SECONDARY SCHOOL SENIOR CAPSTONE PROJECTS:

A DESCRIPTIVE AND INTERPRETIVE CASE STUDY

ON POST-SECONDARY STUDENTS’

PERSPECTIVES OF LEARNING TRANSFER

A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY

OF HAWAI'I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULLFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR

THE DEGREE OF

DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY

IN

EDUCATION

MAY 2017

By

Vanessa Applbaum Yasuda

Dissertation Committee:

Tara O’Neill, Chairperson

Paul D. Deering

Charlotte Frambaugh-Kritzer

Frank Walton

Michael Salzman

Keywords: project based learning, learning transfer, high school capstone projects,

college and career readiness, experiential learning, higher education

brought to you by COREView metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk

provided by ScholarSpace at University of Hawai'i at Manoa

ii

©

Copyright

2017

By

Vanessa Applbaum Yasuda

iii

Dedication

For my son August,

I truly appreciate your sacrifice for my selfish pursuit.

Your resilience and optimism always amazes me, may those dispositions remain

with you for all of your years.

iv

Abstract

This descriptive and interpretive case study investigates how 12 undergraduate college

students perceived participation in their high school Senior Capstone Project (SCP) impacted

their college academic experience. Learning transfer was explored from the learner’s

perspective. Data was collected using qualitative methods in three sequential phases in the spring

and summer of 2016. Triangulated data sources include: online questionnaires, focus groups,

artifacts, artifact-based interviews, participant reflective journals, and final interviews.

For this study, SCP is defined as a culminating project based learning (PjBL) experience

students elect to take part in their senior year of high school. Participation in the SCP

encompasses experiential techniques of self-direction, authentic problem solving, mentor

collaboration, and reflection to complete a research paper, fieldwork, a portfolio, and a

presentation. Data analysis produced four key themes: (1) acquisition of skills, abilities, and

dispositions took place following two dynamic relationships: concurrently with interdisciplinary

content and simultaneously while learning and using, (2) participants described how their SCP

acquired content knowledge, skills, abilities, and dispositions were later applied in the far

transfer setting of college, (3) examination of three embedded case studies surfaced career and

college preparation connections, and (4) participants perceived self-efficacy resulting from their

SCP experience provided confidence for their college work. Throughout all four themes learning

transfer was found to cross boundaries and contexts, from the acquisition setting of the high

school SCP to the far transfer setting of the college academic experience.

Participation in the high school SCP was found to positively impact students later in

college. This study added to the available literature on the SCP, PjBL and learning transfer. The

evidence of the positive impact of PjBL activities provided by the voices of the participants of

v

this research should be considered when decisions are made regarding allocating limited

classroom time.

vi

Table of Contents

Chapter 1 - Introduction 1-14

Overview ………………………………………………………………………... 1-6

Senior Capstone Project background ……………………………………….. 2-5

Senior Capstone Project in Hawai‘i…………………………………………. 5-6

History of Senior Capstone Projects in Hawai‘i ………………………... 5-6

Hawai‘i’s Senior Capstone Project requirements ………………………. 6

Purpose of the Study ……………………………………………………………. 7

Research Question ………………………………………………………………. 7-8

Significance of the Study ……………………………………………………….. 8-11

Definition of Terms ……………………………………………………………... 11-13

Chapter Summary ……………………………………………………………….. 13

Notes ……………………………………………………………...…………….. 14

Chapter 2 - Conceptual Framework 15-52

Senior Capstone Project …………………………………………………………. 15-26

Intended purpose and outcomes of the Senior Capstone Project …………… 16-19

Hawai’i purpose and learning outcome for the Senior Capstone Project 19-20

Existing Senior Capstone Project studies …………………………………... 20-23

Project based learning ………………………………………………………. 23-26

What is project based learning? ………………………………………… 24-26

Instructional methods for project based learning …………………….…. 26

Learning Transfer ……………………………………………………………….. 26-43

Traditional learning transfer perspective …………………………………… 27-28

Alternative learning transfer perspectives ………………………………….. 28-35

Actor-oriented perspective ……………………………………………… 30-31

Preparation for Future Learning ………………………………………... 32

Application of alternative learning transfer perspectives …………….… 33-35

Learning transfer and project based learning or problem based learning …... 35-37

Indicators of college readiness ……………………………………………... 37-43

Self-efficacy …………………………………………………………………….. 43-50

Self-efficacy theory …………………………………………………………. 43-47

Self-efficacy and project based learning or the Senior Capstone Project ….. 47-49

Chapter Summary ……………………………………………………………….. 50

Chapter 3 - Methods 51-101

Context of Study ………………………………………………………………… 51-52

Research question …………………………………………………………… 51

Research approach ………………………………………………………….. 51-52

Description of the Case …………………………………………………………. 52-60

Description of participants ………………………………………………….. 53-56

Description of place ………………………………………………………… 56-58

Description of time …………………………………………………………. 58

Description of researcher …………………………………………………… 58-60

Pilot Test ………………………………………………………………………... 60-62

vii

Pilot test data collection …………………………………………………….. 60-61

Pilot test data analysis ………………………………………………………. 61-62

Data Collection …………………………………………………………………. 64-80

Interview guides and interview questions ………………………………….. 64-67

Interview phases ……………………………………………………………. 67-76

Phase 1, online questionnaires and focus group interviews ……………. 68-71

Phase 2, college work artifacts and artifact-based interviews ……….…. 71-74

Phase 3, reflective journals and final interviews ……………………….. 74-76

Research journal ……………………………………………………………. 76-79

Audit trail ……………………………………………………………….. 76-77

Reflective journal ……………………………………………………….. 77-79

Recording and transcribing …………………………………………………. 79

Member checks …………………………………………………………...… 79-80

Peer reviews ……………………………………………………………...…. 80

Data Analysis ……………………………………………………………..……. 81-93

Process of thematic coding ……………………………………………...….. 83-84

Phase 1, online questionnaires and focus group interviews ………………… 84-89

Phase 2, college work artifacts and artifact-based interviews ……………… 89-90

Phase 3, reflective journals and final interviews ……………………………. 90

Comprehensive analysis and interpretation …………………………………. 90-93

Human Subjects …………………………………………………………………. 93-94

Credibility and Dependability …………………………………………………… 94-100

Credibility …………………………………………………………………… 95-97

Transferability ……………………………………………………………….. 98-99

Dependability ………………………………………………………………... 100

Confirmability ……………………………………………………………….. 100

Chapter Summary ……………………………………………………………….. 100-101

Chapter 4 – Findings 102-179

Chapter Introduction …………………………………………………………….. 102-103

Theme 1: Participation in the Senior Capstone Project Experience Led to 103-120

the Acquisition of Skills, Abilities, and Dispositions

Takeaways from the Senior Capstone Project experience 103-106

Interpretation of findings: Two dynamic relationships 106-119

Skills …………………………………………………………….…….. 109-115

Abilities ………………………………………………………….…….. 115-118

Dispositions …………………………………………………….……… 118-119

Summary: Theme 1 …………………………………………………….….. 119-120

Theme 2: Transference of the Senior Capstone Experience to the College 120-138

Academic Experience

Transference of abilities and dispositions ………………………………….. 121-128

Transference of production skills needed to complete research papers, …… 128-137

fieldwork, portfolios, and presentations

Summary: Theme 2 …………………………………………………..…….. 137-138

viii

Theme 3: The Senior Capstone Project Experience Directly Prepared the Case 138-163

Studies through Experiential Learning that Transferred to their

College Academic Experience

Parker’s Senior Capstone Project led him to discover his love for ………… 140-146

engineering

Emily’s Senior Capstone Project allowed her to discover that she really 146-152

could teach

Dereck’s Senior Capstone Project fieldwork provided lasting experience 152-157

for his dream career, journalism

Connections across the Case Studies ………………………………………. 158-163

The career connection …………………………………………………… 158-160

The college preparation connection ……………………………………... 160-163

Summary: Theme 3 ………………………………………………………….. 163

Theme 4: The Emergence of Self-efficacy ……………………………………… 163-177

Increased comfort level to complete work similar to Senior Capstone …….. 165-171

Project in college

Increased comfort level toward applying skills, abilities, and dispositions 171-176

