CHARTERED

PROFESSIONAL

ACCOUNTANTS

CANADA

The real story behind

housing and household

debt in Canada:

Is a crisis really looming?

Francis Fong, Chief Economist, CPA Canada

18-08-040340

ii The real story behind housing and household debt in Canada: Is a crisis really looming?

© 2018 Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada

All rights reserved. This publication is protected by copyright and written permission is required

to reproduce, store in a retrieval system or transmit in any form or by any means (electronic,

mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise).

Electronic access to this report can be obtained at cpacanada.ca

ABOUT CPACANADA

Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada) is

one of the largest national accounting organizations in the world,

representing more than 210,000 members. Domestically, CPA Canada

works cooperatively with the provincial and territorial CPA bodies

who are charged with regulating the profession. Globally, it works

together with the International Federation of Accountants and the

Global Accounting Alliance to build a stronger accounting profession

worldwide. CPA Canada, created through the unification of three

legacy accounting designations, is a respected voice in the business,

government, education and non-profit sectors and champions

sustainable economic growth and social development. The unified

organization is celebrating five years of serving the profession,

advocating for the public interest and supporting the setting of

accounting, auditing and assurance standards. CPA Canada develops

leading-edge thought leadership, research, guidance and educational

programs to ensure its members are equipped to drive success and

shape the future. cpacanada.ca

iiiThe real story behind housing and household debt in Canada: Is a crisis really looming?

Table of Contents

Executive Summary 2

1. In troduction 5

2. Canada’s housing problem, in a nutshell 6

3. More than meets the eye when it comes to mortgage debt 8

4. Canada’s system simply does not share

any of these problems 11

5. The range of players and practices are

also dramatically dierent 15

6. Private label market is less of a concern 18

7. Detecting credit issues is key, and Canada is

not without signs of potential problems 21

8. Mor tgage aggregators add another layer of confusion 25

9. A lot needs to go wrong before this happens 26

10. Canada’s biggest housing risk is also the most obvious 29

11. Concluding remarks 33

12. Bibliography 34

2 The real story behind housing and household debt in Canada: Is a crisis really looming?

Executive Summary

There can be no doubt that household debt and overvaluation in the

housing market are among Canada’s largest domestic economic risks.

With the 2006-08 housing crash in the US and subsequent financial crisis

still fresh in our collective memory, Canadians are rightly concerned that

we may be headed in the same direction. Indeed, the statistics underlying

the housing market do appear to emphasize this possibility. Household debt

continually hits record levels with each new data point, while home prices

have already grown beyond what average Canadians are able to aord.

Yet, there is far more to this story than the headline statistics suggest.

The underlying data indicate that Canada does not share the credit quality

issues that plagued the US housing boom-bust cycle, such as the prevalence

of subprime mortgages. In contrast, credit quality has actually improved

alongside the growth in home prices. There are also substantial dierences

between Canada’s mortgage market and that of the US and others. The way

in which Canada uses mortgage securitization, a much higher concentration

of mortgage activity among fewer financial institutions, and even a stricter

regulatory regime all help contain the risk presented by record levels of

household debt.

This is not to say that Canada is without risk. A growing share of the

mortgage market is made up of less-regulated financial institutions beyond

the big banks. In addition, recent data show that nearly a quarter of new

borrowers hold debt exceeding 450% of their income – a level far beyond

the 170% debt-to-income ratio at the national level that is normally quoted –

making them significantly more vulnerable to the current rising interest

rate environment.

Ultimately, the headline statistics belie a more complex underlying narrative

and this issue is central to Canada’s financial sustainability. An economic

event or cyclical downturn in housing that triggers a deleveraging episode

among Canadian households could have severe implications for the financial

system and the broader economy.

So this important issue is not black or white. Recall that high home prices

and household debt in the US prior to 2008 sparked similar concerns.

But there were many other factors involved in turning their housing problem

into an economic crisis. The ubiquitous spread of low credit quality

mortgages, such as subprime, the indiscriminate insurance and mass

3The real story behind housing and household debt in Canada: Is a crisis really looming?

securitization of said mortgages for the purpose of being sold o to

banks and investors, lax regulation, and insucient capital buers were

all equally important ingredients.

Canada’s mortgage finance system shares very few of those other factors.

According to Equifax, the share of homebuyers with very good or excellent

credit quality actually rose from 81.5% to 84% between 2013 and 2017. For

new homebuyers, the improvement is even larger, with the share increasing

from 79.4% to 82.4%. This suggests that home price gains are being driven

by those who can actually aord such prices. Credit quality is the most

important factor: without poor-quality mortgages like subprime permeating

the financial system, the possibility of widespread losses on mortgages which,

in turn, could trigger a financial crisis, is far lower. By extension, ensuring

that credit quality remains high is critical to the ongoing stability of both the

Canadian housing market and the broader economy.

The risk is further lessened by a much higher concentration of mortgage

activity in Canada among fewer financial institutions and the way those

institutions use securitized mortgages.

The core mortgage system is made up primarily of larger chartered banks

and the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, the latter insuring

the majority of mortgages while also controlling nearly all of the mortgage

securitization activity in Canada. In total, nearly 75% of all mortgages are

held by banks, while 74% of all mortgage-backed securities are issued

by those same institutions. This has both positives and negatives. On the

positive, a more concentrated market means that regulators have a simpler

task of tracking whether or not credit quality issues are bubbling up. This

is particularly important for the mortgage securitization market, which is a

critical funding tool for nearly every mortgage originator in the country. And

in contrast with the US, where mortgage activity was far more dispersed

and mortgages were being securitized purely for sale, more than 40% of

securitized mortgages in Canada are retained by the financial institution itself

for regulatory purposes. So the incentive for larger financial institutions to

originate low credit quality mortgages is far lower, thereby lessening the risk

of a systemic problem.

On the negative side, however, a more concentrated market also implies that

should any credit risk somehow find its way into the system, the risk is far

greater. And Canada is not without its own risks.

4 The real story behind housing and household debt in Canada: Is a crisis really looming?

Specifically, non-bank lenders and other less-regulated players, such as

mortgage aggregators, are playing a growing role in the mortgage market,

particularly with regards to securitization. These financial institutions have seen

their share of the primary mortgage-backed securities market rise significantly

in the past decade, increasing from 1.2% to 15.8% since 2005. While these

market participants technically have to follow the same rule book as the

larger banks, there is still a question about whether less-regulated lenders are

conducting the same level of due diligence on their borrowers as the larger

incumbents would. This could potentially be a source of systemic credit risk

given their growing role in the core of the mortgage finance system.

The biggest risk to Canada’s housing market, ironically, is and has always been

its most obvious risk. A recent Bank of Canada study estimated that while the

total household debt-to-income ratio exceeds a record 170%, the share of new

borrowers taking on uninsured mortgages with over 450% debt-to-income was

22% between 2014 and 2016 (Coletti et al, 2016). The vulnerability of these

households to a rising interest rate environment has come into question since

the Bank of Canada began hiking interest rates. Mortgage rates are roughly 100

basis points higher since the summer of 2017, at the time of writing, with more

hikes likely to come slowly over time. This could potentially force a significant

number of households into a dicult financial position, which could then trigger

a broader slowdown in both housing and economic activity. This risk is further

raised by the possibility that escalating trade taris with the US will force a

slowdown in economic activity and an increase in the unemployment rate.

