Palm oil

Barometer

2022

The inclusion of smallholder farmers in the value chain

stages

smallholder

farmer groups

plantations

Indepent crush

plantation - crushing

PKO

CPO

Food industry

non food oleochemicals

agrifood

bulk stations

agri / primary production oil extraction refining processing retail

smallholder

farmer groups

plantations

Indepent crush

plantation - crushing

PKO

CPO

Food industry

non food oleochemicals

agrifood

bulk stations

agri / primary production oil extraction refining

trade middle men food & nonfood

processing

large companies oleo chemical company

retail

stages

smallholder

farmer groups

plantations

Indepent crush

plantation - crushing

PKO

CPO

Food industry

non food oleochemicals

agrifood

bulk stations

agri / primary production oil extraction refining processing retail

Primary production Oil extraction

Independent

mill

Intermediaries

Plantation

mill

stages

smallholder

farmer groups

plantations

Indepent crush

plantation - crushing

PKO

CPO

Food industry

non food oleochemicals

agrifood

bulk stations

agri / primary production oil extraction refining processing retail

stages

smallholder

farmer groups

plantations

Indepent crush

plantation - crushing

PKO

CPO

Food industry

non food oleochemicals

agrifood

bulk stations

agri / primary production oil extraction refining processing retail

stages

smallholder

farmer groups

plantations

Indepent crush

plantation - crushing

PKO

CPO

Food industry

non food oleochemicals

agrifood

bulk stations

agri / primary production oil extraction refining processing retail

stages

smallholder

farmer groups

plantations

Indepent crush

plantation - crushing

PKO

CPO

Food industry

non food oleochemicals

agrifood

bulk stations

agri / primary production oil extraction refining processing retail

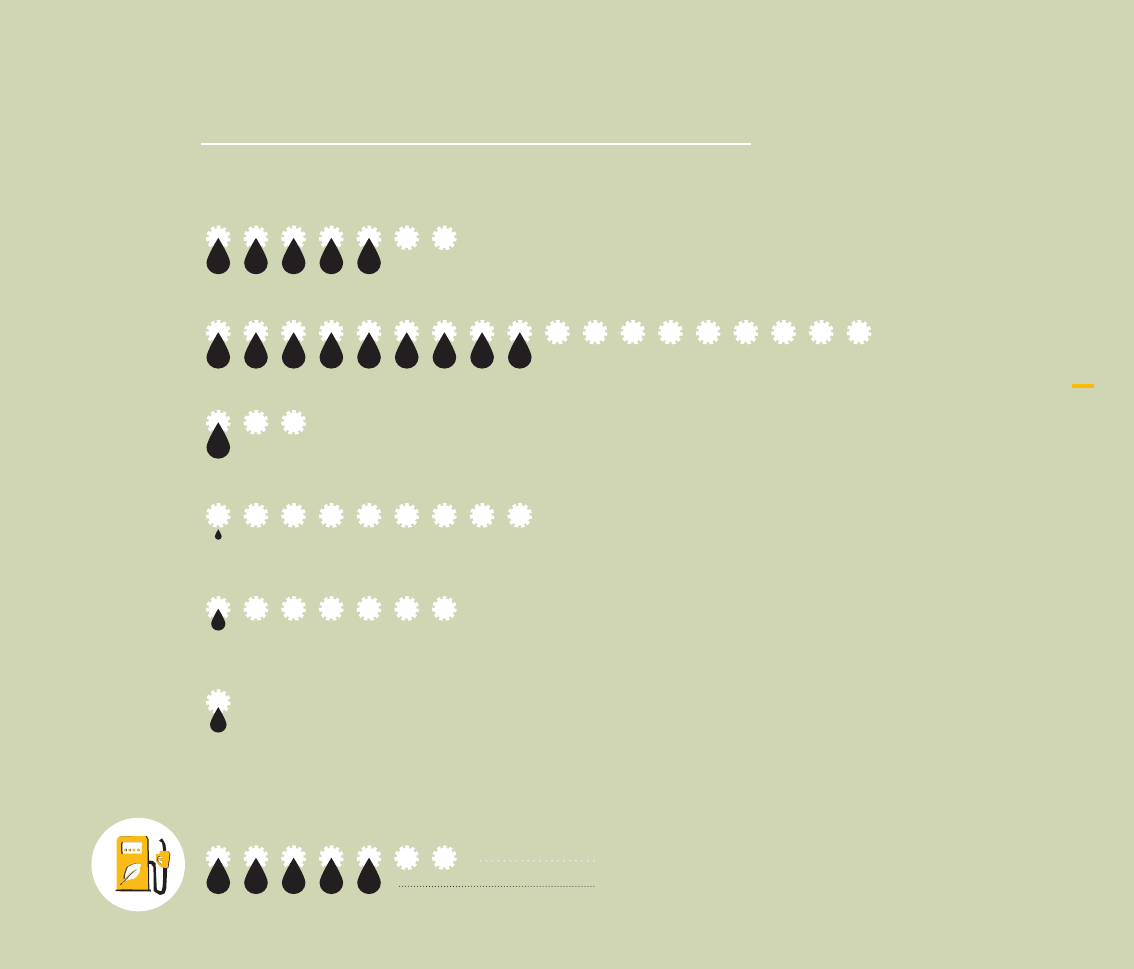

Independent

smallholders

Large

plantations

Scheme

smallholders

Largest

plantations

Sime Darby

FGV Holdings

Golden Agri-Resources

Astra Agro Lestari

Bumitama

Kuala Lumpur Kepong

˜

70%

˜

20%

˜

10%

THE PALM OIL SUPPLY CHAIN

stages

smallholder

farmer groups

plantations

Indepent crush

plantation - crushing

PKO

CPO

Food industry

non food oleochemicals

agrifood

bulk stations

agri / primary production oil extraction refining processing retail

stages

smallholder

farmer groups

plantations

Indepent crush

plantation - crushing

PKO

CPO

Food industry

non food oleochemicals

agrifood

bulk stations

agri / primary production oil extraction refining processing retail

stages

smallholder

farmer groups

plantations

Indepent crush

plantation - crushing

PKO

CPO

Food industry

non food oleochemicals

agrifood

bulk stations

agri / primary production oil extraction refining processing retail

smallholder

farmer groups

plantations

Indepent crush

plantation - crushing

PKO

CPO

Food industry

non food oleochemicals

agrifood

bulk stations

agri / primary production oil extraction refining

trade middle men food & nonfood

processing

large companies oleo chemical company

retail

Refining/processing/

trade

Product manufacturing Retail

Consumption

stages

smallholder

farmer groups

plantations

Indepent crush

plantation - crushing

PKO

CPO

Food industry

non food oleochemicals

agrifood

bulk stations

agri / primary production oil extraction refining processing retail

stages

smallholder

farmer groups

plantations

Indepent crush

plantation - crushing

PKO

CPO

Food industry

non food oleochemicals

agrifood

bulk stations

agri / primary production oil extraction refining processing retail

stages

smallholder

farmer groups

plantations

Indepent crush

plantation - crushing

PKO

CPO

Food industry

non food oleochemicals

agrifood

bulk stations

agri / primary production oil extraction refining processing retail

stages

smallholder

farmer groups

plantations

Indepent crush

plantation - crushing

PKO

CPO

Food industry

non food oleochemicals

agrifood

bulk stations

agri / primary production oil extraction refining processing retail

stages

smallholder

farmer groups

plantations

Indepent crush

plantation - crushing

PKO

CPO

Food industry

non food oleochemicals

agrifood

bulk stations

agri / primary production oil extraction refining processing retail

˜

23%

˜

77%

Refineries

Trade

Bulk station/blenders

Biofuel

Non-food,

Food industry

and animal feed

smallholder

farmer groups

plantations

Indepent crush

plantation - crushing

PKO

CPO

Food industry

non food oleochemicals

agrifood

bulk stations

agri / primary production oil extraction refining

trade middle men food & nonfood

processing

large companies oleo chemical company

retail

Largest

refineries

Wilmar International

Musim Mas

Golden Agri-Resources

Royal Golden Eagle

Mewah International

Cargill

Largest

oleochemical companies

AAK

BASF

Clariant

Dupont

Evonik

Johnson&Johnson

Largest

FMCG companies

Unilever

Mondelez

Nestle

Ferrero

PepsiCo

Procter&Gamble

Largest

Grocery Retailers

Walmart

Schwarz Group

Kroger

Aldi

Costco

Carrefour

PREFACE — 3

Context — 5

INTRODUCTION — 5

SMALLHOLDER INCLUSIVENESS — 5

ABOUT THIS REPORT — 6

Market dynamics — 9

INTRODUCTION — 9

PRODUCTION — 9

TRADE — 12

CONSUMPTION — 13

Smallholder farmers — 17

INTRODUCTION — 17

OIL PALM SMALLHOLDERS — 17

ASIA — 18

LATIN AMERICA — 20

WEST AFRICA — 21

PROFITABILITY AND INCOME — 22

FAIR VALUE DISTRIBUTION — 25

Smallholder inclusivity — 29

INTRODUCTION — 29

CORPORATE TRANSPARENCY — 30

VOLUNTARY COMMITMENTS — 31

CERTIFIED SUSTAINABLE PALM OIL — 31

MULTI-STAKEHOLDER INITIATIVES — 31

MANDATORY REGULATIONS — 34

ACCOUNTABILITY — 36

Conclusion — 39

RECOMMENDATIONS — 41

SOURCES OF FIGURES — 44

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS — 45

REFERENCES — 46

ENDNOTES — 54

COLOPHON — 56

Contents

Preface

At Solidaridad we envision a world in which all we produce and consume can sustain us,

while respecting the planet, each other and the next generations. The palm oil sector is

perfectly placed to deliver on this vision. The oil palm is a high-yielding crop grown by

millions of smallholder farmers in many countries across the tropics and, under the right

conditions, this crop can generate a living income while the farmers work in balance with

nature. However, all too often the conditions are not right. Smallholder voices are rarely

heard. They don’t feel ownership over their own futures. They receive too little in return for

their hard work, and are forced to take unfair financial risks. All these factors put limitations

on how great a force for positive change oil palm can be.

This report is written with the input of smallholder representatives from Asia, Africa and

Latin America. Through the experiences they share it becomes clear that market dynamics

have led to unfavorable prices and incomes for oil palm smallholders. While they struggle,

food and consumer goods manufacturers and retailers reap the profits in the supply chain.

In addition, we find that governments in consuming and producing countries do not fully

support smallholders to farm in the most sustainable way.

This first global Palm Oil Barometer opens the floor to all stakeholders. How can we reach a

