A m b e r W a v e s o f G a i n :

How the

F a r m Bureau Is

Reaping Profits at the

Expense of America’s

Family Far m e r s ,

Taxpayers and the

E n v i r onment

April, 2000

AMBER WAVES OF GAIN:

DEDICATION

This report is dedicated to the memory of Joseph Y. Resnick, the two-term congressman

from New York who first exposed the Farm Bureau as not being the organization of farmers it

claims to be. Resnick launched an investigation of the Farm Bureau in 1967 and resumed it

after leaving politics in1969. He died later that year, but the probe he initiated and funded

continued, culminating two years later in the publication of the book Dollar Harvest, a major

exposé about the Farm Bureau by former Resnick aide Samuel R. Berger. This report builds on

the foundation laid by Resnick and resurrects his call for the dealings of the Farm Bureau to be

closely examined on Capitol Hill.

A M B E R W A V E S O F G A I N

iii

Foreword..............................................................................................iv

Executive Summary...............................................................................v

Introduction: The Farm Lobby Colossus..............................................1

1. Emphasizing the Bottom Line..........................................................8

2. Plumping for Factory Hog Farms ..................................................19

3. Changing Rural America................................................................30

4. Cooperating with Conglomerates...................................................34

5. Taking Care of Business..................................................................46

6. Pushing an Anti-Wildlife Agenda...................................................56

7. Spinning the Global Warming Issue...............................................62

8. Putting Pest Control Before Human Health...................................66

9. Aligning With the Extreme Right...................................................75

Conclusion: A Call to Common Ground............................................84

Appendix 1. Farm Bureau Connections..............................................85

Appendix 2. Tax Treatment of Unrelated Business Income for

Agricultural and Horticultural Organizations................90

Table of Contents

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

PRINCIPAL AUTHOR:

Vicki Monks

CONTRIBUTING AUTHORS:

Robert M. Ferris, Vice President for Species Conservation Program, Defenders of Wildlife

Don Campbell

PROJECT MANAGER:

Robert M. Ferris

RESEARCH COORDINATOR:

Heather Pellet, Species Conservation Program Coordinator, Defenders of Wildlife

RESEARCH:

Scotty Johnson, Rural Outreach Coordinator, Grassroots Environmental Effectiveness Network (GREEN)

Roger Featherstone, Director, GREEN

Carol/Trevelyan Strategy Group (Dan Carol, Catharine Gilliam)

Rob Roy Smith, Species Conservation Program Intern, Defenders of Wildlife

William J. Snape III, Vice President for Law and Litigation, Defenders of Wildlife

Joe McCaleb

EDITING AND PRODUCTION:

James G. Deane, Vice President for Publications, Defenders of Wildlife

Kate Davies, Publications Manager, Defenders of Wildlife

Maureen Hearn, Editorial Associate, Defenders of Wildlife

DESIGN:

Cissy Russell

ABOUT DEFENDERS OF WILDLIFE

Defenders of Wildlife is a leading nonprofit conservation organization recognized as one of the nation’s most progres-

sive advocates for wildlife and its habitat. Defenders uses education, litigation, research and promotion of conservation

policies to protect wild animals and plants in their natural communities. Known for its effective leadership on endan-

gered species issues, Defenders also advocates new approaches to wildlife conservation that protect species before they

become endangered. Founded in 1947, Defenders of Wildlife is a 501(c)(3) membership organization headquartered in

Washington, D.C., and has nearly 400,000 members and supporters.

Copyright 2000 by Defenders of Wildlife, 1101 Fourteenth Street NW, Washington, D.C. 20005; 202-682-9400.

Visit our website at www.defenders.org and our children’s website at www.kidsplanet.org.

Cover Illustration: David Chen/The Stock Illustration Source

Printed on recycled paper.

Foreword

I

n December, 1997, Defenders of Wildlife heard deeply disturbing news. A federal district

judge in Wyoming had ruled that Yellowstone and central Idaho wolf reintroductions car-

ried out by the federal government in 1995 and 1996 were unlawful and that the thriving

new wolf populations must be removed. Since their former territories in Canada were by

then occupied by other wolves and there wasn’t room for them in the nation’s zoos, it

appeared that the wolves would have to be killed.

The ruling threatened to erase years of hard work by the government and conservation-

ists and to destroy what has been called the most popular and successful wildlife restoration

effort of the 20th century, an effort in which Defenders had been a leader for two decades.

The most significant plaintiff in the lawsuit responsible for the court decision was the

American Farm Bureau Federation (AFBF — or the Farm Bureau). AFBF and its state and

county units regularly oppose not only measures to sustain and recover endangered species

like the wolf but many important environmental protection efforts. The organization also is

negative toward other widely accepted laws and public policies. Its 1998 policy manual, for

example, advocated repeal of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, opposed registration and

licensing of firearms and advocated abolishing the U.S. Department of Education.

From its name, one might suppose that the Farm Bu r eau exists to serve American family

farmers. In reality the Farm Bu reau is a gigantic agribusiness and insurance conglomerate. T h e

majority of its “m e m b e r s” are not farmers, but customers of Farm Bu r eau insurance companies

and other business ve n t u res. Yet the organization’s nonpro fit status allows it to use the U.S. tax

code to help build a financial war chest with which it pursues an extreme political agenda,

while doing little for — and sometimes working against — America’s family farmers.

We decided that we should try to find out more about this politically powerful organiza-

tion and make what we learned available to the public. The result is the accompanying

report. We would have liked to examine more of the Farm Bureau’s operations but lacked

the time and resources to do so. We believe the public deserves to learn the full facts about

this huge financial conglomerate that purports to be the voice of America’s family farmers.

A M B E R W A V E S O F G A I N

Foreword

Rodger Schlickeisen

President, Defenders of Wildlife

A M B E R W A V E S O F G A I N

vi

Foreword

T

he American Farm Bureau Federation (AFBF) — with its roughly 3,000 constituent

state and county farm bureaus — ranks among the richest and most powerful non-

governmental organizations in America. AFBF claims to have more than 4.9 million

members. It has artfully portrayed itself as the voice and champion of our nation’s fam-

ily farmers for nearly 80 years.

The vast majority of the Farm Bu re a u’s members, howe ve r, are either policyholders of one

of numerous insurance companies affiliated with state farm bureaus or are customers of other

farm bureau business ve n t u res. (At latest count there we re some 54 farm bureau insurance

companies.) Such members have no say in establishing or carrying out Farm Bu reau policies

and, in most cases, have no particular interest in agriculture .

AFBF spends a great deal of money and time opposing environmental laws such as the

Endangered Species Act, the Clean Air and Safe Drinking Water Acts, wetlands laws and

pesticide regulations. But the organization’s views may have more to do with its own finan-

cial interests than with the views of its members or the needs of the family farmer.

AFBF is allied with some of the nation’s biggest agribusinesses. It has large investments

in the automobile, oil and pesticide industries, often supports factory farming rather than

family farming and regularly opposes government regulation to reduce air and water pollu-

tion and pesticide use and to protect wildlife, habitat, rural amenities and food quality. It is

critical of efforts to counter global warming. It has opposed the registration and licensing of

firearms. It has advocated repeal of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, one of the nation’s key civil

rights laws. It has advocated abolition of the federal Department of Education and of the

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. It has launched lawsuits to halt reintroduction of endangered

gray wolves. It is allied politically with, and provides funding for, right-wing interests and

the so-called wise-use movement, which works for the supremacy of private property owner-

ship and against the protection and conservation of public lands.

The Farm Bureau’s policies are set by voting delegates at its annual meetings. Many high

officers of the national and state farm bureaus also serve as officers or directors of the insur-

ance companies and of Farm Bureau cooperatives and other businesses.

Defenders of Wildlife first investigated the Farm Bureau because of the longstanding

Farm Bureau lobbying campaigns against wildlife and environmental protections. We found,

Executive Summary

A M B E R W A V E S O F G A I N

vii

Foreword

however, that the Farm Bureau not only opposes our core mission but also works actively

against the interests of rural communities and mainstream America.

A significant problem facing rural communities in the last decade has been the rise in

factory farms which produce hundreds of thousands of hogs every year. The Farm Bureau

has sided with the corporations that own and operate these farms, often to the detriment

of rural communities and local family farmers. Beyond significant pollution issues, these

pig factories are putting family farms out of business.

Over the last decade, as market concentration has become an overwhelming force in

American agriculture, hundreds if not thousands of family-owned farms have been forced

out of business. The Farm Bureau supports, through investments and political clout, this

concentration of the agricultural industry and, indirectly, the destruction of rural America.

When the cooperative farm bureau system was first set up in 1922, it empowe red farmers

and other rural residents to get the goods and services they needed while enabling them to

sell their products at a better price. Un f o rt u n a t e l y, what was once a beneficial arrangement

for farmers and consumers has drastically changed. Many Farm Bu re a u - a f filiated co-ops are

n o w multibillion-dollar operations that compete directly with their farmer members.

Fu rt h e r m o re, many of these cooperatives are partnering with the ve ry companies re s p o n s i b l e

for the agribusiness megamergers that are putting smaller farmers out of business.

As can be expected, the Farm Bureau has taken positions that benefit its business inter-

ests or investments. Other lobbying priorities are more difficult to fathom. However, the

theme that runs through all Farm Bureau policies seems to be less regulation and more

power for business interests. To further this agenda, the Farm Bureau has developed close

ties to the corporate-led property rights movement.

