www.mdedge.com/jcomjournal Vol. 27, No. 1 January/February 2020 JCOM 41

Original Research

A Comparison of 4 Single-Question Measures

of Patient Satisfaction

Iris I.M. Kleiss, MD, Joost T.P. Kortlever, MD, Prithvi Karyampudi, David Ring, MD, PhD,

Laura E. Brown, PhD, Lee M. Reichel, MD, Matt D. Driscoll, MD, and Gregg A. Vagner, MD

P

atient satisfaction is an important quality metric

that is increasingly being measured, reported,

and incentivized. A qualitative study identified 7

themes influencing satisfaction among people visiting an

orthopedic surgeon’s office: trust, relatedness, expec-

tations, wait time, visit duration, communication, and

empathy.

1

However, another study found that satisfaction

and perceived empathy are not associated with wait time

or visit duration, but rather with the quality of the visit.

2

Satisfaction measures that incorporate many of these fea-

tures in relatively long questionnaires are associated with

lower response rates

3

and overlap with the factors whose

influence on satisfaction one would like to study (eg, per-

ceived empathy or communication effectiveness).

4

Single-

and multiple-question satisfaction scores are prone to a

strong right skew, with a substantial ceiling effect.

5

Ceiling

effect occurs when a considerable proportion (about half)

of participants select 1 of the top 2 scores (or the max-

imum score). An ideal scale would measure satisfaction

independent from other factors, would use 1 or just a few

questions, and would have little or no ceiling effect.

From Dell Medical School, The University of Texas at Austin,

Austin, TX.

ABSTRACT

Objective: Satisfaction measures often show substantial

ceiling effects. This randomized controlled trial tested the

null hypothesis that there is no difference in mean overall

satisfaction, ceiling and floor effect, and data distribution

between 4 different kinds of single-question scales

assessing the helpfulness of a visit. We also hypothesized

that there is no correlation between scaled satisfaction

and psychological status. Finally, we assessed how the

satisfaction scores compared with the Net Promoter

Scores (NPS).

Design: Randomized controlled trial.

Methods: We enrolled 258 adult, English-speaking new and

returning patients. Patients were randomly assigned to

1 of 4 different scale types: (1) an 11-point ordinal scale

with 5 anchor points; (2) a 5-point Likert scale; (3) a

0-100 visual analogue scale (VAS) electronic slider with 3

anchor points and visible numbers; and (4) a 0-100 VAS

with 3 anchor points and no visible numbers. Additionally,

patients completed the 2-item Pain Self-Efficacy

Questionnaire (PSEQ-2), 5-item Short Health Anxiety

Inventory scale (SHAI-5), and Patient-Reported Outcomes

Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Depression.

We assessed mean and median score, floor and ceiling

effect, and skewness and kurtosis for each scale.

Spearman correlation tests were used to test correlations

between satisfaction and psychological status.

Results: The nonnumerical 0-100 VAS with 3 anchor points and

the 5-point Likert scale had the least ceiling effect (12% and

20%, respectively). The 11-point ordinal scale had skewness

and kurtosis closest to a normal distribution (skew = –0.58

and kurtosis = 4.0). Scaled satisfaction scores had

a small but significant correlation with PSEQ-2 (r = 0.17;

P = 0.006), but not with SHAI-5 (r = –0.12; P = 0.052) or

PROMIS Depression (r = –0.12; P = 0.064). NPS were 35,

16, 67, and 20 for the scales, respectively.

Conclusion: Single-question measures of satisfaction can be

adjusted to limit the ceiling effect. Additional research in

this area is warranted.

Keywords: patient satisfaction; floor and ceiling effect;

skewness and kurtosis; quality improvement.

Measures of Patient Satisfaction

42 JCOM January/February 2020 Vol. 27, No. 1 www.mdedge.com/jcomjournal

In this randomized controlled trial, we examined whether

there were significant differences in mean and median satisfac-

tion, floor and ceiling effect, and data distribution (by looking at

skewness and kurtosis) between 4 different kinds of satisfaction

scales asking about the helpfulness of a visit. Additionally, we

hypothesized that there is no correlation between scaled sat-

isfaction and psychological status. Finally, we assessed how

the satisfaction scores compared to the Net Promoter Scores

(NPS). NPS are commonly used in the service industry to

measure customer satisfaction; we are using these scores as a

measure of patient satisfaction.

