UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO

The Foundations of Videogame Authorship

A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor

of Philosophy

in

Art History, Theory and Criticism

by

William Humberto Huber

Committee in charge:

Professor Lev Manovich, Chair

Professor Grant Kester

Professor Kuiyi Shen

Professor Stefan Tanaka

Professor Noah Wardrip-Fruin

2013

©

William Humberto Huber, 2013

All rights reserved.

iii

SIGNATURE PAGE

The Dissertation of William Humberto Huber is approved, and it is acceptable in quality

and form for publication on microfilm and electronically:

Chair

University of California, San Diego

2013

iv

DEDICATION

With gratitude to friends, family and colleagues.

To Samantha, with deepest devotion, for her friendship, affection and patience.

To Rafael, for whom play is everything.

v

EPIGRAPH

Art is a game between all people, of all periods. – Marcel Duchamp

vi

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Signature Page ............................................................................................................... iii

Dedication ..................................................................................................................... iv

Epigraph ..........................................................................................................................v

Table of Contents .......................................................................................................... vi

List of Figures ............................................................................................................. viii

List of Tables...................................................................................................................x

Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................... xi

Vita ............................................................................................................................. xiii

Abstract of the Dissertation............................................................................................ xv

Introduction .....................................................................................................................1

Chapter 1. The semiotic elements of videogames .............................................................7

Play as signification and interpretation.............................................................................................................. 17

Ludology and narratology .................................................................................................................................. 25

Revisiting semiotics in interactive media ......................................................................................................... 31

Semiotic registers ................................................................................................................................................... 40

Genre and interpretation...................................................................................................................................... 48

Styles of game design........................................................................................................................................... 66

Proceduralism and anti-proceduralism. ........................................................................................................ 77

Chapter 2. Signs in play: Fatal Frame II and modal dynamics ........................................ 80

Modes: aggregations of signs ................................................................................................................................. 80

Modes as configurations ..................................................................................................................................... 86

Fatal Frame II ............................................................................................................................................................... 92

vii

The dominant modes of Fatal Frame II ........................................................................................................ 96

In the mode for love: The Marriage as single-mode game ................................................................ 118

Game traversals and methodology .................................................................................................................... 124

Capturing Frames ................................................................................................................................................ 126

Modal rhythms ..................................................................................................................................................... 129

Modes are software; registers are conceptual frames. .............................................................................. 132

Ludic activation of the uncanny.................................................................................................................... 135

Semi-autonomous elements ............................................................................................................................ 137

From a theory of signs to models of authorship ..................................................................................... 143

Chapter 3. playing with space, playing with people ...................................................... 145

8-bit geo-space .......................................................................................................................................................... 146

Game-space and game-place. .............................................................................................................................. 149

Designed spatiality ............................................................................................................................................. 154

Game-spaces ......................................................................................................................................................... 162

Harvey’s model for the production of space............................................................................................ 165

Spaces of Final Fantasy ........................................................................................................................................ 171

Material space and the production of bodies ........................................................................................... 178

Representations of space (and place): producing worlds ................................................................... 186

Spaces of representation: Spira revisited .................................................................................................. 193

The matrix of spatialities revisited .............................................................................................................. 196

Final Fantasy XI: multiplayer games as constrained spaces ................................................................. 198

Virtual worlds of difference ........................................................................................................................... 202

Designed constraints .......................................................................................................................................... 206

Situational constraints ....................................................................................................................................... 211

Designing intersubjectivity in games ............................................................................................................... 217

Conclusion .................................................................................................................. 221

References ................................................................................................................... 232

viii

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1.: Kingdom Hearts video traversal. ....................................................... 45

Figure 2.: D-Day (1982 arcade game)................................................................. 54

Figure 3.: D-Day cabinet and controller.............................................................. 54

Figure 4.: Medal of Honor: Allied Assault (1999) - Omaha Beach sequence ....... 58

Figure 5.: First-person view of Medal of Honor: Allied Assault .......................... 59

Figure 6.: Medal of Honor: Allied Assault, sniper-scope view. ........................... 62

Figure 7.: Call of Duty 2 (2005) Cutscene from the assault on Pointe du Hoc

mission. ......................................................................................................................... 63

Figure 8.: Company of Heroes: Normandy landing sequence .............................. 66

Figure 9.: Braid a sole-authored independent game created by J. Blow (2010) ... 70

Figure 10.: B.U.T.T.O.N. Douglas Wilson and the Copenhagen Game Collective

(2009) ............................................................................................................................ 73

Figure 11.: The Graveyard. Tale-of Tales, (2008) ............................................... 76

Figure 12.: The Path. Tale-of-Tales. (2009) ........................................................ 76

Figure 13.: The two parts of H-LAM/T, from Barnes (1997) .............................. 83

Figure 14.: "A diagram representing the two active domains within the H-LAM/T

system." ......................................................................................................................... 84

Figure 15.: Fatal Frame II: Crimson Butterfly. Montage of frames in non-

interactive mode. ........................................................................................................... 98

Figure 16.: Control schema for the dominant gameplay modes of Fatal Frame II,

from the instruction manual. ........................................................................................ 103

Figure 17.: Montage of frames in field (navigational) mode.. ........................... 105

ix

Figure 18.: Montage of a sequence in viewfinder mode. ................................... 109

Figure 19.: Combat mode, with discreet signifiying elements highlighted. This

frame is from an instant during the process of combat in which one feature of viewfinder

mode which is usually stable—the focus ring—disappears briefly: immediately after a

shot has discharged. ..................................................................................................... 112

Figure 20.: The Marriage. Rod Humble (2006) ................................................. 119

Figure 21.: Distellamap: Combat. Ben Fry, 2005 .............................................. 123

Figure 22.: Missle Command, final screen. ....................................................... 126

Figure 23.: Fatal Frame II: Crimson Butterfly (speed-run by Persona) – the

clouded regions are an artifact of his/her inconsistent recording technology. Completely

white frames indicate the end of combat. The speed-run footage was sample at the rate of

one frame per second. The entire traversal of the game by Persona took a little over two

hours. .......................................................................................................................... 128

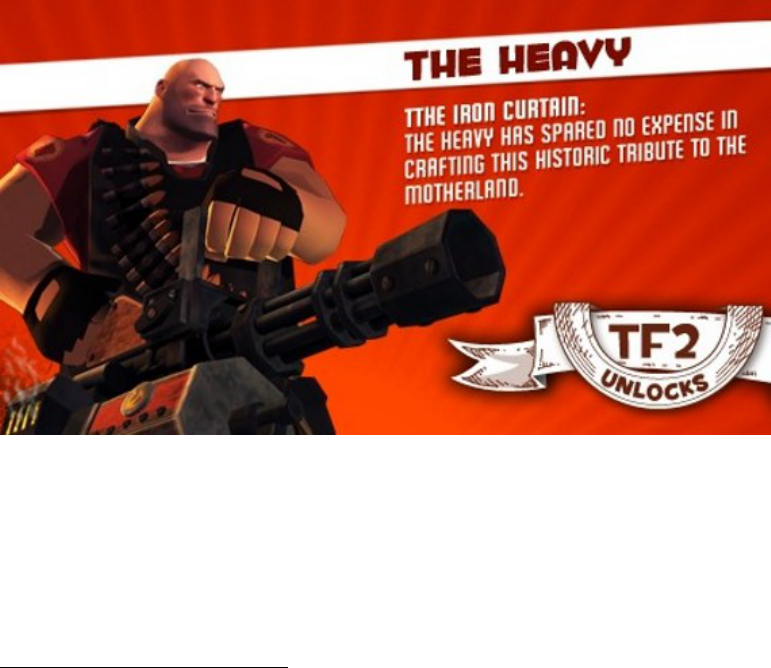

Figure 24.: "The Iron Curtain," in-game item for Team Fortress 2 obtained

("unlocked") by playing Poker Night at the Inventory .................................................. 141