General beliefs in self attributed to the Senior Capstone Project experience 176-177

described as transferable to life situations

Summary: Theme 4 ………………………………………………………….. 177

Chapter Summary ……………………………………………………………….. 178-179

Chapter 5 – Discussion and Conclusions 180-198

Chapter Introduction …………………………………………………………….. 180-181

Review and Discussion of Findings …………………………………………….. 181-191

Theme 1 ……………………………………………………………………... 181-182

Theme 2 ……………………………………………………………………... 183-184

Theme 3 ……………………………………………………………………... 184-189

Theme 4 ……………………………………………………………………... 189-190

Summary of review and discussion of findings …………………………….. 190-191

Recommendations for Future Study …………………………………………….. 191-195

Overarching Implications ……………………………………………………….. 195-198

References 199-212

Appendices 213-221

Appendix A: Pre-Interview Demographic Questionnaire ………………………. 213

Appendix B: Online Questionnaire ……………………………………………… 214

Appendix C: Focus Group Interview Guide …………………………………….. 215

Appendix D: Information Sheet and Guide for Artifact-based Interview …….... 216

Appendix E: Final Interview Guide …………………………………………….. 217

Appendix F: Information Sheet for Reflective Journal ………………………… 218

Appendix G: Member Check Templet …………………………………………. 219

Appendix H: Consent to Participate in Research Project ………………………. 220-221

ix

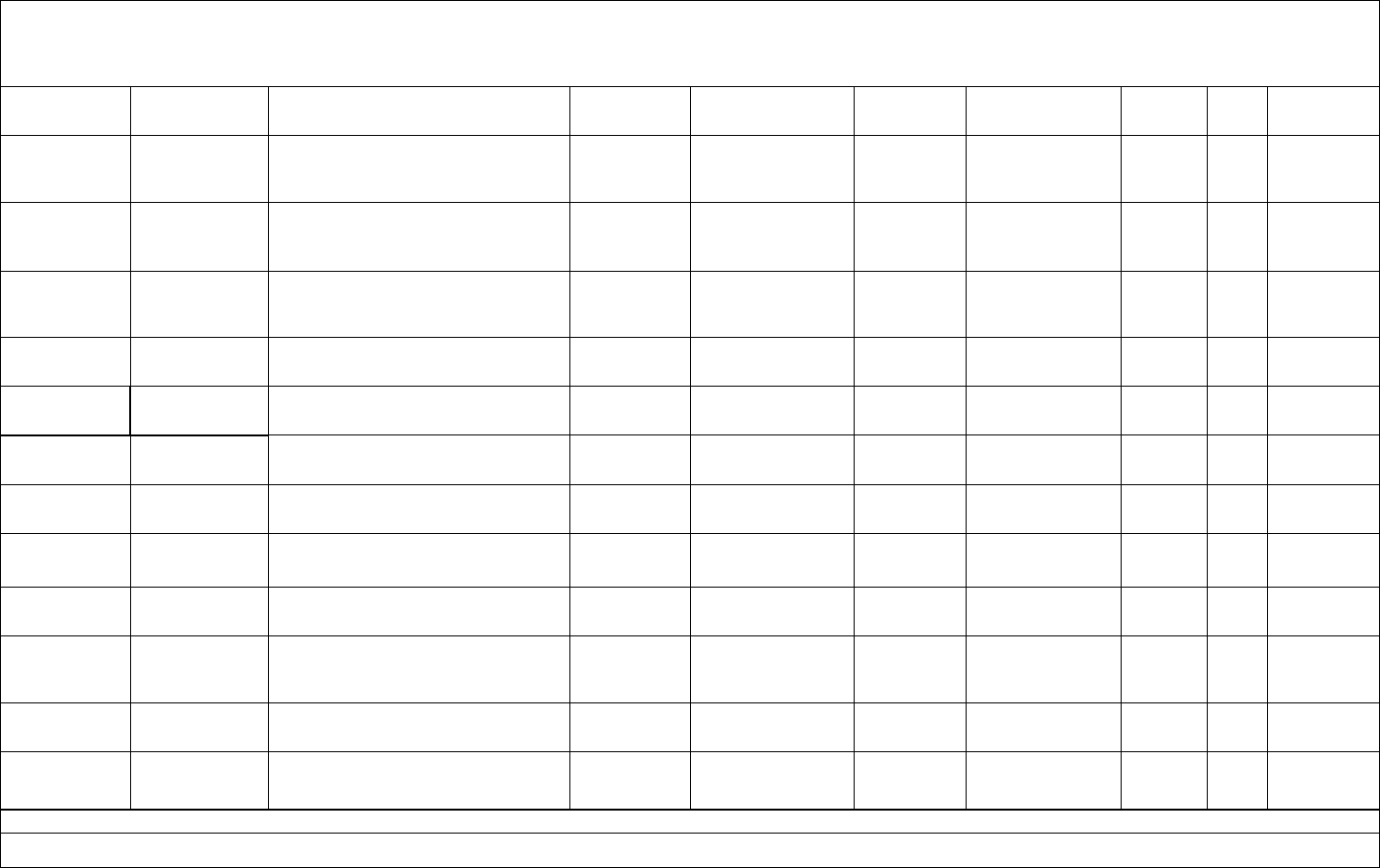

List of Tables

Table 1: Senior Project Center’s: Attitudes, Skills & Knowledge ……………………… 18

Table 2: Participants’ Demographics ……………………………………………………. 55

Table 3: Timeline of Data Collection …………………………………………………… 68

Table 4: Focus Groups …………………………………………………………………... 70

Table 5: Participants’ Self-selected College Work Samples ……………………………. 72

Table 6: Timeline of Data Analysis ……………………………………………………... 82

Table 7: Skills, Abilities, and Dispositions Used during the Senior ……………………. 104

Capstone Project

Table 8: Skills, Abilities, and, Dispositions Learned during the Senior ………………… 105

Capstone Project

Table 9: Learned about Self during Senior Capstone Project …………………………… 106

Table 10: Skills, Abilities, and Dispositions Needed for College Success ……………… 121

x

List of Figures

Figure 1: Data Collection Sequence …………………………………………………….. 64

Figure 2: Participants’ Reflective Journal Format ………………………………………. 75

Figure 3: Dependability Audit …………………………………………………………... 78

Figure 4: Confirmability Audit ………………………………………………………….. 78

Figure 5: Participant Sheet Analysis Matrix ……………………………………….……. 86

Figure 6: Cross-case Analysis Matrix …………………………………………………… 88

Figure 7: Comprehensive Analysis Matrix ……………………………………………… 92

1

Chapter 1

Introduction

Overview

As a high school business teacher in the state of Hawai‘i between 2006 and 2011, I found

project based learning incredibly beneficial to my students. When my accounting students

applied ethical decision making approaches within authentic case study scenarios, they were

highly engaged and motivated throughout the project. Students’ boisterously participated in

round table discussions on topics ranging including embezzlement of company funds, donations

to non-profit charities, and even dilemmas involving being asked to misreport company profits in

exchange for a bonus or promotion; they drew upon their lived experiences and readily applied

learned accounting knowledge to resolve ethical predicaments. Their newfound interests in these

learning activities were so high that they eagerly committed extra time to their research and

collaborative discussions. The teacher-assisted, student-led project approach appeared to permit

students to take risks and build their confidence in purposeful and practical ways. My students

grew well beyond how they performed on a pen and paper assessment and learned more than the

required content (i.e., complex thinking, self-direction, and communication). The senior capstone

project (SCP), an interdisciplinary culminating experience completed during the high school

senior year, was one such learning activity that drew upon previously learned skills (such as

communication and critical thinking) and content knowledge gained during K-12 education

(Egelson, Harman, & Bond, 2002; Summers, 1989).