Methods

Study Design

All English-speaking new and return patients ages 18 to

89 years visiting an orthopedic surgeon in 1 of 7 clinics

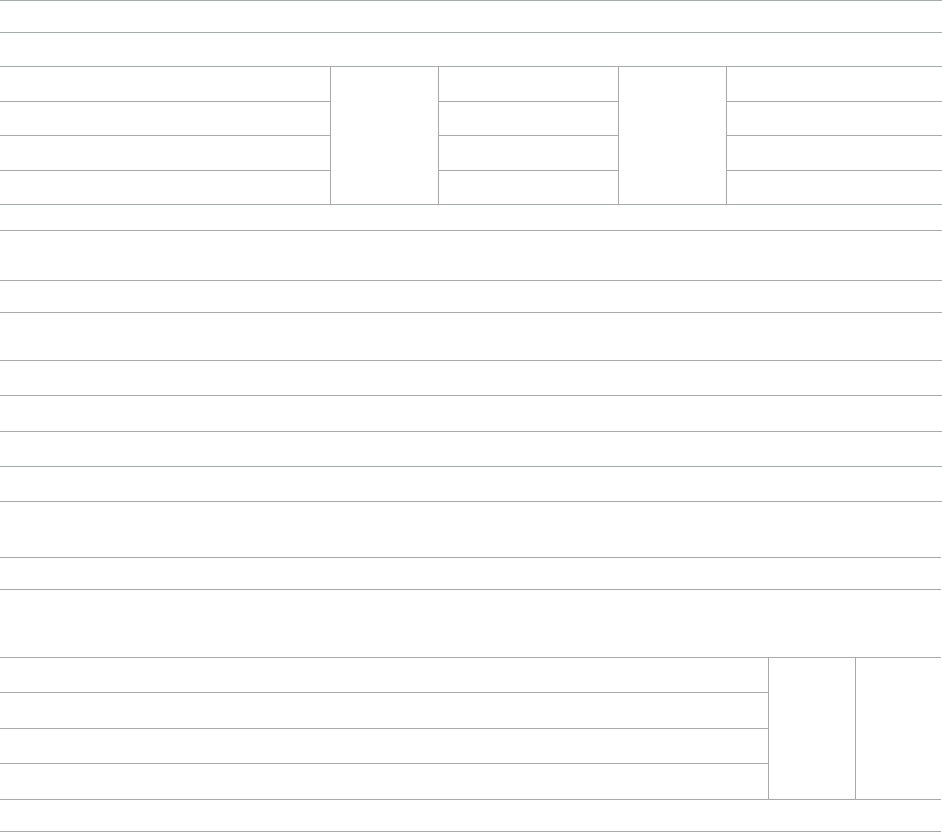

Figure 1. The 4 satisfaction scales. VAS, visual analogue scale.

Scale 4: VAS with slider, 3 anchor points, and no numbers

How helpful was this visit?

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ●

This visit was not

what I hoped

it would be

There were many

ways it could have

been better

Helpful

visit

Exceptionally

helpful visit

One of the most

helpful doctor visits

I have ever had

How helpful was this visit?

● ● ● ● ●

This visit was not

what I hoped

it would be

There were many

ways it could have

been better

Helpful

visit

Exceptionally

helpful visit

One of the most

helpful doctor visits

I have ever had

Scale 1: 11-point ordinal scale with 5 anchor points

How helpful was this visit?

How helpful was this visit?

