Ally Bank

Community Reinvestment Act

Strategic Plan

January 1, 2023 – December 31, 2026

Table of Contents

SECTION I. INTRODUCTION 1

A.

Ally Bank Product Offerings and Business Strategy

1

B.

Ally Bank Financial Information

2

SECTION II. CRA STRATEGIC PLAN PROPOSAL 2

A.

Ally Bank’s Commitment to CRA

2

B. Overview of Strategic Plan, Effective Date and Term 2

S

ECTION

I

I

I.

ASSESSMENT AREA

3

A. Median Family Income and Population Data 3

B.

Housing Data

5

C. Economic Outlook and Other Relevant Data 8

SECTION IV. NEEDS AND OPPORTUNITES IN THE ASSESSMENT AREA 11

A.

Needs

in the

Assessment

Area

11

B. Opportunities in the Assessment Area 14

SECTION V. PUBLIC PARTICIPATION 17

A.

Informal Public

Suggestions

17

B. Formal Public Comment Solicitation 17

SECTION VI. ALLY BANK STRATEGIC PLAN and MEASURABLE GOALS 18

A.

Definitions

18

B. Framework and Methodology 19

C.

Measurable Goals for “Outstanding”

24

D. Measurable Goals for “Satisfactory” 25

E.

Strategic Plan Ratings System and Alternate Evaluation Method

2

7

SECTION V

I

I.

REQUEST FOR APPROVAL AND CONTACT INFORMATION

28

A. Regulatory Criteria for Approval 28

B.

Request for Approval of Ally Bank CRA Strategic

Plan 2023

–

202

6

28

C. Contact Information 28

APPENDICES 29

Appendix

1:

Ally

Bank Products, Deposits, Awards, and Financial Information

30

Appendix 2: Map of Assessment Area and Census Tracts 32

Appendix 3: Additional

Demographic Information

35

Appendix 4: Additional Needs Assessment Information 41

Appendix

5

:

Map of Broader Statewide or Regional Area

42

Appendix 6: Proof of Publication of Request for Public Comment 43

CONFIDENTIAL EXHIBITS (Bound Under Separate Cover)

Confidential Exhibit A: Financial Information

Confidential Exhibit B: Bases for Measurable Goals

Confidential Exhibit C: Analysis of CRA Performance of Peer Banks

1

SECTION I. INTRODUCTION

Ally Bank (or “Bank”) is a Utah state-chartered commercial bank established in August 2004 that maintains its

headquarters in Sandy, Utah. The Bank is an indirect wholly-owned subsidiary of Ally Financial Inc.

1

(“AFI” and,

collectively with Ally Bank, “Ally”) and is regulated at the federal level by the Board of Governors of the Federal

Reserve System (“Federal Reserve Board”) acting through the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago (“Chicago FRB”).

At the state level, the Bank is regulated by the Utah Department of Financial Institutions (“UDFI”). As a federally

insured depository institution, Ally Bank is subject to the Community Reinvestment Act (“CRA”),

2

which requires

banks to help meet the credit needs of their entire community, including low- and moderate-income

neighborhoods. In light of Ally Bank’s nationwide direct business model and lack of branches, the Bank has

elected to be evaluated under the “strategic plan” performance test as provided in 12 C.F.R. §228.27. The Bank

has prepared this new CRA Strategic Plan for 2023-2026 (“this Strategic Plan” or “2023-2026 Plan”) to replace the

Bank’s current CRA Strategic Plan for 2020-2022 (“2020-2022 Plan”) that expires on December 31, 2022.

3

A. Ally Bank Product Offerings and Business Strategy

Ally Bank is a leading online bank that offers banking products and services nationwide with no branches or

ATMs.

4

Ally Bank offers deposit and loan products to consumers, including automotive vehicle financing,

mortgage financing through Ally Home, point of sale personal consumer loans through Ally Lending, consumer

credit cards through Ally Credit Card (securities-brokerage and investment-advisory services are offered through

Ally Invest, an Ally Bank affiliate). Ally Bank’s premier online deposit business offers a full spectrum of deposit

and other banking products, including savings, money-market and checking accounts, certificates of deposit, and

individual retirement accounts.

Ally Bank is a leading provider of auto finance and leasing products, and provides several financing solutions for

more than 20,000 automotive dealerships (including wholesale and dealer floorplan loans, real estate loans, and

working capital loans), and purchases new and used consumer and small business retail installment sale contracts

and leases. Ally Bank’s corporate finance business offers financing for equity sponsors and middle-market

companies. The Bank also manages a growing community development loan portfolio. See Appendix 1.A for Ally

Bank’s current product offerings.

Ally Bank is a customer-centric company with passionate customer service and innovative financial solutions. We

are relentlessly focused on “Doing it Right” and being a trusted financial-services provider to our consumer,

commercial, and corporate customers. The June 2021 elimination of overdraft fees on all Ally deposit accounts

demonstrates Ally’s passionate focus on “doing right” by its customers, especially those who may be financially

vulnerable or living paycheck-to-paycheck. The Bank’s ongoing strategy is designed to nurture long-term

customer relationships and capitalize on the shift in consumer preference to direct banking. Ally Bank’s

relentless focus on providing a superior customer experience has resulted in numerous awards, including “Best

Online Bank for Low Fees” from Money Magazine, and several other “Best Online Bank” awards from industry

and consumer publications.

5

Consistent with the accelerating industry trend toward digitally-based financial

services, Ally Bank will continue its direct banking business model and will focus on strengthening and expanding

existing relationships with its auto and deposit customers, in addition to attracting new customers with an

expanded suite of consumer products.

1

AFI is a leading digital financial services company that offers a wide range of financial products and services.

2

Codified at 12 U.S.C. §2901 et seq.

3

This Strategic Plan will have been submitted for approval shortly after the August 5, 2022, due date for public comments on the three federal banking agencies’ Notice of

Proposed Rulemaking regarding the Community Reinvestment Act published on May 5, 2022 (“May 2022 NPR”) 78 Fed. Reg. 33884 (proposed, June 3, 2022, but before the

issuance of any final rule. It is the Bank’s understanding that under applicable provisions in the NPR, and subject to the final rules, this Strategic Plan when approved would

remain in effect under the current CRA regulations until the expiration date of December 31, 2026.

4

In addition to the Bank’s headquarters in Sandy, Utah, Ally has primary operations in Detroit, Michigan; Charlotte, North Carolina; Fort Washington, Pennsylvania; New York,

New York; and Lewisville, Texas.

5

See Appendix 1.B for additional awards.

2

B. Ally Bank Financial Information

Ally Bank is profitable, growing, and well-capitalized. As of March 31, 2022, Ally Bank had $174.5 billion in total

assets, $145.2 billion in total deposits, $15.6 billion of total equity capital, and 9,515 full-time employees.

Additional financial information, including a link to the Bank’s Consolidated Reports of Condition and Income (Call

Report) as of March 31, 2022, are included at Appendix 1.C.

SECTION II. CRA STRATEGIC PLAN PROPOSAL

A. Ally Bank’s Commitment to CRA

Ally Bank embraces its obligations under the CRA as an extension of its strong LEAD

6

corporate culture of being

an “Ally” to its customers and communities and has devoted significant effort to complying with both the letter

and the spirit of the CRA. Ally Bank’s Board of Directors (“Ally Bank Board”) and senior management are deeply

committed to achieving meaningful impact in its communities. To this end, Ally Bank has established a

comprehensive CRA Program that involves participation from the Ally Bank Board, senior management, the

Bank’s CRA Department, and other Bank employees.

Ally Bank’s CRA Program is under the direction of the Ally Bank Board, with a Bank-wide management CRA

Committee comprised of members of senior management from the Business Lines, Finance, Risk, Compliance,

Corporate Communications, and Treasury. The CRA Committee is responsible for oversight of the Bank’s CRA

activities, the CRA Portfolio, and the Bank’s approved CRA Strategic Plan,

7

with designated senior managers

responsible for management of the Bank’s Community Development (“CD”) transaction approval process.

Ally Bank has demonstrated its ongoing commitment to CRA by building a strong CRA Department that consists of

individuals with extensive experience in the banking industry, particularly in the areas of affordable housing,

community development finance, community services, and legal and regulatory compliance. The Bank’s CRA

Officer is charged with overseeing the development and implementation of the Bank’s CRA Strategic Plan,

coordinating all CRA activities, and reporting to the CRA Committee and the Ally Bank Board on a regular basis.

