Reference Manual for

Health Care Facilities with Limited Resources

Module 2. Hand Hygiene

Authors

Meredith A. Gerland, MPH, CIC

Bria S. Graham-Glover, MPH, CIC

Infection

Prevention

and Control.

The authors have made every effort to check the accuracy of all information, the dosages of any drugs, and

instructions for use of any devices or equipment. Because the science of infection prevention and control is rapidly

advancing and the knowledge base continues to expand, readers are advised to check current product information

provided by the manufacturer of:

• Each drug, to verify the recommended dose, method of administration, and precautions for use

• Each device, instrument, or piece of equipment to verify recommendations for use and/or operating

instructions

In addition, all forms, instructions, checklists, guidelines, and examples are intended as resources to be used and

adapted to meet national and local health care settings’ needs and requirements. Finally, neither the authors,

editors, nor the Jhpiego Corporation assume liability for any injury and/or damage to persons or property arising

from this publication.

Jhpiego is a nonprofit global leader in the creation and delivery of transformative health care solutions that save lives.

In partnership with national governments, health experts, and local communities, we build health providers’ skills,

and we develop systems that save lives now and guarantee healthier futures for women and their families. Our

aim is revolutionizing health care for the planet’s most disadvantaged people.

Jhpiego is a Johns Hopkins University affiliate.

Jhpiego Corporation

Brown’s Wharf

1615 Thames Street

Baltimore, MD 21231-3492, USA

www.jhpiego.org

© 2018 by Jhpiego Corporation. All rights reserved.

Editors: Melanie S. Curless, MPH, RN, CIC

Chandrakant S. Ruparelia, MD, MPH

Elizabeth Thompson, MHS

Polly A. Trexler, MS, CIC

Editorial assistance: Karen Kirk Design and layout: AJ Furay

Dana Lewison Young Kim

Joan Taylor Bekah Walsh

Module 2 Jhpiego technical reviewers: Chan Aung, Myanmar

Patricia Gomez, USA

Silvia Kelbert, USA

Infection Prevention and Control: Module 2 1

Module 2. Hand Hygiene

Chapter 1. Hand Hygiene .............................................................................................................................. 2

Key Topics ............................................................................................................................................... 2

Key Terms ............................................................................................................................................... 2

Background .................................................................................................................... ......................... 4

Hand Hygiene Opportunities .................................................................................................................. 4

Hand Hygiene Methods .......................................................................................................... ................ 5

Issues and Considerations Related to Hand Hygiene ........................................................................... 10

Monitoring Hand Hygiene .................................................................................................................... 12

Implementation of a Five-Step Hand Hygiene Improvement Strategy ................................................ 15

Summary............................................................................................................................................... 18

Appendix 1-A. Sample Hand Hygiene Observation Form: World Health Organization ....................... 19

Appendix 1-B. Sample Hand Hygiene Observation Form Modified for Room Entry and Exit .............. 22

Appendix 1-C. Implementation of a Multimodal Hand Hygiene Improvement Strategy ..................... 23

References ............................................................................................................................................ 27

Hand Hygiene

2 Infection Prevention and Control: Module 2, Chapter 1

Chapter 1. Hand Hygiene

Key Topics

Importance of hand hygiene

When to perform hand hygiene—the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) “5 Moments for Hand

Hygiene”

Proper technique for washing hands with soap and water

Proper technique for use of alcohol-based handrub

Issues and considerations related to hand hygiene

Monitoring hand hygiene

WHO’s strategy for improving hand hygiene programs

Key Terms

Alcohol-based handrub (ABHR) is a fast-acting, antiseptic handrub that does not require water to

reduce resident flora, kills transient flora on the hands, and has the potential to protect the skin

(depending on the ingredients).

Antiseptic agents or antimicrobial soap (terms used interchangeably) are chemicals applied to the

skin or other living tissue to inhibit or kill microorganisms (both transient and resident). These

agents, which include alcohol (ethyl or isopropyl), dilute iodine solutions, iodophors, chlorhexidine,

and triclosan, are used to reduce the total bacterial count.

Antiseptic handwashing is washing hands with soap and water or with products containing an

antiseptic agent.

Clean water is natural or chemically treated or filtered water that is safe to drink and use for other

purposes (e.g., handwashing and general medical use) because it meets national public health

standards and the WHO guidelines for drinking-water quality.

Emollient is an organic agent (e.g., glycerol, propylene glycol, or sorbitol) that is added to ABHR to soften

the skin and help prevent skin damage (e.g., cracking, drying, irritation, and dermatitis) that is often

caused by frequent hand hygiene.

Hand disinfection is a term that WHO does not recommend using because disinfection normally refers

to the decontamination of non-living surfaces and objects.

Hand hygiene is the process of removing soil, debris, and microbes by cleansing hands using soap and

water, ABHR, antiseptic agents, or antimicrobial soap.

Handwashing is the process of mechanically removing soil, debris, and transient flora from hands using

soap and clean water.

Health care-associated infection (HAI) is an infection that occurs in a patient as a result of care at a

health care facility and was not present at the time of arrival at the facility. To be considered an HAI,

the infection must begin on or after the third day of admission to the health care facility (the day of

admission is Day 1) or on the day of or the day after discharge from the facility. The term “health

care-associated infection” replaces the formerly used “nosocomial” or “hospital” infection because

evidence has shown that these infections can affect patients in any setting where they receive

health care.

Hand Hygiene

Infection Prevention and Control: Module 2, Chapter 1 3

Microorganisms are causative agents of infection, and include bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites.

Some bacteria can exist in a vegetative state (during which the organism is active and infective) and

as endospores (in which a tough, dormant, non-reproductive structure protects the cell).

Endospores are more difficult to kill due to their protective coating.

Persistent activity is prolonged or extended protective activity that prevents the growth or survival of

microorganisms after application of an antiseptic; it is also called “residual” activity.

Point of care is the place where three elements come together: the patient, the health care worker

(HCW), and the care or treatment involving contact with the patient or the surrounding environment. For

this chapter, the concept embraces the need to perform hand hygiene at recommended moments

exactly where care delivery takes place. This requires that a hand hygiene product (e.g., ABHR) be easily

accessible and as close as possible—within arm’s reach—to where patient care or treatment is provided.

Resident flora are microorganisms that live in the deeper layers of the skin and within hair follicles and

cannot be completely removed, even by vigorous washing and rinsing with plain soap and clean water. In

most cases, resident flora are not likely to be associated with infections; however, the hands or

fingernails of some HCWs can become colonized by microorganisms that do cause infection (e.g.,

Staphylococcus aureus, gram-negative bacilli, or yeast), which can be transmitted to patients.

Soap (term is used interchangeably with detergent) is a cleaning product (e.g., bar, liquid, leaflet, or

powder) that lowers surface tension of water, thereby helping to remove dirt and debris. Plain soaps do

not claim to be antimicrobial on their labels and require friction (i.e., scrubbing) to mechanically remove

microorganisms. Antiseptic (antimicrobial) soaps kill or inhibit growth of most microorganisms.

Standard Precautions are a set of infection control practices used for every patient encounter to

reduce the risk of transmission of bloodborne and other pathogens from both recognized and

unrecognized sources. They are the basic level of infection control practices to be used, at a

minimum, in preventing the spread of infectious agents to all individuals in the health care facility

(see Module 1, Chapter 2, Standard and Transmission-Based Precautions).

Surgical hand preparation refers to the protocol used preoperatively by surgical teams to eliminate

transient flora and reduce resident skin flora. The process involves an antiseptic handwash or

antiseptic handrub and rubbing/scrubbing for specific amounts of times using specific techniques

prior to donning gloves. Antiseptics used for surgical hand preparation often have persistent

antimicrobial activity (for details, see Module 7, Chapter 2, Use of Antiseptics in Health Care

Facilities):

Surgical handrub refers to surgical hand preparation with a waterless ABHR.

