (household slave): despotike

2. Man and wife: gamike

3. Father and children: teknopoietike

These three relationships and the existence of a budget consist of the “economic

institution” (oikonomikon syntagma).

27

The Oikos is the part of the whole, of the Polis, and the relationships of the

members of the Oikos are refl ected in the forms of government (Aristotle, Politics

I 13, 1260 b13–15; Idem, Eudemeian Ethics VIII 9, 1241 b27–29). Therefore, the

relationship of the man and wife corresponds to the aristocracy ( Eudemeian Ethics

VIII 9, 1241 b27–32), the relationship of the father and children to kingship ( Politics

I 12, 1259 b11–12), and the relationship of the children corresponds to democracy

(politeia) ( Eudemeian Ethics VIII 9, 1241 b30–31). The relationship between master

and doulos-oiketes consists of an object of the so-called, “despotic justice,” which

differs from the justice that regulates the relations of the members of the Polis

and from the justice that rules the relationships of the citizens of an oligarchic or

tyrannic government ( Nicomachean Ethics V 10, 1134 b11–16; Great Ethics I 33,

1194 b18–20).

It is worth to note that Hegel presents in the Third Part of his work Philosophie

des Rechtes the tripartite division Familie, Bürgeliche Gesellschaft, Staat, in a

distinct manner as we believe, corresponding to the aristoteleian tripartite distinc-

tion: Oikos, Kome, Polis. Such division characterizes deeply the trends of the

sociology of the nineteenth century, this tripartite Hegelian theory of society.

28

Aristotle tells the reader that each relationship has a naturally ruling and ruled

part – even the procreative relationships are informed by subjuration. Accordingly,

the only unsubjurated part, one which Aristotle separates from the other three, is the

fourth part of the Oikos, the art of acquisition (ktetike). Its concern is not with

subjuration, but with acquisition or accumulation.

29

Aristotle proceeds to a discussion of the kinds of acquisition and the ways of life

from which they follow. He selects the word “chrematistic” to convey his meaning

of the natural art of acquisition. According to several commentators of the Politics ,

the word while inexact, “often means money and is always suggestive of it.”

30

26

For an exception, see Kousis ( 1951 , pp. 2–3) and Koslowski ( 1979a , pp. 62–63). Cf. also

Koslowski (

1979b ).

27

Rose ( 1863 , p. 181, Fr. XXXIII).

28

Despotopoulos ( 1998 , p. 96).

29

Brown ( 1982 , pp. 17–172).

30

Newman, vol. I ( 1887 , p. 187) and Polanyi ( 1968 , p. 92): “Chrematistike was deliberately

employed by Aristotle in the literal sense of providing for the necessaries of life, instead of

its usual meaning of ‘money-making.’” See Barker (

1946 , p. 27). See an extensive analysis in

Egner (

1985 , ch. 1).

17

2 The Tradition of Economic Thought in the Mediterranean World…

At this point, we should mention something that gets usually disregarded by

most of the authors. The term “chrematistike” is found originally in Plato: “Nor, it

seems, do we get any advantage from all other knowledge (episteme), whether of

money-making (chrematistike) or medicine or any other that knows how to make

things, without knowing how to use the thing made” (Plato, Euthydemus 289A).

This term denotes this “episteme” (science) that relieves people from poverty; in

other words, “it teaches them how to get money” (Plato, Gorgias 477 E10–11; 478

B 1–2). It is not without worth to note that Plato places chrematistics parallel to

medicine [cf. Plato, Euthydemus 289A; idem, Politeia 357 c5–12; idem, Gorgias

452a2, e5–8, 477 e7–9]. This emphasizes the fact that both “chrematistics” and

“medicine” are “arts” (sciences), which have as target the support of the traditional

goods: the external goods (wealth), the body (health). This widely accepted view of

the parallel setting of medicine and chrematistics is adopted also by Aristotle

( Politics I 9, 1258 a11–15; 10, 1258 a28–30; idem, Eudemeian Ethics I 7, 1217

a36–39; Nicomachean Ethics III 5, 1112 b4–5).

Simultaneously, in the dialog Sophist the kinds of “chrematistike” are explored.

