SPECIAL

REPORT

• The marginal effective tax rate (METR) on corporate investment

(i.e., the tax impact on capital investment as a portion of the cost

of capital) is 35.3 percent in the U.S.—higher than in any other

developed country.

• The U.S. has maintained the highest METR in the OECD since

2007, when Canada’s multiyear program of corporate tax reform

brought its METR below the G-7 average.

• Nonetheless, the White House and Treasury Department

continue to assert that the U.S. has a lower METR than Canada

by failing to properly account for sales and property taxes.

• The U.S. METR varies by industry, from 26.7 percent for

transportation to 39.3 percent for communications.

• The U.S. average effective tax rate on corporations (AETR) is

irregular from year to year due to the complexity and instability

of the corporate tax code.

• Excessively high U.S. corporate tax rates have shrunk the U.S.

corporate sector and reduced corporate tax revenues.

Key Findings

The U.S. Corporate Effective

Tax Rate: Myth and the Fact

& Duanjie Chen

Feb. 2014

No. 214

By Jack Mintz

Director and Palmer Chair in School of Public Policy, University of Calgary

Research Fellow, School of Public Policy, University of Calgary

2

e statutory corporate income tax rate of the United States is infamously one

of the highest in the world, while effective tax rates on capital investments

appear to be high and dispersed.

For businesses, it is not unusual to see their effective tax rates, regardless of how

these are defined, being lower than their statutory tax rates. is results from

tax preferences (“loopholes,” if using a pejorative term) that are more generous

than the economic costs of generating taxable income.

For economists, it is also commonly understood that effective tax rates follow

the trend of statutory tax rates in the long run. e long-run divergence

between these two rates is not caused by the economic cycle but by irregular

provisions of various conditional tax preferences. ese irregular conditional tax

allowances or credits narrow the tax base, which often goes hand in hand with

rather high statutory tax rates.

e combination of a narrow tax base and an otherwise unnecessarily high tax

rate hurts business investment in general by benefiting only those investors who

can use available tax preferences. is creates an uneven playing field, resulting

in a misallocation of capital toward tax-favored activities as well as making the

tax system more complex to comply with and administer. e U.S. government,

moreover, puts itself at a disadvantage with high statutory corporate tax rates,

since businesses are encouraged to shift profits out of the U.S. with transfer

pricing and tax-efficient financing structures to low tax rate jurisdictions,

thereby reducing revenues that could be used to finance federal government

services.

is paper evaluates the U.S. corporate effective tax rate by two general

methods: one is the marginal effective tax rate (METR) on new investments

and the other is the average effective tax rate (AETR). We conclude that the

problem with the U.S. corporate income tax system is much broader than the

high federal-state combined statutory tax rate of over 39 percent. e corporate

tax system also undermines economic growth with a non-neutral treatment of

business activities.

The Corporate Marginal Effective Tax Rate

Marginal effective tax rate (METR) analysis has been a well-documented and

extensively applied analytical tool for measuring tax impacts on investment

and capital allocation distortions since the 1980s.

1

We have applied this

analysis systematically since 2005 for the purpose of ranking Canadian business

1 For the classic introduction to the METR concept and methodology, see R. Boadway, N. Bruce, & J. M. Mintz,

Taxation, Ination, and the Effective Marginal Tax Rate in Canada, 17 62-79

(1984). See also M. A. King & D. Fullerton,

3

tax competitiveness among the G-7, the OECD member countries, and an

expanding list of other countries.

2

Tax competitiveness is relevant due to the increased capital mobility across

borders associated with globalization. Taxes that impinge on investment reduce

the economy’s capacity to produce goods and services in the future, which can

be referred to as the “inter-temporal” distortion arising from capital taxation.

Taxes that vary by business activity also cause inter-sectoral, inter-asset,

financial, and organizational distortions that result in a less than optimal use

of capital resources in the economy. A more level playing field among business

activities shifts resources from investments earning low pre-tax rates of return

on capital to those earning higher pre-tax returns, thereby improving the

allocation of capital in the economy.

erefore, a country’s competitiveness is hurt by taxation that undermines

productivity through investment. ere is no doubt that the free-market system

of the U.S. has been a beacon for entrepreneurs and capital investors. But it

can do better with multinational companies if its corporate tax system can be

reformed to combine a lower tax rate with a broader tax base that facilitates

capital investment in general rather than benefiting only a few who are able to

navigate through a complex tax structure.

