Strategy to Pre vent the Importatio n of Goods M ined, Produced, or Manufac tured with Forc ed Labor

Strategy to Prevent the Importation of

Goods Mined, Produced, or

Manufactured with Forced Labor in the

People’s Republic of China

Report to Congress

June 17, 2022

Office of Strategy, Policy, and Plans

i

Message from the Under Secretary for Strategy,

Policy, and Plans

June 17, 2022

The United States is committed to promoting respect for human rights

and dignity and supporting a system of global trading free from forced

labor. As the Chair of the Forced Labor Enforcement Task Force

(FLETF), and on behalf of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security

(DHS), I am pleased to present to Congress this “Strategy to Prevent

the Importation of Goods Mined, Produced, or Manufactured with

Forced Labor in the People’s Republic of China.” Additional members

of the FLETF include the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative and

the U.S. Departments of Commerce, Justice, Labor, State, and the

Treasury. The U.S. Departments of Agriculture and Energy, the U.S.

Agency for International Development, U.S. Customs and Border

Protection, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, and the

National Security Council participate as FLETF observers.

This strategy has been prepared by the FLETF, in consultation with the U.S. Department of

Commerce and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, pursuant to Section 2(c) of

Public Law No. 117-78, an Act to ensure that goods made with forced labor in the Xinjiang Uyghur

Autonomous Region of the People’s Republic of China do not enter the United States market, and

for other purposes, otherwise known as the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act. This report

reflects public input received in response to a Federal Register notice published on January 24,

2022 and during a public hearing held on April 8, 2022.

Ending forced labor is a moral, economic, and national security imperative. DHS and its FLETF

partners remain steadfast in their duty to address the global challenge of prohibiting the

importation of goods mined, produced, or manufactured wholly or in part with forced labor.

Combating trade in illicit goods produced with forced labor, including government-sponsored

forced labor or convict labor, protects against unfair competition for compliant U.S. and

international manufacturers and promotes American values of free and fair trade, the rule of law,

and respect for human dignity.

Pursuant to Pub. L. No. 117-78, this report will be made publicly available and is being submitted

to relevant congressional committee leaders listed below:

The Honorable Gregory Meeks, Chairman

U.S. House of Representatives Foreign Affairs Committee

The Honorable Michael McCaul, Ranking Member

U.S. House of Representatives Foreign Affairs Committee

The Honorable Maxine Waters, Chairwoman

U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Financial Services

ii

The Honorable Patrick McHenry, Ranking Member

U.S. House Committee on Financial Services

The Honorable Richard Neal, Chair

U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Ways and Means

The Honorable Kevin Brady, Ranking Member

U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Ways and Means

The Honorable Bennie G. Thompson, Chairman

U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Homeland Security

The Honorable John Katko, Ranking Member

U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Homeland Security

The Honorable Bob Menendez, Chairman

U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations

The Honorable James E. Risch, Ranking Member

U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations

The Honorable Sherrod Brown, Chairman

U.S. Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs

The Honorable Patrick J. Toomey, Ranking Member

U.S. Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs

The Honorable Ron Wyden, Chairman

U.S. Senate Committee on Finance

The Honorable Mike Crapo, Ranking Member

U.S. Senate Committee on Finance

The Honorable Gary C. Peters, Chairman

U.S. Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs

The Honorable Rob Portman, Ranking Member

U.S. Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs

Sincerely,

Robert Silvers

Under Secretary for Strategy, Policy, and Plans

U.S. Department of Homeland Security

iii

Executive Summary

The Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act

1

(UFLPA) was enacted on December 23, 2021, to

strengthen the existing prohibition against the importation of goods made wholly or in part with

forced labor into the United States and to end the systematic use of forced labor in the Xinjiang

Uyghur Autonomous Region (Xinjiang). Among its mandates, the UFLPA charged the Forced

Labor Enforcement Task Force (FLETF), chaired by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security

(DHS), to develop a strategy for supporting the enforcement of Section 307 of the Tariff Act of

1930, as amended (19 U.S.C. § 1307) to prevent the importation into the United States of goods

mined, produced, or manufactured wholly or in part with forced labor in the People’s Republic

of China (PRC).

This strategy incorporates input from various public and private-sector stakeholders. It

incorporates significant contributions from FLETF members and observers and takes into

account public comments received through the FLETF’s Federal Register request for information

and the UFLPA public hearing.

2

Pursuant to the UFLPA, this strategy includes:

• A comprehensive assessment of the risk of importing goods mined, produced, or

manufactured, wholly or in part, with forced labor in the PRC;

• An evaluation and description of forced-labor schemes, UFLPA-required lists (including the

UFLPA Entity List), UFLPA-required plans, and high priority sectors for enforcement;

• Recommendations for efforts, initiatives, tools, and technologies to accurately identify and

trace affected goods;

• A description of how U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) plans to enhance its use of

legal authorities and tools to prevent entry of goods at U.S. ports in violation of 19 U.S.C. §

1307;

• A description of additional resources necessary to ensure no goods made with forced labor

enter U.S. ports;

• Guidance to importers; and

• A plan to coordinate and collaborate with appropriate nongovernmental organizations

(NGOs) and private-sector entities.

1

Pub. L. No. 117-78, 135 Stat. 1525 (2021).

2

See Notice Seeking Public Comments on Methods to Prevent the Importation of Goods Mined, Produced, or

Manufactured with Forced Labor in the People’s Republic of China, Especially in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous

Region, Into the United States, 87 Fed. Reg. 3567 (Jan. 24, 2022); Notice of Public Hearing on the Use of Forced

Labor in the People’s Republic of China and Measures to Prevent the Importation of Goods Produced, Mined, or

Manufactured, Wholly or in Part, With Forced Labor in the People’s Republic of China Into the United States, 87

Fed. Reg. 15448 (Mar. 18, 2022); Nonrulemaking Docket: Notice of Public Hearing on the Use of Forced Labor in

the People’s Republic of China and Measures to Prevent the Importation of Goods Produced, Mined, or

Manufactured, Wholly or in Part, With Forced Labor in the People’s Republic of China Into the United States,

Regulations.gov, https://www.regulations.gov/docket/DHS-2022-0001 (last visited May 19, 2022) (containing

public comments submitted in response to 87 Fed. Reg. 3567 and a transcript of verbal testimony from the hearing

on April 8, 2022).

iv

Assessment of the Risk of Importing Goods Mined, Produced, or Manufactured with

Forced Labor in the People’s Republic of China

The assessment addresses the risk of importing goods made with forced labor in the PRC, threats

that may lead to the importation of forced labor-made goods from the PRC, and procedures to

reduce such threats. Complex supply chains that touch Xinjiang are highly susceptible to

contamination by goods made using forced labor. Threats that amplify the risk of such goods in

U.S. supply chains include lack of supply chain visibility, commingling inputs made with forced

labor into otherwise legitimate production processes, import prohibition evasion, and forced

labor practices that target vulnerable populations within the PRC.

Securing U.S. supply chains against forced labor will require cooperation across stakeholders,

including industry, civil society, and federal agencies. All entities whose supply chains touch

Xinjiang should undertake due diligence measures to ensure compliance with U.S. laws and trace

their supply chains for potential exposure to forced labor.

Evaluation and Description of Forced-Labor Schemes and UFLPA Entity List

The evaluation of labor schemes and the UFLPA Entity List provides an overview of PRC-

sponsored labor programs that include forced labor by Uyghurs and other persecuted groups;

lists of entities, products, and high-priority sectors affiliated with forced labor in the PRC; and

U.S. department and agency enforcement plans related to the lists. Forced labor in internment

camps and other labor schemes remain a central PRC tactic for the repression of Uyghurs,

Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, Tibetans, and members of other persecuted groups. The possibility of

internment in these labor programs functions as an explicit or implicit threat to compel members

of persecuted minorities to work. In some cases, workers are transferred directly from detention

to factories in and outside of Xinjiang. Even when workers in these programs are not transferred

directly from internment camps, their work is the product of forced labor. They do not undertake

the labor with free and informed consent and are not free to leave; they are subject to

discriminatory social control, including pervasive surveillance, and the threat of detention.

