WORLD

DRUG

REPORT

2018

4

DRUGS AND AGE

Drugs and associated issues among

young people and older people

9 789211 483048

ISBN 978-92-1-148304-8

© United Nations, June 2018. All rights reserved worldwide.

ISBN: 978-92-1-148304-8

eISBN: 978-92-1-045058-4

United Nations publication, Sales No. E.18.XI.9

This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form

for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from

the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made.

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) would appreciate

receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source.

Suggested citation:

World Drug Report 2018 (United Nations publication, Sales No. E.18.XI.9).

No use of this publication may be made for resale or any other commercial

purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from UNODC.

Applications for such permission, with a statement of purpose and intent of the

reproduction, should be addressed to the Research and Trend Analysis Branch of UNODC.

DISCLAIMER

The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or

policies of UNODC or contributory organizations, nor does it imply any endorsement.

Comments on the report are welcome and can be sent to:

Division for Policy Analysis and Public Affairs

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

PO Box 500

1400 Vienna

Austria

Tel: (+43) 1 26060 0

Fax: (+43) 1 26060 5827

E-mail: [email protected]

Website: https://www.unodc.org/wdr2018

1

PREFACE

Drug treatment and health services continue to fall

short: the number of people suffering from drug use

disorders who are receiving treatment has remained

low, just one in six. Some 450,000 people died in

2015 as a result of drug use. Of those deaths,

167,750 were a direct result of drug use disorders,

in most cases involving opioids.

These threats to health and well-being, as well as to

security, safety and sustainable development,

demand an urgent response.

The outcome document of the special session of the

General Assembly on the world drug problem held

in 2016 contains more than 100 recommendations

on promoting evidence-based prevention, care and

other measures to address both supply and demand.

We need to do more to advance this consensus,

increasing support to countries that need it most

and improving international cooperation and law

enforcement capacities to dismantle organized crimi-

nal groups and stop drug trafficking.

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

(UNODC) continues to work closely with its

United Nations partners to assist countries in imple-

menting the recommendations contained in the

outcome document of the special session, in line

with the international drug control conventions,

human rights instruments and the 2030 Agenda for

Sustainable Development.

In close cooperation with the World Health Organi-

zation, we are supporting the implementation of

the International Standards on Drug Use Prevention

and the international standards for the treatment of

drug use disorders, as well as the guidelines on treat-

ment and care for people with drug use disorders in

contact with the criminal justice system.

The World Drug Report 2018 highlights the impor-

tance of gender- and age-sensitive drug policies,

exploring the particular needs and challenges of

women and young people. Moreover, it looks into

Both the range of drugs and drug markets are

expanding and diversifying as never before. The

findings of this year’s World Drug Report make clear

that the international community needs to step up

its responses to cope with these challenges.

We are facing a potential supply-driven expansion

of drug markets, with production of opium and

manufacture of cocaine at the highest levels ever

recorded. Markets for cocaine and methampheta-

mine are extending beyond their usual regions and,

while drug trafficking online using the darknet con-

tinues to represent only a fraction of drug trafficking

as a whole, it continues to grow rapidly, despite

successes in shutting down popular trading

platforms.

Non-medical use of prescription drugs has reached

epidemic proportions in parts of the world. The

opioid crisis in North America is rightly getting

attention, and the international community has

taken action. In March 2018, the Commission on

Narcotic Drugs scheduled six analogues of fentanyl,

including carfentanil, which are contributing to the

deadly toll. This builds on the decision by the

Commission at its sixtieth session, in 2017, to place

two precursor chemicals used in the manufacture

of fentanyl and an analogue under international

control.

However, as this World Drug Report shows, the prob-

lems go far beyond the headlines. We need to raise

the alarm about addiction to tramadol, rates of

which are soaring in parts of Africa. Non-medical

use of this opioid painkiller, which is not under

international control, is also expanding in Asia. The

impact on vulnerable populations is cause for seri-

ous concern, putting pressure on already strained

health-care systems.

At the same time, more new psychoactive substances

are being synthesized and more are available than

ever, with increasing reports of associated harm and

fatalities.

2

WORLD DRUG REPORT 2018

Next year, the Commission on Narcotic Drugs will

host a high-level ministerial segment on the 2019

target date of the 2009 Political Declaration and

Plan of Action on International Cooperation

towards an Integrated and Balanced Strategy to

Counter the World Drug Problem. Preparations are

under way. I urge the international community to

take this opportunity to reinforce cooperation and

agree upon effective solutions.

Yury Fedotov

Executive Director

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

increased drug use among older people, a develop-

ment requiring specific treatment and care.

UNODC is also working on the ground to promote

balanced, comprehensive approaches. The Office

has further enhanced its integrated support to

Afghanistan and neighbouring regions to tackle

record levels of opiate production and related secu-

rity risks. We are supporting the Government of

Colombia and the peace process with the Revolu-

tionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) through

alternative development to provide licit livelihoods

free from coca cultivation.

Furthermore, our Office continues to support efforts

to improve the availability of controlled substances

for medical and scientific purposes, while prevent-

ing misuse and diversion – a critical challenge if we

want to help countries in Africa and other regions

come to grips with the tramadol crisis.

3

CONTENTS

BOOKLET 1

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY — CONCLUSIONS AND POLICY IMPLICATIONS

BOOKLET 2

GLOBAL OVERVIEW OF DRUG DEMAND AND SUPPLY

Latest trends, cross-cutting issues

BOOKLET 3

ANALYSIS OF DRUG MARKETS

Opioids, cocaine, cannabis, synthetic drugs

BOOKLET 4

DRUGS AND AGE

Drugs and associated issues among young people and older people

BOOKLET 5

WOMEN AND DRUGS

Drug use, drug supply and their consequences

PREFACE ...................................................................................................... 1

EXPLANATORY NOTES ................................................................................ 5

KEY FINDINGS ............................................................................................. 6

INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................... 9

A. DRUG USE AMONG YOUNG PEOPLE AND OLDER PEOPLE ...................11

Trends in age demographics ...........................................................................................................11

Extent of drug use is higher among young people than among older people .................................11

B. DRUGS AND YOUNG PEOPLE ................................................................15

Patterns of drug use among young people .....................................................................................16

Pathways to substance use disorders ...............................................................................................22

Young people and the supply chain ...............................................................................................40

C. DRUGS AND OLDER PEOPLE .................................................................46

Changes in the extent of drug use among older people .................................................................47

What factors might lie behind the increase in the extent of drug use? ...........................................49

Drug treatment among older people who use drugs ......................................................................52

Drug-related deaths among older people who use drugs ................................................................54

GLOSSARY .................................................................................................. 57

REGIONAL GROUPINGS ..............................................................................59

4

WORLD DRUG REPORT 2018

Acknowledgements

The World Drug Report 2018 was prepared by the Research and Trend Analysis Branch, Division for

Policy Analysis and Public Affairs, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, under the supervision

of Jean-Luc Lemahieu, Director of the Division, and Angela Me, Chief of the Research and Trend

Analysis Branch.

General coordination and content overview

Chloé Carpentier

Angela Me

Analysis and drafting

Philip Davis

Diana Fishbein

Alejandra Sánchez Inzunza

Theodore Leggett

Kamran Niaz

Thomas Pietschmann

José Luis Pardo Veiras

Editing

Joseph Boyle

Jonathan Gibbons

Graphic design and production

Anja Korenblik

Suzanne Kunnen

Kristina Kuttnig

Coordination

Francesca Massanello

Administrative support

Anja Held

Iulia Lazar

Jonathan Caulkins

Paul Griffiths

Marya Hynes

Vicknasingam B. Kasinather

Letizia Paoli

Charles Parry

Peter Reuter

Francisco Thoumi

Alison Ritter

In memoriam

Brice de Ruyver

Review and comments

The World Drug Report 2018 benefited from the expertise of and invaluable contributions from

UNODC colleagues in all divisions.

The Research and Trend Analysis Branch acknowledges the invaluable contributions and advice

provided by the World Drug Report Scientific Advisory Committee:

The research for booklet 4 was made possible by the generous contribution of Germany

(German Agency for International Cooperation (GIZ)).

