An analysis

of the implementation of the

EU-Canada Comprehensive

Economic and

Trade Agreement

(CETA)

Authors:

Julian HINZ, Carsten Philipp BROCKHAUS, Sonali CHOWDHRY, Hendrik MAHLKOW

and Vasundhara THAKUR (Kiel Institute, Germany)

European Parliament Coordinator:

Policy Department for External Relations

Directorate General for External Policies of the Union

PE 754.440 – November 2023

EN

IN-DEPTH ANALYSIS

Requested by the INTA committee

DIRECTORATE-GENERAL FOR EXTERNAL POLICIES

POLICY DEPARTMENT

EP/EXPO/INTA/FWC/2019-01/LOT5/1/C/20 EN

November 2023 – PE 754.440 © European Union, 2023

IN-DEPTH ANALYSIS

An analysis of the implementation

of the EU-Canada Comprehensive

Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA)

ABSTRACT

This in-depth analysis offers a quantitative analysis of the Comprehensive Economic

and Trade Agreement (CETA) between the EU and Canada, six years after its provisional

enforcement. Our analysis confirms substantial economic gains: goods exports from

the EU to Canada increased by 27 % and imports rose by 32 % due to the agreement.

The services sector also showed robust growth, with 19 % and 15 % increases in

exports and imports, respectively. However, the paper identifies challenges, such as the

low Preference Utilization Rate (PUR), predominantly among large firms, and highlights

that SMEs still account for less than half of the EU's total exports to Canada. Beyond the

immediate economic impact, the analysis focuses on key issues in the implementation

and offers further quantitative evidence on critical raw material policies and mutual

recognition agreements. Sections delve into a descriptive analysis of the bilateral

structure of trade, implementation challenges, and offer policy recommendations.

Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies

AUTHOR(S)

• Julian HINZ, Research Director, Kiel Institute & Bielefeld University, Germany;

• Carsten Philipp BROCKHAUS, Junior Researcher, Kiel Institute, Germany;

• Sonali CHOWDHRY, Senior Researcher, Kiel Institute & DIW, Germany;

• Hendrik MAHLKOW, Junior Researcher, Kiel Institute & WIFO, Germany;

• Vasundhara THAKUR, Junior Researcher, Kiel Institute & Bielefeld University, Germany.

PROJECT

COORDINATOR (CONTRACTOR)

• Julian HINZ, Project leader

• Emanuela DIMONTE, Management

This paper was requested by the European Parliament's Directorate-General for External Policies of the Union,

Policy Department for External Relations.

The content of this document is the sole responsibility of the authors, and any opinions expressed herein do not

necessarily represent the official position of the European Parliament.

CONTACTS

IN THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT

Coordination:

Wolfgang IGLER, Policy Department for External Relations

Editorial assistant: Balázs REISS

Feedback is welcome. Please write to

wolfgang.igler@europarl.europa.eu

To obtain copies, please send a request to poldep-[email protected].eu

VERSION

English-language manuscript completed in November 2023.

COPYRIGHT

Brussels © European Union, 2023

Reproduction and translation for non-commercial purposes are authorised, provided the source is acknowledg-

ed and the European Parliament is given prior notice and sent a copy.

This paper will be published on the European Parliament's online database, 'Think Tank

'

An analysis of the implementation of the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA)

3

Table of contents

1 Introduction 1

2 Structure of EU-Canada trade and investment 2

3 Overview of the economic effects of CETA on trade 5

3.1 Simulation scenarios 5

3.2 General introduction to the KITE model 6

3.3 Benchmark scenario results 8

4 In-depth analysis of key implementation issues 10

4.1 Impact of CETA for small and medium enterprises 10

4.2 Utilisation of trade preferences 12

4.3 Trade and sustainable development 17

4.4 Raw materials 19

4.5 Mutual recognition of standards and qualifications 21

5 Conclusions and recommendations 22

References 24

A. Technical description of the KITE Model 25

An analysis of the implementation of the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA)

1

1 Introduction

The European Union (EU) and Canada formally signed the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement

(CETA) in 2016. This agreement, provisionally implemented in September 2017, integrates several

advanced industrialized economies with a combined market size of USD 19 trillion and 480 million

consumers as of 2022. Beyond its clear economic significance, CETA also offers a strategic opportunity for

both partners to diversify their supply chains, ensuring the security of their trade flows amidst heightened

geopolitical uncertainties.

CETA also exemplifies the EU's and Canada's efforts to craft 'next-generation' FTAs. This is evident in its

numerous provisions addressing a wide range of regulatory topics including government procurement,

competition policy, intellectual property, and investment protection. These provisions specifically target

non-tariff barriers (NTBs) to trade and play a substantial role in determining the overall welfare gains from

FTAs. Alongside these modern provisions, CETA also successfully eliminates traditional barriers to trade in

goods, with 98 % of tariff lines becoming duty-free between the parties in 2017.

In addition to this broad scope, CETA introduced several innovative provisions that distinguished it from

other FTAs that were in force at the time of its provisional application. For instance, it takes a more

comprehensive approach toward regulatory cooperation, with the establishment of a dedicated forum to

promote continuous dialogue on these issues between the EU and Canada. It also features a dedicated

chapter on trade and sustainable development that commits both parties to upholding standards for

environmental protection and labour rights. CETA also incorporates specific provisions designed to

support small and medium enterprises (SMEs), in view of the unique barriers faced by them when

exporting to foreign markets. In these dimensions, CETA provides a useful blueprint for how trade deals

can evolve beyond traditional tariff reductions to encompass broader socio-economic and environmental

goals.

Considering the timeline, formal negotiations for CETA were launched in May 2009 and spanned over five

years until their conclusion in August 2014. Following legal review, the agreement was officially signed in

October 2016 after which it was provisionally applied from September 2017. As a ‘mixed’ agreement, CETA

requires ratification not only from the European Parliament but also from all national and regional

parliaments within the EU's member states. This is because the agreement encompasses areas of policy

that fall both within the sole competence of the EU and within the shared competence of the EU and its

member states. Examining the progression of the approval process, CETA gained ratification from seven

EU member states in 2017. Since then, an additional ten countries have endorsed the agreement, with

Germany being the most recent, finalizing its ratification in January 2023. Yet, ten EU member states have

yet to ratify CETA. Notably among these are key players in trade with Canada, including France, Italy, and

Belgium.

Now in CETA's sixth year of implementation, this in-depth analysis aims to provide a rigorous quantitative

assessment of the agreement's impact on trade flows and welfare. It sheds light on which sectors and

countries have gained most from CETA's application and discusses several outstanding issues relating to

the implementation. As such, this analysis is related to previous work that has, i.a., predicted ex-ante

possible effect on FDI, trade, and its macroeconomic impact (see e.g., Anderson et al., 2016; Breuss, 2017),

as well as highlighted legal question relating to the agreement (see e.g., Finbow, 2019). Notably Anderson

et al. (2016) use an approach that is in theory related to our approach and – reassuringly – yields quali-

tatively similar results.

1

1

As discussed subsequently, their results show Canada as gaining more from the agreement than an average EU economy. This

stems from the fact that Canada acquires access to a relatively larger market than an average EU economy does for Canada.

Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies

2

The remainder of this analysis is structured as follows. Section 2 describes the evolution of trade in goods

and services as well as investment flows between the EU and Canada over the last years. In Section 3, we

outline our methodology for evaluating the impact of CETA and discuss the results from our benchmark

scenario of the agreement's implementation. In Section 4, we focus on key implementation challenges

related to CETA and assess their possible effects on welfare in the EU and Canada. Finally, Section 5 provides

a conclusion to our analysis and offers policy suggestions.

2 Structure of EU-Canada trade and investment

We begin our analysis by examining both the structure and evolution of trade flows and investment

relations between the EU and Canada over recent years. This descriptive evidence sets the stage for our

subsequent investigation of CETA's economic impact with the general equilibrium model.

Table 1: Trade in goods: summary of CETA provisions

Goods

Provision

Industrial products

99.5 % tariff free at implementation (September 2017)

Forest products

duty free at implementation

Metal products

duty free at implementation

Oil and gas products

duty free at implementation

Chemical and plastics products

duty free at implementation

Telecommunications products

duty free at implementation

Phase-out in sensitive sectors

gradual implementation or via tariff rate quotas (TRQs)

Fish and seafood products

95.5 % tariff free rising to duty free in 3-7 years using TRQs

Agriculture

gradual with exemptions/TRQs in sensitive products

Automobiles

duty free in 3-7 years

Overall goods trade

98 % duty-free at implementation (21 September 2017)

99 % duty-free as of 1 January 2024

Note: Table adapted from Finbow (2019).

Trade in goods

As of 2022, Canada is the EU's tenth largest trade partner for goods exports and its 16th largest partner for

goods imports. For Canada, the EU is the second-largest trading partner in goods. CETA supports this trade

by eliminating over 98 % of tariff lines

2

over relatively short implementation schedules (see Table 1).

Figure 1 provides a comprehensive view of the evolution of trade in goods between EU and Canada over

the period from 2012 to 2022. Panel 1a sheds light on EU members’ exports, with the red line denoting the

entry into force of CETA. On average, EU members’ exports to Canada grew by 36 % over 2017-2022.

However, a few countries stand out. The member with the highest export growth was Latvia, whose sales

to Canada soared by 177 %. Cyprus, the lowest contributor to EU exports in 2016, also significantly

increased its sales to Canada by about 76 %. In contrast, the Netherlands registered the lowest export

growth of 12 %. Germany, which leads the bloc in terms of total exports to Canada, also experienced an

18 % rise in sales over 2017-2022.

2

See https://policy.trade.ec.europa.eu/eu-trade-relationships-country-and-region/countries-and-regions/canada/eu-canada-

agreement/ceta-chapter-chapter_en for the text of the agreement.

An analysis of the implementation of the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA)

3

Figure 1: Evolution of EU goods trade with Canada

(a) Evolution of EU exports to Canada (b) Evolution of EU imports from Canada

Note: Data from UN COMTRADE, own visualization.

Panel 1b reveals key trends in EU members’ goods imports from Canada. Germany maintained its lead in

overall imports from Canada between 2017 and 2022, witnessing an increase in import purchases of

approximately 58 %. The EU average was slightly lower, with imports growing by 48 %. Interestingly,

Cyprus, which initially had the lowest import figures, more than doubled its imports from Canada by 2022.

France registered the lowest growth at about 15 %, while Latvia recorded an astonishing surge of 1134 %,

indicating a highly diverse level of engagement among EU countries with respect to imports from Canada

after the implementation of CETA.

Together, these trends further indicate that goods trade between EU and Canada stayed resilient during

the pandemic period, despite the decline in global trade (International Monetary Fund, 2022).

Having examined changes in aggregate goods trade, we next analyse their sectoral composition in 2019

(i.e., just before the pandemic), comparing the EU’s trade with Canada with its other trade partners (see

Figure 2). Panel 2a displays the export side. It reveals that manufacturing, particularly the metals and

machinery sector, is a cornerstone of EU exports, constituting more than half of the bloc’s exports to

Canada, other EU members, and to the rest of the world. This suggests the EU’s comparative advantage in

this sector across multiple markets. The chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and plastics sector is also important

across all three types of destinations, with shares in exports lying in the range of 25–29 % each. Notably

different in their relative importance in the three different markets are agricultural products, which only

make up 0.6 % of exports to Canada, but 1.4 % to the rest of the world.

Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies

4

Figure 2: Comparison of top EU export and import sectors by partner

(a) EU exports sectors (b) EU imports sectors

Note: Data from UN COMTRADE, own visualization.

Panel 2b reveals the heterogeneity in origins for EU goods imports. Again, we find that the metals and

machinery sector dominates the import landscape, accounting for over 40 % of imports from Canada and

more than half from intra-EU and the rest of the world. The chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and plastics sector

also appears again as a key import category, with relatively similar shares in imports (20–26 %) across

different origins. However, the mining and extraction sector is distinctly significant when it comes to

imports from Canada, making up nearly 20 % of the total imports from the country, a level that is much

higher than from other trading partners. This points to specialized trade relations between the EU and

Canada in this sector. Overall, the varied sectoral composition in the EU’s import basket is more

pronounced than on the export side.

Bilateral Investment

While the investment provisions in CETA have not yet been applied and still require the full ratification of

CETA by all EU member states, investment flows may still already be affected by closer economic

cooperation between the economies of the EU and Canada.

3

Figure 3 visualises the evolution of inward

and outward FDI stock between EU member states and Canada between 2013 and the latest available year,

2021. The light green line depicts outward investment by European companies, whereas the teal line

depicts Canadian investments in the European Union. Initially, investment flows, especially flows into the

EU, started to increase, reaching a first peak of EUR 324 billion and EUR 362 billion, respectively, in 2016.

This was followed by a slight decrease in 2017, before reaching the maximum in 2018, i.e., one year after

CETA provisionally entered into force, which may hint towards an anticipation effect. Flows then decreased

between 2019 and 2020 and seem to have reached 2016 levels at the end of the observed period. The

COVID pandemic may have stalled an overall positive trend in the integration of the two economies.

3

See https://trade.ec.europa.eu/access-to-markets/en/content/eu-canada-comprehensive-and-economic-trade-agreement for

an overview of the agreement including a description of the areas not yet applied provisionally.

An analysis of the implementation of the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA)

5

Figure 3: Evolution of investment stocks between EU member countries and Canada

Note: Data from UN COMTRADE, own visualization.

Interestingly, inward and outward investment follow a very similar path over the time period. While out-

ward investment is initially somewhat higher than inward investment, over time the two types of flows

show a strong comovement.

3 Overview of the economic effects of CETA on trade

Evaluating the economic effects of a trade agreement on trade (and investment) flows is a complex

exercise. While the descriptive analysis in Section 2 shows that exports, imports and investment patterns

between EU and Canada have evolved over time, they do not clarify whether these changes can be partially

or fully attributed to CETA's implementation. Put simply, one needs to address the question as to what a

counterfactual world today would look like, had there not been an agreement.

To do so, we make use of a state-of-the-art quantitative model that allows us to compute these counter-

factual scenarios of the global economy – with and without CETA, as well as with possible future policy

changes. We conduct these simulation exercises with the so-called KITE model (Kiel Institute Trade Policy

Evaluation Model) and discuss its main mechanisms in subsection 3.2. Additional technical details of KITE

are provided in Appendix A.

