Business Roundtable is an association of more than 200 chief executive ocers (CEOs) of America’s leading companies, representing every

sector of the U.S. economy. Business Roundtable CEOs lead U.S.-based companies that support one in four American jobs and almost a

quarter of U.S. GDP. Through CEO-led policy committees, Business Roundtable members develop and advocate directly for policies to

promote a thriving U.S. economy and expanded opportunity for all Americans. Learn more at BusinessRoundtable.org.

Copyright © 2023 by Business Roundtable

Lessons From Canada and Australia

U.S. Immigration Policy

July 2023

1 | U.S. Immigration Policy: Lessons From Canada and Australia

Contents

Executive Summary

02

I. Introduction

09

II. The Business Case for Robust Legal Immigration

11

III. What Can Be Learned From Canadian and Australian Systems

13

Retaining International Students Postgraduation

13

Permitting the Spouses of Visa Holders to Work

17

No Per-Country Limits for Permanent Residence

19

No Annual Limits, Quicker Processing and Greater Transparency for

High-Skilled Temporary Work Visas

22

Providing a Role for States, Provinces or Regional Areas

27

Dealing With an Unfavorable Demographic Future

30

Issuing a Startup Visa

32

IV. An Assessment of the Applicability of Canadian and Australian Point Systems

to the United States

35

V. Policy Recommendations

43

VI. Conclusion

45

Endnotes

46

2 | U.S. Immigration Policy: Lessons From Canada and Australia

Executive Summary

The main findings of the research include the following:

• International students are a key source of talent for companies in advanced Western economies.

Between 2010 and 2020, the number of international students in Canada increased 135 percent,

compared to a 31 percent rise in international students in the United States during the same period.

Since 2016, Canadian universities have attracted Indian-born students in large numbers who see

Immigrants built the United States and are central to its future. America has a successful tradition as

a nation of immigrants, and U.S. immigration policy should reflect that important fact. Higher levels

of immigration would enhance economic growth and make dealing with the aging of America’s

workforce and population easier. Thus, the United States needs an immigration system that admits

more immigrants and temporary visa holders at different skill levels to fill gaps in the labor market and

fuel the country’s growth and a prosperous future.

Examining the immigration policies of Canada and Australia, Business Roundtable finds that U.S.

immigration policy puts our nation at a competitive disadvantage. Both Canada and Australia: make

it easier for international students and the spouses of visa holders to work than under U.S. policy;

impose no annual limits on high-skilled temporary visas, which allows their systems to adapt to labor

market needs; provide for much greater speed and transparency in processing business visas than the

United States; and do a better job than the United States in addressing the demographic challenges of

aging populations. Canada and Australia also use point-based systems that have been cited by some

in the United States as a direction for its immigration system, but a closer examination presents many

cautions for policymakers in considering a point-based system for the United States.

This report is a follow-up to the 2015 Business Roundtable State of Immigration report, which

examined the U.S. immigration system in relation to other advanced economies to determine which

nations maintained “the best immigration policies to promote economic growth.” In that report,

Business Roundtable found that the United States ranked 9th out of the 10 countries analyzed, behind

Germany, Australia, Singapore and other nations.

For this analysis, Business Roundtable analyzed Canadian and Australian immigration laws and

interviewed individuals with practical knowledge of how the immigration systems of the two countries

work. The goal of the research was to determine what lessons policymakers could gain from Canada

and Australia that could best be applied to the U.S. immigration system.

3 | U.S. Immigration Policy: Lessons From Canada and Australia

Canada oering an easier path from student to temporary work visa and permanent residence than

the United States. Both Canada and Australia permit international students to work after graduation

for one to four years and give preferences to make gaining permanent residence easier. Australia

further reformed policies to retain international students to help in the economic recovery after the

COVID-19 pandemic.

Canada and Australia also use point-based systems that have been cited by some in the United

States as a direction for its immigration system, but a closer examination presents many cautions for

policymakers in considering a point-based system for the United States.

• Both Canada and Australia consider the ability of a spouse to work a key element for attracting

and retaining skilled talent. U.S. employers support expanding work authorization to all spouses

of H-1B visa holders, not just those whose spouse is waiting for a green card. That would place

the United States on close-to-equal footing for such skilled workers as Canada and Australia in

providing work authorization to spouses of temporary visa holders.

• Canada and Australia admit high-skilled immigrants without concern for country of origin.

The United States imposes a per-country cap on employment-based green cards, preventing any

country from receiving more than 7 percent of the total number of green cards available in a given

year. The cap can lead to long waits, potentially lasting decades, for immigrants from countries

with high numbers of green card applicants such as those born in India. In contrast, Australia and

Canada do not arbitrarily limit immigrants by country. In Australia, applications for permanent

residence for employment generally only take 4 to 12 months. Under the federal Express Entry

program in Canada, before the COVID-19 pandemic, processing times were generally just six

months or fewer. The Canadian government has committed to returning to those times. Processing

takes longer for those applications submitted outside of the federal Express Entry program, such

as the Provincial Nominee Program, but are still much shorter than the years or possibly decades

under the U.S. employment-based immigration system.

• Employers in Canada and Australia can hire foreign-born professionals on high-skilled temporary

visas without an annual limit, which helps both countries address needs in the labor market. The

most significant problem for U.S. employers that utilize temporary work visas is the fact that more

than 80 percent of applications for H-1B visas fail to be approved due to the low annual limit of

85,000. Due to the low annual limit in the United States, the supply of H-1B temporary visas has

been exhausted every year since 2004, forcing U.S. employers to either place a high-skilled foreign

4 | U.S. Immigration Policy: Lessons From Canada and Australia

national in another country or lose him or her to a foreign competitor. Canada has no annual limits

on high-skilled temporary visas, and it has announced a “Tech Talent Strategy” that includes new

policies to attract companies and foreign workers, including those experiencing problems with the

U.S. immigration system. The government will provide up to 10,000 three-year, open work permits

to H-1B visa holders to make their careers in Canada and promised other measures to attract highly

skilled professionals.

• Under its Global Skills Strategy, Canada committed to two-week processing for many high-

skilled positions, and the processing time in Australia is similar (three to six weeks). Long

processing times and visa denials continue to present problems in the United States even though

a legal settlement in 2020 with U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) over the Trump

Administration’s H-1B visa policies has caused a major source for the long wait times — Requests

for Evidence — and denial rates to decline. Meanwhile in Canada, processing times for visas under

the Global Skills Strategy have increased since the pandemic, but the government has committed to

returning to the two-week timeframe. In Australia, processing times for high-skilled work visas are

low, generally three to six weeks, and there is greater transparency there than in the United States

because case ocers are identified by name, which helps increase accountability.

• Canadian provinces and Australian states and regional areas play key roles in the admission of

immigrants and the establishment of criteria based on workforce needs, helping to fill gaps in

the federal point systems in those two countries. Both countries also often allow local employers

to be a driving force in selection. However, U.S. states play no role in admitting or influencing the

admission of immigrants, which makes the U.S. immigration system less responsive to local labor

needs than the Canadian and Australian systems.

• Canada admits four times as many immigrants as the United States as a percentage of its

population. To help address looming demographic and labor force problems, Canada increased the

country’s annual immigration level from 300,000 in 2017 to a target of 465,000 in 2023, 485,000 in

2024 and 500,000 in 2025, a rise of 67 percent between 2017 and 2025.

• Future U.S. growth depends on immigration. Statutory limits on U.S. immigration have not

changed since 1990. By 2042, net immigration will be the only source of population growth for the

United States, according to the Congressional Budget Oce.