5

EXPLANATORY NOTES

The boundaries and names shown and the designa-

tions used on maps do not imply official endorsement

or acceptance by the United Nations. A dotted line

represents approximately the line of control in

Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Paki-

stan. The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has

not yet been agreed upon by the parties. Disputed

boundaries (China/India) are represented by cross-

hatch owing to the difficulty of showing sufficient

detail.

The designations employed and the presentation of

the material in the World Drug Report do not imply

the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the

part of the Secretariat of the United Nations con-

cerning the legal status of any country, territory, city

or area, or of its authorities or concerning the delimi-

tation of its frontiers or boundaries.

Countries and areas are referred to by the names

that were in official use at the time the relevant data

were collected.

All references to Kosovo in the World Drug Report,

if any, should be understood to be in compliance

with Security Council resolution 1244 (1999).

Since there is some scientific and legal ambiguity

about the distinctions between “drug use”, “drug

misuse” and “drug abuse”, the neutral terms “drug

use” and “drug consumption” are used in the World

Drug Report. The term “misuse” is used only to

denote the non-medical use of prescription drugs.

All uses of the word “drug” in the World Drug Report

refer to substances controlled under the international

drug control conventions.

All analysis contained in the World Drug Report is

based on the official data submitted by Member

States to the United Nations Office on Drugs and

Crime through the annual report questionnaire

unless indicated otherwise.

The data on population used in the World Drug

Report are taken from: World Population Prospects:

The 2017 Revision (United Nations, Department of

Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division).

References to dollars ($) are to United States dollars,

unless otherwise stated.

References to tons are to metric tons, unless other-

wise stated.

The following abbreviations have been used in the

present booklet:

EMCDDA

European Monitoring Centre for

Drugs and Drug Addiction

LSD Lysergic acid diethylamide

GHB gamma-Hydroxybutyric acid

MDMA 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine

UNICEF United Nations Children’s Fund

WHO World Health Organization

UNODC United Nations Office on Drugs

and Crime

INCB International Narcotics Control Board

Europol European Union Agency for Law

Enforcement Cooperation

KEY FINDINGS

Drug use and associated health conse-

quences are highest among young people

Surveys on drug use among the general population

show that the extent of drug use among young

people remains higher than that among older

people, although there are some exceptions associ-

ated with the traditional use of drugs such as opium

or khat. Most research suggests that early (12–14

years old) to late (15–17 years old) adolescence is a

critical risk period for the initiation of substance

use and that substance use may peak among young

people aged 18–25 years.

Cannabis is a common drug of choice for

young people

There is evidence from Western countries that the

perceived easy availability of cannabis, coupled with

perceptions of a low risk of harm, makes the drug

among the most common substances whose use is

initiated in adolescence. Cannabis is often used in

conjunction with other substances and the use of

other drugs is typically preceded by cannabis use.

Two extreme typologies of drug use

among young people: club drugs in

nightlife settings; and inhalants among

street children

Drug use among young people differs from country

to country and depends on the social and economic

circumstances of those involved.

Two contrasting settings illustrate the wide range

of circumstances that drive drug use among young

people. On the one hand, drugs are used in recrea-

tional settings to add excitement and enhance the

experience; on the other hand, young people living

in extreme conditions use drugs to cope with their

difficult circumstances.

The typologies of drugs used in these two different

settings are quite different. Club drugs such as

“ecstasy”, methamphetamine, cocaine, ketamine,

LSD and GHB are used in high-income countries,

originally in isolated “rave” scenes but later in

settings ranging from college bars and house parties

to concerts. The use of such substances is reportedly

much higher among young people. Among young

people living on the street, the most commonly used

drugs are likely to be inhalants, which can include

paint thinner, petrol, paint, correction fluid and

glue.

Many street children are exposed to physical and

sexual abuse, and substance use is part of their

coping mechanism in the harsh environment they

are exposed to on the streets. The substances they

use are frequently selected for their low price, legal

and widespread availability and ability to rapidly

induce a sense of euphoria.

Young people’s path to harmful use of

substances is complex

The path from initiation to harmful use of sub-

stances among young people is influenced by factors

that are often out of their control. Factors at the

personal level (including behavioural and mental

health, neurological developments and gene varia-

tions resulting from social influences), the micro

level (parental and family functioning, schools and

peer influences) and the macro level (socioeconomic

and physical environment) can render adolescents

vulnerable to substance use. These factors vary

between individuals and not all young people are

equally vulnerable to substance use. No factor alone

is sufficient to lead to the use of substances and, in

many instances, these influences change over time.

Overall, it is the critical combination of the risk

factors that are present and the protective factors

that are absent at a particular stage in a young per-

son’s life that makes the difference in their

susceptibility to drug use. Early mental and behav-

ioural health problems, poverty, lack of

opportunities, isolation, lack of parental involve-

ment and social support, negative peer influences

and poorly equipped schools are more common

among those who develop problems with substance

use than among those who do not.

7

4

Harmful use of substances has multiple direct effects

on adolescents. The likelihood of unemployment,

physical health problems, dysfunctional social rela-

tionships, suicidal tendencies, mental illness and

even lower life expectancy is increased by substance

use in adolescence. In the most serious cases, harm-

ful use of drugs can lead to a cycle in which damaged

socioeconomic standing and ability to develop rela-

tionships feed substance use.

Many young people are involved in the

drug supply chain due to poverty and lack

of opportunities for social and economic

advancement

Young people are also known to be involved in the

cultivation, manufacturing and production of and

trafficking in drugs. In the absence of social and

economic opportunities, young people may deal

drugs to earn money or to supplement meagre wages.

Young people affected by poverty or in other vulner-

able groups, such as immigrants, may be recruited

by organized crime groups and coerced into working

in drug cultivation, production, trafficking and

local-level dealing. In some environments, young

people become involved in drug supply networks

because they are looking for excitement and a means

to identify with local groups or gangs. Organized

crime groups and gangs may prefer to recruit chil-

dren and young adults for drug trafficking for two

reasons: the first is the recklessness associated with

younger age groups, even when faced with the police

or rival gangs; the second is their obedience. Young

people involved in the illicit drug trade in interna-

tional markets are often part of large organized crime

groups and are used mainly as “mules”, to smuggle

illegal substances across borders.

Increases in rates of drug use among older

people are partly explained by ageing

cohorts of drug users

Drug use among the older generation (aged 40 years

and older) has been increasing at a faster rate than

among those who are younger, according to the lim-

ited data available, which are mainly from Western

countries.

People who went through adolescence at a time

when drugs were popular and widely available are

more likely to have tried drugs and, possibly, to have

continued using them, according to a study in the

United States. This pattern fits in particular the so-

called “baby boomer” generation in Western Europe

and North America. Born between 1946 and 1964,

baby boomers had higher rates of substance use

during their youth than previous cohorts; a signifi-

cant proportion continued to use drugs and, now

that they are over 50, this use is reflected in the data.

In Europe, another cohort effect can be gleaned from

data on those seeking treatment for opioid use.

Although the number of opioid users entering treat-

ment is declining, the proportion who were aged

over 40 increased from one in five in 2006 to one in

three in 2013. Overdose deaths reflect a similar trend:

they increased between 2006 and 2013 for those

aged 40 and older but declined for those aged under

40. The evidence points to a large cohort of ageing

opioid users who started injecting heroin during the

heroin “epidemics” of the 1980s and 1990s.

Older people who use drugs require

tailored services, but few treatment

programmes address their specific needs

Older drug users may often have multiple physical

and mental health problems, making effective drug

treatment more challenging, yet little attention has

been paid to drug use disorders among older people.

There were no explicit references to older drug users

in the drug strategies of countries in Europe in 2010

and specialized treatment and care programmes for

older drug users are rare in the region; most initia-

tives are directed towards younger people.

Older people who use drugs account

for an increasing share of deaths directly

caused by drug use

Globally, deaths directly caused by drug use increased

by 60 per cent from 2000 to 2015. People over the

age of 50 accounted for 39 per cent of the deaths

related to drug use disorders in 2015. However, the

proportion of older people reflected in the statistics

has been rising: in 2000, older people accounted for

just 27 per cent of deaths from drug use disorders.