3.1 Simulation scenarios

To gauge the impact of CETA, we analyse three distinct scenarios with the KITE model. The benchmark

scenario addresses the central research question of this in-depth analysis: How did CETA influence trade

flows, and what were the differential impacts across various countries and sectors? The subsequent

scenarios address more specific questions that relate to key implementation issues under CETA which are

discussed in further detail in Section 4. Each scenario here builds upon the results from the benchmark

simulation – an evaluation of the current impact of CETA – and adds key policy changes on top of the

baseline reduction in trade barriers. The corresponding simulation results are thus relative to the status

quo of the global economy.

Note that even though the policy changes implemented both in the benchmark scenario as well as the

additional scenarios for key implementation issues are purely bilateral between member countries of the

EU on the one hand and Canada on the other hand, the model will also indicate third-country effects. This

is an important feature of the KITE model, whose structure specifically incorporates possible trade creation

Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies

6

and trade diversion effects, which translate bilateral policy changes into measurable global economic

effects.

Scenario 1 Benchmark scenario

In our first scenario, we examine the overall effect of the implementation of CETA on the economies of EU

member states, Canada, as well as affected third countries. We do so by simulating the removal of tariffs

between the contracting parties, as well as the impact of estimated changes to non-tariff barriers.

4

Note

that the CETA does not alter the Most Favoured Nation (MFN) or preferential tariffs imposed by the

members' economies on imports from non-CETA countries. Accordingly, this scenario maintains the same

rates for external tariffs as in the status quo. The estimation of the changes to non-tariff barriers is

conducted in standard fashion, making use of the gravity framework in international trade at the sectoral

level.

5

Scenario 2 Strategic partnership on raw materials

In this second scenario, we further expand the scope of trade liberalization achieved by CETA by simulating

a strategic partnership on raw materials. We again implement this policy change by additionally lowering

NTBs by a further 5 % on raw materials. All other sectors remain unaffected beyond the already implement-

ed tariff and NTB reductions induced by the actual CETA implementation.

Scenario 3 Mutual recognition of qualifications

Like the previous scenario, we expand the scope of CETA by lowering NTBs in the services sectors that

would be plausibly affected by mutual recognition agreements on professional qualifications. Specifically,

and following the related literature (see e.g., Kox et al., 2005), we simulate the reduction of friction in the

sectors of health and social work, education, construction, insurance and finance, as well as other business

services by – again – 5 %.

3.2 General introduction to the KITE model

To simulate the outlined scenarios, we leverage the KITE model (Chowdhry et al., 2020), a model that offers

a computable general equilibrium representation of international trade and the global economy,

drawing

its foundational structure from the trade model by Caliendo and Parro (2015).

6

The model

exhibits intra-

and international input-output relationships, reflecting the international dimension of production. Thus, it

implements the main features of today’s world economy, emphasizing the intricate interconnections

between countries through global value chains (GVCs). In the context of our analysis,

it’s crucial to note

that countries not participating in CETA may also experience the effects of the agreement.

By utilizing the KITE model, we juxtapose a baseline scenario (a world without CETA) against

scenarios

involving varied degrees of actual and hypothetical future CETA implementation. Through this

comparison, the model allows the quantification of long-term direct and indirect trade impacts on Canadian

4

While there is some sectoral heterogeneity in the tariff lines that were actually affected – 2% of the pre-existing tariffs persist –

the more aggregated sectoral composition of the model does not allow for this heterogeneity. We therefore remove 100% of all

tariffs. Robustness checks with respect to leaving out the few sectors with most remaining tariffs, agricultural and food products,

produce qualitatively very similar overall results. In doing so, this scenario effectively provides an upper-bound to the impact of

tariff reduction.

5

As is customary in related literature, we verify that estimated coefficients are realistic. Specifically, we truncate the estimated

trade cost change at 0 – i.e., we do not allow CETA to have a negative effect on trade flows. Furthermore, we only use statistically

significant estimated values, insignificant ones are again set to 0. Effects for services trade are set to the average estimated effect

across sectors. Trade elasticities are taken from Fontagné et al. (2022).

6

A technical overview of the model is given in Appendix A.

An analysis of the implementation of the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA)

7

and European economies.

7

It’s also useful for evaluating CETA’s possible impacts on countries’

overall

welfare (defined as real consumption expenditure). The assessment spans over 65 sectors and 141

countries (plus groups of smaller countries), representing over 90 % of worldwide economic activities. In

this paper, the discussion is primarily concentrated on the impact of the agreement on CETA members, i.e.

the EU-27 and Canada, with 2021 as the baseline year—being the most recent year with reliable bilateral

trade flow data.

8

This evaluation also incorporates the ramifications of the COVID-19 pandemic on the

scale and structure of global trade.

9

Notably, utilizing 2019 as a base

year does not significantly alter

the outcomes, suggesting a structural consistency in the global, and

notably, Canadian and European

trade linkages.

Figure 4: Global welfare change in benchmark scenario

Note: Own computation.

Within the KITE model, the CETA agreement is implemented through changes in trade costs, addressing

the components of NTBs and tariff adjustments separately. Standard data sources are employed for the

calibration of the model. The GTAP 10 global input-output database (Aguiar et al., 2019) supplies extensive

details on intra-national sectoral connections and GVCs. Additionally, we resort to other standard

databases like UN Comtrade for trade data, and WITS and MacMaps for customs data, to construct the so-

called initial conditions for the computation of the benchmark scenario in our model. Eventually, several

parameters not directly observable are estimated using econometric approaches or taken from the related

academic literature. These include so-called ‘trade elasticities,’ which represent the degree of responsive-

ness of sectoral trade flows to changes in trade costs in those sectors – e.g., due to tariffs or NTBs. We further

estimate the changes in non-tariff barriers utilizing the renowned gravity model of international trade

(Head and Mayer, 2014).

7

The model, however, does not incorporate FDI due to the absence of exhaustive bilateral investment data at the sectoral level.

8

The trade flow data for 2022 is still unreliable due to reporting lags and is therefore not sufficient for simulations. For 2022, the

number of countries reporting their data stands at 141 as compared to 163 for 2021.

9

Note that outcomes are not significantly altered when using 2019 as a baseline year in robustness checks, suggesting structural

consistencies in global as well as Canadian and European trade linkages.

Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies

8

3.3 Benchmark scenario results

We now move towards analysing the economic impact of CETA under the benchmark scenario. As

discussed above, in this scenario we adjust bilateral trade costs in the model to the actually applied

changes from CETA’s provisional implementation.

Figure 4 shows the global welfare change due to the agreement. While overall the welfare impact is

modest, a few points stand out. First – as one would expect – EU economies and Canada stand to benefit

most from the agreement. Lower trade barriers vis-à-vis each other translate ceteris paribus into lower

prices and higher incomes. There is, however, a notable number of third countries that is negatively

affected by the agreement. Several African, Central American countries, as well as Central and South-East

Asian economies are – albeit marginally – worse off, as trade diversion leads European and Canadian firms

to trade more with each other at the expense of previous trading relations with companies in these above-

mentioned countries. Overall, the magnitude of the effect remains modest, however, as the most adversely

affect country – Botswana – loses 0.08 % in terms of welfare, while the bulk of negatively affected countries

sees welfare decreases in the economically insignificant range of up to 0.01 %. Those that see a negative

impact are either already economically integrated with one of the partners and effectively – in relative

terms – lose some of their preferential access – like Mexico, which through NAFTA and USMCA enjoys deep

integration with Canada, or, they are competitors in terms of export structure, like some African and Central

Asian countries where mineral exports make up a significant share of their exports. For most of the rest of

the world the third-country impact is very limited and effectively insignificant.