3

UFLPA Section 2(d)(2)(B) requires the strategy to include: (i) entities in Xinjiang that produce

goods using forced labor; (ii) entities that work with the Xinjiang government to recruit,

transport, transfer, harbor, or receive forced labor or Uyghurs, Kazakhs, Kyrgyz or members of

other persecuted groups out of Xinjiang; (iii) products made by entities in lists (i) and (ii); (iv)

entities that export products identified in (iii) from the PRC to the United States; and (v) entities

and facilities that source material from Xinjiang or from persons working with the Xinjiang

government or the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (XPCC) for purposes of any

government-labor scheme that uses forced labor. Goods from these entities will be subject to the

UFLPA rebuttable presumption under 19 U.S.C. § 1307. Furthermore, this strategy includes

high-priority sectors for enforcement, and FLETF enforcement plans and plans to identify

additional entities associated with these labor schemes in the future.

3

See e.g., Amy K. Lehr, Addressing Forced Labor in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region: Towards a Shared

Agenda, Ctr. for Strategic & Int’l Studies, 1-2 (July 30, 2020), https://www.csis.org/analysis/addressing-forced-

labor-xinjiang-uyghur-autonomous-region-toward-shared-agenda.

v

Recommended Efforts, Initiatives, Tools, and Technologies to Accurately Identify and

Trace Goods

The strategy outlines several recommendations for efforts, initiatives, tools, and technologies that

CBP will adopt to identify and trace goods made with forced labor. CBP will procure cutting-

edge technologies that provide improved visibility into trade networks, and that improve supply-

chain tracing to identify goods made wholly or in part with forced labor. CBP will improve its

existing enterprise automated systems to increase data quality and communication to enhance

both forced labor enforcement actions and processes that facilitate lawful trade. Finally, CBP

will expand collaboration with interagency partners and leverage existing U.S. government tools.

CBP Enhancement of Use of Legal Authorities and Tools to Prevent Entry of Goods at U.S.

Ports in Violation of 19 U.S.C. § 1307

This strategy also provides a description of how CBP plans to enhance its use of legal authorities

to prevent the importation of goods prohibited by 19 U.S.C. § 1307. CBP will consider

enhancing its use of its detention and exclusion authorities under 19 U.S.C. § 1499, and seizure

authorities under 19 U.S.C. § 1595a(c). CBP will consider other regulatory changes that will

allow CBP to respond more quickly to forced labor allegations, provide importers with clear

guidance on admissibility determination timeframes, and provide a more uniform process for the

determination of merchandise admissibility. Overall, the plan to enhance use of authorities and

tools will provide for a more effective and efficient enforcement of 19 U.S.C. § 1307.

Additional Resources Necessary to Ensure No Goods Made with Forced Labor Enter U.S.

Ports

This section highlights additional resources required to administer and implement the UFLPA.

FLETF agencies must manage existing resources effectively, identify resource shortfalls, and

adequately resource implementation of this enforcement strategy, not only through direct

operational requirements but also through policy, management, and oversight. This section

outlines what will be required by the FLETF Chair, the DHS Office of Strategy, Policy, and

Plans (PLCY); CBP; and U.S. Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE) Homeland

Security Investigations (HSI).

Guidance to Importers

The UFLPA establishes a rebuttable presumption that goods mined, produced, or manufactured

wholly or in part in Xinjiang or by an entity on the UFLPA Entity List are prohibited from U.S.

importation under 19 U.S.C. § 1307. If an importer of record can demonstrate by clear and

convincing evidence that the goods in question were not produced wholly or in part by forced

labor, fully respond to all CBP requests for information about goods under CBP review, and

demonstrate that it has fully complied with the guidance outlined in this strategy, the

Commissioner of CBP may grant an exception to the presumption. Within 30 days of any

determination to grant an exception, the Commissioner of CBP must submit to Congress and

make available to the public a report outlining the evidence supporting the exception.

vi

As mandated by the UFLPA, this report’s guidance includes information on three topics: (1) due

diligence, effective supply-chain tracing, and supply-chain management measures to ensure that

such importers do not import any goods produced wholly or in part with forced labor from the

PRC, especially from Xinjiang; (2) the type, nature, and extent of evidence that demonstrates

that goods originating in the PRC were not produced wholly or in part in Xinjiang; and (3) the

type, nature, and extent of evidence that demonstrates that goods originating in the PRC,

including goods detained, excluded or seized for violations of the UFLPA, were not produced

wholly or in part with forced labor.

Coordination and Collaboration with Appropriate Nongovernmental Organizations and

Private-Sector Entities

Finally, the strategy features the FLETF’s plan to coordinate with appropriate NGOs and private-

sector entities to implement and update this strategy. The FLETF will continue to engage with

NGOs and the private sector on UFLPA implementation and to host joint-interagency meetings

with NGOs and the private sector to discuss enforcement and trade facilitation opportunities. The

FLETF will institute biannual working-level meetings with both private-sector and NGO

partners on the UFLPA strategy. Finally, the FLETF will establish a dhs.gov webpage that will

include information on the FLETF, public reports issued by the FLETF, and a compiled list of

FLETF agency resources to address forced labor concerns, as well as resources related to the

presence of forced labor in U.S. supply chains and mitigating the risk of forced labor in global

supply chains.

Path Forward

This strategy outlines the FLETF’s recommendations for fully implementing the UFLPA’s

mandates in accordance with congressional intent to ensure U.S. supply chains are free of forced

labor based in the PRC, especially forced labor by Uyghurs, Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, Tibetans, and

members of other persecuted groups in the PRC. The strategy should be implemented in a way

that strengthens U.S. supply chains and prioritizes long-term U.S. economic security.

vii

Strategy to Prevent the Importation of Goods Mined,

Produced, or Manufactured with Forced Labor in the

People’s Republic of China

Table of Contents

Statutory Language ...................................................................................................................... 1

Background ..................................................................................................................................... 6

UFLPA Strategy………………………………………………………………………………...11

I. Assessment of the Risk of Importing Goods Mined, Produced, or Manufactured with Forced

Labor in the People’s Republic of China ...................................................................................... 10

II. Evaluation and Description of Forced-Labor Schemes and UFLPA Entity List ..................... 18

III. Efforts, Initiatives, Tools, and Technologies to Accurately Identify and Trace Goods ......... 31

IV. CBP Enhancement of the Use of Legal Authorities and Tools to Prevent Entry of Goods in

Violation of 19 United States Code 1307 at U.S. Ports ................................................................ 34

V. Additional Resources Necessary to Ensure No Goods Made with Forced Labor Enter at U.S.

Ports .............................................................................................................................................. 35

VI. Guidance to Importers ............................................................................................................ 40

VII. Coordination and Collaboration with Appropriate Nongovernmental Organizations and

Private-Sector Entities .................................................................................................................. 52

Conclusion ................................................................................................................................... 58

Appendix A - Acronyms ............................................................................................................... 59

Appendix B – Public Perspective on FLETF Collaboration Opportunities .................................. 60

Organization of Report

This report begins with an introduction, including the UFLPA’s statutory language and

background on the FLETF. Sections I through VII correspond directly to each of the UFLPA’s

requirements described in 1 through 7 of Section 2(c) of Pub. L. No. 117-78. A conclusion and

appendices complete the strategy.

1

Statutory Language

Section 2(c) of Public Law 117-78, An Act [t]o ensure that goods made with forced labor in the

Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of the People’s Republic of China do not enter the United

States market, and for other purposes, also known as the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act

(UFLPA), requires that “the Forced Labor Enforcement Task Force, in consultation with the

Secretary of Commerce and the Director of National Intelligence, shall develop a strategy for

supporting enforcement of Section 307 of the Tariff Act of 1930 (19 U.S.C. 1307) to prevent the

importation into the United States of goods mined, produced, or manufactured wholly or in part

with forced labor in the People’s Republic of China.”

The UFLPA requires that the FLETF solicit public comments and host a public hearing, as

described in Sections 2(a) and 2(b):

(a) PUBLIC COMMENT. —

(1) IN GENERAL.— Not later than 30 days after the date of the enactment of this Act, the

Forced Labor Enforcement Task Force, established under section 741 of the United

States-Mexico-Canada Agreement Implementation Act (19 U.S.C. 4681), shall publish in

the Federal Register a notice soliciting public comments on how best to ensure that goods

mined, produced, or manufactured wholly or in part with forced labor in the People’s

Republic of China, including by Uyghurs, Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, Tibetans, and members of

other persecuted groups in the People’s Republic of China, and especially in the Xinjiang

Uyghur Autonomous Region, are not imported into the United States.