SCPs were a match for my Career and Technical Education (CTE) classes due to their

real-world, hands-on approach. Some of my most memorable teaching experiences involved

advising a handful of students throughout their SCP experience. As part of the SCP, students

developed their own year-long learning plan and project. The year progressed as my advisory

2

students chose their business related topic, developed their thesis, planned their inquiry,

researched their topic, spent 20 hours with a community mentor, managed their time and

progress, wrote a research paper, and presented their work to a panel of community members. It

was fascinating to witness my students’ struggles and breakthroughs, how they took interest in

the content, and sought to become agents of their own learning. The autonomy of topic selection

and project management gave my students the drive to proceed through the interdisciplinary

requirements. The experience of SCP appeared impactful as if it were building knowledge, skills,

and dispositions that would prove useful for a student’s future. Yet, I wondered about its actual

long-term impacts and to what extent did that learning transfer to collegiate study.

Senior Capstone Project background. SCP is described as an opportunity for high

school seniors to select purposeful lines of inquiry, embark on experiences of their own choice,

develop individual learning plans, and prepare for desired outcomes (Shaunessy, 2004). It is a

culminating experience of a student’s K-12 education and is intended to develop planning,

research, time management, writing, presentation, and interpersonal skills needed for college or

career readiness (Egelson et al., 2002). Due to the autonomy of project type and topic, each SCP

is unique to the student’s design.

Student choices are prevalent for SCPs, beginning with three main project types: (1)

career learning, (2) service learning, and (3) performance based (Harada, Kirio, & Yamamoto,

2008; Wee, 2000). Career learning projects provide students an extended learning experience

where they associate the academic with the vocational to expand their knowledge and skills in

both areas (Ancess, Darling-Hammond, & Einbender, 1993; Darling-Hammond, Ancess, & Ort,

2002). For example, a student may research dental careers and serve as a protégé under the

tutelage of an orthodontist. Service learning projects take the form of community service events

3

or information campaigns and allow students to gain hands-on experience while they apply

previous learned skills to real-world situations (Berman, 2006; Wheeler & McCausland, 2003).

A student conducting a service learning project may research ecology of nearby streams and in

turn, work with environmentalists to develop and implement a protection awareness program in

elementary schools. Performance based projects permit students to develop and demonstrate a

skill, ability, or talent that has an impact on the community (Hawai‘i State Department of

Education, 2010). For example, a student may research the culture and history behind Japanese

taiko drums, train with a temple to learn to play, and perform at a bon dance. All three project

types are inquiry-based, allowing students to determine a problem and develop possible solutions

(Berman, 2006).

While Hawai‘i does not require students to participate in SCPs, some school districts

across the United States require them for graduation. For example, Weymouth Public Schools in

Massachusetts requires an academy pathway-related Capstone Project for graduation, which

must include significant planning, preparation, and implementation (Weymouth Public Schools,

n.d.). Idaho’s Ada School District’s Senior Project is a separate assessment required for

graduation, where students are evaluated on knowledge and application of skills from state

standards yet not assessed on the Idaho Standards and Achievement Test; they must demonstrate

mastery of research, writing, and oral presentation skills (West Ada School District, 2002-2015).

The School District of Philadelphia requires its graduates to complete a Multidisciplinary Project

or a Service Learning Project where students demonstrate communication, problem solving,

school-to-career, citizenship, or multicultural competencies (The School District of Philadelphia,

n.d.). Rhode Island’s statewide diploma system requires two performance assessments for

graduation, exhibitions, and portfolios (Rhode Island Department of Education, 2015).

4

SCPs, at the secondary level, are not just unique to the United States; some are organized

for international implementation. The Advanced Placement (AP) Capstone is designed to foster

academic rigor and college readiness through critical, creative thinking, and research (The

College Board, 2014); CTE projects, presentations, and portfolios emphasize real-world

experiential learning through participation in Career and Technical Student Organizations

(Association for Career and Technical Education, 2011; National Academy Foundation, 2012);

and the International Baccalaureate Programme’s (IB) culminating project applies in-depth

research and interdisciplinary methods to create an extended essay and presentation

(International Baccalaureate Organization, 2005-2014).

High school level culminating project based learning experiences were implemented

similarly but were referred to differently: Graduation Project (Houston & Tharin, 1997);

Graduation by Exhibition (Ancess et al., 1993; Barnett, 2000; Fisk, Dunlop, & Sills-Briegel,

1997; Meier, 1995); Exit Exhibition (Cushman, 1990); Exhibition of Mastery (Sizer, 2004);

WISE Individualized Senior Experience Project (WISE Services, 2014); High School Senior

Capstone Projects (Skeldon, 2012); Senior High School Culminating Project (Erickson, 2007);

Rite of Passage Experience (Cushman, 1990); Mentor/Community-Service Project (Cox & Firpo,

1993); Senior Exit Project (Troutman & Pawlowski, 1997); and Senior Project (a proprietary

term for the Partnership for Dynamic Learning, P4DL, 2008; Summers, 1989). Although studies

referred to the project by different names, the participation experience followed the same general

premise. The varying SCPs were completed in the senior year of high school, followed a project

or problem based learning design with an interdisciplinary focus, required a career or community

collaboration with a mentor, contained a college level writing component, and required a

presentation to a panel of judges.

5

For the purpose of the study’s investigation, I selected the term Senior Capstone Project

(SCP) to refer to the culminating, interdisciplinary, senior year of high school learning

experience. In addition, since this work comprised graduates from the Hawai‘i Public School

System, I based my interpretation and discussion of the SCP upon the HIDOE’s (2010) project

requirements, where students (1) choose their own project, (2) develop their own essential

question and thesis, (3) reflect upon a learning stretch, and (4) demonstrate proficiency in the

four main components: research paper, field work (collaboration with a community member),

portfolio, and presentation.

Senior Capstone Projects in Hawai‘i. History of Senior Capstone Projects in Hawai‘i.

Lahainaluna High School, the first in Hawai‘i to implement a SCP program and create an

extensive senior project guideline packet, later became the model for the current Statewide

guidelines (Goff, Granillo, Seino, & Nakano, 2008). The HIDOE provided SCP guidelines for

statewide implementation during the 2008-2009 school year (HIDOE, 2010). Hawai‘i Board

Policy 4550, titled High School Graduation Requirements and Commencement, was revised in

March 2008 to require completion of a SCP for students to earn a Board of Recognition

Diploma

1

, beginning in the school year 2009-2010 (HIDOE, 2010). It was compulsory that all

students engage in an SCP to fulfill Hawai’i’s participation requirement in the American

Diploma Project

2

. At that time, the HIDOE Strategic Plan (HIDOE, 2008) described the SCP as a

vital learning experience and projected that by 2018 all graduates in the state of Hawai‘i would

have completed one.

In 2012, a newly appointed State of Hawai‘i Board of Education (HIBOE, 2012)

discontinued the Board of Recognition Diploma after the 2014-2015 school year, and in its place

they created honors certificates beginning with the Class of 2016. Due to this policy shift, the

6

SCP was no longer part of a graduation requirement; the HIBOE left its continuation to be

determined by individual high schools. Starting in the 2015-2016 school year, students could opt

to complete a SCP as one of the six elective credits required to graduate (HIDOE, 1995-2013a).

To receive Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM) Education honors, a STEM

Capstone or STEM Senior Project is required. Projects are also required for CTE honors.

Depending on school policy and project requirements, these honors projects may also be

considered as a SCP.

Hawai’i’s Senior Capstone Project requirements. For the HIDOE SCP, students must

submit a proposed project type (i.e., career) and topic (i.e., the legal responsibilities of a

pharmacist) for approval before developing their own thesis and design (Lahainaluna, 2008).

Students have the ability to choose their project type among three options: (1) Community

Service Project, (2) Self-Development Project, or (3) Career Project (HIDOE, 2010). Proficiency

in four main components of the Senior Project is required: (1) research paper, (2) field work

(project collaboration with a community member), (3) portfolio, and (4) presentation. Research

papers are to be written according to college level expectations and must address the student’s

essential question and thesis. Fifteen to 25 hours of field work, alongside a community mentor,

constitutes the students hands-on experience and learning in the topic. The portfolio component

is a compilation of the SCP requirements and provides evidence of the student’s learning and

project development. The final component, the oral presentation, showcases a student’s

communicative proficiency in the area of study. It is assessed by a three member judicial panel

comprised of volunteer community members selected by the school. The intention of the senior

project is to help prepare students to be college and career ready.

