Developing a Risk-based

Internal Audit Plan

www.theiia.org

Developing the Risk-Based Internal Audit Plan

About the IPPF

The International Professional Practices Framework®

(IPPF®) is the conceptual framework that organizes

authoritative guidance promulgated by The IIA for internal

audit professionals worldwide.

Mandatory Guidance is developed following an

established due diligence process, which includes a

period of public exposure for stakeholder input. The

mandatory elements of the IPPF are:

Core Principles for the Professional Practice of

Internal Auditing.

Definition of Internal Auditing.

Code of Ethics.

International Standards for the Professional

Practice of Internal Auditing.

Recommended Guidance includes Implementation and

Supplemental Guidance. Implementation Guidance is

designed to help internal auditors understand how to apply

and conform with the requirements of Mandatory Guidance.

About Supplemental Guidance

Supplemental Guidance offers additional information, advice, and best practices for conducting

internal audit services. It supports the Standards by addressing topical areas and sector-specific

issues in more detail than Implementation Guidance, and is endorsed by The IIA through formal

review and approval processes.

Practice Guides

Practice Guides, a type of Supplemental Guidance, provide detailed approaches, step-by-step

processes, and examples intended to support all internal auditors. Select Practice Guides focus

on:

Financial Services.

Public Sector.

Information Technology (GTAG®)

For an overview of authoritative guidance materials provided by The IIA, please visit

www.globaliia.org/standards-guidance.

www.theiia.org

1

Developing the Risk-based Internal Audit Plan

Table of Contents

Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................... 3

Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 4

Communicating the Risk-based Plan ............................................................................................ 4

Changing the Plan ........................................................................................................................ 5

Audit Plan Development Overview .............................................................................................. 5

Understanding the Organization ...................................................................................................... 6

Identifying Objectives, Strategies, and Structure ........................................................................ 6

Reviewing Key Documents ........................................................................................................... 7

Consulting with Key Stakeholders ................................................................................................ 8

Creating or Revising the Audit Universe .................................................................................... 10

Internal Audit’s Risk Assessment .................................................................................................... 11

Understanding the Significance of Independent Assessment ................................................... 11

Understanding Business Objectives, Strategies, and Risks ........................................................ 11

Documenting Risks ..................................................................................................................... 12

Risk Assessment Approaches ..................................................................................................... 14

Measuring Risks ......................................................................................................................... 16

Validating Risk Assessment with Management ......................................................................... 17

Additional Planning Considerations ............................................................................................... 18

Accommodating Management and Board Requests ................................................................. 18

Engagement Frequency and Timing........................................................................................... 18

Estimating Resources ..................................................................................................................... 20

Assessing Skills ........................................................................................................................... 20

Coordinating with Other Providers of Assurance and Consulting Services ............................... 20

Meeting Need for Additional Skills ............................................................................................ 21

Calculating Hours in Plan ........................................................................................................... 21

Drafting the Internal Audit Plan ..................................................................................................... 22

Proposing the Plan and Soliciting Feedback ................................................................................... 24

Communicating to Finalize the Plan ............................................................................................... 25

Presentation to Audit Committee .............................................................................................. 25

Presentation to Full Board ......................................................................................................... 25

Ongoing Communication ........................................................................................................... 26

Appendix A. Relevant IIA Standards and Guidance ........................................................................ 27

Appendix B. Glossary ...................................................................................................................... 28

Appendix C. Linking Objectives, Strategies, and Audit Universe .................................................... 30

Appendix D. Risk Assessment: Specific-risk Approach ................................................................... 31

Appendix E. Example: Risk Assessment Using Risk-Factor Approach ............................................ 34

www.theiia.org

2

Developing the Risk-based Internal Audit Plan

Appendix F. Example: Internal Audit Plan Summary ...................................................................... 36

Appendix G. Overview of Internal Audit Documentation .............................................................. 37

Appendix H: References and Additional Reading ........................................................................... 39

Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................ 40

www.theiia.org

3

Developing the Risk-based Internal Audit Plan

Executive Summary

In today’s business environment, effective

internal auditing requires thorough planning

coupled with nimble responsiveness to quickly

changing risks. To add value and improve an

organization’s effectiveness, internal audit

priorities should align with the organization’s

objectives and should address the risks with the

greatest potential to affect the organization’s ability to achieve those objectives.

Ensuring this alignment is the essence of Standards 2010 – Planning, 2010.A1, 2010.A2, and

2010.C1, which task the chief audit executive (CAE) with the responsibility of developing a plan of

internal audit engagements based on a risk assessment performed at least annually.

This practice guide describes a systematic approach to creating and maintaining a risk-based

internal audit plan. The CAE and assigned internal auditors work together to:

Understand the organization.

Identify, assess, and prioritize risks.

Coordinate with other providers.

Estimate resources.

Propose plan and solicit feedback.

Finalize and communicate plan.

Assess risks continuously.

Update plan and communicate updates.

The guidance is general enough to apply to the circumstances, needs, and requirements of

individual organizations. When applying the guidance, internal auditors should take into account

their organization’s level of maturity, especially the degree of integration of governance and risk

management. Auditors may need to adapt the guidance to the specifics of the industries,

geographic locations, and political jurisdictions in which their organizations operate.

Note: Appendix A lists other IIA

resources that are relevant to this

guide. Bolded terms are defined in

the glossary in Appendix B.

www.theiia.org

4

Developing the Risk-based Internal Audit Plan

Introduction

Comprehensive risk-based planning enables the

internal audit activity to properly align and focus

its limited resources to produce insightful,

proactive, and future-focused assurance and

advice on the organization’s most pressing issues.

Ensuring internal audit priorities are risk-based

requires advanced planning, and the CAE is

responsible for developing a plan of internal audit

engagements based on a risk assessment

performed at least annually (Standard 2010 –

Planning and Standard 2010.A1).

While the annual risk assessment is the minimum

requirement articulated in the Standards, today’s

rapidly changing risk landscape demands that

internal auditors assess risks frequently, even

continuously. Risk-based internal audit plans

should be dynamic and nimble. To achieve those

qualities, some CAEs update their internal audit

plan quarterly (or a similar periodic schedule), and

others consider their plans to be “rolling,” subject

to minor changes at any time.

Communicating the Risk-based Plan

When preparing an internal audit plan, the CAE

should think about how to engage stakeholders

and create an internal audit plan that generates

the most stakeholder value. Considerations

include:

Which types of internal audit engagements

will provide senior management and the

board with adequate assurance and advice

that significant risks have been mitigated

effectively?

How will the internal audit activity communicate its risk assessments and the risk-based

internal audit plan? Which types of visual depictions would help support effective

communication?

What do senior management and the board expect from the internal audit activity? In

advance, the CAE should discuss with senior management and the board how frequently they

Who Is Responsible for the Risk-

based Internal Audit Plan?

While the CAE is responsible for

the internal audit plan,

experienced internal audit

managers and internal audit staff

may perform activities in the

planning process. This guide

talks about the roles and

responsibilities of the CAE,

internal audit managers, internal

auditors, and the internal audit

activity as a whole. However, no

single approach fits all

organizations and the

arrangements vary by

organization (e.g., based on size

and resources available to the

internal audit activity).