Yet fundamentally, credit quality appears to be strong and improving over

time. Systemic risks appear relatively well-contained. Even if there were

something sinister bubbling underneath the surface, the banking system is

far better capitalized than banks were prior to 2008. Insured mortgages and

mortgage-backed securities are explicitly guaranteed by the Canada Mortgage

and Housing Corporation, and by extension, a federal government in relatively

good fiscal standing. Even the Bank of Canada stands ready with extraordinary

liquidity programs to help address funding shortfalls.

So we should consider the possibility that, given Canada’s relatively healthy

financial system, the current level of home prices is justified and that significant

downward pressure is unlikely to occur. This is perhaps the most terrifying

threat of all: not an imminent economic crisis, but the possibility that homes

may never be aordable for those who are already priced out; that, on their way

to becoming world class, our major cities stopped being the bastions of equal

opportunity we like to think they are. This may simply be what Canada is now.

5The real story behind housing and household debt in Canada: Is a crisis really looming?

1. Introduction

Household debt and housing are often cited as the largest domestic economic

risks facing Canada today. With household debt and home prices at record

levels, many have speculated that this level of activity is unsustainable

and will eventually correct in spectacular fashion – similar to the 2008-09

financial crisis in the US. Indeed, the vulnerability to an economic shock is

disconcertingly high – the recent pullback in housing activity has even given

some cause to speculate that we are now in the midst of said correction.

However, there is more to this story than meets the eye. Household debt and

elevated home prices are not sucient on their own to generate an economic

crisis. The 2008-09 financial crisis actually shows us which ingredients are

necessary to transform a cyclical downturn in housing into a full-blown crisis.

And Canada has, perhaps surprisingly, very few of those ingredients.

This report goes beyond the headlines about household debt and home prices

and investigates the institutions and systems underlying Canada’s

mortgage

finance market in order to decode whether there is truly systemic risk embedded

in the financial system. This is a critical question: how this particular risk

evolves will have a direct impact on the ongoing stability of the financial

system and thus the Canadian economy, and understanding that risk is key

to ensuring that it remains contained.

6 The real story behind housing and household debt in Canada: Is a crisis really looming?

2. Canada’s housing

problem, in a nutshell

It is not surprising that there are widespread fears that Canada’s housing

market may be headed for a significant downturn. Indeed, on the surface,

many of Canada’s main housing indicators flash serious warning signs that

the market may be headed for a significant correction. Total household

debt outstanding, for example, has doubled since 2006, in dollar terms.

Meanwhile, debt as a share of personal disposable income (PDI) has been

on an unrelenting uptrend, continuously hitting fresh records with each new

quarterly data point. Canada’s debt-to-PDI ratio has risen well beyond even

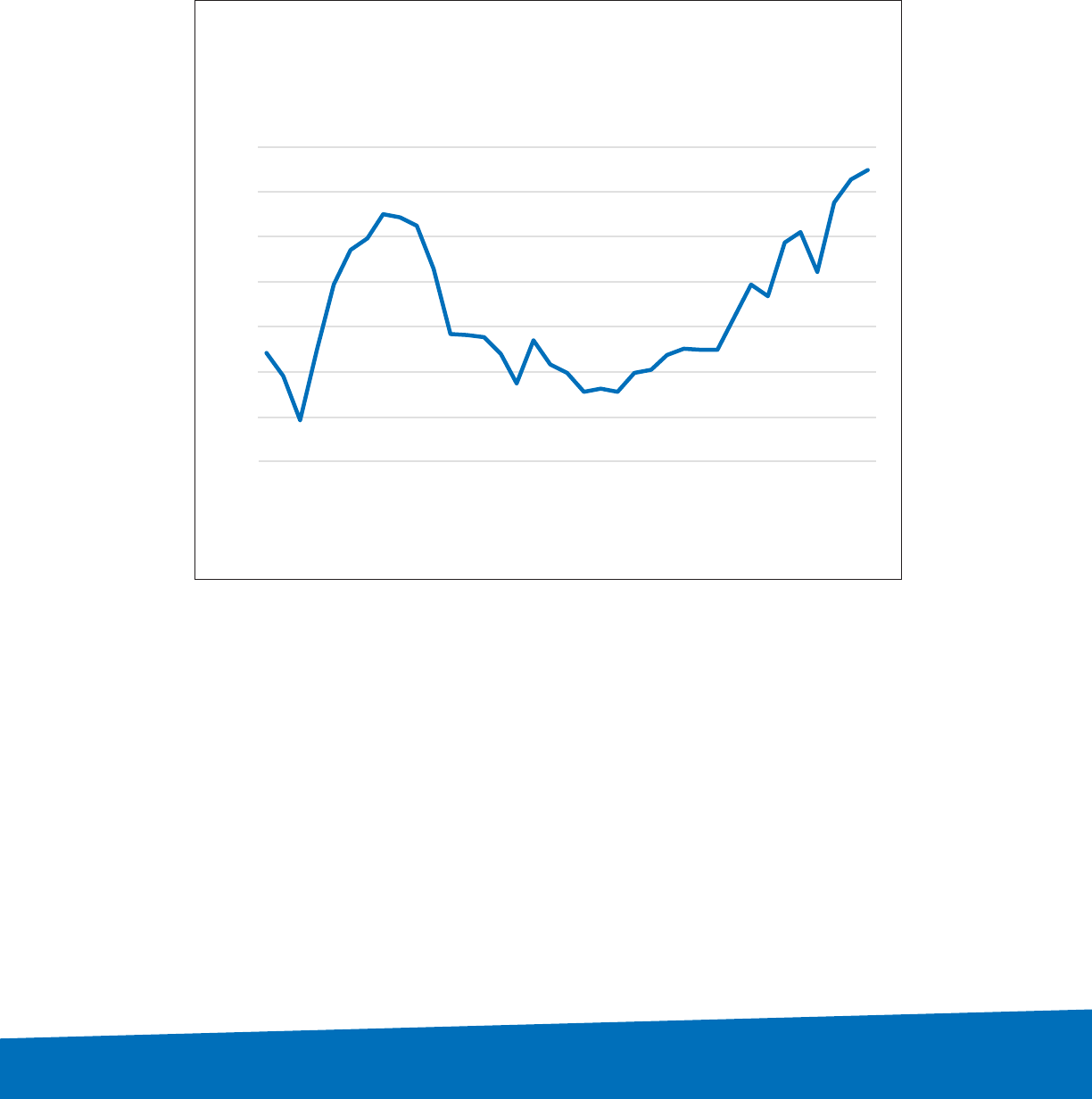

the peak in the US prior to its housing crash in 2006 (Chart 1).

