Pepperdine University Pepperdine University

Pepperdine Digital Commons Pepperdine Digital Commons

Theses and Dissertations

2014

Student perceptions of a mobile augmented reality game and Student perceptions of a mobile augmented reality game and

willingness to communicate in Japanese willingness to communicate in Japanese

Andrea Misao Shea

Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/etd

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Shea, Andrea Misao, "Student perceptions of a mobile augmented reality game and willingness to

communicate in Japanese" (2014).

Theses and Dissertations

. 432.

https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/etd/432

This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted

for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more

information, please contact bailey[email protected].

Pepperdine University

Graduate School of Education and Psychology

STUDENT PERCEPTIONS OF A MOBILE AUGMENTED REALITY GAME AND

WILLINGNESS TO COMMUNICATE IN JAPANESE

A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction

of the requirements for the degree of

Doctor of Education in Learning Technologies

by

Andrea Misao Shea

May, 2014

Martine Jago, Ph.D. – Dissertation Chairperson

This dissertation, written by

Andrea Misao Shea

under the guidance of a Faculty Committee and approved by its members, has been submitted to

and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

DOCTOR OF EDUCATION

Doctoral Committee:

Martine Jago, Ph.D., Chairperson

Linda Purrington, Ed.D.

Kazue Masuyama, Ph.D.

© Copyright by Andrea Misao Shea (2014)

All Rights Reserved

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

LIST OF TABLES ......................................................................................................................... vii

LIST OF FIGURES ..................................................................................................................... viii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................ ix

VITA ............................................................................................................................................... xi

ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................................. xii

Chapter 1: Introduction .................................................................................................................... 1

Context ................................................................................................................................. 1

Purpose Statement ............................................................................................................... 7

Research Questions .............................................................................................................. 8

Delimitations ....................................................................................................................... 8

Limitations ........................................................................................................................... 8

Assumptions ........................................................................................................................ 9

Terminology ........................................................................................................................ 9

Importance of the Study .................................................................................................... 11

Organization of the Study .................................................................................................. 12

Chapter 2: Conceptual Foundation ................................................................................................ 13

Language Learning ............................................................................................................ 13

Situated Learning ............................................................................................................... 14

Mobile Learning ................................................................................................................ 15

Video Games and Language Learning .............................................................................. 17

Virtual Worlds ................................................................................................................... 19

Augmented Reality ............................................................................................................ 22

Willingness to Communicate in L2 ................................................................................... 29

Summary ............................................................................................................................ 33

Chapter 3: Methodology ................................................................................................................ 35

Researcher Positionality .................................................................................................... 35

Rationale for a Qualitative Case Study Approach ............................................................. 36

Pilot Study ......................................................................................................................... 37

Game Description: Yookoso .............................................................................................. 42

Research Timeline ............................................................................................................. 50

Sample ............................................................................................................................... 51

v

Research Tools .................................................................................................................. 51

Research Questions and Methods ...................................................................................... 54

Data Collection Techniques ............................................................................................... 54

Data Analysis ..................................................................................................................... 57

Human Subjects Considerations ........................................................................................ 59

Summary ............................................................................................................................ 61

Chapter 4: Findings ....................................................................................................................... 62

Demographic Survey ......................................................................................................... 62

Observations ...................................................................................................................... 63

Game Objects .................................................................................................................... 66

Game Artifacts ................................................................................................................... 67

Interviews .......................................................................................................................... 68

Participants ........................................................................................................................ 70

Selected Quotes ................................................................................................................. 73

Cross-case Analysis ........................................................................................................... 85

Summary ............................................................................................................................ 94

Chapter 5: Discussion .................................................................................................................... 95

Key Themes ....................................................................................................................... 96

Research Questions .......................................................................................................... 101

Project Evaluation ............................................................................................................ 108

Recommendations for Future Research ........................................................................... 112

Conclusions ..................................................................................................................... 113

REFERENCES ............................................................................................................................ 116

APPENDIX A: Game User's Guide ............................................................................................ 132

APPENDIX B: Game Observation Protocol ............................................................................... 143

APPENDIX C: Semi-structured Interview Guide ....................................................................... 144

APPENDIX D: Data Collection Log ........................................................................................... 145

APPENDIX E: Invitation to Participate in Study ........................................................................ 146

APPENDIX F: Informed Consent for Participation Form .......................................................... 148

APPENDIX G: Research Information Sheet ............................................................................... 151

APPENDIX H: Demographic Survey ......................................................................................... 153

APPENDIX I: Game Play Log .................................................................................................... 154

APPENDIX J: ARIS Web-based Editor ...................................................................................... 159

vi

APPENDIX K: Server Log Example .......................................................................................... 160

APPENDIX L: HyperRESEARCH Coding Screenshot .............................................................. 161

APPENDIX M: IRB Approval Notice ........................................................................................ 162

vii

LIST OF TABLES

Page

Table 1. WTC Antecedent Variables and Mobile AR Game Affordances .................................. 34

Table 2. Antecedents to WTC and Game Characteristics ............................................................ 43

Table 3. Game Audio Prompts ..................................................................................................... 47

Table 4. Hidden Game Prompts ................................................................................................... 48

Table 5. Research Timeline .......................................................................................................... 50

Table 6. Research Questions and Methods ................................................................................... 54

Table 7. Demographic Survey Results ......................................................................................... 63

Table 8. Audio Prompts Found by Participants ............................................................................ 66

Table 9. Text Prompts Found by Participants .............................................................................. 66

Table 10. Game Results ................................................................................................................ 67

Table 11. Evidence of WTC Antecedents .................................................................................... 69

Table 12. Game Characteristics .................................................................................................... 69

Table 13. WTC Antecedent Content-Analytic Summary ............................................................. 86

Table 14. Game Characteristic Content-Analytic Summary ........................................................ 90

