Kutztown University Kutztown University

Research Commons at Kutztown University Research Commons at Kutztown University

Social Work Doctoral Dissertations Social Work

Spring 5-12-2023

School Social Work and Autism Competency: A Mixed-Methods School Social Work and Autism Competency: A Mixed-Methods

Assessment of Pennsylvania School Social Workers Assessment of Pennsylvania School Social Workers

Jami Imhof

Kutztown University of Pennsylvania

Follow this and additional works at: https://research.library.kutztown.edu/socialworkdissertations

Part of the Social Work Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Imhof, Jami, "School Social Work and Autism Competency: A Mixed-Methods Assessment of

Pennsylvania School Social Workers" (2023).

Social Work Doctoral Dissertations

. 27.

https://research.library.kutztown.edu/socialworkdissertations/27

This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Social Work at Research Commons at Kutztown

University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Social Work Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator

of Research Commons at Kutztown University. For more information, please contact [email protected].

School Social Work and Autism Competency: A Mixed-Methods Assessment of Pennsylvania

School Social Workers

A Dissertation Presented to

the Faculty of the Doctor of Social Work Program of

Kutztown University|Millersville University of Pennsylvania

In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Social Work

By Jami Imhof, LCSW-C

March 2023

Autism Competency for School SW

2

This Dissertation for the Doctor of Social Work Degree

by Jami Imhof

has been approved on behalf of

Kutztown University|Millersville University

Dissertation Committee:

___________________ ________________________

Dr. Janice Gasker, Committee Chair

___________________________________________

Dr. Mary Rita Weller, Committee Member

____________________________________________

Dr. John Vafeas. Committee Member

____________________________________________

Dr. Steve Lem. Committee Member

March 22, 2023

Autism Competency for School SW

3

ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION

School Social Work and Autism Competency: A Mixed-Methods Assessment of Pennsylvania

School Social Workers

By Jami Imhof, LCSW-C

Kutztown University|Millersville University, 2023

Directed by Dr. Janice Gasker

Autism is a neurodevelopmental disorder which currently affects 1 in 44 individuals in the

United States. Autism manifests as symptoms that impact the areas of communication, social

interaction, and behavior (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020). Symptoms may

create challenges in the school setting, requiring social work intervention. School social workers

must be knowledgeable about autism as well as how to best support autistic students. A mixed

methods study was conducted among 84 school social workers in Pennsylvania to understand

current autism knowledge via an online survey. Ways in which social workers have learned

about autism, as well as what they need to support autistic students was explored through

responses to qualitative items on the survey. Scores on the 10 point abbreviated ASDKP-R

ranged from 20% to 100% (M=62.7, SD=15.7). While a below average score was revealed, most

participants (n=63) indicated that they would like to increase their knowledge and skills

regarding autism related topics.

Keywords: school social work, autism, neurodiversity

Autism Competency for School SW

4

DEDICATION

This dissertation is dedicated to all first-generation college graduates who have persevered to

obtain their degree.

Autism Competency for School SW

5

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I will be forever grateful for stumbling across the KU DSW program while searching for

online DSW options. Pursuing a doctoral degree was something that I contemplated for years;

Kutztown University allowed the opportunity for that to happen. I want to acknowledge and

thank the professors in the program; each one has been so encouraging during this journey. A

special thank you to my dissertation chair, Dr. Janice Gasker. I appreciate your support with not

only my dissertation work, but with presentations and publications as well. Thank you to my

dissertation committee members, Dr. Mary Rita Weller and Dr. John Vafeas; I appreciate our

conversations on school social work and supporting disabled students. I want to also thank Dr.

Steve Lem, who assisted with the survey design and quantitative analysis of my research.

To the DSW cohort, you all are amazing! I truly appreciate each one of you. I cannot wait

to see what you accomplish after graduation. I look forward to reading your publications and

attending your conferences. I know you all will do big things!

To my husband, Chris – thank you for all of your support over the last three years. I

appreciate all the times you entertained the kids so that I could have a quiet house and

concentrate on schoolwork. To my children, Klarissa and Franz, you both are so patient and

caring! I love all of the pictures you have drawn for my desk, so I could look at them while I was

either writing or in an online class. Now that I am finished with school, we have a lot more time

for fun things! And lastly, to my cat, Kiki – she usually made an appearance while I was in an

online class, or sat on my lap while I was working on the computer. She was by my side

throughout the entire DSW program.

Autism Competency for School SW

6

Table of Contents

List of Tables and Figures .............................................................................................................8

Chapter 1: Introduction to Autism and School Social Work ...................................................9

Introduction ..................................................................................................................................9

Roles of School Social Workers ................................................................................................14

Statement of Purpose ..................................................................................................................19

Problem Statement .....................................................................................................................19

Overview of Methodology .........................................................................................................20

Reflexivity Statement .................................................................................................................21

Chapter 2: Literature Review .....................................................................................................22

Introduction ................................................................................................................................22

Training of Social Workers ........................................................................................................22

Clinical Strategies ......................................................................................................................26

Existing Tools and Certifications ...............................................................................................27

Theoretical Framework ..............................................................................................................31

Gaps in Literature .......................................................................................................................37

Conclusion and Implications ......................................................................................................38

Chapter 3: Methodology..............................................................................................................40

Introduction ................................................................................................................................40

Research Design .........................................................................................................................41

Research Setting .........................................................................................................................41

Research Participants .................................................................................................................42

Recruitment ................................................................................................................................43

Data Collection Methods ............................................................................................................45

Data Analysis .............................................................................................................................48

Limitations .................................................................................................................................49

Positionality Statement ...............................................................................................................50

Chapter 4: Findings .....................................................................................................................52

Introduction ................................................................................................................................52

Participant Demographics ..........................................................................................................52

Research Question 1 ...................................................................................................................57

Research Question 2 ...................................................................................................................65

Research Question 3 ...................................................................................................................68

Autism Competency for School SW

7

Summary ....................................................................................................................................71

Chapter 5: Analysis and Synthesis .............................................................................................72

Introduction ................................................................................................................................72

Note on Honoring Autistic Voices .............................................................................................72

Motivation for Learning .............................................................................................................73

Certifications and Licensure .......................................................................................................74

Higher Education ........................................................................................................................76

Continuing Education .................................................................................................................77

Professional Experience .............................................................................................................80

Autism Knowledge .....................................................................................................................81

Summary ....................................................................................................................................83

Chapter 6: Conclusion and Recommendations .........................................................................85

Introduction ................................................................................................................................85

Recommended Autism Competencies for Social Workers ........................................................85

Recommended Learning Opportunities .....................................................................................92

Conclusion .................................................................................................................................96

References .....................................................................................................................................96

Appendix A: Survey Instrument – Consent Form ..................................................................108