fair value distribution if farmers’ voices are not heard? How do we ensure oil palm small-

holders are included in the global market? This report sets the stage for a lively discussion

that we hope contributes to feasible solutions that work for the smallholders who feed the

world.

Jeroen Douglas,

Executive Director of Solidaridad Network

This report is supported and co-signed by the following smallholders representatives:

Dr. Richard Mani Banda, President, Dayak Oil Palm Planters Association (DOPPA), Malaysia

Douglas Alau Tayan, Secretary General, Dayak National Congress (DNC), Malaysia

Firmus Valentinus, CEO, Keling Kumang Credit Union (CUKK), Indonesia

Dr. M. Edwin Syahputra Lubis, Head, Indonesian Oil Palm Research Institute (IOPRI), Indonesia

Mansuetus Darto, National General Secretary, Serikat Petani Kelapa Sawit (SPKS), Indonesia

Dr. Rino Afrino, Secretary General, Asosiasi Petani Kelapa Sawit Indonesia (APKASINDO), Indonesia

José Edas Mejía Betancourth, President of Board of Directors, National Federation of Palm Oil Smallholders

(FENAPALMAH), Honduras

Milton Alexis Hernandez Godoy, Agriculture Manager, Hondupalma-Paiguay Smallholders Association, Honduras

Jose Pascual Coello Castillo, Member of Board of Directors, Zitihuatl Cooperative, Mexico

Samuel Avaala Awonnea, President, Oil Palm Development Association of Ghana (OPDAG), Ghana

And experts:

Dr. Margaret Chan Kit Yok, Associate Professor, University Teknologi MARA, Malaysia

Jorge Cabra, Consultant, Expertagro SAS, Colombia

Rodolfo Guzmán, Freelance Consultant, Guatemala

Dr. Ir. Maja Slingerland, Associate Professor Plant Production Systems Group, Wageningen University and Research,

The Netherlands

INTRODUCTION

The prevailing image of palm oil today in Europe is that of a crop that devastates the earth,

transforming much of the world’s tropical forests into cookies, cosmetics and car fuel. Palm

oil figures prominently in the press as the crisis surrounding deforestation, biodiversity loss

and climate change builds. Often it illustrates a myriad of deeply divisive subjects, includ-

ing economic development, human rights, and environmental conservation (Meijaard and

Sheil, 2019; Qaim et al., 2020). Although the image of industrial scale companies operating

oil palms as a monoculture plantation crop holds true, a diverse base of more than three

million smallholders produce roughly 30 percent of global palm oil. The contribution of

smallholders in the overall supply of palm oil is expected to increase among others because

of the implementation of zero-deforestation commitments by the private sector. Govern-

mental moratoriums on large-scale oil palm plantation expansion are leading to increased

scrutiny on the growth of bigger estates (CIFOR, 2017).

For millions of smallholder families oil palm contributes to household wellbeing, food

security and rural livelihoods. Because it can be harvested year-round, it provides a steady

cash flow and is often regarded as the one crop that can help a family out of poverty within

a generation (Ayompe et al., 2021).As such, rural poverty alleviation, food security and eco-

nomic development are important arguments of government ministries, industry lobbies,

and companies to motivate the expansion of the oil palm sector.

However, the social and

environmental concernsof palm oil production include land conflicts, the loss of traditional

livelihoods and culture, large scale deforestation, decreasing biodiversity and intensified

carbon dioxide emissions from peatlands (Dauvergne, 2018; Qaim et al., 2020). By isolating

the environmental crisis from the much wider poverty crisis to which it is directly linked, it

is easy to overlook the smallholders’ challenges in growing oil palms sustainably (Azhar et

al., 2017).

SMALLHOLDER INCLUSIVENESS

The sector’s sustainability agenda tends to focus on large industrial plantations, maintaining

that voluntary sustainability standards and zero deforestation commitments are effective

ways to improve the sector’s governance (Grabs et al., 2021; Ten Kate et al., 2020). The main

private sector players also have their own measures in place; defining their own sourcing

criteria, making use of traceability systems or working directly with their suppliers, for

Context

example. Contributing specifically to the resilience of smallholder farmers is part of their

‘inclusive’ business approach and sustainability commitments. Through technical assistance

programmes these smallholders are integrated into the value chain and vertically linked

to large buyers.For farmers and their organisations, inclusion promises to bring higher

incomes, improved access to finance and services, and more equitable distribution of ben-

efits in the supply chain. Inclusion is also expected to have positive effects in environmental

sustainability, for example by promoting biodiversity conservation.

In reality, most ‘inclusive business’ schemes benefit a narrow minority of farmers who have

better access to capital, are more educated, closer to infrastructure, and strongly oriented

toward commercial agriculture (FIL, 2022; Ros-Tonen et al., 2019). In terms of actions to

support rural livelihoods and basic ecosystem services, this approach faces implementation

barriers. The underlying focus on continuous growth of production misses the point that

small farms cannot be thought of as large farms on a smaller scale. Small producers have

different needs, preferences and constraints, and their marginalization means that these

unique characteristics are often overlooked. Smallholders are unlikely to have the capacity to

meet demand for sustainable and deforestation-free palm oil production without consistent

support and incentives from procuring companies or governments (Saadun et al., 2018).

In general, smallholder engagement is a lengthy process that requires investment, planning

and long-term involvement of all stakeholders. While there are opportunities for small-scale

farmers to gain real benefits from sustainable oil palm production, the large number of het-

erogeneous farmers means that achieving this potential requires specific policy approaches

and financial support structures. There is the risk that poorly designed ‘inclusive’ business

activities and sustainable procurement policies will exclude many smallholder farmers by

default. For example, after two decades of Certified Sustainable Palm Oil (CSPO), only

70,000 hectares or 1.5 percent of Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) certified

land belongs to independent farmers who make their own management decisions (RSPO,

2022a). The EU proposal for a regulation to reduce deforestation embedded in tropical

products like palm oil, soy and beef, might hinder smallholder market access without ap-

propriate accompanying measures (Solidaridad, 2021). To complicate it further, the market

demand of sustainable palm oil in consuming countries is hindered by its invisibility as an

embedded ingredient in most products. Companies rarely communicate with consumers

about ethical sourcing, sustainability and certification to give them the assurance that they

use sustainable palm oil ingredients in the production process.