• Australia admits two times as many legal immigrants as the United States as a percentage of

its population on an annual basis. In September 2022, the newly elected Labor government

announced an increase in the number of places in the permanent program to 195,000 in response

to the severe skill shortages being experienced as a result of the pandemic and to assist in

5 | U.S. Immigration Policy: Lessons From Canada and Australia

Australia’s economic recovery. This followed a short-lived lower level of 160,000 for 2019–2020

after several years of steady or increasing immigration levels.

• Canada and Australia have programs, including at the provincial, state and regional levels, to

facilitate the immigration of entrepreneurs. The United States lacks a startup visa to provide

permanent residence to foreign-born business founders.

• While point-based systems work well in Canada and Australia, fundamental dierences in how

the U.S. government and its immigration system are structured would make such a system

problematic to implement in the United States. Given the intricacies of such a system, this report

takes a deeper dive into point-based systems to assess the applicability of the Canadian and

Australian systems to the United States. A major issue the research raises is that fixing significant

problems that could arise with a point system might be dicult if the U.S. Congress eliminates

employer-sponsored permanent immigration and replaces it with a point-based system that

becomes “hard-wired” into the Immigration and Nationality Act and, therefore, requires new

legislation to make corrections.

No matter what changes are made to the U.S. immigration system, the Canadian and Australian

examples teach the United States that immigration is important to fuel economic growth. Much

economic research has found that reducing the overall level of legal immigration into the United

States would be bad for the U.S. economy because it would lead to slower labor force growth and,

consequently, slower economic growth. Reducing legal immigration would deny opportunity to many

people and be a significant policy error given the demographic future facing America. According to

a report by Citi and the University of Oxford: “Our analysis finds from 1990 to 2014, U.S. economic

growth would have been 15 percentage points lower without the benefit of migration.”

1

Higher levels of immigration would enhance economic growth and make dealing with the aging

of America’s workforce and population easier. Immigrants built the United States and are central to

its future. America has a successful tradition as a nation of immigrants, and U.S. immigration policy

should reflect that important fact. The United States needs an immigration system that admits more

immigrants and temporary visa holders at dierent skill levels to fill gaps in the labor market and fuel

the country’s growth and a prosperous future.

Fixing significant problems that could arise with a point system might be difficult if the U.S. Congress

eliminates employer-sponsored permanent immigration.

6 | U.S. Immigration Policy: Lessons From Canada and Australia

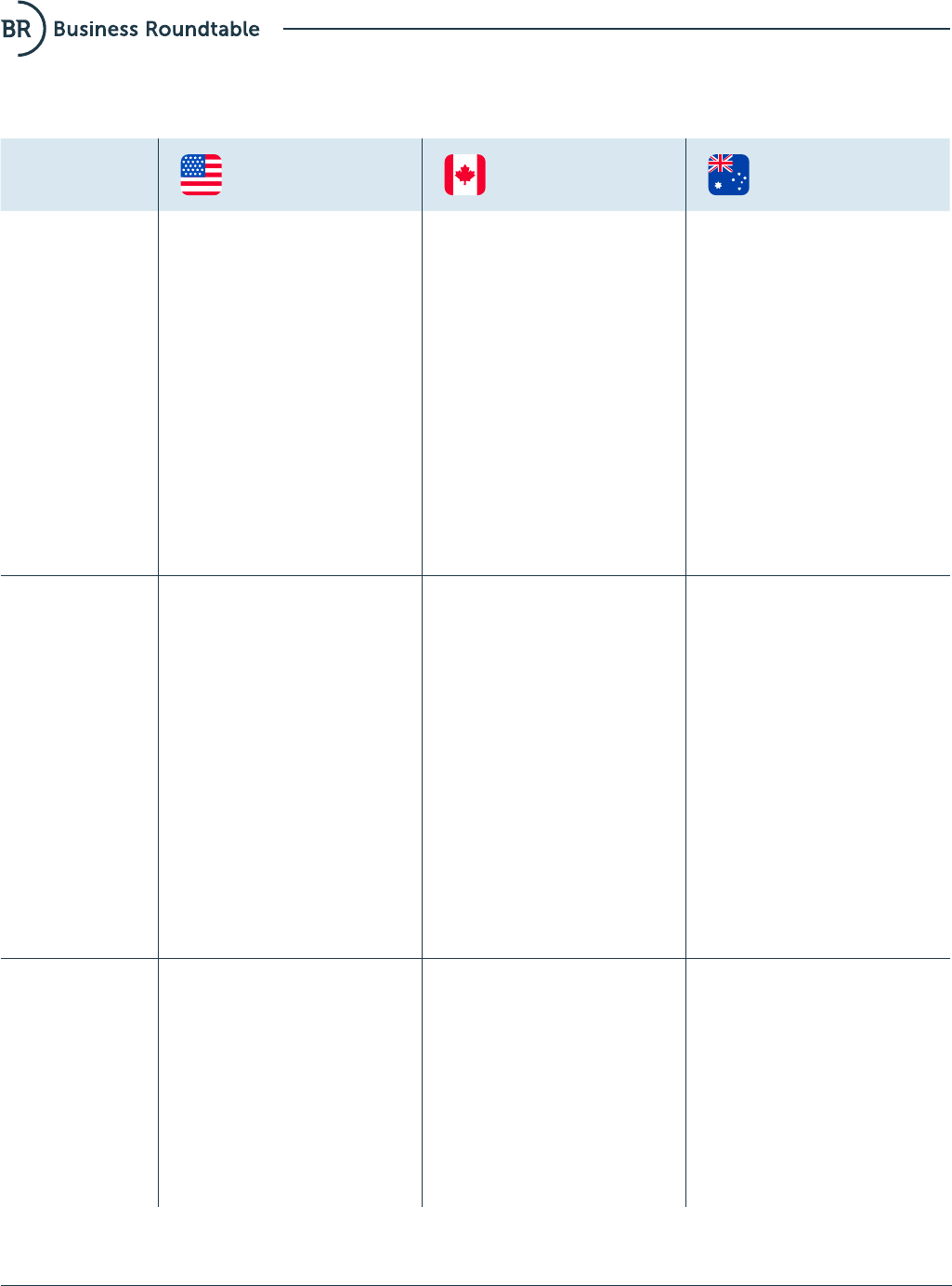

Immigration

Policy Area

Policies in the

United States

Policies in

Canada

Policies in

Australia

International

Students

Optional Practical Training

allows many international

students to work 12 to 36

months after graduation.

However, it is dicult for

international students to gain

temporary work status and

permanent residence to remain

long term in the United States,

placing employers in America at

a competitive disadvantage.

University graduates can obtain

work permits for up to three

years and receive advantages

in the Express Entry system for

gaining permanent residence.

International students can use

two dierent streams that allow

work ranging from 18 months

to 4 years, depending on their

degree, and student status can

increase their likelihood of

gaining permanent residence.

Spousal Work

Rights for Visa

Holders

The United States limits work

authorization to spouses of

H-1B visa holders with a spouse

in the process of applying for

permanent residence.

Canada considers the ability of

a spouse to work a key element

for attracting and retaining

skilled talent and grants such

authorization. The spouses and

dependent children (under age

22) of high-skilled and most

low-skilled temporary workers

are eligible for open work

permits.

Australia considers the ability

of a spouse to work important

for attracting and retaining

skilled talent and grants such

authorization.

Per-Country

Limits for

Permanent

Residence

Per-country limits on U.S.

employment-based green

cards result in much longer

waits for Indian-and Chinese-

born immigrants. Waits for

employer-sponsored Indians

can last potentially decades.

By 2030, without legislation,

the backlog for employment-

based immigrants could

exceed 2.1 million, according

to the Congressional Research

Service.