Figure 25.: Screenshot, Google Maps 8-bit for NES screenshot. ....................... 147

Figure 26.: 0.0,0.0 – The prime meridian meets the equator in Google "Quest" for

NES ............................................................................................................................. 148

Figure 27.: Player-created dungeon map. From Mizer, 2011............................. 176

x

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1.: Peirce's categories of signs. ................................................................. 38

Table 2.: Spatial experience in digital media .................................................... 156

Table 3.: Final Fantasy releases, 1987 to 2012.................................................. 181

Table 4.: Videogame spaces and Harvey's matrix of spatialities ....................... 197

xi

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to acknowledge Professor Lev Manovich for his support as the chair

of my committee and as my advisor. His guidance, feedback and advice has been of

immeasurable help. I was fortunate to be his student, and am grateful for his patience and

encouragement.

I also acknowledge the support and constructive criticism of the rest of my

committee: Professors Grant Kester, Kuiyi Shen, Stefan Tanaka, and Noah Wardrip-

Fruin. I owe particular gratitude to Jeremy Douglass for his conversation and help over

the past several years: one could not ask for a better colleague. I also thank Kate

McDonald, Steven Mandiberg, Maggie Greene, Ian Mullins, Tara Zepel, Eduardo Navas,

Daniel Rehn, and Laura Hoeger for their friendship and conversation over the years.

From the UC San Diego Department of Visual Arts, I want to thank Sheldon

Brown, Benjamin Bratton, Amy Alexander, ,Jordan Crandall and Adrienne Jenik. I also

want to thank Christine Turner for her many words of advice and encouragement.

In the USC Interactive Media Division, I would like to thank Tracy Fullerton,

Peter Brinson. Jeremy Gibson, Kristy Norindr, Sam Roberts, Kurosh Vajanihad, and Jeff

Watson for their engagement and support. I also want to thank Ian Bogost and Gonzalo

Frasca for their insight, constructive criticism, and friendship

The students I have had the honor of teaching at UC San Diego and the University

of Southern California Interactive Media Division deserve acknowledgement, for

challenging me to remain current and relevant.

xii

Chapter 1 includes material from research performed with the Software Studies

Initiative at Calit2, under the supervision of Lev Manovich and with the help of Jeremy

Douglass. It includes images which have been exhibited elsewhere by the author.

Chapter 2 includes material drawn from long-term research that has appeared in

previous work by the author, including a paper presented with Laura Hoeger at the

Digital Games Research Association conference in 2007. The material has been

extensively re-written; however, her contributions were invaluable. Some of the work

from the same project was also published as “Catch and release: ludological dynamics in

Fatal Frame II: Crimson Butterfly” in Loading… The Canadian Journal of Game Studies,

Vol. 4 No. 6, 2010.

Chapter 3 includes material published inThird Person: Vast Narratives, edited by

Noah Wardrip-Fruin and Pat Harrigan, 2008. Cambridge, MA. The material has been

extensively revised and re-written for this dissertation, largely in response to the

recommendations of members of the committee.

xiii

VITA

1998

Bachelor of Arts, University of California, Berkeley

2004-2007

Teaching Assistant, Visual Art Department. University of California, San

Diego

2007-2013

Adjunct Faculty. School of Cinematic Arts, University of Southern

California

2009-2011

Associate instructor, Communication Department. University of

California, San Diego

2010-2011

Visiting Instructor. Southern California Institute of Architecture.

2013

Doctor of Philosophy, University of California, San Diego

PUBLICATIONS

“Understanding scanlation: how to read one million manga-translated fan pages.” (with

Lev Manovich and Jeremy Douglass) Image & Narrative, Volume 12, Number 1 (2011)

"Catch and release: ludological dynamics in Fatal Frame II: Crimson Butterfly."

Loading... Joural of Canadian Game Studies. Volume 4, Number 6 (5 April 2010)

"Epic spatialities: the production of space in Final Fantasy games." Book chapter in Third

Person: Vast Narratives, ed. by N. Wardrip-Fruin and P. Harrigan. MIT Press,

Cambridge, Massachusetts 2009.

"Notes on aesthetics on Japanese videogames." Book chapter in Art and Videogames, ed.

by A. Clarke and G. Mitchell. Intellect Books, London 2008. Revised version in press.

"Fictive affinities in Final Fantasy XI: complicit and critical play in fantastic nations." In

Worlds in Play: international perspectives in digital game research, ed. by S. de Castell

and J. Jensen. Peter Lang Verlagsgruppe, New York 2007.

EXHIBITIONS

“Mapping Time” exhibit. Calit2 gallery, UC San Diego. 2010

"Video Game Traversal: Kingdom Hearts II" in "SHAPING TIME" exhibition. Graphic

Design Museum, Breda Netherlands2010

"Game traversals" in Text Fields exhibition, as part of Future of Digital Studies 2010.

University of Florida, Gainesville 2010

xiv

"Shape of Science" in Here, not There, at Museum of Contemporary Art, La Jolla 2010

1997 Bachelor of Arts, University of California, Berkeley

xv

ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION

The Foundations of Videogame Authorship

by

William Humberto Huber

Doctor of Philosophy in Art History, Theory and Criticism

University of California, San Diego 2013

Professor Lev Manovich, Chair

Videogames have an ambiguous status as texts, in their dual nature as objects of

play and computer-mediated systems of representation. This has led to an impasse in

game studies, making it difficult to identify authorial voice, to make useful distinctions in

style of game design, and to account for the varieties of modes of reception.

This dissertation addresses the problem by proposing a model for the

interpretation of videogames based on the semiotic theory of Charles S. Peirce. This

model is the basis of a series of analyses of a range of videogames and other interactive

xvi

work on the dynamics of genre, style and authorship. While most of the research involved

the close play of games, using video transcriptions and tools to analyze game footage, it

also relies on interviews with game creators, industry reports, and discussions with game

players in both North America and Japan.

1

INTRODUCTION

This dissertation is an attempt to answer certain questions about digital games.

How do they “mean” things? What is the locus of their aesthetic effect? How do they

refer, in the sense that an image of a thing refers to that thing, or a film or novel refers to

that which exists in its diegesis? To what extent can we describe them as “authored,” and

to what extent “designed?” What does “style” mean for a playable form? What are the

conditions in their operation which makes them coherent to players as something which

can understand? Can the mechanics of a game produce allegory or metaphor, as per the

“allegorithm” or “control allegory” described by Alex Galloway?