The Bank’s CRA Department has developed deep ties in the community, and remains actively engaged with

community members, with an emphasis on finding and developing new or expanded ways to help meet

community needs in a safe and sound manner. The CRA Department performs extensive due diligence regarding

all proposed CRA loans and investments, and approvals follow the Enterprise Delegated Lending Authority and

the Bank’s CRA Policy. Ally Bank received an “Outstanding” CRA rating on its most recent CRA Performance

Evaluation, dated September 28, 2020.

8

B. Overview of Strategic Plan, Effective Date and Term

Ally Bank’s strong commitment to CRA is further evidenced by the extent and breadth of its measurable goals set

forth in this Strategic Plan: Ally Bank will make $5.4 billion in loans and investments over the four-year plan

period and will provide 3,300 volunteer hours of CD services to earn an “Outstanding” CRA rating. The overall

$5.4 billion goal amount is an increase from the 2020-2022 Plan’s $3.7 billion goal for “Outstanding.” The $5.4

billion goal amount is comprised of CRA-qualifying loans and CD investments, with annual interim goals, and also

contains specific assessment area goals for auto loans, mortgage loans, and CD loans/investments. This

considerable volume of CRA-qualifying loans and CD investments will allow the Bank to be even more responsive

to critical community needs and implement responsive, flexible, and innovative loans and investments. In

developing this 2023-2026 Plan and its proposed goals, the Bank sought and received input from numerous

6

Ally’s LEAD values include “Look Externally,” “Execute with Excellence,” “Act with Professionalism,” and “Deliver Results.”

7

The CRA Committee also has responsibility to review and approve the proposed CRA Strategic Plan and then make a recommendation for approval to the Ally Bank Board.

8

The Performance Evaluation can be accessed at: https://www.federalreserve.gov/apps/CRAPubWeb/CRA/BankRating.

3

entities representing a wide array of community partners as specified in Sections IV and V below. The goals are

set forth and described in greater detail in Section VI below.

The effective date of this Strategic Plan is January 1, 2023, and the term is four years: 2023-2026.

If during the term of this Strategic Plan there is a material change in circumstance, Ally Bank may request an

amendment to this Strategic Plan as provided for in 12 C.F.R. §228.27(h).

SECTION III. ASSESSMENT AREA

The Federal Reserve Board’s regulation implementing the CRA requires a bank to delineate one or more

assessment areas within which the bank’s record of helping to meet the credit needs of its community will be

examined. The assessment area must include the geographies in which the bank has its main office, its branches,

and its deposit-taking ATMs (12 C.F.R. §228.41(c)(2)). Because Ally Bank operates no physical branches or

deposit-taking ATMs, the Bank delineates its assessment area based on its Sandy, Utah headquarters located in

Salt Lake County. The Bank’s CRA assessment area in Utah (“UTAA”) includes Salt Lake County and seven

surrounding counties: Davis, Morgan, Summit, Tooele, Utah, Wasatch, and Weber (see map at Appendix 2.A). In

compliance with 12 C.F.R. §228.41(c) – (e), the UTAA includes only whole geographies or political subdivisions

(counties), does not reflect illegal discrimination, and does not arbitrarily exclude low- or moderate-income

(“LMI”) geographies. Ally Bank continues its efforts to expand CRA activities to more rural areas of Utah,

including three counties – Morgan, Summit and Wasatch – which were added to the Bank’s UTAA in 2017. These

rural areas often have lower median family incomes and do not receive as much benefit from CRA activities as

the more metropolitan areas such as Salt Lake County (see Table 1 below).

9

A. Population Data and Median Family Income

Data from the 2020 census indicates that Utah was the fastest-growing state in the nation over the past decade

with a population growth of 18.4%.

10

This growth shows no signs of slowing in the next decade, driven by both

net migration to Utah associated with economic factors discussed in Section C below and by the state having one

of the highest fertility rates in the nation of 1.92 births per woman versus the US average of 1.64.

11

The Bank’s UTAA contains a 2021 population of approximately 2.67 million (Table 1). This number has increased

5% since the 2018 data covered in Ally’s 2020-2022 strategic plan. Salt Lake is the most populous county,

surpassing 1.18 million people in 2021 and accounting for 35% of the state’s population.

12

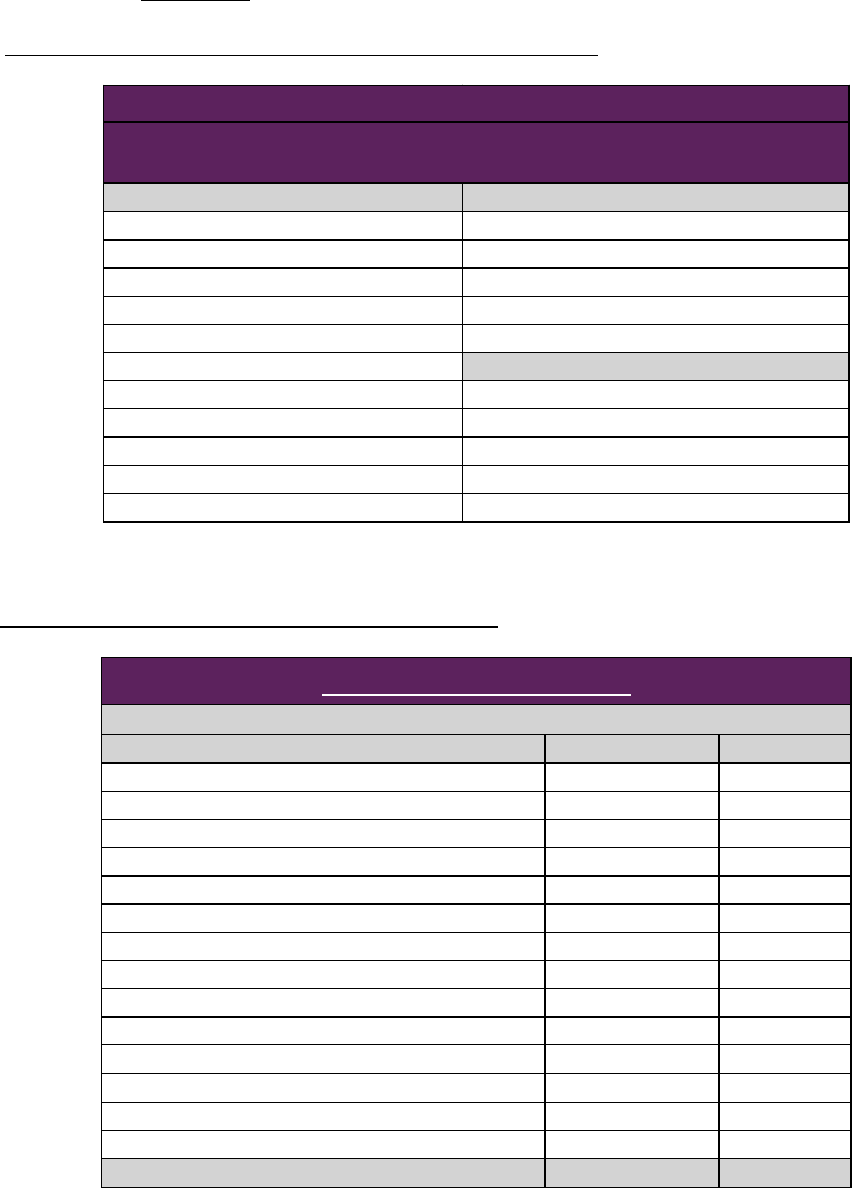

Table 1: UTAA Population Data

9

Summit and Wasatch Counties are the location of several ski and summer resorts (such as Park City and Deer Valley) but have such a shortage of affordable housing that most

resort employees cannot afford to live near their work and must commute from long distances. Ally Bank has financed affordable rental workforce housing to help meet the

needs of LMI individuals who work in Summit and Wasatch Counties.

10

https://www.usnews.com/news/best-states/utah/articles/2021-04-26/utah-has-fastest-growing-population-2020-census-shows

11

https://www.deseret.com/2022/3/20/22965720/utah-fertility-rate-drops-reframe-conversation-children-public-good-private-responsibility

12

Population data used herein is from the United States Census Bureau Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Counties: April 1, 2020 to July 1,

2021 at https://www.census.gov/data/datasets/time-series/demo/popest/2020s-counties-total.html.