Canada admits high-skilled

immigrants without restriction

on country of origin; wait times

are typically 6 to 12 months

for permanent residence,

though were longer during the

pandemic.

Australia admits high-skilled

immigrants without restriction

on country of origin. The

process typically takes 4 to 12

months once it begins, normally

after an applicant works about

two years on a temporary visa.

Table 1: U.S., Canadian and Australian Immigration Policies on Key Issues

7 | U.S. Immigration Policy: Lessons From Canada and Australia

Immigration

Policy Area

Policies in the

United States

Policies in

Canada

Policies in

Australia

Annual Limits,

Processing and

Transparency

for High-Skilled

Temporary Visas

The annual limit on H-1B

temporary visas means over 80

percent of H-1B registrations

fail to result in approvals for

long-term employees.

Canada has no annual limit on

high-skilled temporary visas.

Under its Global Skills Strategy,

Canada commits to two-week

processing for many high-skill

positions, though that standard

was generally not met during

the pandemic. Generous points

are awarded in the Express

Entry point system for work in

Canada in temporary status.

A new “Tech Talent Strategy”

will provide up to 10,000

work permits to U.S. H-1B visa

holders.

Australia has no annual limit

on high-skilled temporary

visas and processes many

applications within three to six

weeks. It allows identification

of case ocers, which ensures

greater accountability. Foreign

nationals in Australia can obtain

permanent residence using a

streamlined process based on

prior approval of a temporary

work visa after a qualifying

period of employment.

Role for States,

Provinces or

Regional Areas

U.S. states are not allowed to

admit or influence the admission

of immigrants, resulting in much

less input on local labor force

needs.

Provinces in Canada play key

roles in admitting immigrants

and establishing immigration

criteria to meet workforce needs

through the Provincial Nominee

Program. Admissions are often

employer driven at the provincial

level. The Atlantic Immigration

Program provides a pathway

to permanent residence for

skilled foreign workers and

international graduates from

a Canadian institution who

want to work and live in one of

Canada’s four Atlantic provinces.

Through temporary Skilled

Work Regional visas, which

were introduced in 2019,

and the Permanent Skilled

Nominated visa category, states

and regional areas in Australia

play key roles in admitting

immigrants, working with

employers and establishing

immigration criteria to meet

workforce needs. Regional or

State Nominated visas make up

almost half of the permanent

visa places in the Skill-Based

stream for 2022–2023

migration.

Future

Demographic

Needs

Net immigration will account

for all population growth in the

United States starting in 2042,

according to the Congressional

Budget Oce. That means

immigration also likely will

become America’s only source

of labor force growth, a key part

of economic growth and an

improved standard of living.

Canada will increase its

immigration level by 67 percent

between 2017 and 2025;

Canada admits four times as

many immigrants as the United

States as a percentage of its

population.

Australia admits about two times

as many immigrants as the

United States as a percentage of

its population, and in September

2022, announced it would

increase its annual limit from

160,000 to 195,000.

8 | U.S. Immigration Policy: Lessons From Canada and Australia

Immigration

Policy Area

Policies in the

United States

Policies in

Canada

Policies in

Australia

Startup Visa

There is no startup visa under

U.S. law to allow a foreign

national to gain permanent

residence for establishing a new

business that attracts capital and

creates jobs.

Although it does not have an

extensive program at the federal

level, Canada facilitates the

immigration of entrepreneurs at

the provincial level.

Australia facilitates the

immigration of entrepreneurs,

including at the state and

regional levels, with a pathway

to permanent residence.

Point-Based

System

The United States does not use

a point-based system.

The Canadian system awards

points based on age, education,

language ability and, most

significantly, work experience in

Canada. The broad scope of the

laws in Canada and the power

given to immigration ministers

to make discretionary changes

to a point-based system —

without the need to pass new

legislation — significantly

differ from the current U.S.

immigration system.

Australia uses a point system

only for people seeking

permanent residence without

employer sponsorship. Employer

sponsorship in Australia works

similarly to the U.S. system,

although with much shorter wait

times.

Source: Business Roundtable analysis of the immigration laws of Canada, Australia and the United States.

9 | U.S. Immigration Policy: Lessons From Canada and Australia

I. Introduction

In the past few years, the United States has paid increased attention to the Canadian and Australian

immigration systems and whether American immigration policies are undermining the United States’

ability to compete for talent. To examine this issue, Business Roundtable looked at Canadian and

Australian immigration law and policies on international students, the ability of the spouses of visa

holders to work, employment-based immigration, the roles for state and provincial authorities,

and entrepreneurs, among other areas. The research builds upon the Business Roundtable State of

Immigration report, which ranked U.S. immigration policies 9th among 10 advanced economies in

promoting economic growth.

At U.S. universities, more than 70 percent of full-time graduate students in electrical engineering

and computer and information sciences are international students.

2

Decisions by Congress and the

executive branch determine whether this talent is employed in the United States and working for

American companies or pushed to work in other countries.

Multinational companies and startup businesses need access to individuals with skills to compete.

Individuals educated in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) fields are highly sought

by employers worldwide. If employers are not able to hire the talent in one country due to restrictive

immigration laws or policies, then they will shift resources to places that allow them to access that

talent. The Business Roundtable State of Immigration report explained that while other nations have

established policies to attract talent, the United States at times appears to have adopted policies

designed to push away foreign-born scientists, engineers and others.

If employers are not able to hire the talent in one country due to restrictive immigration laws or

policies, then they will shift resources to places that allow them to access that talent.

In State of Immigration, Business Roundtable detailed key problems in the U.S. immigration system.

Those problems have persisted and, in some cases, have worsened:

• The supply of H-1B temporary visas, the primary way U.S. employers hire high-skilled foreign

nationals to work long term in the United States, has been exhausted for two decades, in every

fiscal year since 2004. The low annual limit — 65,000 a year, plus 20,000 additional visas reserved

10 | U.S. Immigration Policy: Lessons From Canada and Australia

for individuals with a graduate degree from a U.S. university — is the main culprit. It has not

changed much since the Immigration Act of 1990 established an annual limit, and since that time

the demand for high-skilled technical labor has increased significantly due to the World Wide Web,

social media, smartphones and many other technological advances.

• The long waits for employment-based green cards (for permanent residence) are fueled by a

combination of a low annual limit and per-country caps that create longer wait times — especially

for individuals born in more populous countries, such as India and China. Due to the per-country

limits, the wait time for Indian-born employment-based immigrants is now generally measured in

decades. By 2030, without action by Congress, the backlog for employment-based immigrants

could exceed 2.1 million, according to the Congressional Research Service.

3

• The lack of legal visas for year-round, lower-skilled workers prevents employers from accessing a

critical workforce and contributes to illegal immigration.

• The absence of an immigrant entrepreneur visa discourages foreigners with innovative ideas and

access to venture capital from pursuing startup opportunities in the United States.

This report examines the immigration systems in Canada and Australia and features interviews

with attorneys who explain how the immigration systems in those countries work in the real world

and what America can learn from the Canadian and Australian experiences. The goal is for U.S.

policymakers to use this research as a guide when considering reforms to the U.S. immigration system

— and remember America’s successful tradition as a nation of immigrants when crafting immigration

policy.

11 | U.S. Immigration Policy: Lessons From Canada and Australia

II. The Business Case for Robust Legal Immigration

The business case for a robust legal immigration system rests on three elements: the global

competition for talent, the scarcity of labor and the role of immigration in fueling growth and

innovation.