The Standards express

requirements related to the

CAE’s risk-based plan of

engagements (2000 series) and

to individual engagement plans

(2200 series). This guide

addresses only the CAE’s risk-

based internal audit plan. The

Practice Guide “Engagement

Planning: Establishing

Engagement Objectives and

Scope” describes how to plan

individual engagements.

www.theiia.org

5

Developing the Risk-based Internal Audit Plan

expect reporting and the criteria that warrant reporting and approval of change to the audit

plan (i.e., importance and urgency of issues), as described in Standard 2060 – Reporting to

Senior Management and the Board. Internal audit policies and procedures should address

confidentiality concerns in accordance with the Code of Ethics and the Standards (Standard

2040 – Policies and Procedures and the series beginning with Standard 2330 – Documenting

Information and the series beginning with Standard 2440 – Disseminating Results).

Changing the Plan

This guide explains the steps leading to the initial creation of an internal audit plan, as well as the

requirements for formal approval of the plan, which may occur at predetermined, scheduled

intervals. In addition, the internal audit activity must respond quickly to internal and external

changes that affect the organization’s objectives and risk priorities. Organizations and external

conditions are continually changing, and new or more detailed risk information may arise during

the performance of any engagement. Internal and external auditors may discover new information

during an engagement that will prompt changes in internal audit’s comprehensive risk assessment

and the internal audit plan.

Such changes highlight the need to continuously assess risks, reevaluate risk priorities, and adjust

the plan to accommodate the new priorities. Standard 2010 – Planning advises that the CAE must

review and adjust the plan in response to changes in the organization’s business, risks, operations,

programs, systems, and controls. Later sections of the guide provide additional details about how

the CAE should manage changes to the plan.

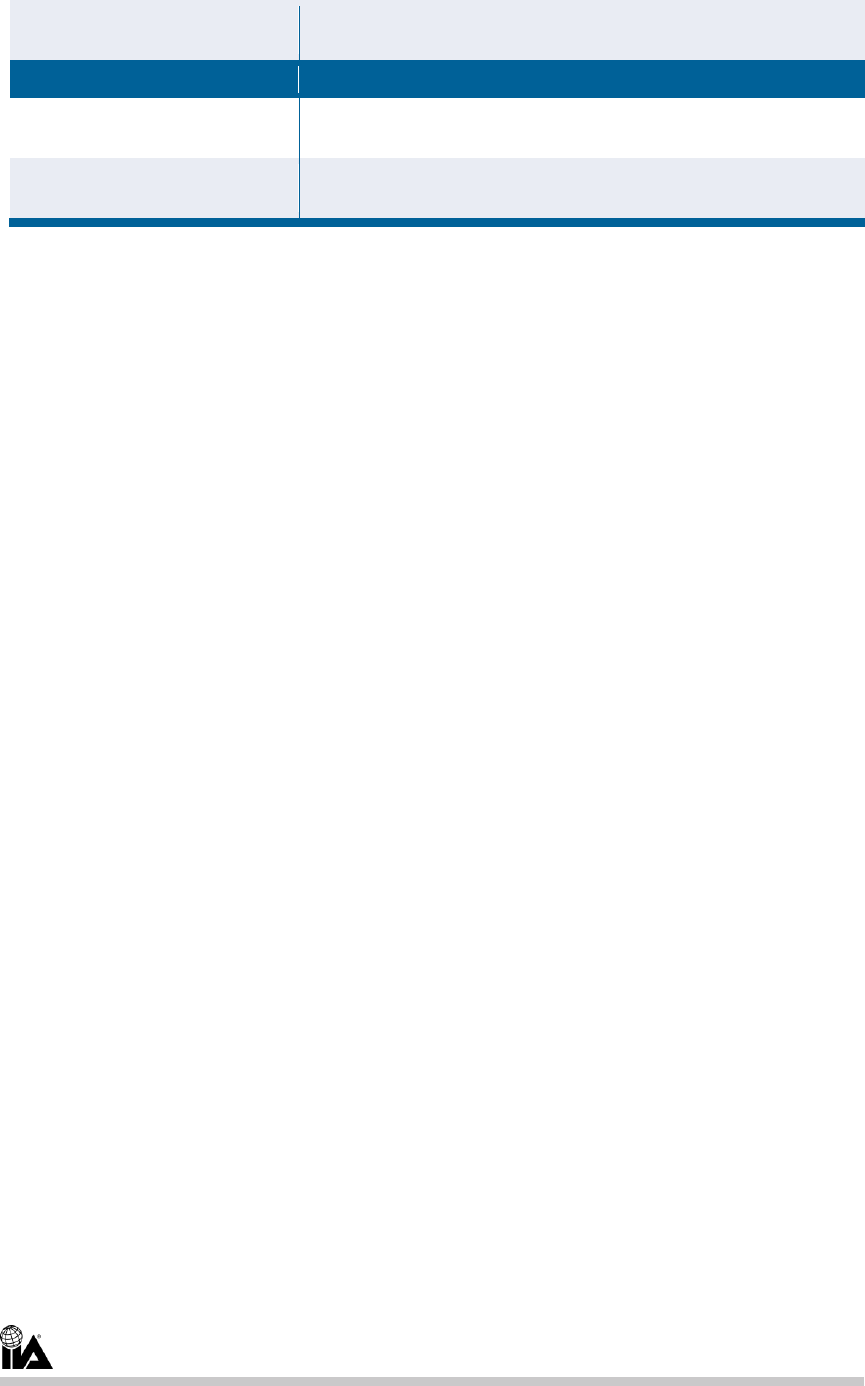

Audit Plan Development Overview

The process of establishing the internal audit plan generally includes the stages below. However,

readers should loosely interpret the concept of stages because the details of internal audit planning

vary by internal audit activity and organization. Multiple internal auditors may be working

simultaneously to prepare the internal audit plan, including the supporting risk assessment; thus,

some of the stages may overlap occasionally. CAEs typically document their preferred approach in

the internal audit activity’s policies and procedures (Standard 2040). This guide deconstructs the

stages of planning shown in Figure 1. Internal auditors should view the entire preparatory cycle as

a comprehensive effort that is responsive to organizational changes.

www.theiia.org

6

Developing the Risk-based Internal Audit Plan

Understanding the Organization

Identifying Objectives, Strategies, and Structure

Understanding the organization’s risk management processes requires identifying how the roles

and responsibilities of risk management and governance are coordinated. Typically, this

coordination involves:

The implementation of systems of control by operational and line management.

The provision of assurance that systems of risk management and control have been designed

effectively and are operating as designed. Risk management, compliance, quality control, and

similar functions provide such assurance.

The provision of independent assurance and advice over governance, risk management, and

control processes by the internal audit activity.

Communicate for Approval

Finalize Plan

Propose and Solicit Feedback

Draft Plan

Estimate Resources

Coordinate with Other Providers

Identify, Assess, Prioritize Risks

Understand Organization

Assess Risks Continuously

Respond to Changes

(Update Plan)

Implement Plan (Perform Engagements)

Figure 1: Internal Audit Plan Development Cycle

www.theiia.org

7

Developing the Risk-based Internal Audit Plan

Reviewing Key Documents

Before initiating the risk assessment, the CAE may review key organizational documents, such as

the organization chart and the strategic plan. The CAE may review these documents to gain insight

into the organization’s business processes and potential risks and control points. If management

has implemented automated tools for continuous risk monitoring, then internal auditors may

gather information from the risk reports generated automatically. Supplemental information may

be drawn from assessments and reports previously produced by internal and external auditors.