The acquisition (ktetike techne) is contrasted in “poietike” and subdivided in the divi-

sion of hunting and of exchange, the latter in two sorts, the one by gift, the other by

sale. The exchange by sale is divided into two parts, calling the part which sells a

man’s own productions the selling of one’s own (autourgon autopoliken), and the

other, which exchanges the works of others, exchange (allotria erga metavallomenen

metavletiken), which is subdivided in “kapelike” (part of exchange which is carried on

in the city) and “emporia” (exchanges goods from city to city) (Plato, Sophist 219 b,

223c–224d). These activities have a different moral evaluation: it is better to construct

(poietike) rather than to acquire (ktetike); better to gain from nature than from transac-

tions with others; better to offer than participate in the market. The method of working,

the objectives, and the tools are the criteria for a classifi cation which later in the work

forms the basis for the treatment of the sophist (Plato, Sophist 219a-d).

31

Aristotle, obviously infl uenced by Plato’s analysis, distinguishes the three kinds

of acquisition.

The fi rst kind – “one kind of acquisition therefore in the order of nature is a part

of the household art (oikonomike)” ( Politics I 11, 1256 b27) – is the acquisition

from nature of products fi t for food ( Politics I 11, 1258 a37), which is to be added

as simple barter of these things for one another, which is the good metabletike.

Similar to this kind of acquisition is the “wealth-getting in the most proper sense

(oikeiotate chrematistike) (the household branch of wealth-getting)” ( Politics I 11,

1258 b20) – whose branches are agriculture – corn-growing and fruit-farming –

bee-keeping, and breeding of the other creatures fi nned and feathered ( Politics I 11,

1258 b18–22).

32

31

Hoven van den ( 1996 , p. 101).

32

Susemihl and Hicks ( 1894 , p. 171 and 210). Maffi ( 1979 , p. 165) against Polanyi’s thesis;

Pellegrin (

1982 , pp. 638–644), Venturi ( 1983 , pp. 59–62), Schefold ( 1989 , p. 43), and Schütrumpf

(

1991 , pp. 300–301).

18 C.P. Baloglou

The second kind is trade in general, kapelike, synonym with metabletike in the

narrower sense or chrematistics in the narrower sense ( Politics I 9, 1256 b40–41), in

which Aristotle thinks men get their profi t not of nature, but out of one another and

so unnaturally ( Politics I 10, 1258 b1–2: “for it is not in accordance with nature, but

involves, men’s taking things from one another.”)

The third kind is, like the fi rst, the acquisition from nature of useful products, but

the products are not edible. Aristotle calls this kind “between” the latter and the one

placed fi rst, since it possesses an element both of natural wealth-getting and of the

sort that employs exchange; it deals with all the commodities that are obtained from

the earth and from those fruitless, but useful things that come from the earth ( Politics

I 11, 1258 b28–31).

The wealth which is the object of the second kind, consisting of money ( Politics I

1257 b5–40), is unnatural as contrasted with the “wealth by nature” (ploutos kata

physin) of the fi rst kind ( Politics I 1257 b19–20), and the commodities which form the

wealth of the third kind are clearly more like the unnatural wealth. To them one might

also apply what is said of money: “[…] yet is absurd that wealth should be of such a

kind that a man may be well supplied with it and yet die of hunger” ( Politics I 8, 1257

b15–16). Furthermore, the fi rst kind of acquisition is more natural than the third in the

sense that “natural” is opposed to “artifi cial” rather than to “unnatural.”

33

We have to emphasize the ethical evaluation of the “chrematistike.” Aristotle

does not condemn “chrematistics” as long as it does not go beyond the natural limits

of acquisition of goods ( Politics I 9, 1257 b31ff). For this reason, he calls it “oikono-

mike chrematistike.”

Aristotle’s ideas on “chrematistics” and wealth refl ect a tradition in the Greek

thought which is found in the Lyric poets, such Sappho, Solon, Theognis, and in

classical tragedy (Sophocles, Antigone 312).