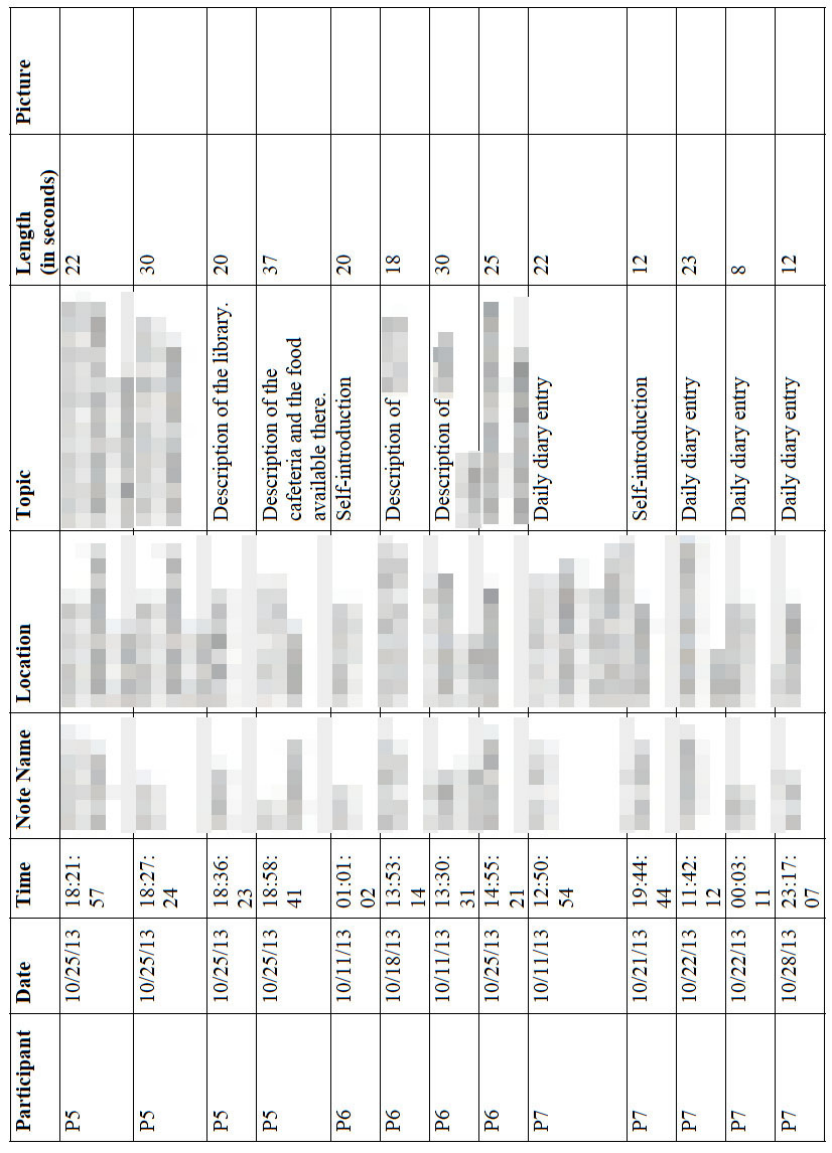

Table 15. Data Collection Log ................................................................................................... 145

Table 16. Game Play Log ........................................................................................................... 155

viii

LIST OF FIGURES

Page

Figure 1. Example of a 2D barcode. ................................................................................................ 4

Figure 2. Screenshot of a class meeting within the Second Life virtual world. ............................ 20

Figure 3. ARIS application user interface on an iPhone. .............................................................. 28

Figure 4. Model of variables influencing WTC. ........................................................................... 30

Figure 5. Portion of MacIntyre and Charos’ (1996) model of L2 communication applied to adult

French learners. .............................................................................................................. 31

Figure 6. Model depicting relationship between AR mobile games, trait and situational variables,

and L2 WTC. .................................................................................................................. 32

Figure 7. Example screenshot from the first pilot game. ............................................................... 39

Figure 8. Second pilot game screenshot. ....................................................................................... 41

Figure 9. Welcome screen. ............................................................................................................ 45

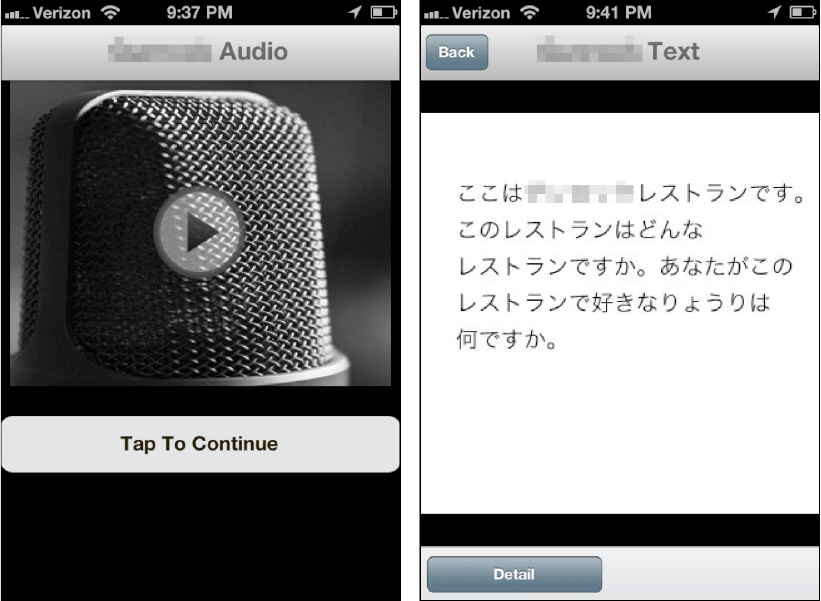

Figure 10. Screenshots of audio prompt and corresponding text item. ......................................... 46

Figure 11. In-game map with audio prompt icons. The dot indicates the location of the player. . 48

Figure 12. Example of a hidden game prompt. ............................................................................. 49

Figure 13. Game inventory screenshot. ......................................................................................... 50

Figure 14. Participant typing notes on her iPad. ............................................................................ 65

Figure 15. iPad notes in English and Japanese. ............................................................................. 65

Figure 16. Participant use of the game’s recording feature. .......................................................... 68

Figure 17. Findings to themes grouping ........................................................................................ 96

ix

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I wish to thank my dissertation chairperson Dr. Martine Jago. It has been such a pleasure

and honor to work with you. You are everything a doctoral student could ever ask for in a

chairperson: knowledgeable, supportive, caring, and dedicated to your profession. I would also

like to thank my dissertation committee members—Dr. Linda Purrington and Dr. Kazue

Masuyama—for providing guidance, advice, and encouragement that greatly improved my study

and resulting paper. The three of you exemplify the kind of education professional I hope to

become.

I would also like to thank my fellow cadre mates for making my years at Pepperdine

enjoyable and memorable. I will always treasure the camaraderie and consider myself lucky to

be able to count every member of CFKA16 as a friend and colleague. I would especially like to

thank Angel Hamane, Vicky Kim, and Amanda Schulze for being the best travel-mates,

roommates, and study-mates ever. I look forward to moving our weekly online conversations

from Skype to the latest virtual gaming world!

Thanks also to the faculty and staff at Pepperdine University’s Graduate School of

Education and Psychology. You provided excellent guidance and support within a hybrid

program that made distance-learning work.

Thank you to my family and colleagues who have supported me throughout this journey.

Thank you to my parents, George and Elaine, who instilled in us the importance of education

while we were growing up. To my colleagues JoAnn Aguirre, Esther Hattingh, and Francie

Dillon: thank you for allowing me to bounce ideas off of you. Our informal talks about education

and technology helped solidify all the ideas that were swirling in my head. Junko Ito and Haruko

x

Sakakibara, thank you so much for your continued support in the use of technology in language

learning.

One of the most enjoyable aspects of this endeavor was the opportunity to work with the

students in this study. Thank you to the participants for the time spent playing the game and for

providing valuable feedback and insightful comments.

I would not have been able to conduct my study without the ARIS platform. Thank you

to the ARIS developers and the ARIS user’s forum members. I look forward to seeing the

continued growth and development of ARIS.

Last, and certainly not least, I would like to thank my husband and best friend Phil for

supporting me 100% throughout my studies. You were always there to proofread, cook dinner,

and pick me up at the airport from yet another school-related trip.

xi

VITA

EDUCATION

2014 Doctorate in Education in Learning Technologies, Pepperdine University,

Graduate School of Education and Psychology. Los Angeles, California.

1997 Master of Education in Educational Technology, University of Hawaii, Manoa.

Honolulu, Hawaii.

1991 Master of Science in Computer Science, University of Southern California. Los

Angeles, California.

1985 Bachelor of Science in Computer Science, University of Hawaii, Manoa.

Honolulu, Hawaii.

TEACHING EXPERIENCE

2009-2012 Instructor, California State University, Sacramento.

EDS 113: Introduction to Technology-Based Teaching Strategies in Career

Technical Education

1997-1998 Instructor, University of Hawaii, Manoa.