Similar documents for individually auditable units may detail operational processes and the service

functions that support them. Figure 2 lists examples of the information and documents that

internal auditors may gather.

Figure 2: Document Sources for Information Gathering

Which control and assurance roles are operating

in the organization (i.e., first and second lines)?

What are the responsibilities of each?

Has the organization implemented an

enterprisewide risk management (ERM)

framework?

Organizational chart.

Minutes from meetings with senior management,

second line management, and risk committees.

What are the organization’s main objectives,

strategies, and initiatives?

Are any major initiatives and change projects

proposed in the upcoming period?

Organization’s strategic plan.

Strategic plans for critical individual areas and major

initiatives.

Minutes of meetings between senior management

and the board.

What are the organization’s key business

processes?

What are the potential risks and controls in each

process?

Are the strategies, objectives, and plans realistic?

Have all relevant risks been captured?

Annual reports and public/regulatory filings.

Organizationwide risk register (also known as risk

universe).

1

Management’s risk registers (also known as risk

inventories) and risk assessments, including risk and

control self-assessments conducted by the leaders of

each business area (operational risk assessments).

Results of automated risk monitoring, if implemented.

Previous assessments and reports from various

assurance providers (second line functions, internal

and external auditors).

Detailed operational documentation (e.g., process

maps).

Annual reports and public/regulatory filings.

1

. Rick A. Wright, Jr., The Internal Auditor’s Guide to Risk Assessment, 2nd ed. (Lake Mary, FL: Internal Audit

Foundation, 2018), 51.

Information to Be Gathered

Potential Source Documents

www.theiia.org

8

Developing the Risk-based Internal Audit Plan

Consulting with Key Stakeholders

The CAE must consult with key stakeholders to

fulfill the requirements of the standards related

to Standard 2010 – Planning. Ongoing

communication is vital to enable nimble

adjustments to changes. Additionally, ongoing

communication helps ensure that senior

management, the board, and the internal audit

activity share a common understanding of the

organization’s risks and assurance priorities.

Meetings with Board and Governance

Committees

The CAE should attend meetings with the board

and key governance committees (e.g., audit

committee, risk committee) and may meet

independently with individual members.

Attending such meetings helps the CAE learn

about the latest developments in the

organization and be alert to potential risks that

could result from the changes.

Meetings with Management

In addition to meeting with the board, the CAE

(or designated internal auditors) should attend

the regular meetings (phone, web, or in-person)

of senior management and/or those who report

directly to senior management (i.e., second line

roles, such as compliance, risk management, and

quality control). The CAE should speak with

individual senior executives independently. In

certain highly regulated industries or sectors, the

CAE may meet with external auditors and/or

regulators also.

To better understand business processes and challenges to accomplishing business priorities,

internal auditors may meet with key members of operational or line management, such as vice

presidents and directors in each business area, as well as employees performing operational tasks.

Informal Communication

Information obtained informally may complete internal audit’s understanding of the organization,

providing realistic details that are not disclosed formally. Relationships are often enhanced when

Consulting with Key Stakeholders

Stakeholders to Consider

Board: audit committee, risk

committee, governance

committees, individual board

members.

Senior management, chief risk

officer.

Second line functions.

Operational/line management.

Human resources.

Marketing.

Employees performing key

operational tasks.

External auditors/regulators, as

indicated (industry-specific).

Methods of Communication

Face-to-face meetings.

Phone/online conferences.

Surveys.

Interviews.

Group brainstorming sessions,

workshops.

Ongoing, informal

communication.

www.theiia.org

9

Developing the Risk-based Internal Audit Plan

internal auditors are assigned to work with specific business lines, functions, locations, and/or legal

entities. Interacting with management and staff throughout the various business units and

functional areas, including departments such as human resources and marketing, helps the internal

audit activity build a comprehensive picture of the organization’s plans and control environment.

Consistently occurring informal interactions build trust, increasing the likelihood staff will

communicate candidly with internal auditors and bring up concerns that might not be mentioned

in formal meetings. Such openness improves the internal audit activity’s ability to evaluate the

control environment. Rotating internal auditors into and out of such assignments balances the

benefits of informal communication against the need to protect internal auditors’ independence

and objectivity (Standard 1130 – Impairment to Independence or Objectivity).

Surveys, Interviews, Brainstorming, Research

Other tools for obtaining input include surveys,

interviews, and group workshops (e.g.,

brainstorming sessions and focus groups). These

tools are especially useful for identifying

emerging risks and fraud risks.

The CAE and members of the internal audit

activity also may increase their awareness of

potentially emerging risks by researching industry

news, trends, and regulatory changes; networking

with other professionals; and pursuing relevant

continuing education.

Questions to consider include:

How do the top 10 objectives of the

organization relate to key departmental

objectives?

Which strategies are used to achieve those

objectives?

Which risks, if they were to occur, could

interfere with the organization’s ability to

achieve those objectives?

Sources of Emerging Risk

Information

Changes in management

priorities, business processes,

technology (IT), and operations.

Ethics/whistleblower system for

fraud risks.

Geopolitical developments.

Legal and regulatory changes.

Requests from senior

management and the board.

New projects and change

programs.

Prior risk assessments from

management and internal audit

activity (including fraud, IT, and

financial controls).

www.theiia.org

10

Developing the Risk-based Internal Audit Plan

Creating or Revising the Audit Universe

Once the major strategies and objectives have

been identified, the CAE may want to create or

review the audit universe, which is a list or catalog

of all potentially auditable units within an

organization. Auditable units may be any “topic,

subject, project, department, process, entity,

function, or other area that, due to the presence

of risk, may justify an audit engagement.”

An audit universe simplifies the identification and

assessment of risks throughout the organization.

It is a step toward discovering which auditable

units have levels of risk that warrant further

review in dedicated internal audit engagements.

Appendix C offers an example of a worksheet used

to link organizational objectives and strategic

initiatives to categories in the audit universe.

If no audit universe exists, internal auditors start

with their understanding of how the organization

views and categorizes its activities, risks, and

controls, and how it obtains assurance over its risk

management and control processes. This includes

considering any frameworks used by the

organization. Using the structure that most

closely aligns with management’s approach will

maximize synergy between the internal audit

activity and other internal providers of assurance

and consulting services, especially if the

organization has implemented an enterprisewide

risk management (ERM) process. A well-organized

audit universe enhances the likelihood that

internal audit’s risk assessment and audit plan are

useful and valuable to the organization.

Ensuring the audit universe will capture all risks is

challenging because some risks exist in the

interface between organizational units or

between the organization and the external

environment. Looking at the audit universe by business processes often helps reveal such risks. The

sidebar “Ensuring Audit Universe Completeness” lists sources of risk information CAEs should

consider.

Ensuring Audit Universe

Completeness

To ensure completeness of the audit

universe, the CAE should consider

the following sources of risk

information:

Organization’s strategy and

chain of value creation.

All major areas, units,

departments, and projects and

their strategies, objectives, and

processes (at high level, from the

organizational chart, legal,

and/or ERM framework).

Third-party vendors (from legal,

procurement, or contract

management functions).

Processes and subprocesses of

all major functions (from process

mapping activities such as those

required by ISO).

Major IT applications and

information systems assets,

including hardware, software,

and the information they contain

(from IT management).

Regulatory and legal compliance

requirements that apply to the

organization.