Surgical hand scrub refers to surgical hand preparation with antimicrobial soap and water.

Transient flora are microorganisms acquired through contact with individuals or contaminated

surfaces during the course of normal, daily activities. They live in the upper layers of the skin and are

more amenable to removal by hand hygiene. They are the microorganisms most likely to cause HAIs.

“The hands of healthcare workers are a major source of transmission of

nosocomial pathogens.”

–Bhalla et al. 2004

Hand Hygiene

4 Infection Prevention and Control: Module 2, Chapter 1

Background

Hand hygiene is the single most important measure to prevent transmission of infection and is the

cornerstone of infection prevention and control (IPC). The original study in this field was conducted at a

maternity hospital in Vienna, Austria, in 1847. This study demonstrated that the mortality rate among

mothers was significantly lower when the HCWs cleaned their hands with an antiseptic agent

(Semmelweiss 1861). Numerous other studies since then have demonstrated that HCWs’ hands become

contaminated during routine care of patients and can transmit infectious diseases from patient to patient

(AORN Recommended Practices Committee 2004; Duckro et al. 2005; Ojajarvi 1980; Pittet et al. 1999;

Riggs et al. 2007; Sanderson and Weissler 1992). Proper hand hygiene can prevent transmission of

microorganisms and decrease the frequency of HAIs. Despite evidence that hand hygiene prevents

transmission of infections, compliance with hand hygiene recommendations during patient care continues

to present ongoing challenges in all settings. Methods used to improve compliance with hand hygiene are

addressed later in this chapter.

The goal of hand hygiene is to remove soil, dirt, and debris and reduce both transient and resident flora.

Hand hygiene can be performed using ABHR or by washing hands with water and plain or antimicrobial

soap (bar or liquid) that contains an antiseptic agent such as chlorhexidine, iodophors, or triclosan. (WHO

2009a)

Traditionally, handwashing with soap and water has been the primary method of hand hygiene; however,

ABHR has been shown to be more effective for standard hand hygiene than plain or antimicrobial soaps.

(CDC 2002)

Recommendations for when and how to perform hand hygiene are described in this chapter. For

information and instructions about surgical hand scrub and surgical hand rub, see Module 7, Chapter 2,

Use of Antiseptics in Health Care Facilities.

“Failure to perform appropriate hand hygiene is considered to be the leading

cause of healthcare associated infections (HAIs) and the spread of multidrug

resistant microorganisms, and has been recognized as a significant contributor

to outbreaks.”

–Boyce et al. 2002

Hand Hygiene Opportunities

The World Health Organization has five recommended points in time when hand hygiene should occur in

order to prevent transmission of HAIs. These recommendations are called the “My 5 Moments for Hand

Hygiene” and focus on the following times:

1. Before making contact with a patient

2. Before performing a clean/aseptic task, including touching invasive devices

3. After performing a task involving the risk of exposure to a body fluid, including touching invasive

devices

4. After patient contact

5. After touching equipment in the patient’s surrounding areas (WHO 2006a)

Hand Hygiene

Infection Prevention and Control: Module 2, Chapter 1 5

The “5 Moments” are numbered according to health care workflow in an attempt to ease recall for HCWs

(see Figure 1-1).

Figure 1-1. WHO’s Five Recommended Moments for Hand Hygiene

Reprinted from: The “My 5 Moments for Hand Hygiene,” © World Health Organization (2009):

http://www.who.int/gpsc/5may/background/5moments/en/. Accessed June 28, 2016.

Hand Hygiene Methods

Handwashing with Soap and Water

The purpose of routine handwashing in health care is to remove dirt and organic material, as well

microbial contaminants, from the hands. Clean water must be used to prevent microorganisms in the

water from contaminating the hands. However, water alone is not effective at removing substances

containing fats and oils, which are often present on soiled hands. Proper handwashing also requires soap,

which is rubbed on all hand surfaces, followed by thorough rinsing and drying.

The cleansing activity of handwashing is achieved by both friction and the detergent properties of the

soap. Plain soap has minimal antimicrobial properties, but assists with the mechanical removal of debris

and loosely adherent microbes, while the mechanical action removes some bacteria from hands. Time is

also an important factor—handwashing for 30 seconds has been shown to remove 10 times the amount of

bacteria as handwashing for 15 seconds. The entire handwashing procedure, if completed properly, as

described step by step in Figure 1-2, should take 40–60 seconds. (CDC 2002; WHO 2009a)

Hand Hygiene

6 Infection Prevention and Control: Module 2, Chapter 1

Figure 1-2. The Steps for Routine Handwashing (How to Properly Wash Your Hands)

Reprinted from: “How to Handwash,” © World Health Organization (2009).

http://www.who.int/gpsc/5may/How_To_HandWash_Poster.pdf. Accessed May 6, 2016.

Handwashing with soap and water is recommended (rather than using ABHR) in the following situations:

If hands are visibly soiled or contaminated with blood or body fluids

After using the toilet

Before eating

To remove the buildup of emollients (e.g., glycerol) on hands after repeated use of ABHR

In outbreaks of C. difficile, but not in health care settings with only a few cases of C. difficile. (Cohen

et al. 2010; Siegel et al. 2007) C. difficile is a bacterial infection that causes severe diarrhea and is

common in some settings.

Avoiding contamination of hands during handwashing

Since microorganisms grow and multiply in moisture and in standing water, the following are

recommended to prevent contamination of hands during handwashing:

Hand Hygiene

Infection Prevention and Control: Module 2, Chapter 1 7

Avoid bar soaps when possible because they can become contaminated, leading to colonization of

microorganisms on hands. There is some evidence, however, that the actual hazard of transmitting

microorganisms through handwashing with previously used bar soaps is negligible. If bar soap is

used, provide small bars and use soap racks that drain the water after use. (WHO 2009a)

Do not add liquid soap to a partially empty liquid soap dispenser. This is known as “topping off.” The

practice of topping off dispensers may lead to bacterial contamination of the soap. Using refill

packets avoids this problem but if they are not available, dispensers should be thoroughly cleaned

and dried before refilling. (WHO 2009a)

Filter and/or treat water if a health care facility’s water is suspected of being contaminated; this will

make the water microbiologically safer. (WHO 2009a) (See Module 5, Chapter 3, Managing Food and

Water Services for the Prevention of Health Care-Associated Infections, and Module 10, Chapter 6,

Preventing Health Care-Associated Infectious Diarrhea.)

Use running water for hand hygiene. In settings where no running water is available, water

“flowing” from a pre-filled container with a tap is preferable to still-standing water in a basin. Use a

container with a tap that can be turned off preferably with the back of the elbow (when hands are

lathered) and turned on again with the back of the elbow for rinsing. As a last resort, use a bucket

with a lid or a pitcher and a mug to draw water from the bucket, with the help of an assistant, if

available. (WHO 2009a)

Avoid dipping hands into basins of standing water. Even with the addition of an antiseptic agent

(e.g., Dettol or Savlon), microorganisms can survive and multiply in these solutions. (Rutala 1996)

If a drain is not available where hands are washed, collect water used from hand hygiene in a basin

and discard it in a drain or in a latrine.

