Demonstrating the importance of intangible ecosystem services from

peri-urban landscapes

Henrik Vejre

*

, Frank Søndergaard Jensen, Bo Jellesmark Thorsen

Forest & Landscape, University of Copenhagen, Rolighedsvej 23, 1958 Frederiksberg C, Denmark

1. Introduction

The complexity of the provision of services from ecosystems, i.e.

production, regulation, habitats and information services (see, e.g.

de Groot et al., 2002) has been extensively discussed during the past

couple of decades. Contemporary problems in the human–

environment systems, e.g. climate change, loss of wildlife habitats

and water shortages, call for analytical tools which can provide

insight into the concrete value of ecosystems. There is a growing

consensus that we need to assess the value of non-marketable goods

and services from ecosystems to balance the classic values from

production-related activities. Environmental valuation (see, e.g.

Freeman, 2003 for a theoretical introduction) has emerged as an

independent discipline, aiming at valuing and balancing these

various goods and services when planning the exploitation of

natural resources. A strong challenge for this thinking is its practical

applications: qualification and quantification of single and jointly

produced ecosystem services as input to management and planning

(Turner et al., 2003). Experiences in rating and valuing the values of

‘‘hard’’ ecosystem services such as flood control, CO

2

-sequestration,

denitrification, filter effects and to some extent recreation have been

gained in recent decades. Attempts to aggregate these values even at

the highest level have been made (Costanza et al., 1997), but there is

still considerable uncertainty about how to practically assess and

value the even more intangible or ‘‘soft’’ ecosystem services, such as

aesthetics, the mere presence of open space, experience and cultural

heritage (e.g. Price, 2008). While valuation methods for non-

marketed ecosystem services are of importance, they face at least

three key challenges for landscape management and planning to

internalise the values of the more intangible ecosystem services.

Ecological Complexity 7 (2010) 338–348

ARTICLE INFO

Article history:

Received 5 May 2009

Received in revised form 18 September 2009

Accepted 21 September 2009

Available online 24 October 2009

Keywords:

Landscape values

Cost of provision

Ecosystem services

Landscape functions

Recreation

Aesthetics

Peri-urban landscape

ABSTRACT

Among ecosystem services, the various categories of intangible services linked to human perception,

such as aesthetics, recreational values and cultural heritage, must be rated alongside ta ngible services

linked to physical processes, such as wildlife habitats, clean water and air, and filter- and buffer effects.

This is a pre-requisite for a sustainable development with a balance between ecological, social and

economic values. We analyse ecosystem services in areas of the urban fringe of Copenhagen, where the

services provided are mainly related to hum an perception. We employ relatively simple methods in

selected landscapes to qualify or quantify the aesthetics and recreational value, and the scale of the

welfare economic value of these ecosystem services. In the first case area, the Danish state acquired 50

villas covering more than 50 ha in order to recreate open vistas and gain access for the public to the

seaside. In the second case area, peri-urban open landscapes were protected by conservation orders, to

maintain and enhance the ben efits of green space for the growing urban population. We assess the value

– in a broad sense – of these ecosystem services using three practical methods: a landscape evaluation in

terms of services and qualities, an assessment of actual recreational use, and finally an asse ssment of the

costs – in terms of residential development values lost – of securing the provision of aesthetic qua lities

and recreational opportunities.

Searching the original planning documents we uncovered the original motivation for the land

evaluation and decision. The arguments behind the designation and protection of the areas were

primarily aesthetic and potentials for recreational use. The two areas receive annually 2–2.5 million and

400.000 visits respectively, proving their strong recreational value. The value of the demolished houses

in the first case area exceeds 115 million

s

, and the value of the lost development opportunities in the

second case area exceeds 280 million

s

.

By combination the three methods, we substantiated that the intangible services may dominate the

tangible in cases like these, stressing the need for planners to assess the role and value hereof.

ß 2009 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

* Corresponding author.

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Ecological Complexity

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ecocom

1476-945X/$ – see front matter ß 2009 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.ecocom.2009.09.005

Firstly, undertaking primary environmental valuation studies is

time consuming and expensive. Secondly, the stated preference

methods in particular are difficult to communicate and potentially

flawed by, e.g. hypothetical bias or other methodological uncer-

tainties (e.g. Kahnemann and Knetsch, 1992). This makes it hard to

obtain widespread application and in particular acceptance of the

approaches. Thirdly, these methods can only capture values, use- or

non-use values that people perceive as related to the ecosystem in

question. Several, even quite ‘‘hard’’ value components may thus

escape quantification (Costanza, 2008).

Multiple studies have addressed the challenges of classifying

ecosystem services, or the synonymous ecosystem or landscape

functions. Classification systems and nomenclatures of ecosystem

services (ecosystem functions, landscape functions) vary according

to the scientific or strategic point of departure: agriculture (Anon.,

2001), landscape planning and management (Brandt and Vejre,

2003a) or conservation of ecosystems (Farber et al., 2002; de Groot

et al., 2002). There is a general consensus of distinguishing

between marketable goods and other goods or services, the latter

being a very heterogeneous group. Distinction between material

and non-material services or functions has been proposed by

several authors (de Groot et al., 2002; Costanza et al., 1997). Brandt

and Vejre (2003b) suggested a further distinction between the

intangible or transcending functions, separating perceived func-

tions or services from statutory functions or services, i.e. the

articulated visions for the development or status of areas as it is

encountered in planning documents. While the many contribu-

tions represent some degree of consensus on nomenclature and

definitions, severe difficulties persist in classifying and valuing the

various services in a consistent and quantitative manner.

Environmental valuation methods may capture parts of the

value aspects of the intangible functions or services, but unresolved

challenges remain. One challenge is the task of describing the exact

spatial extent of the particular service, addressing questions such as

‘‘where is the landscape beautiful, and where is it not?’’, ‘‘where are

the recreational qualities and where are they not?’’ i.e. drawing

exact boundaries in landscapes where such boundaries are only

vaguely defined. Nevertheless, in a world with rapidly developing

paradigms for assessing ‘‘hard’’ services, there is also a strong need

to develop and highlight the soft values by valuing them with the

same priority and rigor as the hard ones.

In the western world, there is a long tradition of valuing

landscapes through the instruments of landscape protection by

designation (reviewed by Hamin, 2002). A multitude of mostly

qualitative methods have been employed in the identification and

delineation of landscapes of high cultural and aesthetic quality in

most European countries, leading to the declaration of protected

landscapes of various kinds. However, there is often limited

documentation of methodology and exact criteria for these

delineations; rather, they rest on subjective descriptions and

qualitative assessments.

The aim of this study is to identify and value a sample of soft

landscape services: the landscape aesthetics and the recreational

use, and further to assess the monetary value of open landscapes

reserved for these two services. We aim at identifying the exact

criteria used for the identification and delineation of protected

areas where intangible services are the primary outputs, as well as

assessing the extent of recreational use of these areas, and

establish an economic valuation of the same areas.

2. Methods of assessment

2.1. Case study approach

The point of departure of this paper is a number of landscapes,

an approach which bears resemblance to the case study approach

known from social sciences (e.g. Yin, 2003). The social science

approach aims at characterising the real world, which may be

highly complex, and cannot easily be subdued to controlled

experiments. By working with cases we attempt to illustrate the

complexity of assessing the intangible ecosystem services

provided by real-world peri-urban landscapes. As such we employ

explorative, descriptive and explanatory approaches in the study.

We choose areas in the peri-urban landscapes north of

Copenhagen (Fig. 1) known for their high aesthetic and recrea-

tional qualities, representing a long conservation tradition. The

areas provide several ecosystem services, including, e.g. produc-

tion, habitat protection and drinking water supply. However, the

areas are not unique in terms of any of these specific functions or

services, but they are unique in their provision of intangible

landscape values in the Greater Copenhagen area, making them

particularly suitable for studies of intangible services.

The advantage of a case study approach is that we leave

environmental valuation theory related to ecosystem services and

its more abstract and generic applications somewhat behind, and

we limit ourselves to the challenge of describing the complexity of

the type of ecosystem service to that relevant to the case study

areas. This of course limits the generality of observations made, but

it enhances their value for communication with decision-makers.

Further, the access to data is adequate, and the knowledge of the

history of the case areas is comprehensive and detailed.