34

He makes clear that this search for

profi t (kerdos) is not denounced with respect to any specifi c method of earning

wealth, but to the general hoarding of wealth (Sophocles, Antigone , 312). The

expression “argyros kakon nomisma” (295–296), used by Creon, shows the ethical

aversion of the excessive wealth by the ancient Greek thought. It is not accidental

that Marx

35

does use the same expression, who describes the love for gold and the

thirst of money, two phenomena which are produced with money.

Aristotle’s dinstinction between “necessary” and “unnecessary” exchange and

his dictum in the Politics (I 1257 a15–20) that “retail trade is not naturally a part of

the art of acquisition” have been widely interpreted as a moralistic rejection of all

commercial activity. M.I. Finley (1912–1986), for example, fi nds “not a trace” of

economic analysis in Politics and maintains that in this work Aristotle does not “ever

consider the rules or mechanics of commercial exchange.”

36

On the contrary, he

says, “his insistence on the unnaturalness of commercial gain rules out the possibil-

ity of such a discussion.”

33

Meikle ( 1995 ) .

34

Meyer ( 1892 , p. 110), Stern ( 1921 , p. 6), and Schefold ( 1997 , p. 128).

35

Marx ( 1867 [1962], p. 146).

36

Finley ( 1970 , p. 18).