Dry hands properly because wet hands can more readily acquire and spread microorganisms. Dry

hands thoroughly with a method that does not recontaminate the hands. Paper towels or single-use

clean cloths/towels are an option. Make sure that towels are not used multiple times or by multiple

individuals because shared towels quickly become contaminated. (WHO 2009a)

Alcohol-Based Handrub (ABHR)

The antimicrobial activity of alcohol results from its ability to denature proteins (i.e., the ability to dissolve

some microbe components) and kill microbes. Alcohol solutions containing 60–80% alcohol are most

effective, with higher concentrations being less effective. This paradox results from the fact that proteins

are not denatured easily in the absence of water; as a result, microorganisms are not killed as easily with

higher alcohol-based solutions (> 80% alcohol). (WHO 2009a)

The use of an ABHR is more effective in killing transient and resident flora than handwashing with

antimicrobial agents or plain soap and water. It also has persistent (long-lasting) activity. ABHR is quick and

convenient to use and can easily be made available at the point of care. ABHR usually contains a small

amount of an emollient (e.g., glycerol, propylene glycol, or sorbitol) that protects and softens skin. ABHR

should be used at any of the “5 Moments” described earlier in this chapter, unless hands are visibly soiled.

(CDC 2002; Girou et al. 2002; WHO 2009a)

To be effective, approximately 3–5 mL (i.e., 1 teaspoon) of ABHR should be used. The ideal volume of

ABHR to apply to the hands varies according to different formulations of the product and hand size (refer

to manufacturer’s instructions for use). ABHR should be used, following the steps shown in Figure 1-3, for

approximately 20–30 seconds or until the solution has fully dried. Since ABHR does not remove soil or

organic matter, if hands are visibly soiled or contaminated with blood or body fluids, handwash with soap

Hand Hygiene

8 Infection Prevention and Control: Module 2, Chapter 1

and water. To reduce the buildup of emollients on hands after repeated use of ABHR, washing hands with

soap and water after every 5–10 applications of ABHR is recommended.

In C. difficile outbreak settings, handwashing with soap and water is recommended over ABHR as it is more

effective than ABHR in removing endospores. If there are only a few cases of C. difficile, normal use of

ABHR is recommended (Cohen et al. 2010; Siegel et al. 2007; WHO 2009a). The need for using soap and

water over ABHR during outbreaks of norovirus is an unresolved issue. (Siegel et al. 2007; WHO 2009a)

Figure 1-3. WHO Recommendation on How to Perform Hand Hygiene with ABHR

Reprinted from: “How to handrub,” © World Health Organization (2009).

http://www.who.int/gpsc/5may/How_To_HandRub_Poster.pdf. Accessed May 6, 2016.

Producing alcohol-based handrub

An effective ABHR solution is inexpensive and simple to make, even in limited-resource settings. WHO

provides procedures for making ABHR in health care facility pharmacies (see Figure 1-4).

Hand Hygiene

Infection Prevention and Control: Module 2, Chapter 1 9

Figure 1-4. Alcohol-Based Handrub Formulation

Formulation 1: To produce final concentrations of ethanol 80% v/v, glycerol 1.45% v/v, hydrogen

peroxide (H

2

O

2

) 0.125% v/v:

Pour into a 1,000-mL graduated flask:

1. Ethanol 96% v/v, 833.0 mL

2. H

2

O

2

3%, 41.7 mL

3. Glycerol 98%, 14.5 mL

Top up the flask to 1,000 mL with distilled water or water that has been boiled and cooled; shake the

flask gently to mix the contents.

Formulation 2: To produce final concentrations of isopropyl alcohol 75% v/v, glycerol 1.45 v/v,

hydrogen peroxide 0.125% v/v:

Pour into a 1,000-mL graduated flask:

1. Isopropyl alcohol (with a purity of 99.8%), 751.5 mL

2. H

2

O

2

3%, 41.7 mL

3. Glycerol 98%, 14.5 mL

Top up the flask to 1,000 mL with distilled water or water that has been boiled and cooled; shake the

flask gently to mix the contents.

v/v=volume percent, meaning 80 parts absolute alcohol in volume and 20 parts water measured as

volume, not as weight

Adapted from:

WHO Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Health Care: First Global Patient Safety Challenge. Clean Care Is

Safer Care, page 49. © World Health Organization (2009).

Do not add ABHR to a partially empty dispenser. This practice of “topping off” dispensers may lead to

bacterial contamination. The use of refill packets avoids this problem but if they are not available, the

dispensers should first be thoroughly cleaned and dried before refilling. (WHO 2009a)

Antiseptic Soaps

Antiseptic soaps may be used in place of plain soap during the “My 5 Moments for Hand Hygiene”

described above but are not recommended for most settings. Handwashing with antiseptic soap is more

irritating to the skin and more expensive than using ABHR. Therefore, if available, ABHR should be used

under normal circumstances. (WHO 2009a)

Use of antiseptic soaps is recommended for surgical hand scrub and before entry into special areas of

health care facilities (e.g., neonatal intensive care units).

Surgical Hand Scrub

The purpose of the surgical hand scrub is to mechanically remove soil, dirt, debris, and transient flora

microorganisms and to reduce resident flora before and for the duration of the surgery. The goal is to

prevent wound contamination by microorganisms from the hands and arms of the surgical team members

(see Module 7, Chapter 2, Use of Antiseptics in Health Care Facilities, for more details).

Hand Hygiene

10 Infection Prevention and Control: Module 2, Chapter 1

Issues and Considerations Related to Hand Hygiene

Glove Use

While the effectiveness of gloves in preventing contamination of HCWs’ hands has been confirmed, gloves

do not provide complete protection against hand contamination. Contamination may occur as a result of

small, undetected holes in gloves, as well as during glove removal. Thus, wearing gloves does not replace

the need for proper hand hygiene. Hand hygiene should always be performed before putting on and after

removing gloves (see Module 3, Chapter 1, Personal Protective Equipment, for details of correct glove

use). (CDC 2002; WHO 2002)

Wearing the same pair of gloves and cleaning gloved hands between patients or between dirty and clean

body sites is not a safe hand hygiene practice (Siegel et al. 2007; WHO 2009a; WHO 2009c; WHO 2009d).

Not changing gloves between patients has been associated with transmission of microorganisms such as

methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and gram-negative bacilli. Reprocessing gloves is not recommended.

Every effort must be made to reinforce the message that gloves do not replace the use of hand hygiene

and that when gloves are required, they should be used in addition to hand hygiene (see Module 3,

Chapter 1, Personal Protective Equipment, for more information on glove use).

Hand Lotions and Hand Creams

In an effort to minimize hand hygiene-related contact dermatitis (a skin rash caused by irritation from a

substance such as soap due to frequent hand hygiene), hand lotions, creams, barrier creams, and

moisturizing skin care products are recommended. Hand lotions and creams often contain humectants

(substances that help retain moisture) and various fats and oils. These humectants can increase hydration

and replace altered or depleted skin lipids that can serve as a barrier to microorganisms on normal skin.

Several studies have shown that regular use (i.e., at least twice per day) of such products can help prevent

and treat contact dermatitis. There is also biologic evidence that emollients (e.g., glycerol and sorbitol)

contained in ABHR, with or without antiseptics, may decrease cross-contamination because they reduce

shedding of bacteria from skin for up to 4 hours. These products are absorbed into the superficial layers of

the epidermis and are designed to form a protective layer that is not removed by standard handwashing.

(Boyce et al. 2002; McCormick et al. 2000; WHO 2009a)

Therefore, while use of hand lotions, creams, and moisturizers by HCWs should be encouraged there are

some considerations: First, to reduce the possibility of the products becoming contaminated, provide

small, individual-use containers or pump dispensers, which are completely emptied and cleaned before

being refilled. Refilling or topping off lotion containers may lead to contamination and proliferation of

bacteria within the lotion. Second, to avoid confusion, hand lotion dispensers should not be located near

dispensers of antiseptic solutions. Additionally, oil-based barrier products, such as those containing

petroleum jelly (e.g., Vaseline® or lanolin), should not be used because they damage latex rubber gloves.

