www.policyschool.ca

PUBLICATIONS

PUBLICATIONS

SPP Research Paper

SPP Research Paper

Volume 15:7 February 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.11575/sppp.v15i1.73545

A PROPOSAL FOR A “BIG BANG”

CORPORATE TAX REFORM

Jack Mintz

†

SUMMARY

To put it in simple terms, Canada’s corporate income tax is a mess. It discourages

capital investment most heavily in many service sectors, is highly distortionary

and overwhelmingly complex, impeding economic growth. With current inflation

rates, these distortions are even larger. With so many tax preferences, the

combined federal-provincial corporate income tax with a headline tax rate of 26

percent raises revenue little more than 19 percent of corporate profits.

To build up productive capacity in a post-COVID world, a big-bang approach

is needed to put Canada into a better position to attract investment and

reduce distortions in the business tax system. There are some major revenue-

neutral reforms that could improve neutrality and simplify the overly complex

corporate tax. Here, we particularly explore a corporate tax on distributed

profits without a reduction in corporate tax revenues.

A distributed profits approach means profits from investment activities would

only be taxed when they are distributed to investors. This allows profits

reinvested in capital to be exempt from taxation. A good example of this design

is Estonia’s corporate profit tax on distributions, introduced in 2000. This

reform resulted in the elimination of the corporate tax on reinvested profits —

these profits are only taxed when the profits are distributed. In 1999, prior to

the reform, corporate taxes, as a share of taxes, made up 0.9 per cent of GDP.

In 2019, they made up 1.7 per cent of GDP. Estonia has also had remarkable

investment performance since with fixed capital formation equal to 27 percent

of GDP compared to 23 percent in Canada since 2015.

†

I wish to thank the editor, Ken McKenzie, Jerey Trossman and two anonymous reviews for detailed comments that significantly

improved the paper. Special thanks to Phil Bazel who helped with underlying research.

1

Taxes generally distort economic activity — production of the taxed good or service

is reduced when eective tax rates are increased. The value of the lost production is

greater than the value of the tax added to government revenue. This results in several

distortions: intertemporal, inter-industry, inter-asset, international, risk-taking, financing

and business organization. The corporate tax on distributed profits, while still having

some disadvantages, does have several advantages in reducing these distortions.

The proposal considered here would tax deemed distributions of profits including share

buybacks and certain deemed payments to prevent erosion of the tax base. Passive

income and capital gains earned by the corporation would remain taxed similar to

existing rules. The revenue-neutral corporate tax on distributed profits would be an

estimated 16 per cent at the federal level and 11.2 per cent on a provincial average tax

rate, when brought forward to the 2022/23 fiscal year results in the same corporate

tax revenues collected as in 2022 ($37 billion). While it seems that a distributed tax

that exempts reinvested profits would lower the corporate taxable income, it actually

doesn’t lower it much. Due to tax incentives, taxable corporate income ($370 billion for

2022/23) is significantly below corporate operating profits ($515 billion). The distributed

tax removes the need for tax incentives, no longer providing those tax savings.

This proposed model is not perfect, but it is better than the current system, which is

distortionary, with high economic, compliance and administrative costs. A distributed

profits design would make the corporate income tax fairer and simpler, reducing

administrative and compliance costs, while not significantly eroding corporate tax

revenues.

2

In the 2020 Tax Competitiveness report (Bazel and Mintz 2021), we concluded that

Canada’s corporate tax system is attractive to encourage investment in marginal

projects, although it has become much more distortionary and non-neutral due to

incentives, thereby undermining the productive use of resources. It has a relatively high

corporate income tax rate compared to most advanced countries, making Canada less

attractive for lumpy greenfield projects with high economic rents from intangible or

resource investments.

In this paper, I look at possible major revenue-neutral reforms to the corporate income

tax with the aim to improve neutrality and simplify the system. Canada could further

pursue its corporate tax reforms by lowering tax rates and broadening tax bases to

reflect economic income. However, this approach to reform, which has been the focus

for Canada since 1985, seems to have reached its limit in reducing corporate income

tax rates due to political opposition to corporate tax reduction, which is not unusual.

1

Instead, a fundamental tax reform could help tilt the playing field towards Canada to

boost investment, reduce tax distortions and simplify administration and compliance,

without a loss in revenue. I call this a big-bang reform. The basic proposal is to convert

the corporate tax into a tax on distributed profits that would improve static and

dynamic eciency in the corporate tax system.

2

It is not a perfect system, but it could

be a practical approach to boost growth and make the corporate tax more ecient

and fairer.

There are some important advantages to the approach, particularly reducing tax

distortions that discourage investment, especially for the service sectors in the

economy. The proposed structure would also be compatible with international tax

systems, even under the proposed global corporate minimum tax, and continue

support for small businesses. It does have one disadvantage — it would potentially be

distortionary in financing decisions by favouring retained earnings over other funding

sources. Recommendations will be made to the taxation of share buybacks, corporate

passive income and capital gains that would create potentially greater neutrality among

financing sources compared to the existing system.

The paper begins with a discussion of the problems with the corporate income tax

in Canada. This will be followed by a description of the proposed corporate tax on

distributed profits, including a review of both the positive and negative aspects of

the proposal. A rent-based approach to the taxation of corporate distributions is

considered, which would be consistent with a personal tax reform along the lines of

the expenditure tax approach.

1

In 1997, I had access to unpublished poll results showing that Canadians then believed that corporations

do not pay enough taxes as they do today. Similarly, Gallup reports that roughly 70 per cent of Americans

believe corporations pay too little tax. The Gallup opinion poll is quite stable no matter the state of the

economy between the years 2004 and 2019. About 63 per cent believe high-income taxpayers do not pay

enough in 2019, similar to 2004. About 43 per cent believe the middle class pays too much in 2019, which is

about the same as 2004. See https://news.gallup.com/poll/1714/taxes.aspx.

2

Our proposal could also be adjusted to tax only corporate rents by redefining the tax base as distributed

profits net of the new equity financing (although this would require a substantially higher corporate income

tax rate to make up for the loss of revenues). This approach would be appropriate if the personal income tax

is also reformed to remove the tax on savings. We will discuss this further below.

3

WHY IS THERE A CORPORATE TAX AND WHY IS IT FAILING IN

ACHIEVING ITS PURPOSE?

The corporate income tax plays an important role in financing federal and provincial

government public services. It raises close to $100 billion, almost 10 per cent of

consolidated general government revenues (Statistics Canada 2021). Despite its

importance, questions have been raised as to whether it should be abolished.

3

It has

been criticized as being the economically costliest tax, hurting growth and productivity

the most (Dahlby and Ferede 2018). It has also attracted criticism for being unfair by

being passed on by corporations as higher prices charged to consumers (Baker et al.

2020) or by reducing employment and wages paid to workers (McKenzie and Ferede

2018). To the extent that the corporate tax falls on returns to shareholders, its incidence

still falls not just on high-income investors, but also many middle and low-income

households, including worker pension plans.

Why do we have a corporate income tax? The principle for corporate tax design

in Canada, and most countries in the world, is based on the notion of taxing

comprehensive income for both personal and corporate income tax purposes.

Comprehensive income includes annual income from labour and capital net of

expenses to earn income. It includes employment compensation, business income,

property or investment income (dividends, interest and rents) and capital gains. In

principle, comprehensive income is adjusted for inflation and measured net of any

losses in business and capital income (if the tax base is negative, a refund should be

paid equal to the tax rate multiplied by the loss).

In principle, the corporate tax is not needed if profits are attributed to shareholders

for personal income and withholding tax purposes, similar to partnership income.

This is administratively complex with tiers of corporate ownership, as well as requiring

investors to pay tax on income that has not yet been distributed.

4

Alternatively, a

government could tax accrued capital gains from the change in the market value

of assets each year rather than realized capital gains upon the disposal of assets.

However, this forces owners to sell assets if they have insucient liquidity, as well

as being dicult to administer in the case of non-traded assets with no observable

market value. Further, non-resident shareowners would be out of reach for capital gains

taxation since they are only taxed by their resident governments.

