1INTERNEWS: INFORMATION ECOSYSTEM ASSESSMENT (IEA)

“Mapping of Bangladesh’s media landscape with a focus on youth,

women, and persons with disabilities with the objective of enhancing

their engagement in the country’s elections and political processes.”

Conducted By

Prof. Sheikh Mohammad Shaul Islam, PhD

Lead Researcher

September 6, 2023

INFORMATION

ECOSYSTEM

ASSESSMENT (IEA)

INTERNEWS: INFORMATION ECOSYSTEM ASSESSMENT (IEA) 2

DISCLAIMER

The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reect the views of the United

States Agency for International Development or United States Government.

3INTERNEWS: INFORMATION ECOSYSTEM ASSESSMENT (IEA)

Table of Contents

Executive Summary .............................................................................................................................. 8

Chapter One: The Study Settings ....................................................................................................13

1.1 Conceptual Underpinning: What is the Information Ecosystem Assessment? ..........13

1.2 Research Objectives ..................................................................................................................14

1.3 Study Methods and Materials .................................................................................................15

1.4 Survey Data Collection ..............................................................................................................16

1.5 Selection of Individual Respondents .....................................................................................18

1.6 Qualitative Approaches ............................................................................................................18

1.7 Data Gathering, Management and Analysis ........................................................................19

1.8 Study Limitations and Overcoming Strategies ...................................................................20

Chapter Two: IEA Findings ................................................................................................................ 21

2.1 Bangladesh Mediascape ..........................................................................................................21

2.2 Media Regulatory and Policy Frameworks ..........................................................................22

2.3 Community Access and Exposure to Media ......................................................................23

2.4 Barriers to Accessing Media ...................................................................................................28

2.5 Barriers to information during COVID-19 .............................................................................28

2.6 Preferred Communication Channels/Media on Elections and Politics .......................29

2.7 Community’s Preferred Formats of Media Content ..........................................................30

2.8 Perceptions on Media’s Role in Election, Accuracy and Impartiality............................31

2.9 Information Supply and Demand/Need ..........................................................................37

2.10 Community Trust in Media ...................................................................................................40

2.11 State of Mis-/disinformation, Hate Speech and Media Literacy ..................................44

Chapter Three: Conclusion and Recommendations ....................................................................57

Recommendations ...................................................................................................................58

Bibliography ......................................................................................................................................... 63

Annex 1 ................................................................................................................................................. 66

Annex 2 ................................................................................................................................................. 79

Endnotes ..............................................................................................................................................94

INTERNEWS: INFORMATION ECOSYSTEM ASSESSMENT (IEA) 4

List of Tables

Table 1. Target group sample distribution 17

Table 2. Respondent’s understanding of misinformation 44

Table 3. Subjects of misinformation 45

Table 4. Who spread misinformation (multiple responses)? 45

Table 5. Respondent’s understanding of disinformation. 46

Table 6. Who spread disinformation (multiple answers)? 46

Table 7. Rating respondent’s knowledge/understanding of mis-/disinformation 47

Table 8. Ability to identify mis-/disinformation. 47

Table 9. Rating respondent’s knowledge/understanding of mis-/disinformation by groups 48

Table 10. Ability to identify mis-/disinformation by groups 48

Table 11. Who spread hate (multiple responses) speech? 49

5INTERNEWS: INFORMATION ECOSYSTEM ASSESSMENT (IEA)

List of Figures

Figure 1: Distribution of sample as per division 17

Figure 2: Distribution of FGD Participants 18

Figure 3.1: Ownership of Electricity and Internet by groups 24

Figure 3.2: Ownership of Laptop and Desk Computer by groups 24

Figure 3.3: Ownership of Television and Radio by groups 24

Figure 3.4: Ownership of smart phones and button phones by groups 25

Figure 4: Percentage distribution of multiple responses on the types of barriers to access to the media 28

Figure 5: Percentage distribution of multiple responses on the use of media/channels to get infor-

mation on politics and election

29

Figure 6: Percentage distribution of multiple responses on preferred formats of media contents 30

Figure 7: Percentage distribution of the responses on media's fair coverage to help voters in

selecting candidates

31

Figure 8: Percentage distribution on perception of the media accuracy by the types of respondents 32

Figure 9: Percentage distribution on division wise perception of the respondents on the accuracy

of news media

33

Figure 10: Respondent’s perception of media impartiality 34

Figure 11: Percentage distribution on perception of news media’s impartiality by types of

respondents

34

Figure 12: Percentage distribution of the multiple responses on the reasons of perception of

media's unequal coverage

35

Figure 13 Reporters without Boarders World Press Freedom Index 36

Figure 14: Key Challenges of BD Media at a glance 37

Figure 15: A percentage comparison between the information that the respondents receive and

intend to receive

38

Figure 16: Percentage distribution of the multiple responses on community information needs 39

Figure 17: Division-wise distribution of percentages of multiple responses on information needs 39

Figure 18: Percentage distribution of the multiple responses on trusted media in getting political

and electoral news

41

Figure 19: Frequency distribution of responses on trusted online/social media platforms 41

Figure 20: Percentage distribution of the multiple responses on subjects of disinformation around

election

46

Figure 21: Percentage distribution of the multiple responses on subjects of hate speech 49

Figure 22: Percentage distribution of the multiple responses on media spreading mis-and

disinformation

50

Figure 23: Frequency distribution of the responses on top three social media sources of

disinformation

51

INTERNEWS: INFORMATION ECOSYSTEM ASSESSMENT (IEA) 6

Acknowledgement

The study titled ‘Information Ecosystem Assessment (IEA) — Mapping Bangladesh’s media

landscape with a focus on youth, women, and persons with disabilities to enhance their

engagement in the country’s elections and political processes’ is carried out for Internews, a

not-for-prot organization working for the capacity building of the local media. The research

team is indebted to the communities, especially the youth, women, and people with disabil-

ities who kindly shared their perspectives on their media exposure and information needs

around election and politics. In addition, several journalists, youth leaders and civil society

organizations were open to discussing their experiences, opinions and suggestions with us.

We are very thankful to them. The study team would like to record deep gratitude towards the

Internews Bangladesh team as well as the international experts for their valuable guidelines

and insights.

The study ndings facilitate Internews Bangladesh to plan and implement a pragmatic course

of campaign activities for disseminating true and adequate information on election and poli-

tics that capacitate the target groups to choose their representatives. The study ndings will

help to design training and workshops for the media people covering elections and politics.

The ndings will also provide Internews and its partners with an overview of the state of mis/

disinformation and the level of awareness among communities. This will result in designing

future activities for diverse groups like civil society, youth, women leaders, local journalists,

etc., to combat the menace of mis/disinformation.

7INTERNEWS: INFORMATION ECOSYSTEM ASSESSMENT (IEA)

Acronym/Abbreviations

AAPOR The American Association for Public Opinion Research

BBS Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics

BNP Bangladesh Nationalist Party

CBO Community Based Organizations

CSO Civil Society Organization

CEPPS Consortium for Elections and Political Process Strengthening

DFP Department of Films and Publications

DG Director General

ED Executive Director

EVM Electronic Voting Machine

FGD Focus Group Discussion

GDP Gender Diverse People

IEA Information Ecosystem Assessment

IEC Information, Education and Communication

KII Key Informant Interview/Key Informant Interviewee

Mis-/Disinformation Misinformation and Disinformation

NGO Non-Government Organizations

PSU Primary Sampling Unit

PWD People with Disability

TG Target Group

INTERNEWS: INFORMATION ECOSYSTEM ASSESSMENT (IEA) 8

Executive Summary

Bangladesh is undergoing democratic deterioration despite its triumphant march towards

socio-economic progress. According to ‘Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem)’ Institute of Sweden,

the country is experiencing a decline in liberal and electoral democracy. Bangladesh is ranked

147th among 179 countries in the ‘Liberal Democracy Index’ and 131st in the ‘Electoral

Democracy Index’ down from the previous year.

1

The Freedom of the Press Index prepared

by ‘Reporters without Borders’ shows the country is backsliding, in 2023 Bangladesh ranked

163rd, out of 180 countries, down from 162nd in 2022.

2

One-party dominance, implementation

of the draconian Digital Security Act 2018, Ocial Secrecy Act 1923, the Penal Code 1860, and

other repressive colonial laws are a few obstacles to the pathways of democracy and media

freedom. The Bangladesh media is undergoing transitions in management and ownership,

change of audience, shifting technology, evolving internet-based media; the need for digital

skills to manage social media dynamics, and declining trend of press freedom.

In this context, Internews, an international non-prot organization, that contributes to empow-

ering local media and civil society to facilitate the ourishing of democracy and citizen rights,

has commissioned an Information Ecosystem Assessment (IEA) in Bangladesh with funding

support from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The overall

objective of the study is to understand Bangladesh’s media landscape, analyze the target

groups’ i.e., the women, youth, and people with disabilities (PWD) media and information

consumption habits and needs particularly around political and electoral process, as well as

identify potential actors that focus on serving the information needs of the target groups and

map out the ow of disinformation. The assessment facilitates Internews and its partners to

better inform and engage Bangladesh citizens and civil society groups in elections and political

processes, through creating a healthy, dynamic, and transparent information environment that

will empower citizens to make better-informed decisions, bridge divides, participate eectively

in their communities, and hold power to account.