Chart 1: Household Debt in Canada*

and the United States

80%

90%

100%

110%

120%

130%

140%

150%

160%

170%

1990

1992

1994

1996

1998

2000

2002

2004

2006

2008

2010

2012

2014

2016

2018

Canada

US

% of personal disposable income

*US-equivalent definition; Source: Statistics Canada, Federal Reserve Board

7The real story behind housing and household debt in Canada: Is a crisis really looming?

This continuous increase in household leverage has mostly benefited the

housing market – three-quarters of total household debt growth has been in

residential mortgages. This can easily be seen in the rapid pace of price gains

in Canada’s largest cities in recent years. Prior to the recent downturn in the

Greater Toronto Area, for example, it took just six years for home prices to

double. At its most extreme, prices rose by more than 40% in just eighteen

months between the beginning of 2016 and the middle of 2017. And even after

the modest correction of the past several months, the average price for a

detached home is still well over $1 million. Similarly, in Vancouver, homes

in 2018 are worth twice what they were just eight years prior, and average

prices exceed even those in Toronto.

But contrary to the focus on Toronto and Vancouver, this is not simply a tale

of two cities. A similar story has played out all across the country. Ottawa’s

home prices doubled over the same time frame as in Vancouver. Prices in

Victoria have risen by more than 40% just in the past two years. And despite

a major crash in commodity prices driving up unemployment in Alberta and

Saskatchewan in the past several years, home prices in places such as Calgary,

Edmonton, Saskatoon, and Regina have seen only modest downward pressure

and are still double what they were a decade ago.

Observers also point to rental metrics as indicators of housing market

tightness. The home price-to-rent ratio, which has also risen far above historical

norms, highlights how much more expensive housing carrying costs tend to

be relative to average rents. Meanwhile, historically low rental vacancy rates

underscore how aordability problems are pushing would-be buyers into the

rental market and putting pressure on the very limited rental stock. In Toronto,

for example, the vacancy rate fell to just 1.1% as of 2017 – its lowest level since

2001. Meanwhile, Vancouver’s vacancy rate has averaged a record low of

0.8% in the past 2 years.

The combination of these statistics paints a vivid narrative that Canada is

highly vulnerable to a housing-related shock. The aggregate debt-to-PDI ratio

is less concerning than the unknown share of highly leveraged borrowers

who may have pushed themselves too far in order to be able to aord these

extremely high levels of home prices. Numerous surveys have contributed to

this uncertainty, pointing to large swathes of borrowers self-reporting that they

are not able to aord even minimal increases in housing carrying costs, such as

an increase in interest rates. The vulnerability thus stands that an interest rate

shock or an unemployment rate shock could push these borrowers into default,

triggering a US-style housing correction here in Canada.

8 The real story behind housing and household debt in Canada: Is a crisis really looming?

3. More than meets the

eye when it comes to

mortgage debt

That is typically where the narrative ends, but there is more to this story.

In reality, high levels of household debt and home prices may be necessary

pre-conditions for a housing crash, but they are not enough on their own.

Policymakers and economists have since learned from the 2008-09 financial

crisis which ingredients are sucient to generate such a severe shock. And

Canada’s current situation shares fewer of those than the headline statistics

might suggest.

Between 2004 and 2006, in the lead-up to the US housing crash, nearly 20%

of US mortgage originations were subprime (Chart 2).

Chart 2: Subprime Mortgage

Originations – United States

0

5

10

15

20

25

2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006

% of total mortgage originations

Source: Gorton (2008)

9The real story behind housing and household debt in Canada: Is a crisis really looming?

In other words, a significant share of borrowers who were taking on mortgages

at the time had the least ability to actually carry those housing costs. This

concern is further underscored by the types of mortgages they were taking

on. Over those same years, roughly 25% of all originations featured either

“interest only” or “negative amortization” payments (Chart 3) – these types of

loans allowed borrowers to avoid principal repayments or make payments that

were even less than the calculated interest, regularly adding to the outstanding

principal of the mortgage.

Chart 3: Interest Only and Negative Amortization

Mortgage Originations – United States

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006

% of total mortgage originations used for purchase

Source: Baily, Litan, and Johnson (2008)

- -

II

I

These types of loans increased access to the mortgage market for those who

previously would not have been able to aord homeownership. However, the

cost was a high degree of financial vulnerability for large swathes of borrowers

who depended on continual refinancing in order to keep their mortgage

payments low. Lenders, in turn, were only willing to do so on the basis of

continued increases in home prices.

10 The real story behind housing and household debt in Canada: Is a crisis really looming?

The mortgage market thus became saturated with these high risk, low credit

quality assets that, simultaneously, financial institutions were insuring and using

to create asset-backed securities, such as mortgage-backed securities (MBS)

and collateralized debt obligations (CDO). Between 2001 and 2006, the share

of subprime mortgages being securitized rose from roughly 50% in 2001 to

over 80% in both 2005 and 2006 (Gorton 2008). Such a high percentage is a

clear indication that mortgage originators were not concerned with the credit

risk of the mortgages being issued, because they were being originated for the

purpose of being packaged and sold, rather than being held.

Indeed, these complex derivatives were then being marketed as low-risk, high-

yielding assets to systemically-important US financial institutions. By 2008, US

banks and government-sponsored enterprises were holding more than US$1.5

trillion in agency mortgage-backed securities and nearly US$700 billion in

non-agency AAA-rated CDOs (i.e. private label securities). Both of these types

of assets would ultimately have significant credit exposure to the underlying

subprime mortgages. When the housing market turned south and the

inevitable wave of borrower defaults began, these financial institutions were

ultimately the ones faced with massive losses on any and all related assets.

Insolvencies and bankruptcies among a massive range of financial institutions

resulted, leading to even more losses among the creditors that provided their

funding, leading to a dramatic tightening of credit conditions that ultimately

brought down the rest of the US economy.

It is important to stress, at this point, that the severity of the 2008-09 financial

crisis in the US was ultimately the result of a multitude of factors. Without the

volume of subprime mortgages being originated, there would be no assets to

securitize and sell. Without the ability to securitize and sell mortgages, there

would have been no incentive to originate as many subprime mortgages as

lenders did. Without insurers and credit rating agencies, these assets would

not have been able to attract buyers. Without money market mutual funds and

other lenders, there would not have been sucient funding for this problem

to grow to the size it did. Hundreds of players had their role to play, including

private insurance companies, government-sponsored enterprises, credit rating

agencies, traditional banks, investment banks, mortgage originators, mortgage

brokers, asset management companies and mutual funds. The crisis was the

culmination of all of it.

11The real story behind housing and household debt in Canada: Is a crisis really looming?

4.

Canada’s

system simply

does not

sh

are any of

these problems

Relative to the US, the fundamentals of Canada’s mortgage finance system are

starkly dierent. Most critically, Canada’s housing market has not been driven

by growth in low credit quality mortgages, despite the impression given by

rapid price gains. Rather, credit quality has actually improved over time.

