Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education

Guide to the

Common Program Requirements

(

Residency)

(Version 4.1; updated March 2024)

©2024 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)

1

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education

ACGME Mission

The Mission of the ACGME is to improve health care and population health by assessing and

enhancing the quality of resident and fellow physicians’ education through advancements in

accreditation and education.

ACGME Vision

We envision a health care system in which the Quadruple Aim* has been realized. We aspire to

advance a transformed system of graduate medical education with global reach that is:

• Compet

ency-based with customized professional development and identity formation for

all physicians;

• Led by inspirational faculty role models overseeing supervised, humanistic, clinical

educational experiences;

• Immersed in evidence-based, data-driven, clinical learning and care environments

defined by excellence in clinical care, safety, cost-effectiveness, professionalism, and

diversity, equity, and inclusion;

• Located in health care delivery systems equitably meeting local and regional community

needs; and,

• Graduating residents and fellows who strive for continuous mastery and altruistic

professionalism throughout their careers, placing the needs of patients and their

communities first.

* The Quad

ruple Aim simultaneously improves patient experience of care, population health,

and health care practitioner work life, while lowering per capita cost.

ACGME Values

• Honesty and Integrity

• Accountability and Transparency

• Equity and Fairness

• Diversity and Inclusion

• Excellence and Innovation

• Stewardship and Service

• Leadership and Collaboration

• Engagement of Stakeholders

©2024 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)

2

Int.A, B and C Introduction 6

I.A. and I.A.1. Oversight and Sponsoring Institution 9

I.B.1. Participating Sites 11

I.B.2. and I.B.3. Program Letters of Agreement with AAMC Template 14

I.B.4. Participating Sites Addition and Deletion 18

I.C. Diversity and Inclusion in Workforce Recruitment and Retention 23

I.D.1. - I.D.3. Resources, Sleep Facilities, References, Security 27

I.E. Presence of Other Learners 30

II.A.1.a) and

II.A.1.a).(1)

Program Director Appointment 33

II.A.1.b) Program Director Continuity of Leadership 37

II.A.2. Program Director Support for Administration of Program 39

II.A.3. and

II.A.3.a) - c)

Qualifications of Program Director 42

II.A.4.a).(1) - (5)

Program Director Responsibilities - Professionalism and

Learning Environment

49

II.A.4.a).(6)

Program Director Responsibilities - Submit Accurate and

Complete Information

55

II.A.4.a).(7) -

(9).(a)

Program Director Responsibilities - Raising Concerns and

Sponsoring Institution Policies

62

II.A.4.a).(10) -

(11)

Program Director Documentation and Verification of Resident

Education/VGMET

65

II.A.4.a).(12) Resident Eligibility for Specialty Board Examination 68

II.B.1. and

II.B.2.a) - f)

Faculty Responsibilities 72

II.B.3.a) - b) Faculty Qualifications 76

II.B.4. Core Faculty 82

II.C. and II.D. Coordinator and Other Personnel 87

III.A.1. – III.A.3. Resident Appointments 91

III.B. Resident Complement 105

III.C. Resident Transfers 108

IV.A.1. – IV.A.5. Educational Program Curriculum 112

IV.B. ACGME Competencies 118

IV.B.1.a) Professionalism 122

IV.B.1.b) Patient Care and Procedural Skills 126

IV.B.1.c) Medical Knowledge 128

IV.B.1.d) Practice-based Learning and Improvement 130

IV.B.1.e) Interpersonal and Communication Skills 133

IV.B.1.f) Systems-based Practice 137

©2024 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)

3

IV.C. Curriculum Organization and Resident Experiences 141

IV.C.2. Pain Management and Substance Use Disorder 143

IV.D.1. Scholarship Program Responsibilities 147

IV.D.2. Faculty Scholarly Activity 151

IV.D.3. Resident Scholarly Activity 159

V.A.1.a) - f) Resident Evaluation 164

V.A.1.d).(2) Resident Individual Learning Plans 168

V.A.1.d).(3) Plans for Residents Failing to Progress 171

V.A.2.a).(1) Milestones and Sharing Externally 178

V.A.2.a).(2) Final Evaluation 180

V.A.3.a) - b) Clinical Competency Committee Composition and Role 182

V.B.1. - 3. Faculty Evaluation 184

V.C.1. The Program Evaluation Committee 188

V.C.2. Self-Study 197

V.C.3.a) - f) Board Pass Rates and Ultimate Board Certification 199

VI.A.1.a).(1) – (3) Patient Safety and Quality Metrics 205

VI.A.2. Supervision and Accountability 209

VI.B. Professionalism 215

VI.C. Well-Being 222

VI.D. Fatigue Mitigation 226

VI.E. Clinical Responsibilities, Teamwork, and Transitions of Care 229

VI.F. Clinical Experience and Education 232

©2024 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)

4

Guide to the Common Program Requirements

(Residency)

The Guide to the Common Program Requirements is a living document that will be updated as

the Common Program Requirements change. In addition to this Residency version, the ACGME

has developed a Fellowship version.

This gui

de is available as a downloadable PDF version that can be printed. If referring to a

printed version, periodically check the website for any version updates.

The Guide

should serve as a resource, and the content within it is designed to serve as helpful

guidance and not to be interpreted as additional requirements. It is also not meant to be read

cover to cover in one sitting, but to be referenced as needed throughout the academic year.

If t

here are any conflicts between the Guide and the Common Program Requirements, as

interpreted and implemented by the Review Committees, the interpretation and

implementation of the Review Committees shall control.

Note:

Every set of specialty-specific Program Requirements includes content specific and

unique to the specialty. Specialty Program Requirements are not addressed in this Guide. The

specialty-specific FAQs and other resource documents provided by the respective Review

Committee should be consulted; these are available on the respective specialty section of the

ACGME website. Contact Review Committee staff members with specific questions.

Format

• Requirement text is included on the pages with a blue background.

o Italicized text provides philosophical background; these statements are not Program

Requirements and, therefore, are not citable by Review Committees.

o Text in boxes provides Background and Intent and is also not citable.

o Review Committees may further specify additional Program Requirements only

where bracketed notes indicate that the Review Committee may/must further specify.

• Guidance for understanding and applying individual Program Requirements is included

on the pages with a white background.

• Each entry in the Table of Contents is a link that can be used to jump to a specific topic

area in the Guide.

• The search function allows users to enter key words to quickly locate information.

• Where appropriate, screenshots of what data entry looks like within the ACGME’s

Accreditation Data System (ADS) are included. ADS screenshots may change as

system enhancements are made every month. The Guide will be updated periodically as

these changes occur.

The ACG

ME encourages feedback, comments, and questions about the Guide via this survey.

©2024 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)

5

COMMON PROGRAM REQUIREMENTS

Where applicable, text in italics describes the underlying philosophy of the requirements

in that section. These philosophic statements are not program requirements and are

therefore not citable.

Note: Review Committees may further specify only where indicated by “The Review

Committee may/must further specify.”

Intr

oduction

Int.A

.

Definition of Graduate Medical Education

Graduate medical education is the crucial step of professional

development between medical school and autonomous clinical practice. It

is in this vital phase of the continuum of medical education that residents

learn to provide optimal patient care under the supervision of faculty

members who not only instruct, but serve as role models of excellence,

compassion, cultural sensitivity, professionalism, and scholarship.

Gradua

te medical education transforms medical students into physician

scholars who care for the patient, patient’s family, and a diverse

community; create and integrate new knowledge into practice; and educate

future generations of physicians to serve the public. Practice patterns

established during graduate medical education persist many years later.

Gradua

te medical education has as a core tenet the graded authority and

responsibility for patient care. The care of patients is undertaken with

appropriate faculty supervision and conditional independence, allowing

residents to attain the knowledge, skills, attitudes, judgement, and empathy

required for autonomous practice. Graduate medical education develops

physicians who focus on excellence in delivery of safe, equitable,

affordable, quality care; and the health of the populations they serve.

Graduate medical education values the strength that a diverse group of

physicians brings to medical care, and the importance of inclusive and

psychologically safe learning environments

Graduate medical education occurs in clinical settings that establish the

foundation for practice-based and lifelong learning. The professional

development of the physician, begun in medical school, continues through

faculty modeling of the effacement of self-interest in a humanistic

environment that emphasizes joy in curiosity, problem-solving, academic

rigor, and discovery. This transformation is often physically, emotionally,

©2024 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)

6

and intellectually demanding and occurs in a variety of clinical learning

environments committed to graduate medical education and the well-being

of patients, residents, fellows, faculty members, students, and all members

of the health care team.

Int.B

. Definition of Specialty

[The

Review Committee must further specify]

Int.C

. Length of educational program

[The

Review Committee must further specify]

©2024 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)

7

GUIDANCE

Introduction A (Int.A.) is not a requirement but is a philosophic statement that embodies the

meaning and purpose of graduate medical education (GME). It describes why GME is important

and why programs must ensure that residents are provided with the best education possible.