The IEA applies a mixed method approach incorporating a questionnaire survey on 480

respondents, including 293 women, 149 youth

3

and 38 PWDs. In addition, the team conducted

20 Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) with diverse groups consisting of youth, women, local

media, civil society, and marginalized groups; as well as 40 Key Informant Interviews (KIIs) to

capture qualitative perspectives of the community’s media exposure habits, their information

needs around the election, and the level of awareness on mis-/disinformation and hate speech.

9INTERNEWS: INFORMATION ECOSYSTEM ASSESSMENT (IEA)

Community access to media/ownership of devices: The survey reveals that 79% of respon-

dents possess a TV set, 85% smartphones, and 74% feature phones.

4

Only 14.6% of respon-

dents buy newspapers while radio and magazines are the least accessed media. Comparative

ownership of smartphones shows the youth have the highest rates with 96.6%, while 82%

women and 63% of PWDs own smartphones — depicting a disparity in terms of smartphone

ownership. Regarding challenges/barriers to access to media, about 62% of respondents

mentioned lack of access to quality internet; 21% report nancial insolvency, while 19.6%

note poor infrastructure and roads hinder communication.

5

Access to the internet: The IEA survey shows that 59% of youth, 50% of women, and 34%

of PWDs have regular connectivity — revealing a disparity in access for marginalized groups.

Access to social media: Youth have the highest use of online news portals and social media

with 61.7% and 83% respectively while 34% women use online news portals and 46% use

social media. Only 18% of PWDs use online news portals and 29% use social media as infor-

mation sources. This depicts a clear disparity for PWDs in use of the online news portals and

the social media. Of social media platforms/apps, Facebook is most widely used by survey

respondents at 68%, 65% extensively use YouTube, while WhatsApp and Imo are both used

by the 36% respondents, and TikTok by 27%.

Community exposure to media and contents: In terms of daily use, television is the most pop-

ular information source at 56% of responses, followed by social media with 45% of responses.

Out of the 170 participants, 35% used interpersonal communication channels.

6

Interpersonal

channels are favored by PWD (74%), women (60%), and youth (56%). KII and FGDs with local

journalists mention that across age, gender, and education, people prefer audio-visual content

such as short lms, dramas, documentaries, and promos.

Mis-/Disinformation: Only 36.5% of respondents understand the issue of misinformation, while

38% incorrectly dene the issues, and more than 25% do not know about the misinformation.

7

Conversely, about 58% respondents reported understanding the issue of disinformation. Of

the respondents, 46% view Facebook as the primary source of spreading mis-/disinformation.

According to FGDs and KIIs with media and CSOs, countering disinformation, misinformation,

and hate speech is still a new phenomenon to most of Bangladesh’s civil society, and they

lack the skills and experience to deal with these issues. Only a few mainstream news media

conduct fact-checking training and workshops for their sta to help identify fake information.

The study reveals insucient election reporting, particularly the investigative ones, resulting

from journalists’ inadequate understanding of election reporting and dearth of support from

the media organizations.

INTERNEWS: INFORMATION ECOSYSTEM ASSESSMENT (IEA) 10

Fair coverage of political news:

Election and media: According to the IEA survey, 58% of people agree the media’s fair cov-

erage of political news can facilitate them to understand political issues and aairs well and

select their representative properly. However, media content is not fair all the time. According

to 68% respondents, the media does not provide equal coverage to all political leaders/elec-

toral candidates. Out of the respondents who perceive that media does not provide equal

coverage to candidates, more than 72% of responses point towards pressures from vested

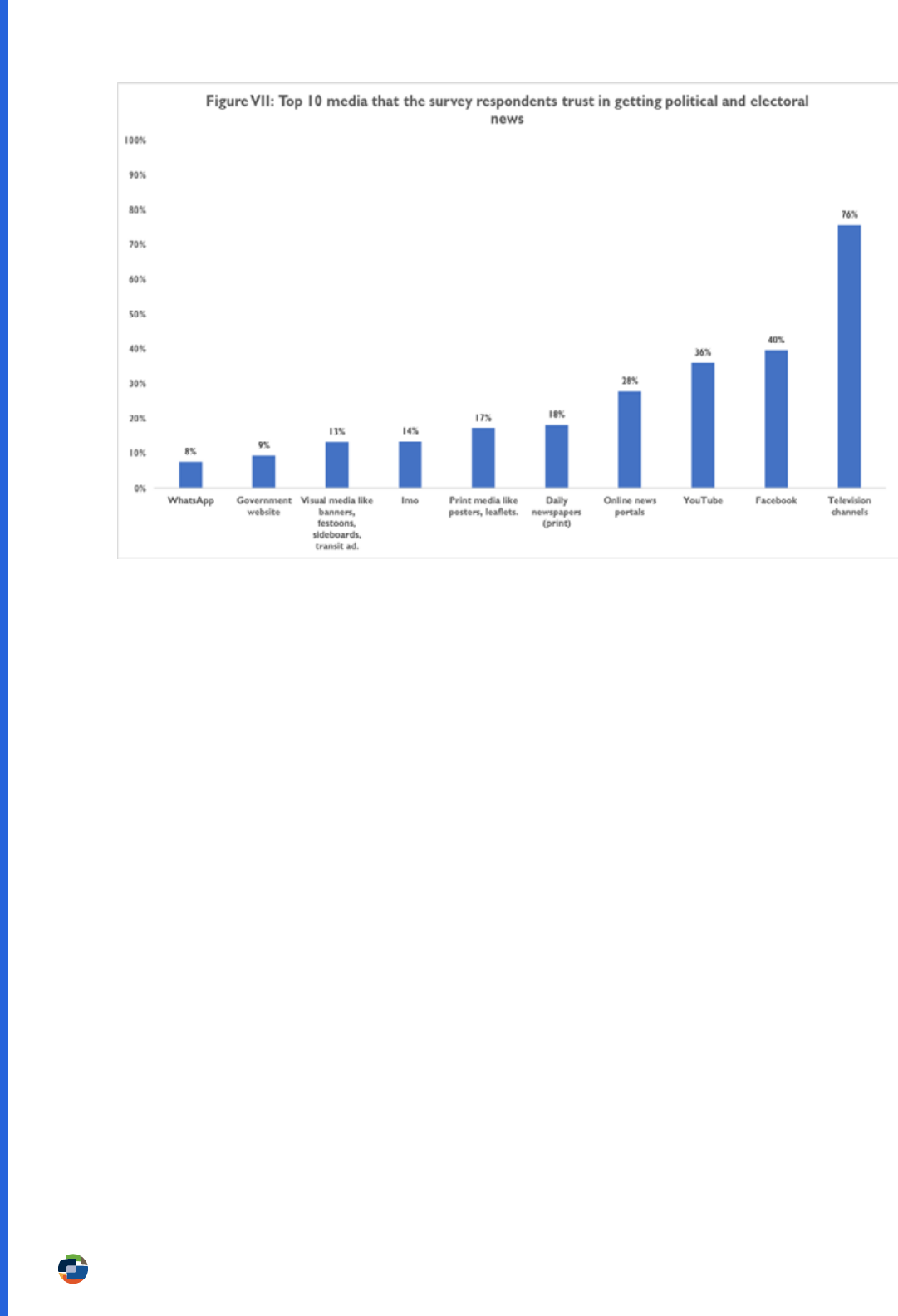

interest groups and the news media’s political aliation. According to 77% of respondents,

television is the most trusted media for receiving political and electoral news, while the social

media platform, Facebook is preferred by 40% of respondents.

Media accuracy and impartiality: According to 69% of respondents, news media are ‘somewhat

accurate’ meaning there are gaps in terms of media accuracy. On the other hand, the news

media, in the view of 76% respondents, are ‘somewhat impartial’ in presenting the political and

electoral news. The FGD and KII ndings reveal that the dearth of skills, particularly in covering

in-depth election reports and fact-checking, along with the political aliation of the media

in Bangladesh and pressures from powerful groups (such as corporate elites, law-enforcing

agencies, and the government administration) as well as journalists’ own political ideology,

are the key factors hindering media accuracy and impartiality.

Media literacy: Basic literacy is considered a precursor to media literacy,

8

and according to

the Population and Housing Census 2022, the literacy rate in Bangladesh stands at approxi-

mately 75%.

9

With these statistics in mind, it is understandable that a signicant majority of

respondents (80%) rely on television as their primary source of information.

10

The KII ndings

further emphasize the severe lack of media literacy in Bangladesh, which is evident in the IEA

survey examining the level of awareness regarding the use of newly emerged social media

platforms and the prevalence of mis-/disinformation.