Plenty of farmers and ranchers see common ground with environmentalists. Some are

Farm Bureau members who cannot make their voices heard. Others have dropped mem-

bership and are working for change in other ways. Yet the Farm Bureau has pursued a

deliberate strategy of fostering enmity between farmers and environmentalists, two groups

that could benefit from working together.

A M B E R W A V E S O F G A I N

1

“...the Fa rm Bu r eau is far more than simply

an organization of farmers, as it so often claims.

The nation’s biggest farm organization has been

quietly but systematically amassing one of the

largest business networks in America, while

t u rning its back on the deepening crisis of the

f a rmers whom it supposedly re p re s e n t s . . . .”

— Samuel R. Berger, Dollar Harvest.

T

he majority of Americans may be only

vaguely aware of the existence of the

American Farm Bu reau Federation (AFBF),

although it is a huge and immensely powe rf u l

organization that claims to speak for farmers on

many public policy issues and has a signific a n t

i n fluence on decisions of government at all leve l s .

Su rveys by Fo rtune magazine regularly rank

AFBF as one of the top 25 most potent special-

i n t e r est groups in Washington, D.C. The organi-

zation is no less formidable a presence in state

capitals, county seats and rural communities. And

its influence extends into business and fin a n c i a l

c i rcles, to which it has major and pro fitable ties.

With more than 4.9 million members and affil-

iated organizations in eve ry state, AFBF — famil-

iarly called simply the Farm Bu reau — has colossal

political clout in Congress, state legislatures and

county commissions.“They are an incredibly pow-

e rful lobby,” says Sam Hitt of Fo rest Gu a r dians, a

Santa Fe, New Mexico, environmental gro u p. Hi t t

has run up against the Farm Bu reau time and

again on environmental issues, such as pro t e c t i o n

of streamside ecosystems. “Legislators seem to go

g o o g l e - e yed when they see them walk through the

d o o r, and that’s caused the loss of a lot of our

wildlife heritage,” he says.

One measure of the Farm Bu reau empire’s size

is the $200 million or more that it takes in ye a r l y

in membership dues. The national, state and

county farm bureaus also control insurance com-

panies producing annual re v enue of some $6.5

billion and cooperatives producing re venue of

some $12 billion. And farm bureaus earn re ve n u e

f rom consulting, satellite TV and Internet serv i c e s

and a bank headed by AFBF’s pre s i d e n t .

AFBF spends considerable money and energy

fighting such environmental initiatives as the

Endangered Species Act, the Clean Water, Clean

Air and Safe Drinking Water Acts, wetlands laws,

pesticide regulations and efforts to curb global

warming. But the Farm Bureau’s views may have

more to do with the organization’s own financial

interests than with the needs of family farms.

The Farm Bureau’s emotionally charged

attacks on environmental regulations seem

intended at least partly to divert the attention of

I N T R O D U C T I O N

The Farm Lobby Colossus

A M B E R W A V E S O F G A I N

2

farmers from the real issues facing agriculture

today. For years this strategy apparently worked.

But interviews with cattle ranchers, hog produc-

ers and farmers across the nation suggest that

many no longer believe these issues have any-

thing to do with the troubles plaguing agricul-

ture, and they no longer trust the Farm Bureau

to act on their behalf.

The United States is in the midst of one of

the worst agricultural crises in decades. Hog, cat-

tle and grain prices for farmers have collapsed at

the same time that food costs for consumers

remain high. Food production at all levels is

becoming more and more concentrated in the

hands of enormous agribusinesses, including

those of the AFBF network, while thousands of

family farms go under. AFBF and its affiliates

have not only advocated policies that have con-

tributed to the crisis but are actively benefiting

from the demise of family farms.

The Farm Bureau began its rise to power in

1911 when the Chamber of Commerce in

Binghamton, New York, set up the first county

farm bureau to sponsor an extension agent pro-

vided by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

From that time through the 1950s, a cozy rela-

tionship persisted between the private farm

bureaus and federal agricultural agents — a rela-

tionship so close that many farmers mistakenly

believed that the farm bureaus and the govern-

ment were one and the same, according to a his-

tory of the Farm Bureau in The Corporate

Reapers: The Book of Agribusiness by A.V. Krebs

(Essential Books, 1992). In 1954, the

Department of Agriculture ordered its agents to

stop accepting free office space and gratuities

from farm bureaus, but close connections

between the two entities remained. Ironically,

this association with the federal government —

and the consequent access to federal crop pro-

grams and technical information — helped

establish AFBF’s dominance as a farmers’ organi-

zation. These days, AFBF complains that the

federal government is too intrusive, particularly

in regard to environmental regulations, which

AFBF claims are overly burdensome to farmers.

But many of the causes that the Farm Bureau

champions, including less pesticide regulation,

relate at least as much to the financial interest of

the Farm Bureau as to the needs of farmers.

Dean Kleckner, AFBF president from 1986

to January, 2000, reserved particular invective for

the Food Quality Protection Act, which dire c t s

the En v i ronmental Protection Agency (EPA) to

set standards for pesticide residues in food at lev-

els low enough to protect the health of infants

and children. “Sane people do wonder what these

kids will eat . . . when the government closes the

p roduce department at our gro c e ry store s , ”

Kleckner wrote in a newspaper column in which

he suggested that EPA’s “bureaucratic madness”

would result in bans on all agricultural chemicals.

The Farm Bu reau may genuinely fear that agri-

c u l t u re will suffer if farmers must reduce their use

of chemicals, but Farm Bu re a u - a f filiated compa-

nies also hold stock in corporations that manufac-

t u r e pesticides, and presumably those inve s t m e n t s

might suffer as well.

WIDE-RANGING BUSINESS INTERESTS

Agricultural cooperatives under the direct

control of state farm bureaus earn significant rev-

A M B E R W A V E S O F G A I N

enues from pesticides and market them aggres-

sively. In addition, according to corporate docu-

ments, some 54 Farm Bureau-affiliated insurance

companies earn a total of more than $6.5 billion

annually in net premiums. The farm bureaus also

h a ve investments in banks, mutual-fund and

fin a n c i a l - s e rvices firms, grain-trading companies

and other businesses. Many of those businesses in

turn own stock in oil and gas, pulp and paper,

t i m b e r, railroad, automobile, plastics, chemical,

steel, pesticide, communications, electronics and

c i g a r ette companies and even a nuclear powe r

plant. The lists of stocks held by Farm Bu re a u

companies read like a who’s who of corporate

h e a v y w eights: Philip Morris, We ye r h a e u s e r,

Du P ont, Union Carbide, AT & T, Fo r d Mo t o r,

Raytheon (a leading manufacturer of tactical mis-

siles), International Pa p e r, CBS, Tyson Fo o d s ,

A r cher Daniels Midland (ADM) and many more .

(For a list of farm bureau insurance companies

and other farm bureau business affiliations see

Appendix 1, “Farm Bureau Connections.” )

In a 1998 interview, AFBF Washington lob-

byist Dennis Stolte claimed ignorance of these

financial interests and insisted that the insurance

and other businesses have little to do with AFBF.

“That’s not the Farm Bureau,” he said. “Our

members are farmers for the most part. They’re

people who are interested in promoting agricul-

ture.” Nevertheless, comparisons of the boards of

directors of Farm Bureau-affiliated businesses

and Farm Bureau organizations themselves show

substantial overlap. In many cases, the individu-

als and boards controlling the businesses also

control the state farm bureaus. Frequently, much

of the profit earned by these businesses reverts to

the farm bureaus. The California Farm Bureau,

for example, reported total revenue of $37 mil-

lion in 1996. This and the examples that follow

indicate just why AFBF would be inclined to

function more like a big-business interest than

the advocate of family farmers:

The Illinois Farm Bu reau (also known as the

Illinois Agricultural Association or IAA) is the

majority stockholder in a group of inve s t m e n t

funds run by IAA Trust Company, which man-

ages stock, bond and money-market funds wort h

m o re than $356 million. Illinois Farm Bu re a u

also owns 95 percent of IAA Trust Company. In

1998, the IAA Trust Funds earned $10.6 million

in interest and dividends from stocks and other

i n vestments, and the value of IAA Tru s t’s port f o-

lio increased by more than $46 million for the

year ending June 30, 1999. Ac c o rding to an

Oc t o b e r, 1999, re p o rt filed with the Se c u r i t i e s

and Exchange Commission (SEC), Illinois Fa r m

Bu r eau president Ronald Wa rfield is also pre s i-

dent of IAA Trust and serves on AFBF’s board as

well as the boards of several of AFBF’s affil i a t e d

companies. Ac c o rding to the SEC re p o rt, nearly

all of the top officers and directors of IAA Tru s t

a r e also on the board of the Illinois Farm Bu re a u .

Twenty-one board members serve both organiza-

tions. The IAA investment funds pay the IAA

Trust Company more than $2 million a year to

provide advice on which stocks to buy and when.

These same Farm Bu reau officers are in

charge of 52 companies directly owned by or

closely affiliated with the Illinois Farm Bu re a u .

The list includes Country Companies In s u r a n c e ,

real estate brokerage firms, credit and fin a n c i a l

s e rvices companies, an export company headquar-

3

A M B E R W A V E S O F G A I N

4

t e r ed in Barbados, West Indies, oil and gas com-

panies and Grow m a rk, an international agricul-

tural cooperative with close business ties to the

agribusiness giant Archer Daniels Mi d l a n d

( A D M ) .