2.2. Description of case areas

The case areas are located north of Copenhagen, the capital of

Denmark (Fig. 1). The landscape consists of an undulating moraine

plateau with scattered hills and hillocks, dissected by deeply cut

glacial valleys and ravines. Lakes and forests are abundantly

scattered in the landscape, making this part of the urban fringe of

Copenhagen quite attractive. A summary of data regarding the case

areas is given in Table 1.

2.2.1. Springforbi

The Springforbi case area is approximately 50 ha, located at the

eastern-faced coast north of Copenhagen (Fig. 1), and generally

considered the most fashionable high-life urban area of Denmark.

The area possesses high icon value in terms of aesthetics and

cultural history. The coastline became scattered with bourgeoisie’s

villas through the second half of the 19th century, and further

developed from 1900 to 1920, with a dense urban structure to a

distance of 20 km from Copenhagen, eliminating public access to

the coast (Vejre et al., 2007). The same period brought an

increasing pressure for recreational opportunities, not least

pertaining to the coast. The growing stock of industrial workers

in Copenhagen living under poor conditions revealed urgent needs

for access to open space. Hence, the1920s brought a clash between

private property rights and a rising democratic agenda of gaining

access to the coast for recreational and public health purposes.

Simultaneously, there was a rising concern as to the consumption

of what was considered high value landscapes in terms of

aesthetics and cultural history. This concern was probably most

pronounced at Springforbi, where there was a particular con-

sciousness of the loss of access to the coast (Struckmann, 1929).

The combined forces of the conservative interests in aesthetics and

cultural history, and the labour movements’ interests in recrea-

tional opportunities and public health spawned the 1930s

decisions of acquiring more than 50 villas at the most high-rated

(in terms of real estate) address of Denmark (Struckmann, 1942).

From 1940 all 50 villas, covering approximately 52 ha, were

gradually taken over by the State. The procedure was a simple

acquisition of the properties whenever they became available on

the market. After acquisition the single lots were opened to the

H. Vejre et al. / Ecological Complexity 7 (2010) 338–348

339

public and since the 1940s (the most recent being from 2006) villas

have been demolished too. In 1982, only about 30 villas were left,

and today less than ten are still standing (Fig. 2), some of which are

now preserved for architectural reasons. The area has gradually

been converted into a public park with access to the beach below

the cliffs. The outcome may be characterised as a rather unique

form of de-urbanisation, opening of the landscape, converting a

closed private suburb into a public open space park landscape.

The land cover of the 50 ha comprises grassland with scattered

trees, and shrub land at the low coastal cliffs. In terms of ecological

qualities the area rates quite low. The grassland is basically the old

garden lawns of the demolished villas. There are no qualities related

to old extensive grasslands or continuous forestcover, as can be seen

in the nearby Natura 2000 designated forest and grassland area.

2.2.2. Søllerød Municipality green space

The second case area comprises the open landscapes in Søllerød

Municipality (as of 2007 part of Rudersdal Municipality), north of

Copenhagen (Fig. 1). This municipality houses some of the most

attractive residential areas of Denmark, due to the high proportion

of protected forests, lakes and preserved open land, combined with

its proximity to the sea and downtown Copenhagen (15 km). Until

1900, the municipality was in essence a rural area with scattered

forest patches (the forests of this region were generally protected

in the 1780s), but the opening of the railroads in the last part of the

19th century brought a number of summer residences (Fig. 5).

From 1900 to 1930 there was an extensive sprawl of summer

houses, gradually developing into full-time residential areas. This

settling of Søllerød Municipality took place in the most attractive

parts of the landscape: at lakeshores, along forest edges, water-

courses and valley slopes (Vejre et al., 2007). The negative effects of

the consumption of high quality open land became evident in the

1920s. The sprawl threatened to exclude the general public from

access to recreational opportunities. In 1928, the first initiative was

taken to contain the urban sprawl, by the establishment of a

committee for the elaboration of a general urban plan for greater

Table 1

Summary of information regarding the two case areas.

Springforbi Søllerød Nature Park

Area 50 ha 280 ha

Land cover/land use 2009 Public park, lawns, scattered trees and villas Agricultural fields, pastures, forests, lakes, wetlands, golf course

Major ecosystem services Recreation, aesthetics Recreation, aesthetics, wildlife habitats, ground water

Public intervention method Acquisition and demolition Nature conservation orders

Ownership 2009 100% State owned 90% State or municipality; 10% private

Period of intervention 1940–1960 (acquisition) 1930–1960

1940–2006 (demolitions)

Landscape evaluation indicators Potential vista; connection between coast and Deergarden Wetlands, steep terrain, proximity to forests and lakes

Cost of provision >800 million DKK (>110 million

s

) 2125–4250 million DKK (280–570 million

s

)

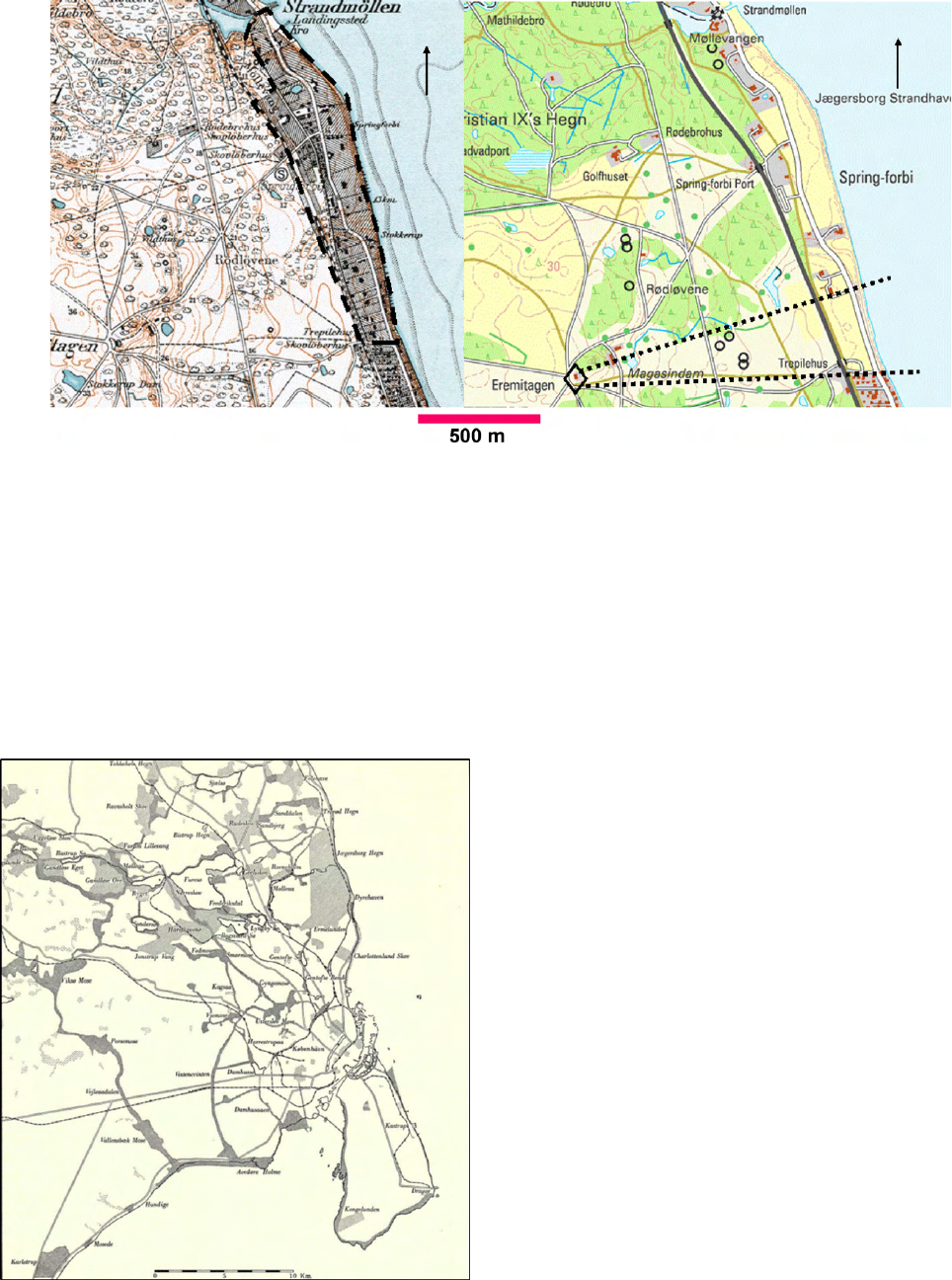

Fig. 1. Map of Denmark, and of Greater Copenhagen showing the location of the study areas: Søllerød (1) and Springforbi (2).