Introduction B (Int.B.) and Introduction C (Int.C.) address the definition of a specialty and the

length of the educational program for that specialty. These requirements must be further

specified in the specialty-specific Program Requirements.

To revi

ew the specialty-specific Program Requirements:

1. Go to

https://www.acgme.org/specialties/.

2. Select the applicable specialty.

3. Select “Program Requirements and FAQs and Applications” at the top of the specialty

section.

4. Select the subspecialty Program Requirements currently in effect.

For exam

ple, to locate the Program Requirements for Orthopaedic Surgery:

1. Go to: https://www.acgme.org/specialties/

.

2. Select Orthopaedic Surgery.

3. Select “Program Requirements and FAQs and Applications” at the top of the specialty

section.

4. Access a P

DF version of the current “Program Requirements for Orthopaedic Surgery”

by selecting the “Program Requirements Effective [current date]” file in the box labeled

“Orthopaedic Surgery.”

As Progr

am Requirements are revised and approved by the ACGME Board of Directors,

Program Requirements that are approved but not yet effective can be found on that same page,

labeled “Future Effective Date.”

Some s

pecialties have also developed an FAQ document, which complements the specialty

Program Requirements and can be found below the specialty-specific Program Requirements.

©2024 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)

8

COMMON PROGRAM REQUIREMENTS

I. Oversight

I.A. Sponsoring Institution

The Sponsoring Institution is the organization or entity that assumes the

ultimate financial and academic responsibility for a program of graduate

medical education, consistent with the ACGME Institutional Requirements.

When th

e Sponsoring Institution is not a rotation site for the program, the

most commonly utilized site of clinical activity for the program is the

primary clinical site.

Background and Intent: Participating sites will reflect the healthcare needs of the

community and the educational needs of the residents. A wide variety of organizations

may provide a robust educational experience and, thus, Sponsoring Institutions and

participating sites may encompass inpatient and outpatient settings including, but not

limited to a university, a medical school, a teaching hospital, a nursing home, a school

of public health, a health department, a public health agency, an organized health care

delivery system, a medical examiner’s office, an educational consortium, a teaching

health center, a physician group practice, federally qualified health center, or an

educational foundation.

I.A.1

. The program must be sponsored by one ACGME-accredited

Sponsoring Institution.

(Core)

©2024 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)

9

GUIDANCE

Sponsorship and Sponsoring Institution accreditation

Common Program Requirement I.A.1. corresponds with Institutional Requirement I.A.1.:

“Residency and fellowship programs accredited by the ACGME must function under the ultimate

authority and oversight of one Sponsoring Institution. Oversight of resident/fellow assignments

and of the quality of the learning and working environment by the Sponsoring Institution extends

to all participating sites.”

Sponsor

ship of a program includes responsibility for oversight of the Sponsoring Institution’s

and all accredited programs’ compliance with the applicable ACGME requirements, and the

assurance of the resources necessary for graduate medical education.

The ACG

ME Board of Directors delegates authority for accrediting Sponsoring Institutions to the

Institutional Review Committee. The ACGME’s primary point of contact with each Sponsoring

Institution is the designated institutional official (DIO).

For mor

e information about Sponsoring Institutions, refer to the ACGME Institutional

Requirements and Frequently Asked Questions.

©2024 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)

10

COMMON PROGRAM REQUIREMENTS

I.B. Participating Sites

A participating site is an organization providing educational experiences or

educational assignments/rotations for residents.

I.B.1. The pr

ogram, with approval of its Sponsoring Institution, must designate a

primary clinical site.

(Core)

[The Review Committee may specify which other specialties/programs

must be present at the primary clinical site]

©2024 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)

11

GUIDANCE

I.B.1. Primary clinical site designations and Sponsoring Institution approval

The philosophic statement preceding Common Program Requirement I.A defines a program’s

primary clinical site as “the most commonly utilized site of clinical activity for the program.” A

program should follow its Sponsoring Institution’s methods for identifying the primary clinical

site. Typically, the “most commonly utilized” participating site is that which has the highest count

of resident full-time equivalents (FTEs) in a program over an academic year, assuming a full

and evenly distributed resident complement.

ADS screenshot: primary clinical site

In a program’s Accreditation Data System (ADS) profile, the designated primary clinical site can

be found in the “Sites” tab. It is marked as “Primary” in the list of participating sites (# column), is

shaded in yellow, and appears first on the list.

©2024 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)

12

ADS screenshot: identifying the primary clinical site in applications

In applications for ACGME accreditation, when adding participating sites, programs are directed

to identify one of the participating sites as the primary clinical site. Only one site can be

identified as the primary clinical site.

Part

icipating site information listed in ADS, including the designation of the primary clinical site,

implies the Sponsoring Institution’s approval. The ACGME does not provide a standardized

format for documenting institutional approval of these designations. Refer to

specialty-specific

Program Requirements for additional information.

[The Review Committee may specify which other specialties/programs must be

present at the primary clinical site]

Since Review Committees may specify which other specialties/programs must be present at the

primary clinical site, programs must review the specialty-specific Program Requirements:

1. Go to https://www.acgme.org/specialties/.

2. Select the applicable specialty.

3. Select “Program Requirements and FAQs and Applications” at the top of the specialty

section.

4. Select the specialty Program Requirements currently in effect.

Quest

ions about specialty Program Requirements or expectations for the primary clinical site

should be directed to specialty Review Committee staff members. Programs can also access

the Common Program Requirements FAQs

for additional information on participating sites.

©2024 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)

13

COMMON PROGRAM REQUIREMENTS

I.B. Participating Sites

I.B.2.

T

here must be a program letter of agreement (PLA) between the program

and each participating site that governs the relationship between the

program and the participating site providing a required assignm

ent.

(Core)

I.B.2.a

) The PLA must:

I.B.2.a

).(1) be renewed at least every 10 years; and,

(Core)

I.B.2.a

).(2) be approved by the designated institutional official (DIO).

(Core)

I.B.3. T

he program must monitor the clinical learning and working environment

at all participating sites.

(Core)

I.B.3.a

) At each participating site there must be one faculty member,

designated by the program director as the site director, who is

accountable for resident education at that site, in collaboration with

the program director.

(Core)

Background and Intent: While all residency programs must be sponsored by a single ACGME-

accredited Sponsoring Institution, many programs will utilize other clinical settings to provide

required or elective education and training experiences. At times it is appropriate to utilize

community sites that are not owned by or affiliated with the Sponsoring Institution. Some of

these sites may be remote for geographic, transportation, or communication issues. When

utilizing such sites the program must ensure the quality of the educational experience.

Suggested el

ements to be considered in PLAs will be found in the Guide to the Common

Program Requirements. These include:

• Identifying the faculty members who will assume educational and supervisory

responsibility for residents

• Specifying the responsibilities for teaching, supervision, and formal evaluation of

residents

• Specifying the duration and content of the educational experience

• Stating the policies and procedures that will govern resident education during the

assignment

©2024 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)

14

GUIDANCE

The PLA is a written document that addresses graduate medical education (GME)

responsibilities between a program and a participating site at which residents have required

educational experiences.

The As

sociation of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) has developed a PLA

template whic

h

programs can use and modify according to their specific needs.

Note:

• Program directors are responsible for PLAs. Designated institutional officials (DIOs) are

required to review and approve all PLAs.

• A change in program director or DIO does not require updating a PLA with new

signatures.

• PLAs must be updated and renewed at least every 10 years.

• PLAs are required only for sites providing required educational experiences.

• Although the ACGME does not require PLAs for sites providing elective rotations, an

institution or GME office may require a PLA for those sites.

• PLAs are between a program and the participating site and include all rotations taking

place at that participating site.

• PLAs are not required for participating sites under the governance of the Sponsoring

Institution.

The purpose of a PLA is to ensure a shared understanding of expectations for the educational

experience, the nature of the experience, and the responsibilities of the program and the

participating site.

As specified in the Background and Intent under Common Program Requirement I.B.3.a),

suggested elements for a PLA include:

• identifying the faculty members who will assume educational and supervisory

responsibility for residents;

• specifying the responsibilities for teaching, supervision, and formal evaluation of

residents;

• specifying the duration and content of the educational experience (e.g., rotation name,

educational objectives) and

• stating the policies and procedures that will govern resident education during the

assignment.

Addit

ional considerations for PLAs that may be further clarified in specialty-specific FAQs

include:

• the site director may be the program director in some cases, but the program director is

not usually the site director at all participating sites; and

• if the site is distant, the program should consider providing the residents with

accommodation proximate to the participating site.

