THE EFFECTS OF GENRE AND MODE IN COMPUTER GAMES FOR

ENGLISH LANGUAGE LEARNING

A THESIS SUBMITTED TO

THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES

OF

MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY

BY

MEHMET EMRE ALTINBAŞ

IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS

FOR

THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY

IN

THE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE TEACHING

JULY 2023

Approval of the thesis:

THE EFFECTS OF GENRE AND MODE IN COMPUTER GAMES FOR

ENGLISH LANGUAGE LEARNING

submitted by MEHMET EMRE ALTINBAŞ in partial fulfillment of the

requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Language Teaching,

the Graduate School of Social Sciences of Middle East Technical University by,

Prof. Dr. Sadettin KİRAZCI

Dean

Graduate School of Social Sciences

Prof. Dr. Nurten BİRLİK

Head of Department

Department of Foreign Language Education

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Perihan SAVAŞ

Supervisor

Department of Foreign Language Education

Examining Committee Members:

Prof. Dr. Arif ALTUN (Head of the Examining Committee)

Hacettepe University

Department of Computer Education and Instructional Technology

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Perihan SAVAŞ (Supervisor)

Middle East Technical University

Department of Foreign Language Education

Prof. Dr. Çiler HATİPOĞLU

Middle East Technical University

Department of Foreign Language Education

Assist. Prof. Dr. Necmi AKŞİT

İ. D. Bilkent University

Department of Foreign Language Education

Assist. Prof. Dr. Tijen AKŞİT

İ. D. Bilkent University

Department of Foreign Language Education

iii

I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and

presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare

that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all

material and results that are not original to this work.

Name, Last Name: Mehmet Emre ALTINBAŞ

Signature:

iv

ABSTRACT

THE EFFECTS OF GENRE AND MODE IN COMPUTER GAMES FOR

ENGLISH LANGUAGE LEARNING

ALTINBAŞ, Mehmet Emre

Ph.D., Department of English Language Teaching

Supervisor: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Perihan SAVAŞ

July 2023, 317 pages

The present study aimed to uncover whether there is a significant difference

across and within computer games with different modes and genres in terms of target

language learning. To this end, a sequential explanatory mixed-method research

design was used. Initially, a questionnaire was implemented with a group of gamer

learners of English experienced in major game modes and genres to find out about the

perceived frequency of learning and practicing target language knowledge and skills

in these games. Following this, observations of game streams from each game mode

and genre combination were carried out to uncover the activities of language practicing

with their durations and frequencies. Finally, interviews were carried out with

participants specifically interested in certain game mode and genre combinations to

understand their opinions about language learning in these games. The findings show

that there are significant differences across and within different game modes and

genres with regard to language learning, along with certain similarities. Gamer

language learners are involved in distinct activities in these game modes and genres

with varying frequencies and durations. They experience specific opportunities and

challenges, and they have certain recommendations and expectations for the

improvement of language learning in different game modes and genres. Based on the

v

findings, the study presents a comprehensive overview of learning and practicing

target language knowledge and skills in different game modes and genres and

identifies optimal game mode and genre combinations for learning and practicing

specific target language knowledge and skills for academic and practical interests.

Keywords: Computer Games, Game Modes, Game Genres, Learning English as a

Foreign Language

vi

ÖZ

BİLGİSAYAR OYUNLARINDA MOD VE TÜRÜN İNGİLİZ DİLİ ÖĞRENİMİ

İÇİN ETKİLERİ

ALTINBAŞ, Mehmet Emre

Doktora, İngiliz Dili Öğretimi Bölümü

Tez Yöneticisi, Doç. Dr. Perihan SAVAŞ

Temmuz 2023, 317 sayfa

Mevcut çalışma farklı modlara ve türlere sahip bilgisayar oyunlarının

içerisinde ve arasında dil öğrenimi açısından önemli bir fark olup olmadığını ortaya

çıkarmayı hedeflemiştir. Bu doğrultuda açımlayıcı sıralı karma araştırma deseni

kullanılmıştır. Öncelikle ana oyun modları ve türlerinde deneyimli İngilizce

öğrencileri ile farklı oyun modu ve türlerinde algılanan hedef dil bilgileri ve

becerilerinin öğrenilme ve uygulanma sıklığını bulmak amacıyla bir anket

uygulanmıştır. Sonrasında her bir oyun modu ve türünde gerçekleşen dil kullanımı

aktivitelerini sıklıkları ve süreleri ile ortaya çıkarmak adına oyun yayını gözlemleri

yapılmıştır. Son olarak, belirli oyun modu ve türlerine özellikle ilgi duyan katılımcılar

ile farklı oyun modu ve türlerinde yabancı dil öğrenimine dair görüşlerini öğrenmek

adına görüşmeler gerçekleştirilmiştir. Bulgular belirli benzerliklerin yanı sıra farklı

oyun modları ve türlerinin içerisinde ve arasında dil öğrenimi açısından önemli

farklılıklar olduğunu ortaya koymuştur. Oyuncu dil öğrencileri bu oyun modları ve

türlerinde değişen sıklıkta ve sürelerde farklı aktivitelerde bulunmaktadırlar. Farklı

oyun modu ve türlerinde değişik imkanlar ve zorluklar deneyimlemekteler ve bu oyun

modu ve türlerinde dil öğreniminin artırılması için belirli önerilere ve beklentilere

sahipler. Çalışma bu sonuçlara dayalı olarak farklı oyun modlarında ve türlerinde dil

öğrenimine yönelik kapsamlı bir genel bakış sunmakla beraber akademik ve pratik

vii

ilgiler doğrultusunda belirli hedef dil bilgisi ve becerilerinin öğrenilmesi ve

uygulamaya dökülmesi konusunda optimal oyun modu ve türü kombinasyonları

belirlemektedir.

Anahtar Kelimeler: Bilgisayar Oyunları, Oyun Modları, Oyun Türleri, Yabancı Dil

Olarak İngilizce Öğrenimi

viii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to express my gratitude to several people for their valuable

contributions to me throughout my doctoral journey. Their invaluable contributions

have made this incredible journey more effective and enjoyable for me.

First of all, I would like to start with expressing how grateful I am to my

supervisor Assoc. Prof. Dr. Perihan Savaş for guiding me in my doctoral studies.

Without her support, my doctoral education and this study wouldn’t be complete. She

has always encouraged me to pursue my interests and helped me become a better

researcher.

I would also like to give special thanks to the monitoring committee members

Prof. Dr. Arif Altun and Prof. Dr. Çiler Hatipoğlu for their insightful contributions and

feedback during the various stages of the dissertation. Their valuable suggestions and

helpful feedback have enabled this study to become better throughout the process. I

would also like to express my heartfelt thanks to examining committee members

Assist. Prof. Dr. Necmi Akşit and Assist. Prof. Dr. Tijen Akşit for their invaluable

suggestions for the improvement of the study. They generously provided their

knowledge and expertise for the improvement of the study.