About 75 per cent of deaths from drug use disorders

among those aged 50 and older are linked to the

use of opioids. The use of cocaine and the use of

amphetamines each account for about 6 per cent;

the use of other drugs makes up the remaining 13

per cent.

9

INTRODUCTION

Substance use

initiation

Positive physical, social

and mental health

Harmful use

of substances

P

r

o

t

e

c

t

i

v

e

f

a

c

t

o

r

s

R

i

s

k

f

a

c

t

o

r

s

• Trauma and childhood

adversity

- child abuse and neglect

• Mental health problems

• Poverty

• Peer substance use and

drug availability

• Negative school climate

• Sensation seeking

Protective factors and risk factors for substance use

• Caregiver involvement

and monitoring

• Health and neurological

development:

- coping skills

- emotional regulation

• Physical safety and

social inclusion

• Safe neighbourhoods

• Quality school environment

Substance

use disorders

This booklet constitutes the fourth part of the World

Drug Report 2018 and is the first of two thematic

booklets focusing on specific population groups. In

this booklet, the focus is on drug issues affecting

young and older people.

Section A provides an overview of how the extent

and patterns of drug use vary across different age

groups, using examples from selected countries. Sec-

tion B contains a discussion of three aspects of drug

use among young people. Based on a review of the

scientific literature, the section describes the wide

range of patterns of drug use among young people,

including the use of inhalants among street children

and drug use in nightlife settings. Next, there is a

discussion of the link between child and youth devel-

opment and the factors that determine pathways to

substance use and related problems, as well as the

social and health consequences of drug use among

young people. The final part of the section contains

a discussion of how the lives of young people are

affected by illicit crop cultivation, drug production

and trafficking in drugs.

Section C is focused on older people who use drugs.

It describes the increases in the extent of drug use

among older people that have been observed over

the past decade or so in some countries. The pos-

sible factors that might help explain those increases

are briefly explored. The particular issues faced by

older people with drug use disorders in relation to

drug treatment and care are also discussed. Finally,

information on deaths due to drug use disorders

illustrates the severe health impact of drug use on

older people.

11

4

DRUGS AND AGE A. Drug use among young people and older people

Extent of drug use is higher among

young people than among older

people

Surveys on drug use among the general population

consistently show that the extent of drug use among

older people remains lower than that among young

people. Data show that peak levels of drug use are

seen among those aged 18–25. This is broadly the

situation observed in countries in most regions and

for most drug types.

The extent of drug use among young people, in

particular past-year and past-month prevalence,

which are indicators of recent and regular use,

remains much higher than that among older people.

However, lifetime prevalence, which is an indicator

of the extent of exposure of the general population

to drugs, remains higher among older people than

among young people for the use of substances that

have been on the market for decades. Conversely,

the use of substances that have emerged more

recently or have infiltrated certain lifestyles are

reportedly much higher among young people. One

such example is “ecstasy”, which has low levels of

lifetime use and hardly any current use among older

people, but high levels of lifetime use among young

people.

2 United Nations, Department of Economic and Social

Affairs, Population Division, “World population prospects:

the 2017 revision, key findings and advance tables”, Work-

ing paper No. ESA/P/WP/248 (New York, 2017).

A. DRUG USE AMONG

YOUNG PEOPLE AND

OLDER PEOPLE

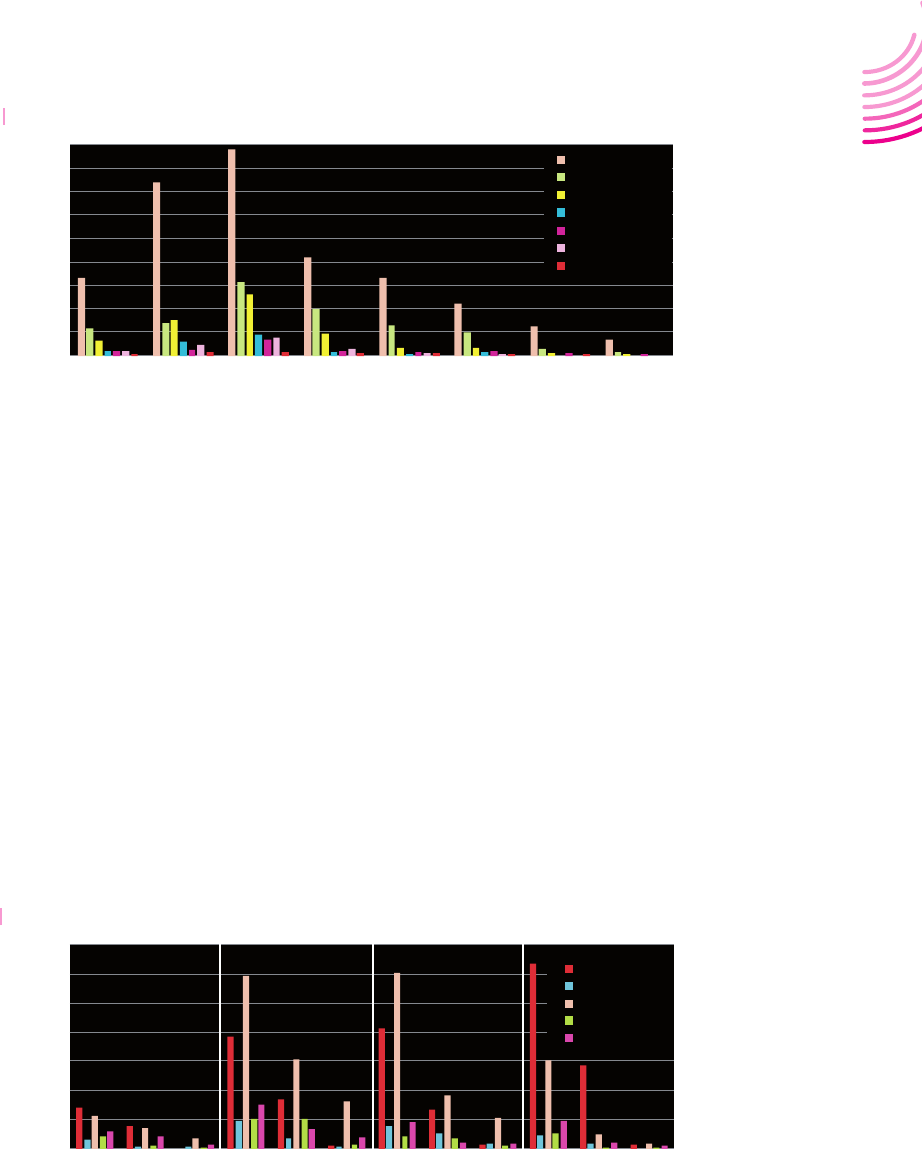

Trends in age demographics

The population in many parts of the world is rela-

tively young. In 2016, more than 4 in every 10

people worldwide were younger than 25 years old,

26 per cent were aged 0–14 years and 16 per cent

were aged 15–24 years. Europe was the region with

the lowest proportion of its population under 25

(27 per cent) and Africa was the region with the

highest proportion (60 per cent). However, in all

regions, the proportion of the population aged

15–24 is projected to decline by 2050.

1

On the other hand, in recent years, gains in life

expectancy have been achieved in all regions, with

life expectancy globally projected to increase by 10

per cent over the next generation or so, from 71

years (2010–2015) to 77 years (2045–2050).

2

As a

result, between 2016 and 2050, the number of

people aged 50 and older is expected to almost

double. By 2050, one third or more of the popula-

tions of all regions, except for Africa, will be aged

50 or older.

1 United Nations, Department of Economic and Social

Affairs, Population Division, World Population Prospects

database, 2017 revision.