Nationwide Insurance of Columbus, Ohio,

with $74 billion in assets and $12 billion in

annual sales, grew out of the Ohio Farm Bureau.

Even though the insurance company split off

from the Ohio bureau in 1948, connections

remain close. According to the Columbus

Dispatch, Ohio Farm Bureau presidents and past

presidents routinely are elected to the board of

Nationwide and the bureau nominates a majority

of the board. Irv Bell, president of the Ohio

Farm Bureau until early 1998, now sits on

Nationwide’s board. Nationwide’s long-time

chairman and chief executive officer, George

Dunlap, was also an Ohio Farm Bureau director

for 15 years and director of a county farm

bureau for 25 years.

AFBF owns 42.7 percent of American

Agricultural Insurance Company (AAIC). T h i rt y -

t h ree other Farm Bu r eau insurance companies

own the rest of AAIC. AAIC sells reinsurance,

insuring other insurance companies against the

kinds of huge losses that might be caused by nat-

ural disasters — a risky but profitable business.

According to financial reports, in early 1999

AAIC had assets of more than $575 million and

a surplus of $285 million. The president of

AFBF is also AAIC’s president. AAIC employs

AFBF’s secretary and treasurer as secretary and

treasurer of the reinsurance company. In fact,

AAIC’s entire board is chosen from among AFBF

board members. On March 31, 1999, AAIC

announced plans to purchase the reinsurance

division of Nationwide Insurance. The terms

were not disclosed. According to a news release,

Nationwide’s president Richard D. Crabtree said

the sale to AAIC is a good fit because the two

companies “share a cooperative heritage . . . .”

Other examples of overlapping farm bureau

organizational and business interests include:

• New York Farm Bureau president John

Lincoln serves as vice chairman of the board of

Farm Family Insurance Companies. Farm Family

also shares office space with the New York Farm

Bureau.

• Kentucky Farm Bureau Federation execu-

tive vice president David S. Beck also is corpo-

rate secretary of Kentucky Farm Bureau Mutual

Insurance Company.

• Farm Bureau Town and Country Insurance

and Farm Bureau Life Insurance of Missouri are

owned by Missouri Farm Bureau Services, Inc.,

which is controlled by the Missouri Farm Bu re a u .

• All directors of Western Farm Bureau

Mutual Insurance are also directors of the New

Mexico Farm and Livestock Bureau.

• Former Wyoming Farm Bureau Federation

president and AFBF executive committee mem-

ber Dave Flitner also served as president of

Mountain West Farm Bureau Mutual Insurance

and Farm Bureau Life Insurance. Flitner is better

known for his close ties with former Interior

Secretary James Watt and for his tenure as presi-

dent of the Mountain States Legal Foundation,

one of the nation’s most active anti-environmen-

tal legal groups. Mountain States, a co-plaintiff

in the Farm Bureau Yellowstone/Idaho wolf law-

suit, also provided legal representation for the

Farm Bureau in that lawsuit. Flitner once com-

pared reintroduction of wolves to “inviting in the

AIDS virus.” He also proposed cutting agricul-

ture programs to lower the federal deficit.

So vast is this web of interlocking companies

with interlocking boards that it is nearly impossi-

ble to estimate the true extent of the Farm Bu r-

e a u’s financial powe r. It’s equally difficult to gauge

whether or how much individual farm bure a u

o f ficers who sit on multiple boards of dire c t o r s

p ro fit from these businesses, since individual hold-

ings in the companies are never disclosed.

In addition to their other businesses, state farm

b u reaus are now providing digital television, satel-

lite, advanced communication, long-distance and

cellular telephone services and high-speed In t e r n e t

access. Farm Bu reau leaders seem reluctant to dis-

cuss these enterprises with outsiders. AFBF exc l u d-

ed members of the press from a 1998 communica-

tions conference in Santa Fe, New Me x i c o .

This exclusion of the press is not surprising.

AFBF works hard to maintain its image as a

grassroots advocate for family farms. Too much

emphasis on AFBF’s outside business interests

might spoil that illusion. “There’s an impression

that this is a huge organization of farmers,” says

former Texas agriculture commissioner Jim

Hightower, who now hosts a syndicated radio

talk show. “But they are no more a family farmer

organization than is State Farm Insurance. Just

because you have the word farm in your name

doesn’t mean you really represent farmers.”

As agriculture commissioner, Hightower had

firsthand experience with the Farm Bureau’s jeal-

ous protection of its financial interests. In the

mid-1980s, when the European Community was

considering a ban on imports of hormone-

enhanced meat, Hightower tried to recruit Texas

cattle producers to raise hormone-free beef for

export. He figured that ranchers could take

advantage of the new market for “organic” beef if

they acted quickly. The Texas Farm Bureau inter-

preted Hightower’s actions as disparagement of

hormone-enhanced cattle and launched a suc-

cessful campaign to drive him from office. After

the smoke cleared, the Dallas Times Herald

reported that Texas Farm Bureau-controlled

companies owned $1.3 million worth of stock in

Syntex, a cattle growth hormone manufacturer.

INFLATED MEMBERSHIP RANKS

“If these people lose their prestige as the

spokesmen for agriculture, they’re just another

insurance lobby, and insurance lobbies are a

dime a dozen. That’s why they don’t like to talk

about how many of those members are actually

farmers.”

— Missouri farmer Scott Dye.

If proof is still needed that AFBF is not quite

the grassroots farming organization that it repre-

sents itself to be, it would be found in the

AFBF’s own membership rolls. The Department

of Agriculture estimates the number of full-time

American farmers at just over 1 million, so clear-

ly most of AFBF’s 4.9 million members must

come from outside agriculture. Numbers from

the Texas Farm Bureau tell the story. In 1997,

Harris County, which includes metropolitan

Houston, had 4,675 members even though the

Department of Agriculture listed only 551 full-

A M B E R W A V E S O F G A I N

5

A M B E R W A V E S O F G A I N

6

time farmers there. Dallas County, with just 229

farmers, listed 2,332 Texas Farm Bureau mem-

bers. Even in the unlikely event that every full-

time farmer in both of those counties belonged

to the Farm Bureau, around 90 percent of the

Dallas and Harris county Farm Bureau members

would have been non-farmers.

In fact, most urban members are nothing

more than customers of Farm Bureau-affiliated

insurance companies. The Farm Bureau requires

these customers to purchase memberships in

order to qualify for low-cost automobile, home,

health or life insurance. These members do not

necessarily support or even know about the Farm

Bureau political activities that membership fees

and insurance premiums are bankrolling.

Chicago banker Sallyann Garner, for example,

became a Farm Bureau member when she took

out an insurance policy in 1991. Garner says she

knew that a membership in the DuPage County,

Illinois, Farm Bureau came with her policy. She

cannot recall whether her insurance agent told

her that all county members automatically

become members of the national organization.

Garner learned in April, 1998, about AFBF’s

lawsuit to force removal of the Yellowstone

wolves. “Wolf recovery happens to be one of my

pet programs,” she says. “I was extremely upset. I

was appalled that I was forced to be a member of

the American Farm Bureau just because of my

insurance. I ought to be able to choose insurance

based on the cost and the value and not unwit-

tingly be part of a political action group that

advocates policies I personally object to.” A letter

to DuPage County Farm Bureau president

Michael Ashby brought a response saying that if

Garner objected to the policy on “Wildlife Pest

and Predator Control” she could vote with her

checkbook and find other insurance.

Farm Bureau officials at the state, county and

national levels alike generally seem reluctant to

give straight answers to questions about how

many actual farmers belong to the organization.

“We feel like we represent eight out of ten

American farmers,” says Dick Newpher, execu-

tive director of AFBF’s Washington, D.C., office.

But he admits he actually has no idea whether

that statement is true because, he says, AFBF

does not keep a central membership list that

identifies who is a farmer and who is not.

However, AFBF bylaws clearly spell out two cat-

egories of membership: full members actively

engaged in agriculture or retired from farming

and associate members, defined as anyone else

with an “interest” in agriculture. Newpher says

county and state farm bureaus keep those

records, but queries to several state farm bureaus

did not produce answers, either. Texas Farm

Bureau spokesman Gene Hall says Texas mem-

bership records make no distinction between

farmers and other members.

The heavy dependence on insurance cus-

tomers as the bulwark of the organization sug-

gests that AFBF might become increasingly

inclined to focus more on building its business

interests than on speaking for individual farmers.

This is supported in AFBF publications. For

example, in a recent on-line essay, New York

Farm Bureau executive Bill Stamp spelled out the

importance of adding as many insurance cus-

tomers as possible to the Farm Bureau’s member-

ship rolls: “This year, New Jersey Farm Bureau

A M B E R W A V E S O F G A I N

made a bold effort to increase membership with

the support of their farm family agents. The

membership increase was made largely with asso-

ciate members. New Jersey Farm Bureau provid-

ed a wonderful marketing brochure for the non-

farm consumer of insurance. This practical ini-

tiative creates a larger membership base . . . .

This boosts the financial foundation that Farm

Bureau needs to achieve success of their policy

efforts. This is a shining example of success!”

Despite paying dues, Farm Bureau associate

members aren’t allowed to vote at the organiza-

tion’s conventions and thus have no say in policy

matters.