As pointed out by the Carter Report (Government of Canada 1966), the corporate

tax may have two purposes. First, the corporate tax is a backstop to the personal tax

by operating as a withholding tax — the profit tax would be refunded once income

3

For example, L. Kotliko, “Abolish the Corporate Income Tax,” New York Times, January 5, 2014. See also E.

Dolan, “The Progressive Case for Abolishing the Corporate Income Tax,” 2017, https://www.milkenreview.org/

articles/the-progressive-case-for-abolishing-the-corporate-income-tax-2.

4

As noted by a Congressional Research Report in the United States: “One integration approach would be

to eliminate the corporate tax and allocate earnings directly to shareholders in a manner similar to which

partnerships … allocate income to their partners and shareholders” (Keightley and Sherlock 2014).

4

is distributed to investors.

5

Second, the corporate income tax withholds profits from

foreign investors who might also credit Canadian tax against their foreign tax liabilities,

resulting in a transfer of revenue from foreign to Canadian treasuries without a loss

of investment. The Technical Committee on Business Taxation (1997) further argued

that the corporate tax is a surrogate “benefit” tax when governments provide public

services such as infrastructure and limited liability laws that enhance the profitability of

corporations in the absence of user fees to recover the cost of public provision.

In recent years, the tension between the domestic and international roles for the

company tax has played a significant role in corporate tax policy developments. With

greater global capital mobility since 1990 and the erosion of corporate tax crediting,

6

countries have reduced corporate income tax rates and broadened corporate tax

bases to attract investment, improve tax eciency and keep profits in their jurisdiction.

For international competitive reasons, Canada has lowered its combined federal

and corporate income tax rate from 43 per cent in 2000 to 26 per cent by 2012

while curbing, to some degree, accelerated depreciation, investment tax credits and

other tax preferences.

7

This brought Canada’s corporate income tax rate in line with

other countries, rather than being the highest among OECD countries in 2000. The

consequence, however, was that the corporate tax rate fell below the top personal rate,

reducing the withholding role of the corporate income tax.

8

As Finance Canada has

observed, a portion of the personal income tax base shifted to the corporate sector

to reduce personal tax payments that would be subject to much higher tax rates

(Government of Canada 2015). Currently, the average top federal-provincial personal

income tax rate is roughly 52 per cent.

9

While these arguments for corporate taxation are well known, they are a basis

for suggesting a few principles for corporate tax design. Insofar as corporate tax

discourages economic activity, it should be designed to discourage as little economic

activity as possible, and so impose the lowest possible cost on the economy. Only in

5

The withholding role could imply that the corporate tax should be applied to economic rents, especially

if consistent with the personal tax (Institute of Fiscal Studies (Meade Report) 1978; Mirrlees Report 2011).

Some argue for the corporate tax to be applied to economic rents even if personal income continues to be

taxed at the personal level (Boadway and Tremblay 2014; McKenzie and Smart 2019). We will return to these

arguments below.

6

The crediting argument lost some appeal as countries moved away from taxing dividends paid by foreign

aliates to their parents. Crediting still applies to branch income, passive income, non-treaty income and,

under U.S. law, global intangible low-income tax (GILTI) income. Further, recent global discussions that would

result in countries agreeing to impose a minimum corporate income tax at the rate of 15 per cent would

reinstate the importance of the crediting argument.

7

After 2012, Canada corporate income tax changed modestly until 2018 when it introduced temporary

accelerated depreciation in response to U.S. tax reform (that reduced the U.S. corporate rate somewhat

below Canada’s (Bazel and Mintz 2019).

8

Top corporate and personal income tax rates were roughly aligned in the previous decade. In 1999, the top

personal income tax and corporate income tax rates were almost equal (46 and 45 per cent respectively).

Back in 1987, the top personal income tax rate was 51 per cent and the top corporate income tax rate was

about 52 per cent.

9

Tax preferences also result in corporate tax payments as a share of profits dropping below the statutory rate.

Further, small Canadian-controlled private corporations are taxed at preferential rates at about a combined

federal-provincial rate of 12.5 per cent (Mintz, Smith and Venkatachalam 2021).

5

the presence of a market failure would deviations from neutrality be desirable, such

as taxing pollution or subsidizing research, given the inability for innovators to fully

appropriate returns. However, even in the case of market failures, it is still necessary

to demonstrate that a tax policy is better to correct for market failures compared to

other interventionist tools, such as subsidies or regulations. For example, research

can be supported by grants instead of tax credits and pollution can be corrected by

regulations instead of taxes. Evaluating the benefits and costs of specific tax deviations

from neutrality compared to other forms of public intervention goes beyond the focus

of this paper. However, one can achieve corporate tax neutrality and correct market

failures with more suitable public policies.

AN EVALUATION OF THE EXISTING CORPORATE INCOME TAX

It is one thing to design a perfect corporate income tax, but it is another to achieve

perfection given other political and institutional considerations. Nonetheless, it is

worthwhile to evaluate the existing corporate income tax in terms of its impact on

tax policy considerations with respect to economic eciency, equity and cost of

compliance and administration (Mintz 2018). These tax structure considerations are

important to consider in setting tax policy.

ECONOMIC EFFICIENCY

Taxes generally distort economic activity. They reduce the production of the taxed

good or service, including capital and labour services, with the quantum of reduction

determined by the elasticity of supply and demand for such goods or services.

The value of this lost production will be greater than the value of the tax added to

government revenue. These eciency considerations are broken down into several

types of distortions.

Intertemporal Distortion

The corporate tax discourages investment and the capacity to produce goods and

services for future domestic consumption and exports (dynamic ineciency). It creates

a wedge between the pre-tax return and after-tax return on capital. The larger (smaller)

the wedge, the less (more) capital will be employed by businesses. Assuming the full

phasing out of accelerated depreciation (that begins in 2023), the existing corporate

income tax imposes a wedge equal to 19.5 per cent between pre- and post-tax rates

of return of capital with a higher wedge for services (e.g., communications at 22.1 per

