Economic and

Financial Affairs

Spring 2023

ISSN 2443-8014 (online)

European

Economic

Forecast

INSTITUTIONAL PAPER 200 | MAY 2023

EUROPEAN ECONOMY

European Economy Institutional Papers are important reports analysing the economic situation and

economic developments prepared by the European Commission's Directorate-General for Economic and

Financial Affairs, which serve to underpin economic policy-making by the European Commission, the Council

of the European Union and the European Parliament.

DISCLAIMER

The v

iews expressed in unofficial documents do not necessarily represent the views of the European

Commission.

LEGAL NOTICE

Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on behalf of the European Commission is responsible

for the use that might be made of the information contained in this publication.

This paper exists in English only and can be downloaded from

https://economy-finance.ec.europa.eu/ecfin-publications_en.

Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2023

PDF ISBN 978-92-76-61649-8 ISSN 2443-8014 doi:10.2765/707155 KC-BC-23-007-EN-N

© European Union, 2023

Reuse is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. The reuse policy of European Commission

documents is regulated by Decision 2011/833/EU (OJ L 330, 14.12.2011, p. 39). For any use or reproduction

of material that is not under the EU copyright, permission must be sought directly from the copyright holders.

CREDIT

Cover photography: © iStock.com/kwasny221

European Commission

Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs

European Economic Forecast

Spring 2023

EUROPEAN ECONOMY Institutional Paper 200

ABBREVIATIONS

iii

Countries and regions

EU European Union

EA Euro area

BE Belgium

BG Bulgaria

CZ Czechia

DK Denmark

DE Germany

EE Estonia

IE Ireland

EL Greece

ES Spain

FR France

HR Croatia

IT Italy

CY Cyprus

LV Latvia

LT Lithuania

LU Luxembourg

HU Hungary

MT Malta

NL The Netherlands

AT Austria

PL Poland

PT Portugal

RO Romania

SI Slovenia

SK Slovakia

FI Finland

SE Sweden

BA Bosnia and Herzegovina

BR Brazil

CH Switzerland

CN China

IN India

IS Iceland

JP Japan

MD Moldova

NO Norway

MX Mexico

UA Ukraine

UK United Kingdom

US United States of America

AE Advanced economy

CEE Central and Eastern European

EFTA European Free Trade Association

EME Emerging markets economy

EMU Economic and Monetary Union

MENA Middle East and North Africa

ROW Rest of the World

iv

Economic variables and institutions

CPI Consumer price index

ECB European Central Bank

EUI Economic Uncertainty Indicator

ESI Economic Sentiment Indicator

FAO Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

FED Federal Reserve Bank

GDP Gross Domestic Product

GNI Gross National Income

HICP Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices

NEER Nominal Effective Exchange Rate

OPEC Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries

PMI x

Other abbreviations

AF Autumn Forecast

APP ECB asset purchase programme

BCS Joint Harmonised EU Programme of Business and Consumer Surveys

CFCI Composite Financing Cost Indicator

COICOP Classification of individual consumption by purpose

COVID-19 Coronavirus disease 2019

DGSE Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium model

EUCAM European Union Commonly Agreed Methodology

GM European Commission's Global Multi-country model

HDD Heating degree days

NACE Statistical classification of economic activities in the European Community

NFC Non-financial corporation

NGEU NextGenerationEU

LNG Liquefied Natural Gas

PEPP ECB pandemic emergency purchase programme

PPP Purchasing power parity

RRF Recovery and Resilience Facility

RRP Recovery and Resilience Plan

SF Spring Forecast

SME Small and medium-sized enterprise

S&P GSCI Standard and Poor's Goldman Sachs Commodities Index

SVB Silicon Valley Bank

TFP Total factor productivity

TTF Title Transfer Facility

TLTRO III Targeted longer-term refinancing operations

VAT Value-added tax

WiF Winter interim Forecast

Graphs/Tables/Units

bbl Barrel

bcm Billion cubic meters

bn Billion

bp. /bps. Basis point / points

euro/MWh Euro per megawatt hour

GW Giga Watt

lhs Left hand scale

mn Million

pp. / pps. Percentage point / points

pt. / pts. Point / points

v

Q Quarter

q-o-q% Quarter-on-quarter percentage change

rhs Right hand scale

tr Trillion

y-o-y% Year-on-year percentage change

Currencies

EUR Euro

ALL Albanian lek

BAM Bosnian mark

BGN Bulgarian lev

CZK Czech koruna

DKK Danish krone

GEL Georgian lari

GBP Pound sterling

HUF Hungarian forint

ISK Icelandic krona

MDL Moldovan leu

MKD Macedonian denar

NOK Norwegian krone

PLN Polish zloty

RON New Romanian leu

RSD Serbian dinar

UAH Ukrainian hryvnia

RUB Russian ruble

SEK Swedish krona

CHF Swiss franc

JPY Japanese yen

CNY Chinese yuan renminbi

TRY Turkish lira

USD US dollar

CONTENTS

vii

Executive Summary 1

PART I: Economic outlook for EA and EU 7

1. Setting the scene 9

2. Economic outlook 13

2.1. International environment 13

2.2. Financial conditions in the EU 20

2.3. Economic activity 23

2.4. Labour market 33

2.5. Inflation 39

2.6. Current account 45

2.7. Public finances and the fiscal policy stance 46

3. Risks 53

4. Special issues 55

4.1. Medium-term projections of potential GDP growth in turbulent times 55

4.2. The new candidate countries included in the forecast 59

5. Boxes 65

PART II: Prospects by individual economy 67

Euro Area Member States 69

1. Belgium 70

2. Germany 72

3. Estonia 74

4. Ireland 76

5. Greece 78

6. Spain 80

7. France 82

8. Croatia 84

9. Italy 86

10. Cyprus 88

11. Latvia 90

12. Lithuania 92

13. Luxembourg 94

14. Malta 96

15. The Netherlands 98

16. Austria 100

17. Portugal 102

18. Slovenia 104

19. Slovakia 106

20. Finland 108

Non-EA Member States 111

21. Bulgaria 112

22. Czechia 114

23. Denmark 116

viii

24. Hungary 118

25. Poland 120

26. Romania 122

27. Sweden 124

Candidate Countries 127

28. Albania 128

29. Montenegro 130

30. North Macedonia 132

31. Serbia 134

32. Türkiye 136

Other non-EU Countries 139

33. The United Kingdom 140

34. The United States 142

35. Japan 144

36. China 146

37. EFTA 148

38. Russian Federation 151

Statistical Annex 155

Previous European Economic Forecasts 191

LIST OF TABLES

1. Overview - the Spring 2023 Forecast 2

I.2.1. International environment 16

I.2.2. Composition of growth, EU 27

I.2.3. Composition of growth, euro area 32

I.2.4. Labour market outlook, euro area and EU 37

I.2.5. Inflation outlook, euro area and EU 44

I.2.6. General Government budgetary position, euro area and EU 47

I.4.1. Main features of country forecast - Ukraine 61

I.4.2. Main features of country forecast - Moldova 62

I.4.3. Main features of country forecast - Bosnia and Herzegovina 64

LIST OF GRAPHS

I.2.1. Growth in global GDP and global PMIs 13

I.2.2. Global supply chain pressure index 14

I.2.3. Global freight indices 14

I.2.4. Global inflation 14

I.2.5. Oil price assumptions 14

I.2.6. Natural gas price developments and future prices 15

I.2.7. US exchange rate and bond yield 15

I.2.8. Contributions to global GDP growth (excl. EU) 19

I.2.9. Short-term euro interest rate expectations at different dates 21

I.2.10. Short-term interest rate expectations in non-euro area EU Member

States 21

I.2.11. Euro area benchmark interest rates 21

I.2.12. European stock prices 22

ix

I.2.13. Composite Financing Cost Indicator and credit to the euro area

private sector 23

I.2.14. GDP demand-side components, EU excluding IE 24

I.2.15. Saving rates in 2022 24

I.2.16. Short-term indicators, EU 26

I.2.17. ESI - consumer survey results, EU 26

I.2.18. Real GDP growth and its contributions, EU 27

I.2.19. Real gross disposable income and components, EU 28

I.2.20. Investment breakdown and investment rates since 2019, EU

excluding IE 32

I.2.21. Real GDP growth path, EU 33

I.2.22. Cumulative growth performance - distribution across Member

States 33

I.2.23. Labour market recovery since 2019, EU 36

I.2.24. Compensation per employee growth and HICP inflation in 2022

across Member States 36

I.2.25. Labour limiting production and vacancy rates, EU 37

I.2.26. Employment growth and unemployment rate, EU 37

I.2.27. Unemployment rates across Member States, 2022 and 2024 38

I.2.28. Annual energy inflation and contributions from key energy

commodities, euro area 39

I.2.29. Pipeline pressures for consumer food inflation, euro area 40

I.2.30. Pipeline pressures for consumer goods inflation, euro area 40

I.2.31. Share of services with positive inflation and annual inflation of

contact-intensive and other services, euro area 40

I.2.32. Structure of contributions to the annual headline inflation, euro

area 41

I.2.33. Measures of underlying price pressures, euro area 41

I.2.34. Disperion of annual inflation rates, EU 42

I.2.35. Inflation breakdown, EU 42

I.2.36. Inflation expectations derived from implied forward inflation-linked

swap rates 44

I.2.37. Core inflation vs. wage growth, cumulative in 2023-2024 44

I.2.38. Cumulative headline inflation across Member States, 2022-2024 45

I.2.39. Extra-EU trade balance, EU 45

I.2.40. Extra-EU trade balance, trade volume versus value 45

I.2.41. Trade balance and terms of trade of goods, EU 46

I.2.42. Current-account balance, EU 46

I.2.49. RRF grants absorption across Member States 47

I.2.43. Drivers of the change of the government balance, EU 47

I.2.44. Budget balance developments across Member States 47

I.2.45. Expenditure and revenues contributions to the change of general

government balance, EU 47

I.2.52. Fiscal stance in 2023 and 2024 across Member States 47

I.2.46. Public investment in 2019 and 2024 across Member States 48

I.2.47. Drivers of change in the debt-to-GDP ratio, EU 49

I.2.48. Debt developments across Member States 49

I.2.50. Fiscal stance and its components, EU 50

I.2.51. Nationally-financed net primary current expenditure, contribution

to the EU fiscal stance and drivers 50

I.4.1. Potential GDP growth breakdown, EU 56

I.4.2. Potential GDP breakdown, annual averages 2023-27, EU 56

I.4.3. Euro area output gap 58

I.4.4. Euro area potential GDP growth and the contribution of the energy

prices 58

x

LIST OF BOXES

I.1.1. Key assumptions underlying the forecast 10

I.2.1. European gas market: recent developments and outlook 17

I.2.2. Recent developments in bankruptcy declarations in the EU 25

I.2.3. Profit margins and their role in euro area inflation 29

I.2.4. Which Factors Shape Growth and Inflation Going Forward? Model-

Based Insights into the Spring Forecast 34

I.5.1. Some technical elements behind the forecast 65

FOREWORD

xi

The EU economy is managing the adjustment to the shocks unleashed by the pandemic and

