KEL979

January 5, 2017

©2017 by the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University. This case was prepared by Greg Merkley

under the supervision of Professor Russell Walker. Cases are developed solely as the basis for class discussion.

Cases are not intended to serve as endorsements, sources of primary data, or illustrations of effective or ineffective

management. To order copies or request permission to reproduce materials, call 800-545-7685 (or 617-783-7600

outside the United States or Canada) or e-mail [email protected]. No part of this publication may be

reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, used in a spreadsheet, or transmitted in any form or by any means—

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without the permission of Kellogg Case Publishing.

RUSSELL WALKER AND GREG MERKLEY

Chipotle Mexican Grill: Food with

Integrity?

By any measure, Chipotle Mexican Grill was a success story in the restaurant business. It grew

from one location in 1993 to over 2,000 locations by 2016 and essentially created the fast-casual

dining category. One analyst called it “probably the best restaurant brand created in 10 or 15

years.”

1

Its stock appreciated more than 1,000% in the ten years following its 2006 IPO.

In January 2015 the company was lauded for delivering on its promise of “food with integrity”

when it took pork off its menu for six months until it could ensure a supply of humanely raised

meat. Then, in the second half of the year, after more than 20 years without a major reported food

safety incident, Chipotle was revealed as the source of multiple outbreaks of illness from norovirus,

salmonella, and E. coli that sickened nearly 600 people in 13 states. The company closed stores,

spent several months under investigation by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

(CDC) and other health organizations, and faced a criminal investigation in connection with the

incidents.

2

After a much-publicized closing of all of its stores on February 8, 2016, and numerous

changes to its food sourcing and preparation practices, Chipotle tried to win back customers with

dramatically increased advertising and free food promotions.

However, on April 26 the chain announced its rst-ever quarterly loss as a public company.

Same-store sales for the rst quarter were 29.7% lower than in the previous year. Operating margins

fell from 27.5% to 6.8% over the same period, and the company’s share price was down 41% from

its summer 2015 high.

What happened to Chipotle, and more importantly, could it be xed?

This document is authorized for use only by Monika Szumilo (monika@reachcambridge.com). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact

customerservice@harvardbusiness.org or 800-988-0886 for additional copies.

2

C h i p o t l e M e x i C a n G r i l l KEL979

K e l l o G G S C h o o l o f M a n a G e M e n t

Fast Casual Dining

Chipotle was considered a fast casual restaurant. The denition of fast casual dining was uid,

but one essential ingredient was price—fast casual restaurants averaged $9 to $13 per receipt,

versus $5 for fast food. In addition, a fast casual restaurant did not offer full table service and

generally prepared food in full view of customers. It offered higher-quality food than at a fast food

restaurant, with fewer frozen or processed ingredients. This prole meant fast casual restaurants

competed against both fast food and full-service restaurants.