Marginal Effective Rate Calculation

e marginal effective tax rate measures the tax impact on capital investment

as a portion of the cost of capital. In considering a new investment, a firm will,

like any rational investor, allocate capital to maximize profit. e assumption

that firms are profit maximizers provides a starting point for calculating the

METR. Firms increase investment when marginal returns cover marginal costs

and reduce scale when marginal returns are less than marginal costs. Since it is

only the marginal cost of investment, rather than the marginal return, that is

directly observable, the METR uses marginal cost to calculate the measure. e

METR is evaluated as the effective tax cost as a share of marginal investment

costs net of economic depreciation and risk,

3

which is also the pre-tax rate of

return on capital. For example, if the pre-tax rate of return on capital (i.e., the

tax-inclusive cost of capital) is 20 percent at the profit-maximizing point and

the post-tax rate of return on capital (i.e., the tax-exclusive cost of capital) is 10

percent, the METR is 50 percent.

2 To update our cross-border tax comparison annually, we not only incorporate the legislated tax changes on an

and policy decisions. Applying these updated non-tax parameters to all the years contained in our latest model

see Duanjie Chen & Jack Mintz,

2013 Annual Global Tax Competitiveness Ranking: Corporate Tax Policy at a Crossroads

.

not be the case. For a discussion, see J. Mintz, The Corporation Tax: A Survey, 16 23-68 (1995).

4

U.S. among Least Competitive on Marginal Effective Tax

Rate

In our annual business tax competitiveness ranking,

4

which is based on our

calculation of marginal effective tax rates by country, the U.S. has been among

the least tax-competitive countries for capital investment over the past nine

years (see Table 1). e Canadian METR has been lower than that in the

U.S. since 2007 thanks to the steady reduction in corporate income tax rates,

elimination of the capital tax on non-financial corporations, and provincial sales

tax harmonization that eliminated sales taxes on purchase of capital goods, all

of which were a concerted effort made by both the federal and most provincial

governments under different political parties over the past decade.

The U.S. Model is Out of Line with other METR

Computations

Noting that our METR calculation has been in line with other METR

computations such as those by Finance Canada and the Oxford University

Center for Business Taxation,

5

it was a surprise to see that a recent METR

ranking presented by the White House and the U.S. Treasury (hereafter the

“U.S. model”) showed Canada having a higher METR (33 percent) than that

for the U.S. (29 percent) for 2011.

6

How can that be given Canada’s much lower statutory corporate income tax

rate (27.6 percent for 2011 and 26.1 percent for 2013) compared to that in the

State Business Tax Climate Index,

5 For the latest METR presentations by these two sources, see Finance Canada, Economic Action Plan 2012, Chapter

3.2 and Chart 3.2.1, . See also

CBT Corporate Tax Ranking 2012 (June 2012).

6 SeeThe President’s Framework for Business Tax Reform (Feb.

2012) at Table 1,

.

Table 1. Corporate Tax Rates (%) on Capital Investment, Various Country Groups, 2005-2013

Marginal Effective Tax Rate

Statutory Corporate Income Tax (CIT) Rate

2013 2012 2011 2010 2009 2008 2007 2006 2005

2013 2005 Change

in %

points

2005-13

# of countries

that have cut

the general

CIT rate

U.S. 35.3 35.3 35.3 35.3 35.6 35.6 35.6 35.9 35.9

39.13 39.3 -0.21 n/a

Canada 18.6 17.3 18.7 19.8 27.3 28.0 30.5 36.2 38.8

26.1 34.2 -7.9 n/a

G-7 27.6 27.9 28.6 28.9 30.1 30.2 32.9 33.7 34.2

31.1 35.7 -4.6 5

G-20 24.5 24.5 28.0 28.0 28.0 28.1 33.5 33.5 33.5

31.1 35.7 -4.6 12

OECD

(34)

19.6 19.5 19.7 19.6 19.8 20.1 21.0 21.6 22.4

25.5 28.2 -2.7 22

U.S. ranking by METR (highest to lowest) within various groups of countries

G-7 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 2

G-20 2 2 2 2 2 3 3 4

6

OECD 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2

2

5

U.S. (39.1 percent)?

7

e answer lies in the difference between our coverage of

taxes and that of the U.S. model.