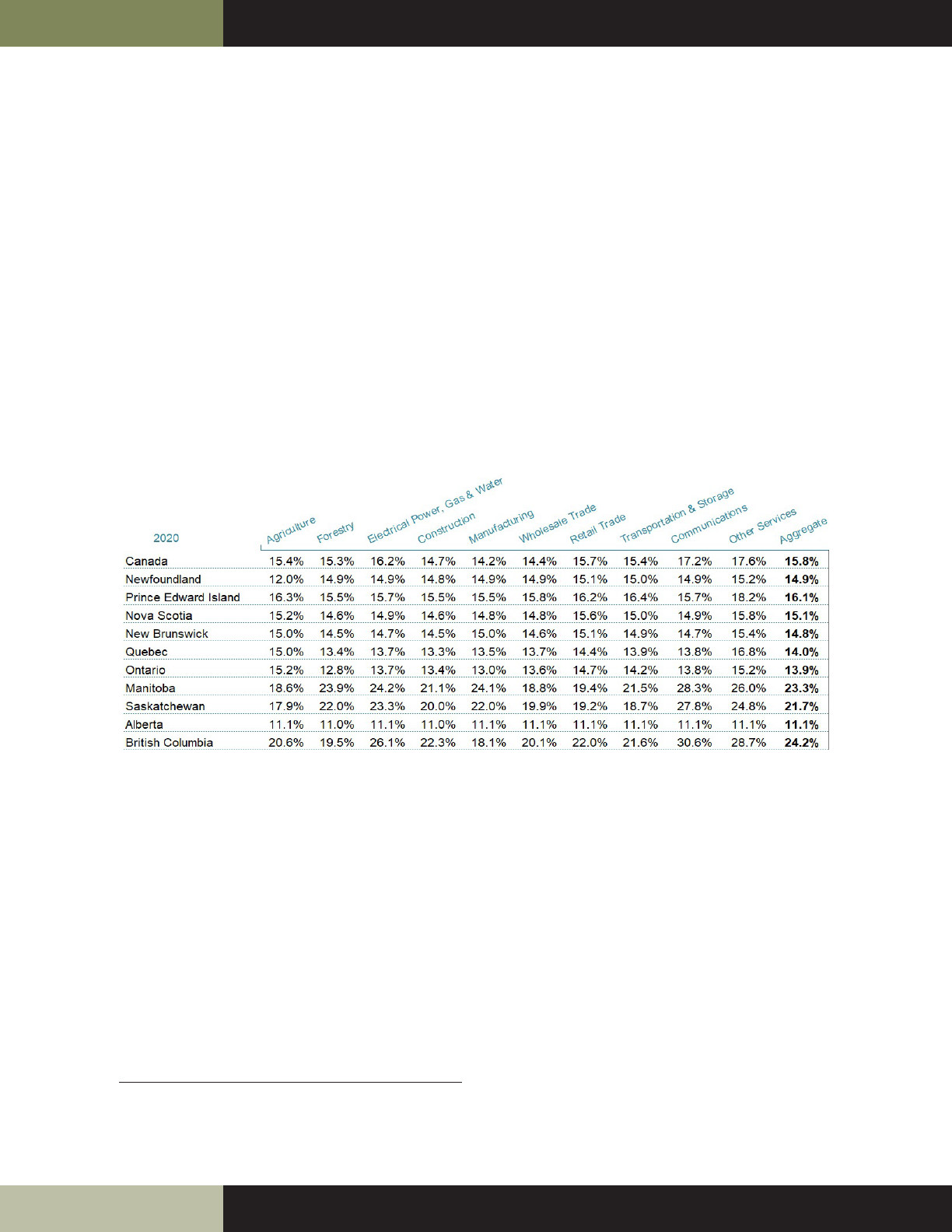

cent) compared to manufacturing and forestry (13.7 per cent) (Table 1).

Inter-industry and Inter-asset Distortions

Distortions in the corporate tax system result in a suboptimal use of capital in the

economy as capital is allocated to business activities with lower marginal economic

6

returns due to tax preferences.

10

Static eciency is illustrated by the dierentiation

in inter-industry and inter-asset eective tax rates on marginal investments (METR

11

).

As shown in Table 1, the variation is quite significant, even with the phasing out of

accelerated depreciation. Since 2015, Canada’s static ineciency has more than doubled

(Bazel and Mintz 2019). The eciency cost can be approximated as a dispersion index

(the weighted standard deviation of METRs per dollar of marginal tax revenue (Bazel

and Mintz 2019). The overall dispersion index in 2020 is 7.2 per cent, with the inter-asset

dispersion equal to 2.9 per cent and inter-industry dispersion equal to 1.5 per cent. Thus,

inter-asset distortions are more important than the inter-industry distortions.

Table 1. Federal-Provincial METRs by Industry and Province 2020

Note: Assumes accelerated depreciation is fully phased out. METRs measure corporate income taxes,

sales taxes on capital purchases, real estate transfer taxes and other relevant capital taxes as a share of

corporate profits earned on a marginal investment.

International Distortions

From a national perspective, a corporate tax in Canada could distort export and import

capital flows, in part depending on relative corporate tax rates elsewhere, assuming all

other economic factors are the same. The corporate tax encourages businesses to shift

their investment to lower-taxed foreign jurisdictions, leading to a loss of income and

employment in the Canadian economy. It also discourages foreign investors from lower

taxed jurisdictions to fund Canadian operations. A high corporate income tax incents

companies to shift profits to low-tax jurisdictions by booking expenses in Canada and

under-pricing goods and services sold to foreign aliates (transfer pricing). To that

end, the corporate tax should bear in mind the relationship of Canada’s corporate

10

Baquee and Farhi (2020) find that the static ineciency in the allocation of capital reduces productivity

by 15 per cent. Similarly, Da-Rocha, Mendes Tavaremal and Retuccia (2020) find that misallocation due to

dierential taxes on establishments causes substantial productivity losses — one-half due to the static eect

and the other half to a dynamic eect.

11

The marginal eective tax rate (METR) is explained in Bazel and Mintz 2021. Briefly, it is the amount of

corporate income tax, capital taxes, transfer taxes and sales taxes on capital purchases paid as a share of

corporate profits for marginal investments — those investments that earn sucient profit to cover the cost of

equity and debt financing.

7

income tax with that of other jurisdictions, while also considering international capital

flow distortions.

12

Including accelerated depreciation, Canada’s current METR on

manufacturing and services of 15.6 per cent is below those of the U.S., Europe, G7,

G20, OECD and 94-country averages, but our corporate income tax rate of 26.2 per

cent is higher than the U.S. (25.7 per cent), Europe (23.6 per cent) and the 94-country

weighted average (25.4 per cent) (Bazel and Mintz 2021).

13

New rules to limit interest

deductions for foreign companies operating in Canada and the minimum tax applied

by foreign countries on the income earned by their resident companies operating in

Canada could result in foreign-owned investments bearing a higher burden on capital

compared to domestic-owned investments.

Risk-taking Distortions

The corporate tax discourages risk taking by taxing the profits earned but not sharing

the losses incurred by investors (Mintz 1988). If profits and losses were treated

symmetrically under the income tax system, a government would be acting as a silent

partner in sharing risks. Given the lack of full refundability, non-risky investments

are tax-preferred and startup companies are less able to compete with profitable

incumbent firms in a market.

14

A simple example is the following: Suppose the expected return on farming is five per

cent: a 50 per cent chance of sucient rain so that a 15 per cent rate of return is earned

and a 50 per cent chance of a drought with a negative five per cent rate of return (the

expected return is sum of the probability times the rate of return in each state). If the

corporate income tax rate is 25 per cent and there is no refundability of losses, the

rate of return with sucient rain falls from 15 per cent to 11.25 per cent (the five per

cent loss in the drought remains the same since the government does not share the

loss). The after-tax expected return falls from five per cent to 3.13 per cent, implying an

eective tax rate of 37.4 per cent instead of 25 per cent.

One could adopt the full refundability of corporate tax losses and tax credits, at

least in principle, but this comes with three potential costs. The first would be a

shift of expenses into the corporate sector from personal tax to take advantage of

refundability that is not provided generally under the personal income tax. Second,

a corporate tax would make Canada a dumping ground for losses from abroad as

12

The OECD Base Erosion and Profit Shifting studies are reducing some of the international distortions but

cannot completely do so. Only a world of equal eective tax rates among all countries would achieve global

capital allocation neutrality.

13

The U.K. has announced it is increasing its corporate income tax in 2023 from 19 to 25 per cent (to be slightly

below the Canadian tax rate) and the Biden administration will be pushing for a higher corporate income tax

rate in the U.S.

14

Under Canadian tax law, some refundability is provided, but not full refundability. A company can carry back

operating losses for three years and claim a refund of past taxes paid for three years. It can carry forward

operating losses for 20 years to reduce operating profits in future years, although amounts are not indexed

for either inflation or borrowing interest rates. Capital losses can be carried back three years or forward

indefinitely but written o only against capital gains. Some taxable losses or credits are refundable, such as

research and development tax credits for Canadian-controlled private corporations and flow-through shares

of oil, gas and mining companies that renounce deductions in favour of investors who claim the deduction

under their personal income tax.

8

other countries do not provide full refundability for losses. Third, as found with the full

refundability of the research and development scientific credit in the early 1980s, tax

evasion could arise, such as investors moving to other countries after cashing refunds

without carrying out activities. Thus, one cannot expect limits on refundability resulting

in higher taxes on risky activities.

Financing Distortions

In the absence of taxation, corporations will fund capital expenditures with retained

earnings, new equity issues or debt. Retained earnings may be preferred since a

company uses internal resources rather than having to issue securities at a higher cost

to outside investors who have less knowledge about the firm. Debt is preferable to

lenders if they have a first claim to assets should the firm go bankrupt. New equity

issues attract a wider market of owners. Each financing source has its beneficial

economic attribute.