County 2020 Population 2021 Est. Population

Davis 362,679 367,285

Morgan 12,295 12,657

Salt Lake 1,185,238 1,186,421

Summit 42,357 43,093

Tooele 72,698 76,640

Utah 659,399 684,986

Wasatch 34,788 36,173

Weber 262,223 267,066

AA Total 2,631,677 2,674,321

State of Utah Total 3,271,616 3,337,975

Ally Bank Assessment Area Population

Source: U.S. Census Bureau; FFIEC

4

In addition to growing, the state’s population is also diversifying. As of 2019, Utah was the 34

th

most racially and

ethnically diverse state in the nation, with 78% of the state identifying as non-Hispanic White and 22% of the

population identifying as another race (compared to a national average of 40% non-white). Hispanic/Latino

persons were 14% of the population and 1.2% of the population were African-American. The population of

diverse Utahans is expected to increase to 35% by the year 2060 with 22% of the population forecasted to be

Hispanic, 5% multi-racial, 4% Asian,2% African-American, and 2% Native American/Alaskan/Hawaiian. Since

2010, non-white racial and ethnic minority populations accounted for about 40% of Utah’s population increase

(Appendix 3-F, p. 9).

Poverty disproportionately impacts racial minorities in Utah with Native American adults (16%) and children

(27%) experiencing the highest rates of intergenerational poverty in 2020 compared to 2% of white adults and 2%

of white children (Appendix 3-E, p. 16). However, poverty rates are consistently lower in Utah than the United

States, with an estimated 12.3% of persons living in poverty in the United States in 2020 compared to 8.9% of

Utahans (Appendix 3-E, p. 7).

Several of the zip codes with the highest counts of individuals in intergenerational poverty are located within

Ally’s UTAA (Appendix 3-E, page 22). Ogden, located in Weber County, has the highest count of adults and

children in intergenerational poverty in the state.

There are currently 576 census tracts comprising Ally’s UTAA. The income breakdown of these census tracts is

set forth in Table 2. This Table reflects an overall increase of 100 census tracts from the 476 census tracts

reflected in Ally Bank’s 2020-2022, with a decrease of six low-income census tracts, an increase of 13 moderate-

income census tracts, and a decreased percentage of combined LMI census tracts from 25% of total tracts to 22%.

Table 2: UTAA Census Tract Demographics

All of the counties in the UTAA are included in the Salt Lake City-Provo-Orem Combined Statistical Area (“CSA”) as

defined by the Office of Management and Budget. Both Wasatch and Summit Counties are designated as non-

metropolitan areas and contain some of the more rural areas in Utah. The data in the charts below was collected

from the most recently available data as published online by the FFIEC and the U.S. Census Bureau. The 2021

income data by county, as reported by the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (“FFIEC”), is set

forth in Table 3.

County

Name

# of Low-

Income

Tracts

# of

Moderate-

Income

Tracts

# of Middle-

Income

Tracts

# of Upper-

Income

Tracts

Unknown

Tracts

Total # of

Census

Tracts

Davis 0 8 33 25 0 66

Morgan 0 0 3 1 0 4

Salt Lake 5 56 115 71 4 251

Summit 0 0 4 10 0 14

Tooele 1 6 8 1 1 17

Utah 9 24 76 43 4 156

Wasatch 0 0 2 7 1 10

Weber 2 15 34 7 0 58

TOTALS 17 109 275 165 10 576

% of Total 3.0% 18.9% 47.7% 28.6% 1.7% 100.0%

Source: FFIEC last updated 04/19/2022 (preliminary)

UTAA Census Tract Demographics

5

Table 3: UTAA Median Family Income Data

Approximately 15% of Utahans received at least one month of public assistance in 2020. Of these, 33% were

adults between 21 and 50 years of age, and 41% were children ages 0-17 (Appendix 3-E, p. 11). Data indicates

that in 2020, there were almost 195,000 children in Utah (21%) at risk of remaining in poverty as adults. One

item which helps families break out of the cycle of poverty is access to stable, affordable housing.

B. Housing Data

Utah’s nation-leading population growth has exacerbated the already existing affordable housing crisis in the

state, for both homeowners and renters, as the state’s housing supply is insufficient to meet demand. This is

especially true within the UTAA, with housing unit supply data for each county in the UTAA set forth in Table 4

below.

Table 4: UTAA Housing Data

In an effort to keep up with demand, residential construction value totaled $7.7 billion in 2021, a 12.8% increase

over the prior year. Permits for residential construction totaled 35,500 in 2021, compared to 32,237 in 2020. Of

County

Combined

Statistical Area

Code

Metropolitan

Statistical Area

Code

2021 FFIEC

Est. MSA/MD

non-MSA/MD

Median

Family

Income

("MFI")

Low Income

<50% of MFI

or below

Moderate Income

50% to <80% of MFI

Middle Income 80%

to <120% of MFI

Upper Income

120% MFI or

above

Salt Lake 482 41620 $91,700 $0 - $45,849 $45,850 - $73,359 $73,360 - $110,039 $110,040

Tooele 482 41620 $91,700 $0 - $45,849 $45,850 - $73,359 $73,360 - $110,039 $110,040

Davis 482 36260 $89,400 $0 - $44,699 $44,700 - $71,519 $71,520 - $107,279 $107,280

Weber 482 36260 $89,400 $0 - $44,699 $44,700 - $71,519 $71,520 - $107,279 $107,280

Morgan 482 36260 $89,400 $0 - $44,699 $44,700 - $71,519 $71,520 - $107,279 $107,280

Utah 482 39340 $83,700 $0 - $41,849 $41,850 - $66,959 $66,960 - $100,439 $100,440

Summit 482 99999 $74,100 $0 - $37,049 $37,050 - $59,279 $59,280 - $88,919 $88,920

Wasatch 482 99999 $74,100 $0 - $37,049 $37,050 - $59,279 $59,280 - $88,919 $88,920

UTAA Median Family Income Data

Source: FFIEC last updated 7/14/21

County

Total # of

Housing

Units

Total # of 1-

4- Family

Units

% of

Occupied 1-

to 4-Family

Units

% of

Owner

Occupied

Units

% of

Vacant

Units

% Renter

Occupied

Salt Lake 372,990 297,442 75% 62% 6% 32%

Tooele 20,148 18,948 76% 71% 8% 21%

Davis 101,756 92,214 81% 74% 4% 22%

Weber 87,515 76,706 73% 65% 8% 26%

Morgan 6,400 6,360 79% 79% 6% 16%

Utah 155,425 136,128 71% 64% 4% 32%

Summit 27,083 20,640 49% 38% 49% 13%

Wasatch 22,704 21,040 56% 52% 29% 19%

Source: FFIEC, last modified 4/22/2022

UTAA Housing Data

6

this, 12,000 permits were for apartment units resulting in a 3

rd

consecutive year where multi-family permits

exceeded single family permits (though only the fifth time in the state’s recorded history that multi-family

permits outnumbered single family) (Appendix 3-A, p. 157). The majority of this activity has been concentrated in

the Salt Lake City area. Building permits were granted for 34,500 apartment units in Salt Lake County between

2011-2021, three times the 11,600 units permitted between 2000 and 2010 (Appendix 3-B, p. 1).

Because demand for housing units has outpaced supply, data from the Federal Housing Finance Agency reported

by the Gardner Policy Institute at the University of Utah (“Gardner Institute”) notes that the Salt Lake City

metropolitan statistical area (“MSA”) has experienced the third largest housing price increases over the past five

years of any top 100 metropolitan area, behind only Boise and Tacoma. Between the second quarter 2016 and

second quarter 2021, Salt Lake MSA single family housing prices increased by 79%, an average of 12.3% per year.

Rental rates increased by 37% over that same period, an average annual increase of 6.5% (Appendix 3-B, p. 2).

The Gardner Institute reports as of December 2020, the state’s median housing price was $380,000, making

home ownership unaffordable for 48.5% of households in the state. Additional price increases through 2Q 2021

pushed the unaffordability percentage above 50% (Appendix 3-C, p. 1). The graph below shows the steady rise of

home prices since 2013, including a 28.3% spike in the second quarter of 2021 as COVID migrations drew

additional people to the area (Appendix 3-C, p. 3).

The state’s major urban markets have been especially hard hit. As of February 2022, Ogden is the 3

rd

most

overpriced housing market in the nation with a 61.25% premium. Provo is ranked 7

th

with a 53.66% premium and

Salt Lake City is ranked 9

th

with a 52.3% premium.

13

Gardner Institute experts note that pricing increases have

occurred for a record six continuous years, with double-digit increases in some years, and describe the resulting

impact on pricing of single-family homes and condos as “perilous territory”.

14

There is little indication that the challenges to single-family housing affordability will stop soon. Realtor.com’s

2022 Housing Forecast ranked Salt Lake City as the nation’s top housing market for the year, projecting 23.7%

increases in sales and prices for the year.

