The George Washington University

School of Medicine and Health Sciences

“Guide to the 4

th

Year”

(Transition to Advanced Clinical Practice)

Everything You Need to Know about Senior Year and Successful Residency Matching

Prepared for the Class of 2025 by

The Offices of Student Affairs & Curricular Affairs

Table

of

Contents

Introduction ................................................................................. 4

Timetable ..................................................................................... 5

Career Decision-Making ............................................................. 7

What Should I be Doing/Thinking? ........................................................................................................... 7

Considerations in Specialty Choice ............................................................................................................ 7

Changing Residencies ................................................................................................................................ 8

Planning the Fourth Year ............................................................ 9

Goals ........................................................................................................................................................... 9

Scheduling................................................................................................................................................... 9

Graduation Requirements ........................................................................................................................... 9

Independent Study ..................................................................................................................................... 10

Electives ..................................................................................................................................................... 10

On-Campus Electives ................................................................................................................................ 10

Off-Campus Electives (“away” or “extramural”) ......................................................................................... 11

Visiting Student Learning Opportunities (VSLO) ...................................................................................... 11

Advantages and Disadvantages of Off-Campus (Away/Extramural) Electives........................................ 12

Timetable for Arranging Off-Campus Electives ........................................................................................ 12

Off-Campus Living Arrangements ............................................................................................................ 12

Arranging Away Electives .......................................................................................................................... 12

Documents Required for Away Electives (in order) .................................................................................. 13

International Electives ............................................................................................................................... 14

Military Active Duty Tours ........................................................................................................................ 14

Electives at The National Institutes of Health .......................................................................................... 14

USMLE STEP-2 Overview ........................................................................................................................ 15

Exam Failure and Consequences .............................................................................................................. 15

Exam Format ............................................................................................................................................. 15

USMLE Exam Scheduling ........................................................................................................................ 15

Faculty Advisors ......................................................................................................................................... 16

Letters of Recommendation ...................................................................................................................... 16

Applying for Residency .............................................................. 17

How do programs select residents? ........................................................................................................... 17

How to decide and where to apply ............................................................................................................ 17

How do you know if you are competitive? ................................................................................................. 18

Competitiveness: Strategies to Protect Yourself ........................................................................................ 21

The Application Process ............................................................................................................................ 21

The Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS) ............................................................................22

Interviewing ...............................................................................................................................................22

How to Assess a Program During your Interview? ...................................................................................23

Supporting Materials ..................................................................................................................................24

New Trends in the Application Process ....................................................................................................25

The Match .................................................................................. 27

The National Residency Matching Program ............................................................................................. 27

Types of Programs ..................................................................................................................................... 28

Alternative Matching Possibilities in the NRMP ...................................................................................... 28

The Military Match .................................................................................................................................... 28

Canadian Students ..................................................................................................................................... 29

Specifics of Planning your Fourth Year ...................................... 31

Lottery ........................................................................................................................................................ 31

Consultation with your career advisory dean ............................................................................................. 31

Specific Scheduling Issues ......................................................................................................................... 31

Appendix A: Fourth Year Calendar 2024-25 ............................... 34

Appendix B: Interview Tips for the Residency Process ............. 35

Advance Planning: ..................................................................................................................................... 35

The Interview Day ..................................................................................................................................... 36

After the Interview...................................................................................................................................... 37

Appendix C: Residency Program Evaluation ............................ 43

Inpatient Experiences ................................................................................................................................ 43

Ambulatory Experiences ............................................................................................................................ 43

Special Educational Opportunities ............................................................................................................ 43

Residency Outcomes ................................................................................................................................. 44

Miscellaneous ............................................................................................................................................. 44

GUT CHECK (circle one) ......................................................................................................................... 44

Appendix D: Tips for Career Selection during Year III ............. 45

Overview .................................................................................................................................................... 45

Tips for Career Selection ............................................................................................................................ 45

Appendix E: Prior NRMP Match Data (LINK) ........................... 46

Appendix F: Writing a Curriculum Vitae ................................... 51

Writing a Curriculum Vitae (CV) ............................................................................................................... 51

CV Components ......................................................................................................................................... 51

Appendix G: Sample Curriculum Vitae ...................................... 53

Appendix H: Previous Residency Matchlist .............................. 56

Appendix I: Saving Money ....................................................... 70

Saving Money on Residency Travels ....................................................................................................... 70

Saving Money on Housing during Interviews .......................................................................................... 70

Guide to the Transition to Advanced Clinical Practice | 4

Introduction

Most of you have already started to think about what your career as a physician will entail. During the next several

months, you will begin to make important choices about specialty selection, residency training, and beyond. The

process of making these decisions is exciting and challenging, and this manual can help guide you. The guide is by

no means an exhaustive source of information. There are many sources of more specific information, and you

should take advantage of everything available to you. The time and attention that you invest in this process has

invaluable dividends. Get organized early, make note of important dates and deadlines and keep an eye on your

email inbox!

Guide to the Transition to Advanced Clinical Practice | 5

Timetable

It is critical for you to understand the timetable involved in planning residency applications. The schedule below

should serve as a guide as you plan your approach to the process. Please note that many of the websites mentioned

will update information for the upcoming residency application cycle in the next several months, so visit the sites

often. Students interested in Plastic Surgery, Ophthalmology, and Urology should note that the match process for

these specialties occurs early. Additionally, students in the Military Health Professions Scholarship Program

participate in an early match.

Third Year

Winter

Break

1. Reflect on clinical experiences and interactions with faculty and residents during the clerkships as

you begin the process of specialty selection.

2. Revisit the Careers in Medicine website (link) hosted by the AAMC (Use your AAMC ID to

login).

3. Review FREIDA online (link).

This is a searchable electronic database of all residency and fellowship programs in the U.S.

Review the Roadmap to Residency Site (link).

Review and complete the Google Portfolio Form, which will be utilized through the 2024 Match

Cycle.

4. Review the National Resident Matching Program publication, Charting Outcomes in the Match

(link).

This report casts light on how applicant qualifications affect match success.

5. Military Students: Start planning Active Duty Tours (Military Away Rotations) (link)

•

Army Students should review the information at:

http://www.goarmy.com/amedd/education.html

•

Navy Students should review the information at:

Graduate Medical Education (navy.mil)

•

Air Force Students should review the information at:

Application Instructions (af.mil) and 2022 Checklist (af.mil)

Military Residency Catalog:

http

s://www.usuaoa.org/program-previews

January

2024

1. Be sure to attend specialty night events with faculty in the areas of your interest. This may

include faculty at other institutions. Connect with current fourth year students in the areas of

your interest; they have completed applications, are on the interview trail, and have lots of

valuable information to share.

2. Review the Clinical Course Catalog (link) and plan your fourth year schedule. Use this guide and

the “Self-Assessment” scheduling guide in the Appendix. It may help to discuss this with your

Career Advisory Dean or a specialty advisor early in the process.

3. Enter your fourth year schedule requests into the web-based lottery system.

4. Consider fourth year electives at outside institutions and investigate deadlines for these

applications. Many medical schools will use the Visiting Student Learning Opportunities

website (link). Become familiar with the process.

5.