wean itself off Russian gas. The modest growth registered in the first quarter of the year dispelled

fears of a winter recession which only a few months ago appeared unavoidable. Survey data,

moreover, suggest that though timid the expansion is set to continue in the second quarter. The

better-than-expected performance at the beginning of the year lifts the forecast for EU economic

growth marginally upwards.

This outcome owes much to the policies put in place by the EU and its Member States.

Diversification of energy sources and infrastructural investment to address gas supply bottlenecks

and boost renewable energy also supported by the Recovery and Resilience Facility have paid

off. Above all, the adaptation of the private sector has been impressive: pushed by high prices,

households and corporations have reduced gas consumption to well below the voluntary target of

15% set in the emergency Council Regulation (EU) 2022/1369. With gas storage levels at seasonal

record highs, the risk of future shortages has significantly abated, while prices are settling at levels

not seen since the summer of 2021.

The EU labour market has been outperforming expectations since the start of the pandemic. The

unemployment rate has hit successive record lows, while activity and employment rates have kept

surging. Average hours worked per person are also slowly converging to pre-pandemic levels,

suggesting that growth has not only been job-rich, but jobs created are of high quality. The outlook

is for unemployment to hover around record low levels, even as job growth takes a breather.

Fallin

measures and the gradual release of the extra savings accumulated during the pandemic mitigate

the negative impact on private consumption. In 2024, real wages are set to recover some of the

lost ground, while profit margins are expected to broadly stagnate.

The resilience of the EU economy, however, has also delayed the slowdown of inflation. Falling

energy commodity prices are driving a sharp fall in energy consumption bills and the overall rate

of price growth from its October peak, but core inflation has been firming. As a result, markets

have raised expectations about future policy rate hikes. The small contraction of core inflation in

April suggests that it has also peaked, but the convergence towards target is now expected to take

longer. Greater persistence of core inflation would call on monetary authorities to act even more

forcefully to stem inflationary pressures.

Fiscal policy has an important role to play at this critical juncture. Governments should seize the

opportunity of falling energy prices to phase out energy support measures, especially the

untargeted ones, to ensure debt sustainability, but also sustain the disinflationary efforts of

monetary authorities and limit the risk of entrenching dangerous inflation differentials. The

legislative proposals for a reformed economic governance framework presented by the

Commission on 26 April 2023 (COM(2023) 240 to 242 final) should help Member States

strengthen public debt sustainability, and promote sustainable, inclusive and resilient growth

through reforms and investment.

Director General

Economic and Financial Affairs

AN IMPROVED OUTLOOK AMID PERSISTENT

CHALLENGES

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

1

Over the past winter, the EU economy performed better than expected.

As the disruptions caused by the war in Ukraine and the energy crisis

clouded the outlook for the EU economy, and monetary authorities

around the world embarked on a forceful tightening of monetary

conditions, a winter recession in the EU appeared inevitable last year.

The Autumn 2022 Forecast had projected the EU economy to contract

in the last quarter of 2022 and the first quarter of 2023. Instead,

latest data point to a smaller-than-projected contraction in the final

quarter of last year and positive growth in the first quarter of this year.

The better starting position lifts the growth outlook for the EU economy

for 2023 and marginally for 2024. Compared to the Winter 2023

interim Forecast, EU GDP growth is revised up to 1.0% in 2023 (from

0.8%) and 1.7% in 2024 (from 1.6%), virtually closing the gap with

potential output by the end of the forecast horizon (see Special Issue

I.4.1). Upward revisions for the euro area are of a similar magnitude,

with GDP growth now expected at 1.1% and 1.6% in 2023 and 2024

respectively. Inflation also surprised again to the upside, and it is now

expected at 5.8% in 2023 and 2.8% in 2024 in the euro area,

respectively 0.2% and 0.3% higher than in winter.