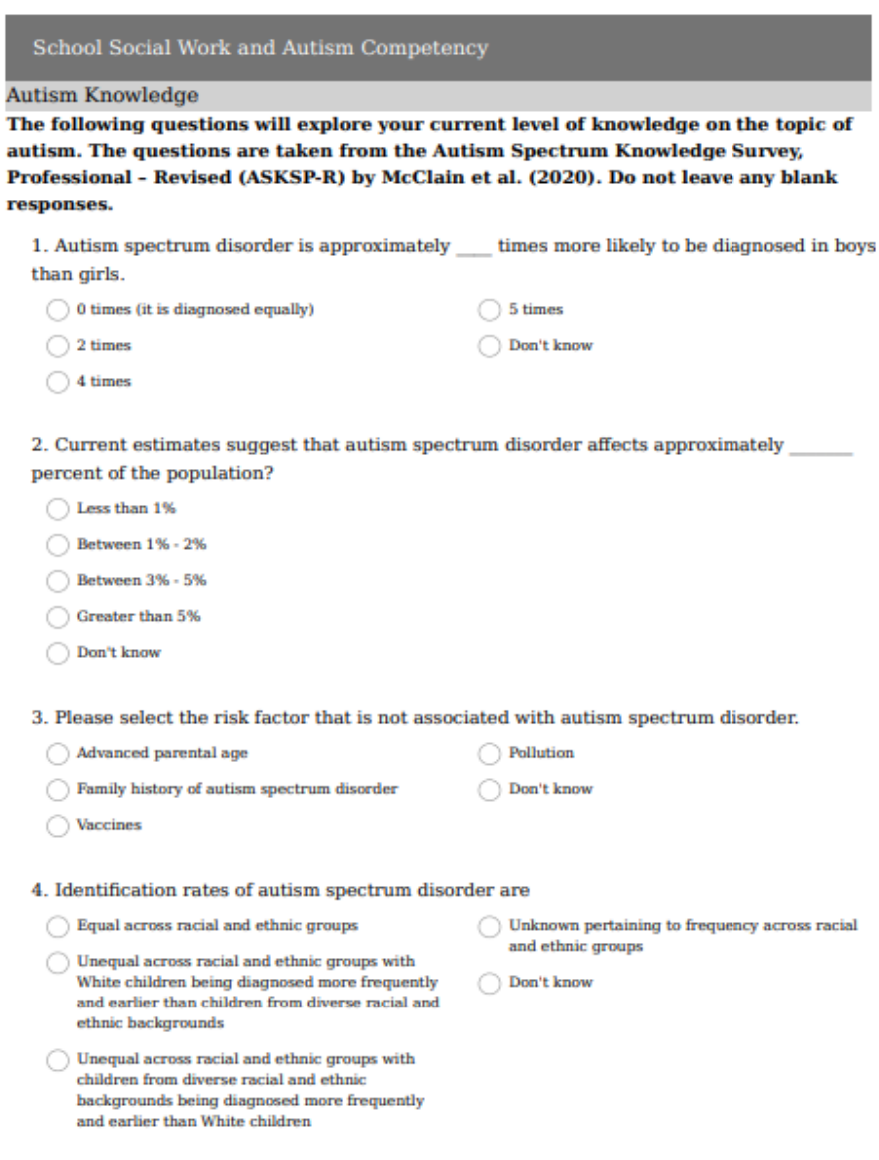

Appendix B: Survey Instrument – Abbreviated ASKSP-R ...................................................111

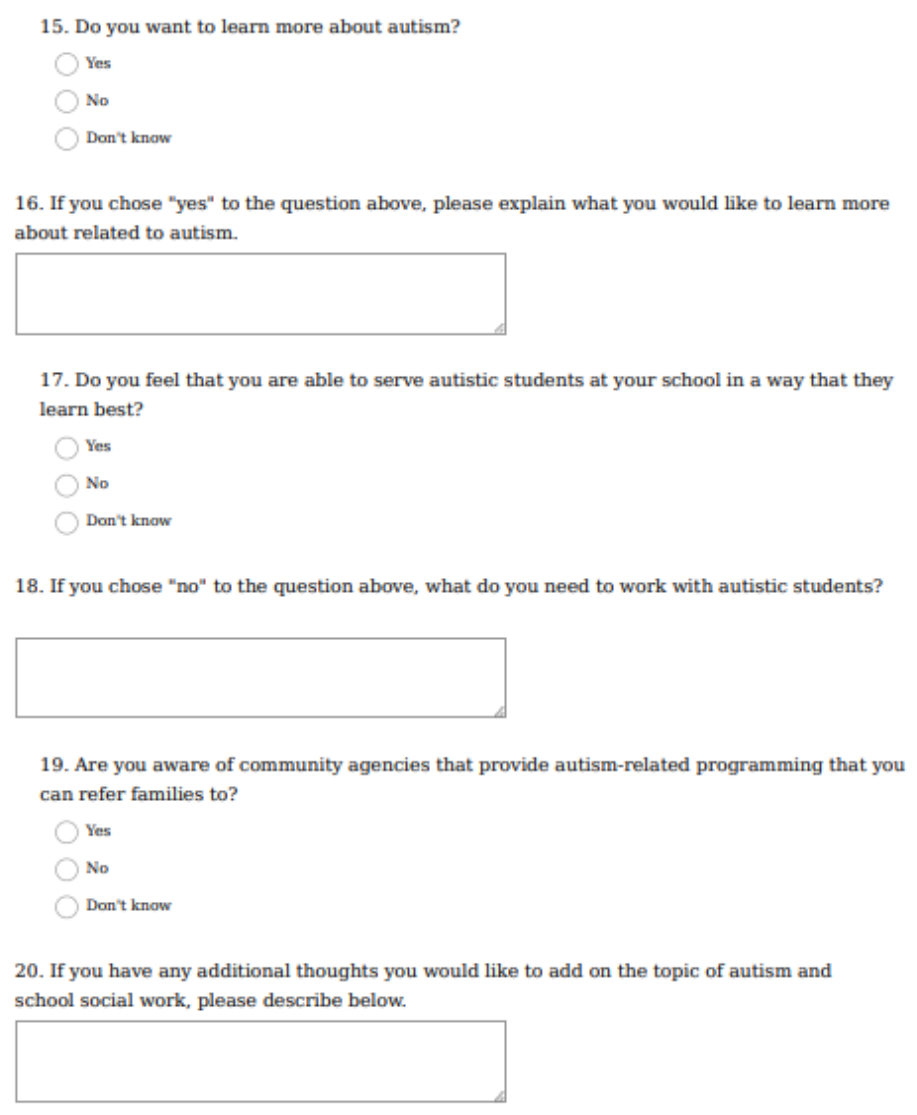

Appendix C: Survey Instrument – Autism Experience ..........................................................113

Appendix D: Survey Instrument – Participant Demographics .............................................115

Appendix E: IRB Approval Form ............................................................................................117

Appendix F: Recruitment Email ..............................................................................................119

Appendix G: IRB Letter from Momentive ..............................................................................120

Autism Competency for School SW

8

List of Tables and Figures

Figure 1: Theoretical Framework for Autism Competency in the School Social Work

Setting............................................................................................................................................32

Table 1: Participant Gender .......................................................................................................53

Table 2: Participant Age .............................................................................................................53

Table 3: Educational Levels of Study Participants ...................................................................54

Figure 2: Additional Certificates Held by Participants............................................................54

Table 4: Current Participant Social Work Licensure ..............................................................56

Figure 3: Reported Personal Connection to Autism .................................................................57

Figure 4: ASKSP-R Score Distribution .....................................................................................58

Figure 5: Distribution of Total Years in Social Work and Score ............................................60

Table 5: Descriptive Statistics – Total Years in Social Work, ASKSP-R Score ....................60