Figure 5: EU welfare change in benchmark scenario

Note: Own computation.

Zooming in on the map for a closer look at the European continent (Figure 5), the modest but significantly

positive impact of the agreement for EU economies becomes clear. The biggest winner in terms of growth

in welfare is Malta, closely followed by Ireland, with gains of about 0.09 %. The effect likely stems from the

bilateral liberalization of services sectors, which feature significantly in the two countries' economic

An analysis of the implementation of the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA)

9

structure. Importantly, but not surprisingly, Canada also registers significant welfare gains by getting

preferential access to its second most important trading partner.

Figure 6 decomposes these aggregate effects across sectors for the EU. It does so by mapping the change

in exports on the horizontal axis against the respective industry’s change in total production on the vertical

axis. The exercise demonstrates an important mechanism for most industries: an increase in exports to

Canada is associated with an overall increase in production – hence trade creation effects largely dominate

potential trade diversion effects. This is important: it explains that third-country effects are rather small, as

affected flows to Canada are effectively newly-created. This is particularly the case for the manufacturing

sector, which remains an important pillar of EU economies – as visualised by the size of the points. Services,

too, exhibit this behaviour, although their relative size is bigger in smaller economies, such that the overall

effect remains smaller.

Note also that some industries see a reduction in production while at the same time exporting more to

Canada than in a scenario without CETA: in these sectors, consumers will import a larger share from abroad

--- predominantly from Canada --- as trade costs have fallen and hence domestic production decreases.

Yet, at the same time, these reduced trade costs also imply that, of the remaining production, a larger share

is exported to Canada.

The impact on these sectors – the EU’s agricultural, food, mining, and extraction sectors – is hence notably

different. While these sectors do not hold as much economic weight in EU economies as manufacturing or

services (as evidenced by the smaller dots), their contraction under CETA, with production decreasing by

up to -0.9 %, does affect some smaller EU members.

Figure 6: Change in exports from EU member states to Canada and change in production

Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies

10

Figure 7: Global welfare change in benchmark scenario: Winners and Losers

(a) Top global welfare change (b) Bottom global welfare change

Overall, the benchmark simulation results show that within the first 6 years of its provisional entry into

force, CETA has delivered a substantial boost to trade in goods from the EU to Canada and vice-versa by

27 % and 32 %, respectively, and services by 19 % and 15 %.

10

The agreement has led to change in welfare

for participating countries of up to 0.1 % under KITE's benchmark scenario (Figure 6). Globally, countries

that see a decline in welfare do so on average by less than 0.004 %, whereas the 58 countries that

experience an increase in welfare do so by on average more than 0.01 %.

4 In-depth analysis of key implementation issues

While CETA has delivered growth in bilateral trade since its application in 2017, there remain several

challenges to the full realization of the agreement’s benefits. These challenges bear significance not only

for trade outcomes, but also for concurrent objectives of the EU such as environmental conservation, the

promotion of small enterprises, and the establishment of secure, resilient supply chains.

Therefore, in this section, we highlight five key implementation issues for CETA and provide an overview

of the latest developments within each area. Where feasible, we link these issues to different simulation

scenarios under the KITE model to provide a quantitative assessment of their impact on welfare for the EU

and Canada.

4.1 Impact of CETA for small and medium enterprises

One persistent concern during the design and implementation of CETA has been whether the benefits of

trade liberalization would reach SMEs. SMEs face unique barriers to trade, such as limited access to financial

resources, lack of information on foreign market conditions and high fixed costs associated with

establishing distribution networks.

10

Note that these are numbers originate from the simulation analysis. Actual observed trade numbers may differ – and reflect

other trade cost changes over time. According to Eurostat, e.g., the EU’s imports from Canada and exports to Canada saw an annual

average growth rate from 2018 to 2022 of 10.8% and 7.7 % respectively.

An analysis of the implementation of the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA)

11

Given the aforementioned challenges, CETA has integrated targeted provisions to bolster trade led by

SMEs. These provisions focus on the creation of specialised online portals and contact points, ensuring

firms have access to essential information concerning market entry requirements and customs procedures.

In line with these goals, the EU has also launched its Access2Markets platform in October 2020 that

supports SMEs with practical information on FTAs and trade barriers. The dedicated SME provisions also

foresee an appropriate institutional set-up tasked with ensuring that SME needs are taken into account in

the CETA's implementation.

Figure 8: Firms size and exports to Canada

(a) Share of value in exports (b) Share in number of firms

Note: Data from Eurostat. Share of value and number of firms by size in total EU exports to Canada over time.

While the KITE model does not permit an explicit examination of the impact of CETA on SMEs, we can

however explore the firm size dimension of EU-Canada goods trade since the agreement's implementa-

tion.

We do so in Figure 8, which visualises the share of firms of varying sizes in EU exports to Canada by the

value (left) and number of exporting firms (right). The left panel reveals that larger firms (in terms of

employment) account for the majority of EU exports to Canada. Firms with 250 or more employees hold a

persistent share of approximately 60 %, whereas micro enterprises with fewer than 10 employees exhibit

the lowest export share. Since 2017, firms with less than 250 employees have gained only marginally,

capturing additional 2 percentage points in their share of total EU exports to Canada.

Looking at the number of firms exporting to Canada, the previously observed order is reversed. Here, firms

with less than 10 employees account for roughly 25 % of total exporting firms, whereas large firms have

the lowest share. This size composition is largely stable, though SMEs with fewer than 50 employees were

able to slightly increase their share over time.

Overall, we find that the size distribution of EU export value and number of exporters has been fairly

consistent over time. The data therefore suggests that while CETA might have helped SMEs maintain their

trade with Canada, it hasn't reduced the prevailing dominance of large firms.

Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies

12

Figure 9: Share in exports to Canada across firm size

Note: This figure reports the distribution of country exports to Canada across firms of varying sizes (as defined by the

number of employees). Data is drawn from Eurostat for 2021 or the latest year available.

Figure 9 delves deeper into the role of firm size in EU exports to Canada. The data underscores significant

heterogeneity among countries. Slovakia displays the highest concentration in its exports, with 92 % of its

sales to Canada driven by large firms. At the other end of the spectrum, we note that Cyprus displays a

minimal dependence on large firms (17 %). Key EU exporting nations to Canada, such as Germany and

Belgium, also demonstrate substantial large firm involvement, with shares of 85 % and 82 %, respectively.

Interestingly, Croatia, Cyprus, and Latvia see considerable contributions from micro-sized firms (with fewer

than 10 employees) in their exports to Canada. Overall, Figure 9 highlights the major role that large firms

play in the export relationship between the EU and Canada.

4.2 Utilisation of trade preferences

Upon CETA's provisional entry into force in 2017, 98 % of Canada's tariff lines became immediately duty-

free. While such provisions on tariff liberalization are notably extensive, the actual utilization of preferences

by trading firms warrants further examination. We, therefore, turn towards examining recent trends in the

EU's Preference Utilisation Rate (PUR) in its exports to Canada – calculated as the ratio of exports that use

preferential tariffs to those that are eligible for such benefits.

