Xavier University of Louisiana Xavier University of Louisiana

XULA Digital Commons XULA Digital Commons

Electronic Thesis and Dissertation

5-2020

A Causal Comparative Analysis of the Academic Self-E;cacy of A Causal Comparative Analysis of the Academic Self-E;cacy of

Black Male High School Students taught by a Black or White Male Black Male High School Students taught by a Black or White Male

Teacher. Teacher.

Joseph Jones Jr.

XXavier University of Louisiana

Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.xula.edu/etd

Part of the Educational Administration and Supervision Commons, Educational Assessment,

Evaluation, and Research Commons, and the Educational Psychology Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Jones, Joseph Jr., "A Causal Comparative Analysis of the Academic Self-E;cacy of Black Male High

School Students taught by a Black or White Male Teacher." (2020).

Electronic Thesis and Dissertation

. 17.

https://digitalcommons.xula.edu/etd/17

This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by XULA Digital Commons. It has been accepted for

inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation by an authorized administrator of XULA Digital Commons. For more

information, please contact [email protected].

A CAUSAL COMPARITIVE ANALYSIS OF THE ACADEMIC SELF-EFFICACY OF

BLACK MALE HIGH SCHOOL STUDENTS TAUGHT BY A BLACK OR WHITE MALE

TEACHER

By

JOSEPH JONES JR.

A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the

requirements for the degree of

DOCTOR OF EDUCATION

XAVIER UNIVERSITY OF LOUISIANA

Division of Education and Counseling

MAY 2020

ii

© Copyright by JOSEPH JONES JR., 2020

All Rights Reserved

iv

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

I would like to thank God, for seeing me through this entire process. If it were not for him, there

is no way I would have been able to do this work. Secondly, I would like to thank my parents,

Joseph Jones Sr. and Stephanie Jones. It is because of you two that I am driven to this work. You

both pushed and made me believe that anything is possible, and it is because of that, I was able

to embark on this journey. To my sister, my confidant, my love, my heart, and my soul—Thank

You. There is no me, without you. To my Ridgegang family, thank you for taking me in at such a

vulnerable time and allowing me to focus strictly on this work, I appreciate and love you all so

much. To my KIPP New Orleans family, thank you for always supporting me and allowing me to

do this work. To my principal, Towana, I love you so much. Words cannot express my gratitude.

To my soulmate and friend Brandi Michelle, there’s been countless nights where you allowed me

to just vent to you and you have always motivated me to do more, Thank you. Thank you to

David and Rhonda Lastie who truly believed in me as a teenager. If it weren’t for you two and

your generosity, I would not be here. To my sisters, brothers and cohort members, (Tamara,

Joey, Kimmie, Winston, Nick, Darren, Brantley, Meka, Amber, Dr. Derousselle, Dr. Parker and

Dr. Jones)—Thank you guys for being a shoulder whenever I needed you. To my committee

members, Dr. Perkins, thank you for always pushing me and going over and beyond to ensure

my work is the best. Dr. David Robinson-Morris, you have no idea how much respect and

admiration I have for you! Thank you for both pushing and believing in me. Dr. Signal, since day

one, you accepted nothing but the best from me and for that I am extremely thankful. Lastly, to

my chair, Dr. Akbar. You are truly God sent. You’ve always believed in me when I didn’t

believe in myself and for that I am grateful. There is no way I could have made it through this

journey without you and for that I am forever grateful to you.

v

A CAUSAL COMPARITIVE ANALYS IS OF THE ACADEMIC SELF-EFFICACY OF

BLACK MALE HIGH SCHOOL STUDENTS TAUGHT BY A BLACK OR WHITE MALE

TEACHER

by Joseph Jones Jr., Ed.D

Xavier University of Louisiana

May 2020

Chair: Renée Akbar

Abstract

The aim of this study was to determine if there was a difference in the academic-self

efficacy among Black male students taught by a Black male teacher compared to the academic

self-efficacy of Black male students that are taught by a White male teacher. Academically,

Black male students lag behind their peers in academic achievement indicators such as grade

point average, standardized test scores, and high school graduation rates (Schott Report, 2015).

Existing literature regarding Black male academic achievement focuses on exploring the

academic achievement gap that exists, but little to no research investigates how to close that gap.

Using Albert Bandura’s (1977) academic self-efficacy theory as a theoretical framework, this

study investigated whether or not Black male teachers have an impact on the academic self-

efficacy of Black male students by comparing the academic self-efficacy of Black male students

taught by a Black male teacher compared to the academic self-efficacy of Black male students

taught by a White male teacher.

vi

The study was guided by the following research question:

Is there a difference in the academic self-efficacy of Black male students taught by a Black male

teacher compared to the academic self-efficacy of Black male students taught by a White male

teacher.

To answer the question, a quantitative causal comparative research study was employed

using an adapted Academic Self Efficacy Scale (Gafor & Ashraf, 2006). Findings resulting from

this study is significant, as it aims to serve as a platform for future research on methods to close

the gap in academic achievement for Black male students.

vii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENT................................................................................................................ iv

Abstract ........................................................................................................................................... v

List of Tables .................................................................................................................................. x

CHAPTER ONE ............................................................................................................................. 1

Problem Statement ...................................................................................................................... 3

Purpose of Study ......................................................................................................................... 4

Research Question and Hypotheses ............................................................................................ 4

Research Question (RQ1): .......................................................................................................... 5

Hypothesis: ................................................................................................................................. 5

Significance of Study .................................................................................................................. 6

Overview of Methodology .......................................................................................................... 6

Delimitations/Assumptions ......................................................................................................... 7

Definition of Terms..................................................................................................................... 7

Stereotype Threat Theory – A situational predicament where people feel themselves to be at

risk of confirming negative stereotypes ...................................................................................... 8

CHAPTER TWO ............................................................................................................................ 9

LITERATURE REVIEW ............................................................................................................... 9

Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 9

viii

Black Male Students and the Achievement Gap......................................................................... 9

Stereotype Threat ...................................................................................................................... 12

Black Male Teachers................................................................................................................. 14

Self-Efficacy ............................................................................................................................. 17

Academic Self-Efficacy ............................................................................................................ 18

Summary ................................................................................................................................... 20

CHAPTER THREE ...................................................................................................................... 22

METHODOLOGY ....................................................................................................................... 22

Introduction/Overview of Study/Organization of Chapter ....................................................... 22

Rationale for Research Design and Methodology .................................................................... 22

Research Approach ................................................................................................................... 23

Research Question (RQ1): ........................................................................................................ 24

Hypothesis................................................................................................................................. 24

Population/Sampling ................................................................................................................. 24

Instrumentation ......................................................................................................................... 25

Data Collection and Procedures ................................................................................................ 26

Data Analysis Procedures ......................................................................................................... 27

Conclusion ................................................................................................................................ 27

CHAPTER FOUR ......................................................................................................................... 28

FINDINGS .................................................................................................................................... 28

ix

Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 28

Description of Site(s)/Population ........................................................................................... 29

Statistical Analysis: Research Question #1............................................................................... 30

Conclusion ................................................................................................................................ 47

CHAPTER FIVE .......................................................................................................................... 49

Overview of the study ............................................................................................................... 49

Discussion and Analysis of Findings ........................................................................................ 51

Difference in Academic Self-Efficacy ...................................................................................... 52

Ability to Accomplish a Challenging Task ............................................................................... 54

Years of Experience .................................................................................................................. 54

Limitations ................................................................................................................................ 57

Recommendations for Policy, Practice, & Future Research .................................................. 57

Implications for Policy, Practice, and Future Research ......................................................... 59

Conclusion ................................................................................................................................ 60

References ................................................................................................................................... 633

APPENDIX A. ............................................................................................................................ 755

x

List of Tables

Table 1 Demographics of Sample Population .............................................................................. 30

Table 2 One Way ANOVA Mean Results ...................................................................................... 31

Table 3. One Way ANOVA Results for Question Number 39 ....................................................... 32

Table 4 One Way ANOVA Results for Questions 1-40 ................................................................. 33

Table 5 Descriptives ..................................................................................................................... 35

Table 6 Reading = 4.3 .................................................................................................................. 37

Table 7 Learning Process = 4.472 ............................................................................................... 37

Table 8 Comprehension= 4.06 ..................................................................................................... 38

Table 9 Memory = 3.60 ................................................................................................................ 39

Table 10 Peer Relationship = 4.1 ................................................................................................. 39

Table 11 Utilization of Research = 3.5 ......................................................................................... 40

Table 12 Curricular Activities = 3.875 ........................................................................................ 41

Table 13 Time Management = 3.318 ............................................................................................ 42

Table 14 Teacher Student Relationship = 4.13 ............................................................................ 42

Table 15 Goal Orientation = 4.13 ................................................................................................ 43

Table 16 Adjustments = 3.76 ........................................................................................................ 44

Table 17 Examination = 3.64 ....................................................................................................... 46

Table 18 One Way ANOCOVA…………………………………………………………………..57

1

CHAPTER ONE

INTRODUCTION

More than 50 years after the landmark court case Brown v. Board of Education (1954),

Black students, specifically Black males, are more likely to be suspended, least likely to be

enrolled in gifted and talented classes and are not graduating high school at the same rate as their

peers (Lewis, 2011; McMillian, 2003; Rhoden, 2017). Literature on Black male students (Brown

and Donner, 2011) illuminate the dismay of structural systems within urban communities and the

United States public education systems that contribute to academic barriers that Black male

students face. It is because of these systematic barriers that often Black male students are

reported as academically falling behind their peers (Nogguera, 2009). According to the Schott

Report (2015), Black male students had a graduation rate of 59% while their White male

counterparts have a graduation rate of 80%. The disparity between Black and White male

students’ graduation rate is one of just many indicators that contribute to what theorists call the

achievement gap. Boykin, Tyler, Watkins-Lewis, and Kizzie (2006) describe the achievement

gap as the difference in test scores, grades, and high school graduation rates between groups of

students. If not closed, the achievement gap has huge implications on the socio-economic

futures of Black male students (McKinsey & Company, 2009).