Nonfinancial performance

indicators (e.g., environmental,

health and safety, social,

governance).

www.theiia.org

11

Developing the Risk-based Internal Audit Plan

The CAE should consult with senior management to ensure the universe accurately reflects the

organization’s business model. Once an audit universe has been constructed, it may be carried

forward for future use. However, the universe should be updated frequently to incorporate internal

and external business changes, which may introduce new risks at any time. The audit universe helps

organize the auditable areas for a comprehensive assessment of risks and of assurance coverage.

Internal Audit’s Risk Assessment

Understanding the Significance of Independent Assessment

This organizationwide risk assessment enables the CAE to focus on those risks that rate among the

most significant and to identify manageable, timely, and value-adding engagements that reflect the

organization’s priorities. This typically results in a plan that addresses around 15 auditable units on

average.

Organizations that have implemented ERM may have created a comprehensive risk register (also

known as a risk inventory or risk universe). Internal auditors may use management’s information

as one input into internal audit’s organizationwide risk assessment. However, in alignment with the

Code of Ethics principle of objectivity and Standard 1100 – Independence and Objectivity, internal

auditors should do their own work to validate that all key risks have been documented and that

the relative significance of risks is reflected accurately.

Understanding Business Objectives, Strategies, and Risks

Risks Related to Business Objectives and

Strategies

To identify critical, or key, risks, the internal audit

activity should identify and understand not just

high-level organizational objectives and

strategies, but also specific business objectives

and the strategies used to achieve them. Some

organizations may categorize business objectives

as strategic, functional, or process-level.

2

Others

may use the categories of objectives identified in

The Committee of Sponsoring Organizations

(COSO) Internal Control—Integrated Framework:

operations, reporting, and compliance.

2

. Wright, The Internal Auditor’s Guide, 60.

Leveraging Opportunity

Contemporary risk management and

governance frameworks emphasize

the importance of leveraging

opportunity to ensure innovation,

growth, and financial viability.

COSO’s ERM framework defines

opportunity as an “action or

potential action that creates or alters

goals or approaches for creating,

preserving, and realizing value.”

www.theiia.org

12

Developing the Risk-based Internal Audit Plan

Risks Include Opportunities

Internal auditors should consider the multifaceted nature of risks when deciding how to identify

and assess them. Because each organization has its own strategies and business objectives, no

single risk checklist exists for every organization; risk inventories vary by organization and change

over time.

Furthermore, internal auditors should consider that “risks represent the barriers to successfully

achieving … objectives as well as the opportunities that may help achieve those objectives.”

3

Indeed, “risks may relate to preventing bad things from happening (risk mitigation) or failing to

ensure good things happen (that is, exploiting or pursuing opportunities).”

Documenting Risks

Risk Categories

Each business unit or function in the organization may have a different way of viewing and

measuring business objectives, processes, and risks. Creating risk categories introduces reliability

and consistency throughout an organization when identifying, communicating about, and analyzing

risks and risk management processes.

Specific frameworks, approaches, and industries may recommend or require the use of certain risk

categories. If the organization uses a risk management framework, the internal audit activity should

align its categories to those of the framework. If no framework or risk categories exist, internal

auditors can brainstorm with management about risks relevant to the organization by starting with

a taxonomy of risk categories common to most organizations, such as strategic, operational,

compliance, and financial risks.

4

Internal, External, and Strategic Risks

Within each broad category, internal auditors consider internal and external sources of risk, which

generates an extensive list. Internal auditors will assess those risks to narrow the list and prioritize

those that should be included in internal audit planning. Strategic risks, if not managed properly,

have the greatest potential to affect the organization’s ability to achieve its goals.

5

IT Risks

A comprehensive internal audit plan includes IT, which means IT risks must be included in the

overall risk assessment. IT risks may be sorted into subcategories, including infrastructure,

operations, and applications, and are not always tied to a single specific business process. Virtually

every business activity relies on technology to some extent. Technology supports business

processes and is often integral to controlling processes. With the increasing automation of internal

3

. Urton L. Anderson et al. Internal Auditing: Assurance and Advisory Services, 4th ed. (Lake Mary, FL: Internal Audit

Foundation, 2017), 4-3.

4

. Wright, The Internal Auditor’s Guide, 13.

5

. Wright, The Internal Auditor’s Guide, 21.

www.theiia.org

13

Developing the Risk-based Internal Audit Plan

control processes, deficiencies in supporting technologies may affect the organization’s operations

and business objectives significantly.

According to Standard 2110.A2, the internal audit activity must assess whether the information

technology governance — that is its leadership, organizational structures, and processes — support

the organization’s strategies and objectives. Understanding the IT strategic plan should help

internal auditors identify how IT supports the organization to implement its strategies and achieve

its objectives.

The internal audit activity should evaluate the flexibility of the IT strategy — such as its ability to

support the future growth of the organization — and the responsiveness of IT risk management

and control processes to prevent, detect, and respond to cybersecurity threats.

Environmental, Social, and Governance Risks

Investors, consumers, and the public have come to expect organizations to measure and report on

their environmental, social, and governance (ESG) efforts. As part of their investment decision-

making, investors increasingly seek out nonregulatory disclosures on ESG issues; whether in

standalone sustainability reports, public statements on managing nonfinancial risks in financial

filings, or statements directly to other stakeholders (ratings agencies). Nonfinancial reporting may

affect an organization’s reputation with investors, business partners, and prospective employees.

Environmental requirements and compliance risks apply to the supply chain, products, and

services. Environmental fraud, such as cheating on emissions standards, is receiving not just

regulatory attention but also greater public scrutiny. Social risks involve the impact an organization

has on employees, customers, suppliers, and communities. Maintaining positive relationships with

these stakeholders sustains public trust in the organization. Governance risks are related to

strategies, policies, and oversight regarding sustainability, board structure and composition,

executive compensation, political lobbying, bribery, corruption, and fraud.

Internal auditors should participate in their organization’s ESG dialogue and understand their

organization’s ESG efforts, particularly how those efforts align with stakeholder expectations. In

organizations that lack ESG criteria and reporting, the internal audit activity has an opportunity to

help the organization increase its ESG awareness. Effective ESG criteria and metrics combined with

a process to monitor and verify the organization’s ESG data comprise a key control process over

ESG reporting. Global organizations including the United Nations, the Organisation for Economic

Co-operation and Development, and the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board provide

measurable ESG criteria and detailed information about ESG risks, opportunities, and reporting.

Third-party Risks

Some organizational structures, processes, and applications may exist, at least in part, in a

virtualized environment and/or with third-party service providers. The internal audit activity’s

review should consider the risks associated with third-party service providers upon which the

organization relies (e.g., cloud storage services and data management systems). The IIA’s Practice

www.theiia.org

14

Developing the Risk-based Internal Audit Plan

Guide “Auditing Third-party Risk Management” provides helpful information about assessing

third-party risks.

Fraud Risks

The internal audit activity is responsible for assessing the organization’s risk management

processes and their effectiveness, including those related to fraud risks (2120.A2). Because new

fraud risks can arise at any time, internal auditors also must assess fraud risks when they plan each

assurance engagement (Standards 2210.A1 and 2210.A2). Brainstorming with a variety of

stakeholders in the organization is a vital part of assessing fraud risks because fraudulent activities

involve circumventing the existing controls. Many CAEs perform a dedicated, stand-alone fraud risk

assessment. Whatever information is discovered through any of these processes should be

incorporated into the comprehensive risk assessment and internal audit plan. The IIA’s Practice

Guide “Engagement Planning: Assessing Fraud Risks” offers a systematic approach to assessing

fraud risks.