First, if U.S. companies do not hire the best people, then their competitors will. A Society for Human

Resource Management (SHRM) survey found that “74 percent of employers reported that the ability

to obtain work visas in a timely, predictable and flexible manner is critical to their organization’s

business objectives. [Thirty-five] percent of respondents whose organizations are subject to the H-1B

visa cap [for high-skilled workers] reported that they had lost key organizational talent due to H-1Bs

being unavailable under the cap.”

4

According to an earlier SHRM survey, “[o]nly 19 percent of H-1B

cap-subject employers [in the United States] agree that there are enough H-1B visas to meet their

workforce needs. In other regions of the world, employer satisfaction with visa availability ranges from

52 percent to 74 percent.”

5

Second, the United States is facing a looming demographic crisis, with a need for millions of new

workers to replace retiring baby boomers. Net immigration will account for all population growth

in the United States starting in 2042, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

6

The difficulty

in finding workers has been apparent for years. In 2017, a Washington Post headline declared:

“Too Many Jobs, Not Enough Workers.”

7

U.S. employers are being rocked by global competition

and an increasing demand for highly skilled workers,” noted SHRM in 2019. “Foreign-born talent

is a necessary component to the U.S. workforce, particularly as the workforce continues to age

and the skills gap widens.”

8

A 2022 Conference Board survey of human resource executives titled

“Difficulty Finding and Retaining Office Workers Skyrockets” found 84 percent of employers seeking

professionals and office workers were “struggling to find talent.”

9

An April 2023 report from the Labor

Department’s Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) found 9.9 million job openings in the

United States, 42 percent higher than at the start of COVID-19 pandemic.”

10

Immigration is integral to the nation’s economic growth. Immigration supplies workers who

have helped the United States avoid the problems facing stagnant economies created by

unfavorable demographics.”

— The Economic and Fiscal Consequences of Immigration, The National Academies of Sciences,

Engineering, and Medicine, 2016

12 | U.S. Immigration Policy: Lessons From Canada and Australia

Labor force growth, of which immigration is a major component, is a key element of a nation’s

economic growth. “Immigration is integral to the nation’s economic growth,” according to a 2016

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine report. “Immigration supplies workers

who have helped the United States avoid the problems facing stagnant economies created by

unfavorable demographics — in particular, an aging (and, in the case of Japan, a shrinking) workforce.

Moreover, the infusion by high-skill immigration of human capital has boosted the nation’s capacity

for innovation, entrepreneurship and technological change.”

11

The Pew Research Center reported:

“Without future immigrants, the working-age population in the U.S. would decrease by 2035, …

[dropping] by almost 8 million (or more than 4 percent) from the 2015 working-age population.”

12

Third, immigration not only is part of America’s tradition but also has been a key element of its

success as a nation. The influx of immigrants in the 1800s and early 1900s fueled economic growth

and led to the large population and manufacturing base that helped the country prevail when

America faced peril during World War II. Over the past four decades, immigrant entrepreneurs and

professionals have helped make America a world leader in high technology, biotechnology and many

other sectors.

13 | U.S. Immigration Policy: Lessons From Canada and Australia

III. What Can Be Learned From Canadian and Australian Systems

Retaining International Students Postgraduation

In a world that grows smaller every year, the value of international students continues to increase,

particularly for employers who view international students as a prime source of talent. At U.S.

graduate schools, international students account for 82 percent of the full-time students in petroleum

engineering; 74 percent in electrical engineering; 72 percent in computer and information sciences;

and between 54 percent and 71 percent in fields that include industrial engineering, mechanical

engineering, civil engineering and chemical engineering.

13

International students also help keep graduate-level programs available for U.S. students, especially

in fields such as computer science and electrical engineering. “At the graduate level, international

students do not crowd-out but actually increase domestic enrollment,” according to Kevin Shih, an

assistant professor of economics at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. “Foreign student tuition revenue

is used to subsidize the cost of enrolling additional domestic students.”

14

International students are allowed 12 months of work authorization for Optional Practical Training

(OPT) after completing their studies in the United States. International students with a degree in

a designated STEM field can work for an additional 24 months under the STEM OPT regulation

published in March 2016.

15

Today, the difficulty in obtaining H-1B temporary status or employment-based green cards makes

remaining in the United States after graduation a challenge for international students. For the past

Table 2: International Students

Source: Business Roundtable analysis.

Immigration

Policy Area

Policies in the

United States

Policies in

Canada

Policies in

Australia

Current Policy

The diculty in obtaining

H-1B temporary status or

employment-based green

cards makes remaining in the

United States long term after

graduation challenging for

international students.

University graduates can

obtain three-year unrestricted

work permits and advantages

in the federal Express Entry

system and provincial nominee

programs.

International students can use

two dierent streams to allow

work ranging from 18 months

to four years.

14 | U.S. Immigration Policy: Lessons From Canada and Australia

two decades, the supply of H-1B visas has been exhausted every fiscal year. One reason employers

support STEM OPT is that it allows multiple attempts at obtaining an H-1B visa, typically the only

practical way an international student can work in America long term.

Field

Percent of

International

Students

Number of Full-

time Graduate

Students —

International

Students

Number of Full-

time Graduate

Students — U.S.

Students

Petroleum Engineering 82% 803 181

Electrical Engineering 74% 26,343 9,083

Computer and Information Sciences 72% 44,786 17,334

Industrial and Manufact. Engineering 71% 6,554 2,632

Statistics 70% 5,497 2,406

Economics 67% 8,023 4,049

Civil Engineering 61% 8,775 5,527

Mechanical Engineering 58% 11,215 8,130

Agricultural Economics 58% 766 561

Mathematics and Applied Math 56% 9,902 7,876

Chemical Engineering 54% 4,590 3,975

Metallurgical/Materials Engineering 53% 2,981 2,671

Materials Sciences 52% 713 660

Pharmaceutical Sciences 50% 1,790 1,827

Table 3: Full-Time Graduate Students and the Percentage of International Students

by Field (2019)

Source: National Science Foundation Survey of Graduate Students and Postdoctorates in Science and Engineering, Public

Use Microdata files. U.S. students include lawful permanent residents.

15 | U.S. Immigration Policy: Lessons From Canada and Australia

Between 2010 and 2020, there was a 135 percent increase in international students in Canada,

according to the Canadian Bureau for International Education (CBIE). “At the end of 2021, Canada saw

a return to pre-pandemic numbers of international students,” reported CBIE.

16

In the United States, the number of international students in the United States rose 31 percent

between 2010 and 2020. Before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, Canadian universities were

setting records for their enrollment of international students, even as new U.S. enrollment of foreign

students declined by approximately 10 percent in the 2018–2019 academic year when compared to

the 2015–2016 academic year, according to the Institute of International Education.

17

In the 2020–

2021 academic year, new international student enrollment in the United States remained below pre-

pandemic levels.

18

In the Business Roundtable State of Immigration country rankings, both Canada and Australia scored

higher than the United States on “Retention of International Students Postgraduation.” The 2015

report noted that while OPT was a positive aspect of U.S. immigration policy, “the lack of H-1B

visas and the long waits for employment-based green cards limit the opportunities for international

students to make their careers in the United States.”

19

The 2015 Business Roundtable report noted: “Canada provides ‘open’ work permits allowing

international students to work postgraduation for up to three years. Many students can transition

to permanent residence during this time period without leaving the country. ... Australia gives an

advantage to international students who apply for temporary visas. The lack of quotas on temporary

visas provides opportunities for international students sought by employers.”

20

Since the issuance of that report, the situation has remained essentially the same for international

students in Canada and Australia. Both countries make it relatively easy for foreign students to stay

and work after graduation, including gaining permanent residence to keep their skills in the country.