1

Digital games have certain features which make them compelling objects of

study. They are highly multimodal, and their production incorporates writing, the design

of 3-dimensional objects and spaces, the production of cinematic sequences, animation,

sound engineering, and simulation. In the case of large-scaled game development, these

activities transpire within production chains chained together by networks, often on a

global scale. Lev Manovich describes games as “digitally native;” while music and

cinema have been changed through the widespread deployment of software in production

and the transcoding of music and film to digital media, the videogame constitutes

(arguably) a new form with novel conditions of reception. With origins in the Cold War

1

Alexander R Galloway, Gaming: Essays on Algorithmic Culture (University of Minnesota Press,

2006), 91.

2

technologies of simulation and planning, they emerged in the early 1960s from the

computer labs of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Over the 1970s and 1980s

they would appear in the demimonde of entertainment arcades and on consumer

electronic platforms made for middle-class homes. Eventually disseminating throughout

digital networks, played on mobile devices, the ascendency of digital gaming and its

ubiquity in the childhood of many of those born since the 1960s have made the ideas of

play and participation in the arts commonplace.

2

Though still seen, perhaps, as a minor form, they include technologies, tropes and

literacies which can be deployed very flexibly. This dissertation is about a wide range of

works in different scales and in different registers of cultural activity. What follows

applies as much to small, incidental pieces—like Rovio’s Angry Birds (2008) or Zynga’s

Farmville (2009) which are played “casually,” in interstitial time—as to installation-

based work which anticipate a reflective or considerative mode of engagement, such as

C-Level’s 2002 Waco Resurrection; from locative works meant for public performance

or engagement, such as Blast Theory’s Uncle Roy All Around You, or Aram Bartholl’s

2

See Claire Bishop, Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship (Verso

Books, 2012). Bishop describes the emergence of participation as a utopian lodestone in 20

th

and 21

st

century art, and its recuperation in the modern era. She notes that when she began her research in 2003,

participation was still a relatively marginal aspect of contemporary art practice, but that by the time her

book was ready for press, play and participation had taken a central role in gallery-based art scenes, as well

as in public art spaces and museums.

3

street performances, to small, personal works of personal expression, such as Rod

Humbles The Marriage or the community-created role-playing games created by

dedicating amateurs using tools such as Enterbrains’s RPG-Tsukuru , to commercial titles

created by hundreds of workers, like Final Fantasy XIII, and Civilization V, each of

which may provide hundreds of hours of play for gamers.

Yet despite this range of effects and features, they are all rule-driven systems,

most of which use software to encode those roles. They are designed and engineered by

creators who implement these systems of rules in software, and then ascribe meaning to

the various elements which instantiate those systems. There is transitivity among the

fields of practice described above: members of C-Level have also released works meant

for internet distribution; Rod Humble has worked on my mainstream, commercial titles;

Aram Bartholl’s work plays off of the game industry; the amateurs and hobbyist who

make personal games using RPG Tsukuru often respond to and appropriate commercial

games, using a vocabulary of tropes and representations that they learned as fans and

players.

Contemporary authorship is a flexible and distributable function. Recalling

Foucault’s idea of an “author-function,”

3

in which the figure of the author is created

within each discourse according to the interests of its participants (and according to the

3

Michel Foucault, “What Is an Author?,” in Textual Strategies: Perspectives in Post-Structuralist

Criticism, ed. Josué V. Harari (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1969), 141–160.

4

power and ability to determine that function,) the flexibility is more dynamic when the

text’s materiality is mostly software-based. The material contribution to and constraints

on the dynamics of authorship are one of the themes of this dissertation. Organizations,

teams, collectives and corporations can fulfill the functions of authorship, especially

when the text is a very large collection of assets and algorithms, which is available from

anywhere on the globe during the production process. Audiences, technologies,

distribution channels, and legal realities (franchising, intellectual property agreements

and constraints) also shape the way that that authorship is conceptually produced and

deployed. This dissertation lays a foundation for survey of the ways that authorship can

be configured by reflecting on the videogame as a system which produces meaning and

makes reference to things outside itself, and which generates experiences that are

available for interpretation and reflection.

The first chapter of this dissertation is a foundational exercise, describing how

videogames operate as systems of representation. The chapter begins with a review of the

important theories of play and games, especially the writing of Roger Caillois and Brian

Sutton-Smith, and describes the nature of an impasse which exists in contemporary game

studies: the distinction between the video game/computer game as a system of activity

and as a system of representation (usually conceived as narrative, due to the healthy

representation of literary scholars in games studies.) The chapter suggests a route past

this impasse: a model of the game as semiotic in a broad, phenomenological sense. This

model is built on the semiotic theories of Charles Sanders Peirce, whose taxonomy of the

sign accounts for the breadth of signification across the modalities of human perception.

5

The Peircean model of semiosis enables us to consider how effect perceived by the player

during a game can be understood as (at least possibly) authored.

The second half of the first chapter develops this model by applying it questions

of genre and style, understood here as organizing schema for the authored systems which

constitute a game. In the first case, genre is understood in terms of nested literacy

developed in the ongoing relationship between players and producers, through which

themes, topics and images are configured. The history of the use of D-Day across various

interactive genres is used for illustration. Style is understood in terms of the

foregrounding of specific conceptual registers of game experience as the site for aesthetic

experience: as the “place” in the game in which meaning occurs.

The second chapter begins with a description of modes as components of the

game as a material sign-system. Modes are divisions of the software into different

configurations, and different systems of meaning. Players learn to recognize different

modes as distinct regimes for interpreting the sign elements at hand. As semi-modular

software-driven systems, they can be developed by multiple teams working in parallel

with each other. The modes produce a natural point of segmentation for the engineering

of the game as a software-based system. The phenomenal experience of play integrates

all the conceptual registers of the game as systems of meaning and activity in the real-

time decoding of software running in modes. The dissertation focuses on one game, Fatal

Frame II: Crimson Butterfly, to work out this analysis.

The third chapter focuses on two sites of meaning in different game-design

traditions: the creation of spatial experience, and the authoring of relational dynamics. A

6

framework is drawn from the critical geography of David Harvey in the first case, and the

possibility of a relational style of game authorship to the design of multiplayer spaces is

invoked in the second. Videogames are located within a broader array of digital media

and networks in its ability to provoke different types of spatial cognition, and produce a

sense of place. The chapter centers on one game franchise, the Final Fantasy games from

1987 to the present, and concludes with a study of the online, massively-multiplayer

version of the game.

The dissertation concludes by relating the foundational work in games as

meaning-systems to the question of authorship. A sequence of authorial modes, from a

non-authorial culture of digital game design in the 1970s to the contemporary model of

distributed and delegated authorship on a global scale is laid out. The conditions of

authorship are described in terms of the changing material possibilities of game design

and collective software development.

.

7

CHAPTER 1. THE SEMIOTIC ELEMENTS OF VIDEOGAMES

In this chapter, I will argue for a model of digital game-play

4

as a player’s

dynamic interpretation of the signs produced by a game: an inquiry into the conditions of

authorship, particularly in the case of games, needs to rest on a sound model of the

conditions of reception. This model draws from Peircean semiotics, genre theory, and

theories of software culture. Existing models of game-play—those which are based on a

primary distinction between the game as a representational systems and the game as a

system of activity—have limited our understanding of the nature of authorship for these

games and related forms, and do not account for the dynamism and variety of games

which are being produced and consumed. They are also ill-equipped to explain genre

evolution in interactive media. I will use this model to clarify genre in games, and to

analyze one game in depth.