In theory, all the taxes affecting corporate income and payable by corporations

should be included in calculating METR. ese taxes include direct taxes,

ranging from income taxes to asset-based taxes such as capital taxes and

property taxes, to indirect taxes on purchase of capital goods, such as asset

transaction taxes and sales taxes that are not based on value added. In practice,

however, some taxes are not consistently measurable across all the tax regimes

under study.

For example, for many of the OECD countries, including Canada and the U.S.,

the property tax is a sub-national tax that varies widely across localities and

uses of property (e.g., commercial or industrial) in both the tax base and rate.

It is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to come up with a national average

property tax rate that is applicable to each industry in a consistent manner.

Further, since many municipal property taxes are charges for services provided

to residents and businesses such as water, sewage, and roads, one would

typically need to net out related benefits from taxes for measurement purposes.

For these reasons, we exclude property taxes in our model to ensure that all tax

regimes are treated consistently.

The U.S. Model Inaccurately Depicts U.S. Property Tax Rate

Parameters

In contrast, the U.S. model casually, and inconsistently, includes such a

parameter across borders. For Canada, the U.S. model applied Toronto’s 4

percent property tax rate for industrial buildings in 2009 as the Canadian

“effective real estate tax rate” while using a 1 percent “net wealth tax rate” as the

U.S. counterpart.

8

is simplified assumption overstates Canadian property tax

rates while understating property taxes in the U.S. In fact, Toronto has one of

the highest property tax rates in Canada and its current comparable rate is only

3 percent

9

while the average urban commercial and industrial property taxes

in the U.S. is close to 2 percent. Note also that, unlike in Canada, business

property taxes in the U.S. are also applicable to machinery and equipment

and in some states to inventory.

10

is means that if the same national average

property tax rate was 2 percent—or any rate—in both countries, the METR

Corporate and Capital Income Taxes

Worldwide Corporate Tax Guide

Effective Tax Levels Using the Devereux/Grifth Methodology,

.

9 SeeProperty Tax, .

10 See50-State Property Tax Comparison

Study (Apr. 2011),

.

6

impact associated only with such a property tax would be much higher in the

U.S. than in Canada because of the broader property tax base in the U.S.

Furthermore, while Canadian provincial governments have completely

eliminated the capital tax on non-financial corporations, with the last two

provinces (Nova Scotia and Quebec) doing so by 2012, some states in the U.S.

still levy a tax based on corporations’ asset values.

11

In our model, this asset-

based tax is zero for Canada but close to 0.05 percent for the U.S., which added

about a half percentage point to the U.S. METR.

The U.S. Model Excludes Effective Sales Tax Rates on

Capital Goods

Finally, our model includes the effective sales tax rates on capital goods based

on national statistics while the U.S. model does not. Sales taxes in most

Canadian provinces for 2011 were harmonized with the federal Goods and

Services Tax (GST) (only British Columbia, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba

continue to have retail sales taxes today). e federal GST is a value-added tax

that generally refunds the sales tax on capital goods thereby having little impact

on capital investment. On the other hand, the majority of the state sales taxes

in the U.S. constitute a direct cost on capital goods. erefore, including the

effective sales tax rate in METR calculations reflects more closely the reality that

sales taxes not based on value added impose a tax burden on capital investment.

e impact of sales taxes on METR of capital investment is an important

reason why the U.S. ranks as the most tax unfriendly regime towards capital

investment among OECD member countries (see Table 2).

Dispelling the Myth: Excluding Effective Sales Taxes and

Inaccurately Depicting Property Tax Rates Gives the U.S.

an Artificially Low Marginal Effective Tax Rate

at is, the U.S. model, by excluding the effective sales tax rate on capital

goods, which is included in our METR model, and by including an artificially

high property tax rate for Canada and an artificially low counterpart for the

U.S., produced a much lower METR for the U.S. than for Canada. is result

naturally surprised many analysts because the aggregated statutory corporate

income tax rate of Canada is only two-thirds that of the U.S. To resolve this

myth, Figure 1 below reconciles our METR calculation with that produced by

the U.S. model.

e U.S. model excludes the U.S.’s subnational capital taxes and U.S. sales

taxes, which are sub-optimally designed for business investment when

7

Table 2. Marginal Effective Tax Rate on Capital Investment, OECD Countries, 2005 – 2013