H. Vejre et al. / Ecological Complexity 7 (2010) 338–348

340

Copenhagen (Gaardmand, 1993). In 1936, the committee pub-

lished a plan for the establishment of a recreational network in the

landscapes north of Copenhagen (Forchammer, 1936), Fig. 3. The

plan suggested the protection of patches of open landscapes,

combined with a recreational infrastructure connecting the city

centre with the landscapes. The plan was approved in 1938, Fig. 4

(Blixencrone-Møller, 1939), and from 1938 to 1960 the plan was

almost realised by imposing nature protection orders in all the

designated areas, in the 1940s also supported by the local mayor in

Søllerød (Goldschmidt et al., 2006). Alongside this development

the remaining areas of Søllerød Municipality was more or less

urbanised, so today the entire municipality of approximately

35 km

2

is divided into three distinct classes: (i) protected forests,

(ii) open countryside under nature protection orders, and (iii)

urban areas. The open land consists of five larger patches (each

covering more than 1 km

2

) and several smaller patches. The larger

areas cover a total of 8.5 km

2

.

In this context we concentrate the case study to the so-called

Søllerød Nature Park area (Fig. 6). The Nature Park covers an area of

4km

2

. The land cover of the open space comprises agricultural

land (120 ha, all under organic management), various wetlands

(25 ha), forests (85 ha) and extensive grassland (150 ha), including

golf courses. The forests are primarily plantation forests with a

relatively low biological quality. Most of the grasslands are less

than 50 years old and do not contain large biological qualities. In a

few patches old permanent pastures with a high biodiversity are

found. The prime nature quality is linked to the numerous small

lakes and ponds.

2.3. Landscape and land evaluation methods

In this paper, we attempt to scrutinise the procedure originally

employed to delineate the protected areas of the Copenhagen

urban fringe. The procedures bear resemblance to both classic land

evaluation and more contemporary landscape evaluation.

Land evaluations are generally performed in order to rate

qualities of land areas. Evaluation procedures have been

developed and refined throughout the 20th century (e.g.

Zonneveld, 1995; Rossiter, 1996). These evaluations have largely

addressed production-oriented land use purposes, such as

suitability for crop production. Also evaluation for intrinsic

values has been developed (e.g. Hamin, 2002). In general, land

evaluation follows a rather strict procedure of defining the aim

(guiding principles), defining land qualities (which properties

determine the usefulness of the land to the specific aim?) and

finally the indicators (which easily field identifiable variables

represent the properties?).

Fig. 2. Map of the Springforbi area in 1930 (left) and in 2004 (right) On the 1930 map the project area is indicated by the hatched line. On the 2004 map the vista from the

‘‘Eremitage’’ castle is indicated. In 1930 the situation prior to the acquisition process is clear: some 50 mansions and other houses blocking the access between the forests and

pasture area ‘‘Dyrehaven’’ and the coast. In 2004 the effect of almost 70 years of demolition is visible, less than ten buildings are left, and only one between the road and the

coast. The entire area is a public park, some of the remaining buildings are now protected, but still a few are to be demolished.

Fig. 3. The original nature conservation for Greater Copenhagen plan of

Forchammer (1936) indicating the critical core areas with the highest aesthetic

qualities and strongest potentials for recreation. Light grey, existing forests, dark

grey, proposed conservation areas.

H. Vejre et al. / Ecological Complexity 7 (2010) 338–348

341

Land evaluation has been performed for two overall

purposes: finding the most appropriate site for a given activity ,

and finding the most appropriate activity for a given site.

Examples of classic land evaluation procedures encompass

resource mapping for agricultural development o r landscape

analysis prior to the location of infrastructure. More recently, we

have seen procedures of identifying the most appropriate

conservation areas, e.g. the Natura 2000 process of the EU

(Anon., 1992). In contrast, landscape evaluation is performed to

rate more intangible values of landscapes such as visual qualities

and place identity.

We employed a retrospective ‘‘evaluation of the evaluation’’

procedure, as we took point of departure in the areas delineated

decades ago and scrutinised the relevant documents in order to

identify the original articulated aims and guiding principles behind

the designations of conservation areas. Further, the identification

of properties and the indicators used by the land surveyors in the

delineation procedure were attempted. It should be stressed that

the evaluation procedure behind these designations somehow

follow the classic land evaluation procedures, inasmuch as the

designation procedure followed a well-defined aim, and rested on

field identifiable indicators, such as wetlands and steep terrain, as

representative of a more complicated state of land units fulfilling

the defined aim. It should be kept in mind that the evaluation was

performed in the 1930s by a skilled engineer and urban planner,

decades before landscape architects formulated formal visual

analysis procedures.

But the evaluation certainly bears similarities to modern

landscape evaluations such as Ian McHarg’s approach which

employ ecological knowledge in physical planning by overlay

methodology where information on soil, vegetation and hydrology

are combined and translated into social value (Natuhara, 2006), or

Dearden and Sadler’s (1989) evaluation techniques of social

dependent aesthetic values. It also bears resemblance with

Steinitz’ six-stage process for landscape planning, of which the

landscape evaluation step include aspects such as costs, beauty,

user satisfaction, public health, but also nutrient fluxes and habitat

quality (Steinitz, 1990, 1995).

2.4. Recreational use assessment

Outdoor recreation demand is basically linked to resources such

as land based and man-made services. From a social-psychological

point of view, outdoor recreation demand refers to a person’s

willingness to spend time and other resources on recreation. The

outcome of this behaviour is an experience that satisfies personal

needs. Demand for recreation opportunities is thus a demand for

instruments or courses of action to realise a psychological demand.

Another approach, traditionally relating to resource allocation, is

to consider demand for recreation activities on specific sites or

resources (Clawson and Knetsch, 1978). Outdoor recreation should

also be considered within the context of, e.g. social, health, sport,

culture, forest and nature policy, and is thereby linked to other

social and economic goods and services.

Over the past decades, numerous techniques and methods have

been used to monitor visit to natural areas (e.g. Gasvoda, 1999;

Hornback and Eagles, 1999; Watson et al., 2000; Cessford and

Muhar, 2003; Arnberger et al., 2005; Kajala et al., 2007; Sieva

¨

nen

et al., 2008). This variety of methods is partly a consequence of the

broad range of recreation activities and settings. Since recreation

involves both a psychological experience and participation in a

specific activity in a specific area, studying outdoor recreation

usually requires more than simply counting the number of visits.

Gathering information about preferences, the perceived outcomes

of visits, the prior expectations of visitors, and the journey to and

from the area must be included. The choice of method depends on

the aim of the study, the type of area, the extent of various

activities, the number and types of visitors. Additional considera-

tions comprise the geographical and natural characteristics of the

area, and the behaviour patterns of the visitors. Those uses can be

concentrated or widely distributed, different activities may involve

different movement patterns, and the number of entry points to

the area varies. Many on-site studies are based on data gathered

from samples of visitors. However, a statistical representative

sample may be difficult to achieve, since the size of the total

research population is rarely known exactly; in order to count or

interview all visitors, the entire boundary of the area must be

monitored, which is costly and often not feasible. However, given

knowledge of general patterns of visit, and the location of entry

points, it is usually possible to select a number of strategic data-

gathering locations which together provide an acceptable level of

representativity.

The analyses and results we present in this paper estimate the

extent of recreational use in two case areas, using a household

survey in Søllerød Municipality (Baroudy, 2007) and a national on-

site survey wherefrom visit to specific sites in Søllerød Munici-

pality as well as Springforbi is extracted (Jensen, 2003).

2.4.1. Household survey in Søllerød Municipality

A questionnaire was distributed in 2006 among residents living

within a distance of 500 m from the nature area Søllerød Nature

Park (Fig. 6). The respondents were chosen randomly among the

households. A total of 500 questionnaires were distributed, and

approximately 50% was returned. The respondents gave basic

information such as age and gender, and addressed questions

pertaining to their use of and activities in the nature area: purpose

and frequency of visits, the satisfaction with facilities, and the

attitude towards other visitors. Finally, the respondents were

asked to indicate their favourite route on a map of the area. About

200 respondents provided that information.

2.4.2. National on-site survey

From earlier surveys we have extracted and refined data on

number of visitors in selected forest and nature areas of Søllerød

Municipality (five areas) and the Springforbi area.