VSLO Authorizations are issued by the Deans Office.

February

2024

1. Select an official GW Faculty Advisor from the list provided by the

dean’s office (you can have more than one if you are considering multiple specialties).

2. Lottery results emailed to students

3.

Students begin to meet individually with Career Advisory Dean to review and modify schedules.

You will be assigned a time and date for this required meeting.

Guide to the Transition to Advanced Clinical Practice | 6

March-April

2024

Register for USMLE-2 to be taken by mid August

May 2024

Complete your Google Roadmap to Residency Longitudinal Questionnaire and personal statement

draft.

June

2024

Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS) opens. Review the ERAS website (link) and

take note of all deadlines.

Situational judgment exams for Altus (if required/requested) should be scheduled by July 1

st

for select

specialties and programs.

Fourth Year

July

2024

Early Match (Ophthalmology and Urology) begins registration.

See Ophthalmology Match timeline here. See Urology timeline here.

August

2024

1. Complete application materials

2. Review transcripts for accuracy

3. Target date for Ophthalmology applications: August 15

4. Military students complete application

September

2024

1.

Students submit ERAS Supplemental Applications and register for NRMP Sept 15-19. All

students participating in NRMP match should register without delay once NRMP registration opens

2.

Students submit ERAS Application by Sept 28. MSPE, Transcript, LORs uploaded by Sept 29.

October

2024

1. Interviews for students participating in the NRMP, SF Match, and Urology Match begin.

2. Many specialties batch interview offers on uniform release dates.

Sept -

November

2024

Complete the weekly Student Affairs Interview Questionnaire

December

2024

Military Match complete

January

2025

San Francisco Match (Ophthalmology) and Urology matches complete

NRMP Registration deadline

February

2025

NRMP Rank lists due

March

2025

1. SOAP (Supplemental Offer and Acceptance Program) for unmatched students

2. NRMP Match Day

Guide to the Transition to Advanced Clinical Practice | 7

Career Decision-Making

What Should I be Doing/Thinking?

It is difficult to plan a fourth-year schedule effectively without having a fair amount of the third year under your belt

and some sense of your ultimate career direction. By January, you should begin to think about your career direction.

While it is premature to try to identify formal advisors in January (they’re still busy with fourth year students) there

is no harm, and it is very helpful, to talk with the more senior physicians with whom you work (residents,

attendings, etc.) about their career decision process. How did these people choose their specialty? What did the

residents and seniors do as electives? What really helped? Many third-year students feel confused with regard to

career selection. Next year by this time, almost all of you will have a very firm grasp of where you are and where you

are going. Those of you who already “know” ought to be a bit concerned: Have you come to a conclusion

prematurely and without reviewing all of the options? The Roadmap to Residency series can be your comprehensive

guide for career planning.

Considerations in Specialty Choice

Role of Core Rotations: While you are beginning to talk with people about career choices, you must firmly keep in mind

that your third-year rotations will give you an exposure to predominantly hospital-based medical practices. You can

certainly get some sense of a specialty by looking at what you see in our hospital clerkships, but you have to be very

careful not to assume that the life of the practitioner is similar to that of a third year clerk, the resident staff, or even

the full-time faculty on that service in the hospital. Also, remember that most residents primarily have experience

with in-hospital medicine. While it is appropriate and important to talk with senior students and residents - they are

closest to you and closest to having made career decisions -- practitioners are a more reliable and valid source of

information.

Therefore, it is important to talk with experienced physicians, particularly those in practice, to get some idea of what

the various generalists/specialists do in the “real” world. Don’t hesitate to stop attendings whom you know (and

even some you don’t know!) and ask questions. Talk to as many people as possible. Most of them will understand

your quandary and be delighted to share their points of view with you. While the primary care clerkship is not a

perfect representation of office experience, it is much closer to routine medical care than what you see in a hospital.

(Recall that only about 5% of an average physician’s patients have problems needing hospitalization in a given year,

much less in some specialties.) Keep your ambulatory experiences in mind!

Stereotypes and Biases: Stereotypes of practitioners in the various specialties must be recognized as having some real

basis, but many exceptions exist. For example, it is possible to be a very patient and long-term care oriented

surgeon, and conversely, a procedure-oriented and intensivist internal medicine physician. The kinds of people with

whom you feel most comfortable are likely to be the people with whom you will be most happy training with for

long and grueling hours. If you think you love a specialty but hate the physicians practicing it, you had better be

careful; the process of socialization throughout residency training is incredibly powerful. You need to consider the

duration of training: Are you able to postpone goal achievement sufficiently to tolerate a seven-year residency?

Lifestyle and Income: Many of you may want to consider the practice style and income of practitioners in various

specialties: Academicians tend to be paid less than private practitioners, pediatricians usually make much less than

surgeons. How important are these considerations to you to your spouse? All doctors work fairly hard and most of

you when applying to medical school said one of the attractions was that medicine was not in the “9 to 5” mentality.

Have you changed? Are you willing to make sacrifices for the needs of your patients? How much control of your

time do you demand? Are you willing to limit your practice to a certain patient population or age group (e.g.,

childbearing women, children, adults) or do you want to care for all people?

Personal Development: Another facet of this conundrum that you need to keep in mind is that we change over time!

Many students and residents enjoy being at the “cutting edge” of their field. Many like intensive/critical situations.

Guide to the Transition to Advanced Clinical Practice | 8

However, many physicians will tell you that their substantial joys during mid- practice years come from being of

service and making a difference in the lives of their patients. How can you know how you will feel in 15 years? You

probably can’t but you ought to be aware of this common change in older physicians.

Steps to Determine Final Choice: Finally, if you have narrowed your choice down to two or three options but don’t

seem to be getting any further, try a little exercise. Decide on one choice (“I’m going to be an obstetrician”) and live

with that choice for a week. See how you like being an obstetrician. How does your spouse like it, your family and

friends? During the day and evening try to picture how you would be spending your time, what your patients would

be like. After a week, try another choice (“I’m going to be a neurologist”) and live with that for a week. This will

help you focus on one at a time rather than having to constantly weigh one against another. In addition, scheduling

early experiences in your fourth year in a variety of specialties may give you further insight that will help you narrow

down your options. An early visit to one of the deans may also be helpful if you are in a particular quandary.

There are numerous written sources of information on choosing a specialty. Many of these are mentioned above in

the timeline table. In addition, we will hold another “Specialty Night” in January when you can meet faculty or

program directors from most of the major specialty areas.

Like all important decisions, your specialty choice will require you to spend many hours thinking, reading, and

discussing your options. Your advisors and the deans are an important resource that you should take advantage of.

Changing Residencies

Once you have made a decision about a career path and started a residency, it may be challenging to switch to

another specialty. This is largely a result of the way residency positions are funded. It is important that you be aware

of the way Medicare reimburses medical centers for postgraduate training.

Historically, Medicare paid each medical center around $30-50,000 each year for each resident. This varies

substantially from specialty to specialty, since it is determined by complicated formulas based on the Medicare

population served by that institution. Thus, for some programs it will be very high, while for others it may be much

lower. This subsidy is designed to offset the expenses of training residents (faculty, learning resources, etc.).