Since interest expense is deductible from corporate income (subject to certain

limitations), debt financing is encouraged compared to retained earnings and new

equity issue financing (Mintz 1995). However, interest paid to individual investors is fully

taxed under the personal income tax while dividends and capital gains are preferentially

taxed in recognition of the profits, prior to their distribution or reinvestment in the

company, having already been subject to one level of tax.

15

This can be seen in Table 2

with respect to taxes paid on income derived from a large Ontario corporation.

Table 2. Tax on Various Sources of Income Derived from a Large Ontario

Corporation (2021)

Dividend Paid to

Canadian Investor

Reinvested

Earnings

Profit Paid out as Deductible Expense (e.g., interest,

royalties, employment income)

Corporate Profits $100.00 $100.00 $100.00

Corporate Tax $26.50 $26.50 $0

Net Profit $73.50 $73.50 $100.00

Personal Tax (1) $28.91 $19.67 $53.47

Net Income $44.59 $53.83 $46.53

(1) Assumes the investor is the high-income investor. Dividend tax rate (39.34 per cent) includes the

dividend tax credit for eligible dividends. It is assumed capital gains tax rate of 26.76 per cent applies on

the gain realized in the same year.

Table 2 assumes corporate profits are taxed at the combined statutory federal-Ontario

rate of 26.5 per cent. The marginal investor for the Ontario company resides in Ontario,

paying a tax rate of 39.34 per cent on distributed profits (taking into account the

dividend tax credit). Reinvested earnings increase the value of the firm, dollar for dollar,

and, assuming the shares are disposed in the current year, are subject to capital gains

tax (only half of capital gains is taxed). Interest and other deductible charges paid out

as income to the investor are fully taxed.

15

If it is assumed that a dollar of retained earnings is invested in the firm’s capital, it increases the value of the

firm by one dollar. The capital gain for shareowners is subject to tax when the shareowner sells interests in

the company.

9

Given the relatively low capital gains tax rate, reinvested earnings are the least costly

form of finance from a tax perspective in this example. The combined corporate and

personal tax rate on reinvested earnings is 42.17 per cent. On bond interest and other

deductible charges, the tax rate is 53.47 per cent and on dividends, 55.41 per cent

(thereby discouraging new equity issues the most).

The financing distortions, however, are much more complicated than shown here:

• The corporate tax rate varies by size of business (a 13.5 per cent tax rate is

applied to the first $500,000 profits earned by Canadian-controlled private

corporations in Ontario). This increases the attractiveness of retained earnings

as a source of finance. The concessionary rate is clawed back when passive

income is more than $50,000;

• With tax incentives, the average tax rate (corporate income taxes as a share of

corporate profits) is lower than the general statutory tax rate. For example, in

the 2016 taxation year, the average federal corporate tax rate on net financial

income was 7.9 per cent

16

even though the statutory tax rate was 15 per cent.

This lower eective tax rate makes retained earnings and new equity issues

even more attractive since the dividend tax credit and concessionary capital

gains tax rate are based on a notional profit tax rate of 26.5 per cent;

• The lack of inflation adjustments results in the overstatement of profits

when depreciation and inventory valuation is based on historical rather than

replacement prices (even at an annual two per cent inflation, historical values

from 20 years ago are roughly two-thirds of today’s prices). However, interest

expenses, unadjusted for inflation, favour debt finance, which is becoming

even more important today with recent inflation rates after 2020;

• The investor often holds shares for a longer period than one year. If so, the

capital gains tax, which only applies to realizations, is deferred until the shares

are sold. Although interest rates are low these days, the deferral advantage

reduces the eective tax rate on capital gains. On the other hand, the lack of

full refundability for capital losses and inflation increases the eective capital

gains tax rate on real income;

• Pension plans do not pay tax on dividends, interest or capital gains but their

income derived from corporations is subject to corporate income tax. For

pension plans, debt finance (and other deductible charges such as royalties

and rents) is preferable to avoid corporate tax payments;

• Dividends and interest paid to non-residents are subject to Canadian

withholding tax (most interest is exempt from withholding tax by treaty).

• Capital gains as well as interest and dividends are subject to corporate or

personal income tax in foreign jurisdictions (with a credit for withholding

taxes). Overall, the tax paid by foreign investors varies from zero to the top

income tax rate in the country. Debt is often preferable if foreign investors pay

little tax on Canadian investments.

16

Based on the latest year available from the Canada Revenue Agency: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/

cra-arc/prog-policy/stats/t2-corp-stats/2012-2016/t2-crp-sttstcs-tbl10-e.pdf.

10

The choice of financing decisions, therefore, depends on relevant corporate and

personal income tax rates. The marginal source comes from investors who would be

indierent between equity and bond assets (Miller 1977). This implies that the marginal

investor would be taxed on income at equal eective tax rates on equity and bonds,

accounting for both corporate and personal taxes. Assuming binding constraints

limiting short selling of securities, other investors would only hold debt or equity

depending on their personal tax rates. Using Miller’s example, suppose the marginal

investor is not taxed on capital gains and dividends at the personal level but fully taxed

on interest. This would imply that the marginal investor holding Ontario stocks would

have a personal tax rate on interest equal to 26.5 per cent (those with higher personal

tax rates would only buy equity and those with lower tax rates would buy only bonds).

17

In a global context, the story becomes far more complicated since there are many

corporate income tax rates, as well as personal income tax rates.

18

An Ontario

corporation would have a lower corporate tax rate than one in Japan, which is currently

30.6 per cent. A Japanese corporation would have an incentive to invest in the Ontario

corporation’s equity, financing it with debt borrowed in Japan. An international capital

market equilibrium would result in the international marginal investor being indierent

between Japanese equity and bonds with the Ontario corporation being fully equity

financed by the Japanese corporation. Using the Miller assumption of a zero tax on

equity, the international investors would hold Japanese debt facing a tax rate of 30.6

per cent with higher income taxpayers buying Japanese or Canadian equity and low-

income taxpayers buying Japanese bonds (since the Canadian company would not

issue bonds).

Obviously, Japanese corporations would be unable to own all global corporate equity

in the world. Most important, companies do not go to the extreme of all debt or all

equity finance since they are trading o tax benefits with other economic factors,

such as default costs, signalling costs and use of tax losses (Mintz 1995). Complicated

international tax structures encourage indirect financing structures to take advantage

of interest, leasing and general administrative write-os for tax purposes (Mintz

and Weichenrieder 2010). The main point is that the simple case in Table 2 is not

representative. The financial decisions depend on the interaction of corporate and

personal taxes globally with corporate policies selecting clienteles to hold their

securities. A key conclusion is that countries with higher corporate income tax rates

like Canada would attract more debt finance in global markets, even if an international

marginal investor is indierent between Canadian and other international securities.

17

For indierence, the Miller equilibrium generally implies that u+ t(1-u) = m with u= corporate income tax rate,

t= personal income tax rate on equity and m = personal income tax rate on debt. With retained earnings

finance, in Ontario, u=.265 and t=.2675 and so u+t(1-u) = .426. The combined tax rate on equity income is

equal to the tax on bond finance when m = 42.6 per cent.

18

This discussion follows some very early work when I looked at multiple corporate income tax rates such

as the case of dierential corporate income tax rates on manufacturing and non-manufacturing profits

(Bartholdy, Fisher and Mintz 1987). See also Mintz and Weichenrieder (2010), chapter 3, comparing the eect

of corporate and personal taxes on financing decisions for parents, subsidiaries and conduit entities.

11

Business Organizational Distortions

Distortions also arise with respect to the organization of businesses, which can be done

in corporate or non-corporate forms, such as sole proprietorships, unlimited or limited

liability partnerships or trusts. When alternative vehicles receive better income tax

treatment than corporations, those businesses that are carried on in corporate form

for economic reasons suer a competitive tax disadvantage that distorts investment

and production.

19

The existing corporate tax system encourages the formation of

corporations compared to sole proprietorships and partnerships whose owners earn

income that is subject to a higher income tax rate.