15

The dramatic pricing increases in the single-family housing market has made buying a home unaffordable for

many families, contributing to increased demand for multi-family housing. The Gardner Institute reports that Salt

Lake County had 148,500 rental units at year-end 2021, but only 2% of these were vacant, creating the lowest

13

https://business.fau.edu/executive-education/housing-market-ranking/housing-top-100/index.php

14

https://www.deseret.com/utah/2020/12/9/22165836/housing-affordability-in-utah-entering-perilous-territory-study-says

15

https://news.move.com/2021-12-07-Realtor-com-R-Forecasts-the-Top-Housing-Markets-of-2022

7

vacancy rate in the 20 years for which data is recorded (Appendix 3-B, p. 1). Similar record low vacancies were

reported in Davis County of 1.9%, Utah County 2.2% and Weber County 2.1% (Appendix 3-C, p. 10). Limited

supply combined with high demand is driving apartment rents up: a September 2021 report by property

management firm Entrata found the average rent in 5 major Utah counties rose 45% in just 18 months (Appendix

3-L).

Source: Entrata; Utah’s Rental Market by the Numbers, 10 September 2021 (Appendix 3-L)

The COVID-19 pandemic also had a negative effect on construction of new housing units. The supply chain was

disrupted, particularly for building materials sourced from China and lumber from Canada, and quarantine

activity slowed the availability of labor (Appendix 3-C, p.11).

Unfortunately, construction currently underway as well as proposed apartment development will not be

sufficient to meet demand. There are 12,367 units under construction in Salt Lake County and 9,665 units

proposed. The Gardner Institute forecasts these will result in an apartment vacancy rate of just 5.7% by 2024

(Appendix 3-B, p. 3).

As Utah continues to be one of the nation’s fastest growing states, it is forecasted that demand for affordable

housing will continue to outpace supply. The rise in home prices will remain a barrier to homeownership for

lower-income households, and the limited supply of affordable rental housing will remain a challenge.

The following are key statistics regarding Utah’s housing affordability:

· Between 2010 and 2020, the growth in Utah households exceeded the growth in housing units by 44,500

housing units. The Gardner Institute notes “the shortage has created record low rental vacancy rates, the

smallest supply of unsold vacant new homes, and the smallest supply of vacant for-sale existing homes.

In other words, the shortage has removed vacant units from the housing market, an unhealthy condition

8

leading to higher housing prices and rental rates. Given the sizeable gap between household growth and

housing units, it will take several years for the housing market to return to a healthy condition” (Appendix

3-C, p. 8).

· Even before the pandemic, individuals and families living in the metro Salt Lake area were feeling the

impacts of insufficient affordable housing. Through 2018 (the most recent data reported by HUD’s

Comprehensive Housing Affordability Strategy), more than 41% of renter households in Salt Lake County

(nearly 60,000 renter households) were housing-burdened, paying more than 30% of their income for

housing and utilities. This number increased from 20% of renter households in 2009 (Appendix 3-B, p. 2).

· More than 50% of households in Utah are unable to afford the median price single-family home. For

renters, home ownership is increasingly more difficult due to record price increases. In 2019, 63.1% of

renter households could not afford the median home price, growing to 72.8% in 2020 (Appendix 3-C, p.

14).

· According to the National Low-Income Housing Coalition, the Fair Market Rent for a two-bedroom

apartment in Salt Lake County is $1,051 per month. In order to afford this level of rent /utilities without

paying more than 30% of gross income on housing, a household must earn $48,160 annually. A minimum

wage earner would need to work 128 hours per week to afford a 2-bedroom home (Appendix 3-D).

C. Economic Outlook and Other Relevant Data

Utah has experienced a relatively strong recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. The state added 72,500 jobs in

2021, making up for the 20,900 jobs lost in 2020 as well as adding 51,600 new jobs. While the state’s travel and

tourism industry has been among the slower industries to recover, Utah ski resorts had a record number of visits

in the 2020-2021 season as did visitors to the state and national parks. (Appendix 3-A, p. 161) The real estate and

construction industries remain strong due to factors discussed in the preceding section. Salt Lake County added

25,000 jobs in 2021, a 3.5% increase. The county posted a record-low unemployment rate of 1.7% in December

2021 (Appendix 3-B, p. 2).

In August of 2021, Forbes ranked Utah the top state for Gross Domestic Product (”GDP”) growth, reporting “The

Utah economy has been a powerhouse in recent decades, hence the reason why it takes the No. 1 spot. Over the

last five years, Utah’s GDP grew by an excellent 19.1%, the second-highest growth rate for that period out of all

50 states.” Utah’s GDP growth was only second to Washington state.

16

According to the March 2022 Utah Employment Summary, issued by the state’s Department of Workforce

Services, all industry sectors except the professional and business services sector (which helps supply temporary

labor to businesses, a difficult task in such a tight labor market), have added jobs over the past year. Utah’s job

growth was 4%, slightly below the national average of 4.6%. The state’s 2.0% unemployment rate was below the

national average of 3.6%.

17

One fast growing industry sector in the state is technology, for which the region has been nicknamed “Silicon

Slopes.” Of tech sector employees moving to the state, 79% said outdoor recreation and/or access to wilderness

and public lands was the dominant factor in their choice to move to Utah.

18

For more than 10 years, Utah has

consistently ranked within the top quartiles of many national indices as a hub supporting both small businesses

and technological advancements. Specific rankings in recent years include:

· In the 2022 WalletHub List of Best Small Cities to start a business, Utah holds 10 cities in the top 30 for

best cities to start a business.

19

16

https://www.forbes.com/sites/andrewdepietro/2021/08/04/2021-us-states-by-gdp-and-which-states-have-experienced-the-biggest-growth/?sh=2a7d15bc846c

17

https://jobs.utah.gov/blog/post/2022/04/14/utah-s-employment-summary-march-2022#continue

18

https://gardner.utah.edu/wp-content/uploads/Utah-Outdoor-Partners-Survey-Jan2021.pdf?x71849&x71849

19

https://wallethub.com/edu/best-small-cities-to-start-a-business/20180

9

· According to data by real estate data company Clever, Salt Lake City ranks as the second-best startup city

in the U.S. (behind Las Vegas). This is due to Salt Lake’s high concentration of CEOs providing access to

experience and networking opportunities (4.1 per 1,000 residents, three times the national average of

1.42 per 1,000) as well as the region’s highly educated workforce (more than half of those over age 25

have a bachelor's degree). University of Utah start-up businesses raised a record $884 million in

investment capital in 2021, and start-ups affiliated with Brigham Young University have raised $6.25

billion in venture capital funding to date (Appendix 3-H).

· According to the Milken Institute’s 2022 Report on Best-Performing Cities, a ranking based on jobs,

wages, and specifically high-tech growth, Utah holds two of the top three rankings in Tier 1 Large Cities

(Prove-Orem, UT and Salt Lake City, UT) and the top two spots in Tier 1 Small Cities (Logan, UT-ID and St.

George, UT). The report notes these rankings mark the continued success of the region in creating jobs

and raising wages (Appendix 3-I, p. 1).

As additional evidence of the strong technology and business sectors, in 2021, Utah’s technology and

enterprise/SaaS software sector accounted for 41% of the state’s $32.1 billion in equity related financial

transactions (Appendix 3-K). In addition to traditional enterprise and SaaS related technology, Utah is home to a

burgeoning healthcare innovation hub, with Utah’s healthcare technology seed-stage startups attracting a record

setting $79 million dollars raised in 2021 and health care innovation (developing new medicines, diagnostics,

services, and delivery methods to improve patients’ access and quality of care) representing $13 billion of the

state’s GDP (Appendix 3-J and Appendix 3-A, p. 141-144).

One measure of Utah’s economic health is the Hachman Index for economic diversity. Using indicators such as

gross domestic product or employment, the index measures the mix of industries present in a particular region

relative to a well-diversified reference region. Scores range from 0 to 100, with a higher score indicating more

economic diversity, while a lower score indicates less economic diversity. In 2021, Utah fell from the most

economically diverse state in the U.S. in 2019 to sixth with a Hachman Index score of 95.47 (Appendix 3-A, p. 75).

Data is also available for counties within the UTAA. In general, urban counties tend to have more diverse

economies with a larger variety of employment opportunities and a wider range of industry sectors available to

the population. Salt Lake, Weber, Davis, Utah, and Tooele all have index scores above 75, ranking them in the

top 10 counties in the state for economic diversity. Summit County’s economy is tourism-based around Park City,

and therefore it has employment concentrations in arts, entertainment, recreation, accommodations, and food

services. Morgan County also has a low Hachman Index score because it has the state’s highest concentration of

construction-related employment (Appendix 3-A, p. 76).