(2) PERIOD FOR COMMENT.— The Forced Labor Enforcement Task Force shall provide the

public with not less than 45 days to submit comments in response to the notice required

by paragraph (1).

(b) PUBLIC HEARING.—

(1) IN GENERAL.— Not later than 45 days after the close of the period to submit comments

under subsection (a)(2), the Forced Labor Enforcement Task Force shall conduct a public

hearing inviting witnesses to testify with respect to the use of forced labor in the People’s

Republic of China and potential measures, including the measures described in paragraph

(2), to prevent the importation of goods mined, produced, or manufactured wholly or in

part with forced labor in the People’s Republic of China into the United States.

(2) MEASURES DESCRIBED. — The measures described in this paragraph are—

(A) measures that can be taken to trace the origin of goods, offer greater supply chain

transparency, and identify third country supply chain routes for goods mined,

produced, or manufactured wholly or in part with forced labor in the People’s

Republic of China; and

2

(B) other measures for ensuring that goods mined, produced, or manufactured wholly

or in part with forced labor do not enter the United States.

UFLPA Section 2(c) requires the FLETF to develop a strategy to support enforcement of Section

307 of the Tariff Act of 1930 to prevent the importation into the United States of goods mined,

produced, or manufactured wholly or in part with forced labor in the PRC; Section 2(d) outlines

the required content of the strategy:

(c) DEVELOPMENT OF STRATEGY.— After receiving public comments under subsection (a) and

holding the hearing required by subsection (b), the Forced Labor Enforcement Task Force, in

consultation with the Secretary of Commerce and the Director of National Intelligence, shall

develop a strategy for supporting enforcement of Section 307 of the Tariff Act of 1930 (19

U.S.C. § 1307) to prevent the importation into the United States of goods mined, produced,

or manufactured wholly or in part with forced labor in the People's Republic of China.

(d) ELEMENTS. — The strategy developed under subsection (c) shall include the following:

(1) A comprehensive assessment of the risk of importing goods mined, produced, or

manufactured wholly or in part with forced labor in the People’s Republic of China,

including from the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region or made by Uyghurs, Kazakhs,

Kyrgyz, Tibetans, or members of other persecuted groups in any other part of the

People’s Republic of China, that identifies, to the extent feasible—

(A) threats, including through the potential involvement in supply chains of entities

that may use forced labor, that could lead to the importation into the United States

from the People’s Republic of China, including through third countries, of goods

mined, produced, or manufactured wholly or in part with forced labor; and

(B) what procedures can be implemented or improved to reduce such threats.

(2) A comprehensive description and evaluation—

(A) of ‘‘pairing assistance’’ and ‘‘poverty alleviation’’ or any other government labor

scheme that includes the forced labor of Uyghurs, Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, Tibetans, or

members of other persecuted groups outside of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous

Region or similar programs of the People’s Republic of China in which work or

services are extracted from Uyghurs, Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, Tibetans, or members of

other persecuted groups through the threat of penalty or for which the Uyghurs,

Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, Tibetans, or members of other persecuted groups have not

offered themselves voluntarily; and

3

(B) that includes—

(i) a list of entities in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region that mine,

produce, or manufacture wholly or in part any goods, wares, articles and

merchandise with forced labor;

(ii) a list of entities working with the government of the Xinjiang Uyghur

Autonomous Region to recruit, transport, transfer, harbor or receive forced labor

or Uyghurs, Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, or members of other persecuted groups out of the

Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region;

(iii) a list of products mined, produced, or manufactured wholly or in part by

entities on the list required by clause (i) or (ii);

(iv) a list of entities that exported products described in clause (iii) from the

People’s Republic of China into the United States;

(v) a list of facilities and entities, including the Xinjiang Production and

Construction Corps, that source material from the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous

Region or from persons working with the government of the Xinjiang Uyghur

Autonomous Region or the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps for

purposes of the ‘‘poverty alleviation’’ program or the ‘‘pairing-assistance’’

program or any other government labor scheme that uses forced labor;

(vi) a plan for identifying additional facilities and entities described in clause (v);

(vii) an enforcement plan for each such entity whose goods, wares [sic] articles,

or merchandise are exported into the United States, which may include issuing

withhold release orders to support enforcement of section 4 with respect to the

entity;

(viii) a list of high-priority sectors for enforcement, which shall include cotton,

tomatoes, and polysilicon; and

(ix) an enforcement plan for each such high-priority sector.

(3) Recommendations for efforts, initiatives, and tools and technologies to be adopted to

ensure that U.S. Customs and Border Protection can accurately identify and trace goods

made in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region entering at any of the ports of the

United States.

(4) A description of how U.S. Customs and Border Protection plans to enhance its use of

legal authorities and other tools to ensure that no goods are entered at any of the ports of

the United States in violation of section 307 of the Tariff Act of 1930 (19 U.S.C. 1307),

4

including through the initiation of pilot programs to test the viability of technologies to

assist in the examination of such goods.

(5) A description of the additional resources necessary for U.S. Customs and Border

Protection to ensure that no goods are entered at any of the ports of the United States in

violation of section 307 of the Tariff Act of 1930 (19 U.S.C. 1307).

(6) Guidance to importers with respect to—

(A) due diligence, effective supply chain tracing, and supply chain management

measures to ensure that such importers do not import any goods mined, produced, or

manufactured wholly or in part with forced labor from the People’s Republic of

China, especially from the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region;

(B) the type, nature, and extent of evidence that demonstrates that goods originating

in the People’s Republic of China were not mined, produced, or manufactured wholly

or in part in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region; and

(C) the type, nature, and extent of evidence that demonstrates that goods originating

in the People’s Republic of China, including goods detained or seized pursuant to

section 307 of the Tariff Act of 1930 (19 U.S.C. 1307), were not mined, produced, or

manufactured wholly or in part with forced labor.

(7) A plan to coordinate and collaborate with appropriate nongovernmental organizations

and private sector entities to implement and update the strategy developed under

subsection (c).

UFLPA Section 2(e) outlines the timeline for the initial report and frequency of subsequent

updates to the strategy:

(e) SUBMISSION OF STRATEGY.—

(1) IN GENERAL.— Not later than 180 days after the date of the enactment of this Act, and

annually thereafter, the Forced Labor Enforcement Task Force, in consultation with the

Department of Commerce and the Director of National Intelligence, shall submit to the

appropriate congressional committees a report that —

(A) in the case of the first such report, sets forth the strategy developed under

subsection (c); and

(B) in the case of any subsequent such report, sets forth any updates to the strategy.

(2) UPDATES OF CERTAIN MATTERS.— Not less frequently than annually after the

submission under paragraph (1)(A) of the strategy developed under subsection (c), the

Forced Labor Enforcement Task Force shall submit to the appropriate congressional

5

committees updates to the strategy with respect to the matters described in clauses (i)

through (ix) of subsection (d)(2)(B).

(3) FORM OF REPORT. — Each report required by paragraph (1) shall be submitted in

unclassified form, but may include a classified annex, if necessary.

(4) PUBLIC AVAILABILITY.— The unclassified portion of each report required by paragraph

(1) shall be made available to the public.

UFLPA Section 2(f) outlines that nothing in the UFLPA legislation or in this report will be

construed to limit the application of regulations or actions taken before UFLPA enactment, that

is, before December 23, 2021:

(f) RULE OF CONSTRUCTION.— Nothing in this section may be construed to limit the

application of regulations in effect on or measures taken before the date of the enactment of

this Act to prevent the importation of goods mined, produced, or manufactured wholly or in

part with forced labor into the United States, including withhold release orders issued before

such date of enactment.

6

Background

Section 1307 of Title 19, United States Code, prohibits goods, wares, articles, and merchandise

mined, produced, or manufactured wholly or in part in any foreign country by forced labor from

being imported into the United States, including convict labor, indentured labor under penal

sanctions, and forced or indentured child labor. CBP enforces this prohibition while facilitating

legitimate trade at 328 ports of entry throughout the United States. CBP has authority to detain,

seize, or exclude goods produced with forced labor, as well as to issue civil penalties against

those who facilitate such imports.