My heartfelt thanks are also to the professors whose courses I have taken at the

beginning of my doctoral studies. I am grateful to Prof. Dr. Ayşegül Daloğlu, Prof. Dr.

Hüsnü Enginarlar, Prof. Dr. Nurdan Gürbüz, Assoc. Prof. Dr. Duygu Sarısoy and Dr.

Deniz Şallı Çopur for all the precious learning experience they provided in their

classes. I always enjoyed attending their classes. I should also offer my thanks to my

classmates in all the courses I have taken in the program. I learned a lot from my

classmates in our discussions and reflections during classes. In addition to this, we had

a great time both in and out of lessons. I am grateful for all the valuable time we have

spent together.

I would also like to thank the Scientific and Technological Research Council

of Turkey (TÜBİTAK) for supporting my doctoral studies.

Lastly, my deepest thanks are for my dear wife, Fadime. Her endless support

to me throughout my doctoral studies, just like in all parts of my life, has given me

ix

hope and strength, as always. I wouldn’t have been able to complete my studies

without her loving presence by my side.

x

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PLAGIARISM ........................................................................................................... iii

ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................ iv

ÖZ ................................................................................................................................ vi

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...................................................................................... viii

TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................. x

LIST OF TABLES ................................................................................................... xvii

LIST OF FIGURES ................................................................................................... xix

INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 1

1.0. Presentation ................................................................................................... 1

1.1. Theoretical Background .................................................................................... 1

1.2. Operational Concepts Related to English Language Learning within the

Present Study ............................................................................................................ 6

1.3. The Need for the Study ...................................................................................... 8

1.4. Significance of the Study ................................................................................. 13

1.5. Research Questions.......................................................................................... 15

LITERATURE REVIEW ........................................................................................... 17

2.0. Presentation ..................................................................................................... 17

2.1. Computer Assisted Language Learning .......................................................... 17

2.2. Commercial Computer Games and Learning Target Language Vocabulary .. 24

2.3. Commercial Computer Games and Learning Target Language Grammar ...... 35

2.4. Commercial Computer Games and Improving Target Language Skills ......... 39

METHODOLOGY ..................................................................................................... 49

3.0. Presentation ..................................................................................................... 49

3.1. Overview of the Methodology ......................................................................... 49

CHAPTERS

xi

3.1. Participants ...................................................................................................... 50

3.2. Data Collection Tools and Procedure .............................................................. 56

3.2.1 Questionnaire ............................................................................................. 57

3.2.2. Observation ............................................................................................... 60

3.2.2. Interview ................................................................................................... 69

3.3. Data Analysis .................................................................................................. 71

3.3.1. Analysis of the Questionnaire ................................................................... 73

3.3.2 Analysis of the Observations ..................................................................... 74

3.3.3. Analysis of the Interviews ........................................................................ 75

FINDINGS ................................................................................................................. 77

4.0. Presentation ..................................................................................................... 77

4.1. Comparison of Single-player and Multiplayer Game Modes.......................... 77

4.1.1. Overall Findings of the Comparison of Single-player and

Multiplayer Game Modes .............................................................................. 79

4.1.2. Comparison of Single-player and Multiplayer Game Modes Based

on Vocabulary Learning ................................................................................. 79

4.1.3. Comparison of Single-player and Multiplayer Game Modes Based

on Grammar Learning .................................................................................... 80

4.1.4. Comparison of Single-player and Multiplayer Game Modes Based

on Reading Practice........................................................................................ 81

4.1.5. Comparison of Single-player and Multiplayer Game Modes Based

on Listening Practice ...................................................................................... 82

4.1.6. Comparison of Single-player and Multiplayer Game Modes Based

on Writing Practice ........................................................................................ 83

4.1.7. Comparison of Single-player and Multiplayer Game Modes Based

on Speaking Practice ...................................................................................... 84

4.2. Comparison of the Genres Based on Target Language Knowledge and

Skills ....................................................................................................................... 85

xii

4.2.1. Overall Findings of the Comparison of the Genres Based on Target

Language Knowledge and Skills .................................................................... 86

4.2.2. Comparison of the Genres Based on the Frequency of Vocabulary

Learning ......................................................................................................... 87

4.2.3. Comparison of the Genres Based on the Frequency of Grammar

Learning ......................................................................................................... 88

4.2.4. Comparison of the Genres Based on the Frequency of Reading

Practice ........................................................................................................... 89

4.2.5. Comparison of the Genres Based on the Frequency of Listening

Practice ........................................................................................................... 90

4.2.6. Comparison of the Genres Based on the Frequency of Writing

Practice ........................................................................................................... 91

4.2.7. Comparison of the Genres Based on the Frequency of Speaking

Practice ........................................................................................................... 92

4.3. Comparison of the Target Language Knowledge and Skill Types within

Each Genre ............................................................................................................. 93

4.3.1. Overall Findings of the Comparison of the Target Language

Knowledge and Skill Types Based on Each Genre ........................................ 94

4.3.2. Comparison of the Target Language Knowledge and Skill Types

Based on Action Genre .................................................................................. 95

4.3.3. Comparison of the Target Language Knowledge and Skill Types

Based on Adventure Genre ............................................................................ 97

4.3.4. Comparison of the Target Language Knowledge and Skill Types

Based on Role-playing Genre ........................................................................ 99

4.3.5. Comparison of the Target Language Knowledge and Skill Types

Based on Strategy Genre .............................................................................. 101

4.3.6. Comparison of the Target Language Knowledge and Skill Types

Based on Simulation Genre .......................................................................... 103

4.4. Activities of Language Practicing Observed in Different Computer Game

Modes and Genres ................................................................................................ 106

xiii

4.4.1. Overview of the Activities of Language Practicing in the Light of

Game Mode Comparison .................................................................................. 106

4.4.2. Overview of the Activities of Language Practicing in the Light of

Game Genre Comparison.................................................................................. 107

4.4.3. Overview of the Activities of Language Practicing in the Light of

Language Skills Comparison ............................................................................ 108

4.4.4. Activities of Language Practicing Observed in Different Game Modes

and Genres ........................................................................................................ 111

4.4.4.1. Types of Language Practicing Observed in Action Games ............ 112

4.4.4.2. Types of Language Practicing Observed in Adventure Games ...... 118

4.4.4.3. Types of Language Practicing Observed in Role-playing Games .. 126

4.4.4.4. Types of Language Practicing Observed in Strategy Games .......... 133

4.4.4.5. Types of Language Practicing Observed in Simulation Games ..... 139

4.5. Opinions of Gamer Learners of English Regarding Language Learning in

Different Game Modes and Genres ...................................................................... 141