Table 5: UTAA Hachman Index

Source: (Appendix 3-A, p.75-78).

County Hachman Index, 2020

Salt Lake 93.90

Tooele 79.10

Davis 85.70

Weber 88.90

Morgan 53.40

Utah 82.00

Summit 38.90

Wasatch 67.00

Utah overall 95.50

UTAA Hachman Index Scores

10

Economists report a tight labor market, combined with low housing supply and corresponding high housing

prices, pose the greatest risk to Utah’s economic growth in the next few years. Unemployment is expected to

remain around 2%, which will create upward pricing on labor wages (Appendix 3-A).

The following highlights were taken from the full 2022 Economic Report to the Governor (Appendix 3-A):

• Personal Income: Utah’s total personal income in 2021 was an estimated $179.2 billion, a 5.7% increase

from $169.7 billion in 2020. Utah’s estimated 2021 per-capita income was $53,859, up 3.2% from

$52,204 in 2020 and a 24% increase from the 2017 per-capita income of $43,459 data reported in Ally’s

2020-2022 Plan. Components of personal income include net-work earnings, dividends/interest/rent and

transfer payments including government benefits such as Social Security. Utah has the lowest share of

transfer receipt income of any state. The highest work earnings from Utah’s private sector came from

the professional, scientific, and technical services sector, followed by manufacturing and construction

(Appendix 3-A, p.29).

· Public Education: In fall 2021, there were 675,247 students in Utah’s public education system, an

increase of 8,638 students (1.3%) from fall 2020. Although Utah’s student population is primarily White

(72.4%), it is becoming more diverse. In fall 2021, 18.7% of Utah’s student body was Hispanic or Latino,

1.6% was Asian, 1.6% was Pacific Islander, 1.3% was African-American or Black, 0.9% was Native

American/Alaskan/Hawaiian, and the remaining students (3.3%) identified with multiple ethnicities.

According to the 2017 state population projections, within the school-age population (5 to 17 years of

age) individuals identifying as non-White will grow from 25% in 2015 to 42% in 2065. In fiscal year 2018,

the most recent year for which National Center for Education Statistics data are available by state, Utah’s

net current expenditure per pupil was $7,576 (the nation’s lowest). However, some consider current

expenditure as a percent of total personal income as a better measure of Utah’s effort to fund public

education. Using this measure, Utah ranks 36th nationally, at 3.5% of personal income (Appendix 3-A, p.

103).

• Nonprofit Sector: Internal Revenue Service (“IRS”) data shows that Utah has 10,750 nonprofits operating

within the state, a 0.40% increase from 2020, with total assets from reporting entities worth $38.2

billion, a 12.9% increase from the year prior. The sector also reported total income of $33.7 billion, a

24.6% increase, and total revenue of $17.3 billion, a 3.3% increase. While the IRS reports an increase in

revenue at nonprofits from 2020 to 2021, the data reveals that the vast majority of nonprofits in Utah are

small. Accordingly, 6,526 nonprofits don’t report any income (religious organizations and those with

income below $50,000 are not required to report). In April 2021, the Utah Nonprofits Association (UNA)

surveyed Utah nonprofits about their finances, changes in demand for their services, financial resiliency,

and staffing. The results indicate that 74% of nonprofits who responded to the survey have seen an

increase in demand for services. While these nonprofits’ total revenues decreased by 30% in 2020

compared with 2019, organizations estimated a 10% increase in 2021 compared with 2020. Nonprofits

also projected a 37% decline in 2021 staffing compared with 2019 (Appendix 3-A, p. 149).

· 2060 Projections: The Gardner Institute economists forecast Utah’s population to grow from 3.3 million

in 2020 to 5.5 million in 2060 with a corresponding increase from 1.1 million households in 2020 to 2.2

million in 2060. An aging population will play a role in a projected decrease in household size, from 3.0

people per household in 2020 to 2.3 in 2060. The Greater Salt Lake Economic Region will lead this

growth, growing from 2.8 million residents in 2020 to 4.6 million in 2060. Utah County’s projected

addition of nearly 674,000 residents between 2020 and 2060 results in a population of 1.3 million and

driving over one-third of total regional growth. A projected 2060 population of 1.7 million will keep Salt

Lake County as the largest county in the future. Utah’s growing economy will likely add 1.3 million jobs

over the next four decades to reach 3.4 million jobs by 2060. Salt Lake (545,500 jobs), Utah (346,500

jobs), Davis (114,000 jobs), and Washington (109,900 jobs) counties account for over 80% of the

11

anticipated job growth. The projected job gains in construction (207,100 jobs), health care and social

assistance (184,900 jobs), and professional, scientific, and technical services (195,100 jobs) sectors drive

this change (Appendix 3-A, p. 165).

SECTION IV. NEEDS AND OPPORTUNITIES IN THE ASSESSMENT AREA

As detailed in Ally Bank’s Previous Strategic Plans, the Bank engages in several ongoing needs assessment

activities, including regular meetings and calls with several community partners (as discussed below) for the

purpose of determining community needs. In formulating this 2023-2026 Plan, Ally Bank has built upon its

previous needs assessment efforts with updates through both informal processes and a more formal survey

process described below.

A. Needs in the Assessment Area

Covid-19 has had significant impacts in Utah since early 2020 and magnified the needs of already vulnerable

people in Utah. Utah had the sixth highest rate of Covid cases per million people in the country, yet experienced

one of the lowest fatality rates of all the states which was primarily attributed to its relatively young population.

Utah also experienced one of the lowest unemployment rates in the country following the onset of COVID-19,

although unemployment did spike to over 10% in the early stages then quickly recovered. Those in poverty and

lower income service workers in the hospitality and retail sectors were disproportionately affected, experiencing

job or wage loss of 38% due to the pandemic which was twice the rate of the general labor force in 2020

(Appendix 3-E, p. 4). In general, the immediate impacts from Covid appear to have been largely alleviated with

help from unemployment benefits, the federal stimulus package and policy changes. However, evaluation

continues with regard to the potential for longer-lasting impacts on academic achievement, economic success,

and physical and mental health. Comments from many of the UTAA service providers indicate that in most cases,

the challenges facing lower income populations were exacerbated by the impacts of Covid, with rising inflation

already placing increased hardships on lower-income individuals and families.

1. Informal Needs Assessment Process: Several Ally Bank employees are actively involved in leadership

roles with local community organizations, the missions of which include serving the needs of LMI individuals

within the UTAA. During the course of their service, these employees derive meaningful Information from their

informal interactions, which facilitates ongoing access to timely information relevant to community needs and

the related gaps in services. The Bank also engages in regular communication with several additional entities

operating within the Bank’s UTAA, including affordable housing developers, affordable housing loan funds,

nonprofit community service providers (including healthcare, mental health, and substance abuse treatment

providers), and providers of small business capital.

Ally Bank senior executives have also participated over the years in the Bank’s needs assessment process through

meetings with various nonprofit and for-profit entities to learn about needs within the Bank’s UTAA, as well as

related challenges and opportunities. Although in-person meetings have been greatly reduced due to COVID-19

restrictions, the Bank’s President of Consumer & Commercial Banking Products, along with the Auto Chief

Operating Officer, participated in meetings with key community partners in the UTAA. Ally senior management

has continued an ongoing dialogue with impactful organizations about additional support and opportunities for

expansion. CRA loan officers continue to devote considerable time and effort structuring loans with various

nonprofits to assure that these loans would best serve the needs and mission of each organization while also

meeting the Bank’s requirements.

In addition to direct communication with numerous community partners, Ally Bank also reviewed and analyzed

several informative reports provided by government entities, as well as community development and research

organizations, to help identify needs within the UTAA (links to these reports are in Appendices 3 and 4.B).