Marginal Effective Tax Rate

Reference: Statutory

Company Income Tax

Rate*

2013 2012 2011 2010 2009 2008 2007 2006 2005

2013 2005 Change

in %

points

U.S. 35.3 35.3 35.3 35.3 35.6 35.6 35.6 35.9 35.9

39.1 39.3 -0.1

France 35.2 35.2 35.2 34.0 35.1 35.1 35.1 35.1 35.4

34.4 35.0 -0.5

Korea 30.1 30.1 30.1 30.1 30.1 32.8 32.8 32.8 32.8

24.2 27.5 -3.3

Japan 29.3 31.5 31.5 31.5 31.5 31.5 31.5 31.5 31.5

37.0 39.5 -2.6

Austria 26.2 26.2 26.2 26.2 26.2 26.2 26.2 26.2 26.2

25.0 25.0 0.0

Spain 26.0 26.0 26.0 26.0 26.0 26.0 28.2 30.3 30.3

30.0 35.0 -5.0

Australia 25.9 25.9 25.9 25.9 25.9 25.9 25.9 25.9 25.9

30.0 30.0 0.0

UK 25.9 26.9 27.1 29.1 29.0 28.8 30.0 30.0 30.0

23.0 30.0 -7.0

Italy 24.5 24.5 28.0 28.0 28.0 28.1 33.5 33.5 33.5

27.5 33.0 -5.5

Germany 24.4 24.4 24.4 24.4 24.4 24.4 34.0 34.0 34.0

30.2 38.9 -8.7

Norway 24.4 24.4 24.4 24.4 24.4 24.4 24.4 24.4 24.4

28.0 28.0 0.0

Portugal 22.9 22.9 20.8 20.8 18.8 18.8 18.8 19.6 19.6

31.5 27.5 4.0

New Zealand 21.6 21.6 21.6 18.2 18.2 18.2 20.5 20.5 20.5

28.0 33.0 -5.0

Denmark 19.1 19.1 19.1 19.1 19.1 19.1 19.1 21.7 21.7

25.0 28.0 -3.0

Canada 18.6 17.4 18.7 19.8 27.3 28.0 30.9 36.2 38.8

26.3 34.2 -7.9

Belgium 18.5 18.5 18.5 18.5 18.5 18.5 18.0 18.0 23.5

34.0 34.0 0.0

Greece 18.1 11.3 11.3 13.2 13.7 13.7 13.7 15.8 17.5

26.0 32.0 -6.0

Finland 17.5 17.5 18.7 18.7 18.7 18.7 18.7 18.7 18.7

24.5 26.0 -1.5

Switzerland 17.5 17.5 17.5 17.5 17.5 17.5 18.0 18.0 18.0

21.1 21.3 -0.2

Netherlands 17.5 17.5 17.5 17.5 17.5 17.5 17.5 20.7 22.3

25.0 31.5 -6.5

Mexico 17.4 17.4 17.4 17.4 16.0 16.0 16.0 16.7 17.4

30.0 30.0 0.0

Luxembourg 17.3 17.0 17.0 16.8 16.8 18.5 19.4 19.4 19.9

29.2 30.4 -1.2

Estonia 17.1 17.1 17.1 17.1 17.1 17.1 18.1 19.1 20.2

21.0 24.0 -3.0

Hungary 16.1 16.1 16.1 16.1 16.6 16.6 16.6 15.3 14.7

19.0 16.0 3.0

Sweden 16.1 19.5 19.5 19.5 19.5 20.9 20.9 20.9 20.9

22.0 28.0 -6.0

Slovak Rep. 15.7 12.7 12.7 12.7 12.7 12.7 12.7 12.7 12.7

23.0 19.0 4.0

Israel 15.0 15.0 14.3 15.0 15.8 16.5 18.0 19.5 19.5

25.0 34.0 -9.0

Poland 14.6 14.6 14.6 14.6 14.6 14.6 14.6 14.6 14.6

19.0 19.0 0.0

Iceland 14.2 14.2 14.2 12.6 10.4 10.4 12.6 12.6 18.0

20.0 18.0 2.0

Czech Rep 12.7 12.7 12.7 12.7 13.5 14.2 16.5 16.5 18.0

19.0 26.0 -7.0

Ireland 10.1 10.1 10.1 10.1 10.1 10.1 10.1 10.1 10.1

12.5 12.5 0.0

Slovenia 9.8 10.5 11.8 11.8 12.4 13.1 13.8 14.5 15.2

17.0 25.0 -8.0

Chile 7.7 7.7 7.7 6.7 6.7 6.9 7.1 7.3 7.3

20.0 17.0 3.0

Turkey 5.7 5.7 5.7 5.7 5.7 5.7 5.7 5.7 10.9

20.0 30.0 -10.0

OECD Average:

Weighted* 28.5 28.8 29.0 29.1 29.5 29.6 30.8 31.2 31.5 32.9 35.5 -2.6

Unweighted 19.6 19.5 19.7 19.6 19.8 20.1 21.0 21.6 22.4

25.5 28.2 -2.7

Note: G-7 countries are in bold.