There has been a large body of research (Grissmer, Flanagan & Williamson, 1998; Chubb

& Lawless, 2002) that discusses ways in which school districts can close the achievement gap.

Some of these strategies include smaller class sizes, charter schools, and school vouchers.

However, there has been little to no progress in minimizing the gap for disadvantaged students

(Blank, 2011). School districts have enacted several mandates such as No Child Left Behind

(2001) and Every Student Succeeds Act (2015) in hopes of providing a fair and equitable

2

education to all students. However, despite these mandates, Black male students are still

graduating high school at lower rates than their White counterparts, have lower grade point

averages, and are more likely to be suspended (Schott Foundation for Public Education, 2015).

Researchers have also begun exploring student-centered approaches, as well as

investigating the socio-psychological milieu that Black males face at their schools. For example,

research from King (2016) and DeFreitas and Bravo (2012) discusses the student-centered

positive relationship that academic self-efficacy has on academic performance. In their meta-

analysis, researchers Robbins, Lauver, Le, Davis, and Langley (2004) found that academic self-

efficacy and academic performance in college were related. Steele and Aronson (1995) believe

that poor educational outcomes for Black males are rooted in psychological barriers such as

stereotype threat. Stereotype threat consists of the sociological, racial, gender, and educational

intersections of being Black, Male, and the failure to support their needs for academic self-

efficacy. (Pennington, Heim, Levy, & Larkin, 2016)

As another approach to improve Black male academic achievement, several researchers

have explored the potential of positive impacts that Black male teachers can have on Black male

students (Blake et al., 2016; Irvine, 2003; Pabon et al., 2011). Currently, Black male teachers

make up only 2% of the teaching population (Milner, 2016). School districts across the country

struggle to recruit and retain Black male teachers (Irvine, 2003). One factor that influences the

low recruitment and retention of Black male teachers are the number of Black male students that

enter into college. Brown and Butty (1999) noted that the number of African American males

who go into teaching is influenced by the number of African American males who attend

college, which is influenced by the number of high school graduates.

3

Gordon (2000) suggested that Black students in college do not believe teaching is a

lucrative or attractive career choice. Research in education also suggests that Black males who

enter the teaching force also struggle to pass two of the American teacher certification exams,

such as the Praxis I and Praxis II (Albers, 2002). In a study that explored the performance and

passing rate difference between Black and prospective teachers of other ethnicities, research

revealed that Black first-time-test takers had a significantly lower pass rate (Nettles, Scatton,

Steinberg, & Tyler, 2011).

For those that are successful in passing the Praxis exam, their presence in the classroom

is extremely impactful. Milner (2010) found that Black male teachers are often role models for

Black male students. Black male teachers also develop curriculum and instructional practices

that align with the needs and interest of Black male students. Further, they develop and

implement equitable disciplinary practices in their approach rather than the standard approach

that has led to the massive suspension and expulsion of Black male students (Milner, 2010).

Problem Statement

Due to the structural injustices within the public-school system that has led to Black male

students being expelled and suspended at higher rates than their peers (Milner, 2010), there is a

gap in academic achievement between Black male students and their academic peers (Ford &

Moore, 2013). While school districts have attempted to close the academic achievement gap,

Black male students still lag academically behind their classmates (Schott Foundation for Public

Education, 2015). Research conducted by Reid (2013) discussed the positive impact that self-

efficacy has on Black male students. Additionally, recent research (Lewis, 2011; Pabon et al.,

2011) illuminated the positive impact that Black male teachers have on Black male students in

academic settings. However, little to no research discusses the academic impact that Black male

4

teachers have on Black male students. It was the intention of this study to determine whether or

not there is a difference in Black male student’s academic self-efficacy if they are taught by a

Black male teacher when compared to a White male teacher. Academically and socially, Black

male teachers share an understanding of the unique experiences and challenges that Black male

students experience in academic settings (Pabon et al., 2011). However, despite the positive

impact that Black male teachers have on Black male students, school districts are not recruiting

and retaining Black male teachers (Lewis, 2006).

Purpose of Study

The purpose of this study was to determine if there is a difference in the academic-self

efficacy of Black male students taught by a Black male teacher compared to the academic self-

efficacy of Black male students when taught by a White male teacher. One factor that affect the

achievement gap for Black male students is their academic self-efficacy. Bandura (1997) defines

academic self-efficacy as a person’s belief in whether or not he or she can perform an academic

task. Bandura (1997) suggested in his research that a student’s self-efficacy will affect their

academic performance. In his examination of high achieving Black Male students at

predominantly white institutions, King (2016) points out that self-efficacy was vital in their

academic achievement. Using Bandura’s Self -Efficacy Theory as the lens through which to

explore the academic relationship between Black male students and black male teachers, the aim

of this study is to determine if there is a difference in the academic self-efficacy for Black male

students taught by a Black male teacher compared to the academic self-efficacy of Black male

students when taught by a White male teacher.

Research Question and Hypotheses

5

This study set out to understand whether or not Black male teachers have an impact of Black

male student’s academic self-efficacy. Specifically, the research will determine if there is a

difference in the academic self-efficacy of Black male students when taught by a Black male

teacher compared to Black male students taught by a White male teacher. To this end, the

research question and hypothesis are as follows:

Research Question (RQ1):

1.) Is there a difference in the academic self-efficacy of Black male students when taught by a

Black male teacher compared to the academic self-efficacy of Black male students taught by a

White male teacher?

Hypothesis:

H1A: Black male students taught by a Black male teacher have a higher mean score of academic

self-efficacy compared to Black male students taught by a White male teacher.

The research question was answered through a quantitative research study that utilized

Gafor and Ashraf’s (2006) adapted Academic Self-Efficacy Scale to measure Black male

students’ academic self-efficacy. The results of this test, which is a psychometric test that

measures self-efficacy on cognitive processes, was used to answer a question about Black male

student’s academic self-efficacy. Second, to determine the difference in Black male students’

academic self-efficacy, this study employed a causal comparative research design to compare the

differences in academic self-efficacy of Black male students taught by a Black male teacher to

Black male students who are taught by a White male teacher. The results of the research

approach will be used to test the hypotheses posed in this study. Figure 1 reflects the

hypothesized mediating model. Solid lines represent positive relationships, dashed lines

represent negative relationships.

6

Figure 1 Mediation Model:

Significance of Study

This study provide insight into the relationship that Black male teachers have on Black

male students’ academic self-efficacy. Additionally, results from this research will help close the

gap in existing literature that examined the impact that Black male teachers have on Black male

students. While there is limited research on the positive impact that Black male teachers have on

Black male students (Graham & Erwin, 2011), this research focuses specifically on the

difference in Black male students’ academic self-efficacy when taught by a Black male teacher

compared to the academic self-efficacy of Black male students taught by a White male teacher.

Overview of Methodology

This study employed a sample of Black male high school seniors 18 years or older

currently enrolled in a high school mathematics class located in the Southeastern region of the

United States. Demographics questions included participants’ age, gender, race, and current

grade level. Academic self-efficacy was measured using an adapted form of Gafor and Ashraf’s

(2006) self-efficacy questionnaire.

Black male

teachers

Black male

student’s academic

self-efficacy

Black male

student’s academic

performance

White male

teachers

7

Research conducted by DeFreitas and Bravo (2012) and King (2016), the study’s

hypothesis is that Black male students have a higher mean score of academic self-efficacy when

taught by a Black male teacher compared to Black male students who are taught by a White male

teacher. To test the hypothesis, the researcher used a causal comparative research design.

Delimitations/Assumptions

One assumption in this study is that participants answered the survey questions

completely and honestly. There is also an assumption that teachers and students who identify as

male are cisgender males. Further, based on literature conducted by Bandura, 1993; Schunk,

1995; Pajares, 1996, there is an assumption that high academic self-efficacy leads to increased

academic achievement. White and Black refer to phenotypical designations with assumed

general cultural values and lived experiences.

Delimitation of this study is the age of the participants, their grade level, and the classes

that the students are enrolled in. This study surveyed 18-year-old senior high school students

enrolled in two mathematics classes in a public high school to determine the differences in Black

male student’s academic self-efficacy when taught by a Black male teacher to Black male

students who are taught by a White male teacher. With such a small sample size, results did not

fully identify the differences in academic self-efficacy. Additionally, participants of the study

were18-year-old seniors enrolled in schools in the Southeastern region of the United States.

Participants did not fully represent the entire Black male student population.

Definition of Terms

For this study, the following terms are defined:

Black Male Students – Students enrolled in High School aged 18 years or older that identify as

both Black and Male

8

White male teacher – A full time teacher who identifies as both White and Male.

Black male teacher– A full time teacher who identifies as both Black and Male.

Academic Self Efficacy – An individual’s belief that they can successfully attain a specific

academic task

Academic Achievement – A student’s success in reaching their educational outcomes. These

outcomes are typically represented by Grade Point Averages (GPA), standardized assessment

scores, and ability to graduate.

Achievement Gap – The gap in academic performance between groups of students

Cisgender – A designation that relates to a person whose personal identity and gender

corresponds to the sex they were given at birth.