The growth outlook

improves, but inflation is

projected still high this

year

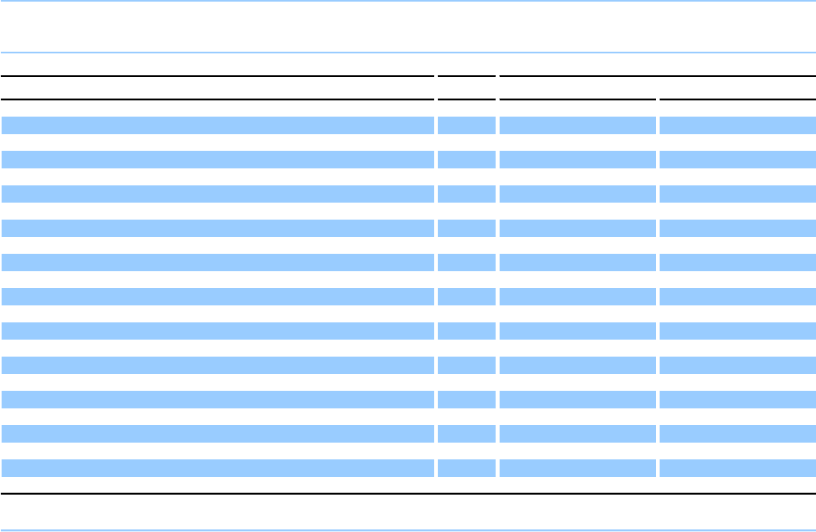

rate

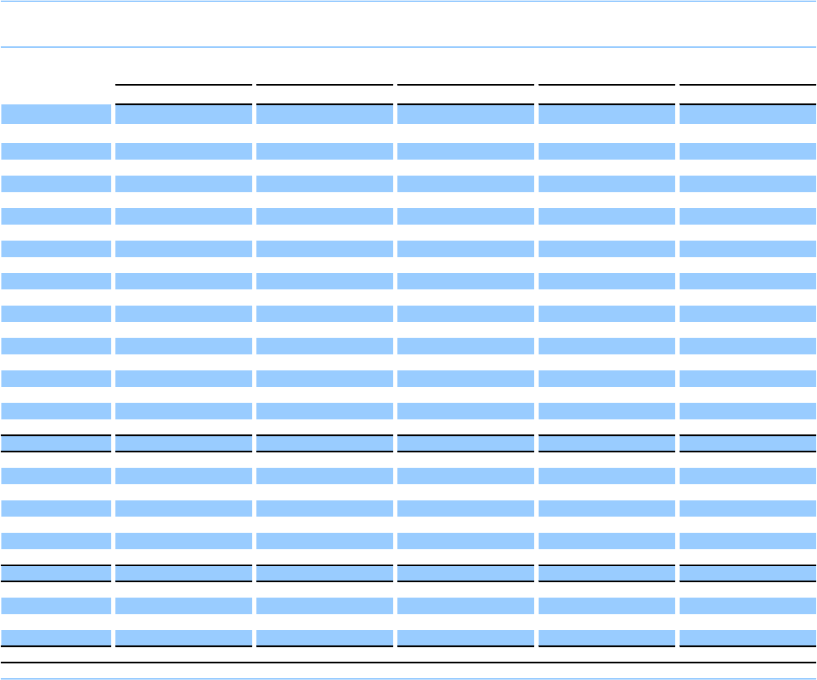

2022 2023 2024 2022 2023 2024 2022 2023 2024 2022 2023 2024 2022 2023 2024

Belgium

3.2 1.2 1.4 10.3 3.4 3.5 5.6 5.8 5.7 -2.9 -1.8 -1.8 -3.9 -5.0 -4.7

Germany

1.8 0.2 1.4 8.7 6.8 2.7 3.1 3.2 3.1 4.0 5.8 5.6 -2.6 -2.3 -1.2

Estonia

-1.3 -0.4 3.1 19.4 9.2 2.8 5.6 6.2 6.1 -1.3 -0.3 0.1 -0.9 -3.1 -2.7

Ireland

12.0 5.5 5.0 8.1 4.6 2.6 4.5 4.3 4.3 8.8 11.1 11.9 1.6 1.7 2.2

Greece

5.9 2.4 1.9 9.3 4.2 2.4 12.5 12.2 11.8 -11.8 -9.2 -7.8 -2.3 -1.3 -0.6

Spain

5.5 1.9 2.0 8.3 4.0 2.7 12.9 12.7 12.4 0.6 1.6 1.5 -4.8 -4.1 -3.3

France

2.6 0.7 1.4 5.9 5.5 2.5 7.3 7.4 7.5 -3.1 -1.5 -1.3 -4.7 -4.7 -4.3

Croatia

6.2 1.6 2.3 10.7 6.9 2.2 7.0 6.6 6.1 -0.2 0.7 1.1 0.4 -0.5 -1.3

Italy

3.7 1.2 1.1 8.7 6.1 2.9 8.1 7.8 7.7 -1.3 0.0 1.3 -8.0 -4.5 -3.7

Cyprus

5.6 2.3 2.7 8.1 3.8 2.5 6.8 6.9 6.4 -9.1 -7.3 -6.9 2.1 1.8 2.1

Latvia

2.8 1.4 2.8 17.2 9.3 1.7 6.9 6.8 6.5 -6.1 -3.4 -2.7 -4.4 -3.8 -2.7

Lithuania

1.9 0.5 2.7 18.9 9.2 2.2 6.0 6.6 6.5 -5.3 -1.1 -0.1 -0.6 -1.7 -1.4

Luxembourg

1.5 1.6 2.4 8.2 3.2 2.6 4.6 4.8 5.0 5.7 7.2 7.4 0.2 -1.7 -1.5

Malta

6.9 3.9 4.1 6.1 5.4 2.8 2.9 2.9 2.9 1.6 3.8 4.1 -5.8 -5.1 -4.5

Netherlands

4.5 1.8 1.2 11.6 4.9 3.3 3.5 3.8 3.9 4.4 6.0 6.1 0.0 -2.1 -1.7

Austria

5.0 0.4 1.6 8.6 7.1 3.8 4.8 4.9 5.0 0.2 0.8 1.2 -3.2 -2.4 -1.3

Portugal

6.7 2.4 1.8 8.1 5.1 2.7 6.0 6.5 6.3 -1.5 1.0 0.8 -0.4 -0.1 -0.1

Slovenia

5.4 1.2 2.2 9.3 7.0 3.8 4.0 3.9 3.8 -0.5 0.9 1.7 -3.0 -3.7 -2.9

Slovakia

1.7 1.7 2.1 12.1 10.9 5.7 6.1 5.8 5.4 -7.8 -6.7 -5.3 -2.0 -6.1 -4.8

Finland

2.1 0.2 1.4 7.2 4.8 2.1 6.8 7.1 6.8 -3.9 -1.9 -1.2 -0.9 -2.6 -2.6

Euro area (20)

3.5 1.1 1.6 8.4 5.8 2.8 6.8 6.8 6.7 0.6 2.1 2.4 -3.6 -3.2 -2.4

Bulgaria

3.4 1.5 2.4 13.0 9.4 4.2 4.3 4.3 4.0 -0.4 0.1 0.2 -2.8 -4.8 -4.8

Czechia

2.5 0.2 2.6 14.8 11.9 3.4 2.2 2.8 2.6 -5.4 -2.5 -0.7 -3.6 -3.6 -3.0

Denmark

3.8 0.3 1.5 8.5 4.3 2.5 4.5 5.0 5.1 13.1 10.7 10.7 3.3 2.3 1.3

Hungary

4.6 0.5 2.8 15.3 16.4 4.0 3.6 4.2 4.0 -8.3 -3.5 -2.8 -6.2 -4.0 -4.4

Poland

5.1 0.7 2.7 13.2 11.7 6.0 2.9 3.3 3.2 -3.2 -1.0 0.5 -3.7 -5.0 -3.7

Romania

4.7 3.2 3.5 12.0 9.7 4.6 5.6 5.4 5.1 -8.8 -7.6 -7.4 -6.2 -4.7 -4.4

Sweden

2.6 -0.5 1.1 8.1 6.0 1.9 7.5 7.7 8.2 4.4 5.9 6.3 0.7 -0.9 -0.5

EU

3.5 1.0 1.7 9.2 6.7 3.1 6.2 6.2 6.1 0.5 2.0 2.3 -3.4 -3.1 -2.4

United Kingdom

4.1 -0.2 1.0 7.9 6.7 2.4 3.7 4.3 4.6 -3.8 -2.2 -1.7 -5.2 -3.2 -2.4

China

3.0 5.5 4.7 : : : : : : 2.2 1.6 1.3 : : :

Japan

1.0 1.1 1.0 2.5 3.2 1.8 2.6 2.5 2.4 2.1 2.6 3.4 -8.0 -6.5 -4.4

United States

2.1 1.4 1.0 8.0 4.3 2.6 3.5 4.1 4.8 -3.9 -3.3 -3.0 -4.0 -5.0 -5.5

World

3.3 2.8 3.1 : : : : : : : : : : : :

Table 1:

Overview - the Spring 2023 Forecast

Real GDP

Inflation

Unemployment

Current account

Budget balance

European Economic Forecast, Spring 2023

2

Model-based analysis suggests that the improved outlook is driven by

the terms-of-trade countershock caused by declining energy prices,

while broad price-increasing supply-side factors lead to inflation

persistence (see Box I.2.4). Recent economic developments seem to

corroborate these results.

estimate, in 2023-Q1 GDP grew by 0.3% in the EU and by 0.1% in the

euro area, a notch above the Winter interim Forecast projections. Lower

energy prices, abating supply constraints, improved business

confidence and a strong labour market underpinned this positive

outcome. As for inflation, the headline index continued to decline in the

first quarter of 2023, amid sharp deceleration of energy prices, but

core inflation firmed, pointing to persistence of price pressures. For the

second quarter, survey indicators suggest continued expansion, with

services clearly outperforming the manufacturing sector and consumer

The EU weathered the energy crisis well thanks to the rapid

diversification of supply and a sizeable fall in consumption (see Box

I.2.1). As the EU approaches the gas-refilling season, gas storage levels

are at comfortable levels and risks of shortages during next winter

have considerably abated. Further supply diversification and the

accelerated increase in renewable power generation are expected to

allow the EU to continue replacing fossil-based sources, including gas,

while reducing the likelihood of renewed price pressures. At the cut-off

date of this forecast, wholesale gas prices were projected to be 25%

expectations at the time of the previous Commission forecast. Oil

prices were also expected to be 10% lower, compared to early

February, in both 2023 and 2024.

The sharp deterioration of terms of trade in 2021 and 2022, as energy

(imported) prices surged, resulted in a transfer of purchasing power

from the EU to the rest of the world. With energy prices rapidly falling,

the expected improvement in terms of trade over the forecast horizon

will drive a reversal of this effect, to the benefit of all domestic sectors

of the economy households, corporates and governments. So far,

households and public finances have taken a large part of the brunt of

high imported inflation, as employment growth only partially offsets

the fall in real wages and public finances set out to protect households

and corporations from the adverse impact of high energy prices.

Companies have been generally successful in passing on higher

production costs to consumers (see Box I.2.3). However, the most

energy-intensive sectors and companies have been struggling. Going

forward, households are set to see their real disposable incomes finally

increase in 2024, while falling energy prices allow governments to

contain the cost of support measures or phase them out altogether.

The progressive firming of core inflation has set EU monetary

authorities on a path of more forceful monetary tightening. In its

meeting of 5 May i.e. shortly after the cut-off of this forecast the

ECB Governing Board lifted policy rates by 25 basis points, down from

50 basis points in the previous two rounds of policy hikes. This was

largely anticipated by market agents. At the cut-off date of this

forecast, the euro area short-term rate was expected to peak at 3.8%

A better-than-expected

start of the year for the

EU economy

The key positive change

underpinning this forecast

is the further fall in

energy commodity prices.

An important terms-of-

trade countershock is

making its way through

the economy

Higher policy interest

rates and increased risk

perception are leading to

further tightening in

financial conditions

Executive Summary

3

in 2023-Q3, before abating in the course of 2024. Long-term interest

rates have hardly moved. Tighter monetary conditions are feeding

through the credit channel: borrowing costs are increasing, while credit

flows are decreasing. The collapse of Silicon Valley Bank and two other

US banks and the problems with Credit Suisse compound with the

effects of higher policy rates. While well-capitalised and thoroughly

supervised, EU ban

further tightening of lending standards. As usual, projections about

interest rates underpinning this forecast reflect market expectations at

the time of the forecast. Moreover, this forecast assumes an orderly

adjustment of the financial sector to higher policy rates, while risks

stemming from exposures to households and corporates are assumed

to be manageable (see Box I.1.1). While bankruptcies increased

significantly towards the end of last year, the surge largely reflects a

clearing of the insolvency backlog created by support schemes during

the pandemic and country-specific developments related to changes in

insolvency regulations (see Box I.2.2).

The tightening of financing conditions is expected to weigh on

investment over the forecast horizon. Housing investment, which is

particularly sensitive to interest rates, is set to contract. By contrast,

business investment is projected to still increase, though at a slower

sheet position. Finally, public investment is forecast to remain buoyant

in both 2023 and 2024 thanks to the continued deployment of the

Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF). Overall, investment growth is

projected to decelerate markedly from 4% in 2022 to 0.9% in 2023.

Gradual normalisation of economic activity is expected to reinvigorate

rall investment growth up

by 2.1% in 2024.

Inflation keeps eroding the purchasing power of consumers. Following

the fall in the last quarter of 2022, private consumption is expected to

have weakened again in the first quarter of this year. Overall, private

consumption growth in the EU in 2023 is projected at 0.5%. As inflation

rebound to 1.8% in 2024. The household saving rate is projected to

decrease in the EU from 13.2% in 2022 to 12.8% in 2024, in line with

its long-term average.

The slower pace of economic expansion in the EU is set to have a

limited impact on the EU labour market. Continued labour market

tightness, labour hoarding due to skill shortages as well as strong

demand, especially for services, are expected to cushion the impact of

the economic slowdown on the labour market. Employment growth is

still forecast at 0.5% in the EU this year. In 2024, employment is set to

keep growing moderately (0.4%), implying a less job-rich growth than

in 2022. The unemployment rate is expected to remain close to its

historical low, at 6.2%, in the EU in 2023, before edging down to 6.1%

in 2024. After growing by 5.0% in 2022, the annual growth rate of

compensation per employee is projected to increase to 5.9% in 2023

before falling to 4.6% in 2024. This means that real wages are still set

to decrease this year, though a slight pick-up in real wages is expected

towards the end of the year.