11INTERNEWS: INFORMATION ECOSYSTEM ASSESSMENT (IEA)

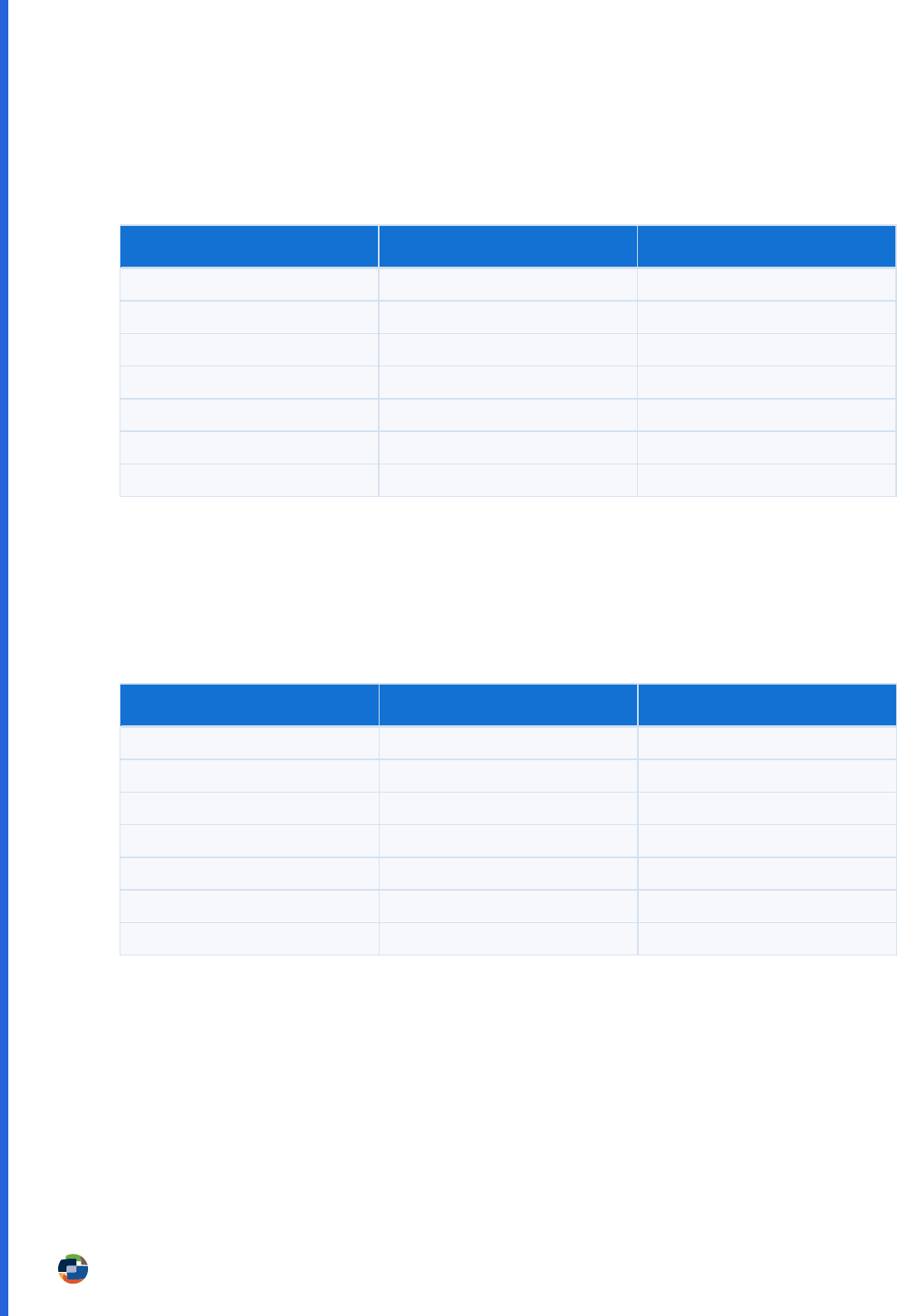

TG-based preferred media and info needs: At a glance

Who prefers? What media? How much?

Major info needs on

election

Television channels 80%

Safety and security,

especially for the women,

senior citizen and PWDs;

voting procedure using

EVM; punishment for viola-

tion of electoral rules; dis-

qualications for elections;

candidates’ qualities and

contributions to society.

Interpersonal

communication

channels/platforms

74%

Social media 83%

Conclusion

In Bangladesh, the news media is fractured and there is a lack of coordination. In general,

there are no standard practices for operational procedures and media management; rather

each media group has their own structure regarding recruitment, promotion, salary, and

fringe benets, which is a barrier to establishing industry standards that promote journalistic

professionalism.

11

In a more liberal atmosphere, the news media, serving as the watchdogs

for society, can generally play a role in the process of democratization. There is a strong link

observed between the political aliations of the news media and their content coverage.

Additional challenges to press freedom in Bangladesh include the pressures exerted by vested

interest groups such as religious extremists, corporations, ad agencies, law enforcement

agencies, restrictive laws, and power elites. These factors have contributed to an increase

in self-censorship, a lack of comprehensive editorial policy, and a prevailing commercial and

feudalistic mindset among most owners.

12

Easily accessible and with billions of users, social and digital media platforms are prime tar-

gets for spreading mis-/disinformation and hate speech, which sometimes spark violence and

lead to communal strife and disharmony, vandalism, attacks and even killings. In this reality,

fact-checking has become indispensable for both the media and civil society groups. However,

fact checking is still nascent in Bangladesh and requires training journalists in techniques and

tactics for tackling mis-/disinformation. The IEA nds that neither journalists nor civil society

members have the adequate knowledge or skills to fact check and properly manage emerging

issues of mis-/disinformation, hate speech, online violence, and cyber security. The IEA also

INTERNEWS: INFORMATION ECOSYSTEM ASSESSMENT (IEA) 12

reveals disparities in access and exposure to digital and social media, among marginalized

communities, including PWDs, women and religious minorities. The following recommenda-

tions seek to bridge these gaps in Bangladesh’s mediascape.

Recommendations

Internews, through its partners or in collaboration with the government organizations

like the Press Institute Bangladesh or with the Universities can arrange nationwide

capacity building training and workshops on fact-checking, election reporting, investi-

gative reporting, etc. for both journalists and the civil society.

Internews through its partners should form a strong advocacy group with a view to

repeal the objectionable clauses of the draconian laws like the Digital Security Act 2018

which is expected to be transformed to Cyber Security Act, Ocial Secrets Act 1923,

and the Penal Code 1860 that hinder investigative journalism in Bangladesh.

Internews through its partners/relevant government departments can produce audio-

visual contents around election i.e., voting procedure, citizen rights, safety and security

measures taken by the election commission for women and PWDs and disseminate

through mainstream news and social and digital media platforms to foster awareness

among the targeted groups.

Youth should be trained in media literacy and fact-checking to become social media

leaders capable of organizing peers and combating mis-/disinformation.

Internews, through its partners/relevant government departments, can encourage paid

ads and audio-visual content on election rules, procedures, code of conduct, safety

measures for women, PWDs, and senior citizens through popular social media, TV

channels, and group communication platforms.

Internews should coordinate with NGOs to identify best practices around PWDs access

to information and media literacy to bridge the gap of their access to media content.

Internews through it partners should hold dialogues with the mobile network operators

and their regulatory bodies to improve the networking system, and minimize the network

charges for the PWDs, women and other marginalized people.

Facilitate the establishment of a sustainable youth network focused on developing

media literacy skills, particularly in social and digital media so that they can contribute

to combatting mis-/disinformation and maintain communal harmony.

13INTERNEWS: INFORMATION ECOSYSTEM ASSESSMENT (IEA)

Chapter One:

The Study Settings

Democracy in Bangladesh is undergoing a transformation. Over the last decade, democratic

backsliding has prompted many citizens to disengage from formal politics. Although the

survey data suggests that many Bangladeshis are satised with development and economic

trends, other evidence shows that the public has become disinterested in politics and is losing

faith in political parties. Between 1991 and 2008, voter turnout during national elections rose

steadily to 87%, but has precipitously declined since 2008. Although data on voter turnout is

not readily available, nonpartisan estimates for voter turnout in the 2014 and 2018 elections

did not surpass 50%. The Bangladesh public’s disengagement from politics and elections,

particularly among youth, women, and PWD — along with the weakness of reform in both

parties — perpetuates the status quo.

Women face specic barriers to participating and advancing in politics. Women’s families often

actively discourage them from becoming involved in politics, and Bangladesh’s violent and

corrupt politics deter many women from participating. In the last national election, 18 women

won in their constituencies and became the members of the Parliament.

13

In Bangladesh’s

conservative religious society, politics is viewed as a male domain unsuitable for women.

Women that win seats or join political parties often face challenges in rising to leadership

positions. Male leaders often doubt women’s political capacity and relegate women to minor

party positions. Together, these dynamics depress women’s interest and participation in

politics, which has produced a political system dominated by male voices and perspectives.

1.1 Conceptual Underpinning: What is the

Information Ecosystem Assessment?

In this context, Internews, an international non-prot organization, working to support and

amplify the voice local media internationally, felt the need to have empirical database, as part

of its advocacy with the Consortium for Elections and Political Process Strengthening (CEPPS)

and its partners. As part of the USAID-funded NAGORIK project, Internews conducted an IEA

in Bangladesh. The IEA focused on youth, women, and people with disabilities who have lim-

ited access to information, especially regarding political and electoral processes. By adopting

a human-centered approach, Internews aimed to understand how communities in dierent

INTERNEWS: INFORMATION ECOSYSTEM ASSESSMENT (IEA) 14

local contexts discover, exchange, value, trust, and disseminate information.

This IEA examines information access, needs, and ows, identifying trust and inuence

among diverse populations. The goal is to create transparent information environments that

empower citizens, bridge divides, foster community participation, and promote accountability.

The objective of the IEA is to help Internews and CEPPs partners to 1) establish a baseline

study to evaluate the potential change resulting from activities; 2) adapt existing strategies and

design new activities; 3) inform future media development strategy; and 4) enhance citizen

engagement in elections and political processes.

Leveraging the ndings, Internews, in collaboration with CEPPS, aims to improve media

capacity in reporting electoral issues, combating disinformation, and disseminating relevant

information to target communities. By doing so, they can better uphold the people’s voice

and strengthen democracy in Bangladesh, while designing interventions to meet information

needs and amplify marginalized voices in democracy and elections.