EDCI 571: Practicum in Curriculum Development

ETEC 503: Technology Skills for Educators

ETEC 442: Computers in Education

PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE

2011-2013 Learning Technologist, College of Continuing Education, California State

University, Sacramento

2006-2011 Online Learning Services Manager, College of Continuing Education, California

State University, Sacramento

1999-2006 Information Technology Consultant

Academic Technology and Creative Services / University Computing &

Communications Services, California State University, Sacramento

1997-1998 Computer Specialist, Curriculum Research & Development Group, University of

Hawaii, Manoa

1990-1993 Expert System Software Engineer, Systems Integration Group, TRW, Inc.,

Redondo Beach, California

1986-1990 Test System Software Engineer, Space & Technology Group, TRW, Inc.,

Redondo Beach, California

xii

ABSTRACT

Communication is a key component in learning a second language (L2). As important as the

ability to communicate in the L2 is the willingness to use the L2 or, what has been identified in

the literature as Willingness to Communicate (WTC). Language is best learned when situated in,

and based on, real-life experiences. Technological tools such as virtual worlds, mobile devices,

and augmented reality (AR) are increasingly used to take language learning outside of the

classroom. The affordances (e.g., portability, engagement, context-sensitivity) of these tools may

have an impact on the following WTC antecedents: perceived competence, reduced L2 anxiety,

security, excitement, and responsibility. The nature of this impact suggests that an AR mobile

game may positively affect students’ WTC. The purpose of this case study was to examine

student perceptions regarding the use and design qualities of an AR mobile game in the language

learning process and the effect of these qualities on student perceptions of their WTC. Nine

students in a second-year Japanese language class at an institute of higher education in California

participated in the study by playing an AR mobile game for three weeks. Data were collected

through a demographic survey, game-play observations, game artifacts in the form of images and

audio, game log data, and interviews. Findings suggest that AR mobile games can provide a

viable means to take language learning outside the classroom and into self-selected spaces to

affect positively students’ WTC. From this investigation, it is evident that AR mobile language

learning games can: (a) extend learning outside the classroom, (b) reduce L2 anxiety, and (c)

promote personalized learning.

1

Chapter 1: Introduction

As the global playing field becomes flatter, opportunities for people to collaborate

transnationally in academic, scientific, and manufacturing projects are becoming more numerous.

Friedman (2007) describes the concept of “flatness” as “how more people can plug, play,

compete, connect, and collaborate with more equal power than ever before” (p. 2). Preparing the

workforce through the inclusion of globalization in higher education is now paramount.

Proficiency in a foreign language is a necessary and important element of globalization studies

(Brustein, 2007). Yankelovich (2005, p. 4) identified “the need to understand other cultures and

languages” as one of five trends to be embraced in higher education circles by the year 2015 in

order for the United States to keep up with, and adapt to, the outside world. In this respect, there

is no denying that learning a foreign language is an essential means for today’s learners to

become citizens of the world.

Context

Communication is a key component in learning a second language (L2). However, as

important as the ability to communicate in the L2 is the willingness to use the L2 or, what has

been identified in the literature as Willingness to Communicate (WTC). WTC in an L2 has been

defined as a learner’s “readiness to enter into discourse at a particular time with a specific person

or persons, using a L2” (MacIntyre, Dörnyei, Clément, & Noels, 1998, p. 547). In other words,

WTC is the likelihood of a person initiating communication in an L2 with others in a specific

situation. Research has shown that learners who demonstrate a higher level of WTC have

increased frequency and greater amount of L2 usage (Clément, Baker, & MacIntyre, 2003;

Hashimoto, 2002; MacIntyre & Charos, 1996; Yashima, Zenuk-Nishide, & Shimizu, 2004).

2

Language is best learned when situated in, and based on, real-life experiences (Dewey,

1938; Lave & Wenger, 1991). Indeed, research has shown that in order to be effective, language

learning cannot take place solely within the confines of a classroom; it is most successful when

used in real-life situations, ideally in a country where the language is spoken (Inozu,

Sahinkarakas, & Yumru, 2010; Ogata & Yano, 2004; Riney & Flege, 1998). First language (L1)

acquisition typically takes place at an early age in the home environment. However, learning a

foreign language (L2) in a country where it is not designated as an official language can be a

challenge. Even in a country as linguistically diverse as the United States, it can be difficult to

find opportunities to practice a foreign language outside of the classroom in authentic situations.

A number of technological tools have been used to take language learning outside of the

classroom: (a) virtual worlds, (b) mobile devices, and (c) augmented reality (AR).

Virtual worlds, such as Second Life, have been used as extensions of language

classrooms in lieu of language learners being physically present in countries where the target

language is the official language (Jauregi, Canto, de Graaff, Koenraad, & Moonen, 2011;

O’Brien & Levy, 2008; Yu, Song, Resta, Chiu, & Jang, 2013). Virtual worlds are computer-

generated three-dimensional simulations in which users are represented on-screen by personal

avatars, and the users can communicate with others through gestures, text, and voice. Studies

suggest that experiences in virtual worlds enhance participants’ awareness of the target language,

and participants have expressed positive attitudes toward language learning in virtual worlds

(Peterson, 2010; Wehner, Gump, & Downey, 2011; Zheng, Young, Brewer, & Wagner, 2009).

The mobile device is another technological tool that has been used to take language

learning beyond the classroom. Cell phones, personal digital assistants (PDAs), and more

recently, smartphones and tablet computers can enhance language lessons. Mobile technologies

3

afford several characteristics that make them an ideal platform for language learning: portability,

social interactivity, context sensitivity, connectivity, and individuality (Klopfer, Squire, &

Jenkins, 2002). Studies show how mobile devices have been used for language learning through

dictionary lookups (Meurant, 2007; Petersen & Markiewicz, 2008), review exercises (Lin, Kajita,

& Mase, 2007), vocabulary exercises via text messaging and email (Kiernan & Aizawa, 2004;

Levy & Kennedy, 2005; Thornton & Houser, 2005), podcasts (Abdous, Camarena, & Facer,

2009), and e-books (Fisher et al., 2009).

A third technology tool is AR, which brings elements of the virtual world into the real

world through the use of mobile devices. Although numerous studies have been conducted

separately on mobile devices and virtual worlds for language learning (Abdous et al., 2009;

Meurant, 2007; Peterson, 2010), little research has been done on using the real world, augmented

by mobile technology, for language learning. Within a virtual world, the learner is immersed in

an environment that exists fully on a computer, whereas in AR, students interact with the real

world using mobile computers that can determine their location to facilitate location-based

learning. AR enhances the real world through the use of location-based technologies such as

markerless Global Positioning System (GPS) receivers or marker-based strategically-placed 2D

barcodes (also known as Quick Response or QR codes). These markers are computer-generated

codes that can be included on physical items such as posters, business cards, and merchandise

(Johnson, Levine, Smith, & Stone, 2010). See Figure 1 for an example of a 2D barcode. Many

mobile devices contain software that enables the scanning and interpretation of these codes,

which then redirects the user to a website or displays other content, such as images or contact

information. Student-owned mobile devices such as smartphones and tablet computers that

contain GPS or 2D barcode-scanning software are now becoming ubiquitous on college

4

campuses (Zickuhr, 2011), making the mobile device an excellent platform for AR software and

taking language learning outside of the classroom.

Figure 1. Example of a 2D barcode.