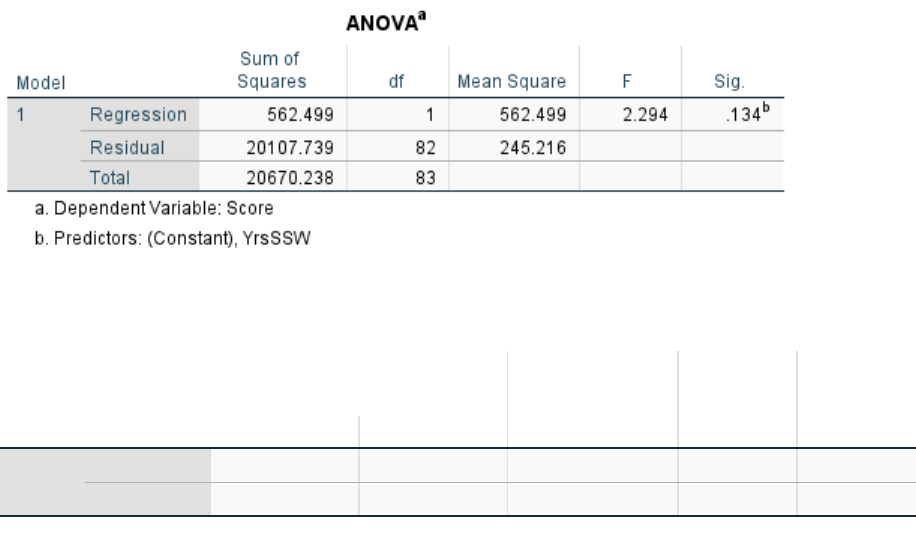

Table 6: Regression Model – Total Years in Social Work, ASKSP-R Score..........................61

Figure 6: Total Years of School Social Work Experience and Score ......................................63

Table 7: Descriptive Statistics – Total Years in School Setting, ASKSP-R Score .................63

Table 6: Regression Model – Total Years in School Setting, ASKSP-R Score ......................64

Figure 7: Methods of Learning About Autism ..........................................................................66

Figure 8: Professional Experience Serving Autistic Students .................................................67

Figure 9: Themes Identified Among Social Work Needs .........................................................69

Figure 10: nVivo Word Cloud, Social Work Learning Needs .................................................79

Autism Competency for School SW

9

Chapter 1: Introduction

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Autism Spectrum Disorder

(ASD), or autism, is a neurodevelopmental disorder which currently affects 1 in 44 individuals in

the United States. Autism manifests as symptoms that impact the areas of communication, social

interaction, and behavior (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020). Symptoms may

create challenges in the school setting, requiring social work intervention.

To support autistic

1

students in the school setting, a competent understanding of autism

must be a part of the social worker’s skillset. Understanding the symptoms of autism, challenges

that may require social work intervention, and evidenced-based interventions to serve autistic

students allow a social worker to appropriately serve autistic students in the school setting.

Overview of Autism

Understanding how autism affects a student in the school setting is a part of supporting

healthy development. Being knowledgeable of symptoms of autism, diagnostic criteria, as well

as differences in how autism manifests in males and females are some of the components that

can create competence for a school social worker in addressing the needs of autistic students.

History of Autism. In the 1940’s, Leo Kanner began to diagnose children with autism in

Baltimore, Maryland; he documented eleven cases of children and teenagers who displayed

symptoms of the disorder (Parisi & Parisi, 2019). There have been documented cases in 1700’s

(“feral” children who most likely wandered away from home) and 1800’s (at a school for

developmental disabilities), but Kanner’s work was the first in the United States that provided

1

Self-advocacy groups, such as the Autistic Self Advocacy Network (ASAN), have stated preference for identity-first

usage (Brown, 2011). The APA Publication Manual states that it can be “permissible to use” identity-first language

when a group states preference (American Psychiatric Association, 2020, p. 137).

Autism Competency for School SW

10

detailed features and characteristics of the disorder (Rosen, et al., 2021). Kanner, a

psychotherapist at Johns Hopkins University, coined the term autism from the Greek word autos,

or self, to describe the social withdrawal he observed in his patients (Al Ghazi, 2018).

During the same time period, Hans Asperger worked in Germany, where he diagnosed

children with autism; his work is controversial due to his referrals of patients to Nazi German

clinics. Asperger and a clinician who worked with him, George Frankl, were the first to write

about high functioning autism, or what is referred today as level one autism (low support needs)

in terms of an autism diagnosis (Muratori, et al., 2021). Asperger referred to his patients as

having autistic pathology and drew similarities to schizophrenia due to the symptoms of social

withdrawal. He also noted that other characteristics were not reminiscent of schizophrenia

(absence of hallucinations), and he was able to observe symptoms in children as young as two

years of age (Al Ghazi, 2018). As the field of child psychiatry grew in the 1960’s, researchers

focused on the area of autism and etiology. In the 1970’s, child psychiatrist Michael Rutter

conducted the first genetic study of autism in the United Kingdom. Rutter also described the

three main areas that were affected by autism: communication, social interactions, and behavior

(Evans, 2013). Work by psychiatric researchers in the mid-20

th

century led to autism being

included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders in the latter part of the

century.

Autism in Previous DSM Editions. Autism first appeared in the Diagnostic and Statistical

Manual of Mental Disorders, 3

rd

edition, in 1980. With the removal of childhood schizophrenia,

a category of pervasive developmental disorders was introduced, which included a diagnosis of

infantile autism (Evans, 2013). When the text revision was published in 1987, autistic disorder

replaced infantile autism, to reflect the disorder across the lifespan. In the DSM-III-TR,

Autism Competency for School SW

11

diagnostic criteria were included in three main categories: qualitative impairments in reciprocal

social interaction; impairments in communication; and restricted interests/resistance to change

and repetitive movements (American Psychiatric Association, 1987).

With the 1994 publication of the DSM-IV, as well as the text revision in 2000,

Asperger’s disorder and pervasive developmental disorder were included as individual diagnoses

under the umbrella of autism spectrum disorders. Asperger’s disorder was added as a result of

documented cases of differences among patients with a diagnosis of pervasive developmental

disorder and autism (Rosen, et al., 2021). Asperger’s disorder was differentiated from autism

disorder, as there were no delays in communication, which would otherwise be observed in

autism. The disorder was also noted to consist of social interaction difficulties and restricted

interests, with the absence of cognitive delays (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). While

a patient could experience difficulties in social and occupational settings, it was viewed more

positively compared to autism, which was (and is) stigmatized as a “significant disability”

(Hosseini & Molla, 2021).

Autism in the DSM-5 and Text Revision. Autism is a neurodevelopmental disorder which

affects 1 in 44 individuals in the United States; males are diagnosed at a rate four times higher

than females. There is no singular cause of autism, but research suggests a strong genetic

component. Other risk factors include the presence of some chromosomal abnormalities (such as

Fragile X syndrome), birth complications, parents conceiving at an older age (CDC does not

specify age considered to be older), as well as having an autistic sibling (Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention, 2020). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5

th

edition (DSM-5) states that a person must have deficits in the areas of social interaction,

communication, and behavior to be diagnosed with autism. Social interaction deficits include

Autism Competency for School SW

12

developing and maintaining relationships as well as difficulty with social-emotional reciprocity.

Due to restricted interests, an autistic individual may be more concerned with discussing their

interests, rather than being engaged in a reciprocal conversation about another person’s interests.

An autistic person may not initiate social interactions or continue to engage in an interaction or

activity. Children may be observed to be engaged in parallel play; rather than interacting in a

cooperative activity, they may play in the same physical space as another child but be engaged in

a solitary activity (American Psychiatric Association, 2022).