1.2 Research Objectives

The major objectives of the IEA include:

Mapping Bangladesh’s media landscape including legal frameworks, mobile and data

penetration, information providers, media outlets, ownership, funding, political inclina-

tion, and target audience.

Analyze the target groups media consumption habits and needs of the target group,

focusing on political and electoral processes, barriers to access information, and spe-

cic community information needs.

Identifying barriers to access to information among target groups identied by Internews,

for example mobile and/or internet penetration.

Pinpointing the dierences in needs and habits between the dierent target groups

mentioned above, in dierent areas in Bangladesh.

Contributing to developing key messages as part of media literacy campaigns.

Identifying potential actors that focus on serving the information needs of our target

groups. Identifying groups representing and working with youth, rural women and people

with disabilities, media outlets, local journalists, and information providers.

Mapping disinformation ows, analyze information delivery across diverse media

15INTERNEWS: INFORMATION ECOSYSTEM ASSESSMENT (IEA)

channels during elections, and examine how election-related disinformation spreads

online and oine.

Assessing community trust in media and communication channels, understanding their

impact on knowledge, attitudes, and practices, and identifying actors meeting the infor-

mation needs of target groups: youth, rural women, PWD, local journalists, and CSOs.

1.3 Study Methods and Materials

Internews’s Information Ecosystem Assessment (IEA) is designed to identify how informa-

tion ows through communities. Whether it is by word of mouth, through trusted community

leaders, local media, social media and/or other “info-mediaries,” the point of doing such

assessments is to identify the most eective formats and channels to use when designing

two-way communication strategies and feedback loops to meet the identied information

needs. Information Ecosystem Assessments recognize that media outlets are just one source

of information in communities, and so they seek to understand local information ecosystems

more broadly from the point of view of the information consumer. An IEA assesses all the

factors that govern information needs, access, sourcing, movement, uptake and impact in an

ecosystem in much greater depth.

The research methodology employs a combined qualitative and quantitative approach,

examining the supply and demand aspects of media relevant to Bangladesh’s elections. The

supply side analysis encompasses the national and community media landscape, evaluating

traditional and digital media, the media industry environment, legal regulations, and media

capabilities. In addition to assessing the capacity of media outlets, the study also focuses on

the community’s demand side of the information ecosystem, considering informal, cultural,

and social factors that impact information needs, access, sharing, trust, inuence, and infor-

mation literacy. These factors have the potential to disrupt or corrupt community information

ows through the spread of rumors, misinformation, and propaganda.

The research methodology applied is a combination of an interactive, action-oriented, do no

harm approach. Data collection followed ethical standards and allowed the equal participation

of male and female youth, adults, and people with disability, especially those in remote areas.

Initial data was collected through rigorous desk research, utilizing relevant literature, such as

media reports, research articles, the Preliminary Census Report 2022 from the Bangladesh

Bureau of Statistics, Bangladesh Labor Force Survey Reports, and relevant printed reports

and books. Findings from the desk review informed the research questions used informed

Key Informant Interviews (KII) and Focus Group Discussions (FGDs).

INTERNEWS: INFORMATION ECOSYSTEM ASSESSMENT (IEA) 16

Data was then gathered through a survey, FGD, and KII. The data collected facilitated eective

analysis, enabling the research team to triangulate and study the country’s information ow

and election-related information disorder. Internews and the partners jointly decided on the

criteria for the selection of the locations, considering the size of populations and the issues

around access to information. Internews, the IEA expert, and partners decided on the research

design and methodology together, putting into consideration both organizations’ experience

and history relevant to the local context and key issues.

1.4 Survey Data Collection

The team carried out a questionnaire survey. The survey adheres to a robust statistical stan-

dard

14

and includes a diverse sample size representing various regions, age groups, genders,

education and occupational backgrounds, income groups, and persons with disabilities. To

ensure diversity, the study team selected four divisions for assessment: Barishal, Chattogram,

Dhaka (the capital), and Mymensingh. Chattogram serves as the business capital and is the

second largest division, Mymensingh is the newest division with low literacy rates, and Barishal

is a coastal zone with diverse geographic, socio-economic, and demographic characteristics.

According to the preliminary report on the 2022 population and housing census by the

Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS), the selected divisions have a total of 497,73,981 women,

217,11,390 youth, and 12,541, 77 persons with disabilities (PWD). Women constitute 50% of

the total population, while the exact demographic information for youth (aged 18-29) is not

available but estimated to be around 22%. Persons with disabilities make up less than 2% of

the population. The sample population for the survey was 328 for women, 143 for youth, and

only 9 for PWD. To account for the small number of PWD, their population was adjusted by

allocating 10% of the total sample size from the women category, resulting in a total of 42.

After adjustment, the sample sizes for each category are as follows:

Two IEA data enumerators were captured during conducting sample surveys at Dighinala Upazila of

Khagrachari district under Chittagong Hill Tracts. Internews/Niloy Chakrobarty

17INTERNEWS: INFORMATION ECOSYSTEM ASSESSMENT (IEA)

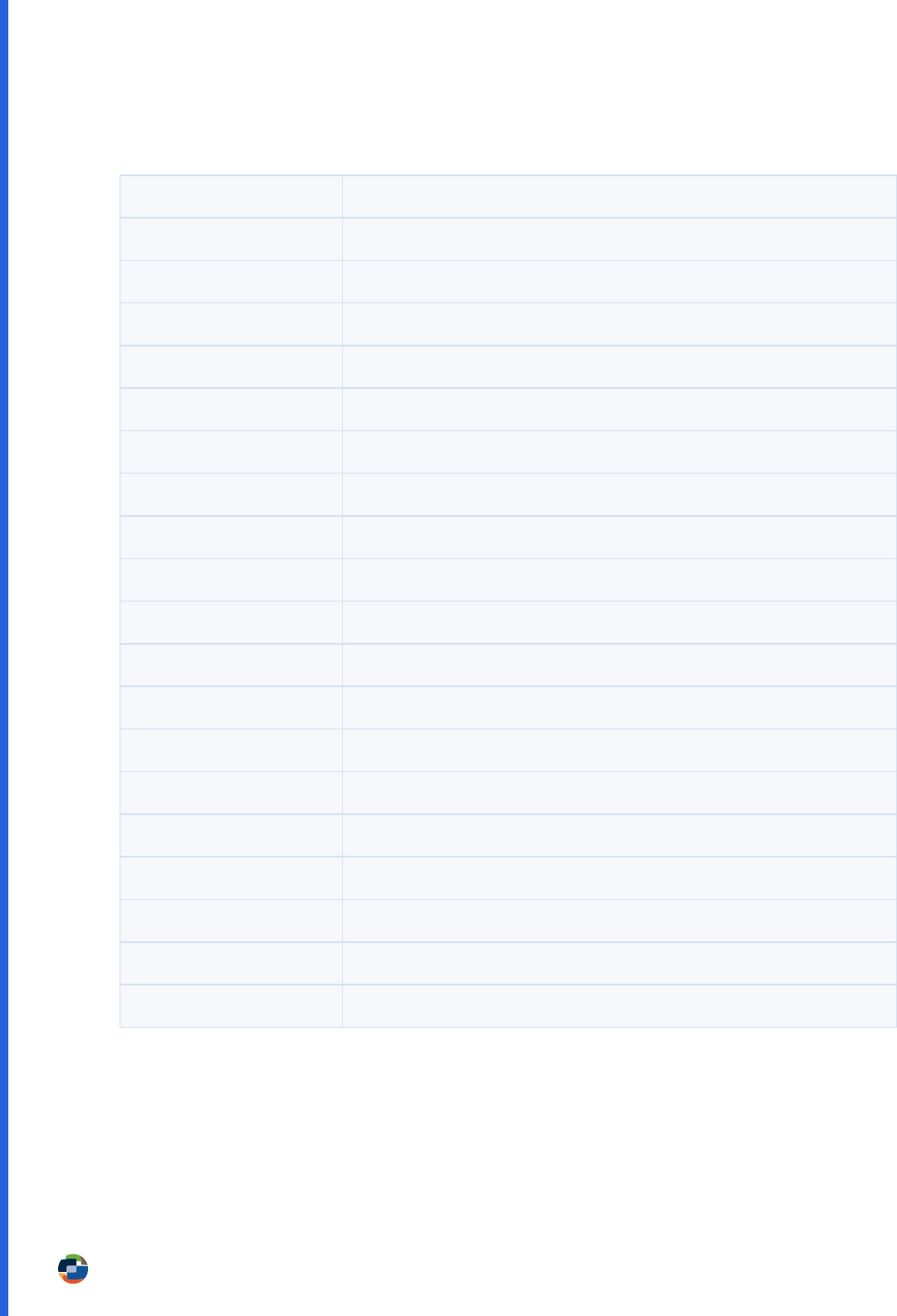

Table 1. Target group sample distribution

Planned Covered

TG Category Number Percent Number Percent

Women 295 61% 293 61%

Youth 143 30% 149 31%

Persons with disability (PWD) 42 9% 38 8%

Total 480 100.0 480 100.0

The survey utilized a multi-staged sampling approach, with sample sizes proportionate to each

location’s size. Starting at the national level, sampling progressed through divisions, districts,

sub-districts (upazilas), unions, and villages. Among the 480 respondents, the largest group

(211 or 44%) hailed from Dhaka division, followed by 164 (34%) from Chattogram division, 58

(12%) from Mymensingh division, and 47 (10%) from Barishal division. Each division had two

selected districts-the divisional district itself and another district considering the factors like

distance, urban and rural characteristics.