The key contributions of this chapter are, first, a model of gameplay meant to

address problems which occur when the distinction between game-play and content is

presumed. This model takes a semiotic approach to the study of games. It suggests a

4

The model proposed here applies to works which would lie outside of many definitions of

“games,” “digital games,” “video games,” and such. and would also fit simulations, interactive art works,

and interactive fiction. It may even apply to interfaces for social media and web applications, although to

the extent that they are generally designed to be transparent, rather than to be encountered as texts as such,

would dilute the usefulness of this kind of analysis to those kinds of software-based objects.

8

concept of game modes and their relationship to registers of game-interpretation

(developed in chapter two.) It also presents a research methodology which allows

detailed visualization of hundreds of gameplay.

These theories of play are interpreted and discussed as theories of signification,

and describes how contemporary debates in game studies are a result of an incomplete

model of game semiotics. The next section reviews Peircean semiotic theory and

introduces the concepts of game modes, which are software-based configurations of

signifying elements, and game registers, which are conceptual models of the game

system interpreted by the player working their way through the game. The interplay

between mode and register, and the dynamics of signifiers within games, is worked out in

a discussion of game genre.

My larger project is to investigate the relationship between authorship and

playable artifacts. Authorship, in a conventional sense, is a circular concept: it defines

some objects (written texts, films, computer games) as products of the creative activity

which bring them into being (writing, filming, programming, etc.), and then determines

the authorial nature of that activity in terms of our assumptions about the producer’s

relationship (such as intentionality, dialogue, development of style, intra-discursivity) to

these products. To break apart this circularity, I start with a formal model of playable

artifacts (games, simulations and related work) as authored systems by describing their

operations as sign-systems. A semiotic model for videogames and playable media allows

9

us to account for the range of configurations of the “author function

5

”—those aspects of

the work singled out, for various reasons, as being the basis for an attribution of

authorship—that are found in videogame production.

Videogames and other playable software-based media have come into being only

in the latter half of the previous century. It is thus easier to answer certain ontological

questions, because we have access to most of the forms which that thing has taken, and it

is easier to recover older senses of what that thing was than it might if it dated before

living memory: we are spared from strenuous hermeneutics, because we have the arrival

of these objects in living memory. Yet it is surprising how quickly habits of thinking set

in: how we naturalize one mode of reception over another, how we describe our

5

Foucault, “What Is an Author?,” 108. Foucault’s investigation into the (conceptual) history of the

idea of the author is useful but limited, in that it is still based on a privileging an idea of authorship as

related to the written word, even as the question of the auteur was being revisited in cinema: Francois

Truffaut’s essay on the auteur appeared in the pages of Cahier du Cinema only a few years before

Foucault’s. Foucault himself observes, “Up to this point, I have unjustifiably limited my subject. Certainly

the author function in painting, music and other arts should have been discussed, but even supposing that

we remain within the world of discourse, as I want to do, I seem to have given the term “author” much too

narrow a meaning. I have discussed the author only in the limited sense of a person to whom the production

of a text, a book, or a work can be legitimately attributed.” The useful components of Foucault’s model is

the observation of the flexibility of the idea of authorship to different aspects of the text and for different

deployments of it; while he mentions collective authorship—e.g., “the Church fathers”—he does not

address asymmetrical authorship, authorship within a production system, or the possibility of isolating

different aspects of the text and determining them as authorial.

10

experiences of these things in encapsulating terms. If someone were to say, “last night, I

played a game on my computer for three hours,” what do we imagine they’ve done?

What kind of time was spent in that activity? What sort of person—what sort of subject—

were they at the time they were playing? We can produce accounts of what it means to

read a book, especially a novel, an understanding based not simply on a social account of

reading, but of some engagement with a kind of text. We can do the same for someone

who goes to see a film, or even views a painting. These things aren’t stable or universal: a

contemporary schoolchild viewing a painting by Titian in a public museum is in a

different process of interpretation than that within the encounter by a 16

th

century

Austrian noblewoman with a portrait of Emperor Charles V hung in his own home for the

benefit of visitors in Augsburg. There may even be differences in the viewer’s

management of their own visual apparatus in each case: nonetheless, there is much that

connects the two experiences. Both are likely to understand the portrait as indexical, even

if they perceive different codes in each case.

It is less simple for our game player. We understood that they were doing

something we obliged them to be active somehow, but we also understand that they may

have experienced a narrative. If we ask them “what happened,” we could be told many

things: “I won,” “the villain was hiding in the castle,” “I got a high score,” “I unlocked a

level,” “nothing,” “I made some new friends and joined a clan,” “Dave cheated again,” “I

cried when my (the main character’s) child died,” “I played as Yoshi,” “the police framed

my friends for the murder, but I’m trying to find evidence that clears them,” “it turned out

I was responsible for the massacre,” “I helped some friends farm gold.” We could, in the

11

course of conversation, quickly establish the contexts of such explanations and induce

just what aspect of the activity was being presented in the recount, but it is striking how

many possible summaries of the outcome of the session of play could emerge—and all

the examples described can be described as originating in an encounter with the game as

a text. The transition from “what did you do?” to “what happened?” when asked of

someone who played a video game is the crossing of a chasm.

Game play—and the creation of games—is as old as anything human, and older.

Should we restrict ourselves to those games known from contemporary texts, and the play

of which is well understood, then the forerunners of the modern game of chess date back

at least to the Sassanid Empire (in modern-day Iran) in the beginning of the 7th century

CE, and possibly to the Gupta Empire (in modern-day northern India) at the end of the

6

th

. The earliest reference to the game we call Go is from the 4th century B.C.E., and

refers to an event in the year 548 B.C.E. A handful of physical artifacts or images of them

have been identified as ur-games older than these references: the Egyptian game of Senet

(c. 3100 BCE) and Mehen (c. 3000 BCE), the Mesopotamian Game of Ur (c. 2600 BCE),

Weiqi, Luobo and Chupu in China are interpreted as games with playable rules of one

sort or another. Even these conventional historical references are for systems of activities

that could be named, described and recorded: playful activity precedes human historical

memory: many animals recognizably play and cavort particularly in their juvenile stages,

and human play begins in infants before the production of speech.

12

Despite this hoary legacy, a premise of this chapter is that an important

discontinuity

6

occurs when a spectatorial media form becomes playable, when rules are

encoded into software to be executed in a computing platform

7

, and games become

discrete commodities or saleable services and experiences. The above description of the

antiquity of games is not meant to place the project of understanding the conditions under

which digital games are currently authored and interpreted within a universalized history

6

Although this dissertation privileges software-based game creation on the basis of the material

and ontological discontinuities that I describe, there are non-digital and hybrid-digital practices which are

historically and practically related. I will be discussing the complicated relationship between fiction and

mechanics in table-top role-playing games, and the relational-design elements of pervasive and alternative

reality games, in later chapters. In many cases, they prove the rule: the nature of inscription and the

productive systems of these forms are starkly different from the software-based variants. At the same time,

they also are influenced by the history of digital game design, and have similar issues regarding intellectual

property, incorporation of diegesis into game mechanics, participation in trans-media narrative franchises,

distributions of authorial labor, etc.