* Weighted by the average GDP for 2005-2011 in 2005 constant U.S. dollars.

8

and a tax on either tangible property that is not subject to local taxation or net worth (0.26 percent). Other

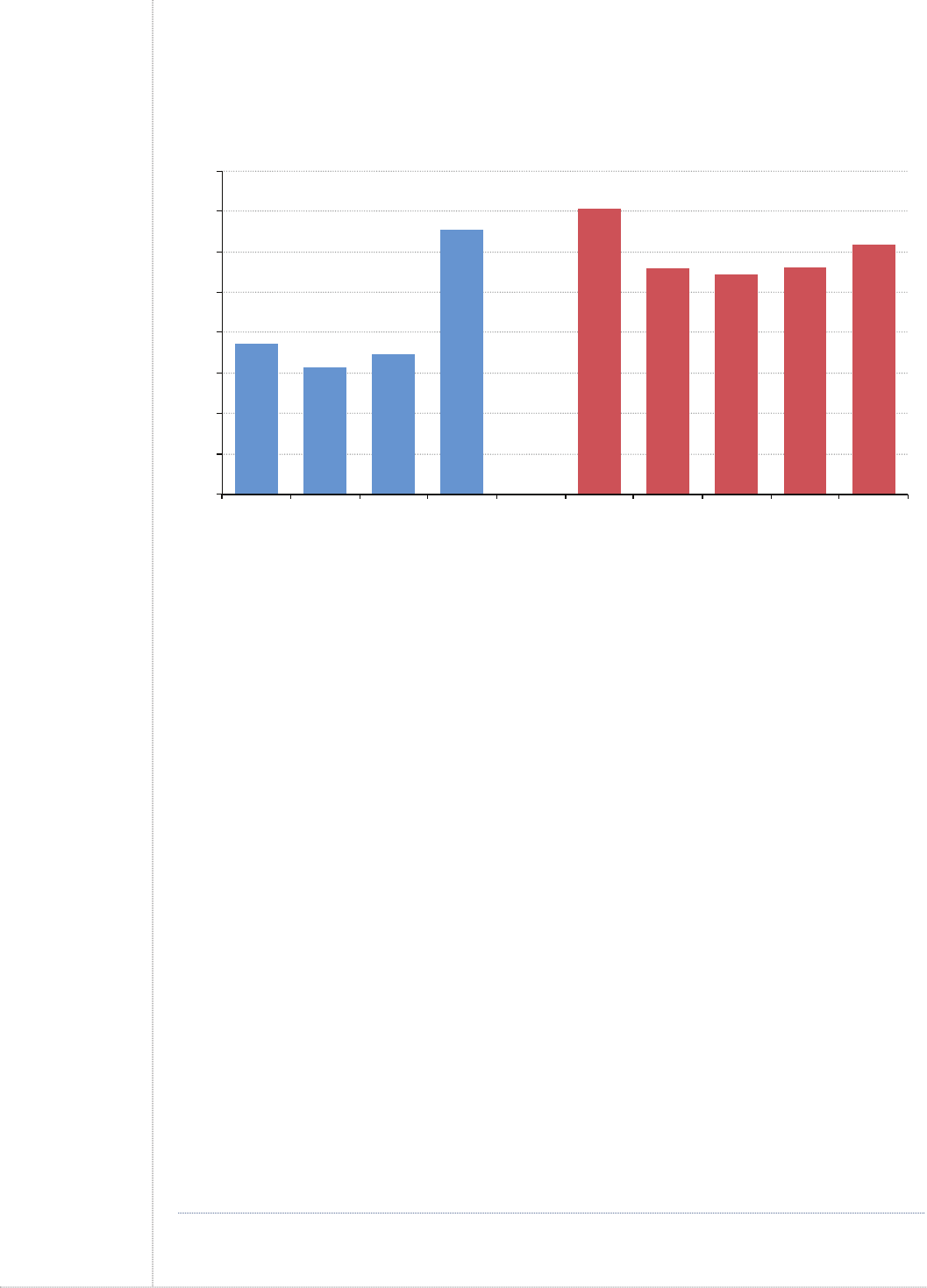

compared to the predominately VAT-based sales taxes in Canada. As Figure 1

shows, starting from our METR calculation for 2013 that includes effective

subnational capital taxes (0.05 percent in the U.S. and zero in Canada) and

effective sales taxes that are not on a valued-added base (2.3 percent in the U.S.