4

Establishment of the FLETF

The FLETF was authorized on January 29, 2020 by the United States-Mexico-Canada

Agreement (USMCA) Implementation Act (19 U.S.C. § 4681). Executive Order 13923, signed

May 15, 2020, established the FLETF and identified the Secretary of Homeland Security as its

Chair. The Secretary delegated the role of FLETF Chair to the Under Secretary for Strategy,

Policy, and Plans. The FLETF’s additional members are the Office of the U.S. Trade

Representative (USTR) and the U.S. Departments of Commerce (DOC), Justice (DOJ), Labor

(DOL), State (DOS), and the Treasury (Treasury). The U.S. Departments of Agriculture and

Energy, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), CBP, ICE, and the National

Security Council participate as observers.

5

Role of the FLETF

The FLETF is responsible for monitoring the enforcement of 19 U.S.C. § 1307. The FLETF

convenes quarterly leadership meetings and coordinates amongst its members to fulfill its

mission. The FLETF provides biannual reports to Congress that include information and

statistics related to CBP’s enforcement of 19 U.S.C. § 1307 and plans regarding goods included

in DOL’s Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor report

6

and List of Goods Produced by

Child Labor or Forced Labor report.

7

Forced Labor in Xinjiang and the UFLPA

The United States condemns the PRC’s violations and abuses of human rights in Xinjiang. The

PRC government engages in genocide and crimes against humanity against predominantly

4

19 U.S.C. §§ 1592, 1595a.

5

The FLETF Chair has the authority to invite agencies and departments to participate as members or observers, as

appropriate.

6

DOL’s Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor report is submitted in accordance with the requirements for an

annual report per section 504 of the Trade Act of 1974, as amended (19 U.S.C. § 2464).

7

DOL’s List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor report is submitted to Congress and made

publicly available at least every two years in accordance with section 105(b)(2)(C) of the Trafficking Victims

Protection Reauthorization Act of 2005 (22 U.S.C. § 7112(b)(2)(C)).

7

Muslim Uyghurs and members of other ethnic and religious minority groups in Xinjiang.

8

Crimes against humanity include imprisonment, torture, forced sterilization, and persecution,

including through forced labor and the imposition of draconian restrictions on the freedom of

religion or belief, expression, and movement.

9

Congress enacted the UFLPA to highlight these

abhorrent practices, combat the PRC’s systematic use of forced labor in Xinjiang, and prevent

goods produced in whole or in part by this repressive system from entering the United States.

Enforcement Actions Prior to the Implementation of the UFLPA

The U.S. government has undertaken significant efforts to mitigate the use of forced labor in

Xinjiang, including by identifying and targeting specific entities and products affiliated with

forced labor and publishing reports highlighting the risks of forced labor in supply chains. Since

2019, CBP has issued Withhold Release Orders

10

(WROs) on specific goods from nine PRC

companies using government-sponsored forced labor,

11

on cotton from the XPCC, and on all

Xinjiang cotton and tomatoes and all downstream products using Xinjiang cotton and tomatoes

as inputs.

12

The DOC Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) has added entities that use forced

labor in Xinjiang to the BIS Entity List, which imposes a license requirement on exports,

reexports, or transfers (in-country) of commodities, software, and technology subject to the

Export Administration Regulations (EAR)

13

to such entities. DOL has identified goods produced

in Xinjiang or through the labor transfer program on its List of Goods Produced by Child Labor

or Forced Labor, and Treasury has identified individuals and entities for the Specially

8

Risks and Considerations for Businesses and Individuals with Exposure to Entities Engaged in Forced Labor and

other Human Rights Abuses linked to Xinjiang, China, U.S. Department of State, 1-2 (July 13, 2021),

https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Xinjiang-Business-Advisory-13July2021-1.pdf [hereinafter

Xinjiang Business Advisory].

9

See id. at 2.

10

Pursuant to 19 C.F.R. § 12.42, CBP issues WROs against a good or goods from an entity when information

reasonably, but not conclusively, indicates that a good produced by forced labor, as defined under 19 U.S.C. § 1307,

is being, or is likely to be, imported into the United States. A WRO allows CBP to detain the goods in question at all

U.S. ports of entry unless importers can prove the absence of forced labor in their good’s supply chain.

11

The nine WROs issued against companies using government-labor schemes include: (1) silica-based products

from Hoshine Silicon Industry Co. Ltd. and subsidiaries; (2) all products from Lop County No. 4 Vocational Skills

Education and Training Center; (3) hair products made in the Lop County Hair Product Industrial Park; (4) apparel

produced by Yili Zhuowan Garment Manufacturing Co., Ltd. and Baoding LYSZD Trade and Business Co., Ltd; (5)

cotton produced and processed by Xinjiang Junggar Cotton and Linen Co., Ltd; (6) computer parts made by Hefei

Bitland Information Technology Co., Ltd.; (7) hair products from Lop County Meixin Hair Product Co. Ltd; (8) hair

products from Hetian Haolin Hair Accessories Co. Ltd.; and (9) garments produced by Hetian Taida Apparel Co.,

Ltd.

12

Withhold Release Orders and Findings List, U.S. Customs and Border Protection,

https://www.cbp.gov/trade/forced-labor/withhold-release-orders-and-findings (last visited May 19, 2022).

13

The Export Administration Regulations (15 C.F.R. §§ 730-774) impose additional license requirements on, and

limit the availability of most license exceptions for, exports, reexports, and transfers (in country) to certain listed

entities. The BIS Entity List (supplement no. 4 to part 744 of the EAR) identifies entities reasonably believed to be

involved in, or to pose a significant risk of being or becoming involved in, activities contrary to the national security

or foreign policy interests of the United States. The End-User Review Committee, composed of representatives of

the Departments of Commerce (Chair), State, Defense, Energy and, where appropriate, the Treasury, makes all

decisions regarding additions to, removals from, or other modifications to the BIS Entity List.

8

Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons List, including the XPCC.

14

DOS led an interagency

effort to issue an updated Xinjiang Supply Chain Business Advisory in July 2021, which provided

information highlighting the heightened risks for businesses with supply chain and investment links

to Xinjiang.

15

Additionally, DOS submitted the Diplomatic Strategy to Address Forced Labor in

Xinjiang to Congress on April 12, 2022. Current members of the FLETF contributed to these

efforts through interagency coordination and communication with U.S. stakeholders, including

the private sector and NGOs. Although past efforts have prevented specific goods made with

forced labor from entering the U.S. economy, the UFLPA bolsters the U.S. government’s

enforcement authority for prohibiting the importation of forced labor-made goods from Xinjiang

and across the PRC. The UFLPA will supersede current WROs related to Xinjiang for goods

imported on or after June 21, 2022.

16

Implementation of the UFLPA

Rebuttable Presumption

The UFLPA establishes a rebuttable presumption effective June 21, 2022 that any goods mined,

produced, or manufactured wholly or in part in Xinjiang are in violation of 19 U.S.C. § 1307.

Pursuant to the UFLPA, the same presumption applies to goods produced by any entity included

in this strategy’s UFLPA Entity List. The Commissioner of CBP may grant an exception to the

presumption if an importer meets specific criteria outlined in Section 3(b) of the UFLPA.

17

Public Comments

The UFLPA also mandated that the FLETF solicit input from the public regarding the use

of forced labor in the PRC and how best to ensure that goods mined, produced, or manufactured

wholly or in part with forced labor in the PRC are not imported into the United States.

On January 24, 2022, DHS, on behalf of the FLETF, published a Federal Register notice (FRN)

soliciting comments from the public.

18

DHS received 180 comments from U.S. and foreign

businesses, industry associations, civil society organizations, labor unions, academia, NGOs, and

14

2020 List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor, U.S. Department of Labor, (Sept. 2020),

https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/ILAB/child_labor_reports/tda2019/2020_TVPRA_List_Online_Final.pdf;

Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons List (SDN) Human Readable Lists, U.S. Department of the

Treasury, https://home.treasury.gov/policy-issues/financial-sanctions/specially-designated-nationals-and-blocked-

persons-list-sdn-human-readable-lists (last updated May 9, 2022).

15

Xinjiang Supply Chain Business Advisory, supra note 8.

16

Shipments that were imported prior to June 21, 2022 will be adjudicated through the CBP WRO/Findings process.

Shipments imported on or after June 21, 2022 that are subject to the UFLPA, which previously would have been

subject to a Xinjiang WRO, will be processed under UFLPA procedures, and detained, excluded, or seized.