Unlike the average farmer, AFBF has escaped

paying taxes on its hefty income from member-

ship dues because it is a nonprofit organization

(although some state affiliates are set up as for-

profit groups). However, after an Internal

Revenue Service (IRS) survey of associate mem-

bers found that only five percent joined AFBF

because of an interest in agriculture, IRS in 1993

ruled that dues from these non-farming associate

members — customers of Farm Bureau insur-

ance companies and other businesses — should

be taxed as business income. The IRS ruling

could have cost AFBF and state affiliates $62

million in annual taxes. By 1996, IRS was suing

farm bureaus in 11 states for back taxes.

A group of members of Congress led by

Representative David Camp (R-Michigan) came

to the Farm Bureau’s rescue. Legislation reversing

the IRS decision won congressional approval in

1996 as part of the tax-relief package under

House Speaker Newt Gingrich’s “Contract With

America.” Congressman Camp explained that he

wanted to shield the organization from “unwar-

ranted and potentially devastating audits.”

Senator Phil Gramm (R-Texas) argued during

floor debate that “the IRS is trying to force the

Farm Bureau to pay taxes they do not owe” and

said the IRS action was “indefensible in the

opinion of the vast majority of the American

people.” After all, Gramm insisted, “being part

of the Farm Bureau is being part of agriculture.”

(For a detailed discussion of the 1996 tax relief

package see Appendix 2, “Tax Treatment of

Unrelated Business Income for Agricultural and

Horticultural Organizations.”)

During 1995 and 1996, Farm Bureau-affiliat-

ed political action committees (PACs) contribu-

ted $109,824 to many of the 126 congressional

sponsors of the Tax Fairness for Agriculture Act,

including $16,480 to Camp. In 1996 the Texas

Farm Bureau PAC gave Senator Gramm $5,000.

This report will examine the Farm Bureau’s

multibillion-dollar financial empire and show

how AFBF’s pursuit of policies beneficial to its

wide-ranging business interests has undercut the

well-being of America’s family farmers as well as

the interests of consumers and efforts to protect

the environment.

7

A M B E R W A V E S O F G A I N

8

“Farm Bureau businesses sustain and pre-

serve the organization. In terms of money, poli-

cy and power, they dominate the organization.”

— Samuel R. Berger, Dollar Harvest.

I

n 1967, U.S. Representative Joseph Resnick

(D-New York) launched an inquiry into

AFBF’s already sizable commercial ventures. As

chairman of the House Subcommittee on Rural

Development, he wanted to investigate whether

profits from AFBF-controlled businesses were

being transferred to the tax-exempt organization.

But when he moved for hearings, his subcom-

mittee balked. Most of those committee mem-

bers belonged to AFBF and had benefited from

AFBF help in their campaigns. The subcommit-

tee refused to authorize the investigation.

Resnick conducted hearings anyway, gathering

enough information to fill in a rough outline of

the Farm Bureau’s inscrutable business domain.

Before he could complete the process, however,

he died, at the age of 45.

Samuel R. Be r g e r, who had served as a

Resnick aide, picked up the threads of the

i n vestigation and in 1971 produced the most

c o m p re h e n s i ve analysis of the AFBF empire

written to date. His book Dollar Ha rvest ( He a t h

Lexington Books) explains in detail how the

n o n p rofit farm bureaus benefit from re l a t i o n-

ships with their for-profit business part n e r s .

Be r g e r, now national security adviser to

President Clinton, described the Farm Bu re a u

insurance network as “one giant company”

clearly controlled by AFBF.

According to Berger, the relationship works

like this: The insurance companies give AFBF

organizations “sponsorship fees,” which amount

to percentages of insurance company earnings.

“Putting aside the fascinating tax consequences

of these transactions, other ticklish problems

arise,” Berger wrote. Part of the insurance cus-

tomer’s premium goes directly into the pocket of

the Farm Bureau without the customer’s knowl-

edge, he pointed out.

Especially interesting are cases where Fa r m

Bu reau and insurance company boards of dire c-

tors are exactly the same people. Be r g e r

described a 1947 Ohio Insurance De p a rt m e n t

C H A P T E R O N E

Emphasizing the Bottom Line

A M B E R W A V E S O F G A I N

9

i n vestigation into the relationship between the

Ohio Farm Bu reau and Nationwide In s u r a n c e .

The insurance examiners we re n’t too happy

with the concept of overlapping board s .

Quoting from the examiner’s re p o rt, Be r g e r

w rote that eve ry time the insurance company

b o a rd offered the Farm Bu reau fees, “the same

men rushed around to the other side of the

table to say ‘Ok a y, we accept those fees.’ T h e

examiners said they felt people should not

negotiate with themselves.”

Frequently, the insurance companies rent

their office space from state farm bureaus and

employ the farm bureaus’ in-house advertising,

public relations and communications divisions.

In many states, the nonprofit farm bureaus also

own all or most of the stock of the insurance

companies. And those stocks pay dividends to

the state organizations. The farm bureaus also

benefit from using insurance customers to inflate

their membership numbers, since everyone who

buys a policy must join the bureau. The insur-

ance companies also benefit from the alliances.

Farm bureau lobbyists use their considerable

political clout to lobby on bills affecting their

partners in the insurance business. For instance,

state farm bureaus have lobbied hard for limits

on medical malpractice damage awards. And

AFBF is pushing for privatization of Social

Security, which could bring a profit windfall to

insurance company and financial investment

firm ventures. Relating any of those issues to

agriculture is a far stretch, but they certainly

affect the Farm Bureau’s bottom line.

INSURANCE AT A PREMIUM

“The purpose of this program is to provide

the best insurance products to Farm Bureau

members at the lowest possible cost and provide

excellent policyholder service.”

— AFBF insurance brochure.

“Farm Bureau member Nathan Baxley has

cancer and his daughter has muscular dystro-

phy; the Farm Bureau insurance plan hit him

with a premium increase of $1,950 a month

or an option for drastically reduced coverage.”

— Arkansas Democrat-Gazette,

January 20, 1994.

State farm bureaus have always promoted

their insurance lines as an important service to

their members, and in many cases customers do

have trouble finding any other insurance for a

reasonable price. Farm bureau insurance rates

generally compare favorably with other carriers

and often are lower. Despite these advantages,

Farm Bureau insurance falls far short of provid-

ing the best service to its customers. For exam-

ple, state officials and consumer groups have

accused some farm bureau-affiliated companies

of insuring only those who pose the least risk

and therefore are least likely to file claims. As the

following examples illustrate, the Farm Bureau

has a long history of using exorbitantly high rates

to dissuade or exclude altogether those who need

insurance the most:

• In 1961, as the East Germans were build-

A M B E R W A V E S O F G A I N

10

WHILE FAMILY FARMS FLOUNDER, THE FARM BUREAU FLOURISHES

Family farmers are going broke, but the Farm Bureau and many of its state af filiates ar e

amassing wealth and spending it as the following list and examples illustrate:

10 WEALTHIEST STATE FARM BUREAUS (Based on 1996 tax revenues)

1. California Farm Federation................................................$37,596,117

2. Illinois Agricultural Association ......................................... 28,780,046

3. Ohio Farm Bureau Federation ........................................... 11,122,260

4. Michigan Farm Bureau ...................................................... 10,134,866

5. Georgia Farm Bureau Federation ..........................................8,356,010

6. Texas Farm Bureau ............................................................... 8,244,374

7. Tennessee Farm Bureau Federation ..................................... 8,107,782

8. North Carolina Farm Bureau Federation, Inc. ..................... 8,075,741

9. Iowa Farm Bureau Federation .............................................. 7,479,588

10. Kentucky Farm Bureau Federation ...................................... 7,020,080

• Forty-one farm bureau affiliates had enough surplus funds to open their own

bank in 1999 with assets of approximately $135 million.

• Southern Farm Bureau Insurance sponsors the Southern Farm Bureau Classic,

an annual stop on the Professional Golfers Association Tour.

• In 1985, the height of the farm crisis in America, the Farm Bureau held a

million-dollar annual convention in Hawaii.

• FBL Financial Group, Inc., a publicly held company with special marketing

arrangements to sell farm bureau insurance in 15 states, did so well in 1999 it

had to readjust its operating income four times.

A M B E R W A V E S O F G A I N

ing the Berlin wall at the height of the cold war,

24-year-old Iowa corn farmer Larry Moore

decided to answer President John F. Kennedy’s

call to service by joining the Army. Moore had

been a farmer all his life and a loyal Farm Bureau

member. But as the young man prepared for his

tour of duty he got a notice from his Farm

Bureau insurance agent that the company would

double his auto insurance premium. “That’s just

not the kind of thing you’d do to show support

for America’s troops,” says Moore’s wife, Mary

Ellen. Moore immediately quit the Farm Bureau

and has refused to rejoin. Mary Ellen is still a

member, although she does not want to be. She

owns a separate farm across the border in Illinois

and says she has no choice but to deal with farm

bureau cooperatives, which offer the only market

for her grain. “They’ve got you in a noose, so

what are you going to do?” she asks. “I sure don’t

agree with their policies.”

• In the 1960s, after a series of rate hearings,

South Carolina Chief Insurance Commissioner

Charles Gambrell accused Southern Farm Bureau

Casualty Insurance Company of attempting to

persuade other insurance carriers “to lead the way

in raising farmers’ rates, so that Farm Bureau

could follow suit and avoid the stigma of being

the first to do so.”