and 0.6 in Canada), the Canadian METR is 18.6 percent and the U.S. 35.3

percent. By excluding the effective subnational sales taxes and capital taxes, the

METR dropped to 15.7 and 27.2 percent for Canada and the U.S. respectively.

is METR gap of 11.5 percentage points is very close to the gap (13

percentage points) in statutory corporate tax rates between the two countries

(26.1 percent in Canada versus 39.1 percent in the U.S.).

is gap may shrink to 10.7 percentage points if we further exclude the non-

temporary investment tax credits (ITC), which in aggregate are more generous

in Canada than in the U.S., making the METR 17.4 percent for Canada

and 28.1 percent for the U.S. e remaining difference between this 10.7

percentage point METR gap and the 13 percentage point gap in statutory

corporate tax rates is due to Canada’s depreciation regime that more accurately

reflects true cost of investment.

12

18.6

15.7

17.4

32.7

35.3

27.9

27.2

28.1

31.2

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

2013* Excl.

provincial

sales tax

CIT only/

excl. ITC

Incl. a 4%

real estate

tax**

2011-2013* Excl. state

sales tax

Excl. state

capital tax

CIT only/

excl. ITC

Incl. a 1%

net-wealth

tax**

Figure 1. Marginal Effective Tax and Royalty Rate (in percent)

2013 Canada vs. USA

The US Canada

*Authors’ original calculation.

**Parameters that are used by the White House and U.S. Treasury but do not reflect national realities

consistently.

9

From this baseline, if we add the 4 percent real estate tax and the 1 percent

net wealth tax to our METR model for Canada and the U.S. respectively and

apply them only to real estate (i.e., buildings and land), we arrive at METRs of

32.7 percent for Canada and 31.2 percent for the U.S., which are close to those

presented by the White House and the U.S. Treasury for their 2011 METR

ranking.

Note that, like any asset-based taxes, the real estate tax has a much higher

METR impact compared to the income tax when it is a significant share of

pretax rates of return. For example, if the pre-tax return on structures and

land, net of risk, is 6 percent, a 4 percent real estate tax is equivalent to a

66.7 percent effective tax rate. Given the significant share of structures of

total investment, this explains why the 4 percent real estate tax rate raised the

Canadian METR by over 15 percentage points while the 1 percent real estate

tax raised the U.S. METR by 3 percentage points.

We have thus solved the myth in METR ranking for Canada versus U.S.

produced by the official U.S. model.

13

at is, the myth was a combined result

of excluding the retail sales taxes on capital inputs and a rushed application of

inconsistent assumptions of “national” property tax rates.

Dispersion in Marginal Effective Tax Rates in the United

States

e U.S. corporate tax system is not only uncompetitive with high statutory

and effective rates but it is also non-neutral with effective rates varying by asset

and industry. With unequal tax burdens on business activities, the tax system

distorts the allocation of capital in the U.S. economy with some businesses

bearing more tax than others on capital investment. A more level playing field

would result in capital flowing from preferentially treated business activities

with low marginal returns to those earning higher marginal returns to cover tax

costs.

Differing Tax Treatment across Industries Creates

Economic Distortions

Table 3 provides a breakdown of our estimated marginal effective tax rate by

major asset and industry for the U.S. economy. e U.S. corporate tax system

imposes a heavier tax burden on most services compared to forestry, utilities,

and transportation and storage. is inter-industry dispersion is in part due to

the preferential corporate income tax rate applied to manufacturing and other

profits. Given the importance of the services sector in terms of its share of the

13 A technically more serious reconciliation requires checking through the non-tax data applied to the METR

10

economy’s production and job creation, this anomaly is significant, because it

potentially impedes economic growth.

Even though we leave out property taxes on real estate, it is clear that structures

are most heavily taxed followed by machinery and equipment investments.