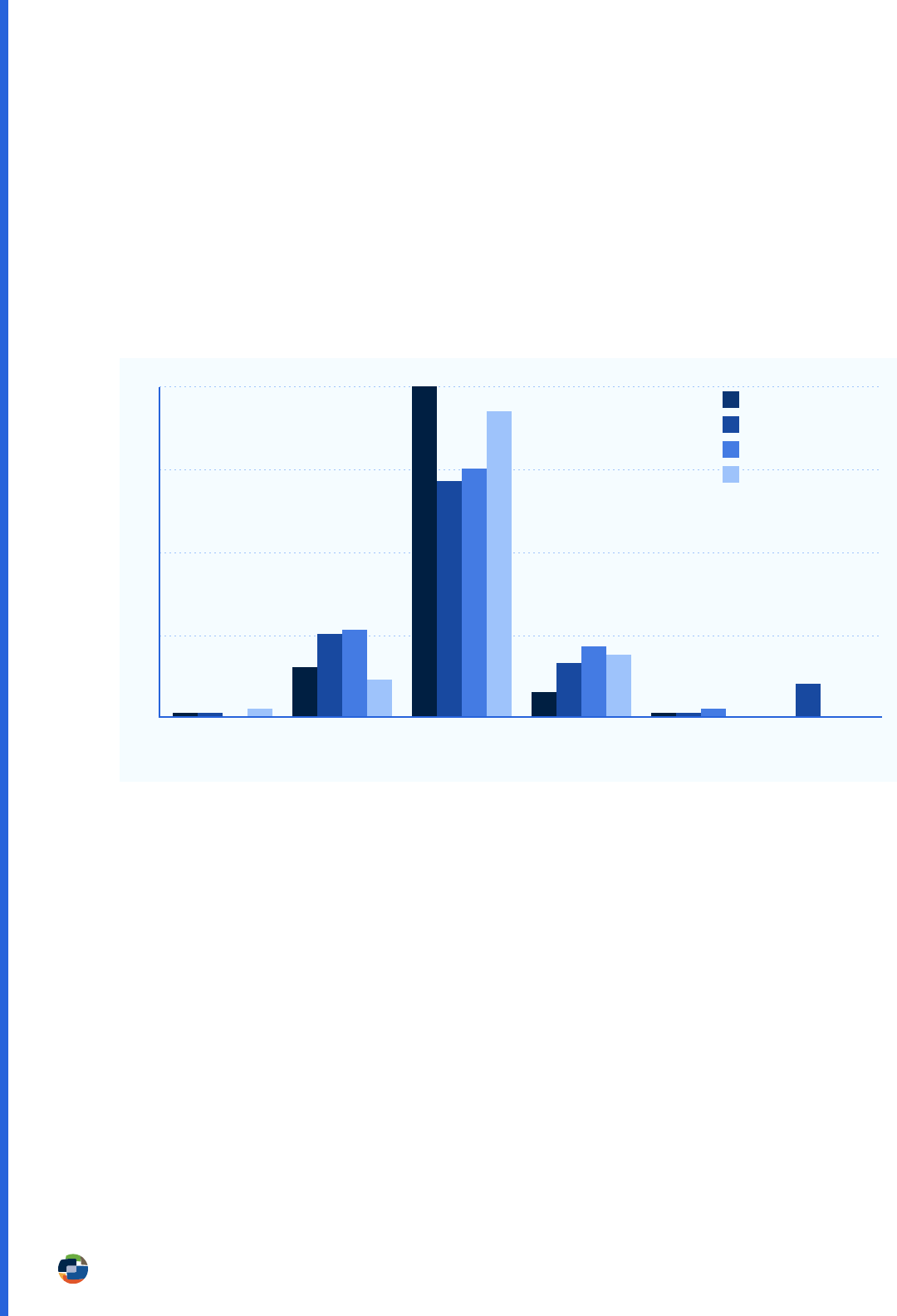

Figure 1. Distribution of sample as per division

Dhaka Chattogram Barishal Mymensingh

120

126

65

20

104

49

11

27

17

3

36

18

4

90

60

30

Woman

Youth

Person with disability

INTERNEWS: INFORMATION ECOSYSTEM ASSESSMENT (IEA) 18

1.5 Selection of Individual Respondents

For eective data collection, the research team faced the challenge of determining the start-

ing point for data collection in each primary sampling unit (PSU), which encompassed a large

area such as a village or ward. Enumerators were instructed to locate the center of the PSU

and visit every fth house to nd suitable respondents, following specic criteria outlined in

the data collection matrix. If the desired respondents were unavailable, the data collectors

proceeded to the next house. In urban areas with high population density, every 10th apart-

ment was surveyed to identify potential participants, especially in cities like Dhaka. To ensure

random sampling, PWDs were excluded, as they represented only 1.4% of the population in

Bangladesh. Locating PWDs posed a signicant challenge, and to overcome this, strategies

such as snowball sampling and reaching out to Union Parishad (UP) members and other

acquaintances were employed to identify suitable participants.

Figure 2. Distribution of FGD participants

1.6 Qualitative Approaches

To gain insights into the community’s media consumption habits, election-related information

needs, social media usage, media literacy, and perceptions of media accuracy and impartiality,

a comprehensive research approach was adopted. This included conducting 20 FGDs and

40 KIIs. While surveys were conducted in-person, some FGDs and KIIs took place virtually

through platforms like Zoom and Google Meet. The FGDs encompassed ve distinct groups:

youth, women, marginalized individuals, journalists, and CSOs, with each group having their

5

10

15

Youth Women Marginalized Journalist CEO

11

10 10 10 10 10

11 11

15 15

9 9

7

6

7 7

88

9

16

Dhaka Chattogram Barishal Mymensingh

19INTERNEWS: INFORMATION ECOSYSTEM ASSESSMENT (IEA)

own designated FGD. A total 199 participants, including 51 youth, 36 women, 35 marginalized

individuals, 39 journalists, and 38 CSO representatives participated in the FGDs (Figure 2).

KIIs were conducted with media experts, CSOs, Government ocials, and women activists,

ensuring a diverse range of perspectives were included in the research.

1.7 Data Gathering, Management

and Analysis

Data was gathered using a systematic random sampling procedure, employing pre-designed

questionnaires, and supervised by team leader and supervisors. Questionnaires, notes, and

audio recordings from FDGs and KIIs were securely stored and coded. The research team

diligently checked and veried the data, correcting any errors. SPSS (Statistical Package for

Social Science) was used for data analysis, determining frequency, percentage, and categorical

values. Graphs and charts were generated from numerical ndings for inclusion in the report.

Qualitative data that emerged from FGDs and KIIs was thematically analyzed. The team devel-

oped codes and identied dominant themes, relationships, and patterns through a systematic

review. The ndings were compared with existing literature and quantitative survey data to

ensure comprehensive analysis. The team manually labeled concepts and organized the data

to complement the survey ndings. Direct quotations were highlighted to ensure accurate

representation. The resulting insights were presented in the study report, supplemented, and

complemented by the questionnaire survey, providing a comprehensive understanding of the

research topic.

The American Association for Public Opinion Research has developed a set of comprehensive

ethical standards (revised in April 2021)

15

for carrying out social surveys of which a few key

principles were followed to deal with the personally identiable information (PII):

Recognizing the right of participants to be provided with honest and forthright information

about how personally identiable information that we collect from them will be used.

Recognizing the importance of preventing unintended disclosure of personally identi-

able information. We acted in accordance with all relevant best practices, laws, regu-

lations, and data owner rules governing the handling and storage of such information.

Avoiding disclosing any information that could be used alone or in combination with

other reasonably available information, to identify participants with their data (name,

position, and any identiable information), without participant’s permission.

INTERNEWS: INFORMATION ECOSYSTEM ASSESSMENT (IEA) 20

1.8 Study Limitations and Overcoming

Strategies

The study has some limitations of which the major ones include the followings:

The extreme cold delayed data collection in Chattogram’s hilly region. The research team

included enumerator from the hilly region having very good understanding of the local

weather and environment who visited respondents when the weather was favorable.

Diculty arose in nding suitable PWD and women respondents. Snowball sampling

procedure was a useful technique to reach the expected respondents. Moreover,

local opinion leaders and better-informed people supported to locate the expected

respondents.

Some FGD and KII participants expressed concern or declined to participate in the

study due to the sensitive nature of the subject. More motivation and persuasion were

needed along with assurance of maintaining their identity as condential.

Data collectors faced rejection and were barred from entering certain areas. Local

contact persons helped to provide access to them.

Being unique and diverse in nature, the study should have covered more samples from

more regions for better capturing data in a more comprehensive way.

The subject of the study is very new in Bangladesh with people generally lacking

understanding, particularly regarding certain terms and topics like mis-/disinformation,

fact-check, etc.

The survey was conducted in four divisions on 480 participants. Including more divisions

and sample population would facilitate more comprehensive data. However, qualitative

data were supportive to understand the situation eectively.

21INTERNEWS: INFORMATION ECOSYSTEM ASSESSMENT (IEA)

Chapter Two: IEA Findings

2.1 Bangladesh Mediascape

Bangladesh’s media landscape has witnessed a signicant shift towards private management,

resulting in a predominance of inuential outlets owned by politically aliated corporations.