• In 1994, Nathan Baxley was one of 1,400

ailing Farm Bureau members in Arkansas who

got rate-hike notices from Arkansas Farm Bureau

Insurance, which gave them less than 30 days to

find other insurance or pay the company thou-

sands of dollars extra in annual premiums.

According to Arkansas newspaper accounts, state

legislators accused the company of manipulating

the rate increases to purge sick members from

the rolls. “These members have been paying 20

and 25 years and didn’t need you until two or

three years ago,” Arkansas state representative

Lloyd George said at a hearing. George suggested

that the company had lowered rates for other

health insurance customers in order to attract

more new members. Baxley’s brother-in-law

added, “The Farm Bureau will attract you with

the new low premiums, then cut you out the

moment you get sick.”

• In Texas in 1994, regulators ordered

Southern Farm Bureau Life Insurance Company

to pay a $250,000 fine for overcharging

Medicare patients for prescription drug insur-

ance. The Texas insurance department said

Southern Farm had charged elderly patients

deductibles as high as $3,000 on prescription

drug claims after advertising that the policies

would cover 100 percent of prescription drugs

with no deductibles.

In addition, lawsuits have been filed and reg-

ulators in several states have fined Farm Bureau-

affiliated insurance companies for engaging in

redlining, the practice of refusing insurance to

people because of age or race or because they live

in low-income or minority neighborhoods. Red-

lining can mean that insurers refuse to write

policies in certain neighborhoods — they literal-

ly draw red lines on maps to mark off excluded

areas. But more often, redlining takes subtler

forms. In many cases, regulators have found that

insurance companies discourage minorities from

buying policies by quoting substantially higher

rates than the companies offer to people who live

in similar but largely white neighborhoods.

11

A M B E R W A V E S O F G A I N

12

In 1994, the Missouri insurance department

brought formal administrative charges against

Farm Bureau and Country Insurance Companies

for redlining the entire city of St. Louis.

Examiners found a map in a Farm Bureau under-

writing manual with the whole predominantly

minority city outlined in yellow and labeled

“ineligible property.” At the time, the Farm

Bureau was the ninth largest homeowners’ insur-

er in the state. A spokesman for the company

claimed that urban residents were excluded

because the Farm Bureau is “traditionally a rural

insurer” and confines business to counties with

local farm bureaus.

Nationwide Insurance has been particularly

troubled by redlining lawsuits filed by fair-hous-

ing groups around the country. While the Ohio

Farm Bureau no longer owns Nationwide, it still

exerts considerable influence over the insurance

company through its role in hand-picking board

members for Nationwide. The company and the

Farm Bureau continue to share office space in

Columbus. The insurance company pays the

Ohio Farm Bureau a generous fee on each policy

sold through the bureau. The farm bureaus in

California, Maryland and Pennsylvania have sim-

ilar agreements with Nationwide.

More examples:

• In 1997, Nationwide Insurance agreed to

pay Toledo residents $3.5 million to settle a civil

rights lawsuit over redlining, although the com-

pany did not admit doing anything wrong. In

that same year, Nationwide without admitting

guilt settled a Justice Department redlining law-

suit by agreeing to spend more than “$26 mil-

lion in minority neighborhoods nationally.”

• One of Nationwide’s own agents accused

the company in 1997 of refusing to let him sell

insurance in minority neighborhoods of

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Now, more than 20

Nationwide agents in other states have come for-

ward with allegations that the company pro-

motes redlining.

• In February, 1998, Nationwide settled a

racial discrimination lawsuit brought by the

Cincinnati NAACP. The suit accused the insur-

ance company of charging higher premiums in

neighborhoods with high concentrations of non-

white homeowners. Later that year, the Texas

Department of Insurance found that

Nationwide’s tightly controlled marketing strate-

gy, which is overseen from its home office in

Columbus, Ohio, “systematically exclude[s]

minority customers from the market in which

[they] operate. Such a pattern of operations

shows that Nationwide has engaged in a practice

of unfair discrimination.”

• In October, 1998, a Richmond, Virginia,

court ordered Nationwide to pay $100 million in

punitive damages and $500,000 in compensato-

ry damages for redlining. The verdict followed a

jury trial in which fair-housing advocates pre-

sented evidence that Nationwide had denied

home insurance to black applicants and had

imposed higher rates in Richmond, a predomi-

nantly black city, than in Richmond’s largely

white suburbs. The $100 million judgment was

the largest ever imposed in a redlining case —

and a judge who reviewed the jury’s decision

ruled in December, 1998, that the award was not

excessive. Nationwide denied wrongdoing. In

December, 1999, the case was still on appeal.

A M B E R W A V E S O F G A I N

13

CORPORATIONS OVER FAMILIES

“The purpose of Farm Bureau is to make

the business of farming more profitable, and

the community a better place to live.... Farm

Bureau is the voice of farmers and ranchers in

local meetings, at state legislatures and in the

nation’s capital.”

— This Is Farm Bureau, AFBF website.

“They had 70 or 80 years to speak out on

behalf of the small farmer and if they had done

their job, we wouldn’t be in the mess we’re in

now, where we’re losing farmers in astronomi-

cal numbers.”

— Martha Stevens, Missouri farmer.

Two Missouri controversies illustrate how out

of step the Farm Bureau can be with the family

farmers it purports to represent. Both cases

involve the efforts of small farmers and rural

communities to protect their environment and

quality of life, and in both cases the Farm Bureau

has come down squarely on the side of polluters.

The first example involves efforts to protect the

imperiled Topeka shiner, a tiny minnow that can

live only in cool, clear-running streams and can-

not tolerate pollution. At a 1998 U.S. Fish and

Wildlife Service hearing in Bethany, Missouri,

Farm Bureau lobbyist Dan Cassidy testified

against a proposal to add the shiner to the federal

endangered species list. Listing the minnow

could require farmers to take special care to keep

sediments, pesticides, manure and other pollu-

tants out of the water.

The Farm Bureau had alerted its members,

and dozens of farmers showed up at the hearing.

“Cassidy had this big old Cheshire-cat grin on

his face when he saw all of these farmers come

filing into the room,” recalls one farmer who

attended. Cassidy testified first, arguing that the

listing would lead to onerous and burdensome

regulations that could put family farmers out of

business. But then farmer after farmer got up to

say that the Farm Bureau did not speak for the

farmer. According to a head count taken by the

Sierra Club, 69 of the 87 farmers and rural resi-

dents at the meeting disagreed with Cassidy and

supported listing the shiner.

Martha Stevens, who has farmed for 45 years

and is nearing retirement, says she is proud that

Topeka shiners still survive in northern Missouri

streams. “It means we’ve been doing something

right,” she says. “If the water kills the fish, it

can’t be good for us. The Topeka shiner is a darn

good indication of when your water is polluted,

and I believe we ought to be able to coexist and

not pollute to the point that it destroys them

and eventually destroys us.” Stevens says the

degree of support for listing the Topeka shiner

appeared to take the Farm Bureau men by sur-

prise, but if they had been paying attention to

the concerns of small farmers, she says, the

bureau would have realized that family farmers

see pollution from big agribusiness as a far

greater threat than government regulation.

The second example underscores Stevens’s

point. For several years now, small farmers and

other rural residents in a three-county area of

northern Missouri have been locked in what is so

far a losing battle over pollution from confined

animal-feeding operations (CAFOs). These

A M B E R W A V E S O F G A I N

14

megahog farms house as many as 140,000 ani-

mals at one time. Rolf Cristen’s 600-acre farm is

sandwiched between two of these operations. “It

stinks at our house continuously,” he says. People

who have worked around livestock all their lives

say they sometimes wake up in the middle of the

night and vomit because the stench is so bad.

In 1982, Missouri’s legislature enacted a

“right-to-farm” law whose provisions made it dif-

ficult for the Missouri Air Conservation

Commission (MACC) to act against sources of

agricultural odors. Subsequently the commission

exempted farms from laws that require other

businesses to keep smells under control. The

intent was to protect farmers when city people

move out to the country and then object to nor-

mal farm smells. The exemption never contem-

plated, however, the intense, all-pervasive stench

that comes from hundreds of thousands of hogs

all housed together. In 1998, Missouri Attorney

General Jay Nixon petitioned MACC to revoke

the odor exemption for the state’s 20 largest live-

stock producers. Although there was no inten-

tion of dropping the exemption for family farm-

ers, the Missouri Farm Bureau attacked the pro-

posal, arguing that the odor regulations were not

based on sound science and would trample pri-

vate property rights. In 1999, MACC approved

the change, however.

Farm Bureau spokesman Estil Fretwell says

the bureau worried that if regulations were

imposed on the biggest farmers, they would soon

trickle down to family farms. “I think we’ve been

very clearly on the side of concerns of the aver-

age farmer in the state,” he says. But AFBF’s

position on private property rights, one of the

group’s national priorities, suggests otherwise.

The Farm Bureau wants the federal government

to compensate farmers or others who lose money

or have to spend it in order to comply with envi-

ronmental regulations. “When society makes

such demands, it is only fair that society share in

the cost,” reads an AFBF release. At first blush,

that policy may sound like something farmers

might see in their interest to support. But that is

not how the issue played out in northern

Missouri, where an agribusiness giant with ties to

the Farm Bureau used a property rights lawsuit

to force a small rural community into accepting

a corporate hog farm that has essentially

destroyed the town’s quality of life.