4.5.1. Overview of Interview Findings ............................................................. 141

4.5.2. Opportunities Provided by Computer Games for Language Learning ... 144

4.5.3. Limitations of Computer Games for Language Learning ....................... 148

4.5.4. Ways of language Learning and Practicing in Computer Games ........... 151

4.5.5. Opinions about the Previous Findings of the Study ............................... 165

4.5.6. Suggestions for Gamer Language Learners ............................................ 170

4.5.7. Expectations of Gamer Language Learners from Computer Games ...... 173

DISCUSSION .......................................................................................................... 176

5.0. Presentation ................................................................................................... 176

5.1. Overview of the Findings .............................................................................. 176

5.2. An Overview for Language Learning and Practicing in Different Game

Modes and Genres ................................................................................................ 179

5.2.1. Single-player Action Games ................................................................... 187

xiv

5.2.2. Multiplayer Action Games ...................................................................... 188

5.2.3. Single-player Adventure Games ............................................................. 191

5.2.4. Multiplayer Adventure Games ................................................................ 192

5.2.5. Single-player Role-playing Games ......................................................... 194

5.2.6. Multiplayer Role-playing Games ............................................................ 196

5.2.7. Single-player Strategy Games ................................................................. 199

5.2.8. Multiplayer Strategy Games ................................................................... 201

5.2.9. Single-player Simulation Games ............................................................ 203

5.2.10. Multiplayer Simulation Games ............................................................. 204

5.3. A Guide for Optimal Game Mode and Genre Combinations in Learning

and Practicing Specific Target Language Knowledge and Skills Based on the

Findings ................................................................................................................ 207

5.3.1. Vocabulary Learning .............................................................................. 209

5.3.2. Grammar Learning .................................................................................. 211

5.3.3. Reading Practice ..................................................................................... 213

5.3.4. Listening Practice .................................................................................... 216

5.3.5. Writing Practice ...................................................................................... 219

5.3.6. Speaking Practice .................................................................................... 221

5.4. Discussion of the Findings in View of Existing Literature ........................... 223

5.4.1. Discussion of the Findings Related to Game Mode Comparison in

View of Existing Literature .............................................................................. 223

5.4.2. Discussion of the Findings Related to Genre Comparison in View of

Existing Literature ............................................................................................ 227

5.4.3. Discussion of the Findings Related to Target Language Knowledge

and Skills Comparison in View of Existing Literature ..................................... 232

5.4.4. Discussion of the Findings Related to Activities of Target Language

Learning and Practicing in View of Existing Literature ................................... 233

5.4.5. Discussion of the Findings Related to the Opinions of Gamers on

Computer Games and Language Learning in View of Existing Literature ...... 236

xv

5.5. Implications for Research .............................................................................. 238

5.5.1. Implications for Research Based on Game Mode Comparison .............. 238

5.5.2. Implications for Research Based on Genre Comparison ........................ 240

5.5.3. Implications for Research Based on Target Language Knowledge and

Skills Comparison ............................................................................................. 243

5.5.4. Implications for Research Based on Activities of Target Language

Learning and Practicing .................................................................................... 244

5.5.5. Implications for Research Based on the Opinions of Gamers on

Computer Games and Language Learning ....................................................... 246

5.6. Implications for Practice................................................................................ 248

5.6.1. Implications on Game Mode Comparison for Practice .......................... 248

5.6.2. Implications on Genre Comparison for Practice .................................... 249

5.6.3. Implications on Target Language Knowledge and Skills Comparison

for Practice ........................................................................................................ 252

5.6.4. Implications on Activities of Language Learning and Practicing for

Practice.............................................................................................................. 254

5.6.5. Implications on the Opinions of Gamers on Computer Games and

Language Learning for Practice ........................................................................ 256

5.7. Limitations and Suggestions for Further Research ....................................... 259

5.7.1. Limitations and Suggestions for Further Research Related to Game

Mode Comparison............................................................................................. 259

5.7.2. Limitations and Suggestions for Further Research Related to Genre

Comparison ....................................................................................................... 260

5.7.3. Limitations and Suggestions for Further Research Related to Target

Language Knowledge and Skills Comparison .................................................. 261

5.7.4. Limitations and Suggestions for Further Research Related to Activities

of Target Language Learning and Practicing ................................................... 262

5.7.5. Limitations and Suggestions for Further Research Related to Opinions

of Gamers on Computer Games and Language Learning ................................. 263

xvi

REFERENCES ......................................................................................................... 265

APPENDICES

A. QUESTIONNAIRE ............................................................................................. 277

B. STREAM OBSERVATION FORM ................................................................... 284

C. SEMI-STRUCTURED INTERVIEW QUESTIONS .......................................... 285

D. LIST OF CODES, CATEGORIES AND THEMES OF THE INTERVIEW ..... 286

E. APPROVAL OF THE HUMAN SUBJECTS ETHICS COMMITTEE ............. 294

F. CURRICULUM VITAE ...................................................................................... 295

G. TURKISH SUMMARY / TÜRKÇE ÖZET ........................................................ 298

H. THESIS PERMISSION FORM / TEZ İZİN FORMU ........................................ 317

xvii

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1 An overview of participants’ demographic information .............................. 52

Table 2 Overview of interview participants .............................................................. 70

Table 3 Summary of the research questions, data collection tools and data

analysis techniques ..................................................................................................... 72

Table 4 Significance of pairwise comparisons based on action genre (column

oriented) ..................................................................................................................... 96

Table 5 Significance of pairwise comparisons based on adventure genre (column

oriented) ..................................................................................................................... 98

Table 6 Significance of pairwise comparisons based on role-playing genre

(column oriented) ..................................................................................................... 101

Table 7 Significance of pairwise comparisons based on strategy genre (column

oriented) ................................................................................................................... 103

Table 8 Significance of pairwise comparisons based on simulation genre

(column oriented) ..................................................................................................... 105

Table 9 Instances of language practicing observed in the single-player action

game ......................................................................................................................... 113

Table 10 Instances of language practicing observed in the multiplayer action

game ......................................................................................................................... 115

Table 11 Instances of language practicing observed in the single-player adventure

game ......................................................................................................................... 119

Table 12 Instances of language practicing observed in the multiplayer adventure

game ......................................................................................................................... 122

Table 13 Instances of language practicing observed in the single-player

role-playing game..................................................................................................... 127

Table 14 Instances of language practicing observed in the multiplayer

role-playing game..................................................................................................... 130

Table 15 Instances of language practicing observed in the single-player strategy

game ......................................................................................................................... 134

Table 16 Instances of language practicing observed in the multiplayer strategy

game ......................................................................................................................... 136

xviii

Table 17 Instances of language practicing observed in the single-player

simulation game ....................................................................................................... 139