17

See Pub. L. No. 117-78, § 3, 135 Stat. 1525 (2021).

18

Notice Seeking Public Comments on Methods To Prevent the Importation of Goods Mined, Produced, or

Manufactured With Forced Labor in the People's Republic of China, Especially in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous

Region, Into the United States, 87 Fed. Reg. 3567 (Jan. 24, 2022).

9

private individuals.

19

The comments addressed a wide array of issues such as transshipment of

materials produced by forced labor, labor conditions in Xinjiang and the PRC, innovative

supply-chain tracing technologies, reports of labor transfers and other programs connected to

forced labor in the region, and PRC-government retaliation against businesses. Commenters

made recommendations for implementing the UFLPA, raised concerns regarding the necessary

information to rebut the presumption, and provided suggestions on how importers can meet the

“clear and convincing” evidentiary standard, which governs exceptions to the presumption.

The FLETF held a hearing on April 8, 2022, on the use of forced labor in the PRC and measures

to prevent the importation into the United States of goods produced, mined, or manufactured,

wholly or in part, with forced labor.

20

The hearing was organized to encompass the following

topics: (i) forced-labor schemes in Xinjiang and the PRC; (ii) risks of importing goods made

wholly or in part with forced labor; (iii) measures that can be taken to trace the origin of goods

and to offer greater supply chain transparency; (iv) measures that can be taken to identify third

country supply chain routes; (v) factors to consider in developing and maintaining the required

UFLPA Entity List; (vi) high-priority enforcement sectors, including cotton, tomato, and

polysilicon; (vii) importer guidance; (viii) opportunities for coordination and collaboration; and

(ix) other general comments related to the UFLPA and covering multiple topics.

Sixty members of the public provided verbal testimony, and nine submitted supplemental written

testimony. Witnesses included private individuals, industry associations, consultancy and risk-

management companies, civil society organizations, NGOs, research and educational

institutions, advocacy groups, labor unions, and importers or their representatives. Testimony

addressed topics such as forced labor conditions in Xinjiang; concerns related to UFLPA

implementation; and technologies, roadblocks, and potential solutions related to UFLPA

implementation.

21

The FLETF has considered all public comments received in response to the January 24, 2022

FRN and April 8, 2022 public hearing in the development of this strategy.

19

Id.

20

Notice of Public Hearing on the Use of Forced Labor in the People's Republic of China and Measures To Prevent

the Importation of Goods Produced, Mined, or Manufactured, Wholly or in Part, With Forced Labor in the People's

Republic of China Into the United States, 87 Fed. Reg. 15448 (Mar. 18, 2022).

21

Notice of Public Hearing on the Use of Forced Labor in the People’s Republic of China and Measures to Prevent

the Importation of Goods Produced, Mined, or Manufactured, Wholly or in Part, With Forced Labor in the People’s

Republic of China Into the United States, Regulations.gov, https://www.regulations.gov/docket/DHS-2022-0001

(last visited May 19, 2022) (containing public comments submitted in response to 87 Fed. Reg. 3567 and a transcript

of verbal testimony from the hearing on April 8, 2022).

10

I. Assessment of the Risk of Importing Goods Mined,

Produced, or Manufactured with Forced Labor in the

People’s Republic of China

This section provides a comprehensive assessment of the risk of importing goods mined,

produced, or manufactured wholly or in part with forced labor in the PRC due to threats,

including the use of forced labor in supply chains.

22

This assessment of risk supports the overall

strategy to enforce the prohibition on the importation of goods made with forced labor in

Xinjiang and will address the following:

• Threats that may lead to the importation into the United States of goods mined, produced, or

manufactured wholly or in part with forced labor in the PRC; and

• Procedures that can be implemented or improved to reduce such threats.

23

Overview of Forced Labor in Xinjiang

The PRC government has committed genocide and crimes against humanity against Uyghurs and

members of other ethnic and religious minority groups in Xinjiang. Other human rights abuses in

Xinjiang involve discriminatory surveillance, ethno-racial profiling measures designed to

subjugate and exploit minority populations in internment camps and, since at least 2017, the use

of widespread state-sponsored forced labor.

24

DOS’s 2021 Trafficking in Persons Report stated

that the PRC arbitrarily detained more than one million Uyghurs and members of other mostly

Muslim minority groups in Xinjiang.

25

Many detained individuals approved to “graduate” from

internment were sent to external manufacturing sites in proximity to the camps or in other

provinces and subjected to forced labor.

26

The government continued to transfer some non-

interned members of minority communities designated arbitrarily as “rural surplus labor” to

other areas within Xinjiang as part of a “poverty alleviation” program to exploit them for forced

labor.

27

Authorities also used the threat of internment to coerce members of Muslim communities

into forced labor in manufacturing.

28

22

As used in this assessment, a “supply chain” is the sequence of steps taken to produce a final good from primary

factors, starting with processing of raw materials, continuing with production of (often a series of) intermediate

inputs, and ending with final assembly and distribution.

23

Pub. L. No. 117-78, § 2(d)(1), 135 Stat. 1525 (2021).

24

Xinjiang Business Advisory, supra note 8, at 1-2; 2021 Trafficking in Persons Report, U.S. Department of State

(June 2020), https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/TIPR-GPA-upload-07222021.pdf.

25

2021 Trafficking in Persons Report, supra note 24, at 46.

26

Id. at 177.

27

Id.

28

Id.

11

PRC-government documents shared by the New York Times in November 2019 confirm that

forced labor is part of the government’s targeted campaign of repression, mass internment, and

indoctrination of ethnic minorities in Xinjiang.

29

Personal testimonies of former internment camp

detainees indicate PRC

authorities are systemically

forcing predominantly

Muslim ethnic minorities to

engage in forced labor in

Xinjiang.

30

Additionally, the

PRC has expanded its mass

detention and political

indoctrination campaign

through the transfer of more

than 80,000 detainees into

forced labor in as many as 19

other provinces between

April 1, 2019 and March 31,

2020, according to a DOS

report.

31

Satellite imagery

also shows rapid

construction of camps in

Xinjiang between 2015 and

2020.

32

PRC authorities also placed

more than 500,000 rural

Tibetans in “military-style”

vocational training and

manufacturing jobs around the country under the auspices of a quota-based “surplus labor”

29

Austin Ramzy & Chris Buckley, ‘Absolutely No Mercy’: Leaked Files Expose How China Organized Mass

Detentions of Muslims, N.Y. Times (Nov. 16, 2019),

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/11/16/world/asia/china-xinjiang-documents.html.

30

Global Supply Chains, Forced Labor, and the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, Congressional-Executive

Commission on China, 5 (Mar. 2020),

https://www.cecc.gov/sites/chinacommission.house.gov/files/documents/CECC%20Staff%20Report%20March%20

2020%20-

%20Global%20Supply%20Chains%2C%20Forced%20Labor%2C%20and%20the%20Xinjiang%20Uyghur%20Aut

onomous%20Region.pdf; Vicky Xiuzhong Xu et al., Uyghurs for Sale: ‘Re-education,’ forced labour and

surveillance beyond Xinjiang, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 5 (Mar. 1, 2020), https://ad-aspi.s3.ap-southeast-

2.amazonaws.com/2021-

10/Uyghurs%20for%20sale%2020OCT21.pdf?VersionId=zlRFV8AtLg1ITtRpzBm7ZcfnHKm6Z0Ys.

31

2021 Trafficking in Persons Report, supra note 24, at 177.

32

Who are the Uyghurs and why is China being accused of genocide?, BBC News (June 21, 2021),

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-22278037; Eric Robinson & Sean Mann, Part 2: Have Any of

Xinjiang’s Detention Facilities Closed?, Tearline.mil (Feb. 26,2021),

https://www.tearline.mil/public_page/xinjiang-nighttime-2/.

12

transfer program ostensibly intended as a “poverty alleviation” measure.

33

Observers noted that

victims were subjected to forced labor and had little to no ability to refuse participation due to

the PRC’s social control over Tibet.

34

Threats that May Lead to the Importation of Goods Made with Forced Labor from the

PRC

Supply chains that touch Xinjiang are highly susceptible to the use of forced labor. Complex

supply chains obscure the use of PRC-based forced labor in goods that enter the United States.