ABOUT THIS REPORT

This first edition of the Palm Oil Barometer explores the local, national and global dimen-

sions of the palm oil production system. It brings particular concerns to the surface around

the position of small-scale farming, highlighting the opportunities and challenges that the

development of sustainable palm oil chains presents to smallholders. In view of the chal-

lenges, we will examine the sector’s strategies for change, and individual and collective

efforts to create a truly smallholder-inclusive sector.

First, this report gives an overview of the palm oil market, where consumption and there-

fore demand is expected to increase. Against this backdrop we examine the role and posi-

tion of smallholders in the production of palm oil, by observing how the socioeconomic and

environmental aspects are intertwined in the main producing countries.

Second, the report questions the effectiveness of conventional sustainability interven-

tions aiming at upgrading smallholders into modern export markets. The narrow focus of

projects tends to overlook the diversity of smallholder livelihoods and denies the complex

tangle of economic, social and political factors. Price premiums, market access, and offers

of technical assistance are typically cited as incentives for producers to improve their

practices. However, the limited scope of these strategies appears unable to drive systemic

changes that are truly sustainable, inclusive and impactful at producer level, especially in the

demanding environment of unorganized smallholders in Africa, Asia and Latin America (see

box 2).Price volatility is another constraint, making it difficult to plan financially, which can

have big implications on monthly cash-flow streams (see figure 1). For example, despite the

considerable profit margins of embedded palm oil in consumer products, most smallholders

consider palm oil prices too low to make ends meet.

2

Finally, the report looks at the growing support for non-competitive sector collaboration,

blending public and private investments to address fundamental sustainability challenges at

an impactful scale. Several multi-stakeholder initiatives (MSIs) address the complex sustain-

ability challenges in the sector. These MSIs involve a wide range of stakeholders, including

NGOs, retailers, traders, processors and governments from consuming as well producing

countries. Such broad stakeholder initiatives come in many forms and formats, like the

Accountability Framework Initiative (AFI), the Palm Oil Collaboration Group (POCG) or

the RSPO. A better understanding of how smallholders’ interests are currently represent-

ed might help to go beyond top-down approaches and place oil palm smallholders at the

centre of strategies for change.

500

1000

1500

2000

2500

2022

2021

2020

2019

2018

2017

2016

2015

2014

2013

2012

2011

Palm kernel oil

Palm oil

FIGURE PALM OIL PRICE AND PALM OIL KERNEL PRICE MEDIO

(US$/mt)

500

1000

1500

2000

2500

2022

2021

2020

2019

2018

2017

2016

2015

2014

2013

2012

2011

Palm kernel oil

Palm oil

“ To succeed in the global fight

against the climate and biodiversity

crises we must take the responsibility

to act at home as well as abroad.

Our deforestation regulation

answers citizens’ calls to minimize

the European contribution to

deforestation and promote

sustainable consumption.”

Frans Timmermans,

Executive Vice-President for the European Green Deal.

European Commission (2021 November 17).

Market dynamics

INTRODUCTION

In the last two decades, oil palm expansion has taken place through different agribusiness

models, with a preference for medium and large-scale, monocrop plantations, which are

either state owned or private (Byerlee et al., 2017). These commercial plantations, that can

extend over tens of thousands of hectares, tend to be part of large ventures often owned

by multinational companies. The continuous expansion of large oil palm plantations has

received much attention as the public face of palm oil production. A recent example is the

controversial oil palm plantation project Tanah Merah in Papua, Indonesia. On the island

280,000 hectares of highly biodiverse rainforest is designated for conversion to palm oil

production plantations and infrastructure. The pieces are all in place to predict several det-

rimental effects, including displacement of indigenous people, deforestation and destruc-

tion of a global biodiversity hotspot (Earthsight, 2018; Gecko project and Mongabay, 2019).

Clearly, continuing with this business-as-usual approach to satisfy demand for palm oil is a

far cry from promoting development with optimal social and ecological results.

In this context, it’s important to realize that approximately three million oil palm smallhold-

ers produce fresh fruit bunches (FFB) that are processed into around a quarter to one third

of the total palm oil supply.

3

A widespread expectation is that, through market inclusion,

small producers can contribute to meeting the global demand for sustainable edible oils.

With the right incentives and support, smallholders can even prosper in the face of the

palm oil sector’s major challenges. To better understand their current and future position

we will look at the sector’s specific market dynamics in global production, consumption and

the drive for sustainability.

PRODUCTION

Palm oil is a vegetable oil that is extracted from the fruit of the oil palm, a perennial tree

crop. The palm bears fruit bunches that can be harvested year-round over a tree’s life

span of 25 years. Oil palm grows best in the lowland humid tropics of Asia, Africa and the

Americas and plantations range from small farming plots of a few hectares to agro-industri-

al estates that cover tens of thousands of hectares. An assessment of 2019/20 satellite data

has resulted in a detailed global oil palm map, which reveals a division between 73 percent

industrial and 27 percent smallholder plantations in terms of area (Descals et al., 2021).

4

Plantations are found in 49 countries and the total land dedicated to the crop covers an

INDIA

PAKISTAN CHINA

EU

6.850

THAILAND

MALAYSIA

USA

Import

Export

Own use

Unit = 1.000 MT

COLOMBIA

GUATEMALA HONDURAS

NIGERIA

PAPUA NEW GUINEA

INDONESIA

8.600

7.2003.550

300

685

17.220

3.370

2.427

584

1.200

810 600

1.625

550

1.765

15.445

29.500

FIGURE GLOBAL PRODUCTION AND CONSUMPTION 2021 (EXPORT/IMPORT/USE)

INDIA

PAKISTAN CHINA

EU

6.850

THAILAND

MALAYSIA

USA

Import

Export

Own use

Unit = 1.000 MT

COLOMBIA

GUATEMALA HONDURAS

NIGERIA

PAPUA NEW GUINEA

INDONESIA

8.600

7.2003.550

300

685

17.220

3.370

2.427

584

1.200

810 600

1.625

550

1.765

15.445

29.500

area of nearly 21 million hectares (Mha). The actual area under oil palm production could be

10–20 percent greater than the area detected from satellite imagery, because young planta-

tions (less than approximately three years old), open-canopy plantations or mixed-species

agroforests may have been omitted.

With 19 Mha, Southeast Asia has the largest area under

production, followed by South and Central America (1.4 Mha), Central and West Africa (1.0

Mha) the Pacific (0.14 Mha). The region with the highest percentage of smallholder oil palm

is West Africa with almost 70 percent of total plantings.

In 2021, Indonesia and Malaysia accounted for over 64 million of the 76.5 million metric

tonnes of global palm oil production (USDA FAS, 2021). When considering all production

regions, Southeast Asia represents 84 percent of total production, Africa is responsible for

four percent and Latin America for eight percent of the volume. In just 20 years production

has tripled. Global demand is on track to push production to 80 million metric tons by 2026,

compared to an annual average of 73,500 million metric tons produced between 2017-2021

(USDA FAS, 2021).

TRADE

In the movement from harvest to consumption, the oil palm’s fresh fruit bunches (FFBs)

are milled to derive the crude palm oil and further refined to producevegetable oil. This

needs to be done quickly, usually within 48 hours of harvest, as otherwise the fruit begins to

deteriorate and free fatty acids build up (Philips et al., 2022). Often there is an intermediary

or trader who organizes the transport, delivery orders, the contractual arrangement and

payments between the smallholder and the mill.

In Indonesia and African countries, smallholder access to mills is often hindered by poor

road infrastructure and/or long waiting lines at the mills. The price smallholders receive for

their FFBs depends on access to the mills and fair-trading practices (see paragraph 3.3).

At the palm oil mill, the FFBs undergo a threshing process, separating the fruits from the

bunch. The fruit has a unique feature: it contains two oils of strikingly different composition.