Prior to October 31, 2006, trusts had been favourably treated since they could

distribute income to avoid payment of corporate tax with the distributions taxed

favourably as dividends (Mintz and Richardson 2006). With income trusts becoming

taxable as specialized flow-through income trusts (SIFTs) in 2006, the incentive to

reorganize companies as income trusts only remains for real estate investment trusts.

EQUITY

A major concern in corporate taxation is horizontal equity, the equal treatment

of taxpayers with similar resources under the tax system. Non-neutrality creates

unfairness where one segment of taxpayers carrying on a business activity are taxed

more favourably than another segment of taxpayers carrying on that same business

activity. This occurs, for example, with dierential corporate tax rates for dierent

sectors, with corporations, with dierent corporate tax rates for dierent types of

ownership or by use of more favourably taxed business vehicles.

As well, corporate taxation can be viewed by some as raising questions about

vertical equity, whereby taxes paid will vary according to ability to pay. For example,

corporations and their shareholders are paying at a lower tax rate than other

businesses or individuals who have lower incomes. As discussed above, the eect of

corporate tax on vertical equity is not straightforward. If corporate taxes fall on labour

income or on consumers through higher prices charged for goods and services, it

can be regressive. If it falls on capital, it will impact higher income Canadians more

heavily, but it will also reduce pension plan returns and those lower and middle-income

Canadians who own equity. The point is that the corporate tax is a clumsy way to

achieve redistribution through the tax system.

19

Goolsbee (1997) estimates the economic cost associated with organizational distortions is relatively small,

accounting for 10 to 20 per cent of corporate tax revenues.

12

COMPLEXITY AND ADMINISTRABILITY

The corporate income tax is often criticized for its high level of structural and legislative

complexity, resulting in high compliance costs for taxpayers and administrative costs

for governments. Complexity arises from various sources:

(i) Complex business arrangements that make it dicult to determine profit;

(ii) Policies that require a line to be drawn between targeted and non-targeted

activities, such as manufacturing, small business, clean energy and research and

development;

(iii) Constant changes to the corporate tax base and structure that require

transitional arrangements;

(iv) International flows of capital and income that require special rules to

determine profits subject to tax.

No doubt the corporate income tax is complex, particularly in the areas of

intercorporate and international activities. It is unrealistic to think that a corporate

income tax system will ever be simple, although some forms of taxation can reduce

compliance and administrative costs compared to others.

To conclude, the strongest arguments made for corporate taxation is with respect to

its neutrality to ensure it operates as a backstop to the personal tax, withholds income

(or rents) accruing to non-residents and performs, when needed, as an ecient benefit

tax. However, the existing system is failing at achieving these roles at a significant

economic cost.

WHY A “BIG-BANG” CORPORATE TAX REFORM TODAY?

Three economic reasons can be given for a big-bang corporate tax reform:

1. To rejuvenate private sector investment in Canada by reducing the intertemporal

distortion that would improve labour productivity, encourage the adoption of

new technologies and grow the Canadian economy;

2. To reduce inter-asset and inter-industry distortions in the corporate tax to

ensure capital is allocated to the best economic use;

3. To simplify the corporate tax system.

While Canada could pursue a strategy to improve the existing corporate income tax by

achieving greater neutrality, it is unlikely to deal with many distortions, in some cases

due to inherent diculties to avoid them, such as inflation, financing distortions and

risk taking. A new approach to corporate taxation would spur investment and improve

the allocation of capital resources.

Much has been written about corporate tax design. As discussed in detail above, the

Carter Report (1966) made a classic argument for a corporate income tax based on

comprehensive income. In later years, several important studies have argued in favour

13

of expenditure taxation, which would imply a tax on economic rents, the latter being

the surplus of income in excess of the opportunity costs of using capital, labour and

other inputs in production. The rent approach is discussed in the final section.

A third approach is a tax on distributed profits. One can view this as a deferral

approach to corporate taxation whereby profits from investment activities are only

taxed when they are distributed to investors, implying that profits reinvested in capital

are exempt from taxation (an exception would apply to passive income that would

be taxed at the corporate level). Deferral taxation has been used in various contexts

in the past. In many companies, foreign profits of subsidiaries have been taxed when

distributed to the parent company (and still prevails in some cases today). In Chile,

reinvested corporate profits have been taxed at lower rates compared to distributed

profits up until 2017.

The deferral approach is also used for capital gains taxation. Realized capital gains are

taxed only upon disposal and, in selected cases like venture capital or real estate, could

be deferred further if an investment is rolled over into another qualifying investment.

Realized capital gains may also be deferred for share exchanges when companies are

merged. The deferral of tax can result in much lower eective tax rates on capital.

However, with negative or low real interest rates in recent years, deferral is not as

beneficial as it once was.

The reason countries adopt such provisions is to reduce the ineciency of taxing

realized capital gains. A capital gains tax on disposals causes a locked-in eect

whereby an investor would rather hold a less well-performing asset for a longer period

rather than buy more profitable investments. Thus, rollovers remove a tax barrier to

readjust investment portfolios. A deferral approach for the corporate tax could also

have a positive impact on investments by enabling companies to postpone corporate

taxation if profits are reinvested in new capital projects for economic gain.

While Chile has disbanded its favourable taxation of retained earnings, some new

countries have adopted a corporate tax on distributed profits in recent years. Here, we

pay particular attention to Estonia’s corporate income tax.

ESTONIA’S CORPORATE PROFIT TAX ON DISTRIBUTIONS

In 2000, Estonia introduced a unique approach to corporate taxation applied to all

companies operating in Estonia (also adopted by Latvia in 2018). Instead of applying

tax to profits, only corporate distributions (dividends and other deemed amounts)

are taxed. The Estonian corporate tax exempts profits from active business income,

passive (investment) income and capital gains from the sale of assets. However, when

the profits are distributed to residents or non-residents, whether earned domestically

or internationally, they are subject to a 20 per cent tax

20

with further personal

tax on residents or withholding tax on non-residents. Distributed profits include

dividends, share buybacks, capital reductions, liquidation proceeds and deemed profit

20

The tax rate on dividends is equal to 20/80 or 25 per cent to be equivalent to the corporate rate of 20 per

cent on distributed dividends.

14

distributions. In principle, profit and loss accounting under the Estonian tax is irrelevant

since all profit distributions are taxed, even if the distribution is more than profits.

Although a country could levy a personal income tax rate higher than the corporate

income tax, Estonia has made its tax simpler by adopting a flat personal income tax

rate on residents at 20 per cent. Distributions are exempt at the personal level since

they have already been subject to the corporate tax.

Estonian companies are taxed on their worldwide income. However, with dividends

paid from profits received as dividends or branch income from other residents, the EU

and foreign entities with a minimum 10 per cent ownership are exempt from Estonian

corporate tax to avoid double taxation. Dividend income received from low-tax

countries or tax havens is deemed to be distributions when passed on to investors.

As of 2018, the tax rate was reduced to 14 per cent on distributions that are less than

the average of the past three years. However, such distributions are subject to a special

withholding tax of seven per cent on residents and non-residents (unless reduced by

treaty for non-residents to five per cent or zero).

Deemed dividend amounts include fringe benefits, donations, non-business expenses

and certain payments paid to entities in tax havens. Loans to shareholders may be

deemed to be hidden profit distributions. Stock dividends (share bonuses) are exempt

from the corporate tax. Gifts and donations made to certain qualifying recipients are

only subject to corporate tax if expenses exceed three per cent of the social tax base

for the existing year or10 per cent of the profit of the last financial year according to

statutory financial statements. Latvia also includes bad debts, excess interest payments

and transfer pricing adjustments as part of deemed amounts.

The result of the Estonian reform is to eliminate the corporate tax on reinvested profits.

Such profits would be taxed when the profits are eventually distributed. The profits are

defined as book profits with no adjustments for accelerated depreciation and loss carry

forwards/backs. Estonia eschews tax credits given its exemption for reinvested profits.