AR technology has been in existence for approximately 20 years as documented in

Azuma’s (1997) seminal paper on early AR systems. These early systems were used in

disciplines such as medicine, robotics, entertainment, manufacturing, and military navigation and

required cumbersome head-mounted displays (Caudell & Mizell, 1992). More recently, mobile

AR applications for learning have been developed and used mainly in the area of science inquiry

(Bressler, 2012; Mathews, Holden, Jan, & Martin, 2008; Squire & Jan, 2007; Squire & Klopfer,

2007). The few studies that have been conducted on AR language learning used 2D barcode (Liu,

Tan, & Chu, 2007) or RFID (Radio Frequency IDentification) technologies (Ogata & Yano,

2004) rather than the markerless automatic location detection that comes with GPS or through

Wi-Fi positioning. One notable exception is the Mentira project which used the Wi-Fi

positioning technology on Apple iPods (Holden & Sykes, 2011). Mentira was created for use in

upper division Spanish classes at the University of New Mexico using an AR game development

platform called ARIS (Augmented Reality for Interactive Storytelling: http://arisgames.org/).

However, the Wi-Fi positioning technology, although more accessible than 2D barcode or RFID

technologies, is not as reliable or accurate as GPS because of variability in Wi-Fi signal strength

(Klopfer, 2008), and reliance on the integrity of Wi-Fi database entries.

5

The use of smartphones by college students has increased significantly in the past few

years. According to eMarketer data, at the end of 2011 approximately 60% of college students

owned a smartphone, which was a 30% increase from 2010 (Boyle, 2012). Students use the

computing capabilities of their smartphones for various activities that range from reading books

(25%) to accessing the Internet (90%). These data also showed that almost three-quarters of the

students played games on their smartphones at least once a week.

It is well documented that video games are a popular pastime with college-aged adults

(Jones, 2003; Lenhart, Jones, & Macgill, 2008; Ogletree & Drake, 2007). Online games are no

exception. According to an eMarketer survey, approximately 45% of online gamers fall within

the 18-34 year old age group (Phillips, 2011).

The amount of time that a student spends in a classroom in a typical undergraduate

program is insufficient to achieve oral proficiency in a foreign language (Malone, Christian,

Johnson, & Rifkin, 2003). The Foreign Service Institute (FSI) determined the amount of time it

takes their students to achieve certain levels of oral proficiency in different languages. As an

example, a Category I language such as French or Spanish takes 575-600 class hours to achieve

level 3 (general professional proficiency) on the Interagency Language Roundtable (ILR) scale.

At the opposite end, a Category III language such as Arabic or Japanese, which is considered to

be exceptionally difficult for native English speakers, takes 2200 class hours to achieve ILR

level 3 (Malone & Montee, 2010). According to Malone et al. (2003), the typical undergraduate

foreign language program after two years offers only 180 class hours. Even if the number of

hours were to be doubled to reflect a four-year language program, there would still be a great

deficiency in the number of classroom hours compared to the number of hours required for

6

proficiency. Hence, in order to move closer to proficiency, students would benefit by spending

more hours outside of the classroom improving their oral skills.

Given the popularity of smartphones and online games among college students, the

benefits of AR technology in situated learning, the importance of WTC in an L2, and the hours

of study required to become proficient in a language, there appears to be a need to explore the

efficacy of the application of the combined technologies of AR, mobile devices, and games in

support of WTC in language learning outside of the classroom.

In the U.S., Japanese language learning is categorized as Foreign Language (FL) learning

in which students are exposed to the Japanese language mainly in the classroom because it is not

the official language of the U.S. This stands in contrast to Second Language (SL) learning in

which students are exposed to the target language (TL) both inside and outside of the classroom.

For example, non-Japanese students who study Japanese in Japan would be considered SL

learners. AR can bring the experience of FL learning closer to that of SL learning by simulating

the experiences that SL learners enjoy by simply being in the TL country.

The delivery mode of an FL class at the university level is typically not conducive to

situated learning: the instructor is often the only native speaker with whom the students interact.

Moreover, this interaction tends to be in a lecture format and does not necessarily include social

engagement. In a mobile AR game, however, places on campus such as a bookstore, coffee shop,

or fast-food restaurant similar to those that a student may encounter in Japan can be used as

learning locations. The students will be able to interact appropriately with non-player characters

(NPCs) such as fast-food clerks or other customers.

This study was conducted with Japanese language students at a public university in

California. To ensure confidentiality, the university will be referred to as California University

7

(CU) throughout this dissertation. Names of buildings and locations on the campus have also

been changed or rendered unreadable for confidentiality purposes. The Japanese language

program at this university is part of the East Asian language department. The department awards

both major and minor degrees in the Japanese language. The university requires all Bachelor of

Arts candidates to complete three courses in one foreign language and Bachelor of Science

candidates as required in their major program. In the Spring 2013 quarter, there were

approximately 300 students enrolled in Japanese language classes at this university.

The Japanese language classes are held Monday through Friday for 50 minutes per

session. A typical class consists of 25 students and is taught by one instructor. The classes are

taught in a traditional, lecture-based format.

In a 2012 survey of students who use the computer rooms at this university, 49.2% of the

respondents indicated that they owned a smartphone. This is an increase from 34.9% in the

previous year, based on data from a similar survey. An informal survey administered as part of a

pilot study for an AR mobile game in the Spring 2013 quarter to students in an intermediate

Japanese course found that 66% of the students owned smartphones and 63% of the students

played video games on either their smartphones or computers.

Purpose Statement

The purpose of this study was to examine student perceptions regarding the use and

design qualities of an augmented reality mobile game in a Japanese language course at an

institute of higher education in California. This study explored if and how the game’s use and

design qualities affected students’ perceptions of their Willingness to Communicate in Japanese.

8

Research Questions

This study addressed the following research questions:

1. How do students participating in a second-year Japanese language course at a

California public university describe the ways in which playing a mobile AR game influenced

their WTC in the Japanese language?

2. What characteristics of a mobile AR game do students participating in a second-year

Japanese language course at a California public university attribute to influencing their WTC in

the Japanese language?

The individual student cases formed a multiple case study, which yielded greater insight

into AR mobile language learning experiences through both individual and cross-case analysis

(Miles & Huberman, 1994; Yin, 2009). According to Miles and Huberman (1994), reasons for

using cross-case analysis include enhancement of generalizability and “to deepen understanding

and explanation” (p. 173, emphasis in the original). They further state that “Multiple cases not

only pin down the specific conditions under which a finding will occur but also help us form the

more general categories of how those conditions may be related” (p. 173).

Delimitations

Delimitations of the research included the study location, timeframe, and sample. The

study took place at an institution of higher education in California during the Fall 2013 quarter.

All students enrolled in four sections of a second-year Japanese language class were considered

eligible to participate in this study.

Limitations

A limitation of this study was the sample size. As it was a requirement to have access to

an iPhone, this disqualified students who did not own smartphones or those who had other types

9

of smartphones such as Android or Blackberry devices. Another limitation was that the

participants were volunteers. Students who were not technologically savvy may have decided not

to volunteer because of the technological nature of the study. Since the study also investigated

WTC, students who did not feel comfortable communicating in Japanese may not have

volunteered to participate in the study. Therefore, the students who participated in this study may

not have been representative of other students enrolled in the course.

Timing and schedules were also limitations. Since this university runs on a quarter

system, there was only a small window of time that could be used for this study that did not

impinge on the students’ final exam schedules.

Assumptions

It was assumed that all participants in this study would be truthful and candid in their

responses in the survey and interview questions. The researcher selected the topic of inquiry.

However, for the purpose of this study, researcher bias was eliminated as much as possible. To

ensure objectivity, the Pepperdine Graduate and Professional Schools Institutional Review Board

(IRB) assessed research design and data collection strategies. This study also assumed that

language learning could be enhanced by technology.

Terminology

The following definitions of key terms and concepts will be used throughout this paper.