An analysis of the implementation of the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA)

13

Figure 10: Evolution of PUR across HS sections

Note: This figure reports the evolution of PURs from 2019-2021 for EU exports to Canada across various HS sections. Data is

drawn from Eurostat.

Figure 10 reports the PUR on EU exports to Canada for the latest years. It reveals substantial variation across

HS sections, with PUR being high for agri-food industries such as animal products (99 %), prepared

foodstuffs (89 %) and vegetable products (85 %) in 2021. In comparison, PUR was lower in manufacturing

industries such as transport equipment (45 %), machinery and mechanical appliances (53 %) and chemical

products (56 %).

Besides this sectoral heterogeneity, we also observe a marked increase of 10 pp. (from 48 to 58 %) in the

PUR for the EU's exports to Canada across all products from 2019 to 2021.

11

Furthermore, this growth in

PUR is seen to be driven by multiple sectors, being particularly sharp for mineral products (24 pp),

transportation equipment (18 pp) and miscellaneous sectors (18 pp). This evolution in PURs suggests that

– on average – companies may be progressively learning and adapting to the provisions of the

agreement.

12

In Figure 11, we further disentangle the variation in PURs by comparing the performance of different

country-sector pairs. Here, we find that PURs exceed 90 % in prepared foodstuffs for 16 EU members,

including the top exporters in this sector such as France, Italy and Spain. Average PUR across EU members

is also high for footwear and headgear, crossing 90 % for several EU members such as Germany, Denmark,

Slovakia and Hungary. Looking across all products, we find that members with high PUR (>75 %) are

Cyprus, Croatia, Greece, Sweden and Finland.

11

The Canadian government reports that in 2021, Canadian exports to the EU saw a 65.4% use of CETA preferences, which is a rise

of 13.4 pp from 2018. On the other hand, Canada's imports from the EU in 2021 had a CETA preference utilization rate of 59.5%,

marking a significant jump from the 38.4% rate in 2018. While not identical, these number are thus broadly in line with those

reported by Eurostat.

12

Note that in some sectors PUR see effectively no change or even decrease. The cause of this could be further investigated with

other methodologies, e.g., surveying firms, but goes beyond the scope of this in-depth analysis.

Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies

14

Figure 11: Heterogeneity in PUR across HS sections and EU countries

Note: This figure provides a heatmap for PURs across EU member states in their exports to Canada, disaggregated by HS

Sections. Data is from the latest year available (2021) and is drawn from Eurostat.

Figure 11 revealed that PURs differ substantially across EU countries and sectors. However, what is the PUR

for each member's top export sector? We examine this issue further in Figure 12. We note that PURs are

below 50 % i.e. more than half of the eligible exports are not availing the preferential terms, for the top

export sectors in 10 EU member states. These low PURs in key sectors for several EU members indicate

foregone cost savings and diminished welfare gains from the agreement.

Figure 12: PUR for top sectors across EU members

Note: This figure reports the PUR across EU members for their most important sector in terms of exports to Canada. Data on

PUR and on EU exports to Canada is drawn from Eurostat from 2021.

An analysis of the implementation of the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA)

15

As previously shown, exports to Canada are relatively concentrated amongst large firms for the majority of

EU members. How does this size distribution link to countries' PUR? We analyse this further in Figure 13.

Each panel in the figure shows the overall PUR for individual EU countries plotted against shares of their

exports to Canada that can be attributed to firms within a given size category. Comparing across panels,

we find that the greater is the share of the largest firms in a country's exports to Canada, the lower is the

country's overall PUR.

13

Figure 13: PUR across EU members by firm size

Note: Each panel in the figure above reports the PUR (vertical axis) and the share of EU members’ exports to Canada that

can be attributed to firms within a given size class (horizontal axis). Size classes are defined by the number of employees of

the firm. Both the horizontal and vertical axes are shown in log scale. Data on PUR and on EU exports to Canada

disaggregated by firm size categories is drawn from Eurostat from 2021 (or the latest available year in case of missing

values).

There may be multiple factors underpinning these results. First, small firms may be operating with narrower

margins and thus may be strongly incentivised to utilise any available tariff preferences. Differences in

input sourcing strategies across firms may also play a role in driving this pattern of PURs. Large firms, with

wider and more complex input bundles drawn from diverse suppliers, might be less inclined to meet Rules

of Origin (RoO) criteria and utilise tariff preferences. Meeting RoO might necessitate shifting established

supply chains and entail significant adjustment costs for these enterprises. Differences in preferential

margins and sectoral compositions may also matter. If large firms are clustered in industries with small

preferential margins, their PUR may be correspondingly low. A full investigation of these various channels

is beyond the scope of this analysis due to scarcity of data on PURs. However, Figure 14 does reveal that

PUR for EU exports to Canada are lower in industries with narrower preferential margins, suggesting that

the cost for meeting RoO may be higher than expected duty savings for firms in these sectors.

13

Note that due to data limitations, we cannot further disentangle the overall PUR of a country into the PURs for its firms belonging

to different size categories.

Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies

16

Figure 14: PUR and preferential margins

Note: This figure reports the PUR across EU members and weighted average preferential margins for the same sectors. Data

on PUR and on EU exports to Canada is drawn from Eurostat from 2021.

Finally, we examine the PUR for EU's aggregate goods exports across its various trade partners (Figure 15).

Here, we observe that older agreements like the Stabilization and Association Agreements (SAAs) with

Western Balkan nations (Serbia, North Macedonia, Montenegro, Albania, and Bosnia and Herzegovina)

exhibit higher PUR values. In contrast, CETA, being a newer pact, shows a relatively lower (57.80 %) yet

steadily increasing PUR (see Figure 10). When comparing with recent deep FTAs signed by the EU, we find

that CETA's PUR lags behind that of South Korea (78.41 %) and Japan (70.3 %) but surpasses that of

Singapore (33.65 %) and Vietnam (28.76 %).

Figure 15: PUR across EU FTA partners

Note: This figure reports the PUR across EU’s FTA partners and their respective shares in EU’s total exports to FTA partners.

Data on PUR and on EU exports to Canada is drawn from Eurostat from 2021.

An analysis of the implementation of the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA)

17

4.3 Trade and sustainable development

Chapter 22 of CETA addresses issues linked to trade and sustainable development (TSD). Broadly,

provisions under this chapter aim for trade and investment between the parties to contribute towards

meeting sustainable development goals. These include commitments to uphold labour rights, protect the

environment, including the fight against climate change, and engage with civil society. Both parties agree

to adhere to international agreements on these issues, such as the International Labour Organization (ILO)

conventions and multilateral environmental agreements.

Since the Agreement entered provisionally into force in 2017, the EU and Canada have jointly monitored

implementation and enforcement. The EU, Canada and the CETA Domestic Advisory Groups (DAGs) have

not identified any shortcomings in the implementation or in the compliance with the CETA TSD provisions.

A general evaluation of the impact of these provisions is difficult in the scope of this in-depth analysis.