Fig. 4. The approved plan of 1938 for nature protection orders, indicating the final

delineation of the future protected landscapes north of Copenhagen. The plan did

not deal with the landscapes west and southwest of Copenhagen. Note that some

areas were significantly expanded in comparison to the proposal (Fig. 3).

H. Vejre et al. / Ecological Complexity 7 (2010) 338–348

342

The basic data collection in 1996–1997 consisted of instanta-

neous, manual counts of parked cars and the delivering of 85,673

questionnaires in 592 forest/nature areas, with an area totalling

approximately 201,000 ha (Jensen, 2003). The response rate for the

questionnaires was 46.7%. During the field work all the places

where visitors could park their car (at a given forest/nature area)

were surveyed in the course of 1 h (simply by counting the number

of parked cars and delivery of questionnaires under their wind-

screen).

The time for manual counting at specific registration periods

had been selected by stratified random sampling. The counting

was carried out at 20 randomly stratified moments of maximum

1 h. The stratification took the seasonally, weekly and daily

variation into account. The enumerations to annual figures based

on the sample were undertaken by sample estimation (weighting).

The advantages of this method include the benefit that it is

based on a relatively manageable field work effort; and that

information regarding the number of users is obtained simulta-

neously for a large number of forest/nature areas. Among its

weaknesses is that only the recreational use of the car-borne

visitors is included in the actual counting. However, based on

information from other national surveys ( Jensen and Koch, 1997)it

is possible to estimate the total number of all types of visitors—

independent of means of transport. This is possible based on

general knowledge of the relationship between travelling distance

and use of car as a means of transportation. In Koch (1980) detailed

descriptions of the different methodological aspects are presented.

2.5. Economic assessment

The theory and application of environmental valuation

methods is by now far developed (e.g. Freeman, 2003) and builds

on the assumption that choices made by individuals (actually

revealed or stated hypothetical choices) involving trade-offs

between non-marketed and marketed goods and services, reveal

to the analyst the (marginal welfare economic) preferences and the

value of the non-marketed assets.

Revealed preferences can be obtained from markets, where

people trade goods that have an environmental attribute aspect of

interest, e.g. hedonic pricing methods can assess the effect on

house prices of proximity to, e.g. peri-urban forest and the implied

environmental services (Tyrva

¨

inen and Miettinen, 2000; Cromp-

ton, 2001; Anthon et al., 2005). A strong limitation of the revealed

preferences is that they capture only the kind of values that can be

appropriated by acting in the related market studied. Stated

preference method is – in theory – capable of valuing the more

intangible values related to, e.g. cultural heritage and landscapes

(Hasler et al., 2008; Tuan and Navrud, 2008). Both of these

approaches can only capture use or non-use values, as perceived by

people. Some value components may not be evaluated at all

(Costanza, 2008) and the information provided by respondents in

stated preference valuation studies can have quite dramatic

influence on the values estimated, e.g. for biodiversity protection

(Jacobsen et al., 2008).

A severe practical drawback of both of these approaches is that

they are often too advanced and cumbersome for the typical urban

planning unit or consultancy firm to undertake appropriately, and

they are also difficult to communicate to decision-makers. Partly

for these reasons, a number of other approaches to assess the

economic value of environmental services prevail in the literature,

and in particular in practice. This includes some cost based

methods, e.g. direct abatement costs incurred for avoiding an

environmental damage, costs of replacement or restoration of

environmental damages, or loss of environmental benefits. Or the

cost of provision, which assesses the opportunity cost – in terms of

marketed values and goods forgone – of adjusting land uses and

production systems to provide increased ecosystem services

(Pearce, 1998; Freeman, 2003). As measures of value, these

approaches to ‘‘pricing’’ the environment are heavily flawed as

they do not address the welfare effect of the environmental goods

and services, but only the (budget) cost of providing these services

(Freeman, 2003). Thus, observed direct costs incurred by

individuals or societies may usually, at best, be an absolute lower

bound of the value of the environmental service provided.

The direct cost based approaches do, however, have the

advantage – from a practical point of view – of being fairly easy

to apply as data are often reasonably easy to find. Furthermore,

layman as well as decision-makers can often better relate to,

understand and accept these methods. In this study, we will show

two examples of how these direct cost of provision approaches can

be applied as part of a three-tier approach to assessing the values of

peri-urban open spaces and the ecosystem services they provide.

More explicitly, real estate agents in the two different case areas

were asked about property values for real estates in the following

specific settings:

-

Real estates prices at Strandvejen, neighbouring the Springforbi

area, for houses comparable to the demolished houses (case area

1, Fig. 2).

-

Real estate prices for vacant yet undeveloped building lots

approved for single-family houses in Søllerød Municipality (case

area 2, Fig. 5).

-

Price differences between real estates bordering open space in

Søllerød Municipality, and comparable real estates with no direct

access to the open space. Similarly, the price effect of having a sea

view in the Springforbi area was assessed.

Based on these data, we can provide some illustrative measures

of the values that society has sacrificed to maintain these open

spaces for the sake of recreation and aesthetics.

3. Assessment results

The two case areas were protected or developed for the sake of

provision of two primary services: aesthetics and recreation. We

first provide an analysis of the original land and landscape

evaluation of the two areas, which employs a qualitative analysis

to pinpoint the nature of the intangible services, and also

pinpointing the reasons behind the exact delineation chosen

during the planning process. Subsequently, the recreational use of

the areas is documented and discussed also in terms of quality of

the recreational experiences pursued by users. Finally, an

assessment of the costs of providing these benefits is made, which

can be considered a lower bound on the economic value of the

ecosystem services provided. For summaries of data consult

Tables 1 and 2.

3.1. Land and landscape evaluations

3.1.1. The delineation of the case areas

It is not within the scope of this paper to perform an updated

landscape analysis to identify the aesthetic qualities of the areas

per se. Rather, we analysed the original land and landscape

evaluation procedures on which the designations of the 1930s and

1940s rest. This is done by scrutinising the original planning

documents, from which the rationale behind the exact delineation

of the two case areas was extracted. The delineation of the

Springforbi case is found scattered in the archives of the Danish

Forest and Nature Agency and in various publications of the 1940s.

The delineation of the Søllerød case was published along with the

other area delineations of northern Copenhagen in 1936 (For-

chammer, 1936; Blixencrone-Møller, 1939). In both cases the exact

H. Vejre et al. / Ecological Complexity 7 (2010) 338–348

343

delineation represents decisions made by a very limited number of

experts.

3.1.1.1. Springforbi area. The Springforbi area was chosen as the

core area for the process of regaining the public access to the coast

for several reasons. The surroundings of the area were important—

it links the central, open plains of Jægersborg Dyrehave (a deer

park) with the sea at a point where cliffs make broad vistas

possible.

The aim of the Springforbi demolitions was to clear a strip for

thesakeofpublicaccesstothecoast,andforreclaimingthe

vistas from the iconic vantage point the Eremitage, a royal

hunting castle from 1736, placed in the centre of Dyrehaven.

Prior to the urbanisation of the coast, visitors could admire the

view over the plains, across the sea to the coast of Scania (South

Sweden).

Further, the area comprised some of the larger villas, which

were not yet parcelled out, making the process of public

acquisitions easier. Starting with the villa ‘‘Springforbi’’

(2.5 ha, later to lend name to the entire area, Fig. 2) in 1940,

the villas ‘‘Beaulieu’’ and ‘‘Konow’’ (each 1.5 ha) in 1941, a core

area was defined for the future e stablishment of a public park

(Struckmann, 1942). The three villas were demolished shortly

thereafter. In the following decades the State Forest Service

pursued a strategy of buying properties whenever possible to

expand the park area, and after a few years d ecision on the exact

delineation of the park area became relevant. To the north the

watercourse ‘‘Mølleaaen’’ constituted a natural borderline for the

park. In contrast, the southern demarcation line was a very

pragmatic choice. The boundary for the park area was decided so

thevillastoevadedemolitionarenotvisiblefromtheEremitage

i.e. an aesthetically motivated demarcation (Fig. 2). Further, the

delineation corresponded with one of the major access routes to

the forest.