Table 18 Instances of language practicing observed in the single-player

simulation game ....................................................................................................... 140

Table 19 An overview of language learning in different game modes and genres

based on the findings ................................................................................................ 181

xix

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1 Overview of the procedure ......................................................................... 51

Figure 2 Call of Duty: Modern Warfare.................................................................... 62

Figure 3 Counter Strike: Global Offensive ............................................................... 63

Figure 4 The Walking Dead ...................................................................................... 64

Figure 5 Minecraft ..................................................................................................... 64

Figure 6 The Witcher 3: The Wild Hunt ................................................................... 65

Figure 7 World of Warcraft ....................................................................................... 66

Figure 8 Age of Empires II: Definitive Edition ........................................................ 67

Figure 9 League of Legends ...................................................................................... 67

Figure 10 Euro Truck Simulator 2 ............................................................................ 68

Figure 11 FIFA 22 ..................................................................................................... 68

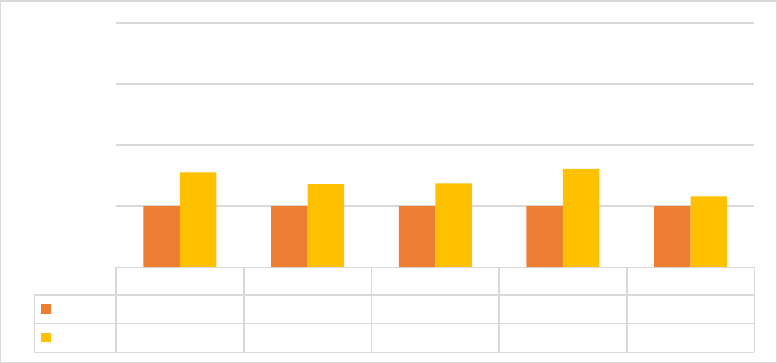

Figure 12 Comparison of single-player and multiplayer game modes in terms of

overall vocabulary learning frequency ....................................................................... 80

Figure 13 Comparison of single-player and multiplayer game modes in terms of

overall grammar learning frequency .......................................................................... 81

Figure 14 Comparison of single-player and multiplayer game modes in terms of

reading practice frequency ......................................................................................... 82

Figure 15 Comparison of single-player and multiplayer game modes in terms of

listening practice frequency ....................................................................................... 83

Figure 16 Comparison of single-player and multiplayer game modes in terms of

writing practice frequency.......................................................................................... 84

Figure 17 Comparison of single-player and multiplayer game modes in terms of

speaking practice frequency ....................................................................................... 85

Figure 18 Comparison of the genres based on overall vocabulary learning

frequency .................................................................................................................... 87

Figure 19 Comparison of the genres based on overall grammar learning

frequency .................................................................................................................... 88

Figure 20 Comparison of the genres based on reading practice frequency .............. 89

Figure 21 Comparison of the genres based on listening practice frequency ............. 90

Figure 22 Comparison of the genres based on writing practice frequency ............... 92

xx

Figure 23 Comparison of the genres based on speaking practice frequency ............ 93

Figure 24 Comparison of the learning and practice frequency of target language

knowledge and skill types based on action genre ...................................................... 95

Figure 25 Comparison of the learning and practice frequency of target language

knowledge and skill types based on adventure genre: ............................................... 97

Figure 26 Comparison of the learning and practice frequency of target language

knowledge and skill types based on role-playing genre ............................................. 99

Figure 27 Comparison of the learning and practice frequency of target language

knowledge and skill types based on strategy genre .................................................. 102

Figure 28 Comparison of the learning and practice frequency of target language

knowledge and skill types based on strategy genre .................................................. 104

Figure 29 Overview of themes and categories ........................................................ 142

Figure 30 Language learning in single-player action games ................................... 188

Figure 31 Language learning in multiplayer action games ..................................... 190

Figure 32 Language learning in single-player adventure games ............................. 192

Figure 33 Language learning in multiplayer adventure games ............................... 194

Figure 34 Language learning in single-player role-playing games ......................... 196

Figure 35 Language learning in multiplayer role-playing games ........................... 198

Figure 36 Language learning in single-player strategy games ................................ 200

Figure 37 Language learning in multiplayer strategy games .................................. 202

Figure 38 Language learning in single-player simulation games ............................ 204

Figure 39 Language learning in multiplayer simulation games .............................. 206

Figure 40 Optimal Game Mode and Genre Combinations for Learning and

Practicing Target Language Knowledge and Skills ................................................. 208

1

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

1.0. Presentation

In this chapter, the theoretical background of computer games and language

learning is outlined and the rationale for the research study is put forward. Firstly,

language learning theories associated with computer games and language learning are

presented via conceptual and empirical findings in the literature. Following this, the

need for the investigation of the potential effects of game modes and genres on

computer games and language learning is argued with the gap in the literature and the

importance of investigating this issue. Finally, the research questions that formed the

basis of the research study are presented.

1.1. Theoretical Background

Game-based language learning is as old as Computer Assisted Language

Learning (CALL) itself. One of the earliest systematic applications of CALL is

traditionally regarded as PLATO (Programmed Logic/Learning for Automated

Teaching Operations), which was founded in the University of Illinois in 1959 to teach

different subject areas including languages (Beatty, 2010, p. 20). Computer games that

were developed for the purpose of language learning and teaching were included in

PLATO system (Peterson, 2013, p. 61). Ever since the 1950s, serious games (games

that are specifically designed for learning) and commercial games (games that are

designed primarily for entertainment purposes) have been utilized for learning and

teaching languages. As a natural consequence of the tendency of students and teachers

to use computer games for learning and teaching languages, these games have also

been a point of inquiry among researchers interested in CALL.

2

A significant point of inquiry of the academic investigations in computer games

and language learning has been its theoretical rationale. Peterson (2013) points out the

studies of García-Carbonell et al. (2001), Thorne et al. (2009), and Zhao and Lai (2009)

in the identification of the theoretical background of computer games and language

learning (pp. 55-60). These researchers evaluated the characteristics of computer

games and provided explanations on how these characteristics could be beneficial for

language learning based on theories of gaming, learning, and language learning,

relating to concepts such as input and monitor (Krashen, 1982; Krashen, 1985),

interaction and negotiation of meaning (Long, 1981; Long, 1985), and output (Swain,

1993). Garcia-Carbonell et al.’s study was an overall evaluation of computer games

and simulations in the development of communicative competence in a second

language. The researchers argue for the language learning benefits of computer games

from the perspective of cognitive and interactionist approaches to SLA. The

negotiation of meaning during in-game tasks and the development of communicative

competence with the use of language skills in simulations and computer games were

emphasized in terms of their benefits for language learning. In addition to these,

exposure to comprehensible input, learner-centeredness, and a decrease in affective

factors with increased motivation were also underlined as factors that facilitate

language learning through simulations and computer games.