7

The question of “what is a computer” and “what is a platform” is a technical one. The latter

question is addressed in the formation of platform studies, esp. in Nick Montfort and Ian Bogost, Racing

the Beam: The Atari Video Computer System (Cambridge MA: The MIT Press, 2009). See also Nick

Montfort, “Combat in Context,” Game Studies 6, no. 1 (2006),

http://gamestudies.org/0601/articles/montfort/. A computer need not be physical: it can be emulated in

software. It also need not be electronic nor digital: the earliest games created for the computer were written

for analog computers, and Charles Babbage conceived of games of skill playable on his Analytical Engine:

see H. P Babbage, “Babbage’s Analytical Engine,” Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 70

(1910): 517–526.

13

of game design. There is, nonetheless, a precedent for describing the design of any

game—a board game, a team sport—as one involving authorship, particularly for games

with distinctive rhetorical heft. That a game have a designer or origins in a specific place

is an idea we can find in Herodotus, who attributed to Atys, king of the Lydians, a game

designed to help the populace cope with a famine, and to select a fraction of the kingdom

to emigrate and colonize the region of Tyresenia (later Etruria, center of the Etruscan

culture

,

8

.) In 16th century Spain, Alonso de Barros’ Filosofia cortesana, a moral treatise

for courtiers, included the design of a board game which illustrates the finer points of

navigating the complex patronage system of Phillip II as the navigation through the sea of

suffering to the riches of the new world

9

. The popular board game Monopoly was an

iteration of a game designed by Elizabeth Maggie as an illustration of the land tax theory

of Henry George

10

, and 20

th

and 21

st

century artists have created “playable rule-sets” and

board games

11

. There are many examples of the design of games and sports being

attributed to authors, artists and designers: the possibility of designing them in software

8

Herodotus and George Rawlinson, The Histories (Digireads.com Publishing, 2009), 31;

described in Jane McGonigal, Reality Is Broken: Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change

the World (Penguin, 2011), 5–9.

9

Harry Sieber, “The Magnificent Fountain: Literary Patronage in the Court of Philip III,”

Cervantes: Bulletin of the Cervantes Society of America 18, no. 2 (1998): 93.

10

Elizabeth Magie, “Game-Board (The Landlord Game)” (Brentwood, MD, January 5, 1904).

11

See especially Mary Flanagan, Critical Play: Radical Game Design (Cambridge, MA: MIT

Press, 2009), 63–116. I discuss some artist-designed games in chapter 3.

14

did not, in itself, create the possibility of an attributive relationship between a producer

and a game.

Yet the encoding of games into software is more than a simple translation, or even

a remediation, in the sense described by Grusin and Bolter

12

, by which current mediating

practice takes up and redeploys the work of the past, of a pre-digital form. Play forms did

not generally circulate as discrete mediated objects before they were captured into

software. Non-digital games are rule-driven practices managed socially and

institutionally: even the written rules of a game are more like a musical notation meant to

give guidance to a negotiation than they the rules themselves. In many games, the rules

are transmitted orally and by imitation and participation. The management of the rules,

their modification, suspension or augmentation becomes part of practice of a community

that plays.

13

A digital game moves those processes into software: the creation of

behaviors and design of representations to index those behaviors occurs when the

“representation” of a rule becomes the mechanism by which a rule is made actual as the

outcome of the working software (or when the operation produces its own representation

12

J David Bolter and Richard A Grusin, Remediation: Understanding New Media (Cambridge,

MA: MIT Press, 1999).

13

See, for example, Linda Hughes, “Beyond the Rules of the Game: Why Are Rooie Rules Nice?,”

in The World of Play: Proceedings of the 7th Annual Meeting of the Association of the Anthropological

Study of Play, ed. Frank E. Manning (West Point, NY: Leisure Press, 1983), 188–199. Hughes describes

how children play and adapt different rules of the playground game “Foursquare” depending on shifting

social and environmental conditions.

15

from within itself, as an effect of its computation.) There are borderline cases: e.g. table-

top war-gaming and simulation. What can be said of these cases is that other processes

are brought together in these liminal cases to roughly approximate what a digital game

implementation does easily: assembling material systems of representation (charts,

markers, figurines, landscape elements) to produce a visual system of playable fiction

that can maintain the state of the play and provide a basis for a system of calculation for

modifying it.

The determination of the category of “the game” has been a challenge for

ontology. Wittgenstein’s reflections on the nature of categorization, as not being a matter

of necessary and sufficient conditions (the Aristotelian definition of definition and model

of categorical membership) arose from the observation that there is no single feature

which all members which were element of the intuitively-understood set of “games” in

the English language shared; rather, categorical membership was a function of “family

resemblances,” a collection of features no one of which was either necessary or

sufficient, but which in aggregate would cause someone to recognize an activity or

artifact as a game.

14

Within game studies, a surprising amount of attention has continued

to be paid toward ontological questions (e.g, questions of “what is a game”, “what is a

14

Ludwig Wittgenstein et al., Philosophical Investigations (London: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009).

16

rule”, “what is a game fiction”)

15

,

16

often to establish a pedigree for the study of

videogames that would ground them in a much older “history of games.”

My motivation for revisiting these ontological questions is to reveal the

conditions of authorship for games and playable media

17

, and to do so in a manner that

does not privilege those genres and styles which clearly resemble forms for which those

conditions are already well-understood (i.e., those games which are at least superficially

similar to film, literature, etc.) Many conventional observations about videogames favor

one genre over another: presuming the existence, for example of an avatar or a narrative,

and implicitly exclude many games which are important to popular and critical discourses

of gaming. For a number of reasons, we cannot allow ourselves the luxury of a theory of

game authorship which arbitrarily deigns some works as ephemeral, especially when the

field of game production itself does not figure them as ephemeral.

15

Jesper Juul, Half-Real: Video Games Between Real Rules and Fictional Worlds (Cambridge,

MA: MIT Press, 2005).

16

Ian Bogost, Unit Operations: An Approach to Videogame Criticism (Cambridge, MA: MIT

Press, 2006).

17

This phrase drawn from the name of UC Santa Cruz’s department dedicated to research and

education in game design and game studies.

17

Play as signification and interpretation.

Play, including the play of animals, has already been described as an act of

meaning-making. The mid-century cultural historian Johan Huizinga

18

describes play as a

significant function, occurring within a “magic circle

19

,” a demarcated space-time

separate from and partially autonomous of daily life. Within this magic circle, things are

assigned new interpretations: a mound of dirt becomes a pitcher’s mound in baseball, a

stick becomes a wicket in cricket, fifteen minutes constitutes a quarter of play in hockey,

touching an individual transfers the designation of being “it” in a game of tag. For

Huizinga, this creation of provisional meaning is the foundation of culture; the

interpretation of phenomena, the creation of new units of meaning and structures of

signification, is prefigured by the play-function.