Tighter financing

conditions weigh on

investment, but

countervailing factors are

at play

Consumption is set to

remain subdued in 2023,

employment growth and

progressive recovery in

real wages

European Economic Forecast, Spring 2023

4

Sharply lower natural gas prices are making their way to retail prices of

gas and electricity, though at varying speeds across EU Member States.

At the same time, all other major inflation subcomponents (processed

and unprocessed food, non-energy industrial goods and services) have

seen their annual inflation rate increase between December and March.

Consequently, core inflation (headline excluding energy and

unprocessed food) continued to rise in early 2023, to a historical high

of 7.6% in March, and core goods and services replaced energy as the

primary driver of headline inflation in the EU. Recent indications on

indicators corroborate the projection of core inflation having peaked in

the first quarter. Core inflation is projected to decline gradually as

profit margins absorb higher wage pressures and tighter financing

conditions prove effective. Average core inflation in 2023, at 6.9% in

the EU, is set to exceed that in 2022, before falling to 3.6% in 2024,

above headline inflation in both forecast years.

The economic expansion and reduced pandemic-related emergency

measures supported the further reduction of the EU government deficit

in 2022, to 3.4% of GDP, despite the expansionary fiscal stance driven

by sizeable energy support measures. In 2023 and especially in 2024,

the phasing out of energy support measures is expected to drive

further deficit reductions on aggregate in the EU, to 3.1% and 2.4% of

GDP, respectively, and the corresponding fiscal impulse should turn

contractionary. However, several Member States are still projected to

see a deterioration in their general government balance in 2023, as

their fiscal stance remains expansionary. While falling energy prices are

helping to contain the cost of existing support measures, several

Member States have introduced new energy support measures or are

extending existing ones. Furthermore, while inflation supported the

improvement in the government balance ratio in 2022, some reversal

of this effect is expected in 2023 as large expenditure items like

pensions and other social transfers, as well as public wages, are

unchanged policies, the deficit reduction is set to be broad-based

across countries. Meanwhile, the EU aggregate debt ratio is expected to

fall in 2023-24 despite debt-increasing primary deficits, thanks to

economic growth and inflation. Higher interest rates are affecting the

cost of servicing public debts only gradually thanks to their long

maturity. The EU debt-to-GDP ratio fell to around 85% of GDP in 2022,

from the record high of 92% recorded in 2020. It is projected to further

decline to below 83% of GDP in 2024, but to remain above the pre-

COVID-19 crisis level of around 79% in 2019.

Global growth, excluding the EU, is expected to fall from 3.2% in 2022

to 3.1% in 2023, before rising back to 3.2% in 2024, broadly

unchanged since the Winter interim Forecast. The outlook for external

demand facing the EU has however been significantly downgraded, as

synchronised weakness in advanced economies (and especially in the

US) weighs heavily on EU exports. The rebound in economic activity in

China, moreover, is set to benefit primarily the domestic sectors,

services in particular, with limited positive spillovers to the EU. Still, net

external demand is expected to contribute positively to GDP due to

weak import dynamics especially for goods in 2023. The current

account balance is set to improve steadily from the record-low surplus

of 1.6% of GDP in 2022 to 3.5% in 2024. The improvement is mainly

The slowdown of core

inflation is set to be more

gradual than previously

projected

The phasing out of

discretionary policy is

expected to drive further

improvements in the

government balance

External balances are set

to improve significantly

Executive Summary

5

driven by the merchandise trade balance, which is forecast to turn

positive this year and improve further next year, largely as a

consequence of falling import prices. The services trade balance is

forecast to remain strong throughout the forecast horizon, with tourism

being a strong driver of the economic rebound. This publication includes

for the first time an overview of the economic structural features,

recent performance and outlook for Ukraine, Moldova and Bosnia and

Herzegovina, which were granted candidate status for EU membership

by the Council in June 2022 and December 2022 (see Special Issue

I.4.2).

While the outlook in our central scenario has not changed much since

last winter, downside risks to the economic outlook have increased.

Persistence of core inflation has emerged as a key risk. It could

continue restraining the purchasing power of households and force a

stronger response of monetary policy, with broad macro-financial

ramifications. Moreover, a surge in risk aversion in financial markets,

following the banking sector turmoil originated in the US, could prompt

a more pronounced tightening of lending standards than assumed in

this forecast. In this context, policy consistency has become even more

important. An expansionary fiscal policy stance would fuel inflation

further, leaning against monetary policy action. In energy markets, the

threat of outright supply shortages for next winter has significantly

abated, but the evolution of prices remains highly uncertain. More

benign developments in energy prices would lead to a faster decline in

headline inflation, with positive spillovers on domestic demand. Risks

new uncertainties following the banking sector turbulence or related to

wider geopolitical tensions. Finally, there is persistent uncertainty

The balance of risks tilts

back to the downside

PART I

Economic outlook for EA and EU

1. SETTING THE SCENE

9

The European economy continues to show resilience in a challenging global context. In

the second half of 2020, a vigorous and synchronised economic rebound had already started to

push up the prices of several global commodities, especially energy and food. The build-up of

tensions and subsequent invasion of Ukraine by Russia intensified pressures on the European gas

market, which at one point even faced risks of outright gas shortages. As the energy crisis loomed

large in Europe, several private sector and institutional forecasters expected the EU economy to

fall into a winter recession. The Commission Autumn Forecast (AF) had projected the EU economy

to contract in the last quarter of 2022 and the first quarter of 2023. Though relatively shallow and

short-lived, the recession was expected to be broad-based across Member States and demand

components. By the time of the Winter interim Forecast (WiF), the EU economy was estimated to

have broadly stagnated in the last quarter of 2022, while tumbling energy prices suggested that it

would avoid a contraction of activity also in the first quarter of 2023. Latest estimates show that

economic activity even managed a small expansion in the first quarter of this year.

A strong labour market has been an important element of resilience. At the end of last

year, the EU labour market hit new records across several key metrics, including activity,

employment and unemployment rates. Since then, the unemployment rate went down further,

reaching 6% in March. Vacancy rates and reported labour shortages remained high by historical

markedly, as employment growth only partially offset the fall in real wages. Nominal wage growth

picked up strongly in the fourth quarter but continued to fall short of inflation dynamics. Key

questions for the forecast are whether tightness in the labour market will ease and the extent to

which wage growth will allow recouping the lost purchasing power, while not adding to inflationary

pressures.

A sizeable terms-of-trade counter-shock is in the making. Diversification of energy supply

and demand reduction allowed the EU to largely wane itself off its dependence on Russian gas,

with no major disruptions for economic activity. With gas storage levels at record high, refilling

needs ahead of next winter appear manageable and gas prices have fallen below pre-war levels

(but are still around twice their pre-COVID-19 readings). At the cut-off date of this forecast,

futures markets pointed to stability at current prices over the forecast horizon. The outlook for oil

implies that the large terms-of-trade shock that weighed on economic performance and public

finances in 2022 is being undone. The direct benefit will be lower energy inflation and lower

production costs across a broad array of goods and services. The projected improvement in the

terms of trade will support the domestic economy, though the distribution of benefit among

households, corporates and governments will depend on the - largely country-specific on fiscal

markets.

Persistent core inflation is slowing down the disinflationary forces of lower energy

prices. The combined impact of pent-up demand, global supply disruptions and war-related

energy and food commodities shocks pushed inflation to successive record highs. While the decline

in energy prices has been stronger than previously expected, price pressures have progressively

broadened and are by now predominantly domestic. As a result, energy and headline inflation

peaked towards the end of 2022, but core inflation was still strong and trending up throughout the

first quarter. High core inflation readings signal some entrenched dynamics that will likely require

more time than previously expected to be brought under control.

Monetary authorities face a delicate balancing act. The adjustment to a rapidly changing

interest rate environment is proving challenging. The collapse of Silicon Valley Bank and two other

US banks, as well as the problems with Credit Suisse, appear by now as largely idiosyncratic

shocks. Especially in the EU, the banking sector is assessed to be solid, thanks to high capital and

liquidity buffers. As largely expected by markets, shortly after the cut-off of this forecast, the ECB

European Economic Forecast, Spring 2023

10

Governing Board lifted policy rates by 25 basis points, down from 50 basis points in the previous

two rounds of policy hikes. While this signals a slowing pace of monetary policy normalisation, the

outlook for the broad financial conditions in the economy has become more uncertain following

the emergence of financial stability risks and increased uncertainty around the inflation outlook.

While the path of monetary policy will remain data-dependent, banks may tighten standards

further as they increase their risk perceptions and retail and wholesale funding becomes costlier

and more difficult to access. Market-based expectations as customary serve as anchor for the

forecast and suggest that the ECB is nearing the final stage of its tightening. This working

assumption is complemented with the additional assumption that EU banks and the broader

financial system will adjust smoothly to a higher interest rate environment and remain overall

well-insulated from potential shocks originating in other jurisdictions. For both assumptions to

prove right, it will be important that fiscal policy does not lean against the action of central banks.

The extent to which governments will seize the opportunity of lower energy prices to

phase out the energy support measures will determine the future trajectory of public

finances. Faced with soaring energy prices, EU governments rolled out sizeable measures to

protect households and corporations from the adverse impact of high energy prices. The measures

are exerting a significant drag on public finances. Yet, helped by strong nominal GDP growth,

general government deficits narrowed more than previously expected in 2022. An important

question for this forecast is to what extent EU governments will be able to seize the opportunity of

lower gas and oil prices to phase out or let expire popular energy subsidies. Continued

expansionary budgetary measures at the current juncture would add to core inflationary pressures

via the demand channel, in turn adding pressure on central banks to step up monetary policy

tightening, with negative implications for public and private sector financing conditions and

financial stability at large.