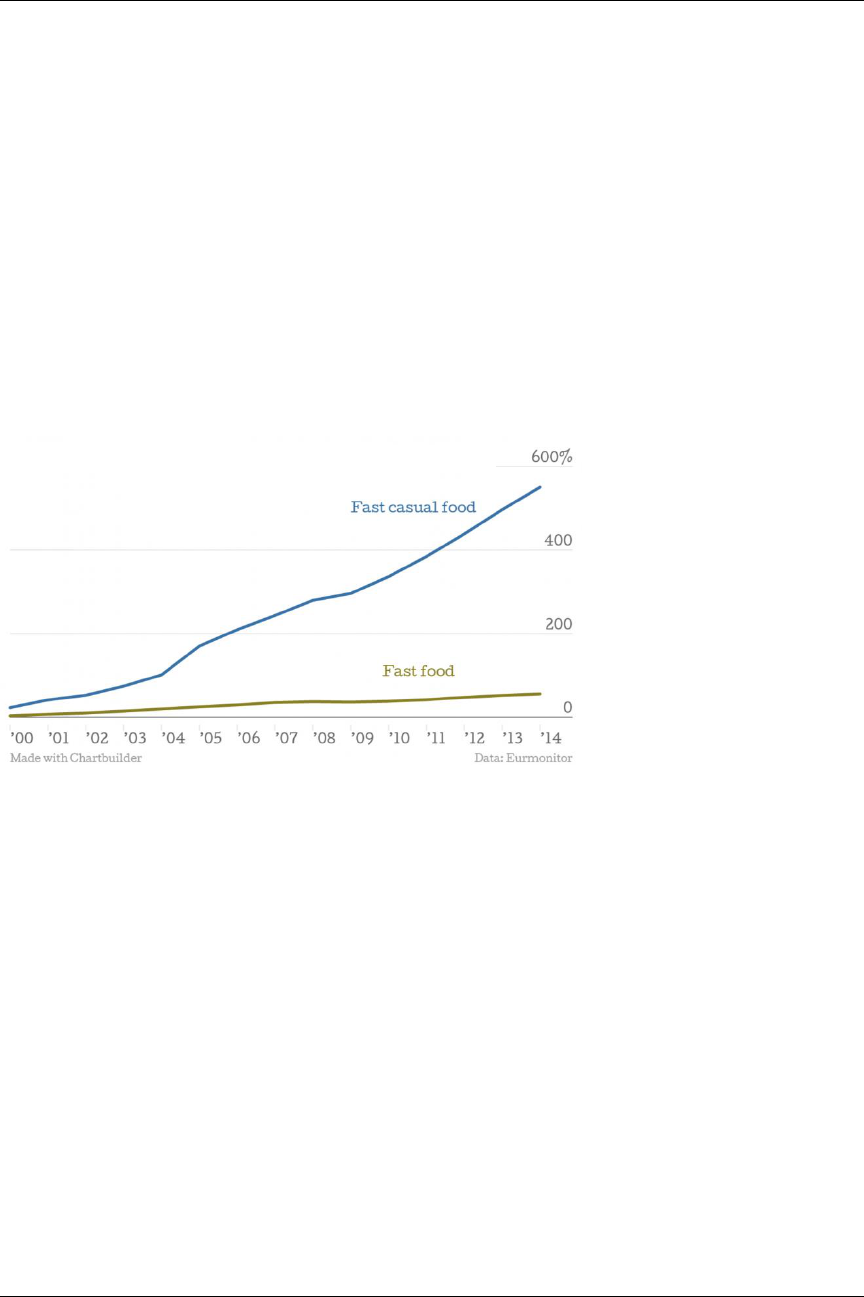

The popularity of fast casual dining in the United States had soared over the past decade; its

sales had grown by 550% from 1999 to 2014, a growth rate ten times that of fast food restaurants

(see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Fast Casual and Fast Food Sales Growth

Source: Roberto A. Ferdman, “The Chipotle Eect: Why America Is Obsessed with Fast Casual Food,” Washington Post, February

2, 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2015/02/02/the-chipotle-eect-why-america-is-obsessed-with-fast-

casual-food.

The fast casual dining segment was fragmented and highly competitive. Panera Bread Co.

was the segment leader, and Chipotle was number two in 2014 with a 17% value share.

3

Price

competition was not a major factor for Chipotle: customers perceived value in its atmosphere,

quick service, and high-quality ingredients. During the post-2008 recession, Chipotle gained

business from consumers trading down from more costly dining options and retained many of

those customers even after the market began to rebound.

4

Chipotle Background

Steve Ells, a classically trained chef, opened the rst Chipotle restaurant in 1993 in Denver,

Colorado. Within one month, the store was selling more than 1,000 burritos per day. Ells added

ve more locations in the Denver area in the next three years. In 1998 McDonald’s Corporation

purchased a minority stake in what was then a 14-store chain, and the next year purchased majority

control of the company. By this time, Chipotle had 37 stores, and McDonald’s continued to invest

This document is authorized for use only by Monika Szumilo (monika@reachcambridge.com). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact

customerservice@harvardbusiness.org or 800-988-0886 for additional copies.