Huizinga describes the unstable relationship between play and seriousness: the

former referring simultaneously to the realization of the “pretend” nature of the act of

play and to the levity that accompanies that realization, the latter to the suspense of that

realization and the gravity of commitment to the “as-if” of play. This unstable

relationship associates “play” with ritual and theater, as forms of play with varying levels

and moments of self-awareness of the fictive nature of pretending. In distancing himself

18

Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture [1933] (Kansas City, MO: Beacon Press,

1955).

19

The term “magic circle” has become a term of art in game design to describe both an imagined

autonomy for play-activity and the system of rules and operations which constitute the basis of play. These

two senses are sometimes conflated.

18

from models of play which are explained in terms of human development, whether

phenotypical or cultural, he argues for an autonomous compulsion for play that makes it

always prior to any utility or purpose. The magic circle’s separation from the spatial

practices and marked times of everyday life can be taken to be over-stated: in game

studies, the figure of the “magic circle” is often targeted for criticism, construed as

excluding the contingencies which produce play and playful subjects. Despite this, he

never describes the relationship between play and its contexts as arbitrary.

Huizinga emphasized the spatial aspect of play, but the “magic circle” is a

conceptual space of signification (reminiscent of David Harvey’s idea of spaces of

representation, discussed later) in which the “separateness” that Huizinga claims is

essential to play is produced. The creation of a rule of play is a kind of speech-act: the

claim that a mound of dirt is “second base” as part of determining a region of space as a

baseball field is not expository or propositional, but as a perlocutionary and declarative

act: the production of the grounds for playing baseball. The provisional sign-creation

calls for an interpretation-creation, which is fulfilled by the activity of playing the game,

not in the establishment of an imaginary about “second base.”

While embracing Huizinga’s focus on play insisted on placing the play-

experience (as an aspect of the aesthetic) in the center of its own research project, Roger

Caillois

20

sought to create a taxonomy of games: he includes a range of practices which

20

Man, Play, and Games (New York: Free Press of Glencoe, 1961).

19

are “played” at, including lotteries, theater, ritual, skiing, (as a pleasurable activity) and

twirling. Caillois’ four-by-two matrix of game categories is an early case of an object-

centric perspective, treating particular games as cultural texts, rather describing play as

such in undifferentiated terms. Caillois proposed four categories of games: those of agon,

or competition and mastery; of alea, chance; of mimicry, or imitation, and of ilinx, or

vertigo.

21

Additionally, he places play along a graded axis between paidea and ludus: the

former is unstructured, spontaneous play in the manner associated with small children,

the latter being structured by explicit rules, restraint, institutions, and the regulation of

play. Spontaneous wrestling/tumbling matches between children is paidean agon, a

relatively unstructured, free-form play in which children establish who is stronger; a

state-run lottery is ludic alea, a highly regulated game-of-chance to select those who are

fortunate by no real effort on their own part.

Caillois’ categories continue to inform game studies work and theories of game

design. However, he is sometimes misunderstood as writing simply about games in

themselves, as if simply describing the rules of a game would be be enough to determine

its category. Instead, he is describing game-play as cultural performance, not games-as-

rules in the abstract. They could be better described as categories for cultural logics of

play. Caillois’ taxonomy fulfills a promise to Huizinga in this sense: each of these

21

Caillois does not exploit the distinctiveness of the English world “game,” and the object of the

predicate best translating “play” is jouer à un jeu - to play a played-thing: it can also be interpreted as

meaning “to act” (in a theatrical sense.)

20

categories is prior in play, at least conceptually, to the forms that the logics of these

categories assume in social and personal spheres, but the relationship between the game

as a formal system of rules and the game as the frame of play, as an interpreted and

interpreting cultural practice, is not well easily distinguished and requires us to observe

how the game is being used by its players.

As an example, the game of poker’s characterization as a game in Caillois’ system

is ambiguous. A description of the rules seems to make it difficult to interpret as a game

of mimicry—that is, as a game in which problems of identity and performance are being

worked. Nor is one likely to interpret the game of poker as one of ilinx, involving the

disorientation of the senses, playing with the ambiguity of senses and troubling the

phenomenological border between self and world. However, the two remaining

categories - agon and alea – are more viable candidates. While the mechanics of a game

can include elements from other categories, there is something exclusive about the logic

of play itself: the play of a game can by read as being underpinned by the need to resolve

one or another question. Agon occupies itself with mastery, with distinguishing the

virtuous player against rivals. The outcome of a game of agon reflects on the skill,

strength and cunning of the agonist. Alea, on the other hand, refers to chance; in Caillois’

interpretation, the chance elements of such games stand as synecdoche for the vagaries of

fate and the whims of deities; for the universe of realities, which are outside of human

effect or agency. If in playing a game of agon, a player is asking, “which one is the best?

Where is mastery? What is the value of my best efforts?” then a game of alea asks,

“What is my fate, my destiny? Do I enjoy divine favor?” To identify what cultural logic

21

is at work, one must see how the rules of the game are being interpreted by its players in

the context of play.

Many games, like poker, include elements both of chance and skill: the chance in

the fickleness of the cards as dealt; the skill in the exchange of bets to communicate and

to bluff, in the scrutiny of the player to discern the real situation of their opponents by

reading the signs of their countenances and bets. Its practitioners interpret poker as a

game of skill, over the course of a career, even if a single hand or series of hands may be

determined by chance. This is suggested by its professionalization, by the public

spectacles of televised poker matches, by a thriving niche of poker literature, by the

representations of poker players in film, television, and literature.

The professionalization of the sport notwithstanding, the legal status of poker in

the United States is often based on an interpretation of it as a game of chance. The

regulation of gaming (i.e., gambling) is generally left as a matter to state governments,

and without exception, the codes which regulate them distinguish between games of

chance and games of skill - essentially, between alea and agon - and restricts waging on

the former more aggressively than waging on the latter. The interpretation of the phrase

“game of chance” varies among jurisdictions: in some states, any element of chance is

enough to provide a basis for such a finding; in others, it is when chance is material to the

22

outcome of the game (which would, by most accounts, include poker.) In others, it is a

question of predominance

22

of the chance element.

A casual game of poker among amateurs - or against a computer system that bets

consistently based on ruled parameters - is a game of alea, as one simply hopes that the

cards which are distributed are favorable. Over time, the player’s relationship to the game

evolves: the cultivation of the player is a kind of apprenticeship in the relevant signs of

play, as the possible interpretations of signs within play expand to include signaling

behaviors, bluffs, etc. The player who learns these signs and how to produce (and avoid

producing) them no longer plays a game of chance, even if one hand or another’s

denouement is subject to the chance element. Such a player is an agonist, involved in a

competition to master the vocabulary of signs produced by the shuffle and deal of cars,

the bets, gestures and intonations of players, and their own affect and countenance. The

question, which is resolved by each hand of poker, for such a player, is about their own

abilities, not on their appointed destinies.

What this suggests is that the categorization of games proposed by Caillois—

agon, alea, mimicry and ilinx—are cultural logics of play, rather than simple categories

22

Information on legal status of poker from attorney Melinda Sarafan. The difference in legal

status between games of chance and of skill seems to be widespread; a Dutch court recently found online

poker to be a game of skill. It is interesting that Dutch law, as in many American states, reserves the right

to wager in games of chance to state-sponsored gambling, while wagering in games of skill is allowed to

the private sphere. See The Poker Law Bulletin for more.