3.1.1.2. Søllerød Municipality green space. The land evaluation, on

which the delineation of the conservation areas rests, was literally

done entirely by Olaf Forchammer, the Chief Engineer of

Copenhagen City, working for the committee for the elaboration

of a comprehensive urban plan for Copenhagen. Surveying

intensively in the areas north of Copenhagen in the early 1930s

he drafted the plan in a comprehensive report (Forchammer, 1936)

(Fig. 3) which in a revised form of 1938 was realised almost

completely (Fig. 4 ). The premises for designating the future green

space are carefully described in the report. The guiding principle

for Forchammer’s survey was recreation, both as a physical

exercise requiring space and land, and as a mental experience,

requiring attractive landscape, peace and views. Nature conserva-

tion in terms of habitat and species protection was a subdued issue

at that time and only mentioned briefly. Concerns regarding the

urban development were raised as many new settlements were

not equipped with sewers, leaving lakes and wetlands vulnerable

to pollution. As landscape qualities, Forchammer surveyed the

landscape for larger open land, for beautiful vistas, for peaceful

environments, and for areas located in close connection to

protected forests and lakes. The most prominent indicators were

steep terrain, proximity to lakes and forests, wetlands and

watercourses. Properties determining recreational qualities com-

prised the presence of lakes and coasts with potentials for bathing,

and areas suitable for camping grounds close to water and forests

and curiously, far from ‘‘tempting’’ facilities such as inns and

restaurants.

After defining what were to be the core areas of the future

conservation areas, Forchammer sketched future recreational

traffic routes and parkways, connecting the city centre with the

conservation areas, and interconnecting them. In essence, the

plan of 1936 dealt with the identification of the cr itical core areas.

In the plan maps, the areas are hatched (Fig. 3),andtheyarenot

exactly delineated. In the further process, a committee under the

Prime Minister decided the exact boundaries, basically by

following clear features in the landscapes, such as roads and

hedgerows, or cadastral boundaries (Fig. 4). The core areas are

hence the parts of the landscape that Forchammer in the early

1930s found the most attractive, the boundaries determined by

pragmatic decisions.

Fig. 5. Maps of the three stages progressive development of the southern part of

Søllerød Nature Park. (a) Map from 1890 shows the rural area of Søllerød

Municipality, (b) map from 1940 shows the beginning urban sprawl, and the (c)

contemporary map shows the three categories of the landscape today: urban areas,

protected forests and open landscapes under nature protection orders.

H. Vejre et al. / Ecological Complexity 7 (2010) 338–348

344

3.2. Recreational uses

The intensity of recreational uses is shown in Table 2. Data for

Søllerød Municipality consists of five nature areas, which in total

receive 421,000 visits a year—equivalent to 720 visits/year/ha or

890 visitor h/year/ha. This level of visit is considered an intensive

use (defined as 300–999 visitor h/year/ha) in a Danish context. The

area ‘‘Søllerød Kirkeskov and Rygaard’’ in Table 2 is almost

equivalent to Søllerød Nature Park (case area 2) with 136,000 visits

a year—equivalent to 655 visits/year/ha or 866 visitor h/year/ha.

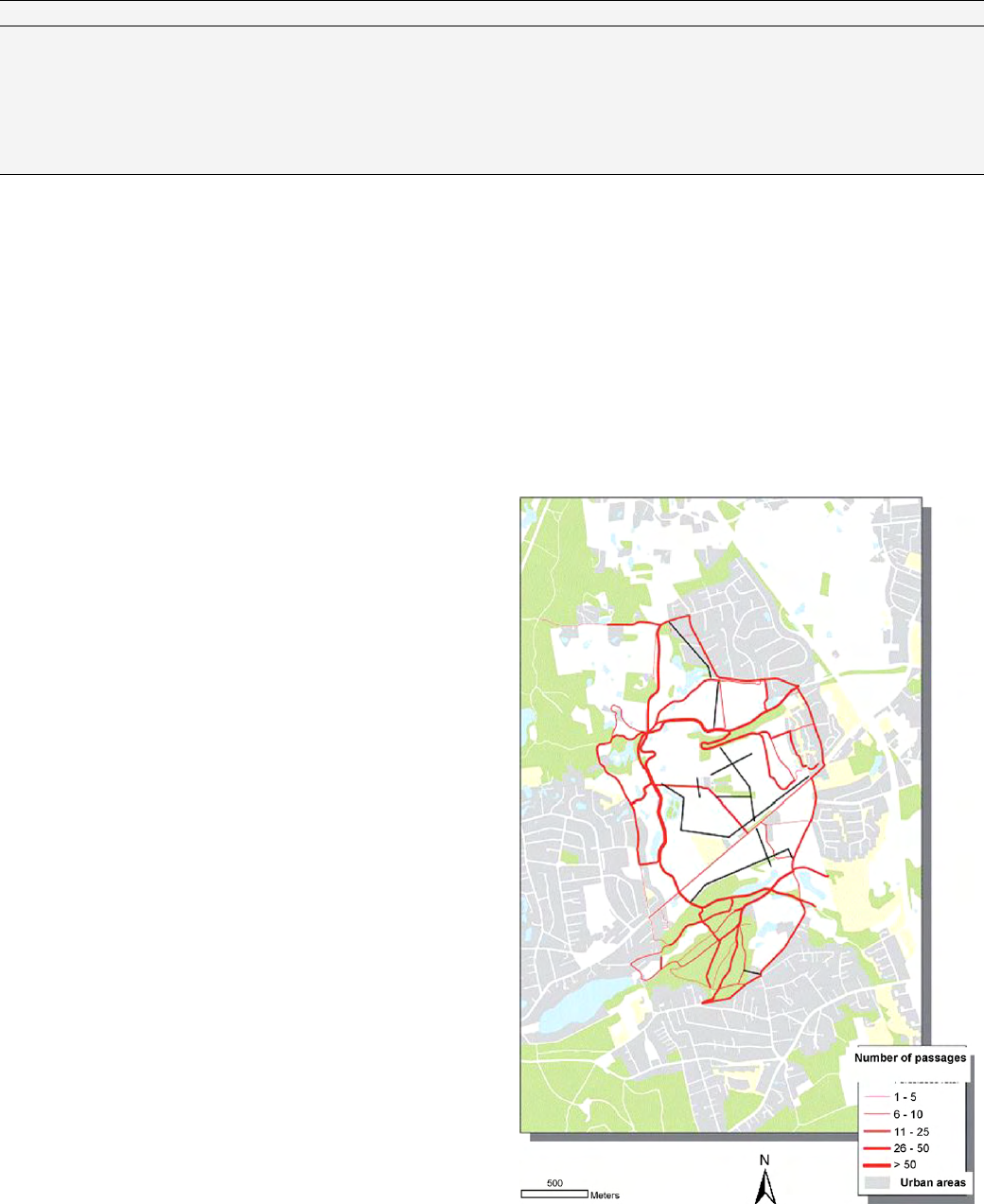

The household survey in Søllerød Municipality gave some

additional information on the recreational use of the Søllerød

Nature Park—indicating that approximately half of the respon-

dents visit their local nature area at least once a week. The typical

activity is a foot trip/stroll, walking the dog, jogging or cycling.

About one third of the visitors appreciate wildlife (watching birds)

during the visit. About 90% of the visitors are very satisfied with the

facilities and opportunities within the area. Certain conflicts

among users are mentioned, in particular animosity towards

mountain bikers and dogs without a leash. The respondents’ map

with favourite routes gives a detailed impression of the use of the

recreational infrastructure, and the variation in intensity of

recreational traffic (Fig. 6).

The visit of the Springforbi case is based on the total use of

Jægersborg Dyrehave and Hegn, which is very intensively used

with more than 7 million visits a year—equivalent to 4460 visits/

year/ha or 9074 visitor h/year/ha. Specific geographical delimita-

tion of the recreational use of the Springforbi part of the total area

is relatively complicated, as recreationists obviously are not static

in their use of the area. It is possible to make a rough estimation

based on the specific use of the five entrance points, which are

directly linked to the Springforbi area. For these entry points alone,

the yearly number of visits can be estimated at approximately 1.1

million. This is a conservative estimate, as numerous visitors from

other entry points to Jægersborg Dyrehave will visit the Springforbi

area, especially due to the vista from the Eremitage castle (Fig. 2). A

more realistic proxy will probably be the double—around 2–2.5

million visits a year. As for Søllerød, most visitors to Springforbi are

satisfied with the facilities, and conflicts with mountain bikers and

dogs without leash are mentioned by some visitors.

Whether the 1996/1997 recreation data are valid for 2008 is of

course questionable. But as this paper is testing how far we can get

in valuating ecosystem services by relatively simple quantifica-

tions, we suppose the accuracy to be adequate in this context. For

testing of benefits transfer of forest recreation over time, see e.g.

Zandersen et al. (2007a,b).