Unlike Garcia-Carbonell et al. (2001), the studies of Thorne et al. (2009), and

Zhao and Lai (2009) specifically targeted MMO (Massively Multiplayer Online)

games and MMORPGs (Massively Multiplayer Online Role-playing Games)

respectively. Thorne et al. evaluated the benefits of MMO games from the perspectives

of language socialization theory and situated learning theory. They argue that the

opportunities for language use and communication as a result of the inevitable

collaboration among players in these games facilitate language socialization. In

addition, they also highlight the goal-oriented nature and meaningfulness of these

communicative activities between players as contributing factors for language

learning. Zhao and Lai dwelled on the benefits of MMORPGs in foreign language

learning from the viewpoint of cognitive and sociocultural approaches to second

language acquisition (SLA). They hold that opportunities for receiving target language

input through in-game elements and meaningful conversational interactions with other

players including native speakers of English are valuable for learning language and

culture. Furthermore, they argue that MMORPGs increase learner motivation by

3

incorporating learning language and culture, and decrease the anxiety of learners by

creating an environment where they can overcome the inhibition of using the language

in front of their peers, which eventually reduces their affective filter. Even though the

studies of Thorne et al., and Zhao and Lai focus specifically on MMO games and

MMORPGs, most of the implications in these studies are also applicable to other

computer game genres.

Another theory evaluated within the scope of computer games and language

learning is involvement load hypothesis. Cornillie et al. (2010) discussed the

implications of the involvement load hypothesis by Laufer and Hulstijn (2001) in their

study which dwelt on the role of role-playing games (RPGs). The involvement load

hypothesis advocates for increased retention of acquired vocabulary items in case the

involvement stimulated by the task is high based on the need for a specific vocabulary

item for the completion of the task, the search for the vocabulary item through various

means, and the evaluation of the vocabulary item with other items. Cheung and

Harrison’s (1992) study is provided in the paper as an example of the involvement

factor of need in that the retention of vocabulary items may be higher if their

significance for the completion of the task is high, as well. The studies of Miller and

Hegelheimer (2006) and Ranalli (2008) are put forward as investigations that can be

regarded within the view of the involvement factor of search based on the

concentration of learners on specific vocabulary items and the inquiry of these. An

example of the involvement factor of evaluation is given through the study of Neville

et al. (2009) on the basis of detailed descriptions of items or events in RPGs, which

require learners to evaluate and find vocabulary items that are appropriate for the

situation for the story to proceed.

The theory of affordances has also been associated with computer games and

language learning. In their review, Reinhardt and Thorne (2020) associate digital

games and language learning with affordances theory, by underlining a recent interest

among researchers to employ the ecological concept of affordance by Gibson (1979)

in trying to understand the possibilities of learning in gaming environments. The study

is centered around eight main game-based affordances for language learning. The first

affordance is the involvement of gamer learners in contextualized linguistic

environments in which they are exposed to target language items in interactional

settings. Secondly, the affordance of time and iterative play is underlined, considering

the opportunity of adjusting the normal progression of time and repeatability of the

4

tasks in digital games. Thirdly, the affordance of games in providing gamer language

learners a self-contained environment of doing practice in a target language by

concealing their identities, which may increase the amount of risk-taking and decrease

the potential negative effects of anxiety, is pointed out. The fourth affordance is related

to the meaningful use of language in digital games in pursuit of a specific goal and the

opportunity to receive feedback through in-game elements and conversations. The fifth

affordance dwelt on the opportunities provided by digital games in interacting with

others to realize common goals through languaging and coordination. The sixth

affordance is related to the development of identity performance, which is regarded as

an integral part of L2 learning, through accommodation and incorporation of different

perspectives, cultures, and understandings. The seventh affordance is specific to

mobile digital games, specifically the convenience provided by them in choosing when

and where to play games, and the contextual richness offered by them through features

such as augmented reality. The final affordance is the opportunities provided by digital

games in having free and independent practicing of an L2 outside the scope of formal

teaching, which is the case of millions of gamers all over the world.

The affordances theory was not the only theoretical consideration of digital

games and language learning in the review of Reinhardt and Thorne (2020). They also

evaluated the implications of game-based language learning in the light of major

approaches to SLA. In the review, features of digital games such as repeated exposure

to a target language, reinforcement, and feedback were associated with the principles

of a structural view of SLA, a behaviorist approach which primes the role of repetitive

practice in the acquisition of second languages. Elements like comprehensible input,

meaningful language use, and negotiation of meaning through interactions were

related to cognitive approaches to SLA, which highlight the role of cognitive processes

in the acquisition of languages. Finally, opportunities provided by games in being

involved with online communication, collaboration, and participation in communities

were linked with the sociocultural view of SLA, which point out the role of the role of

social relations and interactions in the acquisition of languages.

Zone of proximal development is another theory associated with computer

games and language learning. Reviewing the gaming and language learning literature,

Hansen (2018) related some language learning activities taking place in computer

game environments to Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development, which is defined as

what a learner can learn through guidance. The study indicates that the source of

5

guidance in language learning is usually regarded as a teacher or a more educated

person. However, the researcher argues that a number of elements in a game

environment can provide a similar guidance for the zone of proximal development to

occur. Focusing on World of Warcraft, the instructions provided to players and the

interactions carried out within game through often simplified texts, and the opportunity

of players to be engaged with such content as many times as needed for a satisfactory

level of comprehension based on their language proficiency are highlighted as

facilitators of zone of proximal development for language learners.

Besides the theoretical justification of computer games and language learning,

researchers have also been interested in the empirical investigation of the hypothesized

benefits of computer games in language learning. Several studies have been carried

out in this regard to find out whether computer games are beneficial for improving

target language knowledge and skills. For example, computer games were empirically

investigated and found beneficial for learning vocabulary in the studies of Palmberg

(1988), Miller and Hegelheimer (2006), Rankin et al. (2009), Bakar and Nosratirad

(2013), Huang and Yang (2014), Franciosi (2017), Chen et al. (2020), and Rahman

and Angraeni (2020). Similarly, it was found in the studies of Miller and Hegelheimer

(2006), and Turgut and İrgin (2009) that computer games were beneficial for learning

target language grammar, as well. Along with these, studies that were conducted by

Rankin et al. (2009), De Wilde and Eyckmans (2017), Shahrokni et al. (2020), and

Yang and Chen (2020) can be exemplified for the advantages for developing target

language skills in computer games.