Stereotype Threat Theory – A situational predicament where people feel themselves to be at risk

of confirming negative stereotypes

In Chapter One of this study, background information regarding the academic

achievement of Black Male students was introduced. Also included, is the purpose and

significance that this research will have on closing the achievement gap. Through Albert

Bandura’s (1977) Self-Efficacy Theoretical Framework, this study explored the impact that

Black male teachers have on the academic-self efficacy of Black male students. Outlined in this

chapter is the research question, proposed methodology, and definition of specific terms. Also

included are the assumptions, delimitations, and limitations of the study.

Chapter two will provide relevant literature to the study that focuses on Black male

students, Black male teachers, Stereotype Threat Theory, and Self-Efficacy Theory. Chapter

three will outline the methodological approach that will be used to explore the impact that Black

male teachers have on the academic self-efficacy of Black male students.

9

CHAPTER TWO

LITERATURE REVIEW

Introduction

There are studies that have been conducted that discuss the impact of the achievement

gap on Black male students (Ladson-Billings, 2006; Schott Foundation for Public Education,

2015). However, there is a gap in the literature regarding varying factors that have hindered

Black male students academic achievement and the impact that Black male teachers have on

Black male students’ academic achievement. This study focused on four major themes which

emerged throughout the literature. These themes are Black male students and the achievement

gap, the impact of stereotype threat on Black male students’ academic achievement, the impact

of Black male teachers on Black male students, and the impact that academic self-efficacy has on

academic achievement. While the literature presents these themes in varying contexts, this

research focused on their application as it relates to Black male student’s academic self-efficacy.

Black Male Students and the Achievement Gap

Literature on Black male achievement points to the many institutional barriers that impact

Black male academic achievement, such as stereotype threat, cultural incongruence, and the lack

of Black male teachers (Milner, 2010; Rai & Kumar, 2017; Steele &Aronson, 1995). Due to

these barriers, Black male students are graduating at lower rates than their peers, are more likely

to be suspended or expelled, and score lower than their counterparts on standardized tests (Schott

Foundation for Public Education, 2015). Black males make up 15.4% of the national K-12 public

school population (Kena et al., 2014), yet they are more likely to be referred for special

education services (Blanchett, 2006; Ford & Moore, 2013), and are more likely to be suspended

or expelled (Gordon, 2017). As a result, Black male students across the country are encountering

what is known as the achievement gap. The achievement gap is defined as the gap in academic

10

achievement between disadvantaged minority students and their White counterparts (Ladson-

Billings, 2006). According to the National Education Association, indicators of the achievement

gap are performance on standardized tests (ACT), outcome attainments (e.g., high school

diploma), and grades (National Education Association, 2012).

It has been estimated that the 2012-2013 Adjusted Cohort Graduation Rate (ACGR) for

Black male students was 59%. Comparatively, Latino males had an ACGR of 65% and White

males with an ACGR of 80% (Schott Foundation for Public Education, 2015). While there may

be several factors that affect the graduation gap between Black male students and their academic

counterparts, one of the most significant factors is the Black male suspension rate (Schott

Foundation for Public Education, 2015).

According to a report from National Center for Education Statistics, in the 2013-2014

school year, 17.6% of Black male students received out of school suspensions (Kena et al.,

2014). School suspensions are common discipline outcomes that aim to deter students from

exhibiting problem behaviors within the school setting. Black male suspensions were almost

twice the percentage of American/Indian/Alaska Native males (9.1%) and were more than twice

the percentage of White males (5%) (Kena et al., 2014). Noltemeyer, Ward, and Mcloughlin

(2015) found significant relationships between suspension rates and increases in student drop-out

rates. In an industry where 80% of the teaching workforce are White females, their conscious or

unconscious beliefs in negative stereotypes of Black male students has resulted in Black male

students being suspended/expelled at higher rates and referred to special education at higher rates

than their peers (Schott Foundation for Public Education, 2015).

When examining the impact of suspensions on academic performance, data shows

consequential effects of in-school and out-of-school suspension on student’s academic

11

performance (Noltemeyer et al., 2015). Chu and Ready (2018) tracked a group of students

throughout their high school career and revealed that suspended students were three times less

likely to pass math and English classes compared to semesters when they were not suspended.

For all students, out-of-school suspensions not only impacted their academic achievement but

also their ACFGR (Chu & Ready, 2018). This is a problem because this means that Black males

are not only failing to graduate from high school at rates that are similar to their peers, but they

are also leaving high school underprepared to meet the demands of college.

Another indicator that impacts the achievement gap for Black male students is their

academic performance on standardized tests, such as the American College Testing Exam

(ACT). The ACT is a standardized test that colleges use to measure students’ abilities and

college readiness in five areas: English, Math, Science, Reading, and Writing. While there’s little

to no data on Black male ACT scores, on the 2017 ACT, there was a five-point gap in ACT

scores for Black students (17.1) compared to their White counterparts (22.4) (The National

Center for Educational Statistics, 2017). Representation in advanced placement courses is also an

indicator of the academic achievement that may impact the achievement gap. Often, Black

students are assigned to lower-level classes and underrepresented in Advanced Placement (AP)

and gifted classes (Corra, Carter, & Carter, 2011). However, Black females are more likely to

enroll in and take AP examinations than their male counterparts and have higher levels of college

enrollment than Black male students (Corra et al., 2011). Often, AP classes serve as

“gatekeepers” that either enhance or limit opportunities for students. Black male students are

often ineligible to these classes that provide rigorous instruction and prepare high school students

for college (Corra et al., 2011).

12

According to Burdman (2000), “Students who are successful in AP and honors courses

are more likely to succeed in and graduate from college.” In 2016, the National Center for

Educational Statistics reported that 31% of black males between the ages of 18-24 years old were

enrolled in 2-4-year colleges or universities (Kena et al., 2016). However, Black men graduate

from four-year programs in six years at a rate of 33% and from two-year programs in four years

at a rate of 35%. On the other hand, White males graduate at a rate of 44% from four-year

programs (McFarland et al., 2018). Although there are several indicators that impact the

achievement gap, there are also factors that contribute to the gap as well. The difference between

Indicators and factors of the achievement gap is that indicators signify the state or level of the

achievement gap whereas factors are what have influenced the achievement gap. Stereotype

threat, Black male teachers, and academic self-efficacy are factors that may impacts on Back

Male students’ academic achievement. In this next section, a discussion of these factors will be

presented.

Stereotype Threat

One factor that also impacts the academic achievement of Black male students is

Stereotype Threat. Stereotype Threat Theory originates from research conducted by Steele and

Aronson (1995) which explains how negative academic stereotypes impact Black students in

college. The current stereotypes that are affecting Black males is the notion that they are

unintelligent and lazy (Johnson, 2008). According to Steele and Aronson (1995), Stereotype

Threat is the risk of confirming or being at risk of confirming negative stereotypes about one's

identity group. For Black male students, stereotype threat may have negative impacts on

academic achievement (Fischer, 2010; Steele, 1992, 1997). These stereotypes have strong

implications for Black male students, especially in college settings, as they may potentially

13

undermine the ability of Black male students to successfully matriculate and graduate with a

college degree. (Johnson-Ahorlu, 2013). This study examines if these same factors and effects

occur in high school Black male students. Stereotype Threat also has an effect on how Black

male students perform on standardized tests (Fischer, 2010). This same concept has been the

target of Black males throughout their school career.

In a study conducted by Aronson, Fried, and Good (2002), researchers investigated how

Stereotype Threat impacted the academic performance of Black undergraduate students. Results

revealed that Black college freshman and sophomores performed worse on standardized tests

when their race was made relevant or conspicuous by situational features. When race was not

emphasized, however, Black students performed equally or better than their counterparts

(Aronson et al., 2002).

Stereotype Threat hinders academic performance (Johnson-Ahorlu, 2013). According to

researchers “Students perform more poorly on academic tests when tested under stereotype

threatening conditions.” (Steele and Aronson, 1995). Steele, Spencer, and Aronson (2002)

believe that continuous exposure to stereotype threat can result in long-term disengagement.

Disengagement is the disinterest that happens when stereotype threat is activated. Continuous

disengagement results in disidentification in which individuals may devalue performance on

specific tasks (Hines, Rivadeneyra, & Zimmerman, 2014). Continued disidentification in any

task results in a holistic disbelief in a person’s ability to complete specific tasks. These findings

suggest that if Black male students are regularly threatened with the stereotype of being

academically inferior to their peers, ultimately, they will believe that they are, and their efforts

on academic tasks will decrease.

14

In support of the large body of research that examines the negative outcomes of

stereotype threat (Aronson, Fried, & Good, 2002; Steele, 1997; Osborne, 1999), there is also

research that explores methods to reduce stereotype threat. One method in particular involves

employing Black male teachers as role models for Black male students. According to Blanton,

Crocker, and Miller (2000), exposure to positive role models can improve academic

performance. “Thoughts about our group members whose performance is superior in a domain

can interfere with performance and providing role models demonstrating proficiency in a domain

can reduce stereotype threat effects.” (Blanton, Crocker & Miller, 2000). Along similar lines,

other research provides further support that providing role models that challenge stereotypic

assumptions can eliminate stereotype threat (McIntyreet al., 2003; McIntyre, et. al, 2005). For

Black male students, those role models are Black male teachers (Milner, 2010).

Role models are pivotal in the development of adolescents, especially minority students.

In a 2002 study conducted by Sirkel, results concluded that students with the same gender role

models at the beginning of the study performed better academically than students without a race

and gender matched role model. Additionally, research suggests that Black students who have

role models have higher educational aspirations, better grades, and higher persistence (Joyner,

2013, Smith, 2015).