Risk Assessment Approaches

Some common methods for identifying, documenting, and assessing risks are the “specific-risk

approach,” “risk-by-process approach,” and “risk factor approach.” CAEs may customize their

approach to the organizationwide risk assessment, and many use a hybrid (i.e., a combination of

approaches). The feedback of senior management and the board (and relevant committees of

each

6

) should be taken into account when selecting an approach and criteria for the comprehensive

risk assessment.

Risk assessments typically include both quantitative and qualitative methodologies. An abundant

selection of software is available to help the internal audit activity perform risk assessments that

result in both quantitative and qualitative data.

A specific-risk approach may be considered bottom-up because it involves identifying risks

associated with each specific auditable unit in the audit universe. Risks are identified in relation to

business objectives, typically by meeting with relevant management specifically for this purpose.

Based on the combined criteria (e.g., impact, likelihood), composite risk scores are calculated for

individual auditable units. This approach is frequently used for risk assessments related to

individual audit engagements but may become cumbersome when extended to the organizational

level, where the number of auditable units and risks becomes quite large. A simple version of this

approach is shown in Appendix D.

A risk-by-process approach is similar to a specific risk approach. Internal auditors and management

start by considering business processes throughout the organization as the auditable units. Key

risks are mapped to each process. Additionally, internal auditors work to determine which

6

The IPPF’s definition of “board” includes relevant committees or other bodies to which the governing body delegates

certain functions; thus uses of “board” in this guidance should be interpreted as including committees of the board.

www.theiia.org

15

Developing the Risk-based Internal Audit Plan

processes play key roles in achieving objectives and how effectively risks to those processes are

managed. The processes with the highest degree of residual risk are prioritized for inclusion in the

internal audit plan.

7

A risk-factor approach is considered top-down because it looks at high-level conditions that are

common across most auditable units. This approach is commonly used when performing a

comprehensive, organizationwide risk assessment because it provides a macro-level view. Internal

auditors identify the factors common to all auditable units that have an effect on the organization’s

ability to achieve its objectives. Risk factors are not the risks themselves but instead are conditions

likely to be associated with the presence of a risk; that is, conditions that indicate a higher

probability of significant risk consequences.

The potential list of risk factors may become large, complicating the risk assessment process. CAEs

may simplify by grouping the factors into categories, such as strategic, compliance, operational,

and financial. In some organizations, senior management and the board may advise the internal

audit activity regarding the risk factors that they believe are most relevant. Some risk factors may

link to multiple categories. However, categorizing risk factors may be convenient when

summarizing the risk assessment for senior management and the board.

Examples of risk factors and risk factor categories include:

Relative level of activity (e.g., number of transactions).

Materiality (magnitude of revenue or expense).

Liquidity of assets involved.

Impact on brand (public perception, reputation).

Failure to meet goals.

Management competency, performance, turnover.

Known deficiencies (previous unsatisfactory engagement results).

Degree of change in systems, policies, procedures, contracts, relationships.

Susceptibility to fraud.

Complexity of operations.

Degree of third-party reliance.

Strength of internal controls, control environment.

Degree of regulatory involvement, compliance concerns.

Time since last assessment or audit.

8

Appendix E provides an example of risk assessment using the risk-factor approach.

7

. Anderson, Internal Auditing: Assurance and Advisory Services, 120.

8

. Wright, The Internal Auditor’s Guide, 68 and 98.

www.theiia.org

16

Developing the Risk-based Internal Audit Plan

Measuring Risks

Inherent Risk

In their risk assessments, internal auditors should estimate both inherent risk — the risk that exists

if no controls were in place — and residual risk. The distinction is important because management

tends to think primarily in terms of residual risk, but internal auditors need to be able to consider

whether risk mitigation techniques are effectively designed and operating. Internal audit’s risk

assessments start by considering inherent risk, the combination of internal and external risks in

their pure, uncontrolled state.

Risk Management Strategies and Residual Risk

Residual risk, or net risk, is the portion of inherent risk that remains after management executes

its risk management strategies.

9

With the help of management, internal auditors identify the risk

management strategies and control processes and translate them into operational, or measurable,

terms to help determine residual risk. The CAE or assigned internal auditors should document the

reasons for their determination of residual risk. This rationale lends support to internal audit’s view

of risk priorities, which is especially important in cases where internal audit judgement may be in

conflict with a strict interpretation of risk rating results.

Rating the risk associated with each unit allows the CAE to prioritize internal audit coverage of that

unit.

10

Measurement often requires standardizing terminology, definitions, and specifications

throughout the audit universe (e.g., risk ratings, materiality, etc.). This standardization may involve

alignment with the organization’s risk management framework, if one exists.

Impact and Likelihood Ratings

Impact and likelihood are two measures recognized in The IIA’s definition of risk. Additionally, the

CAE may consider or include other measures of impact or severity, such as those recognized in the

COSO ERM Framework (i.e., adaptability, complexity, persistence, recoverability, and velocity). Risk

ratings may be numeric (e.g., scale from 1 to 3 or from 1 to 5) or categorical (e.g., impact ratings

may be insignificant, material, and extreme; and likelihood ratings may be low, moderate, and

high).

No matter which format is chosen, each measure should be defined by specific criteria. For

example, impact criteria may include legal, compliance/regulatory, reputational, operational, and

materiality in financial criteria (value at which the impact on revenue could affect the achievement

of organizational objectives). Criteria to define likelihood include control effectiveness and

complexity of operational processes.

Examples of impact and likelihood scales with criteria appear in Appendix D. Impact and likelihood

ratings are combined to create a comprehensive risk rating that represents the overall significance

of each risk within each auditable unit/area.

9

. Anderson, Internal Auditing, 487.

10

. Wright, The Internal Auditor’s Guide, 85.

www.theiia.org

17

Developing the Risk-based Internal Audit Plan

Risk Factors and Total Risk Score

Risk factors are elements that generally increase the impact or likelihood of risk to the related

auditable unit, and in the risk-factor approach, risk ratings are assigned to the risk factors

themselves, rather than to the level of impact or likelihood. However, the factors may be grouped

by whether they affect either impact or likelihood.

Weighting, total risk score – Some factors are more significant to achieving objectives than others

and therefore may be weighted (numerically). Each auditable unit is rated on each risk factor, and

the risk factor ratings are aggregated to create a single, aggregate risk score for the auditable unit,

called the total risk score. This score provides a basis of comparison for prioritizing, or ranking,

auditable units.

Regulated calculations – In certain industries, regulators may mandate a particular risk framework

with a formal risk-rating template and/or methodology.

11

The CAE may refer to management’s risk

ratings as measured against the framework and then the CAE may opine on whether the internal

audit activity agrees or disagrees with management’s rating of risk.

Risk categories and factors should be reviewed and updated periodically to ensure they are

appropriate for the size and complexity of the organization. Evidence of the review should be

maintained with other internal audit planning records.

Heat Map

Risk assessment results with levels of risk for each auditable unit may be depicted graphically in a

heat map or similar chart to help show the ranking of priorities. Heat maps are especially useful

when certain criteria are weighted more heavily than others and in visual presentations to the

board and senior management.