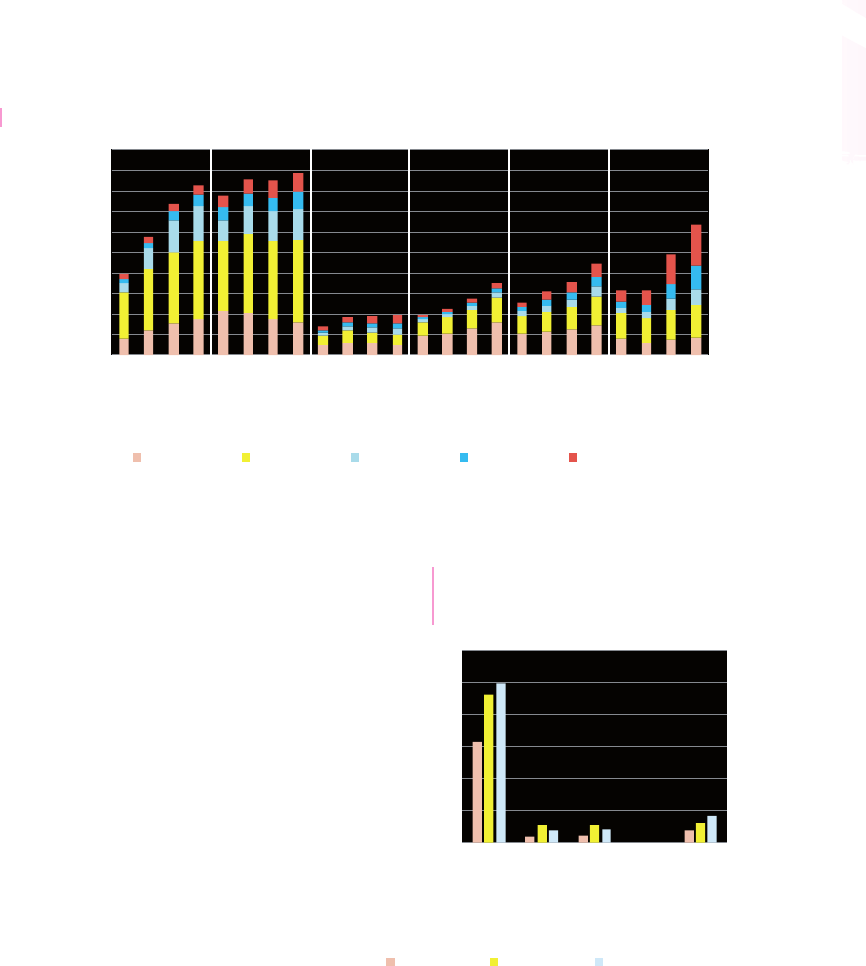

Fig. 1

Proportion of population aged 15–24 years and aged 50 years or older, 1980–2050

Source: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, World Population Prospects database,

2017 revision.

0

10

20

30

40

50

1980

1990

2000

2010

2020

2030

2040

2050

Proportion of population aged 50 and older

(percentage)

Latin America and the Caribbean

North America

Oceania

0

5

10

15

20

25

1980

1990

2000

2010

2020

2030

2040

2050

Proportion of population aged 15-24

(percentage)

World

Afr ic a

Asia

Europe

0

5

10

15

20

25

1980

1990

2000

2010

2020

2030

2040

2050

Percentage

World

Afr ic a

Asia

Europe

0

10

20

30

40

50

1980

1990

2000

2010

2020

2030

2040

2050

Percentage

Latin America and the Caribbean

North America

Oceania

15–24 years

50 years and older

12

WORLD DRUG REPORT 2018

past-month prevalence are indicators of current

levels of drug use in that population.

Given the paucity of drug use survey data from dif-

ferent regions, as well as the different measures of

prevalence and age groups used in the surveys avail-

able, it is difficult to construct a global comparison

of drug use between young people and older people.

In the following paragraphs, therefore, examples from

different countries and regions are presented to illus-

trate the extent of and compare drug use among the

different age groups in those countries and regions.

In all the regions for which data could be analysed

by age, current drug use is much higher among

young people than older people. People aged over

40 generally have different patterns of drug use than

young people, except when it comes to substances

such as opium and khat, which have a long tradi-

tion of use in particular societies or cultures. Older

people are typically not exposed as much as young

people to new drugs that enter the market and they

tend to follow the drug use patterns that were initi-

ated during their youth.

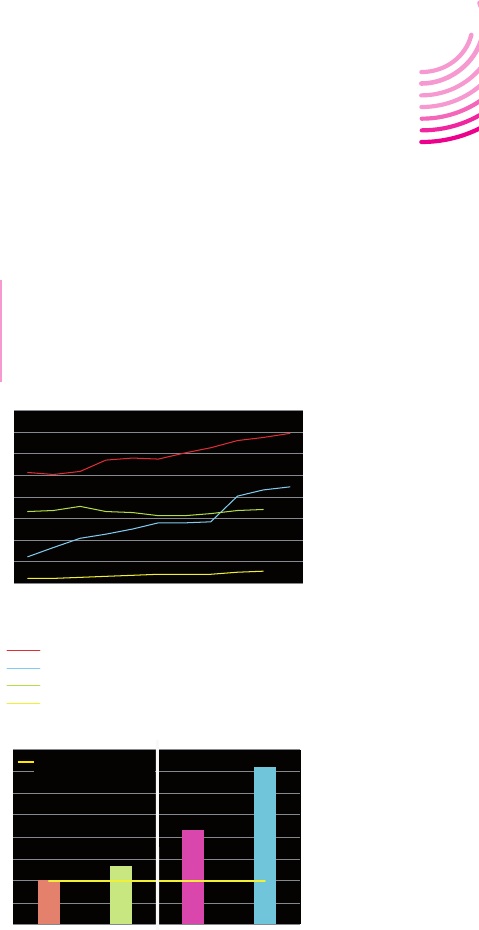

Europe

Data for the 28 States members of the European

Union, plus Norway and Turkey, show that the life-

time use in those countries of amphetamines and

“ecstasy” is between two and three times higher

among those aged under 35 than among older

people. Past-month use of most drugs is up to seven

times higher among young people. However, cur-

rent use of “ecstasy” is nearly 20 times higher among

Differences in the extent of lifetime drug use should

be interpreted taking into account the “cohort

effect”, which pertains to differences in drug use,

related attitudes and behaviours among people born

during specific time periods.

3

Persons who reach

the age of greatest vulnerability to drug use initia-

tion during a period when drugs are popular and

widely available are at particularly high risk of trying

drugs and, possibly, continuing to use them.

4

One

such example in the United States of America is of

the “baby boomers” (those who were born between

1946 and 1964), who had the highest rates of sub-

stance use as young people compared with previous

cohorts.

5

Typically, when a cohort of people starts

using a certain substance in large numbers, as in the

case of baby boomers, this is reflected in lifetime

prevalence in the general population in the years to

come, even when many of them discontinue drug

use at a later stage. Therefore, lifetime prevalence is

an indicator of the extent of exposure of the popu-

lation and different age groups within the population

at any point in time to drugs, while past-year and

3 Lloyd D. Johnston and others, Monitoring the Future

National Survey Results on Drug Use: 2016 Overview, Key

Findings on Adolescent Drug Use (Ann Arbor, Michigan,

Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan,

2017).

4 J.D. Colliver and others, “Projecting drug use among aging

baby boomers in 2020”, Annals of Epidemiology, vol. 16,

No. 4 (April 2006), pp. 257–265.

5 J. Gfroerer and others, “Substance abuse treatment need

among older adults in 2020: the impact of the aging baby-

boom cohort”, Drug and Alcohol Dependence, vol. 69, No. 2

(March 2003), pp. 127–135.

Fig. 2

Prevalence of drug use in Europe, by age group, 2017

Source: EMCDDA.

Note: The information represented is the unweighted average of data from the European Union member States, Norway and Turkey,

reporting to EMCDDA on the basis of general population surveys conducted between 2012 and 2015.

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

Life-

time

Past

year

Past

month

Past

year

Past

month

Life-

time

Past

year

Past

month

15–24 years 25–34 years 45–54 years

Percentage

Cannabis

Cocaine

Amphetamines

"Ecstasy"

13

4

DRUGS AND AGE A. Drug use among young people and older people

people aged 15–24 than among those aged 45–54.

By contrast, the rates of lifetime prevalence of

cocaine in Europe among those aged 15–24 and

those aged 45–54 are comparable, while lifetime use

of cannabis is much higher among those aged under

35. This may reflect differences in the age of initia-

tion for those substances, as well as different

historical levels of use among young people in

Europe.