Communication deficits manifest in receptive and expressive verbal and nonverbal

language. Autistic individuals often have difficulty recognizing social cues such as gestures and

facial expressions. They may also have difficulty understanding verbal communication styles

such as metaphors and sarcasm. Behavior deficits include four different types: repetitive

behaviors, fixed interests, difficulty with transitions, as well as sensory issues. Repetitive

behaviors consist of self-stimulatory behaviors, or stimming, which may look like hand-flapping,

making repetitive vocalizations, or twirling in circles while walking. While neurotypical people

may also stim (such as bouncing a leg while sitting, or clicking a pen), autistic stimming may be

more noticeable to a stranger who is unfamiliar with the autistic individual. Fixed interests may

dominate a conversation, but can also consume time and thoughts, with other topics or activities

being uninteresting to a person. An autistic individual becomes an “expert” of their interest as

they may read or watch media related to their topic. Autistic individuals may also prefer a

predictable routine and may exhibit emotional and behavioral difficulty with an unexpected or

unplanned change in routine. Sensory issues can manifest as hyposensitivity or hypersensitivity,

with autistic individuals becoming overstimulated (or under stimulated) in certain environments

(American Psychiatric Association, 2022).

Autism Competency for School SW

13

Symptom severity is also outlined by the DSM (American Psychiatric Association,

2013). Although there is previous literature that refers to high-functioning autism and low-

functioning autism, self-advocacy groups caution against referring to the levels as mild,

moderate, or severe, due to the misconceptions and stigma that may come from labeling

individuals as such.

While only two out of the four behavior challenges must be experienced to receive a

diagnosis, all of the social and communication deficits must be experienced. Revisions to the

DSM-5 were released in 2022, including minor revisions to autism criteria. Previously, in the

DSM-5, autism diagnostic criteria stated that the symptoms are persistent and manifested by the

categories described above. DSM-5 TR created a minor change to language including symptoms

should be manifested in all categories, in an effort to clarify diagnostic criteria (American

Psychiatric Association, 2022). When the DSM-5 was published in 2013, the previous individual

diagnoses were condensed under a single diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder. Symptoms are

categorized into three levels of severity which are dependent on low, moderate, or high levels of

support that is needed. Level 1 indicates that an individual would require support and may

experience difficulties with some changes in their routine or difficulties with social interaction

skills. Level 2 symptoms would require substantial support, and behaviors may be noticed by

someone who is otherwise unfamiliar to the autistic individual. Level 3 symptoms require very

substantial support, with the autistic individual experiencing behaviors that would impact their

daily functioning (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The DSM-5-TR does not define

what support looks like for autistic individuals diagnosed at each of the three levels.

Autism in Females. While the DSM notes that the symptoms should be present early in life, it is

not uncommon for a person, especially females, to receive an autism diagnosis in adulthood.

Autism Competency for School SW

14

Females are more likely to mask or camouflage symptoms of autism in an attempt to fit in

socially. A female is more likely to attempt to hide, or mask, autistic characteristics in an attempt

to appear neurotypical and gain acceptance by peers. Females with autism may experience

difficulties with decoding subtle behaviors and nuances in language; these difficulties can make

autistic females stand out from neurotypical peers (Cook, et al., 2017). The sole act of masking

can also create anxiety due to the emotional toll of attempting to appear neurotypical. Males

tend to externalize symptoms more frequently, such as experiencing behavioral outbursts when

frustrated or a higher incidence of maladaptive behaviors (such as self-injurious behaviors).

Females are more likely to internalize their challenges, resulting in depression or anxiety. Due to

the differences in how symptoms are manifested, males are more likely to draw attention and be

diagnosed earlier compared to females (Hull et al., 2020). Females who are diagnosed at a

younger age may display a delay in development, such as communication. Those diagnosed at

later ages may not require a high level of behavior or communication support, but may display

difficulties with social interactions, compared to their peers (Corscadden & Casserly, 2021).

Roles of School Social Workers

School social workers can be found in a variety of educational settings, including public,

nonpublic, private, and residential schools. Autistic students may attend any of these settings;

some students may have an existing diagnosis, while others may not yet be diagnosed as autistic.

Understanding the social work values that guide all licensed social work practice can help to

inform school social work as well. Social work standards for practice in the school setting are

outlined by the National Association of Social Workers, as well as the National Practice Model

by the School Social Work Association of America. The guidelines by the organizations provide

role clarification in addition to the job duties outlined by individual jurisdictions.

Autism Competency for School SW

15

Social Work Values. The National Association of Social Workers (NASW) established a Code

of Ethics in 1960 as a guideline for an ethical professional framework for social workers.

According to the preamble of the code, the core values of the social work profession are “service,

social justice, dignity and worth of the person, importance of human relationships, integrity, and

competence” (NASW, n.d.). The core values reflect the work that is done by practitioners, but

having an established code that is guided by specific values helps to focus practitioners’ work in

the field. Creating a code and declaring values that are important to the field of social work also

create a more cohesive profession by stating shared professional values. When social workers

hold the above stated values in high regard and with fidelity, others (including clients) can expect

consistency in the professional behavior of the practitioner.

Familiarizing oneself with the NASW Code of Ethics can help social work students to

form professional identities before officially serving clients as a licensed social worker. Since the

Code of Ethics applies to licensed social workers nationwide, a social work student will be able

to learn about expectations of professional social work behavior no matter which university they

have attended.

NASW School Social Work Standards. The National Association of Social Workers (NASW)

has created standards for school social workers to clearly define their roles in the school setting.

The standards collectively outline responsibilities that social workers may have in their school

building, above and beyond the roles dictated by their individual job description. Ethics and

values state licensed social workers employed in a school setting are expected to adhere to the

values of the field and abide by the NASW Code of Ethics in their work with students. Through

the standard of qualifications, it is recommended that school social workers hold an MSW

Autism Competency for School SW

16

degree from a CSWE-accredited program. Jurisdictions may have varying qualifications, such as

advanced licensure or certification, above and beyond the required MSW degree (NASW, 2012).

NASW standards also dictate that school social workers conduct assessments to support

the student and their social, emotional, behavioral, and academic success in the school setting.

This may take the form of classroom observations to gather behavioral data for a Functional

Behavior Assessment or interviewing a parent to collect information about a child’s strengths

and needs. Once information is collected, a social work intervention in the school setting may be

found appropriate. Social workers must be aware of current evidenced-based practices to use

individually with students as well as the school environment as a whole. Another standard to

consider as school social work role includes decision making and practice evaluation. Data

collected by the school social worker will be used to justify goals and interventions used in the

school setting (NASW, 2012). For example, a social worker who proposes a social interaction

goal on a student’s Individualized Education Plan (IEP) should provide data to justify the goal

and school-based interventions for achieving the goal.

A standard of record keeping in the school building stipulates social workers will

maintain “timely, accurate and confidential records” relevant to the students on their caseload

(NASW, 2012, p.10). Social workers should be aware of any state and local policies related to

maintaining student records. Workload management reminds social workers to manage their time

during the school day in an efficient manner, addressing priorities while continuing to carry out

other duties as assigned (NASW, 2012).