In January, 1994, when residents of Lincoln

Township got wind that Premium Standard

Farms (PSF) wanted to build an 80,000-hog

farm on the outskirts of their community, they

organized a petition drive to let the company

know that the town did not want the megahog

farm built there. That was before PSF had pur-

chased any land in the area. When the petitions

did not work, community leaders tried to keep

the corporate farm away by adopting new zoning

rules. As a result, Premium Standard sued

Lincoln Township for $7.9 million, alleging vio-

lations of its corporate property rights.

With only 146 registered voters, Lincoln

Township could hardly afford to defend itself

against PSF’s claim. PSF is the fifth-largest hog

producer in the nation, right behind Cargill and

Tyson Foods. This battle was truly a David-and-

Goliath conflict, except that in this round,

Goliath won. After a three-year legal battle, the

Missouri Supreme Court ruled in 1997 that

A M B E R W A V E S O F G A I N

15

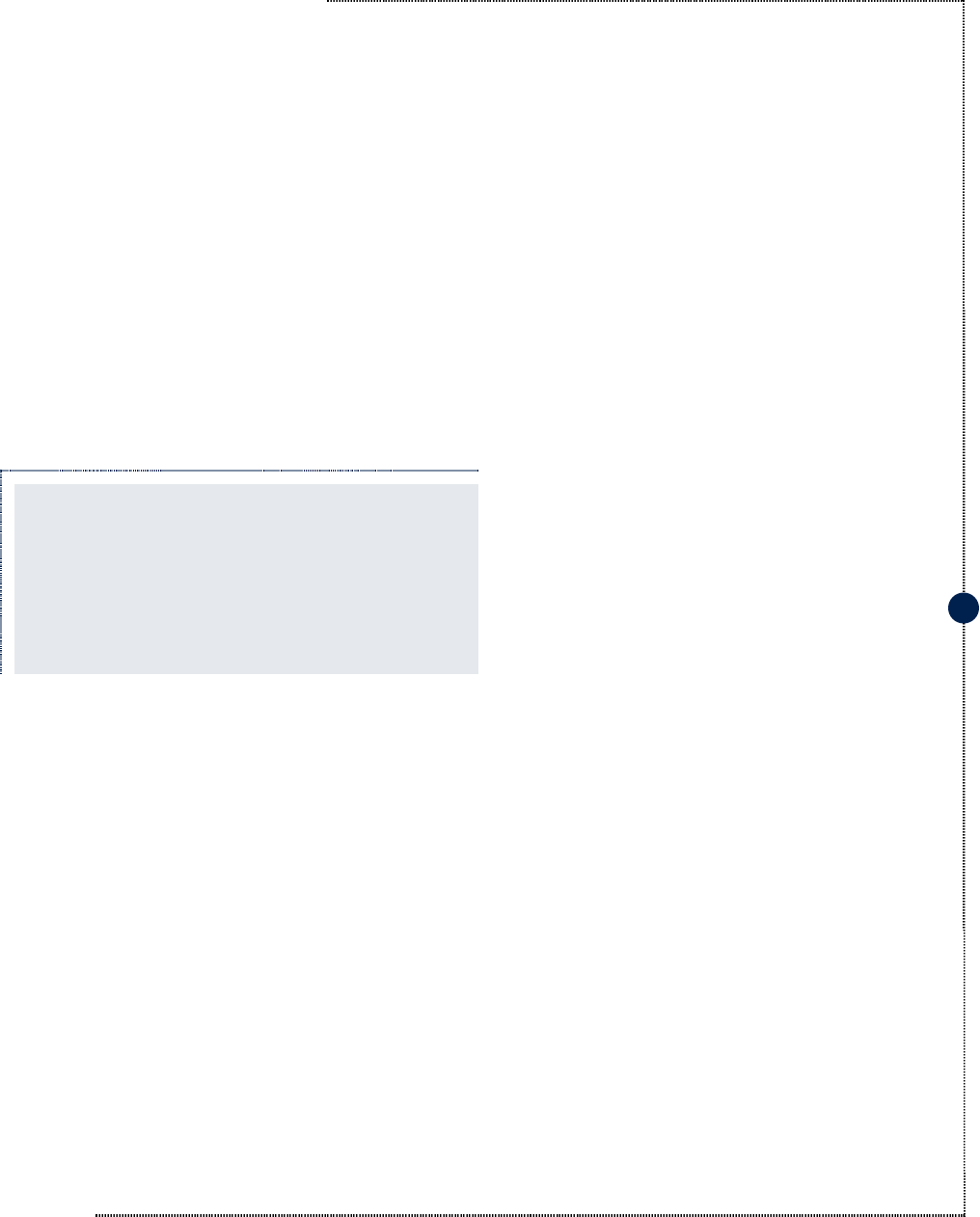

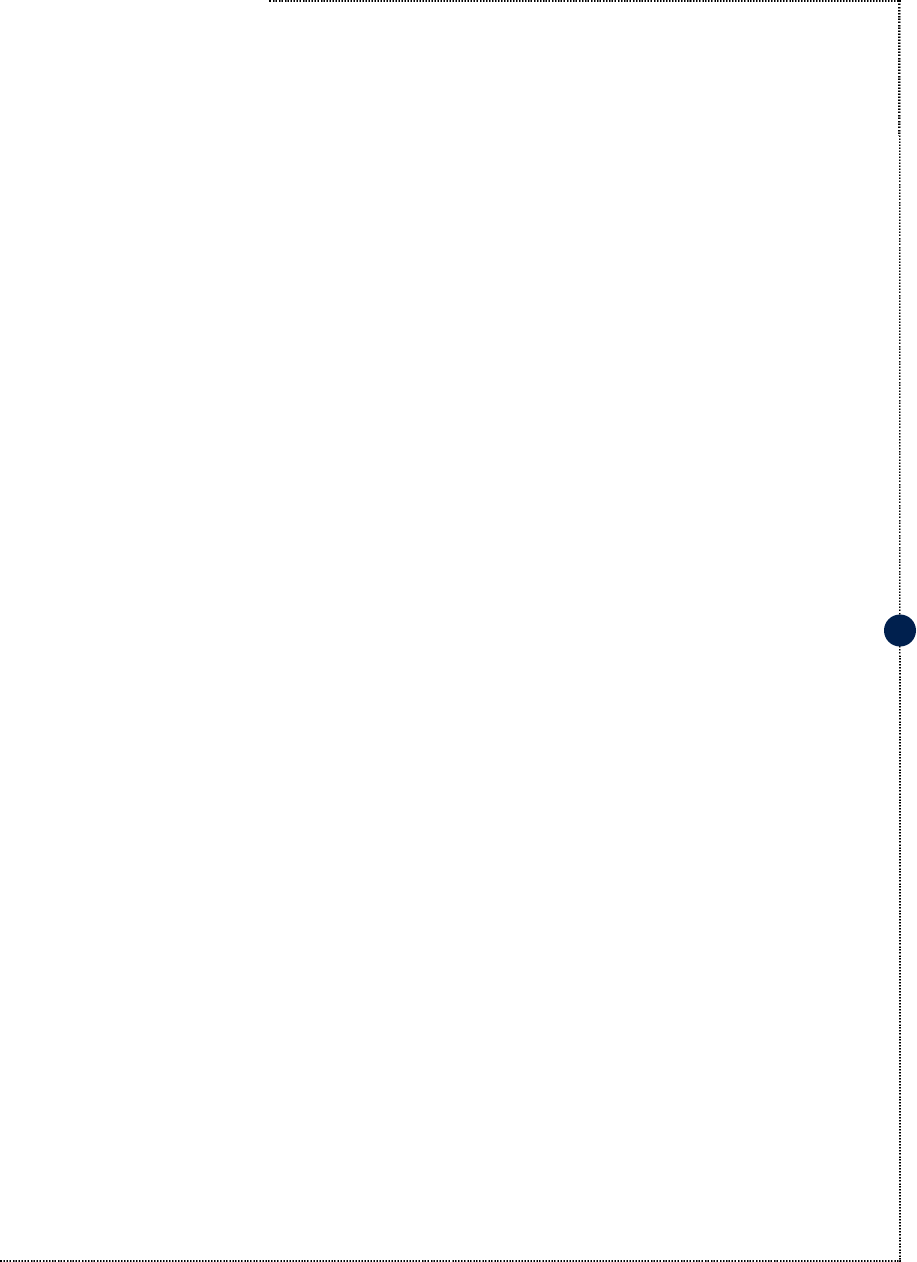

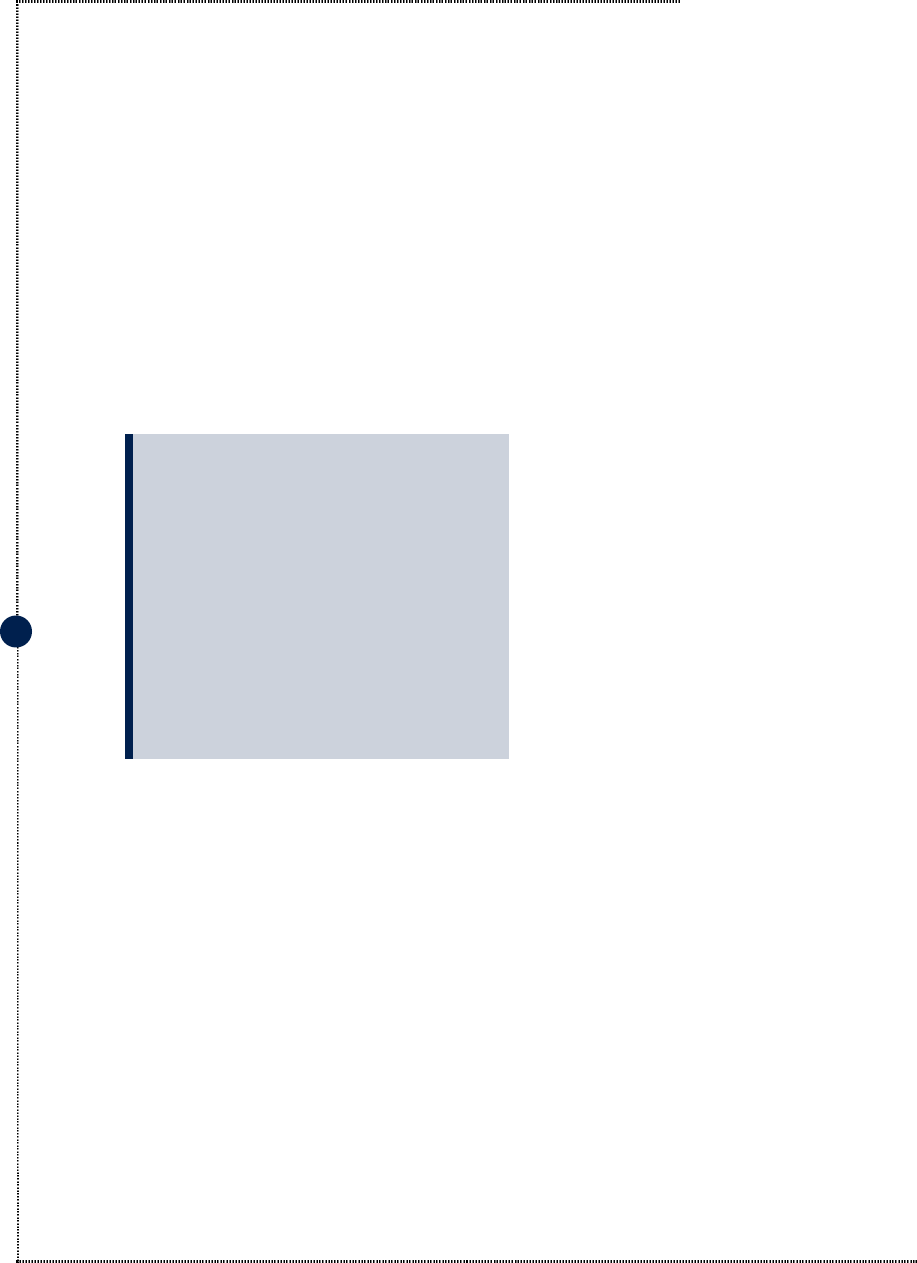

WHA T FARMERS THINK

About the U.S. Farm Economy

Asked to rate the overall farm economy in the United States today,

most farmers (88 percent) rate it negatively (54 percent say it is

“poor,” 34 percent say it is “not so good”). The overwhelmingly nega-

tive view of their own economic condition puts farmers in direct con-

trast to Americans as a whole. National polls show more than 60 per-

cent of Americans are positive about the U.S. economy.

About the Farm Bureau as an Advocate for Family Farmers

Fewer than one in three farmers (28 percent or 45 percent of Farm

Bureau members) mention the Farm Bureau when asked to volunteer

the organization or individual that most strongly advocates for the

interests of the American family farm today. Nearly half (48 percent)

say they don’t know or give no response, while one in four (24 per-

cent) mention groups or individuals such as the Department of

Agriculture or Secretary of Agriculture, Congress or a specific member,

the Farmer’s Union or government.

About the Farm Bureau in General

Farmers are three times as likely to have a positive

(49 percent) as a negative (16 percent) opinion of the

Farm Bureau (19 percent have a “very” positive opin-

ion). One in four (25 percent) have a neutral opinion.

Farm Bureau members are particularly likely to

have a positive opinion (71 percent), while nonmem-

bers are evenly divided (29 percent positive, 30 per-

cent neutral, 23 percent negative).

Those farmers negative toward the Farm Bureau

perceive it to be unresponsive to the needs of family

farmers or simply more interested in Farm Bureau

business ventures than in farm advocacy.

Farm Bureau Member? Size of Farm (acres)

O P I N I O N O N F A R M B U R E A U

Total Yes No

<

500 1,000 1,000+

% % % % % %

Positive 49 71 29 50 47 47

Neutral 25 20 30 25 21 30

Negative 16 7 23 14 21 16

Net Positive +33 +64 +6 +36 +26 +31

Don’t Know/

No Response

(48%)

Farm

Bureau

(28%)

Other*

(24%)

* Mentions: Department/Secretary of Agriculture, Congress/specific member,

Farmers Union, government, specific state organization

What one organization or individual do you think

most strongly advocates for the interests of the

American family farm today?

Source: Telephone poll of 500 randomly selected U.S. family farmers conducted by Frederick Schneiders Research

for Defenders of Wildlife in December, 1998.

Rating U.S. Farm Economy

Positive

Negative

A M B E R W A V E S O F G A I N

16

townships have no authority to impose any kind

of zoning regulations on farm buildings. The

court rejected Lincoln Township’s argument that

the planned PSF operation was a massive meat-

production factory, not a farm. The ruling left

the town with no options, so the hogs moved in.

The community had good reason to fear

what PSF’s hogs might do to its environment. In