The exposure to English in computer games has been uncovered in a number

of recent studies dwelling on the role digital technology in language learning. In a

study investigating the digital practices of English learners, Dincer (2020) found out

that online games provided significant benefits for Turkish learners in terms of

learning target language grammar and practicing language skills. The chances of

communicating with other English speakers and learning new language structures in

these games were highlighted as the benefits of computer games for language learning.

A review of studies on technology-enhanced language learning by Shadiev and Yang

(2020) also uncovered the role of computer games in language learning. In fact, digital

games were found to be the most frequently used technology by language learners,

along with online videos. The researchers highlighted the potential use of computer

games through in-class activities and as part of out-of-class activities for the purpose

6

of language learning. Similar findings were also evident in the study of Li and Lan

(2021). The researchers underlined the potential of computer games in improving

language learners’ motivation and having interaction with English speakers by also

noting the need for further studies for increasing the outcome of using games for the

purpose of language learning.

1.2. Operational Concepts Related to English Language Learning within

the Present Study

It is important to understand some key concepts within the scope of the present

study in relation with computer games and language learning. Studies on computer

games and language learning mostly focus on learning target language knowledge, the

learning of vocabulary and/or grammar in computer games in a second or foreign

language, and practicing target language skills, using the four main language skills

(reading, listening, writing and speaking) in a second or foreign language. There are

different definitions and explanations in the field of language learning as to what

learning target language knowledge and practicing target language skills entails.

However, there are certain definitions that can guide us through the meaning of these

expressions. Firstly, target language knowledge and skills as distinct language learning

outcomes are stated in several studies such as the ones by Hall (2010) and Read and

Barcena (2021). The term target language is often associated with vocabulary

knowledge and grammar knowledge as in the study of Kim and Cho (2015) whereas

target language skills are associated with the four main skills, namely reading,

listening, writing and speaking as in the study of Atkinson and Díaz (2000).

Hatch and Brown (1995) put forward a process of vocabulary learning which

involves having sources for encountering new words, getting a clear image of words,

learning the meaning of words, making memory connections between form and

meaning, and using words. According to Nation (2001) vocabulary learning entails

knowing the spoken and written forms along with word parts; forms and meanings,

concepts and referents, and associations of the word; and grammatical functions,

collocations, and constraints of use of a specific word. Ishikawa (2018) defines

grammar learning as “acquiring the abilities to process as well as to produce the target

construction more accurately” (p. 52). The learning of vocabulary and vocabulary can

occur implicitly through natural repeated exposure, as in the form of incidental

7

learning via meaning focused communicative activities, or can be taught explicitly

through instruction (Ma & Kelly, 2006). Learning target language knowledge is

among core language learning outcomes, thus playing an important role in target

language development (Hall, 2010).

Target language skills, on the other hand, are regarded as the four main skills

of a language, namely reading, listening, writing, and speaking. Language practice is

defined by Tollefson (1999) as how a language is used by a speaker when the freedom

to use a language is provided to the speaker from a variety of languages. Elizawati et

al. (2018) define language skills as “a person's ability to use language in writing,

reading, listening, or speaking” (p. 38). Kholiq (2020), on another hand, defines

language skills as “a person's ability to use their language competencies” (p. 176).

Similar to learning target language knowledge, practicing language skills plays an

important role in target language learning and development (McCabe & Meller, 2004;

Kraemer et al., 2009; Gruber & Kaplan-Rakowski, 2022).

Considering the definitions for target language knowledge and skills, and what

the learning and practicing of these knowledge and skills entails in the literature along

with the scope and aims of this research, the concepts for target language knowledge

and skills are regarded as the following in the study. Target language refers to a

language that is aimed to be learned as a second or a foreign language, such as English

as in the case within this study. Target language knowledge involves vocabulary

knowledge and grammar knowledge. Vocabulary knowledge refers to knowing

spelling, the pronunciation, and the meaning of target language vocabulary items.

Similarly, grammar knowledge refers to knowing the spelling, the pronunciation, and

the meaning of target language grammatical structures. The learning of vocabulary

items and grammar structures can take place implicitly via natural exposure or

explicitly via looking up encountered items and structures. Target language skills

include reading, listening, writing, and speaking. Practicing these skills refers to using

these skills to understand target language input or to communicate with other speakers

of the target language by creating target language output. Considering the theoretical

background of computer games through cognitive and sociocultural approaches to

second language acquisition and the empirical studies in the literature, learning target

language knowledge and practicing target language skills in different computer game

8

modes and genres are expected to contribute to the target language learning and

development of gamer language learners.

1.3. The Need for the Study

According to Newzoo (2020), there were 2.7 billion gamers worldwide in

2020. In Turkey, the number of gamers was stated as over 30 million as of 2018

(Gaming in Turkey, 2018). An overwhelming majority of these gamers worldwide are

non-native speakers of English, including the gamers in Turkey. Considering the fact

that most computer games have an English interface and most of the written and oral

communications in online games played on international servers are in English, these

non-native speakers are frequently exposed to English, and they are often expected to

communicate with other players in English. As a result, computer games possess a

valuable potential for the improvement of target language knowledge and skills of

numerous English learners all over the world.

Computer games have different genres and modes. Genre relates to how

computer games are classified according to their characteristics, and mode refers to

whether the game is played as single-player or multiplayer. There is not a universal

agreement as to the genre-related categorization of computer games and the lines

among the genres are not always clear-cut. In addition, although there is a dominant

genre for most computer games, games may fall under the category of multiple genres,

as well. Apperley (2008) grouped computer games under the genres of simulation,

strategy, action and role-playing. The genres included in Sherry and Pacheco’s (2006)

study were shooters; puzzle, arcade, card and dice game; fantasy, role-playing and

adventure; quiz and trivia; and sports and simulation. The main video game genres that

were included in a Wikipedia article were action, action-adventure, adventure, role-

playing, simulation, strategy, sports and MMOs (List of video game genres, 2021). As

to the preference of gamers towards these genres, a survey by Statista (2019)

conducted with 44.160 casual gamers aged 16-64 indicated that the %75 of the

participants played action games, %67 played cooperative/multiplayer games, %47

played casual games, %45 played strategy games, %45 played role-playing games and

%39 played sports games. A survey conducted by Opera (2020) on gaming habits of

more than 190.000 participants indicated that the most commonly preferred genres by

female gamers were adventure (61%), role-playing (56%), action (42%), MMORPG

9

(40%) and strategy (31%), and the most commonly preferred genres by male gamers

were shooters (65%), action (52%), adventure (52%), and role-playing (45%).

Considering their scope and prevalence, the genres that were included as part of the

present study were action, adventure, role-playing, strategy, and simulation. Other

genres were not involved either because they were regarded as a subgenre to one of

the aforementioned genres, or they were not so prevalent.