2D barcode. An optically encoded machine-readable 2-dimensional representation of

data. The data are usually retrieved with an optical scanner or camera.

Augmented reality (AR). “A situation in which a real world context is dynamically

overlaid with coherent location or context sensitive virtual information” (Klopfer & Squire, 2008,

p. 205).

10

Global Positioning System (GPS). An electronic navigation system that determines the

user’s location within approximately three meters. GPS only works outdoors and in locations

where the device has line-of-sight view of multiple GPS satellites (http://www.gps.gov/).

iOS. Operating system for Apple mobile devices such as the iPhone, iPod Touch, and

iPad (http://www.apple.com/ios/).

Marked AR. AR that uses 2D barcodes or RFID tags to provide location-specific

information as input to the application running on a mobile device (Pence, 2011).

Markerless AR. AR that uses the physical location data from a GPS receiver on the

mobile device as input to the application running on a mobile device (Pence, 2011). Wi-Fi

positioning systems provides similar functionality.

Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Game (MMORPG). A genre of online games

in which many players interact with fictional characters and each other in a virtual world.

Non-player character (NPC). A fictional character generated and controlled by gaming

software.

Personal Digital Assistant (PDA). A palm-size mobile computer, typically with a touch-

screen interface.

Short Message Service (SMS). System that allows mobile phone users to send and receive

text messages.

Smartphone. A mobile phone that has advanced features such as a camera, GPS, Internet

access, and the capability to run software applications. Smartphones typically have touch screens.

Tablet computer. A mobile computer that is larger than a mobile phone but smaller than a

laptop. Tablet computers typically have touch screens.

11

Virtual world. “Persistent, avatar-based social spaces that provide players or participants

with the ability to engage in long-term, coordinated conjoined action” (Thomas & Brown, 2009,

p. 37). Avatars interact with other avatars as they navigate through the virtual world (Williamson,

2009).

Wi-Fi. A short-range wireless computer network. Wi-Fi often serves as a gateway to the

Internet.

Wi-Fi Positioning. Technique used to approximate a device’s position by referencing

known Wi-Fi access points.

Importance of the Study

The contribution of AR mobile games to the language learning experience, especially in

the area of WTC, needs to be examined. In this study, students who are not exposed daily to

Japanese speakers were able to interact with a Japanese-speaking and writing NPC in the virtual

environment of the game, thus also increasing their time spent in language learning outside of the

classroom. AR allows students to experience situated learning, which occurs through social

engagement in context and not simply through the acquisition of knowledge (Lave & Wenger,

1991).

Studies of language learning have been conducted in the areas of virtual worlds and

mobile learning (Abdous et al., 2009; Meurant, 2007; Peterson, 2010), however little research

has been carried out using the real world for language learning, augmented by mobile technology.

An investigation that bridges the gap between these two areas of research was necessary.

This study targeted WTC in the Japanese language; however, it is anticipated that the

outcome will contribute to a deeper understanding of how mobile AR game-based learning might

be used to foster learning in other languages.

12

Little research to date has been done on the use of mobile AR technology to situate

language learning, specifically in the area of WTC in the real world, outside of the traditional

higher education classroom. This study contributes to the body of knowledge on language

learning and andragogy but may well also contribute to second language acquisition and

pedagogy.

Organization of the Study

This study is organized into five chapters, a reference, and appendices. Chapter 1

introduced the study. It included the context of the study, purpose statement, research questions,

delimitations, limitations, assumptions, terminology, and importance of the study. Chapter 2

presents a review of the related literature on the conceptual areas of situated learning, mobile

learning, video games and language learning, virtual worlds, augmented reality, andragogy,

second language acquisition, and willingness to communicate in a second language. Chapter 3

describes the research design and methodology of the study. In Chapter 4, the data findings are

presented. Chapter 5 offers an analysis of the findings, a presentation of conclusions, and

recommendations for further research.

13

Chapter 2: Conceptual Foundation

The main conceptual areas for this study are situated learning, mobile learning, video

games and language learning, virtual worlds, augmented reality (AR), and willingness to

communicate (WTC) in a second language. Each of these components contributes to an

understanding of the need for an exploration of mobile AR games in foreign language learning.

Language Learning

As this study focuses on the language learning experience of college-aged students, the

area of andragogy needs to be outlined. Malcolm Knowles defined andragogy as the “art and

science of helping adults learn” (1980, p. 43). This concept is in contrast to the term pedagogy,

which is the art and science of teaching children. Knowles stated that adult learners: (a) are self-

directed, (b) can draw on life experiences, (c) have social roles that affect their learning needs,

and (d) have immediate need for application of knowledge.

There are many schools of thought regarding how the first language (L1) is acquired.

Many educators would agree that this phenomenon occurs naturally in a home environment

(Lightbown & Spada, 2006). Second Language Acquisition (SLA) occurs when a learner lives in

the country where the target language (TL) is spoken. This is in contrast to Foreign Language

(FL) learning in which the learner lives in a location where the TL is not generally spoken

(Oxford & Shearin, 1994). SL learners have the benefit of experiencing the TL both inside and

outside of the classroom. FL learners, on the other hand, typically experience the TL only in a

classroom environment.

In an attempt to bring FL learning closer to that of SL learning, Terrell (1982, p. 121)

promoted the concept of a “Natural Approach” to language learning. In the Natural Approach,

14

more emphasis is placed on real communication and less on grammatical structures and

audiolingual skills.

Also with the goal to move FL learning closer to that of SL learning, Stephen Krashen

(1982) states that the optimal input for language learning should be comprehensible and set in

low anxiety situations. The input should also be interesting to the acquirer (student).

Language learning consists of the four areas of listening, speaking, reading, and writing.

This study focuses on the speaking aspect of FL learning.

Situated Learning

Brown, Collins, and Duguid (1989) assert that knowledge cannot be separated from the

situation or activity in which it is used and that in order for meaningful learning to take place, it

needs to be embedded in authentic situations. Lave and Wenger (1991) offer a similar definition:

they suggest that learning occurs through social engagement, in context, and not simply through

the acquisition of knowledge. A key component of this concept is the notion that new members

of a community participate from the boundary, or what Lave and Wenger (1991) call legitimate

peripheral participation (LPP). Although the words boundary or peripheral may seem to imply

insignificance, quite the opposite is true. Wenger (1998) states that peripherality allows for “an

approximation of full participation that gives exposure to actual practice” (p. 100). In terms of

legitimacy, “learning is not merely a condition for membership, but is itself an evolving form of

membership” (Lave & Wenger, 1991, p. 53). In other words, newcomers must be accepted and

treated as legitimate members of this community. These new members spend time observing and

learning from more experienced members of the community, until they eventually become fully-

fledged members themselves.

15

Situated language learning. In situated language learning, the community for a

language learner consists of other learners of the language along with native speakers of the L2.

Several studies on situated learning and LPP in language learning have been conducted in areas

such as university group projects (Leki, 2001), academic publishing (Flowerdew, 2000), ESL

adult immigrant experiences (Norton, 2001), graduate academic communities (Morita, 2004),

and tutored writing sessions (Young & Miller, 2004).

In a multiple case study of Japanese graduate students at a Canadian university, Morita

(2004) described the students’ experiences in participating on the periphery as newcomers to

several L2 academic communities at the university. Morita followed the students’ progression

toward becoming competent members of these communities. The study found value in inquiring

into the students’ perspectives and not just relying upon observations to understand their

participation as members of the communities.