However, some aspects have received more scrutiny than others. For example, critics argue that while CETA

mentions environmental sustainability, it lacks robust enforcement mechanisms. While the standards

introduced in the CETA are acknowledged by Heyl et al. (2021), the authors cast doubts on the strength of

the institutional frameworks and legal and dispute resolution systems, which are embedded in the trade

agreement to ensure compliance with provisions on environment. This raises concerns that businesses

might prioritise profits over environmental standards. Additionally, the increased trade resulting from

CETA could lead to more carbon emissions due to higher volumes of goods being transported between

Canada and the EU.

Figure 16: Evolution of EU environmental goods trade with Canada

(a) Evolution of EU environmental goods exports

to Canada

(b) Evolution of EU environmental goods imports from

Canada

Note: Data from the IMF’s database on environmental goods. Own visualization.

One way to approach an evaluation in the context of trade flows is to look at the data for relevant industries.

Figure 16 shows that overall trade in environmental goods appears to be largely unchanged since CETA's

provisional implementation.

14

14

The IMF's database on trade in environmental goods build on publicly available trade data from UN COMTRADE. Environmental

goods, as defined by the IMF in its database, comprise of connected goods and adapted goods. Connected goods are goods

directly linked to environment protection such as bins and trash bags. Adapted goods are those goods which used help

environment protection such as electric cars.

Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies

18

However, drilling down to a sectoral disaggregation, a compositional impact of CETA becomes clear. Figure

17 zooms in on changes in production of three particularly sensitive types of sectors in terms of environ-

mental concerns: extractive industries, forestry, as well as the meat and fishery industries. The figures,

drawn from the benchmark simulation described above, show that production has shifted between

participating partners. Most European economies have reduced their production in these sectors (on

average each by about 0.05 %), while Canada has increased its production in all three by up to 1.2 %.

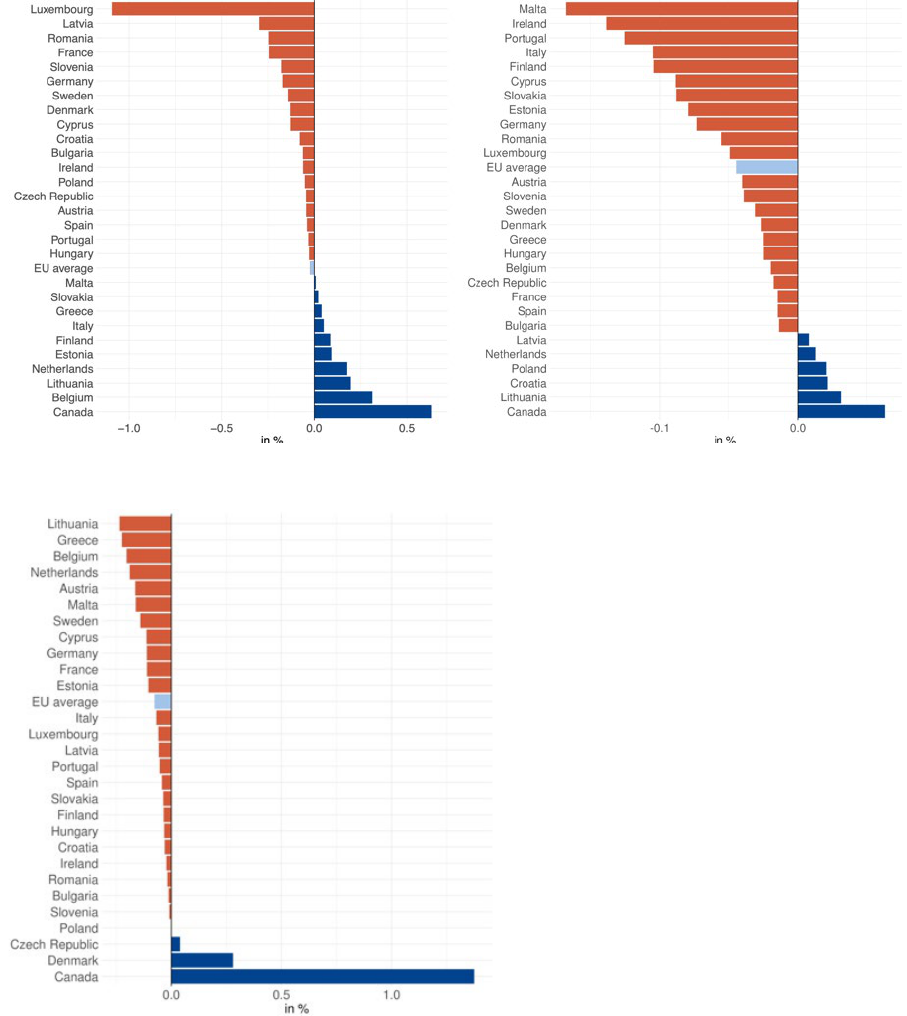

Figure 17: Change in production of environmentally sensitive sectors

(a) Extractive industries (b) Forestry

(c) Meat production

An analysis of the implementation of the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA)

19

4.4 Raw materials

The implementation of CETA is also important in view of the EU's concerns regarding access to critical raw

materials (CRM) that are vital for the bloc's industrial base and technological ambitions. By reducing key

trade barriers and facilitating regulatory cooperation, CETA can serve as yet another policy instrument to

diversify the EU's supply chains for these strategic inputs. This would also be in line with the EU's objectives

under the recently announced European Critical Raw Materials Act, which prioritises the diversification of

CRM supply sources.

Cooperation with Canada on CRMs extends beyond CETA as well. In June 2021, the EU inked its first-ever

Strategic Partnership on Raw Materials with Canada. This partnership aims to bolster collaboration on

research and innovation and improve conditions for trade and investments in the raw materials sector. In

doing so, both parties aim to foster the sustainable development and strategic use of base metals and

minerals, which are crucial to the EU's green and digital transitions. Table 2 displays the most recent list of

raw materials deemed critical and strategic by the EU commission.

Table 2: Critical raw materials

Category

Raw material

Critical

Strategic

Compounds

Baryte

X

Compounds

Coking Coal

X

Compounds

Feldspar

X

Compounds

Fluorspar

X

Compounds

Phosphate rock

X

Metals

Antimony

X

Metals

Arsenic

X

Metals

Bauxite

X

Metals

Beryllium

X

Metals

Bismuth

X

X

Metals

Cobalt

X

X

Metals

Copper

X

X

Metals

Gallium

X

X

Metals

Germanium

X

X

Metals

Hafnium

X

Metals

Heavy Rare Earth Elements

X

Metals

Light Rare Earth Elements

X

Metals

Lithium

X

X

Metals

Magnesium

X

X

Metals

Manganese

X

X

Metals

Nickel – battery grade

X

X

Metals

Niobium

X

Metals

Platinum Group Metals

X

X

Metals

Rare Earth Elements for magnets

X

X

(Nd, Pr, Tb, Dy, Gd, Sm, and Ce)

Metals

Scandium

X

Metals

Silicon metal

X

X

Metals

Strontium

X

Metals

Tantalum

X

Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies

20

Metals

Titanium metal

X

X

Metals

Tungsten

X

X

Metals

Vanadium

X

Metalloids

Boron

X

X

Non-Metals

Helium

X

Non-Metals

Natural Graphite

X

X

Non-Metals

Phosphorus

X

Note: See https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:903d35cc-c4a2-11ed-a05c-

01aa75ed71a1.0001.02/DOC_2&format=PDF for the latest list of strategic and critical raw materials. Own categorization.