12

2. Formal Needs Assessment Process: As part of updating its needs assessment, the Bank developed a

needs assessment survey and invited participation from numerous community-based agencies and other

organizations that are engaged in qualifying community development activities and serve residents within the

UTAA. This year, fifty-six (56) organizations responded to the survey (see Appendix 4-A for a list of survey

participants) and provided responses to questions regarding:

· Organizational focus

· Geographies and populations served

· Greatest needs of populations served

· Top challenges experienced by populations served

· Primary barriers to achieving organizational mission

3. Needs Assessment Findings and Conclusions: The top four greatest needs consistently identified by the

organizations responding to the Bank’s survey were similar to those identified through the Bank’s 2019 survey,

although with a different priority, and include the following:

a. Affordable Housing (remained the greatest need)

b. Employment Opportunities

c. Access to Affordable Healthcare (including mental health)

d. Educational Opportunities

The four areas of greatest need identified through the Bank’s survey overlap to a significant extent with the

issues identified in the various government and economic reports and needs assessments analyzed by the Bank

(see Appendices 3.A-H and 4.B).

a. Affordable Housing: Organizations representing a broad cross section of survey respondents

most often cited lack of access to safe, decent, affordable housing as the greatest need for lower-income

individuals and families. This is particularly true for special needs populations including (i) homeless individuals;

(ii) aging adults; (iii) persons with disabilities; (iv) individuals coming out of the criminal justice system; and

(v) individuals receiving mental health and substance abuse treatment. One respondent observed that access to

stable, affordable housing is essential in order to address a myriad of needs experienced by lower-income

individuals and families, such as financial stability, healthcare, mental well-being, education and more.

The lack of affordable housing has continued to be recognized as the biggest challenge for these populations and

the need continues to grow, particularly given the rising barriers to homeownership and the increased costs to

build affordable rental housing. Home prices and rental rates have continued to rise significantly over the past

two years, with the affordable housing crisis particularly concentrated in households with income below the

median, as discussed in Section III.B above. Affordable rental housing remains in short supply, with

approximately 41% of renters spending more than 30% of household income for housing expenses, and nearly

19% of renters spending at least 50% of household income for housing. The Bank has actively supported, and will

continue to support, the creation and preservation of affordable housing through direct loan originations, loan

purchases, loan participations, lines of credit to Community Development Financial Institutions (“CDFI”) and loan

funds such as the Rocky Mountain Community Reinvestment Corporation (“RMCRC”), as well as investments in

Low Income Housing Tax Credits (“LIHTC”) and affordable housing preservation funds.

b. Employment Opportunities: Survey respondents cited employment opportunities as the second

greatest need among the populations they serve. While Utah’s unemployment rate has been one of the lowest

in the nation over the past few years, the unemployment rate does not account for individuals who are employed

but face challenges such as (i) employment that is not secure or may be temporary or part-time; (ii) low wage

13

jobs that provide insufficient income to meet family needs; (iii) lack of access to training to improve job skills and

wages; (iv) lack of benefits such as health insurance or paid sick leave; and (v) record of prior criminal activity.

One respondent noted that the demand for job training and educational opportunities has increased since many

individuals left the service industry due to Covid. Additionally, respondents noted that for many individuals,

including refugees, the path to better economic stability may be self-employment.

Because small businesses are a significant source of job creation, support for the formation and expansion of

small businesses helps address the need for more and better jobs. The Bank has provided, and will continue to

provide, access to capital and technical assistance programs for small businesses through charitable grants, loans,

and investments. The Bank has worked with organizations such as the Wasatch Community Gardens, Flourish

Ventures, The Suazo Business Center, and the Utah Microenterprise Loan Fund which provide job training

programs, facilitate entrepreneurship, and support small businesses through loans and technical assistance.

The Bank has also made investments through Small Business Investment Company (“SBIC”) funds (both debt and

equity) and community development venture capital funds to support the growth of small businesses and job

creation.

c. Access to Affordable Healthcare: The third most frequently cited need was access to affordable

healthcare, including (i) dental care; (ii) vision services; (iii) mental health treatment; and (iv) substance abuse

treatment. While Utah’s uninsured rate is relatively low compared to other states, it is not consistent

throughout the state nor for all population groups. According to Utah public health data, approximately 12% of

all Utah adults are uninsured; however, areas in some rural counties in the state have uninsured rates in excess

of 15% (Appendix 3-A, p. 131 & 138). Utah residents with lower household income, particularly those who live in

poverty and who lack education, are most likely to be without health insurance. Some minority populations have

been disproportionately affected, with uninsured rates of approximately 23% for Black/African Americans and

nearly 30% for Hispanic/Latinos (Appendix 3-A, p. 136). One survey respondent commented that due to job loss

during the pandemic, many individuals and families lost access to health insurance.

The rising cost of health insurance premiums and deductibles has compounded the problem by causing a

significant increase in high-deductible health plans. Both lack of insurance and high deductibles often cause

individuals to delay or avoid treatment for medical conditions, which ultimately results in more critical illness and

increased costs for treatment. Despite gains in the number of children who have healthcare coverage, Utah has

one of the worst rates of uninsured children, ranking sixth highest out of all states in the nation (Appendix 4.B-5,

p. i). There is also a growing need to proactively address behavioral health in Utah children to mitigate the

longer-term implications such as suicide and depression, particularly in the aftermath of the pandemic. Several

survey respondents noted the emotional strains of the pandemic greatly affected children, witnessing parents’

anxieties while facing school closures, remote learning, and isolation from friends due to social distancing. Lower

income adults were also negatively impacted for similar reasons, including job or income loss, lack of access to

resources, and social isolation. The Bank has facilitated access to healthcare through charitable donations to

agencies such as Maliheh Clinic, Comunidades Unidas, Wasatch Homeless Healthcare, Polizzi Clinic, Friends for

Sight, and Utah Partners for Health, as well as loans and investments to support construction of public health

clinics.

d. Educational Opportunities: The lack of educational opportunities was frequently cited by survey

respondents, in particular (i) education relating to financial literacy; (ii) early childhood education;

(iii) homeownership preparation; and (iv) English as a Second Language. One survey respondent observed that

learning how to manage money was one of biggest challenges they saw with families at income levels below

125% of AMI (defined below). Several organizations commented on the detrimental effects from remote

learning and social isolation, with two charter schools serving low-income children reporting significant negative

impacts. One school noted that 70% of its students fell behind academically while another stated that many

students began the 2021-22 school year a full year behind academically.

14

Chronic absenteeism is more prevalent among children living in poverty at 24% compared to only 10% for all

Utah students (Appendix 3-E, p. 30). Earnings potential and financial security are highly correlated to the level of

education completed by an individual, with those lacking a high school diploma at a much higher risk of living in

poverty. Utah has made some progress, improving the graduation rate for children in poverty from 50% up to

79% since 2012. Although Utah is ranked as the sixth healthiest state, the United Health Foundation reports

health disparities continue to exist based on a variety of factors including socioeconomic status (Appendix 3-A, p.

131). Early childhood education can address these issues to help reverse intergenerational poverty.

Utah is a refugee resettlement area, with 15,000+ refugees settled in Utah since 1995 (Appendix 4.B-3). This has

contributed to rapidly growing ethnic and cultural diversity in Utah, creating a need for services to integrate into

the local community, facilitate English language proficiency, and secure employment. The cap for the refugee

resettlement program was recently raised with more refugees coming to Utah, which will place greater pressure

on local non-profits that address the needs of this population. The Bank has actively supported a variety of

educational programs through charitable donations and services, as well as loans, to support agencies such as the

International Rescue Committee, Neighborhood House, Guadalupe Schools, Success in Education,

NeighborWorks Mountain Country Home Solutions, and the Community Development Corporation of Utah.

The Bank’s survey also asked responding organizations to identify the greatest challenges to achieving their

respective missions. The top two barriers cited were inadequate funding resources and limited organizational

capacity. The challenges cited by most organizations include: (i) decline in funding resources due to tax reform

and resulting cuts in Federal programming; (ii) donor fatigue; (iii) the unwillingness of many institutional donors

to provide funds for operations; and (v) limited staffing with inability to pay an adequate wage and provide

competitive benefits. The staffing challenge is evident given the extremely low unemployment rate in Utah

(2.7%). It has been further exacerbated by the significant number of people who either left the workforce due to

Covid or left the non-profit sector for higher paying jobs with employers (such as fast-food establishments) that

were able to raise their minimum wage. Based on information collected through a survey conducted by the Utah

Nonprofits Association, as well as responses from the Bank’s survey, most nonprofits have experienced an

increase in demand for services and a significant decline in staffing.

These findings are supported by several national studies covering the nonprofit sector which consistently cited

lack of resources, including funding needs and inadequate staff, as the biggest challenges. One report noted that

community-based organizations (CBOs) affect the lives of one in five Americans, with the recipients of those

services and society as a whole facing significant risks if CBOs are not adequately funded. The Bank supports

capacity building through a diversified charitable donation program, as well as services and technical assistance,

all of which provide broad nonprofit support within the Bank’s UTAA.

Ally Bank has taken these needs into consideration in formulating this Strategic Plan and will continue to focus on

the issues identified through the Bank’s community needs assessment process – specifically, affordable housing,

job opportunities through economic development, educational opportunities, and access to healthcare. The

Bank plans to continue working with existing community partners, as well as identifying new organizations and

community development opportunities, in an effort to remain aware of community needs and opportunities.