Among other policies, including a flat personal income tax, tax reform has made

Estonia quite attractive for investment. As we show in Bazel and Mintz (2021), it

had a 31 per cent increase in investment from 2015 to 2019 but overall growth has

picked up since its initial reform. Although not many studies have been published,

there is evidence the Estonian approach has contributed to a more robust business

sector. One of the few careful studies was done by Maso, Meriküll and Vahter (2011).

It shows that Estonian companies held more liquid assets and reduced debt after

the reform, enabling them to better withstand the 2008 financial crisis. They also

found improvement in both investment and labour productivity using a dierence-in-

dierence econometric approach that compares Estonia to other Baltic states.

Since 1999, corporate tax revenues in Estonia have increased fivefold from 105 to 509

million euros in 2019. As a share of taxes, corporate taxes made up 5.5 per cent of

revenues in 2019 (1.7 percent of GDP), compared to six per cent in 1999 (0,9 percent of

GDP), prior to the adoption of the new corporate tax system. In other words, there has

not been little erosion in corporate tax revenues.

15

The OECD discussions on base erosion and profit shifting has led to an agreement for

countries to impose a 15 per cent corporate tax rate on the profits earned by foreign

aliates of resident multinationals. Special provisions apply to those countries with

eligible distribution tax regimes whereby deemed distribution taxes would be included

as part of covered taxes to calculate the tax paid in the host country (OECD 2021).

A CORPORATE TAX ON DISTRIBUTED PROFITS FOR CANADA

Here, we look specifically at the corporate distribution tax to minimize tax distortions

and improve the investment climate. The basic elements of the tax on distributed

profits are proposed as follows:

• The corporate tax would be applied to distributed profits defined as dividends,

share buybacks and deemed corporate distributions related to items, including

the payment of non-business expenses and tax haven payments. There would be

no dierentiation in tax rates by sector or size of profit to minimize complexity;

• Distributions would be taxed without being limited by undistributed profit

accounts in the year

21

;

• Intercorporate dividends would be tax free between resident companies,

as under the existing corporate income tax, to avoid double taxation. Once

the tax is applied to corporate distributions of one company paid to another

company, it would be exempt from further tax on distributed profits thereafter;

• Profit distributions from aliates in treaty countries with at least 10 per cent

ownership would pass through to investors as exempt income. Otherwise,

foreign tax payments would serve as a credit to be claimed against the tax

on distributed profits. If a minimum tax is imposed on foreign aliates as

currently discussed internationally, it would apply to countries with a tax rate

of at least 15 per cent on accrued income;

• Canadian residents would receive a dividend tax credit based on the corporate

tax rate applied to deemed distributions from the corporations;

• Since reinvested earnings that increase the value of the company’s shares

are not taxed, a concessionary tax on capital gains on the sale of shares by

investors is no longer necessary. Thus, capital gains would be taxed at a rate of

100 per cent rather than subject to partial exclusion (inflation adjustments are

recommended to avoid taxing nominal capital gains) . Real estate capital gains

could be fully taxed (with inflation adjustment);

• Withholding taxes on dividends paid to non-residents would continue to be

applied according to treaty arrangements;

• While Estonia exempts all reinvested profits, whether sourced from income or

capital gains, the proposal is adjusted to include a refundable withholding tax

on investment income and capital gains earned by companies so that investors

21

This is the approach used in Estonia. It is possible to limit the tax on distributions to income earned in the

year and undistributed profits in past years. Distributions in excess of undistributed profits would be treated

as a return of capital.

16

have less incentive to use the corporate form to avoid personal income taxes.

This tax on passive income and capital gains reduces the deferral advantage

of leaving passive income undistributed to shareholders, following a similar

approach used for Canadian-controlled private corporations.

We estimate the revenue-neutral corporate tax on distributed profits would be 16 per

cent at the federal level (Table 3). The revenue-neutral corporate tax rate is estimated

using 2018 corporate dividend payment in Statistics Canada data. Share buybacks

are added as a proportion of dividends based on the Federal Reserve study for OECD

countries for 2012-2014 (15 per cent of dividends) (Federal Reserve 2017). Values are

brought forward to 2022/3 based on the Economic and Fiscal Update 2020 estimates

of corporate income taxes. The provincial average tax rate on corporate distributed

profits is estimated to be 11.2 per cent. That results in the same corporate tax revenues

collected as in 2022 ($37 billion). Dividend distributions could decline in favour of

retained earnings, but with the increase in the capital gains tax rate, it is not clear what

the ultimate impact would be on revenues.

One might be surprised that the revenue-neutral corporate tax on distributed profits

that exempts reinvested profits altogether is so close to the existing corporate income

tax rate (26.2 per cent). Corporate taxable income ($370 billion in the fiscal year

2022/3) is substantially below corporate operating profits ($515 billion) due to tax

incentives. Since reinvested profits are exempt, tax incentives, including non-refundable

investment and employment tax credits, no longer generate tax savings for companies.

In Table 3, any additional personal capital gains tax on realizations by moving to full

taxation of capital gains from disposing corporate shares is not included as revenue.

Some revenue loss would be experienced, resulting from a lower personal tax rate on

ineligible dividends, resulting from a higher corporate tax rate on distributed profits.

Any additional revenues could be used to reduce personal income tax rates.

Table 3. Revenue Estimate from Corporate Tax in Distributed Profits for 2022

Tax Base (billions) Federal Corporate Taxes (billions)

Projected 2022/3 Corporate Tax Base and Revenues* $370 $52.7

Corporate Operating Profits Before Tax $515

Dividends** $287

Deemed Distributions*** $43

Corporate Tax on Distributed Profits Base $330

Corporate Tax on Distributed Profits at 16 Per Cent $52.8

*Based on the Fall Economic Update, Finance Canada, 2020, https://budget.gc.ca/fes-eea/2020/home-

accueil-en.html.

**November Statistics Canada (n.d.) Table 36-10-0117-01. Includes dividends paid to residents and non-

residents.

***Includes share buybacks.

Using this revenue-neutral corporate tax rate of 27 per cent on distributed profits, the

METR on capital can be estimated (Table 4). The purpose of shifting from the existing

corporate income tax to a tax on distributed profits is to reduce the eective tax

17

rate on capital funded by reinvested profits to zero.

22

However, the tax on corporate

distributions would increase the cost of raising equity finance depending on the

dividend payout ratio (this argument is based on the traditional theory of finance

(Mintz 1995)). Other taxes, such as sales taxes on capital purchases and real estate

transfer taxes, continue to be applied.

Comparing Table 4 with Table 1 (where temporary accelerated depreciation is assumed

to have been fully phased out), we see that the average METR falls from 19.5 per cent

to 15.8 per cent. Several sectors would be more heavily taxed since tax incentives no

longer matter to the investment decision — these sectors benefited from low marginal

eective tax rates. Thus, the METR for manufacturing rises from 13.7 per cent to

14.2 per cent, primarily due to the loss of tax preferences in Quebec and the Atlantic

Provinces. The METRs remain highest in British Columbia, Saskatchewan and Manitoba

due to retail sales taxes that add to capital purchase costs.

Table 4: Corporate Tax on Distributed Profits at a 27 Per Cent Rate

EVALUATION

The corporate tax on distributed profits has several advantages in reducing distortions,

and some disadvantages.

Intertemporal Distortions

The intertemporal distortion would be reduced, indicating a greater demand for

investment, even under the traditional theory used here to model equity financing. If

investment is solely equity financed by retained earnings, the METRs in Table 4 would

be closer to zero, leaving retail sales tax on capital purchases in B.C., Saskatchewan

and Manitoba and property transfer taxes on capital investment (as well as annual

municipal property taxes that are not included in these calculations).

22

When retained earnings is the marginal source of equity finance, the dividend tax has no impact on

investment decisions. Distribution taxes are simply lump sum taxes with the opportunity of retained earnings

finance being the after-tax profit used to finance investment with the future discounted after-tax dividend

payments being return on investment. This has been referred to as the new view of equity finance, implying

that the distribution tax rate is irrelevant to the investment decision (Auerbach and Hassett 2003).