7

Purpose of the Study

In order to examine how the SCP may have transferability and retention from one

learning situation to the next, I investigated college students’ perceptions of what they learned

during their past high school SCP learning experience and what, if any, of those dispositions,

skills, and content knowledge were still currently being used in college. Twelve current

undergraduate students at a university in the Pacific region of the United States participated in

this research study. Participants completed an online survey and participated in a series of focus

group sessions. Varied perspectives were sought by selecting participants who had attended

different Hawai‘i public high schools, selected diverse SCP topics, pursued varying college

majors, and represented multiple genders and ethnicities.

My research aimed to discover participants’ perceptions about the extent that content

knowledge, skills, abilities, and dispositions learned from their SCP’s transferred to their college

academic experience. This study provides insight as to what students felt they gained from a

project based learning experience, including the abilities and production skills deemed necessary

to complete work such as research papers, fieldwork, portfolios, and presentations. The study’s

results add to the extant literature, informing educators and policy makers about the significant

benefits of the SCP experience and the long-term impacts students perceived during their

collegiate experience.

Research Question

The following research question guided my study—How do students in a four year post-

secondary institution perceive participation in their high school Senior Capstone Project has

impacted their current college academic experience?

8

Qualitative research methods were used to conduct a descriptive and interpretive case

study. Each individual participant was studied as a multiple case within the main bounded case.

Snowball sampling (Cohen, Manion & Morrison, 2007) was used to obtain referrals for

participants from teacher friends and peers within the College of Education. Twelve participants

were purposefully selected (Teddlie & Tashakkori, 2009) to provide maximum variation based

upon meeting the following specified criteria: attended various Hawai’i public high schools; had

different SCP topics, attended Island University (IU), pursued diverse college majors, and

represented multiple genders and ethnicities. The participants took part in an initial online

questionnaire, one in-person focus group, and two in-person individual interviews; additionally,

they submitted two college work artifacts, a reflective journal, three member checks of their

interview transcripts, and answered follow-up questions via Electronic-mail, as needed.

Data was analyzed through thematic coding (Patton, 2002), resulting in the creation of a

categorical organization of the narrative interview data. Each participant was treated as a smaller

individual case of the larger case study. First within-case analyses took place before an ensuing

cross-case comparison analysis examined any consistencies or differences between the cases

(Patton, 2002). The comparison of smaller cases helped provide triangulation. A final

comprehensive stage of analysis looked at data from the cross-case analysis and the within-case

analyses. The final interpretations served to address the research question and to contribute to the

available literature on SCPs and project based learning.

Significance of the Study

After an exhaustive review of literature on high school SCPs, it was discovered that those

research-based studies merely consisted of limited and focused investigations with findings that

were not widely transferrable (Brandenburg, 2005; Duff, 2006; Erickson, 2007; Pennacchia,

9

2010; Skeldon, 2012). Some research existed describing the extent the SCP provided students an

opportunity to develop planning, research, time management, interpersonal, presentation, and

writing skills needed for college or career (Egelson et al., 2002; HIDOE, 2010; P4DL, 2008;

Shaunessy, 2004). Dissertation and thesis studies had varied scopes of investigation including:

SCP as a combatant of senioritis (Blanchard, 2012; Duff, 2006); judges’ perceptions of rigor

(Skeldon, 2012); a principal’s perspective of planning and development (Mercurio, 2007);

interaction of students’ epistemological assumptions and their behavior during a SCP course

(Urman, 2008), and SCP design focus on rigor, relevance, and relationships (Brandenburg,

2005). I also found studies that examined SCPs from different approaches: data review

(Brandenburg, 2005); surveys of high school students (Duff, 2006); interviews of high schools

students, parents, and teachers (Erickson, 2007); surveys and interviews of recent high school

graduates (Pennacchia, 2010); and surveys and focus groups of judges (Skeldon, 2012).

Existing studies expressed the need for additional research on SCPs and included

recommendations for future studies to be conducted (Brandenburg, 2005; Duff, 2006; Erickson,

2007; Pennacchia, 2010; Skeldon, 2012). Brandenburg (2005) suggested follow-up studies of

SCP students after high school graduation. Erickson (2007) specified studies of their post-

secondary achievement, while Duff (2006) further detailed that future research should address

questions regarding how the SCP writing requirements enhances students’ preparation for

college writing, and the extent to which it contributes to the development of dispositions and

skills associated with self-directed learners. Pennacchia (2010) suggested researching even

further into self-direction with studies on how the SCP may develop a student’s self-efficacy.

Throughout my search, I could only locate two studies (i.e., Egelson et al., 2002;

Pennacchia, 2010) that investigated whether SCP participation had any lasting impact once

10

students graduated from high school. Because my study expanded upon their research, an

overview of their findings is presented in this chapter. Pennacchia (2010) investigated to see if

the SCP’s intention of college and career preparation was met. Following a two-phase mixed

methods explanatory design, 147 graduates of a Rhode Island high school who completed a SCP

completed a questionnaire. After quantitative analysis, six were purposefully selected to be

interviewed. Pennacchia found that 89% of the graduates who participated in the study:

…viewed the senior project components in written communication, oral communication,

research skills, and time management/study skills as valid indicators for college and work

readiness. They believed they exhibited these skills during senior project and that they are

confident that they use these skills in a college or work environment. (p. 106)

She also found that 82% of the respondents had a positive SCP learning experience. SCP was

also deemed to have cultivated perceptions of self-efficacy to the Pennacchia’s surprise.

A paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research

Association (AERA) by Egelson et al.’s (2002) included findings of their longitudinal mixed

methods research study of 12

th

grade high school students (N = 422), graduates (n = 163

surveyed with approximately half serving as a control group and the others participated in SCP),

parents (~ 260), and teachers (n = 436) from four senior project schools and four control non-

project schools in rural or small towns of North Carolina. The study also included qualitative

interviews, focus groups, and document analysis of writing assessments. Responses of surveyed

graduates were compared between the senior project and control (non-senior project) schools.

About 75% of their participants who had graduated and completed a senior project responded

that they agreed or strongly agreed that they developed or improved the following skills during

their SCP experience: public speaking, interviewing, interpersonal, writing, research, planning,

11

organization, and other work-related skills. Graduates of who partook in senior projects reflected

that they had learned more of the surveyed skills than graduates who had not participated in

SCPs. Both groups of graduates reported they were required to use all of the skills surveyed to

some degree since high school. Upon analysis of the participants’ perceived experiences with

SCPs, the authors concluded:

The effects of the Senior Project experience are not necessarily evident in the short-run.

The real value of Senior Project is not likely to be realized until students are out of high

school and called upon to use their Senior Project – related knowledge and skills in a

real-world setting, such as their workplace or an institution of higher education. (p. 22)

Building from Egelson et al.’s conclusion, my dissertation served to investigate the

perceived lasting effects of SCPs as students continued their education at an institution of higher

education. I examined transference of the SCP experience to the college academic experience, in

part to see its ability to prepare students for future academic and career contexts. For it is the

focus of our nation’s schools (Cowan & Carter, 1994), including the HIDOE (2010), to offer

learning activities that prepare students for their future roles in society such as post-secondary

education or the workplace. Influenced by Egelson et al. and Pennacchia’s findings, my study

sought to discover if study participants had similar perspectives to those in North Carolina and

Rhode Island, if the SCP prepared them for college, and more specifically, if what they had

learned while participating in their SCP transferred to their college academic experience.

Definition of Terms

There are five terms used frequently in this study that warrant further attention and

clarification: learning transfer, project based learning, senior capstone project, senior capstone

project experience, and college academic experience. Learning transfer, project based learning,

12

senior capstone project, and college academic experience are defined very differently in the

literature. Senior capstone project experience is not contained in the literature at all. Therefore,

details as to how these terms are to be understood for the purposes of this study are provided.