Threats that amplify the likelihood of the presence of such goods in U.S. supply chains include

lack of supply chain visibility, obscured Xinjiang inputs into multi-tiered manufacturing, supply

chains that commingle inputs made with forced labor with legitimate production processes,

intentional import prohibition evasion through transshipment, and forced labor practices that

target vulnerable populations within the PRC.

Lack of Supply Chain Visibility

Global supply chain distribution and complexity in the production, processing, and

manufacturing of goods is a key challenge in preventing goods produced with state-sponsored

forced labor in the PRC from entering the United States.

35

This complexity obscures the origins

of goods sourced from Xinjiang—a challenge compounded by the limited means of reliably

tracing product sourcing.

Importers face challenges in tracing their supply chains due to a lack of tracing technologies,

restrictions on independent auditors in the region, and other challenges.

36

As a result, importers

often have visibility only into primary stages of their supply chains but not into the raw, or near-

raw, material supplier level.

37

Forced labor often occurs at this supplier level, for example in

agriculture and extraction of raw materials; and, in some cases, forced labor will be in mid-tier

production chains, for example in manufacturing and assembly.

38

U.S. businesses may struggle

33

Adrian Zenz, Xinjiang’s System of Militarized Vocational Training Comes to Tibet, The Jamestown Foundation:

China Brief (Sept. 22, 2020), https://jamestown.org/program/jamestown-early-warning-brief-xinjiangs-system-of-

militarized-vocational-training-comes-to-tibet/.

34

Id.

35

Not for Sale-Advertising Forced Labor Products for Illegal Export, Laogai Research Foundation, 6-7 (Feb. 2010),

https://d18mm95b2k9j1z.cloudfront.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/21-Not-for-sale.pdf; Global Supply Chains,

supra note 30, at 7.

36

See Eva Xiao, Auditors to Stop Inspecting Factories in China’s Xinjiang Despite Forced-Labor Concerns, Wall

St. J. (Sept. 21, 2020), https://www.wsj.com/articles/auditors-say-they-no-longer-will-inspect-labor-conditions-at-

xinjiang-factories-11600697706.

37

Consumer Technology Association Comment to the Forced Labor Enforcement Task Force, Regulations.gov, 2, 6

(Mar. 11, 2022), https://downloads.regulations.gov/DHS-2022-0001-0139/attachment_1.pdf.

38

Lehr, supra note 3, at 2-3; Ending child labour, forced labour and human trafficking in global supply chains,

International Labour Organization, 62 (Nov. 12, 2019), https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_norm/---

ipec/documents/publication/wcms_716930.pdf. Suppliers in a supply chain are often ranked by “tier,” depending on

their distance from the business producing the good at issue. First-tier suppliers are those who supply direct to the

business, second-tier are suppliers to the first-tier, and so on until the raw or near-raw supplier level.

13

to gain visibility into the suppliers involved in the early stages of manufacturing, and therefore

are not always aware of supplier level or mid-tier manufacturer sourcing, and will continue to be

unaware without wider availability of adequate tracing technologies.

39

If not aware of material

supplier level or mid-tier sourcing, final tier manufacturers and U.S. importers would not be able

to confirm if those materials were sourced directly or indirectly from Xinjiang.

Third Country or Province Manufacturing Processes

In 2019, total exports from Xinjiang totaled $17.6 billion, including only $300 million in direct

U.S. imports.

40

The China Chamber of International Commerce reports that in 2020, Xinjiang

had direct exports to 177 countries and regions, exporting 4,761 different kinds of products,

therefore introducing risk that imports from these 177 countries may be impacted by labor

conditions in Xinjiang.

41

For example, Xinjiang produces about one-fifth of the world’s cotton

42

and about half of the world’s polysilicon.

43

Raw or processed materials (e.g., cotton, thread or

yarn) manufactured in Xinjiang may be shipped to another region or province in the PRC or to a

third country for processing. Those materials could be commingled with inputs from other

regions and obscure the origin of the materials imported into the United States.

44

Companies that

purchase raw or processed materials from third countries may in fact be procuring goods from

Xinjiang indirectly.

Intentional Transshipment and Evasion

In efforts to circumvent 19 U.S.C. § 1307, companies attempt to use illegal transshipment to

conceal the origin of goods or inputs from Xinjiang. For example, even though CBP issued a

WRO on the XPCC in 2020 for using forced labor, the XPCC has sustained trade relationships

39

National Association of Manufacturers Comment to the Forced Labor Enforcement Task Force, Regulations.gov,

2 (Mar. 11, 2022), https://downloads.regulations.gov/DHS-2022-0001-0176/attachment_1.pdf.

40

Working on the chain gang: Congress is moving to block goods made with the forced labor of Uyghurs, The

Economist (Jan. 9 2021), https://www.economist.com/united-states/2021/01/09/congress-is-moving-to-block-goods-

made-with-the-forced-labour-of-uyghurs.

41

China Chamber of International Commerce Comment to the Forced Labor Enforcement Task Force,

Regulations.gov, 21-22 (Mar. 11, 2022), https://www.regulations.gov/comment/DHS-2022-0001-0157.

42

BBC News, supra note 32; Laura T. Murphy Comment to the Forced Labor Enforcement Task Force,

Regulations.gov, 3 (Mar. 11, 2022), https://downloads.regulations.gov/DHS-2022-0001-0148/attachment_1.pdf.

43

Solar Energy Industries Association Response to Senator Rubio and Senator Merkley, SEIA, 1 (Mar. 26, 2021),

https://www.seia.org/sites/default/files/2021-

03/SEIA%20Response%20to%20Senators%20Rubio%20and%20Merkley%20%283.26.2021%29.pdf; Dan

Murtaugh et al., Secrecy and Abuse Claims Haunt China’s Solar Factories in Xinjiang, Bloomberg (Apr. 13, 2021),

https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2021-xinjiang-solar/?sref=Tj5BOuJ2.

44

International Union, United Automobile, Aerospace & Agricultural Implement Workers of America Comment to

the Forced Labor Enforcement Task Force, Regulations,gov, 2 (Mar. 8, 2022),

https://downloads.regulations.gov/DHS-2022-0001-0047/attachment_1.pdf.

14

with commercial actors in third countries.

45

These relationships allow the XPCC to evade U.S.

import restrictions by transshipping goods through these third countries. One study that traced

goods produced by XPCC-majority owned companies found that, since 2019, these companies

have exported 4,559 shipments to their top trade partners, who then reexported these goods to the

United States and other countries.

46

For example, XPCC subsidiaries have exported tomato

products to a third country food company, which, since 2019, has likely used these inputs in over

300 shipments exported to the United States.

47

Goods originating from Xinjiang, but that arrive

in the United States under a declared country of origin other than the PRC, may evade detection

as forced labor-made products.

Manufacturing processes and multi-tiered supply chains can further obscure the use of forced

labor inputs by incorporating them into legitimate manufacturing processes. A 2021 USAID-

funded Sheffield Hallam University study detailed the practice of PRC textile companies that,

although not using forced labor in their own mid-tier third country facilities, rely on prohibited

Xinjiang raw materials or semi-finished goods. Such goods could then be exported from a third

country to the United States as a means of obscuring or “laundering” the importation of tainted

raw materials from Xinjiang.

48

PRC Policies and Practices Pose Challenges to U.S. Forced Labor Enforcement

Suppliers and manufacturers located in the PRC face pressures, including via the PRC’s Anti-

Foreign Sanctions Law, to defy U.S. import laws and regulations.

49

In March 2022, U.S. industry

stakeholders reported that the PRC government has acted against PRC companies for complying

with U.S. requirements to eliminate Xinjiang supply chain inputs.

50

The PRC also encourages the

use of forced labor through its “mutual pairing assistance” programs, which provide companies

with government incentives to establish factories near Xinjiang internment camps and to train

detainees in labor-intensive industries like textile and garment manufacturing.

51

45

Irina Bukharin, Long Shadows: How the Global Economy Supports Oppression in Xinjiang, C4ADS, 16-17

(2021), https://c4ads.org/s/Xinjiang-Report.pdf; Treasury Sanctions Chinese Entity and Officials Pursuant to Global

Magnitsky Human Rights Executive Order, U.S. Department of the Treasury (July 31, 2020),

https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm1073; CBP Issues Detention Order on Cotton Products Made by

Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps Using Prison Labor, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (Dec. 2,

2020), https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/national-media-release/cbp-issues-detention-order-cotton-products-made-

xinjiang-production.