The ACG

ME requires copies of PLAs to be uploaded in the Accreditation Data System (ADS)

for new program applications and updated applications. Accreditation Field Staff request copies

of and verify PLAs during site visits for applications, initial accreditation, and other types of site

visits. For programs with a status of Continued Accreditation, the PLA is not requested when a

©2024 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)

15

new

participating site is added in ADS. However, the program must provide confirmation that a

PLA is in place and list the effective date. If the effective date is not available, the signature date

may be documented as the effective date.

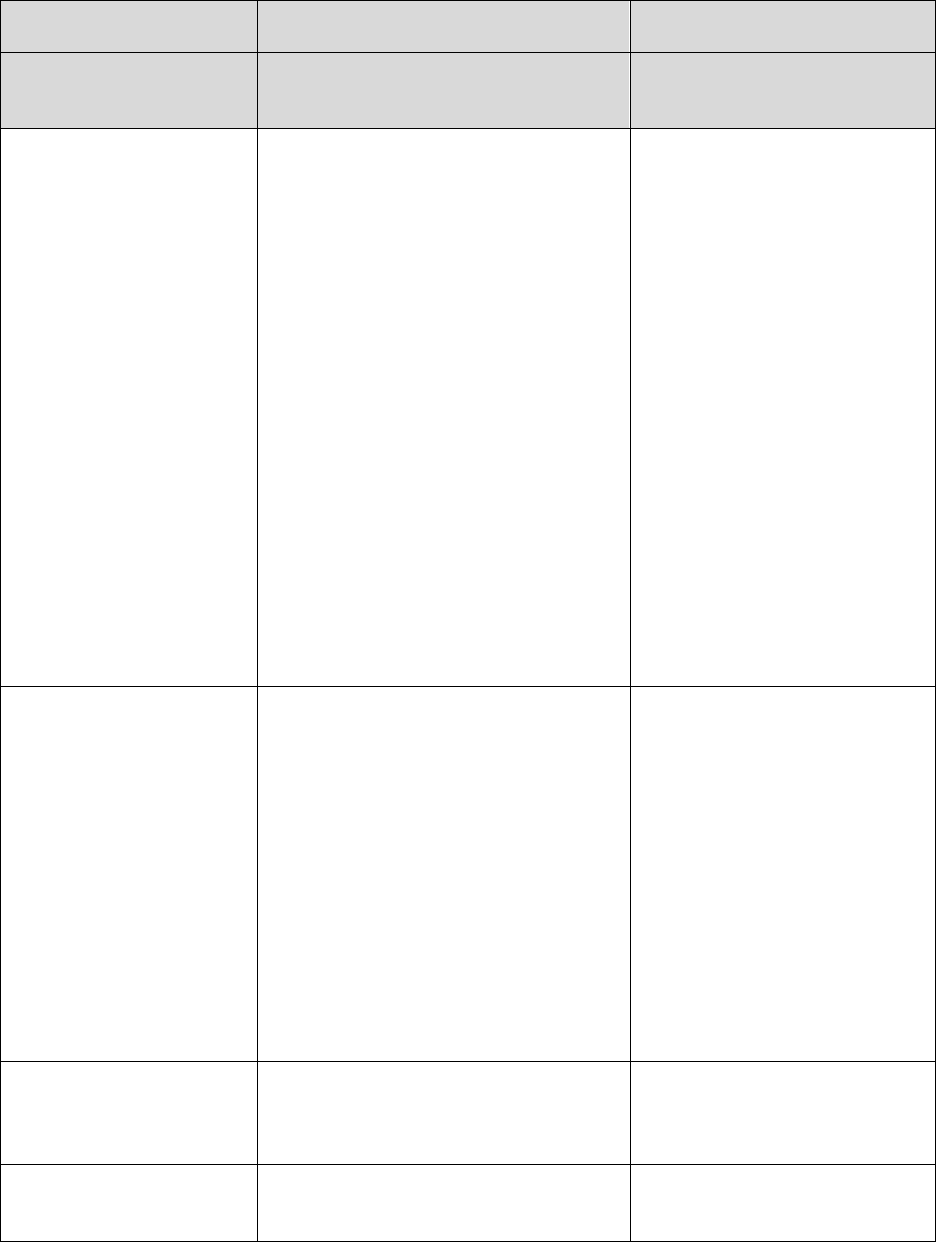

ADS screenshot: adding a participating site and PLA details

When entering a new participating site in ADS, programs are asked to confirm that a PLA exists

and provide its effective date.

Examples of rotations that require a PLA

• one-month required rotation in a pediatric inpatient unit in a children’s hospital in a family

medicine program

• one-month required rotation in rheumatology in an internal medicine program

• two-month required rotation in an emergency department with a Level 1 trauma center at

a site that is not the Sponsoring Institution

• required osteopathic neuromusculoskeletal medicine inpatient rotation

• longitudinal required geriatric experience in a long-term care facility in a family medicine

program

• four-week required retina rotation with a community physician who is not a member of

the medical staff of one of the participating sites in an ophthalmology program

Potential areas for improvement (AFIs) or citations

• failure to have a PLA signed by the DIO, the program director, and the site director for

each site at which residents rotate for a required educational experience

• failure to renew a PLA every 10 years

• incorrect/incomplete participating site information in ADS

©2024 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)

16

In addi

tion to the guidance included here, the Common Program Requirements FAQs

address

multiple questions from the GME community about PLAs

Com

mon Program Requirement I.B.3. requires that the program must monitor the clinical

learning and working environment at all participating sites. The Background and Intent further

explains the rationale for this requirement and is worth repeating: “While all residency programs

must be sponsored by a single ACGME-accredited Sponsoring Institution, many programs will

utilize other clinical settings to provide required or elective education and training experiences.

At times it is appropriate to utilize community sites that are not owned by or affiliated with the

Sponsoring Institution. Some of these sites may be remote for geographic, transportation, or

communication issues. When utilizing such sites the program must ensure the quality of the

educational experience.” Examples of how programs can monitor the experience at all

participating sites include but are not limited to:

• resident evaluations of rotations at each participating site;

• participation of the site director in faculty meetings; and

• inclusion of the site director on the Clinical Competency Committee (CCC), and/or on the

Program Evaluation Committee (PEC).

©2024 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)

17

COMMON PROGRAM REQUIREMENTS

I.B. Participating Sites

A participating site is an organization providing educational experiences or

educational assignments/rotations for residents.

I.B.4. The program director must submit any additions or deletions of

participating sites routinely providing an educational experience, required

for all residents, of one month full time equivalent (FTE) or more through

the ACGME’s Accreditation Data System (ADS).

(Core)

[The Review Committee may further specify]

©2024 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)

18

GUIDANCE

The philosophic statement preceding Common Program Requirement I.B. defines a

participating site as “an organization providing educational experiences or educational

assignments/rotations for residents.” In addition to the primary clinical site, per Common

Program Requirement I.B.4. the program director must add all participating sites routinely

providing a required educational experience of one month or more in ADS.

When applying for accreditation or recognition of a new program, or when a change occurs in

the educational structure of a program and a new participating site at which a required

educational experience of one month or more will occur, the program director must add the new

site in ADS. All sites added in ADS will be visible to both the program and the Review

Committee.

Adding participating sites in ADS that provide elective experiences and/or experiences shorter

than one month in length is not required by the ACGME but may be helpful for some specialties.

[The Review Committee may further specify]

Since Review Committees may specify other requirements related to participating sites,

programs must review the specialty-specific Program Requirements:

• Go to https://www.acgme.org/specialties/

.

• Select the applicable specialty.

• Select “Program Requirements and FAQs and Applications” at the top of the specialty

section.

• Select the specialty Program Requirements currently in effect.

Questions about specialty-specific Program Requirements related to participating sites should

be directed to specialty Review Committee staff. Programs can also access the

Common

Program Requirements FAQs for additional information on participating sites.

ADS screenshot: adding a participating site

To add a site in ADS, log into the program’s ADS profile, then go to the Sites tab on the top

navigation bar and click the “Add Site” blue button.

©2024 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)

19

ADS screenshot: instructions for adding participating sites

For instructions on the participating sites to add into ADS, on the “Sites” tab, click the arrow on

the “Instructions” blue bar to expand it.

ADS screenshot: participating site definition

For the definition of a participating site, click the arrow on the “Participating Site Definition” blue

bar to expand it. (See accompanying screenshot which follows on the next page.)

ADS screenshot: adding participating site details

On the “Add Site” screen, the program will select a site name from the pre-populated dropdown

menu. If the site is not on the list, contact the designated institutional official to have the site

added. Programs may only enter sites that the Sponsoring Institution has approved and added

to ADS. Complete all other information and click the “Save Site” button. (See accompanying

screenshot which follows on the next page.)

©2024 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)

20

NOTE: Programs should complete all requested information. The ACGME may request

additional information from the program if the information submitted is incomplete or inaccurate.

For example:

• Rotation months for each post-graduate year listed for that participating site do not align

with the rotation months on the block diagram.

• The description of the content of the educational experience does not include a rationale

for the addition of the site, faculty coverage, volume/variety of clinical experience, site

support, and/or educational impact.