Two data points support this contention. The first comes from the Canada

Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC), which is the largest insurer of

mortgages in Canada and also administers and guarantees the country’s

primary mortgage securitization program, the National Housing Act (NHA)

MBS program. Data on the portfolio of mortgages that it insures show that

the share of borrowers with high credit scores has grown from an average of

65% between 2002 and 2008, to 88% as of the 3rd quarter of 2017 (Chart

4). Meanwhile, the share of borrowers with lower credit quality has fallen

dramatically, particularly those with the lowest credit scores, whose share has

fallen from 4% in 2002 to nearly 0% as of last year.

Chart 4: Distribution of CMHC-Insured

Mortgage Loans, by Credit Score at Origination

% of outstanding loans

Source: Canada Mortgage & Housing Corporation

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

2002

2004

2006

2008

2010

2012

2013 Q2

2013 Q4

2014 Q2

2014 Q4

2015 Q2

2015 Q4

2016 Q2

2016 Q4

2017 Q2

Annual

Quarterly

700 and over

660-699

600-659

Under 600

I

I

-------

12 The real story behind housing and household debt in Canada: Is a crisis really looming?

The CMHC data technically do not represent the majority of mortgages in

Canada, so the fact that credit quality is so good within the program does

not necessarily suggest that the entire market is free from poor credit quality

mortgages. But the integrity of the NHA MBS program is important for a

dierent reason.

When the US housing market turned in 2006 and financial institutions began

facing losses on their mortgage portfolios, investors began to flee out of

mortgage-backed securities and other assets backed by real estate. Financial

institutions involved in originating and selling such assets not only faced losses

on those securities they could not sell, they also lost an incredibly important

funding tool. Financial institutions securitize assets and sell them to fund their

operations. The NHA MBS program is no dierent.

So even if it doesn’t account for a significant share of the mortgage market,

the integrity of the NHA MBS program is of paramount importance – if there

were to be a credit quality issue and the housing market went bust, investors

would invariably fear purchasing any more NHA MBS and banks and other

mortgage originators would lose a critically important funding tool.

At the height of the crisis in 2008, despite Canada’s largest banks having

had minimal exposure to the US subprime mortgage market, the Department

of Finance still instituted an emergency liquidity measure called the Insured

Mortgage Purchase Program (IMPP) to, in a way, backstop the NHA MBS

program. The IMPP was designed to act as a demand backstop in which the

central bank would inject funding into the core banks by purchasing insured

mortgages directly in case investors did indeed lose confidence in holding

NHA MBS.

The backstop was ultimately not needed, but it does reinforce the importance

of this program. The fact that credit quality is very good and has been

improving over time suggests that policymakers have recognized the need to

further protect the program from exposure to credit risk.

As shown below, however, insured mortgages have actually become the

exception, rather than the rule. Changes made to mortgage insurance

regulations by both CMHC and the federal Department of Finance have made

eligibility more restrictive. For example, mortgage insurance is capped on

homes worth more than $1 million. Given how high home prices have risen,

even modest detached properties in the largest urban centres go beyond that

price tag, meaning that a large share of borrowers are not eligible.

13The real story behind housing and household debt in Canada: Is a crisis really looming?

It is thus no surprise that approximately 82% of mortgage originations are

actually uninsured (Chart 5), a share that has increased sharply in the past

several years, and therefore would not be covered by the CMHC data. So even

if the NHA MBS program were clean, credit risk could easily have crept into

the uninsured space.

Chart 5: Uninsured Mortgage

Originations in Canada

50%

55%

60%

65%

70%

75%

80%

85%

1982

1984

1986

1988

1990

1992

1994

1996

1998

2000

2002

2004

2006

2008

2010

2012

2014

2016

2018 YTD

% of total originations

Source: Bank of Canada

However, according to data from Equifax, which covers the large majority

of the mortgage market in Canada and so would include both insured and

uninsured mortgages, the shift towards higher credit quality still holds. The

proportion of borrowers with either very good or excellent credit quality has

risen from 81.5% in 2013 to 84% as of 2017. Among new borrowers, the shift

is even more pronounced, with the share rising from 79.4% of borrowers to

82.4%. Again, these increases come at the expense of those with lower credit

quality – the share of borrowers with poor credit scores fell from 3.7% to 3.1%

among all borrowers, and from 1.4% to 1.0% among new borrowers over that

same time frame (Chart 6).

14 The real story behind housing and household debt in Canada: Is a crisis really looming?

Chart 6: Mortgage Credit Quality in Canada

Total and New Mortgages

81.5

82.1

83.0

83.5

84.0

79.4

81.3

82.4

83.1

82.4

3.7

3.6

3.5

3.3

3.1

1.4

1.4

1.3

1.2

1.0

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

Q1-2013 Q1-2014 Q1-2015 Q1-2016 Q1-2017

% of outstanding mortgages – very good/excellent credit score

% of new mortgages – very good/excellent credit score

% of outstanding mortgages – poor credit score

% of new mortgages – poor credit score

% of mortgages

Source: CMHC, Equifax

•

•

•

•

The bottom line is that there does not seem to be a systemic credit quality

issue. Without one, the likelihood of a cyclical housing market correction

generating sucient losses among financial institutions to trigger a tightening

in credit conditions would be relatively low. This would make an economic

event capable of pushing the Canadian economy into recession that is purely

centred on housing equally unlikely.

15The real story behind housing and household debt in Canada: Is a crisis really looming?

5. The range of players

and practices are also

dramatically dierent

Beyond the fundamental issue of credit quality, there are several other aspects

of Canada’s mortgage finance system that lessen the overall risk of a cyclical

downturn in housing causing a larger economic crisis. Chief among them is the

concentration of mortgage credit among Canada’s largest financial institutions

and the way in which those institutions use mortgage-backed securities.

The country’s chartered banks account for roughly 75% of total outstanding

mortgage credit, amounting to over $1.1 trillion (Chart 7), a fair amount of

which is held in NHA MBS.

Chart 7: Composition of Mortgage Credit

Outstanding, by Type of Financial Institution,

April 2018

1,139,734

18,948

16,564

58,191

203,234

61,496

12,523

Chartered banks

Trust and mortgage loan companies

Life insurance company policy loans

Non-depository credit intermediaries

and other institutions

Credit unions and caisses

populaires

National Housing Act (NHA)

mortgage backed securities

Special purpose corporations,

securitization

Source: Bank of Canada

$ millions

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

16 The real story behind housing and household debt in Canada: Is a crisis really looming?

This may appear, on the surface, to be similar to the state of the US in 2006

in which banks were purchasing MBS en masse. However, the reality is far

dierent. According to the Bank of Canada, roughly 41% of all outstanding

NHA MBS in 2015 were issued for the purpose of being retained by the

financial institution itself (Chart 8). In other words, Canadian banks were taking

their insured mortgage portfolios, securitizing those assets, then holding

on to the resulting securities. The reason, as the central bank notes, is that

mortgages require a financial institution to hold capital and liquidity buers

against those assets in case of borrower default. A securitized mortgage,

however, still requires capital to be held in case of loss, but the financial

institution is able to relieve the liquidity buer requirement, thus lowering

the overall “carrying cost” of the asset. In addition, NHA MBS can also be

converted into Canada Mortgage Bonds (CMB), which also have the side

benefit of being held as contingent liquidity – high-quality, highly liquid assets

that banks are required to hold that can be sold at a moment’s notice should

the financial institution come under funding stress (Cateau et al, 2015).