“In Canada we have a program for graduating international students similar to but more generous

than the U.S. Optional Practical Training category,” said Peter Rekai, an attorney with Rekai LLP

in Toronto. “Graduation from a public college or university course of at least two-years’ duration

allows for a three-year post-graduation work permit. During that period, a student who completes

a minimum of one year of skilled employment in Canada will be significantly rewarded under the

Express Entry system. The student will gain further ‘points’ for having completed a Canadian post-

secondary course of studies. In addition, some of the provinces have numerically capped programmes

that offer a direct path to permanent resident status for master’s and Ph.D. graduates of Canadian

universities, often without the need for Canadian job offers.”

21

16 | U.S. Immigration Policy: Lessons From Canada and Australia

Australia provides two types of visas for foreign graduates of Australian colleges. “The Graduate

Work stream is for international students who graduate with skills and qualifications that relate

to an occupation considered in demand in the Australian labour market, as indicated in the list of

eligible skilled occupations. A visa in this stream is generally granted for 18 months,” according to the

Department of Home Affairs.

22

Australia also offers a Post-Study Work stream for graduates. According to the Department of Home

Affairs, “[t]he Post-Study Work stream offers extended options for working in Australia to eligible

graduates of a higher education degree. Under this stream, successful applicants are granted a

visa with a visa period of two, three or four years’ duration, depending on the highest educational

qualification they have obtained.”

23

In order to support Australia’s recovery from the pandemic, a range of measures were introduced for

foreign graduates, including a temporary increase in the visa period under the Graduate Work Stream

to 24 months and for those who graduate with a master’s degree by coursework, an increase in the

visa period from two to three years under the Post-Study Work stream. In addition, following the Jobs

and Skills Summit held by the new Labor government in September 2022, an announcement was

made that the duration of stay for those with degrees in verified skilled shortages (to be determined by

a working group) would be increased by an additional two years.

24

“Australia has traditionally had a very open policy towards international students,” according to Polina

Oussova, formerly an immigration attorney with Berry, Appleman & Leiden in Australia. “Depending on

the course completed, the subsequent work visa would allow them to stay on in Australia for one to

four years.”

25

Robert Walsh, Asia Pacific counsel at the Fragomen law firm in Sydney, noted that working after

graduation facilitates an eventual path to permanent residence in Australia. “While the pathway

for international students to move to temporary employment-based visas and subsequently to

permanent employment-based visas is geared towards highly skilled (or shortage) occupations, it

nevertheless does provide a clear path to permanent residence for certain international students who

complete their course of study in Australia.”

26

Both Canada and Australia make it relatively easy for foreign students to stay and work after

graduation, including gaining permanent residence to keep their skills in the country.

17 | U.S. Immigration Policy: Lessons From Canada and Australia

Permitting the Spouses of Visa Holders to Work

Countries around the world understand that allowing the spouses of visa holders to work is vital to

attracting and retaining talent. U.S. companies know hiring high-skilled individuals from abroad may

be difficult if their spouses are unable to work in the United States. This issue is particularly important

given the long wait times — often many years — for high-skilled foreign nationals to gain permanent

residence in the United States. Spouses must remain in temporary status for a long period while

waiting for a green card, during which a spouse might not be able to work.

27

Under current U.S. immigration regulations, the spouses of E, L and certain H-1B visa holders are

eligible to work in the United States.

28

The Obama Administration implemented a rule on Employment Authorization for Certain H-4

Dependent Spouses on May 26, 2015.

29

The rule permits individuals to work if their H-1B spouse

has been approved for an Immigrant Petition for Alien Worker or has been waiting for an extended

period for an employment-based immigrant visa. During the Trump Administration, the Department of

Homeland Security (DHS) announced a proposed regulation to rescind the current rule that allows the

spouses of certain H-1B visa holders to work.

30

However, the current rule remained in place without

change.

Business Roundtable supports a regulation to expand H-4 work authorization to all spouses of H-1B

visa holders, not just those whose spouse is waiting for a green card.

31

Such a regulation would place

the United States on close-to-equal footing with Canada and Australia in providing work authorization

to spouses of temporary visa holders.

Table 4: Spousal Work Rights for Visa Holders

Source: Business Roundtable analysis.

Immigration

Policy Area

Policies in the

United States

Policies in

Canada

Policies in

Australia

Current Policy

The United States provides

work authorization for certain

spouses of H-1B visa holders.

The spouses and dependent

children (under age 22) of all

high-skilled and most low-

skilled temporary workers are

eligible for open work permits.

The spouses of high-skilled

professionals are allowed to

work.

18 | U.S. Immigration Policy: Lessons From Canada and Australia

The final rule published during the Obama Administration on H-4 spousal work authorization

specifically mentioned policies in Canada and Australia as a reason the United States should allow

the spouses of H-1B visa holders to work. “In addition, these regulatory amendments will bring U.S.

immigration policies more in line with the policies of other countries that seek to attract skilled foreign

workers,” DHS stated in the H-4 rule published in 2015. “For instance, in Canada spouses of temporary

workers may obtain an ‘open’ work permit allowing them to accept employment if the temporary

worker meets certain criteria. As another example, in Australia, certain temporary work visas allow

spousal employment.”

32

In Canada, the spouses of most work permit holders can obtain work authorization with little

difficulty. Spouses are “guaranteed an open spousal work permit,” noted one Canadian immigration

attorney,

33

and working-age dependent children of the work permit holder may also obtain an “open”

work permit in Canada.

“My personal view is that a decision by a foreign worker to accept a position in Canada will very often

be determined by issues other than their job, including whether their life partner can enter the labor

market,” said David Crawford, a partner with the Fragomen law firm in Toronto.

34

Australian policymakers and businesses agree with their Canadian counterparts about the importance

of spouses of visa holders being allowed to work. “Spouse work rights and the broad definition

of spouse are viewed by many employers, including both local and multinational companies, as

major draw cards in attracting highly skilled individuals to take up employment or an assignment in

Australia,” said immigration attorney Robert Walsh. “Spouse work rights are automatic on the grant

of the visa and are without limitation; for example, unlike the principal visa holder, the spouse can

change employers without reference to the immigration authorities.”

35

To address workforce shortages during the pandemic, the Australian government implemented

a temporary relaxation of work restrictions imposed on certain visas and included secondary visa

holders in these arrangements. For example, student visa holders who are normally restricted to

working 40 hours a fortnight have been given permission to work full time until mid-2023. This

not only includes the main student visa holder, but also any dependent visa holders.

36

Similarly,

dependents of Training visa holders who are normally subject to a work restriction have also been

given temporary permission to work full time for the same period.

37

Allowing the spouses of visa holders to work does not mean fewer jobs will be available for U.S.

workers since there is no such thing as a fixed number of jobs. Tens of thousands of spouses of

H-1B visa holders have received work authorization under the 2015 rule, and it has allowed many to

become employed or even start businesses.

38

19 | U.S. Immigration Policy: Lessons From Canada and Australia

Today, it is common for someone to marry a person with a similar level of educational attainment,

meaning the spouses of high-skilled foreign nationals are often well educated.

39

Allowing spouses to

work increases America’s overall economic output and provides an additional source of high-skilled

labor for U.S. employers.

A decision by a foreign worker to accept a position in Canada will very often be determined

by issues other than their job, including whether their life partner can enter the labor market.”

— David Crawford, partner, Fragomen Worldwide in Toronto

No Per-Country Limits for Permanent Residence

The U.S. employment-based immigration system is plagued by the dual problems of low annual limits

and per-country caps. The annual limit on employment-based green cards (for permanent residence)

is 140,000, which includes dependents (spouses and minor children), who typically fill about half of

the quota. That level was set in 1990, before the demand for high-skilled labor exploded due to the

World Wide Web, social media and smartphones.