Beyond these largely endogenous forces, the EU economic outlook continues to depend

crucially on developments in its eastern neighbourhood.

war of aggression against Ukraine, there is no sign of a let-up in the fighting, let alone any

peaceful resolution of the conflict. It is impossible at this stage to foresee the potential unfolding

therefore continues to rest on the assumption that geopolitical tensions will remain at the current

exceptionally high level over the forecast horizon (see Box I.1.1.). As a direct consequence, all

sanctions against Russia stipulated until the cut-off date are assumed to remain in place over the

forecast horizon.

Economic outlook for EA and EU

11

Box I.1.1: Key assumptions underlying the forecast

In a context of still high uncertainty, forecasts continue to rely heavily on ad-hoc assumptions. The

assumptions underpinning the Spring 2023 Forecast are largely unchanged since the Winter 2023

interim Forecast and the Autumn 2022 Forecast.

Russian invasion of Ukraine and geopolitical tensions

The economic impact of the war remains highly uncertain and depends crucially on its evolution. The

central scenario assumes persisting geopolitical tensions. As a result, all sanctions against Russia

stipulated until the cut-off date of the forecast, including those already implemented

annexation of Crimea in 2014, are assumed to remain in place throughout the forecast horizon.

People fleeing the war in Ukraine to the EU

It is assumed that the number of active temporary protection registrations will continue to increase in

the course of 2023, albeit at a slowing pace.

This results in an annual average of active registrations

of about 4.2 million in 2023 and 4.5 million in 2024. The Autumn 2022 Forecast and Winter 2023

interim Forecast assumed that the number of active registrations would reach 4.5 million already by

end-2022 and remain constant thereafter.

(1)

Assumptions on the geographical distribution of people

fleeing the war and their labour market integration remain broadly unchanged compared to the Autumn

2022 Forecast.

The COVID-19 pandemic

The Spring 2023 Forecast assumes that the pandemic will not cause any major disruptions in the EU

economy over the forecast horizon.

Financial stability

The collapse of Silicon Valley Bank and two other US banks, as well as the problems with Credit Suisse,

appear by now as largely idiosyncratic shocks, but in a context of rising interest rates new episodes of

financial stress may emerge. As customary, this forecast assumes the path of monetary tightening

implicit from money market spot and future prices. This working assumption is complemented with the

additional assumption that EU banks and the broader financial system will adjust smoothly to a higher

interest rate environment and remain overall well-insulated from potential shocks originating in other

jurisdictions.

(1)

The number of beneficiaries of temporary protection in the EU reached about 3.8 million by end-2022. See

Eurostat’s monthly statistics at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-

explained/index.php?title=Temporary_protection_for_persons_fleeing_Ukraine_-_monthly_statistics.

2. ECONOMIC OUTLOOK

13

2.1. INTERNATIONAL ENVIRONMENT

The global economy saw a broad-based slowdown in late 2022. After picking up in the third

quarter of 2022, global growth slowed abruptly in the fourth quarter, and is estimated to have

fallen to around 0.7% q-o-q, less than half the pace seen in the previous quarter. Among the

advanced economies, the slowdown was most marked in the EU, while growth in the US fell only

marginally. Activity in the emerging market economies (EMEs) also slowed in the final quarter of

last year, driven in large part by a flat fourth quarter in China. Most G20 economies saw a decline

in the pace of growth in 2022-Q4.

Survey data suggest an acceleration of

economic activity in early 2023, with a

notable pick-up in EMEs and services. After

trending steadily downwards from mid-2022,

global PMI indicators rebounded in late 2022 and

maintained a positive trajectory in early 2023 (see

Graph I.2.1). The global services PMI moved into

expansionary territory, rising from 48 in December

to 54.4 in March. The improvement in services is

visible for advanced and, especially, emerging

economies, influenced by improved prospects for

China following the end of the zero-COVID policy

in December 2022. The PMI global composite

manufacturing index also improved, but remained

weaker and in negative territory, edging up from

48.7 in December to 49.6 in March.

Available GDP data for 2023-Q1 show a very mixed picture, even within regions. In the

United States, growth slowed to 0.3% q-o-q, from 0.6% q-o-q in 2022-Q4. In the EU it rose to

0.3%, from -0.1% in 2022-Q4. China saw growth pick up much more briskly after the re-opening,

growing by 2.2% q-o-q (4.5% y-o-y). Elsewhere in Asia, South Korea saw a modest acceleration, to

0.3%; Hong Kong by 5.3%; while growth in Singapore and Taiwan turned negative.

Global goods trade contracted at the turn of the year. Global world merchandise trade

volumes (imports and exports) rose by just 3.2% in 2022, compared to 10.3% in 2021 (following a

fall of -5.1% in 2020). As economic activity weakened in late 2022, the momentum (3-month-on-

3-month growth) in global goods trade turned negative in November across both advanced

economies and EMEs and remained in negative territory in January and February of 2023.

Emerging markets in Asia, Latin America and MENA have all seen a slowdown in merchandise

trade, with only Central and Eastern Europe seeing an increase. Global trade in goods was 1.8%

lower in the first two months of 2023 compared to the same period a year earlier.

Global supply chain disruptions have largely mended.

Supply Chain Pressure index fell steadily through 2022 and early this year, with the index in March

2023 going below pre-pandemic levels, suggesting that global supply chain operations have been

restored (see Graph I.2.2). Maritime port congestion is also easing, with the share of global freight

in stationary ships falling below 8% in March. Global delivery times from PMIs also improved in

early 2023, with the indices for China, the US and the euro area all moving above 50 in February

2023, and most regions seeing further improvement in March. The slowdown in global goods trade

in recent months has added to downward pressure on container shipping rates, which have fallen

back sharply from the peak reached at end-2021 and are currently at levels last seen in May

2020, before the pandemic-induced spike (see Graph I.2.3). Related to this, the orders-to-inventory

ratios hovered below one in major advanced economies in 2023-Q1.

30

35

40

45

50

55

60

65

70

75

-8

-6

-4

-2

0

2

4

6

8

10

19 20 21 22 23

q-o-q %

Graph I.2.1: Growth in global GDP and global PMIs

GDP contribution emerging markets

GDP contribution advanced economies

Global manufacturing PMI (rhs)

Global services PMI (rhs)

Sources: OECD, IMF and national sources for GDP, S&P Global for PMI.

Index, > 50

= expansion

European Economic Forecast, Spring 2023

14

Global headline inflation fell from the 2022

peaks, but core inflation does not yet show a

clear downward trend. Global inflation rates

surged in 2022, propelled by high demand for

goods, disrupted supply chains and sharply rising

commodity prices particularly after the Russian

invasion of Ukraine in February last year (see

Graph I.2.4). The steep appreciation of the US

dollar through much of 2022 added to global

price pressures for commodity importers and

rising inflation prompted a steep tightening of

monetary policy. Headline inflation rates started

to fall in early 2023 thanks to lower energy prices

and large base effects, reduced supply chain

pressures and a monetary policy effect. Core

inflation has, however, seen little downward adjustment compared to mid-2022.

Oil prices have fallen from the peak reached in mid-2022, though they recorded a short-

lived uptick in early April following an OPEC+ announcement of supply cuts. Oil prices

reached a peak of nearly 120 USD per barrel in mid-2022, but have since fallen steadily and

dipped to as low as 70 USD per barrel in the wake of the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) in

March. The OPEC+ announcement of supply cuts in early April (to cut 1.2 million bbl/day from May

to end of 2023) led to an initial increase in the spot price of around 10 USD per barrel, but spot

prices have subsequently given up most of this gain, and had fallen back to around 80 USD per

barrel at the cut-off date for this forecast.

The outlook is for further moderation in oil

prices (see Graph I.2.5). Like spot prices, futures

prices moved up following the OPEC+

announcement in April, but they still point to

further moderation ahead, with prices for both

2023 and 2024 marginally below those reached

in winter. The oil market remains subject to

considerable uncertainty related to Russian

exports, fuelled by mismatches between official

announcements and observed oil exports. The

embargo on petroleum products and the G7+ oil

price cap appear to have had the intended impact

of lowering prices for Russian oil. While Russia has

managed to redirect crude oil exports to buyers

such as China, India and Türkiye, Urals oil is

trading at a discount of around 20 USD/bbl compared to Brent. The outlook for global demand, and

-2

-1

0

1

2

3

4

5

Jan-20 Jul-20 Jan-21 Jul-21 Jan-22 Jul-22 Jan-23

Graph I.2.2: Global supply chain pressure index

Source: FED of New York.

Standard deviations

from average value

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

700

800

900

May-20 Nov-20 May-21 Nov-21 May-22 Nov-22

Graph I.2.3: Global freight indices

Baltic Dry Index Global Container Freight Index

Sources: Baltic Exchange and Freightos.

Index, 1 May

2020=100

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

Jan-20 Jul-20 Jan-21 Jul-21 Jan-22 Jul-22 Jan-23

Graph I.2.4: Global inflation

CPI Advanced (ex. US) Core CPI Advanced (ex. US)

CPI Emerging Core CPI Emerging

CPI US Core CPI US

Source: FED of Dallas.

Note: Last data point refers to February 2023.

y-o-y %

change

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 2024

price per bbl

Graph I.2.5: Oil price assumptions

USD/bbl

EUR/bbl

assumptions

Economic outlook for EA and EU

15

in particular Chinese demand as mobility recovers, is one of the key factors likely to affect the

evolution of crude prices over the forecast horizon.

European TTF gas prices have dropped

sharply since their August peaks and

continued to slide in the first four months of

2023. The price of TTF gas at the cut-off date of

this forecast was just below 40 Euro/MWh,

compared to around 50 Euro/MWh in the winter.

Futures prices are currently rather flat, hovering

around 50 Euro/MWh over the forecast horizon.

This represents a major decline in contracted gas

prices since autumn, with a fall of more than 50%

in 2023 compared to prices expected in October

(see Box I.2.1 for more details on latest gas

market developments). Compared to the Winter

interim Forecast, average gas prices are 24% and

13% lower in 2023 and 2024, respectively.