3.3. Assessing cost of provision in the case studies

Based on the simple methods described above, we can provide

some illustrative measures of the values that society have

sacrificed to maintain these open spaces for the sake of recreation

and aesthetics.

3.3.1. The Springforbi area

Real estate prices along the coast road north of Copenhagen,

Figs. 1 and 2, are among the highest in Denmark. This is due to the

attractiveness of the area in general, being close to the city centre,

close to the sea (the Øresund) and also quite close to Jægersborg

Dyrehave and Jægersborg State Forest District (Fig. 2). In addition,

houses in this area are quite large, by Danish standards, often

situated on fairly small land lots. Prices for typical units consisting

of a house with 200–500 m

2

of living space, on a land lot of some

500–800 m

2

, lie within 10–30 million DKK as of November 2008,

corresponding to 1.3–4 million

s

. Incidentally the estate exactly

neighbouring the Springforbi case area was for sale at 32 million

Table 2

Intensity of recreational use of the case study areas 1996/1997 (Jensen, 2003).

Area Annual visits (1000) Annual visits per ha Annual visitor hours (1000) Annual visitor hours per ha

The Søllerød Municipality case

Trørød Hegn 56 997 56 1008

Kohaven 2 60 4 104

Søllerød Kirkeskov and Rygaard

a

136 655 179 866

Geel Skov 202 1045 247 1279

Ravneholmene 25 260 35 367

The Springforbi case

Jægersborg Dyrehave and Hegn 7501 4460 15,263 9074

a

Almost equivalent to Søllerød Nature Park.

Fig. 6. The recreational intensity as expressed by number of passages in Søllerød

Nature Park. Data represents approximately 200 inputs from local residents within

a distance of 500 m from the area (Baroudy, 2007).

H. Vejre et al. / Ecological Complexity 7 (2010) 338–348

345

DKK ( >4 million

s

) at the time of gathering data for this analysis.

The huge variation in prices arises not only because of the variation

in the size of land lots and notably house sizes, but also because of

an important variation in the environmental attributes of different

sites. Estate dealers all stressed that in this area there is a

significant difference between houses on the seawards side of the

North-South travelling coastal road and those on the landwards

side (Fig. 2). They assessed that properties with a clear view

towards the sea had on average a price premium of about 20–30%.

This is well in accordance with several hedonic pricing studies on

similar environmental attributes from other places in Denmark,

reporting effects of lake view or neighbouring a forest of up to 20%

in more wealthy and larger urban areas, and some 10% in the

countryside, where supply of such environmental attributes is

higher and average income is lower (Anthon et al., 2005; Birr-

Pedersen, 2006).

In 1940, about 50 villas of varying sizes but typical for the

general area occupied the strip of land between the inland open

area and the seaside. All villas were taken over by the state, and

about 40 were demolished, several of them facing the sea directly.

The number of villas demolished was probably too small to affect

the general housing market in the area. Even for the nearby houses,

the increase in environmental value is likely to be negligible as

nearness to coast and inland forest lands was already present.

Based on the above evidence, we assess that the market value of

these estates would – in today’s currency – have been in the range

of 400–1200 million DKK or 50–160 million

s

. Compared with the

surrounding area, relatively many of these houses were facing the

sea, implying that the actual costs are likely to be at the upper end

of this interval, most likely above 800 million DKK.

This is the present value of the sacrifice that society in the 1940s

decided to make in return for the (in principle) eternal ecosystem

service provided by the landscape connecting the seaside to the

inland open grassland and forest areas, and the views and access to

the sea. Of course, society may in principle expand housing in

another part of the urban region, to maintain the supply of houses.

This may potentially cause a reduction in eco-system services

elsewhere, which cannot be assessed here. It seems safe to assume,

however, that their value will not rival those estimated here.

3.3.2. The Søllerød Municipality green space

While heavily urbanised, Søllerød Municipality is characterised

by large tracts of land left undeveloped to preserve the natural

beauty of the landscape and the landscape amenities that are

important parts of the attractiveness of the area in terms of

demand for single-family houses. These areas are all protected

against urbanisation and subjected to very strict regulation. When

these restrictions were decided, the implication for society was to

forgo opportunities for further urbanisation and development of

residential areas. A master plan of 1943 for the development of the

municipality (i.e., before the conservation planning process was

entirely unfolded and generally accepted by the local munici-

palities) literally suggested the development of the entire area into

various urban categories (Goldschmidt et al., 2006). Hence, it is

relevant to express the value of the open space at least partly as

missed development opportunities. The area, however, is so large

that a full development would have direct supply effects on the

house market in the region, causing lower prices. It is large enough

for some 10–15,000 land lots for single-family houses to be

established in the better parts of these tracts. Apart from the

negative effect on the house market in the area, the effect of a large

scale development would also be to erode a significant part of the

value of the existing environmental attributes embedded in the

value of existing houses.

Estate agents again assess that houses with direct access and

connection to the forests and open lands in the area, have a selling

price some 25% higher than houses just a few hundred meters

away. This is in accordance with hedonic models of similar cases

(Anthon et al., 2005; Birr-Pedersen, 2006). Several hundred houses

in the area benefit from this direct access, and with a typical single-

family house in the area having a selling price of 5–10 million DKK

(0.7–1.4 million

s

), the aggregate environmental value component

of the existing property values is likely to amount to several 100

million DKK. Thus, if we want to consider the opportunity cost of

forgone residential development, we would in fact need a model of

the house market in the area capable of assessing non-marginal

effects of changes in the supply of housing as well as the supply of

environmental services.

That the potential value of the environmental services is,

nevertheless, massive can be illustrated by making a more cautious

partial calculation: If, for instance, only some 10% of the open space

of Søllerød Municipality was parcelled out as typical single-family

house lots, which in Denmark typically cover 800–1000 m

2

,still

more than 1000 lots could be sold. As vacant lots in the area are sold

for typically 2500–5000 DKK (350–700

s

)perm

2

, these lots would

represent a gross value of 2125–4250 million DKK (280–570 million

s

). Increasing the built-up area may of course reducethe value of the

environmental services experienced by those already living in the

area, but nothing near the gain measured here. Thus, in spite of the

value of the current ecosystem services likely to be embedded in the

current property stock, society is willingly carrying a cost much

larger than this to preserve the general ecosystem services arising

from these urban open areas and forest patches.

4. Discussion and concluding remarks

The combination of three distinct methods: the land evaluation

and identification of qualities, assessment of recreational use, and

monetary assessment, gave a unique opportunity of valuing

intangible services within the same limited tracts of land. We

should, however, discuss the degree of representativity before

aiming at any general conclusion.

The case in Søllerød Municipality – Søllerød Nature Park – is

representative of green space in the northern suburbs of Copenha-

gen in terms of landscape, ownership, location and land cover (even

though it is larger than the average green area in Søllerød

Municipality). But the area rates as some of the most attractive

and pricey in terms of real estate, and cannot without reservation be

compared with green areas west and southwest of Copenhagen. The

Springforbi area is quite unique, the location, neighbourhood and

price level is not to be found anywhere else in Denmark.

The delineation of the case areas followed different pathways.

In Søllerød, the delineation was based on a decision on the location

of critical core areas, followed by a pragmatic decision on the exact

boundaries. In Springforbi, the opposite and very costly procedure

was followed. The extent of the Springforbi area was not based on

existing values, but on potential values, and consequently the

decisions were where to create the ecosystem services. The study

revealed that the underlying evaluation of the landscape qualities

is heterogeneous in nature, elitist in the sense that the task was

done by a few individuals, and subjective. The evaluation and

decisions were made before participatory planning was an issue,

and the planning process must be characterised as functionalistic

and centralised.

It should further be noted that the planning documents were

not straight-forward. They were very detailed in Søllerød

Municipality, but scattered and not published in Springforbi.

Interestingly, the results that the ‘‘old experts’’ came up with

three generations ago, reflect more or less what more recent forest

and landscape preference studies of the general Danish population

have revealed (Koch and Jensen, 1988; Jensen, 1999). At a time

where participatory planning is enthroned, a more philosophic

H. Vejre et al. / Ecological Complexity 7 (2010) 338–348

346

discussion of nature quality and democracy could be enlightening

and rewarding, as the case of e.g. Arler (2002), who discusses the

pros et cons of the use of ‘‘the experienced connoisseur’’ and ‘‘the

biological connoisseur’’ in the process of identification of nature

quality.