Mobile Learning

Mobile phone usage is pervasive in the U.S. today, including on college and university

campuses. The Pew Research Center (Zickuhr, 2011) reports that 85% of Americans over the age

of 18 own a cell phone. Additionally, with the advent of smartphones and tablet computers,

mobile devices have become much more powerful than their predecessors. Klopfer, Squire, and

Jenkins (2002) describe five properties that make mobile devices attractive platforms for

learning:

Z Portability: mobile devices are small enough that they are almost always in one’s

possession

Z Social interactivity: allows for exchange of data and collaboration with other people

16

Z Context sensitivity: allows for the collection of data based on one’s current location

and environment

Z Connectivity: mobile devices can be connected to other devices through wireless

access points and cell phone networks thus allowing for a true shared environment

Z Individuality: provides for individualized scaffolding that is customized to the user.

Writing web logs, or what is more commonly referred to as ‘blogging’, is one way of

taking advantage of the mobile platform for learning. Huang, Jeng, and Huang (2009)

investigated the effects of mobile blogging on learning at a university in Taiwan. This study

found that mobile blogging allowed for better integration of blogging into the students’ daily

lives because of its mobility aspect. Students were able to blog at any time or place without the

need to sit in front of a computer. As a result, the researchers determined that this system

provided a more authentic context for learning.

Mobile language learning. Several studies have explored the use of mobile devices for

language learning. Cavus and Ibrahim (2009) and Lu (2008) investigated the use of Short

Message Service (SMS) as a means for studying vocabulary. Lu’s study found that students

using mobile devices had greater vocabulary gains than the control group that used traditional

paper-based methods for studying vocabulary. The participants in the mobile device group also

showed positive attitudes toward learning via mobile phone. All the participants in Cavus and

Ibrahim’s study reported that they enjoyed using mobile devices to study vocabulary as well. In

their study of mobile community blogs for language learning, Petersen, Chabert, and Divitini

(2006) found that a community blog extends learning outside of the classroom and facilitates

collaboration between students.

17

Situated mobile learning. Mobile technologies support situated learning by the distinct

characteristic of the user always having their mobile devices on their person. Mobile devices can

also take advantage of ‘context-awareness’ (Naismith, Lonsdale, Vavoula, & Sharples, 2004, p.

14) by using information from the environment such as location through the GPS receiver in the

mobile device. Ogata et al. (2006) found that with the assistance of a mobile system called

Language-learning Outside the Classroom with Handhelds (LOCH), students were active

participants in gathering real-life situational information such as photos to complete tasks. The

students perceived that the LOCH system aided them in the learning of local expressions and

allowed them to practice situationally what they learned in class. The instructors reported that

students seemed more confident in speaking the language after using the LOCH system to

practice in real-life social situations.

There may be challenges to learning via mobile technology. Cognition overload can

occur with small screen sizes and the need to jump from screen to screen in order to complete a

task. Kim and Kim (2012) looked at the effects of screen size on vocabulary learning for Korean

middle-school students studying English and found that the smaller screen sizes created higher

cognitive loads for the students. In their study of the AR game Alien Contact! with high-school

students, Dunleavy, Dede, and Mitchell (2009) found that students reported feeling “frequently

overwhelmed and confused with the amount of material and complexity of tasks” (p. 17) that

needed to be performed in order to play the game.

Video Games and Language Learning

History of Computer-Aided Language Learning (CALL). As its name suggests, the

field of Computer-Aided Language Learning involves the use of computers in language teaching

and learning. In the 1960s and 1970s, mainframe and mini-computers were used for drill-and-

18

practice exercises in which the computer performed the role of a tutor (Bush, 2008; Warschauer,

1996). One of the better-known learning systems was called Programmed Logic for Automatic

Teaching Operations (PLATO), created by the University of Illinois in 1960 (Sanders, 1995) and

later purchased by the Control Data Corporation (Hart, 1995). The PLATO IV system consisted

of large stations with plasma panels rather than the typical text-based Cathode Ray Tube (CRT)

screens that were common at that time. In addition to offering a crisper display, these plasma

panels could also display graphics and foreign language fonts (Hart, 1995). These stations were

connected to a timeshared mainframe computer, which allowed multiple users to access the same

computer resources simultaneously.

In the late 1970s and 1980s, the personal computer became widely available. Users did

not need to rely on having access to a timeshared mainframe computer. Instead, they had a

powerful machine of their own to use at any time. Drill-and-practice exercises were still

available through floppy disks and other media. However, language instructors could now create

their own learning activities that incorporated multimedia through the use of authoring software

such as HyperCard (Warschauer, 1996).

With the start of widespread availability of the World Wide Web in the 1990s, resources

for language learning grew rapidly. As anyone could create web pages, authentic content in an

L2 became readily available. Language instructors were also able to take advantage of web-

based game authoring software such as Quia (http://www.quia.com) and Hot Potatoes

(http://hotpot.uvic.ca/) to create their own learning activities and make them available to anyone

on the Internet. Students could also subscribe to instructor-created material through the RSS

(Rich Site Summary or Really Simple Syndication) technology, which pushes podcast and blog

entries to users. Synchronous communication through free Internet applications such as Skype

19

(http://www.skype.com) and Google Hangouts (http://www.google.com/+/learnmore/hangouts/)

allow learners to communicate in the L2 in real-time with their instructors or other native

speakers.

Games. One form of CALL is computer or video gaming. Although many definitions for

the term game exist (Costikyan, 2002; K. Salen & Zimmerman, 2004), this study uses the

following definition: “A game is a form of play with goals and structures” (Maroney, 2001, p. 1).

Much of the research involving games and language learning is based on games

specifically created for language learning (Hubbard, 1991; Warschauer & Healey, 1998; Yip &

Kwan, 2006). However, recent research has shown that games not specifically meant for

classroom use are being used to supplement language learning. In their review of Web 2.0 tools

(for example blogs and wikis) and the use of games in language learning, Sykes, Oskoz, and

Thorne (2008) found that these immersive digital spaces facilitate the blurring of lines between

study and play, so that students may transition seamlessly between learner and player, or

information consumer and producer.

The results of a study that used the MMORPG game EverQuest 2 as a tool for learning

English as a second language showed that for intermediate and advanced English learners,

participation in the game increased their vocabulary by 40%. The researchers also concluded that

this MMORPG provided motivation for learning through a desire to communicate with players

whose native language was the students’ target language (Rankin, Gold, & Gooch, 2006).

Virtual Worlds

Situated learning can occur through the use of technology, particularly in virtual worlds.

Thomas and Brown (2009, p. 1) define virtual worlds as “persistent, avatar-based social spaces

20

that provide players or participants with the ability to engage in long-term, coordinated conjoined

action.” Characteristics of virtual worlds include:

Z Persistence: world exists even after the user exits the world

Z Shared Space in Real Time/Synchronous: multiple users participate in the world

simultaneously

Z Virtual Representation of Self: avatars represent users in the world

Z Networked Computers: participants gain access to the world through networked

computers

Z Interactivity: users communicate and collaborate with each other in the world (Bell,

2008; Williamson, 2009).

One of the largest virtual worlds is Second Life (http://secondlife.com). Participants

access Second Life via the Internet through a free application available on multiple computer

platforms from Linden Lab (http://lindenlab.com). In Second Life, users (residents) create three-

dimensional avatars to represent their online persona in the virtual world, and residents can

communicate with each other via gesture, text, or voice. See Figure 2 for a screenshot of a class

meeting in Second Life.

Figure 2. Screenshot of a class meeting within the Second Life virtual world.

Screenshot reproduced with permission of Linden Lab.