In response to these policy initiatives, we utilise the KITE model to analyse a second scenario. This scenario

seeks to measure the impact of enhanced EU-Canada raw material cooperation under the framework of

CETA and the Strategic Partnership agreement, by reducing bilateral NTBs for the sectors that can be

directly linked to the list depicted in Table 2, namely ‘Other Mining Extraction (formerly omn)’. In the

simulation, we further reduce non-tariff barriers by 5 %, following related work by Borsky et al. (2018).

Overall, the results depicted in Figure 18 indicate that improved EU-Canada cooperation on raw materials

has a predominantly positive – albeit small – impact on welfare changes across EU member states. Along

the sectoral dimension, we find that industries using these materials as inputs (such as chemical products,

but also the transportation industry) see small but significant growth in production. Conversely, certain

sectors like oil, gas, and other extractive domestic industries experience a decline in production.

Importantly, the results show that production in the EU of the affected sectors would shrink by about

0.05 %. The results should be interpreted with caution, however, as reductions in trade barriers for these

critical and strategic goods with strategic partners, such as Canada, are likely to go hand in hand with

measures that also facilitate the domestic production of the materials in question.

15

Figure 18: Impact of strategic partnership on raw materials

(a) Welfare effects for EU member states (b) Total EU production change in select industries

15

See e.g. the EU Critical Raw Materials Act (https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_23_1661), which

emphasizes domestic capacities for critical raw materials.

An analysis of the implementation of the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA)

21

4.5 Mutual recognition of standards and qualifications

CETA includes substantive provisions on the mutual recognition of standards and qualifications. By

reducing the costs associated with conformity assessment and compliance, these provisions can lower key

barriers to trade in goods and services.

In the case of goods, a major milestone has been the signing of the Mutual Recognition Agreement (MRA)

between the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) and the EU Taxation and Customs Union (TAXUD) in

2022. Through this agreement, both agencies mutually recognise and validate the safety and security

standards that underpin each other's Trusted Trader Programs. The MRA thus paves the way for faster

border clearances for certified businesses in the EU and Canada that adhere to these standards. Beyond

the immediate advantages of reducing time delays and administrative costs, the MRA could also bolster

the resilience and security of supply chains between the EU and Canada.

CETA also features provisions concerning regulatory cooperation in services. For instance, Chapter 11 of

the agreement provides a general framework for future negotiations on MRAs between the EU and Canada

on professional qualifications. It prompts both parties to encourage their respective professional bodies

and relevant authorities to jointly recommend and negotiate on potential MRAs. Proposed MRAs are then

developed and adopted by a Joint Committee before being integrated into CETA. The design of this

chapter reflects the fact that the regulation of professional qualifications is managed independently by

individual member states in the EU and by distinct provinces within Canada.

Given the heterogeneity in qualification, licensing, and certification systems across signatory countries,

MRAs can substantially lower conformity assessment costs for workers by acknowledging that training

programs provide comparable levels of knowledge and skills. In doing so, they promote trade in services

and the cross-border mobility of professionals.

Notable progress has already been made in this area with the finalisation of the negotiations on a MRA for

architects between EU and Canada in 2022 and 2023, with the EU being ready to enact it as of October

2023.

16

The successful implementation of this MRA may further catalyse negotiations for additional MRAs

for other regulated professions such as in healthcare. To assess the economic implications of such

prospective MRAs, we exploit the KITE model and simulate a reduction in red-tape barriers across multiple

services sectors encompassing these professions. Specifically, we simulate the effect of reducing frictions

by – again – 5 % for services sectors, following the related literature (see e.g. Kox et al., 2005).

17

Note that

the general equilibrium simulation allows for an adjustment of other sectors that are not directly affected

to see a change in wages, production, etc. Directly affected sectors may be an important input in indirectly

affected sectors, and wage differentials may affected third sectors as well.

16

Compare Council Decision 2023/2467 (https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=OJ:L_202302467).

17

Specifically, in this simulation we lower NTBs beyond those due to the implementation of CETA for the following sectors:

Construction, Education, Human health and social work activities, Insurance, as well as business services and financial services.

Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies

22

Figure 19: Impact of mutual recognition of qualifications

(a) Welfare effects for EU member states (b) Total EU production change in select industries

Results are reported in Figure 19. The KITE model predicts that the removal of red-tape barriers for the

service sectors leads to overall – albeit small – welfare gains for all member states. In particular, Ireland,

Luxembourg, Malta and Cyprus would profit the most from such a procedure. For the remaining member

states, welfare gains would be much more attenuated. For some countries such as Lithuania, Slovakia, and

France there would hardly be a quantifiable effect.

The composition of total EU production would experience a slight tilt in favour of service-oriented sectors.

Insurance, financial and business services would gain about 0.03 %, 0.015 % and 0.007 % production share,

respectively. The educational sector would also experience an increase in total production share, albeit at

a lower level. The growth in service production share mostly seems to arise at the expense of the extractive

sectors, predominately the oil and gas sector. Given the strong financial service sector orientation in

Ireland, Luxembourg, Malta and Cyprus, it may hardly be surprising that these countries would profit the

most from the compositional changes, as reflected in their respective welfare changes.

5 Conclusions and recommendations

Since its provisional enforcement six years ago, CETA has established stronger trade ties between the EU

and Canada. Our quantitative analysis shows that it has delivered substantial economic gains, with goods

exports from the EU to Canada rising by 27 % and goods imports by 32 %. CETA has also benefited the

services sector, increasing the EU's exports to and imports from Canada in services by 19 % and 15 %,

respectively.

However, there are areas where CETA's implementation needs to be strengthened. In particular, the

relatively low PUR in several EU countries and amongst large firms requires further investigation and policy

action. Moreover, despite dedicated SME provisions, CETA has not substantially altered the firm size

composition of EU's exports to Canada. Here, we note that SMEs continue to capture roughly 40 % of the

bloc's total exports to Canada, even as they account for more than 75 % of firms exporting to Canada.

Addressing this skewness requires deeper investigation of specific SME experiences and constraints in

Canada.

However, CETA holds relevance beyond its immediate economic effects. The agreement's focus on

regulatory cooperation provides a framework for the EU and Canada to collaborate on and design common

An analysis of the implementation of the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA)

23

standards for new and emerging industries. Moreover, in a period of escalating geopolitical uncertainties,

the agreement offers a valuable platform for both the EU and Canada to bolster and diversify their supply

chains.

The in-depth analysis underlines that modern trade and integration agreements by the EU with other

developed economies provide strong impulses for growth in trade and by extension increase in welfare.

While some of the economic outcomes have heterogeneous effects, with differential average welfare

impacts across countries due to their industrial structure, and across sectors due to differences, e.g., in their

composition in terms of firm size, the analysis of the impact of the implementation of CETA shows that

economic integration with partner countries of similar levels of development allows both sides to reap the

mutual benefits derived from openness to trade.

The implementation of CETA serves as a testament to the advantages that can be realized through

reducing trade barriers and fostering a more cooperative economic environment. The agreement is

designed to facilitate easier access to markets, which leads to an increase in trade volume, better

investment opportunities, and a broader range of products and services available to consumers.