The standard of professional development dictates that a school social worker participates

in training to enhance professional skills. NASW outlines a standard of cultural competence

which states a social worker develop specialized knowledge and understanding of client groups

Autism Competency for School SW

17

they serve (NASW, 2012). A school social worker has the opportunity to work with a multitude

of groups that have unique needs, including autistic students. It would be likely impossible for a

school social worker to become an expert on all groups of students in the school setting but

gaining a basic (or in their career, advanced) knowledge of autism can create impact on autistic

students’ needs in the school setting. Being a culturally competent social worker encompasses

awareness and knowledge of disabilities, including autism. Some of the ways providers can

improve upon their competence in serving clients with disabilities included training, as well as

exploring beliefs about the population that is served, as well as exploring any stigma (Butler, et

al., 2016). Stereotyping and assumptions may be made by a social worker due to a lack of

knowledge or experience around autism; by increasing educational opportunities in this area,

clients can be served with respect and competence. NASW also encourages social workers to

engage in interdisciplinary leadership and collaboration. To effectively serve autistic students,

social workers must collaborate with other service providers; related services (such as speech or

occupational therapy services) in the school setting, as well as community providers, can provide

information for the student’s intervention plan. By asserting oneself as a leader in the school

community, the school social worker may provide training on a topic that may help to serve the

student. Lastly, social workers are expected to advocate in the school setting, not only for their

students but for fair and just school policies (NASW, 2012).

National School Social Work Practice Model. School social work is a specialized area in which

some jurisdictions require certification to work within the school setting. According to the

School Social Work Association of America (SSWAA), the role of a school social worker may

include participating in special education meetings, delivering counseling services, modeling

Autism Competency for School SW

18

social interaction skills, referring parents to community programs, and providing case

management services (SSWAA, 2020).

SSWAA has created a national model for school social work in an effort to establish roles

within a school setting, as well as to create consistent practices across undergraduate and

graduate education as well as for professional social workers in the field (Frey et al., 2013). The

model states that there are three main practice areas, each practice area encompassing various

roles for a school social worker.

The first practice area consists of providing “evidence-based education, behavior, and

mental health services” (Frey et al., 2013, p. 132). Similar to the NASW standard of intervention,

the practice model advises school social workers to evaluate interventions with students for

efficacy. Social workers must be able to justify using an intervention to target a goal for students.

The second practice area suggests that school social workers are responsible for promoting a

school climate which promotes an environment that fosters academic success (Frey et al, 2013).

School social workers may find themselves on multidisciplinary teams that work to create

positive school climates.

The last practice area, according to the national model, is to connect students and families

with resources, both within the school and the community (Frey et al., 2013). Because social

workers may provide case management services, when necessary, knowledge of resources within

the school jurisdiction as well as in the community is needed. School social workers may be in a

position to refer students and families to resources when there is some kind of crisis (such as

homelessness) or a new diagnosis that a student and family is learning to navigate.

Autism Competency for School SW

19

Statement of Purpose

Social work students as well as professional social workers must have exposure to autism

information to be prepared to serve autistic clients. Social work education can improve in

preparing competent social workers for field work by exposing them to the information needed

to serve clients (Williams & Haranin, 2016). The goals and outcomes of this study have

implications on the area of social work education – both at the university level and continuing

education opportunities for licensed social workers in the field. About 3% of licensed social

workers specialize in serving clients with a developmental disability (Haney & Cullen, 2018).

An increase in educational opportunities focusing on developmental disabilities (such as autism)

could help to attract more social workers to serve this population.

Problem Statement

There is a lack of research focusing specifically on school social workers who serve

students with an autism diagnosis (Oades, 2021). School social workers are in a unique situation

because they offer both clinical and case management services to students and families.

Professional education can be a path for school social workers to acquire knowledge and skills to

serve autistic clients, but the opportunities must exist. Hesitation to serve autistic clients has also

been documented. Social workers who have had professional or personal (such as a friend or

family member) interaction with a disabled client, or have taken a university course on disability,

scored higher on scales measuring attitudes towards the population. Social workers who do not

have knowledge or lack interactions with the population may continue to express negative

attitudes and beliefs of working with autistic clients (Holler & Werner, 2018).

Autism Competency for School SW

20

The study collected survey data (both quantitative and qualitative) on school social

workers’ competency on the topic of autism. Using competencies developed for school social

workers as a guide for survey development, the aim of the study is to answer the following

questions:

1. What is the social worker’s current level of knowledge on the topic of autism?

2. How have social workers learned about autism?

3. What knowledge and/or skills are needed for school social workers to effectively

serve their autistic students?

Survey responses can fill gaps in knowledge that are needed for social workers to serve

their autistic students. The responses may also demonstrate the need for autism education, both at

the university level for students and professional continuing education for practicing social

workers. Responses gathered from survey participants may also have an impact on curriculums

for school social work certification programs.

Overview of Methodology

Through the use of survey research, this writer will evaluate how knowledge on autism

has been gained (personal experience, formal classes, work experience, etc). Survey questions

developed will be based on the Questionnaire on Autism (Mavropoulou & Padeliadu, 2000) and

the ASD Knowledge Questionnaire (Giannopulou et al., 2019). The results of the study may have

some impact regarding the need for educational opportunities for social work students and

licensed social workers who are practicing in the field. Understanding how social workers gain

that knowledge, especially the opportunities for education, are crucial to ensuring that the field of

social work has adequate opportunities for education on the topic of autism.

Autism Competency for School SW

21

Research participants will be licensed school social workers in the state of Pennsylvania,

where this writer’s university is located. This writer has no conflict of interest with participants,

due to residing and working in another state. Surveys will be sent to social workers via email,

using mailing lists made available to this writer. Responses will be anonymous; the writer will

not be able to see which email addresses are associated with individual responses.

Reflexivity Statement

This writer is a licensed, clinical social worker who has worked in the Baltimore-

Washington, DC metropolitan area since 2007. The majority of this writer’s professional

experience has been in a variety of school settings, including a nonpublic special education

school located on the campus of a residential group home setting, two nonpublic special

education schools, and a public school.

As a school social worker, this writer has served students on the autism spectrum since

2011. They also have a young, autistic nephew. Throughout the autism community, there is a

preference for identity-first (autistic student) language, rather than person-first (student with

autism) language. In the past, this writer has used person-first language when referring to

students. After reading more literature written by autistic authors and providers, this writer has

learned why identity-first language is important to this particular group. Self-advocacy groups,

such as the Autistic Self Advocacy Network (ASAN), have stated preference for identity-first

usage (Brown, 2011). This writer does not identify as autistic, but in an effort to respect autistic

voices, identity-first language will be used throughout this paper.

Autism Competency for School SW

22

Chapter 2: Literature Review

Introduction

The following chapter includes a synthesis of existing literature on the topics of how

social workers are trained, clinical strategies utilized in school social work, as well as existing

measurement tools and professional certifications available. The researcher will also present the

theoretical framework which guides the research study in this dissertation.

A literature review of professional journals was conducted using the EBSCO and Google

Scholar search engines. Keywords included social work, school, autism, neurodiversity, special

education, counseling, mental health. Boolean operators AND/OR were applied to keywords;

publication date was not limited to a specific range. There is a lack of existing literature specific

to autism and school social workers; due to this issue, articles related to autism and K-12

education in general appeared more frequently compared to school social work and autism.

Training of Social Workers

With the current rate of autism in the United States, a school social worker is at an

increased chance of interacting with a student that has autism; because a social worker in the

school setting may work with both general education and special education students, a competent

understanding of autism must be a part of the social worker’s working knowledge. Social work

students must have exposure to understanding developmental disorders such as autism, as well as

practicing social workers who may be serving autistic clients. Social work education can

improve in preparing competent social workers for field work by exposing them to the

information needed to serve clients; continuing education opportunities can also be an option for

practicing social workers to improve their autism competency.

Autism Competency for School SW

23

Autism Education in Higher Education. Training in the area of autism for social workers can

come through formal education or professional experience. A social worker may be better

prepared for some of the challenges they may encounter with clients with an autism diagnosis if

they have some basic understanding of the disorder. A long-term goal for the field of social work

would be to “increase the capacity of the social work profession to best support people on the

autism spectrum through practice, research, and advocacy” (Bishop-Fitzgerald et al., 2018, p.12).