While copies of Program Letters of Agreement (PLAs) are not required when adding a new

participating site, programs should ensure that a PLA is in place. A copy may be requested by

the ACGME during a site visit or as needed.

©2024 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)

21

ADS screenshot: deleting a participating site

If the program no longer uses a participating site, the site should be removed from their list of

sites in ADS. To remove a site, on the Sites tab hover over the site in the list of participating

sites and click the “X” button.

Once all participating sites have been added to or deleted from ADS, programs should review

the list of participating sites and ensure that they are ordered based on the number of months

residents spend at each site, with the most-used site listed as primary and all other sites listed

in descending order. Programs should also ensure that the number of months for each year of

training totals 12. If the number of months for each year of education and training do not total

12, the “Comments” box should be used to provide an explanation to the Review Committee.

Lastly, programs should ensure that the participating sites listed in ADS match the participating

sites listed on the block diagram, including the number of months residents rotate at each site.

This is a common discrepancy identified by Review Committees.

Review Committee approval of participating site additions and deletions

Once a site is added to or removed from ADS, the Review Committee staff members are

notified of the change. The change is reviewed per the Review Committee process and

programs will receive notification of approval or follow-up from the Review Committee staff.

Common areas for improvement (AFIs) or citations

Some of the most common areas for which programs receive an AFI or citation include:

• the listing of participating sites in ADS does not match information on the block diagram;

• the number of months for each year of education and training listed for each participating

site in ADS is different from the block diagram;

• the number of months for each year of education and training does not total 12 and the

program does not provide an explanation; and

• a site director is not identified or is incorrectly identified on the participating site profile in

ADS and/or the PLA.

©2024 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)

22

COMMON PROGRAM REQUIREMENTS

I.C. Workforce Recruitment and Retention

The program, in partnership with its Sponsoring Institution, must engage in

practices that focus on mission-driven, ongoing, systematic recruitment and

retention of a diverse and inclusive workforce of residents, fellows (if present),

faculty members, senior administrative staff members, and other relevant

members of its academic community.

(Core)

Background and Intent: It is expected that the Sponsoring Institution has, and

programs implement, policies and procedures related to recruitment and retention of

individuals underrepresented in medicine and medical leadership in accordance with

the Sponsoring Institution’s mission and aims.

©2024 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)

23

GUIDANCE

The ACGME is interested in the diversity of the physician workforce because it is essential to

addressing health care access and health equity. While most, if not all, Sponsoring Institutions

have mission statements pertaining to diversity and policies regarding diversity, these serve as

a starting point, and there are aspects of this requirement that may take considerable time to

produce quantifiable results. Common Program Requirement I.C. states that programs must

engage in mission-driven, ongoing, systematic efforts to recruit and retain individuals of diverse

backgrounds as residents, fellows, and faculty. It is important to also consider that the ability to

alter the number of such individuals appreciably will require years of effort to expand the pool of

diverse graduate medical education (GME) applicants. This will require cooperative efforts

among programs within Sponsoring Institutions, cities, and specialties. Therefore, the initial

emphasis is on process, not numerical outcomes.

On June 29, 2023, the United States Supreme Court issued its decisions in Students for Fair

Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College, University of North Carolina

addressing the consideration of race-based affirmative action in university admissions. The

ACGME reaffirms its commitment to its requirements as a way to help eliminate health care

inequities and disparities, to assist Sponsoring Institutions and programs in achievement of their

mission, and to develop a diverse physician workforce to provide care that meets the needs of

marginalized patients in particular, and all patients in general. It is important to note that the

ACGME standards do not require race-based affirmative action to achieve diversity, and this

decision does not require programs and institutions to change their resident selection practices.

The definition of diversity is intended to parallel that of the Association of American Medical

Colleges’ (AAMC) philosophy on Underrepresented in Medicine

, which permits flexibility in

defining the target groups for diversity based on the service demographics of the program that is

underrepresented relative to the workforce for a given role. The population of individuals

considered underrepresented in medicine will include racial and ethnic minority individuals

reflective of the program’s service area, but may also include others the program deems

underrepresented in medicine in the service area, or in the discipline in general. As noted in the

Background and Intent section of Common Program Requirement V.C.1.c) data to be

considered for assessment may include workforce diversity as a core element of a program’s

annual evaluation. Evaluation of workforce diversity should include an assessment of the

demographic population in the area served by the program and the program’s efforts to recruit

and retain a diverse workforce of individuals who are underrepresented in medicine, reflective of

the service area population, and in the roles clarified in Common Program Requirement I.C. i.e.,

residents, fellows, faculty members, senior GME administrative staff members, and other

relevant members of the program’s academic community.

Eac

h program is asked to present the demographic information for all GME learners on the

Resident Roster in the ACGME’s Accreditation Data System (ADS). This information provides

important baseline data on the number of individuals as a function of race/ethnicity and gender.

With time, as efforts to enhance the pool of diverse learners lead to improvements, ACGME

assessment may shift to include the actual increase in the number of diverse learners. To

assess meaningful change, it is essential to track these numbers annually to reveal continued

progress.

©2024 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)

24

It i

s important that the best possible data are entered in the Resident Roster. The gold standard

for obtaining the race and ethnicity for each resident is for the program staff to have a

conversation about the subject and to ask directly how each resident would choose to be

represented on the Roster. An alternative approach for obtaining this information is to transfer

the race/ethnicity and gender information from the electronic application used at the time of

residency selection. This is primary data supplied by the residents themselves and transfer of

this information is perhaps the most efficient way of supplying it to the ACGME.

In 2020, the ACGME introduced the Resident/Fellow Portal, providing residents and fellows

access to ADS. During their educational program, individual residents can use the Portal to

input their personal demographic information at their discretion. Access to the Portal is

automatically provided to individuals in specialties using the Case Log System but must be

requested by all other residents. Since not all residents are automatically granted access to the

Portal, the ACGME will continue to ask programs to provide this information on the Resident

Roster.

The demographic categories used by the ACGME reflect race/ethnicity as White, Black or

African American, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, American Indian or Alaska Native;

and Hispanic, Latino, or of Spanish origin. Programs will select one of these categories. There

are three additional categories: Other, Unknown, and Prefer not to report. Since multiple races

cannot currently be selected, if a resident prefers to identify as multiracial, to the exclusion of a

single race choice, “Other” is the suggested category. If any residents truly do not know their

race/ethnicity (e.g., the resident was adopted or the child of an adopted individual, or the

program was not able to obtain any information pertaining to demographics), only then should

the “Unknown” category be selected.

For gender, the ACGME currently offers four options for programs to report on the Resident

Roster: Male, Female, Non-Binary, and Prefer not to report. For individuals who choose to

identify as male, select Male, and for those who choose to identify as female, select Female.

Those who choose not to identify as solely male or female should select Non-Binary.

Programs are encouraged to describe in detail the specific efforts being made to advance

diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) to increase the number of diverse residents and other

individuals participating in the program (e.g., faculty members and administrative personnel),

consistent with existing law. Evidence-based strategies and success stories illustrating these

efforts are strongly recommended. Examples should include affiliated medical schools or

Sponsoring Institution efforts only if done in partnership with the program. This is an opportunity

to describe practices instituted in the program to result in a diverse recruitment and retention

strategy and an inclusive learning environment. Do not simply copy and paste general diversity

policies and statements. Any numerical data supporting the success of these DEI efforts (e.g.,

number of students involved, success of students after participation) should be included. The

goal is for programs to outline the concrete steps they are taking to foster DEI among early

learners, residents, and other individuals participating in the program rather than broad,

philosophical policies.

Furthermore, ACGME asks programs to quantify efforts to increase the diversity of residents

and individuals participating in the program to provide a baseline to determine the effectiveness

of such measures in the future. Common Program Requirement I.C. focuses on ongoing,

systematic recruitment and retention of a diverse workforce. Programs are encouraged to

continue recruiting diverse classes as they currently do, consistent with existing law. The

©2024 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)

25

requi

rement encourages programs and institutions to engage learners earlier and farther

upstream in the career pathway to provide equitable opportunities, such as by developing

programs for early medical students that introduce specialties; providing research, mentoring,

and shadowing for college and post-baccalaureate students; and/or partnering with local STEM

programs to encourage biomedical careers for high school and elementary school students. For

programs with such efforts already in place, the request for numerical impact will provide a

baseline to track progress. Numerical data that supports the success of these efforts can

include, but is not limited to, measures of practical outcomes, numbers of participants in a given

activity or approach, and any metrics that can be determined to measure how well a program is

achieving diversity in the recruitment and retention of residents and other individuals

participating in the program. It is hoped that this will help assess and accelerate the

effectiveness of equitable opportunities and diversity efforts. Programs may wish to include

numerical data on faculty members and other academic individuals in the program in response

to the question on efforts to increase diversity through faculty recruitment and retention as this

information is not collected elsewhere.