Chart 8: Composition of Outstanding NHA

Mortgage-Backed Securities, by Usage,

as of June 2015

50.2%

40.6%

3.5%

5.7%

Sold to the CMB program

Retained by financial

institutions

Syndicated NHA MBS

Other

Source: CMHC, OSFI, Bank of Canada Financial System Review December 2015

•

•

•

•

17The real story behind housing and household debt in Canada: Is a crisis really looming?

In other words, the end result might appear similar relative to the US, but

Canada’s banks are basically holding their own mortgage assets in securitized

form rather than purchasing another institution’s assets.

This changes the incentive completely – US financial institutions were

incentivized to originate mortgage assets, insure, and securitize them with

the sole intention of selling them to another institution, thus allowing the

originating firm to ignore the masked credit quality of the mortgage. Holders

of these assets were, in turn, buying them for the return. In Canada, if nearly

half of all MBS are retained by the financial institution, thus exposing them

directly to their own losses if the mortgage goes into delinquency, then the

incentive is to originate an asset with as high a quality as possible to limit that

risk. They are not holding it for the return since it would be roughly similar

regardless of whether one holds a securitized mortgage or the mortgage itself.

In other words, at least a significant portion of the NHA MBS system avoids the

moral hazard problem that plagued the US MBS market.

18 The real story behind housing and household debt in Canada: Is a crisis really looming?

6. Private label market

is less of a concern

This does not suggest that Canada’s MBS system is completely insulated

from credit risk since there remains the other 60% of the NHA MBS not being

retained by financial institutions that we may need to worry about. In addition,

even if the NHA MBS portfolio were completely clean and risk-free, recall that

in the US, a sizable portion of the MBS market was outside of the government-

backed mortgage insured market. A complex web of entities was involved

in originating, insuring and selling what were referred to as “private label”

securitized assets backed by real estate, which also made up a significant

portion of the poorer credit quality assets that ultimately flooded that market.

A separate contingent of financial institutions was then involved in purchasing

those assets.

Even in the US, with its less concentrated banking system, there still would

have been some level of concentration of mortgage activity among the largest

banks in combination with government-sponsored enterprises such as the

Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae, FNMA) and the Federal

Home Loan and Mortgage Corporation (Freddie Mac, FHLMC). But they did

not operate on an island. Exposure to poor credit quality private label assets

still crept their way into the core of the financial system through either core

banks purchasing these assets directly or through indirect exposure in which a

core bank would face credit exposure to another financial institution that faced

direct losses on its private label mortgage-related assets.

Thankfully, Canada’s private label market is small. Compared to the roughly

$1.5 trillion mortgage market and $483 billion NHA MBS sub-market, private

securitization in total amounted to a relatively small $92 billion at the end of

2017 (Chart 9), only a subset of which would be related to mortgages. So even

if there were significant credit quality issues within this portfolio, the likelihood

of a significant credit event having a knock-on eect on the core financial

system is likely minor.

19The real story behind housing and household debt in Canada: Is a crisis really looming?

Chart 9: Private Label Asset-backed

Securities in Canada

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

180

Mar

2008

Dec

2008

Dec

2009

Dec

2010

Dec

2011

Dec

2012

Dec

2013

Dec

2014

Dec

2015

Dec

2016

Dec

2017

$ billions

Source: DBRS

This is critically important – the high-level concentration of mortgage activity

and the limited scope of mortgage securitization in Canada basically imply that

the largest banks and CMHC act as the “core” of the mortgage market from

both a funding and an origination perspective. This has both positives and

negatives. On the one hand, if credit risk were to creep its way into the core

mortgage system, the potential for significant credit losses at even one large

bank to have a knock-on eect on the rest of the financial system is orders

of magnitude greater than it would be in a country with a more dispersed

mortgage system.

On the other hand, the fact that mortgage activity is concentrated within a

relatively self-contained core suggests that the broader economy may be

insulated from a credit event that may occur among financial institutions,

lenders and others to which the core has relatively little exposure. Canada’s

regulators, such as the Oce of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions

(OSFI), thus have a much easier time tracking systemic credit risk given that

there are physically fewer financial institutions within the core to track. The

largest banks are also subject to a much stricter regulatory regime than banks

20 The real story behind housing and household debt in Canada: Is a crisis really looming?

globally were before 2008 – from higher capital and liquidity buers, to rules

around stress testing, funding stability and overall risk taking – which further

lessens the risk within the core.

Let us consider an example where there are credit quality issues within the private

label MBS market that led to borrower defaults on the underlying mortgages,

losses on the MBS, a loss of liquidity in that market, and insolvencies among those

that depended on that market for funding. However, the core mortgage system

does not have any exposure to either the financial institutions going bust or the

MBS. Such a credit event would certainly have a significantly negative impact on

the borrowers involved and might disqualify them from credit markets entirely.

Such an event might also have a negative spillover eect on home prices and

home sales more broadly. However, if the core mortgage system is unexposed to

any direct or even indirect losses, then Canada’s largest banks and CMHC could

continue to function on a normal basis. Overall credit conditions would not tighten

significantly, and the mortgage market would be broadly unimpeded. The only

dierence is that lower credit quality borrowers who depended on that private

market to access credit would then be forced back into the core banking system,

where they could be subject to tighter rules around income testing and credit

quality, which might result in their ineligibility for a mortgage.

21The real story behind housing and household debt in Canada: Is a crisis really looming?

7. Detecting credit issues

is key, and Canada is

not without signs of

potential problems

The key is thus ensuring that credit risk does not permeate into the core. If

regulators and policymakers are interested in ensuring the ongoing stability of

both the financial system and the housing market, protecting the core mortgage

system from credit risk is vital.

Broadly, there does not appear to be a significant issue, given that the existing

data suggests that credit quality is good and improving over time.

However, this again does not imply that Canada is completely insulated from

credit risk. Rather, Canada needs to worry about a hidden credit quality problem

– for example, whether or not low credit quality mortgages are being masked as

high quality through documentation fraud on the part of borrowers or insucient

due diligence on the part of lenders, etc.

And from this perspective, there is at least one worrying trend: the rising

importance of non-bank mortgage lenders and mortgage aggregators

in Canada.

After the recession ended, mortgage credit extended by non-depository

credit intermediaries (i.e. mortgage lenders that do not have access to deposits

with which to fund a mortgage portfolio like banks and credit unions) grew

significantly faster than any of their competitors. Between the end of 2013 and

the beginning of 2015, year-over-year growth in mortgages held by these lenders

averaged 11.3%, more than double the 4.8% average growth rate posted by the

chartered banks (Chart 10).