Hiring autistic professors in higher education can incorporate lived experiences into

disseminating information on autism. Having knowledgeable faculty in this area would be a first

step to imparting knowledge to students. Researchers also suggest incorporating more course

availability on autism at both the BSW and MSW levels, as well as opportunity to interact with

autistic clients. This could include field placement opportunities in community settings

(including special education schools) that would give students the experience to work with

clients on the spectrum. At the PhD level, the researchers recommend that a mentoring network

be available to social workers whose research interest is in the area of autism.

A 2016 study focusing on training in autism found that half of the 53 participants had

received training in autism through their education, either classes or internship. The participant

population was comprised of marriage and family therapists as well as social workers; it was

found that marriage and family therapists were “more likely to report training in ASD…through

their professional education” at a rate of 60%, compared to social workers reporting 26%. The

study also found that only about 15% of the participants’ supervisors had training in the area, and

22% reported that their employer hosted training on autism. This can lead the reader to believe

that more training opportunities in the workplace could benefit clinicians who serve autistic

clients (Williams & Haranin, 2016).

Autism Competency for School SW

24

To identify the gap in coursework for social workers regarding disabilities (especially

autism), Mogro-Wilson et al. introduced an elective class for Master’s level social workers

which focused on “micro and macro competencies and inclusion of an empowering, strengths-

based, family focused, interdisciplinary and lifespan approach” (2014, p. 65). The course

featured interdisciplinary guest speakers (such as occupational, physical, and speech-language

therapists), and was offered twice during the course of the study (15 participants in the first

group, 20 in the second). Course evaluations were taken (student rating average 9.5 out of 10),

and the course was added permanently. In this article, the researchers point out that among 93

schools of social work, “27% included disability content in their curricula” (2014, p. 64).

Considerations for those course offerings should include how much content is devoted to the area

of autism. According to the Council on Social Work Education (CSWE) data on MSW programs,

3.6% of accredited programs offer a certificate program to prepare serving clients with a

disability, 1.8% of students gain experience with the population through field education, and

1.1% of accredited MSW programs offer the opportunity to specialize in serving disability

populations (Fuld, 2020).

Practical Autism Training. Higher education is not the only setting in which social workers

learn about autism. Social workers may be employed in settings that provide opportunities for

training to effectively serve autistic clients. A 2019 study in Norway evaluated participants’

knowledge of autism gained after participating in a training program. The study also recognized

that the staff would benefit from ongoing, practice-based training to remain competent in the

field. One way that school social workers can receive the ongoing training in the field of autism

is through continuing education opportunities; since most states require that social workers

Autism Competency for School SW

25

renew their license every two years, it would be beneficial to seek out social work-specific

trainings in the area of autism to maintain competency (Ozerk et al. 2019).

In continuing to analyze how professionals learn about strategies to work with clients

with autism, a study by Silva et al. in Brazil evaluated how providers at a psychiatric facility

were trained in the area of autism (2018). The study consisted of 14 interdisciplinary

participants, including an educational psychology specialist. During the training sessions, staff

participated in lectures and watched videos containing examples of symptoms. Participants

completed questionnaires as well as responded to open-ended questions about using strategies for

particular symptoms presented. Results revealed that staff “exhibited increased knowledge in all

13 subjects” that were evaluated through pre-tests and post-tests (Silva et al., 2018). The study

did point out that at times, staff did have to leave the training early to attend to issues that were

occurring on the unit, and therefore were not able to participate in complete trainings at times.

Methods of training for social workers in the area of autism would be a consideration due to the

type of setting, to potentially avoid any issues such as participants’ leaving for work-related

obligations. This should be a consideration for professional development in a school building

while students are still present. It could be considered to use professional development days as an

opportunity for social workers to receive training opportunities in the area of autism.

Use of Supervision. Social workers who are supervisors in the school setting may be in a

position to provide learning opportunities to their supervisees in supporting autistic students. The

goal of social work supervision is to support and grow skills needed to support students. For

example, case presentations can help school social workers discuss challenging situations and

gain knowledge from colleagues (Necasova, 2018). Individual and group supervision can allow

social workers to gain necessary skills that are specific to the school specialty. Supervision of

Autism Competency for School SW

26

other social workers in a school setting encompasses part of the social worker role, although

qualifications and training of supervisors may differ among jurisdictions (Richard & Villareal

Sosa, 2014). Incorporating information on autism for school social workers can lead to more

competent and effective leaders when social workers are promoted into a supervisory role. The

supervision process can help social workers gain knowledge and strategies to serve specific

populations within the school setting.

Clinical Strategies

One role a school social worker may be tasked with is to model and encourage the use of

socially appropriate interaction skills among students, most often between autistic students and

those who are neurotypical. In a study by Yazici and McKenzie, the researchers evaluated the

“socio-communicative skills” among special education students in Turkey who had a diagnosis

of autism (2020). Some of the strategies recommended included peer education (between a

student with ASD and a neurotypical student), educational games, reviewing school rules,

visuals, and family involvement. There are cross-cultural considerations when reviewing this

study, for example (as the study points out) the use of eye contact in American culture compared

to other cultures. Eye contact can be an uncomfortable behavior for autistic individuals, yet some

therapists encourage it through their work with clients. Reviewing strategies in the US as well as

other countries can strengthen the reliability of the strategies, that are found to be effective across

many different cultures.

As counseling can be a significant part of a social worker’s role in the school, a student

with autism may present with different learning needs rather than traditional “talk therapy.”

Some of the strategies for group work, which could be used in the individual setting as well, as

appropriate, include incorporating the use of visual strategies including videos, role plays, and art

Autism Competency for School SW

27

activities (Cisneros & Astray, 2020). It is important for school social workers to be mindful of

the ways in which a person with ASD learns and communicates, most importantly, incorporating

the use of visuals in therapy sessions.

Existing Tools and Certifications

Measuring Autism Knowledge. There are several measurement tools in existence to measure a

person’s knowledge on autism. The Questionnaire on Autism developed by researchers

Mavropoulou and Padeliadu in 2000 and used in an English study to evaluate social workers

previous knowledge of autism (Preece & Jordan, 2006). The areas the questionnaire measured

included etiology, diagnostic characteristics, and treatment of autism. The researchers recognized

that while there is work in educating professionals on autism, training material (such as

questionnaires) are not always relevant to targeting a social work audience; some items were

changed on the tool to be more appropriate to administer to a social work participant population.

The ASD Knowledge Questionnaire (ASD-KQ) includes 24 self-reported questions.

Participants’ responses are based on a 5-point Likert scale (including “Don’t Know” as an

option); the higher the participants’ score is on the questionnaire indicates more knowledge on

the area of autism (Giannopoulou et al., 2019). This questionnaire was initially developed to

administer to Greek teachers to measure their level of knowledge on autism, accompanied by a

training seminar on autism. While this study did not include social workers, the model of training

and survey could be applied to school social workers to evaluate effectiveness of workshops.

A Norwegian study conducted a project on improving competency in autism among

primary and secondary educational staff. Staff included teachers, counselors, and child/family

workers. The intervention consisted of in-person meetings over the course of two school years.

Autism Competency for School SW

28

The meeting goals consisted of various topics related to the topic of autism, case studies, and

examining policies that can affect the population. There was also a pre-test and post-test

completed by participants. Results showed that there were varying degrees of knowledge gained

throughout the study; the most significant improvement in competency was among special

education teachers (Ozerk et al., 2018).