In England and Wales, the annual prevalence of

drug use was highest in the 20–24 age group for all

drug types in the period 2016–2017. For those aged

45 and older, the annual prevalence of drug use was

considerably lower.

Bolivia (Plurinational State of)

In the Plurinational State of Bolivia, recent and cur-

rent use of almost all substances is substantially

higher among those aged 18–24 than among those

in other age groups; as seen in the majority of coun-

tries, cannabis is the most commonly used drug

across most age groups. The lifetime use of cannabis,

cocaine, stimulants and inhalants is up to two times

higher among those aged 18–24 than those aged 36

or older. In most cases, the past-year and past-month

use of those substances is also reported at much

higher levels among those aged 18–24 than among

the 36–50 age group. For instance, the past-year use

of cannabis is more than six times higher among

those aged 18–24 than those aged 36–50.

Fig. 3

Annual prevalence of drug use in England and Wales, fiscal year 2016–17

Source: United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, Office for National Statistics, “Drug misuse: findings from the

2016/17 crime survey for England and Wales”, Statistical Bulletin 11/17 (London, July 2017).

Fig. 4

Prevalence of drug use in the Plurinational State of Bolivia, by drug type and age group, 2014

Source: Plurinational State of Bolivia, National Council against Drug Trafficking (CONALTID), II Estudio Nacional de Prevalencia y

Características del Consumo de Drogas en Hogares Bolivianos de Nueve Ciudades Capitales de Departamento, más la Ciudad de El

Alto, 2014 (La Paz, 2014).

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

18

General

population,

aged 16–59

years

16–19

years

20–24

years

25–29

years

30–34

years

35–44

years

45–54

years

55–59

years

Percentgae

Cannabis

Cocaine

"Ecstasy"

Hallucinogens

Amphetami nes

Ketamine

Mephe dr one

General

population,

aged 16–59

years

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Life-

time

Past

year

Past

month

Life-

time

Past

year

Past

month

Life-

time

Past

year

Past

month

Life-

time

Past

year

Past

month

12–17 years 18–24 years 25–35 years 36–50 years

Percentage

Tranquillizers

Stimulants

Cannabis

Cocaine

Inhalants

14

WORLD DRUG REPORT 2018

among those aged 18–25 years is half of that among

those aged 50–54 years. This is probably the result

of a combination of factors, including the declining

trends in cocaine use that were observed in the

United States at the beginning of 2000 and the sharp

decline in such use that was observed in 2006. Con-

versely, the lifetime non-medical use of stimulants

and “ecstasy” among 18–25 year-olds is nearly three

times that of the older cohort, reflecting the more

recent appearance of these substances in the market.

The extent of past-month use of most drugs remains

up to three times higher and that of stimulants up

to seven times higher among those aged 18–25 than

among those aged 50–54. Hardly any current use

of “ecstasy” is reported among those 50 years and

older.

8

8 United States, Substance Abuse and Mental Health

Services Administration, Center for Behavioural Health

Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health

Services Administration, Key Substance Use and Mental

Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2016

National Survey on Drug Use and Health”, HHS Publication

No. SMA 17-5044, NSDUH Series H-52 (Rockville,

Maryland, 2017).

Conversely, the lifetime and past-year non-medical

use of tranquillizers, the second-most misused sub-

stance in the Plurinational State of Bolivia, is almost

twice as high among those aged 36–50, although

the past-month use of tranquillizers was reported at

similar levels among all age groups, except for 12–17

year olds.

6

Kenya

In Kenya, older people report a higher use of estab-

lished substances such as khat in different forms

(miraa and muguka) and cannabis (bhang and hash-

ish), while drugs that have become available in Africa

more recently, such as cocaine and heroin, are

reported to be used more frequently among those

aged 18–24. Among the general population, khat

and cannabis remain the two most commonly used

substances, with the highest lifetime and past-year

use among those aged 25–35. Conversely, the life-

time use of cocaine, heroin and prescription drugs

is nearly three times higher among people aged

18–24 than among those aged 36 years and older.

United States

Data on drug use among the general population in

the United States from 2017 show differences in the

lifetime, past-year and past-month use of people

aged 18–25 years compared with that of people aged

50–54. These differences are partly explained by the

cohort effect. The cohort effect is visible in the life-

time prevalence of those who were young in the late

1960s and in the 1990s, which were times when an

increase occurred in the use of numerous drugs by

young people. Lifetime use of substances that have

an established use over decades, such as cannabis,

opioid painkillers, tranquillizers and inhalants, is

comparable among those aged 50–54 and those aged

18–25.

7

For example, almost half of people in both

age groups have used cannabis at least once in their

lifetime. This pattern is different for cocaine and

stimulants. The lifetime prevalence of cocaine

6 Plurinational State of Bolivia, National Council against

Drug Trafficking (CONALTID), II Estudio Nacional de

Prevalencia y Características del Consumo de Drogas en Hoga-

res Bolivianos de Nueve Ciudades Capitales ae Departamento,

más la Ciudad de El Alto, 2014 (La Paz, 2014).

7 United States, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services

Administration, Center for Behavioural Health Statistics

and Quality, Results from the 2016 National Survey on Drug

Use and Health: Detailed Tables (Rockville, Maryland,

2017).

Fig. 5

Prevalence of drug use in Kenya, by

age group and drug type, 2012

Source: Kenya, National Authority for the Campaign Against

Alcohol and Drug Abuse, Rapid Situation Assessment of the

Status of Drug and Substance Abuse in Kenya (Nairobi, 2012).

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

Lifetime

Past yea r

Lifetime

Past yea r

Lifetime

Past yea r

Lifetime

Past yea r

15–17

years

18–24

years

25–35

years

36 years

and older

Percentage

Khat

Bhang

Cocaine

Heroin

Prescription drugs

DRUGS AND AGE B. Drugs and young people

15

4

Adolescence is the period when young people

undergo physical and psychological development

(including brain development); substance use may

affect that development. Adolescence is universally

a time of vulnerability to different influences when

adolescents initiate various behaviours, which may

include substance use. However, evidence shows

that the vast majority of young people do not use

drugs and those who do use them have been exposed

to different significant factors related to substance

use. The misconception that all young people are

equally vulnerable to substance use and harmful use

of substances ignores the scientific evidence, which

has consistently shown that individuals differ in

their susceptibility to use drugs. While specific influ-

ential factors vary between individuals, and no factor

alone is sufficient to lead to harmful use of sub-

stances, a critical combination of risk factors that

are present and protective factors that are absent

makes the difference between a young person’s brain

that is primed for substance use and one that is not.

Thus, from the perspective of preventing the initia-

tion of substance use, as well as preventing the

development of substance use disorders within the

context of the healthy and safe development of

young people, it is important to have a sound under-

standing of the patterns of substance use as well as

the personal social and environmental influences

that may result in substance use and substance use

disorders among young people.

B. DRUGS AND YOUNG

PEOPLE

Drugs affect young people in every part of the

world. Young people may use drugs, be involved

in the cultivation or production of drugs, or be

used as couriers. There are many factors at the

personal, micro (family, schools and peers) and

macro (socioeconomic and physical environment)

levels, the interplay of which may render young

people more vulnerable to substance use. Most

research suggests that early (12–14 years old) to

late (15–17 years old) adolescence is a critical risk

period for the initiation of substance use.

9

Many

young people use drugs to cope with the social and

psychological challenges that they may experience

during different phases of their development from

adolescence to young adulthood (ranging from the

need to feel good or simply to socialize, to personal

and social maladjustments).

10

9 United States, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services

Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and

Quality. “Age of substance use initiation among treatment

admissions aged 18 to 30”, The TEDS Report, (Rockville,

Maryland, July 2014).

10 Jonathan Shedler and Jack Block, “Adolescent drug use

and psychological health: a longitudinal inquiry”, American

Psychologist, vol. 45, No. 5 (1990), pp. 612–630.

Fig. 6

Prevalence of drug use in the United States of America, by age group, 2017

Source: United States, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioural Health Statistics and

Quality, Results from the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables (Rockville, Maryland, 2017).

For the purposes of the present section, as defined

by the United Nations, young people are considered

as those aged between 15 and 24 years.