Action games are characterized by the use of physical capabilities such as

demonstrating quick response times and displaying a satisfactory level of hand-eye

coordination in an effort to complete in-game objectives. Action game players are

often required to complete certain levels or achieve a specific goal by eliminating

opponents by using their reflexes in fast-paced scenarios. Some notable subgenres of

action games include shooter games and fighting games. A single character is usually

controlled by players in action games. This character commonly has specific powers

and abilities. Single-player action games generally require players to overcome in-

game elements to complete levels. On the other hand, multiplayer online action games

tend to involve teams competing against each other and they require teammates to

communicate among themselves to defeat the opposing team. Some popular action

games include Counter Strike, Doom, Call of Duty, PUBG, Fortnite, Valorant, Grand

Theft Auto V, Red Dead Redemption II, Batman: Arkham Knight, Super Smash Bros.

Ultimate, and Street Fighter V.

Adventure games offer players an opportunity to set out on an adventurous

journey through the lens of the protagonist. The genre is characterized by exploration

and problem-solving. In adventure games, players often control a protagonist on a

quest to achieve a specific goal. During this journey, the player is expected to explore

the environment and solve puzzles to proceed in the storyline. Adventure games tend

to involve dialogues with NPCs that guide the player through the objectives that need

to be completed. The problem-solving mechanics often depend on such conversations

or visual cues. In contrast with the other genres, the 2D game engine is still widely

preferred in adventure games. In addition to popular 3D adventure games, a number

of 2D adventure games manage to attract a substantial number of players every year.

Some notable adventure games are The Walking Dead, Terraria, Welcome to Elk, The

Curse of the Monkey Island, The Wolf Among Us, The Longest Journey, Grim

Fandango, Primordia and Tales of the Neon Sea.

10

In role-playing games, players are expected to take the role of a character to

commonly follow a storyline of quests. Role-playing games are typically set in

fictitious scenarios and settings or fantasy worlds. These games can have a linear

design where the players need to follow a predetermined storyline, or they can have

an open-world design in which the player is free to explore and follow multiple

storylines simultaneously. The decisions that the player makes while playing the game

usually has an important impact on the outcome of the game in these games. Character

development is another important feature. Characters tend to acquire new skills and

items as they level up throughout the story, and more information is gathered about

the character as the story progresses. In single-player role-playing games, players are

often required to read and listen to quests that are typically given to the player by non-

playable characters (NPCs). In multiplayer role-playing games such as MMORPGs,

players also communicate with other players by writing and speaking in addition to

following the questline. Some notable role-playing games are The Witcher 3: the Wild

Hunt, The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim, Dark Souls, World of Warcraft and EverQuest.

Strategy games typically include scenarios in which a player controls a large

number of characters, units, buildings and similar elements to achieve in-game

objectives. These objectives can involve eliminating opponents or completing

particular levels. Strategy games commonly involve some type of warfare which

requires the player to manage resources to produce units and use these units to ensure

victory. Another usual characteristic in strategy games is racing against time. Players

that are good at time management in building infrastructure, creating units and

developing strategies have a greater chance of having success at strategy games. In

strategy games, players generally have an aerial point of view. In addition to managing

the time, units, and resources, controlling the map by frequent explorations through

units is also crucial. Strategy games can turn-based or real-time. Some popular strategy

games include Age of Empires II, Total War Series, Warcraft III, League of Legends,

Defense of the Ancients, Heroes of the Storm, and Sid Meier's Civilization VI.

Simulation games aim at creating a model various real-life situations or

activities. In contrast with the previous genres where the fictitious scenarios are

dominant, simulation games are most often based on real-life scenarios. Whereas the

previous genres are more oriented on completing objectives or achieving victory,

simulation games take its focus as providing players the opportunity to experience an

activity as closely as it actually is in real life. In addition to being designed and played

11

for the purpose of entertainment, simulation games can be designed and played for

training in a specific area, as well. A number of scenarios such as sports, racing, city-

building, aviation, and daily life can be the focus of simulation games. Some prominent

examples of simulation games include FIFA 21, The Sims 4, Euro Track Simulator 2,

Microsoft Flight Simulator, PES 21, Farming Simulator 19, SimCity, Kerbal Space

Program, and NBA 2K21.

Most computer games can be played in single-player and multi-player game

modes. The single-player mode is most often played offline. In this game mode, the

interaction is often with in-game characters and the environment. Players rely on

themselves to complete objectives or to defeat artificial intelligence. The multiplayer

game mode, on the other hand, involves other players in addition to the individual

player. In multiplayer games, players are typically teamed up with other players in a

pre-determined or random manner, and they compete against similarly created teams,

which is called a Player versus Player (PvP) format. However, not all multiplayer

games include team-based competition. Some multiplayer games have a format of

Player versus Environment (PvE) in which all the players compete against the

environment together. Although the multiplayer game mode can be played on a local

network, the vast majority of multiplayer games are played online. In addition to the

player interacting with in-game characters and the environment, multiplayer games

tend to involve written and oral communication among the players.

Due to their characteristic differences, computer game genres and modes

involve diverse ways of getting exposed to or using the target language. For example,

whereas a single-player role-playing game may often require players to read and listen

to quests to be completed as part of the game, an online adventure game may

necessitate players to listen to and speak to their teammates to increase the likelihood

of winning. Consequently, the exposure to language and the opportunities for language

practice might differ considerably during gaming sessions. There have been some

research studies that have focused on potential differences in different game modes

and genres in terms of language learning in computer games. In their study, Reinhardt

and Thorne (2020) argued that some genres including simulation, adventure, and turn-

based strategy games that allow learners to take their time interacting with in-game

language content at their own pace by also allowing them the opportunity to use

captions are more optimal for language learning than others. They called for large-

scale mixed-methods research studies to investigate language use and language

12

learning in digital games from multiple perspectives including an evaluation of the

issue across the genres, by building on an earlier call by Sykes and Reinhardt (2012).

A relatively more-detailed evaluation of game types and genres in computer

games and language learning was done by Yudintseva (2015) through an evaluation

of studies in literature. One important identification in the study is a potential challenge

that MMORPGs, adventure, and rhythm games can pose to lower-level language

learners, who might find the content in these games too loaded to deal with. Another

point about genres in the study is a comparison about the exposure to vocabulary. It is

stated that some games with the genres of role-playing, sport, shooter, and strategy

have field-specific terminology whereas in daily-life simulations there is usually

exposure to some of the most frequent words in English. In addition, genres were

compared with regard to their influence on target language skills. For example, the

study indicates that sports and adventure genres are more beneficial to reading and

listening than writing and speaking, and first-person shooters do not display an

important level of development in listening. The researcher further suggests that the

effects of genre on language learning might be at an individual level, depending on the

characteristics of a learner in terms of gender, proficiency, and experience in gaming.