Both the flesh (known as mesocarp: 90 percent of the total oil) and the kernel can produce

oil. Crude palm oil (CPO) is a deep orange-red, semi-solid fluid, while palm kernel oil (PKO)

is a white-yellow oil extracted from the kernel (Murphy et al., 2021).

In Asia, the CPO and PKO oils are then transported by truck and boat to refineries, while

in Africa substantial volumes are used for artisanal processing and consumption without

refining (Rafflegeau et al., 2018). The refinery processes crude palm oil into household cook-

ing oil and other refined ingredients for clients in the food, industrial and fuel industries.

Refineries often source CPO from many different mills. For example, nearly 250 palm oil

mills and many smaller refineries supply the Wilmar refinery in Pelintung, Indonesia. It also

acts as a bulking station – a storage facility gathering truckloads of crude palm oil for bulk

transportation to its next stop on the supply chain (Philips et al., 2022). The industry leaders

include Wilmar International, Musim Mas, Mewah Group and Sime Darby. Many are vertically

integrated (from plantations to refinery) and own a large part of the processing and storing

facilities in most oil palm producing countries. They also engage in plantation manage-

ment, outgrower schemes, export and import of CPO, logistics, storage, risk management

and finance (Pirard et al., 2020; Rijk et al., 2021). Wilmar International, for instance, already

represents the handling of 40 percent of the global CPO trade. This volume is equivalent to

almost all palm oil production outside of Indonesia in 2021.

CONSUMPTION

About 75 percent of refined CPO is processed in the food industry. Palm oil-based products

might be used in the form of cooking oil, but often palm oil is embedded as an ingredient

in other products like margarine, chocolate, cookies and ice cream. Approximately half of

packaged food and personal hygiene products in a typical supermarket now contain palm

oil. Palm oil and its derivatives are also processed in non-food ingredients for the home

and personal care industry (for example, cosmetics, soaps and detergents) and industrial

inputs (oleochemicals, pharmaceutical) industry. Palm kernel oil is mainly used in the home

and personal care industry, and the palm kernel meal is absorbed in animal feed (Rijk et al.,

2021).

One growing use for palm oil is in the bioenergy market, where edible oils like palm oil and

its by-products are used as an alternative to fossil fuels. In 2020, 23 percent (17.5 million

MT) of the global production of palm oil was used in biodiesel – see figure 3 for a country

specific overview. Between 2021 and 2023 the EU has capped palm oil for transport fuel at

69% = 5.7 million MT (2020)

47.8% = 8.81 million MT (2021)

29% = 0.97 million MT (2021)

1.7% = 0.153 million MT (2021)

6.9% = 0.479 million MT (2021)

70% = 0.6 million MT (2020)

PALM OIL CONSUMPTION

% USED FOR BIOENERGY

EU

Indonesia

Malaysia

India

China

Colombia

FIGURE GLOBAL PALM OIL CONSUMPTION FOR BIOENERGY

Unit = 1,000 MT

the 2019 level per member state and is phasing out its use by 2030 over concerns that the

production contributes to global carbon emissions, exacerbating climate change (EC, 2019).

Several EU member states have set their own reduction trajectories that decrease palm oil

use sooner than the EU requires. Meanwhile, the demand for biofuels is growing in other

markets. Two other major export markets for biodiesel are China and India, while in Indone-

sia biofuels alone account for almost half of all domestic palm oil consumption (Rijk et al.,

2021).Biofuel usage targets promote the demand for palm oil and hence positively influence

palm oil prices.

5

For example, Indonesia has high biofuel usage targets to maximize domestic

use of palm oil and cut imports of oil. Its targets are 30 percent by 2020 and 40 percent by

2030 (CDP, 2021).

Palm oil demand will continue to grow particularly in Asia, partly because it’s cheaper than

other vegetable oils and is promoted as being healthier. The projection of global palm oil

demand shows an estimated growth between 0.8 and 2.8 percent a year (USDA FAS, 2022;

Worldbank, 2022). To meet the demand in the minimal scenario of 0.8 percent growth,

production has to rise to more than 94 million MT in 2030.

6

However, the expansion of oil

palm faces many challenges (Pirker et al., 2016). For instance, labor shortage has become a

structural issue, and large-scale renovation (replanting) is crucial to increase and maintain

productivity levels. In combination with zero deforestation commitments and governmental

moratoriums on large-scale plantations expansion the widespread expectation is that small-

holder farmers will play a growing role, not only to meet the global demand of palm oil, but

also as stewards of natural resources and biodiversity.

Calls for corporate responsibility and strict environmental policies have led to several public

and private efforts, in both consumer and producer countries. To improve the governance

of palm oil production various standards and policies have been developed, such as the

global RSPO. At national level there are sustainability standards too, like the Indonesian

Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO) standard, the Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil (MSPO) scheme,

the Indian Palm Oil Sustainability Framework (IPOS), and Sustainable Palm Oil (APSCO)

Colombia. Although these standards and certified sustainable palm oil have an important

role when it comes to working towards a more sustainable and inclusive palm oil supply

chain, there are legitimate critiques on the scope, effectiveness and enforcement of certifi-

cation standards and the scale of individual private sector initiatives (see chapter 4).

The demand for sustainable palm oil mainly comes from western markets, with Europe be-

ing the largest market for certified sustainable palm oil. Currently, this demand is met by the

production volumes of certified plantations. It is difficult for independent smallholders to

become certified. Direct benefits, like sustainable price premiums or access to new markets,

are limited by the extent to which international markets absorb the total volume of certified

palm oil. For instance, Europe represents only nine percent of the global palm oil market

(USDA FAS, 2022), of which 70 percent is used for bioenergy, which will be phased out by

2030 (IDH and EPOA, 2021). The major importing regions, collectively responsible for about

half of total palm oil imports, are the Indian subcontinent (India, Pakistan, Bangladesh) with

about 13.5 Mt, China with 7.1 Mt and the EU with 6.8 Mt (USDA FAS, 2021). So far these mar-

kets do not set sustainability requirements for the volumes they import.

In Europe and the USA the sector has become almost synonymous with deforestation

and biodiversity loss (Meijaard and Sheil, 2019). Consumer campaigns led by NGOs like

Friends of the Earth, Greenpeace and Global Witness have raised public awareness about

the negative impacts of oil palm production.

7

Consumer sentiment in western markets has

been turning against palm oil. This has led some retailers, manufacturers and consumers to

boycott palm oil. For example, the UK supermarket chain Iceland tried to eliminate palm oil

from its private label products or the Dutch margarine of Flower Farm branding its pro-

ducts palm oil-free (Southey, 2020).

Despite this, many academics and conservation organizations agree that banning palm oil

would simply shift the problem elsewhere, threatening other habitats and species. Instead

of a boycott, solutions for palm oil include the development of better governance and land

use planning, enforcement of labor laws, price remuneration for sustainable palm oil and

appropriate consumer communication.

“ Our lives improved a lot when

we started cultivating oil palm. My

daughter had the opportunity to

study in a private university,

I built my house, I’m much more

comfortable, and we have basic

utilities like water, drainage, even

cable – none of this would have been

possible if it weren’t for oil palm.”

Ana Villasis, a smallholder from

the Ucayali region, Peru, 2022.

Smallholder

farmers

INTRODUCTION

Meeting the growing demand for palm oil, while adhering to new zero deforestation

commitments

and the overall need to be more sustainable, will require a combination of

approaches, including increasing yields in existing production areas. Minimizing negative

outcomes of oil palm farming requires sustainable production methods that focus on

ecologically and socially sustainable development (Cadman et al., 2019; Meijaard et al. 2020).

In view of threats including climate change, poverty migration and food insecurity, it is par-

amount to support integrative approaches to rural development that put local people and

nature at the centre.

Hence, a good starting point would be to focus attention on the lands managed by small-

holders, to support poverty alleviation, food and nutrition security, resilience and livelihood

security. There are excellent examples of well-organized smallholders who produce compet-

itive yields in line with stringent sustainability standards. The higher the quality of the FFB,

the greater the quantity of crude oil that can be extracted from it. Improving the yield from

FFB is thus crucial for smallholders in getting a better income (Murphy et al., 2021).

Another income challenge smallholders face, although it varies from country to country,

is that most of them are poorly connected with market information and each other. This

makes it difficult for them to successfully compete with other actors in the value chain.