Learning Transfer—a theoretical approach to learning (Carraher & Schliemann, 2002)

used to explain how new learning was influenced by prior knowledge, learning, and experience.

Situated (Greeno,1998; Lave, 1988) to capture evidence with broad qualitative methods

(Carraher & Schliemann, 2002; Lobato, 2003) to elicit participants’ perspectives (Lobato, 2003)

of how their prior learning (Bransford & Schwartz, 1999) was adapted and applied to another

setting (Barnett & Cici, 2002) comprised of new context and content (Royer, Mestre, &

Dufresne, 2005; Tuomi-Gröhn & Engeström, 2003).

Project Based Learning (PjBL)—a student led, teacher assisted instructional method

where complex projects are “based on challenging questions or problems, that involve students

in design, problem-solving, decision making, or investigative activities; give students the

opportunity to work relatively autonomously over extended periods of time; and culminate in

realistic products or presentations” (Thomas, 2000, p. 1).

Senior Capstone Project (SCP)—a culminating project of the high school students’ K-

12 academic experience, completed in their senior year, drawing upon multidisciplinary content

as well as skills, abilities, and dispositions. The SCP is intended to provide opportunities for

students to gain a firsthand understanding of a career, provide a service to the community, or to

develop a personal interest while experiencing college level research, writing, and

communication (HIDOE, 2010). Proficiency in four main components of the Senior Project is

required: (1) research paper, (2) field work (project collaboration with a community member),

13

(3) portfolio, and (4) presentation. Where students demonstrate a breadth of knowledge and

attainment of learner outcomes including: self-direction, complex thinking, and communication.

Senior Capstone Project Experience—holistic participation in the SCP including using

and learning skills, abilities, and dispositions as well as the interdisciplinary content knowledge

to complete the required SCP components (research paper, field work, portfolio and

presentation). The SCP experience also encompasses participation in PjBL experiential

techniques of self-direction, authentic problems and activities, mentor or teacher collaboration

and feedback, and reflection.

College Academic Experience—all aspects of participation in collegiate courses and

assignments including but not limited to: fieldwork, laboratory reports, classroom activities,

essays, presentations, artwork, projects, and exams. The college work itself and the creation

process to arrive at the culminating product including using previously acquired and transferred

content knowledge alongside newly acquired skills, abilities, and dispositions.

Chapter Summary

Chapter 1 presented background information on SCPs and the need for additional

research that resulted in the premise for this study. It included my interest in the topic as the

researcher as well as the educational significance and purpose of the study. The literature review

in Chapter 2 presents the conceptual framework of the study, which is guided by two essential

lenses: SCP and learning transfer. Chapter 3 describes the methods by which research was

conducted, including descriptions of using a bounded case, sampling procedures, participant

selection, data collection, and data analysis. In Chapter 4 findings are presented before being

elaborated upon in Chapter 5, where conclusions and implications are discussed.

14

Chapter Notes

1

Board of Recognition Diploma: A high school diploma choice with additional

requirements created by the State of Hawai’i Board of Education (HIBOE, 2011) in an effort to

promote more rigorous learning and meet college entrance requirements. The SCP was one of

the extra requirements needed to earn a Board of Recognition Diploma. The Board of

Recognition Diploma began with the Class of 2007 and ended with the Class of 2015. The Board

of Recognition Diploma with Honors began with the Class of 2010 and ended with the Class of

2015. The HIBOE replaced the Board of Recognition Diploma choices with a single diploma

choice and various honors recognition certificates beginning with the Class of 2016 (HIDOE,

1995-2013a).

2

American Diploma Project: A project created in 2005 by Achieve (2012), a nonprofit

organization with the goal of preparing students for postsecondary education, work and

citizenship, and a network of state governors, education officials, and business executives. As

part of the education movement to improve college and career readiness among high school

graduates, the network of 35 states gained attention when it initiated the movement to develop

common core state standards and graduation requirements for high school students to complete

college and career ready curriculum, including a SCP. The network was committed to improving

student achievement and created provisions to increase graduation requirements.

15

Chapter 2

Conceptual Framework

This study examining college students’ perceptions regarding the impact of previous high

school Senior Capstone Project (SCP) learning on their current college academic experience was

framed by three essential bodies of literature: SCP, learning transfer, and self-efficacy. In this

chapter, I will describe how existing literature framed my study. First, the field of SCP laid a

foundation of what constitutes project work and what students were expected to attain from the

experience. Within the SCP lens, the topic of project based learning (PjBL) helped construct a

description of the teaching and learning method that informs the SCP. Next, the field of learning

transfer framed my study with information pertaining how to examine the manner which

knowledge acquired in one setting was later applied in another. Within the learning transfer lens,

the topic of college readiness was included to help specify types of knowledge that were under

this study’s examination, particularly what students were expected to do in college. Third,

literature on self-efficacy framed my study with foundational knowledge on how one’s belief in

self impacts behavior. Studies of self-efficacy involvement with PjBL were of focus.

Senior Capstone Project

Existing literature about SCPs was used as a conceptual lens to help guide my research

study. The SCP literature was useful in understanding what students were expected to learn

through the SCP experience and how it was intended to be helpful for a student’s future college

academic experience or career. This section begins with an overview of articles describing SCPs

and intended student outcomes from the PjBL method. Next, knowledge, skills, and dispositions

that are expected to be gained during SCP completion are presented. Then, information regarding

16

the expected learning outcomes of Hawai’i’s SCPs is included. The section ends with a review of

SCP studies, and descriptions of how they framed the proposed research.

Intended purpose and outcomes of the Senior Capstone Project. In the articles under

review, the SCP was seen to develop students’ skills, abilities, and dispositions through self-

directed long-term project work. The purpose of SCPs was described as promoting college and

work readiness.

In their article, Cowan and Carter (1994) described how the push for culminating projects

and student proficiencies in focus came out of a report by the Task Force 2000’s The U.S.

Department of Labor’s Secretary’s Commission on Achieving Necessary Skills (SCANS, 1991).

In the early 1990s, the task force examined what work was required of schools by asking

employers about their workforce requirements and then asking schools if those requirements

were incorporated into their school curricula. The goal was to reshape the curriculum by the year

2000. SCANS Task Force 2000 focused on the question:

What do students need to know to be successful?…They need to know how to ask

questions and find answers, how to gather and analyze information, how to apply their

knowledge to projects of their own creation while remaining realistic about limitations of

time, money, resources, and support. They need to be able to use relevant technology.

They need to be able to write and speak, clearly and concisely, about what they have

learned. (Cowan & Carter, 1994, p. 58)

The skills SCANS reported such as communication, technology, self-direction, and writing were

used in high school but also viewed as useful for their future, whether they pursued post-

secondary education or a career immediately following graduation. According to Cowan and

Carter (1994), the SCANS (1991) reports led to educational reform that included more cross-

17

curricular, hands-on learning experiences such as the SCP. Reflecting on my own SCP teaching

experience, I believe that SCPs meet the new curricular needs as described by Cowan and Carter

(1994) because they require students to go out into the community, learn through active

participation, provide the opportunity to use the skills they learned previously in high school, and

“understand that school is not just preparation for life. It is life” (Cowan & Carter, 1994, p. 58).

The HIDOE views the SCP as an addition to overall curriculum that has the intention to

prepare graduates for their future role in society; upon completion of a SCP students are to have

demonstrated skills and knowledge to be effective, competent, and appropriate post-secondary

students or members of the workforce (HIDOE, 2010). Through their work on the four main

project components (research paper, field work, portfolio, and presentation), high school seniors

have the opportunity to use previous learned skills as well as demonstrate proficiency in newly

developed skills needed for college and/or career (HIDOE, 2010; P4DL, 2008). Shaunessy

(2004) further detailed skills built through the SCP experience to “offer students the opportunity

to identify purposeful lines of inquiry and to approach them with the appropriate level of

difficulty for their abilities as students develop learning plans, desired outcomes, and embark on

experiences of their own choice” (p. 40). I considered the learning outcomes when examining

any connections or transference participants may or may not have had to their current college

work.