18

Inter-industry and Inter-asset Distortions

The variation in METRs across industries would be significantly reduced relative to

the current system. The range in METRs across industries is fairly tight: 14.2 per cent

in manufacturing to 17.6 per cent in services. In our analysis, we assume the same

financing ratios in order to focus on tax dierences. If dividend payouts vary across

industries (40 per cent for all firms), the METR variation would be greater than what

has been estimated. The overall dispersion index, discussed above, declines from

7.2 per cent to 0.3 per cent, substantially reducing inter-asset and inter-industry tax

distortions (the remaining distortions are related to sales taxes on capital purchases

and land transfer taxes). Obviously, the corporate income tax would be substantially

simplified, reflecting the reduction in policy-induced distortions.

International Distortions

The tax on corporate distributed profits would put domestic and foreign companies on

a level playing field from the perspective of Canadian corporate taxation. It would also

treat domestic and foreign investments made by Canadian resident companies equally.

It would reduce the incentive to borrow debt from abroad since interest deductions

would not aect the amount of corporate tax on distributed profits.

Risk-taking Distortions

Given that corporate tax would only be paid when profits are distributed, losses are not

relevant in determining the tax on distributions. The corporate tax, therefore, would

impose no additional tax on risky investments. A corporation with temporary losses

would pay its tax on distributed profits, but this would fall on investors as the dividends

distributed to investors would be reduced.

Financing Distortions

Compared to the existing corporate income tax, the tax on distributed profits

(including share buybacks) could create more neutrality among financing sources.

However, the impact of taxation on financial decision-making is complicated to

evaluate given the plethora of domestic and international personal and corporate tax

rates. As shown in Table 5 below for Canadian residents:

• Integration of corporate and personal income taxes is preserved for dividends,

employment income and other chargeable deductions (rents, royalties and

fees). The dividend tax credit would be based on the current treatment of

eligible dividends (at the federal rate of 16 per cent and provincial rate of 11

per cent). The combined corporate tax on distributed profits and personal

tax on dividends would be equal to the tax on employment income and other

deductible payments from the corporate tax base;

• As capital gains realizations from the sale of shares are fully taxed at the

personal level, the tax on capital gains realizations would be the same as that

on dividends, assuming shares are held for only one year. However, if shares

are held for longer periods, the personal income tax is deferred until the shares

19

are sold — this would lower the eective tax rate on capital gains, favouring

retained earnings as a source of finance;

• Given interest deductibility is of no value at the corporate level, companies

will have an incentive to reduce leverage compared to the existing system.

However, debt finance could be favoured relative to equity to avoid the

corporate tax on profit distributions if companies borrow from tax-exempt

pension funds or low-tax investors at home or abroad. If debt is borrowed

from tax haven entities or tax-exempt shareholders, the loan interest could be

deemed to be distribution of profits.

Under the existing corporate tax system, Canadian corporate and withholding taxes

are credited against foreign taxes. However, in the case of dividends paid by aliates

operating in Canada, these are generally tax exempt abroad by capital exporting

countries. Since only profit distributions are taxed by Canada under its corporate tax,

foreign companies will be discouraged to remit income to their parent, resulting in

some loss in Canadian tax revenues.

23

Given that Canada does not tax capital gains

earned by foreign investors (except for qualifying real estate and resource properties),

Canada might want to consider deeming capital gains upon disposal of assets by non-

residents as a dividend distribution.

Table 5. Tax on Income with an Ontario Corporate Tax on Distributed Profits

Dividend Paid to

Canadian Investor

Reinvested Earnings Employment, Interest or Royalty Income

Corporate Profits $100 $100 $100

Corporate Tax $27 0 $0

Net Profit $73 $100 $100

Personal Tax (1) $23 $50 $50

Net Income $50 $50 $50

(1) Assumes the investor is the high-income investor at a rate of 50 per cent. Dividend tax rate includes

the dividend tax credit equal to 27 per cent of pre-corporate tax distributed profits. Capital gains are fully

taxed.

Overall, the proposal would encourage foreign investors to reinvest profits in Canada.

Given that non-residents pay capital gains taxes to their home countries and not

Canada, foreign investors could have an advantage over Canadian investors in buying

Canadian assets if Canada moves to full capital gains taxation (the U.S. tax rate on long-

term capital gains is 20 per cent, close to the current Canadian capital gains tax rate).

Business Organization Distortions

The current corporate income tax favours the corporate form since the profit rate is

below the top personal income tax rate. With a corporate tax on distributed profits,

the tax on retained earnings would be deferred until the profit is distributed, thereby

providing an additional incentive to incorporation.

23

Roughly $50 billion in corporate dividends are distributed to non-residents.

20

In contrast, business income is attributed to owners of sole proprietorships, branches,

trusts and partnerships that are subject to current personal or corporate taxation. With

the ability to defer the profit tax, the corporate form of business organization would

have an advantage over other business organizational forms. Nonetheless, the incentive

to avoid current tax by leaving income within the corporation is lessened by taxing

passive income from reinvested profits.

OVERALL ASSESSMENT

A corporate tax on distributed profits provides several advantages in reducing

distortions. Being more neutral, it would be an improvement over the current corporate

income tax. However, it is not a perfect solution. Some investors will be able to defer

paying personal taxes by leaving profits in the company rather than distributing them.

On the other hand, to the extent that the existing corporate tax is shifted back on labour

or forward to consumers, the tax on corporate distributions might be less regressive

by primarily aecting the amount of profits distributed to investors. The corporate

tax would be substantially simplified by eliminating distinctions between eligible and

ineligible dividends since only one corporate tax rate would be applied to distributed

profits. As well, many rules associated with tax incentives would no longer be needed

since reinvested profits would be exempt from taxation.

24

Other anti-avoidance rules

may be required but, overall, the corporate tax system should be less complex.

Tax reform is never simple and raises a host of transition issues. Distributions paid from

past taxed profits would be taxed unless exempted initially. Pools of unused tax losses

carried forward from earlier years would no longer have value, resulting in a one-time

wealth tax.

This dierent approach to corporate tax reform could be implemented on an

experimental basis. For example, given Quebec and Alberta collect their own corporate

income taxes, they could try this approach first. However, the international issues would

be complex for provincial administration — a corporate tax on distributed profits might

need to apply regardless of whether the global distributions have already been taxed.

An allocation formula to determine distributed profits for a province would be needed.

To avoid negotiations over a new formula, the existing apportionment rules using

payroll and sales revenues could be used.

24

Investment tax credits could be provided by making them refundable against the corporate distribution tax.

21

CORPORATE TAX ON DISTRIBUTED RENTS

Economic rents are returns on an investment in excess of the normal net-of-risk return

on the investment. Another way of describing economic rent is the surplus income in

excess of the economic costs of production, including risk costs. In theory, economic

rents can be taxed heavily — even up to a 100 per cent tax rate — without reducing

the incentive to make the investment and produce from it. However, extremely high-

rent tax rates could encourage highly profitable projects to shift to jurisdictions with

lower tax rates. Given that risk costs are not observable, economic rents are less than

observable profits.

25

Much, though by no means all, of the activity that produces economic rents is carried

out by business corporations in the private sector. Such rents may be earned from

ownership of intellectual property and economic or regulatory barriers to entry

preventing competition, in addition to ownership of assets, such as natural resources

and land. This leads to the idea that, at the very least, corporations deriving earnings

in the form of economic rents should be taxed directly on those rents in order to

prevent the possibility of reducing the rent tax if it were only taxed at the shareholder

level. As some of these rents are shifted to other parts of the economy through higher

labour payments, for example, or internationally through licensing agreements, rents

need not show up as profit but instead be reflected as employment compensation,

royalties or fees.

The concept of a corporate tax applying to rents became popular among economists

in the late 1970s with the publication of the 1978 U.S. Treasury report headed by David

Bradford (1986) and the U.K. Meade Report (Institute of Fiscal Studies 1978). A key

point is that the imputed costs of debt and equity finance would be deductible from

the corporate base, unlike the measurement of shareholder profits, which only provides

for a deduction for the cost of debt finance.