Resistance to Topical Antiseptic Agents

With the increasing use of topical antiseptics, particularly in home settings, concern has been raised

regarding the development of resistance to these antiseptics by microorganisms. Although low-level

bacterial tolerance to commonly used antiseptic agents has been observed, studies have shown no clinical

evidence to date that supports the development of resistant microorganisms following use of any topical

antiseptic agents. (WHO 2009a)

Hand Hygiene

Infection Prevention and Control: Module 2, Chapter 1 11

Lesions and Skin Breaks

Cuticles, hands, and forearms should be free of lesions (e.g., ulcers, abscesses, and tumors), dermatitis,

eczema, and skin breaks (e.g., cuts, abrasions, and cracking). Broken skin should be covered with

waterproof dressings. If covering is not possible, HCWs with active lesions should not perform clinical

duties until the lesions are healed. In particular, surgical HCWs with skin lesions should not operate until

the lesions are healed.

Religious and Cultural Considerations

It is clear that cultural and religious factors strongly influence attitudes toward handwashing. WHO’s

Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Health Care provide information outlining these considerations. (WHO

2009a)

Fingernails

Research has shown that the area beneath the fingernails harbors the highest concentrations of bacteria

on the hands. This area most frequently harbors coagulase-negative staphylococci (a bacterium normally

found on the skin), gram-negative rods (bacteria known to cause infection), Corynebacteria (bacteria), and

yeasts. Fingernails longer than 0.2 cm (0.08 inches) have been shown to increase carriage rates of S.

aureus. Moreover, long nails, either natural or artificial, tend to puncture gloves more easily than short

nails. Therefore, nails should be kept moderately short—not extend more than 0.5 cm (0.2 inches) beyond

the fingertip. (CDC 2002; Fagernes and Lingaas 2011; McGinley et al. 1988; Olsen et al. 1993; WHO 2009a)

Artificial nails

Individuals with artificial nails have been shown to harbor more pathogenic organisms (i.e., disease-

causing microorganisms), especially gram-negative bacilli and yeast, on the nails and in the area beneath

the fingernails. Studies have demonstrated that the longer the artificial nail is, the more likely that a

pathogen can be isolated. Thus, artificial nails (e.g., nail wraps, nail tips, acrylic lengtheners) should not be

worn in clinical areas because they constitute an infection risk in high-risk areas. (Hedderwick et al. 2000;

Jumma 2005; Siegel et al. 2007)

Nail polish

Although there is no restriction on wearing nail polish, it is suggested that surgical HCWs and HCWs

working in specialty areas who want to use nail polish wear freshly applied, clear nail polish. There is

concern that individuals with fresh manicures may be hesitant to perform rigorous hand hygiene in an

effort to protect their nails, although no studies have demonstrated a relationship between freshly applied

nail polish and infection. But, compromises in hand hygiene technique may lead to transmission of

infection. Chipped nail polish supports the growth of larger numbers of organisms on fingernails compared

to freshly polished or natural nails. Also, dark-colored nail polish may prevent dirt and debris under

fingernails from being seen and removed. If nail polish is used, it should not be worn for more than 4 days.

At the end of 4 days, the nail polish should be removed and freshly reapplied, if necessary. (Baumgardner

et al. 1993; CDC 2002; Rothrock 2006)

Jewelry

Although current evidence demonstrates that wearing rings increases hand contamination, no studies

have related this to HCW-to-patient transmission of pathogens. Literature has shown that HCWs wearing

wristwatches had a higher total bacterial count on their hands compared to HCWs without wristwatches.

Surgical team members should not wear rings because it may be more difficult for them to put on surgical

gloves without tearing them. (Fagernes and Lingaas 2011; Siegel et al. 2007; Trick et al. 2003)

Hand Hygiene

12 Infection Prevention and Control: Module 2, Chapter 1

Monitoring Hand Hygiene

The WHO Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Health Care encourage providers in all health care settings to

evaluate, improve, and monitor the reliability of hand hygiene practices with the aim of changing the

behavior of HCWs. Optimizing hand hygiene compliance at the 5 recommended moments for hand

hygiene increases patient safety. (WHO 2009a; WHO 2009e)

Hand hygiene compliance can be monitored both directly and indirectly (see Table 1-1) (WHO 2009a). Each

method of monitoring hand hygiene has its own advantages and disadvantages (see Table 1-2 for

advantages and disadvantages of each of the monitoring techniques). The direct observation of hand

hygiene compliance by a validated observer,

1

however, is considered the “gold standard” in hand hygiene

monitoring. It is often valuable to utilize more than one method of monitoring at the same time. (The Joint

Commission 2009; WHO 2009a)

Table 1-1. Hand Hygiene Observation Methods

Direct Methods of Hand Hygiene Observation Indirect Methods of Hand Hygiene Observation

Direct observation Monitoring consumption of products (soap or

ABHR)

Patient assessment Automated monitoring of use of sinks or ABHR

dispensers

In the implementation of a hand hygiene monitoring program, expectations for performing hand hygiene

should be clearly defined and made known within the health care facility. Policies detailing these

expectations should also be in place. Monitoring should occur on a regular, routine basis and a set

minimum number of observations should be collected in a given monitoring period.

1

Validated observers are observers with excellent skills in monitoring hand hygiene during health care practices. Validation

includes training according to the principles behind the “5 Moments,” training on facility policies related to hand hygiene

expectations, and being monitored and confirmed for correct techniques by senior observers. (WHO 2009a)

Hand Hygiene

Infection Prevention and Control: Module 2, Chapter 1 13

Table 1-2. Advantages and Disadvantages of Various Hand Hygiene Monitoring Approaches

Monitoring Approach Advantages Disadvantages

Direct observations by expert

observers

• Only way to reliably capture all

hand hygiene opportunities

• Details can be observed

• Unforeseen qualitative issues

can be detected while observing

hand hygiene

• Time-consuming

• Skilled and validated observers

required

• Prone to observation, observer, and

selection bias

Self-reports by HCWs

• Inexpensive • Overestimate of true compliance

• Not reliable

Direct observations by

patients

• Inexpensive • Potential negative impact on

patient-HCW relationship

• Reliability and validity required and

remain to be demonstrated

Consumption of hygiene

products (e.g., towels, soap,

and ABHR)

• Inexpensive

• Reflects overall hand hygiene

activity (selection biased)

• Validity may be improved by

using indirect denominators (e.g.,

patient-days or workload that is

converted into total hand

hygiene opportunities)

• Does not reliably measure the need

for hand hygiene (denominator)

• No information about the

appropriate timing of hand hygiene

actions

• Prolonged stocking of products at

ward level complicates and might

jeopardize the validity

• Validity threatened by increased

patient and visitor usage

• Not able to discriminate between

individual or professional group

usage

Reprinted from: WHO Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Health Care: First Global Patient Safety Challenge. Clean Care

Is Safer Care. Process and Outcome Measurement, page 162. © World Health Organization (2009).

Direct Monitoring

The goal of the direct hand hygiene observers is to observe HCWs during their usual patient care activities.

The observers should assess the HCWs’ compliance with indications for hand hygiene and with facility

policies on hand hygiene practices. It is preferable that observers have training and experience as patient

care professionals but this is not necessary.

Validity and reliability

2

are important aspects of direct hand hygiene monitoring. The validity of a new

observer should be confirmed by either joint observations with another confirmed observer or by being

tested through the WHO Training Film, which is available online. Results should be compared and any

discrepancies should be discussed. This process should be repeated until the HCW is fully competent.