The ACGME has designed a new initiative, ACGME Equity Matters

TM

, to assist programs in

enhancing their diversity, equity, and inclusion. Among other resources, it includes a toolkit of

approaches that address many of the barriers diverse individuals face in the GME environment.

Some ideas employed by the most inclusive programs include having a chief diversity officer

position; creating and supporting a diversity committee; and actively engaging minoritized

individuals in the learning environment to help eliminate barriers to success in recruitment and

retention.

©2024 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)

26

COMMON PROGRAM REQUIREMENTS

I.D Resources

I.D.1 The program, in partnership with its Sponsoring Institution, must ensure

the availability of adequate resources for resident education.

(Core)

[The Review Committee must further specify]

I.D.2. The program, in partnership with its Sponsoring Institution, must ensure

healthy and safe learning and working environments that promote resident

well-being and provide for:

(Core)

I.D.2.a) access to food while on duty;

(Core)

I.D.2.b) safe, quiet, clean, and private sleep/rest facilities available and

accessible for residents with proximity appropriate for safe patient

care;

(Core)

Background and Intent: Care of patients within a hospital or health system occurs

continually through the day and night. Such care requires that residents function at

their peak abilities, which requires the work environment to provide them with the

ability to meet their basic needs within proximity of their clinical responsibilities.

Access to food and rest are examples of these basic needs, which must be met while

residents are working. Residents should have access to refrigeration where food may

be stored. Food should be available when residents are required to be in the hospital

overnight. Rest facilities are necessary, even when overnight call is not required, to

accommodate the fatigued resident.

I.D.2.c) clean and private facilities for lactation that have refrigeration capabilities,

with proximity appropriate for safe patient care;

(Core)

Background and Intent: Sites must provide private and clean locations where residents

may lactate and store the milk within a refrigerator. These locations should be in close

proximity to clinical responsibilities. It would be helpful to have additional support

within these locations that may assist the resident with the continued care of patients,

such as a computer and a phone. While space is important, the time required for

lactation is also critical for the well-being of the resident and the resident’s family as

outlined in VI.C.1.d).

I.D.2.d) security and safety measures appropriate to the participating site;

and,

(Core)

I.D.2.e) accommodations for residents with disabilities consistent with the

Sponsoring Institution’s policy.

(Core)

I.D.3. Residents must have ready access to specialty-specific and other

appropriate reference material in print or electronic format. This must

include access to electronic medical literature databases with full text

capabilities.

(Core)

©2024 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)

27

GUIDANCE

I.D.1. Availability of adequate resources for resident education

[The Review Committee must further specify]

Since Common Program Requirement I.D.1. requires that Review Committees further specify

about the “availability of adequate resources,” programs must review the specialty-specific

Program Requirements:

1. Go to https://www.acgme.org/specialties/

.

2. Select the applicable specialty.

3. Select “Program Requirements and FAQs and Applications” at the top of the specialty

section.

4. Select the specialty Program Requirements currently in effect.

The ACGME monitors compliance with requirements in Common Program Requirements I.D.2.-

I.D.3 in various ways, including:

• questions answered by program leadership as part of an application or during the ADS

Annual Update;

• questions answered by residents and faculty members as part of the annual

Resident/Fellow and Faculty Surveys; and

• questions asked by Accreditation Field Staff during site visits of the program at various

stages of accreditation.

The Resident and Faculty Surveys include several questions that address the Program

Requirements in section I.D. Two resource documents, the Resident/Fellow Survey-Common

Program Requirements Crosswalk and the Faculty Survey-Common Program Requirements

Crosswalk, provide additional information for programs on the key areas addressed by the

survey questions and how they map to the ACGME Common Program Requirements. These

documents can be found at

https://www.acgme.org/data-sys

tems-technical-support/resident-

fellow-and-faculty-surveys/.

I.D.2.a) and I.D.2.b) Access to food and sleep/rest facilities

Programs are expected to partner with their Sponsoring Institutions to ensure residents have

adequate access to food and sleep/rest facilities at all participating sites. Interpretations of the

requirements for space may depend on the attributes of a participating site and the needs of

residents when they are assigned to that site.

Depending on the type of participating site and the type of educational experience (e.g.,

overnight call, outpatient clinic) occurring at that site, there may be differences in the types of

resources provided. Because of site-, program-, and resident-specific factors, the ACGME does

not provide uniform specifications for access to food and the physical space of sleep/rest

facilities beyond the qualities indicated in the requirements and the guidance in the associated

Background and Intent. It is important for Sponsoring Institutions and programs to obtain

resident input when evaluating these aspects of clinical learning environments.

I.D.2.c) Access to lactation facilities

It is critical to acknowledge that the timing of residency often overlaps with the timing of starting

and raising families. Therefore, residents must have access to lactation facilities.

©2024 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)

28

Rooms for lactation must be clean, provide privacy and refrigeration, and be close enough to

the clinical setting to be of use for residents who need them. Simply using a restroom as a

facility for lactation or for medication administration would not meet the standard of cleanliness.

Refrigeration capabilities are essential for storage. In addition, the availability of a computer and

telephone will allow residents, if necessary, to provide continued attention to patient care while

attending to their personal health care needs.

Interpretation of the requirement for “proximity appropriate for safe patient care” is left to the

program and the Sponsoring Institution. The requirements do not dictate a specific distance or a

time element for the resident to get from the lactation facility or room for personal health care

needs to the clinical location. Instead, institutions and programs are urged to consider the

circumstances. For example, a busy, high-intensity clinical location, such as the intensive care

unit, might require that the lactation room is in a location that allows immediate access to the

patient care area, whereas a clinical location that is less busy or intense will not require such

proximity. In addition, it is not necessary for the lactation facility to be solely dedicated to

resident use.

I.D.2.e) Accommodations for residents with disabilities

Programs must work with their Sponsoring Institutions to ensure compliance with institutional

policies related to resident requests for accommodation of disabilities. Common Program

Requirements I.D.2. and I.D.2.e) are companions of Institutional Requirement IV.I.4., which

states, “The Sponsoring Institution must have a policy, not necessarily GME-specific, regarding

accommodations for disabilities consistent with all applicable laws and regulations.”

Laws

and regulations concerning requests for accommodation of disabilities include Title I of the

Americans with Disabilities Act and related enforcement guidance published by the US Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission. Other federal, state, and local laws and regulations may

also apply. It is common for program directors, coordinators, residents, faculty members, and

designated institutional officials to collaborate with their institution’s human resources and legal

departments and/or institutional officers/committees to manage requests for accommodation.

I.D.3. Reference Material

Sponsoring Institutions and programs must ensure that residents have access to medical

literature that supports their clinical and educational work. Common Program Requirement

I.D.3. is parallel to ACGME Institutional Requirement II.E.2., which states, “Faculty members

and residents/fellows must have ready access to electronic medical literature databases and

specialty-/subspecialty-specific and other appropriate full-text reference material in print or

electronic format.”

Rev

iew Committee members are aware that the availability of a computer or mobile device with

internet access alone may provide access to a wide range of relevant reference material. Many

Sponsoring Institutions and programs purchase subscriptions to information resources and

services to supplement open access materials. As with other programmatic resources,

interpretation of the requirement may depend on unique circumstances of participating sites,

programs, faculty members, and residents. Residents and faculty members may provide

valuable input to Sponsoring Institutions and programs regarding the adequacy of available

medical literature resources.

©2024 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)

29

COMMON PROGRAM REQUIREMENTS

I.E. Other Learners and Health Care Personnel

The presence of other learners and other health care personnel, including,

but not limited to residents from other programs, subspecialty fellows, and

advanced practice providers, must not negatively impact the appointed

residents’ education.

(Core)

[The Review Committee may further specify]

Background and Intent: The clinical learning environment has become increasingly

complex and often includes care providers, students, and post-graduate residents and

fellows from multiple disciplines. The presence of these practitioners and their

learners enriches the learning environment. Programs have a responsibility to monitor

the learning environment to ensure that residents’ education is not compromised by

the presence of other providers and learners.

©2024 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)

30

GUIDANCE

Although other learners and other health care personnel can, and frequently do, enhance

resident education, there are certainly circumstances in which they negatively impact that

process. Examples include:

• interference of a subspecialty fellow or another care provider in the communication

between a faculty member and the resident (or resident team) in such a manner that the

resident does not gain the educational benefit of direct communication with the faculty

member;

• a fellow repeatedly performing procedures in which the resident is expected to develop

competence when there is a limited pool of procedures available;

• too many learners for the amount of educational experience or excessive rotators (e.g.,

medical students, residents from other specialties, advanced practice provider students);

• lack of opportunity for peer teaching (e.g., senior resident to junior resident, PGY-1 to

medical student); and

• certified registered nurse anesthetists (CRNAs) or CRNA students interfering with

residents performing and gaining competence in certain procedures.