3

C h i p o t l e M e x i C a n G r i l lKEL979

K e l l o G G S C h o o l o f M a n a G e M e n t

in the concept to grow its store base. In 2006 McDonald’s spun off Chipotle in an IPO on the New

York Stock Exchange. As of March 31, 2016, there were 2,066 Chipotle stores worldwide, the vast

majority of which were in the United States.

Ells said: “When I created Chipotle in 1993, I had a very simple idea: Offer a simple menu

of great food prepared fresh each day, using many of the same cooking techniques as gourmet

restaurants. Then serve the food quickly, in a cool atmosphere. It was food that I wanted and

thought others would like too. We’ve never strayed from that original idea. The critics raved and

customers began lining up at my tiny burrito joint. Since then, we’ve opened a few more.”

5

Chipotle’s business model was dened by ve elements: a simple menu; high-quality fresh

ingredients; fast, personalized food; no franchises; and committed employees.

Simple Menu

Chipotle offered only burritos, bowls (essentially a burrito served in a bowl rather than

wrapped in a tortilla), tacos, and salads. The price of each item was based on the choice of meat (or

vegetarian option). There was no extra charge for additional elements, which included rice, beans,

four types of salsa, sour cream, cheese, and lettuce. In total, each store used 64 main ingredients.

6

High-Quality Fresh Ingredients

In 2001 the company adopted the slogan “food with integrity” to describe its approach to

sourcing and preparing ingredients. Chipotle prepared all food on-site from raw ingredients, which

were responsibly sourced from producers that used sustainable, humane practices. It screened

potential suppliers for compliance with the company’s standards for animal care and sustainable

farming.

Chipotle had about 100 suppliers, most of them small- to mid-sized regional companies, not

large national rms. It also sourced ingredients from local farms (within 350 miles of a given

restaurant), but these supplied no more than 12% of its fresh produce in 2015.

7

In most cases the company did not purchase products directly from suppliers. Once suppliers

were approved, they sold to third-party distributors purchasing on behalf of Chipotle. Purchased

goods were taken to 24 independently owned and operated regional distribution centers and then

delivered to Chipotle stores for preparation.

In 2013 Chipotle became the rst major American chain to identify genetically modied

ingredients on its menu. In 2015 it went one step further and announced it would use only non-

GMO foods.

Sourcing meat became a problem as the company grew. In 2013 Chipotle began serving

“conventionally raised” beef because there was not enough antibiotic- and hormone-free beef

available. Then, in January 2015, it removed pork carnitas from the menu in 600 stores when one

of its suppliers violated Chipotle’s standards. Replacing the supplier proved challenging—it took

more than six months to nd a supplier that raised pigs to Chipotle’s standards—but the company

was lauded for its commitment to humanely raised pork.

This document is authorized for use only by Monika Szumilo (monika@reachcambridge.com). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact

customerservice@harvardbusiness.org or 800-988-0886 for additional copies.

4

C h i p o t l e M e x i C a n G r i l l KEL979

K e l l o G G S C h o o l o f M a n a G e M e n t

Despite its high-quality ingredients, Chipotle was criticized for offering food high in calories

and fat. For example, its chicken burrito (with black beans, rice, cheese, and salsa) contained nearly

1,000 calories and 12 grams of saturated fat,

8

equivalent to two Big Macs from McDonald’s.

9

Fast, Personalized Food

Chipotle offered a personalized service model. Customers chose a base for their meal (burrito,

burrito bowl, tacos, or salad) and then selected their choice of meat, rice, beans, salsa, and other

toppings as their meal was prepared in an assembly-line style in front of them.

No Franchises

All Chipotle restaurants were company-owned. During the period of McDonald’s ownership,

the company experimented with franchising in eight locations, but all were later repurchased.