Validating Risk Assessment with Management

The internal audit activity considers stakeholder input throughout the process of developing the

internal audit plan, and this feedback informs the internal audit activity’s risk assessment. At the

same time, the internal audit activity must remain independent and objective — unbiased by

management — including in its risk assessment. CAEs should meet with senior management to

review internal audit’s assessment, ensure thoroughness and mutual understanding, and discuss

the reasons for any significant differences in risk perceptions or ratings. CAEs may account for

management’s risk awareness level by representing it as a risk factor and adding or subtracting

points from the total risk score to increase or decrease the relative significance of risk in relation

to an auditable unit.

11

. For example, in the United States banking industry, nine risk categories must be considered and rated for each

engagement area or process under review.

www.theiia.org

18

Developing the Risk-based Internal Audit Plan

Additional Planning Considerations

Accommodating Management and Board Requests

Senior management and/or the board may request assurance and consulting services, and the CAE

should accommodate these requests. Consulting/advisory services may be requested in areas or

processes that have not appeared among the top priorities in the risk assessment; often, they are

opportunities for the internal audit activity to provide advice that will lower the likelihood of risk

occurrences in the future. For instance, internal auditors may be asked to determine the root cause

of a failed external audit or to review the implementation of a new process or technology.

Thus, many CAEs reserve a percentage of their audit plan to perform requested consulting

engagements as well as ad hoc engagements that arise between the time of the risk assessment

and that of plan revisions. Investments of internal audit resources in consulting engagements

should be reflected in the internal audit budget and plan.

Engagement Frequency and Timing

Not all auditable areas can be reviewed in every audit cycle, nor should they. Ideally, audit

frequency is based on the risk assessment. CAEs should consider which engagements will most

enhance the organization’s ability to achieve its objectives and which have the potential to add the

most value.

Determining Frequency Based on Risk

In a purely risk-based internal audit plan, CAEs may apply one of two strategies to arrive at the ideal

frequency of planned engagements.

1. The audit plan may be based on a continuous risk assessment without a predefined

frequency for engagements. Given the accelerating rate of change in today’s risk landscape,

many organizations are implementing continuous auditing, which allows them to respond

nimbly and dynamically to changes throughout the year, making periodic changes to the

audit plan as needed. These audit plans are identified as “rolling,” “fluid,” and/or “dynamic.”

2. The audit frequency is based upon the level of residual risk determined in the risk assessment.

For example, auditable units ranked high-risk may be audited at least annually (or once every

12 to 18 months), those rated with a moderate level of risk scheduled may be reviewed every

19 to 24 months, and those rated low-risk might be audited only once every 25 to 36 months

(or not at all).

To ensure the internal audit plan covers all mandatory and risk-based engagements, internal

auditors should consider:

Engagements required by law or regulation.

Mission-critical engagements.

www.theiia.org

19

Developing the Risk-based Internal Audit Plan

The time and resources required for compulsory engagements and risk-based priorities.

Whether all significant risks have sufficient coverage by assurance providers.

The percentage of the plan that should be reserved for special projects, consulting, or ad hoc

requests.

Cyclical Frequency in Highly Regulated Industries

In some industries, such as financial services, organizations are subject to regulations that require

them to establish an audit/risk universe, risk scores, and risk ratings and to maintain a minimum

cycle of auditing. Even if the inherent risk of noncompliance is small, these engagements must be

included in the audit universe to ensure the internal audit activity’s performance with due diligence

and professional competency.

When law, regulation, or industry standards require certain engagements to be conducted

cyclically, the CAE may design multiyear audit plans to document the timing and any specialized or

additional resources that may be needed. In addition to coordinating the information gathered,

internal auditors should work with external auditors to synchronize the timing of engagements to

ensure minimal disruption of the organization’s operations.

Although these cyclical engagements are required, they compete for resources with engagements

that are prioritized by level of risk. To some extent, they may seem to conflict with the concept of

risk-based auditing, especially when the internal audit activity and management have established

processes for managing risks and providing assurance over the required risk areas.

To address this challenge, CAEs may:

Reduce scope of compulsory engagements, touching upon required areas without investing

beyond the minimum requirement.

Extend long-term plan timeline (to seven years, for example) to account for compulsory

engagements, while continuously assessing risk and adjusting short-term plans more

frequently to prioritize engagements linked to significant risks.

Coordinate with and rely upon other assurance providers.

While cyclical engagements comprise one input into the internal audit plan, CAEs must be careful

not to rely heavily on their long-term plans in the face of today’s rapidly changing risk landscape.

When multiyear plans are established, the current year should be planned in some detail, reviewed

at least quarterly, and modified as appropriate.

www.theiia.org

20

Developing the Risk-based Internal Audit Plan

Estimating Resources

The CAE must determine the resources needed to

implement the plan. Resources may include people

(e.g., labor hours and skills), technology (e.g., audit

tools and techniques), timing/schedule (availability

of resources), and funding. The CAE must estimate

the scope of engagements and the skills, time, and

budget that will be needed to perform those

engagements. The CAE may reflect on the nature

and complexity of each engagement, the resources

spent on comparable engagements that were

performed previously, and the date of the most

recent audit of the area or process.

Assessing Skills

Standard 2030 describes “appropriate resources” in

terms of knowledge, skills, and competencies. The

competency of the internal audit activity receives

significant attention in the Standards and is one of

the four principles in The IIA’s Code of Ethics.

As part of internal audit planning, CAEs must know

the internal audit team’s competencies. CAEs may

devise and maintain an inventory of each auditor’s specialized skills and knowledge, along with a

benchmark of skills necessary to fulfill the expectations, needs, and demands of the organization

and the industry. Some highly regulated industries may even provide a list of expected minimum

skills and require a skills’ analysis to be performed regularly.

The established benchmark can then be fine-tuned to identify the specific skills needed to achieve

the internal audit plan. The CAE should align the inventory of skills present among the internal audit

staff with those needed to fulfill expectations and perform the engagements in the plan.

Coordinating with Other Providers of Assurance and Consulting Services

The internal audit activity adds the most value by providing assurance and consulting services

where the highest residual risk exists. However, in mature and highly regulated organizations, some

high-risk areas may be controlled effectively by the first line and may have sufficient assurance

coverage provided by the second line, such as risk management and compliance functions, as well

as additional coverage by external auditors. The organization’s chief information officer or chief

information security officer may assess IT risks, and the internal audit activity may corroborate the

results.

Requirements for Internal Audit

Resources

Standard 2030 – Resource

Management

The chief audit executive must

ensure that internal audit

resources are appropriate,

sufficient, and effectively deployed

to achieve the approved plan.

Interpretation:

Appropriate refers to the mix of

knowledge, skills, and other

competencies needed to perform

the plan. Sufficient refers to the

quantity of resources needed to

accomplish the plan. Resources are

effectively deployed when they are

used in a way that optimizes the

achievement of the approved plan.

www.theiia.org

21

Developing the Risk-based Internal Audit Plan

To make the best use of the valuable resources, the CAE should coordinate activities, share

information, and consider relying upon the work of other internal and external assurance and

consulting service providers (Standard 2050 – Coordination and Reliance). Relying upon the work

of other providers instead of repeating the coverage minimizes the duplication of work and

maximizes the efficiency with which assurance is provided.