(WHO 2009a)

2.

Validity—doing a procedure technically correctly following the “gold standard” for that procedure. Reliability—completing a

procedure technically correctly at all times following the “gold standard” for that procedure.

Hand Hygiene

14 Infection Prevention and Control: Module 2, Chapter 1

Hand hygiene observations should focus on the two essential parameters for determining hand hygiene

compliance:

1. The indication for hand hygiene

2. The observed hand hygiene action related to the indication

When the HCW is observed, the action is considered to have been either “performed” or “not performed.”

(WHO 2006b)

WHO recommends that the “5 Moments” be utilized as a framework for observing opportunities for hand

hygiene. It is possible, however, to simplify which moments are observed, based on the objectives of the

period of observation and/or the resources available. Observation can be limited to certain professional

role categories or disciplines or certain indications within the “5 Moments” (e.g., in some settings it may be

appropriate to observe the action of hand hygiene only before and after contact with the patient or the

patient environment). (WHO 2006b; WHO 2009a)

Observations should be collected in a standard way, such as on a form (see Appendix 1-A) with each hand

hygiene observation session on a separate form. A standard form should have three main sections:

1. A header containing information about the health care facility and the location within the facility

where the session was completed

2. A second header containing information on the session observed

3. Columns below the headers representing the sequence of actions for different HCWs observed

during the same session, with each column representing one HCW (See Appendix 1-A for the WHO

Observation Form – Short Description of Items on the Form.) (WHO 2009a; WHO 2009e)

Content can be adapted to suit the needs of the facility. Appendix 1-B is a sample observation form for

hand hygiene data collection. This form reflects a modified approach that looks at hand hygiene

compliance at room entry and room exit only (useful for areas with single-patient rooms).

Hand hygiene compliance (%) is the simplest way to analyze the hand hygiene data collected. Hand

hygiene compliance is the ratio of the number of actions to the number of opportunities:

Compliance (%) = (# of Hand Hygiene Actions/Total # of Opportunities) x 100

Compliance data can be summarized based on total compliance by HCW, by role or discipline (e.g.,

doctors, nurses), or by location (e.g., ward A, ward B), depending on the objectives of the monitoring

program. It is important to provide feedback and disseminate compliance data to the HCWs and leaders

after the observation session/assessments are completed. Minimizing the delay between observation and

reporting of results may help increase the effects of the monitoring. (WHO 2009a)

There are some limitations with direct monitoring of hand hygiene. For example, HCWs may improve or

modify their behavior in response to being observed or studied, resulting in an overestimate of

compliance. Thus, it is important to be aware of this effect when evaluating compliance rates.

Indirect Monitoring

Indirect hand hygiene monitoring, such as monitoring the consumption of hand hygiene products (e.g.,

soap, ABHR, paper towels) to estimate the number of hand hygiene actions, is a less expensive monitoring

approach and can be useful in settings where resources for direct monitoring are limited. However, this

Hand Hygiene

Infection Prevention and Control: Module 2, Chapter 1 15

methodology requires validation to be most effective. One of the major limitations to this type of indirect

monitoring is that it is impossible to determine if the hand hygiene actions were performed at the proper

moment. (WHO 2009a)

Implementation of a Multimodal Hand Hygiene Improvement Strategy

The WHO Multimodal Hand Hygiene Improvement Strategy identifies key components to address during

the implementation of a hand hygiene improvement strategy. (WHO 2009a; WHO 2009e) (See Appendix 1-

C.) The component are:

• System change to ensure that infrastructure is in place, including availability of ABHR and access to a

safe and continuous supply of water, soap, and towels—to allow HCWs to practice hand hygiene

• Training and education of HCWs

• Monitoring of hand hygiene practices and provision of feedback

• Reminders in the workplace

• Creation of a safety culture

In order to implement these components, the guidelines detail five sequential steps, listed below, with

each step building on the activities and actions in the previous steps (see Figure 1-5). Rather than a linear

process, the five steps should be considered a cyclical process, with each cycle being repeated, refined,

and enhanced at least every 5 years. It is imperative to evaluate success factors and areas of weakness

within the program in order to achieve long-term sustainability and process improvement. (WHO 2009a)

Figure 1-5. Five Steps of the Hand Hygiene Improvement Strategy

Adapted from: WHO Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Health Care: First Global Patient Safety Challenge: Clean Care Is

Safer Care. The WHO Multimodal Hand Hygiene Improvement Strategy, page 99. © World Health Organization

(2009).

Although complex, the hand hygiene improvement strategy lays the groundwork for the implementation

of a sustainable hand hygiene monitoring program. It is aimed at improving hand hygiene compliance and

Hand Hygiene

16 Infection Prevention and Control: Module 2, Chapter 1

increasing patient safety in the health care facility. The basic elements of each step are listed below. (WHO

2009a; WHO 2009e)

Step 1: Facility Preparedness

Assess and ensure the preparedness of the health care facility. Consider the following:

Identify a person or team to coordinate the program.

Identify HCWs and facility leadership who will play a major role in program implementation.

Obtain raw materials to produce ABHR at the health care facility’s pharmacy (if necessary).

Train observers on how to monitor hand hygiene practices.

Train identified persons on how to calculate hand hygiene compliance.

Step 2: Baseline Evaluation

Include a baseline evaluation of hand hygiene practices, facility infrastructure, HCW knowledge, and

current beliefs about hand hygiene. Consider the following:

Survey HCWs on their perceptions of hand hygiene (e.g., do they think hand hygiene is important,

and/or effective, and/or necessary?).

Survey HCWs on their knowledge of hand hygiene (e.g., do they know how and when to perform

proper hand hygiene?).

Look for details in the health care facility’s structure that may help explain current hand hygiene

compliance (e.g., is there easy access to running water, sinks, and/or ABHR?).

Monitor use of soap and ABHR, if applicable.

Collect baseline data on hand hygiene compliance.

Make sure that ABHR and dispensers are available in time for the start of Step 3.

Compile data on hand hygiene practices.

Step 3: Implementation

Implement the planned program. Consider the following:

Share baseline data with HCWs.

Distribute educational materials, hand hygiene guidelines, and/or policies to HCWs.

Distribute ABHR to HCWs.

Measure how much ABHR is used each month.

Hold education and training sessions.

Survey HCWs on their opinion of the ABHR (e.g., do they find it acceptable?).

Continue to monitor hand hygiene compliance observations, if possible.

Meet monthly with key HCWs involved with the hand hygiene program.

Step 4: Follow-Up Evaluation

Evaluate the short-term impact of the implemented hand hygiene program. Considered the following:

Hand Hygiene

Infection Prevention and Control: Module 2, Chapter 1 17

Survey HCWs and health care facility leadership on their perceptions of hand hygiene (e.g., do they

think hand hygiene is important and/or effective and/or necessary?).

Survey HCWs on their knowledge of hand hygiene (e.g., do they know how and when to perform

proper hand hygiene?).

Inspect the health care facility structure to determine if there are still any barriers to hand hygiene

compliance related to structural issues.

Collect data on soap and ABHR use.

Collect data on hand hygiene compliance.

Complete data entry.

Step 5: Development of an Ongoing Action Plan and Review Cycle

Develop an ongoing action plan and review cycle. Consider the following:

Review collected data and results carefully.

Prepare a report of the findings of the entire program.

Share information about the findings of the program with leadership and HCWs.

Create a 5-year plan of action to continue to improve and promote hand hygiene compliance.