0 50 100

Scale 2: 5-point Likert scale

Scale 3: 100-point VAS with slider and 2 anchor points

This visit was not

helpful at all

One of the most

helpful doctor visits

I have ever had

Neither useless or

helpful visit

Most helpful

visit

Least helpful

visit

Original Research

www.mdedge.com/jcomjournal Vol. 27, No. 1 January/February 2020 JCOM 43

located in a large urban area were considered eligible

for this study. Enrollment took place intermittently over

a 5-month period. We were granted a waiver of writ-

ten informed consent. Patients indicated their consent

by completing the surveys. Patients were randomly

assigned to 1 of the 4 questionnaires containing differ-

ent scale types using an Excel random-number gen-

erator. After the visit, patients were asked to complete

the survey. All questionnaires were administered on an

encrypted tablet via a HIPAA-compliant, secure web-

based application for building and managing online sur-

veys and databases (REDCap; Research Electronic Data

Capture).

6

This study was approved by our Institutional

Review Board and is registered on ClinicalTrials.gov

(NCT03686735).

7

Outcome Measures

Study participants were asked to complete questionnaires

regarding demographics (sex, age, race/ethnicity, marital

status, level of education, work status, insurance status,

comorbidities) and to rate satisfaction with their visit on the

scale that was randomly assigned to them: (1) an 11-point

Likert scale with 5 anchor points and visible numbers; (2)

a 5-point Likert scale with 5 anchor points and no visible

numbers; (3) a 0-100 VAS with 3 anchor points and visible

numbers; (4) a 0-100 VAS with 3 anchor points and no

visible numbers (Figure 1). The 4 scales should not differ

in time needed to complete them; however, we did not

explicitly measure time to completion. Participants also

completed measures of psychological aspects of illness.

The 2-item Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (PSEQ-2) was

used to measure pain self-efficacy, an effective coping

strategy for pain.

8

Higher PSEQ-2 scores indicate a higher

level of pain self-efficacy. The 5-item Short Health Anxiety

Inventory scale (SHAI-5) was also administered; higher

scores on this scale indicate a greater degree of health

anxiety.

9

The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement

Information System (PROMIS) Depression was used to

measure symptoms of depression.

10

Finally, the diagnosis

was recorded by the surgeon (not in table).

Statistical Analysis

We reported continuous variables using mean, standard

deviation (SD), median, and interquartile range (IQR).

Categorical data are presented as frequencies and per-

centages. We calculated floor and ceiling effect and the

skewness and kurtosis of every scale. We scaled every

scale to 10 and also standardized every scale. We used

the Kruskal–Wallis test to compare differences in satis-

faction between the scales; Fisher’s exact test to com-

pare differences in floor and ceiling effect; and Spearman

correlation tests to test the correlation between scaled

satisfaction scores and psychological status.

Ceiling effects are present when patients select the

highest value on a scale rather than a value that reflects

their actual feelings about a certain topic. Floor effects

are present when patients select the lowest value in a

similar fashion. These 2 effects indicate that an indepen-

dent variable no longer influences the dependent variable

being tested. Skewness and kurtosis are rough indicators

of a normal distribution of values. Skewness (γ1) is an

index of the symmetry of a distribution, with symmetric

distributions having a skewness of 0. If skewness has a

positive value, it suggests relatively many low values, hav-

ing a long right tail. Negative skewness suggests relatively

many high values, having a long left tail. Kurtosis (γ2) is a

measure to describe tailedness of a distribution. Kurtosis

of a normal distribution is 3. Negative kurtosis represents

little peaked distribution, and positive kurtosis represents

more peaked distribution.

11,12

If skewness is 0 and kurtosis

is 3, there is a normal, or Gaussian, distribution.

Finally, we manually calculated the NPS for all scales

by subtracting the percentage of detractors (people who

scored between 0 and 6) from the percentage of promot-

ers (people who scored 9 or 10).

13

NPS are widely used in

the service industry to assess customer satisfaction, and

scores range between –100 and 100.

An a priori power analysis indicated that in order to

find a difference in satisfaction of 0.5 on a 0-10 scale,

with an effect size of 80% and alpha set at 0.05, we

needed 128 patients (64 per group). Since we wanted to

compare 4 satisfaction scales, we doubled this.

Results

Patient Characteristics

All patients invited to participate in this study agreed,

and 258 patients with various diagnoses were enrolled.