Medicare will only support residents for fixed periods of time linked to their specialty training (for instance, 3 years

for internal medicine, 5 years for general surgery, etc.). If you stay in residency beyond that time period, the medical

center only receives half of the original training subsidy (i.e. you essentially become fiscal red ink to the medical

center!).

The problem is not so much that you will stay longer in your original residency choice, but that this makes it

difficult to change residency programs in mid-stream. If you do two years in medicine and decide to switch

specialties, you will have only one full year of financing left. Therefore, any surgery program that wants to take you

will have to forfeit four years of full support. As you may imagine, this puts you at a disadvantage relative to freshly

minted graduates who have not used up any of their eligibility. This is making it more difficult to change residency

training once you have started. This means that you need to be as certain as possible about your plans at the time of

your original match.

Guide to the Transition to Advanced Clinical Practice | 9

Planning the Fourth Year

Goals

The fourth year comprises one quarter of your medical education. It is especially important because it is the crucial

time for you to solidify and broaden the foundation you have built in the first three years. In addition, it has

importance beyond your immediate educational needs: It is the time to better understand your residency options

and enhance your opportunities for the transition to your postgraduate years.

The goals then for the fourth year are:

Primary

To broaden your medical education (especially through your required courses)

To deepen your medical education (through your skillful selection of pertinent electives)

To solidify areas of weakness

Secondary

To gain more experience in areas of medicine to help you make a career choice.

To improve your chances for a successful match by: working hard and doing well in your fourth year

courses; working closely with faculty who might write your letters of recommendation; working in outside

hospitals to see if you would like being a resident there.

Scheduling

In January of your third year, we will use a “lottery” system for you to schedule your fourth year similar to that used

for scheduling your third year. In brief, you will initially choose courses both within and outside the GW system. We

have a fairly sophisticated computer algorithm to help you get your preferred schedule. After the lottery, your

Career Advisory Dean will meet with each of you and review the first draft of your schedule. During that time, we

will make all the appropriate modifications. A period of grace will follow during which you will be able to make

additional changes and finalize electives before the ADD/DROP procedure (LINK) goes into effect.

The purpose of this entire process is to get you your optimal schedule and simultaneously to allow our faculty

sufficient time to arrange for students from other medical schools to participate in our elective programs. (Note: we

will not accommodate outside students until your first scheduling deadline has passed.) In addition, the rising third

year class will select their preferences after you have selected yours.

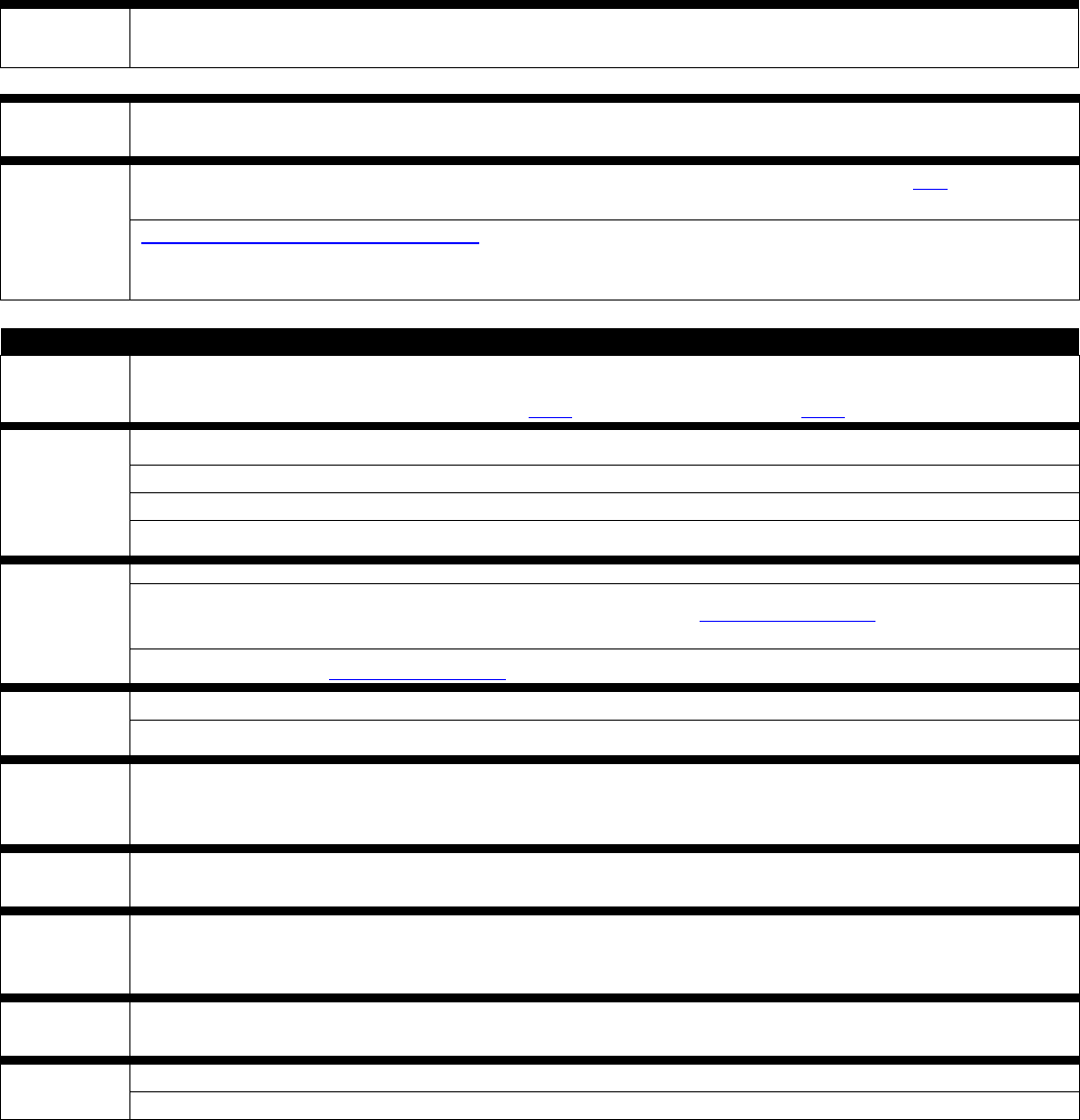

Graduation Requirements*

Course Name Duration Comments

Intersession IV

7 days

Intersession IV occurs Monday through Friday during week 44 at the start

of your 4

th

year

Acting Internship

4 weeks

Any one of the following satisfies this requirement: An Acting Internship

in Medicine or Pediatrics or General Surgery or Critical

Care/Anesthesiology (GW Hospital Intensive Care Unit), inpatient

Family Medicine (IDIS 390 extramurally), or Pediatric Intensive Care.

Guide to the Transition to Advanced Clinical Practice | 10

Anesthesiology (may be

completed in the third

year)

2 weeks

ANES 380 or ANES 302 satisfies this requirement. If taking the 4-week

ANES 380 Sub-I, this counts for 2 weeks anesthesia requirement and 2

weeks free choice electives.

Emergency Medicine 4 weeks

Adult (EMED 302) or Pediatric Emergency Medicine (PED 405) satisfies

this requirement.