Situations of this type frequently involve a degree of intra- or inter-departmental disagreement

on educational responsibilities and priorities. In the case of other health care personnel, they

may also impact decisions made by the administration of the clinical site. The designated

institutional official and Graduate Medical Education Committee (GMEC) may be very helpful in

supporting the program(s) and in arriving at equitable and mutually beneficial solutions.

The ACGME monitors compliance with Common Program Requirement I.E. in various ways,

including:

• questions answered by program leadership as part of an application or during the

Accreditation Data System (ADS) Annual Update;

• questions answered by residents and faculty members as part of the annual

Resident/Fellow and Faculty Surveys; and

• questions asked by the Accreditation Field Staff during site visits of the program at

various stages of accreditation.

The Resident/Fellow and Faculty Surveys include several questions that address the Program

Requirements in section I.D. The ACGME has prepared two documents, a Resident/Fellow

Survey-Common Program Requirements Crosswalk and a Faculty Survey-Common Program

Requirements Crosswalk, to provide additional information for programs on the key areas

addressed by the survey questions and how they map to the ACGME Common Program

Requirements. These documents can be found at

https://www.acgme.org/data-systems-

technical-support/resident-fellow-and-faculty-surveys/.

Programs are encouraged to monitor any concerns identified in the Resident/Fellow Survey and

address them proactively in the major changes section in ADS as part of their ADS Annual

Update or in preparation for a site visit.

©2024 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)

31

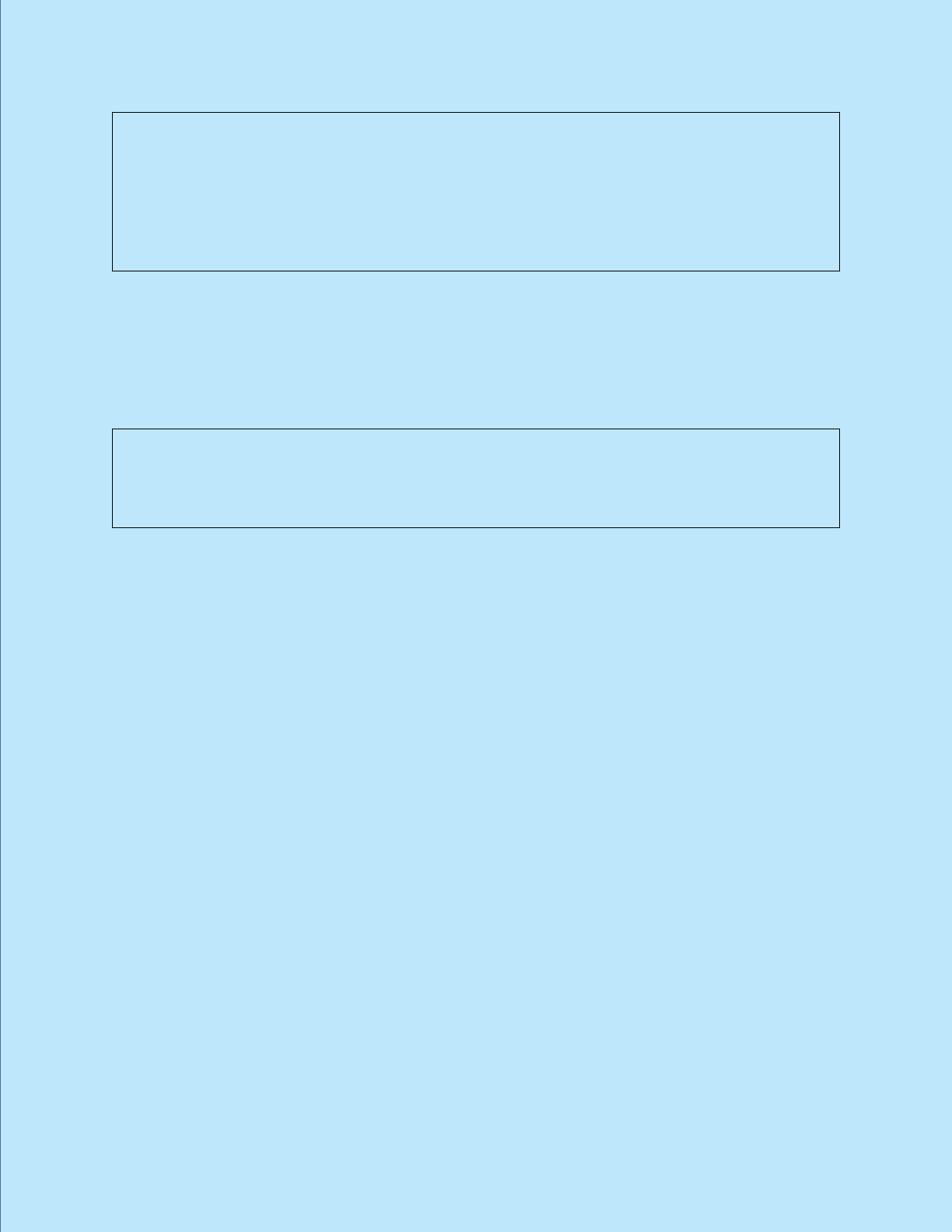

ADS screenshot: presence of other learners

The question below is part of the program ADS Annual Update Questionnaire.

©2024 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)

32

COMMON PROGRAM REQUIREMENTS

II. Personnel

II.A. Program Director

II.A.1. There must be one faculty member appointed as program director

with authority and accountability for the overall program, including

compliance with all applicable program requirements.

(Core)

.

II.A.1.a) The Sponsoring Institution’s GMEC must approve a change in

program director and must verify the program director’s

licensure and clinical appointment.

(Core)

II.A.1.a).(1) Final approval of the program director resides with the

Review Committee.

(Core)

[For specialties that require Review Committee

approval of the program director, the Review

Committee may further specify.

This requirement will be deleted for those specialties

that do not require Review Committee approval of the

program director.]

Background and Intent: While the ACGME recognizes the value of input from numerous

individuals in the management of a residency, a single individual must be designated as

program director and have overall responsibility for the program. The program

director’s nomination is reviewed and approved by the GMEC.

©2024 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)

33

GUIDANCE

II.A.1. One faculty member must be appointed as program director with authority

and accountability for the overall program.

This requirement specifies that each program must have one faculty member appointed as

program director. The program director is responsible for all aspects of the program and is

accountable for compliance with all applicable program requirements. For new programs, the

program director is identified in the Accreditation Data System (ADS) by the designated

institutional official (DIO). For existing programs, the program director is already designated and

appears first on the faculty roster.

II.A.1.a) The Graduate Medical Education Committee (GMEC) must approve a

program director change and verify the program director’s licensure and clinical

appointment.

A new program director can be designated for a program at any time through a program director

change request initiated by the DIO in ADS. For appointment of a new program director, the

GMEC must verify that the program director meets the qualifications outlined in Common

Program Requirement II.A.3. as well as verify that the program director has an active medical

license and a current clinical appointment and privileges before approving the change.

Following GMEC approval, the DIO will enter the recommendation into ADS via a new program

director request.

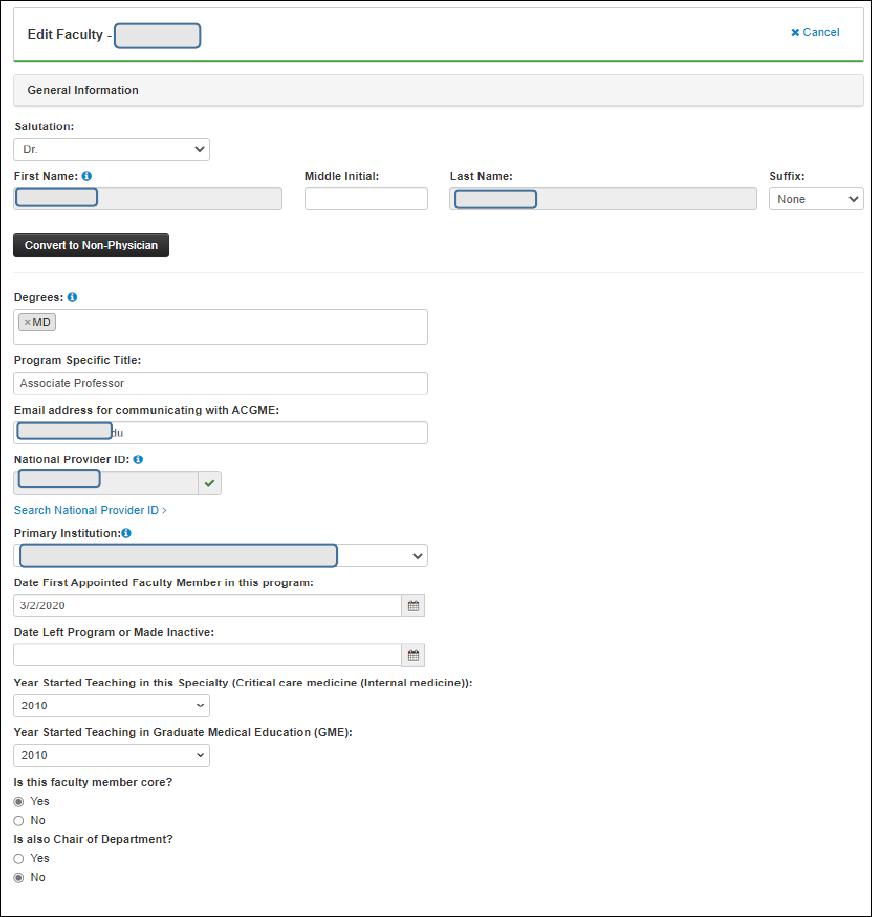

ADS steps and screenshots for initiating a new program director request:

The DIO must log into the Sponsoring Institution’s ADS account and complete the following

steps:

1. Select the Sponsored Programs tab and locate the program for which the program

director will change.