fact, PSF’s record of contamination problems has

been so abominable that the U.S. Environmental

Protection Agency (EPA) singled out PSF as the

bad example to illustrate the need for stricter reg-

ulations on CAFOs. In congressional hearings in

April, 1998, EPA assistant administrator Robert

Perciasepe described a nightmare of manure

spills, sewage leaks, fish kills and continued

improper handling of waste. To begin with, he

told the Senate Committee on Agriculture,

Nutrition and Forestry, PSF’s hogs generate more

waste every day than many entire cities.

Perciasepe’s testimony is worth quoting at some

length:

“PSF operates 15 hog farms in Mercer,

Putnam and Sullivan counties in northern

Missouri. The Whitetail Hog Farm alone raises

1.6 million hogs each year, approximately two

percent of the national total. The 15 operations

generate 31 times more wastewater each year

than a city the size of Columbia, Missouri.

“From August through December in 1995,

seven separate incidents at Premium Standard

Farms in northern Missouri released hog urine

and manure into northern Missouri waters. Six

of the releases totaled more than 55,000 gallons.

The Department of Natural Resources reported

that more than 178,000 fish in Spring Creek,

Mussel Fork Creek and Blackbird Creek were

killed, and the Department of Conservation

indicated that the spills killed all aquatic life

along miles of Missouri’s waterways.

“On December 26, 1995, at the Whitetail

Hog Farm, a crack in a pipe designed to carry

waste from a hog-raising building to a sewage

lagoon released more than 35,000 gallons of

wastewater. The wastewater flowed into nearby

Blackbird Creek, killing fish and flowing into

neighboring farmland.

“ I n addition to these waste containment

p r oblems, in Ja n u a ry, 1996, state inspectors

re p o rted a widespread pattern of improper animal

waste disposal at Premium St a n d a rd Fa r m s .

Mi s s o u r i’s De p a rtment of Natural Re s o u r ces cited

Premium St a n d a rd for failing to comply with per-

mit re q u i r ements for land application of waste-

water at all of its 15 farms. State inspectors deter-

mined that Premium St a n d a rd’s wastewater flow

was about 10 million gallons more than the

a p p roved maximum flow of 84 million gallons.

In addition, the De p a rtment of Na t u r a l

Re s o u rces found that one of the August, 1995,

fish kills had been caused by improper land appli-

cation at Premium St a n d a rd’s Green Hills Farm.”

After more spills we re re p o rted in 1997, the

Missouri attorney general’s office and a gro u p

called Citize n s’ Legal En v i r onmental Ac t i o n

Ne t w o rk (CLEAN) filed legal actions claiming

that PSF violated clean air and water laws. T h e

attorney general also sued a PSF meatpacking

plant for discharging raw sewage. In Ma y, 1999, a

j u ry agreed with CLEAN that the hog farms are a

nuisance and ord e red PSF (now owned by Con-

tinental Grain Co.) to pay $100,000 each to the

A M B E R W A V E S O F G A I N

17

52 families living nearest the farms. T h ree months

l a t e r, PSF agreed to spend $25 million on tre a t i n g

hog waste before spreading it on land. The tre a t-

ment will be overseen by a court-appointed panel,

and Scott Holste of the Missouri attorney general’s

o f fice says PSF is being pressed to use “next gener-

a t i o n” technology. “We’re ve ry proud of what we

won in this case,” he says.

Scott Dye, CLEAN’s leader, says his small

group has never gotten any help from the Farm

Bureau in its fight with the corporate farms.

According to Dye, the Farm Bureau has consis-

tently sided with PSF on the contamination

problems. Not that he expected anything differ-

ent. Dye’s own family has farmed in Missouri for

118 years, but Dye says he has never belonged to

the Farm Bureau and will never join because he

believes the organization does not truly represent

family farms. “They’ve sold me up the river as far

as I’m concerned,” he says.