The median age of the cohort was 54 years (IQR, 40-65

Measures of Patient Satisfaction

44 JCOM January/February 2020 Vol. 27, No. 1 www.mdedge.com/jcomjournal

years); 114 (44%) were men, and 119 (42%) were new

patients (Table 1). The number of patients assigned to

scales 1, 2, 3, and 4 were 62 (24%), 70 (27%), 67 (26%),

and 59 (23%), respectively.

Difference in Distribution

Looking at the data distribution (Figure 2) and skewness

and kurtosis (Table 2) of the scales, we found that none of

the scales was normally distributed. The 11-point ordinal

scale approached the most normal data distribution, with

minimal skew (γ1, –0.58) and a normal kurtosis (γ2, 4.0).

Difference in Satisfaction Scores

Mean (SD) scaled satisfaction scores (range, 0-10) were

8.3 (1.2) for the 11-point ordinal scale, 8.3 (1.2) for the

5-point Likert scale, 8.9 (1.7) for the 0-100 numerical VAS,

and 8.3 (1.3) for the 0-100 nonnumerical VAS (Table 3

and Table 4). Because of nonnormal distributions, we

tested for a difference using median scores. We found

a difference in median scaled satisfaction scores (range,

0-10) between the 4 satisfaction scales: 11-point ordinal

scale, 8.0 (8.0-9.0); 5-point Likert scale, 8.0 (8.0-8.0);

0-100 numerical VAS, 9.5 (8.9-10); and 0-100 nonnumeri-

cal VAS, 8.4 (7.6-9.5) (P < 0.001; Table 4).

Difference in Floor and Ceiling Effect

A difference was found in ceiling effect between the dif-

ferent scales (P = 0.025), with the 0-100 numerical VAS

showing the highest ceiling effect (34%) and the 0-100

nonnumerical VAS showing the lowest ceiling effect (12%;

25

20

15

10

5

0

0 5 10

Number of patients

Satisfaction score

Satisfaction scale 1

20

15

10

5

0

0 50 100

Number of patients

Satisfaction

Satisfaction scale 3

6

4

2

0

0 50 100

Number of patients

Satisfaction

Satisfaction scale 4

50

40

30

20

0

0

1 2 3 4 5

Number of patients

Satisfaction score

Satisfaction scale 2

Figure 2. Data distribution of the 4 scales.

Original Research

www.mdedge.com/jcomjournal Vol. 27, No. 1 January/February 2020 JCOM 45

Table 2). There was no floor effect. A single patient used

the lowest score (on the Likert scale).

Correlation Between Satisfaction

and Psychological Status

Scaled satisfaction scores had a small but significant cor-

relation with PSEQ-2 (r = 0.17; P = 0.006), but not with

SHAI-5 (r = –0.12; P = 0.052) or PROMIS Depression (r =

– 0.12; P = 0.064; not in table), indicating that patients with

more self-efficacy had higher satisfaction ratings.

Net Promoter Scores

NPS were 35 for the 11-point ordinal scale; 16 for the

5-point Likert scale; 67 for the 0-100 numerical VAS; and

20 for the 0-100 nonnumerical VAS.

Discussion

Single-question measures of satisfaction can decrease

patient burden and limit overlap with measures of com-

munication effectiveness and perceived empathy. Both

long and short questionnaires addressing satisfaction

and perceived empathy show substantial ceiling effect.

We compared 4 different measures for overall scores,

floor and ceiling effect, and skewness and kurtosis, and

assessed the correlation between scaled satisfaction

and psychological status. We found that scale type

influenced the median helpfulness score. As one would

expect, scales with less ceiling effect have lower median

scores. In other words, if the goal is to collect meaning-

ful information and identify areas for improvement, there

must be a willingness to accept lower scores.

Only the nonnumerical VAS was below the threshold of

15% ceiling effect proposed by Terwee et al.

14

This scale

with 3 anchor points and no visible numbers showed the

least ceiling effect (12%) and minimal skew (–1.0), and was

closer to kurtosis consistent with a normal distribution (5.0).