2. On the Program tab, select New Program Director.

3. Read the instructions carefully and select one of two options: Choose Program Faculty

or Search/Add New Person.

4. The DIO must complete two key sections: DIO questions and Director Profile

Information, including the rationale for the change. (See accompanying screenshots

which follow on the next page.)

©2024 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)

34

5. When the DIO submits the change, the old program director’s ADS access will

be immediately disabled and the new program director will receive an email

notification with the username and password (if new to ADS) and a notification

to review the change. The new contact information is immediately reflected in ADS

and on the public ACGME website.

©2024 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)

35

6. Once the new program director logs into ADS, the change request will be

available on the Overview tab toward the bottom of the page for review, completion

of any missing information, and submission. The program director change is not

complete until submitted by the new program director.

NOTE: The new program director or a designee must complete all required fields on

both the “Profile and Certifications” and “CV” tabs associated with the request.

Fields that require information or updates will be marked in red. This action will reduce

the need for ACGME staff members to seek updated information from programs and will

ensure timely review and approval by Review Committees.

7. Once the new program director submits the completed request, an email notification will

be generated in ADS to the ACGME, the DIO, and the institutional coordinator(s).

8. Rev

iew Committee staff members will reach out to programs with questions or requests

for additional information as needed if the new program director change request is

incomplete. Programs will be notified through ADS if a request is denied.

II.A.1.a).(1). Final approval of the program director resides with the Review Committee.

This requirement is included in the specialty Program Requirements only if the Review

Committee with oversight for a particular specialty has elected to establish the approval of

program director changes by the Review Committee as one of its processes. Not all Review

Committees or specialties/subspecialties have the same processes for reviewing program

director changes. Programs should review the resources on the applicable specialty section of

the website for more information, and can contact Review Committee staff members to verify

the program director change process for their specialty.

©2024 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)

36

COMMON PROGRAM REQUIREMENTS

II. Personnel

II.A. Program Director

II.A.1. There must be one faculty member appointed as program director

with authority and accountability for the overall program, including

compliance with all applicable program requirements.

(Core)

II.A.1.b) The program must demonstrate retention of the program

director for a length of time adequate to maintain continuity

of leadership and program stability.

(Core)

[The Review Committee may further specify]

Background and Intent: The success of residency programs is generally enhanced by

continuity in the program director position. The professional activities required of a

program director are unique and complex and take time to master. All programs are

encouraged to undertake succession planning to facilitate program stability when

there is necessary turnover in the program director position.

©2024 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)

37

GUIDANCE

II.A.1.b) Program director retention

The program director has many important responsibilities in a residency program. It can take

years for individuals to understand and reach a level of expertise in the role and develop

effective working relationships with all the individuals they must interact, including the

designated institutional official, program faculty members, faculty members and leaders in

related educational programs, administrators at the clinical sites to which residents rotate,

community leaders, and others. For these reasons, continuity in the program director role is

critical to ensure and maintain program stability and it is often associated with success of the

program.

[The Review Committee may further specify]

Common Program Requirement II.A.1.b) allows specialties to further specify. Currently, only a

few specialties have added a requirement that further specifies the minimum amount of time a

program director should serve in their role. To review the specialty-specific Program

Requirements:

1. Go to https://www.acgme.org/specialties/.

2. Select the applicable specialty.

3. Select “Program Requirements and FAQs and Applications” at the top of the specialty

section.

4. Select the specialty Program Requirements currently in effect.

The Background and Intent associated with this requirement encourages programs “to

undertake succession planning to facilitate program stability when there is necessary turnover in

the program director position.” While having a formal succession planning process at the

program or Sponsoring Institution level would be ideal, there are many ways programs can think

about succession planning. In larger programs, having one or more assistant/associate program

directors may be a good option for ensuring continuity of leadership in the program in case of a

program director change. In other cases, having a faculty mentoring process to identify faculty

members with an interest in a graduate medical education leadership career path and

supporting them in achieving various leadership competencies would also be a way to develop

talent for a program director or assistant/associate program director role.

©2024 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)

38

COMMON PROGRAM REQUIREMENTS

II.A. Program Director

II.A.2. The program director and, as applicable, the program’s leadership

team, must be provided with support adequate for administration of

the program based upon its size and configuration.

(Core)

[The Review Committee must further specify minimum dedicated

time for program administration and will determine whether

program leadership refers to the program director or both the

program director and associate/assistant program director(s).]

Background and Intent: To achieve successful graduate medical education, individuals

serving as education and administrative leaders of residency programs, as well as

those significantly engaged in the education, supervision, evaluation, and mentoring

of residents, must have sufficient dedicated professional time to perform the vital

activities required to sustain an accredited program.

The ultimate outcome of graduate medical education is excellence in resident

education and patient care.

The program director and, as applicable, the program leadership team, devote a

portion of their professional effort to the oversight and management of the residency

program, as defined in II.A.4.-II.A.4.a).(16). Both provision of support for the time

required for the leadership effort and flexibility regarding how this support is provided

are important. Programs, in partnership with their Sponsoring Institutions, may

provide support for this time in a variety of ways. Examples of support may include,

but are not limited to, salary support, supplemental compensation, educational value

units, or relief of time from other professional duties.

Program directors and, as applicable, members of the program leadership team who

are new to the role, may need to devote additional time to program oversight and

management initially as they learn and become proficient in administering the

program. It is suggested that during this initial period the support described above be

increased as needed.

In addition, it is important to remember that the dedicated time and support

requirement for ACGME activities is a minimum, recognizing that, depending on the

unique needs of the program, additional support may be warranted. The need to

ensure adequate resources, including adequate support and dedicated time for the

program director is also addressed in Institutional Requirement II.B.1. The amount of

support and dedicated time needed for individual programs will vary based on a

number of factors and may exceed the minimum specified in the applicable specialty

specific program requirements. It is expected that the Sponsoring Institution, in

partnership with its accredited programs, will ensure support for program directors,

core faculty members, and program coordinators to fulfill their program

responsibilities effectively.

©2024 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)

39

GUIDANCE

II.A.2. The program director and, as applicable, the program’s leadership team,

must be provided with support adequate for administration of the program based

upon its size and configuration.

The Background and Intent associated with this requirement further explains the rationale,

provides various examples of what may constitute program director support, and identifies

instances in which minimum support may need to be increased.

It is important to note that Review Committees consider approved resident complement rather

than filled resident complement when assessing program director or program leadership support

for administration of the program.

This requirement is closely linked to Institutional Requirements II.B.-II.B.4

. A Sponsoring

Institution is not necessarily the entity that provides compensation directly to a program director,

and, in many cases, a program director’s employer is not the Sponsoring Institution. However,

each accredited Sponsoring Institution is accountable to the ACGME’s Institutional Review

Committee for ensuring that program directors receive support and dedicated time in substantial

compliance with this requirement.

[The Review Committee must further specify minimum dedicated time for

program administration and will determine whether program leadership refers to

the program director or both the program director and associate/assistant

program director(s).]

Since Review Committees must specify minimum dedicated time for the program director or

program leadership, programs must review the specialty-specific Program Requirements:

1. Go to https://www.acgme.org/specialties/.

2. Select the applicable specialty.

3. Select “Program Requirements and FAQs and Applications” at the top of specialty

section.

4. Select the specialty Program Requirements currently in effect.

The Program Leadership Dedicated Time

summary document included as an institutional

resource on the ACGME website also provides a snapshot of program director dedicated time

and support across all ACGME-accredited specialties and subspecialties.