Neuroscience (may be

completed in the third

year)

4 weeks

All students register for NEUR 380. This may be taken in the third or

fourth year, but must be completed at GW/affiliates. Students will be

assigned to various local sites according to a lottery system and will

receive

information via email about the site lottery about one month prior to the

block. Choices will include adult and pediatric neurology and

neurosurgery

sites, and will include both outpatient and inpatient experiences.

Transition to Residency

4 weeks

Taught weeks 36, 37, 38 and 39, coinciding with Match Day. All

graduating seniors are required to attend this course at GW. No other

course work can be scheduled at this time.

Free Choice Electives

in MS3 + MS4 years

26 weeks

minimum

These 26 weeks include any electives completed for credit during the third

year. On-campus electives are listed in the online course catalog. Off-

campus “away” or “extramural” electives may be arranged by the student

with the approval of the appropriate GW department and the dean’s

office. (more on this later)** may be impacted by COVID.

Independent Study

14 weeks

maximum

This is flexible time to be used for USMLE study, interviews, making up

missed clerkship time, etc. This does not count towards your elective 26

week elective requirement.

*in addition to completing all seven core clerkships. See Coursework Requirements for Class of

2025: LINK

Independent Study

You will have 14 weeks of independent study time that you are free to include in your schedule at any time.

Remember that in addition to time for relaxation, you will use independent study weeks to study for step 2, make up

any missed clerkship time, and to interview for residency. In addition, students have a mandatory additional vacation

week 1, June 27 – July 3, 2022 plus winter break (weeks 26 and 27) that is not counted in the 18 weeks. Remember

that during the Transitions to Advanced Clinical Practice phase there are NO guaranteed holidays off

(see duty hour policy) Any third year clerkship make-up time or any non-credit accruing academic work in year 4 is

deducted from your Independent Study time.

Electives

While we want you to use your fourth year to help you find a residency, we need to assure the broad educational

value of the year. We have accordingly employed a policy that restricts the amount of time a student can spend in a

specialty area to 12 weeks. This applies to individual specialties, not broad specialty areas. For instance, you could

take 6 weeks of general surgery, 4 weeks of trauma surgery, and 4 weeks of colorectal surgery without violating the

rule. However, 14 weeks of general surgery would not be permitted. Likewise, a mixture of medical, pediatric

Guide to the Transition to Advanced Clinical Practice | 11

surgical subspecialties are permissible, but you are not permitted to do more than 12 weeks of cardiology for

instance. Note: you can spend more than 12 weeks in a specialty area, but anything above 12 will not count towards

your course requirements and will be deducted from your vacation time.

On-Campus Elective

Any elective controlled by the GW elective registration system will be listed in our online Clinical Course Catalog,

and is considered on-campus. Any elective not listed in the catalog is considered off-campus.

Off-Campus Electives (“away” or “extramural”)

What are the Purposes for Doing Electives “away” from the Medical Center?

First, there is very little available outside of GW that one could not arrange to do within our system. For financial

and personal reasons, many of you will not be able to take electives away from the school. This is not a problem or a

liability for most specialties. However, some specialties may strongly encourage applicants to complete an

extramural "audition" elective in the summer months of the early MS4 year. (Please be sure to talk with your

specialty advisor regarding the utility of doing an away rotation.) Please be reminded that no additional financial

aid can be awarded to cover the extra costs of spending time on off-campus electives unless the rotation is outside

of the U.S., is credit bearing, and is taken as part of the Global Health Scholarly Concentration.)

Pre-COVID, about 30% of students took no away electives, 40% did one month away, and 30% did two or more

months off-campus. It is difficult to assess whether these rotations substantially helped students get their desired

residencies. Most students do not match to residency programs at which they did an extramural elective (excluding

military scholarship students). Visiting the program is no guarantee that it will remain top on your list, nor an

assurance of matching there. Given the timing of residency applications and interviews in the senior year it is VERY

DIFFICULT to do more than two extramural electives in your specialty of choice. Since most of you will apply to

20-50 residency programs it is obvious that you will only be able to do an away elective at a tiny fraction of the

programs that you are interested in. Therefore, if you choose to do this, you will have to pick a program(s) that you

are convinced may be the right place for you. See below for advantages and disadvantages of away electives.

Visiting Student Learning Opportunities (VSLO) / Visiting Student Application Service

(VSAS)

Visiting Student Learning Opportunities (VSLO), also referred to as the “Visiting Student Application Service”

(VSAS) (link) is an AAMC service designed to streamline the application process for senior “away” electives at other

U.S. LCME accredited medical schools, including in-person away electives as well as virtual experiences. Students

submit just one application for all participating schools, effectively reducing paperwork, miscommunication, and

time. VSAS also provides a centralized location for managing offers and tracking decisions. You will use VSAS if

you are applying for senior away electives at any of the host schools listed on the VSAS website. When applying for

electives at schools that are not using VSAS, you will need multiple documents. Different schools require different

combinations of these documents. The table below lists the various documents and where/how to get them

completed.

Other medical schools keep course directories online at their websites along with instructions and forms for

applications. These directories will be the most valuable source of information about off-campus electives and

application procedures. It is your obligation to be sure that the elective you are investigating outside of GW is at

least as good as the elective available within our own program. Senior students can be useful resources on these

issues. Also if you are interested in a particular hospital or program you might stop by the Dean’s office and review

lists of recent graduates and the programs to which they matched. It is often very useful to contact GW graduates

working at hospitals of interest, and ask them to recommend the best electives, the best teachers, etc. If we can help

with this, let us know.

Guide to the Transition to Advanced Clinical Practice | 12

Finally, most medical schools and many residencies now have very informative websites where you can find

important information. Students with prior academic difficulty must meet with one of the deans to determine if in-

person off-campus electives are permissible.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Off-Campus (Away/Extramural) In-Person Electives

There are some good reasons to take electives at other institutions:

Allows you to compare GW to other medical schools and yourself to other students.

Allows you to see if you will be comfortable with the geography and culture of the areas in which you are

thinking of practicing or training.

May be a good way to get a feel for the specialty.

May help your residency chances at that program. If you will be aiming high and you perform well, you may

make a more vivid impression at a prestigious program by taking an elective there.

May gain you a letter of recommendation from someone outside of GW. Such a letter may be viewed as more

objective than a letter from a GW faculty member (who has a vested interest in seeing GW graduates do well).

However, many of you will find the process of locating and scheduling extramural electives to be bothersome

and time consuming. It may be difficult to get the elective you want. Notification of acceptance to such electives

can be delayed into the summer or fall. Away or “audition” electives can be a double-edged sword. You may

look good, perform well, and impress, but you can also look flat and disoriented at new facilities in unfamiliar

surroundings. Know yourself!

There are also some risks in spending a substantial portion of the fourth year away. If you are planning on going

into a clinical residency, letters of evaluation are crucial to your success in matching. The evaluative comments that

are most important tend to be those written by clinicians. It is sometimes difficult for faculty to get to know you

(and for you to know them!) during your third year. Accordingly, some students use the early part of the fourth year

to know and be known by our faculty -- the group most interested in getting you a top residency. Many letters of

recommendation are written by members of our faculty with whom you work in the summer and early fall of your

fourth year. There are other disadvantages to away electives. Historically, we have done very well in terms of

advising and helping students match to good postgraduate programs. That advising does not readily take place long

distance. Our faculty is often willing to contact friends at other institutions, to put in a good word for students they

know. That does not happen when you have been away for the entire fall. Taking care of the details that are so

important to this whole process can be difficult from a long distance.