Ownership gave Chipotle total control over how the business was executed in each store.

Committed Employees

In 2016 nearly 60,000 people worked in Chipotle restaurants, most of them relatively

inexperienced and low-paid hourly workers. Employees were paid above-market rates and offered

incentives for performance. They also received two days of paid sick leave each year, a generous

benet by industry standards. As a result, Chipotle employee turnover was lower than the industry

average.

10

Food Safety in the United States

In the United States, numerous safety protocols had been designed to prevent food-borne

illnesses. For example, the U.S. Department of Agriculture developed Hazard Analysis and Critical

Control Point (HACCP), “a management system in which food safety is addressed through the

analysis and control of biological, chemical, and physical hazards from raw material production,

procurement, and handling, to manufacturing, distribution, and consumption of the nished

product.”

11

The system was voluntary, but McDonald’s and other large-scale food producers

incorporated the principles and practices into their operations (and their suppliers’ operations) in

order to reduce the risk of food poisoning by E. coli, salmonella, norovirus, and other pathogens.

Escherichia coli, also known as E. coli, commonly was found in the lower intestine of animals. It

could be transmitted by water used to irrigate crops, or by manure that was not properly treated.

Produce that was hard to clean and eaten raw, such as lettuce, tomatoes, and cilantro, was at

high risk for E. coli contamination. Cooking and properly sanitizing killed E. coli, but restaurants

and food producers combined multiple approaches, including washing hands, preventing cross-

contamination between food items, storing food at proper temperatures, and maintaining adequate

cooking temperatures.

There were many different kinds of salmonella bacteria, which caused food poisoning in

over one million Americans each year. Food—most commonly poultry, beef, eggs, and milk—

This document is authorized for use only by Monika Szumilo (monika@reachcambridge.com). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact

customerservice@harvardbusiness.org or 800-988-0886 for additional copies.

5

C h i p o t l e M e x i C a n G r i l lKEL979

K e l l o G G S C h o o l o f M a n a G e M e n t

could be contaminated with the bacteria during food processing or handling. A common cause

of contamination was food handlers who did not wash their hands with soap after using the

toilet. Preventive measures included refrigeration; cleaning food preparation surfaces; avoiding

cross-contamination of cooked and raw food; fully cooking ground beef, eggs, and poultry; and

pasteurizing milk.

The highly contagious—and common—norovirus sickened millions of people in the United

States every year and was the leading cause of illness from contaminated foods.

12

It was transmitted

by an infected person or contaminated food, water, or surfaces, so the best way to prevent it was

by washing hands properly and frequently and keeping sick workers away from food-processing

areas. Chipotle established protocols to prevent norovirus incidents in its stores after an outbreak

sickened 500 of its customers in Ohio in 2008.

Chipotle’s Food Safety Problems in 2015–16

Chipotle’s public food safety problems began in August 2015 when salmonella from tomatoes

sickened more than 60 people at 28 Chipotle restaurants in Minnesota and Wisconsin. That same

month, 82 customers and 17 employees fell ill with norovirus infections at a Chipotle restaurant in

Simi Valley, California.

The big blow came in October when 22 customers became sick from E. coli at eight of its locations

in Oregon and Washington. All 43 of the region’s stores were closed voluntarily on October 30 due

to what co-CEO Ells called “an abundance of caution.”

13

Shares of Chipotle fell 2.5% on the rst

trading day after the store closings.

Chipotle cooperated with state and federal health ofcials as they tried to identify the origins of

the E. coli strain that caused the outbreak. The Oregon Public Health Division suspected vegetables

rather than meat. “We’ve looked at every food item there, including meat, and it seems like the

common denominator is produce.”

14

Some experts said companies, such as Chipotle, that source fresh produce from small farmers

may be more vulnerable to foodborne illnesses. “A company like McDonald’s tends to work with

large-scale suppliers that have resources of their own to do the types of assessments [that can detect

dangerous pathogens]. . . . But if you’re working with small, independent farmers, it requires a lot

of effort to validate them.”