They often lack the time and the money to invest in improved practices to meet social and

environmental standards, which in addition may not be clearly communicated to them

(Grabs et al., 2021). Irrespective of the optimal strategy, replanting with high-yielding palms

or implementing land-sharing agroforestry techniques are challenging for smallholders

since they may not be able to access the improved plant varieties required to increase

yields (Khasanah et al., 2020; Khatun et al., 2020; Purwanto et al., 2020). In such situations,

provision of technical support from government agencies, companies and NGOs may help

smallholders choose intensification over clearing more land to increase the acreage of oil

palms.

OIL PALM SMALLHOLDERS

Smallholders are part of the global palm oil supply chain in a variety of ways, with signifi-

cant differences between countries. As global data on the number and size of smallholder

oil palm farms is not conclusive, it’s estimated that some three million smallholders are

involved in palm oil production worldwide and their numbers are increasing (Jezeer and Pa-

siecznik, 2019). There is great divergence between what is considered a small holding from

country to country. Oil palm smallholders follow a wide range of land use strategies and

models of social organization. Commonly, families operate as independent units and pursue

their own livelihood strategy with a combination of different production activities to gener-

ate household income (Jezeer and Pasiecznik, 2019). A typical oil palm land size is below five

hectares, despite the fact that the threshold for smallholder farmers is set at 25 hectares in

Indonesia and at 40 hectares in Malaysia (Pramudya et al., 2022; Mohd et al., 2021).

According to the most up-to-date scientific research (Descals et al., 2021), smallholder

farmers account for an estimated 27 percent of the total cultivated land area and between

25 and 30 percent of global production.

8

Large plantations often integrate smallholders

through outgrower schemes or rental agreements. These so-called scheme smallholders are

specialized in oil palm farming and rely on the plantation company for improved planting

stock, fertilization and training. The livelihood basis for the vast majority of independent

smallholders is diversified agricultural production, where the linkages between forest, farm

and land support human well-being and a range of ecosystem services (Jezeer et al., 2019).

These smallholders are developing their operations independently from the estates. They

organize themselves in farmer groups, in cooperatives and associations, to collect and sell

their FFBs to the mill that offers the best price. Or they depend on intermediaries for selling

their produce as well as for access to inputs and credit.

BOX SMALLHOLDER DEFINITION

The term oil palm smallholders or farmers often lacks a precise definition, but in

practice tends to refer to differences in size and level of reliance on family labor. The

farm provides the majority of income to the family, and in turn the family provides the

majority of labor on their farm (Jelsma, 2017).

9

This aligns with the RSPO’s definition:

Smallholders are those managing palm oil plantations of 50 hectares or less. They can

operate either independently or in collaboration with companies. In this definition, the

RSPO distinguishes two types of smallholders: scheme smallholders and independent

smallholders.

Scheme smallholders: do not have enforceable decision-making power on how they

operate their land and their production practices, and/or freedom to choose how they

use their land, the types of crops to plant, and how to manage them.

Independent smallholders: all other smallholders not classified as scheme smallhold-

ers. They have the freedom to choose how they use and manage their land including

the types of crops to plant.

Asia

The primary regions for oil palm farming in Indonesia are Sumatra and Kalimantan. The ma-

jority of smallholders are located in Sumatra, where the oil palm sector is well established

and plantations are mature. There are fewer smallholders in Kalimantan where industrial

plantations tend to dominate. In these areas, smallholders develop the lands in the gaps be-

tween larger oil palm concessions (Descals et al., 2021). Although the statistics detailing the

number of smallholders is limited, it’s estimated that there are 1.46 million smallholders en-

gaged in the Indonesian oil palm sector, controlling about 4.3 million hectares. About 25 per-

cent of these smallholders are tied to companies through different partnership schemes,

while 75 percent are independent, managing more than 3.1 million hectares (Rijk et al., 2021).

Unfortunately, the number of the smallholders who are members of functioning coopera-

tives remains unknown, as is the number of medium-scale landholders in production zones

(Pacheco, 2017). Despite the lack of reliable data, the Palm Oil Agribusiness Strategic Policy

Initiative (PAPSI) predicts that the area of Indonesian smallholder plantations will continue

to increase and account for around 60 percent of Indonesia’s oil palm plantation area by

2030 (Suhada et al., 2018). This is mainly because Asia will need much more vegetable oil

than present and large-scale plantations have already reached optimal productivity. The

level of scrutiny is huge (with or without any moratorium) for them to expand into forests.

In this scenario, growth is then automatically expected to come from smallholders (Gaveau

et al., 2022).

The palm oil industries of Southeast Asia are interconnected. Up until April 2020 as many

as 337,000 migrant workers (80 percent from Indonesia) worked on Malaysian plantations.

Thousands of them went home during the Covid-19 pandemic, with a steep drop in pro-

duction of palm oil. As a result, the oil palm yields dropped. Plantation owners are finding

it harder and more expensive to hire workers, leaving plantations well below full capacity

in the 2022 harvest season (Chu, 2022). Meanwhile, Malaysian and Singaporean companies,

either via direct investments or joint ventures with local companies, control more than two-

thirds of the total production of Indonesia’s palm oil (Pacheco, 2017).

While in Malaysia the peninsula is the historic centre, considerable oil palm expansion has

occurred in Sabah and Sarawak (Murphy et al., 2021). In the Malaysian model, the palm oil

sector is dominated by a dozen large conglomerates that are often vertically integrated and

operate plantations, mills and trade, down to the processing plants in consumer markets

like Europe, China and India. The mills have contracts with smallholders who are seen as

out-growers, and are managed through a range of contractual structures mediated by

government agencies or companies. Large-scale plantations owned by private companies

have a share of 61 percent, while 22 percent are under government schemes, half of which

belong to out-grower smallholders, and 17 percent owned by independent smallholders

(Mohd Hanafiah et al., 2021). There are roughly 300,000 smallholders (farmers who own

40 hectares of land or less), and of this group 260,350 are independent (Rahman, 2020). In

new oil palm zones and forest frontiers, the scheme smallholder model tends to dominate.

Under this model, the company obtains rights to develop the plantation on local communi-

ty lands, clears the area and develops the plantation. A major portion of these plantations

(80 percent) is often owned by the company while 20 percent is planted for smallholders

(Pacheco, 2017).

Thailand is the third largest producer of palm oil. Small farmers owning less than 8 hectares

comprise more than 90 percent of the one million planted hectares in southern Thailand.

Most of the production comes from 120,000 smallholders, while an additional 180,000

smallholders and their families support their household income with oil palm (EFECA,

2020). Most of the palm oil production in Thailand is used in domestic consumption and

biodiesel, with limited volumes for the export market.

In Papua New Guinea, oil palm is a very important export crop. This crop earned about 56

percent of the country’s total value of agricultural exports in 2020. By 2030, the Papua New

Guinea government aims to have 1.5 million hectares under oil palm cultivation, compared

to about 150,000 hectares in 2016 – this implies a ten-fold increase. Large areas of rainfor-

est are currently under concession by palm oil and pulpwood companies, contributing to

large scale deforestation and conflicts with indigenous communities. In terms of rural em-

ployment, this industry creates livelihoods for about 23,000 smallholders. Notably, oil palm

smallholders do not have ownership rights on the lands they operate. This tenurial right is

consistent with the country’s dominant land tenure system, popularly known as customary

land (Eliha and Michael, 2017).

Latin America

The Latin American region’s global market share has been gradually increasing. With a total

output of 4.6 million MT in 2020/21, this region is second to Asia in global palm oil provi-

sion. It has nearly doubled its oil palm area in the last decade, making it the fastest growing

producing region in the world (Furumo and Aide, 2017). The Latin American region con-

sumes on average 75 percent of its own palm oil production, with Europe being the most

important export market. Particularly in South America, palm oil production has often been

promoted by government subsidy programmes and development agencies to substitute

illicit crops in the region (Quiroz et al., 2021).

Oil palm expansion across the region shares two characteristics. First, large corporate

plantations play a significant role in palm oil production. And second, landless rural inhabi-

tants provide labor for oil palm farming. These workers include migrants from neighboring

regions, as in the case of Guatemala or Brazil or from neighboring countries, as in the case

of Guatemalan laborers in southern Mexico or Colombian workers in northern Ecuador

(Castellanos-Navarette et al., 2019).