We estimated aesthetics, open space amenity and recreation

pressure, but in a comprehensive study of ecosystem services we

should also have valued other services, e.g. habitat value,

groundwater extraction, CO

2

sequestration etc. We did not

compile these d ata in any quantitative manner, but some remarks

should be made on the other ecosystem services. The Sprin gforbi

area’s limited extent of 50 ha proves insignificant for services s uch

as filter and CO

2

sequestration, though its capacity per ha may be

as high as many other green space areas. There is no significant

water e xtraction, and the area is not known to house any species of

special importance, in particular when compared to reference

areas of biodiversity hotspots in other locations of greater

Copenhagen. Being a part of the larger forest area it certainly

provides some habitat services. Truly it is an area serving mainly

intangible services or functions. The broad range of services

discussed here differs strongly in their ‘‘spatial extent’’. As an

extreme, the carbon sequestration is strictly limited to the area

itself, whereas the transboundary effect is larger for the habitat

service, as organisms may cross boundaries. As another extreme,

the aesthetic and transcending, cultural services certainly

‘‘radiate’’ out of the area, not just because the area has impact

on vistas from a much larger areas, but also because the service

penetrate into the minds of an entire population, as the site is a n

iconic landmark playing a role for people not even visiting the

area.

In contrast the nature areas of Søllerød have important habitats,

in particular such pertaining to wetlands and forests. Also, the areas

are large enough to play a role as climate mediators, as CO

2

-

sequestration areas and as water reservoirs. However, these services

are not unique for this area, and better substitutes are found in the

region.Hence, it is beyonddoubt thattherecreationalandlandscape/

aesthetic values are the prime ecosystem services provided from

these areas. The case neatly demonstrates the power of spatial

planning in reducing the costs of acquiring urban green space, with

‘‘eternal’’ provision of recreational and aesthetic services.

The Springforbi case is a very illustrative example of the level of

costs that the society is facing, when no or just inadequate planning

is unfolded. The coast north of Copenhagen was developed before

any regulation on urban sprawl was formulated. The first urban

planning regulation was enforced in the 1920s, and prior to that the

authorities had almost no power or legal instruments to preserve

areas for recreational purposes. With contemporary legislation it

would have been rather simple to delineate a recreational zone

without compensation to owners, and in general all Danish coasts

are protected by strict regulation on development 3 km inland from

the coastline. In 2009 values, an estimated average of about 115

million

s

would be the cost of compensating for the lack of spatial

planning instruments in a small area of 50 ha.

In comparison to the Springforbi area, the process of spatial

planning, and the implementation of the plan by employment of

nature protection orders and payment of compensation to the

landowners, proved to work in Søllerød.

The tools becoming available in Denmark in the late 1930s were

conservation planning, meaning that local and regional authorities

could designate areas of importance for recreation and nature

conservation. The mere designation had legal deferment effect on

any development, until a central committee had approved the

plan. The declaration of nature conservation order was not free of

charge, as private landowners could claim a compensation for lost

development opportunities. In some cases the authorities had to

pay compensation, in other cases the landowners voluntarily let

their properties be subjected to nature conservation orders.

However, this planning hindered other development opportu-

nities. In 2009 values, the sacrifice made for preserving these 8 km

2

in Søllerød is in the range of 280–570 million

s

.

From an economic point of view, the role of the more or less

centralised spatial planning process, from goal formulation to

implementation, is to correct the following important market

failure: Without regulation and spatial planning, beautiful peri-

urban landscapes will – roughly speaking – be developed until the

point where they are no longer beautiful and at least as crowded as

any other potential piece of land available for development, ceteris

paribus. The spatial planning process and laws regulating it are

capable of protecting such local public goods from a super-optimal

degree of development.

In any case study the question should be raised whether the

analysis is universal or confined to a specific geographic area. The

results are probably somewhat confined—the vicinity to an urban

conglomerate plays a role.

In other cases, demolition of houses on critical sites in Denmark

has taken place. The UNESCO World Heritage Site Jelling, which is

an ancient Viking monument from the 10th century, was cleared of

a number of residential houses surrounding it (Adriansen, 2003).

An old industrial complex was cleared near Hamlet’s castle

Kronborg in connection with its admission onto the UNESCO list.

Globally, several examples of demolitions near ancient monu-

ments and near unique nature sites could be mentioned. One is

Uluru/Ayers Rock in Australia, where tourist facilities next to the

rock were demolished in the 1970s. But we have so far not found

other records of the demolition of estates located on a city’s most

fashionable address – for the sake of a view – anywhere in the

world.

On the other hand, the case of safeguarding green areas at the

city perimeter is probably valid for urban conglomerates of most

developed countries, and certainly of use for developing countries

with sprawling cities. In order to safeguard and develop recrea-

tional and aesthetic land values in a future dominated by climate

change and biodiversity agendas, development of sound planning,

evaluation and mapping methods which identify and delineate

these values are important (e.g. Caspersen and Olafsson, 2009).

5. Conclusions

Among ecosystem services, the category of intangible, trans-

cending and social functions must be rated alongside tangible

services linked to physical processes such as habitats, water, air,

buffering etc. if a balanced sustainable development is to be

reached.

The cases and the case histories we have described in this paper

demonstrate several things:

-

that the intangible services may certainly rival the tangible ones

in some areas around larger cities

-

that there are several ways in which these values can easily be

quantified in a way suitable for communication

-

that some degree of centralised spatial planning processes can –

even if not as participatory and transparent as those of today –

protect the common interests and the public goods in peri-urban

areas and counteract the market failure implied by these large

externalities.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Chief Forester Klaus Waage Sørensen

at the Danish Forest and Nature Agency, Copenhagen for valuable

contributions to the description of the Springforbi Case.

H. Vejre et al. / Ecological Complexity 7 (2010) 338–348

347

References

Adriansen, I., 2003. Nationale symboler i det danske rige 1830–2000. Museum

Tusculanum, ISBN: 87-7289-794-5 (in Danish).

Anon., 1992. Council Directive 92/43/EEC of 21 May 1992 on the conservation of

natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora. Council of Europe. Online at: http://

eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:31992L0043:EN:NOT.

Anon., 2001. Multifunctionality. Towards an Analytical Framework. OECD Publica-

tions, 2. Rue A

`

ndre

´

-Pascal, 75775 Paris Cedex 16, France.

Anthon, S., Thorsen, B.J., Helles, F., 2005. Urban-fringe afforestation projects and

taxable hedonic values. Urban For. Urban Green. 3, 79–91.

Arler, F.;1;, 2002. Naturkvalitet og demokrati. In: Arler, F. (Ed.), Humanøkologi,

Miljø, teknologi og samfund, Aal borg Universitetsforlag, pp. 389–408 (in

Danish).

Arnberger, A., Haider, W., Brandenburg, C., 2005. Evaluating visitor monitoring

techniques: a comparison of counting and video observation data. Environ.

Manage. 36, 317–327.

Baroudy, A.T., 2007. Friluftsliv, Forvaltning og Fremtid i Søllerød Naturpark og

Vaserne. Masters Thesis. University of Copenhagen (in Danish, English

abstract).

Birr-Pedersen, K., 2006. Measurement and Benefit Transfer of Amenity Values from

Afforestation Projects: A Spatial Economic Valuation Approach Using GIS

Technology. PhD-dissertation. University of Copenhagen.

Blixencrone-Møller, C., 1939. Københavnsegnens Fredningsplan. In: Struckmann, E.

(Ed.), Dansk Naturfredning. Danmarks Naturfredningsforenings Aarsskrift

1938-39, Gyldendalske Boghandel, Nordisk Forlag, København (in Danish).

Brandt, J., Vejre, H. (Eds.), 2003. Multifunctional Landscapes, vols. I and II. WIT Press,

Southampton, ISBN: 1-85312-934-8, ISSN: 1369-8273.

Brandt, J., Vejre, H., 2003b. Multifunctional landscapes—motives, concepts and

perceptions. In: Brandt, J., Vejre, H. (Eds.), Multifunctional Landscapes, vols.

I and II. WIT Press, Southampton, ISBN: 1-85312-934-8, ISSN: 1369-8273.

Caspersen, O.H., Olafsson, A.S., 2009. Recreational mapping and planning for

enlargement of the green structure in greater Copenhagen. Urban For. Urban

Green., doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2009.06.007.

Cessford, G., Muhar, A., 2003. An overview of monitoring options for visitor numbers

in national parks and other protected natural and recreation areas. J. Nat.

Conserv. 11, 240–250.