Despite some covering, the potential impact of game modes and genres on

computer games and language learning has largely been understudied throughout the

years. The present study aimed to fill this gap by uncovering the impact of genres and

modes of computer games on learning English as a foreign language from the

perspective of gamer learners of English. Overall, it intends to find out about the

following points. First of all, it seeks to find out whether there is a significant

difference between single-player and multiplayer game modes of computer games in

terms of the perceived frequency of learning and practicing English. Secondly,

potential statistical differences among action, adventure, role-playing, strategy, and

simulation genres in terms of the perceived frequency of learning target language and

skills were expected to be revealed. The third aim was to find out about the potential

statistical differences among these genres in terms of the perceived frequency of

learning and practicing target language knowledge and skills. The fourth aim of the

study was to uncover how language learning and practicing activities take place in

different computer game modes and genres. Finally, the study aimed to reveal the

opinions of gamer EFL learners in learning and practicing English in different

computer game modes and genres.

13

1.4. Significance of the Study

Scientific literature shows that computer games are valuable sources and

environments for language learning. Countless people from all over the world spend

substantial amounts of time on computer games readily. Most of these people are non-

native English speakers and they benefit from computer games in terms of language

learning knowingly or unknowingly. An increasing number of studies on computer

games and language learning aim to provide a deeper understanding of this process.

The present research study aimed to contribute to the scientific literature on computer

games and language learning by uncovering the potential effects of computer game

modes and genres on computer games and language learning. By doing so, it targeted

at enabling a more profound understanding of what potential differences exist across

and within different computer game modes and genres with regard to language

learning through the perceptions and opinions of gamer learners of English. This, in

turn, can provide valuable implications for anyone related to computer games and

language learning such as gamer learners of English, teachers of English, academicians

interested in computer games and language learning, and computer game creators.

First of all, considering the fact that the study aims to examine the opinions of

gamer English learners on the effectiveness of computer game modes and genres in

learning target language knowledge and skills comprehensively, the findings of the

study offer profound perspectives into the theoretical background of computer games

and language learning. The identification of whether computer game modes and genres

have a significant impact on learning target language knowledge and improving target

language skills can contribute to the literature both in terms of interpreting the existing

body of research more effectively and by providing additional directions for further

research in computer games and language learning. From a quantitative perspective,

the outcome of the existing studies with regard to whether computer games are

significantly effective in developing specific target language knowledge and skills and

not significantly effective in developing others can be interpreted more profoundly

based on the quantitative findings of the present study. The qualitative findings, on the

other hand, can help researchers have further insights into why specific computer game

modes and genres are effective or not effective in helping learners improve their target

language skills. The identification of these issues can lead to areas of further research

14

in which more information can be gathered on the use of computer games in learning

a foreign language.

From a more practical point of view, the findings of the study present insights

for language learners who play computer games regularly. For example, the

identification of whether specific target language knowledge and skill types are

learned or practiced better through a particular mode or genre, whether some target

language knowledge and skill types in a specific computer game mode or genre can be

practiced more frequently compared to others, and what the advantages and

disadvantages of specific computer game genres are in terms of language learning may

increase the language learning benefits learners get from computer games. Getting

more information about the aforementioned issues can also help teachers guide their

students to get more benefits from computer games in terms of language learning and

teaching. Based on any potential differences among computer game modes and genres

with regard to the learning of specific knowledge and skills, language teachers can

guide their gamer learners to play specific modes and genres based on their needs. For

example, relying on a potential outcome in which reading skill is improved

significantly more in a specific computer game genre compared to others, then teachers

can guide students interested in playing computer games and having problems with

target language reading to play games in that genre.

In addition to offering information about potential differences among computer

games with regard to the development of target language knowledge and skills, the

present study can also help learners and teachers identify the target language

knowledge and skill types that specific game modes and genres can contribute the most

and the least. This can aid us in uncovering the knowledge and skill types that are most

likely to be practiced and ignored by players of specific genres and thus guide students

accordingly in order to avoid an unbalanced development of target language skills as

much as possible. For instance, based on a potential outcome in which that a specific

game mode or genre combination is significantly more beneficial for improving

reading and listening skills than writing and speaking, then learners who play these

games regularly can be advised to be engaged in additional activities that can increase

their chances of improving writing and speaking skills in order not to overlook their

development in these skills.

The findings of the present study provide implications for game development,

as well. By uncovering the potential differences and indifferences among and within

15

computer game modes and genres with regard to the development of target language

knowledge and skills, the findings can have implications for game developers in terms

of which areas of language learning specific game modes and genres are potentially

stronger or weaker at. This would be quite meaningful considering the fact that the

vast majority of the gamers all over the world are non-native speakers of English and

a great many of those have hopes of improving their English knowledge and skills

while playing computer games. Knowing about the pros and cons of game modes and

genres in learning target language knowledge and improving target language skills,

game developers can provide additional features of language support and opportunities

for language exposure and practice in areas where the chances of exposure and practice

are limited in a specific game mode or genre. As an example, depending on a potential

outcome in which a certain genre is significantly less effective in vocabulary learning

compared to other areas of language development, game developers designing

adventure games can be urged to come up with additional features supplemented or

integrated into these games in order to compensate such a disadvantage.

1.5. Research Questions

The following research questions were employed in the study:

1) Is there a significant difference between single-player and multiplayer

computer game modes with regard to the participating gamer learners’ perceived:

(a) learning of target language vocabulary items?

(b) learning of target language grammar structures?

(c) practicing of target language reading?

(d) practicing of target language listening?

(e) practicing of target language writing?

(f) practicing of target language speaking?

2) Is there a significant difference among action, adventure, role-playing,

strategy, and simulation genres with regard to the participating gamer learners’

perceived:

(a) learning of target language vocabulary items?

(b) learning of language grammar structures?

(c) practicing of target language reading?

(d) practicing of target language listening?

16

(e) practicing of target language writing?

(f) practicing of target language speaking?

3) Is there a significant difference with regard to the participating gamer

learners’ perceived learning of target language knowledge and practicing of target

language skills within the genre of:

(a) action?

(b) adventure?

(c) role-playing?

(d) strategy?

(e) simulation?

4) What kind of language learning and practicing activities take place in

different computer game modes and genres?

5) What are opinions of participating gamer language learners in terms of

language learning in different game modes and genres?

17

CHAPTER II

LITERATURE REVIEW

2.0. Presentation

This section includes a review of literature on computer assisted language

learning and computer games and language learning. Firstly, it provides a brief

background for the development of computer assisted language learning, and then it

continues with the emergence and development of computer games and language

learning research alongside the main research area. It provides a review of notable

studies conducted on learning target language knowledge and practicing target

language skills via commercial computer games with different game modes and

genres.

2.1. Computer Assisted Language Learning