22 The real story behind housing and household debt in Canada: Is a crisis really looming?

Chart 10: Mortgage Growth - Chartered Banks

vs. Non-depository Credit Intermediaries

Y/Y % change

Source: Bank of Canada

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

18

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

Chartered Banks

Non-Depository Credit Intermediaries

-

These intermediaries, also known as non-bank lenders or mortgage finance

companies (MFCs), had two distinct advantages over the larger incumbents

during this time. The first was that they are not regulated to the same extent

as the larger banks. If a bank wished to lend to a lower credit quality borrower,

for example, it would be expensive to do so given the capital and liquidity

buers needed to safeguard against the higher probability of loss. Because

those barriers are not applied to MFCs, they can tap a far wider range of

potential borrowers at a much lower cost.

Up until 2013, that regulatory advantage was largely dwarfed by the fact that

banks could oer more competitive interest rates. By nature of their size and

reach, banks have access to a much deeper and more liquid funding pool

than smaller players – lower funding costs mean banks can pass on savings to

customers in the form of lower interest rates.

However, the second advantage for MFCs came in 2013, when CMHC

implemented a policy designed specifically to increase access to the NHA

MBS and CMB programs for a wider range of lenders. CMHC has an annual

allotment of mortgages it can insure and securities it can guarantee. Prior

to this change, the large majority of that annual allotment was taken by the

23The real story behind housing and household debt in Canada: Is a crisis really looming?

largest banks in Canada, leaving little access for other players in the market.

In order to increase competition within the mortgage market, CMHC’s 2013

policy basically allocated the annual cap equally among participants (Coletti et

al, 2016). Being able to fund one’s mortgage portfolio through the NHA MBS

and CMB programs, according to the Bank of Canada, provides a significant

funding advantage, on average, from 11 basis points for NHA MBS to 40 basis

points for CMBs relative to senior unsecured debt (Cateau et al, 2015). Lower

funding costs imply that a lender can oer borrowers a more competitive

interest rate.

In simple terms, MFCs could then compete on par with the larger incumbent

players from a mortgage rate perspective. And because they could tap lower

credit quality borrowers, while also undercutting the banks further due to

lower regulatory costs, they were able to grow much faster. Between 2005

and 2017, the share of NHA MBS outstanding accounted for by non-regulated

entities, which include both MFCs and mortgage aggregators, rose from just

1.2% in 2005 to 15.8% as of 2017 (Chart 11).

Chart 11: NHA Mortgage-Backed Securities –

Remaining Principal Balance Outstanding,

by Type of Issuer

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017

Non-Regulated

Entities

Trust & Loan Co.

Insurance Co.

Credit Unions /

Caisses Pop.

Other banks

Big 5 Banks

% of total outstanding

Source: Canada Mortgage & Housing Corporation

-

-

•

•

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I •

-

-

-

~

;..

-

-

-

-

I-

~

=----

•

•

•

•

•

24 The real story behind housing and household debt in Canada: Is a crisis really looming?

This presents a potential moral hazard problem that could result in lower

credit quality mortgages penetrating the core mortgage finance system. Less

regulatory oversight and the ability to tap lower credit quality borrowers gives

these lenders the incentive to do so. Moreover, a recent Bank of Canada study

in 2016 suggests that banks are now purchasing some mortgages directly from

MFCs. This is because MFCs have a comparative advantage when tapping

mortgages that originate from mortgage brokers, an increasingly popular

way for households to negotiate mortgage rates. Rather than establishing the

infrastructure to deal with the wide network of brokers across the country,

banks purchase the mortgages directly from MFCs in order to diversify their

mortgage portfolios beyond the locations where they have a physical presence.

From a risk perspective, there are now two ways for credit risk to potentially

penetrate the core mortgage finance system. Mortgages originated from

MFCs are now entering the banking system directly via purchases, while also

being securitized into NHA MBS for funding purposes. According to the Bank

of Canada, mortgages originated by MFCs also tend to have higher loan-to-

income ratios and higher total debt service ratios relative to those originated

by banks and credit unions, meaning the loss risk is also greater. Between 2013

and 2016, the Bank of Canada calculated that 29% of mortgages originated

by MFCs had loan-to-income ratios beyond 450% and total debt service

ratios beyond 42%, the latter of which is generally too high to be eligible for

mortgage insurance (Bilyk et al, 2017).

For this to be a problem, however, these lenders need to be originating low

credit quality mortgages and masquerading them as high credit quality

mortgages since the data suggest that credit quality is getting better both

broadly and within the NHA MBS system. This can occur if mortgage brokers

and less-regulated MFCs are not conducting the same level of due diligence as

their larger bank counterparts in ensuring that originated mortgages conform

to the standards in order to be insured. These include borrowers not exceeding

standard total and gross debt service ratios, maximum loan-to-value ratios,

confirmation of a borrower’s income, income stress testing, etc. Should they be

lax in their underwriting processes, then it is possible that a lower credit quality

borrower could pass the tests that they might have failed at a larger, more

stringent lender.

25The real story behind housing and household debt in Canada: Is a crisis really looming?

8. Mortgage aggregators

add another layer

of confusion

Mortgage aggregators take this potential risk one step further. Aggregators

take an originating firm’s mortgages and securitize them on their behalf,

putting an additional layer of obscurity between the originator and the final

investor. Now, an investor depends on both the originator and the aggregator

to have conducted their due diligence on their behalf, presenting one more

layer in which credit quality can be muddled.

Moreover, aggregators do not deal only in residential mortgages, as one might

assume. It is within CMHC’s framework to insure multi-family mortgages –

mortgages extended to developers, renovators and others that are building

or purchasing more than a single unit of housing at a time. These mortgages,

according to the Bank of Canada, originate from the same MFCs discussed

earlier, many of which also have multi-family and commercial lending arms

(Coletti et al , 2016). Mortgage aggregators play a role in establishing a wider

network of potential investors that might be interested in gaining exposure to

the Canadian housing market at an earlier stage than when a homebuyer is

purchasing a home. The risk then is potentially higher as investors are buying

into an income stream backed only by the underlying plot of land and the

potential to develop that into housing rather than a final product with a firm

market value. The mortgage underwriting process is also far dierent for a

multi-family mortgage than a residential mortgage; instead of income testing

and stress testing, it involves ensuring a borrower has sucient net worth and

that the building/property has gone through a proper appraisal, environmental

assessment and other inspections. These complications raise the concern that

investors may not be fully aware of the level of credit risk when purchasing an

MBS backed by multi-family mortgages.

26 The real story behind housing and household debt in Canada: Is a crisis really looming?

9. A lot needs to go wrong

before this happens

There are several mitigating factors that suggest that the risk that low credit

risk is penetrating the core mortgage system is lower than it may sound. The

first is that MFCs and other non-deposit-taking lenders depend heavily on

securitization to fund their mortgage portfolios. The Bank of Canada pegged

this share at over 50% as of the 4th quarter of 2015 (Coletti et al, 2016). CMHC

is not unaware of the possibility and risk of low credit quality mortgages

entering the system – there are strict regulations around the “performance” of

the insured mortgages that make their way into NHA MBS and CMBs. Should

delinquency rates on mortgages within any particular MBS issuance increase

beyond a fairly small threshold, for example, lenders may lose their status as

an “approved lender” of insured mortgages or as an “approved issuer” of MBS.