Acquiring a full inventory of student abilities is the objective of the SCP program

developed by The Senior Project Center under auspice of the non-profit school consulting firm,

The Partnership for Dynamic Learning (P4DL, 2008). They offer project management, research,

and assessment tools aligned to the Common Core State Standards. The Senior Project Center

partnered in the development of Hawai’i’s SCP with the HIDOE (HIDOE, 2010). They

18

described that senior projects assess skills that are not usually demonstrated through required

standards-based assessments. The center’s 20+ years of SCP development and implementation

experience led to the compilation of “attitudes, skills and knowledge” students are to attain from

completion of a SCP (see Table 1).

Table 1

Senior Project Center’s Citizens of the 21

st

Century: Attitudes, Skills and Knowledge

Basic Skills and Knowledge

Self-Direction and Collaboration

Deep Independent Thinking and Sophisticated

Problem Solving

Mental Flexibility

Fluency of Ideas and Proficiency in Processes

Reflective, Creative and Original Thinking

Risk Taker

Communication Skills in Text, Video

and Audio Modes

Technology

High Productivity and Quality Production

Personal Characteristics Reflecting Work Ethic

Source: P4DL, 2008.

Several scholarly articles (Cowan & Carter, 1994; Rickey & Moss, 2004, Shaunessy,

2004; Summers, 1989; Wheeler & McCausland, 2003) supported and added to discourse around

similar knowledge, skills, and dispositions introduced by The Senior Project Center. The articles

described a SCP as a beneficial student learning experience that helped prepare students for their

future. The long-term project was seen as a way to enhance existing curriculum while preparing

senior year high school students with skills, dispositions, and abilities needed for college. SCPs

were seen as a venue for students to apply previously learned knowledge and develop new

knowledge while further developing their critical thinking, research, collaboration,

communication, planning, and time management abilities (Cowan & Carter, 1994; Rickey &

Moss, 2004, Shaunessy, 2004; Summers, 1989; Wheeler & McCausland, 2003).

The PjBL method was seen to increase students’ opportunity to use inquiry and

investigation while applying interdisciplinary knowledge and content to address authentic

19

problems or questions (Blumenfeld, Soloway, Marx, Krajcik, Guzdial, & Palincsar, 1991;

Darling-Hammond et al., 2002; Harada et al., 2008; Pearlman, 2010). These studies influenced

the scope of this study as they also sought to discover what students learned from a PjBL

experience. However, these research investigated were constructed on the premise of what

students were expected to learn from the SCP; in contrast, my study uses a novel approach of

assessing what college students perceive to have actually experienced during their SCP

experiences and documented views of transference of SCP learning to the college academic

setting.

Hawai’i purpose and learning outcome for the Senior Capstone Project. This sub-

section of the SCP conceptual framework helped to provide background on the relationship

between project completion to its overall impact. According to the HIDOE (2010) guidelines the

participants of my study should have gained abilities and college preparation through

participation in the SCP. Hawai’i’s SCP was designed to support one of HIDOE’s main

initiatives—college readiness (HIDOE, 1995-2013c). It was also designed to help fulfill the

HIDOE (2010) vision for their high school graduate: “[graduates] possess the attitudes,

knowledge and skills necessary to contribute positively and compete in a global society”

(HIDOE, 1995-2013c). In its SCP guidelines, the HIDOE (2010) detailed that the SCP is

intended to provide opportunities for students to gain a firsthand understanding of a career,

provide a service to the community, or develop a personal interest while experiencing college

level research, writing, and communication.

Guidelines for the HIDOE (2010) SCP specified that “Successful completion of the

Senior Project provides the student with the opportunity to demonstrate advanced proficiency in

the attainment of the General Learner Outcomes (GLOs), career and life skills demonstrating

20

workplace readiness” (HIDOE, 2010, p. 1). The GLOs were initially developed to meet the

accreditation requirements set by the Western Association of Schools and Colleges (WASC).

The GLOs, a set of overarching learning goals that students should have acquired by the time of

their graduation, include: Self-Directed Learner; Community Contributor; Complex Thinker;

Quality Producer; Effective Communicator; and Effective and Ethical Users of Technology

(HIDOE, 1995-2013b). SCP completers were described as 21

st

century learners who, through the

culminating experience of demonstrating the GLOs, became “college, career and citizenship

ready in reading, writing, speaking, listening and language” (HIDOE, 2010, Attachment D). Both

the vision and outcomes of the HIDOE are intended to develop the student for their future

workplace or post-secondary education and are skills, abilities, or dispositions observable in a

student’s SCP work.

The HIDOE (2010) guidelines also detail that students must reflect upon and present a

“learning stretch,” evidence of breadth of learning, that they “push himself/herself to go above

and beyond what he/she already knows or what he/she thinks he/she can do, and a culmination of

knowledge and skills from many different disciplines and life experiences” (HIDOE, 2010, p. 6).

This breadth of learning requirement is designed to help fulfill the HIDOE’s vision—to help

students prepare to be productive 21

st

century citizens. According to the HIDOE (2010), the SCP

will help high school graduates become equipped for their future societal and industry endeavors

including citizenship, post-secondary education, and their career.

Existing Senior Capstone Project studies. Existing research on the SCP at the

secondary level explored the perceived effectiveness in implementation and perceptions of

intended outcomes (Blanchard, 2012; Brandenburg, 2005; Carolan, 2008; Duff, 2006; Egelson et

al., 2002; Erickson, 2007; Skeldon, 2012). All but two of the existing studies described views on

21

SCP implementation had different types of people under examination and did not specify the

project completers’ experiences following their high school graduation. However, despite their

differences from the proposed study’s focus, they still are of value to inform through rich

description and their findings of what encompasses SCPs.

Overall, the existing studies tended to agree that the SCP is a worthwhile learning

experience that met intentions of college and work readiness through developing and building

upon previously learned knowledge, skills, and dispositions; more specifically the SCP showed

student development in planning, research, time management, interpersonal, presentation, and

writing (Brandenburg, 2005; Duff, 2006; Egelson et al., 2002; Erickson, 2007; Skeldon, 2012).

The studies examined SCPs using eclectic methods including a data review of high school

students (Brandenburg, 2005); surveys of high school students (Duff, 2006); interviews and

examination of personal documents of high school students (Carolan, 2008); surveys and

interviews of high schools students, parents, and teachers (Egelson et al., 2002; Erickson, 2007);

surveys, interviews, and focus groups of students, teachers and administrators (Blanchard, 2012);

surveys and focus groups of judges (Skeldon, 2012); and a principal’s perspective of planning

and development (Mercurio, 2007). However, this group of studies was only able to indirectly

inform my dissertation because they investigated participants who were high school students and

did not look at transference after completion of the SCP. My study investigated college students,

who had completed the SCP while in high school and their perceptions of any lasting effects

experienced during their collegiate studies.

My research expanded upon the findings of two particular studies, Egelson et al. (2002)

and Pennacchia (2010). These articles directly informed my research their premise was to

unearth what happened to SCP completers once they had graduated from high school. A paper

22

presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association (AERA) by

Egelson et al. (2002) included findings of their longitudinal mixed methods research study of

12

th

grade high school graduates as well as their parents and teachers in rural or small towns of

North Carolina. About 75% of their participants who had graduated and completed a senior

project responded that they agreed or strongly agreed that they developed or improved the

following skills during their SCP experience: public speaking, interviewing, interpersonal,

writing, research, planning, organization, and other work-related skills. Egelson et al. (2002) also

found that, “Senior Project coordinators and parents’ degree of agreement was even higher –

over 80 percent” (p. 3). They found that students built several skills throughout their SCP

experience: “public speaking, research, [research] writing, presentation, interviewing, time

management, planning, organization, interpersonal, and work-related skills, the skills embodied

in the Senior Project” (p. 22). Graduates of senior project schools reflected that they had learned

more of the skills surveyed while in high school than control group participants. Most graduates

reported they were required to use all of the skills surveyed to some degree since high school.