State Qualifications. States may have varying requirements for social workers to work in a

school setting. For example, any social worker who is employed at a Maryland (where the

researcher is employed) public school or a nonpublic special education facility can apply for a

School Social Worker certification through the Maryland State Department of Education

(MSDE). The applicant also must show an active, valid license issued by the Maryland Board of

Social Work Examiners (BSWE). The certificate is approved for five years as a Professional

Certification. A social worker must take an Introduction to Special Education university-level

course within those five years before renewal of the certification. If the social worker took the

course while attending university, the social worker does not have to take the course again. If the

course is taken within the first five years, the social worker can apply for an Advanced

Professional Certificate - School Social Worker. This is the highest-level certification for school

social workers in the state of Maryland (MSDE, n.d.). While the course on special education may

include information on autism, it may be minimal as there are other topics covered, including

policies and resources as well as responsibilities related to school social workers (such as

Individualized Education Plan, or IEP, documentation). Because a school social worker has up to

five years to complete the course, they may not take it within their first few years of serving

students. If they encounter a student on the spectrum, they may not have enough knowledge or

resources to be prepared to serve the student.

Autism Competency for School SW

29

Pennsylvania has a similar requirement that a social worker employed in a school setting

must hold an MSW from a CSWE accredited program. The social worker must also be certified

as a licensed social worker (LSW) or licensed clinical social worker (LCSW) through the

Pennsylvania Department of State, Bureau of Occupational Affairs. Beginning in 2023, school

social workers will have to show proof of a valid School Social Worker Specialist Certification

or be in the process of earning the certificate by being enrolled in an approved program

(Department of Education, 2021). Higher education institutions may offer the certification

program to social workers employed in a school. For example, the program offered at Kutztown

University of Pennsylvania consists of 16 credits; students who are currently enrolled in an

MSW program may enroll in the certificate program concurrently (Kutztown University of

Pennsylvania, 2021). Certification programs include information related to special education;

specific information related to autism may vary among programs and specific offerings related to

working with students who have a disability.

Certifications. School social workers may seek out training on their own that focuses on autism.

This may occur through continuing education workshops, conferences, as well as seeking out

materials such as books and websites that can help them to become a more informed practitioner.

Certification programs that may be of interest to school social workers include the Autism

Spectrum Disorder Clinical Specialist (ASDCS) and the Certified Autism Specialist (CAS).

Training to earn the ASDCS certification is tailored for professionals who have advanced clinical

licensure in their respective field, including social work. A minimum of 18 credits in autism-

related trainings must be completed to earn initial certification, and 12 credits must be completed

every two years to maintain active certification (Evergreen Certifications, n.d.). For social

workers who are not working in a clinical setting, there is the option to earn a Certified Autism

Autism Competency for School SW

30

Specialist certificate. A social worker must hold a master’s degree and have at least two years of

experience serving autistic clients. The 14-credit training course consists of topics on

comorbidities, behavior modification, program development, early childhood identification, and

parent communication. The certification is valid for two years and can be renewed by taking an

additional 14 credits of autism related training (IBCCES, n.d.).

There are also autism certificate programs which are offered through higher education

institutions. Typically, the programs offer coursework related to educating autistic students.

While classroom-based staff may find the information relevant to their roles in the school setting,

a school social worker may find the information relevant to their role as well. School social

workers may be placed in special education programs where they serve a higher number of

autistic students compared to a general education setting and may seek out autism-specific

coursework.

ABA Therapy. When maladaptive behaviors prevent a student from being successful in the

school setting, one of the roles that a school social worker may undertake is creating and

implementing behavioral interventions, A functional behavior assessment (FBA) and behavior

implementation plan (BIP) may be facilitated by the school social worker, with input from the

classroom team, parent, and student. This task may lead a school social worker to pursue further

training in analyzing behavior, as well as certification as a Board-Certified Behavior Analyst

(BCBA). Applied Behavior Analysis, or ABA, guides the work by BCBA’s. It has been a form

of behavior modification that autistic children are often referred to as a way to “treat”

maladaptive behaviors. Self-advocacy groups, such as the Autistic Self-Advocacy Network

(ASAN), have provided statements on trauma autistic individuals have experienced as children

during ABA therapy (ASAN, 2017). There is also literature to reflect autistic experiences with

Autism Competency for School SW

31

ABA therapy in research, including individuals becoming dependent on prompts and

reinforcements rather than becoming more independent (Sandoval-Norton, et al., 2021). School

social workers would benefit from being aware of how the larger autistic community views

certain interventions that may be viewed as harmful. Gaining knowledge of evidence-based

strategies, whether they are viewed positively or negatively, can help the social worker make an

informed and ethical decision about applying interventions in the school setting.

Theoretical Framework

Several theories help to inform the topic of autism competency in the field of school

social work. Ecological systems theory (Brofenbrenner, 1994) explains how systems interact

with each other, as well as how the systems can influence each other. It is the overarching theory

that informs how students interact with their school environment as well as their family.

Understanding this theory assists social workers in understanding student needs, challenges, and

supports in different environments. Social learning theory and transformative learning theory

explains how professional social workers are motivated to learn new skills and information, as

well as supporting adult learning needs. These two theories are necessary in understanding the

learning needs and styles of professional social workers before introducing competencies for

supporting autistic students.

Humanistic theory and critical disability theory inform competent social work strategies

and interventions in a manner that respects the neurodiversity of the students served. Operating

from a strengths-based perspective, the school social worker can adopt affirming practices in

working with autistic students. Using the framework described in this paper to guide school

social work, the social worker can ensure that practices and strategies used with students are

Autism Competency for School SW

32

delivered in an ethical and respectful manner. These theories help to inform competencies for

school social work, later discussed in the Recommendations section.

Figure 1

Theoretical Framework for Autism Competency in the School Social Work Setting

Ecological Systems Theory. Ecological systems theory is relevant to school social work as the

theory can inform roles in different settings. Ecological systems categories include school

support practices, home support practices, and community support practices (Thompson et al.,

2019). Case management and clinical skills are necessary to carry out job duties in these

Ecological

Systems

Theory

Humanistic

Theory

Transformative

Learning Theory

Social Learning

Theory

Critical Disability

Theory

Autism Competency for School SW

33

categories. A school social worker may provide individual interventions to a student, involve

families in school-wide events, as well as create partnerships with community agencies that may

benefit students and/or families. Ecological systems theory can also be considered as a

framework for supporting special needs and social interactions in the school setting. The theory

provides explanation for how the individual’s needs may be impacted by inclusion (or exclusion)

of social activities with peers in the school setting. Understanding how the autistic student

interacts with others in various systems will help to guide appropriate interventions.

Ecological systems theory also explains how larger systems can impact students. The

school environment influences students based on social interactions, academic challenges,

support from staff and opportunities for extracurricular activities. The family environment

impacts the student in a way that may impact the student (positively or negatively) during the

school day (Fearnley, 2020). Awareness of ecological systems theory and the impact on students

helps to inform social work practice in terms of case management services for the family and

school-based supports for the student. Although existing literature on school social work services

primarily focuses on case management rather than micro-level interventions (Rafter, 2022), case

management services can be a valuable intervention impacting student success in the school

setting.

Humanistic Theory. Humanistic theory can be applied to school social workers to understand

the individual needs when working with an autistic student experiencing challenges in the school

setting. It also places value on creating strong relationships between social worker and client.