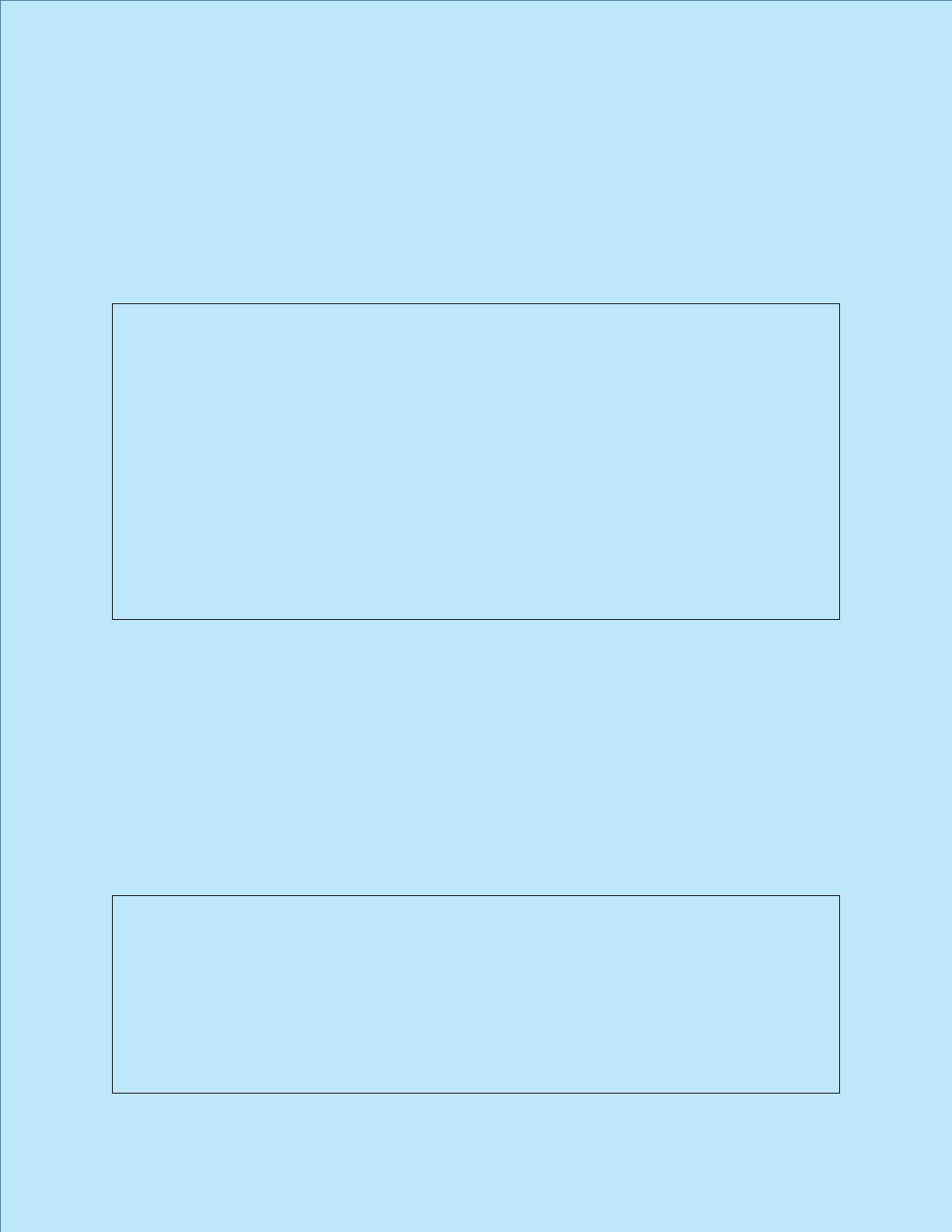

Accr

editation Data System (ADS) screenshot: program director support

The program director must answer or update the following questions as part of the ADS Annual

Update regarding support adequate for the administration of the program based on its size and

configuration. Programs are strongly encouraged to verify the specialty-specific Program

Requirements each year to ensure at least the minimum required level of support is provided.

(See accompanying screenshot which follows on the next page.)

©2024 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)

40

©2024 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)

41

COMMON PROGRAM REQUIREMENTS

II.A.3. Qualifications of the program director:

II.A.3.a) must include specialty expertise and at least three years of

documented educational and/or administrative experience, or

qualifications acceptable to the Review Committee;

(Core)

Background and Intent: Leading a program requires knowledge and skills that are

established during residency and subsequently further developed. The time period

from completion of residency until assuming the role of program director allows the

individual to cultivate leadership abilities while becoming professionally established.

The three-year period is intended for the individual's professional maturation.

The broad allowance for educational and/or administrative experience recognizes that

strong leaders arise through diverse pathways. These areas of expertise are important

when identifying and appointing a program director. The choice of a program director

should be informed by the mission of the program and the needs of the community.

In certain circumstances, the program and Sponsoring Institution may propose and the

Review Committee may accept a candidate for program director who fulfills these

goals but does not meet the three-year minimum.

II.A.3.b) must include current certification in the specialty for which

they are the program director by the American Board of _____

or by the American Osteopathic Board of _____, or specialty

qualifications that are acceptable to the Review Committee;

and,

(Core)

[The Review Committee may further specify acceptable

specialty qualifications or that only ABMS and AOA

certification will be considered acceptable]

II.A.3.c) must include ongoing clinical activity.

(Core)

Background and Intent: A program director is a role model for faculty members and

residents. The program director must participate in clinical activity consistent with the

specialty. This activity will allow the program director to role model the Core

Competencies for the faculty members and residents.

[The Review Committee may further specify additional program director

qualifications]

©2024 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)

42

GUIDANCE

II.A.3.a) Specialty expertise and at least three years of documented educational

and/or administrative experience, or qualifications acceptable to the Review

Committee.

The Background and Intent that follows this requirement helps explain the rationale behind the

requirement. Graduate medical education leaders require knowledge and skills that are

established during residency and must be subsequently further developed and cultivated over a

minimum of three years as an individual becomes professionally established. This requirement

also broadly allows for educational and/or administrative experience, recognizing that strong

leaders arise through diverse pathways. Lastly, the requirement acknowledges that the mission

of the program and the needs of its community should inform the selection of a program

director.

The Background and Intent also allows for potential exceptions, in certain circumstances, to the

three-year minimum educational or administrative experience requirement. The program and

Sponsoring Institution may propose, and the Review Committee may accept, a candidate for

program director who fulfills all other qualification requirements but does not meet the three-year

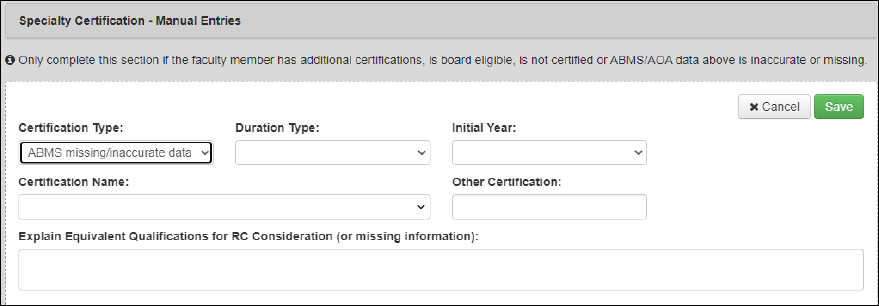

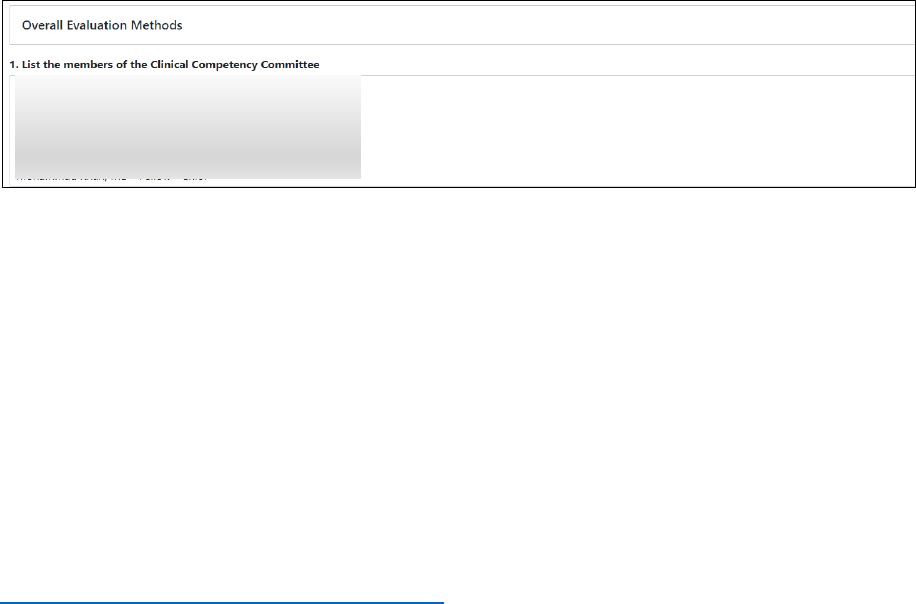

minimum.