B. Opportunities in the Assessment Area

Ally Bank has drawn upon an increased number and variety of sources (from its 2019 assessment) to assess both

the needs and opportunities in the UTAA. While there are unmet needs in the UTAA as discussed above, many of

the needs are not readily addressed through CD loans and investments (most requests from LMI service providers

are for charitable donations). Ally Bank continues to work diligently with a wide array of community partners in

the UTAA to develop additional ways to meet the UTAA’s needs other than through donations, but opportunities

to deploy significant amounts of capital in the form of CD loans or investments are limited because of Utah’s

relatively small population base (under 3.3 million people) and the disproportionate number of large banks with

15

CRA assessment areas (“AAs”) in Utah. These two combined factors create an extraordinarily competitive

environment for CRA-qualifying loans and investments, which has become even more challenging in the three

years subsequent to the submission of Ally’s 2020-2022 Plan due to the significant asset growth of the large non-

traditional banks that have Utah AAs significantly outpacing population growth in Utah, as discussed more fully

below.

1. Small Population in UTAA: The population of Ally Bank’s UTAA is just under 2.7 million people.

Although Utah was the fastest growing state in the nation over the past ten years (see Section III.A above), Utah

remains a relatively small state with just under 3.3 million people. A smaller population results in:

· fewer federal tax credit allocations,

· fewer strong nonprofits to which Ally Bank can extend CD loans, and

· fewer CD investments, including CRA-qualifying bonds.

For example, affordable housing is a strong need in the UTAA, but most multifamily affordable housing projects in

Utah rely on some level of federal or local government subsidy in order to keep rents low enough to be

affordable for LMI individuals.

20

Federal housing subsidies are typically based on state population. The average

amount of federal LIHTC allocated to Utah and awarded by the state housing finance agency over the last five

years is relatively small: approximately $92 million (which resulted in an average of 15 multifamily affordable

housing projects per year and the addition of 640 new affordable housing units per year).

21

The addition of 640

new affordable housing units per year is a positive step, but does not come close to alleviating the growing

shortage in available affordable housing units estimated to be 54,000 units.

State subsidies also play a smaller role in affordable housing, but can be restricted by state budget constraints in

any given year. In the area of single-family affordable housing, over the last three years the state housing finance

agency issued only $216 million in CRA-qualifying taxable housing revenue bonds. By contrast, the state housing

finance agency has originated an average of $1.1 billion of new single-family loans annually over the past three

years. Utah Housing Corporation (Utah’s largest financer of affordable housing) has made a shift away from the

use of mortgage revenue bonds (“MRB”), with the bulk of the loans sold as Ginnie Mae, Freddie Mac or Fannie

Mae mortgage-backed securities with only $27.3 million of new taxable MRBs issued last year.

22

2. Disproportionate Number of Large Banks in a small state: Utah is home to numerous non-traditional

banks that offer banking products and gather deposits nationwide but typically do not have branches or ATMs

that would result in a CRA AA. Utah’s concentration of these large non-traditional banks stems primarily from

the rapid growth in the Utah Industrial Bank industry starting in the mid-1990s and continuing through 2005,

when companies such as Merrill Lynch, American Express, General Electric, BMW, General Motors, Sears, Wright

Express, Fry’s Electronics, and Target obtained Industrial Bank charters. Additionally, several of today’s largest

non-traditional banks with Utah CRA AAs previously operated under an Industrial Bank charter (see Table 6

below).

Many of the non-traditional banks have assets over $10 billion, with six of them having assets over $85 billion

(see Table 6 below). In fact, the six largest non-traditional banks have combined total assets of over $1.191

trillion as of 3/31/2022, an increase of over $425 billion (approximately 56%) from the $766 billion of total assets

these same six banks had as of 6/30/2019:

20

In light of the restricted amount of LIHTC awarded to Utah, many participants in the affordable housing industry are working collaboratively on developing methods of

increasing the amount of affordable housing units without reliance on government subsidies. However, these are not easy issues, and an acceptable solution may take several

more years to develop.

21. See Utah Housing Corporation website located at the following link: https://utahhousingcorp.org/multifamily

22

See Utah Housing Corporation 2020 and 2021 Annual Reports at the following link: https://utahhousingcorp.org/multifamily

16

Table 6: Large Non-Traditional Banks (Assets > $85B) with a Utah Assessment Area

There are also 21 Utah state-chartered commercial banks (with combined total assets of $192 billion), most of

which have branches/AAs in Salt Lake County. There are also 16 Utah Industrial Banks with combined total assets

of $179 billion (Appendix 3-N). In addition to all of the banks listed above, there are several large national retail

banks that also have Utah AAs: Bank of America, Chase Bank, Wells Fargo Bank, U.S. Bank, Key Bank, Zions First

National Bank, and Bank of the West. In the June 30, 2021 FDIC Summary of Deposits, there were 44 FDIC-

insured banking or savings institutions with 202 office/branch locations in Salt Lake County alone.

The presence of so many banks, including some of the country’s largest banks by asset size, in such a small state

(in both population and area) results in extremely stiff competition for the limited supply of even the most

routine CD loans and investments, such as mortgage-backed securities (“MBS”) or bonds issued by the Utah

Housing Corporation. Because Ally Bank has less than 1% of its consumer loans in the UTAA, CD loans and

investments will continue to play vital role in Ally Bank’s CRA activities.

The combination of the UTAA’s small population and the number of increasingly large banks competing for the

same CD loans and investments has resulted in the Salt Lake area being known as a CRA “hot spot,” with

significantly higher pricing and “CRA premiums” on many loans and investments. There is fierce competition for

CD loans and also CRA-qualifying MBS in the UTAA, resulting in significant “CRA premiums.” Simply put, Utah

does not have enough capacity to absorb the combined billions of dollars per year of CD loans and investments

the banks listed above seek to deploy.

Ally Bank’s highest CRA priority has always been – and will continue to be – to demonstrate responsiveness to the

needs and opportunities in its UTAA. In light of the challenges in obtaining sufficient amounts of CD loans and

investments in the UTAA, and in accordance with the 2013 revisions to the Interagency Questions and Answers

Regarding CRA (“Interagency Q&A”), Ally Bank began actively seeking CD opportunities in the broader statewide

or regional area (“BSRA”) that includes the UTAA. In order to deploy the $5.4 billion in new loan and investment

originations under this Strategic Plan, Ally Bank will need to continue the strategy of making CD loans and

investments in the BSRA. For purposes of this Strategic Plan, Ally Bank’s BSRA will include the following 11

contiguous states of the West Region of the United States: Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Montana,

Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming (see map at Appendix 5).

Total Assets as of

3/31/2022

Regulator & Charter

Bank

Location

CRA Assessment Area

Ally Bank* $174,479,000,000 FRB - State Commercial Bank Utah

Salt Lake County + seven

additional Counties in Utah

American Express National Bank*

$132,189,503,000 OCC - National Bank Utah

Salt Lake, Summit, and Tooele

Counties in Utah

Goldman Sachs Bank* $474,643,000,000 FRB - State Commerical Bank

New York

(with Utah

branch)

Two AAs: (1) Multistate MSA

35644 (New York-Northern New

Jersey-Long Island, NY-NJ-PA);

and (2) Salt Lake, Summit, and

Tooele Counties in Utah

Morgan Stanley Bank* $201,737,000,000 OCC - National Bank Utah Salt Lake County

Synchrony Bank $86,123,000,000 OCC - Federal Savings Bank Utah

Formerly three AAs: Salt Lake,

Summit, and Tooele Counties in

Utah

UBS Bank USA $122,409,837,000 FDIC - Utah Industrial Bank Utah Salt Lake County

Total Assets: $1,191,581,340,000

*Formerly chartered as a Utah Industrial Bank

17

SECTION V. PUBLIC PARTICIPATION

A. Informal Public Suggestions

Ally Bank has sought informal suggestions and input from members of the public in the UTAA, as required by

12 C.F.R. §228.27(d)(1). The Bank works with numerous community partners (both Utah-based and

nationally/nationwide) in the development and refinement of its overall strategy to provide responsive loans,

investments, and services and also regarding measurable goals. Many of those community partners participated

in the Bank’s needs assessment survey discussed above. The categories of entities providing informal suggestions

include the following:

· Affordable Housing Developers (both nonprofit and for-profit)

· State Housing Finance Agencies

· Local Housing Authorities

· Community Development Financial Institutions (“CDFIs”)

· Affordable Housing Loan Funds

· Nonprofit Community Service Providers

· Healthcare Providers (including Substance Abuse Treatment Providers)

· Local Food Banks and Homeless Shelters

· Educational Service Providers

· Financial Literacy and Individual Development Account (“IDA”) Providers

· Small Business Equity and Loan Funds

· Small Business Development Centers

· Community Development Representatives

· Entities involved in New Markets Tax Credit (“NMTC”) Projects

· State, County, and Local Municipalities

· Economic Development Agencies

· Rural Agency Service Providers

· Local and Regional Public Policy Research Organizations

Regarding categories of needs to be addressed, the informal suggestions closely mirrored the needs identified in

the Bank’s formal survey results. In addition, several community partners requested that the Bank continue to be

active in providing capital to small businesses and in helping to establish new and innovative ways to finance

small businesses and foster entrepreneurism. Regarding the proposed increased amounts of specific UTAA goals,

partners expressed strong support, especially in light of the competitive CRA environment in Utah.