While the country enjoys a wealth of news media, it is primarily urban-centered, male-dom-

inated, and controlled by corporate entities inuenced by the power elites. This transfer of

media ownership took place under various political administrations, enabling corporate elites

to acquire licenses and consolidate control. Bangladesh has four state-owned television

channels, 45 private television channels, 28 FM and 32 community radio stations, 1,248 daily

newspapers, and more than 100 online news portals.

16

According to the Department of Film and Publication’s report on enlisted media (dated 08

September 2022), Chattogram metropolitan city has three English dailies and 16 Bangla dailies,

along with one state-run Bangladesh Radio and Television and a sub-station of Channel 24,

one of the news-based corporate owned television stations. In contrast, Dhaka has 37 English

dailies and 217 Bangla dailies, along with one state-run radio and three TV channels, and 45

corporate owned television stations. It is note-worthy that the community radio stations are

primarily supported by the donors and development partners.

17

Although the media sector

is predominantly male, there has been a recent increase in visibility of female journalists in

satellite TV channels and newspapers.

18

In Bangladesh, TV channels can be classied into two types: general entertainment channels

(GEC) with a focus on general entertainment and news-based channels featuring hourly news

bulletins. Among the 45 satellite TV channels, 35 are in operation currently, of which 21 are

mixed and nine are news-based. Additionally, there are ve specialized channels dedicated to

music, kids’ issues, infotainment, business and sports.

19

These channels are owned by inu-

ential corporate entities. For instance, the news-based channel ‘Independent TV’ is owned by

the Beximco Group, while the ‘News24’ channel is owned by the Bashundhara Group. Similarly,

leading newspapers and FM radio stations are also owned by corporations. For example, the

Transcom Group, known for its business interventions in electronics and food and beverage,

owns popular Bangla and English dailies like ‘Prothom Alo’ and ‘Daily Star,’ as well as ‘ABC’

radio; the Hameem Group, specializing in textiles and clothing, owns the prominent newspaper

‘Samakal’ and news-based ‘Channel24;’ and the Jamuna Group, involved in textiles, chemicals,

and constructions, runs the leading daily ‘Jugantor’ and ‘Jamuna TV.’

20

Media academics and

INTERNEWS: INFORMATION ECOSYSTEM ASSESSMENT (IEA) 22

researchers criticize corporate ownership of media houses for exerting signicant control

over content, neglecting coverage of corporate malpractices and power elite corruption, and

protecting vested interest groups through self-censorship.

21 22

2.2 Media Regulatory and

Policy Frameworks

The media landscape in Bangladesh is characterized by strict laws and regulations that are seen

as oppressive and restrictive to freedom of expression. The existing regulatory framework for

radio and television is guided by out-dated laws and policies that fail to adapt to the evolving

media landscape. Several laws, such as The Telegraph Act (1885), The Wireless Telegraphy

Act (1933), and the Bangladesh Telecommunications Regulatory Commission Act 2001, govern

the radio and television industry. Print and broadcast media content is regulated by a diverse

set of laws, including censorship codes and provisions outlined in legislations such as The

Penal Code (1860), The Code of Criminal Procedure (1898), The Contempt of Court Act (1926),

and the Printing Presses and Publications (Declaration and Registration) Act passed in 1973,

which regulates newspaper and book publication. Additionally, the Bangladesh Television,

Film Censor Guidelines, and Rules (1985) dictate content regulations for television and lms.

23

However, the management and operations of satellite TV channels, online news portals, and

social and digital media platforms lack comprehensive legislation and policies. Despite some

pending laws and policies i.e., Online Mass Media Policy (draft),

24

there is currently no com-

prehensive framework to address these new platforms.

The Ministry of Information, in collaboration with Bangladesh Telecommunications Regulatory

Commission (BTRC) holds the authority for licensing and frequency control. The BTRC Act

2001 provides guidelines for spectrum allocation to licensed operators for establishing TV

stations.

25

FM radio broadcasting licenses are issued by the Ministry of Information, and

frequency assignments follow the National Frequency Allocation Plan. The government intro-

duced the Community Radio Installation, Transmission, and Operation Guideline in 2008 to

facilitate localized information services. Terrestrial broadcasting is exclusively designated for

Bangladesh Television (BTV), a state-owned entity, while private TV channels rely on satellite

broadcasting.

26

Private radio stations operate through FM broadcasting licenses issued by

the Ministry of Information.

The Digital Security Act (DSA) 2018 is widely seen as a signicant threat to freedom of

23INTERNEWS: INFORMATION ECOSYSTEM ASSESSMENT (IEA)

expression due to its excessive empowerment of law-enforcing agencies. Section 43 of the act

allows an investigation ocer to conduct searches, seizures, and arrests without a warrant.

It states that if a police ocer believes that an oense under the act is being committed, or if

evidence is at risk of being lost, destroyed, altered, or made unavailable, they may, upon record

-

ing their belief in writing, take the following measures: (a) enter and search the place, using

necessary measures if obstructed; (b) seize computers, computer systems, networks, data, or

other materials used in the oense; (c) search the body of any person present; and (d) arrest

any person suspected of committing an oense under the act.

27

Consequently, investigative

journalism has faced signicant limitations due to the frequent harassment and punishment

of journalists under the DSA, targeting reports disliked by the authorities or the masterminds.

The Right to Information Act 2009

28

is the result of a long-standing civil society campaign

advocating for the free ow of information to the public. This act stands out from other laws

as it empowers the people to hold authorities accountable by allowing them to apply this law

against the state. It signies a paradigm shift, granting individuals the right to access infor-

mation and ensuring transparency. While the act recognizes the citizen’s right to information,

certain exceptions exist, such as information pertaining to foreign policy or condential infor-

mation received from foreign governments. Additionally, state-run institutions, particularly law

enforcement agencies, are exempted from providing information upon request.

2.3 Community Access and Exposure

to Media

Access to information is highly inuenced by, among others, literacy rate, access to electricity,

access to internet connectivity, and ownership of the devices. Findings from the literature

review shows, Bangladesh has a diverse population of 159,453,001 (July 2018 est.) residing in

rural, semi-urban, and urban areas, with 36.6% living in urban regions.

29

So, the demographic

structure suggests two broad categories of media audiences in the country. There are 80

million adults (age 15+) audiences against 80 million in the urban areas, primarily Dhaka and

Chattogram.

30

The adult literacy rate in Bangladesh was reported at 74% in 2018, with 82% of

urban and 67% of rural populations being literate according to Bangladesh Statistics 2019.

31

However, the multiple indicator cluster survey in 2019 revealed a higher literacy rate of 89%

among individuals aged 15-24.

32

In terms of access to electricity, the IEA survey nds a substantial 92% of respondents reported

having an electricity connection, highlighting widespread availability. Regarding internet

INTERNEWS: INFORMATION ECOSYSTEM ASSESSMENT (IEA) 24

connectivity, 59% of youth respondents reported having an internet connection, whereas 50%

of women and 34% of PWDs had access to the internet, indicating a lower rate among PWDs.

Of the total sample population, 67% were from the rural area while the remaining 33% were

from the urban areas. Given this context, 76% urban respondents possess internet connection

while 39% rural respondents possess the same.

Figure 3.1. Ownership of Electricity and Internet by groups

Figure 3.2.

Ownership of Laptop and Desk Computer by groups

Radio, desktop computers, and laptops were less commonly owned devices accounting for less

than 10% of all responses, suggesting that they are less frequently used for accessing information

10

20

30

31%

16%

19%

5% 5%

11%

Youth Women

Person with

disability

Laptop

Desktop Computer

82%

3%

77%

3%

5%

79%

20

40

60

80

Youth Women

Person with

disability

Television Radio

Figure 3.3.

Ownership of Television and Radio by groups

Youth Women Person with disability

20

40

60

80

100

Electricity Internet

59%

92%

50%

34%

87%

97%

25INTERNEWS: INFORMATION ECOSYSTEM ASSESSMENT (IEA)

compared to television and mobile phones.

In terms of communication and media-re-

lated devices, the survey found that 79%

of respondents (on average) owned a TV

set, emphasizing its prevalence among

the population. The smart phones reached

are owned by more than 80% respondents

against the use of button mobile sets by

77.6 % respondents. In terms of possess-

ing smart phones, the PWDs are the most

laggards while the youth are in advanced

position.

Among daily users, as shown in (Annex 2: Table 13) Television channels emerge as the most

utilized media, with 270 responses (56%). This is in line with the ndings from literature review.

According to estimates from the cable operators’ association and private channels association,

the cable network in Bangladesh has reached approximately 84% of households.

33

A national

media survey indicated that televisions had 80% audiences in 2017.

34

Findings from the ‘News Literacy Survey’ conducted by MRDI in 2020 reveal that television

channels serve as the primary source of news for 75% of the population while digital news

media (such as Facebook, online news portals, and other social media platforms) account for

16% of the audience’s primary news sources. Television channels have a signicant advan-

tage in terms of viewership due to their audio-visual nature. Studies and observations suggest

that both male and female viewers opt for TV news and programs, while middle-aged literate

audiences primarily rely on newspapers. This medium eectively communicates messages

to individuals with limited or no formal education. With approximately one-fourth of the pop-

ulation being illiterate, newspapers hold little relevance for them. Instead, they heavily rely on

television for information, education, and entertainment.