21

Virtual worlds and language learning. Virtual worlds have been used as extensions of

language classrooms in lieu of language learners being physically present in countries where the

target language is the official language. According to their review of virtual worlds and online

games in language learning, Thorne, Black, and Sykes (2009) found that virtual worlds such as

Second Life promoted interactions similar to what students would experience in real life.

Boundaries, which separated language study from social life, were blurred while in a virtual

world.

Affective factors related to language learning have also been studied in virtual worlds.

Self-efficacy and attitude were measured in a study of students in China learning English with

Quest Atlantis (Zheng et al., 2009). The students solved quests in English alongside American,

Australian, and Singaporean native English speakers. Compared to the control group, the

students who played Quest Atlantis rated themselves higher in self-efficacy in English usage, e-

communication, and attitude toward English.

In their study of Spanish learners at a southeastern U.S. university, Wehner et al. (2011)

found that the group using Second Life reported more positive feelings in the area of motivation

as compared to the control group. The learners in the virtual world also reported lower levels of

anxiety.

Situated learning in virtual worlds. Virtual worlds can contain digital artifacts and

NPCs that can simulate situated learning and LPP. The River City MUVE (Multi-User Virtual

Environment) is an example of a virtual world that implements an internship model that allows

the player to experience LPP. Designed for middle-school science classes, River City MUVE

takes students back in time to the 1800s to help solve the city’s health problems. This study used

22

a design-based methodology; the researchers conducted several iterations of design and

evaluation of the virtual worlds (Dede, Nelson, Ketelhut, Clarke, & Bowman, 2004).

Augmented Reality

AR has been defined as “A situation in which a real world context is dynamically

overlaid with coherent location or context sensitive virtual information” (Klopfer & Squire, 2008,

p. 205). Mobile technologies offer features such as portability, connectivity, and individuality

(Klopfer et al., 2002), which can be used to facilitate and enhance learning in a way that merges

the virtual worlds and real world environments. By using location-based technologies such as

Wi-Fi or GPS on mobile devices, AR software can provide computer-generated elements such as

NPCs that augment reality by appearing on-screen when the player moves to certain

geographical locations.

AR technology has been in existence for approximately 20 years, as documented in

Azuma’s (1997) seminal paper on early AR systems. These early designs were used in

disciplines such as medicine, robotics, entertainment, as well as military navigation and required

the use of cumbersome head-mounted displays.

AR on mobile devices can encourage transfer of learning which is a challenge for many

educators (Klopfer, 2008). Transfer is defined as the “ability to extend what has been learned in

one context to new contexts” (Bransford, Brown, & Cocking, 2000, p. 51). In an education

setting, this usually means being able to apply what was learned in the classroom to situations in

the real world. AR places the learner in the real world while learning is taking place; therefore,

the problem of transfer may be minimized.

AR in science inquiry. Many AR games have been designed and implemented in the

subject area of science inquiry. In Environmental Detectives (Squire & Klopfer, 2007), high-

23

school and university students played the role of environmental engineers who investigated a

chemical spill. Students used handheld Pocket PCs equipped with GPS devices to take virtual

environmental samples with the goal of locating the source of the chemical spill. Students had

access to virtual experts on their handheld devices to aid in their investigation.

Another AR game in the field of environmental science is Mad City Mystery, which took

place on the University of Wisconsin, Madison campus (Squire & Jan, 2007). The goal of the

game was to determine the cause of death of a fictitious friend. However, the ultimate

educational objective of the game was to help students develop investigative and inquiry skills

through the research required to determine the friend’s cause of death. Participants in this study

ranged from elementary through high-school students who took on various roles such as doctors,

environmental specialists, and government officials. Each role gave the participants different

responsibilities and capabilities. In order to reach the goal, the participants needed to collaborate.

In Alien Contact! (Dunleavy et al., 2009), high school students used math, language arts,

and science skills to find out why aliens landed on Earth. As students moved around an area,

icons representing artifacts and people were superimposed on a map on their handheld devices.

When the students were within 30 feet of an artifact or person, the AR software displayed

relevant video, audio, and text files to the students.

AR in libraries, museums, and zoos. AR has also been used in venues not necessarily

designated as traditional academic locations, such as libraries, museums, and zoos. Many AR

projects that take place in libraries have used the marker technology of QR codes (Elmore &

Stephens, 2012; Pons, Vallés, Abarca, & Rubio, 2011; Wells, 2012), most likely due to the fact

that GPS does not work well indoors. One example of AR usage in a library took place at the

University of the Pacific where first-year music majors were introduced to the library’s music

24

collection via a QR scavenger hunt (Wells, 2012). The majority of the students felt that the QR

code activity helped them become better acquainted with the library services and thought that the

activity was fun or entertaining.

Museum guides on mobile devices are becoming more commonplace. Attractions such as

the Getty Museum in Los Angeles (http://www.getty.edu/visit/see_do/gettyguide.html) and St.

Paul’s Cathedral in London (http://www.stpauls.co.uk/Visits-Events/Sightseeing-Times-

Prices/Multimedia-Guides-Tours) provide additional information regarding their artifacts via

iPod Touches. The Getty Museum application requires the patron to enter a number

corresponding to a number posted near the work of art to display more information regarding the

artwork, and the St. Paul’s application uses interactive maps to present audiovisual information

about the cathedral.

The AR game Then Now Wow (previously called Our Minnesota) was created for the

Minnesota Historical Center and enables visitors to virtually meet and solve problems with real

historical figures via iPod Touches (Dikkers, 2012). Visitors use the mobile devices to scan QR

codes located throughout exhibits to learn more about the exhibits. Feedback from initial testers

indicated that the game was a fun and engaging learning experience.

In the AR game Zoo Scene Investigators, which took place at a zoo in Columbus, Ohio,

participants aged 10-14 years old were tasked with using clues provided in the game to find out

why an intruder broke into the zoo (Perry et al., 2008). Participants were issued handheld

computers and GPS units as well as paper worksheets with clues. The goal of this game was to

raise awareness about illegal poaching and threats to animals because of habitat loss.

AR in higher education. Digital Graffiti Gallery was created by a student at the

University of New Mexico in 2010 (Holden, 2011). In Digital Graffiti Gallery, players

25

documented graffiti found on campus by taking pictures using the mobile device’s camera and

annotating the pictures with the game’s note-taking feature. Digital Graffiti Gallery was

designed to be open-ended with limited guidance from the game. The significance and usefulness

of the game increased as participants played; for without their input, the game was just a shell.

An AR mobile campus touring system prototype was developed to guide incoming

freshmen at the Fu-Jen Catholic University in Taiwan (Chou & ChanLin, 2012). Users of the

system could obtain location-specific information such as the library’s operating hours when

they were in the vicinity of the library. Based on feedback from the pilot testing, the touring

system accomplished its goal of assisting the newcomers in navigating the 86-acre campus.

AR in language learning. Although the aforementioned studies successfully used AR

games in educational settings, they were mainly employed in science education contexts or

libraries and museums. Few studies have been conducted on the use of AR technology for

language learning. The Handheld English Language Learning Organization or HELLO system

(Liu & Chu, 2010) is a 2D barcode and handheld AR system. Using the device’s camera,

students took photos of barcodes attached to objects. The barcode was converted to data that

were used to determine the students’ location and to access learning material from a remote

database. Unlike the previous AR games however, this system did not use GPS but relied solely

on 2D barcodes. This can be problematic in that these barcodes are easily removed. This may not

pose a problem in a location where the developers have complete control over the environment,

i.e. a classroom or a building. However, for places that are publicly accessible, barcodes may be

easily removed or defaced, compromising the user’s experience.