Smallholders in Latin America, though fewer than in Asia, play an important role in the pro-

duction of palm oil, especially in Colombia, Ecuador and Honduras (Lesage et al., 2021). In

MALAYSIA

COLOMBIAEQUADORGHANA

PAPUA NEW GUINEA

INDONESIA

CÔTE D’IVOIRETHAILAND

1,460,000

300,000

300,000

23,000

6,400 4,800

31,000

20,000

HONDURAS

16,000

FIGURE OIL PALM SMALLHOLDERS PER COUNTRY

Colombia 480,000 hectares of land is under oil palm cultivation, an increase of 75 percent

during the last ten years. More than 80 percent of the 6,000+ producers are smallhold-

ers and the sector has 140 associations in which small, medium and large producers are

integrated (FEDEPALMA, 2022). Together they produce almost 1.6 million MT of palm oil.

Colombia is projected to produce two million MT of palm oil by 2030, increasing by around

25 percent in relation to current levels, with palm oil-based biodiesel as an important and

growing market (Kuepper et al. 2021). Guatemala’s oil palm cultivated area is approximately

180,000 hectares, having increased by about 130 percent over the last ten years. Officially,

there are only 235 oil palm growers in the country. Smallholders account for 55 percent,

while one third are medium-sized producers and 12 percent are large producers. In con-

trast, in Ecuador oil palm is cultivated by some 6,600 producers, of whom 96 percent are

smallholders with fewer than 50 hectares. In 2020/21 the country produced 540,000 tons, a

decline of 15 percent over the last five years due to the impact of bud rot disease (Kuepper

et al. 2021). Honduras produced 600,000 MT of palm oil in 2020/21. Approximately half the

oil palm area is cultivated by 16,000 smallholders with land sizes between five and 25 hect-

ares (Lagunes-Espinoza et al., 2022; Solidaridad Central America, 2022).

West Africa

Oil palm is a perennial crop native to Africa and there are some industrial operations and

plantations that have been active there for a long time. However, only recently oil palm in-

dustries are expanding in many of West Africa’s tropical countries with Nigeria, Ghana, Côte

d’Ivoire and Cameroon as the main producers (Paterson, 2021). In most countries oil palm

crops are used for local consumption, with Côte d’Ivoire and Cameroon as the only major

palm oil exporters (Murphy et al., 2021). Smallholders manage a far greater total land area

than industrial plantation producers, cultivating anywhere between one and 50 hectares of

land.

The available data on the number and size of oil palm producing plots is not conclusive and

accurate data on the number of smallholder farmers is even harder to find. In Ghana, there

are more than 20,000 smallholder oil palm farmers. Independent smallholder farmers play a

MALAYSIA

COLOMBIAEQUADORGHANA

PAPUA NEW GUINEA

INDONESIA

CÔTE D’IVOIRETHAILAND

1,460,000

300,000

300,000

23,000

6,400 4,800

31,000

20,000

HONDURAS

16,000

significant role, accounting for about 60-80 percent of production (Khatun et al., 2020).

In Côte d’Ivoire there are 44,900 oil palm growers, of whom about 70 percent are small-

holders (Guero et al., 2021).

The expectation is that palm oil production will accelerate across Africa (Feintrenie et al.,

2016). However, due to current socio-cultural, technical, political and ecological constraints,

only around one-tenth of the potential 51 million hectares in the four main producing coun-

tries in tropical Africa are likely to be profitably developed in the near future. Although this

might change as technological, financial and governance conditions improve.

PROFITABILITY AND INCOME

Many smallholders are attracted to growing oil palms for its greater yield and potentially

higher prices, as well as the fact that it can be harvested year-round, providing a steady

cash flow. Compared to other commodities like cocoa, coffee or tea, oil palm is seen as a

profitable crop and price is rarely the subject of public debate. It’s likely that this is linked to

the fact that palm oil is generally more profitable and that, in most cases, smallholders have

larger plots than their peers in other crops.

Multiple factors can influence a farms’ profitability, including its size, exchange rates, labor

costs, market access, fertilizer costs, or lack of access to capital and insurance.In addi-

tion, farmers’ revenue depends on the quantities they sell, the prices they receive and the

production costs. To receive a fair price for their FFBs, smallholders are often reliant on a

variety of conditions:

• The implementation of a pricing mechanism formula that’s often prescribed by local or

national governments.

• The world market price, as the price received by smallholders often relies on global

prices.

• Whether the buyer is selling to intermediaries or directly to the mill

• The state and availability of local infrastructure and transport logistics

• The number and capacity of mills that can be reached before the FFB starts to

deteriorate.

• The reliability and fairness of weighing scales and quality control procedures.

• The efficiency of the mill, as the price received by smallholders often relies on the Oil

Extraction Rate (OER).

Farmgate prices are influenced by the national pricing mechanism policies in Indonesia,

Malaysia, Côte d’Ivoire and India (Asante-Poku and Dzifa Torvikey, 2021).

10

From the per-

spective of smallholder inclusivity, it’s important to note that:

• If government authorities set the price for all transactions, it’s crucial that the informa-

tion is widely and freely available to all stakeholders.

• Fixed pricing formulas that include the world price for CPO risk the possible volatility

transmission from the world price to the local price. Most smallholders favor stable

prices that allow them to generate a living income throughout the year. Pricing mecha-

nisms should take into account the ability of smallholders to earn a living income.

Additionally, farmers are constantly facing rapid changes in the market. In May 2022, the In-

donesian government temporarily banned the export of palm oil. As a consequence of this

ban, larger companies could no longer export and storage capacity filled up, leading to mills

reducing production and limiting purchase from smallholders. Through these dynamics,

the volatile market prices squeeze smallholder margins that are already narrow (Llewellyn,

2022).

11

“ Before the ban, we would sell our palm fruit for 3,600

to 3,800 rupiah (USD 0.25 – USD 0.26)per kg. Now the

price has gone down to 2,210 rupiah (USD 0.15) per kg. […]

Farmers have been forced to accept lower and lower prices

for our palm fruit and, in addition to the price of fertilizer

rising, the price of pesticides has also doubled. We are now

losing money and not making any profit.”

Vincentius Haryono,

farmer of four hectares of oil palm, Jambi, Indonesia

“ Our hope is that the price will rise again, but there is a

limit to farmers’ patience, and they are not going to want

to harvest. It’s going to cause social problems if the ban

lasts much longer. How are people meant to pay for their

daily needs? How are they going to send their children to

school? How are they going to buy groceries? ”

Albertus Wawan, farmer of five

hectares of oil palm, West Kalimantan, Indonesia

Although the specific country context of palm oil pricing mechanisms plays a role in

smallholders’ income, it’s important to realize that palm oil is a buyer-driven chain. While

palm oil is increasingly lucrative, with a value of USD 282 billion in 2020, smallholders only

generate USD 17 billion, or six percent of the value in the entire chain (Rijk et al., 2021, see

figure 5). Smallholders lack the economicscaletogenerate the same profit margins as large

plantation companies, but data suggest that they generate the same price level per pro-

ducedmetric ton of CPO. With an extraction rate of CPO from FFB of approximately 20

percent, production per hectare can be 3.5 MT of CPO, making it approximately 10 MT of

CPO per smallholder. Consequently, with a palm oil price of USD 754 per MT (2020), the

average revenue for a smallholder is approximately USD 7,540 per year.

12

With a USD 7,540

per year revenue and an average household of 4.3 people, there’s a high chance of poverty

with this income level. Thus, the concept of ‘profit’ is not applicable to smallholders (Rijk et

al., 2021).Research in Malaysia illustrates this lack of profit margins, and similar patterns are

found in Mexico and Indonesia too:

Malaysia: smallholders consider low prices as a key issue, stating that the average FFB price

for the last 3.5 years hardly covers the cost of operations. This is also related to high input

costs, particularly agrochemical inputs and labor – due to a shortage of workers, small-

holders often have to pay workers higher rates than the commercial plantations. A typical

Malaysian oil palm smallholder has an annual income of USD 8,377 per hectare per year and

makes a net profit of USD 4,236 per hectare per year. The annual national living wage (2019)

for a Malaysian family is between USD 4,021 and USD 5,831. To reach this living wage, an oil

palm farmer in Malaysia needs around 1 to 1.4 hectares.