Modifying a Hand Hygiene Program

In situations where the complete implementation of the WHO hand hygiene improvement strategy is not

possible, due to either limited resources or time, a hand hygiene improvement team should focus on the

minimum criteria listed below (see Table 1-3). These criteria ensure achievement of each component of

the multimodal strategy and include the most pertinent steps of the program. (WHO 2009a)

Table 1-3. Minimum Criteria for Implementation

Multimodal Component Minimum Criteria for Implementation

1a. System change: ABHR Bottles of ABHR are positioned at the point of care in each

ward or given to HCWs.

1b. System change: Access to safe, continuous

water supply and towels

There is one sink for at least every 10 beds; soap; running

water; and clean, dry towels available at every sink.

2. Training and education A program to update training over the short, medium, and

long term is established.

3. Observation and feedback Two periods of observational monitoring are undertaken, the

baseline evaluation and the follow-up evaluation.

4. Reminders in the workplace “How to” and “5 Moments” posters are displayed in all

wards (e.g., patient rooms, health facility staff areas,

outpatient areas, ambulatory departments).

5. Institutional safety climate The chief executive, chief medical officer/medical

superintendent, and chief nurse all make a visible

commitment to support hand hygiene improvement during

Hand Hygiene

18 Infection Prevention and Control: Module 2, Chapter 1

program implementation (e.g., verbal announcements

and/or formal letters to health facility staff).

Reprinted from: Guide to Implementation: A Guide to the Implementation of the WHO Multimodal Hand Hygiene

Improvement Strategy, page 39. © World Health Organization (2009).

Summary

Hand hygiene is the single most important measure to prevent transmission of infection and is the

cornerstone of IPC. The goal of hand hygiene in health care is to prevent transmission of infections through

removing bacteria from hands at strategic “moments” during the care of patients. Hand hygiene can be

performed using ABHR or by washing hands with water and soap. ABHR has been shown to be more

effective for standard hand hygiene than plain or antimicrobial soaps and more easily available at the point

of care. Despite evidence proving that hand hygiene prevents transmission of infections, compliance with

hand hygiene recommendations during patient care continues to be challenging in all settings and requires

constant and ongoing efforts from IPC staff. The WHO Multimodal Hand Hygiene Improvement Strategy

provides a guide for implementation of a sustainable hand hygiene program at health care facilities.

Hand Hygiene

Infection Prevention and Control: Module 2, Chapter 1 19

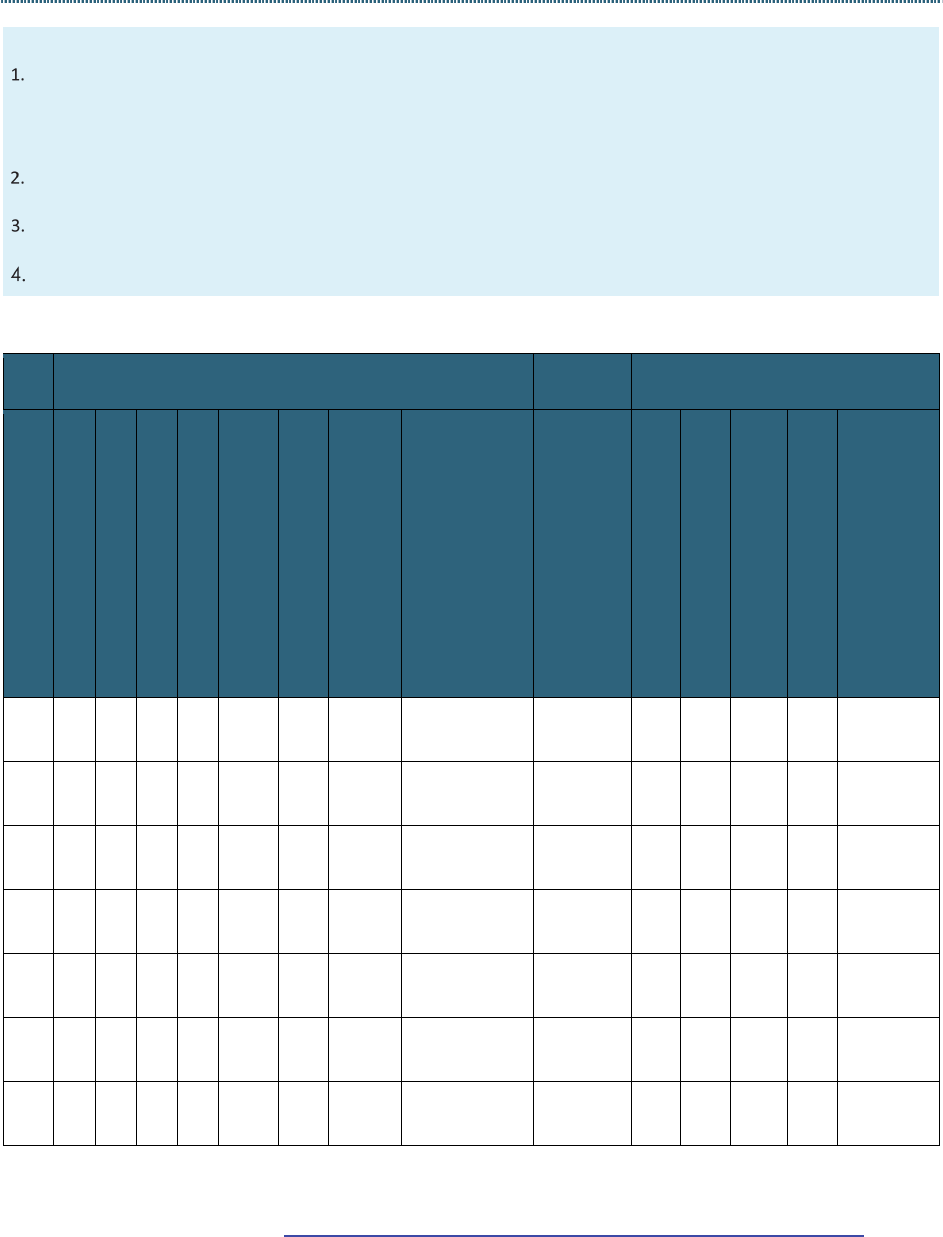

Appendix 1-A. Sample Hand Hygiene Observation Form:

World Health Organization

Source: WHO 2009e.

Hand Hygiene

20 Infection Prevention and Control: Module 2, Chapter 1

Source: WHO 2009e.

Hand Hygiene

Infection Prevention and Control: Module 2, Chapter 1 21

Source: WHO 2009e.

Hand Hygiene

22 Infection Prevention and Control: Module 2, Chapter 1

Appendix 1-B. Sample Hand Hygiene Observation Form

Modified for Room Entry and Exit

FOUR rules for conducting Hand Hygiene Observations

Observe for hand hygiene upon ENTRY and EXIT from Patient Environment

Patient Environment definition:

Private or semi-private room: Crossing room door

Between patients and multi-patient rooms setting: Crossing the “curtain line”

A provider may use the alcohol-based handrub (ABHR) dispenser just outside the room door, inside the room, at the

sink, or the health care worker’s personal ABHR bottle.

DO NOT GUESS. If your view is blocked and you cannot confirm if provider performed hand hygiene, simply check

“Unsure” box.

Do not exceed 3 observations per provider in one session.

UNIT:______________________ DATE:____/_____/____ DAY OF WEEK:_______________

TIME: ________ TO __________ OBSERVER NAME: __________________________________________

Role of Observed Person

Hand

Hygiene

Observed Behavior

Obs #

Nurse*

Midwife

Physicians (all doctors)

CO/PA/Dentist**

Pharmacist/Laboratory Technician

Support Staff

Other Providers (nursing, medical

and other students, and residents)

Other

1=Unknown

2=Clinical

procedure

3=Transport

4=Nursing

care

5=Blood

sample

collection

6= Nutrition

7= Admin

Circle

ONE

Not observed

Hand cleaning with ABHR

Hand wash with soap and water

No hand hygiene

Area location

ENTRY

EXIT

ENTRY

EXIT

ENTRY

EXIT

ENTRY

EXIT

ENTRY

EXIT

ENTRY

EXIT

ENTRY

EXIT

* All types of nursing staff including diploma, degree, post-graduate, supervisor, and assistant.