B. Formal Public Comment Solicitation

Ally Bank solicited formal public comment on this Strategic Plan for 30 days by publishing notice in at least one

newspaper of general circulation in the UTAA, as required by 12 C.F.R. §228.27(d)(2), and made copies of this

Strategic Plan available to members of the public who requested it during the 30-day timeframe. A copy of the

proof of publication is attached at Appendix 6. The Bank’s request for comment was published on August 7,

2022, and the 30-day public comment period concluded on September 6, 2022. Ally Bank received one request

for a copy of this Strategic Plan but did not receive any public comments. Prior to submission, this Strategic Plan

was approved by Ally Bank’s CRA Committee and the Ally Bank Board.

18

SECTION VI. ALLY BANK CRA STRATEGIC PLAN AND MEASURABLE GOALS

This Strategic Plan and its measurable goals reflect thorough analyses of the credit needs and opportunities in

Ally Bank’s UTAA (including significant public input); the Bank’s business strategy, capacity, and constraints; the

Bank’s two previous CRA Strategic Plans; the Bank’s past CRA performance; the CRA performance of peer banks;

and recently approved CRA Strategic Plans of other banks. Ally Bank’s measurable goals reflect the latitude

described in the Federal Reserve Board’s Guidelines for Requesting Approval for a Strategic Plan Under the

Community Reinvestment Act (“FRB Strategic Plan Guidelines”), which provide as follows:

The strategic plan evaluation option in the regulation provides a bank with the opportunity to tailor its

CRA objectives to the needs of its community and to its own capacities, business strategies and expertise.

Therefore, not all of the factors described in the regulation would necessarily apply to each strategic

plan. A bank has a great deal of latitude in constructing a strategic plan, but it is expected that public

participation in development of the plan will provide a bank access to the fullest possible information

about the needs of its community and how those needs might be met.

Ally Bank’s measurable goals also reflect the regulatory flexibility regarding a bank’s measurable goals, both in

how the goals are expressed and regarding the three performance categories (loans, investments, and services).

For example, although the regulations provide that a bank should address in its plan all three performance

categories and emphasize lending and lending-related activities, they also provide:

Nevertheless, a different emphasis, including a focus on one or more performance categories, may be

appropriate if responsive to the characteristics and credit needs of its assessment area(s), considering

public comment and the bank’s capacity and constraints, product offerings, and business strategy

(12 C.F.R. §28.27(f)(ii)).

Ally Bank has developed its two main measurable goals based upon these regulatory guidelines. Ally Bank

believes strongly that the construct of the combined loans and investments goal, in particular, will provide the

Bank with the critical flexibility necessary to be much more responsive to community needs and opportunities as

they arise.

Certain goals in this Strategic Plan were partially derived from confidential, proprietary non-public information

and analyses. Therefore, where noted, the basis for the goals is contained in Confidential Exhibits that are bound

separately from this Strategic Plan.

A. Definitions

As used in this Strategic Plan, the following definitions

23

shall apply:

· “Auto Loan” includes:

(1) loans to LMI consumers for the purchase of a vehicle (“LMI Consumer Auto Loan”), and

(2) closed-end loans of $1,000,000 or less to businesses located in an LMI census tract for the

purchase of a vehicle (“Small Business Auto Loan”).

23

For all defined terms, the LMI qualification shall be determined based on AMI/ MFI figures applicable as of the date of origination or purchase by Ally Bank or AFI, regardless of

any subsequent changes in AMI/MFI.

19

· “Broader Statewide or Regional Area” or “BSRA” shall include, for purposes of Ally Bank’s CD

activities, the 11 contiguous states of the West Region of the United States: Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho,

Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming (Appendix 5).

· “CRA-Qualifying Loan” includes the following loans either originated or purchased by Ally Bank (or, at

the Bank’s election, AFI): (1) CD Loans; (2) Mortgages to LMI Borrowers as defined below; and (3) Auto Loans as

defined above.

· “Community Development” (“CD”) has the meaning set forth in 12 C.F.R. §228.12(g)(1) – (5), with

sections (1) through (4) as follows:

1. Affordable housing (including multifamily rental housing) for low- or moderate-income individuals;

2. Community services targeted to low- or moderate-income individuals;

3. Activities that promote economic development by financing businesses or farms that meet the

size eligibility standards of the Small Business Administration’s Development Company or Small

Business Investment Company programs (13 CFR 121.301) or have gross annual revenues of

$1 million or less; or

4. Activities that revitalize or stabilize:

(i) low- or moderate-income geographies;

(ii) designated disaster areas; or

(iii) distressed or underserved nonmetropolitan middle-income geographies designated by the

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, FDIC, and the Office of the Comptroller of

the Currency. . . .

· “CD Loan” has the meaning set forth in 12 C.F.R. §228.12(h): a loan that has as its primary purpose

community development and . . . benefits the bank’s assessment areas(s) or a broader statewide or regional area

that includes the bank’s assessment area(s).

· “CD Investment” has the same meaning as “Qualified Investment” set forth in 12 C.F.R. §228.12(t): a

lawful investment, deposit, membership share, or grant that has as its primary purpose community development.

· “CD Service” has the meaning set forth in 12 C.F.R. §228.12(i): a service that has as its primary

purpose community development and is related to the provision of financial services.

· “Mortgage Loan to LMI Borrower” means a loan to an LMI borrower for the purchase or refinance of

a residence.

· “New Originations” for a calendar year will include new CD Investments, new CRA-Qualifying Loans

either originated or purchased by Ally Bank, and existing CD Loans that are renewed and credit underwritten that

year (can only count each loan once per year).

B. Framework and Methodology

Ally Bank will make $5.4 billion in loans and investments and provide 3,300 volunteer hours of CD Services over

the four-year plan period to earn an “Outstanding” CRA rating. There will be two main goals: the first goal is for

combined CRA-Qualifying Loans & CD Investments and the second goal is for CD Services. The framework and

methodology for each of these two goals are discussed below.

1. Goal for Combined CRA-Qualifying Loans & CD Investments: There is one overall combined goal of

$5.4 billion for new originations of CRA-Qualifying Loans & CD Investments (“Combined Loans & Investments

20

Goal”), which is almost 10% higher on an annualized basis than the Bank’s 2020 – 2022 Plan’s goal of $3.7 billion.

There are also annual interim goals from $1.3 billion to $1.4 billion (see Table 7 below) that increase gradually

from Plan Year 1 through Plan Year 4:

Table 7.1: Annual Interim Goal Ranges for Loans/Investments

The Combined Loans & Investments Goal also contains the following features:

· UTAA goals: Because Ally Bank’s highest CRA priority is responding to the needs and opportunities in

the UTAA, there are three specific UTAA lending and investment goals that must be achieved through CRA-

Qualifying Loans or CD Investments that benefit the UTAA, including activities in the BSRA that directly benefit

the UTAA and entities whose purpose, function, or mandate includes serving geographies or individuals located

within the UTAA (Interagency Q&A §___.12(h)-6)). The three specific UTAA goals below all reflect increases that

correspond to the overall goal increase:

o Auto Loans: This goal encompasses both LMI Consumer Auto Loans and Small Business Auto

Loans and is appropriate in light of Ally’s position as a national leader in auto finance. This goal

contains a requirement that at least 90% of the Small Business Auto Loans must be $100,000 or

under.

o Mortgage Loans to LMI Borrowers: This goal is reflective of Ally’s commitment to affordable

single-family housing for LMI individuals.

o CD Loans/Investments: This goal is appropriate because CD Loans and CD Investments have

historically made up the vast majority of the dollar amounts of Ally Bank’s CRA performance in the

UTAA, primarily because Ally Bank’s nationwide business model results in the Bank having small