Black Male Teachers

The representation of Black male teachers in the United States is practically nonexistent

(Milner, 2016). Black male teachers make up only 2% of the teaching population (Milner, 2016).

The lack of Black male teachers in the United States is important because studies have shown

that Black students who have been taught by just one black teacher in the 3

rd

– 5

th

grades lower

their chances of dropping out by 19 percent; for Black males it is 39% (Gershenson, Hart,

15

Constance, & Papageorge, 2017). Additionally, Black male teachers in the classroom are strong

disciplinarians who are able to create strong, culturally relevant environments in which black

students can excel (Irvine, 2003). Yet, research reveals that the number of Black male teachers

have not risen past 2% of the teaching population (Milner, 2016).

The percentage of Black male teachers has not always been low. According to the 1890

census, among Black teachers, 49% were male and 51% were women (Fultz, 1995). During the

mid-19

th

century, as the country’s public-school system emerged, so did the number of women

entering the teaching profession. However, during the 1940s, that number decreased drastically;

Black males made up 21% of the Black teaching population and Black women made up 79%

(Ingersoll, 2012). Little to no information is provided that explains causes for the decrease in

Black male teachers during this period. However, one plausible explanation is that Black males

were likely eager to join the robust industrial industry that flourished during Reconstruction

(Bristol, 2014), thus decreasing the number of Black male teachers. Additionally, after the

Brown (1954) Supreme Court ruling, schools across the United States were mandated to

desegregate, causing a large portion of the Black teaching population to lose their jobs

(Karpinski, 2004). Over 30,000 Black teachers and administrators lost their jobs (Fultz, 2004).

Furthermore, in the 1970s, the Black teaching population decreased drastically again due to the

new teacher-certification requirements that were imposed (Tillman, 2004). In summary, these

periods in which Black males were not retained or actively recruited into teaching has not only

contributed to the 21

st

century deficiency in Black male teachers but also brings attention to the

long-term recruitment of Black male teachers into the school systems.

Brown and Butty (1999) and Graham and Erwin (2011) discuss the positive impact that

Black male teachers have on students. According to Graham and Erwin (2011), Black male

16

teachers address problems that stem from cultural incongruence. Cultural incongruence is the

lack of cultural similarities between people in a relationship (Rai & Kumar, 2017). Tyler,

Boykin, Boelter, and Dillihunt, (2005) assert that cultural incongruence between Black students

and White teachers emerge when White teacher pedagogical and classroom management

practices are opposite of Black male students’ lives. For example, white teachers often interpret

the behaviors of Black males as defiant, disrespectful, and intimidating (Ferguson, 2005;

Monroe, 2005). This interpretation has led to unfair discipline policies that are more harsh for

Black male students compared to their White counterparts (Monroe, 2005; Skiba, 2001). Black

male teachers potentially address issues with cultural incongruence by providing a diverse

perspective that pushes culturally relevant and culturally responsive pedagogy in the classroom

(Tyler et al., 2005). Lynn (2006) contends that Black men see teaching as an opportunity to

correct social barriers that exist for Black students and teach in ways that attempt to end racial

inequality (Lynn, 2002). For Black male students, Black male teachers are often regarded as role

models and mentors (Milner, 2010). In their research, (Milner, 2016) discuss not only the

positive impact that Black male teachers have on Black male students but also the culturally

responsive pedagogy that they apply during instruction.

Culturally responsive pedagogy, allows teachers to build upon vantage points and

experiences of students and communities in the development of curriculum (Milner, 2016). It

emphasizes that teachers use students’ experiences to increase students opportunities to learn

(Ladson-Billings, 2009; Gay 2010). Gay conceptualizes culturally responsive pedagogy as

Using cultural knowledge, prior experiences, frames of reference, and performance styles

of ethnically diverse students to make learning encounters more relevant to and effective

for them. It teaches to and through the strengths of these students . . . [it] is the behavioral

expressions of knowledge, beliefs, and values that recognize the importance of racial and

cultural diversity in learning. (p. 31)

17

According to Milner (2013), culturally responsive pedagogy is validating and affirms the

knowledge of backgrounds, experiences, and ideas. Culturally responsive pedagogy is also

empowering and pushes students to excel academically and reach their full potential (Ladson-

Billings, 2009). In their study of Black male teacher’s use of culturally responsive pedagogy,

researchers (Milner, 2016) discovered that it both validated student’s experiences but also

empowered students to take on challenging tasks and become academically successful. While

culturally responsive pedagogy is one way Black male teachers impact Back student’s academic

success, the presence of Black males in teaching and leadership roles may also enhance Black

male students’ academic and social development, specifically their academic self-efficacy

(Styles, 2017).

Self-Efficacy

Self-Efficacy Theory was first proposed by Albert Bandura in 1977 as a unifying

behavior theory that would explain behavior change in relation to psychological interventions

and psychotherapy (Bandura, 1977). It is grounded in a larger theoretical framework, Social

Cognitive Theory (Pajares, 1996; Schunk, 199;). Social Cognitive Theory developed by Albert

Bandura, is a belief that human achievement is dependent upon factors such as environmental

conditions, behaviors, and personal beliefs and/or thoughts. Bandura (1993) defines self-efficacy

as “People’s beliefs about their capabilities to produce designated levels of performance that

exercise influence over events that affect their lives.” There is a belief that self-efficacy

determines how people feel and think about themselves. In relation to Black male student

achievement, there is a body of research that explores the impact of self-efficacy on black males’

academic achievement (Bandura, 1993; King, 2016).

18

Bandura (1997) proposes that self-efficacy is one of the most important determinants of

human behavior. Humans with a strong sense of self-efficacy attempt difficult tasks no matter

how hard those tasks may be. Adversely, humans with low self-efficacy avoid difficult tasks

(Bandura, 1994). According to Bandura (1994), individuals’ beliefs about their self-efficacy is

influenced by four main sources of influence: Performance attainments and failures, vicarious

performances, verbal persuasion, and imaginal performances.

Performance attainments and failures are individuals’ experiences with mastering a

specific skill. Continuous and successful experiences of mastering a skill lead to higher levels of

self-efficacy. However, avoiding a task would weaken it. Vicarious performance leads to higher

self-efficacy when individuals observe those similar to themselves perform and succeed at a task.

Similarly, verbal persuasion leads to higher self-efficacy when others encourage individuals to

perform a task. Through constructive feedback, verbal persuasion convinces individuals that they

are capable of performing a task. Lastly, physiological states relate to moods and emotions

influence individuals’ abilities. When individuals are nervous or highly stressed, they tend to

doubt themselves more and have lower self-efficacy. If individuals feel confident, they tend to

have a higher sense of self-efficacy. (Bandura, 1994). This study used Bandura’s (1977) Self-

Efficacy Theory as theoretical support for the causal comparative research design to determine

whether or not there is a difference in Black male student’s academic self-efficacy when taught

by a Black male teacher compared to Black male students taught by a White male teacher.

Academic Self-Efficacy

Academic self-efficacy is grounded in Bandura’s (1977) Self-Efficacy Theory. According

to Bandura (1997), academic self-efficacy refers to an individual’s belief that he or she can

achieve a specific academic goal. There has been a large body of research that explores how

19

academic self-efficacy impacts black male student’s academic success (Reid, 2013; Styles, 2017;

Williams, 2017). There has been extensive research suggesting that academic self-efficacy

relates to positive academic outcomes (Bandura, 1997; Pajares, 1996; Schunk, 1995). Academic

self-efficacy is regarded as a task orientated trait that may differ across academic domains

(Sharma & Nasa, 2014). Academic self-efficacy is regarded as a multidimensional construct that

is differentiated across multiple academic domains of functioning (Sharma & Nasa, 2014).

Linenbrink and Pintrick (2003) reported that academic self-efficacy is significantly associated

with students' learning, cognitive engagement, analytical thinking, academic commitment,

strategy use, persistence, susceptibility to negative emotions and achievement. In his research,

Bandura (1993): identifies indicators (or characteristics) of self -efficacy as they:

1. view problems as challenges to be mastered instead of threats and set goals to meet the

challenges, are committed to the academic goals they set, have task-diagnostic

orientation;

2. have a task-diagnostic orientation, which provides useful feedback to improve

performance, rather than a self-diagnostic orientation, which reinforces the student’s low

expectation about what he or she can accomplish;

3. view failures as a result of insufficient effort or knowledge, not as a deficiency of

aptitude; and

4. increase their efforts in cases of failure to achieve the goals they have set.

In his research, Schunk (1995) asserted that teachers play vital roles in instilling positive

perceptions of academic self-efficacy through goal setting, strategy training, modeling, and

feedback (Schunk, 1995). According to Bandura (1977), people exhibit higher self-efficacy when

they see someone similar to them performing a task. Based on this logic, it is reasonable to infer

20

that Black male students are able to observe Black male teachers perform academic tasks, thus

increasing their academic self-efficacy. The relationship between Black male teachers and Black

male students is extremely important because both groups experience the intersectionality of

what it means to be Black and male in an educational landscape where Black male teachers

represent 2% of the teaching population (Styles, 2017). In his research on how self-efficacy

impacts Black male undergraduate students, Noble’s (2011) findings concluded that vicarious

experiences had the greatest impact on Black males’ achievement in mathematics. Additionally,

according to Bandura (1997) children who are still developing skills rely on vicarious

experiences of someone they trust and respect (i.e., teachers) to inform their social identity.