The incentive for MFCs is thus in favour of ensuring that the credit quality of

their mortgages remains high; otherwise they might lose access to their most

important funding source. The same issue applies to aggregators, as well.

Being an approved issuer implies that the same performance requirements

apply, even if they are not the originator of the underlying mortgages.

Second, the heavy reliance on securitization also means that policy changes

with regards to insured mortgages impact these lenders to a far greater

degree. The recent B-20 guidelines that resulted in stricter rules around

income testing and stress testing, for example, have had a significant impact

on the growth of mortgages among these firms. The double-digit growth that

occurred between 2013 and 2015 has since slowed to less than 1.5% year-over-

year in the past 12 months (Chart 10). This is a positive sign – it suggests that

these firms are actually responding to policy changes and that they were likely

following the rules closely enough for them to have had an impact. If they had

been skirting the rules all this time, then they would continue to do so and the

stricter rules would have had no impact.

Lastly, a 2015 compliance review of mortgage brokers in Ontario, conducted by

the Financial Services Commission of Ontario (FSCO), noted that “in general,

the majority of mortgage brokerages understand the requirements of the

Mortgage Brokers, Lenders, and Administrators Act (MBLAA), and FSCO’s

expectations for brokerages to have complete policies and procedures to

govern their day-to-day activities and ensure compliance with the legislation.”

27The real story behind housing and household debt in Canada: Is a crisis really looming?

It noted that policies and procedures appeared to be adequate given the

nature, complexity and size of the brokerages examined. However, it did find

an “unacceptable decline” in the level of compliance regarding public relations

material and disclosure requirements.

Ultimately, even if there were a significant issue, non-bank mortgage lenders

are actually quite a small part of the mortgage market – in total, they represent

just 3.6% of outstanding mortgage credit (Chart 7). Though this likely

understates the full role played by these firms given that they account for at

least 10% of total NHA MBS and CMB outstanding, they are still dwarfed by the

larger segments of the market, such as that of banks and credit unions.

And even if losses did begin to mount, those losses would still have to exceed

CMHC’s own capital buer held to absorb such losses and the explicit backing

of the insured mortgage market by a federal government in relatively good

fiscal standing. They would also have to be large enough to exceed the well-

capitalized buers of the actual banking system, if losses were to ever spread

and cause a drop in liquidity severe enough to exceed the Bank of Canada’s

ability to step in and provide emergency liquidity through its traditional

programs and through extraordinary programs like the IMPP; not to mention

the Bank of Canada itself notes that mortgages originated by MFCs tend to

have slightly higher credit scores and lower arrears rates relative to those

originated by banks and credit unions (Coletti at al, 2016).

28 The real story behind housing and household debt in Canada: Is a crisis really looming?

What about private lenders?

More recently, concerns have been raised about the spectre of a housing bubble

due to the growth of private lending in the mortgage market – private citizens

using their own capital to lend to borrowers. Several news articles have exposed

this phenomenon.

1

Fundamentally, the risk to the financial system and the economy stemming from

private lending is relatively small. Even if the market were large, it is important

to understand that private loans stand outside of the broader financial system.

Even if lenders were originating mortgages to highly-vulnerable, low credit quality

borrowers and those borrowers began to default, the losses would most likely

impact only the lenders themselves. There is notionally no connection between

private lenders and the broader financial system, so there would be no way for

losses to impact credit conditions and trigger a domino eect of losses.

There is, however, a common concern that the activities of private lenders might

trigger a domino eect of declining home prices that drags down the rest of

the housing market. However, a decline in home prices, even one significant

enough to push borrowers underwater (i.e., their mortgage is larger than what

the house is worth), does not automatically trigger delinquency or force the

b

orrower into fixing the situation. A shift in home prices does not cause lender

s

to reassess all of the properties that underlie its mortgage portfolio, nor do

lenders go after borrowers who fall underwater. So long as borrowers continue

to make consistent mortgage payments, a cyclical or even structural decline in

home prices does not change the status quo.

However, it does mean that borrowers are stuck with their current lenders

and in their current situations as any move to refinance their home, take out

additional equity or switch lenders results in a re-appraisal of the home,

exposing the negative equity situation.

And contrary to the US experience, borrowers cannot simply walk away from

their homes if they owe more than the house is worth. Canada’s loan system

operates on a recourse basis – in a default situation, a lender can go after a

borrower’s other assets to make up the amount owed. So while borrowers in

the US were likely to walk away from homes, leading to the bank holding the

full loss on the asset and the burden of short-selling the property, this is less

likely to occur in Canada.

1 https://torontolife.com/real-estate/how-private-lenders-and-debt-crazed-homebuyers-are-pushing-

torontos-real-estate-market-to-the-brink/

29The real story behind housing and household debt in Canada: Is a crisis really looming?

10. Canada’s biggest

housing r

isk is also

the most obvious

Canada’s mortgage finance system ultimately gives us both cause for concern

and some peace of mind. There are clear pockets of risk in the form of

mortgage finance companies, mortgage aggregators, and the exposure that

the bigger banks and the NHA MBS system have to mortgages they originate.

The possibility that credit risk is a growing problem is all the more serious given

record levels of household debt. Keeping track of whether credit migration is

occurring (i.e. a shift in average credit scores) will thus be key to ensuring the

ongoing stability of Canada’s housing market.

However, as of yet, there is no evidence of something sinister building beneath

the surface, which means the biggest risk to the housing market still remains

a more general correction. And the most likely trigger of that is either an

increase in interest rates pushing borrowers into dicult financial straits or

a shock to the unemployment rate, or both.

In fact, we are already in the midst of the former. The Bank of Canada has raised

interest rates on four occasions since last year, pushing its Overnight Rate target

from 0.50% to 1.50%. Mortgage rates have followed suit, with the rate

on 5-year fixed mortgages having increased by roughly an equal amount over

the same time frame, according to CMHC. OSFI also implemented its much-

debated B-20 guidelines, which, among other things, enforced more stringent

income verification processes and new stress testing rules on uninsured

mortgages. Alongside a series of other regulatory measures implemented by

the governments of BC and Ontario, such as surtaxes on foreign buyers, the

housing sector has faced enormous headwinds in recent months.

Existing home sales have, as a consequence, fallen by more than 20% since the

spring of 2016 and are now at a five-year low, according to the Canadian Real

Estate Association (CREA). Home prices have not been as responsive – on an

average basis, all of the gains recorded since the beginning of 2016 have been

wiped out. However, average prices reported by CREA tend to be skewed b

the composition of sales. On a quality-adjusted basis, prices fell by less than

3% and are already on their way back up. Even in the Greater Toronto Area,

the MLS home price index fell by 9%, but has already stabilized. Prices in the

Greater Vancouver Area recorded an even milder 4% decline and have since

grown by 21% (Chart 12).

y

30 The real story behind housing and household debt in Canada: Is a crisis really looming?

Chart 12: MLS Home Price Index

90

120

150

180

210

240

270

300

2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018

Canada

Greater Vancouver

Greater Toronto

Index, Jan 2005 = 100

Source: Canadian Real Estate Association

Whether there will be further downward pressure on prices remains an open

question. The fact that home sales are so low while home prices appear to

have stabilized could speak to a fundamental imbalance between supply and

demand in Canada’s major cities, or to the possibility that more downward

pressure is yet to come.