46

Bukharin, supra note 45, at 18.

47

Id. at 20.

48

Laura T. Murphy et al., Laundering Cotton: How Xinjiang Cotton is Obscured in International Supply Chains,

Sheffield Hallam University Helena Kennedy Centre for International Justice, 51 (2021),

https://www.shu.ac.uk/helena-kennedy-centre-international-justice/research-and-projects/all-projects/laundered-

cotton.

49

Seyfarth Shaw LLP, Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law: Update for Companies Doing Business in China, JDSupra (Oct.

15, 2021), https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/anti-foreign-sanctions-law-update-for-3549235/.

50

United States Council for International Business Comment to the Forced Labor Enforcement Task Force,

Regulations.gov, 29 (Mar. 10, 2022), https://downloads.regulations.gov/DHS-2022-0001-0137/attachment_1.pdf.

51

See infra Section II. Evaluation and Description of Forced Labor Schemes and UFLPA Entity List.; Xinjiang

Business Advisory, supra note 8, at 7.

15

U.S. and other Western companies have also been targeted by the PRC government, potentially

due to public statements against forced labor in Xinjiang.

52

In March 2021, a clothing retailer

was removed from all major e-commerce platforms in the PRC after the Communist Youth

League of China accused the retailer of “spreading rumors” about the cotton industry in

Xinjiang.

53

In June 2021, the PRC’s General Administration of Customs confiscated, destroyed,

or returned several shipments from U.S. companies that had spoken out against forced labor.

54

Procedures to Reduce Such Threats

Existing Efforts to Address the Threat of Forced Labor Goods Entering U.S. Supply Chains

State-sponsored forced labor in the PRC continues to pose a significant threat to U.S. and global

supply chains. As of April 2022, CBP has 35 active WROs

55

against goods from the PRC,

accounting for nearly 65 percent of all WROs. Many recent WROs issued against entities based

in the PRC have been tied to the government’s use of forced labor targeting Uyghurs and

members of other ethnic and religious minorities in Xinjiang. In addition, CBP maintains five

active Findings

56

against goods produced with forced labor in the PRC, accounting for 55

percent of CBP’s total forced labor Findings worldwide.

57

52

China accuses Western firms over ‘harmful’ kids’ goods, BBC News (June 3, 2021),

https://www.bbc.com/news/business-57339758.

53

Allard K. Lowenstein International Human Rights Clinic Comment to the Forced Labor Enforcement Task Force,

Regulations.gov, 5-6 (Mar. 11, 2022), https://downloads.regulations.gov/DHS-2022-0001-0141/attachment_1.pdf.

54

Karen M. Sutter, China’s Recent Trade Measures and Countermeasures: Issues for Congress, Congressional

Research Service, 55 (Dec. 10, 2021), https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R46915.

55

CBP implements 19 U.S.C. 1307 through the issuance of WROs and Findings to prevent merchandise produced in

whole or in part in a foreign country using forced labor from being imported into the United States. There are 35

active WROs and one partially active WRO as of April 2022. CBP is now partially implementing one WRO

involving goods from the PRC as a result of a modification that removed some goods covered by the original WRO.

56

CBP issues a Finding when the agency makes a determination based on probable cause that forced labor is used in

the manufacturing or production of a good or goods. See 19 CFR 12.42(f). A Finding allows CBP to seize the

product(s) in question at all U.S. ports of entry.

57

Withhold Release Orders and Findings List, supra note 12.

16

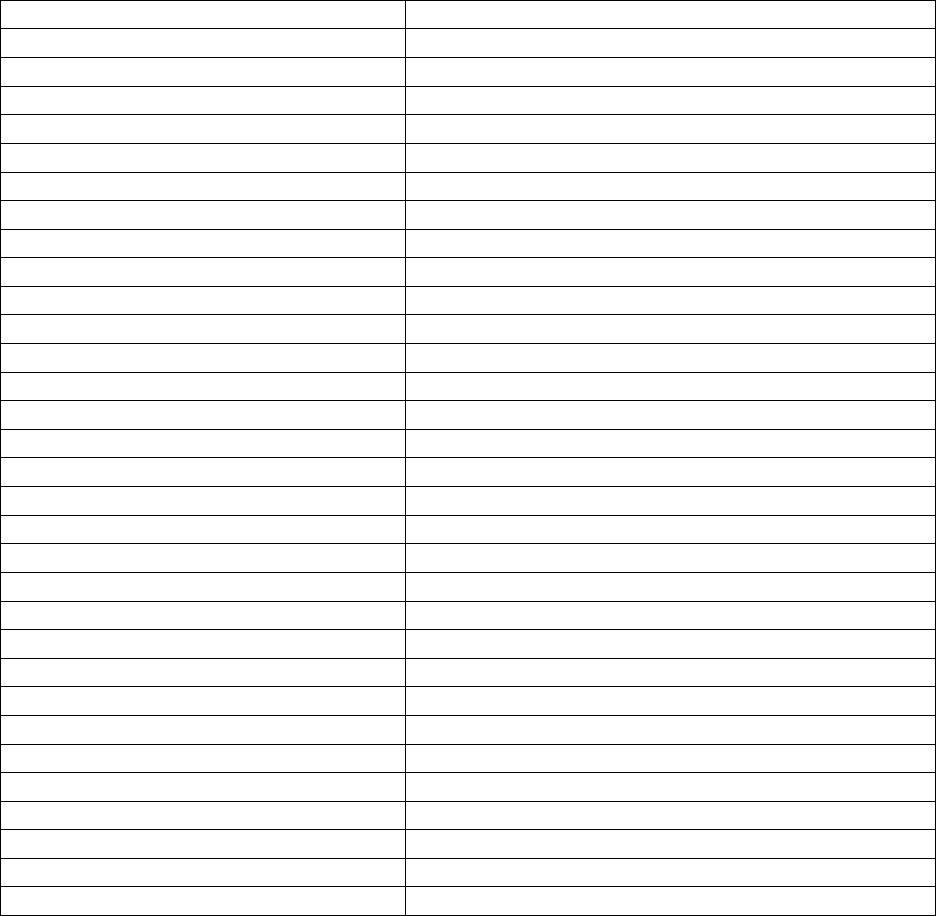

Image as of April 27, 2022 from https://www.cbp.gov/trade/forced-labor/withhold-release-orders-and-findings

DOL’s List of Goods Produced by Child or Forced Labor includes 18 goods made with forced

labor in China: artificial flowers, Christmas decorations, coal, fish, footwear, garments, gloves,

hair products, nails, thread or yarn, tomato products, bricks, cotton, electronics, fireworks,

textiles, toys,

58

and polysilicon (added in 2021).

59

Of these, ten have links to forced labor in

Xinjiang or by Uyghur workers transferred to other parts of China: cotton, garments, footwear,

electronics, gloves, hair products, polysilicon, textiles, thread/yarn, and tomato products. In

addition, citing widespread state-sponsored forced labor, DOS has for years identified the PRC

as a Tier 3 country, the lowest rank, in its Trafficking in Persons Report due to the PRC’s failure

to meet minimum standards on eliminating human trafficking set forth in the Trafficking

Victims’ Protection Act.

60

Future Efforts to Reduce Such Threats

Businesses and individuals should undertake heightened due diligence to ensure compliance with

U.S. law and to identify potential supply chain exposure to companies operating in Xinjiang,

58

2020 List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor, supra note 14, at 31.

59

Notice of Update to the Department Labor’s List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor, 86 FR

32977 (Jun. 23, 2021).

60

2021 Trafficking in Persons Report, supra note 24, at 47.

17

linked to Xinjiang (e.g., through the pairing assistance program or Xinjiang supply chain inputs),

or using Uyghur or other minority laborers in the PRC.

Businesses and individuals must review the risks and both civil and criminal liabilities in doing

business with suppliers in the PRC and in third countries that may touch PRC forced labor. The

United Nations’ Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, the Organisation for

Economic Cooperation and Development’s Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, the

International Labor Organization’s (ILO) Combating Forced Labour: A Handbook for

Employers and Business, and the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights guide on

The Corporate Responsibility to Respect Human Rights provide guidance for heightened due

diligence in high-risk and conflict-affected regions. These documents highlight factors that may

be considered in determining appropriate action, including whether and how to responsibly end

relationships when a business is unable to prevent or mitigate the use of forced labor. Additional

recommendations to secure supply chains against the risk of forced labor can be found in Section

VI of this strategy.