Timetable for Arranging In-Person Off-Campus Electives

Plan to begin submitting applications for away rotations by the start of February of your MS3 year (February 2024).

Most medical centers with active elective programs will not begin signing-up an outside student until early spring.

They may accept applications as early as December 2023, but they will rarely commit to a specific course schedule

until sometime in February-April 2024. Many schools will be unable to accommodate requests to complete an away

elective during the end of the 3rd year (May, June).

Many of you, although early on inclined toward a particular medical field, will make substantial changes in your

timetable during the remainder of this year. Therefore 1) don’t get yourself locked into one or a set of programs that

may have no bearing or meaning to your ultimate training plans; 2) don’t commit yourself to programs without

complete and careful discussion of your options and opportunities here, as well as away, with at least one advisor;

and 3) don’t get yourself or GW a bad reputation at hospitals for signing-up but then reneging on a prematurely

arranged elective!

Off-Campus Living Arrangements

You will usually have to arrange your own housing at any extramural site that you attend.

Arranging Away Electives

Guide to the Transition to Advanced Clinical Practice | 13

All students taking off-campus electives must get prior approval to participate in these courses. You must have a

“Permission to take Extramural elective” form on file in the dean’s office before going to any off-campus rotation.

Permission to take an off campus elective is granted by a course director in the department that coincides with

your requested elective. For example, if you want to do an away elective in general surgery at Georgetown, you must

get permission from the GW General Surgery clerkship director. This permission form is found electronically on

the GW SMHS website (Current Students->Forms). All students must have a GW Uniform Clinical Evaluation

Form completed for their away rotations, which is then sent back to our registrar. Students are also required to

complete an evaluation of the off-campus elective experience.

Documents Required for In-Person Away Electives*

Document

Provided by

Comments

Affiliation Agreement for

all non-VSLO institutions

Dean’s office (Sherry

Brody)

Budget at least 3-6-months for an affiliation agreement to be

ratified by both GW SMHS and host institution. Note: it is

possible that an agreement cannot ultimately be reached.

You

may not rotate at an institution without a signed

agreement

in place. [This is not necessary if you apply

through VSLO.]

Application Form from

the

host institution (non-

VSLO

institutions)

Dean’s office (Registrar,

Career advisory dean)

Generally

these require a section to be completed by your

career advisory dean, signed and sealed with the official

school seal. Turnaround time: 1

-2 business days

Curriculum Vitae

Student

See Appendices F & G

Profile Photo

Student

Criminal Background

Check/Drug Testing

Dean’s office

(Vendor: Certiphi®)

Most schools will accept your previous results obtained

dur

ing your second year in preparation for your clinical

clerkship

rotation. Some schools will require that you have

this done again (possibly at your expense) prior to the

rotation;

the school can provide information on vendors to

have this completed.

Official Transcript

Student Center

Most

VSLO participants will accept unofficial transcripts

uploaded by the dean’s office. Official transcripts are

handled by the University Registrar.

HIPAA Certification

Office of Medical

Education

Completion of HIPAA modules is currently a requirement

for successful completion of POM. Documentation of

successful completion of HIPAA is provided as part of the

General

Letter of Good Standing. If the institution requires

additional information, please contact OSA for assis

tance

Immunization Record

MedHub, Student,

Employee Health

Most VSLO participants require the AAMC Standardized

Immunization

Form (link). Some schools have their own

immu

nization forms. Students should complete these

forms in conjunction with Employee Health or their

primary care provider.

Proof of Health Insurance Student

Photocopy

of your insurance card (front and back)

Basic Life Support (BLS)

Certification

Tel: 202-741-2958

Email: gwtrainingcenter@

mfa.gwu.edu

Photocopy

of your BLS card (front and back)

Guide to the Transition to Advanced Clinical Practice | 14

Proof of Malpractice

Insurance (aka Certificate

of Insurance / COI)

Dean’s office (Sherry

Brody)

$2

Million (Each Claim)

$3

Million (Aggregate)

Mask Fit

GW Health & Emergency

Management Services

Tel: 202-994-8425

Email: [email protected]

Letter of Good Standing

(LOGS)

Dean’s office

Submit your request to the Dean’s office administrators

using

the LOGS request form found on the website (Letter

of Good Standing/Recommendation Request (gwu.edu)

).

Completed

letters are generally available for pick up within

24- 48 hours.

Official School Seal

Dean’s office (Registrar)

Upon acceptance,

complete

“Permission to Take Off-

Campus Elective

Form” (Permission to take

Extramural elective)

GW Clerkship Director in

the specialty area you are

requesting to do your away

elective.

For

example, if you want to do an away surgery elective you

must have permission from the surgery clerkship director.

This

ensures that our students are steered to programs with

the most educational value. Turn

completed forms into the

dean’s office

*Virtual electives may require only a portion of these required elements.

International Electives

There are specific and legitimate reasons for some students to study abroad. Students with a strong interest in

differing health administration systems have spent time in countries with different health care systems. Others have

gone abroad because of an interest in Global Health or participation in the Scholarly Concentration Program.

Others, usually strong and very independent students, have done a primary care experience in a third world country.

These electives may need to be planned a year in advance.

GW has several formal programs and exchanges with international programs and schools. For information about

the location, timing, and application procedures refer to details in the online Course Catalog, or contact the Office

of International Medicine Programs. All medical students participating in international clinical electives or summer

internships, regardless of whether they are in the Global Health Scholarly Concentration or not, must register and

apply through the International Medicine Programs (IMP) office and obtain permission from their career advisory

dean. Also see the school policy on international electives Students interested in international electives at non-

affiliated sites must inquire with and obtain permission at least three months in advance of the elective from the

Office of International Medicine Programs.

Military Active Duty Tours

Those of you in the military should make contact with your program office in the fall/winter of your third year to

arrange for active duty tours in the early summer. If at all possible, it will work to your advantage if you are able to

identify the specialty of your ultimate interest, and the hospital in which you are most interested in working by

winter break of your third year.

Electives at The National Institutes of Health

Another valuable elective experience is at the NIH which offers both clinical and research electives. Additional

information may be available through the Scholarly Concentration in Clinical and Translational Research or OSPE.

Guide to the Transition to Advanced Clinical Practice | 15

USMLE STEP-2 Overview

Most residency programs are placing increased value on the USMLE Step 2 score when determining which

applicants to interview and subsequently rank. Virtually all programs want a USMLE Step 2 score before offering

interviews to applicants. and, nearly all programs require a Step 2 score prior to ranking applicants Consequently,

it is imperative that you allocate the proper amount of study time in preparation for taking USMLE Step 2.

Common errors that lead to suboptimal scores include:

Taking less than 4 weeks to prepare for USMLE Step 2

Failure to schedule a meeting with Dean Goldberg if you’ve had repeated difficulties with standardized tests

in the past or a marginal performance on Step 1

Preparing for the exam while doing other activities (electives, family obligations, interviews, etc.)