However, the 11-point ordinal Likert scale with 5 anchor

points and visible numbers had the lowest skewness and

kurtosis (–0.58 and 4.0). The low ceiling effect observed

with the nonnumerical VAS (12%) might be explained by

the fact that the scale does not lead patients to a specific

description of the helpfulness of their visit, but rather asks

patients to use their own judgement in making the rat-

ing. The ordinal scale approached the most normal data

distribution, and this might be explained by the presence

of numbers on the scale. Ratings based on a 0-10 scale

are commonly used, and familiarity with the system might

have allowed people to pick a number that represents their

Table 1. Patient and Clinical Characteristics

Variables

Patients

(n = 258)

Median age, yr (IQR) 54 (40-65)

Male, no. (%) 114 (4 4)

Race, no. (%)

White 177 (69)

Latino/Hispanic 49 (19)

Other 32 (12)

Marital status, no. (%)

Married/unmarried couple 162 (63)

Single 58 (22)

Divorced/separated/widowed 38 (15)

Level of education, no. (%)

High school or less 69 (27)

2-year college 43 (17)

4-year college 78 (30)

Post-college graduate degree 68 (26)

Work status, no. (%)

Employed 162 (63)

Retired 54 (21)

Other 42 (16)

Insurance status, no. (%)

Private 139 (54)

Medicare 70 (27)

Other 49 (19)

Type of visit, no. (%)

New 109 (42)

Follow-up 149 (58)

Median PSEQ-2 score (IQR) 11 (8 -12)

Median SHAI-5 score (IQR) 9 (8 -11)

Median PROMIS Depression score (IQR) 48 (42-53)

IQR, interquartile range; PROMIS, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement

Information System; PSEQ-2, Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire short form;

SHAI-5, Short Health Anxiety Inventory short form.

Measures of Patient Satisfaction

46 JCOM January/February 2020 Vol. 27, No. 1 www.mdedge.com/jcomjournal

actual view of the visit helpfulness, rather than picking the

highest possible choice (which would have led to a ceiling

effect). Study results comparing Likert scales and VAS are

conflicting,

15

with some preferring Likert scales for their

responsiveness

16

and ease of use in practice,

17

and others

preferring VAS for their sensitivity to describe continuous,

subjective phenomenon and their high validity and reliabil-

ity.

18

Looking at our nonnumerical VAS, adding numbers to

a scale might not help avoid, and may actually increase,

the presence of ceiling effect. However, with the ordinal

scale with visible numbers, we saw a 21% ceiling effect

coupled with low skew and kurtosis (–0.58 and 4.0), which

indicate that the distribution of scores is relatively normal.

This finding is in line with other study results.

19

Our findings demonstrated that feedback concerning

self-efficacy, health anxiety, or depression had no or only

a small effect on patient satisfaction. Consistent with prior

evidence, psychological factors had limited or no correla-

tion with satisfaction.

20-24

Given the effect that priming

has on patient-reported outcome measures, the effect of

psychological factors on satisfaction could be an area of

future study.

Table 3. Characteristics of Scales

Scale

Visible

Anchors (no.)

Visible

Numbers

Possible

Range

Possible

Scaled Range

1 Yes (5) Yes 0-10 0-10

2 Yes (5) No 1-5 2-10

3 Yes (3) Yes 0-100 0 -10

4 Yes (3) No 0 -100 0-10

Table 4. Distribution of Scale Scores

Scale

Completed,

no. (%)

Mean

Score

(SD)

Median

Score (IQR) Range

Mean Scaled

Score (SD)

Median

Scaled

Score (IQR)

Mean

Scaled

Range

P Value

Scaled and

Standardized Scores

1 62 (24) 8.3 (1.2) 8.0 (8.0-9.0) 4-10 8.3 (1.2) 8.0 (8.0-9.0) 4.0-10

< 0.001 < 0.001

2 70 (27) 4.1 (0.5 9) 4.0 (4.0-4.0) 1-5 8.3 (1.2) 8.0 (8.0-8.0) 2.0 -10

3 67 (26) 89.0 (17) 95.0 (89-100) 10-100 8.9 (1.7) 9.5 (8.9 -10) 1.0-10

4 59 (23) 83.0 (13) 84.0 (76-95) 35-100 8.3 (1.3) 8.4 (7.6-9.5) 3.5 -10

IQR, interquartile range.