19

2 The Tradition of Economic Thought in the Mediterranean World…

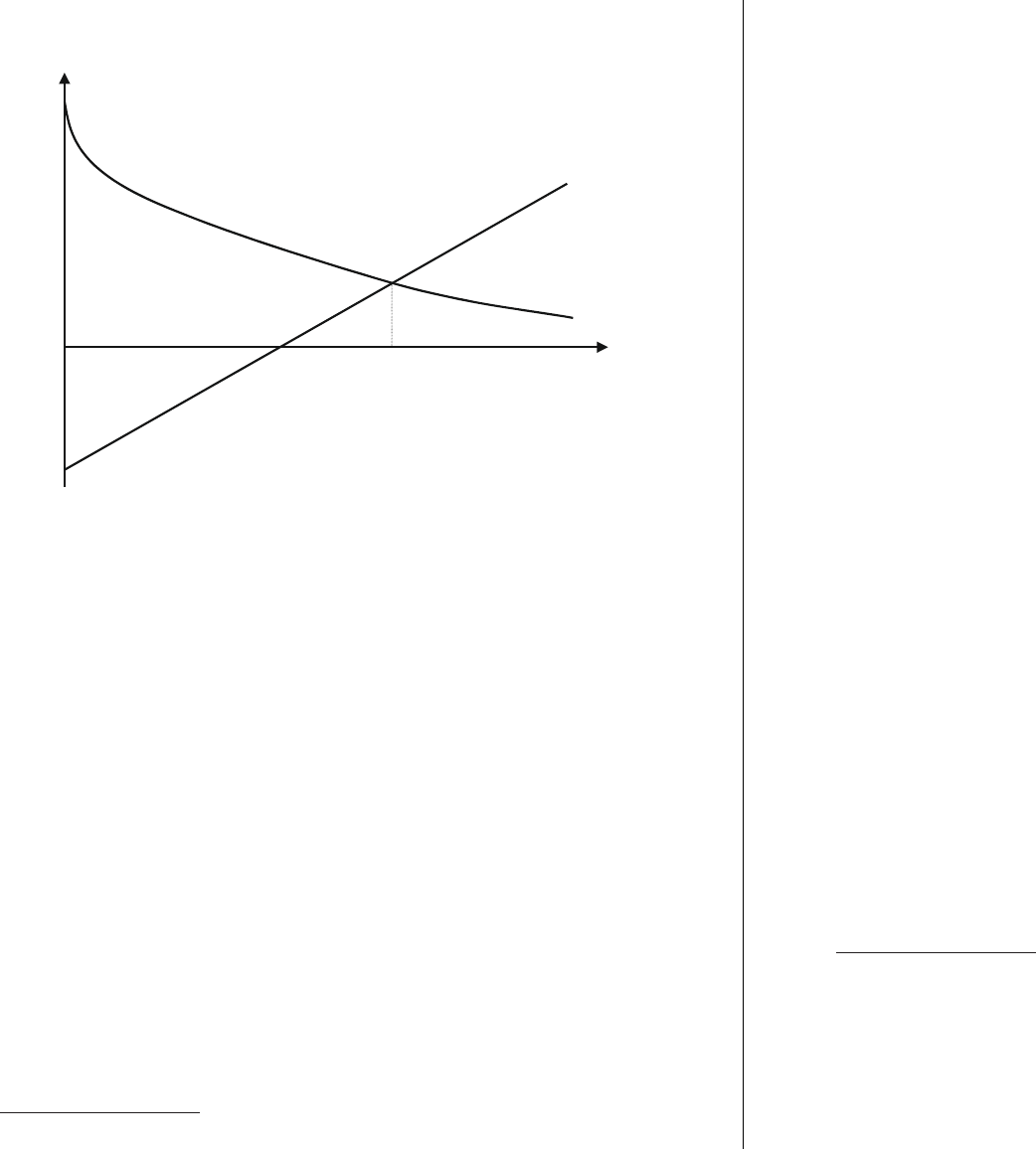

Aristotle’s theory of association in Politics is based upon mutual need satisfaction.

Exchange, Aristotle says, arises from the fact that “some men [have] more, and

others less, than suffi ces for their needs” ( Politics I 1257a). Exchange, however, is

not a natural use of goods produced for consumption. Where barter, the exchange of

commodities for commodities (C-C ¢ ), occurs, goods move directly from the pro-

ducer to the consumer, and Aristotle considered this form of exchange a natural or

“necessary” form of acquisition because he says, it is “subject to defi nite bounds.”

Aristotle viewed exchange with money used as an intermediary (C-M-C ¢ ) as

“necessary” when its ultimate purpose is to acquire items for consumption, because

the desire for goods is then still subject to the natural limit of diminishing utility.

37

He classifi ed retail trade, where money is used to purchase commodities to sell in

order to acquire more money (M-C-M) as an “unnecessary” form of exchange. Its

objective, he says, is not the satisfaction of need, but the acquisition of money which

has no use in and of itself and is therefore not subject to a natural limit of desire, as

he illustrates with the Midas legend ( Politics I 9 1257 b14–15). Further, this form of

acquisition has “no limit to the end it seeks.” It “turns on the power of currency” and

is thus unrelated to the satisfaction of needs. The “extreme example” of “unneces-

sary” or “lower” form of exchange, and a still greater perversion of the exchange

process, Aristotle says, is usury, for it attempts to “breed” money – “currency, the

son of currency.” Usury “makes a profi t from currency itself (M-M ¢ -M″) instead

of making it from the process which currency was meant to serve” ( Politics I 10,

1258 b5–9).

From the Economics of the Oikos to the Economics of the Polis

Sophists, who brought about a new movement of intellectuals in the middle of the

fi fth century bc in Athens, taught how to be virtuous. The knowledge which

Protagoras claims to teach the youth “consists of good judgement (euboulia) in his

own affairs (peri ton oikeion), which shall enable him to order his own house (ten

heautou oikian dioikein), as well as teach him how to gain infl uence in the affairs of

the polis (ta tes poleus), in speech and action” (Plato, Protagoras 318E5–319A2).

A similar formula occurs in Aristophanes’ Frogs (405 bc ), where Euripides in his

great agon with Aeschylus boasts, in a Sophist’s manner, of having helped the

Athenians “to manage all their household better than before (tas oikias dioikein)”

( Frogs , vv. 975ff), by teaching them to ask the “why” and “how” and “what” of even

the smallest things. Both phrases are formed by reduplication and may, to a modern

reader, sound somewhat clumsy.

38

37

The only goods which Aristotle exempts from diminishing utility are “goods of the soul,” physic

goods. “The greater the amount of each of the goods of the soul,” he says, “the greater is its utility”

(Aristotle, Politics 1323b). Cf. Lowry (

1987c , p. 19).

38

Radermacher ( 1921 , pp. 284–286) and Spahn ( 1984 , p. 315).