Exam Failure and Consequences

Failure of a USMLE examination can adversely affect your chances of successfully matching. Failure of step-2

though has its own unique challenges:

Step-2 is focused on clinical knowledge. Consequently, some programs consider it more predictive of

your ability to function as a resident, and they will be less forgiving of a step-2 failure.

Depending on when you initially scheduled the exam you may have limited time to study and retake it

before residency programs beginning offering interviews in late Summer/Autumn.

Exam Format

The USMLE-2 exam will be administered at Prometric Technology Centers throughout the US. There are nine

centers within a one hour drive of GW, and additional centers throughout the US. The CS exam was previously

administered at five regional centers, the closest location is in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Scheduling

When you apply for the Step 2 examination, you will designate a three-month window in which you would like to

take it. Once your application has been processed (about 6 weeks), you will receive certification allowing you to call

Prometric or the NBME in order to schedule a testing date at the center of your choice. Scheduling can be done

starting 6 months before the date of the exam. Please visit www.nbme.org for the most current information on

application procedures, costs, and deadlines.

We recommend that you complete the scheduling process for USMLE Step 2 no later than the beginning

There is no fee to change dates if done more than 14 calendar days in advance. If

you wait until the summer, you may have trouble scheduling the exams. Remember you are required to complete

both components of the exam by November 1 of your fourth year. If you have not passed the exams by

graduation, you will not receive a diploma. If you do not receive a diploma at graduation, the University will not

issue a diploma until June 30 or later! Consequently, you may not be able to start your residency rotation on time.

of March of your third year.

Guide to the Transition to Advanced Clinical Practice | 16

More and more residency program directors want to see your Step 2 scores BEFORE they begin to offer

interviews in October - November. The military programs have historically required that scholarship students sit for

Step 2 by the end of August or September. For the rest of you, there are a number of considerations. First, many

residency programs like to see your Step 2 scores during the residency application process (particularly programs

in more competitive training fields; you must have it by September for OB/GYN). Second, if you performed

marginally on Step 1, a good score on Step 2 may help your application significantly.

Our fourth year overview is now complete. In the next few chapters we will discuss advisors, applying for

residencies, and the Match, and then finish with two chapters on the specifics of how to design your fourth year.

Advisors

Advisors are guides, sources of information, and sources of contact with the “outside” for the remainder of your

stay at GW. Ideally, an advisor should be knowledgeable about the elective programs available here and elsewhere,

knowledgeable about residency programs over the whole country, willing to find out more about you and your

abilities, able to make you feel comfortable and able to get things done! In the real world, however, no one person

can do all these things well. Try to select an advisor that suits your specific needs best. It is particularly important to

select a person with whom you feel comfortable talking honestly. If your advisor is not well versed in a particular

area, seek out other people who are. Many specialties have designated a faculty member to serve as the key advising

figure for all students applying in their specialty (often a Residency Director, Clerkship Director or Department Chair).

(Link to faculty advisor guide)

Your official advisor may be your main source of advice but do not let that stop you from filling in the gaps by

talking with many other faculty. Students who have had difficulty with the match have typically not connected with

a good advisor.

Advisors and Letters of Recommendation

Your advisor is someone you should be able to talk with candidly. You should feel comfortable bringing up your

doubts, fears, career decision angst, weaknesses as well as triumphs. Some students have their advisor also prepare a

letter of recommendation; though some students choose to have other faculty write their letters (you will need three

letters of recommendation in total).

Mechanics of Selecting an Advisor

While you cannot formally choose an advisor yet, there is great benefit in starting to think about advisors and

meeting with potential advisors early. We will provide you with an updated list of advisors in each department. Ask

the fourth year students who the really good advisors are! Talk with as many attendings and consultants as you can.

The major reason you are not permitted to choose an advisor until February is that up to that time they are still very

involved with their 4th year advisees. Your advisor will also work with you on refining your fourth year schedule.

Guide to the Transition to Advanced Clinical Practice | 17

Applying for Residency

How do programs select residents?

There is little question that program directors look at your performance in medical school as the prime

consideration. Grades, your letters of recommendation, what you say about yourself in your application and/or

personal statement, your research experience, your community service, and extracurricular activities are all

important. Most programs look at National Board scores. For most programs, the most important factor is their

assessment of your stability, reliability, and teachability through your academic record, letters of recommendation,

and the interview.

For more information about what factors program directors consider important in considering an applicant, review

the results of the NRMP Program Director Survey. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/PD-

Survey-Report-2022_FINALrev.pdf

How to decide and where to apply

Types of Hospitals

There are numerous ways of classifying hospitals. In general, the primary training hospital of an academic medical

center (e.g., the GW University Hospital) often is very different from one not on the main campus. Some

unaffiliated hospitals may be community-based and vary in their focus on education.

If there is a possibility that you will be considering postgraduate training in the form of specialty fellowships, post-

doctoral research fellowships, etc., you are more likely to be accepted to these programs if your residency was done

in a university-based training program, less likely in an affiliated hospital, least likely from an unaffiliated program.

(There are, however, certainly exceptions to this rule.) Accordingly, many seniors consider seeking university-based

programs as a means of keeping their options open. This fact tends to make these programs more competitive than

others.

Another basis for classifying hospitals is the public versus private continuum. While there can be great educational

emphasis in both public and private institutions, the major difference between these is the degree of responsibility

given directly to residents and the (often inversely related) quality of support services. At private hospitals, the final

word is always in the hands of the private physicians who admitted the patient. At public hospitals, while there is

always an attending responsible, care and management decisions are usually considered by the residents and then

checked and confirmed with the attending. In these situations, residents usually feel more responsible for decisions.

Programs with very strong fellowship programs and programs in hospitals that segregate patients by specialty

(thereby allowing a stronger presence of specialty fellows) tend to keep their early trainees in less critical roles.

Responsibility and opportunity to make decisions is available to trainees at these hospitals later in their postgraduate

training. For some, this is ideal; for others, it is at best an annoyance, and sometimes a significant hindrance to

learning.

Private institutions generally have more of the amenities, whereas public institutions often are more barebones.

Your own experiences at places like Holy Cross versus the V.A. Hospital, will likely give you some sense of this.

Location

It will come as no surprise that some areas of the country are considered more desirable than others! Because

competition is stiffer in geographically desirable locations, you are more likely to match at a better quality residency

in a less popular location. Also, as increasing numbers of physicians locate in highly desirable locations, finding jobs

in those areas can be difficult. Past studies have shown that 70 percent of physicians practice within a one-hundred

mile radius of the hospital in which they did their last years of residency training. If you are interested in doing a

Guide to the Transition to Advanced Clinical Practice | 18

residency and settling in a desirable location (e.g., states of California, Washington, Oregon; cities of New York and

Boston), you have a good chance of doing so (our students from California in particular have been doing well

matching to West Coast programs). However, you may have an even better chance in some of the superb

institutions of the south and the midwest. We urge you to test the waters.