Table 2. Floor and Ceiling Effect and Skewness and Kurtosis of the Scales

Scale Floor Effect P Value Ceiling Effect P Value

Skewness Kurtosis

1 0 (0)

1.0

13 (21)

0.025

–0.58 4.0

2 1 (1.4) 14 (20)

–1.7 13

3 0 (0) 23 (34)

–3.0 14

4 0 (0) 7 (12)

–1.0 5.0

Note: Discrete variables reported as number (%).

Original Research

www.mdedge.com/jcomjournal Vol. 27, No. 1 January/February 2020 JCOM 47

The NPS varied substantially based on scale struc-

ture. Increasing the spread of the scores to limit the

ceiling effect will likely reduce promoters and detractors

and increase neutrals. NPS systems have been used in

the past to measure patient satisfaction with common

hand surgery techniques and with community mental

health services.

25,26

These studies suggest that NPS

could be a helpful addition to commonly used clinical

measures of satisfaction, after more research has been

done to validate it. The evidence showing that NPS are

strongly influenced by scale structure suggests that

NPS should be used and interpreted with caution.

Several caveats regarding this study should be kept

in mind. This study specifically addressed ratings of visit

helpfulness. Differently phrased questions might lead

to different results. More work is needed to determine

the essence of satisfaction with a medical visit.

1

In addi-

tion, the majority of our patient population was white,

employed, and privately insured, limiting generalizabil-

ity to other populations with different demographics.

Finally, all patients were seen by an orthopedic surgeon,

and our results might not apply to other populations or

clinical settings. However, given the scope of this study,

we suspect that the findings can be generalized to

specialty care in general and likely all medical contexts.

Conclusion

It is clear from this work that scale design can affect ceil-

ing effect. We plan to test alternative phrasings and struc-

tures of single-question measures of satisfaction with a

medical visit so that we can better study what factors

contribute to satisfaction. It is notable that this approach

runs counter to efforts to improve satisfaction scores,

because reducing the ceiling effect reduces the mean

score and may contribute to worse NPS. Further study is

needed to find the optimal measure to assess satisfaction

ratings.

Corresponding author: David Ring, MD, PhD, 1701 Trinity Street,

Austin, TX, 78712; david.ring@austin.utexas.edu.

Financial disclosures: Dr. Ring has or may receive payment or

benefits from Skeletal Dynamics; Wright Medical Group; the journal

Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research; and universities, hos-

pitals, and lawyers not related to the submitted work.

References

1. Waters S, Edmondston SJ, Yates PJ, Gucciardi DF. Identification of

factors influencing patient satisfaction with orthopaedic outpatient

clinic consultation: A qualitative study. Man Ther. 2016;25:48-55.

2. Kortlever JTP, Ottenhoff JSE, Vagner GA, et al. Visit duration does

not correlate with perceived physician empathy. J Bone Joint Surg

Am. 2019;101:296-301.

3. Edwards P, Roberts I, Clarke M, et al. Methods to influence

response to postal questionnaires. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

2001(3):CD003227.

4. Salisbury C, Burgess A, Lattimer V, et al. Developing a standard

short questionnaire for the assessment of patient satisfaction with

out-of-hours primary care. Fam Pract. 2005;22:560-569.

5. Ross CK, Steward CA, Sinacore JM. A comparative study of seven

measures of patient satisfaction. Med Care. 1995;33:392-406.

6. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data

capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow

process for providing translational research informatics support. J

Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377-381.

7. Medicine USNLo. ClinicalTrials.gov. Accessed March 18, 2019.

8. Nicholas MK, McGuire BE, Asghari A. A 2-item short form of the

Pain Self-efficacy Questionnaire: development and psychometric

evaluation of PSEQ-2. J Pain. 2015;16:153-163.

9. Salkovskis PM, Rimes KA, Warwick H, Clark D. The Health Anxiety

Inventory: development and validation of scales for the mea-

surement of health anxiety and hypochondriasis. Psychol Med.

2002;32:843-853.

10. Schalet BD, Pilkonis PA, Yu L, et al. Clinical validity of PROMIS

depression, anxiety, and anger across diverse clinical samples. J

Clin Epidemiol. 2016;73:119-127.