Educationally, Black male teachers provide Black male students with the vicarious experiences

needed to increase their academic self-efficacy. It is through vicarious experiences in academic

settings that Black male students are able to increase their academic self-efficacy and academic

performance.

Summary

Black male students are graduating high school at lower rates, performing lower on

standardized tests, and are more likely to be suspended or expelled. (Schott Foundation for

Public Education, 2015). Within their academic settings, Black male students experience

stereotype threat (Steele & Aronson, 1995), which is the risk of confirming negative stereotypes.

In other words, Black male students feel threatened by the stereotype that they are academically

inferior to their peers. Research conducted by Aronson, Fried, & Good (2002) revealed that

students who experienced higher levels of stereotype threat performed lower on standardized

tests. As an intervention to reduce stereotype threat, presenting role models that share similar

experiences to those students were influential in decreasing levels of stereotype threat (Aronson,

21

et al., 2002) For Black male students, those role models are Black male teachers, who

additionally, increase levels of academic self-efficacy.

The purpose of this literature review was to highlight the educational experiences of

Black male students and Black male teachers and to explore relevant literature related to the

research study. Within this literature review was an analysis and exploration of Bandura’s Self-

Efficacy Theory (Bandura, 1977) which grounds this research. Additionally, presented were gaps

in the literature regarding the quantitative academic impact that Black male teachers have on

students, specifically, Black male students.

22

CHAPTER THREE

METHODOLOGY

Introduction/Overview of Study/Organization of Chapter

This chapter will provide a rationale for the intended research design and methodology

for this study. Following this section, the chapter provides an explanation of the population of

students and sample chosen to participate in the study. It will describe the instrumentation used

as well as the data collection and analysis procedures and any intended delimitations and

limitations to the study.

Rationale for Research Design and Methodology

The selection of research methods is influenced by factors such as worldviews, the

research problem and the research question posed (Creswell, 2014). Worldviews represent a

fundamental set of beliefs which guide actions (Creswell, 2012). It is important to examine

worldviews as they relate to the selection of research methods because they will help to explain

the researcher’s rationale for the chosen research method. The following sections briefly outline

the major tenets of four worldviews and discusses the selection process for the research methods

for this study.

In selecting the appropriate research method for this study, qualitative methods and

mixed methods were eliminated for three reasons. First, the study did not seek to understand the

perceptions or experiences of Black male students, an objective which requires open-ended

questions. second, qualitative methods yield results that are not intended to be generalized for a

population. Such results would not align with the primary objective of this study, which is to

determine whether or not there is a difference in the academic self-efficacy of Black male

students taught by a Black male teacher compared to the academic self-efficacy of Black male

23

students taught by a White male teacher. Third, because the study is not using a combination of

open-ended and closed-ended questions, a mixed methods approach was eliminated.

Research Approach

Since the research was primarily concerned with finding a solution to a real-world

problem--poor educational outcomes for Black male students- the Pragmatic worldview is most

suitable for this study. The Pragmatic worldview is a problem-oriented philosophy that utilizes

either a quantitative or qualitative approach to answer a relevant research question (Creswell,

2014). Results from this study focused on addressing the current gap in quantitative research

which demonstrates the difference in academic self-efficacy between Black male students taught

by a Black male teacher compared to the academic self-efficacy of Black male students taught by

a White male teacher. To this end, the research question will be answered using a causal

comparative design to determine if there is a difference in Black male students’ academic self-

efficacy when taught by a Black male teacher compared to Black male students who are taught

by a White male teacher.

A causal comparative design is a research design that seeks to find relationships between

dependent and independent variables after an action has occurred (Ragin & Zaret, 1983). For this

research, the independent variables are Black and White male teachers, the dependent variable is

Black male student’s academic self-efficacy. In order to minimize the effects of other variables,

the controls in this research are the student’s grade level, age range, and the course taught by the

teacher. Levels of academic self-efficacy when taught by a Black male teacher compared to

Black male students who are taught by a White male teacher was measured. To measure Black

male students’ academic self-efficacy, Gafor and Ashraf (2006) academic self-efficacy survey

will be administered. This study is guided by the following research question:

24

Research Question (RQ1):

1.) Is there a difference in the academic self-efficacy of Black male students when taught by a

Black male teacher compared to the academic self-efficacy of Black male students taught by a

White male teacher?

Hypothesis

Black male students taught by a Black male teacher have a higher mean score of academic self-

efficacy compared to Black male students taught by a White male teacher. The research question

will be answered through a quantitative research study that entails distributing Gafor and

Ashraf’s (2006) adapted Academic Self-Efficacy Scale to measure Black male students’

academic self-efficacy. To determine the difference in Black male students’ academic self-

efficacy when taught by a Black male teacher compared to the academic self-efficacy of Black

male students taught by a White male teacher, this study employs a causal comparative research

design to compare any difference that exist in the academic self-efficacy of Black male students

taught by a Black male teacher to Black male students who are taught by a White male teacher.

To test the hypotheses, the researcher utilized a causal comparative study to analyze whether a

difference exists in Black male students’ academic self-efficacy when taught by a Black male

teacher compared to Black male students’ academic self-efficacy when taught by a White male

teacher.

Population/Sampling

To explore the differences between Black male students’ academic self-efficacy when

taught by a Black male teacher compared to the academic self-efficacy of Black male students

taught by a White male teacher, the intended population were students enrolled in a high school

located in the southeast region of the United States that are 18 years or older. Participants were

25

required to be 18 years or older to participate in the study. Individuals under the age of 18 years

old would not be able to participate because of the need for parental consent. In order to answer

the research question, a matching technique was utilized to select the sample. Matching is a

technique that researchers use to identify one or more characteristics and selects participants who

have these characteristics for both the control and the experimental group (Creswell, 2014). For

this experiment, a purposive sampling technique was used. Purposive sampling requires the

researcher to select participants based upon the needs of the study (Creswell, 2014). Participants

chosen were classified as a 12

th

grader, identified as a Black male, and enrolled in a senior level

mathematics course taught by either a Black male teacher or a White male teacher. Based on the

setting of this study, the senior level mathematics class was chosen because it was the only

subject in the specific setting that had both a Black male and a White male teacher as the

identified instructor of the same course. Both class classes are mathematics, senior level classes,

which is why 12

th

grade students were also chosen as a part of the sample.

Instrumentation

The survey instrumentation and questionnaire were provided to participants 18 years or

older enrolled in a senior level mathematics class taught by either a Black or White male teacher.

Prior to distribution, the research ensured the chosen teachers identified as either a White or

Black male teacher. To collect information from the participants, informed consent was obtained

using an approved written consent form signed by participants. A copy was provided to the

participants in the study. In order to identify the difference in Black male students’ academic

self-efficacy when taught by a Black male teacher compared to the academic self-efficacy of

Black male students taught by a White male teacher, a self-administered, academic self-efficacy

questionnaire adapted from Gafor and Ashraf (2006) self-efficacy questionnaire study will be

26

utilized to collect academic self-efficacy data from the participants. Students reported their

confidence on a 40 item five-point Likert scale questionnaire, ranging from exactly true to

exactly false. A Likert scale is a construct, which is a five-point or seven-point scale that was

developed by psychologist Rensis Likert (Creswell, 2014). Typically, the choices range from

strongly agree to strongly disagree. For this study, the Gafor and Ashraf (2006) academic self-

efficacy questionnaire is based on the idea that the efficacy of students in each dimension of

academic work, contributes to their academic-self efficacy. The dimensions of academic work

were Reading, Learning process, Comprehension, Memory, Peer Relationship, Utilization of

resources, Curricular Activities, Time Management, Teacher Student relationship, Goal

Orientation, Adjustment, and Examination. There are both 20 positive and negative statements.

Participants responded to each statement by choosing any of the five choices: Exactly true,

Nearly true, Neutral, Nearly false, and Exactly false. Participants marked an “X” for his/her best

response. For the positive statements, five scores are provided: 5 points for exactly true, 4 points

for nearly true, 3 points for neutral, 2 points for nearly false, and 1 point for exactly false.

Negative statements were scored in reverse (Gafor & Ashraf, 2006).

Data Collection and Procedures

Data collection and storage practices were required to ensure confidentiality. Participants

remained anonymous. After the researcher collected the names of the potential survey

participants, they were contacted in person and given a written document that explained the

study. Once consent was received, they were given a copy of the survey instrument.

Adopting methods and strategies outlined by Radhakrishna (2007) and Newton and Shaw

(2014) the survey instrument was validated using two methods: Content and Concurrent validity.

Content validity was assured through expert judgements of inclusion of items from the

27

dimensions of the construct (Gafor & Ashraf, 2006). Concurrent validity was assured against

The General Self-Efficacy scale used in Jerusalem and Schwarzer’s (1992) study. Reliability was

assured in Gafor and Ashraf’s (2006) study. Test-retest coefficient of correlation =.85 (N=30);

Split half-Reliability of the scale = .90 (N=370).

Data Analysis Procedures

Given the nature of the survey instrument, descriptive statistics (frequencies, mean,

median, mode, percentages, etc.) were used to analyze data and determine the relationship

between the identified dependent and independent variables. In order to determine the difference

in Black male student’s academic self-efficacy when taught by a Black male teacher compared to

the academic self-efficacy of Black male students when taught by a White male teacher, a one-

way ANOVA will be conducted. A one-way ANOVA is used to test for relationships between

two or more groups (Zhang & Liang, 2014). This test determines whether or not there is a

significant difference between groups based on their mean score (Salkind, 2010). For this study,

the two comparative samples are, Black male students taught by a Black male teacher and Black

male students taught by a White male teacher. Data cleaning was the first step in analyzing the

distribution of factors.