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

Life-

time

Past

year

Past

month

Life-

time

Past

year

Past

month

Life-

time

Past

year

Past

month

12–17 years 18–25 years 50–54 years

Percentage

Cannabis

Cocaine

Methamphetamine

Misuse of pain relievers

Misuse of tranquillizers

Misuse of stimulants

Inhalants

"Ecstasy"

16

WORLD DRUG REPORT 2018

Patterns of drug use among

young people

Cannabis remains the most commonly

used drug

With the exception of tobacco and alcohol, cannabis

is considered the most commonly used drug among

young people. Epidemiological research, which is

mainly concentrated in high-income countries, sug-

gests that the perceived easy availability of cannabis,

coupled with perceptions of a low risk of harm,

makes cannabis, after tobacco and alcohol, the most

common substance used. Its use is typically initiated

in late adolescence and peaks in young adulthood.

11

Medical research shows that those who use cannabis

before the age of 16 face the risk of acute harm and

increased susceptibility to developing drug use dis-

orders and mental health disorders, including

personality disorders, anxiety and depression.

12, 13

Approximately 9 per cent of all people who experi-

ment with cannabis develop cannabis use disorders,

whereas 1 in 6 among those who initiate its use as

adolescents develop cannabis use disorders.

14

Between one quarter and one half of those who

smoke cannabis daily develop cannabis use

disorders.

15

The use of other drugs is typically preceded by can-

nabis use. When compared with non-users,

adolescent cannabis users have a higher likelihood

of using other drugs even when controlled for other

important co-variates such as genetics and environ-

mental influences.

16

Cannabis use during

adolescence and the subsequent use of other drugs

during young adulthood could be, among other

11 Megan Weier and others, “Cannabis use in 14 to 25 years

old Australians 1998 to 2013” Centre for Youth Substance

Abuse Research Monograph No. 1 (Brisbane, Australia,

Centre for Youth Substance Abuse, 2016).

12 Deidre M. Anglin and others, “Early cannabis use and

schizotypal personality disorder symptoms from adolescence

to middle adulthood”, Schizophrenia Research, vol. 137,

Nos. 1–3 (2012), pp. 45–49.

13 Shedler and Block “Adolescent drug use and psychological

health”.

14 Nora D. Volkow and others, “Adverse health effects of

marijuana use”, New England Journal of Medicine, 370(23)

(2014), pp. 2219–2227.

15 Ibid.

16 Jeffrey M. Lessem and others, “Relationship between

adolescent marijuana use and young adult illicit drug use”,

Behavior Genetics, vol. 36, No. 4 (2006), pp 498–506.

Cannabis use among

young people

In most countries, cannabis is the most widely used

drug, both among the general population and among

young people. A global estimate, produced for the

first time by UNODC, based on available data from

130 countries, suggests that, in 2016, 13.8 million

young people (mostly students) aged 15–16 years,

equivalent to 5.6 per cent of the population in that

age range, used cannabis at least once in the previ-

ous 12 months.

High prevalence of cannabis use was reported in North

America (18 per cent)

a

and in West and Central Europe

(20 per cent), two subregions in which past-year can-

nabis use among young people was higher than in

the general population in 2016. In some other sub-

regions, estimates suggest that cannabis use among

young people may be lower than among the general

population. More research is needed to understand

whether such a difference reflects the initiation of

cannabis use at a later age in the areas concerned or

is the result of comparatively higher under-reporting

of drug use behaviour in young people due to sigma.

Another factor may be that, at the age of 15–16, not

all young people are necessarily still at school in some

developing countries. Those in that age group who

are still at school may not be representative of their

age range regarding drug use behaviour; they may be

part of an elite exhibiting lower drug use than those

who are no longer at school.

a

Excluding Mexico: 23 per cent.

Annual prevalence of cannabis use among

the general population aged 15–64 years

and among students aged 15–16 years,

2016

Sources: UNODC, annual report questionnaire data and

government reports.

Note: the estimate of past-year cannabis use in young

people aged 15–16 years is based on school surveys in most

countries, hence the use of the term “students”.

11.0

8.0

7.6

5.1

1.9

11.4

11.6

6.6

13.9

2.7

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

Oceania Americas Africa Europe Asia

Annual prevalence (percentage)

General population (aged 15-64 years)

Students (aged 15-16 years)

General population (aged 15–64 years)

Students (aged 15–16 years)

Percentage

DRUGS AND AGE B. Drugs and young people

17

4

of drugs such as cocaine, tranquillizers, LSD and

inhalants was also reported among students in all

four countries. The proportion of those who initi-

ated drug use at a young age varied among males

and females in the survey, with the extent of drug

use among male students twice as high as among

female students. Polydrug use was also common

among the students, with one third of the students

in Colombia reported having used two or more

drugs concurrently in the past year, compared with

20 per cent in Ecuador and 7 per cent in Peru. Can-

nabis, cocaine, LSD and ecstasy were among the

substances most commonly reported as used

concurrently.

Spectrum of drug use in young people:

from nightlife settings to the use of

inhalants among street children

There are two contrasting settings that illustrate the

wide range of circumstances that drive drug use

among young people. On the one hand, drugs are

used in recreational settings to add excitement and

enhance the experience; on the other hand, young

people living in extreme conditions use drugs to

cope with the difficult circumstances in which they

find themselves. This section briefly describes drug

use among young people in those settings.

Use of stimulants in nightlife and

recreational settings

Over the past two decades, the use among young

people in high-income countries and those in urban

reasons, the result of common and shared environ-

mental factors. Adolescent users of cannabis may

come into contact with other cannabis-using peers

or drug dealers who supply other drugs, which may

result in increased exposure to a social context that

encourages the use of other drugs.

17, 18

For example,

a longitudinal study among adolescent twins showed

that the twin who used cannabis differentially pro-

gressed towards the use of other drugs, alcohol

dependence and drug use disorders at rates that were

twice or even five times higher than the twin who

did not use cannabis.

19

A comparative study of drug use among university

students (18–25 and older) in Bolivia (Plurinational

State of), Colombia, Ecuador and Peru in 2016

showed that, after alcohol and tobacco, cannabis

was the most commonly used drug among univer-

sity students. Some 20 per cent of the students in

Colombia had used cannabis in the past year, com-

pared with 5 per cent in Bolivia (Plurinational State

of) and Peru.

The reported use of other substances was also high-

est among university students in Colombia. The use

17 Ibid.

18 Wayne D. Hall and Michael Lynskey, “Is cannabis a

gateway drug? Testing hypotheses about the relationship

between cannabis use and the use of other illicit drugs”,

Drug and Alcohol Review, vol. 24, No. 1 (2005), pp. 39–

48.

19 Lessem and others, “Relationship between adolescent

marijuana use and young adult illicit drug use”.

Fig. 7

Prevalence of drug use among university students in Bolivia (Plurinational State of),

Colombia, Ecuador and Peru, 2016

Source: UNODC, III Estudio Epidemiológico Andino sobre Consumo de Drogas en la Población Universitaria: Informe Regional

2016 (Lima, 2017).

* Includes amphetamine, methamphetamine and "ecstasy".

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Life-

time

Past

year

Past

month

Life-

time

Past

year

Past

month

Life-

time

Past

year

Past

month

Life-

time

Past

year

Past

month

Bolivia

(Plurnational State of)

Colombia Ecuador Peru

Percentage

Cocaine

LSD

Ampahetamine-type stimulants*

Tranquillizers

Inhalants

Bolivia Colombia Ecuador Peru

(Plurnational State of)

18

WORLD DRUG REPORT 2018

centres of club drugs such as MDMA, or “ecstasy”,

methamphetamine, cocaine, ketamine, LSD and

GHB, has spread from isolated rave scenes to set-

tings ranging from college bars and house parties to

concerts. Some evidence on the approaches of young

people to these drugs has been collected in specific

contexts.

A qualitative study of club drug users in New York

City, for example, found that club drug use could

be grouped into three main patterns.