More recently, Holden and Sykes (2011) from the University of New Mexico, created an

AR game called Mentira for use by students enrolled in a fourth semester Spanish class. The

26

main goal of Mentira was to connect students in a meaningful way to their language learning

experiences. In other words, the designers wanted students not simply to learn the language but

also to embrace the culture and location associated with the language. To that end, part of the

project included a field trip to the neighborhood of Los Griegos in Albuquerque, which has a

strong connection to the Spanish language. Before traveling to Los Griegos, game play began in

the classroom with students learning about the game narrative. The goal was to solve a murder,

and each student was assigned a different role along with clues only known by his or her

character.

Mentira was a media-rich game with 70 pages of Spanish dialogue and expository text,

150 items of visual art, and four video clips. The basic game structure involved conversations

between the player and the game’s NPCs in the form of scripted dialogues. Although the

dialogues were scripted, the player could often choose between multiple responses, and based on

this choice, different events occurred.

Students were loaned Apple iPod Touches to play the game. iPod Touches do not have

GPS capability and must rely on Wi-Fi connectivity for Internet access. However, because Wi-Fi

access in Los Griegos was not reliable, Mentira was able to determine where the student was by

requesting acknowledgement from the student that they were at a specific location such as near a

certain street sign.

Students indicated in interviews that they preferred the on-site activity of the game that

took them to Los Griegos versus the classroom activity that could be played anywhere. While

some students used Spanish only when necessary to progress through the game, others used

Spanish exclusively. The designers felt that this could be construed as evidence of the students

27

incorporating the setting and narrative of the game to take language learning outside of the

classroom.

AR and situated learning. AR allows newcomers to participate in a community of

practice, in this case language learning, from the periphery. Because of certain affordances, such

as authentic tasks in meaningful situations that mobile AR brings to language learning, the use of

AR can be viewed as a form of LPP. AR can provide the “activities, identities, artifacts, and

communities of knowledge of practice” that Lave and Wenger (1991, p. 29) associate with LPP.

In other words, mobile AR can assist new members of a community in moving from peripheral

participation to full participation.

Tool for AR development. Although there are several AR tools currently in existence,

such as Layar (http://www.layar.com) and Wikitude (http://www.wikitude.com), the ARIS

(Augmented Reality and Interactive Storytelling) system was chosen to create and deploy the

game in this study (http://arisgames.org) because of its ease of use and active online community.

The ARIS system includes a web-based game editor and an Apple iOS application. The ARIS

software was developed by David Gagnon at the University of Wisconsin, Madison and is open-

source, meaning that it is free of charge for other developers to modify and use. According to

Gagnon, ARIS was designed to “create mobile, locative, narrative-centric, interactive

experiences” (Gagnon, 2010, p. 1). The ARIS editor was also designed to be easy to use for non-

programmers. Its simple drag-and-drop interface allows game developers to concentrate on game

design and functionality instead of programming details.

After a game is developed in the ARIS editor, it is available to play using the companion

ARIS iOS application which is available as a free download from the Apple’s iTunes App Store

(http://www.apple.com/itunes/). The ARIS application runs on iOS devices such as the iPad,

28

iPhone, and iPod Touch. Upon starting the ARIS application, the player can search for nearby

games or for a particular game by its name. See Figure 3 for a screenshot of the ARIS

application’s interface consisting of a main window and tab bar.

Figure 3. ARIS application user interface on an iPhone.

Screenshot reproduced with permission from ARIS.

The following is a list of features available on the Tab Bar:

Z Quests - displays a list of active and completed quests, or tasks

Z Map - displays the player’s current location and nearby game-related objects such as

NPCs and items

29

Z Inventory - displays items currently in the player’s possession; items can be picked up

or dropped throughout the game; items can be created by the game designer or other

players through the camera and audio recorder

Z More - displays additional features such as the camera and audio recorder

Willingness to Communicate in L2

For many, the fundamental purpose for learning a language is to be able to communicate

in the L2. However, competence in the L2 may not be enough. Learners must also be willing to

communicate in the L2. Therefore, the concept of Willingness to Communicate (WTC) has been

declared an integral component of language learning and necessary to achieve the end goal of

communicating in an L2 (Hashimoto, 2002; MacIntyre et al., 1998). MacIntyre et al. (1998, p.

547) defined WTC in a second language as “a readiness to enter into discourse at a particular

time with a specific person or persons, using a L2.” In other words, WTC is the likelihood of a

person initiating communication in an L2 with others in a specific situation. Studies have shown

that a person’s WTC affects the frequency and amount of second language communication that

person uses (Clément et al., 2003; Yashima et al., 2004).

The concept of WTC originated in L1 studies by McCroskey and Richmond (1987). In

their article “Willingness to Communicate: A Cognitive View,” McCroskey and Richmond

(1990) referred to the variables which they believed to affect WTC as antecedents. This current

study uses the terms variables and antecedents interchangeably.

MacIntyre et al. (1998) developed a model that describes variables that influence WTC in

an L2 (see Figure 4). In this model, WTC is influenced by both situational variables (layers I, II,

and III) and enduring variables (layers IV, V, and VI) and suggests that WTC is a composite

variable influenced by these other variables.

30

Figure 4. Model of variables influencing WTC.

From “Conceptualizing Willingness to Communicate in a L2: A Situational Model of L2

Confidence and Affiliation,” by P.D. MacIntyre, Z. Dörnyei, R. Clément, and K. A. Noels, 1998,

The Modern Language Journal, 82, p. 547. Copyright by John Wiley and Sons. Reprinted with

permission.

Trait variables. Trait variables such as personality type (introvert or extravert),

motivation, anxiety, perceived competence, situation, and integrativeness, or “inclination to

interact or identify with the L2 community” (Peng, 2007, p. 38), have been found to affect L2

WTC (Hashimoto, 2002; MacIntyre & Charos, 1996; Peng, 2007; Yashima et al., 2004).

Perceived competence occurs when learners feel that they have the capability to

communicate effectively in certain situations (MacIntyre et al., 1998). A reduction of L2 anxiety

occurs when the learners do not have a fear of communicating in the L2 (McCroskey &

Richmond, 1990).

The current study focuses on the perceived effect that AR games have on students’ WTC.

Two of the WTC trait variables—perceived competence and L2 anxiety—will be examined.

31

Researchers have also found that among all variables, perceived competence and L2 anxiety

(also called communication apprehension in some studies) were found to be the best predictors

of WTC (Baker & MacIntyre, 2000; MacIntyre & Charos, 1996). Therefore, it stands to reason

that if AR mobile games can affect either or both of these variables, the games can also affect

WTC. The trait variables that cannot be affected by the game, such as integrative motivation or

personality, are not included in this study.

Figure 5 is a portion of MacIntyre and Charos’ (1996) path model that describes the

relationships found among L2 variables in their study. The researchers examined WTC in adult

French learners in Canada. Path analysis can be used to examine situations in which there is what

Streiner (2005, p. 115) calls “chains of influence”. The numbers attached to the lines represent

path coefficients in which positive numbers indicate positive relationships and negative numbers

indicate negative relationships. This model shows, among several other relationships, that L2

anxiety negatively affects perceived competence and L2 WTC. The model also demonstrates that

perceived competence positively affects L2 WTC.

Figure 5. Portion of MacIntyre and Charos’ (1996) model of L2 communication applied to adult

French learners.

From “Personality, Attitudes, and Affect as Predictors of Second Language Communication,” by