Digital media is the second most accessed media. The ndings from the FGDs and KIIs indi-

cate a rapid shift in media consumption habits, with audiences increasingly transitioning from

traditional news media like newspapers, radio, and TV to online-based social media platforms

and news portals. As smartphones become more accessible, users are connecting their

devices to the internet for news, information, and entertainment. Over the last two decades,

the government’s ‘Digital Bangladesh’ campaign has driven media expansion, particularly

Youth Women

Person with

disability

20

100

40

60

80

Smart Phone Button Phone

97%

71%

73%

89%

82%

63%

Figure 3.4. Ownership of smart phones and button

phones by groups

INTERNEWS: INFORMATION ECOSYSTEM ASSESSMENT (IEA) 26

in digital and social media. Social and digital media have experienced spontaneous growth

primarily driven by individual users and the increasing availability of smartphones.

Kemp, S. (13 February 2023) citing GSMA intelligence reports, there were about 180 million

cellular mobile connections in Bangladesh at the start of 2023 and about 45 million social

media users in January 2023. It is also mentioned that there were 66.94 millioninternet users

in Bangladesh in January 2023. Kemp’s analysis shows that internet users in Bangladesh

increased by 691 thousand (+1.0%) between 2022 and 2023.

35

Today, almost all the leading newspapers, TV channels, and radio stations have web portals,

Facebook pages, Twitter accounts and YouTube channels. Some newspapers outside of the

capital have their online news portals and e-versions too. This popularity of digital and social

media is particularly true in big cities like Dhaka and Chattogram. As shown in (Annex 2: Table

13.b.) online news portals are used signicantly more in Dhaka than other divisions at 54%.

While Chattogram has the lowest TV use at 74% but the highest social media use at 63%, while

the others average 53%. According to a male key informant in Chattogram, there is a decline

in people’s interest in reading newspapers due to the growing availability of internet-based

news media.

IEA survey nds that, young populations heavily depend on digital and social media platforms

for news and entertainment. The MRDI survey report highlights that “young adults were almost

70% more likely to choose digital news sources. This is also likely because most smartphones

owners are young adults. As IEA survey nds, a signicant 85% of respondents possessed

smartphones, while 74% had feature phones in addition to smartphones. However, when

analyzing smartphone ownership, the survey revealed that youth had an impressive 97%

ownership rate, 82% of women owned smartphones, and PWDs lagged at 63% (Figure 3.4).

As shown in (Annex 2: Table 13), the use of various media and communication channels/

platforms by respondents is depicted, highlighting the extent of their exposure. Among daily

users, as shown in (Annex 2: Table 13) social media is the second largest media utilized, with

217 responses (45%), while interpersonal communication channels/platforms and online news

portals garner 170 responses (35%) and 144 responses (30%) respectively. Facebook is the

most used social media platform in Bangladesh, with 68% of respondents indicating its usage.

YouTube follows closely behind, with 65% of respondents using the platform. WhatsApp and

Imo are utilized by 36% of respondents, while TikTok is used by 27%. In contrast, the usage

of Instagram and Twitter is relatively low, with only 18% and 13.5% of respondents using

these platforms respectively. Additionally, 29% of respondents reported using news apps or

27INTERNEWS: INFORMATION ECOSYSTEM ASSESSMENT (IEA)

websites (Annex 2: Table 30).

With approximately one-fourth of the population being illiterate, newspapers hold little rele-

vance for them. Newspapers serve 8% of the audience, while the radio caters to only 0.3%

as their main news sources. Studies and observations suggest that both male and female

viewers opt for TV news and programs, while middle-aged literate audiences primarily rely on

newspapers. Radio, being a traditional medium, is experiencing a decline in listenership daily,

largely due to the popularity of television channels and the emergence of social and digital

media platforms. As shown in (Annex 2: Table 13), IEA survey nds daily newspapers and radio

received 37 (8%) and 8 responses (≤ 2%) respectively, while daily news magazines receive

the least attention among daily users, with only ve responses (1%). However, as shown in

(Annex 2: Table 13.b.) in remote and hilly area like Mymensingh, where satellite channels are

less accessible to many due to limited television and cable network availability, the newspa-

pers are more preferred as 36% read the same. One male KII noted in Chattogram hill tract

region, “One who has no internet access but [is literate] still tries to get printed newspapers

if available especially in the hilly areas.”

Another factor inuencing access to media and information are community mobility and soci-

etal acceptance. KIIs conducted with gender-diverse populations revealed that transgender

individuals face diculties in accessing information due to societal stigma and discrimination.

However, the study found that interpersonal and group interactions are eective channels for

information exchange within this community. FGD ndings from marginalized communities,

including religious and occupational minorities, also indicated challenges in accessing infor-

mation. Women and the PWDs are especially lagging in terms of using daily newspapers, online

news portals and the social media platforms. The PWDs are more dependent on interpersonal

communication channels as almost 74% responses reveal their stance while this channel is

preferred by 55.7% youth and 59.7% women (Annex 2: Table 13.a.). Additionally, IEA survey

also nds that interpersonal communication is most popular in Barishal at 83%, compared to

an average of 58% across other divisions (Annex 2: Table 13.b.). Mahmud (2008) states that the

lifestyles of Barishal people are somewhat dierent due to their river-based communication.

Naturally, the people in this region prefer communal activities, like fairs and boatrace. One of

the KIIs, a male teacher from the Department of Journalism at Barishal University, expressed

that these factors, along with their local hospitality and communal approach to responding to

natural disasters, contribute to fostering an environment reliant on interpersonal communication.

INTERNEWS: INFORMATION ECOSYSTEM ASSESSMENT (IEA) 28

2.4 Barriers to Accessing Media

In Bangladesh, people encounter pragmatic barriers that hinder their access to various forms

of media. These barriers limit audience exposure and can encompass diverse aspects. The

IEA survey reveals that most respondents face barriers to watching television, accessing social

media content and online news portals. When it comes to barriers to media access, the sur-

vey found that 62% of respondents cited poor or lack of internet network as a major obstacle.

Financial insolvency was mentioned by 21% of respondents, while 20% faced challenges

related to poor infrastructure and road communication, and more than 16% of respondents

attributed their diculties to the remoteness of their locality (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Percentage distribution of multiple responses on the types of barriers to access to the media

2.5 Barriers to information during

COVID-19

During COVID-19 pandemic from 2020 to 2022, Bangladesh faced signicant challenges in the

coverage and dissemination of information. The country ranked fth globally in terms of COVID-

19-related deaths among journalists, as reported by the Press Emblem Campaign (PEC 2020).

By November 2020, over a thousand journalists in Bangladesh were infected with COVID-19,

and 37 had tragically passed away (Anik, Dhaka Tribune, November 9th, 2020).

36

As a result

of the pandemic, people increasingly relied on television and online news portals for informa-

tion and entertainment, leading to a decline in demand for printed newspapers. However, as

the reliance on internet-based communication platforms increased, people faced diculties

Poor or lack of internet network

Financial limitation

Poor infrastructure and road communication

Remote area

No response

Others [Load shedding, unavailable]

Illiteracy

Socio-cultural and religious impediment

Aural-visual imparity/problem

61.9%

20.8%

19.6%

16.7%

17.9%

10%

5.8%

5.2%

1.5%

29INTERNEWS: INFORMATION ECOSYSTEM ASSESSMENT (IEA)

obtaining information due to network congestion. Women in Bangladesh, as identied by KII

and FGD respondents, have limited opportunities to seek information independently due to

their traditional household responsibilities. Instead, they heavily rely on family members, such

as fathers, husbands, brothers, and relatives, for information, particularly on matters related

to elections and politics. KII also highlighted that PWDs face challenges in media literacy and

require specic techniques to access media content. Depending on the type of disability, for

instance, individuals with blurred vision or blindness rely on audio formats as they cannot

read newspapers.

2.6 Preferred Communication Channels/

Media on Elections and Politics

Community use of media to get information on election

and politics

When it comes to obtaining political and election-related information, television emerged as

the primary source for over 75% of respondents, followed by interpersonal communication

channels, which is the most trusted source and 68% rely on. Social media platforms have

gained popularity, with about 54% of respondents using them. In contrast, more than 38% of

respondents turn to online news portals, while approximately 14% still rely on printed daily

newspapers (Figure 5). These ndings closely align with recent studies conducted by MRDI,

37

emphasizing the evolving media landscape and the increasing inuence of television, social

media, and online platforms in providing information on politics and elections.

Figure 5. Percentage distribution of multiple responses on the use of media/channels to get information

on politics and election

Television channels

Interpersonal communication channels

Social media

Online news portals

Daily newspapers (print)

Other [Miking, Poster]

News magazine (print)

Radio

No response

75.8%

68.3%

53.8%

38.5%

13.8%

4.2%

1.5%

1.2%

0.6%

INTERNEWS: INFORMATION ECOSYSTEM ASSESSMENT (IEA) 30

When it comes to interpersonal communication, 77% of respondents trust family members,

friends, and relatives as the most reliable sources for political and electoral news. Community

opinion leaders were mentioned by 67% of respondents, followed by elected representatives,

government authorities, and civil society organizations (Annex 2: Table 5).