The downward trend in agricultural commodity prices continues. The FAO Food Price Index

fell again in March 2023, the twelfth consecutive monthly decline in a row, and prices are now

20.5% below the peak reache

The decline in the index over the past year has been largely driven by large falls in prices for

cereals and vegetable oils, while prices for meat and dairy products show more modest declines.

The price of sugar, by contrast, has been rising for some months and remains above the March

2022 level. The level of food prices overall remains around 30% above 2020 levels.

Metals prices have also fallen back from peaks reached in 2022 and are substantially

lower than a year ago. After spiking in early 2022, the S&P Goldman Sachs Commodities Index

-opening sparked a rally

in early 2023, with prices for steel, iron ore, copper and others seeing a notable bounce. They have,

however, since retreated, with those of zinc and lithium in particular falling considerably. Overall,

prices remain well below 2022 peaks, but showing little clear trend over the past six months.

The March turmoil in the US banking sector

brought financial stability considerations to

the fore. Strong US employment data in January

and an only limited downtick in core inflation in

February prompted a sharp increase in the

spike in US treasury yields in February, with the 2-

year note rising almost 100 basis points, and the

10-year up 50 basis points (see Graph I.2.7). With

the collapse of SVB in early March, the 2-year and

10-year treasury yields fell back close to the

levels seen in January. US and global equity

markets also saw a sharp downward adjustment

in the wake of the SVB collapse and a sell-off in

banking stocks, but the main indices have

rebounded quickly. However, the collapse of another mid-sized US bank, the First Republic Bank,

again raised concerns about contagion in the banking sector. Domestic credit conditions have

tightened, especially among small and medium sized banks, which traditionally provide credit to

smaller, local or more specialized businesses.

Growth in the US is expected to remain subdued in the coming quarters. The slowdown in

2023-Q1 was largely driven by inventories, while personal consumption remained resilient,

supported by strong employment growth. The US labour market remains tight, with high vacancy

20

50

80

110

140

170

200

230

260

Jul-21 Jan-22 Jul-22 Jan-23 Jul-23 Jan-24 Jul-24

Futures (10-day mov avg) At the time of AF 22

At the time of WiF 23 SF 23

Graph I.2.6: Natural gas price developments and future prices

80

85

90

95

100

105

110

115

120

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

3.5

4.0

4.5

5.0

Jan-19 Jan-20 Jan-21 Jan-22 Jan-23

Graph I.2.7: US exchange rate and bond yield

10 year T-bill yield US Dollar Index (rhs)

Sources: US Department of the Treasury and NYSE Euronext.

%

Index, 1 January

2019 = 100

European Economic Forecast, Spring 2023

16

levels and a low unemployment rate, but is expected to soften in 2023-H2 when the full impact of

higher policy rates and tighter credit conditions is set to be felt. After growing by 2.1% in 2022, US

real GDP is forecast to expand at a rate of 1.4% in 2023. Although the US economy is expected to

gradually pick up momentum in the course of 2024, overall growth for the year is projected to be

just 1% in 2024 due to the weak carry-over from 2023.

Prospects for other advanced economies are also subdued. The Japanese economy grew by

1% in 2022, hampered by softer external demand. It is expected to expand by around 1% in both

2023 and 2024, as growth in private demand moderates, with a fading impact of post-COVID-19

reopening and lower fiscal support. The UK economy grew by 4.1% in 2022, but is expected to see

a contraction in 2023 despite the recent falls in energy prices. It is then set to only modestly

rebound in 2024 as high inflation continues to erode household incomes and business investment

remains stagnant. Canada is projected to keep expanding, but at a weaker pace than in 2022.

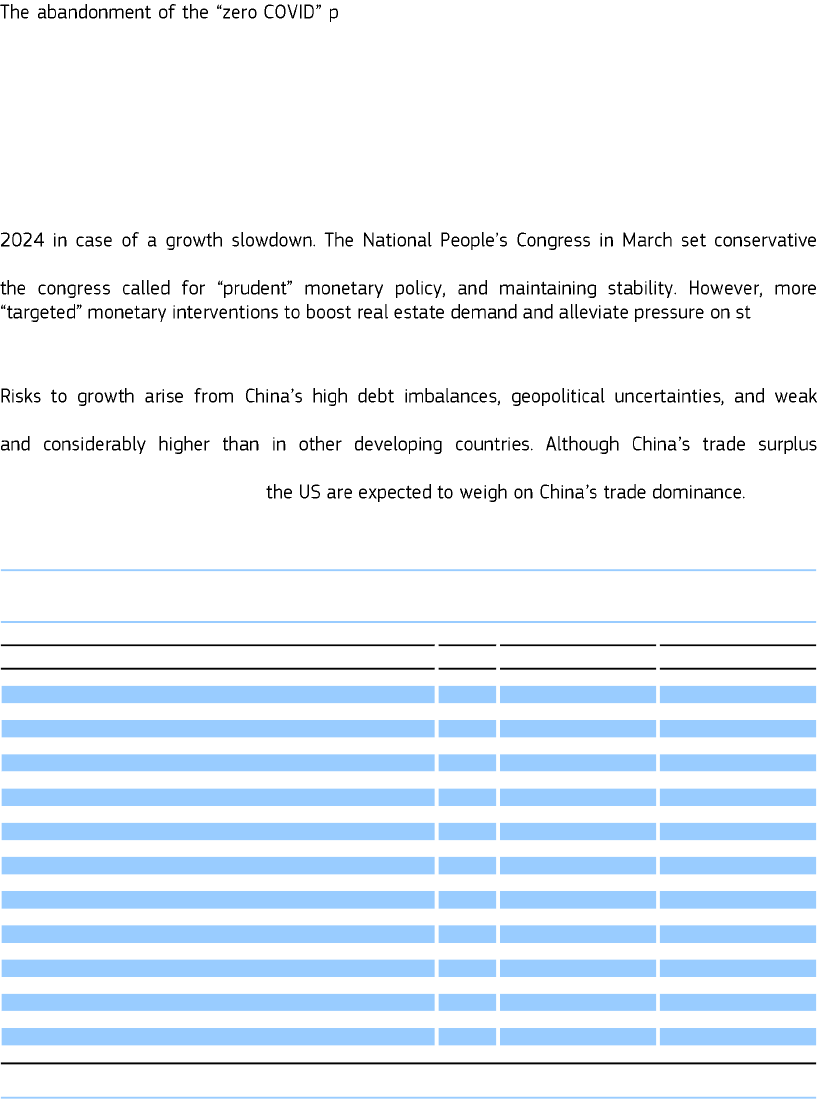

-COVID policy in late

2022, but challenges remain. High frequency indicators (PMIs, consumer confidence, the

property sector) have improved markedly since the government abandoned its strict COVID-19

containment policy, and GDP grew by 4.5% year-on-year in 2023-Q1. Household consumption is

expected to be the main driver of growth in 2023, supported by an improving labour market and a

gradual reduction of the household saving rate towards its pre-pandemic level. Fiscal and

monetary support are set to remain broadly neutral, with the authorities focused on shoring up

debt-related imbalances in the real estate sector and at the local government level. Net exports

are expected to make little contribution to growth, as the surge in goods exports induced by the

pandemic dissipates, while imports are set to pick up due to stronger domestic consumption and

outbound tourism. Overall, GDP growth is forecast to rebound from 3% in 2022 to 5.5% in 2023,

before slowing to 4.7% in 2024.

Consumption is set to remain

depressed and exports weak, affected inter alia by the ban on oil and refined products imports into

the EU, as well as by the oil price caps agreed by the EU with the international G7+ Price Cap

Coalition. With the economy gradually adjusting to the sanctions shock, a shallow recovery is

expected in 2024, driven by domestic demand. Lower commodity revenues, mounting structural

headwinds, including continued sanctions, a shrinking labour supply and constrained external

financing are set to weigh negatively on economic activity.