23

for types of games. These logics are stances toward the interpretation of those signs

which are the basis of the play experience. The novice poker player plays a game of alea

because the signs to which he/she attends are those generated by stochastic processes;

they may bet literally, based on an appraisal of the value of the hand, hoping that others

have been less fortunate than he/she. The experienced player both attends to other signs

(the bets of other players and other cues about their intentions and beliefs) and interprets

the same signs

23

as the novice with a more deeply entrained system of interpretation (e.g.,

statistics based on known cards, etc.) Nonetheless, both players are playing the same

game; both adhere to the same rules of poker. Thus, the rules of poker themselves do not

determine the character of the play of poker in and of themselves.

That play is signification, and signification at the heart of play, was explored by

Gregory Bateson

24

, summarized in his oft-quoted observation, when considering the play

of young monkeys at a zoo, that “[t] he playful nip denotes the bite, but it does not denote

what would be denoted by the bite.”

25

For Bateson, play is predicated on meta-

communication: the session of play begins with the creation of an understanding among

23

In the Piercean sense of the material sign: some ambiguities regarding the application of

Piercean semiotics to games will be addressed later in this article.

24

Gregory Bateson, “A Theory of Play and Fantasy; a Report on Theoretical Aspects of the

Project of Study of the Role of the Paradoxes of Abstraction in Communication,” in Steps to an Ecology of

Mind, by Gregory Bateson (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1972), 177–193.

25

Ibid., 180.

24

its participants that the elements of play (the nip of monkeys) is not to be interpreted in

the same sense as usual: that they would become part of another articulation, referring to

the conventional interpretation of the bite, which denotes hostility, without denoting the

hostility itself. In playing, a fantasy world—a subjunctive world, in a way, suggesting the

“mental spaces” described by Gilles Fauconnier

26

—is co-produced by those who accept

the authority of the rules, for as long as they do. The collapse of the fantasy—the

evacuation of this provisional surplus signification—occurs when a player becomes a

spoil-sport, who, Huizinga says,

. . . shatters the play-world itself. By withdrawing from the game he

reveals the relativity and fragility of the play-world in which he had

temporarily shut himself with others. He robs the play of its illusion—a

pregnant word which means literally “in-play: (from inulsio, illudere or

inludere).

27

Both Huizinga and Bateson emphasize the priority of playful signification over its

mature forms: each sees juvenile play as the pre-condition for reference, for the

production of metaphor, for fiction, for ritual, and for abstraction.

26

Gilles Fauconnier, Mental Spaces: Aspects of Meaning Construction in Natural Language

(Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1994).

27

Huizinga, Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture [1933], 11.

25

Ludology and narratology

The study of games generally took place under the guise of cultural anthropology

and cultural history (e.g. Huizinga, Sutton-Smith

28

) sociology (Caillois) or psychology

(Bateson). Despite some early attempts to consider games themselves as material sign-

systems available for interpretation

29

(which, tellingly, began only after the digitization of

games) the play-activity has been the object of study for the social sciences, rather than

the humanities, Roland Barthes memorable interpretation of the cultural semiology of

professional wrestling notwithstanding.

30

The production and circulation of digital games afforded a new perception of

games as meaning-bearing, authored and received artifacts, and disciplines and methods

from other fields have taken them in as objects for study, interpretation and criticism. A

computer game is not simply the material complement to a game system, like a

chessboard or a football field or a deck of cars. It is even more than a documentation of

the rules of a game: it does not simply record the rules of a game in the way that a rule-

28

Sutton-Smith’s approach has been multidisciplinary: he has held important positions in the

American Psychological Association and has chaired the Anthropological Association for the study of play.

His initial work (B. Sutton-Smith and B. G. Rosenberg, “Sixty Years of Historical Change in the Game

Preferences of American Children,” The Journal of American Folklore 74, no. 291 (1961): 17–46.) was in

the field of cultural history.

29

Mary Ann Buckles, “Interactive Fiction: The Computer Storygame Adventure...” (Ph. D.

dissertation, University of California, San Diego, 1985).

30

Mythologies (New York: Hill and Wang, 1972), 15–27.

26

book might, but enacts at least some, and often most or close to all, in software.

31

When

games are software, it is simple to see the game as a Ding-an-sich, at least conceptually

autonomous from any instance of play, even if they are seldom encountered except

through play. Digital games include systems of signs and representations set into

material, circulated, and archived. If software has dematerialized practices of image

making, sound making, and the written word, it has in contrast materialized the

production and execution of game rules.

32

The discipline of game studies developed over the 1990s and early 2000s. Starting

with monographs by Brenda Laurel

33

, Janet Murray

34

and Espen Aarseth

35

, journals like

Game Studies – the International Journal of Computer Game Research (2001—present),

the Games and Culture Journal (2005—present) Loading… The Journal of the Canadian

31

The question of which rules are not enforced by software has been addressed elsewhere,

especially in Stephen Sniderman, “Unwritten Rules,” in The Game Design Reader : a Rules of Play

Anthology, ed. Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005), 476–502.

32

One can observe the long precedent of a material cultural of games – the design of boards and

tokens and cards and dice, the architecture of sports arenas and play areas, and the publication of rule

books, while recognizing the substantial discontinuity introduced by digital games.

33

Brenda Laurel, Computers as Theatre (Addison-Wesley Professional, 1993).

34

Janet Horowitz Murray, Hamlet on the Holodeck: The Future of Narrative in Cyberspace

(Simon and Schuster, 1997).

35

Espen Aarseth, Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins

University Press, 1997).

27

Game Studies Association (2007—present), and Eludamos — Journal for Computer

Game Culture (2007—present) published articles about games, media and culture by

scholars from a range of home disciplines. The Digital Games Research Association

formed in 2003 has become the major international body for games design research and

games studies, producing a biannual international conference since then. Other

conferences important in game studies include Digital Arts and Culture, Meaningful Play,

the International Conference on Entertainment Computing, the Foundations of Digital

Gaming, the Philosophy of Computer Games Conference and the State of Play

conference series (which deals with the relationship between games and law.) Game

programs at the undergraduate and graduate level have been created at hundreds of

universities and colleges: some of the most notable include Masters and PhD programs at

the IT University of Copenhagen, The Georgia Institute of Technology, and the

University of California, Santa Cruz.

Within this emergent discipline, a series of formal and informal discussions grew

into a divide between ludologists, researchers who focused on the study of games as such

and called for the creation of a family of conceptual frameworks and interpretative

methodologies unique to the study of games, and supposed narratologists. The latter term

was applied by those who self-identified as ludologists to characterize those theorists

whose disciplinary approaches drew from literary studies or film theory, and more

specifically for those whose interpretation of videogames foregrounded narrative, fiction

and representation over the behaviors of games as formal systems. While the gap between

the positions of its participants was perhaps exaggerated for rhetorical effect, the debate

28

provided much of the energy for the early years of the field.