Assurance Maps

An assurance map documents the coordination

of assurance coverage. It lists all significant risk

categories and links them with relevant sources

of assurance. Based on the compiled information,

the degree, or level, of assurance coverage

provided can be rated as adequate or inadequate,

and gaps and duplications become clear.

Creating an assurance map involves the various

assurance providers collaborating from a holistic, organizationwide perspective. Identifying where

the work of other providers overlaps with internal audit’s coverage helps justify the CAE’s decision

about which engagements to include and exclude from the internal audit plan. The map also

provides clear evidence of gaps in assurance, where additional resources may be needed.

Meeting Need for Additional Skills

If the internal audit activity lacks the knowledge or skills needed to complete a particular assurance

engagement, the CAE may call upon an expert or specialist from within the organization to provide

technical expertise and simultaneously instill internal audit staff with new knowledge.

Other options include cosourcing, where experts from outside the organization perform specialized

work under the supervision of an experienced internal auditor, and outsourcing, where the work

is performed entirely by an outside firm. The CAE should account for these staffing arrangements

in the plan’s budget.

Calculating Hours in Plan

To calculate “available” internal audit resource hours, the CAE calculates the total number of hours

each internal audit team member is able to contribute to the completion of the audit plan in a

given period (typically one year). Total available hours take into consideration the results of the

skills assessment, the use of external resources and support staff, and the tasks that do not

contribute to plan completion.

Learn About Assurance Maps

The IIA’s Practice Guide

“Coordination and Reliance:

Developing an Assurance Map”

provides detailed, recommended

guidance with examples for creating

and using assurance maps.

www.theiia.org

22

Developing the Risk-based Internal Audit Plan

As an example, the CAE may start with the assumption that a full-time employee represents the

equivalent of 2,080 total hours (i.e., 40 hours per week, 52 weeks per year).

12

Then, the CAE may

subtract the following to determine the available hours that remain:

Subtract nonaudit, or nonproductive time, based on activities that do not contribute to the

completion of engagements and fulfillment of the audit plan.

o Paid time off (holidays, vacation, paid sick leave).

o Training and personal development.

o Meetings (within the internal audit team and with management and the board).

o Internal audit activity’s quality assurance and improvement initiatives.

o Reduced utilization rates for anticipated new hires in the given year.

o Time spent consulting with subject matter experts to develop audit

strategies/frameworks.

o Unanticipated turnover during the year (i.e., “vacancy factor,” typically used for a

large staff).

o Reserve for nonaudit tasks that have not yet been assigned.

Subtract time spent assisting other assurance providers, e.g., external audit, if applicable.

Subtract CAE’s hours reserved for supervising and related activities (e.g., estimate at 80

percent).

Subtract productive hours to be spent on ongoing requirements, monitoring, data analysis,

follow-up on engagements already performed, and a reserve for ad hoc requests. Note: some

CAEs include ongoing monitoring/auditing as part of the available, productive hours.

The remainder is available hours (audit time or chargeable time) to be spent on performing

engagements (including risk assessments, analysis and evaluation, documentation, and

reporting) to fulfill the risk-based internal audit plan.

Drafting the Internal Audit Plan

All the preparatory work culminates in a draft version of the internal audit plan to be presented,

discussed, revised, and finalized for approval. The proposed internal audit plan may include the

following sections:

Executive summary – This short overview of key points typically includes a one-page summary of

the most significant risks, the planned engagements and basic schedule, and the staffing plan.

Policies and processes – This overview gives the board an understanding of the due diligence and

thoroughness of internal audit’s planning policies and approach, with basic descriptions of the

processes used to establish the audit universe, perform the risk assessment, coordinate assurance

12

. CAEs should adjust assumptions to reflect the actual circumstances of their internal audit staff and organization.

www.theiia.org

23

Developing the Risk-based Internal Audit Plan

coverage, and staff the plan. Any changes in policies and procedures may be highlighted for

discussion.

Risk assessment summary – A description of the risk assessment process and results enhances the

board’s understanding of internal audit’s

priorities. Information may include:

Organizational strategy, key areas of focus,

key risks, and associated assurance

strategies in the audit plan.

Summary of risks.

Analyses (or summary) of inherent and/or

residual risk levels of auditable units.

Risk scores/ratings for auditable units.

Heat map for entire audit universe indicating

priorities, inclusions, and exclusions.

Overview of engagements in plan –

A list of proposed audit engagements (and

specification regarding whether the

engagements are assurance or consulting in

nature).

Tentative scopes and objectives of

engagements.

Tentative timing and duration (timeline showing the quarter during which the engagement

will be performed and how long it will take to complete).

Assurance coverage and exclusions – This section may include an assurance map, summary, or

other tool to communicate assurance coverage over significant risk areas. Exclusions acknowledge

auditable units or risk areas that are not addressed, and if any high-risk areas are not covered (e.g.,

due to resource limitations), then this section may include recommendations to the board for

obtaining assurance, such as via cosourcing or outsourcing.

Rationale for inclusions and exclusions – This explanation is important, especially if risk ratings or

frequency determinations are overridden. Reasons may include change in risk rating, length of time

since last audit, change in management, and more.

Resource plan – This section identifies the type and quantity of resources that will be needed to

execute the plan. The description may include the number of staff required to complete the audit

plan (capacity), the number of support staff needed, a summary of the results of the skills

assessment, and a plan of action to address skill gaps.

IPPF Requirements for Plan

Standard 2010.A2 – The chief audit

executive must identify and consider

the expectations of senior

management, the board, and other

stakeholders for internal audit

opinions and other conclusions.

Standard 2010.C1 – The chief audit

executive should consider accepting

proposed consulting engagements

based on the engagement’s potential

to improve management of risks,

add value, and improve the

organization’s operations. Accepted

engagements must be included in

the plan.

www.theiia.org

24

Developing the Risk-based Internal Audit Plan

Financial budget requirements – The plan includes a financial budget to cover payroll of internal

audit staff, as well as the cost of cosourced and/or outsourced services, tools (i.e., technology),

training, and other expenses.

IPPF and relevant standards – References to conformance with relevant IPPF standards and

guidance supports a discussion with senior management and the board about the importance of

internal audit’s risk-based plan as well as other aspects of planning (e.g., communication,

coordination, and reliance).

Approval sign-off area – Senior management and the board must approve the plan.

Subsections, or subplans – Within the overall plan, the risks from all auditable areas may be

consolidated into risk categories, with assurance coverage relevant to each key risk area specified.

Operational.

Financial.

Compliance.

IT/cybersecurity.

Culture.

Consulting services (e.g., strategic initiatives; preliminary evaluation of new system).

Requested special assignments (e.g., investigations).

Follow-up (i.e., tracking implementation of recommendations).

Appendix F shows an example of an executive summary of a three-year internal audit plan, in which

the second and third years are subject to change based on the results of risk assessments.

Proposing the Plan and Soliciting Feedback

Once a tentative risk-based plan is developed, the CAE or internal audit manager typically discusses

the plan with senior management before formalizing it for presentation to the audit committee

and/or full board. The CAE typically implements a standard process for this mutual review and may

meet with each senior manager individually. The CAE may also consult with specific committees, such

as those responsible for risk management, compliance, ethics, and others. Meetings may also be

scheduled with individual process owners to discuss the initial scope and timing of engagements.