Clawson, M., Knetsch, J.L., 1978. Economics of Outdoor Recreation. Resources for the

Future, Inc. by The John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore and London.

Costanza, R., d’Arge, R., de Groot, R., Farber, S., Grasso, M., Hannon, B., Limburg, K.,

Naeem, S., O’Neill, R.V., Paruelo, J., Raskin, R.G., Sutton, P., van den Belt, M., 1997.

The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature 387,

253–387.

Costanza, R., 2008. Ecosystem services: multiple classification systems are needed.

Biol. Conserv. 141, 350–352.

Crompton, J.L., 2001. The impact of parks on property values: a review of the

empirical evidence. J. Leisure Res. 33, 1–31.

Dearden, P., Sadler, B., 1989. Landscape evaluation: approaches and applications.

Westernal Geographical Series, vol. 25. University of Victoria.

de Groot, R.S., Wilson, M.A., Boumnas, R.M.J., 2002. A typology for the classification,

description and valuation of ecosystem functions, goods and services. Ecol.

Econ. 41, 393–408.

Farber, S.C., Costanza, R., Wilson, M.A., 2002. Economic and ecological concepts for

valuing ecosystem services. Ecol. Econ. 41, 375–392.

Forchammer, O., 1936. Københavnsegnens Grønne Omraader. Forslag til et System

af Omraader for Friluftsliv, Dansk Byplanlaboratorium, Gyldendalske Boghan-

del, Nordisk Forlag, København (in Danish).

Freeman III, A.M., 2003. The Measurement of Environmental and Resource Values,

Theory and Methods, second ed. Resources for the Future, Washington, DC.

Gaardmand, A., 1993. Dansk Byplanlægning 1938-1992, Arkitektens Forlag, ISBN

87-7407-132-7 (in Danish).

Gasvoda, D., 1999. Trail traffic counters: Update, Report 9923-2835-MTDC, USDA

Forest Service. Missoula Technology and Development Centre, Missoula, MN.

Goldschmidt, E., Johansen, J., Monies, F., Stilling, N.P., 2006. Vejen til Rudersdal,

Søllerød Municipality, ISBN 87-88792-55-2 (in Danish).

Hamin, E.M., 2002. Western European approaches to landscape protection: a review

of the literature. J. Planning Lit. 16, 339–358.

Hasler, B., Jacobsen, J.B., Lundhede, T.H., Martinsen, L., Thorsen, B.J., 2008. Værdisæt-

ning af natur og kulturgoder. Et metodestudie af betydningen af ændringer i skala

og betalingsformat [Valuation of environmental and cultural goods. A metho-

dological study on the role of embedding scale and payment format]. Report no.

695, National Environmental Research Institute, Rosklide, Denmark, 81 pp.

Hornback, K.E., Eagles, P.F.J., 1999. Guidelines for Public Use Measurement and

Reporting at Parks and Protected Areas. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cam-

bridge, UK.

Jacobsen, J.B., Boiesen, J.H., Thorsen, B.J., Strange, N., 2008. What’s in a name? The

use of quantitative measures vs. ‘Iconised’ species when valuing biodiversity.

Environ. Resource Econ. 39, 249–263.

Jensen, F.S., 1999. Forest Recreation in Denmark from the 1970s to the 1990s. The

Research Series No. 26-1999, Forskningscentret for Skov & Landskab, Hørsholm,

Denmark.

Jensen, F.S., 2003. Friluftsliv i 592 skove og andre naturomra

˚

der, Skovbrugsserien

nr. 32-2003, Skov & Landskab, Hørsholm, Denmark (in Danish).

Jensen, F.S., Koch, N.E., 1997. Friluftsliv i skovene 1976/77-1993/94. The Research

Series No. 20-1997, Forskningscentret for Skov & Landskab, Hørsholm, Denmark

(in Danish).

Kahnemann, D., Knetsch, J.L., 1992. Valuing public goods: the purchase of moral

satisfaction. J. Environ. Econ. Manage. 22, 57–70.

Kajala, L., Almik, A., Dahl, R., Diksaite, L., Erkkonen, J., Fredman, P., Jensen, F.S.,

Karoles, K. Sieva

¨

nen, T., Skov-Petersen, H., Vistad, O.I., Wallsten, P., 2007. Visitor

monitoring in nature areas—a manual based on experiences from the Nordic

and Baltic countries. TemaNord 2007:534, Naturva

˚

rdsverket, Bromma, Sweden.

Koch, N.E., 1980. Skovenes friluftsfunktion i Danmark. II. del. Anvendelsen af

skovene, regionalt betragtet. (Forest recreation in Denmark. Part II: the use

of the forests considered regionally). Forstl. Forsøgsv. Danm. 37, 73–383 (in

Danish, English summary).

Koch, N.E., Jensen, F.S., 1988. Skovenes friluftsfunktion i Danmark. IV. del. Befol-

kningens ønsker til skovenes og det a

˚

bne lands udformning. (Forest recreation

in Denmark. Part IV: the preferences of the population). Forstl. Forsøgsv. Danm.

41, 243–516 (in Danish, English summary).

Natuhara, Y., 2006. Landscape evaluation for ecosystem planning. Landscape Ecol.

Eng. 2, 3–11.

Pearce, David, 1998. Cost-benefit analysis and environmental policy. Oxford Rev.

Econ. Pol. 14, 84–100.

Price, C., 2008. Landscape economics at dawn: an eye-witness account. Landsc. Res.

33, 263–280.

Rossiter, D.G., 1996. A theoretical framework for land evaluation. Geoderma 72,

165–190.

Sieva

¨

nen, T., Arnberger, A., Dehez, J., Grant, N., Jensen, F.S., Skov-Petersen, H. (Eds.),

2008. Forest Recreation Monitoring—a European Perspective. Working Papers

of the Finnish Forest Research Institute 79, Helsinki, Finland.

Steinitz, C., 1990. A framework for theory applicable to the education of landscape

architects (and other design professionals). Landsc. J. 136–143.

Steinitz, C., 1995. A framework for planning practice and education. In: Bunji, M.

(Ed.), Ecological Landscape Planning. Process Architecture, Tokyo, pp. 42–54.

Struckmann, E., 1929. Dansk Naturfredning. Danmarks Naturfredningsforenings

Aarsskrift 1928-29, Gyldendalske Boghandel, Nordisk Forlag, København 1939

(in Danish).

Struckmann, E., 1942. Dansk Naturfredning. Danmarks Naturfredningsforenings

Aarsskrift 1941-42. Gyldendalske Boghandel, Nordisk Forlag. København (in

Danish).

Tyrva

¨

inen, L., Miettinen, A., 2000. Property prices and urban forest amenities. J.

Environ. Econ. Manage. 39, 203–223.

Tuan, T.H., Navrud, S., 2008. Capturing the benefits of preserving cultural heritage. J.

Cult. Heritage 9, 326–337.

Turner, R.K., Paavola, J., Farber, S., Cooper, P., Jessamy, V., Rosendo, S., Georgiou, S.,

2003. Valuing nature: lessons learnt and future research directions. Ecol. Econ.

46, 493–510.

Vejre, H., Primdahl, J., Brandt, J., 2007. The Copenhagen finger plan. In: Pedroli, B., van

Doorn, A., de Blust, G., Paracchini, M.L., Wascher, D., Bunce, F. (Eds.), Europe’s

Living Landscapes. Landscape Europe, Wageningen/KNNV Publishing, Zeist,

ISBN: 978 90 5011 258 1.

Watson, A.E., Cole, D.N., Turner, D.L., Reynolds, P.S., 2000. Wilderness Recreation

Use Estimation: A Handbook of Methods and Systems. General Technical Report

RMRS-GTR-56. USDA Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station.

Yin, R.K., 2003. Case study research design and methods. Applied Social Research

Methods Series, vol. 5. SAGE, ISBN 0761925538, 9780761925538.

Zandersen, M., Termansen, M., Jensen, F.S., 2007a. Testing benefits transfer of

forest recreation values over a twenty-year time horizon. Land Econ. 83, 412–

440.

Zandersen, M., Termansen, M., Jensen, F.S., 2007b. Evaluating approaches to predict

recreation values of new forest sites. J. Forest Econ. 13, 103–128.

Zonneveld, I.S., 1995. Land Ecology. SPB Academic Publishing, Amsterdam, ISBN 90-

5103r-r101-7.

H. Vejre et al. / Ecological Complexity 7 (2010) 338–348

348