Conclusion

The goal of this chapter was to outline the research methodology used to answer the

presented research question and hypothesis. Included in this chapter is the research question,

hypothesis, rationale for design, sampling method chosen, and instrumentation used.

Additionally, a discussion of the research participants, data procedure and analysis was provided.

28

CHAPTER FOUR

FINDINGS

Introduction

Academically, Black male students are not performing at the same rate as their academic

peers (Ford & Moore, 2013). Although school districts around the country have attempted to

close the achievement gap between Black male students and their classmates, Black male

students are still not academically achieving at the same rate as their peers (Schott Foundation

for Public Education, 2015). In his research, Albert Bandura (1997) suggests that a student’s

self-efficacy will impact their academic performance. Academic self-efficacy is a student’s belief

in whether or not they can perform an academic task. Recent research by King (2016) suggests

that there is a relationship between a student’s academic self-efficacy and their academic

performance.

The purpose of this study was to determine if there is a difference in the academic-self

efficacy of Black male students taught by a Black male teacher compared to the academic self-

efficacy of Black male students taught by a White male teacher. This study was conducted using

quantitative research study that entails distributing Gafor and Ashraf’s (2006) Academic Self-

Efficacy Scale to Black male high school students all 18 years or older, enrolled in two

Mathematics class taught by a Black male teacher or a White male teacher, to measure Black

male students’ academic self-efficacy to answer the following research question:

1.) Is there a difference in the academic self-efficacy of Black male students taught by a Black

male teacher compared to the academic self-effiacy of Black male students taught by a White

male teacher?

The chapter began with an analysis of the quantitative data collected from the students,

18 years or older, enrolled in a high school in Southeastern Louisiana. The overview of the

29

analysis will include the description of the population, description of the participants, the

statistical analysis, and procedures. The results of student’s responses to the following self-

efficacy dimensions of academic work of: Reading, Learning process, Comprehension, Memory,

Peer Relationship, Utilization of resources, Curricular Activities, Time Management, Teacher

Student relationship, Goal Orientation, Adjustment, and Examination were measured. Students

reported their confidence on a 40 item five-point Likert scale questionnaire, ranging from exactly

true to exactly false. The end of chapter 4 present a summary of the data findings as they relate to

the research question.

Description of Site(s)/Population

In order to answer the study’s research question, the research utilized data collected from

a Likert-scale academic self-efficacy survey instrumentation that was adapted from Gafor and

Ashraf (2006) academic self-efficacy survey. The instrument was internet-based and each

student was given a web address to access the survey to keep all the information confidential.

The target population for this research study consisted of Black male students, 18 years or older,

enrolled in a high school located in the southeastern region of the United States, who are in the

two same level mathematics class taught by either a Black male or a White male teacher. A

recruitment script was read to the target population (see Appendix A). As aforementioned, the

survey was housed online (www.surveymonkey.com/r/Academicselfefficacy). Data was

collected from 22 respondents and analyzed using SPSS (Statistical Package for Social

Sciences).

Twenty-two of the twenty-three Black male students aged 18 years or older, enrolled in

the same level mathematics class, agreed to participate in the research. The actual sample

represented in this research study consisted of 22 Black male students aged 18 years or older,

30

enrolled in the same level mathematics class taught by either a Black or White male teacher

(n=22). While serving in the role of a school administrator, the researcher accessed school data

to gather information about students. Participation in this study was 100% voluntary. The

research did not coerce students to participate in the study. The average response rate was 100%

for each question asked. The intervention group (n=12) consisted of 12 students who were

enrolled in a mathematics class taught by a Black male teacher. The control group (n=10)

consisted of 10 Black male students who were enrolled in a mathematics class taught by either a

Black or White male teacher.

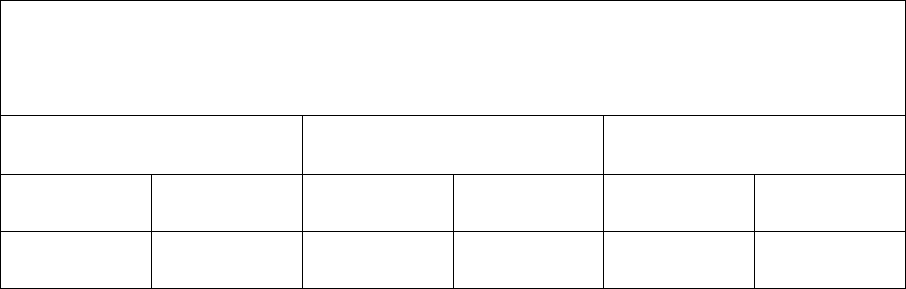

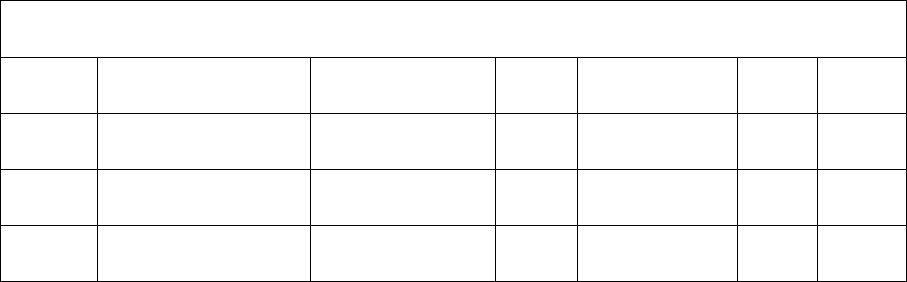

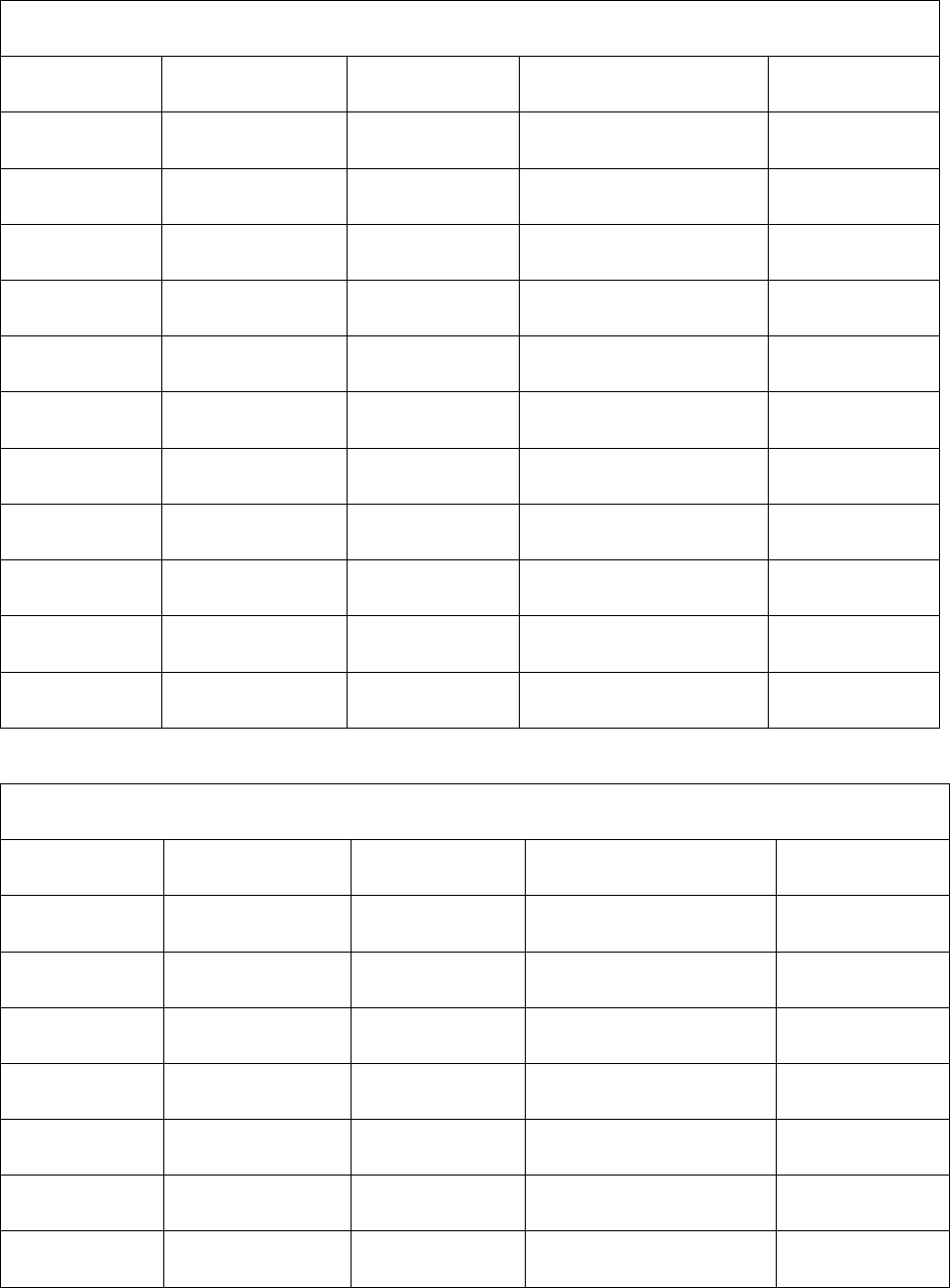

Table 1 Demographics of Sample Population

Intervention Group (n=12)

Control Group (n=10)

Total (n=22)

n

%

N

%

N

%

12

55%

10

45%

22

100

Statistical Analysis: Research Question #1

The research study investigated the following research question. “Is there a difference in

the academic self-efficacy of Black male students taught by a Black male teacher compared to

the academic self-efficacy of Black male students taught by a White male teacher?” In order to

determine whether or not there is a difference in the academic self-efficacy of Black male

students taught by a Black male teacher compared to the academic self-efficacy of Black male

students taught by a White male teacher, a one-way ANOVA was performed to compare the

academic self-efficacy of the two groups using an adapted academic-self efficacy questionnaire

31

(Gafor & Ashraf, 2006). There were 40 total positive and negative statements (20 positive and 20

negative). Participants responded to each statement by choosing any of the five choices: Exactly

true, Nearly true, Neutral, Nearly false, and Exactly false. Participants were required to mark an

“X” for his/her best response. For the positive statements, five scores were provided: 5 points for

exactly true, 4 points for nearly true, 3 points for neutral, 2 points for nearly false, and 1 point for

exactly false. Negative statements were scored in reverse (Gafor & Ashraf, 2006). A mean score

of 5 equates to high academic self-efficacy and a score of 1 equates to a low academic-self

efficacy.