18

II. Evaluation and Description of Forced-Labor

Schemes and UFLPA Entity List

This section provides a description and evaluation of PRC government-labor schemes, as

mandated by Section 2(d)(2)(A) of the UFLPA.

‘‘Pairing Assistance,’’ ‘‘Poverty Alleviation,’’ and Other Government-Labor Schemes

Overview

The PRC government engages in genocide and crimes against humanity against Uyghurs and

other ethnic and religious minority groups in Xinjiang.

61

Forced labor is a central tactic used for

repression in state-run internment camps.

62

The PRC has implemented labor programs across the

country with a stated objective of eradicating poverty. However, use of such programs in

Xinjiang and the use of labor sourced from persecuted groups carries a particularly high-risk of

forced labor for members of ethnic and religious minority groups. In some cases, workers are

transferred directly from detention to factories in and outside of Xinjiang.

63

Even when workers

in these programs are not directly transferred from internment, they are not voluntarily offering

themselves as labor.

64

The PRC government administers labor programs that target Uyghurs, Kazakhs, Kyrgyz,

Tibetans, and members of other persecuted groups. Purported “poverty alleviation,” “pairing

assistance,” and “labor transfer” programs can include discriminatory social control, pervasive

surveillance, and large-scale internment.

65

An official PRC government report published in

September 2020 indicated that the government reports to have placed over two and a half million

workers at farms and factories in Xinjiang and across the PRC.

66

Research has since shown that

workers in these schemes are largely members of ethnic minorities who are subjected to systemic

oppression through forced labor and do not offer themselves voluntarily.

67

Notably, reports and

testimony from former workers from Xinjiang who are members of ethnic and religious minority

groups have consistently identified indicators of forced labor in four specific sectors: apparel,

cotton and cotton products, silica-based products (including polysilicon), and tomatoes and

downstream products.

68

61

Xinjiang Business Advisory, supra note 8 at 1-2.

62

Forced Labor in China’s Xinjiang Region, U.S. Department of State (July 1, 2021), https://www.state.gov/wp-

content/uploads/2021/06/Forced-Labor-in-Chinas-Xinjiang-Region_LOW.pdf.

63

Lehr, supra note 3 at 1-2.

64

See, e.g., id.

65

Murphy et al., supra note 48, at 26-29.

66

Employment and Labor Rights in Xinjiang [English version], The State Council Information Office of the

People’s Republic of China (Sept. 2020).

67

Murphy et al., supra note 48, at 9.

68

The FLETF has identified these four sectors as high priority for enforcement in Strategy Section II.

19

State-Sponsored Forced Labor in the PRC’s Labor Programs

The PRC refers to internment camps as “Vocational Training Centers.”

69

Uyghurs and members

of other ethnic and religious minority groups are subjected to forced labor in the internment

camps, but so too are individuals who “graduate” from the camps.

70

Such individuals are often

required to work at nearby facilities or are sent to satellite factories in their home region or other

provinces.

71

The PRC “Mutual Pairing Assistance” Program

Xinjiang government documents indicate that the PRC administers the “mutual pairing

assistance” program, which facilitates PRC companies establishing satellite factories in Xinjiang

and in conjunction with the internment camps.

72

Through the PRC government’s mutual pairing

assistance program, at least 19 cities and developed provinces have spent billions of Chinese

yuan to establish factories in Xinjiang.

73

Factories are directly involved in the use of internment

camp labor, including as part of labor programs that require parents to leave behind children as

young as 18 months old while forced to work full-time under constant surveillance. Those

children are then sent to state-controlled orphanages and other facilities.

74

The PRC’s pairing strategy relies generally on low-skilled labor industries that require only

limited job training.

75

Private companies receive subsidies and other incentives for operating in

Xinjiang or “absorbing” ethnic minority workers through government-labor assignment

programs.

76

Xinjiang attracts textile and garment companies by building production sites near

internment camps and providing companies subsidies for each detainee they train and employ.

77

These subsidies create a windfall for these PRC-linked companies, artificially lowering labor

costs and supporting unfair competition. Reports and testimony from minority-group former

workers have indicated the use of forced labor at private-sector labor assignments in the cotton

textile sector, including through restriction of movement, deception about the terms of work,

retention of identification documents, withholding of wages, and physical abuse.

78

69

2021 Trafficking in Persons Report, supra note 24, at 178.

70

Id.

71

Adrian Zenz, Beyond the Camps: Beijing’s Grand Scheme of Coercive Labor, Poverty Alleviation and Social

Control in Xinjiang, Congressional Executive Commission on China, 6-14 (Oct. 17, 2019),

https://www.cecc.gov/sites/chinacommission.house.gov/files/documents/Beyond%20the%20Camps%20CECC%20t

estimony%20version%20%28Zenz%20Oct%202019%29.pdf.

72

Id. at 8-13.

73

Id. at 23-24.

74

Id. at 21-23.

75

Xinjiang Business Advisory, supra note 8, at 7.

76

Murphy et al., supra note 48, at 10.

77

Id. at 17.

78

Id.; see also Xinjiang Victims Database, https://www.shahit.biz/eng (last visited May 19, 2022).

20

PRC’s Poverty Alleviation Programs

The PRC’s “poverty alleviation” programs place Uyghurs and members of other persecuted

minority groups in farms and factories across the PRC and compel them to work involuntarily

under threat of penalty. PRC government policy documents indicate that these programs are

intended to exercise control over the employment of every working-age person in Xinjiang.

79

Factories that accept minority workers through these labor programs receive government

subsidies, as do the recruitment intermediaries who organize transfers of workers from Xinjiang

to other provinces.

80

According to an NGO report, between 2017 and 2019 an estimated 80,000

ethnic minority workers were assigned out of Xinjiang to work in factories in eastern Chinese

provinces through labor transfer programs under a PRC government policy known as “Xinjiang

Aid.”

81

The factories produce inputs for a variety of industries, including apparel and textiles,

electronics, solar energy, and the automotive sector.

82

Land Transfer and Reemployment

In rural areas, coercive expropriation of farmland from small-scale farmers also facilitates

involuntary labor transfers.

83

The Xinjiang government administers crop production programs

under which predominantly minority owners of (usually small) agricultural plots are required to

transfer their land to “cooperatives” run by a small group of prominent farmers or a Han Chinese

person.

84

The cooperatives in turn grow crops for use in private companies’ manufacturing, at

purchase prices set by the company. Dispossessed farmers are left unemployed and vulnerable to

forced labor transfers or, if they refuse, internment. In some cases, farmers are required to work

as hired labor for the cooperatives and companies that assume control over expropriated land,

including their own, in a program described as “land transfer and reemployment.”

85

Indicators of Forced Labor in PRC Labor Programs

The ILO Forced Labour Convention defines forced labor as “all work or service…exacted from

any person under the menace of any penalty and for which the said person has not

offered…[them]self voluntarily.”

86

This is the same definition set forth in 19 U.S.C. § 1307. The

ILO has identified 11 indicators of forced labor: abuse of vulnerability, deception, restriction of

movement, isolation, physical and sexual violence, intimidation and threats, retention of identity

79

Zenz, supra note 71, at 4.

80

Id. at 10-11.

81

Xu et al., supra note 30, at 3, 13.

82

Id. at 5.

83

Laura T. Murphy, Kendyl Salcito & Nyrola Elimä, Financing & Genocide: Development Finance and the Crisis

in the Uyghur Region, The Atlantic Council, 8 (Feb. 2022), https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/wp-

content/uploads/2022/02/Financing__Genocide.pdf.

84

Id.

85

Id. at 26; Murphy et al., supra note 48, at 11-12.

86

International Labour Organization, Forced Labour Convention, 1930, No. 29,

https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:C029.

21

documents, withholding of wages, debt bondage, abusive working and living conditions, and

excessive overtime.

87

The following forced labor indicators

88

are present in government-labor schemes that use the

forced labor of members of persecuted minorities from Xinjiang:

• Intimidation and threats: Labor transfer and work is undertaken involuntarily as a result of

pervasive government intimidation and threats, as well as penalty of detention and

indoctrination. Individuals who attempt to resist government work assignments are subjected