15

However, other experts pointed out that because some of Chipotle’s

produce was sourced within 350 miles of its stores, outbreaks would tend to be regional, rather

than national, in scope, and thus be smaller and more contained.

16

Chipotle’s CFO said: “We like the local program, we think it’s important, but with what’s just

happened we have to make sure food safety is absolutely our highest priority. If it’s testing and

safety versus taking a step backward on local, we would do that and hope it would be temporary.”

17

An independent expert said, “They were paying attention to [selling food that is unprocessed,

antibiotic- and GMO-free, and local], but they weren’t paying attention to microbial safety.”

18

In response to the outbreak, the company worked with health ofcials to improve its food

handling procedures. It deep-cleaned and sanitized not only the closed stores but all of its

restaurants nationwide. It tested food, preparation surfaces, and equipment in all of its stores and

found no evidence of E. coli. It replaced all ingredients in the closed stores and tested all fresh

This document is authorized for use only by Monika Szumilo (monika@reachcambridge.com). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact

customerservice@harvardbusiness.org or 800-988-0886 for additional copies.

6

C h i p o t l e M e x i C a n G r i l l KEL979

K e l l o G G S C h o o l o f M a n a G e M e n t

produce, raw meat, cheese, and sour cream prior to restocking the stores. It hired two food safety

consulting rms to “assess and improve upon” its “already high standards for food safety.”

19

On

November 10 the company reopened all of its stores in Oregon and Washington.

Early in December, the CDC updated its original count of Chipotle-linked E. coli victims to 52.

It also began investigating ve new cases of E. coli potentially linked to Chipotle. On December 4,

Chipotle warned investors that the E. coli outbreak could cause fourth quarter same-store sales to

decrease 11% and prots 26%.

20

Separately, illnesses linked to Chipotle were reported in seven more states across the United

States.

21

That same month at least 80 students (later increased to 140) were sickened by norovirus

linked to a Chipotle restaurant in Boston. The Boston Public Health Commission said the norovirus

incidents did not appear to be related to E. coli incidents in Oregon and Washington. One food

expert said, “I can’t think of a situation with ve separate incidents involving one restaurant chain

in a six-month period.”

22

Chipotle hired IEH Laboratories and Consulting Group, a food safety research rm, to

improve food safety procedures at Chipotle’s suppliers and restaurants. The company said the

new procedures would put it 10 to 15 years ahead of industry standards. “They’re trying to be local

and serve food with integrity, but as you grow it becomes incredibly complex and difcult and

challenging. When you look at what’s going on, how they’re expanding, the outbreak was almost

bound to happen,” said one observer.

23

Finally, on February 1, 2016, the CDC announced that the E. coli outbreak ofcially was

over. According to the CDC, evidence suggested the outbreak arose from a “common meal item

or ingredient” served at Chipotle, but it was unable to identify the specic ingredient. Chipotle

suspected the cause likely was cross-contamination from beef imported from Australia, a conclusion

the CDC said was unlikely.

24

Impact on Chipotle

On April 26, Chipotle announced its rst-ever quarterly loss as a public company. For the rst

three months of 2016, same-store sales were down 29.7% from the previous year and operating

margins fell from 27.5% to 6.8%. Chipotle’s share price was 41% lower than its high in summer

2015. The company’s CFO admitted that 5% to 7% of its customers had said they would never

return.

25

Chipotle did not provide a public estimate of the cost of its new safety programs. Ells called

them “very, very expensive.” The CFO added, “Right now we’re not trying to make this cost-

effective.”

26

He acknowledged, however, that Chipotle might need to raise prices in order to repair

its margins, noting that “instead of investing [those prots] in food integrity, we might have to

invest that in food safety.”