20

The first

group were inclined to use mainly cocaine, but infre-

quently, and were identified as “primary cocaine

users”. This group had no exposure to other drugs

or were disinclined to use multiple substances. The

second group were identified as “mainstream users”;

they were more inclined to experiment but were

focused on the most popular club drugs. This group

had a higher frequency of use and were also likely

to have used “ecstasy”, but were not likely to have

extensive experience with other club drugs. The

third group were identified as “wide-range users”;

they had a higher frequency of use of more than one

drug and were willing to experience “getting high”

in different ways. Although there is heterogeneity

among the third group, their drug use behaviours

have been associated with profound immediate and

long-term consequences.

Use of stimulants among socially integrated

and marginalized young people

Outside nightlife settings, stimulants such as meth-

amphetamine are also quite commonly used among

young people in most parts of the world. A qualita-

tive study in the Islamic Republic of Iran, identified

three groups of young methamphetamine users.

21

The majority were those who had started using

methamphetamine, known locally as shisheh, as a

way of coping with their current opioid use, either

to self-treat opioid dependence or to manage its

adverse events. Another, smaller group, were those

who had used shisheh during their first substance

20 Danielle E. Ramo and others, “Typology of club drug use

among young adults recruited using time-space sampling”,

Drug and Alcohol Dependence, vol. 107, Nos. 2 and 3

(2010), pp. 119–127.

21 Alireza Noroozi, Mohsen Malekinejad and Afarin Rahimi-

Movaghar, “Factors influencing transition to shisheh

(methamphetamine) among young people who use drugs

in Tehran: a qualitative study”, Journal of Psychoactive Drugs

(29 January 2018).

use or after a period of cannabis use, as novelty-

seeking and to experience a new “high”. The last

group constituted those who had switched to meth-

amphetamine use after participating in an opioid

withdrawal programme and abstaining from opioid

use for a period of time.

A review of studies in Asia and North America of

risk factors among young people using metham-

phetamine identified a range of factors associated

with methamphetamine use among socially inte-

grated (low-risk) and marginalized (high-risk)

groups of users.

22

Among socially integrated young

people, males were more likely than females to use

methamphetamine. Among that group, a history of

engaging in a variety of risky behaviours, including

sexual activity under the influence and concurrent

alcohol and opiate use, was significantly associated

with methamphetamine use. Sexual lifestyle and

risky sexual behaviour were also considered risk fac-

tors. Engaging in high-risk sexual behaviour,

however, could be a gateway for methamphetamine

use, or vice versa. Among marginalized groups,

females were more likely than males to use meth-

amphetamines. Young people who had grown up

in an unstable family environment or who had a

history of psychiatric disorders were also identified

as being at a higher risk of methamphetamine use.

Drug use among street children

While street children or street-involved youth are a

global phenomenon, the dynamics that drive chil-

dren to the streets vary considerably between

high-income and middle- and low-income coun-

tries.

23

Young people in this situation in high-income

countries have typically experienced conflict in the

family, child abuse and/or neglect, parental sub-

stance use or poverty. In resource-constrained

settings in low and middle-income countries, young

people may be on the street because of abject pov-

erty, the death of one or both parents or displacement

as a result of war and conflict in addition to the

reasons cited above.

22 Kelly Russel and others, “Risk factors for methamphetamine

use in youth: a systematic review”, BioMed Central

Pediatrics, vol. 8, No. 48 (2008).

23 Lonnie Embleton and others, “The epidemiology of

substance use among street children in resource-constrained

settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis”, Addiction,

vol. 108, No. 10 (2013), pp. 1722–1733.

DRUGS AND AGE B. Drugs and young people

19

4

physical abuse of street children is strongly associ-

ated with their sexual and physical victimization.

25,

26

These vulnerabilities, together with the fact that

street children may have families or parents with

substance use problems, contribute to the develop-

ment of substance use and psychiatric disorders

among street children.

High levels of substance use among street children

have been observed in many studies, but there are

no global estimates and their patterns of substance

25 Kimberly A. Tyler and Lisa A. Melnder, “Child abuse,

street victimization and substance use among homeless

young adults”, Youth and Society, vol. 47, No. 4 (2015), pp.

502–519.

26 Khaled H. Nada and El Daw A. Suliman, “Violence, abuse,

alcohol and drug use, and sexual behaviors in street children

of Greater Cairo and Alexandria, Egypt”, AIDS, vol. 24,

Suppl. 2 (2010), pp. S39–S44.

Not only do street children live, survive and grow

in an unprotected environment, but they also might

be abused or exploited by local gangs or criminal

groups to engage in street crimes or sex work. To

survive in such a hostile environment, street children

may do odd jobs such as street vending, hustling,

drug dealing or begging, or may engage in “survival

sex work”, which is the exchange of sex for specific

food items, shelter, money or drugs. Living in pre-

carious conditions also makes street children and

youth vulnerable to physical abuse, injuries and vio-

lence perpetuated by criminals, gangs or even local

authorities.

24

It has also been shown that sexual and

24 WHO, “Working with street children: module 1, a pro-

file of street children – a training package on substance

use, sexual and reproductive health including HIV/AIDS

and STDs”, publication No. WHO/MSD/MDP/00.14

(Geneva, 2000).

Table 1

Lifetime prevalence of different substances among street-involved children and youth in

resource-constrained settings

Source: Lonnie Embleton and others, “The epidemiology of substance use among street children in resource-constrained settings:

a systematic review and meta-analysis”, Addiction, vol. 108, No. 10 (2013), pp. 1722–1733.

a

Pooled analysis is a statistical technique for combining the results, in this case the prevalence from multiple epidemiological studies, to

come up with an overall estimate of the prevalence.

Substance used

Pooled analysis

a

of lifetime

prevalence (percentage)

Confidence interval

Alcohol 41 31–50

Tobacco 44 34–55

Cannabis 31 18–44

Cocaine 7 5–9

Inhalants 47 36–58

Children working and living on the streets: street-involved children

UNICEF defines street children or youth as any girl or boy

who has not reached adulthood, for whom the street

has become her or his habitual abode and/or source of

livelihood, and who is inadequately protected, supervised

or directed by responsible adults.

Street children are categorized by their level of involve-

ment in the streets into the following three groups:

1. Child of the streets: has no home but the streets.

The child may have been abandoned by their fam-

ily or may have no family members left alive. Such

a child has to struggle for survival and might move

from friend to friend, or live in shelters such as

abandoned buildings.

2. Child on the street: visits his or her family regu-

larly. The child might even return every night to

sleep at home but spends most days and some

nights on the street because of poverty, over-

crowding or sexual or physical abuse at home.

3. Child part of a street family: some children live

on the streets with the rest of their families, who

may have been displaced because of poverty, natu-

ral disasters or wars. They move their possessions

from place to place when necessary. Often, the

children in these families work on the streets with

other members of their families.

Source: WHO, “Working with street children: module 1, a

profile of street children – a training package on substance

use, sexual and reproductive health including HIV/AIDS

and STDs”, publication No. WHO/MSD/MDP/00.14

(Geneva, 2000).

20

WORLD DRUG REPORT 2018

interviewed for a study in Kenya reported using glue

in the past month, making it the most commonly

used substance among this group.

31

Other sub-

stances used by the children included alcohol,

tobacco, miraa (a local psychoactive herb), cannabis

and petrol. There were considerable differences in

the extent of substance use among different catego-

ries of street children. The prevalence of past-month

use was 77 per cent among those categorized as

“children of the street”, compared with 23 per cent

reported by “children on the street” (see box for the

definition.) Being male, older and having been on

the streets for a longer period of time has also been

associated with substance use.

32, 33

Similarly, the

absence of family has been consistently associated

with substance use among street-involved youth.

34

The use of psychoactive substances among street-

involved children and youth is often part of their

coping mechanism in the face of adverse experiences,

such as the physical and sexual abuse and exploitation

they experience being on the streets.

35

Therefore,

many street-involved children perceive inhalants as

a form of comfort and relief in a harsh environment,

as they numb feelings. In one study, “wanting to

forget or escape problems” was reported as the main

reason for substance use among street-involved

children. For many, peer pressure and the nature of

their jobs influenced their use of inhalants.

36

31 Lonnie Embleton and others, “Knowledge, attitudes, and

substance use practices among street children in western

Kenya”, Substance Use and Misuse, vol. 47, No. 11 (2012),

pp. 1234–1247.