In 1993, the Missouri Farm Bureau lobbied

in favor of the legislation that allowed the corpo-

rate farms to move into the state in the first

place. When the legislature revisited the issue in

1998, the Farm Bureau once again used its clout

to help push through an extension of the 1993

law so the megahog farms could not only contin-

ue to operate but could expand.

The Missouri Farm Bureau has continued to

fight stricter odor regulations and any other new

rules that might force the big hog operations to

become better neighbors.

The Farm Bureau’s support of property-rights

claims especially rankles Missouri farmers.

“Property rights stop at your fence line,” Dye

says. “Just because you call yourself a farmer

doesn’t give you any right to fog out your neigh-

bor with the stink of hog manure and doesn’t

give you any right to pollute the water. Believe

me, you get a snout full of 80,000 hogs and it

will clarify your thought processes real quick.”

If the Farm Bu reau succeeds in persuading

C o n g ress and state legislatures to approve eve n

s t ronger pro p e rty-rights laws, enviro n m e n t a l i s t s

warn that few communities will be safe from the

kind of damage PSF has inflicted on Lincoln

Tow n s h i p . “The hog issue is a perfect example of

h o w this ideology can cause obvious and dire c t

damage to rural residents, including Farm Bu re a u

members,” says Ken Cook of the En v i ro n m e n t a l

Wo rking Gro u p, a re s e a rch and advocacy organi-

zation based in Washington, D.C. “Does the

Farm Bu reau seriously mean that communities

should pay corporations when towns adopt re g u -

lations to protect themselves?” he asks.

Former AFBF president Dean Kleckner ow n s

a hog farm himself. At the national level AFBF

has fought EPA’s initiative to tighten Clean Wa t e r

Act regulations on large animal-feeding opera-

tions. Although AFBF says it is trying to pro t e c t

small farmers from burdensome regulations, Dye

says his experience suggests that farmers have

nothing to fear. “T h e re’s never been a farmer put

out of business by environmental laws,” he

T h e re ’s never been a farmer put out of business by

e n v i ronmental laws. They’re put out of business by

f a c t o ry farms that skew markets and deflate prices.

A M B E R W A V E S O F G A I N

18

d e c l a r es. “T h e y’re put out of business by factory

farms that skew markets and deflate prices. We’ve

lost 5,000 independent swine producers in

Missouri in the last five years — family farms —

and they’re gone fore ve r. The Farm Bu reau has

stood on the sidelines and let that happen.”

Dye’s friend Rolf Cristen, active in the

Sullivan County Farm Bureau for more than a

decade, says he firmly believes in the bureau’s

mission and in working to influence its policies

from the inside. The Farm Bureau has so much

clout in Missouri, he says, that it is important to

have it on your side. On the hog issue, however,

Cristen has been getting more help lately from

the Sierra Club. “If you would have told me six

years ago that I would have a meeting with Sierra

Club, I would have told you you are totally off

your rocker,” he says. The Sierra Club’s Missouri

program director, Ken Midkiff, adds, “I would

suspect this is causing some concern for the

Farm Bureau. When family farmers start aligning

with the Sierra Club, that should be sending up

some kind of signal.”

Scott Dye sent a very strong signal by going

to work for the Sierra Club. Instead of looking

to the Farm Bureau for help on contamination

problems, he used the Sierra Club as a base to

begin his own investigation of PSF. In the

process, he learned that Southern Farm Bureau

Annuity Insurance Co. owns 18,872 shares of

PSF. The farm bureau federations in Alabama,

Arkansas, Kentucky, Mississippi and Texas set up

this insurance company, which now offers insur-

ance in 11 states. According to financial records,

the PSF stock is just part of more than $5 billion

in assets that Southern Farm Bureau Insurance

owns. The Farm Bureau tie to PSF that Dye dis-

covered is not an isolated case. Through its

insurance companies and an extensive network of

agricultural co-ops, AFBF’s financial interests are

intertwined with the biggest of agribusinesses.

In this case, the connections extend all the

way to Cargill, a mammoth corporation with

annual revenue of more than $50 billion. In

January, 1998, Continental Grain, an interna-

tional agribusiness and financial services compa-

ny based in New York, took control of PSF. The

following November Cargill announced plans to

buy Continental Grain. Cargill completed a

scaled-back purchase of Continental’s grain busi-

ness in July, 1999, with approval from federal

regulators even though the Department of Justice

had charged that the merger would “substantially

lessen competition for purchases of corn, soy-

beans and wheat . . . enabling it unilaterally to

depress the prices paid to farmers.” How the deal

will affect Southern Farm Bureau Annuity

Insurance’s 18,872 shares of PSF stock remains

to be seen. As this report will explore, these rela-

tionships create incentives for the “nonprofit”

farm bureaus to lobby for policies that benefit

corporations at the expense of family farms.

A M B E R W A V E S O F G A I N

19

“I don’t know these people who are saying

Farm Bureau is anti-small farmer or anti-fam-

ily farmer, or that Farm Bureau is only for the

big guys. I don’t know what they’re talking

about.”

— Dean Kleckner, AFBF president,

1986-2000.

“The Farm Bureau basically represents a

very small minority of their membership and

then claims to be a friend of the farmers. All

we want is on any given day to be able to step

outside our door and take a deep breath

regardless of which direction the wind is blow-

ing.”

— Donna Buss, Illinois Farm Bureau

member.

D

onna Buss lives just down the road from the

Durkee Swine Farm, a confined animal-feed-

ing operation with a record of pollution

problems so serious that Illinois’s attorney gener-

al at the request of the Illinois Environmental

Protection Agency last year sued the owner for

water quality and odor violations. A state inspec-

tor had found concentrated runoff from a waste

lagoon flowing directly into a creek where fish

kills had been reported.

Buss and her husband have lived in this

Henderson County farming community for

more than 20 years. “We’d never had problems

with any of our neighbors’ farming practices

before,” she says, until the hog operation started

up in 1995. “The stench from this place is unbe-

lievable,” she says. “You’d think the Farm Bureau

would be a little concerned about maintaining

the quality of rural life.” But the Illinois Farm

Bureau gave exactly the opposite response. In

March, 1998, its board voted to offer Durkee

Swine Farm legal assistance. And when Buss and

other neighbors, including several Farm Bureau

members, filed complaints and wrote letters to

local newspapers, she claims a delegation from

the county farm bureau paid them a visit to pres-

sure them to back off. “I don’t know if this was

scare tactics or what,” Buss says.

If Buss is angry about the Farm Bureau’s fail-

ure to take a stand against agricultural polluters,

C H A P T E R T W O

Plumping for Factory Hog Farms

A M B E R W A V E S O F G A I N

20

she is not alone. With the exponential growth of

huge hog farms in recent years, rural residents in

h u n d r eds of communities across the nation have

watched their quality of life deteriorate. Yet in

nearly eve ry state that has tried to curb the size of

these mostly corporate farms or to control the pol-

lution from them, the Farm Bu reau has active l y

w o rked to defeat new laws or re g u l a t i o n s .

Farm Bureau leaders insist they do not side

with the interests of corporate agribusiness over

family farmers. “We’re taking the side of growth

in the livestock industry,” says Illinois Farm

Bureau communications director Dennis Vercler.

“We have to have a good political climate, a

favorable public climate, a positive regulatory cli-

mate to allow this industry to grow. We’ve said

we need to concentrate on making sure we have

the ability to expand the size of the industry

regardless of the size of individual operations.”

That policy may not deliberately oppose the

interests of small farmers, but one result has been

a precipitous decline in the number of family

hog farms and an unprecedented concentration

of hog production in facilities controlled by a

handful of huge corporations. Some of those

megahog farms are run by agricultural coopera-

tives with direct ties to state farm bureaus.

PIG POLLUTION

Traditionally, the techniques used by small

hog farmers for manure disposal are simple and

sustainable. These farmers usually grow crops in

addition to raising livestock, and manure from

several hundred hogs can be plowed into the soil

for fertilizer as needed. That option does not

apply, however, when animal-feeding operations

involve tens of thousands of hogs in one con-

fined location. Hog waste from these huge facili-

ties is piped into enormous lagoons that too

often leak and nearly always stink.

According to EPA, livestock operations are

now producing a staggering 1.4 billion tons of

manure annually. Leaking lagoons can contami-

nate water supplies with nitrogen, phosphorus,

sediment, pathogens, heavy metals, hormones,

antibiotics and ammonia. And as production

becomes more concentrated, the pollution threat

escalates. Examples:

• In 1994, manure that spilled from a hog

operation in western Illinois killed 160,000 fish,

according to the U.S. EPA.

• In 1995, 22 million gallons of hog waste

burst through a lagoon dike at a North Carolina

confined animal-feeding operation and spilled

into the New River. The spill was twice the size

of the Exxon Valdez oil spill.

• In 1996, 40 manure spills — double the

number reported in 1992 — killed 670,000 fish

in Iowa, Minnesota and Missouri, according to a

report prepared for U.S. Senator Tom Harkin

(D-Iowa).

• In 1997, Illinois EPA inspectors found hog

waste in 68 percent of the streams they surveyed.

• On the east coast, where the microorgan-

ism Pfiesteria piscicida was blamed for killing

more than a billion fish and for sickening fisher-