The key to answering that question is to gauge the vulnerability of households

to rising interest rates. Numerous surveys had indicated that a significant

minority of borrowers would not have been able to aord even a 1 pertcentage

point increase in interest rates prior to the recent hiking cycle.

2

Several

rate hikes in, and more recent surveys are confirming that many Canadian

households are feeling the pinch.

3

A recent study by the Bank of Canada showed that, among regulated lenders

such as banks and credit unions, 22% of borrowers who took out uninsured

mortgages (i.e. they were able to put down a 20% down payment) between

2014 and 2016 had loan-to-income (LTI) ratios exceeding 450% – a level

considered to carry a high level of vulnerability to rate hikes. Broken down

2 https://www.cbc.ca/news/business/transunion-debt-interest-rates-1.3759844

3

https://mnpdebt.ca/en/blog/trouble-ahead-canadians-increasingly-feeling-the-impact-of-higher-interest-rates

31The real story behind housing and household debt in Canada: Is a crisis really looming?

by income bracket, they also found that the poorest borrowers were the most

likely to be over-indebted – 44% of those borrowers exceeded 450% LTI. This is

potentially a serious vulnerability as we do not know whether lower-income

Canadians have the ability to shift consumption and continue to meet their

mortgage obligations as interest rates rise.

More broadly, the evidence does show that both existing and prospective

borrowers are responding to the interest rate increases, as mortgage growth is

slowing steadily. On a year-over-year basis, household mortgage growth hit 4.4%

in May 2018, its slowest pace since 2000 (Chart 13). The combination of rising

rates, persistently high home prices, low home sales and slowing credit growth

point to the strong possibility that further downward pressure on home prices is

still in the cards. However, that is far from certain, and even then, that pressure

is likely to occur over time as rates slowly rise.

Chart 13: Outstanding Residential

Mortgage Credit in Canada

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

Y/Y % Change

Source: Bank of Canada

The potentially larger risk to the housing market is if the unemployment rate

were to suddenly increase sharply. This is certainly a possibility given the

potential impact of escalating trade taris. And if highly indebted borrowers are

struggling to meet their mortgage obligations in a rising rate environment, that

32 The real story behind housing and household debt in Canada: Is a crisis really looming?

struggle would be far more dicult should Canadians start losing their jobs in

significant numbers. The risk from an increase in unemployment, however, is not

necessarily clear.

Take, for example, Alberta’s experience in 2014. After oil prices crashed, the

provincial unemployment rate doubled from 4.4% to 9%. Yet, despite the 118,900

increase in unemployed Albertans, the mortgage arrears rate rose by just 0.2

percentage points, according to the Canadian Bankers’ Association (Chart 14).

Relative to the 3.4 percentage point increase in delinquencies recorded in the

US between 2008 and 2010, Alberta’s mortgagors appear to have weathered

the oil

downturn quite robustly. This particular shock was obviously concentrated in

one sector and had little knock-on eect on the broader financial system. However,

the miniscule

increase in mortgage delinquencies speaks to the stability of the

housing market. No doubt the impact on the housing market would be far larger

in the event of a

coordinated, nationwide recession triggered by trade, but to what

degree is an unknown.

Chart 14: US and Canadian 90+ Day

Mortgage Delinquency Rate

0%

1%

2%

3%

4%

5%

6%

2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018

US

Canada

% of outstanding loans

Source: US Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Canadian Bankers' Association

33The real story behind housing and household debt in Canada: Is a crisis really looming?

11. Concluding remarks

If there is one key takeaway from this discussion, it is that there are far

more intricacies in the housing market than meet the eye. Looking solely

at home prices and household debt levels overlooks both the complexity

of the mortgage finance system and the ingredients necessary for Canada’s

record debt levels to translate into a broader economic crisis.

From a financial stability perspective, the most important factor is that

credit quality is fundamentally strong and even getting better over time.

Without low credit quality mortgages permeating the financial system,

Canada remains relatively insulated from the kind of economic shock that

most fear when looking at high-level indicators.

There are several potential risks worthy of serious scrutiny, however.

The activities of less-regulated mortgage finance companies, mortgage

aggregators and other non-bank lenders and their growing role in the

broader mortgage finance system are certainly cause for concern. So, too,

is the vulnerability presented by the relatively high concentration of highly

leveraged borrowers.

However, the overall risk presented by housing does appear to be relatively

well-contained, begging the question that if these levels of home prices are

not being driven by unsustainable growth in bad credit to over-indebted

households, then what factors are driving home prices up so high? A possible

answer, though unpalatable, is that homes are fairly priced. That contrary to

Canada’s notion of fairness and equality, the laws of supply and demand have

simply pushed the fair market price of housing in major markets beyond what

many can aord. This could very well be what Canada is today: a country

of world-class cities that are no longer the bastions of equal opportunity for

homeownership they once were.

34 The real story behind housing and household debt in Canada: Is a crisis really looming?

12. Bibliography

1. A charya, Viral V. & Richardson, Matthew. 2009. “Restoring Financial Stability:

How to Repair a Failed System.” John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

2. Baily, Martin N., Litan, Robert E., & Johnson, Matthew S. November 2008.

“The Origins of the Financial Crisis.” Initiative on Business and Public Policy

at Brookings. Fixing Finance Series – Volume 3.

3. Bilyk, Olga, Ueberfeldt, Alexander, & Xu, Yang. November 2017. “Analysis of

Household Vulnerabilities Using Loan-Level Mortgage Data.” Bank of Canada

Financial System Review.

4. Calabria, Mark. March 2011. “Fannie, Freddie, and the Subprime Mortgage

Market.” Cato Institute Briefing Papers No 120.

5. C ateau, Gino, Roberts, Tom, & Zhou, Jie. December 2015. “Indebted

Households and Potential Vulnerabilities for the Canadian Financial System:

A Microdata Analysis.” Bank of Canada Financial System Review.

6. Coletti, Don, Gosselin, Marc-Andre, & MacDonald, Cameron. December 2016.

“The Rise of Mortgage Finance Companies: Benefits and Vulnerabilities.”

Bank of Canada Financial System Review.

7. Gorton, Gary B. September 2008. “The Panic of 2007.” NBER Working Paper

Series. Working Paper 14358.

8. G ravelle, Toni, Grieder, Timothy, & Lavoie, Stephane. June 2013. “Monitoring

and Assessing Risks in Canada’s Shadow Banking Sector.” Bank of Canada

Financial System Review.

9. Mordel, Adi, & Stephens, Nigel. December 2015. “Residential Mortgage

Securitization: A Review.” Bank of Canada Financial System Review.

277 WELLINGTON STREET WEST

TORONTO, ON CANADA M5V 3H2

T. 416 977.3222 F. 416 977.8585

CPACANADA.CA

CHARTERED

PROFEss,oNAL

AccouNTANTs

CANADA