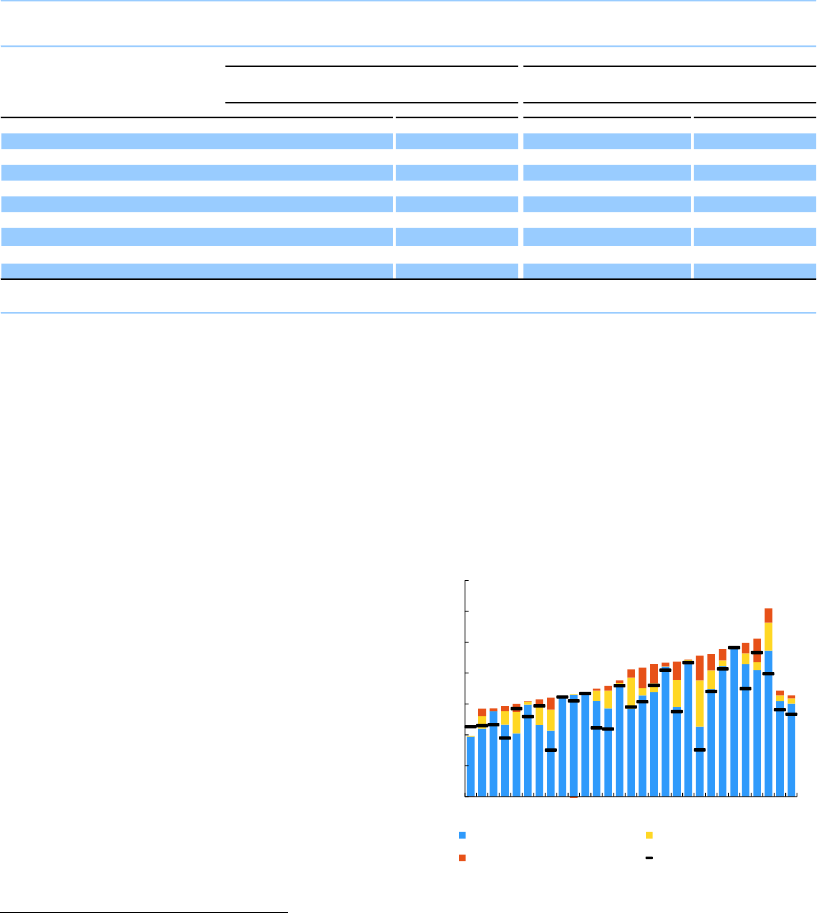

( a ) 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 2024

2022 2023 2024

Japan

3.8 -0.4 -4.3 2.1

1.0 1.1 1.0

1.7 1.6 1.2

United Kingdom

2.3 1.6 -11.0 7.6

4.1 -0.2 1.0

4.2 -0.9 0.9

United States

15.6 2.3 -2.8 5.9

2.1 1.4 1.0

1.8 0.7 1.7

Emerging and developing Asia

33.7 5.2 -1.1 7.2

4.3 5.2 5.1

4.4 4.8 5.0

- China

18.5 6.0 2.2 8.5

3.0 5.5 4.7

3.4 4.5 4.7

- India

7.3 4.6 -6.0 8.9

6.7 5.6 6.6

6.9 6.0 6.3

Latin America

7.4 -0.1 -7.1 6.9

3.4 1.7 2.1

3.0 1.7 2.2

- Brazil

2.3 1.2 -3.3 5.0

2.9 1.0 1.3

2.5 0.8 1.0

MENA

5.8 1.3 -3.3 4.2

5.3 3.2 3.5

5.4 3.5 3.3

CIS

3.9 2.5 -2.4 5.5

-0.8 0.2 2.0

-6.8 -1.1 3.2

- Russia

2.9 2.2 -2.7 5.6

-2.1 -0.9 1.3

-5.1 -3.2 0.9

Sub-Saharan Africa

3.3 2.6 -2.1 4.3

3.4 3.2 3.3

3.3 3.4 3.7

Candidate Countries

2.5 1.5 0.5 9.5

0.0 3.1 4.3

4.8 3.4 3.0

World excluding EU

85.1 2.9 -2.6 6.3

3.2 3.1 3.3

3.1 2.9 3.4

World excluding EU, import

-0.6 -8.3 11.3 4.8 1.4 3.0 4.8 2.5 3.7

EU export market growth

2.5 -8.4 10.1 6.9 1.4 2.9 6.2 1.9 3.5

Real GDP growth

Trade of goods and services, volumes

(a) Relative weights in %, based on GDP (at constant prices and PPS) in 2022.(b) Imports of goods and services to the various markets (incl. EU-markets) weighted according to

their share in country's exports of goods and services.

Table I.2.1:

International environment

(Annual percentage change)

Spring 2023

Autumn 2022

Forecast

Forecast

Economic outlook for EA and EU

17

(Continued on the next page)

Box I.2.1: European gas market: recent developments and outlook

Security of supply and affordability of natural gas are crucial for the EU economy. Gas

households and industry (both 32% of final energy consumption in 2020). Natural gas is also an

important driver of electricity prices across the EU, as it acts as the marginal production source of

power. Whilst to meet the decarbonisation targets the EU aims to shift to low-carbon gases and reduce

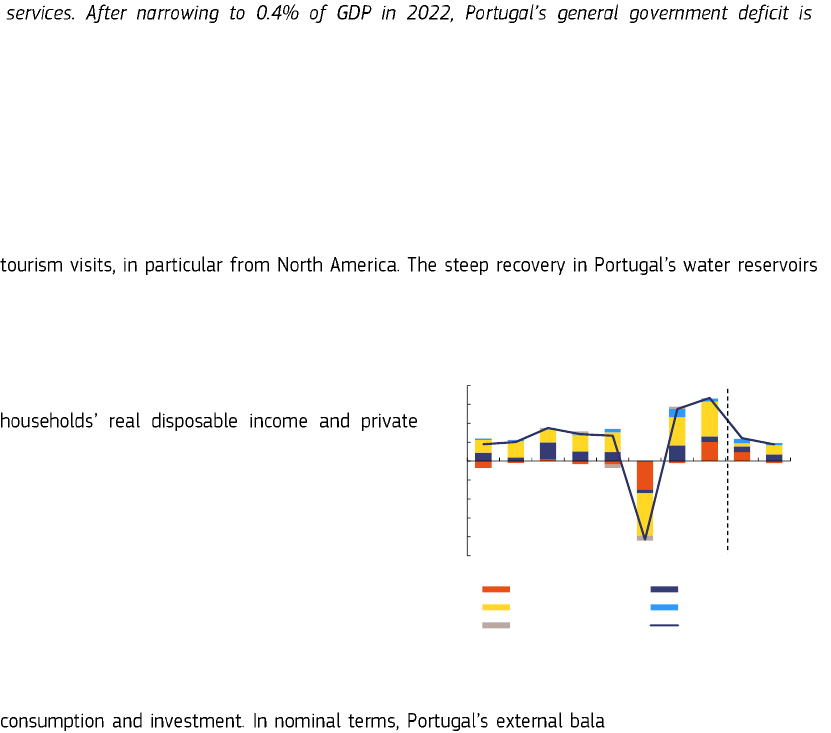

its total gas consumption, natural gas will continue to play an important role in the energy mix in the

coming decade and beyond. For these reasons, the security of supply and affordability of gas remains

a key priority for the EU. Last winter, the EU was able to weather the energy crisis thanks to an effective

diversification of energy supply and a sharp fall in gas consumption, as well as by taking measures to

support the functioning and transparency of price formation in gas markets. The EU is therefore now

in a much better position in terms of its gas supply ahead of the next winter.

The EU diversified its energy supply and tackled bottlenecks in the delivery of LNG gas.

While total gas imports from Russia decreased by 80 billion cubic meters (bcm), and thereby almost

halved in 2022 year-on-year, the EU stepped up its cooperation with other countries to boost gas

imports. In particular, LNG imports from the US more than doubled, to around 50 bcm in 2022. New

floating LNG terminals were made operational in Finland, Germany and the Netherlands. Furthermore,

a record number of more than 56 Giga Watt (GW) wind and solar capacity was installed in the EU in

2022, potentially leading to a reduction of up to 11 bcm of natural gas demand in the power sector.

Gas demand reduction also played a fundamental role. Between August 2022 and March 2023,

households and corporations reduced gas consumption by 18% (or 53 bcm), compared to the 2017-

21 average. This exceeded the objective of the emergency Council Regulation (EU) 2022/1369 setting

a voluntary gas demand reduction target of 15% (or 45 bcm) between August 2022 and March 2023.

The exceptionally high gas prices have been a decisive factor of demand restraint. Wholesale

compared to pre-pandemic levels of around 10- These very high prices reflected the

synchronised surge in demand from Member States in order to refill depleted gas storages ahead of

the winter season, amid fears of shortages in the market due to the unprecedented reduction in Russian

supplies and limited physical capacity to import LNG into the EU.

(1)

The available empirical analysis

suggests that gas demand is relatively inelastic to prices.

(2)

Historically, however, fluctuations in prices

-linear in the

presence of very large price increases, like the ones experienced in 2022. Therefore, part of the gas

demand reduction can be attributed to the price signal.

Industry (excl. power generation) contributed about half of the reduction in gas

consumption, partly through output cuts

(3)

. In the summer months, the overall gas demand

reduction was mostly driven by industry, as manufacturing companies were first to reduce their gas

consumption. Gas demand reductions can be driven by savings (behavioural changes and energy

efficiency), fuel-switching to carbon-intensive and/or clean fuels, and production curtailment. Over the

period 2017-22, total manufacturing output was at its highest level in 2022, showing that high energy

prices have not come at the cost of lower overall production. Still, the output of some energy-intensive

sectors, such as basic metals, chemicals, non-metallic minerals and paper products started to decrease

in the second half of 2022. As gas prices are expected to stabilise at a level significantly below the

peak prices of 2022, one can expect gas demand from energy-intensive industries that reduced

(1)

The analysis builds on European Commission (2023).

gas. Staff Working Document SWD(2023) 63 final.

(2)

Labandeira, X., J. M. Labeaga, and X. López-Otero (2017). A meta-analysis on the price elasticity of energy

demand. Energy policy, 102, 549-568.

(3)

Eurostat currently only reports the sectoral detail in terms of gas consumption annually, with a delay of about

one year, which makes a detailed breakdown between sectors challenging. However, to this end, the JRC

analysed gas consumption in seven Member States between Aug-Dec 2022. The reported figure is therefore

based on estimates by the Commission. The figure is derived from an extrapolation of BE, DE, ES, FR, IT, NL,

and RO, representing 78% of consumed gas in the EU. The International Energy Agency and Bruegel derived

similar conclusions.

European Economic Forecast, Spring 2023

18

Box (continued)

(Continued on the next page)

production or switched to more carbon-intensive fuels (rather than structural energy efficient

investments) to bounce back.

The residential and commercial sectors are estimated to have contributed about half of the

gas demand reduction in the EU, also thanks to milder temperatures. Heating of space

represents, on average, around 63% of the final energy consumed by households in the EU

(4)

; lowering

heating is, thus, an impactful way for households to reduce their energy consumption. As the time span

between August and December 2022 had around 8.3% fewer heating degree days (HDD) compared to

the 2017-21 average, the Commission estimates that of the total gas demand reduction, around one-

sixth was induced by milder weather (i.e. gas demand was 5 bcm or 3.0-3.2% lower)

(5)

. This

contribution was concentrated in October and November.

The marginal decrease in gas consumption in the power sector masks important cross-

country differences. Whereas some Member States switched away from gas (e.g. to coal) for

electricity generation, others saw their gas consumption in the power sector increase significantly. For

example, in Spain, gas-fired electricity generation increased significantly due to a combination of

factors, including the Iberian price cap. The cap specifically limited the price increase of gas used by

power plants and increased export of electricity to France, as France needed to compensate for the

lower availability of nuclear capacity and lower hydro production caused by the drought that hit Europe

in summer 2022.