Pennacchia (2010) investigated if the SCP’s intended outcomes of college and career

preparation were beneficial to participatory high school students. She found that 89% of the

graduates who participated in the study:

Viewed the senior project components in written communication, oral communication,

research skills, and time management/study skills as valid indicators for college and work

readiness. They believed they exhibited these skills during senior project and that they are

confident that they use these skills in a college or work environment. (Pennacchia, 2010,

p. 106)

23

Eighty-two percent of the respondents claimed the senior project was a positive learning

experience overall.

The work of Egelson et al. (2002) and Pennacchia (2010) helped to frame my study

because they also included examination of current college students who completed a SCP while

in high school. However, Egelson et al. (2002) and Pennacchia (2010) were specifically designed

to evaluate their respective SCP program and contained a priori items suitable for program

evaluation. Rather than describe or interpret, my study further examines the SCP with qualitative

interpretation of participants’ perspectives of how their high school experience later impacted

their college academic experience.

Project based learning. Cowan and Carter’s (1994) description (see pp. 16-17 of this

chapter) of the early 1990s movement toward reshaping curriculum to include interdisciplinary

project experiences where students gain knowledge, skills and dispositions for their future,

described a form of project based learning (PjBL). This type of cross-curricular, real-world,

hands-on project learning experience is referred to as PjBL (Blumenfeld et al., 1991; Harada et

al., 2008; Markham, Larmer, & Ravitz, 2003; Newell, 2002; Thomas, 2000). This sub-section of

the SCP lens contains a brief overview of PjBL, which helped underpin the philosophical and

methodical SCP design. The PjBL overview helped to further define the SCP experience, and

therefore assisted with understanding my participants’ perspectives of how it benefited their

future learning.

What is project based learning? The idea of educating students through a project

experience is not new. In his article, The Project Method (1918), Kilpatrick wrote about the

benefits of projects that had a real purpose. He described how new learning resulted by allowing

students to identify, through their own ability, which skills to call upon and new ideas to generate

24

based on a situation of “purposeful activity.” He explained that learning was strongest when

projects originated intrinsically (child chosen) and not extrinsically (teacher assigned).

Kilpatrick’s (1918) description of self-directed learning through working on purposeful projects

was later described by Dewey (1938) as experiential learning, where students acquired

knowledge from what they did and experienced. He saw learning as a continuous process

grounded in experience.

Kolb (1984) continued to conceptualize experiential learning as a process where

knowledge was curated through a transformation of experience. Learning is seen as a holistic

process of human adaptation to the world, where process and experience create knowledge.

Kolb’s learning cycle involves learners moving through concrete experience, reflective

observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation. Learning is an active

process in which students take responsibility for their own edification. In the 1980s, just as in

Dewey’s time, Kolb’s experiential learning theory was viewed as counter-cultural to mainstream

transmission-oriented techniques. The SCP echoes these early views of experiential learning

through projects; knowing and doing were integrated during SCP work, and students chose their

own topic and project type.

Based on the work of Dewey (1938) and Kolb (1984), I classify SCP as a form of PjBL.

PjBL is defined in part by its broad interdisciplinary focus (Harada et al., 2008; Newell, 2002).

Definitions of PjBL do not reflect solely on core curriculum but often contain the development

of various knowledge and characteristics (skills, abilities, or dispositions) but are not limited to

problem solving and higher-level cognitive development (Markham et al., 2003; Wurdinger,

Haar, Hugg, & Bezon, 2007); student led planning (Markham et al., 2003; Newell, 2002);

student influenced inquiry and investigative activities (Blumenfeld et al., 1991; Markham et al.,

25

2003); and communication (Markham et al., 2003). The characteristics from the aforementioned

authors helped describe what PjBL work entails; however, Thomas (2000) compiled the most

comprehensive definition that best reflects my research on SCPs, saying that complex projects

are “based on challenging questions or problems, that involve students in design, problem-

solving, decision making, or investigative activities; give students the opportunity to work

relatively autonomously over extended periods of time; and culminate in realistic products or

presentations” (p. 1).

Blumenfeld et al.’s (1991) article detailed two essentials needed for comprehensive PjBL:

(1) a problem or question that drives activities; and (2) the activities that result in a series of

artifacts culminating in a final product. The authors described how factors in project design,

teacher implementation, and technology support student motivation and cognition. The two

essentials were seen to provide even greater potential for motivated learning with sustained

thought when students were responsible for the creation of authentic real-world questions and

activities. Projects were described to improve competence in thinking through practice with

planning, progress monitoring, and evaluation. Blumenfeld et al. (1991) also indicated

interdisciplinary projects were effective in engaging students in the active learning process

towards meaningful content knowledge acquisition.

The development and implementation of the Hawai’i SCP (HIDOE, 2010) follows the

descriptors in this review of PjBL literature, and as Hawai’i is the location of investigation for

my study, I consider the SCP to be a form of PjBL. Particularly, the HIDOE (2010) guidelines

for the SCP contain Blumenfeld et al.’s (1991) essentials of a driving question (thesis statement)

and a final product (presentation or research paper). The HIDOE SCP is also representative of

Thomas’ (2000) PjBL definition containing complex tasks that involve students in design,

26

problem-solving, decision making, or investigative activities over an extended period of time.

PjBL is designed to provide lasting effects gained from experiential interdisciplinary learning.

The HIDOE (2010) SCP requirements also mirror the design suggested by the following PjBL

instructional models.

Instructional methods for project based learning. Krajcik, Blumenfeld, Marx, and

Soloway (1994) provide direction for cross-curricular, hands-on learning experiences specifying

that PjBL include a collaborative model for teacher implementation. After reviewing several case

studies that implemented project based instruction methods in science classrooms, the authors

introduced their Framework of Project-based Science that contained five fundamental features:

(1) a driving question or authentic problem used to organize concepts; (2) a main product or

series of artifacts; (3) investigation around a driving question or essential problem; (4)

collaboration with community members; and (5) the use of cognitive tools during the inquiry

process or the development of artifacts. Each of the features was seen to follow aspects of

constructivist learning. The five fundamental features Krajcik et al. (1994) detailed are included

in SCP guidelines (HIDOE, 2010) and were intended to develop learning experiences with

expected outcomes that prepare students for future learning.

Learning Transfer

Learning transfer was used as a conceptual lens for my study which examined college

students’ perspectives of their transference of previously acquired knowledge from their high

school SCP for their current college academic experience. To study learning transfer,

performance on a task can be examined for the degree to which it influences the performance on

a subsequent task (Ellis, 1965); or how prior learning affects new learning or performance

(Marini & Genereux, 1995). It is important to note the field’s wide ranging and often divided

27

perspectives and contradictory viewpoints (Anderson, Redder, & Simon, 1996; Greeno, 1997;

Lobato, 2006; Tuomi-Gröhn & Engeström, 2003) on this topic. In my literature review of the

topic, I approached this spectrum of perspectives by first offering a brief overview of traditional

transfer. Then, the focus shifted to alternative perspectives, primarily the actor-oriented

perspective (Lobato, 2003), which sought understanding transfer from the learner’s viewpoint;

meanwhile, the preparation for future learning perspective (Bransford & Schwartz, 1999)

emphasized that a student’s ability to learn was due to their past experiences. These alternative

perspectives are included in this section due to their broad description of learning transfer as the

ability to apply past knowledge to a new problem or setting, mirroring Royer, Mestre, and

Dufresne’s (2005) multidisciplinary viewpoint that transfer takes place over multiple contexts.

Explanations are also provided regarding my rationale for seeking alternative perspectives to

traditional learning transfer; particularly in relation to the qualitative nature of my study and its

investigation to determine if and how learning transferred from my participants’ high school SCP

experience to their current collegiate experiences.