Two methods have been suggested to tax economic rents:

cash flow and (economic) profit

bases.

26

The cash flow base would be revenue net of current and capital expenditure.

Given the expensing of capital expenditure, which is equivalent to the present value of

depreciation and financing costs, neither depreciation nor financing expenses would

be deductible from the tax base. The alternative approach is the economic profits base,

which is defined as revenues net of the economic cost of depreciation, debt interest

expense and an allowance for the corporate equity expense (ACE).

Although the cash flow tax approach has been used for mining and oil/gas rent

taxation (Chen and Mintz 2012), it has not been generally used for corporate taxation.

One reason is that the tax is not easily applicable to rent unless cash flow includes not

only real transaction flows, but also financial ones (Institute of Fiscal Studies 1978),

which can be quite complicated once dealing with financial innovations. Another is

that it works best with a personal tax applied to expenditure (earnings net of savings

25

A rent tax may not raise much revenue once risk costs are deducted.

26

Bradford (1986) proposed a cash flow approach. The Mirrlees Report (2011) recommended the economic

profits approach as an alternative rent tax.

22

or exempting the normal return to capital), as discussed in the Meade Report (1978),

Bradford (1986) and the Mirrlees Report (2011).

The economic profit approach has been more easily adaptable for the economy as a

whole. It has been implemented by providing an allowance for equity financing (ACE)

with equity including both retained earnings and shareholder-contributed capital. The

ACE is typically set at the government long-term bond rate (such as 10 years), which

in recent years could be negative.

27

The ACE was initially adopted in Croatia, but later

disbanded. It was then used in Belgium to replace its low-tax regime for headquarters

that was being challenged by the European system. Given the accelerating cost of the

ACE deduction, Belgium later limited the ACE to new equity issues, similar to Italy.

Today the ACE is used by several countries, such as Belgium, Brazil, Cyprus, Italy, Malta

and Turkey.

The cash flow and economic profit approaches are not the only ones. Another would

be to tax shareholder distributions net of equity issues (King 1987). Thus, the above

proposal could be adjusted by treating new equity issues as a negative distribution that

would be deducted from the tax base. If the tax base is negative, the amount could be

carried back or carried forward at an interest rate reflecting any risk should losses not

be eventually used. This would result in the neutral treatment of investment decisions

under the corporate tax. If the personal tax is also reformed by allowing savings to be

deducted (dissavings would be fully taxed and interest would not be deductible), it

would then parallel the corporate income tax, removing both corporate and personal

tax on the normal return to investment (rents would be taxed fully).

28

If only the corporate tax is changed into a rent tax, several consequences would be

involved.

First, treating new equity issues as a negative distribution would narrow the corporate

tax base, resulting in a higher corporate tax rate if corporate tax revenues are kept

constant. Using Statistics Canada data, the estimated revenue-neutral federal-

provincial corporate income tax rate would be 55 per cent if new equity issues were

subtracted from the distributed profits base.

29

A high corporate tax on dividend

payments would encourage companies to pass out rent in other forms of payment to

27

Belgium set the ACE to be equal to -0.16 per cent in 2021 for large companies and 0.34 per cent for small and

medium-size companies: https://www.oecd.org/tax/tax-policy/tax-database/corporate-and-capital-income-

tax-explanatory-annex.pdf.

28

Boadway and Tremblay (2014) recommend the corporate cash flow tax in Canada with dividends and

realized capital gains taxed at a rate of 100 per cent under the personal income tax (see also McKenzie

and Smart 2019). The corporate-only cash flow tax provides substantial benefits by not aecting the

investment decision, leaving aside the global personal tax eects on capital decisions. It also raises a number

of complexities that are not simple to address: consistency with the personal income tax, measuring the

appropriate exempt return on capital, taking into account risk, treatment of tax losses and international tax

planning considerations. See the Technical Committee on Business Taxation (1997) and Mintz (2018). See also

the discussion below regarding the mixing of a personal income tax with a rent tax on corporate distributions.

29

Calculations based on 2019 data from Statistics Canada.

https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3610011601.

https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3610057801&pickMembers%5B0%5D=2.6&cubeTimeFrame.

startMonth=01&cubeTimeFrame.startYear=2020&cubeTimeFrame.endMonth=01&cubeTimeFrame.

endYear=2021&referencePeriods=20200101%2C20210101.

23

resident and non-resident shareholders.

Second, the deductibility of new equity from the corporate tax base suggests that

it would be possible to eliminate the dividend tax credit and capital gains exclusion

preference since the corporate tax sole purpose is to withhold rents, not income

accruing to investors. However, with the deduction for new equity issues at the

corporate level, the corporate tax would be paid on that portion of profit reflecting

rents. Rents distributed to resident investors as dividends and capital gains, however,

would be double taxed. For example, if there is no dividend tax credit, the eective rate

on rents paid as dividends to an Ontario investor in Table 3 would be close to 67 per

cent. Non-resident investors may also be subject to double taxation on rents paid out

as dividends and realized capital gains. Companies will, therefore, look to avoid higher

tax rates on rents distributed as equity income by resorting to non-profit payments

that are deductible at the corporate level — employment compensation, leasing,

royalties, management fees, etc. It would also open new opportunities for domestic

and international tax planning that would need to be considered.

Nonetheless, as part of a major tax reform of both corporate and personal income

taxes towards rent-based taxation, the option of shifting to a rent-based corporate tax

on distributions is intriguing. It would need further study going beyond this paper.

CONCLUSIONS

Canada has taken many steps to reform its corporate income tax since 1985 by

reducing corporate rates and broadening the corporate tax base. However, Canada’s

corporate income tax remains distortionary, with high economic, compliance and

administrative costs. Even without politically motivated tax incentives, the lack of

indexation for inflation, imperfect loss refundability, international tax interactions and

other complexities make a perfect corporate income tax unachievable.

In recent years, the corporate tax reforms have been reversed with the introduction

of new tax incentives after 2015. Yet, these changes have failed to lead to a better

investment performance in Canada. If Canada is to build up its productive capacity in

the post-COVID world, a big-bang approach to corporate tax could be more successful.

Here, I propose converting the corporate income tax into a tax on distributed profits.

A business tax reform along these lines would put Canada into a unique position to

attract investment, as well as reduce many distortions in the business tax system. It is

not perfect, but it is better than what we currently have. It could also be turned into a

rent tax by treating new equity issues as negative dividends but this approach would

need fundamental reform of both the corporate and personal income taxes.

24

REFERENCES

Auerbach, A. J., and K. A. Hassett. 2003. “On the Marginal Source of Investment

Funds.” Journal of Public Economics, vol. 87, issue 1, January: 205–232.

Baker, Scott, Stephen Teng Sun, and Constantine Yannelis. 2020. “Corporate Taxes and

Retail Prices.” NBER Working Paper no. 27058. April. http://www.nber.org/papers/

w27058.

Baqaee, David, and Emmanuel Farhi. 2020. “Productivity and Misallocation in General

Equilibrium.” Quarterly Journal of Economics. Oxford University Press, vol. 135(1):

pages 105–163.

Bartholdy, J., G. Fisher, and J. Mintz. 1987. “Taxation and Financial Policy of Firms:

Theory and Empirical Application to Canada.” Economic Council of Canada.

Bazel, P., and J. Mintz. 2019. “Is Accelerated Depreciation Good or Misguided Policy.”

Canadian Tax Journal, vol. 67, issue 1: 41–55.

———. 2020. “The 2019 Tax Competitiveness Report: Canada’s Investment and Growth

Challenge.” SPP Research Papers. The School of Public Policy, University of

Calgary. March.

———. 2021. “2020 Tax Competitiveness Report: Canada’s Investment Challenge.”

SPP Research Paper, 14(21). The School of Public Policy, University of Calgary.

September.

Boadway, R., and J-F. Tremblay. 2014. “Corporate Tax Reform: Issues and Prospects for

Canada.” Mowat Research #88. Mowat Centre, University of Toronto.

Bradford, D. 1986. Untangling the Income Tax. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University

Press.