But the low annual level is only one reason for the long wait for green cards in the United States.

The other reason is per-country limits, which lead to much longer waits for employer-sponsored

immigrants from larger countries with many educated professionals, including India, China and the

Table 5: Per-Country Limits for Permanent Residence

Source: Business Roundtable analysis.

Immigration

Policy Area

Policies in the

United States

Policies in

Canada

Policies in

Australia

Current Policy

Per-country limits in the

U.S. green card system

cause employer-sponsored

immigrants from India and

China to wait many additional

years for permanent residence.

There is no per-country limit;

wait times for permanent

residence are returning to the

standard 6 to 12 months, which

is much shorter than in the

United States.

There is no per-country limit;

wait times for permanent

residence are typically 4 to 12

months, which is much shorter

than in the United States.

20 | U.S. Immigration Policy: Lessons From Canada and Australia

Philippines. “The [Immigration and Nationality Act] also specifies per-country limits equal to 7 percent

of the combined total number of visas allotted to family-and employment-based preferences,”

explains DHS. “In 2015, these limits amounted to 25,956 immigrants from any single country.”

40

Because of India’s large population and technical base, Indian nationals represent the largest number

of high-skilled foreign nationals working in the United States in H-1B status.

41

Due to the per-country

limits (and low annual limits), the wait times for Indians in the two most common employment-based

green card categories are exceedingly long, potentially beyond the lifespan of many workers.

42

“For nationals from large migrant-sending countries … the numerical limit and per-country ceiling

have created inordinately long waits for employment-based green cards,” writes the Congressional

Research Service (CRS). “New prospective immigrants entering the backlog (beneficiaries) outnumber

available green cards by more than two to one. Many Indian nationals will have to wait decades to

receive a green card. The backlog can impose significant hardship on these prospective immigrants,

many of whom already reside in the United States. It can also disadvantage U.S. employers, relative to

other countries’ employers, for attracting highly trained workers.”

43

As reported in State of Immigration: “Canada does not impose per-country limits, as the United States

does. That means international students from India or China can envision a shorter path to permanent

residence than the potential decade-long (or longer) wait in the United States.”

48

According to CRS:

• Without changes to the law, it would take an estimated 195 years to eliminate the current backlog

of Indian nationals waiting for employment-based green cards.

44

• The backlog in the employment-based second preference (EB2) will rise to nearly 1.5 million by

2030 and to over 450,000 in the employment-based third preference (EB3).

45

• Without action by Congress, “[t]he total backlog for all three employment-based categories

would increase … to an estimated 2,195,795 by FY 2030.”

46

Australia has no per-country caps,

which helps limit wait times. “In broad terms it takes between 4 and 12 months for a highly skilled

individual to transition to permanent residence depending on the visa stream being utilized under

Australia’s employer-sponsored permanent residence program,” according to attorney Robert

Walsh in Sydney. “There has been some tightening of this process in recent times, which has

contributed to longer processing times, but it is still an important pathway for a wide range of

highly skilled individuals to take up permanent residence in Australia.”

47

21 | U.S. Immigration Policy: Lessons From Canada and Australia

Recent data from Canada indicate that more Indian nationals are gaining permanent residence under

the country’s Express Entry system.

49

The number of new lawful permanent residents from India

more than doubled in Canada from 2016 to 2019 in Canada (from 39,710 to 85,590), making India

the number one source for immigrants in the country. After a decline to 42,865 in 2020 due to the

pandemic, Indian permanent residents rose to 127,795 in 2021 and 113,490 in 2022.

50

Experts interpret the increase in Indian immigration to Canada since 2016 as evidence that more

Indian-born professionals have become frustrated with the long waits for green cards and other

immigration issues in the United States and prefer the smoother Canadian path from student to

temporary status and then permanent residence.

“At U.S. universities, Indian graduate students in science and engineering, a key source of U.S. talent,

fell dramatically, by nearly 40%, between 2016 and 2019 (before the pandemic),” according to

an analysis of international student data. “During the same period (2016 to 2019), Indian students

attending Canadian colleges and universities increased 182%. The difference in enrollment trends

is largely a result of it being much easier for Indian students to work after graduation and become

permanent residents in Canada compared to the United States.”

51

“The Government of Canada does not limit access to permanent resident status for foreign nationals

determined by country of birth or of citizenship,” according to attorney David Crawford.

52

Australia

also does not impose per-country limits, and as a result, attracting and retaining talented individuals

without regard to nationality is easier.

Canada does not impose per-country limits, as the United States does. That means

international students from India or China can envision a shorter path to permanent

residence than the potential decade-long (or longer) wait in the United States.”

— State of Immigration, Business Roundtable, 2015

Under the federal Express Entry program in Canada, the processing time once an individual completes

an online profile and submits a completed application is generally 6 to 12 months, according to

attorneys, while processing takes more time for economic immigration processed outside of the

Express Entry system. Processing in Canada is still recovering from backlogs that have accumulated

since 2020.

22 | U.S. Immigration Policy: Lessons From Canada and Australia

No Annual Limits, Quicker Processing and Greater Transparency for High-Skilled

Temporary Work Visas

Being able to petition and receive approval for a visa for a high-skilled foreign-born professional in a

timely and predictable manner can allow companies to innovate, better serve customers and invest

reliably in a specific geographic location. The lack of timeliness and predictability for visa availability

and case decisions are major problems in the U.S. immigration system. Not so in Canada and Australia.

“Both Canada and Australia have no annual limit on high-skilled temporary visas. The system for

temporary visas for skilled workers in Australia is demand driven based on employer needs and

without numerical caps,” notes Charles Johanes, a special counsel and regional practice leader in

Fragomen’s Sydney office.

53

“There is no numerical limit or quota on high-skilled visas in Canada,” said attorney David Crawford.

54

“A higher degree of certainty of outcomes assists business planning.” Peter Rekai agreed with

Crawford and, importantly, many U.S. companies agree also. “We do have quite a few U.S. corporate

clients, and there is growing realization they will be unable to get U.S. work permits for many of

their high-skilled temporary workers,” said Rekai. “In response, a number of these clients are either

increasing the size of their Canadian affiliates or creating Canadian affiliates and placing key foreign

staff there.”

55

In the United States, processing times for H-1B petitions used to take a year — as compared to

just two weeks on average in Canada before the pandemic and three to six weeks in Australia —

and petitions often elicited many Requests for Evidence leading to even longer delays. During the

Trump Administration, denial rates at USCIS for new H-1B petitions rose from 6 percent in FY 2015

to 24 percent in FY 2018, and the Requests for Evidence rate reached as high as 60 percent.

56

After

successful lawsuits, a legal settlement and changes to USCIS policies, H-1B denial rates are at

historically low levels.

57

We do have quite a few U.S. corporate clients, and there is growing realization they will be

unable to get U.S. work permits for many of their high-skilled temporary workers. In response,

a number of these clients are... increasing the size of their Canadian affiliates.”

— Peter Rekai, attorney, Rekai LLP in Toronto

23 | U.S. Immigration Policy: Lessons From Canada and Australia

The annual 85,000 cap on H-1B petitions (65,000 plus 20,000 visas reserved for graduate degree

holders from U.S. universities) has been exhausted every fiscal year for the past two decades, leaving

many companies with no way to employ new high-skilled foreign nationals in the United States.

USCIS announced in April 2022 that it received nearly 484,000 H-1B registrations for FY 2023, which

meant close to 400,000 registrations would not result in an employer gaining an approved H-1B

petition for a high-skilled professional due to the 85,000 annual limit.