20 C.P. Baloglou

One can see clearly the subsequence of economic issues and problems of the

Oikos and the Polis, in the dialog between Socrates and Nicomachides, as described

by Xenophon

39

: “I mean that, whatever a man controls, if he knows what he wants

and can get it he will be a good controller, whether he controls a chorus, an Oikos,

a Polis or an army.” “Really Socrates,” cried Nicomachides, “I should never have

thought to hear you say that a good businessman (oikonomos) would make a good

general” (Xenophon, Memorabilia III IV, 6–7).

The view of Socrates that the difference between the Oikos and the Polis lies in

their size, only whereas they are similar to Nature and their parts, gets crystallized

in the following passage from the same dialog between Socrates and Nicomachides,

where Xenophon presents “the best lecture to a contemporary Minister of Finance,”

according to A.M. Andreades (1876–1935)

40

:

Don’t look down on businessmen (oikonomikoi andres), Nicomachides. For the manage-

ment of private concerns differs only in point of number from that of public affairs. In other

respects they are much alike, and particularly in this, that neither can be carried on without

men, and the men employed in private and public transactions are the same. For those who

take charge of public affairs employ just the same men when they attend to their own (hoi

ta edia oikonomountes); and those who understand how to employ them are successful

directors of public and private concerns, and those who do not, fail in both (Xenophon,

Memorabilia III IV, 12).

Plato was also of the opinion that “there is not much difference between a large

household organization and a small-sized polis” and that “one science covers all

these several spheres,” whether it is called “royal science, political science, or sci-

ence of household management” (Plato, Statesman ( Politicus ) 259 b-e). These ideas

of Xenophon and Plato are refuted by Aristotle in the Politics (I 1, 1252 a13–16).

41

A characteristically Xenophontean passage dealing with this generalization of

the administrative process gives us a persuasive view of this practical art ancient as

well as modern times. After the dialog between Socrates and Nicomachides in

“Memorabilia,” Xenophon points out that the factor common to both is the human

element. “They are much alike” he says, in that “neither can be carried out without

men” and those “who understand how to employ them are successful directors of

public and private concerns, and those who do not, fail in both.”

42

In Xenophon already, oikonomikos sometimes suggests being skilled or adept at

fi nance, and this element in the idea grew in the popular Greek understanding of the

concept (Xenophon, Agesilaus 10,

1

) : “I therefore praise Agesilaus with regard to such

qualities. These are not, as it were, characteristic of the type of man who, if he should

fi nd a treasure, would be more wealthy, but in no sense wiser in business acumen.”

39

There are also other examples in the classical tragedy which seem quite interesting, because of

the connection between the issue of managing the Oikos effectively and managing of the Polis. Cf.

Euripides, Electra 386 ff.

40

Andreades ( 1992 , p. 250, not. 3).

41

Schütrumpf ( 1991 , pp. 175–176).

42

See Strauss ( 1970 , p. 87) for a discussion of this passage.

21

2 The Tradition of Economic Thought in the Mediterranean World…

Aristotle had called someone managing the funds of a polis carefully “a steward of

the polis ( t i V d i o i k ώ n o i k o n ό m o V )” (Aristotle, Politics V 9, 1314 b8).

43

The ancient recognition of the primary role of the human element in the success-

ful organization of affairs is a facet we tend to ignore when we approach the ancient

world from our modern market-oriented perspective.

44

They emphasized the impor-

tance of the human variable, of one’s personal effectiveness in achieving a success-

ful outcome in any venture. From this anthropocentric point of view, improving

human skill in the management of an enterprise meant nothing less than increasing

the effi ciency of production. In ancient Greece, the maximization of the human fac-

tor was considered as important as that of any other resource.

45

Apart, however, from the skillful administrative control over men, the Ancient

Greeks provided the fact that the ruler has to have an interest in the public fi nances.

From the conversations of Socrates reported by Xenophon in his Memorabilia , we

learn that the fi nances of the polis of Athens were a subject with which young men

looking forward to political careers might well be expected to acquaint themselves

(Xenophon, Memorabilia III VI).

Management of public fi nance and administration of the Polis have extensively

preoccupied Aristotle. In his letter to Alexander he adopts the term “oikonomein” to

denote the management of the Polis fi nances. (I. Stobaeus, Anthologium ) (hence-

forth Stob. I 36 p. 43,

15

–46,

2

) In Rhetoric , he mentions that among the subjects

concerning which public men should be informed is that of the public revenues.