Duration of Training

Two or three states allow a physician to be licensed to practice after graduation; most require a minimum of one

year of postgraduate training. Virtually no U.S. physicians follow these pathways. Most do at least three years of

training. When you match into a categorical residency program, the program expects that you will complete their

entire curriculum. For instance, if you are an applicant to a pediatrics training program, the program assumes you

are applying for year one, but will stay on for years two and three. NRMP matches you in a legally binding manner

for your first year. Unless you and the program have a major issue, you will be offered a contract for Year 2 usually

around November.

How do you know if you are competitive?

You need to consider two components: 1) How competitive is the specialty to which I am applying? 2) How do I

stack-up against the other applicants? There is considerable variation in competitiveness between specialties. A

useful technique to assess this is to look at the percentage of applicants who matched to a specific specialty. The

chart in the appendix shows the percentages of U.S. seniors and independent applicants who matched to their

preference specialty.

For a comprehensive look at the NRMP match results you may review the AAMC publication, Charting Outcomes

in the Match: Characteristics of Applicants Who Matched to their Preferred Specialty in the 2023 NRMP Main

Residency Match.

Once you are committed to a specialty, how do you evaluate your competitiveness within the field? In general,

advisors’ recommendations and thoughts can give you some sense of your level of competitiveness. The better

advisors are pretty good at predicting where students are safe.

A more general way of assessing competitiveness is to look at the current residents of each program. How many are

members of Alpha Omega Alpha, the medical honor society? How many are foreign trained? How many of our

students have been accepted to that program in recent years? How are the GW alumni, who have worked in that

hospital, perceived?

If you happen to do an elective at an outside hospital, evaluate the competence of the interns (and other fourth-year

students). Our students usually come back feeling at least as competent as their peers from other schools, if not

more so. It is of note, however, that many seniors do not match to programs they felt comfortable in when they

took an elective there.

You will also have access to the Texas STAR database that includes self-reported student data from most medical

schools in the country for the past several years. This database has a lot of data (that can be overwhelming at times),

but it’s handy to see where applicants similar to you got interviews and where they eventually matched. Don’t forget

to pay it forward by completing the Texas STAR Match Survey on Match Day to provide data for your little sibs.

More Information on Competitiveness – Grouped by Specialty

Medicine Programs

Guide to the Transition to Advanced Clinical Practice | 19

There is a wide range of competitiveness in medicine programs and a large number of good programs available.

Larger programs, especially those affiliated with medical centers, are commonly offering two separate tracks

within the Department of Medicine: one for people who plan a subspecialty career in medicine or who at least

want some subspecialty training, and the other (by cooperating with other departments) in a more general or

primary care program with more experience in ambulatory internal medicine practice. Many medicine programs

also offer a preliminary as well as a complete categorical program. In the complete program, the expectation is

that if you do a reasonable job, you will stay on and complete your three years of training in that program. If

you select a preliminary program, the program makes a commitment to you for only one year. If you do well,

many programs will try to make room for you for the second year. For some of you who have a strong interest

in a particular hospital, you may want to consider applying to both their three-year program, and, to increase

your chances, to their one-year program as well. In outstanding hospitals, one year programs may not fill, while

the 3 year programs almost always fill. Due to recent changes in medicine and the support for postgraduate

training some programs are cutting back on preliminary positions, making these programs more competitive.

Medicine programs use the NRMP to match applicants.

Pediatrics Programs

Pediatrics is a 3 year residency and has historically had a favorable match rate for students. GW graduates have

done very well. Virtually all of our pediatric applicants match, if they complete their rank list reasonably.

Pediatrics programs use the NRMP to match applicants. There are some programs that have special tracks in

addition to categorical tracks, like those that are focused on community health or advocacy/social justice,

primary care, or research. When discussing with your advisor, consider your interests in free standing children’s

hospitals, academic pediatrics or community programs, geography, and intern class size, in addition to special

features (i.e. global health, advocacy, medical education, research, etc).

Medicine/Pediatrics and Other Combined Programs

A growing phenomenon is the emergence of combined programs. The oldest is Medicine/Pediatrics (a 4 year,

double board eligible program). These are of interest to those who want a broad age spectrum of patients, and

who don’t want to do OB and surgery (i.e. family practice). Because all the combination programs are relatively

new and small in number, there are only a few advisors who know much about these options. There are several

faculty members in pediatrics who trained at med-peds programs. Otherwise, you will need to talk to one of the

deans and other advisors in individual specialty areas to discuss whether a combined program is right for your

needs. To get more information, you might call a couple of programs and talk with a few residents.

Other combined programs include: Medicine-Emergency Medicine, Medicine- Family Practice, Medicine-

Neurology, Medicine-PM&R, Medicine-Preventive Medicine, Medicine-Psychiatry, Pediatrics-Emergency

Medicine, Pediatrics-PM&R, Pediatrics- Psychiatry-Child Psychiatry, Psychiatry-Child Psychiatry, Psychiatry-

Family Practice, and Psychiatry-Neurology. Most of these combined programs use the NRMP to match

applicants.

Family Medicine Programs

Family medicine has been a specialty for many decades. It is a reasonably popular choice for American medical

school graduates (about 10% of whom choose FP for their PGY-1 program). A general theme in family

medicine selection seems to be “How do we know that you really want to be a family practitioner?” In the past,

many of our students have felt at a disadvantage answering such questions because we don’t have a Department

of Family Medicine (although now we do have a division of family medicine under the Department of

Emergency Medicine.) It is reasonable to point out to interviewers, that GW was one of the first medical

schools to require an ambulatory (primary care) clerkship for all students during the third year when students

still have some career flexibility. Many of you worked with family practitioners while on that rotation. For those

who didn’t, many programs would like to see that an applicant has done a clerkship with a family practitioner or

in an established family medicine program. Your advisor or one of the deans should be of assistance in helping

you decide if you want to do a clerkship off-campus. Dr. Andrea Anderson serves as the main family medicine

advisor for our students. Many of the established family medicine programs are becoming traditional: They are

increasingly looking more heavily at grades, board scores, and the like. Generally, however, family medicine

Guide to the Transition to Advanced Clinical Practice | 20

programs place very great emphasis on the kind of person you are, your aspirations, your experience working in

more rural or underserved environments, and where you intend to practice. The style and “interviewability” of

the applicant appear to be very important to most FM programs. Family Medicine programs use the NRMP to

match applicants.

Psychiatry Programs

Psychiatry has seen a greater than 10% increase in the number of matched applicants from 2015-2019. Given

the recent national level push towards population health and integrated health care have increased the interest in

this field. Psychiatry is now considered a moderately completive field with a 99% program fill rate over the past

two years. This fill rate is higher than pediatrics, internal medicine, and anesthesiology. Many applicants have

good traditional academic metrics, so students who have shown a sustained interest in mental health care are

particularly sought out by psychiatric residency program directors. Historically our students have always done

well in psychiatry, frequently matching to some of the most popular training programs. Psychiatry programs

match via the NRMP system.

Obstetrics/Gynecology Programs

Obstetrics and Gynecology has historically been a moderately to highly competitive field. Our Department of

Obstetrics has an aggressive and very successful approach to getting our graduates matched into good

programs. In this department particularly, it is imperative that you keep the department well informed of your

interests. Obstetrics/Gynecology programs use the NRMP to match applicants.