58

Processing times at the California Service Center for an H-1B visa are mostly in the 2 to 5 months

range, compared to 9 to 12 months in 2019. Lynden Melmed, a partner with Berry, Appleman & Leiden

in Washington, DC, noted that the exception would be if an employer paid up to $2,500 in premium

processing fees to the federal government to expedite case processing.

59

In contrast, Canada launched the Global Skills Strategy to “provide a two-week processing time for

80 percent of work permit applications; work permit exemptions for highly-skilled workers on short-

term work assignments and for researchers involved in a short-duration research project in Canada;

and a dedicated service channel for companies looking to make large, job-creating investments in

Table 6: Annual Limits, Processing and Transparency for High-Skilled Temporary Visas

Source: Business Roundtable analysis.

Immigration

Policy Area

Policies in the

United States

Policies in

Canada

Policies in

Australia

Current Policy

The low annual limit on H-1B

visas means that every year

U.S. companies are thwarted in

hiring or retaining key foreign-

born personnel. Although

denial rates have improved

since a 2020 legal settlement,

U.S. companies and their

attorneys have complained of

long processing delays and

remain concerned about a

lack of accountability for case

decisions.

Canada has no annual limit

on high-skilled work visas

and established two-week

processing times for many

high-skilled visa applications,

focusing on positions in

information technology.

Australia has no annual limit

on high-skilled temporary

work visas. The name of the

individual deciding about

an immigration application

appears on documents,

increasing accountability. Many

applications for high-skilled

workers are completed within

three to six weeks.

24 | U.S. Immigration Policy: Lessons From Canada and Australia

Canada.”

60

This strategy shows the willingness of the Canadian government to make retaining or

bringing in talent easier, rather than more difficult, for employers in Canada.

61

“This program came from the business community,” said Canada’s previous Immigration Minister

Ahmed Hussen. “They identified a challenge and said, ‘You need to fix it.’” Bloomberg reported

that “ [t]hose who are fast-tracked can apply to stay as long as three years and also for permanent

residency. Computer programmers, systems analysts and software engineers are the top three

categories of workers to benefit so far.”

62

A major complaint of U.S. employers is a lack of transparency and accountability in immigration

decisions by USCIS. In the United States, adjudicators are anonymous, which may contribute to

excessive Requests for Evidence and questionable decisions. Not so in Australia.

The name of the case officer approving or denying an immigration petition has generally appeared on

documents, according to immigration attorneys with experience in Australia. In contrast, the United

States does not even list an officer number in most cases. “Having a name on an application in the

United States would be great,” said Noah Klug with Klug Law Firm, an American who has practiced in

both countries, including for six years in Australia. “It would help increase accountability. If we could

contact the officer directly, that would be even better and was a huge help when I practiced Australian

immigration law and was able to do so with complex cases that benefited from such dialogue.”

63

U.S. adjudicators putting their names on decisions and Requests for Evidence would lead to greater

transparency and could result in quicker and more defensible case decisions.

“The current practice in Australia is to provide the official’s first name, their official position number

and generic contact information,” said Robert Walsh. “This approach does ensure that the official can

be identified and held ultimately accountable for their actions either through a complaints process or

when the decision is appealed through review processes. Their identity will generally not be known to

the visa applicant or their representative, but nevertheless there is an ultimate accountability for the

official’s actions.”

64

In the United States, adjudicators are anonymous, which may contribute to excessive Requests for

Evidence and questionable decisions. Not so in Australia.

25 | U.S. Immigration Policy: Lessons From Canada and Australia

“In general, I would say the processing model [in Australia] does encourage accountability by case

officers,” said attorney Polina Oussova. “The Department of Home Affairs undertakes spontaneous

audits to review the requests for further information that have been issued by case officers to ensure

that they are justifiable. This helps to ensure consistency from case officers in their assessments.”

65

Oussova said it takes only about one to two weeks for approval of most work visas for skilled workers

in Australia. For companies that are “nonaccredited” — meaning they do not meet certain thresholds

on size, past successful application and other criteria — the process is 4 to 10 weeks (or longer in

some cases).

66

In Australia, the Minister for Immigration is also able to issue Ministerial Directions which dictate the

order in which applications are to be processed by officials to ensure that government policy priorities

are being met. This mechanism was used during the pandemic to prioritize applications for individuals

working in critical sectors or occupations in demand. The current Ministerial Direction gives priority to

occupations in health and education sectors, those nominated by accredited sponsors as well as roles

that are located in regional areas.

67

A smooth transition from temporary work status to permanent residence is an important feature

of the Australian immigration system for employers and skilled foreign-born professionals and

researchers. “The Temporary Residence Transition stream is especially handy because it allows foreign

nationals in Australia on temporary work visas to obtain permanent residence in a streamlined fashion

based primarily on the fact that they had qualified previously for a temporary work visa,” noted Noah

Klug.

68

Temporary visas also play a key role in the Canadian immigration system, specifically the federal

Express Entry system. “Generous ‘points’ are accorded to those with skilled work experience in

Canada and to holders of Canadian post-secondary diplomas and degrees,” according to Peter Rekai.

“This effectively establishes a path to permanent residence for currently employed skilled temporary

foreign workers, ensuring that most of Canada’s new economic immigrants are already gainfully

employed by the time they become permanent residents. This ‘path’ to permanent residence also

underlines the significant role played by Canadian employers, who initially choose the temporary

foreign workers.”

69

The Canadian government has made efforts to minimize delays for employers seeking temporary

visas. “The Government of Canada is conscious of the impact of delays for employers seeking skilled

workers, particularly in certain occupations,” said David Crawford with Fragomen. “The incidence of

26 | U.S. Immigration Policy: Lessons From Canada and Australia

a Request for Evidence equivalent is very low in our experience. It is true, however, that assessments

at some diplomatic missions abroad can be lengthy because of application rates.” Crawford noted

that Canada’s Global Skills Strategy, with the two-week processing time, “was accompanied by other

changes designed to facilitate the entry of highly skilled workers.”

70

Canada has continued in its efforts to attract foreign workers, including those experiencing problems

with the U.S. immigration system. Its “Tech Talent Strategy” announced in June 2023 will provide up

to 10,000 three-year, open work permits to H-1B visa holders to make their careers in Canada, among

other promised incentives to attract highly skilled professionals.

71

27 | U.S. Immigration Policy: Lessons From Canada and Australia

Providing a Role for States, Provinces or Regional Areas

It is beneficial for employers to possess a variety of options for hiring or retaining workers identified as

important to growing their companies. A state or local entity often has a better idea of business needs

for workers than an agency of the federal government located hundreds, or even thousands, of miles

away.

Under U.S. law, states have no role in immigration admissions policy. That is not the case in Canada

and Australia. Giving nonfederal governmental entities a role in Canada and Australia allows diverse

economic needs to be met, something difficult to achieve with a single overarching national policy.

Governor Eric Holcomb (R-IN) and Governor Spencer Cox (R-UT) advocate Congress change the

law to give a role to the U.S. states. “Rapidly declining birthrates and accelerating retirements across

the United States mean that our states’ already wide job gaps will grow to crisis proportions. … Many

of these jobs require high-level skills and entrepreneurship,” they wrote in the Washington Post. “But

states are also awash in unfilled entry-level, low-skill roles — essential in agriculture, health care and

the service industries. So, count us as supporters of immigration sponsorship by the states.”