27

This document is authorized for use only by Monika Szumilo (monika@reachcambridge.com). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact

customerservice@harvardbusiness.org or 800-988-0886 for additional copies.

7

C h i p o t l e M e x i C a n G r i l lKEL979

K e l l o G G S C h o o l o f M a n a G e M e n t

Rebuilding Confidence and Traffic

About the challenge of getting customers to return, the company’s chief creative and

development ofcer said, “There’s nothing worse from a trust perspective. This is not the kind of

problem that you market your way out of.”

28

Chipotle’s other co-CEO, Monty Moran, told investors in early February that the company

had improved its traceability program to identify the specic farm at which each ingredient was

produced in real time through its distribution system and in its individual restaurants via bar

codes on each package.

29

The company also hired food safety expert James Marsden, a meat science

professor at Kansas State University, to oversee food safety for the entire company.

On February 8, Chipotle closed all of its stores for several hours to train employees on new

food safety measures. Among the changes it implemented were the following:

• Cheese will arrive at restaurants already shredded. Tomatoes and cilantro, which are

particularly vulnerable to bacteria, will be washed, chopped, and tested in a central

kitchen. Similar processes will be used for beef, romaine lettuce, and bell peppers.

• In the restaurant, lemons, limes, jalapeños, onions, and avocados will be blanched (plunged

into boiling water before being submerged in ice water to stop cooking) for ve to ten

seconds before serving to reduce germs on their skins. Chipotle claimed this would not

affect avor.

• Employees who are sick or have vomited will be asked to stay home for ve days after

their symptoms have disappeared. Employees will be paid for those days.

• Suppliers will run “DNA-based tests” on small batches of ingredients before shipping

them to restaurants.

• A $10 million Local Grower initiative will be initiated to help small suppliers meet the new

standards.

While the stores were closed on February 8, patrons who showed up were able to request a

“rain check” free burrito. There were 5.3 million requests, twice as many as expected, and two-

thirds of the coupons were redeemed. The company increased its promotional efforts, sending 21

million offers for free food via direct mailings and launching its largest-ever ad campaign in 31 of

its top markets.

30

To improve the in-store experience for customers, Chipotle increased staff hours

to reduce waiting times.

31

Future Outlook

By April 2016, there were positive signs for the brand. Analysts reported that Google searches

for Chipotle and food safety had decreased sharply since the beginning of the year.

32

Troublingly,

however, an analysis of trafc data from Chipotle restaurants by Foursquare Inc. showed that its

most loyal customers had been 50% more likely than infrequent customers to stay away from the

restaurant during the outbreaks, and some had stopped eating at Chipotle altogether.

33

This document is authorized for use only by Monika Szumilo (monika@reachcambridge.com). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact

customerservice@harvardbusiness.org or 800-988-0886 for additional copies.

8

C h i p o t l e M e x i C a n G r i l l KEL979

K e l l o G G S C h o o l o f M a n a G e M e n t

Endnotes

1 Roben Farzad, “Chipotle: The One That Got Away from McDonald’s,” Bloomberg, October 3, 2013,

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2013-10-03/chipotle-the-one-that-got-away-from-mcdonalds.

2 Jim Zarroli, “Chipotle Faces a Criminal Investigation Into Its Handling of a Norovirus Outbreak,” NPR Morning

Edition, January 6, 2016, http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2016/01/06/462147245/chipotle-faces-a-

criminal-investigation-into-its-handling-of-a-norovirus-outbrea.

3 Euromonitor International, “Chipotle Mexican Grill Inc. in Consumer Foodservice (USA),” October 2015, p. 3.

4 Ibid., p. 1.

5 Kal Gullapalli, “How Chipotle Became the Gold Standard of Mexican Fast-Food,” Business Insider, January 21, 2011,

http://www.businessinsider.com/chipotle-the-new-gold-standard-2011-1.