13

Mexico: a typical Mexican oil palm smallholder has a production area of five to seven

hectares, an annual income of USD 2,813 per hectare per year and makes a net profit of USD

989 per hectare per year. The annual national poverty line for a Mexican family is USD 5,124

and the living income for a rural family is USD 9,312. To reach above the family poverty line,

an oil palm farmer needs around 5.2 hectares. To make a living income, 9.4 hectares are

required. Based on palm oil income alone, this means that the typical farmer with five to

seven hectares under production can generate an income that’s above the national poverty

line, but insufficient to make a living income.

14

Indonesia, West Sulawesi: a 2021 study shows that in 2018, a year with low palm oil prices,

the average total net income from oil palm farming was USD 1,827 per farmer. Oil palm

farmers complemented their income with on-farm and off-farm activities to reach a total

household income of USD 2,129. The average household spending was USD 1,643. While

this might seem a profitable business case, it’s important to note that in the same year the

annual living wage for a typical Indonesian family was between USD 1,724 and 2,372. All sur-

veyed smallholders reported that low and unstable FFB price is a serious problem for them.

The researchers found that lack of management knowledge is another big problem faced by

smallholders, followed by herbicides and fertilizer scarcity.

15

“ It’s getting more and more difficult for farmers with

all these changes in the prices. Some feel as if 50 percent

of their livelihood has been lost as the prices of the fresh

fruit bunches have been slashed and, at the same time, the

prices of fertilizers and pesticides have risen by more than

100 percent.”

Valens Andi, head of the Farmers’ Hope Oil Palm Plantation Cooperative,

West Kalimantan, Indonesia

BOX SMALLHOLDER INCLUSIVENESS

To discuss inclusiveness in the palm oil supply chain, it’s helpful to specify the concept of

inclusivity in relation to smallholder farmers. Vermeulen and Cotula (2010) developed a

typology of smallholder-inclusive agribusiness models spanning the four dimensions of

inclusion; ownership, voice, risk, and reward. The operationalization of these different

aspects allows for an integral perspective on inclusiveness and a better understanding

of the actual conditions under which smallholders are included in business practices

(Schouten and Vellema, 2019).:

1. Ownership: deals with the question who owns what part of the business, and assets

such as land and processing facilities.

2. Voice: the ability of marginalized actors to influence key business decisions, including

weight in decision-making, arrangements for review and grievance, and mechanisms for

dealing with asymmetries in information access.

3. Risk: including commercial (i.e. production, supply and market) risks, but also wider

risks such as political and reputational ones.

4. Reward: the sharing of economic costs and benefits, including price setting and finance

arrangements.

To deliver on all four aspects of inclusive agribusiness, it’s crucial to be aware of the close

interlinkages. For instance, ownership can influence voice, voice in price-setting crucially

affects reward. Ownership influences risk, as a jointly owned business also involves shar-

ing of business risks.

Translating ideas of inclusiveness from scientific thought to the application in the palm oil

sector is not without its challenges. Therefore, we do not strictly follow the above oper-

ationalisation criteria in this report, instead we highlight interlinked elements like income

and value distribution, corporate transparency or participation in MSIs.

FAIR VALUE DISTRIBUTION

While smallholders are struggling to make ends meet, on the downstream end of the chain,

food manufacturers and consumer goods (FMCG) companies and retail manage to gener-

ate 66 percent of the gross profits on embedded palm oil. This is critical for understanding

the distribution of value in the palm oil chain. The focus to cut costs to optimize profits is in

sharp contrast with the individual companies’ sustainability commitments, as well as the glob-

al climate and UN’s Sustainable Development Goal agendas. The underlying concern is that

global palm oil buyers show little willingness to compensate producers for operating sustain-

ably, for example, by paying a premium price or investing in long-term trading relationships.

For instance, WWF highlights the complete lack of demand for certified sustainable palm oil

in the Asian market. This is due to complex challenges such as the persistent lack of transpar-

ency on the palm oil footprint of companies in the region, a low consumer awareness and the

absence of clear labelling of palm oil products (WWF, 2021). Ultimately, companies’ inclusive

business approaches should aim to ensure that smallholders are in a position to safeguard the

wellbeing and rights of the community and the environment (see Box 2). This would create

a more balanced relationship between producers, buyers and service providers. Therefore,

the business and corporate social responsibility perspectives are meant to be integrated, not

separate.

%

%

%

%

%

%

Smallholder

Plantations

Refineries

Oleochemicals

Large companies

Retail

6.1%

14.1%

23.2%

2.8%

24,3%

ADDED VALUE IN CHAIN

PROFIT

Smallholder Plantations Refineries Oleochemicals FMCG Retail

Profit

Smallholder

Plantations

Refineries

Oleochemicals

FMCG

Retail

29,5%

Smallholder farmers’ livelihoods depend on the use of land, forest, other natural resources,

their harvest and price levels. As seen from the above country overview, smallholders are

not a homogenous group. In most geographies, they range from subsistence farmers to

scheme growers and medium enterprise owners. Nevertheless, in their oil palm growing

practices all these small farmers must constantly consider multiple needs including diver-

sifying income, ensuring food security, and protecting cultural values (Jezeer and Pasiec-

znik, 2019). Given the entrepreneurial nature of agriculture, smallholders have to analyze

their options, manage risks and make their own decisions – even in the face of information

asymmetries and unfavorable policies. Naturally, their priorities might be summarized as

improved well-being, stability and creating better future perspectives.

While most smallholders have practical experiences and knowledge of the land, crops and

natural resources, there is a lack of knowledge and skills in processing, logistics and com-

mercialization (Prabowo, 2021; Santika et al., 2019). Mainly because of logistics and the need

to sell FFB within a short time post-harvest, farmers are strongly affiliated with a limited

number of mills or collection centres in their direct vicinity. Combining this with the lack

ADDED VALUE

FIGURE OVERVIEW PROFITABILITY IN THE PALM OIL VALUE CHAIN

%

%

%

%

%

%

Smallholder

Plantations

Refineries

Oleochemicals

Large companies

Retail

6.1%

14.1%

23.2%

2.8%

24,3%

ADDED VALUE IN CHAIN

PROFIT

Smallholder Plantations Refineries Oleochemicals FMCG Retail

Profit

Smallholder

Plantations

Refineries

Oleochemicals

FMCG

Retail

29,5%

of land tenure and access to affordable bank loans, it’s a constant challenge to invest in the

farm itself. Lack of finance, risk avoidance and securing livelihood sustenance are at the

centre of their decisions, which hinders the adoption of farm-level innovations, like better

farm management techniques or adhering to sustainability standards.

The difficulty for most smallholders is having to make livelihood choices while lacking

access to information about market demands, social and extension services, environmental

regulation, and the global market. All of this information is necessary to improve their pro-

ductive capacity and align with sustainability standards. A common issue for smallholders

cited by oil palm farmer organizations is a lack of financial resources. Typically, available cash

is invested in immediate consumption, or reserved for education or health care expens-

es.

16

A fairer value distribution across the palm oil value chain enables farmers to both

escape poverty and make an income that sustains their family’s livelihood.

Explanation: the embedded palm oil supply chain generates a total

value of USD 282 billion, USD 52 billion of gross profit, and USD 18 billion

of operating profit. Retailers generate the largest value (USD 83 billion)

in embedded palm oil. The FMCG sector generates the largest gross

profit at USD 20 billion and an operating profit of USD 6 billion. Although

smallholders generate USD 17 billion, which is six percent of the entire

chain, their share in profits is close to zero (Rijk et al., 2021).

PROFIT

“ The palm industry has really contributed to

the reduction of poverty in our country. But

once we passed the survival stage and started

to see some profits, we started to think that

there were many other factors that we had to

take into account.

Our production should be responsible and

environmentally friendly, we must treat

our workers properly, and maintain good

relationships with the communities around

us. We also realized that we needed to take

it one step further to be able to access other

markets around the world.”