Working from a relationship-based practice, social workers can respond to individual needs of

students (Frost & Dolan, 2021). By placing more attention on the relationship, social workers

may be able to move away from using a medical model to analyze a student’s situation, and

Autism Competency for School SW

34

place attention to the individual student. Humanistic theory reminds practitioners that individual

experiences are important to consider in work with clients. According to the Diagnostic and

Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, there are three levels of severity of autism which present

a wide range of symptoms (APA, 2013). Autistic students may have different challenges, some

requiring more intensive behavioral support while others require minimal social support. In

addition to case management, a school social worker may deliver IEP counseling services to

autistic students in the school setting. A school social worker who is working closely with a

family may also be in a situation to provide family counseling with the student and their

caregivers. By integrating cognitive behavioral theory with a humanistic approach to counseling,

school social workers can help both staff and families to use the most appropriate strategies to

assist the child being successful in the school setting (Hannon, 2014).

Individual symptoms must be considered to create school-based behavioral interventions

that are motivating and successful for the student. Working from a humanistic perspective also

helps to work from a strengths-based perspective which can help autistic students cope with

stressors in the school setting, as their neurotypical peers may be faced with similar stressors as

well (Hannon, 2014).

In terms of strategies that social workers can use to serve autistic students, it is suggested

to shift away from the medical model. Rather than a socially perceived “hierarchy”, all groups

are equal, and symptoms of autism are just another unique characteristic. When shifting thought

about clients and their diagnosis, a social worker may be able to look at the client needs from a

different perspective (Haney, 2018).

Social Learning Theory. Social learning theory can be applied to the identified problem to

address the need for school social workers to learn about the topic of autism. Social learning

Autism Competency for School SW

35

theory reminds practitioners that “behavior can be altered,” including behaviors that

professionals demonstrate in the field (Weisner & Silver, 1981). If a school social worker is

employed by a school and does not have a model of evidenced-based strategies to use in their

work with autistic students, they may not know how to address challenges presented in the

school setting. But if a school social worker has a network of professionals to model strategies,

they can learn methods to apply to their work with students to increase their success in the school

setting.

School social workers who are employed in special education settings may have more of

a chance to model evidenced-based strategies compared to professionals in other settings. A

special education school may have a higher population of autistic students, especially students

who may have more intensive academic, behavioral, and/or social needs that a typical general

education school cannot meet. School social workers in these settings may be able to learn best

practices from each other (especially social workers who are new to the setting) and collaborate

on student cases. Because social learning theory looks at aspects not only of the behavior itself,

but environmental factors as well, the theory helps to explain if a school social worker is

knowledgeable on the topic of autism when considering the type of school setting they are

employed in.

Transformative Learning Theory. Transformative learning theory applies to ways that adults

can learn. Research may focus on the theory as it applies to a classroom setting, but

transformative learning can occur in the field setting as well. The theory examines ways that

learners can change their previous perspectives on a topic, based on new information being

presented. Reflective practices, including critical thinking, are strategies that are encouraged

while examining various points of view on a topic. Transforming previously held beliefs may be

Autism Competency for School SW

36

difficult for some, but it is not impossible. The ability to critique perspectives and consider new

information to change a perspective can be a fair evaluation of a learner’s ability to think

critically, both in the classroom and in the field. Being receptive to new information, whether in

a conversation or reading a publication, can be a sign that the person is willing to learn and has

the flexibility to adapt to more effective strategies to better serve their clients (Nohl, 2015).

Social work educators may witness the transformative learning process in the formal

classroom setting, especially when reflective practices are encouraged among their students.

Role play situations can be a great exercise for students to start the transformative process. After

a role play is finished, allowing the students involved in the role play to share their experience of

how it felt to be the “client” or the “therapist” can help students understand situations they may

encounter in the field. Allowing other classmates to comment on the role play can lend different

perspectives to the role play situation based on information provided by their peers. Considering

the perspectives of what their peers observed can help the student shift their thinking about what

they could do next time a similar situation occurs with a client. In one study with social work

students, when students were given the opportunity to engage in a transformative learning

process, half of the participants shared that their views had changed after learning more about the

topic (Lorenzetti et al., 2019). When a social work educator allows this type of reflection to

occur in the classroom, the process can lend itself to transforming the ideas of the student that

can someday be beneficial to the clients that will be served.

Critical Disability Theory. A theoretical perspective that has borrowed frameworks from other

theories focusing on marginalized populations (gender, race, sexuality) is the critical disability

theory (CDT). The theory has grown from the disability rights movement, evaluating the stigma

and oppression an individual experiences as a result of their disability (Fuld, 2020). CDT affirms

Autism Competency for School SW

37

the experiences of those with physical and cognitive disabilities, but with “invisible” disabilities

as well. Practicing from a CDT-affirming perspective involves the following:

-Ableism is invisible.

-Epistemic violence is experienced by the disabled.

-Ableism creates a binary view…when it is more accurate to consider a continuum.

-Disability is a socially constructed phenomenon.

-The disabled have a right to autonomy and self-determination.

-The medical industry commodifies the disabled (Procknow et al., 2017).

CDT can help social workers to evaluate “problematic cultures of service delivery” in

schools as well as among community providers, as well as to acknowledge stigma and social

oppression that the population experiences (Fuld, 2020, p. 512). Providing social work

intervention through a CDT lens can help to ensure that strategies are chosen and delivered in an

ethical, harm-reducing manner.

Gaps in Literature

There appears to be a need of educational opportunities both for practicing social workers

as well as social work students. During the literature review process, several articles were located

that acknowledged the need for incorporating a disability curriculum (not specific to autism) into

social work programs, both at the undergraduate and graduate levels. In the Mogro-Wilson et al.

study, the researchers point out that among 93 schools of social work, “27% included disability

content in their curricula” (2014, p. 64). That percentage does not specify how much of the

information contained autism-specific information. Literature on critical disability theory also

highlights the need for social workers to be educated on disability (Thomas-Skaf & Janney,

2021). Autism information would be beneficial to include in both BSW and MSW curricula

Autism Competency for School SW

38

(Bishop-Fitzgerald et al., 2018). For doctoral students, it is recommended that mentors be

available to social workers whose research interest is in the area of ASD. It appears that course

offerings related to autism and developmental disabilities is not widespread, but it is unknown

how many students demand the access to the information.

While studies focus on school-based staff and knowledge of autism, social workers are

not often included. The Ozerk et al. (2018) study measuring did not include social workers,

rather focusing on other professionals working in the school setting. Due to the nature of the

school social work role, research may reveal information and needs that are different compared

to other school-based professionals that work with autistic students.

Conclusion and Implications

The goals and outcomes of this study have implications on the area of Social Work

Education – both at the university level and regarding continuing education opportunities for

licensed social workers in the field. The researcher would like to evaluate the level of previous

education social workers have received in the area of working with clients on the autism

spectrum. Through the researcher’s professional experiences in supervising school-based social

workers in an outpatient mental health setting, there was a lack of knowledge in serving students

with an autism diagnosis. There appears to be a need of educational opportunities both for

practicing social workers as well as social work students. While only about ¼ of universities

offer disability content in their social work courses, it is unknown how much of that information

includes autism content. Licensed social workers may be unprepared to serve their clients if they

have never been given even brief, introductory information on ASD. Social work education can

improve in preparing competent social workers for field work by exposing them to the

information needed to serve clients. Gaining a competent understanding of ASD will help social

Autism Competency for School SW

39

workers be more effective in serving the needs of their students and families. Understanding how