6 Susan Bereld, “Inside Chipotle’s Contamination Crisis,” Bloomberg, December 22, 2015,

http://www.bloomberg.com/features/2015-chipotle-food-safety-crisis.

7 Elliot Maras, “Chipotle Strikes Back,” Food Logistics, April 18, 2016, http://www.foodlogistics.com/article/12185699/

chipotle-strikes-back.

8 “Fresh Mex: Not Always Healthy Mex,” Center for Science in the Public Interest, September 30, 2003,

http://www.cspinet.org/new/200309301.html.

9 Adam Chandler, “Is Fast Food Healthier Than Chipotle?” The Atlantic, February 18, 2015,

http://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2015/02/is-fast-food-better-than-chipotle/385589.

10 Gullapalli, “How Chipotle Became the Gold Standard of Mexican Fast-Food.”

11 U.S. Food and Drug Administration, “Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point (HACCP),” accessed May 27, 2016,

http://www.fda.gov/Food/GuidanceRegulation/HACCP.

12 Bereld, “Inside Chipotle’s Contamination Crisis.”

13 Karlene Lukovitz, “Chipotle’s Brand Strength To Be Tested by E. coli Outbreak,” MarketingDaily, November 5, 2015,

http://www.mediapost.com/publications/article/261876/chipotles-brand-strength-to-be-tested-by-e-coli.html.

14 Julie Jargon, “Chipotle Grapples with E. coli Outbreak,” Wall Street Journal, November 3, 2015, http://www.wsj.com/

articles/chipotle-grapples-with-e-coli-outbreak-1446506975.

15 Ibid.

16 Ibid.

17 Bereld, “Inside Chipotle’s Contamination Crisis.”

18 Ibid.

19 Lukovitz, “Chipotle’s Brand Strength To Be Tested by E. coli Outbreak.”

20 Paul R. La Monica, “Can Chipotle Recover from E. coli Outbreak?” CNNMoney, December 7, 2015,

http://money.cnn.com/2015/12/07/investing/chipotle-stock-e-coli/index.html.

21 Roberto A. Ferdman, “What in the World Is Happening to Chipotle,” Washington Post, December 9, 2015,

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2015/12/09/what-in-the-world-is-happening-to-chipotle.

22 Julie Jargon, “Norovirus Conrmed in Boston Chipotle Outbreak,” Wall Street Journal, December 10, 2015,

http://www.wsj.com/articles/norovirus-conrmed-in-boston-chipotle-outbreak-1449684009.

23 Ferdman, “What in the World Is Happening to Chipotle.”

24 Maras, “Chipotle Strikes Back.”

25 Julie Jargon, “Chipotle to Offer More Free Burritos,” Wall Street Journal, March 16, 2016, http://www.wsj.com/articles/

chipotle-to-offer-more-free-burritos-1458155867.

26 Bereld, “Inside Chipotle’s Contamination Crisis.”

27 Ibid.

28 Ibid.

29 Maras, “Chipotle Strikes Back.”

30 Maxwell Murphy, “Chipotle Food-Safety Problems May Cost It Up to 7% of Customers,” Wall Street Journal, CFO

Journal (blog), March 17, 2016, http://blogs.wsj.com/cfo/2016/03/17/chipotle-food-safety-problems-may-cost-it-up-

to-7-of-customers-cfo.

31 Samantha Bomkamp, “Is Chipotle Doing Enough to Get Customers to Come Back?” Chicago Tribune, April 27, 2016,

http://www.chicagotribune.com/business/ct-chipotle-future-0428-biz-20160427-story.html.

32 Julie Jargon, “Chipotle Counters Frightful Results,” MarketWatch, April 23, 2016, http://www.marketwatch.com/

story/chipotle-counters-frightful-results-2016-04-23-10485737.

33 Ibid.

This document is authorized for use only by Monika Szumilo (monika@reachcambridge.com). Copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. Please contact

customerservice@harvardbusiness.org or 800-988-0886 for additional copies.