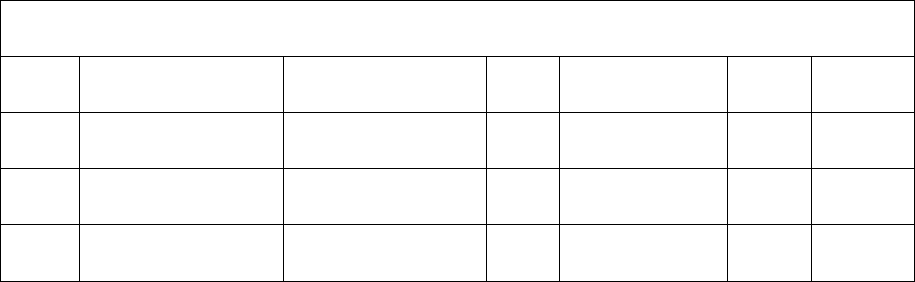

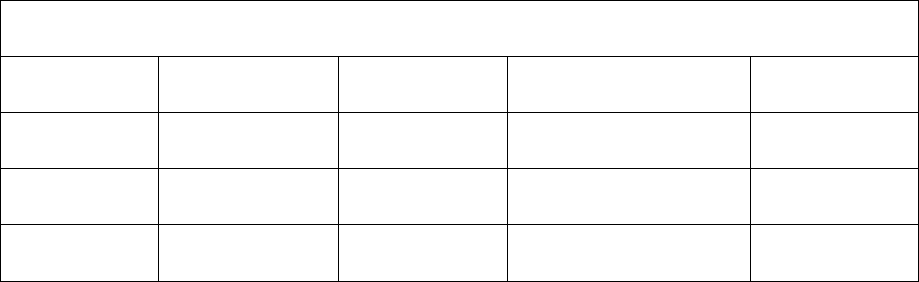

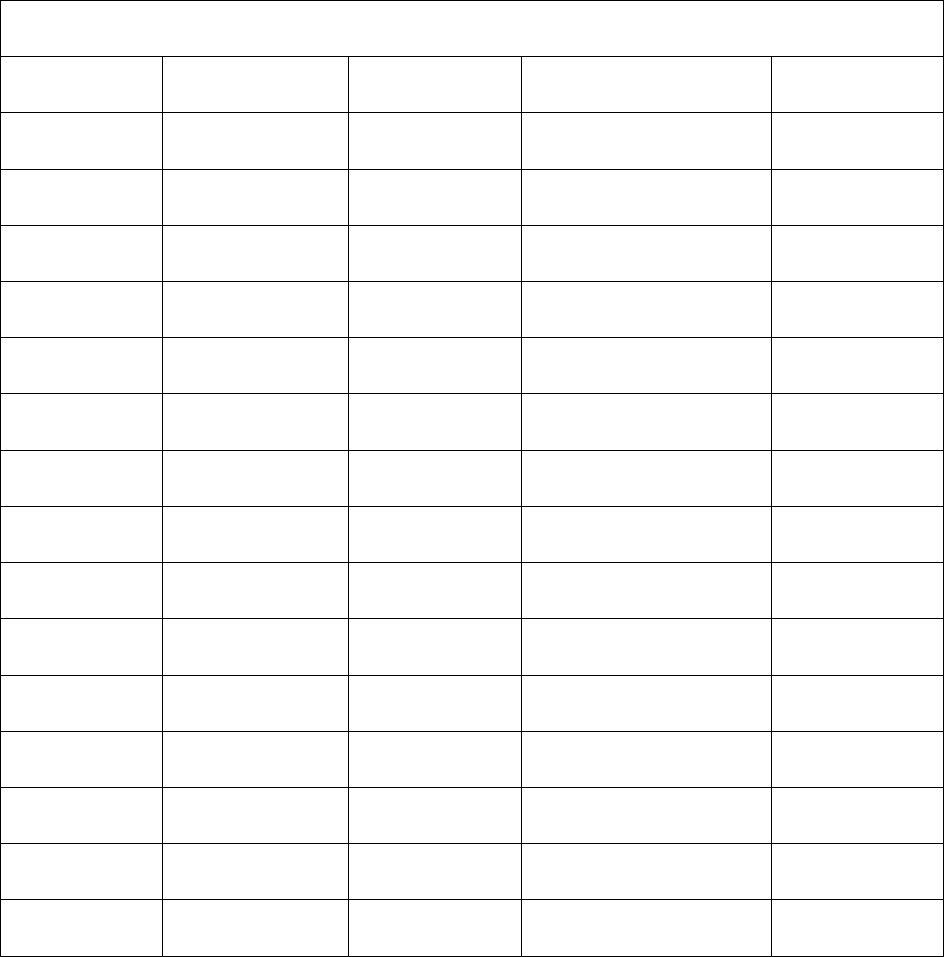

A One-Way ANOVA test was performed to determine if there was a statistical difference

in the mean scores between the academic self-efficacy of Black male students taught by a Black

male teacher compared to the academic self-efficacy of Black male students taught by a White

male teacher. Overall, the sum of squares between Black male students taught by a Black male

teacher compared to Black male students taught by a white male teacher was .246. The degree of

freedom (df) was 1. The Mean Square was .246 and the F ratio was 1.179. The significance (P

value) between both groups were .290 (p=.290), which indicated that there is no significant

difference in the academic self-efficacy between both groups. Because the value was not less

than 0.05, the variation in the academic self-efficacy was not statistically significant and the

study’s hypothesis was rejected.

Table 2 One Way ANOVA Mean Results

Sum of Squares

df

Mean Square

F

Sig

Mean

Between Groups

.246

1

.246

1.179

.290

Within Groups

4.177

20

.209

Total

4.423

21

32

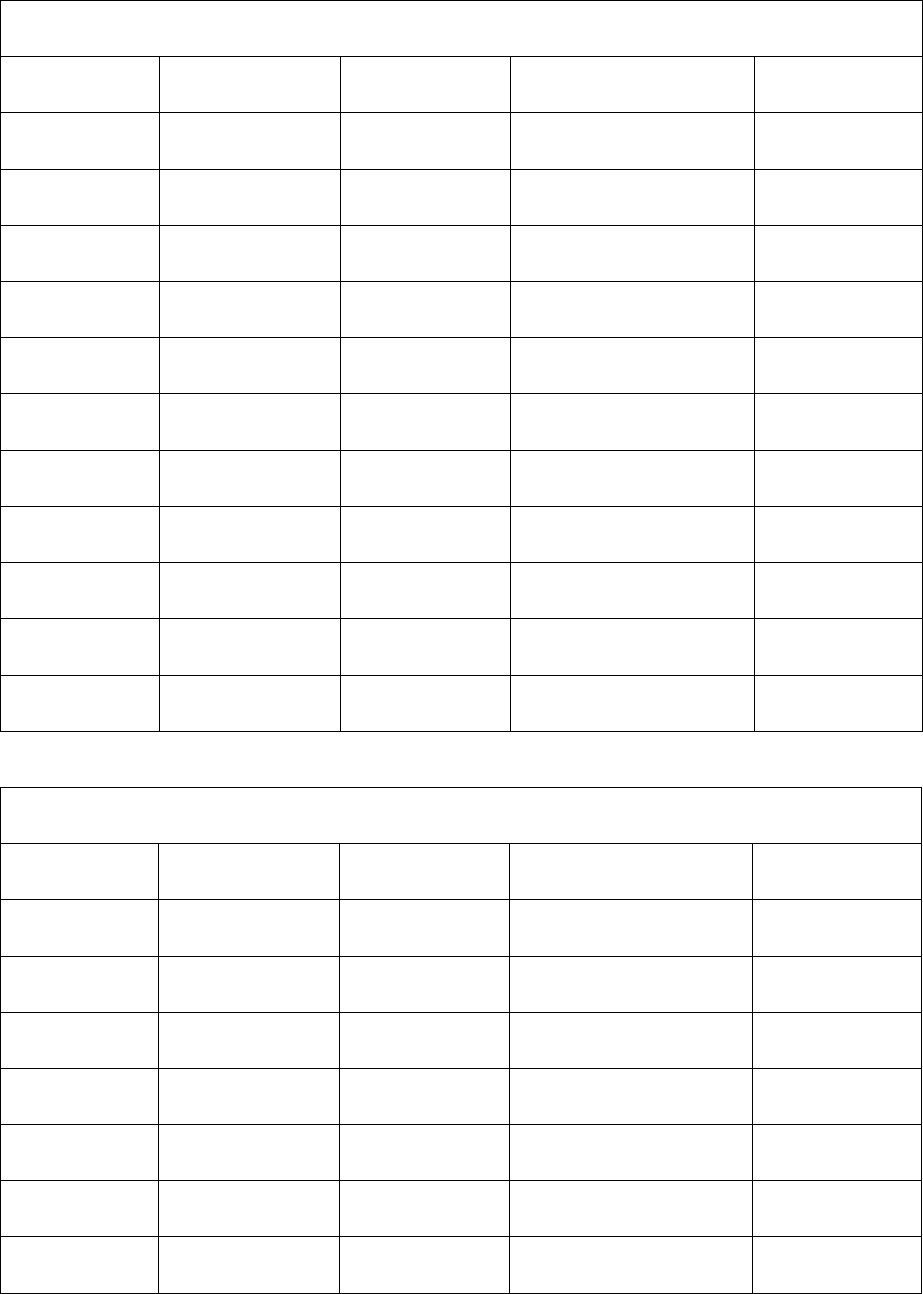

A One-Way ANOVA was also conducted to determine the difference in how both groups