** CO=Clinical Officer, PA=Physician Assistant.

Adapted from: Johns Hopkins Medicine. Hospital Epidemiology and Infection Control. JHH Hand Hygiene

Compliance Data Collection Form. http://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/heic/docs/HH_observation_form.pdf.

Hand Hygiene

Infection Prevention and Control: Module 2, Chapter 1 23

Appendix 1-C. Implementation of a Multimodal Hand

Hygiene Improvement Strategy

As discussed in this Hand Hygiene chapter, the WHO Multimodal Hand Hygiene Improvement Strategy

identifies five key steps to implement a hand hygiene improvement strategy (see Steps 1–5 below). The

implementation strategy was developed based on a literature review of the implementation science,

behavioral change, spread methodology, diffusion of innovation, and impact evaluation (WHO 2009a). For

detailed information on assessing the economic impact of hand hygiene promotion, refer to WHO

Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Health Care, page 168.

It is important to note that although each step within the process builds upon activities occurring in

previous steps, it should be considered a cyclical process rather than a linear one. Each step of the cycle

should be repeated, refined, and enhanced at least every 5 years in order to maximize the impact of the

hand hygiene program. (WHO 2009a; WHO 2009f)

Step 1: Facility Preparedness

Suggested duration: 3 months

Step 1 in the hand hygiene improvement strategy is to evaluate and prepare the facility for the program.

To have a successful hand hygiene program, careful planning is required from the start of the program.

During Step 1, it is imperative to map out a clear strategy for the entire program.

Step 1: Key Activities in Facility Preparedness

Key Activities

Identify coordinator.

Identify key individuals/groups.

Undertake a situation analysis of hand hygiene practices at the facility.

3

Complete ABHR production, planning, and costing tool.

Train observers/trainers.

Procure raw materials for ABHR (if necessary).

Collect data on costs/benefits of hand hygiene improvement program: costs of program versus reductions in

costs of managing hospital acquired infections.

Undertake training on data entry and analysis.

Steps 1–5 Reproduced from: WHO Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Health Care, page 119. © World Health

Organization (2009): http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44102/1/9789241597906_eng.pdf. Accessed May

6, 2016.

3

See as an example: WHO. 2010. WHO Hand Hygiene Self-Assessment Framework 2010.

http://www.who.int/gpsc/country_work/hhsa_framework_October_2010.pdf?ua=1.

Hand Hygiene

24 Infection Prevention and Control: Module 2, Chapter 1

Step 2: Baseline Evaluation

Suggested duration: 2–3 months

Step 2 includes the baseline evaluation of hand hygiene practices, perceptions, knowledge, and available

infrastructure within the health care facility.

Hand hygiene is the most effective way of preventing the transmission of infections and it is imperative to

collect data on HCWs’ perception on the importance of hand hygiene. These perceptions, as well as other

factors influencing compliance, will provide valuable information for strategy development. Changing

perceptions can be the means by which improvements in hand hygiene practices are achieved. Similarly,

assessing the infrastructure of the health care facility may help explain current hand hygiene practices and

will guide improvement efforts. Lack of access to sinks, running water, and ABHR may all contribute to low

hand hygiene compliance and should be addressed during the implementation planning step.

Step 2: Key Activities in Baseline Evaluation

Key Activities

Undertake baseline assessments:

• Senior manager perception survey

• HCW perceptions survey

• Ward structure survey

• HCW knowledge survey

Begin local production or market procurement of ABHR.

Conduct hand hygiene observations.

Monitor use of soap and ABHR.

Perform data entry and analysis.

Step 3: Implementation

Suggested duration: 3–4 months

Step 3 is implementation of the planned program. Availability of ABHR at the point of care and education

and training for HCWs are crucial to the success of this step. Health care facilities may choose to hold a

high-profile launch event to coincide with the start of the program’s implementation. Publicizing

leadership endorsement and support also helps foster a successful implementation stage (WHO 2009a).

During implementation, it is also important to evaluate HCWs’ tolerance and acceptance of ABHR. Monthly

collection of hand hygiene observations should continue during implementation, if possible. If time and

resources are limited, observations should occur only during Step 2 and Step 4.

Hand Hygiene

Infection Prevention and Control: Module 2, Chapter 1 25

Step 3: Key Activities in Implementation

Key Activities

Launch the strategy.

Provide feedback on baseline data.

Distribute posters.

Distribute ABHR.

Distribute other WHO materials from the Pilot Implementation Pack.

Educate HCWs.

Undertake practical training of HCWs.

Undertake ABHR tolerance tests.

Complete monthly monitoring of usage of products.

Step 4: Follow-Up Evaluation

Suggested duration: 2–3 months

Step 4 is the evaluation of the short-term impact of the hand hygiene improvement strategy. By

performing a follow-up evaluation, facilities will gain information they can use to make future decisions

and take actions related to the hand hygiene program. Compliance with hand hygiene practices among

HCWs is the main indicator that should be evaluated. It is important to note that hand hygiene

improvement activities should continue in the health care facility according to the local action plan, even

during this evaluation step.

WHO has identified the following as key success indicators in the evaluation of the short-term impact of a

hand hygiene program:

Increase in hand hygiene compliance

Improvement in infection control/hand hygiene structures

Increase in usage of hand hygiene products

Improved perception of hand hygiene

Improved knowledge of hand hygiene

The data collected during this evaluation will help shape future actions and the steps the health care

facility may take to maintain high hand hygiene compliance rates over time.

Hand Hygiene

26 Infection Prevention and Control: Module 2, Chapter 1

Step 4: Key Activities in Follow-Up Evaluation

Key Activities

Undertake follow-up assessments:

• HCW knowledge survey

• Senior executive manager perception survey

• HCW perception and campaign evaluation survey

• Facility situation analysis

Conduct data entry and analysis.

Conduct hand hygiene observations.

Continue monthly monitoring of use of products.

Step 5: Developing Ongoing Action Plan and Review Cycle

Suggested duration: 2–3 months

Step 5 is to develop an ongoing action plan and review cycle. The goal of the hand hygiene program is to

create an environment in which performing appropriate hand hygiene is central to the facility’s culture.

Reviewing the results of the data and creating a final report detailing the results of the improvement

program will help condense the findings and will aid in creating a future action plan. Enthusiasm and

motivation for the program must remain high in order to have long-term impacts.

Step 5: Key Activities in Developing an Ongoing Action Plan and Review Cycle

Key Activities

Study all results carefully.

Provide follow-up data.

Develop a 5-year action plan.

Consider scale-up of the strategy.

Hand Hygiene

Infection Prevention and Control: Module 2, Chapter 1 27

References

Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC). 2014. APIC Text of Infection

Control and Epidemiology, 4th ed. Washington, DC: APIC.

Association of periOperative Registered Nurses (AORN) Recommended Practices Committee. 2004.

Recommended practices for surgical hand antisepsis/hand scrub. AORN J. 79(2):416, 418, 421–424, 426,

429–431.

Baumgardner CA, Sallese Marago C, Walz JM, Larson E. 1993. Effects of nail polish on microbial growth of

fingernails: dispelling sacred cows. AORN J. 58(1):84–88.

Bhalla A, Pultz NJ, Gries DM, HICPAC/SHSA/APIC/IDSA Hand Hygiene Task Force. 2004. Acquisition of

nosocomial pathogens on hands after contact with environmental surfaces near hospitalized patients.

Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 25(2):164–167.

Boyce JM, Pittet D, the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. 2002. Guideline for

hand hygiene in health-care settings: recommendations of the Healthcare Infection Control Practices

Advisory Committee and the HICPAC/SHSA/APIC/IDSA Hand Hygiene Task Force. Infect Control Hosp

Epidemiol. 23(Suppl 12):S3–S40.

Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention (CDC). 2002. Guideline for hand hygiene in health-care settings:

recommendations of the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee and the

HICPAC/SHEA/APIC/IDSA Hand Hygiene Task Force. MMWR. 51(RR-16).

http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/rr/rr5116.pdf.

CDC. 2016. CDC/NHSN [National Healthcare Safety Network] Surveillance Definitions for Specific Types of

Infections. http://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/PDFs/pscManual/17pscNosInfDef_current.pdf.

Cohen SH, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al. 2010. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection

in adults: 2010 update by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the Infectious

Diseases Society of America (IDSA). Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 31(5):431–455.

Duckro AN, Blom DW, Lyle EA, Weinstein RA, Hayden MK. 2005. Transfer of vancomycin-resistant

Enterococci via health care worker hands. Arch Intern Med. 165(3):302–307.

Fagernes M, Lingaas E. 2011. Factors interfering with the microflora on hands: a regression analysis of

samples from 465 healthcare workers. J Adv Nurs. 67(2):297–307.

Girou E, Loyeau S, Legrand P, Oppein R, Brun-Buisson C. 2002. Efficacy of handrubbing with alcohol based

solution versus standard handwashing with antiseptic soap: randomized clinical trial. BMJ. 325(7360):362–

365.

Hedderwick SA, McNeil SA, Lyons MJ, Kauffman CA. 2000. Pathogenic organisms associated with artificial

fingernails worn by healthcare workers. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 21(8):505–509.

Johns Hopkins Medicine Department of Hospital Epidemiology and Infection Control. n.d. Hand Hygiene

Compliance Data Collection Form.

http://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/heic/docs/HH_observation_form.pdf.

The Joint Commission. 2009. Measuring Hand Hygiene Adherence: Overcoming the Challenges. Oakbrook

Terrace, IL: The Joint Commission.

Jumma PA. 2005. Hand hygiene: simple and complex. Int J Infect Dis. 9(1):3–14.

Larson E. 1988. A causal link between handwashing and risk of infection? Examination of the evidence.

Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 9(1):28–36.

Larson E. 1999. Skin hygiene and infection prevention: more of the same or different approaches? Clin

Infect Dis. 29(5):1287–1294.

Hand Hygiene

28 Infection Prevention and Control: Module 2, Chapter 1

McCormick RD, Buchman TL, Maki DG. 2000. Double-blind, randomized trial of scheduled use of a novel

barrier cream and an oil-containing lotion for protecting the hands of health care workers. Am J Infect

Control. 28(4):302–310.

McGinley KJ, Larson EL, Leydon JJ. 1988. Composition and density of microflora in the subungual space of

the hand. J Clin Microbiol. 26(5):950–953.

Ojajarvi J. 1980. Effectiveness of handwashing and disinfection methods in removing transient bacteria

after patient nursing. J Hyg (Lond). 85(2):193–203.

Olsen RJ, Lynch P, Coyle MB, et al. 1993. Examination gloves as barriers to hand contamination in clinical

practice. JAMA. 270(3):350–353.

Pittet D, Dharan S, Touveneau S, Sauvan V, Perneger TV. 1999. Bacterial contamination of the hands of

hospital staff during routine patient care. Arch Intern Med. 159(8):821–826.

Riggs MM, Sethi AK, Zabarsky TF, et al. 2007. Asymptomatic carriers are a potential source for transmission

of epidemic and nonepidemic Clostridium difficile strains among long-term care facility residents. Clin

Infect Dis. 45(8):992–998.

Rothrock J. 2006. What Are the Current Guidelines about Wearing Artificial Nails and Nail Polish in the

Healthcare Setting? http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/547793.

Rutala WA. 1996. Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology (APIC)

guideline for selection and use of disinfectants. 1994, 1995, and 1996 APIC Guidelines Committee. APIC.

Amer J Infect Control. 24(4):313–342.

Sanderson PJ, Weissler S. 1992. Recovery of coliforms from the hands of nurses and patients: activities

leading to contamination. J Hosp Inf. 21(2):85–93.

Semmelweiss IP. 1861. Die Aetologie, der Begriff und die Prophylaxis Des Kindbettfiebers. Pest, Hungary:

CA Hattleberi’s Verlags-Expeditions.

Siegel JD, Rhinehart E, Jackson M, Chiarello L, the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory

Committee (HICPAC). 2007. Guideline for Isolation Precautions: Preventing Transmission of Infectious

Agents in Healthcare Settings. Atlanta, GA: CDC/HICPAC.

http://www.cdc.gov/hicpac/2007ip/2007isolationprecautions.html.

Trick WE, Vernon MO, Hayes RA, et al. 2003. Impact of ring wearing on hand contamination and

comparison of hand hygiene agents in a hospital. Clin Infect Dis. 36(11):1383–1390.

World Health Organization (WHO). 2002. Prevention of Hospital-Acquired Infections: A Practical Guide, 2nd

ed. http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/drugresist/WHO_CDS_CSR_EPH_2002_12/en/.

WHO. 2006a. Hand Hygiene: When and How. http://www.who.int/gpsc/tools/Pocket-Leaflet.pdf?ua=1.

WHO. 2006b. Hand Hygiene Technical Reference Manual: To Be Used by Health-care Workers, Trainers and

Observers of Hand Hygiene Practices. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2009/9789241598606_eng.pdf.

WHO. 2009a. WHO Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Health Care: First Global Patient Safety Challenge. Clean

Care Is Safer Care. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2009/9789241597906_eng.pdf.

WHO. 2009b. Definition of terms. In: WHO Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Health Care: First Global Patient

Safety Challenge. Clean Care Is Safer Care. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK144046/.

Hand Hygiene

Infection Prevention and Control: Module 2, Chapter 1 29

WHO. 2009c. How to Handwash. http://www.who.int/gpsc/5may/

How_To_HandWash_Poster.pdf.

WHO. 2009d. Glove Use Information Leaflet. http://www.who.int/

gpsc/5may/Glove_Use_Information_Leaflet.pdf.

WHO. 2009e. Patient Safety. Saves Lives; Clean Your Hands Observation Form.

http://www.who.int/gpsc/5may/Observation_Form.doc.

WHO. 2009f. Guide to Implementation: A Guide to the Implementation of the WHO Multimodal Hand

Hygiene Improvement Strategy. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

http://www.who.int/gpsc/5may/Guide_to_Implementation.pdf.

WHO. 2010a. Hand Hygiene Self-Assessment Framework 2010: Introduction and User Instructions.

http://www.who.int/gpsc/country_work/hhsa_framework_October_2010.pdf?ua=1.

WHO. 2010b. Water for Health: WHO Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality.

http://www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/WHS_WWD2010_guidelines_2010_6_en.pdf? ua=1.

WHO. 2011. Report on the Burden of Endemic Health Care-Associated Infection Worldwide: Clean Care Is

Safer Care. A Systematic Review of the Literature. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/80135/1/9789241501507_eng.pdf.

WHO. n.d. Training Film: A Tool to Help Convey the Concept of the “5 Moments for Hand Hygiene” to

Health-Care Workers. http://www.who.int/gpsc/media/training_film/en/.

Hand Hygiene

30 Infection Prevention and Control: Module 2, Chapter 1