In large part, the dispersion in effective tax rates results from U.S. state

retail sales taxes falling heavily on machinery and structure purchases. Inter-

asset dispersion also arises from some limited tax preferences for targeted

investments. Tax depreciation rates vary from economic depreciation rates

in some cases although they are not a major source of dispersion (not shown

in Table 3). Inventory costs are partly based on last-in-first-out accounting

methods that tend to protect the impact of inflation on costs, unlike for other

assets except for land. e variation in METRs on assets discourages businesses

from adopting techniques that require more heavily taxed inputs. It also

discourages the growth of those industries that are more intensive users of these

heavily taxed assets.

Finally, we should note that a significant reduction in statutory corporate

income tax rates across all industries would reduce the dispersion in effective tax

rates.

The Corporate Average Effective Tax Rate

e conventional concept of the corporate average effective tax rate (AETR) is

the tax paid (or payable) divided by the relevant tax base. For a given amount of

tax paid or payable, the associated AETR can vary widely because the tax base

defined as the denominator can vary widely.

14

In this brief paper, we do not

intend to specify such a tax base and the associated corporate AETR; instead,

we draw our observations on the corporate AETR based on macro corporate

financial statistics published by the appropriate government agencies.

Table 3. Marginal Effective Tax Rates By Industry and Asset for 2013 in the United States

Forest Public

Utilities

Construction Manufacturing Wholesale

Trade

Retail

Trade

Transportation Communication Other

Services

Aggregate

Buildings 47.5 25.9 37.7 47.7 43.0 43.7 17.2 37.1 42.7 40.4

M&E 22.3 53.1 41.2 26.4 47.3 45.0 32.0 40.2 47.6 35.9

Land 16.7 18.6 16.6 16.8 18.5 18.5 18.4 18.4 18.3 18.0

Inventory 27.1 29.7 27.0 27.2 29.6 29.5 29.5 29.5 29.3 28.3

Aggregate 30.4 29.8 35.6 33.5 37.8 37.0 26.7 39.3 41.9 35.3

14 See, e.gEconomic Analysis: Behind the GAO’s 12.6 Percent Effective Corporate Rate,

11

Figure 2. The U.S. Corporate Income Tax: Rate vs. Revenue (as % of GDP)

Based on Bureau of Economic Analysis, Tables 1.14 and 7.16

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010

Taxable income as % of GDP

CIT as % of GDP

Profit as % of GDP

Statutory CIT rate

Average Effective CIT rate*

*Estimated as the ratio of “taxes on corporate income” net of “payments by the federal reserve banks” to “corporate

profits” net of “income organizations (including federal reserve banks) not filing corporate tax returns.”

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010

CIT revenue as % of GDP

Taxable income as % of GDP

Average Effective CIT rate*

Net profit as % of GDP

Statutory CIT rate

* Obtained from Cansim Database, v21584924-Income taxes to taxable income; Total all industries.

Figure 3. Canadian Corporate Income Tax: Rate vs. Revenue (as % of GDP)

Based on Statistics Canada, Financial and Taxation Statistics for Enterprises

12

Figure 2 provides statutory corporate income tax rates along with an effective

corporate income tax rate and corporate profits, taxable income and corporate

income tax revenue as a share of GDP.

15

As a comparison, Figure 3 provides

Canadian counterparts of the U.S. indicators shown in Figure 2.

Note that while the Canadian effective corporate income tax rate is an official

estimate published by Statistics Canada, the U.S. effective corporate income

tax rate is our estimate of the ratio of “taxes on corporate income” (net of the

payment made by the Federal Reserve banks) to “corporate profits without

inventory adjustment,” which is net of income of organizations, including

Federal Reserve banks, that do not file corporate income tax returns. It is

important to remember that this simplified calculation of AETR underestimates

the effective corporate income tax rate in the U.S. since the tax base (i.e.,

corporate profits without inventory adjustment) used in our calculation is a

mixture of profits made by both C and S corporations, which are not subject to

corporate income taxes.

16

e three following observations can be drawn from a comparison between

the U.S. (Figure 2) and Canada (Figure 3) with respect to their corporate

income tax structures, as indicated by the relationship between the effective and

statutory corporate income tax rates and other tax indicators.

High Corporate Tax Rates Do Not Necessarily Bring in

High Corporate Tax Revenues

First, if revenue collection is the main purpose of taxation, then an excessively

high corporate income tax rate does not necessarily bring in high corporate

tax revenue; an excessively high tax rate can even be accompanied by large

fluctuations in tax revenue. For example, despite the fact that the statutory

corporate income tax rate barely changed over the past ten years (from 39.3

to 39.1 percent) in the U.S., the corresponding corporate income tax revenue

as a share of GDP fluctuated significantly between 1.8 percent (2002) and 3.4

percent (2006).