In discussions, the CAE should communicate the results of the risk assessment, how the significant

risks could affect the organization’s objectives, and how the results help determine the plan of

audit engagements. The CAE also should describe the assignment of resources, such as the areas

over which the internal audit activity will provide assurance and those for which it will rely upon

other assurance providers. During the meetings, the CAE can address any concerns of senior

management. The plan may be altered based on discussions of risk appetite and the scope and/or

timing of assurance coverage (based on coordination with other providers). Together, the CAE and

senior management reflect on questions such as:

www.theiia.org

25

Developing the Risk-based Internal Audit Plan

Have all risks and auditable units been considered exhaustively?

Are there any upcoming changes that we have not considered methodically – e.g.,

acquisitions, mergers, system upgrades, third-party suppliers, or software implementation?

How do the engagements in the plan link to the organization’s objectives and top risks?

How do the engagements add value for senior management and the organization?

Does the coordination of assurance coverage and the schedule/timing of engagements make

sense?

If any requests not been honored, why not?

Assurance Coverage Limitations Related to Budget

When communicating the internal audit activity’s plans and resource requirements, the CAE should

express the relationship between the risks facing the organization and the budget available for

assurance coverage. The CAE should bring attention to high-risk areas that will not have sufficient

assurance coverage and should be prepared to request additional resources if needed.

Communicating to Finalize the Plan

Presentation to Audit Committee

The CAE evaluates senior management feedback and incorporates relevant information to ensure

that the plan appropriately reflects the organization’s priorities and that management supports the

plan’s implementation. The revised plan is presented to the audit committee for additional review.

The audit committee may suggest adjustments to the plan based on its view of the organization’s

risk appetite. The meeting also gives the CAE an opportunity to explain the budget and its

relationship to assurance coverage, noting any significant gaps in coverage.

Presentation to Full Board

To communicate to the board, the CAE typically creates a presentation that summarizes the

engagements in the plan, explains the risk assessment behind the selections, and expresses the

value of the independent and objective assurance and advice provided by the internal audit

activity. The audit committee chairperson may present the information summary to the full board

for final approval. Once senior management and the board have approved the plan formally, all

affected business areas in the organization typically receive a copy.

www.theiia.org

26

Developing the Risk-based Internal Audit Plan

Ongoing Communication

In some organizations, the CAE communicates

quarterly, through a formal report. The timing of

presentations to the senior management and the

board (audit committee) may affect how both

stakeholder groups perceive the internal audit

activity. Too much information provided all at one

time (e.g., the end of the quarter) could reduce

stakeholder receptivity to the internal audit

activity. Internal auditors should take care to

communicate regularly with senior management

and prepare any changes to the internal audit

plan with sufficient advanced notice to allow

opportunities for discussion.

Communicating Proposed Changes

If the internal audit plan and/or resource

requirements change significantly, the CAE must

communicate those changes to senior

management and the board and obtain their

approval, according to Standard 2020 –

Communication and Approval. Even when

adjustments to the plan are minor, they may

provide opportunities for the three parties to

discuss their perceptions of risks, to improve the

accuracy of shared information, and to align their

risk management priorities.

Some CAEs or internal audit managers review their internal audit plan monthly. They evaluate

whether any changes to the risk profile warrant replacing scheduled engagements and whether

sufficient resources are available to add new engagements into the plan.

Although communicating these changes quarterly is not required, many CAEs choose this schedule

for consistency. The dialogue may involve asking for resources. Internal auditors contemplate

questions such as, “Would a change to the audit plan be a unique event, or would it require a long-

term adjustment of the budget?” To accommodate new engagements within the existing budget,

the internal audit activity may have to eliminate something from the plan. The CAE or internal audit

manager may make a business case for the desired changes, or may ask senior management and

the board which project they are willing to cancel to free up the resources for the change.

Reasons to Adjust Audit Plan

Organizational changes that may

change the organization’s risk profile

include (but are not limited to):

Acquisition or sale of a business

unit or asset.

Change in board membership,

organizational ownership, or

leadership.

Changes to laws, regulations, or

industry standards, which may

introduce new compliance risks.

Changes to strategic initiatives,

including the pursuit of new

opportunities.

Discovery of unforeseen risk

indicators during internal or

external audit engagements.

External changes, such as

political or environmental

developments.

Implementation of new systems.

www.theiia.org

27

Developing the Risk-based Internal Audit Plan

Appendix A. Relevant IIA Standards and Guidance

The following IIA resources were referenced throughout this practice guide. For more information

about applying the International Standards for the Professional Practice of Internal Auditing, please

refer to The IIA’s Implementation Guides.

Code of Ethics

Principle 1: Integrity

Principle 2: Objectivity

Principle 3: Confidentiality

Principle 4: Competency

Standards

Standard 1000 – Purpose, Authority, and Responsibility

Standard 1100 – Independence and Objectivity

Standard 1130 – Impairment to Independence or Objectivity

Standard 2010 – Planning

Standard 2020 – Communication and Approval

Standard 2030 – Resource Management

Standard 2040 – Policies and Procedures

Standard 2050 – Coordination and Reliance

Standard 2060 – Reporting to Senior Management and the Board

Standard 2110 – Governance

Standard 2330 – Documenting Information

Standard 2440 – Disseminating Results

Guidance

Global Technology Audit Guide (GTAG), “Auditing IT Governance,” 2018

Practice Guide “Assessing the Risk Management Process,” 2019

Practice Guide “Coordination and Reliance: Developing an Assurance Map,” 2018

Practice Guide “Demonstrating the Core Principles for the Professional Practice of Internal Auditing,” 2019

Practice Guide “Engagement Planning: Establishing Objectives and Scope,” 2017

Practice Guide “Engagement Planning: Assessing Fraud Risk,” 2017

Practice Guide “Internal Audit and the Second Line of Defense,” 2016

www.theiia.org

28

Developing the Risk-based Internal Audit Plan

Appendix B. Glossary

Definitions of terms marked with an asterisk are taken from the “Glossary” of The IIA’s International

Professional Practices Framework

®

, 2017 edition. Other sources are identified in footnotes.

auditable unit – Any particular topic, subject, project, department, process, entity, function, or

other area that, due to the presence of risk, may justify an audit engagement.

13

board* – The highest level governing body (e.g., a board of directors, a supervisory board, or a

board of governors or trustees) charged with the responsibility to direct and/or oversee the

organization’s activities and hold senior management accountable. Although governance

arrangements vary among jurisdictions and sectors, typically the board includes members

who are not part of management. If a board does not exist, the word “board” in the

Standards refers to a group or person charged with governance of the organization.

Furthermore, “board” in the Standards may refer to a committee or another body to which

the governing body has delegated certain functions (e.g., an audit committee).

chief audit executive* – Describes the role of a person in a senior position responsible for

effectively managing the internal audit activity in accordance with the internal audit charter

and the mandatory elements of the International Professional Practices Framework. The

chief audit executive or others reporting to the chief audit executive will have appropriate

professional certifications and qualifications. The specific job title and/or responsibilities of

the chief audit executive may vary across organizations.

compliance* – Adherence to policies, plans, procedures, laws, regulations, contracts, or other

requirements.

consulting services* – Advisory and related client service activities, the nature and scope of which

are agreed with the client, are intended to add value and improve an organization’s

governance, risk management, and control processes without the internal auditor assuming

management responsibility. Examples include counsel, advice, facilitation, and training.

control processes* – The policies, procedures (both manual and automated), and activities that

are part of a control framework, designed and operated to ensure that risks are contained