Surgery and Surgical Subspecialties

General surgery is usually a five-year or six-year program and has become increasingly more competitive over

the past years.

Most of the surgical subspecialty programs allow you to apply via NRMP for Year-1 and automatically track into

your final destination. Other programs require that you find your first one or two years of general surgical

training, but simultaneously (as seniors in medical school) complete applications for your subspecialty surgical

training program as well. A large percentage of orthopedic, urology, neurosurgery, plastics, and ENT programs

have joined with the general surgery programs in their institutions to form a complete program. Matching to

such a program will guarantee the first one or, in some situations, two years of general surgical training prior to

the essentially automatic admission to that department’s surgical specialty training program. Ophthalmology

programs almost always require you to find your preliminary year separately through the NRMP process.

There is an independent (non-NRMP) match that handles the ophthalmology match. The urologists have yet

another match for candidates who intend to start urology training. You can go to the

https://www.sfmatch.org/ (ophthalmology) or the https://www.auanet.org/education/urology-and- specialty-

matches.cfm (urology) web sites for full information and registration information about these matches.

Right now orthopedics, urology, neurosurgery, ophthalmology, dermatology, otolaryngology, and plastic surgery

are VERY competitive. If you are considering one of these specialties you should meet with that department

early and realistically assess your chances. Any student who has not done truly outstanding work thus far must

consider some type of back-up plan.

Emergency Medicine Programs

EM programs match via NRMP for either complete (three or four years) or advanced (PGY-2 placement)

programs. Review the web site at SAEM.org and click on the “medical student section” for more information.

Your advisor can help you choose among the program options for a best fit. EM is moderately competitive, so

be sure to coordinate carefully with your advisor to maximize your chances of matching.

Radiology Programs

Radiology is an average competitive specialty. In most cases you will have to match to your preliminary year

separately from the Radiology program. Radiology programs use the NRMP to match applicants.

Guide to the Transition to Advanced Clinical Practice | 21

Dermatology Programs

Those of you interested in dermatology will need to match for your PGY2 position and a preliminary year.

Dermatology remains the most highly competitive field, nearly a quarter of all applicants go unmatched to a

position each year. Every student interested in dermatology should consider a back-up plan. Dermatology

programs use the NRMP to match applicants.

Anesthesiology Programs

In the past several years, GW students have done extremely well in the anesthesiology match. However, this

specialty has become more competitive recently. Most programs require a preliminary/ transitional year before

the anesthesiology residency and some programs include this year as part of the categorical program. You will

be applying to both through the NRMP match.

Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Programs

This is a field that is becoming more attractive every year, and GW students have done very well in this match.

PM&R programs use the NRMP to match applicants.

Competitiveness: Strategies to Protect Yourself

Competing for residencies in competitive fields is obviously difficult; nonetheless, GW students have a fine track

record: most of our students in the Military Scholarship programs get their first or second choice of training site and

‘path’ (e.g. categorical military training, preliminary military training followed by GMO service, or civilian

deferments (deferments tend to be much less predictable, but many of our students who have requested deferments

have been successful). Our students applying in ‘early’ match specialties have also done well; although a number of

less competitive students fail to match in some of these specialties almost every year. Overall, from year to year only

about 3-6% of GW seniors fail to match to a residency program.

Those of you applying to the more competitive specialties (orthopedics, otolaryngology, urology, ophthalmology,

plastics, neurosurgery, and dermatology) must exercise great caution. The first question you need to ask is, “How

much do I want this field?” If you are convinced only “x” will satisfy you, then you absolutely should give it a try.

However, if you see attractions in other areas, we suggest you look at them again, and carefully.

Students applying to such highly competitive specialties must carefully consider back up plans regardless of the

strength of their academic records. Students with average or weak academic records absolutely must have a firm and

rational back-up plan in the event that they go unmatched. Viable back-up plans include:

Applying to one or more alternative specialties

Applying to preliminary positions in surgery or medicine (although preliminary programs are becoming

more competitive especially in medicine)

Taking a year off after graduation and reapplying

Taking a year off between third and fourth year to do research in the specialty area you are considering

All these strategies have advantages and disadvantages, and you should carefully discuss them with your faculty

advisors and with the deans.

The Application Process

Settling on a group of residency programs that you would like to apply to is a complicated but achievable goal.

However, it will require a lot of “leg work” on your part. Unfortunately, there is no single resource that attempts to

describe individual residency programs or compare their quality or competitiveness. This will be frustrating to many

of you. You will need to access as many resources as possible to find out about programs. Although many programs

sustain their reputations for quality training and competitiveness from year to year, as you may expect, many

programs will fluctuate quite widely in these characteristics over even relatively short time spans.

Guide to the Transition to Advanced Clinical Practice | 22

For instance, changes in the residency director or other key faculty can raise or lower a residency program’s status

very dramatically overnight! In addition, changes in the nature of the hospital(s) or ambulatory training facilities

affiliated with each program may affect the quality of the program significantly [particularly in these days of rapid

and unpredictable change in health care. Consequently, what a recent graduate or faculty member may “know”

about a program could become inaccurate very quickly. In addition, faculty that have spent a great deal of time at

GW (and those who did their residency training more years ago than they would like to admit!) may have very

limited insight into the current status of any particular training program. You will need to ask around quite a bit to

find faculty who may be knowledgeable about residencies outside of the immediate Washington, DC area or their

own residency training program. Here are a few quick tips for identifying residency training programs:

Pick a specialty (or maybe more than on if you are still deciding!)

Pick some geographic regions in which you think you might like (or need!) to be.

Warning: Those of you applying to very competitive specialties should not be too picky about geography;

you will need to apply broadly! Regardless of your specialty choice, very narrow geographic preferences (like

“I have to be in Washington, DC”) are extremely risky and are the source of many of our recent matching

failures. Unless you are among the most outstanding members of the class, you’d better consider more than

a single very isolated geographic area. The application process isn’t the time to be picky. You can always

turn down an interview if offered.

Make a list of potential programs in those geographic areas using FREIDA

Narrow your list. This is the hardest part, but here are some suggestions:

1. How competitive are you as an applicant? (ask your advisor(s), or one of the deans)

2. What kind of program do you want (university, university-affiliate, community)?

3. What kind of program are you competitive at (the answer to this question may or not be the same as

your answer to the prior question, and will vary by specialty choice)?

4. Visit program websites for detailed information

5. Check to determine if we have any recent graduates at the programs you are considering (see Appendix)

6. Determine if we have any faculty members who trained or served as faculty at any of the programs (this

requires you asking around).

7. Do an audition rotation at the program (an away elective, usually set up in the spring or summer of your

third year)

The Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS)

ERAS is an application service that is run by the Association of American Medical Colleges. Except for early match

programs, virtually all specialties use ERAS.

ERAS makes your life immeasurably easier. Through this system everything related to the application process is

done online. Next summer, those of you using ERAS will receive all the necessary instructions. You will complete

your application online, and designate letters of recommendation that are to be sent to programs. Your letter of

recommendation writers will upload their letters directly into ERAS. The Dean’s office will upload your transcript

and your MSPE into ERAS.