Both the sources and the amount of the receipts should be known, in order that

nothing may be omitted and any branch that is insuffi cient may be increased. In

addition to this, expenditures should be studied so that unnecessary items may be

eliminated; because people become wealthier not only by adding to what they

have, but also by cutting down their outlay (Aristotle, Rhetoric I 4, 1359 b21–23).

A similar discussion is found in the Rhetoric for Alexander (II 2, 1423 a21–26 and

XXXVIII 20, 1446 b31–36).

It is also worth noting that Demosthenes (fourth century bc ) writes about the

public fi nance. In his speech On Crown , he enumerates a politician’s activities in the

fi nancial sector (Demosthenes, On Crown 309). In the Third and Fourth Philippics

(IV 31–34, 35–37, 42–45, 68–69), the author makes particular proposals of a

fi nancial character which provided the essentials of a plan of fi nance.

46

It is worth

to note that in the period between 338 bc (Battle of Chaironeia) and 323

(Death of Alexander) – where the orator Lycurg

47

was the Minister of Public Finance

43

Reuman ( 1980 , p. 377).

44

Lowry ( 1987a , p. 57, 1987c, 1995, 1998 ) .

45

Trever ( 1916 , p. 9) evidently had this point in mind when he observed that “Aristotle struck the

keynote in Greek economic thought in stating that the primary interest of economy is human

beings rather than inanimate property.” In a conversation between Cyrus and his father in the

Cyropaedia (I VI 20–21), we are presented with the clearest kind of analysis of successful admin-

istrative control over men.

46

Cf. Bullock ( 1939 , pp. 156–159).

47

Conomis ( 1970 ) .

22 C.P. Baloglou

of the Athenian Democracy – specifi c proposals of fi nancial policy were provided

by Aristotle,

48

Hypereides

49

, and the aforementioned Demosthenes. Their target was

a redistribution of wealth inside the polis between the citizens: the best proposal

was to advise the rich to contribute money in order to cultivate the poor land or give

capital to the poor people to develop enterprises (Aristotle, Politics , VI 5, 1360

a36–40).

50

However, while the advice on the surface was to favor the commons, it

was really a prudent suggestion to the wealthier citizens, appealing to the selfi sh

interest to avoid by this method the danger of a discontented proletariat (Aristotle,

Politics VI 5, 1320 a36).

These proposals which set up on the idea that the richer citizens should help the

poor is a common point in the Ancient Greek Thought. It is to underline that long

before the Athenian philosophers and writers, the Pythagorean Archytas of Taras

(governed 367–361 bc ), not only the philosopher-scientist and technician,

51

but also

a skillful political leader both in war and in peace provided in his work P e r ί

m a q h m ά t w n (On lessons) the fact that the wealthier citizens should help the poorer;

by this method, the stasis and homonoia will be avoided, concord will come in the

polis (Stob. IV 1, 139 H).

52

The programme of economic and social policy, which is provided by the afore-

mentioned authors, is included in the fi eld of the policy of the redistribution of

income which has been adopted by Welfare Economics.

53

The main difference

between the proposal of the Ancients and the contemporary procedure lies in the

intervention of the State in recent times, whereas in the Classical Times the richer

people would play the role of the State.

54

In the latter part of the nineteenth century, when histories of economic thought

began to be numerous, various writers discovered that what they called the science

of economics was late in its development, and that in Ancient Times the prevalence

of household industry, the low esteem in which manual labor was held, the slight

growth of commerce, the lack of statistical data, and various other circumstances

brought it about that materials were not provided for the scientifi c study of econom-

ics and fi nance.

55

48

Aristotle, Politics VI 5, 1319 b33–1320 b18. For a comparison between Aristotle’s proposals and

Xenophon’s program in Poroi, cf. Schütrumpf (

1982 , pp. 45–52, esp. pp. 51–52) and Baloglou

(

1998d ) .

49

Hypereides, For Euxenippos , col. XXIII 1–13, col. XXXIX 16–26 (edit. by Jensen 1916 ) .

50

This advice is based on Isocrates’ account of the ways of the rich in Athens in the days of Solon