36

The soi-disant ludologists

included Gonzalo Frasca, Jesper Juul (both of whom distanced themselves from the more

dramatic formulations of the distinction,) Marrku Eskelinen and Espen Aarseth. Aarseth

may have set the tone of the debate when describing the work of Murray and Laurel:

‘Games are always stories,’ Janet Murray claims. If this really were true,

perhaps professional baseball and football teams would do well to hire

narratologists as coaches. And does she also mean that stories are always

games, or are games simply a subcategory of stories? There were games

long before stories (among animals, long before human verbal culture), so

to privilege stories over games as a ‘core human activity,’ as Murray does,

may not be a good strategy if we want to understand games and make

them better.

37

This often-cited debate illustrates the ill-fitting attempts to understand digital

games in the context of the humanities. Early writing on interactive entertainment and its

possibilities, noting the performativity of the medium, often understood these forms

within the context of theater or film, yet the residence of meaning within digital games

never seemed straightforward. The vicissitudes of the debate are less relevant than their

apparent denouement; game studies seem, superficially, to have dispensed with the need

to reduce the object of its analysis to one of its features. Nonetheless, the apparent

36

“Narratology is a category of interest to the computer game formalists. It represents the

authority against which they have rebelled.” - Gonzalo Frasca, “Ludologists Love Stories, Too: Notes from

a Debate That Never Took Place,” in Level Up Conference Proceedings (presented at the DiGRA 2003,

Utrecht: University of Utrecht, 2003), 92–99, http://www.digra.org/dl/db/05163.01125.

37

Espen Aarseth, “Espen Aarseth Responds,” Electronic Book Review, May 1, 2004,

http://www.electronicbookreview.com/thread/firstperson/cornucopia.

29

decompression of the debate has not the problem of the relationship between the game as

a system of representation and as a rule-system: often, discussion on games in the wake

of the debate begins with recognition of the value and importance of the absent element.

In practice, however, criticisms isolate and privilege one element and pay only passing

respect to the other. Of the over 130 papers presented at the 2009 conference of the

Digital Game Research Association, about 30 could be said to be primarily based on the

reading or analysis of the game as a cultural artifact (rather than being ethnographic

studies, psychological and cognitive theories of play, design and engineering research,

etc.) Of these, about half privileged representational elements and relegated mechanical

and game-dynamical elements to the background, while the other half did the opposite.

Only Ian Bogost's keynote address at the 2009 Digital Games Research Association

conference, "Videogames are a mess," suggested an ontology which is resonant with the

temporal experience of play, proposing that games were irreducible to any one of their

features or frames of interpretation, and that a state of permanent bricolage was the best

critical stance for a game scholar.

Murray distinguished between a discipline of ludology as a term to describe the

study of games themselves, and a position she described as game essentialism, by which

all signifying elements of the game should only be read as tokens in formal game

systems

38

. Many ludologists did, in fact, seem to thus emphasize the continuities between

38

J. H Murray, “The Last Word on Ludology v Narratology in Game Studies,” in DiGRA 2005

Conference: Changing Views of Worlds in Play, 2005.

30

pre-digital and digital game design and play: little has been made (other than a passing

observation by Juul

39

) of the fact that, despite the antiquity of games, they have only

recently been made the object of the kind of critical inquiry we associate with other

cultural forms. Juul and others observe that computers are “very good” at managing rules,

and thus it is natural that game design and play migrate to computers. The idea that

computers are also channels of communication, engines of mediation and representation,

was overlooked.

Aarseth

40

distinguished between the (mostly) non-electronic and (mostly)

electronic literatures by seen the latter as ergodic: as a system which lay behind the

visible text. In Aarseth’s model, an ergodic text is one in which a distinction can be made

between scriptions, or strings of words and characters as they appear to the reader, an

textons, strings as they exist, latent, within the text. Not all ergodic texts are electronic:

Aarseth identifies the I Ching and the “calligrammes” of Guillaume Apollinaire as

ergodic texts.

41

As I am taking a broader sense of the sign than Aarseth does, including

visual, architectural, and even relational objects as signs which are “written” into the

games, I also identify certain other game-design practices as resembling the dual-nature

of the digital game more than the socially-maintained nature of most non-digital games.

If the “scripton” is too Saussurean, too literary, to explain the kinds of signs encountered

39

Juul, Half-Real, 21.

40

Aarseth, Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature.

41

Ibid., 9–10.

31

within a videogame, it is still useful to consider the distinction between the signs read by

the player and those within the system—either lying in wait for a possible but not

inevitable exposure to the player, or those which are designed internally, to be read by the

system itself, whatever its origin. The system does more than simply hold in reserve

signs, awaiting the reader’s prompt: it is reading the reader, producing its own model of

the reader/player’s intentions, disposition, and symbolic production.

42

Revisiting semiotics in interactive media

If we return to the moment in which someone tells us that, the day before, they

had played a videogame, there are some things we can say with reasonable confidence.

We know that they executed at least one instance of software on a computer, loaded from

some kind of storage (either on the computer or game console they have at hand, or one

on a remote server); that the software’s operation produced representations which the

player interpreted, and that the player responded to these interpretations to provide input

back to the game system’s processor; the processor interpreted these inputs as the

participation of the player into the game. Perhaps other players were doing the same, and

responding to signs generated by the computer’s response to the player’s input (and

identifying those signs as the player, making the mediation of the computer transparent.)

42

Douglas Engelbart’s work developing the core concepts for human-computer interaction in the

1960’s was based on this perspective. See Susan B. Barnes, “Douglas Carl Engelbart: Developing the

Underlying Concepts for Contemporary Computing,” IEEE Annals of the History of Computing 19, no. 3

(1997): 19–20.

32

Perhaps other players were in the same location as the player, and the signs which they

interpreted included those produced by each other: shouts, gestures, stares etc.

Much else may have also happened, in the subjective experience of the player,

among people with whom they were playing, in the computer systems, on the network to

which the computer was connected, and among players also connected to that network.

But I will argue that the basis of the player’s engagement with the digital game is the

interpretation of a stream of signs, almost always in the visual and usually in the audio

field, and sometimes in the haptic and proprioceptic ones. And at least some of those

signs, and often most, were encoded into the system in the game development process as

digital code. Visual signs include everything from icons, strings of text and numbers

(labels, scores, names, messages from other players, subtitles, intertitles), particle effects

indicating a dynamic process (an explosion, motion, impact), a 3-dimensional figure of a

human-like or animal-like character, a stylized red cross (indicating “health” in many

games, part of a complex convention alluding to an internal state in the system,) and

much more; the audio signs can be sound effects, music, speech (perhaps generated by

other players.) In digital game and in game-like interactive media, the dynamics between

these signs as the objects of interpretation by the player and as authored elements placed

within the software in the development process distinguish them from the kind of signs

interpreted by cinema audiences or readers of (non-ergodic) novels.

To develop a useful theory of the sign for interactive media, it is helpful to return

to the origin of semiotics and to clear away possible presumptions about its limits and

application. The two authors credited with the development of semiotics, Ferdinand de

33

Saussure (1857—1913) and Charles S. Peirce (1839—1914), each approach the problem

of the sign from the perspective of the problematics of their own disciplines.

Saussuaure’s model reflects a linguistic set of concerns focused on signification as a