In contrast, the Canadian statutory corporate income tax rate has dropped from

42.4 percent (2000) to 29.4 percent (2010), and the corresponding tax revenue

as a share of GDP was rather stable, swinging only between 3.1 percent (2002)

and 3.8 percent (2006). It is also interesting to note that the low and high years

(2000 and 2006) for corporate tax collection are the same in both countries,

which indicates that, aside from the tax structure, the economic cycle, and thus

the profit cycle, is the main determinant of corporate tax revenue.

BEA data.

13

Low Rates and Broad Bases Lead the Statutory and

Effective Tax Rates to Converge

Second, a tax structure featuring a low rate and a broad base can lead to

convergence between the statutory and the effective tax rates and vice versa.

For example, as its statutory corporate income tax rate has dropped steadily,

the Canadian average effective corporate income tax rate appears to converge

with its statutory tax rate over time, partly reflecting base changes and the using

up of the carry forward of past losses. In contrast, the U.S. effective corporate

income tax rate, regardless of how it is defined, does not show any correlation

with its statutory corporate tax rate.

Note that the statutory corporate income tax rate shown in Figures 2 and 3 is

the top corporate tax rate, and both Canada and the U.S. provide reduced tax

rates for small corporations. erefore, it is reasonable to see an overall effective

corporate income tax rate as being below the top statutory corporate income tax

rate. However, when the effective tax rate does not follow the pattern of the top

statutory tax rate but diverges from it considerably, it indicates a swing related

to irregular policy changes (e.g., temporary, discretionary, or both types of

income tax credits on a large scale), new tax planning that succeeds in reducing

tax liabilities on a given taxable income, or both.

Excessively High U.S. Corporate Tax Rates Have Led to a

Smaller U.S. Corporate Sector

Finally, the excessively high corporate income tax rate in the U.S. appears

to have led to a smaller corporate sector in relation to the overall economy.

Canadian corporate net profit has been well above 10 percent of GDP since

2003 when the corporate tax rate dropped to below 36 percent, and Canadian

corporate taxable income also moved steadily to above 10 percent of GDP

even during the recent period of financial crisis. is possibly reflects a reduced

incentive to shift profits out of Canada. It could also reflect more use of the

corporate form by small businesses, because Canada avoids double taxation of

corporate income passed on to shareholders with its dividend tax credit and

partial exclusion of capital gains from taxation (in other words, an integrated

corporate and personal income tax system).

In contrast, there were only three years during period of 2000 to 2010 when

corporate net profits in the U.S. reached above 10 percent of GDP and there

was only one year (2006) when U.S. corporate taxable income reached 10

14

published at least 6

times yearly by the

Tax Foundation, an

independent 501(c)(3)

organization chartered

Columbia.

The Tax Foundation

is a 501(c)(3) non-

research institution

educate the public on

tax policy. Based in

economic and policy

analysis is guided

simplicity, neutrality,

transparency, and

stability.

©2014 Tax Foundation

Editor, Donnie Johnson

Tax Foundation

20045-1000

202.464.6200

percent of GDP. It is no wonder that U.S. corporate tax revenue as a share

of GDP has been below that of Canada. It seems reasonable to suggest that

the high statutory corporate income tax rate encouraged corporations to shift

profits to other jurisdictions, including Canada. It also reflects the actions of

discouraged U.S. entrepreneurs from incorporating their business activities by

choosing instead limited liability partnerships and other organizational forms

that avoid double taxation at the corporate and personal levels; such actions

have been dubbed “distorporation” in a recent issue of e Economist.

17

Conclusion

Unlike in Canada where income earned and taxes paid by corporations appear

to correlate with each other along with explainable economic interruptions,

U.S. business taxation is distorting. e excessively high corporate income

tax rate has become a cause of tax inefficiency and ineffectiveness by

leading businesses to excessive tax planning and tax-induced avoidance of

incorporation. We are aware that both the government and the business sector

in the U.S. are interested in reforming their corporate tax system. We want to

point out, however, that the messy picture of U.S. effective corporate tax rates

only reflects the inefficiency and complexity of the U.S. corporate tax system; it

should not be used as an excuse for delaying its reform.

17 The New American Capitalism: Rise of the Distorporation, , Oct. 26, 2013,

.