responded to questions 1-40 on the (Gafor & Ashraf, 2006) academic self-efficacy survey. The

significance (p value) for all questions with the exception of question number 39 (Appendix 1)

was not less than 0.05, which indicated there was no statistically significant difference in the

participants’ responses. For question number 39 (Table 3), the Sum of squares between Groups

was 4.097, the degree of freedom (df) was 1, the Mean square was a .246, and the significance

between both groups’ response was a .047 (p=.047). Because the value was less than 0.05, the

variation is their responses were statistically significant. Table 4 lists each question and the p

value for each question.

Table 3 One Way ANOVA Results for Question Number 39

Sum of Squares

df

Mean Square

F

Sig

Num39

Between Groups

4.097

1

4.097

4.486

.047

Within Groups

18.267

20

.913

Total

22.364

21

33

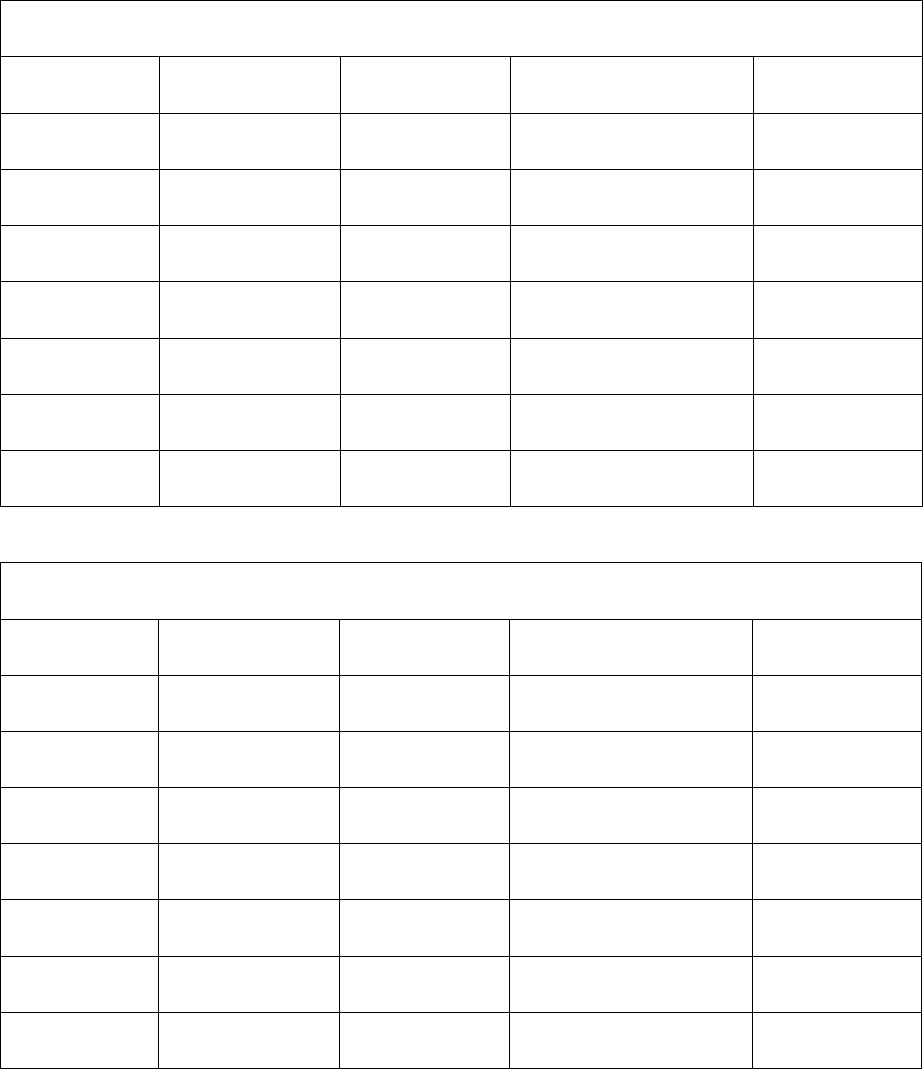

Table 4 One Way ANOVA Results for Questions 1-40

Number

Sig.

1

.171

2

,695

3

,854

4

.118

5

.899

6

.468

7

.160

8

.679

9

.460

10

.748

11

.756

12

.692

13

.969

14

.414

15

.672

16

.331

17

.861

18

.676

19

.760

20

.589

34

21

.277

22

.935

23

.162

24

.307

25

.544

26

.092

27

.162

28

.606

29

.135

30

.535

31

.080

32

.241

33

.218

34

.416

35

.733

36

.212

37

.366

38

.858

39

.047

40

.870

Mean

.290

35

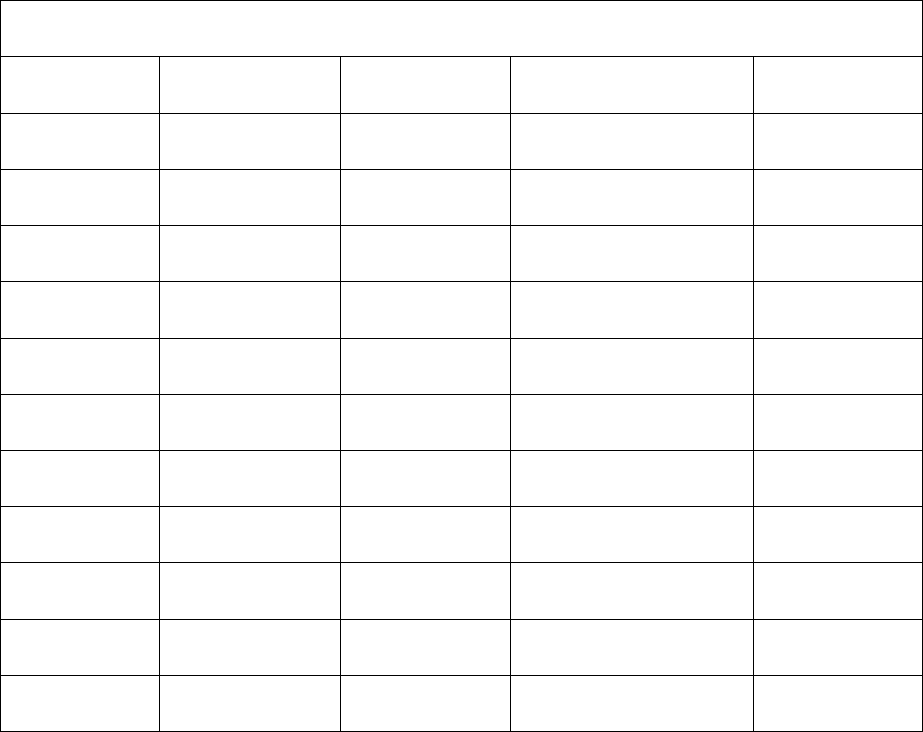

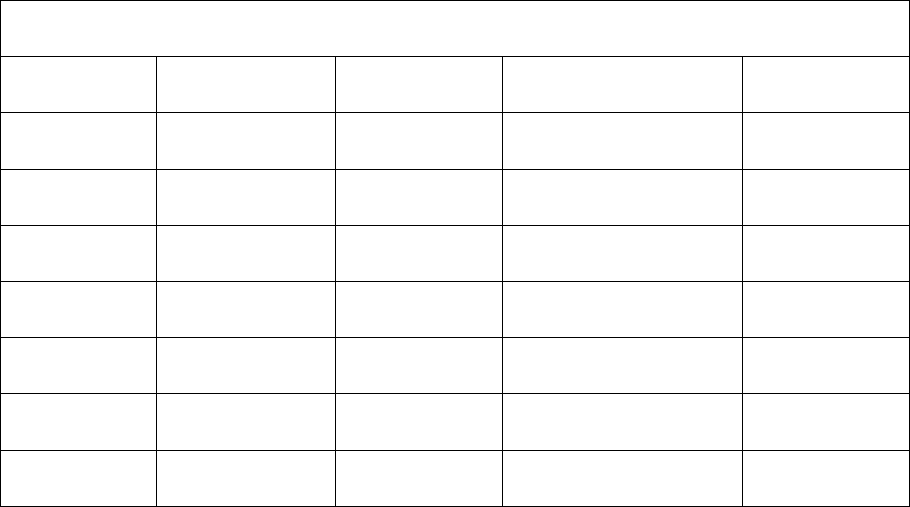

A One-Way ANOVA was used to compare the means of the academic self-efficacy of

Black male students taught by a Black male teacher compared to the academic self-efficacy of