Traditional learning transfer perspectives. In his seminal book, Principles of

Teaching, Based on Psychology (1906), Thorndike explained his transfer theory as the

application of knowledge from one situation to another. He described the use of quantitative

transfer tests to examine perceived benefits of various learning experiences. Thorndike supposed

that in order to study transfer, identical elements in each case needed to be present and the

specific content of one situation directly applied to the next. Often participants received

instruction on a sequence of learning tasks and were compared to a control group who did not

receive the instruction, and then both groups performed a final task that was used as the basis of

28

measurement. Positive transfer was said to have occurred if the participants who received the

learning tasks performed better than the control group.

Judd (1936) saw transfer differently; he thought Thorndike’s (1906) identical elements

methods only studied learning as a reflex, without effort or mindful thought. Judd (1936) defined

learning as reflection, calling upon a higher mental process. He believed that teachers should

actively teach for transfer and that learners should actively seek to learn for transfer. He found

that the understanding of a task’s central principles transferred to other similar tasks.

Disagreements and tension between cognitive constructivists like Thorndike and situated

cognition theorists like Judd predicated over notions of measuring learning transfer (Tuomi-

Gröhn & Engeström, 2003). Cognitivists viewed situated cognition theorists’ work as inferior

due to their use of unscientific measures. Situated cognition theorists viewed cognitive

constructivists’ work as invalid due to narrow and inequitable viewpoints (Tuomi-Gröhn &

Engeström, 2003). For the purpose of my qualitative study, I followed the situated cognition

theorists views and investigated following alternative learning transfer perspectives described in

the next section.

Alternative learning transfer perspectives. In the 1990s, new considerations for

transference became issues of discussion for scholars in the field (Anderson et al., 1996; Greeno,

1997; Lobato, 2006; Tuomi-Gröhn & Engeström, 2003). Debates based on differing viewpoints

of what needed to be present to constitute transfer became common. The concept of

polycontextuality emerged as a method to provide proper measurement of transfer of participants

engaged in multiple simultaneous tasks over numerous communities of practice (Tuomi-Gröhn

& Engeström, 2003). Barnett and Cici (2002) later explained another topic of much debate—far

transfer. Near transfer was seen to occur when previous knowledge was applied to new but

29

similar situations, and far transfer referred to dissimilar situations. They supported far transfer

was possible and focused on its degree of occurrence. Barnett and Cici (2002) proposed a

framework of nine relevant dimensions to study far transfer across varied contextual and content

dimensions.

Aspects such as motivation, engagement, and participation were seen to influence

transfer. Perkins and Salomon (2012) described a motivational and dispositional view of transfer

that included studying participants as they proceeded through a sequence of three steps: detecting

a potential connection to prior learning, electing to pursue it, and connecting it to a model. The

authors described that a combination of personal characteristics such as persistence and

willingness to take risks disposed students to advance themselves through the steps and transfer

knowledge. Perkins and Salomon suggested that educators would need to explicitly teach critical

thinking and creativity in the classroom to build character as well as cognition. Other learning

transfer studies found that engagement (Carraher & Schliemann, 2002), motivation, and

achievement goals (Belenky & Nokes-Malach, 2012) also enhanced future learning. When

individuals were engaged and motivated, they reconstructed their understanding of initial

learning to improve their knowledge transference to a new setting (Belenky & Nokes-Malach,

2012; Carraher & Schliemann, 2002). Greeno (1998) described how situated transfer included

patterns of participation—how understanding content knowledge and the level of participation

influenced student learning in the current situation and ability to participate in the next situation.

He recognized that patterns of participation, not just task knowledge, transferred across

situations.

These represented scholars described varying alternative perspectives to traditional

transfer study. Commonalities of their approaches included the concept of polycontextuality and

30

methods beyond a quantitative examination of identical elements. Royer et al. (2005) described

alternative approaches as multidisciplinary, applying past knowledge to a new problem or

setting. This approach was applied to my study, in part, because the like elements needed for

traditional transfer study did not exist for my research due to the multiple contexts that were the

subject of investigation. My study examined dissimilar situations of far transfer (Barnett & Cici,

2002) and followed the concept of polycontextuality (Tuomi-Gröhn & Engeström, 2003);

participants’ engagement over in multiple contexts (the high school SCP requirements and

college work samples) over several communities of practice (from the high school SCP to

college academic setting).

The remainder of this section on learning transfer will provide full descriptions of two

broader perspectives that enabled study of learning transfer without the need for identical

elements and quantitative measurement as Thorndike (1906) suggested. From the varying

alternative approaches, I selected the actor-oriented perspective (Lobato, 2003) and the

preparation for future learning (Bransford & Schwartz, 1999) amongst many available. The

founders of these approaches sought enhanced descriptions of a phenomenon often excluded

through traditional examinations of transfer. The actor-oriented perspective described studying

transfer through the participants’ viewpoint and the preparation for future learning described

looking beyond identical elements in the same time-sensitive case. The broader qualitative

methods of these alternative perspectives informed my study by providing approaches to gain the

participants’ viewpoints on how and what, if at all, they transferred learning from a previous

setting (high school SCP experience) to a new setting (college academic experience).

Actor-oriented perspective. In her review of design features of alternative perspectives on

the transfer of learning, Lobato (2003) included her own actor-oriented perspective. She defined

31

transfer as the personal construction of the generalization of learning, where the influence of the

learners’ prior activities impacted their activity in a new situation. She proposed studying

transfer broadly through qualitative observations and eliciting the participants’ perspective. The

actor-oriented framework advocated for a shift from the observer’s to the actor’s viewpoint. The

observer sought to understand the processes by which learners (actors) generate their own

relations of similarity rather than by quantitative measures (Lobato, 2003). The actor-oriented

perspective evolved from Lobato and Siebert’s (2002) study, where they performed two

methodologically different analyses on a single case study. After implementing a teaching

experiment, they compared results from the traditional transfer perspective, using quantitative

methods, with the actor-oriented perspective, using ethnographic interview methods. They found

failure of transfer with the traditional results; however with the alternative method, they

documented several ways that the transfer situation was influenced by prior learning experiences.

Lobato and Siebert (2002) concluded that the classical transfer perspective did not capture all the

nuances of transfer, but recommended that learning be viewed more broadly through the actor’s

viewpoint to divulge multiple aspects of transfer.

The actor-oriented transfer perspective’s foundation, to examine transfer of past

knowledge broadly from the learner’s viewpoint, is relevant to inform my research as it also

sought to understand any transference of learning from its participants’ perspectives. The actor

oriented perspective further suggested its usefulness to my study by its application of the

qualitative interview method. Furthermore, the actor-oriented perspective was seen as a

multidisciplinary approach (Royer et al., 2005) used to study the ability to apply past knowledge

to a new problem or setting.

32

Preparation for future learning. Bransford and Schwartz (1999) reviewed existing

research and proposed a novel approach to thinking about learning transfer for educational

practice and research. The authors described a pessimistic view of transfer evidence due to the

more traditional perspective of measuring a direct application of knowledge by what they

described as sequestered problem solving—where the subject was unable to seek help, receive

feedback, or have an opportunity to revise. Bransford and Schwartz (1999) broadened traditional

transfer with an alternative perspective of its effects on new learning in varied settings. They

proposed the Preparation for Future Learning (PFL) framework which emphasized that a

student’s ability to learn is heavily influenced by their past experiences. The PFL approach

posited that it is not until a student has an opportunity to learn by applying new information, or

utilizing new processes, was he/she able to realize the usefulness of prior knowledge (Bransford

& Schwartz, 1999). Their framework was intended to be used to study a wide variety of learning

experiences in environments that may be adapted to fit previously acquired knowledge. In

opposition of the identical elements required by traditional transfer, the authors believed that

active transfer could be examined when past understandings were adapted to new situations,

settings, and goals (Bransford & Schwartz, 1999).

The PFL approach was selected to inform my research due to its importance for

understanding that the usefulness of prior knowledge may only be fully realized at a later time

when it was applied to new and different settings. Earlier in this chapter (see p. 20), Egelson et

al.’s (2002) conclusions indicated the effects of the SCP may not be realized until students have

graduated high school and are in a setting such as an institution of higher education where they

are required to use their project related skills and knowledge. My study used the PFL approach to

examine college students’ perspectives about previous learning that was utilized in a new setting.

33