11. Ho AD, Yu CC. Descriptive statistics for modern test score distri-

butions: skewness, kurtosis, discreteness, and ceiling effects. Educ

Psychol Meas. 2015;75:365-388.

12. Kim HY. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: assessing normal

distribution (2) using skewness and kurtosis. Restor Dent Endod.

2013;38:52-54.

13. NICE Satmetrix. What is net promoter? https://www.netpromoter.

com/know/. Accessed March 18, 2019.

14. Terwee CB, Bot SD, de Boer MR, et al. Quality criteria were pro-

posed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires.

J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:34-42.

15. Hasson D, Arnetz BB. Validation and findings comparing VAS vs.

Likert scales for psychosocial measurements. Int Electronic J Health

Educ. 2005;8:178-192.

16. Vickers AJ. Comparison of an ordinal and a continuous outcome

measure of muscle soreness. Int J Technol Assess Health Care.

1999;15:709-716.

17. Jaeschke R, Singer J, Guyatt GH. A comparison of seven-point and

visual analogue scales: data from a randomized trial. Control Clin

Trials. 1990;11:43-51.

18. Voutilainen A, Pitkaaho T, Kvist T, Vehvilainen-Julkunen K. How to

ask about patient satisfaction? The visual analogue scale is less vul-

nerable to confounding factors and ceiling effect than a symmetric

Likert scale. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72:946-957.

19. Brunelli C, Zecca E, Martini C, et al. Comparison of numerical and

verbal rating scales to measure pain exacerbations in patients with

chronic cancer pain. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:42.

20. Hageman MG, Briet JP, Bossen JK, et al. Do previsit expectations

correlate with satisfaction of new patients presenting for evaluation

with an orthopaedic surgical practice? Clin Orthop Relat Res.

2015;473:716-721.

Measures of Patient Satisfaction

48 JCOM January/February 2020 Vol. 27, No. 1 www.mdedge.com/jcomjournal

21. Keulen MHF, Teunis T, Vagner GA, et al. The effect of the content

of patient-reported outcome measures on patient perceived

empathy and satisfaction: a randomized controlled trial. J Hand

Surg Am. 2018;43:1141.e1-e9.

22. Mellema JJ, O’Connor CM, Overbeek CL, et al. The effect of

feedback regarding coping strategies and illness behavior on hand

surgery patient satisfaction and communication: a randomized

controlled trial. Hand. 2015;10:503-511.

23. Tyser AR, Gaffney CJ, Zhang C, Presson AP. The association

of patient satisfaction with pain, anxiety, and self-reported

physical function. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018;100:1811-1818.

24. Vranceanu AM, Ring D. Factors associated with patient satisfac-

tion. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36:1504-1508.

25. Stirling P, Jenkins PJ, Clement ND, et al. The Net Promoter Scores

with Friends and Family Test after four hand surgery procedures.

J Hand Surg Eur. 2019;44:290-295.

26. Wilberforce M, Poll S, Langham H, et al. Measuring the patient

experience in community mental health services for older people:

A study of the Net Promoter Score using the Friends and Family

Test in England. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;34:31-37.

JCOM is seeking submissions of original research and descriptive reports of quality improvement projects.

Original research submissions can include reports of investigations that address questions about clinical care or the

organization of health care and its impact on outcomes.

Descriptions and evaluations of quality improvement efforts will be considered

for JCOM’s “Reports from the Field” section. The section features reports on

actions being taken to improve quality of care. Such reports may include, but

are not limited to, the following items:

• Motivation for the project, including the role of research ndings

or internal or external benchmarking data

• Setting/demographics

• Intervention/implementation process

• Measurements

• Results

• Similarities to other approaches studied, limitations, applicability

in other settings, etc.

Approximate length is 4000 words. Papers submitted are sent for peer review.

Decisions about manuscripts are made within 8 weeks of receipt. Information

for authors may be found at www.mdedge.com/jcomjournal.

If you are interested in submitting a paper, contact:

Robert Litchkofski, Editor

Call for Contributions