The governors note that “[u]nder such authority, similar to what employers and universities have

already, each state could make its own decisions. They could sponsor no visas or many visas

each year, up to a limit set by Congress, for the specific sorts of jobs they need to fill. Immigration

sponsorship would give states a dynamic means to attract new residents, both from a pool of new

applicants from abroad and from the ranks of current asylum seekers. The policy would also expand

the states’ responsibility for the contributions and success of these folks in American life.”

72

As discussed in State of Immigration, the Regional Sponsored Migration Scheme visa in Australia

allows an individual to receive permanent residence if “nominated by an approved Australian employer

for a job in regional Australia.”

73

In 2019, new Skilled Regional Visas were introduced in Australia, and an individual can apply for a

provisional temporary visa valid for five years either nominated by a State/Territory government or

regional-based employer and transition to permanent residence after three years. Additionally, there

Under U.S. law, states have no role in immigration admissions policy. That is not the case in Canada

and Australia.

28 | U.S. Immigration Policy: Lessons From Canada and Australia

is also an independent skilled visa category where, if an individual is supported by a State/Territory

government, they will automatically be issued an invitation to apply for a permanent visa.

74

Similarly, the Provincial Nominee Program in Canada permits provinces to sponsor individuals or

to work within the federal Express Entry point system by giving a high number of points to those

nominated by a province. These programs have grown in recent decades, according to attorney Peter

Rekai.

75

Table 7: Role for States, Provinces or Regional Areas

Source: Business Roundtable analysis.

Immigration

Policy Area

Policies in the

United States

Policies in

Canada

Policies in

Australia

Current Policy

States have no role in the

admission of immigrants or

temporary visa holders.

Canada’s Provincial Nominee

Program allows sponsorship

of immigrants or additional

points for federal Express

Entry, enabling dierences

in economic needs within

provinces to be addressed.

New temporary visas were

introduced in 2019 for working

in states or regions, supported

by a State/Territory government

or regional zzbased employer.

There is also a category of

skilled visa where an individual

can be supported by a State/

Territory government which

entitles them to an invitation to

apply for a permanent visa.

“The provinces have their own economic and social priorities, and the provincial programs enable

them to design criteria for their immigration programs to meet their own objectives,” said David

Crawford. “An example relates to the various entrepreneur programs that exist to encourage business

people to enter provinces and run a business. Another example relates to senior and experienced

business people who, because of their age, may find it difficult to qualify for one of the federal skilled

worker programs for permanent resident status.”

76

Crawford noted that provinces attempt to attract suitable applicants: “Candidates entering through

the provincial programs make up a proportionally large number of immigrants in some provinces.

These programs thus empower the provinces to play an important role in building their skills base.”

77

The Canadian government has established the Atlantic Immigration Program, which previously

was a pilot program. “The Atlantic Immigration Program is a pathway to permanent residence for

29 | U.S. Immigration Policy: Lessons From Canada and Australia

skilled foreign workers and international graduates from a Canadian institution who want to work

and live in 1 of Canada’s 4 Atlantic provinces — New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island

or Newfoundland and Labrador,” according to the Government of Canada. “The program helps

employers hire qualified candidates for jobs they haven’t been able to fill locally.”

78

Australia has seen similar benefits from its own policies. “Allowing individual states of Australia to play

a role in the immigration system is a benefit for individual states and territories and also for people

seeking to take up employment-based temporary or permanent residence in Australia,” said Robert

Walsh of Fragomen. “Constitutional responsibility for immigration matters rests with the national or

federal government, but state and territory governments have played a role in the immigration system

for many years.”

79

This situation has allowed states in Australia to participate in immigration decisions in a way that does

not exist in the United States. “For the individual states, Australian immigration policy allows the state

government to address skill shortages within its jurisdiction based on economic conditions and give

priority to different types of economic activity,” according to Walsh. “It also allows individual states to

encourage people seeking to migrate to Australia to take up residence in their state. Through state-

sponsored skilled and employment visas, individual states can give priority to certain occupations

where there are identified shortages in the state.”

80

Walsh gave the example of the investment upturn in the oil and gas sectors in the states of Western

Australia and Queensland. He said people from overseas in oil and gas engineering occupations were

given additional support to take up residence in those states. “Once the investment and construction

phase finished, this support at the state level was withdrawn,” he said. “The state government is able

to be more responsive to changing circumstances in its own jurisdiction. Individuals are encouraged

to take up residence in an individual state [that] has identified a need for people with skills in critical

shortage occupations.”

81

Polina Oussova agreed that states are in the best position to identify their needs. The autonomy states

are given, including allowing them to advise on required occupations, makes immigration policy more

likely to meet the needs of Australian businesses.

The autonomy states are given, including allowing them to advise on required occupations, makes

immigration policy more likely to meet the needs of Australian businesses.

30 | U.S. Immigration Policy: Lessons From Canada and Australia

As part of its plan to encourage foreign nationals to settle outside of major cities, Australia introduced

two new temporary visas in 2019. “The Skilled Employer Sponsored Regional (Provisional) visa [is] for

people sponsored by an employer in regional Australia [and the] Skilled Work Regional (Provisional)

visa [is] for people who are nominated by a State or Territory government or sponsored by an eligible

family member to live and work in regional Australia,” according to a government announcement.

“Holders of the new skilled regional provisional visas will need to live and work in regional Australia.

Visas will be granted with a validity period of up to five years.”

82

Dealing With an Unfavorable Demographic Future

Both companies and economies need an increasing supply of workers to grow. If a restaurant owner

cannot find enough workers, then he or she will not open a second restaurant. A manufacturer will

start or expand a factory only if a reasonable chance exists that workers will be available to fill those

new jobs. High-tech employers will locate or expand research and development where they have

access to talent.

The retirement of the baby boom generation and slowing U.S. population growth mean that

immigrants are a primary source of new workers. Demographers note that the number of people

of working age in the United States would decline by several million in the coming decades without

immigrants to prevent the potential shortfall.

83

“Sensible immigration policies would increase the pace of overall population and workforce growth,”

explained the Business Roundtable report Contributing to American Growth: The Economic Case for

Immigration Reform. “By improving the efficiency with which immigrants are able to enter the United

States and providing legal status to currently unauthorized U.S. residents, immigration reform would

expand the U.S. labor force and, as a direct consequence, overall economic output. Reform would

have this impact because at the broadest level, an economy’s output growth is defined as the sum of

two factors: the increase in the productivity of its capital and the increase in its labor input.”

84

“The path of immigration policy will have a substantial bearing on the nation’s supply of workers,

which has been expanding more slowly as native-born workers have fewer children,” according to

the New York Times.

85

The Congressional Budget Office concluded: “After 2033, population growth is

increasingly driven by net immigration, which accounts for all population growth beginning in 2042.”

86

That means immigration also likely will become America’s only source of labor force growth, a key

ingredient of economic growth and an improving standard of living.

31 | U.S. Immigration Policy: Lessons From Canada and Australia

Canada has moved to support economic growth with increased immigration. In November 2022,

Canadian Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Sean Fraser noted the country has

welcomed over 400,000 immigrants in 2021 and said in a statement: “The Government is continuing

that ambition by setting targets in the new levels plan of 465,000 permanent residents in 2023,

485,000 in 2024 and 500,000 in 2025 …. This plan helps cement Canada’s place among the world’s

top destinations for talent, creating a strong foundation for continued economic growth, while also

reuniting family members with their loved ones and fulfilling Canada’s humanitarian commitments.”

88

The announcement that Canada will increase its immigration levels did not surprise Lily Jamali,

an American journalist who reported from Canada. “Canadians see immigration as an economic

imperative to help the country for years to come,” she said. “The aging demographics issue concerns

people, and whether it’s welcoming high-tech professionals or refugees, there’s a sense here that