Initiatives to reduce demand and ensure supply were supported by measures to improve the

functioning and transparency of price formation in the EU gas market. This included the

establishment of a daily LNG price assessment for deliveries to the EU and the market correction

mechanism that sets a temporary price ceiling on derivatives when the TTF month-ahead price spikes

s considerably from international prices. Regarding the LNG price

assessment, it further provides transparency to the market on the price of the actual physical deliveries

of LNG in Europe.

Outlook

Gas storage filling levels reached 61% by early May 2023, significantly above 2022 levels

(37%) and above multi-year average (2016-20 average at 43%). In the summer months of

2022, the gas storage levels caught up with the 2017-21 average and continued increasing thereafter.

With a peak at 95% in November 2022, storage levels exceeded the mandatory filling target of 80%

for 2022

(6)

. Since then, the reduction in storage levels during the winter months remained moderate,

when the drop in storage, especially in January, was small compared to previous years. Moving towards

the winter 2023/24, this should facilitate reaching the 90% gas storage target by 1 November 2023

(7)

.

The EU recently agreed to extend the voluntary 15% gas demand reduction target by

another year (until 31 March 2024)

(8)

. Compliance with the regulation should support the filling of

gas storages, keeping prices down and securing enough energy supplies. If the observed gas demand

reduction is sustained, the Commission baseline scenario estimates that storage levels reach 95 bcm

by the end of October 2023, and thereby will be above the 90% storage target, and 43 bcm by the

end of March 2024, leaving a comfortable level of spare gas left coming out of next winter

(9)

. If,

(4)

Eurostat [nrg_d_hhq].

(5)

European Commission SWD(2023) 63 final. IEA (2023) estimated that gas demand was 18bcm lower due to

the weather in 2022 versus 2021.

(6)

Regulation (EU) 2022/1032.

(7)

Implementing Regulation (EU) 2022/2301.

(8)

Council Regulation (EU) 2023/0087.

(9)

European Commission SWD (2023) 63 final. Assumptions:

Storage levels as of 7 March 2023 (58.5 bcm at the end of 5 March).

Non-Russian pipeline supply equal to the average of the last seven months of 2022.

LNG supply equal to the average of the last seven months of 2022, plus 15 bcm/a (1.25 bcm/month) from Apr.

2023.

No gas from Russia via pipeline.

Average demand of the 2017-2021 period, applying percentage reductions as stated.

Exports to Switzerland as in 2021 (latest data available; 2.2 bcm/a, of which 1/3 in summer and 2/3 in winter).

Exports to Ukraine and Moldova of 0.5 bcm/month.

Economic outlook for EA and EU

19

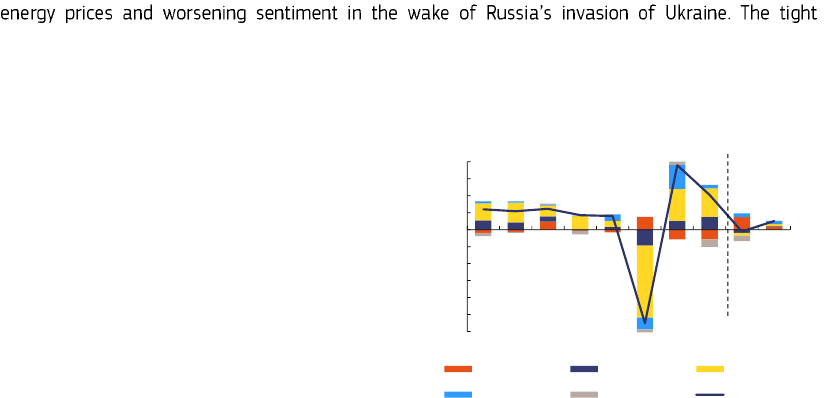

Prospects for emerging markets other than China remain rather muted, with slower

growth expected in 2023, and only a modest pick-up in 2024. The recent falls in commodity

prices will ease pressures in some (commodity importing) EMEs and low-income economies but

worsen prospects for commodity exporters. Provided that the problems in the US (and Swiss)

banking sectors prove to be isolated and idiosyncratic cases, spillovers to EMEs are likely to be

limited. Growth in India is expected to moderate in 2023, from nearly 7% in 2022, with rising

borrowing costs affecting both manufacturing and consumption. In emerging Asia (excluding

China), the late-2022 downturn in the technology and manufacturing cycle appears to have

extended into early 2023, but the outlook for the rest of the year looks brighter as China reopens.

Growth in Central Asian economies is set to slightly pick up compared to 2022, when it was

negatively affected by spillovers from Russia. In South Africa, recurrent and increasingly larger

electricity supply problems are constraining growth. A combination of high inflation, sharp

monetary policy tightening and lower commodity prices are set to dampen activity in Brazil,

Argentina, and Mexico.

Global growth (including the EU) is expected

to slow from 3.3% in 2022 to 2.8% in 2023,

before rising to 3% in 2024. This is still

somewhat below the average global growth rate

over the period 2010-19 (3.5%). Excluding the EU,

global growth is projected to fall from 3.2% in

2022 to 3.1% in 2023, then rise back to 3.3% in

2024 (see Table I.2.1 and Graph I.2.8). Compared

to the Winter interim Forecast, these projections

are slightly higher for 2023 but marginally lower

for 2024. The advanced economies are expected

to see growth slow from 2.6% in 2022 to 1.3% in

2023, and then grow by 1.5% in 2024. Growth in

EMEs outside of China is also forecast to slow,

from around 4.3% in 2022 to 3.4% in 2023,

before picking up to close to 4% in 2024. The key outlier among emerging markets is China, with

somewhat faster growth expected in 2023 than in 2022, partially offsetting the slower growth in

advanced economies and elsewhere.

The outlook for global trade is equally subdued, with a sharp slowdown expected in

2023 and some recovery in 2024. Global merchandise trade will continue to be influenced by

Box (continued)

however, the EU does not keep the 15% gas demand reduction over the next year (compared to the

2017-21 period), storage levels could decline to rather low levels at the end of winter 2024.

The threat of outright shortages has significantly abated, but the evolution of prices

remains highly uncertain. High gas storage levels and supply diversification have reduced the risk

of renewed stress in European gas markets. Market expectations

(10)

until the end of winter 2023/24

foresee wholesale gas prices stabilising just above 50 , about one-sixth of the peak in 2022,

though still more than twice the pre-crisis levels. Increased demand could, however, reignite price

pressures. This may be triggered by a combination of e.g. a cold winter or hot summer increasing

demand for heating or cooling respectively; lower prices reducing incentives to gas savings and

reversing the gas-to-coal switch in power generation that occurred last year in some countries

increased demand for LNG; and the need to increase gas-fired electricity generation due to low

availability of nuclear capacity and hydropower generation. At the same time, benign weather

conditions and increases in renewable power generation capacity could result in downward pressure

on gas prices, below levels currently suggested by futures contracts.

(10)

ICE Index (2023). Dutch TTF Natural Gas Futures.

2.9

-2.6

6.3

3.2

3.1

3.3

-4

-3

-2

-1

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

19 20 21 22 23 24

pps., %

Other emerging and developing (Latin America, MENA and SSA)

Russia, Eastern Neighbourhood and Central Asia

Other emerging and developing Asia

China

Advanced economies excl. EU

World excl. EU (y-o-y %)

forecast

Graph I.2.8: Contributions to global GDP growth (excl. EU)

European Economic Forecast, Spring 2023

20

the rotation of demand back towards services in the advanced economies. While the opening of

China and the continued recovery in tourism is set to have some offsetting effect, the overall

outlook for global trade growth is weak. Moreover, geopolitical tensions are affecting trade policy,

with a growing use of non-tariff trade restrictions. Overall, the pace of growth of total imports is

projected to decline from 5.6% in 2022 to just 1.9% in 2023, before recovering to 3.3% in 2024.

2.2. FINANCIAL CONDITIONS IN THE EU

Since the Winter interim Forecast, financial conditions in the EU have tightened slightly

further amidst persistent volatility in financial markets. After a strong start to the year,

driven by incipient signs of improvements in the macro-financial environment, positive risk

sentiment reversed abruptly in March when the failure of some US small and mid-size banks and

the takeover of troubled Credit Suisse by UBS caused stress in the banking sector. Following some

market turbulences, risk appetite resurfaced in April, leading to higher valuations in equity markets.

rate hikes in response to persistently high core inflation.

In the first months of this year, the ECB has continued the normalisation of its main

monetary policy instruments. The ECB Governing Council raised its policy rates further by 50

bps. on 2 February and by an additional 25 bps. at its latest meeting in early May, after the cut-off

date of the forecast. Since the beginning of the normalisation process, policy rates have increased

by 375 bps., and as of 10 May 2023, the interest rates on the main refinancing operations,

marginal lending facility and deposit facility are at 3.75%, 4.00% and 3.25% respectively. The size

repayments

(

1

)

and maturing of TLTRO III loans. Furthermore, the ECB has also started to reduce its

asset purchase programme (APP) securities portfolio holdings in March 2023 and is expected to

discontinue the reinvestments under APP as of July 2023. However, it remains committed to

continue reinvesting the principal payments from maturing securities purchased under pandemic

emergency purchase programme (PEPP) until at least the end of 2024. At the same time, the ECB

has reaffirmed its commitment to address fragmentation risks and risks for financial stability. In

the aftermath of the market tensions originated in the US, it stressed that it could provide liquidity

if necessary for financial stability purposes, including through new instruments.

Monetary policy normalisation is expected to translate into further increases in short-

term interest rates while long-term rates would remain stable. Reflecting market

expectations at the cut-off date of this forecast, Euribor-3 months futures suggest that euro area