32 Embleton and others, “The epidemiology of substance use

among street children in resource-constrained settings”.

33 Yone G. de Moura and others, “Drug use among street

children and adolescents: what helps?”, Cadernos Saúde

Pública, vol. 28, No. 6 (2012), pp. 1371–1380.

34 Embleton and others, “The epidemiology of substance use

among street children in resource-constrained settings”.

35 UNODC, Solvent Abuse among Street Children in Pakistan,

Publication No. UN-PAK/UNODC/2004/1 (Islamabad,

2004).

36 A. Elkoussi and S. Bakheet, “Volatile substance misuse

among street children in Upper Egypt”, Substance Use and

use may vary considerably. A systematic review and

meta-analysis of studies on substance use among

street children in resource-constrained settings

reported that inhalants were the most common sub-

stance used, with a pooled analysis

27

putting lifetime

prevalence of their use among street-involved chil-

dren and youth at 47 per cent.

28

While the use of

inhalants was found in all regions, use of cocaine

among street-involved children was reported mainly

in South and Central America, and alcohol use

mostly in Africa and South and Central America.

Most of the scientific literature on the subject reports

the use of inhalants or volatile substances among

street children as a common phenomenon.

29

Such

substances include paint thinner, petrol, paint, cor-

rection fluid and glue. They are selected for their

low price, legal and widespread availability and abil-

ity to rapidly induce a sense of euphoria among

users.

30

There are also differences in the extent of substance

use among street children that depend on the dura-

tion of their exposure to the street environment.

Some 58 per cent of street-involved children

27 A pooled analysis is a statistical technique for combining

the results, in this case the prevalence from multiple

epidemiological studies, to arrive at an overall estimate of

the prevalence.

28 Embleton and others, “The epidemiology of substance use

among street children in resource-constrained settings”. The

meta-analysis looked at 50 studies on substance use among

street children. Out of 27 studies, 13 covered resource-

constrained settings in Africa, South and Central America,

Asia, including the Middle East, and Eastern Europe.

29 L. Baydala, “Inhalant abuse”, Paediatrics Child Health, vol.

15, No. 7 (September 2010), pp. 443–448.

30 Colleen A. Dell, Steven W. Gust and Sarah MacLean,

“Global issues in volatile substance misuse”, Substance Use

and Misuse, vol. 46, Suppl. No. 1 (2011), pp. 1–7.

Different ways of using

inhalants

Sniffing: solvents are inhaled directly from a con-

tainer through the nose and mouth.

Huffing: a shirt sleeve, sock or a roll of cotton

is soaked in a solvent and placed over the nose

or mouth or directly into the mouth to inhale the

fumes.

Bagging: a concentration of fumes from a bag is

placed over the mouth and nose or over the head.

Sudden sniffing death

The intensive use of volatile substances (even during

only one session) may result in irregular heart

rhythms and death within minutes, a syndrome

known as “sudden sniffing death”.

DRUGS AND AGE B. Drugs and young people

21

4

and more than half of adolescent street-involved

girls had received payment for sex or had been forced

to have sex.

41

The above-mentioned study in Paki-

stan showed that slightly more than half of street

children had exchanged sex for food, shelter, drugs

or money.

Street-involved children remain one of the most

vulnerable, marginalized and stigmatized groups.

They are exposed to abuse and violence, drug use

and other behaviours that put them at high risk of

HIV and tuberculosis infection, and other condi-

tions including malnutrition and general poor

health. Despite these vulnerabilities, they are often

the most likely to be excluded from receiving any

form of social or health-care support to ameliorate

their condition.

42

Polydrug use remains common among

young people

As with adults, a major characteristic of drug use

among young people is the concurrent use of more

than one substance. Polydrug use remains fairly

common among both recreational and regular drug

users. However, polydrug use among young adults

is symptomatic of more established patterns of use

of multiple substances, which is linked to an

increased risk of developing long-term problems as

well as of engaging in acute risk-taking through

binge drinking or binge use of stimulants such as

“ecstasy” at rave parties or similar settings.

43

Evidence collected in some regions and countries

shows examples of the level and combinations of

substances typically used by young people. In

Europe, a wide variation in patterns of polydrug use

among the population of drug users was reported,

ranging from occasional alcohol and cannabis use

to the daily use of combinations of heroin, cocaine,

alcohol and benzodiazepines.

44

The most common

polydrug use combinations reported in Europe

41 Busza and others, “Street-based adolescents at high risk of

HIV in Ukraine”.

42 UNICEF, The State of the World’s Children 2012: Children

in an Urban World (United Nations publication, Sales No.

E.12.XX.1).

43 EMCDDA, Polydrug Use: Patterns and Response (Luxem-

bourg, Office for Official Publications of the European

Communities, 2009).

44 Ibid.

The injecting of drugs is also reported among street-

involved youth. A cross-sectional study in Ukraine

reported that 15 per cent of the children living on

the streets were injecting drugs. Nearly half of them

shared injecting equipment and 75 per cent were

sexually active.

37

In another study among street

children in Pakistan, cannabis and glue were the

drugs most commonly used by the respondents (80

per cent and 73 per cent, respectively), while 9 per

cent smoked or sniffed heroin and 4 per cent

injected it.

38

Similarly, in a Canadian prospective

cohort study among street-involved youth, 43 per

cent of participants reported injecting drugs at some

point.

39

Moreover, being helped with injecting was

seen among a more vulnerable subgroup of

respondents, i.e., those who were young and/or

female. Those respondents were more likely to

receive help in injecting methamphetamine than

heroin or cocaine, in particular because of the higher

daily frequency of injecting reported for

methamphetamine.

Sexual abuse and exploitation is a common feature

in the lives of street-involved children and may con-

tribute to substance use. A study in Brazil reported

that a significantly higher proportion of street-

involved boys (two thirds) as compared with girls

(one third) reported having had sex at some point

in their lives. Over half of the respondents reported

becoming sexually active before the age of 12.

Almost half of the street-involved children inter-

viewed reported more than three sexual partners in

the past year. One third of the children reported

having had unprotected sex under the influence of

drugs or alcohol.

40

In Ukraine, a study showed that

nearly 17 per cent of street-involved adolescent boys

Misuse, vol. 46, Suppl. No. 1 (2011), pp. 35–39.

37 Joanna R. Busza and others, “Street-based adolescents at

high risk of HIV in Ukraine”, Journal of Epidemiology and

Community Health, vol. 65, No. 11 (2011), pp. 1166–1170.

38 Susan S. Sherman and others, “Drug use, street survival,

and risk behaviours among street children in Lahore,

Pakistan”, Journal of Urban Health, vol. 82, Suppl. No. 4

(2005), pp. iv113–iv124.

39 Tessa Cheng and others, “High prevalence of assisted

injection among street-involved youth in a Canadian

setting”, AIDS and Behaviour, vol. 20, No. 2 (20160, pp.

377–384.

40 Fernanda T. de Carvalho and others, “Sexual and drug

use risk behaviours among children and youth in street

circumstances in Porto Alegre, Brazil”, AIDS and Behaviour,

vol. 10, Suppl. No. 1 (2006), pp. 57–66.

22

WORLD DRUG REPORT 2018

Pathways to substance use disorders

Integrative developmental model for

understanding pathways to substance

use and harmful use of substances

Persons who initiate substance use and later develop

substance use disorders typically transition through

a number of stages, including initiation of use, esca-

lation of use, maintenance, and, eventually,

addiction.

48, 49

These pathways fluctuate in the use

and desistance or cessation of drug use. Some groups

of users may maintain moderate use for decades and

never escalate. Others may exhibit intermittent peri-

ods of cessation, abstain permanently, or escalate

rapidly and develop substance use disorders.

Understanding the risk factors that determine

whether experimental users continue on a path to

harmful use of substances is a question that has com-

pelled researchers and practitioners to try to better

understand, predict and appropriately intervene in

these distinct etiological pathways.

The “ecobiodevelopmental” theoretical framework,

founded on an integration of behavioural science

fields, can help elucidate substance use pathways.

In this model, human behaviour is viewed as the

result of emerging from the “biological embedding”

50

48 On the basis of the International Statistical Classification