2.7 Community’s Preferred Formats of

Media Content

Most respondents, 82.5%, expressed a preference for audio-visual content such as short lms,

dramas, and documentaries. KIIs of local journalists conrmed that people found audio-visual

content easily understandable and entertaining. Additionally, 42% of respondents favored

narrative written formats like reports, articles, and editorials. The data also revealed that 27%

of respondents preferred interview and dialogue-based content, indicating a growing interest

in conversational media formats like debate, dialogue, and podcasts etc. featuring insights

from experts. Additionally, 11% favored visual content, suggesting that visuals alone may not

fully engage audiences. These ndings reect changing audience preferences, with audio-vi-

sual formats being popular. However, written content, interview/dialogue-based content, and

cultural/traditional media content continue to hold value in the industry (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Percentage distribution of multiple responses on preferred formats of media contents

In addition to traditional and new media, 32% of respondents were drawn to folk/indigenous

media content, such as stage dramas, folk songs, and group performances. Bangladesh

possesses a rich cultural heritage of folk and indigenous media, which continues to play

a signicant role in rural entertainment. Folk media forms like jaree gann, sari gann, kobir

Audio-visual

Narrative written/text

Folk/indigenous media

Interview and dialogue

Animation and motion graphics

Others: [Reality show, Web series]

Graphics, pictorials and sketch form

No response

82.5%

68.3%

32.3%

41.9%

27.3%

11%

9.4%

3.8%

1.9%

31INTERNEWS: INFORMATION ECOSYSTEM ASSESSMENT (IEA)

lorai, puppet shows, and street and stage dramas like ganbhira, vatiali, and gazir geet enjoy

popularity in various regions. Despite facing competition from television, social media, and

digital platforms, some folk media, like Gambhira, a regional performing song from Rajshahi,

still resonate with the people nationwide. A trend observed is the dissemination of folk media

content through television, social media, and digital platforms, employing a “media mix” and

“media integration approach” to distribute information in an “infotainment” format.

2.8 Perceptions on Media’s Role in

Election, Accuracy and Impartiality

2.8.a The Media’s Role in Elections

Media’s signicant role in raising awareness about civil rights and related issues has been

widely acknowledged. According to the survey, 59% of respondents believe that fair cover-

age of political news aids in better understanding of their concerns and enables informed

choices while selecting representatives. ‘Fair media coverage’ is described by FGD and KII

respondents as accurate, balanced, and impartial presentation of political events, issues, and

election aairs (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Percentage distribution of the responses on media’s fair coverage to help voters in

selecting candidates

The role of media in inuencing voter decisions is a topic of concern. According to the KII

ndings, media outlets often promote the image of their favored candidates, which raises

questions about their neutrality. One of the male key informants, a civil society member in

Chattogram hill tracts opine, “No one speaks due to the regional political inuence and the

Fully agree Agree Neither agree

nor disagree

Disagree Fully disagree

No answer

43%

27%

11%

2% 2%

10

20

30

27%

INTERNEWS: INFORMATION ECOSYSTEM ASSESSMENT (IEA) 32

TV, radio and online news portals aren’t useful...There blows a wind of voting for a particular

candidate and the mass people follow and oat on that stream of wind...Personal assessment

plays more role than the media in taking decision to vote.”

The IEA reveals signicant gaps in media coverage of politics and election. One of the senior

male journalist leaders in Dhaka said, “Media don’t adequately investigate the process and

preparation of national election, role of the election commission, inuence of the power elites

in election, use of black money to inuence the voters, role of the state authorizes and so on.”

2.8.b Overall Perceptions of Media Accuracy

Overall, 69% of respondents perceive the Bangladesh media as ‘somewhat accurate,’ while

15% consider it ‘accurate’ (Annex 2: Table 26). On par with the overall ndings, youth (76.5%),

women (66%), and PWDs (69%) all agreed that the media stories are ‘somewhat accurate,’

while only 1% of youth and women, and 3% of PWD considered news stories to be ‘very accu-

rate’ (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Percentage distribution on perception of the media accuracy by the types of respondents

2.8.c Perceptions of Media by Division

When examining respondents by division, in Dhaka, about 80% considered the media to be

‘somewhat accurate,’ while in Chattogram and Barishal, 57% and 60% of respondents held the

same perception, respectively. In Mymensingh, 74% reported a similar view of media accuracy.

80

60

40

20

Very accurate Accurate Somewhat

accurate

Inaccurate Very

inaccurate

No response

Youth (n=149)

Woman (n=293)

Person with disability (n=38)

1 10.7

3 3 3

10

19

76.5

66

69

11 11

9

0.3 0.5

8 8

33INTERNEWS: INFORMATION ECOSYSTEM ASSESSMENT (IEA)

Notably, respondents in Barishal were more critical, with 17% considering the media ‘inaccu-

rate,’ compared to roughly 15%, 13%, and 6% of respondents in Mymensingh, Chattogram, and

Dhaka, respectively (Figure 9). These ndings suggest that media outlets outside of Dhaka and

Chattogram are perceived as more inaccurate. It is worth noting that Dhaka and Chattogram,

being the two largest cities, house most mainstream daily newspapers, local newspapers, TV

stations, and online portals, which are developed to a higher professional standard compared

to those in the outskirts.

Figure 9. Percentage distribution on division wise perception of the respondents on the accuracy of news

media

The FGD and KII ndings highlight the signicance of professional journalistic practice for

media accuracy, emphasizing factors such as skilled journalists, proper news coverage, and a

conducive working environment. One of the male key informants, who is a government ocial

in Dhaka expressed: “Inaccurate reports, especially on the election, are the products of some

untrained journalists who even can’t interview an election commissioner properly due to the

dearth of knowledge on election-related rules, laws, and regulations, the role of the election

commission and other administrative organs during the election.”

Interestingly, unlike other professions that require specialized knowledge and formal clearance,

the KII ndings in Dhaka indicate that the media in Bangladesh lacks a policy to exclusively

recruit journalists with academic backgrounds in media, communication, and journalism

which causes fundamental gaps in understanding of journalistic ethics, principles, style, and

structures.

80

60

40

20

Very accurate Accurate Somewhat

accurate

Inaccurate Very

inaccurate

No response

Dhaka (n=211)

Chattogram (n=164)

Barishal (n=47)

Mymensingh (n=58)

1 1

0 0 0 0 0

2

1 1

2

12

6

13

17

15

20

21

9

8

80

74

60

57

INTERNEWS: INFORMATION ECOSYSTEM ASSESSMENT (IEA) 34

2.8.d Media Impartiality

According to the ndings from

KIIs and FGDs, the media mostly

demonstrate impartiality when

covering non-political events

and issues. When it comes to

political and electoral news,

bias becomes evident, as KII

respondents acknowledge that

media coverage during elec-

tions tends to favor preferred

candidates, while media spon-

sorship hinders impartiality.

A senior male journalist in Chattogram laments, “Impartial journalism is not possible due to

media ownership. Journalists, despite their intentions, are unable to expose corporate mal-

practices. Media lack the freedom to exercise self-censorship and often present only one side

of the story.” Another KII revealed, “Media in Bangladesh prioritize protecting the corporate

interests of specic individuals.”

Figure 11. Percentage distribution on perception of news media’s impartiality by types of respondents

This is further reected in the IEA survey. In terms of presenting the political and electoral

news reports, 76% of respondents, perceived the Bangladesh media as ‘somewhat impartial’

while 10% viewed as ‘impartial,’ and 11% as ‘not impartial’ (Figure 10). This aggregation was

Figure 10. Respondent’s perception of media impartiality

Highly impartial

Impartial

Somewhat impartial

Not impartial

Not impartial at all

No response

0.4

2.7

10.6

0.8

9.6

75.8%

No response

Not impartial at all

Not impartial

Somewhat impartial

Impartial

Highly impartial

Youth (n=149) Woman (n=293) Person with disability (n=38)

35INTERNEWS: INFORMATION ECOSYSTEM ASSESSMENT (IEA)

reected by youth, women and PWD, with youth leaning more towards slightly impartial at

13% and women seeing the news as more impartial (Figure 10 & 11).

The lack of impartiality is also manifested in the coverage of political leaders or electoral can-

didates. In line with the ndings on respondent’s perception of media impartiality, IEA survey

nds, 68% of respondents believe that news media in Bangladesh do not provide equal cov-

erage to political leaders or electoral candidates. Only 11% feel that the coverage is unbiased,

while 21% are unsure or don’t have an opinion on the matter (Annex 2, table 23). The reasons

behind this disparity in news media coverage of political candidates vary. Respondents cited

both pressures from vested interest groups and the political aliation of the news media as

the primary factors, each receiving over 72% of responses. Additionally, concerns about losing

revenues were mentioned by over 20% of respondents, while other reasons were mentioned

by more than six% of respondents. (Figure 12).

Figure 12. Percentage distribution of the multiple responses on the reasons of perception of media’s unequal

coverage

2.8.e Media Challenges

The Reporters without Borders World Press Freedom Index, shows that Bangladesh’s position

is declining in terms of press freedom, dropping from a ranking of 150th in 2019 (out of 180

countries) to 163rd in 2023.

38

(Figure 13).

Media freedom in Bangladesh has greatly diminished due to repressive government laws and

policies, eroding democratic governance following a prolonged one-party rule. Technological

shifts, the growth of social and digital media and increased corporate ownership have also

25

50

75

72.2%

20.2%

6.1%

72.5%

Political aiation

of the news media

Pressures from vested

interest groups

Apprehension of

losing revenues

Others

INTERNEWS: INFORMATION ECOSYSTEM ASSESSMENT (IEA) 36

restricted the news media sector.

Journalists and media profession-

al’s eld face numerous profes-

sional risks, including oppressive

media laws, bureaucratic domi-

nance, and vindictive behavior

from law enforcement agencies,

power elites, and vested interest

groups. Various factors, including

journalist harassment, attacks,