Nelson Araya, General Manager of farmer

group Hondupalma, Honduras

Smallholder

inclusivity

INTRODUCTION

The majority of FMCGs have adopted sustainable palm oil sourcing policies, voluntari-

ly committing to social and environmental best practices, including RSPO certified palm

oil and no deforestation, no peat, no exploitation (NDPE) policies. Or they are pledging

zero-deforestation commitments. However, reaching zero deforestation and smallholder

inclusion are very different goals that must be pursued at the same time. Since FMCGs fre-

quently do not know who their smallholder-suppliers are, let alone where they are located

or what capabilities they have (or do not have) (Lake et al., 2020), it is difficult to deal with

increasingly demanding sustainability challenges. Interest and progress in legal interventions

is growing as a potential stronger mechanism for changing corporate practice. An example

is the upcoming EU-wide legislation on human rights and environmental due diligence in

global supply chains (Drost et al. 2022).

Currently, not all companies’ policies are effective and functional, nor do they reflect the

scale of investments required for the palm oil sector to make meaningful progress. Most oil

palm smallholders are poorly equipped to comply with sustainability standards (Kusuman-

ingtyas, 2019). And, without adequate support, they risk becoming increasingly alienated

from both domestic and global palm oil markets. Ideally, the combination of private sector

commitments, international trade policies, multi-stakeholder collaboration and financial

support are inclusive of smallholder producers. Otherwise these efforts will not halt defor-

estation. Instead they will fail to help these communities to finance the agricultural improve-

ments necessary to thrive (Pasiecznik and Savanije, 2017; Orbitas, 2020). It would be reason-

able to expect an active contribution from all involved to foster smallholder inclusiveness

(see Box 2) in any of these initiatives. By recognizing the need for increasing participation

and encouraging collective action from local people by building on their ideas, it is feasible

to go beyond a short-term technical assistance agenda.

CORPORATE TRANSPARENCY

Upstream the value chain, in the refinery segment only a few dozen refineries (processors/

traders) source from thousands of palm oil mills. These companies are relatively close to

the farmers and most of them are directly involved in the design and implementation of

training programmes to improve and protect economic, social and environmental condi-

tions at the beginning of the palm oil chain. Typically, FMCGs expect their first-tier suppliers

(traders and refiners) to comply with sustainability standards. In turn, they ask for compli-

ance from their suppliers (mills), who ideally ask the same from their suppliers (farmers).

In doing so, the industry claims palm oil can be grown sustainably, responsibly and con-

flict-free (Dauvergne, 2018). By positioning corporate investment, international trade and

industrial-scale production as vital for conservation, food security and rural development,

this industry-friendly narrative is directing criticism towards unsustainable production, with

smallholders in particular being blamed for practices such as deforestation (Austin et al.,

2019; Kusumaningtyas et al., 2019).

Figure 6 is based on information available on the SPOTT (Sustainable Palm Oil Transparency

Toolkit) online platform. It provides an overview of how the 10 main palm oil refineries, pro-

cessors or traders address smallholder issues in their operations.

17

This includes how they

incorporate smallholders into their commitments, disclose information on the smallholders

they source from, and provide details on the levels of support they provide to smallholders

in their supply chains (Dodson et al., 2019).

The combination of SPOTT results and companies’ own sustainability information shows

that companies vary significantly in the transparency and strength of their smallholder

farmer inclusion policies and reporting. If sustainable palm oil is to become the norm,

corporate commitments and sustainability reports give some insights, but the reporting is

rarely easy to compare (Spencer et al., 2019). Furthermore, the available evidence focuses

on policies, without any reference to the resulting change in impacts at farm level or in pur-

chasing practices. This lack of transparency inhibits third parties’ ability to assess the actual

impact of existing smallholder programmes. For example, geolocating production areas can

let companies identify potential risks, engage with suppliers, and measure progress. Ideally,

these geolocation data would include a level of transparency that identified the specific

boundaries of farms where oil palm fruit is harvested (Global Forest Watch, 2022).

18

In re-

ality, for most companies, tracing palm oil to independent smallholder source farms is very

complex, time-consuming, and costly (Sargent et al., 2020). An illustrative example is the

decision by confectionery and pet food producer Mars to limit the number of palm oil mills

in its supply chain from 1,500 to 50 in 2022 (Taylor, 2020). In this scenario smaller farmers

and suppliers could be left behind, continuing with bad practices and selling to global buy-

ers that do not have safeguards on forest protection. At the same time, Mars committed to

long-term contracts with suppliers who in turn work with a lower number of smallholders

in high-risk areas of its supply chain. This shows the balancing act of buyers: while some

smallholders might be left behind by a companies’ supply chain cleaning, others stand to

gain from a stronger relationship.

VOLUNTARY COMMITMENTS

Certified Sustainable Palm Oil

RSPO is the leading sustainable palm oil certification system. It covers a set of environmen-

tal and social criteria with which companies must comply to produce Certified Sustainable

Palm Oil (CSPO). It was created in 2004 with the goal of promoting the growth of the sus-

tainable palm oil sector through credible global standards and engagement of stakeholders.

Today the RSPO has over 5000 members, encompassing the entire supply chain, from oil

palm producers to investors. Only 19 percent of global palm oil production is RSPO certified

(RSPOa, 2022).

19

A major problem is that the RSPO is not yet sufficiently smallholder inclusive (Bitzer and

Steijn, 2019). At this stage the number of certified farmers is still low: only 162,500 small-

holders (22,338 independent and 140,162 scheme smallholders) are certified and produce

almost nine percent of the global CSPO volume (RSPO, 2022b). Scheme smallholders

(producing under contract with large palm oil companies) can be certified more easily,

but independent smallholders often lack organisation, land titles, and training on specific

management practices, which are important preconditions for certification (Pramudya et

al., 2022).

To improve smallholder inclusion into the RSPO system, among other measures, a specific

Independent Smallholder Standard (ISH) was adopted in November 2019 (RSPO, 2022b).

This standard lowers the burden to entry through a phased process for reaching and veri-

fying compliance. Despite many smallholder support programmes, uptake by smallholders

and medium-sized companies remains difficult (RSPO, 2022c). Of course, this strategy will

only succeed if the global market demand creates clear economic incentives for indepen-

dent smallholder producers, like price premiums or access to markets.

FMCGs and other companies can directly incentivize smallholders by purchasing RSPO

Credits via the online trading platform PalmTrace (RSPO, 2022d). From July 2020 to June

2021, 47 independent smallholder groups raised almost USD 3 million through RSPO Credits.

There’s a lot of room for growth, since only 64 tonnes or 0.1 percent of the global volume

is covered by ISH credits.

20

This support not only builds an end-to-end value chain but also

generates resources that can be invested in farmers’ businesses, benefitting the wider com-

munity (Prabowo, 2021).

Multi-stakeholder initiatives

Certification is just one aspect that can make palm oil production more sustainable – it’s not

sufficient to resolve all the sector’s pressing problems. This requires more collective action

of a wide range of stakeholders, including the private sector, governments, civil society

and farmer organizations. The most influential sector partnerships and MSIs are presented

in figure 7 and include the RSPO, the Consumer Goods Forum’s Forest Positive Coalition

(CGFFPC), the Palm Oil Collaboration Group (POCG) and the Accountability Framework

Initiative (AFI). A potential benefit of these partnerships is that they can help stakeholders

to better understand the challenges of others in the sector and identify opportunities to ac-

knowledge successes and share best practices via collaboration. Ideally, they reduce the sec-

tor’s fragmentation of sustainability efforts and enhance transparency and accountability.

SPOTT indicator

SPOTT

nr.

Wilmar

Musim

Mas

Apical

Group

HSA

Group

LDC

Sime

Darby

Cargill

Mewah

Group

IOI Group Bunge

Commitment to support smallholders

160

Programme to support scheme/plasma

smallholders

161

Percentage of scheme/plasma smallholders

involved in programme

162

Programme to support independent smallholders

163

Percentage of independent smallholders

outgrowers involved in programme

164

Process used to prioritise, assess and/or engage

suppliers on compliance with company’s policy

and/or legal requirements ESG

165

Number or percentage of suppliers assessed

and/or engaged on compliance with company

requirements ESG

166

We are making good progress in achieving

certification for our scheme smallholders

with about 31% of scheme smallholder areas

across Indonesia and Ghana RSPO-certified

at end 2020.

All six of the company’s sister companies commit

to support smallholders. However PT OSI is the

only company to disclose the nature of this com-

mitment. These commitments also do not

clearly cover all smallholders i.e. scheme/

plasma smallholders