Additionally, after a full implementation of the agreement following ratification of all member states, the

enhanced regulatory cooperation and standards harmonization under CETA can further reduce costs and

improve the competitiveness of firms, thereby contributing to economic growth and welfare

improvements in both the EU and Canada. The in-depth analysis also highlights a number of key challenges

– from trade and sustainable development to partnerships for strategic raw materials – that, when

overcome, can unleash additional economic potential and contribute to strengthening the European

Union’s industrial base and technological ambitions.

Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies

24

References

[1] Anderson, J. E., Larch, M. and Yotov, Y. V. On the impact of CETA: Trade and investment. In: wiiw Seminar

in International Economics, Wien, volume 17, 2016.

[2] Breuss, F., A macroeconomic model of CETA’S impact on Austria. Technical report, WIFO Working

Papers, 2017.

[3] Finbow, R., Implementing CETA: A preliminary report. EU-Canada Network Policy Brief, 2019.

[4] International Monetary Fund. World economic outlook: War sets back the global recovery. Tech. rep.,

Washington, DC, April 2022

[6] Fontagné, L., Guimbard, H. and Orefice, G., Tariff-based product-level trade elasticities. Journal of

International Economics, 137: 103593, 2022.

[7] Kox, H. and Lejour, A. M., Regulatory heterogeneity as obstacle for international services trade, CPB

Discussion Paper 49. Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis, The Hague, The Netherlands,

2005.

[8] Chowdhry, S., Felbermayr, G. J., Hinz, J., Kamin, K., Jacobs, A.-K. and Mahlkow, H., The economic costs

of war by other means. Technical report, Kiel Policy Brief 147, 2020.

[9] Caliendo, L. and Parro, F., Estimates of the Trade and Welfare Effects of NAFTA. Review of Economic

Studies, 82(1), pp. 1–44, 2015.

[10] Aguiar, A., Chepeliev, M., Corong, E., McDougall, R. and van der Mensbrugghe, D., The GTAP data

base: Version 10. Journal of Global Economic Analysis, 4(1): 1–27, June 2019. ISSN 2377-2999.

[11] Head, K. and Mayer, T., Gravity equations: Workhorse, toolkit, and cookbook. In: Handbook of

international economics, volume 4, pp. 131–195. Elsevier, 2014.

[12] Puccio, L. and Binder. K., Trade and sustainable development chapters in CETA. Technical report,

European Parliament, 2017.

[14] Heyl, K., Ekardt, F., Roos, P., Stubenrauch, J. and Garske, B., Free trade, environment, agriculture, and

plurilateral treaties: The ambivalent example of Mercosur, CETA, and the EU-Vietnam free trade

agreement. Sustainability, 13: 3153, 2021.

[15] Borsky, S., Leiter, A. and Pfaffermayr, M., Product quality and sustainability: The effect of international

environmental agreements on bilateral trade. The World Economy, 41(11): 3098–3129, 2018.

[16] Aichele, R., Felbermayr, G. J. and Heiland, I., Going deep: The trade and welfare effects of TTIP, CESifo

Working Paper Series No. 5150. Available at SSRN 2550180, 2014.

[17] Hinz, J. and Monastyrenko, E., Bearing the cost of politics: consumer prices and welfare in Russia,

Journal of International Economics, 137: 103581, 2022.

[18] Eaton, J. and Kortum, S., Technology, Geography, and Trade. Econometrica, 70(5): 1741–1779, 2002.

[19] Dekle, R., Eaton, J. and Kortum, S., Global rebalancing with gravity: Measuring the burden of

adjustment. IMF Economic Review, 55(3): pp. 511–540, 2008.

An analysis of the implementation of the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA)

25

A. Technical description of the KITE Model

The KITE model builds on Caliendo and Parro (2015) and its implementation is similar to that of Aichele et

al. (2014) and Hinz and Monastyrenko (2022). There are N countries, indexed o and d, and J sectors, indexed

j and k. Production uses labour as the sole factor, which is mobile across sectors but not across countries.

All markets are perfectly competitive. Sectors are either wholly tradable or non-tradable.

There are L

d

representative households in each country that maximise their utility by consuming final

goods

in the familiar Cobb-Douglas form

where

is the constant consumption share on industries j’s goods. Household income

is derived from

the supply of labor

at wage

and a lump-sum transfers of tariff revenues. Intermediate goods

[

0,1

]

are produced in each sector j using labour and composite intermediate goods from all sectors. Let

[0,1] denote the cost share of labour and

[0,1] with

,

= 1 the share of sector k in sector

j's intermediate, such that

where

is the overall efficiency of a producer,

is labor input, and

,

represent the

composite intermediate goods from sector k used to produce

. With constant returns to scale and

perfectly competitive markets, unit cost are

where

is the price of a composite intermediate good from sector , and the constant

=

,

,

,

,

,

. Hence, the cost of the input bundle depends on wages and

the prices of all composite intermediate goods in the economy. Producers of composite intermediate

goods supply

at minimum costs by purchasing intermediate goods

from the lowest cost supplier

across countries, so that

> 0 is the elasticity of substitution across intermediate goods within sector , and

the demand

for intermediate goods

from the lowest cost supplier such that

Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies

26

where

is the unit price of the composite intermediate good

and

denotes the lowest price of intermediate good

in d across all possible origin locations,

(1)

Composite intermediate goods are used in the production of intermediate goods

and as the final good

in consumption as

, so that the market clearing condition is written as

(2)

Trade in goods is costly, such that the offered price of

from o in d is given by

(3)

where

denote generic bilateral sector-specific trade frictions. These can take a variety of forms – e.g.

tariffs, non-tariff barriers, but also sanctions. In that case we can specify

where

1 represent sector-specific ad-valorem tariffs and

1 other iceberg trade costs. Tariff

revenue

1

is collected by the importing country and transferred lump-sum to its households.

Ricardian comparative advantage is induced à la Eaton and Kortum (2002) through a country-specific

idiosyncratic productivity draw

from a Fréchet distribution.

18

The price of the composite good is then given as

(4)

which, for the non-tradable sector towards all non-domestic sources collapses to

(5)

where

=

/

with

being a Gamma function evaluated at

= 1 +

. Total

expenditures on goods from sector in country are given by

=

. The expenditure on those

18

The productivity distribution is characterized by a location parameter

that varies by country and sector inducing absolute

advantage, and a shape parameter

that varies by sector determining comparative advantage.

An analysis of the implementation of the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA)

27

goods originating from country is called

, such that the share of j from in is

=

. This

share can also be expressed as

(6)

Total expenditures on goods from sector are the sum of the firms’ and households’ expenditures on the

composite intermediate good, either as input to production or for final consumption

(7)

with

=

+

+

, i.e., labor income, tariff revenue and the aggregate trade balance. Sectoral

trade balance is simply the difference between imports and exports

(8)

and the aggregate trade balance

=

,

= 0, with

being exogenously determined. The

total trade balance can then be expressed as

(9)

A counterfactual general equilibrium for alternative trade costs in the form of

=

19

can be

solved for in changes following Dekle et al. (2008).

19

I.e. where any variable denotes the relative change from a previous value a new one .

PE 754.440

EP/EXPO/INTA/FWC/2019-01/LOT5/1/C/20

Print ISBN 978-92-848-1436-7 | doi: 10.2861/55940 | QA-02-23-306-EN-C

PDF ISBN 978-92-848-1435-0 | doi: 10.2861/652051 | QA-02-23-306-EN-N